Abstract

Objectives:

Institutional studies suggest robotic mitral surgery may be associated with superior outcomes. The objective of this study was to compare the outcomes of robotic, minimally invasive (mini), and conventional mitral surgery.

Methods:

A total of 2,351 patients undergoing non-emergent isolated mitral valve operations from 2011–2016 were extracted from a regional Society of Thoracic Surgeons database. Patients were stratified by approach: robotic(n=372), mini(n=576) and conventional sternotomy(n=1352). To account for preoperative differences, robotic cases were propensity score matched (1:1) to both conventional and mini approaches.

Results

Robotic cases were well matched to conventional (n=314) and mini (n=295) with no significant baseline differences. Rates of mitral repair were high in the robotic and mini cohorts (91%), but significantly lower with conventional (76%, p<0.0001) despite similar rates of degenerative disease. All procedural times were longest in the robotic cohort, including operative time (224 vs 168 minutes conventional, 222 vs 180 minutes mini; all p<0.0001). Robotic approach had comparable outcomes to conventional except fewer discharges to a facility (7% vs 15%, p=0.001) and 1 less day in the hospital (p<0.0001). However, compared to mini, robotic approach had higher transfusion (15% vs 5%, p<0.0001), atrial fibrillation rates (26% vs 18%, p=0.01) and 1 day longer average hospital stay (p=0.02).

Conclusion:

Despite longer procedural times, robotic and mini patients had similar complication rates with higher repair rates and shorter length of stay metrics compared to conventional surgery. However, robotic approach is associated with greater atrial fibrillation, transfusion and longer postoperative stays compared to minimally invasive approach.

INTRODUCTION

While it has always been a specialty of innovation, cardiac surgery is currently experiencing both a voluntary and forced period of technological advancement.1 Percutaneous alternatives and patient demand are currently forcing a push away from surgery via a conventional sternotomy. Mitral valve operations have been at the forefront of these advances with the first minimally invasive (mini) mitral surgeries via a right mini-thoracotomy performed in 1996 separately by Carpentier and Chitwood.2,3 Not long thereafter in 1998, Carpentier and others performed the first mitral operations with an early version of the da Vinci Surgical System (Intuitive Surgical Inc., Sunnyvale, California, USA).4,5 Currently, mitral valve repair is the most commonly performed cardiac operation performed with a robotic approach.6

Robot assisted surgical strategies have enabled smaller incisions, improved visualization with a three-dimensional camera, and enhanced dexterity with greater range of motion and tremor reduction. The theoretical benefits of the robot come with challenges including a steep learning curve, need for peripheral cannulation, and increased procedural times and costs of surgical equipment.7,8 One recent study suggests cardiopulmonary bypass times don’t stabilize until after 200 operations.9 While surgical costs are increased, new studies suggest the robot may still be a cost-effective approach to mitral repair of degenerative valve disease in high-volume, specialized centers.10

Despite these significant barriers to use of the robot, several potential benefits have been identified including reduced short-term mortality, fewer transfusions, and shorter postoperative length of stay (LOS).8,11,12 This approach may also improve quality of life and allow patients to return to work faster.13 However, the data comparing robotic mitral valve surgery to either conventional or mini approaches is limited, and typically single center reports. The objective of this study was to compare patient outcomes and resource utilization of robotic, mini, and conventional approaches for isolated mitral surgery. We hypothesized that robotic and mini approaches would be associated with reduced postoperative morbidity and resource utilization compared to conventional sternotomy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Data

The Virginia Cardiac Services Quality Initiative (VCSQI) is a regional, multi-state collaborative of 19 hospitals. Member hospitals submit clinical data collected for the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) adult cardiac datase to VCSQI. The primary object.ee of VCSQI is quality improvement with ongoing collaborative projects. This analysis represents a secondary analysis of the VCSQI data registry without Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act patient identifiers and is therefore exempt from institutional review board review. Business associate agreements are in place between VCSQI, members and the database vendor (ARMUS Corporation, San Mateo, CA).

