Abstract

Objective

The study examines relationships between physical activity levels and income status of working-age city residents.

Methods

The study was carried out in the years 2014 and 2015 in Wrocław, Poland. The study sample comprised 4332 participants (2276 women; 2056 men) aged 18 to 64 years. Respondents' habitual physical activity levels were measured with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF), while their income status was assessed with author's own Socio-Economic Status of Working-Age People Questionnaire (S-ESQ).

Results

The results revealed positive correlations between the level of physical activity and income status of male and female working-age residents of Wrocław. The highest physical activity levels were noted among respondents with a steady income, as well as among respondents with the highest income and savings and with no debts. The odds for respondents' above average physical activity levels were the greatest in women with the highest income and with savings and in debt-free men and women.

Conclusion

Effective actions should be developed aimed at improvement of physical activity levels of people in an adverse financial situation.

1. Introduction

Undertaking properly adjusted physical activity by working-age populations is highly significant for their health status in its physical, psychical, and social domains. Significant positive correlations were empirically proven between physical activity levels and the function of locomotive [1, 2], circulatory [3, 4], respiratory [5], digestive [6], immune [7], and nervous [8] systems. Researchers also confirmed the positive impact of physical activity on anxiety and depression levels [9], cognition [10], optimism [11], and quality of life [12–15]. Physical exercises of appropriate frequency, volume, and intensity play a crucial role in disease prevention as well as in rehabilitation allowing full recovery and return to professional life after diseases, traumas, or exhaustion [16, 17].

Following the ecological model proposed by Sallis et al. [18] an individual's physical activity is determined by different sets of variables: intrapersonal, interpersonal, environmental, regional, national, and global. The first set includes, apart from biological determinants (genes; health status) and psychological determinants (motivation, cognition, values, and emotions), also socio-economic factors, i.e., one's age, sex, education, occupation, and income status.

The present study attempts to identify relationships between physical activity levels of working-age individuals and their income status. Results of earlier studies examining these relationships have been rather inconclusive. Chung et al. [19] analyzed the levels of physical activity of adult Americans in relation to their wealth and occupation status in the years 1996-2002. The study showed that individuals with the annual household income above 125 thousand dollars featured higher physical activity levels than people with lower household income levels. Also Kim and So [20] in their study of a Korean population noted a strong relationship between higher physical activity levels among people with a higher income. A study of Warsaw residents by Biernat [21] revealed that the odds of meeting WHO recommended levels of physical activity increased with the residents' higher income status. The odds of fulfillment the WHO standards among people with the highest income were almost twice as high as among people with the lowest income.

Studies of physical workers from Brazil [22] and China [23] revealed the highest levels of physical activity among individuals with the highest and the lowest income. Kaewthummanukul and Brown [24] and Van Stralen et al. [25] noted that economic status was not significantly correlated with undertaken physical activities, whereas Sallis et al. [26] found negative correlations between income status and physical activity levels among adults.

Researchers so far have investigated study participants' financial situation only in terms of household income or income status of particular household members; however, no other significant variables have been considered. The aim of the present study was to identify the strength and direction of relationships between physical activity levels and such determinants of financial situation as having steady income, per capita income, savings, and indebtedness in a working-age population from Wrocław, Poland.

2. Methods

The study was carried out between 2014 and 2015 in the city of Wrocław (pop. 640 000) in Poland. The research project had been given a positive opinion by the Commission of Bioethics at the University of Physical Education in Wrocław. The research sample comprised 4,332 people (2,276 women; 2,056 men) aged 18-64 years, i.e., about 1% of the Wrocław working-age population. The respondents were divided into the following age ranges: 18-24 years (14%), 25-34 years (26%), 35-44 years (20%), 45-54 years (17%), and 55-64 years (23%). Among the respondents 31% were white-collar workers, 26% manual workers, 14% self-employed and students, 9% unemployed, and 6% homemakers. Almost 81% of the Wrocław residents under study had a steady income. 45% had the average monthly income per capita from USD 271 to 542; 28% below USD 271; and 27% more than USD 542. About 46% had money savings, and nearly 54% had no spare funds whatsoever. 49% of respondents were in debt, and 51% had no financial liabilities. The differences in financial status between the male and female respondents were statistically significant (p < 0.001) (Table 1); thus the analysis of relationships between physical activity levels and income status was carried out for men and women separately.

