Abstract

Objectives. To examine the relationship of parental sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) attitudes with SSB consumption during the first 1000 days of life—gestation to age 2 years.

Methods. We studied 394 Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC)–enrolled families during the first 1000 days of life in northern Manhattan, New York, in 2017. In regression models, we assessed cross-sectional relationships of parental SSB attitude scores with habitual daily parent SSB calories and infant SSB consumption, adjusting for demographic and socioeconomic characteristics.

Results. Each point higher parental SSB attitude score was associated with lower parental SSB consumption (–14.5 median kcals; 95% confidence interval [CI] = −22.6, −6.4). For infants, higher parental SSB attitude score was linked with lower odds of infant SSB consumption (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 0.84; 95% CI = 0.71, 0.99), and adjustment for socioeconomic factors slightly attenuated results (AOR = 0.85; 95% CI = 0.71, 1.02).

Conclusions. During the first 1000 days of life, greater negativity in parental attitudes toward SSB consumption was associated with fewer parental calories consumed from SSBs and lower likelihood of infant SSB consumption.

Public Health Implications. Parental attitudes toward SSBs should be targeted in future childhood obesity interventions during pregnancy and infancy.

Emerging worldwide data show accelerated increases in childhood obesity prevalence in many countries, and childhood obesity prevalence rose globally over the past 4 decades.1 The United States has the highest childhood obesity prevalence of any country in the world, with 18.5% of US youths aged 2 to 19 years affected. Hispanic youths are most burdened, with a prevalence of 25.8%.2,3 Children in low-income households and racial/ethnic minorities are disproportionately affected by obesity, and etiologies of obesity and its disparities start early in life. Among those aged 2 to 5 years, Hispanic children have the highest obesity prevalence (15.6%), and non-Hispanic Black children have a 2-fold higher obesity prevalence (10.4%) than do their non-Hispanic White (5.2%) counterparts.2,4 To prevent childhood obesity and halt widening disparities, early life interventions to prevent childhood obesity among disproportionately burdened populations are needed.

The first 1000 days of life is the period from gestation through age 2 years and was recently recognized as a critical period for development of childhood obesity and its adverse consequences.5 Approximately 7.7% of US infants younger than 2 years have high weight for length (World Health Organization sex-specific z-score > 2.0 for age), predisposing them to obesity.6 Sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption is a major risk factor for development of obesity in adults,7 and emerging evidence links maternal SSB consumption during pregnancy with offspring obesity during middle childhood.8 Among infants, approximately 14% to 26% consume SSBs during the first year of life,9,10 leading to a 2-fold higher odds of obesity at age 6 years compared with counterparts with no SSB intake.11 Among older children, previous evidence shows that parental SSB consumption is strongly associated with child SSB consumption, emphasizing a need to consider both parental and infant health behaviors in obesity-prevention interventions.12

According to the theory of planned behavior, positive and negative attitudes toward behaviors, including drinking behaviors, precede intention and execution of behaviors.13 Because of the disproportionate burden of childhood obesity among low-income families, understanding parental attitudes, parental behaviors, and infant behaviors related to SSB consumption during the first 1000 days of life will inform the development of interventions to promote healthy beverage intake early in life among low-income populations.

We examined the associations of parental SSB attitudes with SSB consumption during the first 1000 days of life. We hypothesized that parental attitudes that are more negative toward SSBs will be associated with lower SSB consumption during the first 1000 days of life for both parents and infants.

METHODS

We performed a cross-sectional study of 394 families enrolled in the New York City First 1,000 Days study, a study of parent and infant health during pregnancy and infancy in northern Manhattan. In the New York City First 1,000 Days study, we performed an explanatory, sequential mixed methods (quantitative followed by qualitative) study to examine attitudes and perceptions of beverage consumption among Hispanic/Latino families in low-income northern Manhattan neighborhoods with the highest prevalence of childhood obesity in New York City.14 We present results from the quantitative research study, in which we sought to estimate prevalence of SSB consumption and the relationship of parental SSB attitudes with SSB consumption for themselves and their infants.

