Abstract

Background and objectives

Young adults receiving kidney replacement therapy (KRT) have impaired quality of life and may exhibit low medication adherence. We tested the hypothesis that wellbeing and medication adherence are associated with psychosocial factors.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We conducted a cross-sectional online survey for young adults on KRT. Additional clinical information was obtained from the UK Renal Registry. We compared outcomes by treatment modality using age- and sex-adjusted regression models, having applied survey weights to account for response bias by sex, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. We used multivariable linear regression to examine psychosocial associations with scores on the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale and the eight-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale.

Results

We recruited 976 young adults and 64% responded to the survey; 417 (71%) with transplants and 173 (29%) on dialysis. Wellbeing was positively associated with extraversion, openness, independence, and social support, and negatively associated with neuroticism, negative body image, stigma, psychologic morbidity, and dialysis. Higher medication adherence was associated with living with parents, conscientiousness, physician access satisfaction, patient activation, age, and male sex, and lower adherence was associated with comorbidity, dialysis, education, ethnicity, and psychologic morbidity.

Conclusions

Wellbeing and medication adherence were both associated with psychologic morbidity in young adults. Dialysis treatment is associated with poorer wellbeing and medication adherence.

Keywords: Depression, kidney transplantation, risk factors, dialysis, Medication Adherence, Cross-Sectional Studies, Patient Participation, Personal Satisfaction, Linear Models, Neuroticism, quality of life, Body Image, Extraversion (Psychology), renal dialysis, Patient Satisfaction, Surveys and Questionnaires, Social Support, Physician-Patient Relations, Comorbidity, Parents, Registries, Bias

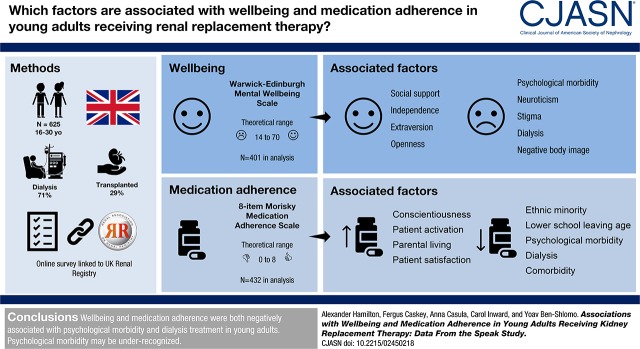

Visual Abstract

Introduction

ESKD affects the psychosocial health of young adults aged 16–30 years receiving kidney replacement therapy (KRT). A recent systematic review demonstrated lower quality of life (QoL) compared with the general population, particularly for patients on dialysis (1,2). We have previously reported that young adults on KRT have lower mental wellbeing and were twice as likely to have psychologic morbidity (defined by a score ≥4 on the 12-item General Health Questionnaire [GHQ-12]) compared with the age- and sex- matched general population, again more pronounced for patients on dialysis (2). However, the determinants of wellbeing have not been established in this population. A qualitative synthesis exploring young adults’ perspectives on living with kidney failure described overall themes of uncertainty and liminality, difference and the desire for normality, and thwarted or moderated dreams and ambitions. Key underlying themes included physical appearance/body image and social isolation (3).

The Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine’s position statement on young adults’ health and wellbeing says “Young adulthood is a unique and critical time of development where unmet health needs and health disparities are high. Purposeful prevention and intervention strategies should be developed, researched, and implemented during this time to improve health and wellbeing of young adults” (4). Needing KRT during young adulthood may have lasting consequences for later life. Medication nonadherence is common among kidney-transplanted adolescents, estimated at 43% in a systematic review (5). Adults with CKD and poor adherence are more likely to have progressive disease (6), graft loss, and death (7). Young adults are the highest risk age-group for kidney transplant loss (8,9). Medication nonadherence was estimated to account for 32% of kidney transplant loss in this group (5). Psychosocial wellbeing is a priority for patients and may provide insights into perceived poor engagement with health care services and medication adherence.

We have tested the hypothesis that wellbeing and medication adherence are associated with psychosocial factors using data from the Surveying Patients Experiencing Young Adult Kidney Failure (SPEAK) study, a national cross-sectional survey of participants aged 16–30 years old receiving KRT in the UK. We aimed to establish protective and risk factors to aid identification of high-risk subgroups and potential interventions.

Materials and Methods

We designed a cross-sectional online self-completion survey for participants aged 16–30 years old receiving KRT in the UK, after an initial pilot. The survey comprised questions (in English) from validated health surveys (reported elsewhere [2]) with comparable normative data. Additional scales and tools covering aspects of chronic disease were also included (described in Supplemental Table 1). The study was granted ethical approval by the Health Research Authority National Research Ethics Service Committee, reference 15/SW/0101.

Clinical Participants

The study inclusion criteria were (1) aged ≥16 years and <31 years and (2) receiving maintenance KRT. We chose a wide age range as there is no consensus definition of young adulthood. Participants were excluded if participation was expected to cause psychologic distress or they were unable to complete the questionnaire with assistance. Participants were identified and approached for participation by the hospital providing their KRT. All National Health Service trusts with an adult or pediatric kidney unit (n=74) took part in the study, yet two did not recruit any participants. Sites opened sequentially and recruited for 6 months, between 2015 and 2017. We aimed to recruit 1000 young adults and estimated a 50% response rate. Assuming equal group sizes, this provided 90% power to detect a standardized difference (z-score) of 0.29 (α=0.05) and a 10% proportion difference for an outcome with a 10%–50% prevalence.

Participants selected survey access by email, or via a computer at their kidney unit (where available). Participants could be supported in survey completion as required. If no survey response was received, Email reminders were sent at 7 days, and at 14 days the kidney unit checked survey receipt and provided another reminder. We requested screening logs from sites to assess reasons for study nonparticipation.

Survey Software

Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) hosted at the University of Bristol (10). REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies. It provided greater convenience to our participants than a paper survey by allowing a “save and return” option and through use of branching logic to deliver relevant questions on the basis of preceding filter responses, thereby reducing the burden of survey completion. Further, it avoided printing, postage, and data entry costs and potentially reduced the risk of introducing data entry errors.

Clinical Data from the UK Renal Registry

The UK Renal Registry (UKRR) collects data on all patients receiving KRT from UK adult and pediatric kidney units (11,12). It has been granted a section 251 exemption by the Health Research Authority, allowing the registration of identifiable patient information from kidney units without first asking individual patient consent. All participants were asked for consent to access their UKRR data regardless of survey response. We also accessed anonymized aggregate level data for study nonparticipants (those eligible for the SPEAK study as of December 2015, but who did not give consent), to enable comparison to the wider young adult population. This allowed examination and adjustment for response bias and description of clinical aspects for young adults receiving KRT. We classified primary kidney disease using a recent European coding system (13).

