Abstract

ATP‐sensitive potassium channels (KATP) channels are widely distributed in various tissues, including pancreatic beta cells, muscle tissue and brain tissue. KATP channels play an important role in cardioprotection in physiological/pathological situations. KATP channels are inhibited by an increase in the intracellular ATP concentration and are stimulated by an increase in the intracellular MgADP concentration. Activation of KATP channels decreases ischaemia/reperfusion injury, protects cardiomyocytes from heart failure, and reduces the occurrence of arrhythmias. KATP channels are involved in various signalling pathways, and their participation in protective processes is regulated by endogenous signalling molecules, such as nitric oxide and hydrogen sulphide. KATP channels may act as a new drug target to fight against cardiovascular disease in the development of related drugs in the future. This review highlights the potential mechanisms correlated with the protective role of KATP channels and their therapeutic value in cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords: cardiomyocytes, cardiovascular diseases, hydrogen sulphide, KATP channels, nitric oxide

1. INTRODUCTION

Arrhythmia is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity in cardiovascular diseases. Several ion channels in cardiomyocytes shape action potentials, trigger electrophysiological activities, and excitation‐contraction coupling (ECC), and finally, induce cardiac contraction and blood pumping within the circulatory system. Abnormal ion channels may affect cardiac function.

The ATP‐sensitive potassium (KATP) channel was first identified by Noma in cardiomyocytes treated with hypoxia using the patch clamp technique in 1983.1 KATP channels are characterized by channel inhibition because of an increase in the intracellular ATP concentration and stimulation because of an increase in the intracellular MgADP concentration.2, 3, 4 Cumulative evidence has indicated that KATP channels, which are ATP‐sensitive potassium channels, are widely distributed in various tissues, including pancreatic beta cells, muscle tissue, and brain tissue, and play an important role in cardioprotection in physiological and/or pathological states. Particularly, under pathophysiological conditions, KATP channels play a critical protective role by regulating cardiac repolarization. Activation of KATP channels decreases ischaemia/reperfusion injury, protects cardiomyocytes during heart failure, and reduces the occurrence of arrhythmias.

KATP channels couple the cellular metabolic state to the membrane potential. KATP channels play a critical role in various cellular functions, including hormone secretion and regulation of muscle excitability. KATP channels are also the target of endogenous vasoactive substances, such as nitric oxide (NO), reactive oxygen species (ROS), and hydrogen sulphide (H2S).5, 6 The protective mechanisms of KATP channels involve various signalling pathways. KATP channels may act as a new drug target to fight against cardiovascular disease in the development of drugs in the future. This review highlights a potential mechanism correlated with the protective role of KATP channels and their therapeutic value in cardiovascular diseases.