We recruited families from consecutive visits at a multisite Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) serving northern Manhattan in March 2017 to June 2017. Study staff obtained written informed consent from eligible adult WIC participants who were pregnant, a legal caregiver of an infant younger than 2 years, or both. We considered adult participants—henceforth called parents—eligible for the study if they or their partner were pregnant or had a child younger than 2 years; were enrolled in WIC; and were able to respond to questions in English or Spanish.

We excluded pregnant women with chronic medical conditions that may affect their nutrition behaviors and parents whose eligible child has chronic conditions that interfere with growth or feeding. Study staff who were fluent in both English and Spanish completed research visits in person. All consent and survey materials were translated into Spanish. Study participants received a $20 gift certificate for their time.

Measurements

Main outcome: parental and infant sugar-sweetened beverage consumption.

For the main parental and infant outcome of SSB consumption, we defined SSBs as all beverages with added sugar. These include regular sodas, fruit or juice drinks, sport drinks (e.g., fluid or electrolyte replacement beverages), energy drinks, and other beverages that contain added caloric sweeteners, such as flavored milks and sweetened teas or coffees.15 Because 100% fruit juice does not include added sugars, we did not include it as an SSB. To measure parental beverage consumption, study staff administered the 15-item Beverage Intake Questionnaire (BEVQ-15), a validated and reliable quantitative beverage frequency questionnaire.16 We used container samples to assist with parental response for serving size information. The BEVQ-15 can be administered in about 2 minutes to participants with a fourth-grade readability score.16 Quantitative beverage frequency questionnaires have evidence as valid and reliable tools for measuring SSB consumption in Hispanic/Latino populations.17 Parents reported frequency of consumption and serving sizes for each of the 15 items over the past month.

We used parents’ report of habitual infant beverage frequency and quantity per serving to measure infant beverage consumption. Study staff administered a validated quantitative beverage frequency questionnaire from the Iowa Fluoride Study18 and asked about breastmilk and formula use.19 We used container samples to assist with parental response for serving size information for infants.

For parents and infants, we estimated habitual daily intake of SSBs in ounces and kilocalories using methodology previously described that includes use of food composition tables.16,20 For parents, we calculated median interquartile (IQR) SSB calories as the main outcome. Because of expert recommendations for infants to avoid added sugars—including SSBs—before age 2 years,21,22 we classified infant SSB consumption dichotomously (any vs none). We also estimated daily consumption of 100% fruit juice, cow’s milk, unsweetened coffee and tea, artificially sweetened beverages, water, and other beverages to calculate total beverage ounces and kilocalories consumed daily. For infants, we additionally calculated formula and human (i.e., breast) milk consumption from a bottle or cup for inclusion in total beverage calculations. We were specifically interested in SSB consumption and—because of the low frequency of exclusively breastfeeding in the study sample (15% exclusively breastfeeding) and wide variety in volumes and calories consumed with breastfeeding at the time of the research visit—we did not include breastmilk from breastfeeding in beverage calculations for infants.

Other measures.

For the main exposure of parental SSB attitudes, trained study staff administered questionnaires at the time of the in-person research visit. We modified 4 questions from a survey of adult SSB beliefs and attitudes to focus on pregnancy and infancy.23 Specifically, we asked parents how much they agree or disagree with the following statements that we modified to specify that the questions were for pregnancy and infancy: (1) “Sugary drinks are part of an active lifestyle”; (2) “It is okay to drink sugary drinks while pregnant”; (3) “Sugary drink consumption can negatively affect my child’s health”; and (4) “Drinking sugary drinks increases the risk of gaining too much weight.” Possible responses ranged from strongly agree to strongly disagree on a 5-point Likert scale. We assigned a value from 1 to 5 to responses, coded as “strongly agree” = 1 to “strongly disagree” = 5 for questions 1 and 2, and we reverse-coded for questions 3 and 4. We created a parental SSB attitude score by calculating the average score for parental responses to all 4 questions.

For covariates, we collected study participant age, sex, race/ethnicity, pregnancy status, marital status, highest education level for self and partner (if applicable), and household income. For parents with infants younger than 2 years, we obtained information on child age, sex, and race/ethnicity.