Table 1.

Income status of working-age residents from Wrocław.

| Variables | Category | Total | Women | Men | χ 2 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 4332 | n = 2276 | n = 2056 | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| Steady income | Yes | 3494 | 80.7 | 1765 | 77.5 | 1729 | 84.1 | 29.68 | < 0.001 |

| No | 838 | 19.3 | 511 | 22.5 | 327 | 15.9 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Per capita income | Below USD 271 | 1214 | 28.0 | 750 | 33.0 | 464 | 22.6 | 137.28 | < 0.001 |

| USD 271-542 | 1957 | 45.2 | 1078 | 47.4 | 879 | 42.8 | |||

| Above USD 542 | 1161 | 26.8 | 448 | 19.7 | 713 | 34.7 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Savings | Yes | 2009 | 46.4 | 907 | 39.9 | 1102 | 53.6 | 82.11 | < 0.001 |

| No | 2323 | 53.6 | 1369 | 60.1 | 954 | 46.4 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Indebtedness | Yes | 2107 | 48.6 | 1049 | 46.1 | 1058 | 51.5 | 12.47 | < 0.001 |

| No | 2225 | 51.4 | 1227 | 53.9 | 998 | 48.5 | |||

Notes: χ2: chi-squared independence test; p: chi-squared independence test probability value.

The study used the auditorium survey methodology. The respondents' physical activity and financial situation were assessed with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF) in the Polish language version [27] and author's own Socio-Economic Status of Working Age People Questionnaire (S-ESQ).

The data from IPAQ-SF was used to determine respondents' energy expenditure of physical activity (EEPA) (quantitative index) and physical activity level (PAL) (qualitative index). The EEPA expressed in MET-min/week was calculated as a total of physical activities at three intensity levels performed by respondents on a weekly basis [27]. The PAL was calculated as a scaled up (adapted) EEPA index. The reference category, in the groups of men and women separately, was the EEPA median value (Me EEPA). The two PAL categories were average PAL (EEPA ≤ Me EEPA) and above average PAL (EEPA > Me EEPA).

The S-ESQ was used to determine four independent variables of the income status of Wrocław residents: having a steady income (YES, NO), per capita income in a household (< USD 271, USD 271-542, USD > 543), savings (YES, NO), and indebtedness (NO, YES).

For each variable, the size (n) and ratios (%) for the gender groups and the whole study group were estimated. As for the EEPA (dependent variable) arithmetic means and medians (Me) were calculated for the total group and groups according to particular variables of the financial situation, for men and women separately. The differences between the male and female Wrocław residents were checked with Pearson's chi-squared test (χ2). Differences in the average physical activity levels between respondents with different income status were checked with the use of the Mann-Whitney U test (Z), Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA test (H), and logistic regression analysis, separately for male and female residents. The level of statistical significance was set ex ante at α < 0.05. All statistical calculations were made with the use of IBM SPSS Statistics 20.