2. PROPERTIES OF KATP CHANNELS

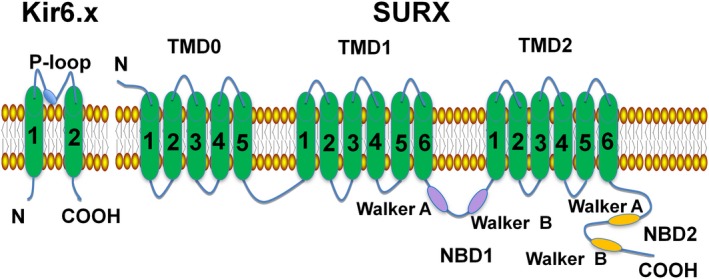

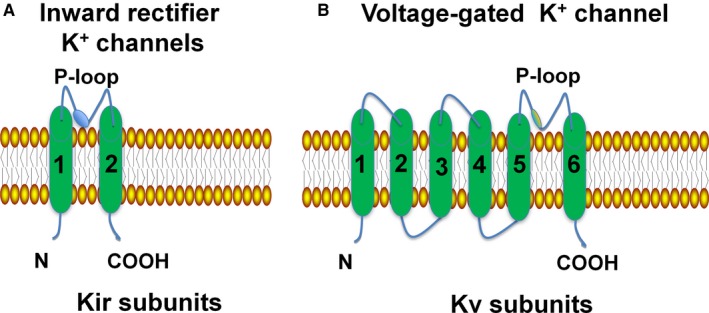

Many K+ channels are regulated by voltage and/or Ca2+ and are named Kv or KCa channels respectively.7, 8, 9 A group of K+ channels that is not regulated in this manner is the inward rectifier K+ channel (Kir channels). KATP channels are composed of four Kir channel subunits, Kir6.x (Kir6.1 and Kir6.2 are encoded by KCNJ8 and KCNJ11, respectively), and four sulphonylurea receptors, SUR (SUR1 and SUR2, with two splice variants: SUR2A and SUR2B, which are encoded by ABCC8 and ABCC9, respectively), whose subunit composition exhibits tissue specificity10, 11 (see Table 1). SUR has three domains that include TMD0, TMD1, and TMD2 helices. TMD1‐TMD2 and the C‐terminus contain nucleotide‐binding domains (NBD1 and NBD2)12, 13 (see Figure 1). The Kir subunit contains two transmembrane regions, a pore‐forming loop and cytosolic NH2 and COOH termini, whereas the Kv (voltage‐gated K+) channel subunit possesses six transmembrane regions, which include an ion conduction pore and voltage‐sensor domains14 (see Figure 2).

Table 1.

Subunit genes of KATP channels

| Isoforms | Gene | Chromosome |

|---|---|---|

| Kir6.2 | KCNJ11 | 11p15.1 |

| Kir6.1 | KCNJ8 | 12p11.23 |

| SUR1 | ABCC8 | 11p15.1 |

| SUR2 | ABCC9 | 12p12.1 |

KCNJ11: potassium inwardly rectifying channel, subfamily J, Member 11; KCNJ8: potassium inwardly rectifying channel, subfamily J, Member 8; ABCC8: ATP‐binding cassette, subfamily C, member 8; ABCC9: ATP‐binding cassette, subfamily C, member 9.

Figure 1.

Schematic structure of an ATP‐sensitive potassium channel. The KATP channel consists of Kir6.x (Kir6.2 and Kir6.1) and the regulatory subunits of SURx (SUR1, SUR2A, and SUR2B). The Kir6.x subunit has two transmembrane regions with intracellular NH 2 and COOH termini. The SURx subunit has 17 transmembrane regions, which include three domains: TMD0, TMD1, TMD2. SURx has two conserved intracellular nucleotide binding domains (NBDs). NBD1 is located between TMD1 and TMD2, whereas NBD2 exists in the COOH terminal of TMD2

Figure 2.

Structure of the Kir channel and Kv channel. SarcKATP channels are composed of eight proteins, which include four members of the inward rectifier K+ channel family Kir6.x, and four sulfonylurea receptors. The Kir subunit contains two transmembrane regions, a pore‐forming loop and cytosolic NH 2 and COOH termini, whereas the Kv channel subunit possesses six transmembrane regions, which include two functionally and independent domains: an ion conduction pore, and voltage‐sensor domains. Kir channel: inwardly rectifying K+ channel; Kv channel: voltage‐gated K+ channel; sarcKATP channel: sarcolemmal ATP‐sensitive potassium channel

Kir6.2/SUR2A is present in ventricular muscle cells, and Kir6.1/SUR2B is present in smooth muscle cells. The Kir6.2 and SUR1 subunits are present in pancreatic beta cells and neurons of the central nervous system15 (see Table 2). The Kir6.2 subunit has more intrinsic sensitivity to cellular metabolic disorders than the Kir6.1 subunit.16 In addition, the composition of the mitochondrial KATP (mitoKATP) channels is still unclear, although some literature suggests that Kir6.1 may be a functionally important part of mitoKATP channels in native heart cells.17

Table 2.

Diverse properties of KATP channels in cardiovascular tissue

| Tissue | Conductance (pS) | Subunit composition |

|---|---|---|

| Atrium | 52‐85 | Kir6.2/SUR1/SUR2A |

| Ventricle | 75‐85 | Kir6.2/SUR2A |

| Conduction System | 52‐60 | Kir6.2/Kir6.1/SUR2B |

| Mitochondria | 15‐100 | Kir1.1/SUR2A |

3. CARDIAC DISEASES

The opening and closing of KATP channels are regulated by various signalling molecules, including membrane phosphoinositides, the intracellular ATP concentration, and MgADP.18 Small signalling molecules, such as NO, H2S, and ROS, also play critical roles in protecting the cardiovascular system by regulating KATP channels.5, 6 H2S is endogenously generated from cysteine metabolism. Zhao et al6 reported that H2S directly increased KATP channel currents and hyperpolarized membrane and relaxed rat aortic tissues in vitro in a KATP channel‐dependent manner. These results demonstrated that H2S is an important endogenous vasoactive factor and a gaseous opener of KATP channels in vascular smooth muscle cells, but their mechanisms of action remain unclear. Zhang et al5 found that NO, a gaseous messenger known to be cytoprotective, increased the activity of KATP channels. These changes were reversed in the presence of inhibitors that were selective for PKG, ERK, calmodulin, or genetic ablation of CaMKIIδ, the predominant cardiac CaMKII isoform. These experimental results indicate that NO modulates KATP channels via a novel PKG‐ERK‐calmodulin‐CaMKIIδ signalling pathway.5

