Abstract

This study examined demographic and psychosocial correlates associated with persistence/recurrence of and remission from at least one of ten DSM-5 substance use disorders (SUDs) and three substance-specific SUDs (i.e., alcohol, cannabis, and prescription opioids). Data were collected from structured diagnostic interviews and national prevalence estimates were derived from the 2012–2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. An estimated 25.4% of the U.S. population had at least one prior-to-past-year (prior) SUD. Among individuals with any prior SUDs, the prevalence of past-year substance use and DSM-5 symptomology was as follows: abstinence (14.2%), asymptomatic use (36.9%), symptomatic use (10.9%), and persistent/recurrent SUD (38.1%). Among individuals with prior SUDs, design-based multinomial logistic regression analysis revealed that young adulthood, higher educational attainment, higher personal income, never having been married, being divorced/separated/widowed, lack of lifetime substance use treatment, and stressful life events predicted significantly greater odds of past-year persistent/recurrent SUDs, relative to abstinence. In addition, remission from a prior tobacco use disorder decreased the probability of past-year persistent/recurrent SUD, relative to abstinence. Stressful life events were the only common correlates across the aggregation of all SUDs and each substance-specific SUD, but differences were found for specific stressful life events between drug classes. The majority of adults with prior DSM-5 SUDs continued to report past-year symptomatic substance use, while only one in seven individuals were abstinent. The findings suggest the value of examining remission associated with both substance-specific SUDs and aggregation of SUDs based on the shared and unique correlates of persistent/recurrent SUDs; this is especially true for stressful life events, which could be useful targets for enhancing clinical care and interventions.

Keywords: substance use disorders, DSM-5, stress, remission, abstinence

1. Introduction

Over 65 million U.S. adults have met criteria for alcohol use disorders (AUDs), while more than 20 million have met criteria for other drug use disorders (DUDs) involving sedatives, tranquilizers, non-heroin opioids, stimulants, hallucinogens, cannabis, cocaine, heroin, inhalants, or other drugs (e.g., club drugs) in their lifetime (Grant et al., 2015a; Grant et al., 2016). Most individuals with substance use disorders (SUDs) never utilize substance use treatment services, despite the substantial disability and psychiatric comorbidity associated with SUDs (Blanco et al., 2007; Compton, Thomas, Stinson, & Grant, 2007; Grant et al., 2015a; Grant et al., 2016; McCabe, Cranford, & West, 2008). While remission from AUDs and other substance-specific DUDs has been investigated (Blanco et al., 2013; Dawson, Goldstein, & Grant, 2007; Dawson et al., 2005; Moss, Chen, & Yi, 2010; Fenton et al., 2012; White, 2012), there have been few nationally representative studies that have examined the prevalence and correlates associated with remission from “any” SUD (i.e., at least one SUD from an aggregation of all SUDs) and potential differences across the most prevalent substance-specific SUDs (e.g., alcohol, cannabis, and non-heroin opioids), especially based on DSM-5 criteria in the U.S. general population (Calabria et al., 2010; Compton, Dawson, Conway, Brodsky, & Grant, 2013; Lopez-Quintero et al., 2011; White, 2012).

The substance use behaviors and SUD profiles of individuals entering substance use treatment programs have changed dramatically over the past two decades according to the Treatment Episode Data Set, which collects data on admissions to substance use treatment facilities in the United States (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2006; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2016). The percentage of substance use treatment admissions reporting cannabis, opioids (including heroin), and stimulants as the primary substance of misuse increased from approximately 22% in 1993 to 55% in 2014 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2006; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2016). Notably, nearly half of those reporting alcohol as the primary substance also reported a secondary substance other than alcohol (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2006; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2016). Despite this shift, there is limited knowledge on the prevalence of remission from DSM-5 SUDs involving the aggregation of alcohol and other drugs, including correlates associated with complete abstinence, asymptomatic substance use, partial remission, or persistent/recurrent SUDs.

To date, covariates identified as being associated with remission from AUDs and DUDs include age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, marital status, childhood adversity, educational attainment, nicotine dependence, several psychiatric comorbidities and substance use treatment history (Calabria et al., 2010; Compton et al., 2013; Dawson et al., 2007; Lopez-Quintero et al., 2011; Moss et al., 2010; White, 2012). For example, one prior national study examined the prevalence and correlates associated with remission from DSM-IV alcohol dependence and found that college education and personality disorders each decreased the likelihood of abstinent remission, while being married was associated with increased odds of abstinent remission (Dawson et al., 2005). Furthermore, a second national study identified some correlates of abstinence or asymptomatic remission from DSM-IV drug-specific dependence that were similar across at least two substances but found no common predictors of remission from nicotine, alcohol, and cannabis dependence, suggesting that processes of remission from dependence may be similar but not identical across substances (Lopez-Quintero et al., 2011).

Several prior studies have neglected to examine the role of stressful life events in remission from SUDs, despite evidence that stressful life events are significantly associated with the development of AUDs, cannabis use disorder, other DUDs, and relapse from alcohol dependence (Blanco et al., 2014; McCabe, Cranford, & Boyd, 2016; Myers, McLaughlin, Wang, Blanco, & Stein, 2014; Pilowsky, Keyes, Geier, Grant, & Hasin, 2013). For instance, it remains unclear which specific stressful life events (e.g., divorce) are associated with remission from SUDs and whether the role of specific stressful life events varies between developmental periods (e.g., young adulthood versus older adulthood).

A key public health question is whether the prevalence and correlates of remission vary between the most prevalent substance-specific disorders (i.e., alcohol, cannabis, prescription opioids) and an aggregation of SUDs among adults in the United States. To date, there have been no studies that have addressed this question despite experts calling for the need for more research focused on potential variations between substance-specific disorders and an aggregation of SUDs (Grant et al., 2016). Clearly, a more comprehensive understanding of the potential correlates associated with remission from DSM-5 SUDs in the United States is needed because the natural course of SUDs can vary by substance and this information could be useful for enhancing and targeting substance use treatment modalities. The objectives of the present study were to examine 1) prevalence and demographic, psychiatric and psychosocial correlates of remission and persistence/recurrence associated with the aggregation of ten SUDs (i.e., alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants, prescription opioids, sedatives/tranquilizers, stimulants, and other drugs); 2) prevalence and correlates of persistence/recurrence (vs. abstinence) associated with three of the most prevalent substance-specific disorders (i.e., alcohol, cannabis, and prescription opioids); and 3) associations between specific individual stressful life events and persistent/recurrent SUDs.

2. Materials and methods

The present study used data collected from the 2012–2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC-III) to examine DSM-5 SUDs among the general civilian noninstitutionalized population of adults 18 years of age and older in the United States. The NESARC-III included the NIAAA Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-5 (AUDADIS-5), a fully structured diagnostic interview conducted in households. The NESARC-III sample included adults living in households, military personnel living off base, and adults residing in the following group quarters: boarding or rooming houses, non-transient hotels, shelters, facilities for housing workers, college quarters and group homes. In-person interviews were conducted, and the household, person, and overall response rates were 72%, 84%, and 60%, respectively. The NESARC-III sample design and weighting procedures, which adjust for potential biases introduced by the survey nonresponse, have been described in more detail elsewhere (Grant et al., 2015b).

2.1. Sample

The NESARC-III sample included 8,628 adults who reported a prior-to-past-year (prior) DSM-5 SUD. After applying the final survey weights, these adults represented a population that was 58.8% male, 76.3% White, 10.5% Hispanic, 8.3% African-American, and 4.9% Asian, Native American or other racial/ethnic categories. Approximately 12.7% of the population were aged 18–24 years old while 42.6% were 25–44 years, 36.1% were 45–64 years and 8.6% were 65 years or older.

2.2. Measures

The NESARC-III survey assessed demographic and background characteristics including age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, personal income, sexual identity, and marital status.

DSM-5 substance use disorders (SUDs) were assessed according to the criteria of the DSM-5 using the AUDADIS-5 and included substance-specific diagnoses for ten substances: alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants, prescription opioids, sedatives/tranquilizers, stimulants, and other drugs (e.g., ecstasy, ketamine). Substance-specific diagnoses were made for the past-year and prior-to-past-year (prior) timeframes. Each DSM-5 SUD diagnosis required 2 or more of the 11 criteria in the 12 months preceding the interview or previously for each drug-specific SUD. The test-retest reliability and validity of each AUDADIS-5 DSM-5 SUD diagnosis have been examined in psychometric studies, with test-retest reliability ranging from fair to good (κ = 0.4 – 0.6) and dimensional criteria scales (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] = 0.5 – 0.9, respectively) ranging from fair to excellent (Grant et al., 2015a; Grant et al., 2015c; Grant et al., 2016; Hasin et al., 2015a).

