Abstract

Purpose of Review:

Interventions that aim to alter child eating behaviors often focus on parents as a proximal influence. Yet, parents can be difficult to engage. Therefore, intervention recommendations are often not implemented as designed. The goal of this review is to highlight factors at multiple contextual levels that are important to consider when developing interventions to address child eating, due to their implications for overcoming parent engagement challenges.

Recent Findings:

Intervention studies suggest that parents are often the key to successfully changing child eating behaviors, and many interventions focus on feeding. Factors such as child eating phenotypes; parent stress; family system dynamics; and sociodemographic constraints have also been identified as shaping food parenting.

Summary

Challenges at multiple contextual levels can affect the likelihood of parent engagement. addressing factors at the child-, parent-, family- and broader social-contextual levels of influence is essential in order to promote best practices for parent-focused feeding interventions.

Keywords: Parenting, eating behavior, feeding, stress, intervention, implementation, engagement

Introduction

Behavioral interventions that seek to promote healthy child eating, diet, and weight outcomes often seek to engage parents, as they are a key agent of change particularly for young children [1, 2]. The nature of such interventions can vary, but usually include programs that seek to increase parent knowledge about healthy nutrition [3] and/or cooking skills [4] and work with parents (primarily mothers) to change their feeding practices. For example, approaches include promoting breastfeeding [5], delaying the start of solid foods [6], or using responsive feeding practices [7, 8] as well as encouraging regular family routines around mealtimes, sleep, and/or media use [9]. Some intervention approaches focus more directly on parents’ own weight management and nutrition [10] or use family-based obesity prevention strategies that seek to engage the whole family unit [11]. Common to most of these approaches are difficulties with parent engagement and intervention sustainability [12]; yet, the reasons for this are often poorly understood.

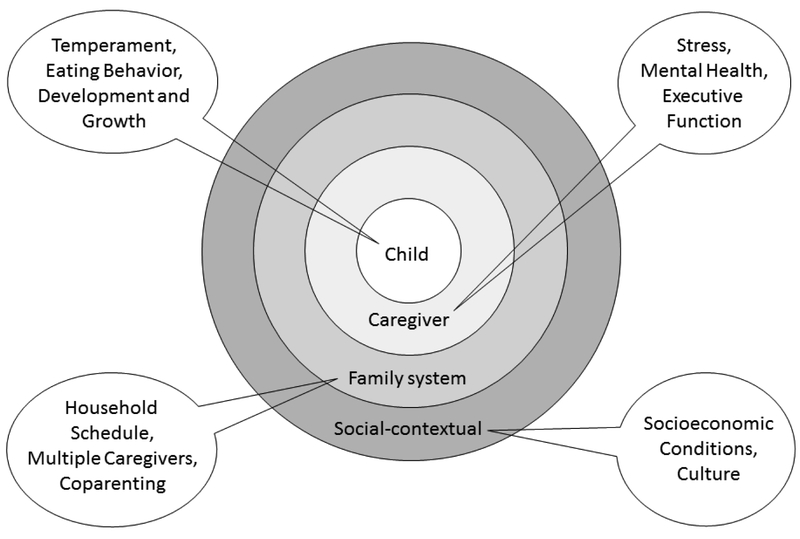

The goal of the current report is to highlight factors at the child, caregiver, family, and broader social-contextual levels (see Figure 1) that can shape parenting behaviors related to child feeding, or food parenting, and thus may be particularly important to the effects of behavioral interventions for families. We reviewed multiple databases (e.g., MEDLINE/PubMed, PSYCinfo) to identify relevant studies, prioritizing works published in the last five years (since 2013). We used a combination of search terms [e.g., (“intervention” OR “program”) AND (“child feeding” OR “child feeding practices” OR “parent feeding practices”) AND (“challenges” OR child temperament” OR “coparenting” OR “timing” OR “food insecurity” OR “maternal mental health” OR “maternal depression” OR “stress” OR “perfect parent pressure” OR “pressure” OR “cultural differences” OR “culture” OR “ethnicity”)]. Results were limited to studies with human subjects in the English language. Studies covered developmental periods from infancy to adolescence (ages 0-18 years), with the focus of this review on the infancy and early childhood (i.e., ages 0-5 years) to pre-adolescent periods (ages 6-13 years) as these ages are often targeted in parent-focused interventions. Additional studies were identified using a snowball approach by searching the reference lists of relevant review articles and research studies.