Survey Response

We weighted survey responses as the inverse of the sampling fraction for sex, ethnicity, and socioeconomic deprivation, to account for survey response bias and thus be representative of the wider young adult KRT population.

Statistical Analyses

We compared scale results by clinical characteristics (sex, treatment modality, pediatric/adult starting unit and treatment duration) using age- and sex-adjusted regression models, appropriate to the data and distribution. We followed scale author recommendation or published methods for handling missing data, using average or lowest score substitution. We developed theoretical frameworks to examine associations of selected outcomes. We used the Wilson and Cleary QoL model adapted by Ferrans et al. (14) (Supplemental Figure 1), because this includes additional dimensions to explain QoL better (15). We chose the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale as the outcome variable in this model over EuroQoL-5D-3L as it is less driven by physical aspects. For medication adherence, we used the eight-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8) and devised our own framework (Supplemental Figure 2), as we could find no precedent in the literature. In each framework we examined the explanatory variables (shaded variables in Supplemental Figures 1 and 2) in turn to establish whether they were associated in an age- and sex-adjusted regression model. We combined shortlisted variables in a multivariable linear (least squares) regression model, adjusting for confounders. We removed nonassociated explanatory variables from the final model, having checked that this did not affect the β coefficients of the remaining variables. We checked for assumptions of linearity between continuous variables and the outcome variable, evidence of heteroscedasticity, and that residuals were normally distributed with a mean of zero. We also tested for potential prespecified interactions in our theoretical frameworks. We used Stata v.14 for our analyses.

Results

Survey Response

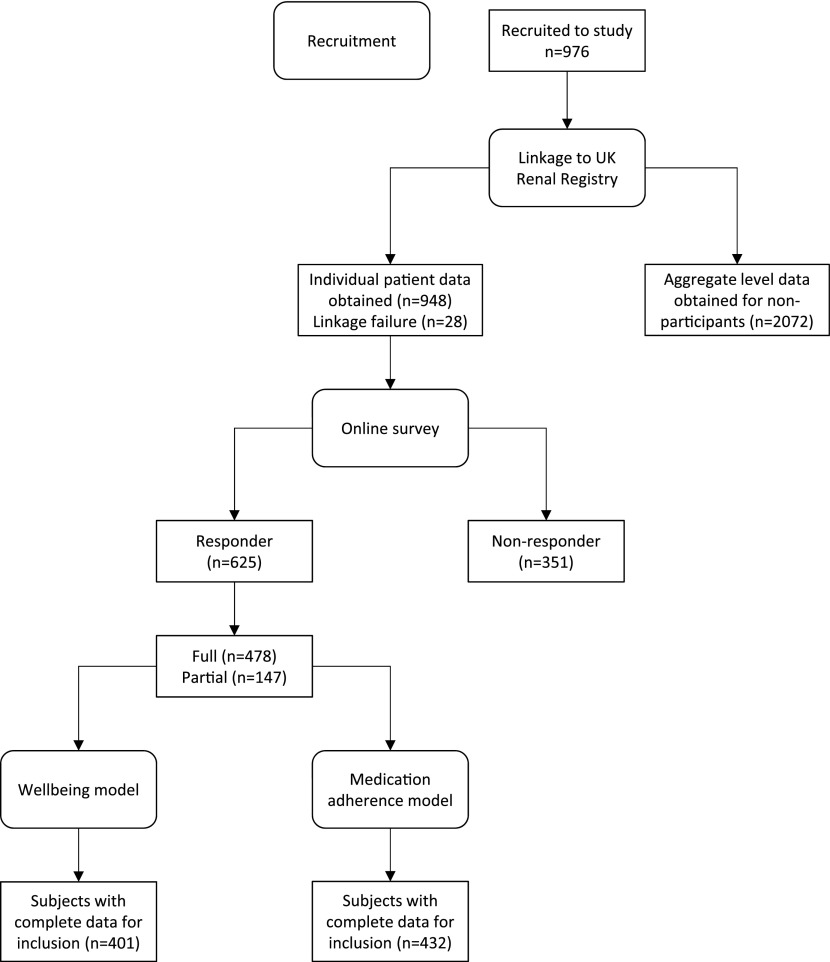

Figure 1 displays a study flowchart. Overall, 976 participants were recruited. The main reasons for study nonparticipation (data available from 48 sites) were (1) no response to the invitation letter (14%), (2) participation declined (9%), and (3) the participant could not be contacted (6%). The survey response rate was 64% (625 out of 976) and has been described previously (2). There were 2072 young adults known to the UKRR who did not participate, so our sample comprises 21% of the total eligible population. Characteristics of responders are shown in Table 1. Responders were statistically more likely to be women, white, and have higher socioeconomic status compared with both survey nonresponders and study nonparticipants. Compared with both survey nonresponders and study nonparticipants, survey responders were more likely to be managed in smaller centers that do not undertake kidney transplantation. Survey responders with transplants had a slightly lower eGFR (−3.2 ml/min per 1.73 m2; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], −5.9 to −0.5; P=0.02) than nonresponders and nonparticipants, although this is of uncertain significance. There were no other differences. The median time to complete the survey was 53 minutes (interquartile range [IQR], 40–71) and most (595 out of 625; 95%) selected survey access by email.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of survey responders

| Variable | Survey Responders, n=625 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Proportion, % | |||

| Men | 625 | 51 | ||

| Age, yr, median (IQR) | 625 | 25 (21–28) | ||

| Age group, yr, 16 to <21/21 to <26/26 to <31 | 625 | 21/30/48 | ||

| Country | 625 | |||

| England | 74 | |||

| Scotland | 6 | |||

| Wales | 10 | |||

| Northern Ireland | 10 | |||

| Ethnicity | 625 | |||

| White | 85 | |||

| Asian | 9 | |||

| Black | 4 | |||

| Other | 3 | |||

| Index of multiple deprivation quintile, 1/2/3/4/5a | 625 | 19/21/17/22/21 | ||

| Managed in adult center and aged <20 yr | 101 | 57 | ||

| Managed in transplant center | 625 | 55 | ||

| Nephrology unit size, small/medium/largeb | 625 | 18/46/35 | ||

| Managed in transition clinic centerc | 625 | 64 | ||

| UK Renal Registry linked | 609 | 97% | ||

| Duration since KRT start, yr, median (IQR)d | 609 | 6 (2–11) | ||

| Started in adult unit | 609 | 59 | ||

| Primary kidney diseasee | 572 | |||

| Glomerular diseases | 27 | |||

| Systemic diseases affecting the kidney | 7 | |||

| Familial/hereditary nephropathies | 11 | |||

| Tubulointerstitial diseases | 31 | |||

| Miscellaneous kidney disorders | 18 | |||

| Time to KRT start from first nephrology review, d, median (IQR) | 431 | 745 (40–1984) | ||