Statistical Analysis

First, we examined the distribution of components of the parental SSB attitude score, parental SSB and other beverage consumption, and infant SSB and other beverage consumption. We then examined the bivariate relationships of parental SSB attitude score with parental SSB (in kcals) and (any) infant SSB consumption. In multivariable models, we included covariates that were of interest on the basis of previous literature demonstrating a relationship with childhood obesity risk factors regardless of statistical significance in the current data.

We used quantile regression to estimate the relationship of parental SSB attitude scores with the median of parental daily SSB calories consumed. The parent-adjusted model (model 1) accounted for parent age at the time of the research visit and race/ethnicity. For the parent and socioeconomic status–adjusted model (model 2), we additionally adjusted for household income level and highest parental education level. In the fully adjusted parent model (model 3), we additionally adjusted the parent and socioeconomic status–adjusted model for parental pregnancy status.

For the subset with infants, we used logistic regression to examine the relationship of parental SSB attitude scores with any infant SSB consumption. In the child-adjusted model (model 1), we adjusted for child age at the time of research visit and child race/ethnicity. In the child and socioeconomic status–adjusted model (model 2), we also adjusted for household income and highest parental education level. Because infants who consumed SSBs were older than were those who did not, we performed sensitivity analyses restricted to children aged 12 months or older. We conducted all analyses using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). All tests were 2-sided. We considered a P value of < .05 statistically significant.

RESULTS

Table 1 displays the characteristics of the parents (pregnant women and nonpregnant parents of infants) and subsample of infants. Of the 394 parents interviewed, 31% were pregnant and 71% were parents of a child younger than 2 years. The majority of parents were Hispanic/Latino and female. For the subsample of infants, about half were male, median age was 6 months, and most were Hispanic/Latino. Approximately 8755 potentially eligible parents had visits at the main WIC site during the recruitment period, of whom 407 came for recruitment, and 400 were eligible and enrolled. The completion rate of interviews was 99%.

TABLE 1—

Parent and Child Characteristics According to Beverage Consumption Among Families Enrolled in WIC: New York City First 1,000 Days Study, 2017

| Beverage Intake, Median (IQR) or No. (%) | |||

| Variable | Overall | No SSB | Any SSB |

| Parent/Family characteristic | |||

| Total sample size | 394 | 45 | 349 |

| Parental age, y | 29 (24–34) | 30 (25–33) | 28 (24–34) |

| Parental sex, female | 390 (99) | 45 (100) | 345 (99) |

| Pregnant parent | 122 (31) | 15 (33) | 107 (31) |

| Gestational age, wka | 27 (16–33) | 26 (23–33) | 27 (16–33) |

| Highest parental education, any college or above (either parent) | 217 (55) | 26 (58) | 191 (55) |

| Annual household income, $ | |||

| < 15 001 | 155 (39) | 19 (42) | 136 (39) |

| 15 001–35 000 | 134 (34) | 14 (31) | 120 (34) |

| > 35 000 | 41 (10) | 3 (7) | 38 (11) |

| Unknown | 64 (16) | 9 (20) | 55 (16) |

| Maternal race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White/other | 11 (3) | 2 (4) | 9 (3) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 13 (3) | 1 (2) | 12 (3) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 370 (94) | 42 (93) | 328 (94) |

| Infant characteristic | |||

| Total sample size | 281 | 198 | 83 |

| Boyb | 143 (51) | 102 (52) | 41 (49) |

| Age, months | 6 (3–15) | 4 (1–9) | 17 (13–20) |

| Infant race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 11 (4) | 9 (5) | 2 (2) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 7 (2) | 6 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 263 (94) | 183 (92) | 80 (96) |

Note. IQR = interquartile range; SSB = sugar-sweetened beverage; WIC = Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Population is n = 394 WIC families.

Limited to 121 pregnant participants, excluding 1 participant in the any SSB group with a missing value.

Limited to 280 parents with infants, excluding 1 infant in the no SSB group with a missing value.