All records for patients undergoing isolated mitral valve surgery from 2011–2016 were extracted from the regional database in a de-identified manner. Patients were excluded for emergent or emergent salvage procedures. Patients were stratified by approach into either robotic surgery, minimally invasive via mini thoracotomy, or conventional median sternotomy. Clinical variables utilize standard STS definitions.(12) Operative mortality is defined as either 30-day or in-hospital mortality. Major morbidity includes permanent stroke, prolonged ventilation, reoperation for any reason, renal failure and deep sternal wound infection.

Statistical Analysis

For the entire cohort, henceforth referred to as the prematched cohort, categorical variables are presented as counts (%) and continuous variables as median [25th, 75th percentile]. Patients were stratified by approach and compared by univariate analysis using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and Chi-square test for categorical variables. To account for baseline differences in patients between the different approaches patients who underwent robotic mitral surgery were propensity score matched to conventional surgical approach and separately to minimally invasive approach. In order to accomplish this, variables with <5% missing data were imputed using STS methodology that includes the lower risk category for categorical variables and the median for continuous variables, with gender specific medians for body surface area. Next, propensity scores were calculated for each patient using logistic regression including 33 preoperative characteristics (Supplemental Table 1). The patients were then matched using a greedy algorithm starting at 8 digits of the propensity score and matching sequentially to the largest digit. The adequacy of the match was determined by standardized mean difference of baseline variables, with a goal of less than 20%. The propensity score distribution was also visualized to assess the impact of the match.

For the matched cohort, patients are again presented as counts (%) and median [25th, 75th percentile]. Groupings, both robotic/conventional and robotic/mini, were compared by paired univariate analysis. Categorical variables were compared using McNemar’s Test and continuous variables compared by Signed Rank Test. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institutive, Cary, NC) with a p-value less than 0.05 determining significance.

RESULTS

Prematched Cohorts

A total of 372 robotic, 576 mini and 1,352 conventional sternotomy patients underwent non-emergent isolated mitral valve surgery within the collaborative over this 6-year period. Of the hospitals within the collaborative, 6 (32%) have performed robotic mitral surgery, and of these hospitals only 2 have performed more than 50 cases. Within the collaborative 11 (58%) have performed minimally invasive mitral surgery and 4 have performed more than 50 cases. As shown in Supplemental Figure 1, the median yearly case volume of surgeons who performed robotic surgery was 5 [4.5–12.8], for mini 4.3 [2.7–10], and for conventional 3 [1.6–5]. The robotic surgeon yearly volume was significantly higher than conventional (p=0.011) but not mini (p=0.343). Mini surgeon yearly volume was also significantly higher than conventional (p=0.005).

At baseline patients differed significantly between approaches with robotic cases being the lowest risk with median predicted risk of mortality (PROM) 0.7% versus 0.9% mini and 1.6% conventional (p<0.0001). Additionally, robotic cases had the lowest rates of many comorbidities (Supplemental Table 2). Robotic cases had the highest rate of degenerative mitral valve disease (81% vs 70% mini vs 45% conventional, p<0.0001) and the highest rate of mitral repair (90% vs 83% mini vs 52% conventional, p<0.0001).

Operative mortality was low for all approaches (0.8% robotic vs 1.9% mini, 3.4% conventional; Supplemental Table 3). These rates are within the expected range with observed to expected ratios (O:E) for robotic of 0.62, (p=0.408), mini O:E 0.70 (p=0.226), and conventional O:E 0.99 (p=0.952). Rates of major morbidity were also low for all groups (8.6% robotic, 8.5% mini, 15.0% conventional, p=0.010). All three groups had rates of morbidity or mortality that were significantly lower than expected, robotic O:E 0.69 (p=0.020), mini O:E 0.53 (p<0.0001) and conventional O:E 0.72, (p<0.0001).