| Time to KRT start for those in pediatric services, d, median (IQR) | 396 | 667 (34–1923) | ||

| Time to KRT start for those in adult services, d, median (IQR) | 35 | 1048 (211–3441) | ||

| Late referral, time to KRT start <90 d/90 to <365 d/≥365 d | 431 | 21/9/41 | ||

| Timeline data complete | n=590 | 97% | ||

| Starting modality | 590 | |||

| Hemodialysis | 37 | |||

| Peritoneal dialysis | 39 | |||

| Transplant | 21 | |||

| Starting transplant type | 125 | |||

| Live donor | 46 | |||

| Deceased donor | 45 | |||

| Unknown | 9 | |||

| Current modality | 590 | |||

| Transplant | 71 | |||

| Hemodialysis | 24 | |||

| Peritoneal dialysis | 6 | |||

| Current transplant type | 417 | |||

| Live donor | 39 | |||

| Deceased donor | 52 | |||

| Unknown | 9 | |||

| Modality changes >90 d, 0/1/≥2 | 590 | 31/38/28 | ||

| Ever had a transplant | 590 | 82 | ||

| Ever had a failed transplant | 502 | 27 | ||

| Number of transplants, mean (SD) | 502 | 1 (1) | ||

| Biochemical variables | Transplant, n=417 | Dialysis, n=173 | ||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 414 | 59 (23) | — | — |

| CKD stage, 1/2/3a/3b/4/5 (proportion, %) | 414 | 10/36/26/17/7/2 | — | — |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 414 | 127 (18) | 169 | 107 (17) |

| Ferritin, µg/L, median (IQR) | 350 | 135 (54–308) | 168 | 351 (211–608) |

| Bicarbonate, mmol/L | 383 | 23 (3) | 158 | 24 (4) |

| Calcium, mmol/L | 413 | 2.40 (0.12) | 171 | 2.30 (0.22) |

| Phosphate mmol/L | 415 | 1.00 (0.26) | 171 | 1.82 (0.64) |

| Parathyroid hormone, pmol/L, median (IQR) | 326 | 8.1 (5.0–13.0) | 157 | 38.7 (18.5–86.1) |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 320 | 127 (14) | 140 | 138 (25) |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 305 | 77 (11) | 137 | 84 (18) |

| Weight, kg | 303 | 68 (19) | 137 | 71 (24) |

Participant interaction with the online survey that led to the generation of an identifiable survey record was counted as a response. Not all percentages may total 100 because of rounding. Nonparametric data are presented as median and IQR. IQR, interquartile range; KRT, kidney replacement therapy.

We used derived UK-wide indexes of multiple deprivation quintiles (1 indicates least deprived and 5 indicates most deprived) (34) using postcodes.

Defined by tertiles of patients on prevalent KRT in 2015; we defined small units as having <500 adult patients or <50 pediatric patients, medium units as having 500 to <1500 adult patients or 50 to <100 pediatric patients, and large units as having ≥1500 adult patients or ≥100 pediatric patients.

As of September 2015 (35), with additional data obtained directly from kidney units.

If KRT start date was missing, the first timeline entry date was substituted.

According to the 2012 European Renal Association–European Dialysis and Transplant Association coding system (13).

Cohort Characteristics

The cohort comprised 417 (71%) patients with transplants and 173 (29%) on dialysis, and has been previously described (2). Survey participants were 51% men and 74% white, with a median age of 25 years. The most common primary kidney disease group was tubulointerstitial diseases (31%) from structural causes, followed by glomerular diseases (27%). The median duration since KRT start was 6 years. The majority (59%) started KRT in adult services. Most were transplanted (71%), and the mean eGFR was 59 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (SD, 23). Few young adults were using peritoneal dialysis (6%, compared with 24% using hemodialysis). A fifth started KRT <90 days from first nephrology review. Around 80% had undergone transplantation, with 27% having experienced transplant failure.

QoL, Wellbeing, Psychologic Morbidity, Medication Adherence, and Other Scales

Average scale scores are shown in Table 2 (higher scores indicate better outcome unless stated below). The median EuroQoL-5D-3L tariff was 0.80 (IQR, 0.62–1.00; possible range, −0.59 to 1.00). From the GHQ-12, overall 43% had no evidence of mental health problems, 26% had below optimal mental health, and 31% had probable psychologic disturbance/mental ill health. The median Independence with Activities of Daily Living score was 26 (IQR, 21–27; possible range, 9–27). Medication adherence was low in 43%, medium in 34%, and high in 23%. The median Body Image Scale score was 9 (IQR, 3–18; possible range, 0–30; higher scores indicate worse body image). The median Social Impact Scale score was 40 (IQR, 28–53; possible range, 21–90; higher scores indicate greater stigma). The median Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support Scale score was 65 (IQR, 54–75; possible range, 12–84). On average, patient satisfaction was scored as 4 (possible range, 1–5) across seven domains. The mean wellbeing score was 47.4 (SD, 11.5; possible range, 14–70). There was good illness acceptance in 34%, moderate acceptance in 49%, and no acceptance in 17%. Patient activation was level 1 (may not yet believe that the patient role is important) in 26%, level 2 (lacks confidence and knowledge to take action) in 18%, level 3 (beginning to take action) in 36%, and level 4 (has difficulty maintaining behaviors over time) in 20%.

Table 2.