3.1. Cardiomyopathy

The opening of KATP channels protects cardiac muscle cells against hyperglycaemia‐induced damage and inflammation by inhibiting the ROS‐activated TLR4‐necroptosis pathway, which may be an important underlying mechanism of ROS in diabetic cardiomyopathy. These results indicated the cardio‐protective effects again injury induced by ROS in a KATP channels‐dependent manner.19

Some binding sites in KATP channels combine with signalling molecules to regulate the activity of KATP channels. Burton et al20 found that cardiac KATP channels were regulated by heme, and the cytoplasmic heme‐binding CXXHX16H motif on the SUR subunit of the channel was shown to include Cys628 and His648, which are important for heme binding. These results supported the hypothesis that there are mechanisms of heme‐dependent regulation across other ion channels.

Activation of α1‐adrenoceptors by pretreatment with phenylephrine can up‐regulate SUR2B/Kir6.2 to participate in cardio‐protection in H9C2 cells.21 This study showed that the up‐regulation of SUR2B/Kir6.2 might have a different physiological consequence from the up‐regulation of SUR2A/Kir6.2. This is the first explanation for the possible physiological role of SUR2B in a cardiac phenotype.

Syntaxin‐1A interacts with SUR2A to inhibit KATP channels, and PIP2 is known to bind the Kir6.2 subunit to open KATP channels. By contrast, it is interesting that PIP2 affects KATP channels by dynamically modulating Syn‐1A mobility from Syn‐1A clusters, resulting in the availability of Syn‐1A to inhibit KATP channels on the plasma membrane. This differential effect is related to the concentration of PIP2. 22

Evidence demonstrates that stretch‐induced KATP channel activity is controlled by MgATPase activity. These results may explain how KATP channel activity might respond rapidly to changes in the cardiac workload in a healthy heart and in a pathological state.23 In addition, phosphorylating NBD1 of SUR2B also exposes the MgATP binding site, thus disrupting the interaction of the NBD core with the N‐terminal tail and, in turn, activating KATP channels.24

3.2. Cardiac arrhythmias

Cardiac KATP channels have emerged as crucial controllers of heart failure and ischaemia‐related cardiac arrhythmias and have been suggested to be responsible for cardioprotection by decreasing repolarization dispersion and promoting action potential shortening.25, 26, 27

In cardiomyocytes, the ability of the mitochondrial network, which restores energy production and limits necrotic and apoptotic cell death, is a key determinant of survival after ischaemia‐reperfusion (IR). Mitochondrial function is a major factor in arrhythmogenesis during IR. Mitochondrial uncoupling can alter cellular electrical excitability and increase the propensity for reentry through opening of sarcolemmal KATP channels. Mitochondrial inner membrane potential (ΔΨm) is an essential component in the process of energy storage. ΔΨm instability or oscillation induced by ROS led to cardiac arrhythmia. This mechanism is necessary to increase the dispersion of refractoriness, slow the conduction velocity, and create a regional excitation block.28

Recent data have shown that mutations of KATP channels in myocardial cells can directly result in arrhythmias. The E23K variant of KCNJ11, identified in patients with type 2 diabetes,29 results in the frequent opening of KATP channels, which is associated with a greater left ventricular size with hypertension.30 These mutations, in turn, increases the occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias (VA) in dilated cardiomyopathy patients. Moreover, a KCNJ8 mutation was also found to be associated with atrial fibrillation (AF), and KATP channel currents were found to be decreased during chronic human AF.31

Feng et al32 reported that by over‐expressing the E23K variant, ventricular electrophysiological instability was increased when impaired by acute ischaemia. However, low‐doses of diazoxide, a KATP channel opener, improved hypoglycaemia‐related complications in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), resulting in rapid and heterogeneous APD shortening to promote reentrant ventricular tachyarrhythmias during ischaemia.33

3.3. Mutations in human disease

Patients with Cantu syndrome, which is caused by gain‐of‐function (GOF) mutations in genes encoding Kir6.1 and SUR2, have enlarged hearts with an increased ejection fraction and increased contractility. Mice with cardiac‐specific Kir6.1 GOF subunit expression show left ventricular dilation and increased basal L‐type Ca2+ currents, which results in phosphorylation of the pore‐forming α1 subunit of the cardiac voltage‐gated calcium channel Cav1.2 at Ser1928 relative to that in WT mice treated with isoproterenol.34 This result suggests that increasing protein kinase activity may act as a potential connection between increased KATP current and cardioprotection.