3. Results

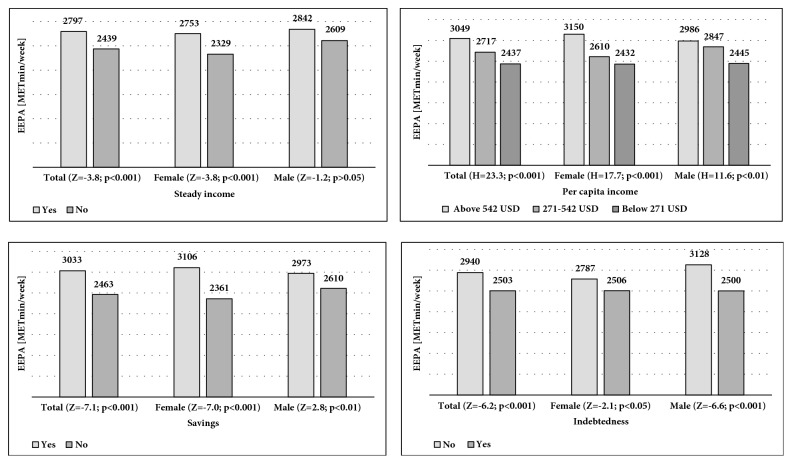

The analysis of mean EEPA results in the groups of male and female respondents with regard to having a steady income revealed significant differences in the group of women (Z = -3.8, p < 0.001). The mean EEPA among women with a steady income was 2753 MET-min/week, and among women without a steady income 2329 MET-min/week. The highest levels of physical activity were noted in women (3150 MET-min/week) and men (2986 MET-min/week) from Wrocław with incomes higher than USD 542, and the lowest in women (2432 MET-min/week) and men (2445 MET-min/week) with incomes below USD 271. The Kruskal-Wallis test results (H = 17.7, p < 0.001 in women; and H = 11.6, p < 0.01 in men) showed that mean physical activity levels in particular income groups varied significantly. The highest EEPA levels were found in women (3106 MET-min/week) and men (2973 MET-min/week) who had money savings. Their level of physical activity was significantly higher (p < 0.001 in women; p < 0.01 in men) than in respondents without savings (2361 MET-min/week in women; 2610 MET-min/week in men). The respondents' physical activity levels also differed in regard to their indebtedness (Z = -2.1, p < 0.05 for women; Z = -6.6, p < 0.001 for men). The mean EEPA (2787 MET-min/week in women; 3128 MET-min/week in men) in debt-free respondents was higher than in respondents with debt, i.e., 2506 MET-min/week and 2500 MET-min/week, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Differences in physical activity levels of respondents grouped according to variables of their income status.

Tables 2 and 3 show binomial regression models illustrating relationships between physical activity levels (PAL) (dependent variable) with income status indices of working-age Wrocław residents (independent variables). The reference category for the PAL index was its average level, i.e., below or equal to 2232 MET-min/week in women and below or equal to 2445 MET-min/week in men.

Table 2.

Relationships between physical activity level and income status variables in women.

| Variables | Category | β | SE | Wald χ2 | p-value | OR | CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -95% | 95% | |||||||

| Intercept | -0.27 | 0.11 | 6.44 | < 0.01 | ||||

| Steady incomea | Yes | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.80 | ≥ 0.05 | 1.10 | 0.89 | 1.35 |

| Per capita incomeb | USD 271-542 | -0.07 | 0.10 | 0.47 | ≥ 0.05 | 0.93 | 0.76 | 1.14 |

| above USD 542 | 0.59 | 0.18 | 10.58 | <0.001 | 1.80 | 1.26 | 2.57 | |

| Savingsc | Yes | 0.30 | 0.10 | 9.87 | < 0.01 | 1.35 | 1.12 | 1.63 |

| Indebtednessd | No | 0.22 | 0.09 | 6.34 | < 0.05 | 1.24 | 1.05 | 1.47 |

Notes: the reference category for the dependent variable is average level of physical activity. aThe reference category for steady income is NO. bThe reference category for per capita income is below USD 271. cThe reference category for savings is NO. dThe reference category for indebtedness is YES. β: assessment value of model parameters, SE: asymptotic standard error β, Wald χ2: parameter significance, p: Wald χ2 probability value, OR: odds ratio, and CI: confidence interval.

Table 3.

Relationships between physical activity level and income status variables in men.

| Variables | Category | β | SE | Wald χ2 | p-value | OR | CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -95% | 95% | |||||||

| Intercept | -0.47 | 0.13 | 12.94 | <0.001 | ||||

| Steady incomea | Yes | 0.19 | 0.13 | 2.11 | ≥ 0.05 | 1.21 | 0.94 | 1.56 |

| Per capita incomeb | USD 271-542 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.05 | ≥ 0.05 | 1.03 | 0.81 | 1.31 |

| Above USD 542 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.15 | ≥ 0.05 | 1.05 | 0.81 | 1.37 | |

| Savingsc | Yes | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.08 | ≥ 0.05 | 1.03 | 0.84 | 1.25 |

| Indebtednessd | No | 0.47 | 0.09 | 25.73 | <0.001 | 1.60 | 1.33 | 1.91 |

Notes: the reference category for the dependent variable is average level of physical activity. aThe reference category for steady income is NO. bThe reference category for per capita income is below USD 271. cThe reference category for savings is NO. dThe reference category for indebtedness is YES. β: assessment value of model parameters, SE: asymptotic standard error β, Wald χ2: parameter significance, p: Wald χ2 probability value, OR: odds ratio, and CI: confidence interval.