Psychologic health in UK young adults receiving kidney replacement therapy

| Scale | Possible Range | N | Weighted Average Score | Weighted Measure of Variability | Group | Weighted Proportion, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | |||||

| EuroQoL-5D-3L tariff | −0.59–1.00 | 538 | 0.80 | 0.62–1.00 | ||

| General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) | 0–12 | 527 | 1 | 0–5 | Score 0/1–3/≥4 | 43/26/31 |

| Independence with Activities of Daily Living Scale | 9–27 | 545 | 26 | 21–27 | ||

| Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8)a | 0–8 | 543 | 6.5 | 4.75–7 | Low/medium/high | 43/34/23 |

| Body Image Scale | 0–30 | 520 | 9 | 3–18 | ||

| Social Impact Scale | 21–96 | 467 | 40 | 28–53 | ||

| Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support | 12–84 | 499 | 65 | 54–75 | ||

| Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-18) | ||||||

| General satisfaction | 1–5 | 500 | 4 | 3–4.5 | ||

| Technical quality | 1–5 | 499 | 4 | 3.5–4.5 | ||

| Interpersonal manner | 1–5 | 502 | 4 | 3.5–5 | ||

| Communication | 1–5 | 503 | 4 | 3.5–4.5 | ||

| Financial aspects | 1–5 | 499 | 4.5 | 3.5–5 | ||

| Time spent with doctor | 1–5 | 501 | 4 | 3–4 | ||

| Accessibility and convenience | 1–5 | 500 | 3.75 | 3.25–4.25 | ||

| Mean | SD | |||||

| Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale | 14–70 | 535 | 47.4 | 11.5 | ||

| Acceptance of Illness Scale | 8–40 | 485 | 26.1 | 7.4 | None/moderate/good | 17/49/34 |

| Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scale | ||||||

| Internal | 6–36 | 486 | 22.2 | 5.3 | ||

| Chance | 6–36 | 483 | 20.3 | 5.1 | ||

| Powerful others | 6–36 | 484 | 21.7 | 5.0 | ||

| Big Five Inventory (BFI-44) | ||||||

| Extraversion | 1–5 | 482 | 3.02 | 0.77 | ||

| Agreeableness | 1–5 | 482 | 3.76 | 0.58 | ||

| Conscientiousness | 1–5 | 479 | 3.43 | 0.66 | ||

| Neuroticism | 1–5 | 481 | 3.12 | 0.85 | ||

| Openness | 1–5 | 480 | 3.40 | 0.56 | ||

| Patient Activation Measure (PAM-13) | 0–100 | 461 | 59.3 | 15.1 | Level 1/2/3/4 | 26/18/36/20 |

| Quality of Life Scale | 16–112 | 465 | 79.8 | 17.8 |

Total n=625. Data weighted by sex, ethnicity, and index of multiple deprivation to be representative of prevalent UK young adults receiving KRT. Nonparametric data are presented as median and IQR. IQR, interquartile range; KRT, kidney replacement therapy.

Use of the MMAS-8 is protected by United States copyright laws. Permission for use is required. A license agreement is available from Morisky Research LLC.

Scale Results by Treatment Modality

Compared with transplant, young adults on dialysis had lower QoL (odds ratio [OR] for EuroQoL-5D-3L “No problems,” 0.31; 95% CI, 0.19 to 0.51; P<0.001), wellbeing (β=−5.61; 95% CI, −7.92 to −3.29; P<0.001), disease acceptance (β=−5.35; 95% CI, −6.78 to −3.91; P<0.001), and patient activation (β=−4.52; 95% CI, −6.94 to −2.10; P<0.001) (Table 3). They were more likely to have worse psychologic health (GHQ-12 group OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.2 to 3.0; P=0.005), body image (above median score OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.1 to 2.8; P=0.02), independence (below median score OR, 0.3; 95% CI, 0.2 to 0.5; P<0.001), and stigma (above median score OR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.6 to 3.9; P<0.001). Generally, young adults on dialysis were less satisfied, apart from “Interpersonal Manner” and “Financial Aspects” domains and these associations were unlikely to be due to chance. There was no difference in social support by treatment modality (OR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.61 to 1.34; P=0.6). Compared with transplant, young adults on dialysis had lower medication adherence (MMAS-8 group OR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.2 to 0.6; P<0.001). Supplemental Table 2 details further comparisons by sex, pediatric or adult starting unit, and treatment duration. There were few differences by start or duration, although young adults who started KRT in childhood had higher disease acceptance and a slightly higher patient activation score.

Table 3.

Regression analyses of psychologic health scales in UK young adults receiving kidney replacement therapy by current treatment

| Scale | By Modality (Dialysis versus Transplant), Adjusted for Age and Sex | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β/OR | 95% CI | P Value | ||

| Lower | Upper | |||

| EuroQoL-5D-3L tariffa | 0.31 | 0.19 | 0.51 | <0.001 |

| General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12)b | 1.90 | 1.22 | 2.96 | 0.005 |

| Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8)c | 0.40 | 0.25 | 0.64 | <0.001 |

| Independence with Activities of Daily Living Scale | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.46 | <0.001 |

| Body Image Scale | 1.74 | 1.09 | 2.76 | 0.02 |

| Social Impact Scale | 2.46 | 1.57 | 3.86 | <0.001 |

| Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support | 0.90 | 0.61 | 1.34 | 0.61 |

| Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-18) | ||||

| General satisfaction | 0.55 | 0.38 | 0.80 | 0.002 |

| Technical quality | 0.53 | 0.33 | 0.85 | 0.01 |

| Interpersonal manner | 0.71 | 0.51 | 1.01 | 0.06 |

| Communication | 0.58 | 0.40 | 0.84 | 0.004 |

| Financial aspects | 0.88 | 0.54 | 1.41 | 0.59 |

| Time spent with doctor | 0.39 | 0.22 | 0.68 | 0.001 |

| Accessibility and convenience | 0.52 | 0.37 | 0.75 | 0.001 |

| Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS) | −5.61 | −7.92 | −3.29 | <0.001 |

| Acceptance of Illness Scale | −5.35 | −6.78 | −3.91 | <0.001 |

| Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scale | ||||

| Internal | −1.16 | −2.24 | −0.08 | 0.04 |

| Chance | 0.05 | −1.04 | 1.13 | 0.93 |

| Powerful others | −0.65 | −1.81 | 0.51 | 0.29 |

| Big Five Inventory (BFI-44) | ||||

| Extraversion | −0.09 | −0.27 | 0.08 | 0.29 |

| Agreeableness | −0.11 | −0.21 | −0.001 | 0.05 |

| Conscientiousness | −0.20 | −0.34 | −0.05 | 0.01 |

| Neuroticism | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.37 | 0.01 |

| Openness | −0.01 | −0.11 | 0.10 | 0.90 |

| Patient Activation Measure (PAM-13) | −4.52 | −6.94 | −2.10 | <0.001 |

| Quality of Life Scale | −6.79 | −10.7 | −2.85 | 0.001 |

Data weighted by sex, ethnicity, and index of multiple deprivation to be representative of prevalent UK young adults receiving KRT. Nonparametric scale scores are grouped into whether >50th centile or not for logistic regression analyses unless otherwise stated. For parametric data, β coefficients represent the change in scale units (described in Table 2). OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; KRT, kidney replacement therapy.