DSM-5 psychiatric disorders were assessed including anxiety disorders (i.e., agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic, social and specific phobias), mood disorders (i.e., bipolar, dysthymia, and major depressive disorder), eating disorders (i.e., anorexia nervosa, binge-eating disorder, and bulimia nervosa), personality disorders (i.e., antisocial personality disorders, borderline, and schizotypal), and posttraumatic stress disorder. Consistent with the DSM-5, all these diagnoses excluded substance- and medical illness–induced disorders. Reliability and validity of the DSM-5 based AUDADIS-5 diagnoses of these psychiatric disorders have been established in numerous psychometric studies (Grant et al., 2015c; Hasin et al., 2015b). Test-retest reliability of AUDADIS-5 and DSM-5 diagnoses of these psychiatric disorders has been shown to be fair to good (κ range, 0.4–0.7), while reliability of DSM-5 dimensional criteria scales has been shown to be fair to excellent (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] = 0.5 – 0.9; Grant et al., 2015c; Hasin et al., 2013, 2015b).

Past-year remission status was based on DSM-5 criteria and broken into the following four sub-categories: 1) Past-year abstinence / full remission: No substance use in the past year; 2) Past-year asymptomatic use: Used at least one substance at least once but did not experience any DSM-5 SUD symptoms other than craving in the past year; 3) Past-year symptomatic use / partial remission: Recurrence of DSM-5 SUD symptoms other than craving alone in the past year, but did not meet full criteria for any DSM-5 SUD; and 4) Past-year persistent/recurrent SUD: Continued to meet criteria for a DSM-5 SUD in the past year.

Childhood adversity was assessed based on questions regarding exposure to childhood adversity occurring before age 18, including emotional abuse (e.g., insults from caregivers), physical abuse (e.g., violent behavior from caregivers) and exposure to family violence (e.g., violent behavior toward mother/caregiver), based on items from the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, 1979). Childhood neglect was assessed based on items from the Children’s Trauma Questionnaire (e.g., not provided with regular meals) (Bernstein & Fink, 1994). Unwanted sexual contact items that involved an adult, or that occurred when the respondent was too young to know what was happening, were used to assess childhood sexual abuse based on past work (Wyatt, 1985). Additional childhood adversities were assessed including serious parental mental illness, parental incarceration, parental suicide or attempted suicide, and parental SUD, and indicators of each of these adversities were summed to form a childhood adversities scale. The individual adverse childhood events (ACEs) were coded differently according severity and frequency. For instance, a respondent who reported any instances of more severe events (e.g., childhood sexual abuse) was defined as having an adverse childhood event (ACE), while reporting less severe events (e.g., insults from caregivers) required a higher threshold/frequency to be defined as an ACE. The test-retest reliability of these childhood adversity measures has been shown to be good to excellent (ICCs = 0.7 – 0.9; Ruan et al., 2008).

Stressful life events were summed to create a scale consisting of 16 stressful events experienced during the 12 months preceding the NESARC-III interview. The specific stressful events included 1) job change, 2) interpersonal problems at work, 3) problems with a neighbor, 4) victim of theft, 5) personal property destroyed, 6) family member/close friend physically assaulted, 7) personal legal troubles, 8) family member/close friend had legal troubles, 9) moved or new roommate, 10) fired from job, 11) unemployed, 12) death of a family member/close friend, 13) bankruptcy, 14) unmanageable financial debt, 15) homeless, and 16) separation, divorce or broke off steady relationship, all based on prior work (Ruan et al., 2008; McLaughlin, Conron, Koenen, & Gilman, 2010; Myers et al., 2014). The stressful life events scale was defined as the sum of all stressful life events experienced in the past 12 months (range 0–16) and the test–retest reliabilities of this past-year stressful life event scale has been shown to be excellent (ICC = 0.9; Ruan et al., 2008).

Lifetime substance use treatment and other help-seeking history was assessed by asking respondents with a prior DSM-5 SUD whether they had ever sought help or seen anyone to get help related to their use of alcohol and/or other drugs. Substance use treatment and other help-seeking was defined as seeking help related to their drinking and/or drug use from self-help or mutual-help groups (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous), social services (e.g., family services, employee assistance program, clergy), substance use services (e.g., alcohol/drug detoxification, inpatient treatment, outpatient clinic, rehabilitation program, halfway house, private physician, psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, or other professional), emergency rooms or crisis centers.

2.3. Data Analysis

All analyses in this study were design-based, using the sampling weights provided in the NESARC-III data set (adjusted for nonresponse) to compute representative population estimates, and the available codes describing the sampling strata and sampling clusters to compute linearized variance estimates for the weighted estimates. Initial analyses focused on estimation of the past-year prevalence of remission status among the subpopulation of U.S. adults with prior SUDs. Next, for each subpopulation defined by past-year remission status, we estimated the distributions of race/ethnicity (Black, Hispanic, White, and Other), age (18–24 years, 25–44 years, 45–64 years, and 65 years and over), educational attainment (more than high school, high school, and less than high school), income (less than $20,000, $20,000 - $39,999, and $40,000 and above), sexual identity (heterosexual, gay/lesbian, bisexual, and not sure or unknown), marital status (married/cohabiting, never married, and divorced/separated/widowed), level of childhood adversity, number of stressful life events, type of DSM-5 SUD (AUD only, AUD & DUD, and DUD only), DSM-5 tobacco use disorder, DSM-5 mental health disorders including any anxiety, eating, mood, personality, and posttraumatic stress disorders (yes / no), and lifetime substance use treatment utilization (yes / no).

Next, we estimated multinomial logistic regression models of past-year remission status including all of the aforementioned covariates. In addition to testing the relationships of each of the covariates with past-year remission status for significance (using design-adjusted multi-parameter Wald tests), we also tested several interactions. We then estimated separate multinomial logistic regression models of past-year remission status among individuals with the most prevalent SUDs (i.e., alcohol, cannabis, and prescription opioids) to identify correlates associated with higher odds of past-year persistent/recurrent SUDs for each drug-specific use disorder relative to past-year abstinence, including all of the aforementioned covariates as well as specific stressful life events. We used abstinent remission as the comparison group in the multinomial logistic regression models because this approach was the most parsimonious and we identified several distinct correlates associated with abstinent remission as opposed to other remission categories including asymptomatic use.

Finally, because item-missing data on selected covariates and the dependent variables of interest reduced our analytic sample sizes for model-fitting slightly in some cases, we refit all models in a multiple imputation analysis framework. Specifically, in separate multiple imputation analyses, we first identified all cases in our subpopulation of interest for a given model (e.g., those with a prior AUD), and then imputed all missing values for those cases five times using the method of chained equations (Raghunathan, Lepkowski, Van Hoewyk, & Solenberger, 2001). We included all variables in our models of interest in the imputation models, in addition to the sample design variables (including the final adjusted sampling weights). The svy: and mi: commands in the Stata software (Version 15.1), including appropriate options for estimation focusing on the subpopulation of individuals with prior-to-past-year SUDs, were used for all analyses, and the Stata code used for all analyses is available upon request.