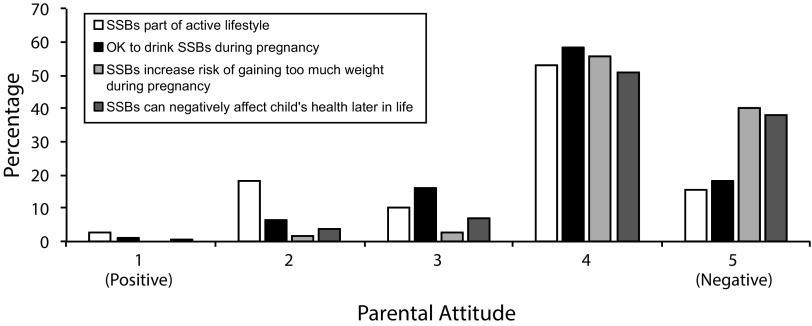

Figure 1 shows the distribution of parental responses to items in the SSB attitude score. Parents had most negative attitudes most often for the SSB attitude score item stating that drinking SSBs can increase the risk of gaining too much weight during pregnancy and infancy (40%; Figure 1). Median parental SSB attitude score was 16 (range = 10–20; IQR = 15–17), indicating that parents tended to have negative attitudes toward SSB consumption.

FIGURE 1—

Parental Attitudes Toward Sugar-Sweetened Beverage (SSB) Consumption During Pregnancy and Infancy: New York City First 1,000 Days Study, 2017

Note. Data are from 394 families enrolled in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children during the first 1000 days of life.

Parental Beverage Outcomes

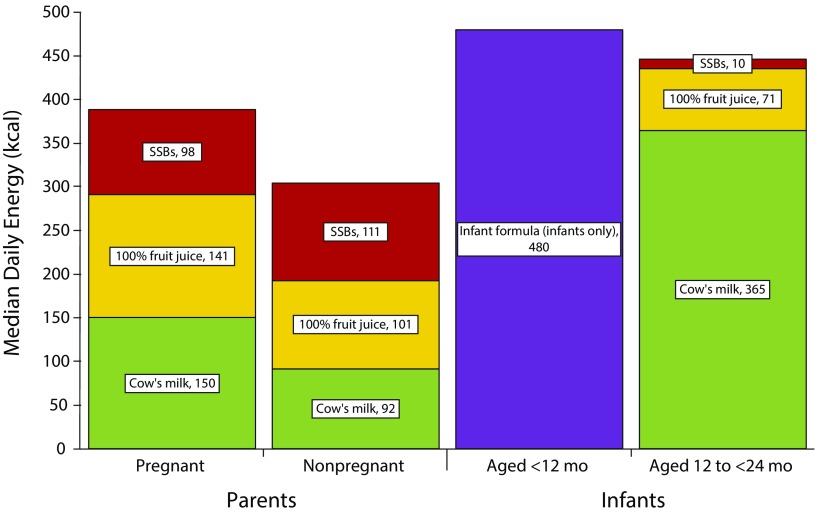

Overall, 89% of parents (combined pregnant women and parents of infants) habitually drank any SSBs (Table 1). Parents drank median 10 ounces of SSBs daily, amounting to 105 kilocalories per day. In terms of beverages other than SSBs, the bulk of overall parental beverage consumption was from water (24 ounces), cow’s milk (8 ounces), and 100% fruit juice (6 ounces). Overall, SSBs constituted the greatest number of beverage calories consumed by parents, followed by 100% fruit juice (median 101 kcal) and cow’s milk (median 92 kcal). Parents overall did not habitually consume diet or artificially sweetened beverages. For the subset of parents who were pregnant mothers (Figure 2), the greatest number of beverage calories were from cow’s milk, followed by 100% fruit juice, and then SSBs. For the subset of nonpregnant parents, beverage calorie sources were similar to the overall results.

FIGURE 2—

Habitual Parental and Infant Daily Sugar-Sweetened Beverage (SSB) and Other Beverage Caloric Consumption: New York City First 1,000 Days Study, 2017

Note. Data are from 394 parents and 281 infants during the first 1000 days of life.