Grouped in logistic regression analyses as “No problems”/“Some problems” corresponding to a tariff of 1 or <1.

Grouped in ordered regression analyses as “No evidence of probable mental ill health”/“Less than optimal mental health”/“Probable psychologic disturbance or mental ill health” corresponding to a scale score of 0, 1–3, or 4+.

Use of the MMAS-8 is protected by United States copyright laws. Permission for use is required. A license agreement is available from Morisky Research LLC. The MMAS-8 was grouped in ordered regression analyses as low/medium/high adherence corresponding to a scale score of <6, 6–7, or 8.

Factors associated with Wellbeing

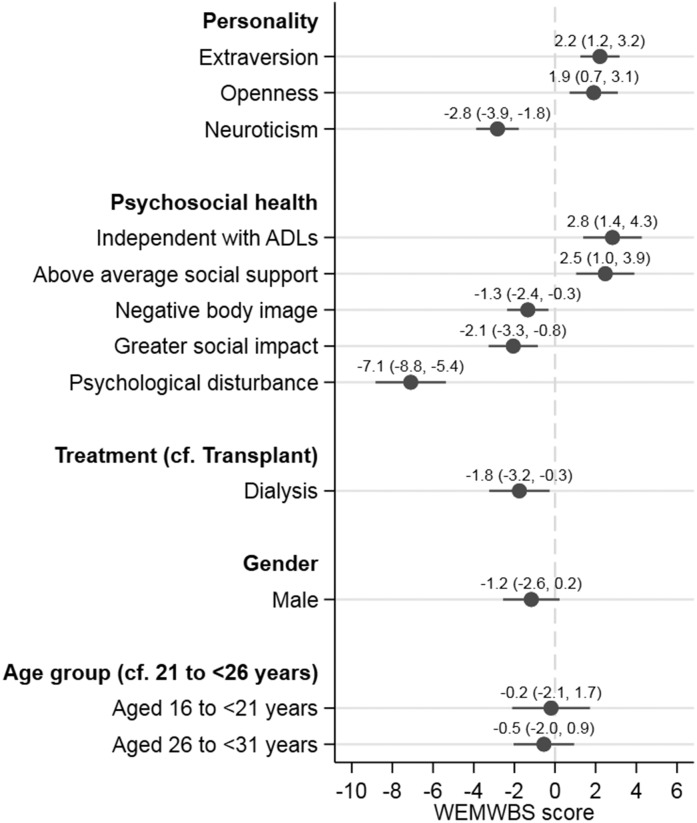

The greatest association with lower wellbeing was psychologic morbidity (β=−7.1; 95% CI, −8.8 to −5.4; P<0.001) (Figure 2). Dialysis was also associated with lower wellbeing (β=−1.8; 95% CI, −3.2 to −0.3; P=0.02), although we observed an attenuated effect from the crude differences (Table 3) after adjustment in the multivariable model. Other negative associations included neuroticism (β=−2.8; 95% CI, −3.9 to −1.8; P<0.001), negative body image (β=−1.3; 95% CI, −2.4 to −0.3; P=0.01), and stigma (β=−2.1; 95% CI, −3.3 to −0.8; P=0.001). In contrast, positive associations with wellbeing were extraversion (β=2.2; 95% CI, 1.2 to 3.2; P<0.001) or openness (β=1.9; 95% CI, 0.7 to 3.1; P=0.002), independence with activities of daily living (β=2.8; 95% CI, 1.4 to 4.3; P<0.001), and higher social support (β=2.5; 95% CI, 1.0 to 3.9; P=0.001). Sex (β=−1.2; 95% CI, −2.6 to 0.2; P=0.1) and age group (P=0.6 for trend) did not affect wellbeing when adjusted for other factors. Our final wellbeing model had an adjusted R2 value of 68%, suggesting reasonable model fit. We found no evidence for interaction between GHQ-12 score and neuroticism, dialysis treatment, or Independence with Activities of Daily Living score; social support and extraversion or neuroticism; and dialysis treatment and employment status. Univariable coefficients are shown in Supplemental Table 3.

Figure 2.

Wellbeing was positively associated with extraversion, openness, independence, and social support, and negatively associated with neuroticism, negative body image, stigma, psychologic morbidity, and dialysis. n=401. Higher scores indicate greater mental wellbeing. The β coefficient of the model intercept was 57.4 (95% CI, 50.9 to 63.8; P<0.001). The model adjusted R2 was 0.68. For personality scales, the coefficient is for each single-unit scale change. “Negative body image” is for each ten-unit change on the Body Image Scale. “Greater social impact” is for each 20-unit change on the Social Impact Scale. Psychologic disturbance was defined by a GHQ-12 score of ≥4. When the GHQ-12 was omitted from the model the adjusted R2 was 0.62, indicating it does not explain a large proportion of the variance. ADLs, activities of daily living; WEMWBS, Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale.