Figure 1.

Child, caregiver, family, and social-contextual factors to consider in feeding interventions

Child Factors

Individual differences between children can present different barriers and opportunities for food parenting, and informing parents on the nature of these differences may reduce any feeling of “blame” and empower parents to implement intervention recommendations. Caregiver feeding practices during infancy have been found to differ as a function of child temperament, for example studies have found that caregivers (mothers) endorsed using food to soothe distress when their infants were rated as having a “difficult” temperament [13, 14]. Similar associations between difficult child temperament and maternal feeding practices, such as using restrictive feeding practices or feeding obesogenic foods and drinks, have also been identified during the preschool years [15].

As well, child factors directly related to child eating are important to consider. For instance, children are known to differ in their appetitive drive, including both food “approach” behavior, such as enjoyment of food, and also their level of responsiveness to satiety, or fullness cues [16, 17] and “food avoidant” behavior, such as refusal to eat or “picky” eating behavior. Such eating behavior phenotypes [17] can drive how engaged children are with food and eating, and individual differences in these child behaviors may in turn shape caregivers’ feeding behavior. For example, children who enjoy eating and rarely show signs of satiation may be easier for a caregiver to feed, but may become distressed if they need to wait to eat, which could be challenging for a busy parent. In contrast, children who are reluctant eaters pose different caregiving demands. Caregivers may feel pressure to expend additional effort in these cases, such as preparing special foods so that the child will eat.

Children also differ in their taste preferences, with some showing more of a preference for sweet tastes during the early childhood years, than others [18]. Furthermore, and possibly shaped by such preferences, certain developmental periods are characterized by changes in what children choose (or demand) to eat or not eat. Specifically, toddlerhood is a period when “picky” eating behavior often emerges [19], and picky eating in young children is often reported as a source of stress by parents [20]. Picky eating at mealtimes may present barriers to parents who are seeking to have family dinners, for example, and result in family-level conflict. Recent work suggests that parent behavior may not be as strong of an influence on children’s picky eating behavior as previously believed [21], however, so this may be an area in which to work with parents to reassure them that some picky eating is developmentally normative and may be outgrown over time.

Finally, some children may have conditions such as developmental delays (e.g., autism spectrum disorders) that may make feeding difficult or chronic illnesses that require close management of food and eating (e.g., Type 1 Diabetes). Children who experience delays in growth (e.g., premature infants) may also require specialized feeding approaches, and feeding can be a source of anxiety for parents in such cases. Parents of children with developmental delays have been found to use more controlling feeding practices [22] and may also experience more mealtime challenges [23].

Thus, in the context of parent-focused interventions to address feeding practices and child eating behavior, it may be important to inform parents about individual child differences that may drive behavior in order to reinforce the perspective that children differ in their eating and other behaviors. Simply acknowledging and validating the perspectives that such differences exist (even between siblings in the same family) may be reassuring to parents. Individual differences (e.g., in genetic makeup, [24] or the drive to eat, [25, 26]) can also play a role in what intervention approaches may work best for which families. Empowering parents to work with these differences may be helpful in designing implementing optimal feeding strategies for families.

Caregiver Factors

Parents may not easily engage in intervention programming for additional reasons such as capacity for time management, stress, and individual factors. Parents often have limited time and may have difficulties managing household routines related to feeding and mealtimes, particularly if they lack organizational skills [27]. Caregivers who are under stress have been found to engage in more restrictive feeding practices with their preschool-aged children [28]. Moreover, greater work-life stress has been associated with provision of less healthful meals among parents of older children and adolescents [29]. In addition to general stressors, mental health issues such as depression can present challenges in child feeding. Mothers with depression, who have school-aged children, report less responsive feeding practices and less authority in feeding [30]. Maternal depression has also been associated with greater risk for poor infant feeding outcomes including shorter breastfeeding duration, more difficulties, and decreased self-efficacy [31].

An additional stressor that may influence caregiver feeding practices is the pressure to be a “perfect parent” [32, 33]. Although this has not yet been examined explicitly with regard to feeding, online social comparisons can negatively affect parenting and relationship outcomes, such as parental competence, coparenting relationship quality, and perceived social support [32]. Parents are often blamed for their child’s eating behavior or weight status [34], and many parents with children who have overweight have overweight themselves [35] and may feel stigmatized about their weight as well as their parenting [36]. Parents may also struggle with how to discuss weight with their child [37]. If parents do not feel heard by providers, or feel talked down to, this will likely create challenges in implementing feeding recommendations. Therefore, in the context of interventions focused on feeding and eating, it is important to consider parents’ beliefs and attitudes as well as goals regarding child feeding, weight stigma, and their own weight management and family history.

