Abstract

Ibrutinib and idelalisib are kinase inhibitors that have revolutionized the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Capable of inducing durable remissions, these agents also modulate the immune system. Both ibrutinib and idelalisib abrogate the tumor-supporting microenvironment by disrupting cell-cell interactions, modulating the T-cell compartment and altering the cytokine milieu. Ibrutinib also partially restores T-cell and myeloid defects associated with CLL. In contrast, immune-related adverse effects, including pneumonitis, colitis, hepatotoxicity, and infections are of particular concern with idelalisib. While opportunistic infections and viral reactivations occur with both ibrutinib and idelalisib, these complications are less common and less severe with ibrutinib, especially when used as monotherapy without additional immunosuppressive agents. This review discusses the impact of ibrutinib and idelalisib on the immune system, including infectious and auto-immune complications as well as their specific effects on the B-cell, T-cell and myeloid compartment.

Keywords: Lymphoid Leukemia, Signaling therapies, T-Cell Mediated Immunity, The Humoral Immune Response

Introduction

Immune dysregulation is a hallmark of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Clinical manifestations such as an increased susceptibility to infections and autoimmunity are associated with morbidity and mortality. Chemoimmunotherapy frequently causes severe neutropenia, placing patients at even greater risk of infectious complications. Fludarabine, a backbone of chemoimmunotherapy regimens, can precipitate and exacerbate autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Kinase inhibitors that target growth and survival pathways in CLL cells are now approved for clinical use; however, the targeted kinases are also functionally important in normal immune cells. Herein, we will review the effects of the first two approved kinase inhibitors, ibrutinib and idelalisib, on the immunity of patients with CLL.

Infections

Infections are a well-recognized complication and a common cause of death in CLL. An important limitation of chemoimmunotherapy is the increased risk of infection. Ibrutinib is the first-in-class inhibitor of Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK), a key member of the B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling pathway. In the frontline setting, infections occur at a lower rate with ibrutinib compared to chemoimmunotherapy (Table) [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. When patients start ibrutinib, the risk of infections is highest during the first 6 months of therapy and then subsequently decreases [6, 7]. The distribution of infections is similar to CLL in general with the respiratory tract being the predominant site of infections [7]. Grade ≥ 3 pneumonia develops in 4% to 12% of patients treated with ibrutinib [8, 9].

Idelalisib, an oral inhibitor of PI3Kδ, is approved, in combination with rituximab, to treat relapsed CLL. PI3Kδ and BTK are interconnected in the BCR signaling pathway and both are essential for signal transduction [10]. Although no head-to-head comparison of idelalisib and ibrutinib has been reported, the rate of infections during treatment with idelalisib appears to be higher. Notably, grade ≥ 3 pneumonia occurred in 19% and 8% of patients in two phase 2 trials of idelalisib and rituximab in the upfront and salvage settings, respectively [11, 12].

As experience with ibrutinib and idelalisib grows, the risk of opportunistic infections is increasingly appreciated. Six trials of idelalisib combined with other drugs to treat CLL and indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma were halted due to an increased incidence of death predominantly from opportunistic infections [14, 15]. In the phase 3 randomized trial of bendamustine and rituximab with idelalisib or placebo for previously treated CLL, patients receiving idelalisib had more pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PJP, 2% versus 0%) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection (6% versus 1%) than those in the placebo group [16]. A retrospective analysis of over 2,100 patients in the idelalisib clinical development program also found an increased risk of PJP with the use of idelalisib [17]. Prophylaxis against PJP somewhat mitigated this risk, but it is hard to identify at-risk patients because neither CD4 count nor age was associated with PJP. PJP was also reported in 5 CLL patients after a median of 6 months on ibrutinib, 4 being treated in first-line [18]. Unlike the severe clinical picture seen in acquired immunodeficiency, the patients in this case series were either asymptomatic or only had mild symptoms of dyspnea and cough. Since ibrutinib is administered continuously until disease progression, the decision to start prophylaxis against PJP represents a long-term commitment and should be carefully discussed with patients. In our experience, ibrutinib-treated patients diagnosed with PJP respond clinically and radiologically to oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

Aspergillus infections have also been a concern with ibrutinib use. In a study evaluating ibrutinib for the treatment of primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma, 2 of 18 (11%) patients died of aspergillus lung and CNS involvement on ibrutinib monotherapy and 7 of 16 (44%) patients developed lung and CNS aspergillus infection when ibrutinib was combined with chemotherapy and corticosteroids. In addition, aspergillus brain abscesses were reported in 3 patients with CLL treated with ibrutinib and concomitant corticosteroids [19]. The high incidence of fungal infections with ibrutinib may be related to co-administration of steroids causing additional immunosuppression and the deleterious effects of ibrutinib on macrophage function [20].

Viral infection or reactivation has been problematic especially with idelalisib, contributing to increased CMV-associated fatalities in combination therapies as mentioned above [14, 15]. In addition, disseminated varicella zoster was reported in 2 patients on ibrutinib and 1 patient on idelalisib leading to death [21]. Both patients on ibrutinib were successfully treated with intravenous acyclovir followed by long-term valacyclovir suppression. Hepatitis B reactivation has also been reported in the literature after treatment of CLL with ibrutinib [22]. Finally, there is a case report of central nervous system (CNS) non-HIV associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome after ibrutinib therapy for Richter transformation, thought to be triggered by latent CMV CNS infection [23].