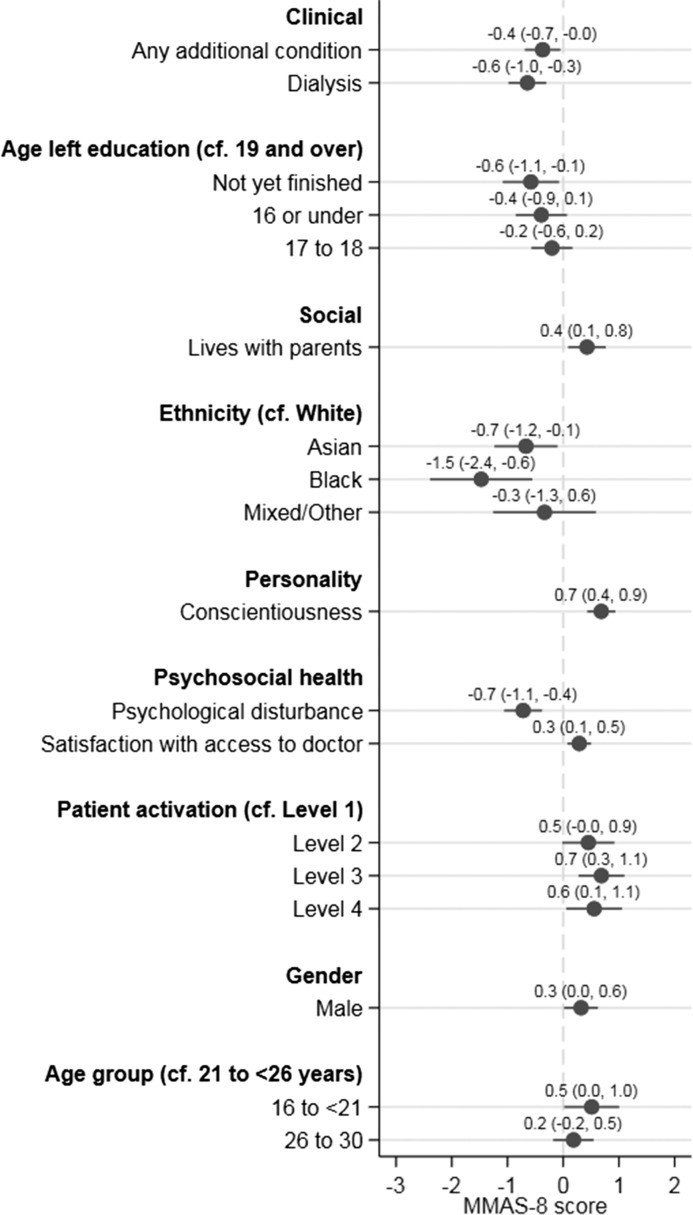

Factors associated with Medication Adherence

Factors lowering medication adherence (Figure 3) comprised having an additional condition (β=−0.4; 95% CI, −0.7 to −0.1; P=0.02), a lower age of finishing full-time education (P=0.01 for trend), black and Asian ethnicities (β=−1.5; 95% CI, −2.4 to −0.6; P=0.002 and β=−0.7; 95% CI, −1.2 to −0.1; P=0.02, respectively), and psychologic morbidity (β=−0.7; 95% CI, −1.1 to −0.4; P<0.001). Dialysis was also negatively associated, and the association was lessened from the crude difference (β=−1.1; 95% CI, −1.5 to −0.8; P<0.001) after adjustment in the multivariable model (β=−0.6; 95% CI, −0.7 to −0.1; P<0.001).

Figure 3.

Higher medication adherence was associated with living with parents, conscientiousness, physician access satisfaction, patient activation, age, and male sex, and lower adherence was associated with comorbidity, dialysis, education, ethnicity, and psychologic morbidity. Higher scores indicate a greater degree of medication adherence. The β coefficient of the model intercept was 3.13 (95% CI, 1.78 to 4.48; P<0.001). The model adjusted R2 was 0.33. For personality and patient satisfaction scales, the coefficient is for each single-unit scale change. Psychologic disturbance was defined by a GHQ-12 score of ≥4. Use of the MMAS-8 is protected by United States copyright laws. Permission for use is required. A license agreement is available from Morisky Research LLC.

In contrast, factors associated with a higher medication adherence score were living with parents (β=0.4; 95% CI, 0.1 to 0.8; P=0.01), conscientiousness (β=0.7; 95% CI, 0.4 to 0.9; P<0.001), greater physician access satisfaction (β=0.3; 95% CI, 0.1 to 0.5; P=0.008), higher patient activation (P=0.008 for trend), male sex (β=0.3; 95% CI, 0.02 to 0.6; P=0.04), and being aged 16 to <21 years (β=0.5; 95% CI, 0.02 to 1.0; P=0.04). There was no change in the dialysis coefficient after adjustment for psychologic morbidity and/or patient activation (data not shown), suggesting these do not mediate the dialysis treatment effect.

There was a significant interaction (likelihood ratio test P=0.002 between full model and model fitting the interaction term) between ethnicity and dialysis treatment. The stratum-specific exposure effects of ethnicity and dialysis (compared with white race and dialysis) are as follows: Asian, dialysis: β=−1.19 (95% CI, −2.21 to −0.16; P=0.02); black, dialysis: β=−2.82 (95% CI, −4.02 to −1.62; P<0.001); mixed/other, dialysis: β=0.60 (95% CI, −1.20 to 2.40; P=0.5); white, transplant: β=0.50 (95% CI, 0.14 to 0.86; P=0.006); Asian, transplant: β=0.02 (95% CI, −0.69 to 0.73; P=0.96); black, transplant: β=0.83 (95% CI, −0.58 to 2.24; P=0.2); mixed/other, transplant: β=−0.12 (95% CI, −1.20 to 0.95; P=0.8). There was no interaction between living with parents and age at finishing full-time education or dialysis treatment; patient activation and conscientiousness or age at finishing full-time education; or dialysis treatment and GHQ-12 score. Univariable coefficients are shown in Supplemental Table 4.

Discussion

In young adults receiving KRT, worse outcomes for mental wellbeing and medication adherence were both associated with psychologic morbidity and dialysis treatment, whereas social support and living with parents were associated with better outcomes. These findings are important because psychologic disturbances may be treatable and should prompt caregivers to evaluate psychologic state carefully as well as barriers to transplantation. Further, there is large potential for health and health care improvements for young adults because of their longer life expectancy compared with older adults receiving KRT. Psychologic problems may be under-recognized; using the GHQ-12 as a screening tool, 31% of young adults on KRT had psychologic morbidity, but only 17% reported their condition affected their mental health (2). Therefore, opportunities to identify and improve mental health may be being missed. Although some associated variables may be nonmodifiable, their potential measurement in clinical practice might help identify those at higher risk of poor outcomes for close monitoring, greater psychosocial support, or targeted intervention. Compared with transplant, dialysis was associated with reduced QoL, wellbeing, disease acceptance, independence with activities of daily living, medication adherence, patient activation, and patient satisfaction, and a higher likelihood of psychologic disturbance, worse body image, and stigma.

Our data furthers previous systematic evidence of lower QoL in young adults on dialysis compared with transplant (1), even after adjusting for a wide range of psychosocial variables, by identifying associated factors in a robust dataset. Our wellbeing model variables explained a high proportion of the variance. Young adults on dialysis have an increased mortality risk (16); our findings show dialysis is associated with lowered psychologic as well as physical health. Our estimate of young adult low medication adherence mirrored that of adolescent nonadherence in a systematic review, at 43% (5). Although no clinical or psychosocial factors were associated with medication adherence in a previous study of transplanted young adults (17), we report many associations that are unlikely to be due to chance. Depression is known to lower adherence and be a major determinant of QoL in older adults on KRT (18–20). Our study provides evidence that this is also true for young adults. Beliefs about medication were associated with adherence in a previous study of adults with kidney transplants (21); a similar effect may be seen in our data through conscientiousness and patient activation.