Table 2 shows regression model results for the association of parental SSB attitude scores with parental SSB consumption. In unadjusted models, a higher parental SSB attitude score (i.e., more negative attitudes) was associated with fewer SSBs. After adjusting for parental age and race/ethnicity, results persisted. Results were slightly attenuated after additionally adjusting for socioeconomic factors (household income, highest parental education status), and the strength of the relationship was minimally attenuated by additionally adjusting for parental pregnancy status. In multivariable adjusted regression models, each point higher parental SSB attitude score was associated with median 14.5 kilocalories (95% CI = −22.6, −6.4) fewer calories from SSBs consumed by parents.

TABLE 2—

Association of Parental Sugar-Sweetened Beverage (SSB) Attitude Scores With Parent and Infant Habitual SSB Consumption and Weight Status During the First 1000 Days: New York City First 1,000 Days Study, 2017

| Outcome | b (95% CI) or OR (95% CI) |

| Parental outcomesa | |

| Parental SSB attitude score | |

| Unadjusted | −17.0 (–26.7, −7.2) |

| Parent-adjusted modelb | −17.7 (–26.4, −9.0) |

| Parent and SES-adjusted modelc | −15.5 (–23.7, −7.3) |

| Fully adjusted modeld | −14.5 (–22.6, −6.4) |

| Infant outcomese | |

| Parental SSB attitude score | |

| Unadjusted | 0.86 (0.76, 0.98) |

| Child-adjusted modelf | 0.84 (0.71, 0.99) |

| Child and SES-adjusted modelg | 0.85 (0.71, 1.02) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; SES = socioeconomic status.

Parameter estimates of median SSB calories consumed from quantile regression models. Data are from 394 parents.

Parent-adjusted model: adjusted for parent age at time of research visit and race/ethnicity.

Parent and SES-adjusted model: parent model additionally adjusted for household income and parental education.

Fully adjusted model: parent and SES-adjusted model additionally adjusted for pregnant parent status.

OR of any habitual infant SSB consumption compared with no SSB consumption from logistic regression models. Data are from 281 parents with infants.

Child-adjusted model: adjusted for child age at time of research visit and race/ethnicity.

Child and SES-adjusted model: child-adjusted model additionally adjusted for household income and parental education.

Infant Beverage Outcomes

Among the subset of 281 parents with infants, 30% reported that their infants habitually drank any SSBs. Median age was higher among infants who drank SSBs than among those who did not (Table 1). Because of the difference in median age among infants who consumed SSBs compared with those who did not, we examined the frequencies and amounts of beverages habitually consumed by infants in a bottle or cup according to age category. Among infants younger than 12 months, 7% drank any SSBs, 11% drank any 100% fruit juice, 1% drank cow’s milk, 41% drank water, 87% drank infant formula, and 22% drank breastmilk in a bottle. The median habitual daily consumption in ounces and calories was 0 for all beverage categories except infant formula (median 480 kcal) among infants younger than 12 months (Figure 2). For the subset of infants aged 12 months and older, most habitually consumed SSBs (66%), 100% fruit juice (86%), cow’s milk (78%), and water (100%), and a minority consumed infant formula (22%) and breastmilk (2%). For infants aged 12 months and older, the greatest number of habitual beverage calories consumed was from cow’s milk (median 365 kcal), followed by 100% juice (median 71 kcal), and then SSBs (median 10 kcal).

In regression models, each point higher parental SSB attitude score resulted in lower odds of infants drinking any SSBs (Table 2). Results were of borderline statistical significance after adjusting for child age and race/ethnicity, but additionally adjusting for household income and parental education widened CIs and included the null. In sensitivity analyses restricted to infants aged 12 months and older, we found similar results.

DISCUSSION

In this study of low-income, predominantly Hispanic/Latino families during the first 1000 days of life, we found that parents with more negative attitudes toward SSB consumption consumed fewer SSB calories. Also, more negative parental attitudes toward SSB consumption were associated with lower likelihood of infant SSB consumption, and socioeconomic factors accounted in part for these results. Overall, our findings support targeting parental attitudes toward SSBs during the first 1000 days of life as part of efforts to reduce maternal SSB consumption during pregnancy and prevent introduction of SSBs among infants in low-income communities. In our study, 89% of parents and 66% of the subset of infants aged 12 to less than 24 months habitually consumed SSBs.