Among the female residents statistically significant relationships were found between the physical activity level and per capita income (p < 0.001), savings (p < 0.01), and indebtedness (p < 0.05). The odds ratio of the women's PAL being above average was 80% greater in the ones with the highest income than in those with the lowest income per capita. Women from Wrocław with money savings had 35% greater odds of above average PAL than women without any money savings. Also the odds of above average PAL in debt-free female residents from Wrocław were 24% higher than in women with debt (Table 2). In men, statistically significant correlations between the physical activity level and income status variables were only found in men with debt (p < 0.001). The odds of an above average PAL were 60% greater in debt-free men than in men with financial liabilities (Table 3).

4. Discussion

The first variable of income status, which had not been considered in earlier research, was having a steady income. Respondents with steady incomes who had higher levels of physical activity were fully employed or self-employed. The relatively short time after Poland's transformation from a centrally planned to free market economy has made only a small part of Polish society depend on a steady income from the held capital, rather than not from work. People who work full-time are better organized and generally more physically active than the unemployed [28]. They often undertake specific physical activity by commuting and performing their professional tasks. The significance of physical exercise during professional work and commuting as part of the overall physical activity of adults was proven before [29]. Researchers also noted higher physical activity levels among white and blue collar workers than among the unemployed [30].

The physical activity levels of the Wrocław residents under study were significantly different with regard to respondents' income per capita. An increase in PAL with a higher income per capita was noted by Biernat [21], Choi et al. [31], Kim and So [20], and Kari et al. [32]. Interestingly, there was an increase in conditional probability of undertaking above average physical activity in individuals with the highest income per capita. A significant increase in the physical activity level after crossing a certain income threshold was also found by Chung et al. [19]. The possibility of undertaking more physical activity by individuals with the highest incomes can be interpreted in a twofold way. On the one hand, it can be explained by the substantial contribution of physical exercises related to the performance of professional chores and of commuting to one's total physical effort. High income is often derivative of the time, complexity, and intensity of one's occupation. On the other hand, the impact of high income on pursuing leisure physical activity is also significant. This is related to the so-called backward-bending labor supply curve which demonstrates that higher wages actually entice people to work less and consume more leisure [33]. Some individuals with high incomes experience the need to have more leisure. With a higher income employees can reduce their work time, e.g., by cutting extra hours or working part-time, affording free weekends, going on vacation more than once a year, or even considering an earlier retirement. On the other hand, individuals with a low income sometimes use part of their free time for extra-paid work. This may allow them to fully meet all household needs but also deplete their energy resources that can be otherwise utilized for undertaking free-time physical activity. Thanks to a high income one is able to purchase various goods and services directly (e.g., gym subscriptions) or indirectly (e.g., transportation to and from physical exercise facilities). The above can be confirmed by research into quality of life showing that in 2015 the percentage of adult Poles spending their leisure time actively (walking and practicing outdoor leisure activities or sports) increased in particular income quintile groups [34]. Positive correlations between leisure physical activity and income status were also found by Jurakic et al. [35], Piko and Keresztes [36], and Stamm and Lamprecht [37].

Other indices allowing a complex assessment of respondents' economic situation are savings and indebtedness. Apart from current income (wages, social benefits, financial aid, rentals, etc.) household wealth is also determined by capital revenue, money savings, and accumulated material assets (e.g., real estate, works of art, jewelry, and consumer durables). The Wrocław residents with savings were more physically active than residents without savings. In 2015, 45% of Poles had money savings. The majority of them had savings amounting to one to three monthly salaries [38]. In view of the above it can be concluded that in the Polish economic reality having savings is still the preserve of a rather narrow group of affluent individuals. In fact, Poland constitutes a rather specific case. The national average propensity to save, i.e., savings rate, in Poland is both lower than in more economically advanced countries and in other Central and Eastern European countries at a similar economic level [38]. The other group of people with money savings are those whose income is not high, but who display such character traits as thriftiness, sense of control of one's own life, and foresightedness. These traits may also determine health-related behaviors including properly adjusted physical activity [39, 40].