Family System Factors

Beyond the caregiver, challenges in the family system, meaning the members of the family who are directly or indirectly involved in the child’s care and/or who have a relationship with the caregiver (e.g., spouses; siblings; grandparents), may interfere with effective implementation of feeding recommendations. The timing of meals often depends on daily routines and is influenced by conflicts between work and school schedules and other activities of different family members [38, 39]. For example, shift work has been associated with poorer meal quality [40], and early school start times and/or afterschool activities for children (e.g., sports practices) can interfere with mealtimes [41, 42]. Management challenges and scheduling constraints make it difficult for parents to implement recommended changes.

Family challenges may also arise due to differences of opinion on feeding practices between caregiver and partner, which have been associated with conflict around feeding strategies during early childhood [43, 44]. Given that young children are often in the care of multiple adults who may endorse different feeding practices (e.g., daycare providers; relatives [39]), it is important to acknowledge that a single caregiver does not control the child’s entire feeding environment. Even if a child is not in the care of relatives, intergenerational influences are often present (for example, when a grandparent gives feeding advice to a new mother). Each of these family-level factors may challenge to a caregiver’s capacity to follow recommendations.

Given that many children are cared for by multiple caregivers; it may be helpful when possible to include co-parents and other family members in the intervention, as disagreements among family members can cause challenges. Of note, most interventions still focus on mothers [45] as they often remain responsible for child feeding [39, 46]. Yet, fathers are increasingly recognized as playing a key role [46, 44, 43] and are more involved in child care and household routines than ever before. Thus, interventions that focus only on mothers may be limited in their scope; interventions that address the broader family system, though complicated, will likely be more sustainable. Indeed, obesity prevention efforts targeting the family system and setting have shown promise [9, 47] and may be more cost-effective than other approaches [48].

Social-Contextual Factors

Social-contextual factors shape feeding practices at multiple levels and are critical to consider in any parent-focused behavioral intervention around feeding and eating. Socioeconomic conditions can drive many parenting decisions, including those around food and diet. Caregivers who are living in poverty or in under-resourced circumstances may face unique challenges to implementing recommended feeding practices. Food insecurity has been associated with unhealthier eating patterns and maternal feeding practices, such as restriction [49] or compensatory feeding [50]. A caregiver’s prior food insecurity may also influence feeding practices (i.e. less monitoring of sweets and snack foods) and make it difficult for caregivers to refuse children’s unhealthy food requests [51]. Food insecurity can also result in parents restricting their own intake in order to ensure their children have enough [52], which can lead to stress and health concerns for parents.

It is also vital to recognize that cultural and socio-demographic factors shape feeding practices. For example, cultural differences can drive parents’ views of foods that are considered healthful, harmful, or culturally preferred [53]. Cultural differences also influence what feeding practices are used across diverse cultural groups (e.g., food selection, portion size) and where advice is sought regarding child feeding [54, 55]. Furthermore, social-environmental factors that align with cultural differences can introduce barriers to following feeding recommendations. Parents living in under-resourced communities, which is often the experience of ethnic minority families within the United States (US), may experience difficulty accessing and preparing healthy foods, and instead rely on more easily-available convenience foods that tend to be higher in energy density and less healthy [53]. To promote intervention uptake, therefore, it may be helpful to reach out to key stakeholders figures from a parent’s community and even involve parents in the development of the intervention, if possible, in order to increase engagement [56]. Recent approaches that have used online social support networks (e.g., Facebook groups) [57, 58] or web-based, community-focused outreach efforts [59] have also shown promise in engaging low-income, under-resourced parents around feeding practices and other obesity prevention activities.

Finally, immigrant families represent a special population of interest that deserves attention. Given the immigrant “paradox” in many health domains [60], including feeding, diet and weight, such that longer residence in the US associates with higher risk for obesity [61] (although some studies in young children have had mixed findings [62, 63]), it is vital to understand how best to intervene with immigrant families. Feeding styles have been shown to differ between low-income Hispanic mothers born in the US vs. outside the US, for example [64], suggesting one possible pathway of influence. As well, families who have emigrated often face extreme levels of stress (e.g., deportation fears [65]) and isolation [62, 60] that can interfere with connecting to resources and/or implementing recommendations. Beyond addressing basic language barriers, therefore, when working with immigrant families it is essential to consider families’ views of food, eating, and roles in child feeding, and help address challenges to finding familiar, comforting foods and establishing feeding routines in a new country [66].