Autoimmunity

Cytopenias

Another defining feature of immune dysfunction in CLL is autoimmunity, especially autoimmune cytopenia (AIC). During the course of their disease, 2 to 10% of patients develop autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) due to antibodies against autologous red blood cells [24, 25]. Treatment with fludarabine, advanced disease stage, unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable (IGHV) gene, and adverse cytogenetic abnormalities have been associated with an increased risk of AIHA [26, 27]. Less commonly, immune thrombocytopenia, and rarely, pure red cell aplasia can occur.

Conflicting data exist regarding the risk of AIC in the context of ibrutinib therapy. On one hand, treatment-emergent AIC, including flares of preexisting AIC and less commonly, de novo AIC, have been reported [28, 29]. On the other hand, treatment with ibrutinib has also been associated with resolution of AIC and seroconversion to a negative direct antiglobulin test [28]. An important caveat is that most clinical trials of ibrutinib excluded patients with active AIC, which may distort the incidence of AIC relative to ibrutinib use in the community.

Organ manifestations

Autoimmune complications are a significant concern with the use of idelalisib. Grade ≥ 3 diarrhea, transaminitis and pneumonitis occurred in 7%, 8%, and 4% of patients receiving idelalisib and rituximab as salvage therapy [11, 12]. Surprisingly, these adverse events increased in frequency when idelalisib was used in first-line. In a phase 2 study of idelalisib and rituximab for previously untreated CLL, the rates of grade ≥ 3 colitis or diarrhea, transaminitis and pneumonitis were 42%, 23%, and 3%, respectively [13]. In addition to line of therapy, risk factors for immune-mediated adverse events are treatment naïve CLL, younger age and mutated IGHV status [30]. The role of T cells in the underlying pathophysiology will be discussed later in this review.

The safety profile appears to be different with novel PI3Kδ inhibitors. Umbralisib is a dual inhibitor of PI3Kδ and casein kinase under clinical investigation. In a phase 1 dose escalation study of umbralisib for relapsed or refractory lymphoid malignancies, grade ≥ 3 colitis and transaminitis occurred in 3% and 2% of patients, respectively [31]. No pneumonitis or opportunistic infections were observed.

B cells

B cells play a crucial role in humoral immunity, antigen presentation and secretion of co-stimulatory cytokines. The BCR is a membrane-bound structure responsible for antigen recognition in B cells. Signaling through the BCR provides essential trophic signals for normal B cells and CLL cells alike. BTK and PI3Kδ are downstream members necessary for signal transduction. These intracellular kinases are inhibited by ibrutinib and idelalisib respectively resulting in swift and dramatic downregulation of BCR-regulated genes [32, 33]. Most research available to date has focused on the effects of ibrutinib and idelalisib on the malignant B cell compartment, whereas the impact of these drugs on healthy B-cells and humoral immunity remains relatively less studied.

Ibrutinib effects on B cells

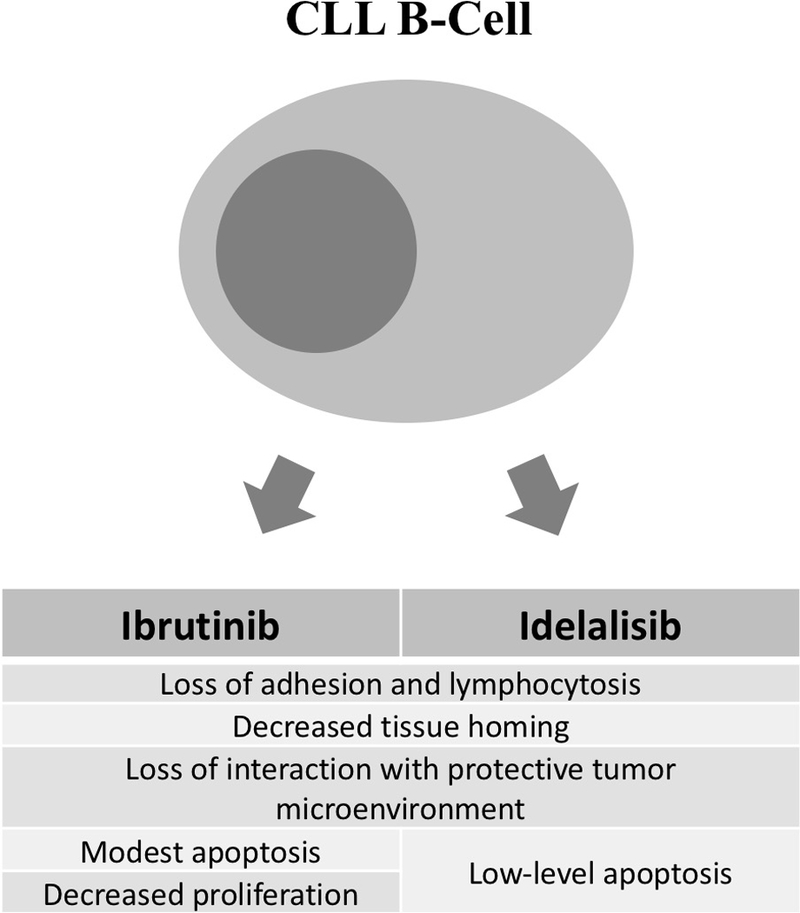

BTK is critical for B-cell development and immunoglobulin synthesis. Patients with X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA), caused by loss-of-function germline mutations in BTK, lack mature B cells, have severely depressed immunoglobulin levels, and suffer from recurrent infections. Ibrutinib, which irreversibly inhibits BTK, exerts multiple effects on malignant CLL B cells, including (i) impairment of cell adhesion leading to transient lymphocytosis [34, 35], (ii) disruption of communication with the tumor-sustaining microenvironment [35], (iii) modest induction of apoptosis [36] and (iv) decreased cell proliferation (Figure Figure 1) [32, 37].