The volume of physical activity undertaken by adult residents of Wrocław was also significantly affected by their indebtedness. Debt-free residents, compared with residents with debts, had also higher odds to reach an above average level of physical activity. Indebtedness is currently a serious problem in many Polish households: in 2015 about 32% of Poles were in debt. For most of them their debt exceeded the annual household income. The most frequent forms of debt include bank credits and loans, e.g., real estate mortgages, home renovation loans, or consumer durables loans [38]. The necessity to pay debts, regardless of debtors' financial status, always negatively affects the debtor's income status and fulfilment of needs. In the first place, potential savings are those for addressing further needs whose nonfulfilment is not health- or life-threatening, e.g., leisure needs, including physical activity needs [41]. Indebtedness also contributes negatively to one's functioning in social life and lowers one's quality of life, which is also significant for health-related behaviors, including undertaking physical activity, by working-age people [14, 15, 42, 43].

The present study has its strong and weak points. One of the first strong points is the much broader age range of the respondents (18-64 years) than in earlier studies. Only few studies had also focused on Poland or other countries of Central Europe. A novel contribution of the present study is also the focus on relationships of physical activity with such economic variables as steady income, savings, and indebtedness. The consideration of this complex set of variables permitted a comprehensive assessment of relationships between the physical activity and income status of working-age individuals that had not been attempted before in available literature. The study also makes use of novel methods of data analysis, especially in reference to the PAL index categories identified on the basis of descriptive statistics (intragroup differences between the physical activity levels of Wrocław residents).

A weak point of the present research is the confinement of the study area to a single city. Future studies should cover the entire area of Poland and other Central European countries. A certain shortcoming of the present study is the use of the short version of the IPAQ. Again future research should take advantage of measurements of physical activity in various areas of life, e.g., during leisure, work, commuting, or performing domestic chores, since the strength and directions of correlations with different socio-economic factors may vary [29]. A certain shortcoming of the present study was the analysis of the impact of particular socio-economic variables separately from one another. Future research should focus on correlations of the physical activity of working-age individuals with particular socio-economic factors as well as with the whole socio-economic situation of a household. Aggregate socio-economic indices were earlier considered by authors, but they were mostly used to examine the effects of socio-economic status on the somatic and motor development of young people [44–46]. Other indices of respondents' socio-economic status to be considered in the future should also encompass levels of steady income, amount of money savings, and different types of debts, e.g., short- or long-term.

5. Conclusion

The study results indicate positive relationships between physical activity levels and financial situation of a working-age population from Wrocław, Poland. The highest levels of physical activity were found among both male and female respondents who had the highest income, were debt-free, and had money savings. The study also showed that the odds for above average physical activity levels were the greatest in women with the highest income, who had money savings, and in debt-free men and women.

Since the study of physical activity of working-age people has significant and broad practical implications for public health, it is necessary to seek new and effective remedial programs regarding hypokinesia. The results of the study show that individuals who are prone to hypokinesia include people with low income, with no money savings, and with debt. Actions aimed at improving the level of physical activity should be initiated by these individuals themselves as well as by socio-economic entities (companies, associations, and foundations) and institutional bodies. Examples of such actions may include developing, financing, and implementing programs aimed at increasing physical activity levels; tax exemptions and advantages, e.g., lower taxes on sport and recreational goods and services; public awareness campaigns promoting physical activity; or preferential health insurance terms for physically active individuals. A high level of physical activity, and in consequence, better health status and quality of life can in turn greatly contribute to higher work efficacy of working-age individuals as well as to better economic output of business companies and national economies.

Abbreviations

- IPAQ-SF:

International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form

- S-ESQ:

Socio-Economic Status of Working Age People Questionnaire

- EEPA:

Energy expenditure of physical activity

- PAL:

Physical activity level.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethical Approval