These estimates are higher than are those in nationally representative studies. For example, among non-Mexican Hispanic adults, a recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) study found that 63% of adults aged 20 to 39 years consumed SSBs.24 In a different NHANES study, 54% of infants aged 12 to less than 24 months drank SSBs.10 A direct comparison between studies is not possible because of differences in methodology. However, substantial evidence demonstrates that pregnancy and infancy are critical periods for the development of obesity and its chronic health complications later in life and that SSB consumption during these periods is a risk factor for later obesity in children.5,8 The high prevalence of parental and infant SSB consumption in this study and others lends support to the need for interventions to promote healthy beverage consumption in pregnancy and infancy.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to examine parental attitudes toward SSBs during pregnancy and infancy. Although previous research has shown a link between SSB attitudes—including knowledge—and SSB consumption among adults and older children or adolescents,25–27 we know of no studies that have examined attitudes toward SSB consumption during pregnancy or infancy. By contrast to our findings, a recent study of Hispanic adults found overall low knowledge of SSB health effects, but knowledge of SSB health effects was not associated with high SSB consumption.28

In a different study, parental consumption of SSBs was associated with adolescent SSB consumption, but neither parental nor adolescent knowledge of SSB health effects was associated with consumption.29 This and other previous work suggest that targeting knowledge alone may not be sufficient to shift behavior. Attitude is a multifaceted construct that influences behavioral intention, and knowledge is only 1 of many factors that influence attitude. Our findings build on previous literature to suggest that understanding drivers of parental SSB attitudes besides knowledge—such as perceived beverage attributes and cost—will inform future health messaging and policy interventions to reduce SSB consumption in the first 1000 days of life.

Furthermore, in the context of literature showing a link between parental and child SSB consumption, our findings of (1) high proportion of parental SSB consumption, (2) high proportion of infant SSB consumption, and (3) an association of negative parental SSB attitudes with parental and infant SSB consumption support the need to include parental behavior modification in efforts to promote healthy infant beverage consumption.

Overall, we found that parental attitudes leaned negative toward SSBs. Attitudes toward SSBs did not fully explain SSB consumption for parents or infants. Although attitudes toward SSBs have consistently been identified as important in determining behaviors related to diet and beverage consumption, other factors can influence beverage consumption. In qualitative research among young adults and children, taste preference was a major driving factor for SSB consumption.30,31

Humans are born with an inherent preference for sweet taste, and infancy is a period for learning food and beverage preferences. SSB consumption during the first year of life is linked to SSB consumption later in childhood,9 and some evidence shows a role for child taste preferences influencing caretakers’ attitudes toward beverages.26 Thus, early introduction of sweet beverages could both influence parental attitudes and propagate later consumption of SSBs. According to the theory of planned behavior, perceived social norms and perceived behavioral control precede behavioral intentions, and a study of adults found that these additional components, along with attitudes, influenced SSB consumption.25 Thus, although targeting parental attitudes may play a role in curbing SSB consumption, additional intervention components may need to target broader populations—such as extended family, friends, and community members—to influence perceived social norms. Also, parental self-efficacy of behavioral control may need to be targeted through coaching or skills building in interventions.

We found that more negative parental SSB attitudes were linked to a lower likelihood of SSB consumption for infants, but findings were attenuated after adjusting for socioeconomic factors. These results suggest that factors related to socioeconomic status could account for the relationship between parent attitudes toward SSBs and their introduction of SSBs to infants. In low-income neighborhoods, the availability of high-calorie, nutrient-poor foods contributes to consumption of these foods,32 and “food swamps”—areas of high density of food retail establishments serving fast food or junk food—predict adult obesity prevalence.33 Additionally, the food and beverage industry invests millions of dollars to target parents and children early in life to develop brand preference and disproportionately targets television advertising to racial/ethnic minority and low-income populations.34 Thus, it may be possible that high availability and greater exposure to advertising among low-income groups could affect both parental attitudes and behaviors related to infant consumption.