Figure 1.

Summary of effects of ibrutinib and idelalisib on CLL B-Cells.

In contrast, ibrutinib does not recapitulate the severe B-cell impairment caused by genetic inactivation of BTK. Normal B cells derived from healthy volunteers have lower levels of BTK mRNA and BTK protein expression and are less vulnerable to ibrutinib mediated apoptosis than CLL cells in vitro [36]. Surprisingly, aspects of humoral immunity appear to be positively affected by ibrutinib therapy. A consistent increase in IgA has been observed across clinical trials of ibrutinib [6, 12]. The change in IgA appears to be clinically relevant – in a phase 2 study, patients with greater improvements in IgA developed fewer infections [38]. It is important to note however that although there was evidence of recovery of normal polyclonal B cells, they remained abnormal in number and subset composition. Furthermore, CLL patients on ibrutinib therapy can mount antibody responses to influenza vaccination, albeit the rate of detectable titers is less than in healthy individuals, but comparable to past reports on vaccine responses in CLL patients not treated with ibrutinib [39]. Influenza is a unique vaccine because it is given annually to patients who may have preexisting immunity from prior exposure or vaccination. Immunization against influenza could therefore trigger an anamnestic immune response rather than the development of de novo immunity. The non-malignant B-cell immune repertoire remains stable during ibrutinib therapy, suggesting the pool of antigen-experienced and antigen-naïve B cells are unaffected by treatment [40]. However, additional studies are required to investigate the immune response against neoantigens in patients on ibrutinib.

Idelalisib effects on B cells

The major effects of idelalisib on CLL B cells include (i) impairment of cell adhesion leading to transient lymphocytosis [12, 41] and (ii) loss of tumor protective microenvironment leading to induction of apoptosis (less pronounced than with ibrutinib) (Figure Figure 1) [42].

PI3Kδ expression levels are comparable across healthy as well as CLL B cells, however PI3K activity is higher in CLL B cells [42, 43]. Similar to effects observed with ibrutinib, normal B cells appeared to be less susceptible to idelalisib induced apoptosis compared to CLL B cells in vitro, possibly related to higher PI3Kδ activity in CLL B cells [42]. In terms of humoral immunity, idelalisib does not appear to impact serum immunoglobulin levels [41]. Recently, idelalisib was shown to increase somatic hypermutation and genomic instability via upregulation of B-cell specific activation-induced cytidine deaminase in normal and malignant B cells [44]. The clinical implications of this finding are currently unknown.

T cells

Tumor immune surveillance depends on a coordinated Th1-cell response that promotes cytotoxicity against emerging cancer cells. In CLL, the T-cell compartment is defective, fostering an environment that is both immunosuppressive and pro-tumor. The major T-cell abnormalities in CLL include skewing away from a Th1 dominant response towards a Th2 response, impaired immune synapse formation and chronic activation of T cells leading to pseudoexhaustion [45, 46, 47].

Ibrutinib effects on T cells

Clinically relevant doses of ibrutinib irreversibly inhibit interleukin-2-inducible kinase (ITK), a member of the Tec family kinases that are involved in the T-cell receptor signaling pathway [48, 49]. Most studies report a decrease in the number of circulating T cells during ibrutinib therapy, which appears to disrupt the crosstalk between CLL and T-cells [45, 50, 51]. In vitro and murine models have shown that while Th2 cells depend on ITK for TCR signal transduction, Th1 cells can be continuously activated in an ITK independent fashion via redundant resting lymphocyte kinase (RLK). Ibrutinib mediated ITK inhibition depletes Th2 T-cell signaling and polarizes T cells towards a Th1 predominant phenotype [48, 52]. This Th1 polarization is accompanied by an increase in Th1-mediated cytokines (IFN-γ) while Th2-mediated cytokines (IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α) are significantly reduced [36, 45, 48, 53]. It is noteworthy that conflicting data exists from ibrutinib-treated patients. Plasma levels of both Th1 and Th2 cytokines decreased during treatment with ibrutinib, while the ratio of these cytokines did not significantly change [51]. A different study found that the production of Th1 and Th2 cytokines after ex vivo stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells were not affected by ibrutinib therapy [54]. The effect of ibrutinib on the differentiation of IL-17 producing Th17 cells remains unclear. One study demonstrated an increase in Th17 cells ex vivo [54], whereas a decrease in Th17 cells was observed in vivo in CLL patients following ibrutinib administration [45]. In support of the latter, Th17 differentiation is markedly diminished in ITK-deficient mice [55]; and in vitro, ibrutinib inhibited differentiation of murine Th17 cells. Taken together, these data illustrate the difference between in vitro and in vivo effects of ibrutinib therapy on Th polarization and highlight the importance of correlative analyses in clinical trials.

Additionally, ibrutinib attenuates the expression of T cell activation and pseudoexhaustion markers (HLA-DR and CD39) on T cells, conceivably causing a shift toward healthier effector T cells [45]. The expression of immune checkpoint molecules, PD-1 and CTLA-4, on CD8+ T cells is also reduced in patients treated with acalabrutinib, a second generation selective BTK inhibitor that does not inhibit ITK, suggesting that at least some of the observed T-cell changes on ibrutinib are BTK-dependent [54]. In a study of 15 patients treated with ibrutinib alone or in combination with rituximab, treatment resulted in diversification of the T-cell receptor repertoire, which was associated with fewer infections and more complete remissions. However, interpretation of these data is limited by the small sample size and heterogeneous treatment administered [51].