Propensity matched baseline and operative characteristics

A total of 628 patients were matched between robotic and conventional approaches and were well matched with all baseline covariates having a standardized mean difference of less than 10% (Supplemental Figures 2 and 3). There were no significant differences between matched pairs for any baseline characteristics (Table 1). The median PROM was 0.6% robotic vs 0.8% conventional, p=0.109. While the rate of degenerative mitral disease was 79% in robotic and 78% in conventional patients (p=0.73), the rate of mitral repair was significantly higher in the robotic group (91% vs 76%, p<0.0001; Table 2). Types of repair were also different with 38% of patients receiving a leaflet resection in the robotic group vs 51% in the conventional group (p=0.006). Neochords were placed in 30% of robotic and 25% of conventional cases (p=0.09). Although the rate of preoperative atrial fibrillation was similar (12% vs 10%, p=0.43), fewer robotic patients received left atrial appendage ligation (6% vs 15%, p=0.0002). Finally, the robotic group had 17 minute longer cross-clamp and 28 minute longer cardiopulmonary bypass times (both p<0.0001).

Table 1:

Baseline and operative patient characteristics

| Baseline Characteristics | Robotic (n = 314) |

Conventional (n = 314) |

p value | Robotic (n = 295) |

Mini (n = 295) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 61 [53–69] | 61 [53–69] | 0.926 | 61 [53–69] | 61 [52–70] | 0.789 |

| Female | 127 (40.5%) | 136 (43.3%) | 0.449 | 118 (40.0%) | 121 (41.0%) | 0.801 |

| CLD (moderate/severe) | 16 (5.1%) | 15 (4.8%) | 0.853 | 14 (4.8%) | 12 (4.1%) | 0.670 |

| Prior stroke | 20 (6.4%) | 19 (6.1%) | 0.869 | 16 (5.4%) | 18 (6.1%) | 0.715 |

| Diabetes | 42 (13.4%) | 41 (13.1%) | 0.904 | 30 (10.2%) | 33 (11.2%) | 0.696 |

| End stage renal disease | 4 (1.3%) | 6 (1.9%) | 0.527 | 3 (1.0%) | 5 (1.7%) | 0.480 |

| Preoperative atrial fibrillation | 37 (11.8%) | 31 (9.9%) | 0.431 | 33 (11.2%) | 39 (13.2%) | 0.376 |

| Hypertension | 196 (62.4%) | 201 (64.0%) | 0.674 | 174 (59.0%) | 181 (61.4%) | 0.547 |

| Coronary artery disease | 48 (15.3%) | 46 (14.7%) | 0.823 | 43 (14.6%) | 45 (15.3%) | 0.819 |

| Heart failure within 2 weeks | 166 (52.9%) | 168 (53.5%) | 0.865 | 149 (50.5%) | 146 (49.5%) | 0.788 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 60 [55–63] | 60 [55–65] | 0.409 | 60 [55–64] | 60 [55–65] | 0.689 |

| MR (moderate/severe) | 304 (96.8%) | 306 (97.5%) | 0.617 | 285 (96.6%) | 285 (96.6%) | 1.00 |

| Mitral stenosis | 15 (4.8%) | 14 (4.5%) | 0.827 | 15 (5.1%) | 12 (4.1%) | 0.532 |

| TR (moderate/severe) | 45 (19.0%) | 55 (21.7%) | 0.789 | 44 (20.0%) | 35 (16.7%) | 0.405 |

| Prior cardiac surgery | 22 (7.0%) | 19 (6.1%) | 0.622 | 22 (7.5%) | 23 (7.8%) | 0.862 |

| STS PROM | 0.6% [0.4–1.4%] | 0.8% [0.5–1.5%] | 0.109 | 0.6% [0.4–1.2%] | 0.6% [0.3–1.4%] | 0.538 |

IQR = interquartile range; CLD = chronic lung disease; MR = mitral regurgitations; PROM = predicted risk of mortality

Table 2:

Operative characteristics of matched cohorts

| Operative Characteristics | Robotic | Conventional | p-value | Robotic | Mini | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degenerative mitral disease | 248 (79.0%) | 245 (78.0%) | 0.726 | 242 (82.0%) | 240 (81.4%) | 0.823 |

| Ischemic mitral disease | 3 (1.0%) | 3 (1.0%) | 1.00 | 3 (1.0%) | 3 (1.0%) | 1.00 |

| Rheumatic mitral disease | 22 (7.0%) | 23 (7.3%) | 0.873 | 16 (5.4%) | 17 (5.8%) | 0.858 |

| Endocarditis mitral disease | 20 (6.4%) | 20 (6.4%) | 1.00 | 12 (4.1%) | 16 (5.4%) | 0.450 |

| Elective | 300 (95.5%) | 299 (95.2%) | 0.819 | 12 (4.1%) | 16 (5.4%) | 0.450 |

| Mitral Repair | 284 (90.5%) | 237 (75.5%) | <0.0001 | 269 (91.2%) | 268 (90.9%) | 0.886 |

| Leaflet resection | 107 (37.7%) | 121 (51.3%) | 0.006 | 102 (37.9%) | 88 (33.0%) | 0.556 |

| Neochord | 86 (30.2%) | 58 (24.5%) | 0.092 | 84 (31.2%) | 99 (37.1%) | 0.366 |

| Left atrial appendage ligation | 18 (5.7%) | 46 (14.7%) | 0.0002 | 15 (5.1%) | 7 (2.4%) | 0.074 |

| Cross-clamp time (min) | 97 [83–119] | 81 [64–98] | <0.0001 | 97 [83–115] | 86 [86–94] | <0.0001 |

| CPB time (min) | 140 [121–172] | 112 [89–142] | <0.0001 | 139 [121–170] | 130 [118–155] | 0.002 |

| Operative time (min) | 224 [200–361] | 168 [147–207] | <0.0001 | 222 [199–260] | 180 [147–211] | <0.0001 |

| Operating room time (min) | 315 [276–361] | 229 [205–273] | <0.0001 | 310 [275–355] | 250 [209–290] | <0.0001 |

| Conversion | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | - |

CPB = cardiopulmonary bypass

A total of 590 patients were well matched between robotic and mini approaches with all baseline variables having a standardized mean difference of less than 10% (Supplemental Figures 4 and 5). The median PROM 0.6% for both robotic and mini cohorts, p=0.538. The rate of degenerative mitral disease in the robotic and mini matched cohort was 82% vs 81%, p=0.823. The rate of mitral repair was 91% in both groups with leaflet resection in 38% of robotic and 33% of mini cases (p=0.89) and neochords used in 31% of robotic and 37% of mini cases (p=0.37). Preoperative atrial fibrillation rates were similar at 11% vs 13% (p=0.38), and left atrial appendage ligation was low in both groups (5% vs 2%, p=0.07). Finally, the robotic group had 8 minute longer cross-clamp and cardiopulmonary bypass times (both p<0.0001).

Matched short-term outcomes

Outcomes by approach are displayed in Table 3. There was Between robotic and conventional approaches, there were no statistically significant difference in rate of mortality (0.6% vs 2.2%, p=0.06). Similarly, there was no significant difference in rate of major morbidity (9% vs 9%, p=0.89) or its component complications, with no deep sternal wound infections recorded in either group. The rate of pneumonia was 1.6% in both groups (p=1.00). There were similar rates of postoperative atrial fibrillation, transfusion and reoperation. The rate of reoperation for any reason was 5% in the robotic group vs 4% in the conventional group (p=0.32).

