The prevalence of type 2 diabetes is increasing rapidly, and diabetes is a powerful risk factor for kidney failure as well as death, cardiovascular disease, and many other adverse outcomes. Although much has been learned about the effects of strategies, such as lipid lowering, BP lowering, and glycemic control, on the risk of death and cardiovascular events, far less is known about the effects of these strategies and others on the risk of kidney failure.

ESKD is the outcome of greatest interest when assessing the effect of interventions on the kidney, but these clinical events are rare, because they take a long time to develop in progressive kidney diseases. This is particularly true for people with normal kidney function or early kidney disease, and therefore, most kidney outcome trials focus on people with significant established kidney disease. Feasibility can be challenging due to the long study duration and large sample size required to accrue adequate numbers of events to achieve adequate study power for realistic effect sizes. Enthusiasm for important clinical trials among funders, clinicians, and patients can also be affected.

As a result, composite outcomes including surrogate markers, such as doubling of serum creatinine or (more recently) 40% reductions in eGFR, have been accepted as appropriate outcomes that define the effects of interventions on long-term kidney risk. Most recently, there has been great interest in the use of attenuation of eGFR decline as well as reductions in albuminuria as outcomes for clinical trials (1). However, such surrogate end points can be affected by multiple confounders that may reduce their reliability. For example, 40% reductions in eGFR have been proposed to be less suitable in composite kidney outcomes than doubling in serum creatinine for interventions where a large acute change in eGFR occurs, because the difference in baseline levels may make it easier to achieve this threshold. Similarly, previous studies have identified that single measures of doubling in creatinine may produce directionally different results than sustained changes of this magnitude (2,3), because single measures may reflect acute changes in kidney function rather than progressive kidney disease. It is, therefore, always important to assess how well the creatinine-based outcomes align with ESKD when interpreting effects on composite kidney outcomes.

Data on kidney outcomes from the long-term follow-up of large randomized, controlled trials are extremely important, because they often constitute the majority of the available evidence regarding the effects of various interventions on outcomes that are slow to develop, such as kidney failure. The ACCORDION study is the extended follow-up of the ACCORD study—a double 2×2 factorial trial of adults with type 2 diabetes at high cardiovascular risk. Participants were randomly allocated to intensive versus standard glycemic control (target hemoglobin A1c <6% versus <7.5%), and then, each participant was randomized again to either different intensities of BP control (target systolic BP <120 versus <140 mm Hg) or fenofibrate versus placebo. It thus provides data on three different randomized comparisons. Although the original primary outcome was cardiovascular, the main end point for the analysis published in this issue of the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology is a composite kidney end point consisting of incident macroalbuminuria, doubling of creatinine, self-reported need for dialysis, or death from any cause (4). During the mean follow-up period of 7.7 years, there were 954 patients with doubling of creatinine, 351 self-reported dialysis events, and 1905 deaths documented (4).

Intensive glycemic control reduced the risk of the composite kidney end points, mainly driven by a reduction in incident macroalbuminuria, but randomization to intensive BP control or fenofibrates resulted in an increased risk of the composite kidney outcome, driven entirely by creatinine doubling in both the BP control (hazard ratio [HR], 1.52; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.25 to 1.85) and fibrate use (HR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.54 to 2.18) groups. Hence, the results raise the possibility that this might constitute evidence of harm on kidney outcomes from intensive BP control and fenofibrates in people with type 2 diabetes with high cardiovascular risk.

However, are these interpretations correct given that the increase in risk was only seen for the outcome of doubling of creatinine and was not seen for ESKD? Do other likely explanations exist, and can the reported data from this trial and others shed more light on the answers to these questions?

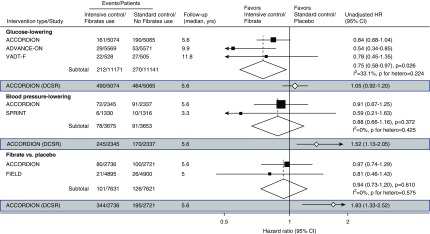

We have previously reported data from the ADVANCE-ON (5,6) trial suggesting that intensive glycemic control (hemoglobin A1c <6.5%) may have long-term kidney benefits (Figure 1). The ACCORDION study reported similar long-term composite kidney effects overall but found no separate benefit for either doubling of serum creatinine or incident dialysis. The HR for self-reported dialysis, however, was 0.84 in the ACCORDION study, with a 95% CI of 0.68 to 1.04. Pooling this result with those for ESKD from the other major recent trials assessing intensity of glucose control (the ADVANCE-ON [5] and the VADT-F [7]) leads to an overall HR of 0.75 (95% CI, 0.58 to 0.97; P=0.03), with no evidence of heterogeneity between the trials (P heterogeneity =0.22).