4. DRUG THERAPY AND PERSPECTIVE

KATP channels, a major drug target for the treatment of T2DM, are crucial in the regulation of heart injury and vascular smooth muscle tone. KATP channels are also important since the therapeutic agents that target KATP channels can also treat cardiovascular diseases. New effects correlated with KATP channels have recently been identified that were previously undetected. For example, the volatile anaesthetic isoflurane preserves the normalization of human KATP channel activity in human arteries exposed to oxidative stress caused by high glucose.35 Isoquercitrin induces vasodilation in resistance arteries, an effect that is mediated by the opening of KATP channels and endothelial NO production.36

Treatment with one type of fatty acid, EPA, in the early phase of myocardial infarction significantly reduces cardiac mRNA and protein expression of Kir6.2 and increases the SUR2B subunit. These findings indicate that EPA may suppress acute phase fatal VA and may have an inhibitory effect on ischaemia‐induced ventricular fibrillation in vivo, which may be mediated by an enhancement of ischaemia‐induced monophasic action potential shortening.37

Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, metabolites of arachidonic acid, are involved in the activation of PI3Kα and opening of KATP channels, which prevent Ca2+ overload and maintain mitochondrial function.38 Isosteviol sodium may increase the activation rate of sarcKATP channels induced by pinacidil and potentiate the diazoxide‐elicited oxidation of flavoproteins in mitochondria.39

The new antihypertensive drug iptakalim activates KATP channels in the endothelial cells of resistance blood vessels, a mechanism that is dependent on ATP hydrolysis and specific ATP ligands. The functions of endothelial KATP channels in resistance blood vessels can be changed by the exposure to the high shear stress caused by hypertension.40

Sulfonylurea induces the release of insulin by inhibiting the KATP channels that are present in pancreatic beta cells. Under high glucose conditions, glucose promotes the synthesis of intracellular ATP, which blocks KATP channels and prevents K+ efflux, leading to membrane depolarization and the opening of Ca2+ channels, allowing an influx of calcium and release of insulin.41, 42 Although efforts to reduce cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes mellitus should focus on improving glycaemic control, there is controversy as to whether the use of sulfonylurea increases the susceptibility of the myocardium to ischaemic insult, in light of the functional mechanisms of sulfonylurea drugs, which act through inhibition of the KATP channels present in both pancreatic beta cells and cardiomyocytes.25, 26, 27, 43, 44 Cardiac KATP channels inhibited by sulfonylurea drugs may be harmful to the ischaemic myocardium because of a disturbed KATP channel dependent response in the ischaemic precondition response.26 Further research is needed to develop a “selective” drug that targets pancreatic KATP channels without affecting cardiac channels.

It is clear that KATP channels play a significant role in the protection against cardiovascular diseases. In the literature, there is a considerable volume of information available regarding the mechanism of the protective role of KATP channels under different pathophysiological conditions, such as I/R injury, heart failure, cardiac arrhythmias, and atherosclerosis. However, studies characterizing KATP channels in targeted therapy of patients as well as the research and development of efficacious therapies are sparse, and further studies should investigate the potential mechanisms of KATP channels in cardiovascular diseases.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81370304, 81770441, 91639303); the Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Province (BK20151085); the Jiangsu Provincial Key Research and Development Program (BE2018611); the 10th Summit of the Six Top Talents of the Jiangsu Province (2016‐WSN‐185); the Medical Science and Technology Development Foundation of the Nanjing Department of Health(YKK15101, ZKX16048), the Jiangsu Province High Level Innovation and Entrepreneurship Talent Introduction Plan (2015‐395).

Ye P, Zhu Y‐R, Gu Y, Zhang D‐M, Chen S‐L. Functional protection against cardiac diseases depends on ATP‐sensitive potassium channels. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22:5801–5806. 10.1111/jcmm.13893

Peng Ye and Yan‐Rong Zhu contributed equally to this study.