Table 3:

Operative outcomes

| Operative Outcomes | Robotic | Conventional | p-value | Robotic | Mini | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operative mortality | 2 (0.6%) | 7 (2.2%) | 0.059 | 2 (0.7%) | 2 (0.7%) | 1.00 |

| Major morbidity | 27 (8.6%) | 28 (8.9%) | 0.886 | 23 (7.8%) | 17 (5.8%) | 0.330 |

| Permanent stroke | 4 (1.3%) | 3 (1.0%) | 0.706 | 4 (1.4%) | 3 (1.0%) | 0.706 |

| Cardiac arrest | 1 (0.3%) | 3 (1.0%) | 0.317 | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.317 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 78 (24.8%) | 87 (27.7%) | 0.421 | 78 (26.4%) | 52 (17.6%) | 0.013 |

| Prolonged ventilation | 13 (4.1%) | 18 (5.7%) | 0.353 | 9 (3.1%) | 9 (3.1%) | 1.00 |

| Renal failure requiring dialysis | 2 (0.6%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0.564 | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.317 |

| Transfusion (PRBC) | 48 (15.3%) | 56 (17.8%) | 0.371 | 45 (15.3%) | 14 (4.8%) | <0.0001 |

| Reoperation for bleeding | 8 (2.6%) | 6 (1.9%) | 0.593 | 8 (2.7%) | 4 (1.4%) | 0.248 |

| Readmission | 34 (10.9%) | 26 (8.9%) | 0.500 | 30 (10.3%) | 19 (6.5%) | 0.093 |

| Discharge to facility | 22 (7.0%) | 46 (14.8%) | 0.001 | 16 (5.4%) | 17 (5.8%) | 0.847 |

| Length of stay (d) | 4 [4–6] | 5 [4–7] | <0.0001 | 4 [4–6] | 4 [2–6] | 0.017 |

| ICU stay (hr) | 26 [23–45] | 31 [23–72] | <0.0001 | 26 [23–45] | 24 [11–47] | 0.005 |

ICU = intensive care unit; PRBC = packed red blood cell

There were no significant differences between robotic and mini approaches in rates of mortality (0.7% vs 0.7%, p=1.00) or major morbidity (8% vs 6%, p=0.33), with no deep sternal wound infections recorded in either group. The rate of pneumonia was 1.0% in robotic and 0.3% in mini patients (p=0.32). There was a significantly higher rate of postoperative atrial fibrillation in the robotic cohort versus mini (26% vs 18%, p=0.01). There was also a 31% higher transfusion rate of packed red blood cells (PRBC) in the robotic cohort (15% vs 5%, p<0.0001). The overall rate of transfusion of any blood products was 30% higher in the robotic cohort (18% vs 5%, p<0.0001). There was no difference in rates of reoperation for any reason(5% vs 2%, p=0.13) or for bleeding (3% vs 1%, p=0.25).

Matched resource utilization

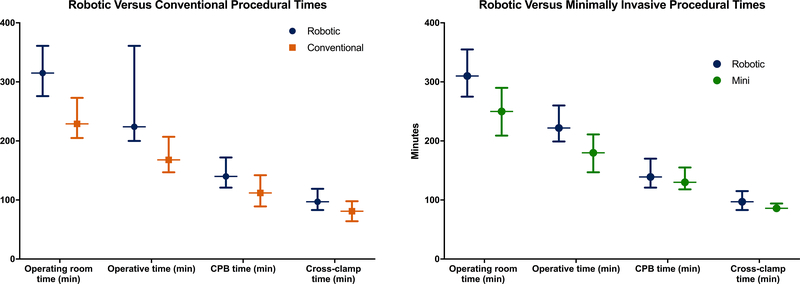

Robotic approach was associated with longer procedural times than conventional including 55 minute longer operative, and 83 minute longer operating room times (both p<0.0001; Figure 1). However, robotic patients had shorter postoperative stays including a 1 day shorter LOS and 3.3 hours less in the ICU (both p<0.0001). Robotic approach was associated with a lower rate of discharge to a facility (7% vs 15%, p=0.001) and an equivalent rate of readmission (11% vs 9%, p=0.50).

FIGURE 1.

A. Robotic (blue) versus conventional (orange) procedural times. B. Robotic (blue) versus minimally invasive (green) procedural times. Data represents median and interquartile range with all comparisons significantly different, p<0.01.