3. Results

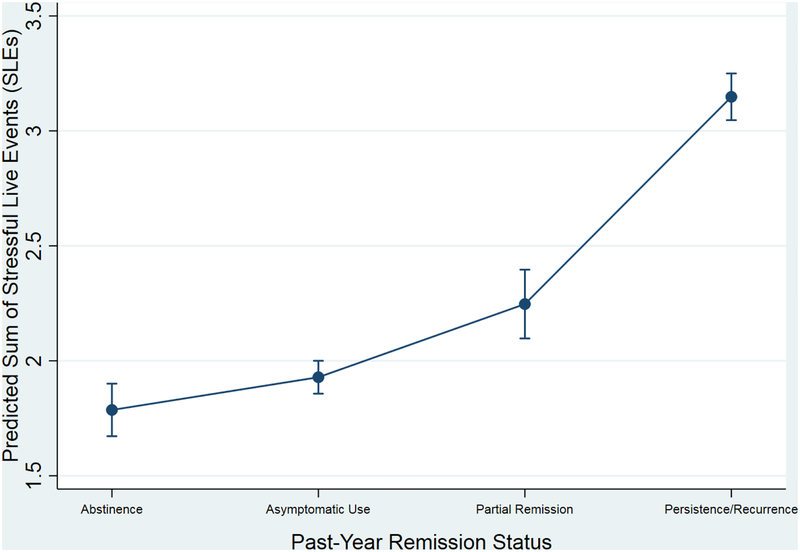

The estimated prevalence of any prior DSM-5 SUDs in the NESARC-III target population was 25.4% (SE = 0.5%). Among U.S. adults with any prior SUDs (Table 1), the estimated distribution of past-year remission status was as follows: abstinence (14.2%), asymptomatic substance use (36.9%), partial remission (10.9%), and persistent/recurrent SUD (38.1%). There was a significant association between each variable listed in Table 1 and past-year remission status (p <= 0.001). For instance, the estimated mean counts of past-year stressful life events increased in a stepwise fashion as a function of past-year remission status as follows: abstinence (1.79), asymptomatic substance use (1.93), partial remission (2.25), and persistent/recurrent SUD (3.15); F(3,111) = 157.3, p < 0.0001. Notably, all pairwise comparisons of mean counts of past-year stressful life events between abstinence or asymptomatic use and partial remission or persistent/recurrent SUD were significant (p < 0.01, see Figure 1 and Supplemental Table 1).

Table 1.

Weighted Estimates of Percentages and Means (with Design-Adjusted Standard Errors in Parentheses) Describing Distributions of Selected Socio-Demographic Characteristics, Disorder Histories, Childhood Adversity, and Stressful Live Events by Past-Year Remission Status, for Adults with Prior DSM-5 Substance Use Disorder (SUD)

| Prior-to-Past-Year (Prior) SUD Sample (n = 8,503) | Past-Year Remission Status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past-Y ear Abstinence (n=l,168) | Past-Y ear Asymptomatic Substance Use (n=2,912) | Past-Year Partial Remission (n=917) | Past-Year Persistent/Recurrent SUD (n=3,506) | ||

| Overall | 100.0% | 14.2% (0.5) | 36.9% (0.8) | 10.9% (0.4) | 38.1% (0.8) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 41.2% (0.6) | 39.7% (1.6) | 45.0% (0.9) | 38.0% (1.7) | 38.9% (0.9) |

| Male | 58.8% (0.6) | 60.3% (1.6) | 55.0% (0.9) | 62.0% (1.7) | 61.1% (0.9) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White | 76.3% (0.8) | 78.4% (1.4) | 81.8% (0.9) | 78.3% (1.5) | 69.7% (1.1) |

| Black | 8.3% (0.6) | 8.4% (0.9) | 5.5% (0.5) | 7.3% (0.8) | 11.2% (1.0) |

| Hispanic | 10.5% (0.6) | 9.0% (1.1) | 8.4% (0.6) | 10.5% (1.2) | 13.1% (0.8) |

| Other | 4.9% (0.5) | 4.2% (0.7) | 4.3% (0.6) | 3.9% (0.8) | 6.0% (0.6) |

| Age | |||||

| 18–24 | 12.7% (0.5) | 3.1% (0.5) | 5.0% (0.5) | 13.3% (1.4) | 23.4% (1.0) |

| 25–44 | 42.6% (0.7) | 23.5% (1.6) | 42.9% (0.9) | 47.2% (1.9) | 48.2% (1.1) |

| 45–64 | 36.1% (0.6) | 51.7% (1.6) | 41.8% (0.9) | 32.7% (1.9) | 25.7% (1.0) |

| 65+ | 8.6% (0.4) | 21.7% (1.3) | 10.3% (0.6) | 6.8% (1.1) | 2.6% (0.3) |

| Education | |||||

| Less than HS | 10.2% (0.5) | 16.1% (1.3) | 7.1% (0.5) | 7.2% (1.0) | 11.8% (0.7) |

| High School / GED | 24.9% (0.6) | 27.2% (1.4) | 22.5% (1.0) | 23.4% (2.1) | 26.9% (0.8) |

| More than HS / GED | 64.9% (0.9) | 56.7% (1.7) | 70.4% (1.1) | 69.5% (2.4) | 61.3% (1.0) |

| Income | |||||

| $40k or higher | 33.7% (0.9) | 29.2% (0.2) | 42.4% (1.4) | 36.5% (2.1) | 26.3% (1.1) |

| $20k to $39,999 | 27.5% (0.7) | 27.6% (0.2) | 28.2% (1.1) | 29.3% (1.8) | 26.3% (0.8) |

| Below $20k | 38.8% (0.9) | 43.2% (0.2) | 29.4% (1.3) | 34.2% (1.7) | 47.4% (1.2) |

| Sexual identity | |||||

| Heterosexual | 94.0% (0.4) | 96.2% (0.7) | 94.8% (0.5) | 94.4% (1.0) | 92.2% (0.5) |

| Gay/Lesbian | 2.4% (0.2) | 1.9% (0.5) | 2.2% (0.3) | 3.0% (0.7) | 2.6% (0.3) |

| Bisexual | 2.5% (0.2) | 1.0% (0.3) | 2.1% (0.3) | 2.1% (0.5) | 3.5% (0.4) |

| Not sure/unknown | 1.2% (0.2) | 0.9% (0.2) | 0.9% (0.2) | 0.5% (0.3) | 1.7% (0.3) |

| Childhood adversity1 | 3.89 (0.06) | 4.25 (0.17) | 3.62 (0.10) | 3.41 (0.16) | 4.15 (0.08) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married/cohabiting | 56.0% (0.7) | 60.6% (1.6) | 67.6% (1.1) | 57.9% (1.9) | 42.5% (1.2) |

| Never married | 24.6% (0.7) | 13.0% (1.1) | 13.7% (0.8) | 25.5% (1.5) | 39.3% (1.2) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 19.4% (0.5) | 26.4% (1.2) | 18.6% (0.9) | 16.6% (1.3) | 18.2% (0.8) |

| Stressful life events2 | 2.41 (0.03) | 1.79 (0.06) | 1.93 (0.04) | 2.25 (0.08) | 3.15 (0.05) |

| Type of prior SUD | |||||

| Alcohol use disorder only | 68.0% (0.6) | 65.6% (1.7) | 76.0% (1.0) | 73.1% (2.0) | 59.7% (1.1) |

| Alcohol and other SUD | 22.9% (0.5) | 25.7% (1.6) | 15.8% (0.8) | 16.5% (1.6) | 30.5% (1.0) |

| Non-alcohol SUD only | 9.1% (0.4) | 8.7% (1.0) | 8.1% (0.6) | 10.4% (1.2) | 9.8% (0.7) |

| Tobacco use disorder (TUD) | |||||

| No lifetime TUD | 45.0% (0.8) | 36.1% (1.7) | 50.3% (1.1) | 50.2% (2.0) | 41.8% (1.1) |

| Prior TUD+ only | 16.8% (0.6) | 32.8% (1.6) | 20.0% (0.9) | 13.0% (1.5) | 8.6% (0.5) |

| Prior and/or past-year TUD+ | 38.2% (0.8) | 31.1% (1.6) | 29.7% (1.1) | 36.8% (2.2) | 49.6% (1.2) |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | |||||

| No lifetime PTSD | 87.5% (0.5) | 87.3% (1.0) | 89.3% (0.7) | 90.1% (1.2) | 85.0% (0.8) |

| Prior PTSD+ only | 2.7% (0.2) | 3.5% (0.5) | 2.7% (0.4) | 2.2% (0.5) | 2.7% (0.3) |

| Prior and/or past-year PTSD+ | 9.8% (0.4) | 9.2% (0.8) | 8.1% (0.6) | 7.7% (1.0) | 12.3% (0.8) |

| Anxiety disorders3 | |||||

| No lifetime anxiety disorder | 71.5% (0.6) | 71.4% (1.7) | 72.3% (0.9) | 75.2% (1.9) | 69.6% (1.1) |

| Prior anxiety disorder only | 6.7% (0.4) | 6.9% (0.8) | 7.7% (0.7) | 6.9% (1.2) | 5.6% (0.5) |

| Prior and/or past-year anxiety+ | 21.9% (0.5) | 21.7% (1.6) | 20.0% (0.8) | 17.9% (1.7) | 24.8% (0.9) |

| Mood disorders4 | |||||

| No lifetime mood disorder | 60.9% (0.7) | 58.5% (2.1) | 63.7% (1.0) | 67.0% (1.9) | 57.3% (1.1) |

| Prior mood disorder only | 17.1% (0.5) | 19.5% (1.6) | 20.1% (0.9) | 15.0% (1.3) | 13.9% (0.7) |

| Prior and/or past-year mood+ | 22.0% (0.6) | 22.0% (1.5) | 16.2% (0.8) | 18.0% (1.5) | 28.8% (1.0) |

| Substance treatment/help seeking | |||||

| No | 73.0% (0.5) | 55.3% (1.9) | 83.1% (0.8) | 79.8% (1.5) | 67.9% (0.9) |

| Yes | 27.0% (0.5) | 44.7% (1.9) | 16.9% (0.8) | 20.2% (1.5) | 32.1% (0.9) |

Notes. There was a significant association between each variable listed in Table 1 and each past-year remission status (p < 0.001, with the exception of anxiety disorders, where p = 0.0012). Prior = prior-to-past-year.