The research project has been given a positive opinion by the Commission of Bioethics of the University of Physical Education in Wroclaw.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Bruyere O. Importance of physical activity in primary, secondary and tertiary prevention of osteoporosis. Osteoporosis International. 2016;27:p. 559. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt S. C. E., Tittlbach S., Bös K., Woll A. Different Types of Physical Activity and Fitness and Health in Adults: An 18-Year Longitudinal Study. BioMed Research International. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/1785217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buman M. P., Hu F., Newman E., Smeaton A. F., Epstein D. R. Behavioral Periodicity Detection from 24 h Wrist Accelerometry and Associations with Cardiometabolic Risk and Health-Related Quality of Life. BioMed Research International. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/4856506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williamson W., Boardman H., Lewandowski A. J., Leeson P. Time to rethink physical activity advice and blood pressure: A role for occupation-based interventions? European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2016;23(10):1051–1053. doi: 10.1177/2047487316645008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rozek-Piechura K., Ignasiak Z., Sławińska T., Piechura J., Ignasiak T. Respiratory function, physical activity and body composition in adult rural population. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine. 2014;21(2):369–374. doi: 10.5604/1232-1966.1108607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mynarski W., Psurek A., Borek Z., Rozpara M., Grabara M., Strojek K. Declared and real physical activity in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus as assessed by the International Physical Activity Questionnaire and Caltrac accelerometer monitor: a potential tool for physical activity assessment in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2012;98(1):46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt T., Jonat W., Wesch D., et al. Influence of physical activity on the immune system in breast cancer patients during chemotherapy. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 2018;144(3):579–586. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2573-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danilowicz-Szymanowicz L., Figura-Chmielewska M., Ratkowski W., Raczak G. Effect of various forms of physical training on the autonomic nervous system activity in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Kardiologia Polska. 2013;71(6):558–565. doi: 10.5603/kp.2013.0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dziubek W., Kowalska J., Kusztal M., et al. The Level of Anxiety and Depression in Dialysis Patients Undertaking Regular Physical Exercise Training - A Preliminary Study. Kidney and Blood Pressure Research. 2016;41(1):86–98. doi: 10.1159/000368548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flöel A., Ruscheweyh R., Krüger K., et al. Physical activity and memory functions: are neurotrophins and cerebral gray matter volume the missing link? NeuroImage. 2010;49(3):2756–2763. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pavey T. G., Burton N. W., Brown W. J. Prospective relationships between physical activity and optimism in young and mid-aged women. Journal of Physical Activity & Health. 2015;12(7):915–923. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2014-0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heiestad H., Rustaden A. M., Bø K., Haakstad L. A. H. Effect of Regular Resistance Training on Motivation, Self-Perceived Health, and Quality of Life in Previously Inactive Overweight Women: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. BioMed Research International. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/3815976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Limm H., Heinmüller M., Gündel H., et al. Effects of a health promotion program based on a train-the-trainer approach on quality of life and mental health of long-term unemployed persons. BioMed Research International. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/719327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puciato D., Borysiuk Z., Rozpara M. Quality of life and physical activity in an older working-age population. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2017;12:1627–1634. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S144045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puciato D., Rozpara M., Borysiuk Z. Physical activity as a determinant of quality of life in working-age people in Wrocław, Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018;15(4) doi: 10.3390/ijerph15040623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arokoski J. P. A., Juntunen M., Luikku J. Use of health-care services, work absenteeism, leisure-time physical activity, musculoskeletal symptoms and physical performance after vocationally oriented medical rehabilitation - Description of the courses and a one-and-a-half-year follow-up study with farmers, loggers, police officers and hairdressers. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 2002;25(2):119–131. doi: 10.1097/00004356-200206000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rychetnik L., McCaffery K., Morton R., Irwig L. Psychosocial aspects of post-treatment follow-up for stage I/II melanoma: a systematic review of the literature. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22(4):721–736. doi: 10.1002/pon.3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sallis J. F., Cervero R. B., Ascher W., Henderson K. A., Kraft M. K., Kerr J. An ecological approach to creating active living communities. Annual Review of Public Health. 2006;27(1):297–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung S., Domino M. E., Stearns S. C., Popkin B. M. Retirement and physical activity: analyses by occupation and wealth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;36(5):422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim I.-G., So W.-Y. The relationship between household income and physical activity in Korea. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2014;26(12):1887–1889. doi: 10.1589/jpts.26.1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biernat E. Factors increasing the risk of inactivity among administrative, technical, and manual workers in Warszawa public institutions. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health. 