Robotic approach had longer procedural times than mini by 48 minutes for operative and 57 minutes operating room times (both p<0.0001). Robotic approach had a median postoperative LOS 1 day longer than mini (p=0.017), 5.3 hours longer in the ICU (p=0.005). Robotic and mini approach had equivalent rates of discharge to a facility (5% vs 6%, p=0.85) and hospital readmission (10% vs 7%, p=0.09).

DISCUSSION

This is the first multi-institutional analysis comparing conventional sternotomy, minimally invasive approach, and robotic mitral valve surgery. Within propensity matched cohorts, robotic approach was associated with a higher rate of mitral repair than conventional sternotomy but identical repair rates as minimally invasive. Robotic approach was also associated with longer procedural times across the board compared to both conventional and mini. Conversely, robotic approach was associated with shorter postoperative LOS compared to conventional, but longer postoperative LOS compared to mini. This may be due to the mini approach having less postoperative atrial fibrillation and fewer transfusions. The repair rates for robotic and mini approaches exceeded 90% and was significantly higher than the repair rate of 76% in the conventional approach and may be due to more experienced surgeons performing less invasive mitral surgery.14,15

This analysis found robotic surgery required an additional 17, 28, and 83 min, respectively, for cross-clamp, cardiopulmonary bypass, and operating room time compared to conventional surgery. These findings corroborate previous reports that have demonstrated robotic surgery requiring 27–45 min additional cross clamp and 36–77min longer cardiopulmonary bypass times compared to conventional surgery.11,12,16,17 Compared to mini, robotic approach was associated with 8 additional minutes in both cross-clamp and cardiopulmonary bypass times as well as 57 minutes of operating room time compared to mini, much lower than previously reported.11 The incremental increase in procedural times between conventional, mini and robotic approaches correlates with increasing procedural complexity. Additionally, the dramatic increases in operating room time show that a robotic approach impacts not only the patient but also hospital resources. Finally, in this contemporary cohort the procedural time differences are lower than previously reported. This may be a result of increasing program experience, although median times are consistently shorter than mean due to the skewed nature of these variables.

Robotic surgery was found to have a higher rate of PRBC and any transfusion compared to mini, although similar to the conventional approach. The PRBC transfusion rate of 15% compares favorably to prior robotic surgery publications.11,12,18 The finding of a higher transfusion rate compared to mini is therefore a result of the very low transfusion rate in the mini cohort (5% for PRBC). Only a single study has demonstrated decreased transfusions with robotic versus conventional approach, while there is strong literature supporting fewer transfusions with minimally invasive mitral surgery compared to sternotomy.19–21 The lack of sternal bone marrow or sternal wire injuries and the femoral cannulation sites all drive lower rates of bleeding in the mini cohort. While this should also be realized in the robotic cohort, it is possible the push to smaller port sizes and longer operative time may limit visualization and increase coagulopathy resulting in bleeding and higher transfusion requirements.

The finding of increased postoperative atrial fibrillation in the robotic compared to mini cohort is again a function of the low rate seen in the mini cohort. It is possible that less traumatic surgery with a minimally invasive approach is resulting is less postoperative atrial fibrillation. While the mini cohort is benefiting, this is offset in the robotic group by the prolonged myocardial ischemic and cardiopulmonary bypass times.22,23 It is also possible that variation in hospital prophylaxis protocols is driving the low rate of atrial fibrillation in the mini cohort. It was surprising to see similar rates of atrial fibrillation in the conventional and robotic cohorts as some prior studies have demonstrated reduced rates with robotic approach.11,24 The variability in this finding warrants further investigation to help improve quality and patient outcomes.

Compared to conventional sternotomy, robotic surgery was associated with decreased postoperative resource utilization. This includes fewer patients discharged to a facility, a finding that fits with prior reports of patients returning to work faster with robotic surgery.13 Although most studies demonstrate shorter length of stay, the results are mixed with a recent meta-analysis finding comparable ICU and hospital LOS in robotic and conventional cohorts.8,12,16,17,25 However, the functional benefits of a mini-thoracotomy or entirely endoscopic approach are significant compared to a sternotomy. This is clear with robotic patients leaving the ICU and hospital faster, and more of them going home, compared to conventional sternotomy. These benefits of not performing a sternotomy appear to be blunted by increased rates of bleeding/transfusion and atrial fibrillation in the robotic group compared to mini, resulting in longer ICU and hospital lengths of stay. It is clear the function benefits can only be realized if postoperative complications are prevented.