Overall, ibrutinib mitigates immune dysregulation induced by CLL by affecting the polarization, signaling, receptor repertoire and cytokine secretion of T cells. Indeed, ibrutinib enhanced ex vivo expansion, in vivo proliferation, and clinical activity of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy for CLL [56]. The addition of ibrutinib to an anti-PD-L1 antibody also enhanced tumor shrinkage in mice bearing ibrutinib-resistant lymphoma, breast, and colon cancer [57]. Anti-PD1 blockade with pembrolizumab induced a clinical response in 4 of 6 patients (66%) with Richter’s transformation and prior exposure to ibrutinib. The median OS after 11 months of follow-up was not yet reached compared to an expected OS of 4 months using standard chemotherapy in Richter’s transformation of CLL previously treated with ibrutinib [58]. The in vitro activity of T-cell engaging CD19/CD3 bispecific antibodies against primary CLL cells from ibrutinib-treated patients is also better than the activity against treatment naïve samples [59]. Clinical trials investigating the combination of immunotherapy agents with ibrutinib in CLL are currently ongoing.

Idelalisib effects on T cells

Idelalisib does not appear to have a direct cytotoxic effect on T cells [42]. The absolute number of T helper cells or cytotoxic T cells in the peripheral blood did not significantly change during idelalisib treatment among clinical trial patients [41]. In terms of the influence on cytokine production, idelalisib seems to have an effect akin to ibrutinib in which it causes a decrease in the secretion of Th2 mediated inflammatory cytokines such as IL6, IL10, TNFα, as well as CD40L in vitro [42].

To address immune-related toxicities related to idelalisib use, there has been a focus on its effect on Treg cells. In PI3Kδ inactivated mice inoculated with various solid tumor cancer cells, a decrease in Treg function allowed for a CD8+ T-cell mediated cytotoxic response that caused tumor shrinkage [60]. One potential consequence of decreased Treg function is autoimmunity and immune related adverse effects. PI3Kδ inactivated mice are prone to develop potentially fatal autoimmune colitis [61, 62]. In humans, idelalisib is known to induce immune-related colitis, rash and hepatotoxicity. In patients experiencing idelalisib-induced hepatotoxicity, the number of peripheral blood Treg cells were lower compared to patients who did not experience hepatotoxicity [30]. Additionally, histopathologic analysis of human subjects with idelalisib-associated colitis showed an increase in infiltrating CD8+ T-cells, reminiscent of GvHD [63].

In summary, idelalisib decreases the production of Th2-associated inflammatory cytokines and blunts Treg function, promoting a CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell response. The net effect may be improved anti-tumor immunity at the cost of more immune related adverse effects.

Myeloid compartment

Myeloid cells, in particular tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) and myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are important in the pathogenesis of CLL [64, 65]. In vitro, TAMs support the survival of CLL cells by cell-cell contact and the secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines [66, 67]. MDSCs are immunosuppressive cells that are found at increased frequency in CLL patients compared to healthy individuals and are associated with shorter lymphocyte doubling time [68, 69, 70]. Both TAMs and MDSCs impair tumor immune surveillance via expansion of Treg cells and suppression of T-cell activation in CLL [64, 68, 71].

Ibrutinib effects on myeloid cells

Studies in mice have shown that BTK regulates the differentiation, function, and migration of myeloid cells [72, 73]. Neutrophils from patients with XLA are more susceptible to apoptosis due to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species [74]. These findings suggest that despite lower expression levels of PI3Kδ in myeloid cells compared to lymphocytes [75], BTK-inhibition may exert independent effects on myeloid cells. In patients with CLL, ibrutinib disrupts direct cell-cell contact between macrophages and tumor cells in the bone marrow via decreased production of CLL cell- and macrophage derived chemokines (e.g. CCL3, CCL4, CXCL12 and CXCL13) [45, 76, 77]. In considering combination therapies with ibrutinib and anti-CD20 antibody, ibrutinib inhibits antibody-dependent phagocytosis of CLL cells by macrophages and polymorphonuclear cells, as well as antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity and, through downregulation of CD20, complement-dependent cytotoxicity [78, 79, 80]. Ibrutinib may also affect macrophage function by impairing of Fcγ receptor function, thereby decreasing in Fcγ receptor mediated cytokine production [81].

Supplementary data on the effects of ibrutinib in myeloid cells is available in solid tumor mouse models. Ibrutinib treatment shifted macrophages toward a Th1-supportive phenotype and increased cytotoxic T-cell tumor infiltration in mice with pancreatic cancer [82]. Myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) suppress anti-tumor immunity and contribute to tumor progression. The function and frequency of MDSCs were reduced in solid tumor-bearing mice treated with ibrutinib [83]. However, these findings stand in contrast with earlier work showing that MDSCs counts were not affected by ibrutinib in mice with solid tumors [57]. Mouse models have also provided conflicting data regarding the importance of BTK and TEC in the survival and expansion of macrophages [84, 85].

Idelalisib effects on myeloid cells

Data about the effects of idelalisib on the myeloid compartment are scarce. To a lesser extent than ibrutinib, idelalisib inhibits multiple facets of antibody-mediated immune response, including antibody-dependent phagocytosis [78]. CLL cells treated with idelalisib in vitro also secrete less chemokines, CCL3 and CCL4, which may reduce the recruitment of macrophages to the tumor microenvironment [33]. In addition, PI3Kδ inactivation decreases the number of MDSCs in a murine model of breast cancer. Whether and how idelalisib affects MDSCs has not been described [60].