Conclusion

In summary, when advising caregivers around feeding, it is critical to keep in mind individual child differences such as temperament and eating behavior; the personal resources of the caregiver; the family system; and the larger social context in which the caregiver and child reside. Placing blame on the caregiver for not following recommendations in feeding interventions is likely to be counterproductive. Rather, considering the multiple levels of context in which caregivers operate when feeding children, and helping parents articulate and address potential barriers to following recommendations, may be a helpful strategy for implementation.

To be most effective, feeding interventions may first need to consider how to engage the under-resourced parents whose children are most at risk due to social-contextual challenges such as poverty. Furthermore, it is likely important for interventions to assess individual parent capacity to implement recommendations, and to work with the parent to reduce barriers to engagement. One way to engage parents may be through tailoring intervention strategies that address individual child or developmental factors that create feeding challenges. Ultimately, such strategies could result in intervention and prevention approaches that are effective, sustainable, and welcomed by families.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Alison L. Miller, Sara E. Miller, and Katy M. Clark declare they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

All reported studies/experiments with human or animal subjects performed by the authors have been previously published and complied with all applicable ethical standards (including the Helsinki declaration and its amendments, institutional/national research committee standards, and international/national/institutional guidelines).

References

- 1.Golan M, Crow S. Targeting Parents Exclusively in the Treatment of Childhood Obesity: Long-Term Results. Obesity Research. 2004;12(2):357–61. doi:doi:10.1038/oby.2004.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hingle MD, O'Connor TM, Dave JM, Baranowski T. Parental Involvement in Interventions to Improve Child Dietary Intake: A Systematic Review. Preventive Medicine. 2010;51(2):103–11. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howard KA, Tucker J, DeFrang R, Orth J, Wakefield S. Primary Care Obesity Prevention in 0-2 Year Olds Through Parent Nutritional Counseling: Evaluation of Child Behaviors and Parent Feeding Styles. Pediatrics. 2018;141(1 MeetingAbstract):591-. doi:10.1542/peds.141.1_MeetingAbstract.591. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robson SM, Stough CO, Stark LJ. The impact of a pilot cooking intervention for parent-child dyads on the consumption of foods prepared away from home. Appetite. 2016;99:177–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yan J, Liu L, Zhu Y, Huang G, Wang PP. The association between breastfeeding and childhood obesity: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1267. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huh SY, Rifas-Shiman SL, Taveras EM, Oken E, Gillman MW. Timing of Solid Food Introduction and Risk of Obesity in Preschool-Aged Children. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):e544–e51. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-0740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniels LA, Mallan KM, Nicholson JM, Battistutta D, Magarey A. Outcomes of an Early Feeding Practices Intervention to Prevent Childhood Obesity. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * 8.Savage JS, Hohman EE, Marini ME, Shelly A, Paul IM, Birch LL. INSIGHT responsive parenting intervention and infant feeding practices: randomized clinical trial. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2018;15(1):64. doi:10.1186/s12966-018-0700-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Intervention showing positive impact of parent feeding behavior during infancy on child weight outcomes.

- 9.Haines J, McDonald J, O’Brien A, Sherry B, Bottino CJ, Schmidt ME et al. Healthy habits, happy homes: Randomized trial to improve household routines for obesity prevention among preschool-aged children. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013;167(11):1072–9. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry DC, McMurray RG, Schwartz TA, Hall EG, Neal MN, Adatorwover R. A cluster randomized controlled trial for child and parent weight management: children and parents randomized to the intervention group have correlated changes in adiposity. BMC Obesity. 2017;4:39. doi:10.1186/s40608-017-0175-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * 11.Altman M, Wilfley DE. Evidence Update on the Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Children and Adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2015;44(4):521–37. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.963854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Review of evidence-based strategies for the treatment of overweight and obesity in children; highlights the importance of engaging families directly in treatment.