The limitations of this study include its retrospective nature, prohibiting any causal relationships from being determined and introducing some level of selection bias into the analysis. The propensity score matching is designed to help eliminate differences in this bias between groups, but is not a perfect substitute for randomized controlled trials. The design also selects a subgroup of patients that are not representative of all patients who undergo mitral valve surgery, particularly those who undergo surgery by a conventional approach. Additionally, the study is limited by the dataset utilized, which in this case contains STS variables that have high validity but are limited to short-term outcomes. Finally, there is a potential for surgeon bias, with surgeon yearly volume likely accounting for the higher repair rate seen in robotic and mini cohorts.14,15,26 However, the median surgeon yearly volume differences are small. Additionally, the surgeon volume to outcome relationship appears largely limited to the repair rate, repair durability and survival. The other outcome differences noted in this analysis are thus unlikely to be related to potential bias in surgeon experience.

CONCLUSION

Conventional sternotomy, mini thoracotomy, and robotic surgery are all safe and effective approaches to perform mitral valve surgery. However, robotic surgery it is associated with longer crossclamp, cardiopulmonary bypass, and operating room times than other approaches. Compared to conventional sternotomy, this increase in resource utilization in robotic surgery is compensated for by decreased postoperative LOS both overall and in the ICU. Additionally, patients are more likely to be discharged home. However, compared to a mini thoracotomy approach, the increase in procedural times with robotic surgery are in addition to longer postoperative lengths of stay with higher rates of postoperative atrial fibrillation and blood transfusions. Therefore, when looking to add technical expertise, surgeons should consider the improved resource utilization and outcomes associated with minimally invasive approach. From a patient perspective, all three approaches provide excellent outcomes, thus patient preference and surgeon experience should dictate the approach for mitral valve surgery.

Supplementary Material

What is already known about this subject?

Robotic and minimally invasive mitral surgery have been shown to provide excellent outcomes in single center studies. However, there are downsides to each including longer procedural times and learning curves that limit surgeon adoption.

What does this study add?

In this multi-institutional analysis, robotic and mini patients have excellent outcomes with a mortality rate <1%, major morbidity rate <9% and mitral repair rates of 91%. Compared to conventional surgery, robotic approach has a higher repair rate at 91% vs 76%, and 1 day shorter postoperative length of stay. However, robotic approach is associated with greater atrial fibrillation (26% vs 18%), more transfusions (15% vs 5%) and 1 day longer postoperative stay compared to minimally invasive approach.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Given the tradeoffs across all three approaches to mitral valve surgery, patient preference and surgeon experience should dictate the approach for mitral valve surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (T32HL007849). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

Dr. Ailawadi is a consultant for Abbott, Edwards, Medtronic, and Cephea. Dr. Speir is a consultant on the Medtronic Cardiac Surgery Advisory Board. No other authors report conflicts of interest.

Classifications: Mitral valve disease, minimally invasive surgery, robotic surgery