Limitations and Strengths

Our study has some limitations. Social desirability bias could influence parental report of their attitudes or beverage consumption. To reduce the likelihood of this bias, study staff who were ethnically concordant and native Spanish speakers were trained in culturally sensitive administration of interview questions. To reduce the risk of recall bias, we used validated quantitative tools to obtain information on habitual beverage consumption. Because of the cross-sectional nature of our design, we cannot determine causality. Finally, we modified attitude questions to fit the life course periods of interest—pregnancy and infancy—and these questions have not undergone formal validation testing with these modifications. However, the modifications were minor and were made to specify that the period of interest was pregnancy and infancy.

This study has many strengths. First, our study is the first, to our knowledge, to examine the relationship between parental attitudes toward and consumption of SSBs during pregnancy and infancy. Second, with more than 7.6 million participants,35 WIC is a platform for promoting maternal–child health among low-income families early in life. We also studied families in a geographic location with the highest prevalence of childhood obesity in New York City.14 Thus, our study sample is well suited to provide information that is relevant to low-income, Hispanic families, a group disproportionately burdened by childhood obesity, in a setting that is poised to intervene early in life. Finally, we used a contemporary study sample to provide new information on attitudes and SSB consumption during a critical period in the life course.

Public Health Implications

We found that parents with more negative attitudes toward SSBs habitually consumed fewer daily SSB calories and were less likely to have infants who drank SSBs. Considering that the substantial evidence that frequent SSB consumption during these critical periods in the life course can adversely affect later child health, efforts to curb SSB intake during pregnancy and to avoid introduction during infancy are needed. In the future, better understanding of the drivers of negative parental SSB attitudes will inform the development of policy interventions such as the modification of beverage attributes (e.g., taste and cost) or shifts in marketing and advertising of infant and toddler products to reduce SSB consumption in the first 1000 days of life. Our results support the need for future interventions that target parental attitudes toward SSBs to promote healthy beverage consumption during the first 1000 days of life.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH; award K23DK115682) and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation New Connections Grants Through Healthy Eating Research Program (RWJF grant 74198). E. Taveras is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grant K24 DK10589).

The New York State Department of Health provided conceptual support for the study.

Note. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or any other funders.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The Columbia University Medical Center institutional review board approved all study protocols.

Footnotes

See also Galea and Vaughan, p. 1590.

REFERENCES

- 1.Non-communicable Disease Risk Factor Collaboration. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2627–2642. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG et al. Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988–1994 through 2013–2014. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2292–2299. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, CL Ogden. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2015–2016. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2017. NCHS Data Brief no. 288. [PubMed]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: obesity among low-income, preschool-aged children—United States, 2008–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(31):629–634. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2013;382(9890):427–451. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malik VS, Pan A, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(4):1084–1102. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.058362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillman MW, Rifas-Shiman SL, Fernandez-Barres S et al. Beverage intake during pregnancy and childhood adiposity. Pediatrics. 2017;140(2):e20170031. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park S, Pan L, Sherry B, Li R. The association of sugar-sweetened beverage intake during infancy with sugar-sweetened beverage intake at 6 years of age. Pediatrics. 2014;134(suppl 1):S56–S62. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0646J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miles G, Siega-Riz AM. Trends in food and beverage consumption among infants and toddlers: 2005–2012. Pediatrics. 2017;139(6):e20163290. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan L, Li R, Park S, Galuska DA, Sherry B, Freedman DS. A longitudinal analysis of sugar-sweetened beverage intake in infancy and obesity at 6 years. Pediatrics. 2014;134(suppl 1):S29–S35. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0646F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sonneville KR, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman KP, Gortmaker SL, Gillman MW, Taveras EM. Associations of obesogenic behaviors in mothers and obese children participating in a randomized trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20(7):1449–1454. doi: 10.1038/oby.2012.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York. Obesity among public elementary and middle school students. Available at: http://data.cccnewyork.org/data/table/94/obesity-among-public-elementary-and-middle-school-students#94/143/9/1/d. Accessed March 8, 2018.

- 15.Story M, Fox F, Corbett A Recommendations for healthier beverages. 2013. Available at: https://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2013/rwjf4048522013. Accessed February 1, 2017.