- 12.Niemeier BS, Hektner JM, Enger KB. Parent participation in weight-related health interventions for children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Preventive Medicine. 2012;55(1):3–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stifter CA, Anzman-Frasca S, Birch LL, Voegtline K. Parent use of food to soothe infant/toddler distress and child weight status. An exploratory study. Appetite. 2011;57(3):693–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McMeekin S, Jansen E, Mallan K, Nicholson J, Magarey A, Daniels L. Associations between infant temperament and early feeding practices. A cross-sectional study of Australian mother-infant dyads from the NOURISH randomised controlled trial. Appetite. 2013;60:239–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergmeier H, Skouteris H, Horwood S, Hooley M, Richardson B. Associations between child temperament, maternal feeding practices and child body mass index during the preschool years: a systematic review of the literature. Obesity Reviews. 2014;15(1):9–18. doi:doi:10.1111/obr.12066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wardle J, Guthrie CA, Sanderson S, Rapoport L. Development of the Children's Eating Behaviour Questionnaire. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines. 2001;42(7):963–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * 17.Kral TVE, Moore RH, Chittams J, Jones E, O'Malley L, Fisher JO. Identifying behavioral phenotypes for childhood obesity. Appetite. 2018;127:87–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Highlights the substantial individual differences in child appetitive traits and that not all children are equally susceptible to overeating of palatable foods, as well as implications for targeted interventions.

- 18.Ventura AK, Mennella JA. Innate and learned preferences for sweet taste during childhood. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care. 2011;14(4):379–84. doi:10.1097/MCO.0b013e328346df65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dovey TM, Staples PA, Gibson EL, Halford JCG. Food neophobia and ‘picky/fussy’ eating in children: A review. Appetite. 2008;50(2):181–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trofholz AC, Schulte AK, Berge JM. How parents describe picky eating and its impact on family meals: A qualitative analysis. Appetite. 2017;110:36–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lumeng JC, Miller AL, Appugliese D, Rosenblum K, Kaciroti N. Picky eating, pressuring feeding, and growth in toddlers. Appetite. 2018;123:299–305. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2017.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polfuss M, Simpson P, Neff Greenley R, Zhang L, Sawin KJ. Parental Feeding Behaviors and Weight-Related Concerns in Children With Special Needs. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2017;39(8):1070–93. doi:10.1177/0193945916687994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Must A, Curtin C, Hubbard K, Sikich L, Bedford J, Bandini L. Obesity Prevention for Children with Developmental Disabilities. Current Obesity Reports. 2014;3(2):156–70. doi:10.1007/s13679-014-0098-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belsky J, van IMH. Genetic differential susceptibility to the effects of parenting. Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;15:125–30. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bauer KW, Haines J, Miller AL, Rosenblum K, Appugliese DP, Lumeng JC et al. Maternal restrictive feeding and eating in the absence of hunger among toddlers: a cohort study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2017;14(1):172. doi:10.1186/s12966-017-0630-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsen J, Hermans R, Sleddens E, M E Engels R, Fisher J, S.P.J. Kremers S. How parental dietary behavior and food parenting practices affect children's dietary behavior: Interacting sources of influence? 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bauer KW, Weeks HM, Lumeng JC, Miller AL, Gearhardt AN. Maternal Executive Function and the Family Food Environment. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. Under Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swyden K, Sisson SB, Morris AS, Lora K, Weedn AE, Copeland KA et al. Association Between Maternal Stress, Work Status, Concern About Child Weight, and Restrictive Feeding Practices in Preschool Children. Maternal and child health journal. 2017;21(6):1349–57. doi:10.1007/s10995-016-2239-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bauer KW, Hearst MO, Escoto K, Berge JM, Neumark-Sztainer D. Parental employment and work-family stress: Associations with family food environments. Social Science &Medicine. 2012;75(3):496–504. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goulding AN, Rosenblum KL, Miller AL, Peterson KE, Chen Y-P, Kaciroti N et al. Associations between maternal depressive symptoms and child feeding practices in a cross-sectional study of low-income mothers and their young children. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2014;11(1):75. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-11-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dennis CL, McQueen K. The relationship between infant-feeding outcomes and postpartum depression: a qualitative systematic review. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):e736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coyne SM, McDaniel BT, Stockdale LA. “Do you dare to compare?” Associations between maternal social comparisons on social networking sites and parenting, mental health, and romantic relationship outcomes. Computers in Human Behavior. 2017;70:335–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.081. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henderson A, Harmon S, Newman H. The Price Mothers Pay, Even When They Are Not Buying It: Mental Health Consequences of Idealized Motherhood. Sex Roles. 2016;74(11):512–26. doi:10.1007/s11199-015-0534-5. [Google Scholar]

- * 34.Zenlea IS, Thompson B, Fierheller D, Green J, Ulloa C, Wills A et al. Walking in the shoes of caregivers of children with obesity: supporting caregivers in paediatric weight management. Clinical Obesity. 2017;7(5):300–6. doi:doi:10.1111/cob.12202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Qualitative paper highlighting feelings of isolation and blame in caregivers of children with obesity.