REFERENCES

- 1.del Nido PJ. Surgical Innovation: Lessons From the Pragmatic Philosophical School. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;100(3):778–83. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.03.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chitwood WR Jr., Elbeery JR, Chapman WH, et al. Video-assisted minimally invasive mitral valve surgery: the “micro-mitral” operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1997;113(2):413–4. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(97)70341-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carpentier A, Loulmet D, Carpentier A, et al. [Open heart operation under videosurgery and minithoracotomy. First case (mitral valvuloplasty) operated with success]. C R Acad Sci III 1996;319(3):219–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carpentier A, Loulmet D, Aupecle B, et al. [Computer assisted open heart surgery. First case operated on with success]. C R Acad Sci III 1998;321(5):437–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohr FW, Falk V, Diegeler A, et al. Computer-enhanced “robotic” cardiac surgery: experience in 148 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001;121(5):842–53. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.112625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bush B, Nifong LW, Alwair H, et al. Robotic mitral valve surgery-current status and future directions. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2013;2(6):814–7. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2013.10.04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moss E, Halkos ME. Cost effectiveness of robotic mitral valve surgery. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2017;6(1):33–37. doi: 10.21037/acs.2017.01.03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao C, Wolfenden H, Liou K, et al. A meta-analysis of robotic vs. conventional mitral valve surgery. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2015;4(4):305–14. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2014.10.05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillinov AM, Mihaljevic T, Javadikasgari H, et al. Early results of robotically assisted mitral valve surgery: Analysis of the first 1000 cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.07.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mihaljevic T, Koprivanac M, Kelava M, et al. Value of robotically assisted surgery for mitral valve disease. JAMA Surg 2014;149(7):679–86. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.5680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevens LM, Rodriguez E, Lehr EJ, et al. Impact of timing and surgical approach on outcomes after mitral valve regurgitation operations. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;93(5):1462–8. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woo YJ, Nacke EA. Robotic minimally invasive mitral valve reconstruction yields less blood product transfusion and shorter length of stay. Surgery 2006;140(2):263–7. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suri RM, Antiel RM, Burkhart HM, et al. Quality of life after early mitral valve repair using conventional and robotic approaches. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;93(3):761–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.201L1L062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chikwe J, Toyoda N, Anyanwu AC, et al. Relation of Mitral Valve Surgery Volume to Repair Rate, Durability, and Survival. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LaPar DJ, Ailawadi G, Isbell JM, et al. Mitral valve repair rates correlate with surgeon and institutional experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;148(3):995–1003; discussion 03–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.06.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folliguet T, Vanhuyse F, Constantino X, et al. Mitral valve repair robotic versus sternotomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2006;29(3):362–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suri RM, Burkhart HM, Daly RC, et al. Robotic mitral valve repair for all prolapse subsets using techniques identical to open valvuloplasty: establishing the benchmark against which percutaneous interventions should be judged. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;142(5):970–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramzy D, Trento A, Cheng W, et al. Three hundred robotic-assisted mitral valve repairs: the Cedars-Sinai experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;147(1):228–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.09.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Downs EA, Johnston LE, LaPar DJ, et al. Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery Provides Excellent Outcomes Without Increased Cost: A Multi-Institutional Analysis. Ann Thorac Surg 2016; 102(1): 14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.01.084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luca F, van Garsse L, Rao CM, et al. Minimally invasive mitral valve surgery: a systematic review. Minim Invasive Surg 2013;2013:179569. doi: 10.1155/2013/179569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gammie JS, Zhao Y, Peterson ED, et al. Maxwell J Chamberlain Memorial Paper for adult cardiac surgery. Less-invasive mitral valve operations: trends and outcomes from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;90(5): 1401–8, 10 e1; discussion 08–10. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.05.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akintoye E, Sellke F, Marchioli R, et al. Factors associated with postoperative atrial fibrillation and other adverse events after cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.07.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaireviciute D, Aidietis A, Lip GY. Atrial fibrillation following cardiac surgery: clinical features and preventative strategies. Eur Heart J 2009;30(4):410–25. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mihaljevic T, Jarrett CM, Gillinov AM, et al. Robotic repair of posterior mitral valve prolapse versus conventional approaches: potential realized. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;141(1):72–80 e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paul S, Isaacs AJ, Jalbert J, et al. A population-based analysis of robotic-assisted mitral valve repair. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;99(5):1546–53. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.12.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gammie JS, O’Brien SM, Griffith BP, et al. Influence of hospital procedural volume on care process and mortality for patients undergoing elective surgery for mitral regurgitation. Circulation 2007; 115(7): 881–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.634436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.