Actual counts of adverse childhood experiences (0–24).

Actual counts of stressful life events (0–16).

DSM-5 anxiety disorders consisted of agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic, social and/or specific phobias.

DSM-5 mood disorders consisted of bipolar, dysthymia, and/or major depressive disorder.

Figure 1.

Estimated Mean Counts of Past-Year Stressful Life Events as a Function of Past-Year Substance Use Disorder Remission Status, with 95% Confidence Intervals

The design-based multinomial logistic regression analysis showed that among U.S. adults with any prior DSM-5 SUDs (n = 7,690), every additional stressful life event in the past year significantly increased the odds of past-year partial remission/symptomatic substance use (p < 0.01) and past-year persistent/recurrent SUD (p < 0.001) relative to past-year abstinent remission (see Table 2), holding the other covariates fixed. In addition, other covariates significantly increased (p < 0.01) the probability of past-year persistent/recurrent SUD relative to past-year abstinence, including being aged 18–24, having higher educational attainment (more than high school), having higher personal income, never having been married, being divorced/separated/widowed, and having no lifetime history of substance use treatment. Furthermore, having a prior tobacco use disorder but no past-year tobacco use disorder significantly decreased (p < 0.001) the probability of past-year persistent/recurrent SUD relative to past-year abstinence. We tested the interactions between stressful life events, childhood adversities, and gender, and no three-way interactions were found. When removing the three-way interactions from the models, none of the two-way interactions were found to be significant at the 0.01 level either. Finally, the multiple imputation analysis results mirrored the complete case analyses, suggesting minimal bias in the model estimated based on the complete cases.

Table 2.

Correlates of Past-Year Remission from Prior-to-Past-Year DSM-5 Substance Use Disorder (SUD)

| Past-Year Remission Status (n = 7,690) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Asymptomatic Use vs. Abstinence | Symptomatic Use vs. Abstinence | Persistent/Recurrent SUD vs. Abstinence | |

| Correlates | AOR [95% Cl] | AOR [95% Cl] | AOR [95% Cl] |

| Sex | |||

| Female | — | — | — |

| Male | 0.9 [0.7, 1.0] | 1.2 [0.9, 1.5] | 1.2 [1.0, 1.5] |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | — | — | — |

| Black | 0.7 [0.5, 1.0] | 0.9 [0.6, 1.3] | 1.3 [0.9, 1.8] |

| Hispanic | 0.9 [0.6, 1.2] | 1.0 [0.7, 1.5] | 1.2 [0.9, 1.8] |

| Other | 1.1 [0.7, 1.7] | 1.0 [0.6, 1.6] | 1.3 [0.9, 2.0] |

| Age | |||

| 18–24 | — | — | — |

| 25–44 | 1.0 [0.6, 1.7] | 0.5 [0.6, 0.8]** | 0.4 [0.2, 0.6]*** |

| 45–64 | 0.5 [0.3, 0.8]** | 0.2 [0.1, 0.3]*** | 0.1 [0.1,0.2]*** |

| 65+ | 0.3 [0.2, 0.5]*** | 0.1 [0.1, 0.2]*** | 0.04 [0.02, 0.1]*** |

| Education | |||

| More than HS | — | — | — |

| High School | 0.9 [0.7, 1.1] | 0.9 [0.6, 1.1] | 1.0 [0.8, 1.2] |

| Less than HS | 0.5 [0.4, 0.7]*** | 0.5 [0.3, 0.7]*** | 0.7 [0.5, 0.9]** |

| Income | |||

| $40k or higher | — | — | — |

| $20k to $39,999 | 0.7 [0.6, 0.9] | 0.8 [0.5, 1.1] | 0.7 [0.5, 1.0] |

| Below $20k | 0.5 [0.4, 0.7]*** | 0.6 [0.4, 0.8]** | 0.6 [0.5, 0.8]** |

| Sexual identity | |||

| Heterosexual | — | — | — |

| Gay/Lesbian | 1.2 [0.6, 2.3] | 1.4 [0.7, 2.9] | 1.0 [0.5, 1.7] |

| Bisexual | 2.3 [1.1, 4.8] | 1.8 [0.7, 4.3] | 2.0 [1.0, 4.3] |

| Not sure/unknown | 1.0 [0.3, 3.0] | 0.8 [0.2, 3.4] | 1.9 [0.7, 5.2] |

| Childhood adversities1 | 0.99 [0.97, 1.02] | 0.98 [0.95, 1.01] | 0.99 [0.97, 1.01] |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/cohabiting | — | — | — |

| Never married | 0.9 [0.6, 1.2] | 1.2 [0.9, 1.7] | 1.8 [1.4, 2.4]*** |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 1.0 [0.8, 1.2] | 1.1 [0.8, 1.5] | 1.4 [1.1, 1.7]** |

| Stressful life events2 | 1.1 [1.0, 1.1] | 1.1 [1.0, 1.2]** | 1.2 [1.1, 1.3]*** |

| Type of prior SUD | |||

| Alcohol use disorder only | — | — | — |

| Alcohol and other SUD | 0.7 [0.5, 0.9] | 0.7 [0.5, 1.1] | 1.2 [0.9, 1.5] |

| Non-alcohol SUD only | 0.8 [0.6, 1.2] | 1.0 [0.7, 1.6] | 0.9 [0.6, 1.2] |

| Tobacco use disorder (TUD) | |||

| No lifetime TUD | — | — | — |

| Prior TUD+ only | 0.6 [0.5, 0.7]*** | 0.4 [0.3, 0.6]*** | 0.3 [0.3, 0.4]*** |

| Prior and/or past-year TUD+ | 1.1 [0.8, 1.3] | 1.2 [0.9, 1.5] | 1.3 [1.1, 1.6] |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | |||

| No lifetime PTSD | — | — | — |

| Prior PTSD+ only | 1.2 [0.6, 2.2] | 1.0 [0.5, 2.0] | 0.9 [0.4, 1.7] |

| Prior and/or past-year PTSD+ | 1.1 [0.8, 1.5] | 0.8 [0.5, 1.4] | 0.9 [0.6, 1.3] |

| Anxiety disorders3 | |||

| No lifetime anxiety disorder | — | — | — |

| Prior anxiety disorder only | 1.5 [1.0, 2.31 | 1.7 [0.9,3.01 | 1.5 [1.0,2.11 |

| Prior and/or past-year anxiety+ | 1.1 [0.8, 1.4] | 1.0 [0.7, 1.5] | 1.2 [0.9, 1.6] |

| Mood disorders4 | |||

| No lifetime mood disorder | — | — | — |

| Prior mood disorder only | 1.0 [0.7, 1.3] | 0.7 [0.5, 1.1] | 0.8 [0.6, 1.1] |

| Prior and/or past-year mood+ | 0.7 [0.5, 0.9]** | 0.8 [0.6, 1.1] | 1.0 [0.8, 1.4] |

| Substance treatment/help seeking | |||

| No | — | — | — |

| Yes | 0.3 [0.2, 0.4]*** | 0.3 [0.2, 0.4]*** | 0.5 [0.4, 0.6]*** |

Notes. AOR=odds ratio from multiple multinomial regression analysis adjusted for all correlates. 95% CI = confidence interval.

— = reference group.

p < .01

p < 0.001. Prior = prior-to-past-year.