- 35.Bahreynian M, Qorbani M, Khaniabadi BM, Motlagh ME, Safari O, Asayesh H et al. Association between Obesity and Parental Weight Status in Children and Adolescents. Journal of Clinical Research in Pediatric Endocrinology. 2017;9(2):111–7. doi:10.4274/jcrpe.3790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holub SC, Tan CC, Patel SL. Factors associated with mothers' obesity stigma and young children's weight stereotypes. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2011;32(3):118–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2011.02.006. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andreassen P, Grøn L, Roessler KK. Hiding the Plot:Parents’ Moral Dilemmas and Strategies When Helping Their Overweight Children Lose Weight. Qualitative Health Research. 2013;23(10):1333–43. doi:10.1177/1049732313505151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Devine CM, Connors MM, Sobal J, Bisogni CA. Sandwiching it in: spillover of work onto food choices and family roles in low- and moderate-income urban households. Social science & medicine (1982). 2003;56(3):617–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * 39.Loth KA, Nogueira de Brito J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Fisher JO, Berge JM. A Qualitative Exploration Into the Parent-Child Feeding Relationship: How Parents of Preschoolers Divide the Responsibilities of Feeding With Their Children. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2018;50(7):655–67. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Qualitative paper highlighting parent decisionmaking, schedule constraints, and parent roles in feeding young children.

- 40.Devine CM, Farrell TJ, Blake CE, Jastran M, Wethington E, Bisogni CA. Work Conditions and the Food Choice Coping Strategies of Employed Parents. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2009;41(5):365–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiersma LD, Fifer AM. “The Schedule Has Been Tough But We Think It's Worth It”: The Joys, Challenges, and Recommendations of Youth Sport Parents. Journal of Leisure Research. 2008;40(4):505–30. doi:10.1080/00222216.2008.11950150. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Owens JA, Belon K, Moss P. Impact of delaying school start time on adolescent sleep, mood, and behavior. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2010;164(7):608–14. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thullen M, Majee W, Davis AN. Co-parenting and feeding in early childhood: Reflections of parent dyads on how they manage the developmental stages of feeding over the first three years. Appetite. 2016;105:334–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khandpur N, Charles J, Davison KK. Fathers' Perspectives on Coparenting in the Context of Child Feeding. Childhood Obesity. 2016;12(6):455–62. doi:10.1089/chi.2016.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davison KK, Gicevic S, Aftosmes-Tobio A, Ganter C, Simon CL, Newlan S et al. Fathers’ Representation in Observational Studies on Parenting and Childhood Obesity: A Systematic Review and Content Analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2016;106(11):e14–e21. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tan CC, Domoff S, Pesch MH, Lumeng JC, Miller AL. Coparenting in the Feeding Context: Perspectives of Fathers and Mothers of Preschoolers. Under Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilfley DE, Saelens BE, Stein RI, et al. Dose, content, and mediators of family-based treatment for childhood obesity: A multisite randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatrics. 2017;171(12):1151–9. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * 48.Quattrin T, Cao Y, Paluch RA, Roemmich JN, Ecker MA, Epstein LH. Cost-effectiveness of Family-Based Obesity Treatment. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3). doi:10.1542/peds.2016-2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Study compared an information-only to a family-based treatment for children with obesity and found family-based treatment to be more cost-effective.