Conclusion

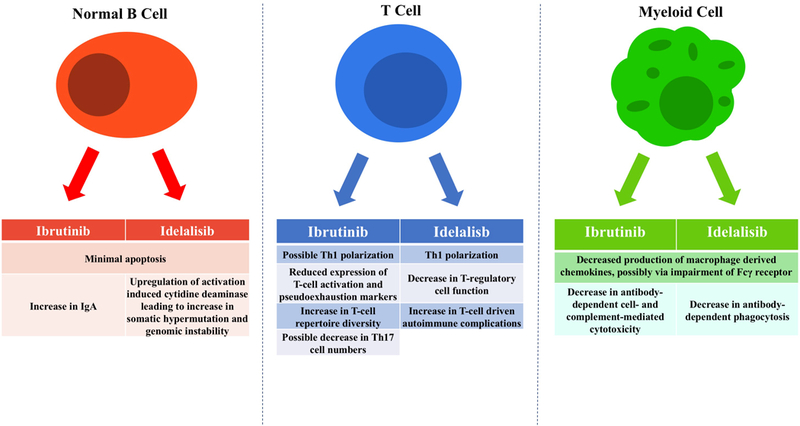

With widespread use of B-cell receptor signaling inhibitors, it is becoming clear that these agents not only target tumor cells, but also more broadly impact the immune system. Ibrutinib and idelalisib disrupt support signals from the tumor microenvironment to CLL cells (Figure 2). The immune dysfunction associated with CLL appears to be partially improved with ibrutinib. In contrast, idelalisib inhibits Treg cells resulting in significant autoimmune organ complications. Increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections remains an issue, in particular with idelalisib; continued vigilance for opportunistic infections in patients on chronic therapy with BTK inhibitors is warranted. As combination strategies are being investigated to eradicate CLL, it will be important to balance synergistic effects against tumor cells with the interference with host immunity and the ensuing risk of autoimmune and infectious complications.

Figure 2.

Summary of effects of ibrutinib and idelalisib on B cells,T cells and myeloid cells.

Table.

Infectious Complications with Ibrutinib, Idelalisib and Chemoimmunotherapy.

| Ibrutinib | Idelalisib plus anti-CD1220 antibody | Chemo- immunotherapy |

Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia | Treatment naïve 4–6% [8, 9] | Treatment naïve 19% [13] | Treatment naïve 9–11% [1] | |

| Relapsed disease 6–12% [6] | Relapsed disease 8–13% [12, 81] | Relapsed disease 5–13% [4, 5] | ||

| Pneumocystis Jiroveci Pneumonia | 5 case reports of grade ≤ 2 [17] | 2–3% [18] | PJP prophylaxis recommended with ibrutinib treatment | |

| Cytomegalovirus | 1 case report [23] | Idelalisib combination trials were halted due to fatal PJP and CMV infections [14] | Antiviral prophylaxis recommended with ibrutinib treatment | |

| Aspergillus | 3 case reports of aspergillus brain abscesses [19] | Increased risk of CNS and/or lung infection observed in primary CNS lymphoma with ibrutinib +/− chemotherapy and steroids |

Acknowledgements

The authors are supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NHLBI.

Funding: The authors are supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NHLBI.

Footnotes

Disclosures of Interest:

Adrian Wiestner received research support from Pharmacyclis LLC, and Abbvie company and Acerta Pharma. The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, et al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010. October 2;376(9747):1164–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61381-5. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eichhorst B, Fink AM, Bahlo J, et al. First-line chemoimmunotherapy with bendamustine and rituximab versus fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab in patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL10): an international, open-label, randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016. July;17(7):928–42. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30051-1. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keating MJ, O’Brien S, Albitar M, et al. Early results of a chemoimmunotherapy regimen of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab as initial therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2005. June 20;23(18):4079–88. doi: 10.1200/jco.2005.12.051. PubMed PMID: ; eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badoux XC, Keating MJ, Wang X, et al. Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab chemoimmunotherapy is highly effective treatment for relapsed patients with CLL. Blood. 2011. March 17;117(11):3016–24. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-304683. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4123386. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robak T, Dmoszynska A, Solal-Celigny P, et al. Rituximab plus fludarabine and cyclophosphamide prolongs progression-free survival compared with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide alone in previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010. April 01;28(10):1756–65. doi: 10.1200/jco.2009.26.4556. PubMed PMID: ; eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2013. July 04;369(1):32–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215637. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3772525. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun C, Tian X, Lee YS, et al. Partial reconstitution of humoral immunity and fewer infections in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib. Blood. 2015. November 05;126(19):2213–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-04-639203. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4635117. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burger JA, Tedeschi A, Barr PM, et al. Ibrutinib as Initial Therapy for Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015. December 17;373(25):2425–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509388. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farooqui MZ, Valdez J, Martyr S, et al. Ibrutinib for previously untreated and relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with TP53 aberrations: a phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015. February;16(2):169–76. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(14)71182-9. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4342187. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jou ST, Carpino N, Takahashi Y, et al. Essential, nonredundant role for the phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110delta in signaling by the B-cell receptor complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2002. December;22(24):8580–91. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC139888. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coutre SE, Furman RR, Sharman JP. Second interim analysis of a phase 3 study evaluating idelalisib and rituximab for relapsed CLL. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:5s (abstr 7012). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furman RR, Sharman JP, Coutre SE, et al. Idelalisib and rituximab in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2014. March 13;370(11):997–1007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315226. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4161365. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Brien SM, Lamanna N, Kipps TJ, et al. A phase 2 study of idelalisib plus rituximab in treatment-naive older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2015. December 17;126(25):2686–94. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-630947. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4732760. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Food & Drug Administration. FDA Alerts Healthcare Professionals About Clinical Trials with Zydelig (idelalisib) in Combination with other Cancer Medicines 2016 [updated 03/14/2016;04/12/2017]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm490618.htm