Actual counts of adverse childhood experiences (0–24).

Actual counts of stressful life events (0–16).

DSM-5 anxiety disorders consisted of agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic, social and/or specific phobias.

DSM-5 mood disorders consisted of bipolar, dysthymia, and/or major depressive disorder.

Table 3 presents estimates from models fitted to subpopulations of individuals with specific prior-to-past-year SUDs (alcohol, marijuana, and opioids); the sample sizes for the models are therefore smaller than the sample size for the more general subpopulation of individuals with any prior-to-past-year SUD analyzed in Table 2. We found that stressful life events was the only correlate that significantly increased the probability of past-year persistent/recurrent drug-specific disorder for each drug class, relative to past-year abstinence. Similar to the results for any prior DSM-5 SUDs, every additional stressful life event significantly increased the odds of a past-year drug-specific use disorder for each drug class, including alcohol (p < 0.001), cannabis (p < 0.001), and prescription opioids (p < 0.001). Other covariates significantly increasing (p < 0.01) the probability of past-year persistent/recurrent drug-specific use disorder relative to past-year abstinence for at least two substances included being aged 18–24, lower educational attainment, and never having been married. Similar to the results for any prior DSM-5 SUDs, having a prior tobacco use disorder but no past-year tobacco use disorder significantly decreased the probability of past-year persistent/recurrent alcohol use disorder (p < 0.001) and past-year cannabis use disorder (p < 0.01) relative to past-year abstinence. When testing the interactions for individuals with a prior cannabis use disorder, we found weak evidence (p = 0.03) of an interaction between age and stressful life events, where the relationship of stressful life events with the probability of having persistent / recurrent cannabis use disorder was negative for the oldest age group but positive for the other three groups. Interestingly, the relationships of several covariates with remission status differed considerably across drug classes. For instance, having lower educational attainment significantly increased (p < 0.01) the probability of past-year persistence/recurrence relative to past-year abstinence for those with prior prescription opioid use disorders, while having lower educational attainment significantly decreased (p < 0.01) the probability of past-year persistence/recurrence relative to past-year abstinence for those with prior alcohol or cannabis use disorders.

Table 3.

Correlates of Persistent/Recurrent Past-Year SUD among Adults with Prior-to-Past-Year Substance-Specific SUDs

| Past-Year Persistent/Recurrent Alcohol Use Disorder vs. Abstinence (n=6,966 with prior AUD) | Past-Year Persistent/Recurrent Cannabis Use Disorder vs. Abstinence (n=l,563 with prior CUD) | Past-Year Persistent/Recurrent Rx Opioid Use Disorder vs. Abstinence (n=440 with prior OUD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlates | AOR [95% Cl] | AOR [95% Cl] | AOR [95% Cl] |

| Sex | |||

| Female | — | — | — |

| Male | 1.3 [1.1, 1.7] | 1.9 [1.2, 2.8]** | 1.1 [0.6, 2.1] |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | — | — | — |

| Hispanic | 1.3 [0.9, 1.9] | 2.5 [1.5, 4.1]** | 2.4 (0.9, 6.5] |

| Black | 1.2 [0.9, 1.7] | 1.3 [0.7, 2.2] | 1.5 [0.6, 4.0] |

| Other | 1.4 [0.9, 2.2] | 1.6 [0.8, 3.6] | 0.9 [0.2, 4.2] |

| Age | |||

| 18–24 | — | — | — |

| 25–44 | 0.3 [0.2, 0.5]*** | 0.4 [0.2, 0.6]*** | 0.6 [0.2, 1.7] |

| 45–64 | 0.08 [0.06,0.14]*** | 0.3 [0.1, 0.4]*** | 1.0 [0.2, 4.1] |

| 65+ | 0.02 [0.01,0.04]*** | 0.6 [0.1, 3.1] | 0.9 [0.1, 7.6] |

| Education | |||

| More than HS | — | — | — |

| High School | 1.0 [0.8, 1.2] | 0.5 [0.4, 0.8]** | 1.6 [0.8, 3.3] |

| Less than HS | 0.6 [0.4, 0.8]** | 0.8 [0.5, 1.4] | 2.8 [1.3, 6.0]** |

| Income | |||

| $40k or higher | — | — | — |

| $20k to $39,999 | 0.7 [0.5, 0.9] | 2.2 [1.3, 3.7]** | 1.5 [0.5, 4.5] |

| Below $2 0k | 0.6 [0.4, 0.8]*** | 4.1 [2.2, 7.6]*** | 2.7 [1.0, 7.8] |

| Sexual identity | |||

| Heterosexual | — | — | — |

| Gay/Lesbian | 1.4 [0.8, 2.4] | 0.5 [0.2, 1.5] | 0.6 [0.1, 3.4] |

| Bisexual | 2.4 [1.2, 4.6] | 0.8 [0.4, 1.6] | 2.4 [0.6, 9.8] |

| Not sure/unknown | 1.8 [0.7, 4.6] | 3.3 [1.4, 8.1]** | 5.0 [0.6, 38.7] |

| Childhood adversities1 | 0.99 [0.97, 1.02] | 0.99 [0.95, 1.04] | 1.01 [0.94, 1.08] |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/cohabiting | — | — | — |

| Never married | 1.7 [1.2, 2.3]** | 2.2 [1.5, 3.2]*** | 1.1 [0.6, 2.1] |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 1.3 [1.0, 1.6] | 1.4 [0.8, 2.4] | 1.3 [0.6, 2.6] |

| Stressful life events2 | 1.2 [1.1, 1.2]*** | 1.2 [1.1, 1.3]*** | 1.2 [1.1, 1.4]*** |

| Type of prior SUD | |||

| Alcohol use disorder only | — | ||

| Alcohol and other SUD | 1.0 [0.8, 1.2] | — | — |

| Non-alcohol SUD only | 1.2 [0.6, 1.3] | 0.3 [0.1, 0.8] | |

| Tobacco use disorder (TUD) | |||

| No lifetime TUD | — | — | — |

| Prior TUD+ only | 0.3 [0.2, 0.4]*** | 0.4 [0.2, 0.7]** | 0.4 [0.1, 1.1] |

| Prior and/or past-year TUD+ | 1.2 [1.0, 1.5] | 1.2 [0.8, 1.7] | 0.8 [0.4, 1.6] |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | |||

| No lifetime PTSD | — | — | — |

| Prior PTSD+ only | 0.7 [0.4, 1.3] | 1.0 [0.5, 2.2] | 2.9 [0.7, 11.2] |

| Prior and/or past-year PTSD+ | 0.7 [0.5, 1.1] | 1.5 [0.9, 2.5] | 1.1 [0.5, 2.3] |

| Anxiety disorders3 | |||

| No lifetime anxiety disorder | — | — | — |

| Prior anxiety disorder only | 1.8 [1.2, 2.8]** | 0.5 [0.2, 1.1] | 0.4 [0.2, 1.3] |

| Prior and/or past-year anxiety+ | 1.2 [0.9, 1.6] | 0.8 [0.5, 1.2] | 0.8 [0.4, 1.8] |

| Mood disorders4 | |||

| No lifetime mood disorder | — | — | — |

| Prior mood disorder only | 0.9 [0.7, 1.2] | 0.9 [0.5, 1.5] | 0.7 [0.3, 1.5] |

| Prior and/or past-year mood+ | 1.0 [0.8, 1.4] | 1.6 [1.1, 2.5] | 1.1 [0.6, 2.2] |

| Drug treatment/help seeking | |||

| No | — | — | — |

| Yes | 0.5 [0.4, 0.6]*** | 1.3 [0.9, 1.8] | 0.6 [0.3, 1.1] |

Notes. AOR = odds ratio from multiple multinomial regression analyses adjusted for all correlates. 95% CI = confidence interval. PPY = prior-to-past-year. PY = past-year.

Actual counts of adverse childhood experiences (0–24).

Actual counts of stressful life events (0–16).

DSM-5 anxiety disorders consisted of agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic, social and/or specific phobias.

DSM-5 mood disorders consisted of bipolar, dysthymia, and/or major depressive disorder.

— = reference group.

p < .01

p < 0.001.