Figure 1.

Intensive blood glucose lowering reduces risk of end stage kidney disease when compared to standard glucose lowering in long term follow up studies. This is not observed in intensive blood pressure lowering and fibrate use. ACCORDION, Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study Follow-On Study; ADVANCE-ON, Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease Preterax and Diamicron MR Controlled Evaluation Post Trial Observational Study; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; DSCR, doubling of serum creatinine reading; FIELD, Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes Study; HR, hazard ratio; SPRINT, Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial; VADT-F, Veterans Affairs Diabetes Trial Follow-Up Study.

In contrast, the effects on doubling of serum creatinine (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.93 to 1.20) (Figure 1) are inconsistent with the effects on ESKD in the ACCORDION study alone or from the pooled trials, strongly suggesting that doubling of serum creatinine as measured in the ACCORDION study may not be a reliable surrogate for ESKD.

Why might this be? It likely relates to the reliance on a single measure of creatinine to define doubling of creatinine. In the ACCORD study, a small but statistically significant increase in creatinine was observed in the arm of intensive glucose lowering (8). As a result, participants randomized to this arm were on average “closer to the cliff” of doubling of serum creatinine and more likely to achieve the outcome as a result (for example, in situations where dehydration or intercurrent illness caused a transient increase in serum creatinine level).

The same issue is likely to explain the apparent harmful effect of both intensive BP lowering and fenofibrate therapy from the ACCORDION study. Both of these interventions are known to produce increases in serum creatinine level (through reduced glomerular pressure and competitive tubular resorption of creatinine, respectively), again increasing the risk of achieving doubling of serum creatinine levels. The reversible nature of fibrate-induced elevated serum creatinine has been clearly shown during the washout period of the FIELD study (9). In these cases, the effect on creatinine level is likely to be larger than that of intensive glycemic control, and this may explain the apparent large effect on doubling of creatinine.

Compared with the effects on ESKD from the ACCORDION study alone or other recent trials of similar BP targets (the SPRINT) (10) or fenofibrate use (the FIELD study), inconsistency is again seen between the effects on ESKD compared with those seen on doubling of serum creatinine (Figure 1). The increasing separation during the post-trial follow-up period might support a conclusion of potential harm; however, the 95% CIs around these curves are wide, and therefore, the specific estimates should be interpreted with caution. Given that doubling of creatinine is useful only as a surrogate for ESKD, this inconsistency suggests that effects on doubling of creatinine do not represent effects on the risk of progressive diabetes-associated kidney disease.

How might we deal with this issue going forward? In general, most kidney outcome trials require doubling of serum creatinine to be verified by repeating a blood test, typically at least 30 days later. The ACCORDION study was primarily a cardiovascular rather than a kidney trial; therefore, serum creatinine was measured infrequently, and doubling was not able to be confirmed by a repeat test as a result of the study design. This design limitation combined with the fact that all three interventions produce acute changes in eGFR also means that the effects on doubling of creatinine cannot be reliably used to define kidney effects of the various interventions.

As highlighted by the authors, self-reported dialysis was not confirmed for its chronicity, and it was not adjudicated. Furthermore, 73% (257 of 351 participants) of the participants self-reported to require dialysis had a final serum creatinine of <2.0 mg/dl, suggesting that most of the dialysis events are likely a result of AKI rather than progression of kidney function decline. Putting aside the accuracy of self-reported dialysis reflective of ESKD, the effects of intensive BP lowering and fibrates on dialysis remain uncertain but are each clearly different from the effects on doubling of creatinine. It is possible that the long-term effects on kidney function were also biased toward neutrality as a result of the self-reported nature of this outcome, although it might be expected that the effect could be less than that observed for doubling of creatinine.

How do we interpret these data? In our view, the findings observed for doubling of serum creatinine do not suggest kidney harm, but rather, they are more likely to reflect the limitations of the small number of creatinine measurements available. We believe that the data actually suggest possible benefit for ESKD with intensive glucose control and remain inconclusive for intensive BP control and fibrate use given the wide 95% CIs for the more reliable ESKD outcomes.