Although the proportion with psychologic morbidity is similar to the overall meta-analytical prevalence of depression in older adults with CKD (34.0%; 95% CI, 31.9 to 36.2) (22), psychosocial health during young adulthood may have lasting life-course influences on developing adult identity and other outcomes (23). We found similar associations of extraversion, neuroticism and openness with mental wellbeing in young adults on KRT as previous studies of older adults with CKD (24) and kidney transplants (20). We have previously shown that compared with the general population, young adults are three times more likely to live in the family home (2) and although diminished independence could be considered undesirable, it had a positive association in our medication adherence model.

Potential mechanisms underlying the psychosocial determinants of medication adherence include individual and environmental factors. Our data showed a lower age of finishing full-time education was associated with less adherence. This could be due to reduced health literacy. In a retrospective cohort study, half of young adults with CKD had limited health literacy skills, but health literacy was not associated with clinical outcomes (25). We found patient satisfaction was associated with higher adherence, suggesting that coproducing services with young adults could be valuable in engaging patients and improving health care utilization. Increasing patient activation was associated with higher adherence. In a longitudinal study, more activated patients were less likely to develop diabetes and patients with diabetes were more likely to have better diabetic clinical indicators (26). Interventions that improve activation could have wider benefits than improving adherence alone.

A range of psychosocial interventions have promise in improving outcomes, personality traits, and adherence in chronic conditions, but evidence is lacking in KRT populations. Self-affirmation has been shown to improve phosphate and fluid management in adult patients on hemodialysis (27,28). A systematic review of personality traits changes through intervention found marked differences over 24 weeks in personality trait measures (29). Supportive evidence for interventions can also be found with other chronic conditions affecting young adults. There was modest evidence from a systematic review that psychologic interventions improved glycemic control in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes but not in adults (30). This suggests that we cannot assume interventions will be effective in young adults and require formal evaluations. Similarly, there is evidence from a systematic review that education, electronic trackers/reminders, and simplified regimens result in better medication adherence among asthmatic patients than control interventions (31). Interventions can also positively influence social outcomes. Group cognitive–behavioral therapy has been shown to lower GHQ scores in the long-term unemployed, and compared with control programs, increases the likelihood of finding full-time employment after 4 months (32). Cognitive–behavioral therapy could be a promising intervention in the improvement of wellbeing and medication adherence in young adults on KRT.

Our study is strengthened by providing a comprehensive evaluation of aspects of psychologic health in young adults on KRT, through utilization of established and widely used scales. It is the largest cohort of young adult patients receiving transplant and dialysis, with variation in modality and age at presentation. The study was multicenter, and our survey had a similar response rate to a large previous study of young adults with kidney transplants (33). By linking our survey data to a national kidney registry, we enhanced our self-reported data with clinical data. We reduced survey response bias by weighting our data, thereby improving generalizability to the wider young adult population with KRT.

Our study has several important limitations that need to be considered. The design is cross-sectional, meaning the effect of treatment changes on the outcomes cannot be tracked and directionality between any of the variables cannot be established. For example, dialysis decisions may be influenced by poor social support/treatment engagement, comorbidities, and prognosis rather than being the cause of the observed negative associations. Longitudinal studies are needed to help determine the sequencing of events. Some kidney units were able to provide tablet devices to facilitate survey access (especially during dialysis) but this was not consistent. Self-reported outcomes may be prone to bias. We had missing data both from nonresponders and nonparticipants, although the use of anonymized UKRR data allowed us to examine these differences. Although we adjusted for observed response bias, there may be residual unobserved bias because of limited comparisons with aggregate UKRR data for study nonparticipants. We did not conduct a mediation analysis, hence for those variables with potential mediators, total effects only were measured. We focused on medication adherence (an area of considerable interest for caregivers of young adults on KRT), although strong evidence that this is directly linked to graft loss is lacking. Our medication adherence model only explained a third of the observed variance in medication adherence scores. We found an interaction between dialysis and ethnicity, so that Asian and black patients on dialysis did worse in relation to medication adherence. This could relate to sociocultural factors, but more work is required to understand these results. Pragmatically, it suggests these patients may require even greater clinical support.

Future studies should enhance the understanding of our findings. In summary, this study demonstrates potentially modifiable associations with the important outcomes of wellbeing and medication adherence in young adults on KRT. This evidence base should form the basis for future research aimed at improving clinical and QoL outcomes. As psychologic morbidity had a strong association with wellbeing and medication adherence, multidimensional interventions improving psychologic health should be developed to improve outcomes.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all our study participants for their involvement and the patients who piloted the survey. We are indebted to the research nurses and principal investigators at the various kidney units for recruiting to the study and we acknowledge the support of the National Institutes of Health Research Clinical Research Network (NIHR CRN). In particular, we would like to thank Sue Dawson for her guidance with study set-up. We are grateful to Shaun Mannings and Julie Gilg at the UK Renal Registry for their assistance with data linkage, and Mai Baquedano and Sam Story from the University of Bristol for support with the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) application. We thank all of the UK kidney centers for providing data to the UK Renal Registry and thank the Scottish Renal Registry for sharing the data they collect and validate in Scotland.