Among those with prior SUDs, approximately three-fourths had an individual prior SUD while about one-fourth had multiple prior SUDs. There was some overlap between any SUD and the other drug-specific SUD subgroups. More specifically, among those with any past-year persistent/recurrent SUD, approximately 89% also had a persistent/recurrent AUD, 16% had persistent/recurrent cannabis use disorder, and 7% had a persistent/recurrent prescription opioid use disorder. Notably, among those with a lifetime prescription opioid use disorder, only 13.9% also had a lifetime heroin use disorder. However, approximately half (50.4%) of respondents with a lifetime heroin use disorder also had a lifetime prescription opioid use disorder. Additional analyses indicated that the correlates remained similar when heroin use disorder was combined with prescription opioid use disorder to create an opioid use disorder variable: stressful life events remained highly significant (p < 0.001) while educational attainment was no longer associated with the probability of persistent/recurrent past-year opioid use disorder (results not shown). Finally, the multiple imputation analyses generally produced similar results with a few notable exceptions. First, bisexual identity was significantly associated with persistent/recurrent AUD based on the multiple imputation results (p < 0.01). Second, having multiple prior SUDs was significantly associated with persistent/recurrent prescription opioid use disorder based on the multiple imputation results (p < 0.01).

To help inform harm reduction strategies, we conducted additional analyses and changed our comparison group from abstinence to asymptomatic use when examining the persistent/recurrent SUD, alcohol use disorder, and cannabis use disorder regression models shown in Tables 2 and 3. In general, we found several key differences in correlates when asymptomatic use was the comparison group instead of abstinence (see Supplemental Table 2). For example, significant educational and income differences were no longer present when examining the correlates associated with the probability of past-year persistent/recurrent SUD relative to past-year asymptomatic use. In contrast, being male, Black, Hispanic, having a past-year and prior tobacco use disorder, having a past-year and prior mood disorder, having multiple SUDs, and having a lifetime history of substance use treatment/help seeking were all significantly associated with past-year persistent/recurrent SUD when asymptomatic use was the comparison group in these models. Similarly, there were nine differences for persistent/recurrent alcohol use disorder and seven differences in correlates of cannabis use disorder regression models when asymptomatic use was the comparison group instead of abstinence. Moreover, stressful life events remained significantly associated (p < 0.001) with persistent/recurrent SUD relative to asymptomatic use.

Table 4 presents estimates from essentially the same model presented in Table 2, with the exception being that the count of stressful life events was replaced by individual binary indicators of having specific stressful life events; the sample size was thus the same as reported in Table 2. After adjusting for other covariates, four specific stressful events (i.e., interpersonal work problems, victim of theft, family/friend assaulted, divorce or separation) were associated with greater odds of past-year persistent SUDs (p < 0.01). Interpersonal work problems and divorce or separation were also associated with significantly greater (p < 0.01) odds of past-year persistent AUD for those specifically with prior-to-past-year AUD (results not shown). We also considered exploratory analyses of these specific stressful life events for those individuals with the other two specific prior-to-past-year SUDs from Table 3; reduced sample sizes limited our power to detect the relationships of these indicators with the categorical remission outcome of interest, so our primary focus in reporting these results is on effect sizes. We found that neighbor problems and divorce or separation were associated with significantly greater odds of past-year persistent cannabis use disorder (p < 0.01); notable adjusted odds ratios (ranging from 1.5 to 1.6) were also found for interpersonal work problems, destruction of property, and being a victim of theft. These odds ratios would likely be significant at the 0.01 level with larger samples of those having a prior-to-past-year cannabis use disorder. One specific stressful event (serious financial debt) was associated with greater odds of past-year persistent prescription opioid use disorder (p < 0.01); neighbor problems and personal legal troubles also produced notable estimates of odds ratios, ranging from 2.4 to 2.9, each of which were only significant at the 0.05 level. In sum, we found that divorce or separation, interpersonal relationship problems (with neighbors or coworkers), and personal legal troubles tended to be fairly consistent predictors of persistent past-year SUD across the different substances. Multiple imputation analyses were conducted for these models to examine the potential impact of item-missing data on these results, and the results were similar to the complete case analyses.

Table 4.

Estimated Associations of Individual Stressful Events and Persistent/Recurrent Past-Year Substance Use Disorders (SUDs) among Adults with Any Prior-to-Past-Year SUDs

| Any Prior SUD | |

|---|---|

| Past-Year Persistent/Recurrent Substance Use Disorder vs. Abstinence (n=7,690 with any prior SUD) | |

| AOR [95% CI] | |

| Employment-related | |

| Changed job | 1.0 [0.8, 1.3] |

| Interpersonal work problems | 1.6 [1.2, 2.1]** |

| Fired from job | 1.0 [0.7, 1.4] |

| Unemployed | 1.3 [1.0, 1.9] |

| Family/home-related | |

| Divorce/separation | 1.8 [1.3, 2.4]*** |

| Neighbor problems | 1.2 [0.9, 1.7] |

| Family/friend death | 1.0 [0.8, 1.2] |

| Homeless | 0.7 [0.4, 1.1] |

| Moved or new roommate | 1.0 [0.9, 1.2] |

| Legal/crime-related | |

| Family/friend legal troubles | 1.1 [0.8, 1.4] |

| Family/friend assaulted | 1.8 [1.2, 2.6]** |

| Personal legal troubles | 2.0 [1.0, 4.2] |

| Personal property destroyed | 1.2 [0.8, 1.6] |

| Victim of theft | 1.5 [1.1, 1.9]** |

| Financial-related | |

| Serious financial debt | 1.3 [1.0, 1.7] |

| Bankruptcy | 0.8 [0.3, 1.8] |

Notes. AOR = odds ratio from multiple multinomial regression analysis adjusted for all of the same covariates from Table 2 (results not shown for other covariates). 95% CI = confidence interval.

p < .01

p < 0.001. Total sample size (n = 7,660) due to missing data.

Finally, when testing the interactions between the indicators of specific stressful life events in Table 4 and the other covariates, we found moderate evidence (p < 0.01 for AUD) of divorce or separation having a stronger association with the probability of recurrent / persistent AUD relative to abstinence for older age groups, specifically for those with any prior AUD. When attempting to fit models including these interactions to the smaller subgroups defined by prior cannabis or prescription opioid use disorders, we found that we did not have enough sample in the four age groups to reliably estimate these interactions involving stressful life events for each of our three generalized logit functions.

4. Discussion

This nationally representative investigation examined the prevalence and correlates associated with remission from any DSM-5 SUD (i.e., at least one SUD from an aggregation of all SUDs) as well as remission associated with three substance-specific disorders (i.e., alcohol, cannabis, and prescription opioids) among adults in the United States. The present study found that the overall estimated prevalence of any prior-to-past-year (prior) DSM-5 SUDs among adults in the United States was 25.4%. Among adults in the United States with any prior DSM-5 SUDs, the estimated prevalence of past-year abstinence was 14.2%. These findings are in line with a prior review concluding that the estimated percentage of adults in the United States in full remission from alcohol and other drug use disorders ranges from 5.3% to 15.3%, and these prevalence rates translate to a range of approximately 25 to 40 million adults in the United States (White, 2012).

The present study found that nearly half of adults (49.0%) with at least one prior DSM-5 SUD continued to experience DSM-5 SUD symptoms within the past 12 months. At least one national study found that approximately 40.1% of illicit drug users (i.e., sedatives, tranquilizers, opioids, amphetamines, cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, solvents/inhalants, heroin, and other drugs) with at least one DSM-IV drug abuse or dependence symptom continued to report symptomatic illicit drug use three years later (Compton et al., 2013). A second national study found that approximately 30.9% of individuals with DSM-IV non-alcohol drug use disorders reported persistence of a non-alcohol drug use disorder three years later (Fenton et al., 2012). The present study identified several correlates associated with persistent/recurrent symptomatic substance use and DSM-5 SUDs relative to past-year abstinence, including young adulthood (18–24 years of age), tobacco use disorder, higher personal income, higher educational attainment, never having been married, being divorced/separated/widowed, no lifetime substance use treatment, and stressful life events. The association between an aggregate count of recent stressful life events and a greater likelihood of persistent/recurrent SUDs was strong for an aggregation of the ten SUDs and each of the three substance-specific use disorders (alcohol, cannabis, and prescription opioids). These findings suggest the importance of managing and reducing stress in remission, especially for individuals particularly susceptible to relapse due to an inability to cope with stressful life events and negative affect, such as those in early remission (Pilowsky, Keyes, Geier, Grant, & Hasin, 2013; Witkiewitz, Lustyk, & Bowen, 2013), and perhaps beyond, even in sustained remission. Specific stressful life events, including divorce or separation, interpersonal relationship problems, and legal troubles were significantly associated with non-abstinent forms of remission and should be viewed as targets for all forms of recovery (harm reduction and abstinent-based). The past-year divorce and/or separation results are consistent with at least one prior study showing increased risk for relapse following divorce/separation among those in remission from alcohol dependence (Pilowsky et al., 2013). These findings highlight the importance of substance use treatment and other health professionals accounting for stress associated with divorce and separation when working with individuals with a history of SUD, especially among older adults.