More broadly, these findings highlight the value of long-term follow-up of important clinical trials but also, the need to carefully define outcomes to ensure that the results are robust and reliable.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

M.G.W. is supported by Diabetes Australian Research Trust Millennium Grant and has received honorarium for scientific lectures from AstraZeneca, Amgen, Abbvie, Retrophin, and Baxter. H.J.L.H. received research funding support from Boehringer Ingelheim, Astrazeneca and Jansen, provides consultation for Astrazeneca, Abbvie, Astellas, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Gilead, Fresenius and Merck, having honoraria paid through employer University of Grongingen. V.P. serves on steering committees for trials supported by AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Retrophin and Tricida, has received fees for advisory boards or speaking at scientific meetings from AbbVie, Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Baxter, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Durect Corporation, Eli Lilly and Company, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Merck & Co., Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Pharmalink, Relypsa, Roche, Sanofi, Servier, and Vitae, and has a policy of having honoraria paid to his employer.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related article, “Long-Term Effects of Intensive Glycemic and Blood Pressure Control and Fenofibrate Use on Kidney Outcomes,” on pages 1693–1702.

References

- 1.Levey ASIL, Inker LA, Matsushita K, Greene T, Willis K, Lewis E, de Zeeuw D, Cheung AK, Coresh J: GFR decline as an end point for clinical trials in CKD: A scientific workshop sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation and the US Food and Drug Administration. Am J Kidney Dis 64: 821–835, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perkovic V, Heerspink HL, Chalmers J, Woodward M, Jun M, Li Q, et al.: Intensive glucose control improves kidney outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int 83: 517–523, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lambers Heerspink HJ, Perkovic V, de Zeeuw D: Is doubling of serum creatinine a valid clinical ‘hard’ endpoint in clinical nephrology trials? Nephron Clin Pract 119: c195–c199, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mottl AK, Buse JB, Ismail-Beigi F, Sigal RJ, Pedley CF, Papademetriou V, Simmons DL, Katz L, Mychaleckyj JC, Craven TE: Long-Term Effects of Intensive Glycemic and Blood Pressure Control and Fenofibrate Use on Kidney Outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1693–1702, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zoungas S, Chalmers J, Neal B, Billot L, Li Q, Hirakawa Y, Arima H, Monaghan H, Joshi R, Colagiuri S, Cooper ME, Glasziou P, Grobbee D, Hamet P, Harrap S, Heller S, Lisheng L, Mancia G, Marre M, Matthews DR, Mogensen CE, Perkovic V, Poulter N, Rodgers A, Williams B, MacMahon S, Patel A, Woodward M; ADVANCE-ON Collaborative Group : Follow-up of blood-pressure lowering and glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 371: 1392–1406, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong MG, Perkovic V, Chalmers J, Woodward M, Li Q, Cooper ME, Hamet P, Harrap S, Heller S, MacMahon S, Mancia G, Marre M, Matthews D, Neal B, Poulter N, Rodgers A, Williams B, Zoungas S; ADVANCE-ON Collaborative Group : Long-term benefits of intensive glucose control for preventing end-stage kidney disease: ADVANCE-ON. Diabetes Care 39: 694–700, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agrawal L, Azad N, Bahn GD, Ge L, Reaven PD, Hayward RA, Reda DJ, Emanuele NV; VADT Study Group : Long-term follow-up of intensive glycaemic control on renal outcomes in the Veterans Affairs Diabetes Trial (VADT). Diabetologia 61: 295–299, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, Goff DC Jr, Bigger JT, Buse JB, Cushman WC, Genuth S, Ismail-Beigi F, Grimm RH Jr, Probstfield JL, Simons-Morton DG, Friedewald WT; Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study Group : Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 358: 2545–2559, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis TM, Ting R, Best JD, Donoghoe MW, Drury PL, Sullivan DR, Jenkins AJ, O’Connell RL, Whiting MJ, Glasziou PP, Simes RJ, Kesäniemi YA, Gebski VJ, Scott RS, Keech AC; Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes Study investigators : Effects of fenofibrate on renal function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: The Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes (FIELD) study. Diabetologia 54: 280–290, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, Snyder JK, Sink KM, Rocco MV, Reboussin DM, Rahman M, Oparil S, Lewis CE, Kimmel PL, Johnson KC, Goff DC Jr, Fine LJ, Cutler JA, Cushman WC, Cheung AK, Ambrosius WT; SPRINT Research Group : A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med 373: 2103–2116, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]