A.J.H. is funded on a Tony Wing clinical studentship from Kidney Care UK and Kidney Research UK.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the UK Renal Registry or UK Renal Association.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.02450218/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hamilton AJ, Clissold RL, Inward CD, Caskey FJ, Ben-Shlomo Y: Sociodemographic, psychologic health, and lifestyle outcomes in young adults on renal replacement therapy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1951–1961, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamilton AJ, Caskey FJ, Casula A, Ben-Shlomo Y, Inward CD: Psychosocial Health and Lifestyle Behaviors in Young Adults Receiving Renal Replacement Therapy Compared to the General Population: Findings From the SPEAK Study. Am J Kidney Dis 2018, doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Bailey PK, Hamilton AJ, Clissold RL, Inward CD, Caskey FJ, Ben-Shlomo Y, Owen-Smith A: Young adults’ perspectives on living with kidney failure: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ Open 8: e019926, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine : Young adult health and well-being: A position statement of the society for adolescent health and medicine. J Adolesc Health 60: 758–759, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dobbels F, Ruppar T, De Geest S, Decorte A, Van Damme-Lombaerts R, Fine RN: Adherence to the immunosuppressive regimen in pediatric kidney transplant recipients: A systematic review. Pediatr Transplant 14: 603–613, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tangkiatkumjai M, Walker DM, Praditpornsilpa K, Boardman H: Association between medication adherence and clinical outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease: A prospective cohort study. Clin Exp Nephrol 21: 504–512, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prihodova L, Nagyova I, Rosenberger J, Majernikova M, Roland R, Groothoff JW, van Dijk JP: Adherence in patients in the first year after kidney transplantation and its impact on graft loss and mortality: A cross-sectional and prospective study. J Adv Nurs 70: 2871–2883, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foster BJ: Heightened graft failure risk during emerging adulthood and transition to adult care. Pediatr Nephrol 30: 567–576, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Arendonk KJ, James NT, Boyarsky BJ, Garonzik-Wang JM, Orandi BJ, Magee JC, Smith JM, Colombani PM, Segev DL: Age at graft loss after pediatric kidney transplantation: Exploring the high-risk age window. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1019–1026, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG: Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42: 377–381, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacNeill SJ, Ford D: UK renal registry 19th annual report: Chapter 2 UK renal replacement therapy prevalence in 2015: National and centre-specific analyses. Nephron 137[Suppl 1]: 45–72, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton AJ, Braddon F, Casula A, Lewis M, Mallett T, Marks SD, Shenoy M, Sinha MD, Tse Y, Maxwell H: UK renal registry 19th annual report: Chapter 4 demography of the UK paediatric renal replacement therapy population in 2015. Nephron 137[Suppl 1]: 103–116, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venkat-Raman G, Tomson CR, Gao Y, Cornet R, Stengel B, Gronhagen-Riska C, Reid C, Jacquelinet C, Schaeffner E, Boeschoten E, Casino F, Collart F, De Meester J, Zurriaga O, Kramar R, Jager KJ, Simpson K; ERA-EDTA Registry : New primary renal diagnosis codes for the ERA-EDTA. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 4414–4419, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrans CE, Zerwic JJ, Wilbur JE, Larson JL: Conceptual model of health-related quality of life. J Nurs Scholarsh 37: 336–342, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bakas T, McLennon SM, Carpenter JS, Buelow JM, Otte JL, Hanna KM, Ellett ML, Hadler KA, Welch JL: Systematic review of health-related quality of life models. Health Qual Life Outcomes 10: 134, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton AJ, Casula A, Ben-Shlomo Y, Caskey FJ, Inward CD: The clinical epidemiology of young adults starting renal replacement therapy in the UK: Presentation, management and survival using 15 years of UK Renal Registry data. Nephrol Dial Transplant 32: 1434–1435, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massey EK, Meys K, Kerner R, Weimar W, Roodnat J, Cransberg K: Young adult kidney transplant recipients: Nonadherent and happy. Transplantation Nephrol Dial Transplant 99: e89–e96, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cukor D, Rosenthal DS, Jindal RM, Brown CD, Kimmel PL: Depression is an important contributor to low medication adherence in hemodialyzed patients and transplant recipients. Kidney Int 75: 1223–1229, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perales-Montilla CM, García-León A, Reyes-del Paso GA: Psychosocial predictors of the quality of life of chronic renal failure patients undergoing haemodialysis. Nefrologia 32: 622–630, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prihodova L, Nagyova I, Rosenberger J, Roland R, van Dijk JP, Groothoff JW: Impact of personality and psychological distress on health-related quality of life in kidney transplant recipients. Transpl Int 23: 484–492, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenstein S, Siegal B: Compliance and noncompliance in patients with a functioning renal transplant: A multicenter study. Transplantation 66: 1718–1726, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmer S, Vecchio M, Craig JC, Tonelli M, Johnson DW, Nicolucci A, Pellegrini F, Saglimbene V, Logroscino G, Fishbane S, Strippoli GF: Prevalence of depression in chronic kidney disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Kidney Int 84: 179–191, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gale C, Deary I, Stafford M: A life course approach to psychological and social wellbeing. In: A Life Course Approach to Healthy Ageing, edited by Kuh D, Cooper R, Hardy R, Richards M, Ben-Shlomo Y, Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 2013, pp 46–64 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ibrahim N, Teo SS, Che Din N, Abdul Gafor AH, Ismail R: The role of personality and social support in health-related quality of life in chronic kidney disease patients. PLoS One 10: e0129015, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levine R, Javalkar K, Nazareth M, Faldowski RA, de Ferris MD, Cohen S, Cuttance J, Hooper SR, Rak E: Disparities in health literacy and healthcare utilization among adolescents and young adults with chronic or end-stage kidney disease. J Pediatr Nurs 38: 57–61, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sacks RM, Greene J, Hibbard J, Overton V, Parrotta CD: Does patient activation predict the course of type 2 diabetes? A longitudinal study. Patient Educ Couns 100: 1268–1275, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wileman V, Chilcot J, Armitage CJ, Farrington K, Wellsted DM, Norton S, Davenport A, Franklin G, Da Silva Gane M, Horne R, Almond M: Evidence of improved fluid management in patients receiving haemodialysis following a self-affirmation theory-based intervention: A randomised controlled trial. Psychol Health 31: 100–114, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wileman V, Farrington K, Chilcot J, Norton S, Wellsted DM, Almond MK, Davenport A, Franklin G, Gane MS, Armitage CJ: Evidence that self-affirmation improves phosphate control in hemodialysis patients: A pilot cluster randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med 48: 275–281, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts BW, Luo J, Briley DA, Chow PI, Su R, Hill PL: A systematic review of personality trait change through intervention. Psychol Bull 143: 117–141, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winkley K, Ismail K, Landau S, Eisler I: Psychological interventions to improve glycaemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 333: 65, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Normansell R, Kew KM, Stovold E: Interventions to improve adherence to inhaled steroids for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4: CD012226, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Proudfoot J, Guest D, Carson J, Dunn G, Gray J: Effect of cognitive-behavioural training on job-finding among long-term unemployed people. Lancet 350: 96–100, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mellerio H, Alberti C, Labèguerie M, Andriss B, Savoye E, Lassalle M, Jacquelinet C, Loirat C; French Working Group on the Long-Term Outcome of Transplanted Children : Adult social and professional outcomes of pediatric renal transplant recipients. Transplantation 97: 196–205, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abel GA, Barclay ME, Payne RA: Adjusted indices of multiple deprivation to enable comparisons within and between constituent countries of the UK including an illustration using mortality rates. BMJ Open 6: e012750, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamilton AJ, Gair R, Elias R, Chrysochou C: Renal young adult transition services: A national survey. British Journal of Renal Medicine 22: 36–38, 2017 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.