- 16.Hedrick VE, Savla J, Comber DL et al. Development of a brief questionnaire to assess habitual beverage intake (BEVQ-15): sugar-sweetened beverages and total beverage energy intake. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(6):840–849. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lora KR, Davy B, Hedrick V, Ferris AM, Anderson MP, Wakefield D. Assessing initial validity and reliability of a beverage intake questionnaire in Hispanic preschool-aged children. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(12):1951–1960. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.06.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marshall TA, Eichenberger Gilmore JM, Broffitt B, Stumbo PJ, Levy SM. Relative validity of the Iowa Fluoride Study targeted nutrient semi-quantitative questionnaire and the block kids’ food questionnaire for estimating beverage, calcium, and vitamin D intakes by children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(3):465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fein SB, Labiner-Wolfe J, Shealy KR, Li R, Chen J, Grummer-Strawn LM. Infant Feeding Practices Study II: study methods. Pediatrics. 2008;122(suppl 2):S28–S35. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1315c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hedrick VE, Comber DL, Estabrooks PA, Savla J, Davy BM. The Beverage Intake Questionnaire: determining initial validity and reliability. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(8):1227–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vos MB, Kaar JL, Welsh JA et al. Added sugars and cardiovascular disease risk in children: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(19):e1017–e1034. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perez-Escamilla R, Segura-Perez S, Lott M. Feeding guidelines for infants and young toddlers: a responsive parenting approach. 2017. Available at: https://healthyeatingresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/her_feeding_guidelines_report_021416-1.pdf. Accessed October 7, 2018.

- 23.Ruiz R, Friedman RR, Hacker G, Peña B, Novak N, Patlovich K. How sweet it is: perceptions, behaviors, attitudes, and messages regarding sugary drink consumption and its reduction. 2012. Available at: http://www.interlexusa.com/736-ILX-SSBresearchreport.pdf. Accessed October 7, 2018.

- 24.Bleich SN, Vercammen KA, Koma JW, Li Z. Trends in beverage consumption among children and adults, 2003–2014. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2018;26(2):432–441. doi: 10.1002/oby.22056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zoellner J, Estabrooks PA, Davy BM, Chen YC, You W. Exploring the theory of planned behavior to explain sugar-sweetened beverage consumption. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44(2):172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pettigrew S, Jongenelis M, Chapman K, Miller C. Factors influencing the frequency of children’s consumption of soft drinks. Appetite. 2015;91:393–398. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.04.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zytnick D, Park S, Onufrak SJ. Child and caregiver attitudes about sports drinks and weekly sports drink intake among U.S. youth. Am J Health Promot. 2016;30(3):e110–e119. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.140103-QUAN-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park S, Ayala GX, Sharkey JR, Blanck HM. Knowledge of health conditions associated with sugar-sweetened beverage intake is low among US Hispanic adults. Am J Health Promot. 2018 doi: 10.1177/0890117118774206. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lundeen EA, Park S, Onufrak S, Cunningham S, Blanck HM. Adolescent sugar-sweetened beverage intake is associated with parent intake, not knowledge of health risks. Am J Health Promot. 2018 doi: 10.1177/0890117118763008. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Block JP, Gillman MW, Linakis SK, Goldman RE. “If it tastes good, I’m drinking it”: qualitative study of beverage consumption among college students. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(6):702–706. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Battram DS, Piché L, Beynon C, Kurtz J, He M. Sugar-sweetened beverages: children’s perceptions, factors of influence, and suggestions for reducing intake. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2016;48:27–34.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boone-Heinonen J, Gordon-Larsen P, Kiefe CI, Shikany JM, Lewis CE, Popkin BM. Fast food restaurants and food stores: longitudinal associations with diet in young to middle-aged adults: the CARDIA study. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(13):1162–1170. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooksey-Stowers K, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Food swamps predict obesity rates better than food deserts in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(11):E1366. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14111366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Powell LM, Wada R, Kumanyika SK. Racial/ethnic and income disparities in child and adolescent exposure to food and beverage television ads across the US media markets. Health Place. 2014;29:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Services. Nutrition assistance programs report. 2016. Available at: http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/datastatistics/may-performance-report-2016.pdf. Accessed October 7, 2018.