Young adults with a prior SUD were significantly more likely than other adults to report recurrent/persistent SUD and symptomatic use (vs. abstinence) but not more likely to report asymptomatic use (vs. abstinence) relative to other adults. These findings suggest a need for treatment programs to take into account the extremely high rates of non-abstinent remission when treating young adults. The findings also provide additional evidence of smoking cessation improving SUD remission outcomes. There is a need for more research to identify the ideal time to initiate smoking cessation for those in SUD treatment (Baca & Yahne, 2009; Friend & Pagano, 2005a, 2005b; Kalman, Kahler, Garvey & Monti, 2006).

The substance-specific findings were consistent with prior research, because several correlates of remission were shared by at least two substances. However, there were also notable differences across substance classes, which suggests that processes of remission may be similar, but not identical, across substances (Lopez-Quintero et al., 2011). The high degree of overlap in findings between “any” SUD (i.e., an aggregation of the ten SUDs) and AUD has important implications for interpreting the results of the present study as well as other studies. In particular, the findings of such studies that focus on any SUD likely apply more directly to AUD when substance classes are aggregated and less directly to other SUDs such as cannabis, prescription opioids and other individual drug classes.

One notable finding that surfaced based on multiple imputation was that bisexual identity was significantly associated with persistent/recurrent AUD (p < 0.01). This finding suggests that imputation procedures may identify important findings related to small high-risk sub-populations that are missed when relying solely on complete case analysis. While past studies have shown that bisexual-identified adults in the United States have higher rates of SUDs and substance use treatment utilization relative to heterosexual-identified adults (Hughes, McCabe, Wilsnack, West, & Boyd, 2010; Kerridge et al., 2017; McCabe, West, Hughes, & Boyd, 2013), this is the first national study to show that bisexual-identified men and women who develop AUDs also have greater odds of persistent/recurrent AUD over time. Taken together, existing research indicates that bisexual-identified adults in the United States are more likely to develop SUDs, and the present study indicates that bisexual adults could be more likely to have persistent/recurrent AUD, relative to abstinent remission.

In terms of clinical implications, these findings underscore important associations between stressful life events and substance use, and reinforce the importance of acknowledging, anticipating, and addressing potentially stressful events in an adaptive manner during treatment and recovery from SUDs. From a historic perspective, Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) has long sought to provide a set of principles and a way of living through implementation of the twelve steps. This “spiritual program of action” (Alcoholics Anonymous World Service, 2001, p. 85) empowers individuals to respond constructively to situational and emotional stressors without relapsing to alcohol use. In turn, those in abstinence and recovery may be less likely to generate additional, self-inflicted stressful life events, such as job loss or severed relationships. More recently, mindfulness-based approaches have also been applied specifically to SUDs. For example, in apparent recognition of the relationship between stress and potential relapse to addictive behaviors, mindfulness-based relapse prevention (Bowen, Chawla, & Marlatt, 2010) combined secular forms of meditation and yoga as means of stress reduction (Kabat-Zinn, 1990), with cognitive-based approaches to relapse prevention (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985).

Clinical considerations related to stressful life events and substance use may reach far beyond the realms of traditional SUD treatment and mutual help group involvement. Given that 1) the majority of individuals who qualify for SUD treatment never receive it, 2) over time, those with a prior SUD may move in and out of identified categories of substance use and remission, and 3) stress represents a significant risk factor for substance use in this population, it follows that clinical responses need to expand accordingly. Consistent with public health and harm-reduction strategies, increased emphasis has been placed on various forms of prevention, screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) for substance use across the lifespan, in a variety of settings, including primary care (SAMHSA, 2017; Strobbe, 2014). SBIRT is a comprehensive, integrated public health approach to the delivery of early intervention and treatment services for people with SUD as well as those who are at risk for developing SUD (SAMHSA, 2017). This approach, coupled with an awareness of the role of stressful life events, could help shape clinical practice and influence patient outcomes in response to recognized vulnerabilities such as divorce, especially among older adults.

The present study has several strengths that build upon past national epidemiological research on remission from SUDs (Dawson et al., 2005; Moss et al., 2010; White, 2012). First, this investigation analyzed data from a nationally representative sample, which allowed us to generalize our findings to the civilian noninstitutionalized adult population residing in the United States. Second, most samples of those with prior SUDs were large enough to examine multinomial logistic regression models of past-year remission status including several key covariates (e.g., stressful life events). Third, the present study focused on both aggregate SUDs and substance-specific SUDs involving the most prevalent substance-specific SUDs (i.e., alcohol, cannabis, and prescription opioids). Finally, inclusion of DSM-5 criteria allowed for examination of clinically meaningful categories of past-year remission status based on substance use and DSM-5 symptomology, including abstinent remission, asymptomatic use, partial remission, and persistent/recurrent DSM-5 SUD.

This study also had some limitations that should be taken into account when considering implications of the findings. First, this study likely underestimated the prevalence of SUDs because small but high-risk groups of adults were not included, such as those who are incarcerated (Compton, Dawson, Duffy, & Grant, 2010). Second, given the cross-sectional data, causal inferences were not possible. In particular, it remains unclear, based on these data, whether individuals 1) used substances in response to stressful life events, 2) experienced stressful life events as a consequence of substance use, or 3) both. There was overlap between some of the individual stressful life events and SUD criteria (e.g., social impairment), and longitudinal data and more detailed questions are needed to further elucidate the temporal ordering of the associations between remission and stress. In addition, we could not assess the severity of individual stressful life events or adverse childhood events, nor the potential range of responses to stressful life events or adverse childhood events both before and after the development of a SUD, as well as remission from SUD (in the case of stressful life events). Third, remission status in the present study was defined for a 12-month period based on DSM-5 criteria, and experts have encouraged future research with longer term remission periods such as five years (DuPont, Compton, & McLellan, 2015). Fourth, the present study did not fully account for several factors contributing to substance use and remission from SUD (e.g., genetics). Finally, small samples sizes prevented a closer examination of some drug classes (e.g., heroin use disorder), and future work is needed with larger samples of individuals with specific SUDs to examine the prevalence and correlates associated with remission from these drug classes.

In conclusion, more than one in every four adults in the United States has met criteria for a prior-to-past-year DSM-5 SUD. Among U.S. adults who met criteria for any prior DSM-5 SUD, only 14.2% maintained past-year abstinence from any substance use, while 38.1% continued to meet criteria for at least one DSM-5 SUD. Young adulthood, higher educational attainment, higher personal income, never having been married, lack of lifetime substance use treatment, being divorced/separated/widowed, and stressful life events were all significantly associated with greater odds of past-year persistent/recurrent SUDs, relative to abstinence. In addition, remission from a prior tobacco use disorder decreased the probability of past-year persistent/recurrent SUD, relative to abstinence. Stressful life events were the only common correlate across the aggregation of all SUDs and each substance-specific SUD. The main finding that most people who remit from a DSM-5 SUD are either using substances or symptomatic has important implications for screening, prevention and treatment. There is a need to increase awareness about these findings since more patients with SUDs will likely be seen in primary care settings as a result of health care reforms.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

One-fourth of U.S. adults had a prior-to-past-year DSM-5 substance use disorder (SUD). One in every 7 adults with a prior SUD reported past-year abstinence from substances. Nearly half of adults with a prior SUD reported past-year symptomatic substance use. Stressful life events was only common correlate for recurrent SUD across drug classes. Differences were found for specific stressful life events between drug classes.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health [R01AA025684, R01CA212517, R01DA043696, R01DA036541 and R01DA031160] from the National Cancer Institute, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health. The sponsors had no additional role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. There was no editorial direction or censorship from the sponsors. The authors would like to thank the respondents for their participation in the study and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism for providing access to these data. The authors would also like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers, editorial staff and Ms. Kara Dickinson for their feedback and help with earlier versions of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of Interest: None.