- 49.Kral TVE, Chittams J, Moore RH. Relationship between food insecurity, child weight status, and parent-reported child eating and snacking behaviors. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing. 2017;22(2):e12177. doi:doi:10.1111/jspn.12177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Feinberg E, Kavanagh PL, Young RL, Prudent N. Food insecurity and compensatory feeding practices among urban black families. Pediatrics. 2008;122(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herman AN, Malhotra K, Wright G, Fisher JO, Whitaker RC. A qualitative study of the aspirations and challenges of low-income mothers in feeding their preschool-aged children. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2012;9(1):132. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-9-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bruening M, MacLehose R, Loth K, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Feeding a Family in a Recession: Food Insecurity Among Minnesota Parents. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(3):520–6. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kumanyika SK. Environmental influences on childhood obesity: Ethnic and cultural influences in context. Physiology & behavior. 2008;94(1):61–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cachelin FM, Thompson D. Predictors of maternal child-feeding practices in an ethnically diverse sample and the relationship to child obesity. Obesity. 2013;21(8):1676–83. doi:doi:10.1002/oby.20385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hughes SO, Anderson CB, Power TG, Micheli N, Jaramillo S, Nicklas TA. Measuring feeding in low-income African–American and Hispanic parents. Appetite. 2006;46(2):215–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * 56.Davison KK, Jurkowski JM, Li K, Kranz S, Lawson HA. A childhood obesity intervention developed by families for families: results from a pilot study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2013;10(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Intervention that was developed and led by parents in Head Start showed positive impact on child diet as well as obesity rates, and parents reported higher self-efficacy in promoting healthy eating.

- 57.Gruver RS, Bishop-Gilyard CT, Lieberman A, Gerdes M, Virudachalam S, Suh AW et al. A Social Media Peer Group Intervention for Mothers to Prevent Obesity and Promote Healthy Growth from Infancy: Development and Pilot Trial. JMIR Research Protocols. 2016;5(3):e159. doi:10.2196/resprot.5276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * 58.Fiks AG, Gruver RS, Bishop-Gilyard CT, Shults J, Virudachalam S, Suh AW et al. A Social Media Peer Group for Mothers To Prevent Obesity from Infancy: The Grow2Gether Randomized Trial. Childhood Obesity. 2017;13(5):356–68. doi:10.1089/chi.2017.0042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pilot RCT found that low-income mothers recruited during pregnancy participated in a social media intervention (Facebook group) and that intervention mothers reported change in infant feeding strategies at 6 months of age.

- 59.Ullmann G, Kedia SK, Homayouni R, Akkus C, Schmidt M, Klesges LM et al. Memphis FitKids: implementing a mobile-friendly web-based application to enhance parents’ participation in improving child health. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1068. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5968-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marks AK, Ejesi K, García Coll C. Understanding the U.S. Immigrant Paradox in Childhood and Adolescence. Child Development Perspectives. 2014;8(2):59–64. doi:doi:10.1111/cdep.12071. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bates LM, Acevedo-Garcia D, Alegría M, Krieger N. Immigration and Generational Trends in Body Mass Index and Obesity in the United States: Results of the National Latino and Asian American Survey, 2002–2003. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(1):70–7. doi:10.2105/ajph.2006.102814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baker EH, Rendall MS, Weden MM. Epidemiological Paradox or Immigrant Vulnerability? Obesity Among Young Children of Immigrants. Demography. 2015;52(4):1295–320. doi:10.1007/s13524-015-0404-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fuller B, Bridges M, Bein E, Jang H, Jung S, Rabe-Hesketh S et al. The Health and Cognitive Growth of Latino Toddlers: At Risk or Immigrant Paradox? Maternal and child health journal. 2009;13(6):755–68. doi:10.1007/s10995-009-0475-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * 64.Power TG, O'Connor TM, Orlet Fisher J, Hughes SO. Obesity Risk in Children: The Role of Acculturation in the Feeding Practices and Styles of Low-Income Hispanic Families. Childhood Obesity. 2015;11(6):715–21. doi:10.1089/chi.2015.0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Observational study finding that first-generation immigrant mothers showed more controlling feeding practices, and mothers born in the US showed more indulgent feeding practices, among low-income Hispanic mothers.

- 65.Martinez O, Wu E, Sandfort T, Dodge B, Carballo-Dieguez A, Pinto R et al. Evaluating the Impact of Immigration Policies on Health Status Among Undocumented Immigrants: A Systematic Review. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health / Center for Minority Public Health. 2015;17(3):947–70. doi:10.1007/s10903-013-9968-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Quandt SA, Shoaf JI, Tapia J, Hernández-Pelletier M, Clark HM, Arcury TA. Experiences of Latino Immigrant Families in North Carolina Help Explain Elevated Levels of Food Insecurity and Hunger. The Journal of Nutrition. 2006;136(10):2638–44. doi:10.1093/jn/136.10.2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]