- 15.Cheah CY, Fowler NH. Idelalisib in the management of lymphoma. Blood. 2016. July 21;128(3):331–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-02-702761. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5161010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zelenetz AD, Barrientos JC, Brown JR, et al. Idelalisib or placebo in combination with bendamustine and rituximab in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: interim results from a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017. March;18(3):297–311. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(16)30671-4. PubMed PMID: ; eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sehn LH, Hallek M, Jurczak W. A Retrospective Analysis of Pneumocystis Jirovecii Pneumonia Infection in Patients Receiving Idelalisib in Clinical Trials. American Society of Hematology 58th Annual Meeting, San Diego, CA 2016:abstr 3705. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahn IE, Jerussi T, Farooqui M, et al. Atypical Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in previously untreated patients with CLL on single-agent ibrutinib. Blood. 2016. October 13;128(15):1940–1943. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-06-722991. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5064717. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruchlemer R, Ben Ami R, Lachish T. Ibrutinib for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2016. April 21;374(16):1593–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1600328#SA3. PubMed PMID: ; eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lionakis MS, Dunleavy K, Roschewski M, et al. Inhibition of B Cell Receptor Signaling by Ibrutinib in Primary CNS Lymphoma. Cancer Cell. 2017. June 12;31(6):833–843.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.04.012. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5571650. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giridhar KV, Shanafelt T, Tosh PK, et al. Disseminated herpes zoster in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients treated with B-cell receptor pathway inhibitors. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2016. December 14:1–4. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2016.1267352. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Jesus Ngoma P, Kabamba B, Dahlqvist G, et al. Occult HBV reactivation induced by ibrutinib treatment: a case report. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2015. December;78(4):424–6. PubMed PMID: ; eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan KL, Lokan J, Tam CS, et al. Central nervous system immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome after ibrutinib therapy for Richter transformation. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2017. January;58(1):207–210. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2016.1179298. PubMed PMID: ; eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dearden C, Wade R, Else M, et al. The prognostic significance of a positive direct antiglobulin test in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a beneficial effect of the combination of fludarabine and cyclophosphamide on the incidence of hemolytic anemia. Blood. 2008. February 15;111(4):1820–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-101303. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zent CS, Ding W, Reinalda MS, et al. Autoimmune cytopenia in chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma: changes in clinical presentation and prognosis. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2009. August;50(8):1261–8. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3917557. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maura F, Visco C, Falisi E, et al. B-cell receptor configuration and adverse cytogenetics are associated with autoimmune hemolytic anemia in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2013. January;88(1):32–6. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23342. PubMed PMID: ; eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiss RB, Freiman J, Kweder SL, et al. Hemolytic anemia after fludarabine therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1998. May;16(5):1885–9. doi: 10.1200/jco.1998.16.5.1885. PubMed PMID: ; eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vitale C, Ahn IE, Sivina M, et al. Autoimmune cytopenias in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib. Haematologica. 2016. June;101(6):e254–8. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.138289. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5013951. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Molica S, Levato L, Mirabelli R. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia, autoimmune hemolytic anemia and ibrutinib: a case report and review of the literature. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2016;57(3):735–7. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2015.1071489. PubMed PMID: ; eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lampson BL, Kasar SN, Matos TR, et al. Idelalisib given front-line for treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia causes frequent immune-mediated hepatotoxicity. Blood. 2016. July 14;128(2):195–203. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-707133. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4946200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burris HA 3rd, Flinn IW, Patel MR, et al. Umbralisib, a novel PI3Kdelta and casein kinase-1epsilon inhibitor, in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and lymphoma: an open-label, phase 1, dose-escalation, first-in-human study. Lancet Oncol. 2018. February 20. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30082-2. PubMed PMID: 29475723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herman SE, Mustafa RZ, Gyamfi JA, et al. Ibrutinib inhibits BCR and NF-kappaB signaling and reduces tumor proliferation in tissue-resident cells of patients with CLL. Blood. 2014. May 22;123(21):3286–95. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-548610. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4046423. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoellenriegel J, Meadows SA, Sivina M, et al. The phosphoinositide 3’-kinase delta inhibitor, CAL-101, inhibits B-cell receptor signaling and chemokine networks in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2011. September 29;118(13):3603–12. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-352492. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4916562. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herman SE, Mustafa RZ, Jones J, et al. Treatment with Ibrutinib Inhibits BTK- and VLA-4-Dependent Adhesion of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Cells In Vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2015. October 15;21(20):4642–51. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-15-0781. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4609275. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Rooij MF, Kuil A, Geest CR, et al. The clinically active BTK inhibitor PCI-32765 targets B-cell receptor- and chemokine-controlled adhesion and migration in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2012. March 15;119(11):2590–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-390989. PubMed PMID: ; eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herman SE, Gordon AL, Hertlein E, et al. Bruton tyrosine kinase represents a promising therapeutic target for treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and is effectively targeted by PCI-32765. Blood. 2011. June 9;117(23):6287–96. doi: blood-2011–01-328484 [pii] 10.1182/blood-2011-01-328484. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3122947. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng S, Ma J, Guo A, et al. BTK inhibition targets in vivo CLL proliferation through its effects on B-cell receptor signaling activity. Leukemia. 2014. March;28(3):649–57. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.358. PubMed PMID: ; eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun C, Wiestner A. Prognosis and therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and small lymphocytic lymphoma. Cancer Treat Res. 2015;165:147–75. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-13150-4_6. PubMed PMID: ; eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun C, Gao J, Couzens L, et al. Seasonal Influenza Vaccination in Patients With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Treated With Ibrutinib. JAMA oncology. 2016. August 11. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.2437. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schliffke S, Sivina M, Kim E, et al. Dynamic changes of the normal B lymphocyte repertoire in CLL in response to ibrutinib or FCR chemo-immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2018;0(0):e1417720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown JR, Byrd JC, Coutre SE, et al. Idelalisib, an inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase p110delta, for relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2014. May 29;123(22):3390–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-535047. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4123414. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Herman SE, Gordon AL, Wagner AJ, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-delta inhibitor CAL-101 shows promising preclinical activity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia by antagonizing intrinsic and extrinsic cellular survival signals. Blood. 2010. September 23;116(12):2078–88. doi: blood-2010–02-271171 [pii] 10.1182/blood-2010-02-271171. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2951855. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ringshausen I, Schneller F, Bogner C, et al. Constitutively activated phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI-3K) is involved in the defect of apoptosis in B-CLL: association with protein kinase Cdelta. Blood. 2002. November 15;100(10):3741–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0539. PubMed PMID: ; eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Compagno M, Wang Q, Pighi C, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase delta blockade increases genomic instability in B cells. Nature. 2017. February 15. doi: 10.1038/nature21406. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Niemann CU, Herman SE, Maric I, et al. Disruption of in vivo chronic lymphocytic leukemia tumor-microenvironment interactions by ibrutinib - findings from an investigator-initiated phase II study. Clin Cancer Res. 2016. April 1;22(7):1572–82. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1965. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4818677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riches JC, Davies JK, McClanahan F, et al. T cells from CLL patients exhibit features of T-cell exhaustion but retain capacity for cytokine production. Blood. 2013. February 28;121(9):1612–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-457531. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3587324. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramsay AG, Johnson AJ, Lee AM, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia T cells show impaired immunological synapse formation that can be reversed with an immunomodulating drug. J Clin Invest. 2008. July;118(7):2427–37. doi: 10.1172/jci35017. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2423865. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dubovsky JA, Beckwith KA, Natarajan G, et al. Ibrutinib is an irreversible molecular inhibitor of ITK driving a Th1-selective pressure in T lymphocytes. Blood. 2013. October 10;122(15):2539–49. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-507947. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3795457. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berg LJ, Finkelstein LD, Lucas JA, et al. Tec family kinases in T lymphocyte development and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:549–600. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104743. PubMed PMID: ; eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burger JA, Keating MJ, Wierda WG, et al. Safety and activity of ibrutinib plus rituximab for patients with high-risk chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2014. September;15(10):1090–9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70335-3. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4174348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yin Q, Sivina M, Robins H, et al. Ibrutinib Therapy Increases T Cell Repertoire Diversity in Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. J Immunol. 2017. February 15;198(4):1740–1747. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601190. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5296363. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kashiwakura J, Suzuki N, Nagafuchi H, et al. Txk, a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase of the Tec family, is expressed in T helper type 1 cells and regulates interferon gamma production in human T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1999. October 18;190(8):1147–54. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2195662. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ruella M, Kenderian SS, Shestova O, et al. Kinase inhibitor ibrutinib to prevent cytokine-release syndrome after anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cells for B-cell neoplasms. Leukemia. 2017. January;31(1):246–248. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.262. PubMed PMID: ; eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Long M, Beckwith K, Do P, et al. Ibrutinib treatment improves T cell number and function in CLL patients. J Clin Invest. 2017. August 01;127(8):3052–3064. doi: 10.1172/jci89756. PubMed PMID: ; eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gomez-Rodriguez J, Wohlfert EA, Handon R, et al. Itk-mediated integration of T cell receptor and cytokine signaling regulates the balance between Th17 and regulatory T cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2014. March 10;211(3):529–43. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131459. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3949578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fraietta JA, Beckwith KA, Patel PR, et al. Ibrutinib enhances chimeric antigen receptor T-cell engraftment and efficacy in leukemia. Blood. 2016. March 03;127(9):1117–27. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-11-679134. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4778162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sagiv-Barfi I, Kohrt HE, Czerwinski DK, et al. Therapeutic antitumor immunity by checkpoint blockade is enhanced by ibrutinib, an inhibitor of both BTK and ITK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015. March 03;112(9):E966–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500712112. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4352777. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ding W, LaPlant BR, Call TG, et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with CLL and Richter transformation or with relapsed CLL. Blood. 2017. June 29;129(26):3419–3427. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-02-765685. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5492091. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Robinson HR, Qi J, Baskar S, et al. Activity of CD19/CD3 Bispecific Antibodies in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. American Society of Hematology 59th Annual Meeting; Atlanta, GA2017. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ali K, Soond DR, Pineiro R, et al. Inactivation of PI(3)K p110delta breaks regulatory T-cell-mediated immune tolerance to cancer. Nature. 2014. June 19;510(7505):407–411. doi: 10.1038/nature13444. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4501086. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Okkenhaug K, Bilancio A, Farjot G, et al. Impaired B and T cell antigen receptor signaling in p110delta PI 3-kinase mutant mice. Science. 2002. August 09;297(5583):1031–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1073560. PubMed PMID: ; eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Uno JK, Rao KN, Matsuoka K, et al. Altered macrophage function contributes to colitis in mice defective in the phosphoinositide-3 kinase subunit p110delta. Gastroenterology. 2010. November;139(5):1642–53, 1653–e1–6.. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.008. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2967619. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weidner AS, Panarelli NC, Geyer JT, et al. Idelalisib-associated Colitis: Histologic Findings in 14 Patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015. December;39(12):1661–7. doi: 10.1097/pas.0000000000000522. PubMed PMID: ; eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hanna BS, McClanahan F, Yazdanparast H, et al. Depletion of CLL-associated patrolling monocytes and macrophages controls disease development and repairs immune dysfunction in vivo. Leukemia. 2016. March;30(3):570–9. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.305. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nguyen PH, Fedorchenko O, Rosen N, et al. LYN Kinase in the Tumor Microenvironment Is Essential for the Progression of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2016. October 10;30(4):610–622. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.09.007. PubMed PMID: ; eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Herman SE, Wiestner A. Preclinical modeling of novel therapeutics in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the tools of the trade. Semin Oncol. 2016. April;43(2):222–32. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2016.02.007. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4856050. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Burger JA, Tsukada N, Burger M, et al. Blood-derived nurse-like cells protect chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells from spontaneous apoptosis through stromal cell-derived factor-1. Blood. 2000. October 15;96(8):2655–63. PubMed PMID: ; eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nagaraj S, Youn JI, Gabrilovich DI. Reciprocal relationship between myeloid-derived suppressor cells and T cells. J Immunol. 2013. July 01;191(1):17–23. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300654. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3694485. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jitschin R, Braun M, Buttner M, et al. CLL-cells induce IDOhi CD14+HLA-DRlo myeloid-derived suppressor cells that inhibit T-cell responses and promote TRegs. Blood. 2014. July 31;124(5):750–60. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-546416. PubMed PMID: ; eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gustafson MP, Abraham RS, Lin Y, et al. Association of an increased frequency of CD14+ HLA-DR lo/neg monocytes with decreased time to progression in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL). Br J Haematol. 2012. March;156(5):674–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08902.x. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3433277. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Giannoni P, Pietra G, Travaini G, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia nurse-like cells express hepatocyte growth factor receptor (c-MET) and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and display features of immunosuppressive type 2 skewed macrophages. Haematologica. 2014. June;99(6):1078–87. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.091405. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4040912. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fiedler K, Sindrilaru A, Terszowski G, et al. Neutrophil development and function critically depend on Bruton tyrosine kinase in a mouse model of X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Blood. 2011. January 27;117(4):1329–1339. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281170. PubMed PMID: WOS:; English. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mueller H, Stadtmann A, Van Aken H, et al. Tyrosine kinase Btk regulates E-selectin-mediated integrin activation and neutrophil recruitment by controlling phospholipase C (PLC) gamma2 and PI3Kgamma pathways. Blood. 2010. April 15;115(15):3118–27. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-254185. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2858472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Honda F, Kano H, Kanegane H, et al. The kinase Btk negatively regulates the production of reactive oxygen species and stimulation-induced apoptosis in human neutrophils. Nature immunology. 2012. February 26;13(4):369–78. doi: 10.1038/ni.2234. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kok K, Nock GE, Verrall EA, et al. Regulation of p110delta PI 3-kinase gene expression. PLoS One. 2009;4(4):e5145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005145. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2663053. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ponader S, Chen SS, Buggy JJ, et al. The Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor PCI-32765 thwarts chronic lymphocytic leukemia cell survival and tissue homing in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2012. February 02;119(5):1182–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-386417. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4916557. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ping L, Ding N, Shi Y, et al. The Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib exerts immunomodulatory effects through regulation of tumor-infiltrating macrophages. Oncotarget. 2017. June 13;8(24):39218–39229. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16836. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5503608. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Da Roit F, Engelberts PJ, Taylor RP, et al. Ibrutinib interferes with the cell-mediated anti-tumor activities of therapeutic CD20 antibodies: implications for combination therapy. Haematologica. 2015. January;100(1):77–86. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.107011haematol.2014.107011. [pii] PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4281316. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Skarzynski M, Niemann CU, Lee YS, et al. Interactions between Ibrutinib and Anti-CD20 Antibodies: Competing Effects on the Outcome of Combination Therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2016. January 1;22(1):86–95. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1304. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4703510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kohrt HE, Sagiv-Barfi I, Rafiq S, et al. Ibrutinib (PCI-32765) Antagonizes Rituximab-Dependent NK-Cell Mediated Cytotoxicity. Blood. 2013. October 21, 2013;122(21):373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ren L, Campbell A, Fang H, et al. Analysis of the Effects of the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (Btk) Inhibitor Ibrutinib on Monocyte Fcgamma Receptor (FcgammaR) Function. J Biol Chem. 2016. February 5;291(6):3043–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.687251. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4742765. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gunderson AJKM, Coussens LM, et al. Bruton Tyrosine Kinase-Dependent Immune Cell Cross-talk Drives Pancreas Cancer. Cancer Discovery. 2016;6((3)):270–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stiff A, Trikha P, Wesolowski R, et al. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Express Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase and Can Be Depleted in Tumor-Bearing Hosts by Ibrutinib Treatment. Cancer Res. 2016. April 15;76(8):2125–36. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-15-1490. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4873459. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McClanahan F, Reiff SD, Guinn D. Exploring the Functional Relevance of BTK Beyond Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) Cells: BTK Expression in Non-Malignant Immune Cells of the Microenvironment Mediates CLL Development and Progression In Vivo. American Society of Hematology 58th Annual Meeting; San Diego, CA2016. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Melcher M, Unger B, Schmidt U, et al. Essential roles for the Tec family kinases Tec and Btk in M-CSF receptor signaling pathways that regulate macrophage survival. J Immunol. 2008. June 15;180(12):8048–56. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3001193. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]