Contributor Information

Dai‐Min Zhang , Email: daiminzh@126.com.

Shao‐Liang Chen, Email: chmengx@126.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Noma A. ATP‐regulated K+ channels in cardiac muscle. Nature. 1983;305:147‐148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Misler S, Falke LC, Gillis K, McDaniel ML. A metabolite‐regulated potassium channel in rat pancreatic B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:7119‐7123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kakei M, Noma A, Shibasaki T. Properties of adenosine‐triphosphate‐regulated potassium channels in guinea‐pig ventricular cells. J Physiol. 1985;363:441‐462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dunne MJ, Petersen OH. Intracellular ADP activates K+ channels that are inhibited by ATP in an insulin‐secreting cell line. FEBS Lett. 1986;208:59‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang DM, Chai Y, Erickson JR, Brown JH, Bers DM, Lin YF. Intracellular signaling mechanism responsible for modulation of sarcolemmal ATP‐sensitive potassium channels by nitric oxide in ventricular cardiomyocytes. J Physiol. 2014;592:971‐990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhao W, Zhang J, Lu Y, Wang R. The vasorelaxant effect of H2S as a novel endogenous gaseous KATP channel opener. EMBO J. 2001;20:6008‐6016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coetzee WA, Amarillo Y, Chiu J, et al. Molecular diversity of K channels. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;868:233‐285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhu Y, Ye P, Chen SL, Zhang DM. Functional regulation of large conductance Ca2+‐activated K+ channels in vascular diseases. Metabolism. 2018;83:75‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leonard CE, Hennessy S, Han X, Siscovick DS, Flory JH, Deo R. Pro‐ and antiarrhythmic actions of sulfonylureas: mechanistic and clinical evidence. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2017;28:561‐586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Clement JP, et al. A family of sulfonylurea receptors determines the pharmacological properties of ATP‐sensitive K+ channels. Neuron. 1996;16:1011‐1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li N, Wu JX, Ding D, Cheng J, Gao N, Chen L. Structure of a pancreatic ATP‐sensitive potassium channel. Cell. 2017; 168(1‐2):101‐110.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Linton KJ, Higgins CF. Structure and function of ABC transporters: the ATP switch provides flexible control. Pflügers Arch. 2007;453:555‐567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Martin GM, Yoshioka C, Rex EA, et al. Cryo‐EM structure of the ATP‐sensitive potassium channel illuminates mechanisms of assembly and gating. Elife. 2017; 6 pii: e24149 10.7554/elife.24149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee KPK, Chen J, MacKinnon R. Molecular structure of human KATP in complex with ATP and ADP. Elife. 2017; 6: pii:e32481 10.7554/elife. 32481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aguilar‐Bryan L, Clement JP 4th, Gonzalez G, Kunjilwar K, Babenko A, Bryan J. Toward understanding the assembly and structure of KATP channels. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:227‐245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li CG, Cui WY, Wang H. Sensitivity of KATP channels to cellular metabolic disorders and the underlying structural basis. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2016;37:134‐142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wojtovich AP, Urciuoli WR, Chatterjee S, Fisher AB, Nehrke K, Brookes PS. Kir6.2 is not the mitochondrial KATP channel but is required for cardioprotection by ischemic preconditioning. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;304:H1439‐H1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tinker A, Aziz Q, Thomas A. The role of ATP‐sensitive potassium channels in cellular function and protection in the cardiovascular system. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:12‐23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liang W, Chen M, Zheng D, et al. The opening of ATP‐Sensitive K+ channels protects H9c2 cardiac cells against the high glucose‐induced injury and inflammation by inhibiting the ROS‐TLR4‐necroptosis pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;41:1020‐1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Burton MJ, Kapetanaki SM, Chernova T, et al. A heme‐binding domain controls regulation of ATP‐dependent potassium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:3785‐3790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jovanović S, Ballantyne T, Du Q, Blagojević M, Jovanović A. Phenylephrine preconditioning in embryonic heart H9C2 cells is mediated by up‐regulation of SUR2B/Kir6.2: a first evidence for functional role of SUR2B in sarcolemmal KATP channels and cardioprotection. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2016;70: 23‐28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xie L, Liang T, Kang Y, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 4, 5‐biphosphate (PIP2) modulates syntaxin‐1A binding to sulfonylurea receptor 2A to regulate cardiac ATP‐sensitive potassium (KATP) channels. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;75:100‐110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fatehi M, Carter CC, Youssef N, Light PE. The mechano‐sensitivity of cardiac ATP‐sensitive potassium channels is mediated by intrinsic MgATPase activity. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2017;108:34‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. de Araujo ED, Alvarez CP, López‐Alonso JP, Sooklal CR, Stagljar M, Kanelis V. Phosphorylation‐dependent changes in nucleotide binding, conformation, and dynamics of the first nucleotide binding domain (NBD1) of the sulfonylurea receptor 2B (SUR2B). J Biol Chem. 2015;290:22699‐22714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Terzic A, Jahangir A, Kurachi Y. Cardiac ATP‐sensitive K channels: regulation by intracellular nucleotides and potassium opening drugs. Am J Physiol. 1995;38:C525‐C545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Engler RL, Yellon DM. Sulfonylurea KATP blockade in type II diabetes and preconditioning in cardiovascular disease: time for reconsideration. Circulation. 1996;94:2297‐2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brady PA, Terzic A. The sulfonylurea controversy: more questions from the heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:950‐956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Solhjoo S, O'Rourke B. Mitochondrial instability during regional ischemia‐reperfusion underlies arrhythmias in monolayers of cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;78:90‐99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xu M, Hu H, Deng D, Chen M, Xu Z, Wang Y. Prediabetes is associated with genetic variations in the Kir6.2 subunit (KCNJ11) of pancreatic ATP‐sensitive potassium channel gene: a case‐control study in youth Han Chinese population. J Diabetes. 2018;10:121‐129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Reyes S, Terzic A, Mahoney DW, Redfield MM, Rodeheffer RJ, Olson TM. KATP channel polymorphism is associated with left ventricular size in hypertensive individuals: a large‐scale community‐based study. Hum Genet. 2008;123:665‐667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yang HQ, Subbotina E, Ramasamy R, Coetzee WA. Cardiovascular KATP channels and advanced aging. Pathobiol Aging Age Relat Dis. 2016;6:32517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Feng Y, Liu J, Wang M, et al. The E23K variant of the Kir6.2 subunit of the ATP‐sensitive potassium channel increases susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmia in response to ischemia in rats. Int J Cardiol. 2017;232:192‐198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xie C, Hu J, Motloch LJ, Karam BS, Akar FG. The classically cardio‐protective agent diazoxide elicits arrhythmias in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1144‐1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Levin MD, Singh GK, Zhang HX, et al. KATP channel gain‐of‐function leads to increased myocardial L‐type Ca2+ current and contractility in Cantu syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:6773‐6778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kinoshita H, Matsuda N, Iranami H, et al. Isoflurane pretreatment preserves adenosine triphosphate‐sensitive K+ channel function in the human artery exposed to oxidative stress caused by high glucose levels. Anesth Analg. 2012;115:54‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gasparotto Junior A, Dos Reis Piornedo R, Assreuy J, Da Silva‐Santos JE. Nitric oxide and Kir6.1 potassium channel mediate isoquercitrin‐induced endothelium‐dependent and independent vasodilation in the mesenteric arterial bed of rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2016;788:328‐334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Moreno C, de la Cruz A, Valenzuela C. In‐depth study of the interaction, sensitivity, and gating modulation by PUFAs on K+ channels; interaction and new targets. Front Physiol 2016; 7:578. eCollection 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Batchu SN, Chaudhary KR, El‐Sikhry H, et al. Role of PI3Kα and sarcolemmal ATP‐sensitive potassium channels in epoxyeicosatrienoic acid mediated cardioprotection. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;53:43‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fan Z, Wen T, Chen Y, et al. Isosteviol sensitizes sarcKATP channels towards Pinacidil and potentiates mitochondrial uncoupling of diazoxide in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:6362812 10.1155/2016/6362812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang S, Cui W, Wang H. The new antihypertensive drug iptakalim activates ATP‐sensitive potassium channels in the endothelium of resistance blood vessels. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2015;36:1444‐1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Polonsky K. The beta‐cell in diabetes: from molecular genetics to clinical research. Diabetes. 1995;44:705‐717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cook D, Hales CN. Intracellular ATP directly blocks K channels in pancreatic B‐cells. Nature. 1984;311:271‐273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group (The DCCT Trial lists) . The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long‐term complications in insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1993;329: 977‐986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ashcroft FM, Ashcroft SJH. The sulphonylurea receptor. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1175:45‐59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]