2015;28(2):283–294. doi: 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.00194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcez A. D. S., Canuto R., Paniz V. M. V., et al. Association between work shift and the practice of physical activity among workers of a poultry processing plant in southern Brazil. Nutrición Hospitalaria. 2015;31(5):2174–2181. doi: 10.3305/nh.2015.31.5.8628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Attard S. M., Howard A.-G., Herring A. H., et al. Differential associations of urbanicity and income with physical activity in adults in urbanizing China: Findings from the population-based China Health and Nutrition Survey 1991-2009. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2015;12(1) doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0321-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaewthummanukul T., Brown K. C. Determinants of employee participation in physical activity: critical review of the literature. AAOHN Journal. 2006;54(6):249–261. doi: 10.1177/216507990605400602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Stralen M. M., de Vries H., Mudde A. N., Bolman C., Lechner L. Determinants of initiation and maintenance of physical activity among older adults: A literature review. Health Psychology Review. 2009;3(2):147–207. doi: 10.1080/17437190903229462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sallis J. F., Bull F., Guthold R., et al. Progress in physical activity over the Olympic quadrennium. The Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1325–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30581-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biernat E., Stupnicki R., Gajewski A. International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) – Polish version. Physical Education and Sport. 2007;51(1):47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nawrocka A., Garbaciak W., Cholewa J., Mynarski W. The relationship between meeting of recommendations on physical activity for health and perceived work ability among white-collar workers. European Journal of Sport Science. 2018;18(3):415–422. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2018.1424257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwaśniewska M., Pikala M., Bielecki W., et al. Ten-year changes in the prevalence and socio-demographic determinants of physical activity among Polish adults aged 20 to 74 years. Results of the National Multicenter Health Surveys WOBASZ (2003-2005) and WOBASZ II (2013-2014) PLoS ONE. 2016;11(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Puciato D., Rozpara M., Mynarski W., Łoś A., Królikowska B. Physical activity of adult residents of Katowice and selected determinants of their occupational status and socio-economic characteristics. Medycyna Pracy. 2013;64(5):649–657. doi: 10.13075/mp.5893.2013.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi B., Schnall P. L., Yang H., et al. Psychosocial working conditions and active leisure-time physical activity in middle-aged US workers. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health. 2010;23(3):239–253. doi: 10.2478/v10001-010-0029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kari J. T., Pehkonen J., Hirvensalo M., et al. Income and physical activity among adults: Evidence from self-reported and pedometer-based physical activity measurements. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cavagnoli D. The labour supply curve: A pluralist approach to investigate its measurements. Economic and Labour Relations Review. 2015;23(3):71–88. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bienkunska A., Piasecki T., Bieńkuńska A. Quality of Life in Poland in 2015. Results of The Social Cohesion Survey. Warsaw, Poland: GUS; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jurakic D., Golubić A., Pedisic Z., Pori M. Patterns and correlates of physical activity among middle-aged employees: A population-based, cross-sectional study. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health. 2014;27(3):487–497. doi: 10.2478/s13382-014-0282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piko B. F., Keresztes N. Sociodemographic and socioeconomic variations in leisure time physical activity in a sample of Hungarian youth. International Journal of Public Health. 2008;53(6):306–310. doi: 10.1007/s00038-008-7119-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stamm H., Lamprecht M. Structural and cultural factors influencing physical activity in Switzerland. Journal of Public Health. 2005;13(4):203–211. doi: 10.1007/s10389-005-0117-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Czapinski J., Panek T., Czapiński J. Social Diagnosis, 2015. Objective and Subjective Quality of Life in Poland. Quarterly of University of Finance and Management in Warsaw. 2015;9(4):56–59. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guszkowska M., Sionek S. Changes in mood states and selected personality traits in women participating in a 12-week exercise program. Human Movement Science. 2009;10(2):163–169. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maison D. Polish People in the World of Finance. Warsaw, Poland: PWN; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Puciato D. Leisure as determinant of life quality exemplified by empirical research. Studies and Works of the College of Management and Finance. 2009;95:97–109. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krzepota J., Biernat E., Florkiewicz B. The relationship between levels of physical activity and quality of life among students of the university of the third age. Central European Journal of Public Health. 2015;23(4):335–339. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a4136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pucci G., Reis R. S., Rech C. R., Hallal P. C. Quality of life and physical activity among adults: Population-based study in Brazilian adults. Quality of Life Research. 2012;21(9):1537–1543. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bielicki T., Szklarska A., Koziel S., Welon Z., Kozieł S. Systemic transformation in Poland in the light of anthropological studies of 19-year-old men. Department of Anthropology of the Polish Academy of Sciences. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Puciato D., Mynarski W., Rozpara M., Borysiuk Z., Szyguła R. Motor development of children and adolescents aged 8-16 years in view of their somatic build and objective quality of life of their families. Journal of Human Kinetics. 2011;28(1):45–53. doi: 10.2478/v10078-011-0021-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slawinska T., Sławińska T. Environmental conditions in the development of motor skills of rural children. Wrocław, Poland: University School of Physical Education; 2000. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.