Contributor Information

Sean Esteban McCabe, University of Michigan Center for the Study of Drugs, Alcohol, Smoking and Health, School of Nursing, and Institute for Research on Women and Gender 426 N. Ingalls St. Ann Arbor, MI, 48109

Brady T. West, University of Michigan Institute for Social Research, Survey Research Center P.O. Box 1248 Ann Arbor, MI 48106

Stephen Strobbe, University of Michigan Center for the Study of Drugs, Alcohol, Smoking and Health, School of Nursing, and Department of Psychiatry 426 N. Ingalls St. Ann Arbor, MI, 48109

Carol J. Boyd, University of Michigan Center for the Study of Drugs, Alcohol, Smoking and Health, School of Nursing, Department of Psychiatry, and Institute for Research on Women and Gender 426 N. Ingalls St. Ann Arbor, MI, 48109

References

- Alcoholics Anonymous World Service. (2001). Alcoholics Anonymous: The story of how thousands of men and women have recovered from alcoholism (4th ed.). New York: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Baca CT, & Yahne CE (2009). Smoking cessation during substance abuse treatment: what you need to know. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 36, 205–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L, Hondelsman L, Foote J, & Lovejoy M (1994). Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151, 1132–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Alderson O, Ogburn E, Grant BF, Nunes EV, Hatzenbuehler ML, & Hasin DS (2007). Changes in the prevalence of non-medical prescription drug use and drug use disorders in the United States: 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 90, 252–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Rafful C, Wall MM, Ridenour TA, Wang S, & Kendler KS (2014). Towards a comprehensive developmental model of cannabis use disorders. Addiction, 109, 284–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Secades-Villa R, García-Rodríguez O, Labrador-Mendez M, Wang S, & Schwartz RP (2013). Probability and predictors of remission from life-time prescription drug use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47, 42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen S, Chawla N, & Marlatt GA (2010). Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for addictive behaviors: A clinician’s guide. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Calabria B, Degenhardt L, Briegleb C, Vos T, Hall W, Lynskey M, Callaghan B, Rana U, & McLaren J (2010). Systematic review of prospective studies investigating “remission” from amphetamine, cannabis, cocaine or opioid dependence. Addictive Behaviors, 35, 741–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Dawson DA, Conway KP, Brodsky M, & Grant BF (2013). Transitions in illicit drug use status over 3 years: A prospective analysis of a general population sample. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 660–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Dawson D, Duffy SQ, & Grant BF (2010). The effect of inmate populations on estimates of DSM-IV alcohol and drug use disorders in the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 473–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, & Grant BF (2007). Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 566–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, & Grant BF (2007). Rates and correlates of relapse among individuals in remission from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: A 3-year follow-up. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 31, 2036–2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Huang B, & Ruan WJ (2005). Recovery from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: United States 2001–2002. Addiction, 100, 281–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPont RL, Compton WM, & McLellan AT (2015). Five-year recovery: a new standard for assessing effectiveness of substance use disorder treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 58, 1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton MC, Keyes K, Geier T, Greenstein E, Skodol A, Krueger B, Grant BF, & Hasin DS (2012). Psychiatric comorbidity and the persistence of drug use disorders in the United States. Addiction, 107, 599–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friend KB, & Pagano ME (2005a). Smoking cessation and alcohol consumption in individuals in treatment for alcohol use disorders. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 24, 61–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friend KB, & Pagano ME (2005b). Changes in cigarette consumption and drinking outcomes: Findings from Project MATCH. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 29, 221–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Chu A, Sigman R, Amsbary M, Kali J, Sugawara Y, Jiao R, Ren W, & Goldstein R (2015b). National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III): Source and Accuracy Statement.

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, Pickering RP, Ruan J, Smith SM, Huang B, & Hasin DS (2015a). Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry, 72, 757–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Smith SM, Jung J, Zhang H, Chou SP, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Huang B, Saha TD, Aivadyan C, Greenstein E, & Hasin DS (2015c). The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-5 (AUDADIS-5): reliability of substance use and psychiatric disorder modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 148, 27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, Smith SM, Pickering RP, Huang B, & Hasin DS (2016). Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. JAMA Psychiatry, 73, 39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Greenstein E, Aivadyan C, Stohl M, Aharonovich E, Saha T, Goldstein R, Nunes EV, Jung J, Zhang H, & Grant BF (2015a). The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-5 (AUDADIS-5): procedural validity of substance use disorders modules through clinical re-appraisal in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 148, 40–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, O’Brien CP, Auriacombe M, Borges G, Bucholz K, Budney A, Compton WM, Crowley T, Ling W, Petry N, Schuckit M, & Grant BF (2013). DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders: recommendations and rationale. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 834–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Shmulewitz D, Stohl M, Greenstein E, Aivadyan C, Morita K, Saha T, Aharonovich E, Jung J, Zhang H, Nunes EV, & Grant BF (2015b). Procedural validity of the AUDADIS-5 depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder modules: substance abusers and others in the general population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 152, 246–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, McCabe SE, Wilsnack SC, West BT, & Boyd CJ (2010). Victimization and substance use disorders in a national sample of heterosexual and sexual minority women and men. Addiction, 105, 2130–2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York, NY: Delacorte Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kalman D, Kahler CW, Garvey AJ, & Monti PM (2006). High-dose nicotine patch for smokers with a history of alcohol dependence: 36-week outcomes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 30, 213–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerridge BT, Pickering RP, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Chou SP, Zhang H, Jung J, & Hasin DS (2017). Prevalence, sociodemographic correlates and DSM-5 substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders among sexual minorities in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 170, 82–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Quintero C, Hasin DS, de Los Cobos JP, Pines A, Wang S, Grant BF, & Blanco C (2011). Probability and predictors of remission from lifetime nicotine, alcohol, cannabis or cocaine dependence: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Addiction, 106, 657–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, & Gordon JR (1985). Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Cranford JA, & Boyd CJ (2016). Stressful events and other predictors of remission from drug dependence in the United States: Longitudinal results from a national survey. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 71, 41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Cranford JA, & West BT (2008). Trends in prescription drug abuse and dependence, co-occurrence with other substance use disorders, and treatment utilization: results from two national surveys. Addictive Behaviors, 33, 1297–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, West BT, Hughes TL, & Boyd CJ (2013). Sexual orientation and substance abuse treatment utilization in the United States: Results from a national survey. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 44, 4–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Conron KJ, Koenen KC, & Gilman SE (2010). Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: a test of the stress-sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychological Medicine, 40, 1647–1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss HB, Chen CM, & Yi HE (2010). Prospective follow-up of empirically derived alcohol dependence subtypes in Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC): recovery status, alcohol use disorders and diagnostic, alcohol consumption behavior, health status, and treatment seeking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 34, 1073–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers B, McLaughlin KA, Wang S, Blanco C, & Stein DJ (2014). Associations between childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and past-year drug use disorders in the National Epidemiological Study of Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28, 1117–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilowsky DJ, Keyes KM, Geier TJ, Grant BF, & Hasin DS (2013). Stressful life events and relapse among formerly alcohol dependent adults. Social Work in Mental Health, 11(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, Van Hoewyk J, & Solenberger P (2001). A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Survey Methodolology, 27, 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Smith SM, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Dawson DA, Huang B, Stinson FS, & Grant BF (2008). The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): Reliability of new psychiatric diagnostic modules and risk factors in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 92, 27–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA (1979). Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: the Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 41, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Strobbe S (2014). Prevention and screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for substance use in primary care. Primary Care Clinics in Office Practice, 41, 185–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2017). About Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT). Available online at https://www.samhsa.gov/sbirt/about

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2006). Trends in Substance Abuse Treatment Admissions: 1993 and 2003. The DASIS Report. Office of Applied Studies. Available online at http://oas.samhsa.gov/2k6/TXtrends/TXtrends.cfm.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2016). Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 2004–2014. National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services BHSIS Series S-84, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 16–4986. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Lustyk MK, & Bowen S (2013). Retraining the addicted brain: a review of hypothesized neurobiological mechanisms of mindfulness-based relapse prevention. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27, 351–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White WL (2012). Recovery/Remission from substance use disorders: An analysis of reported outcomes in 415 scientific reports, 1868–2011. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disability. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt GE (1985). The sexual abuse of Afro-American and White American women in childhood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 9, 507–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.