Abstract

Purpose

Cecal appendix is the terminal part of cecum and is characteristic of rabbit, among domestic animals. The purpose of this work is to evaluate its morphology upon ultrasound.

Methods

A prospective study was planned for the duration of approximately 1 year. Rabbits presented in the study period for abdominal ultrasound with no clinically evident alterations of the gastrointestinal tract were eligible for inclusion in the study. Abdominal ultrasound was performed under manual restrain with a high frequency linear probe (8–18 MHz).

Results

Cecal appendix was visualized in 40/42 rabbits (95.2%) with median or left paramedian views. The wall appeared multilayered in accordance with normal bowel anatomy, and the luminal content showed in all cases an alimentary pattern. Measurement of appendix wall thickness (AWT) was possible in all 40 rabbits in which the appendix was visualized while measurement of the appendix diameter (AD) was possible in 39 rabbits. Reference intervals for AWT were 1.1–2.1 mm, and for AD were 3.9–8.8 mm. There was a negative correlation between age and AWT (r = − 0.35, P = 0.027) and a moderate positive correlation between AWT and AD (r = 0.71, P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Cecal appendix is recognizable via ultrasound in the vast majority of rabbits. We describe the normal morphological aspect of the appendix and we provide reference intervals for wall thickness and diameter of the appendix, in order to aid in the diagnosis of disorders of the appendix. The negative correlation between age and AWT indicates lower values of AWT associated with increasing age that could represent the physiological decrease in the immunitary function of the appendix in aged rabbits.

Keywords: Appendix; Rabbit, ultrasound; Appendicitis; Gastrointestinal stasis

Sommario

Scopo

L’appendice cecale rappresenta la parte terminale del cieco e tra gli animali domestici è caratteristica del coniglio. Lo scopo di questo lavoro è di valutare la sua morfologia in ecografia.

Metodi

È stato pianificato uno studio prospettico della durata di circa 1 anno. I conigli presentati per ecografia addominale nel periodo dello studio e senza alterazioni cliniche evidenti dell’apparato gastro-enterico sono stati inclusi. L’ecografia addominale è stata effettuata tramite contenimento manuale utilizzando una sonda lineare ad elevata frequenza (8-18 MHz).

Risultati

L’appendice cecale è stata visualizzata in 40/42 (95,2%) animali utilizzando scansioni mediane e paramediane sinistre. La parete appare pluristratificata in accordo con la normale anatomia intestinale ed il contenuto luminale è rappresentato in tutti i casi da pattern alimentare. La misurazione dell’AWT è stata possibile in tutti i 40 conigli in cui l’appendice è stata visualizzata mentre la misurazione dell’AD è stata possibile in 39 conigli. Gli intervalli di riferimento per AWT sono stati di 1,1-2,1 mm e per l’AD di 3,9-8,8 mm. È stata evidenziata una correlazione negativa tra l’età e AWT (r = -0,35, P = 0,027) ed una moderata correlazione positiva tra AWT e AD (r = 0,71, P < 0,001).

Conclusioni

L’appendice cecale è un organo riconoscibile attraverso l’ecografia nella maggior parte dei conigli. Descriviamo l’aspetto morfologico dell’appendice e forniamo parametri di riferimento per lo spessore parietale e il diametro dell’appendice, con lo scopo di facilitare la diagnosi delle patologie dell’appendice. La correlazione negativa tra l’età e AWT indica valori più bassi di AWT associati all’aumento dell’età, che potrebbe rappresentare la diminuzione della funzione immunitaria dell’appendice nei conigli adulti.

Introduction

In rabbits, the gastrointestinal tract is composed of a relatively large stomach that has a well-developed cardiac sphincter that prevents vomiting and a pyloric area. The small intestine, divided in duodenum, jejunum and ileum, ends in a rounded structure unique to the rabbit called sacculus rotundus. The wall of the sacculus rotundus has abundant aggregations of lymphoid tissue in the lamina propria and submucosa. The rabbit cecum is very large and has a capacity roughly ten times that of the stomach, constituting around 40% of the total gastrointestinal tract [1]. The cecum ends with a cecal appendix, a thick-walled, blind-ended structure whose wall is rich in lymphoid tissue. The cecal appendix represents a site for the antibody diversification in young rabbits and has a secretory function of water and bicarbonate throughout the life of the animals. The cecum is followed by the colon, which originates from an area defined ampulla coli and is divided into proximal and distal colon by the fusus coli [2, 3].

The rabbit has been used as an experimental model to study acute appendicitis in humans. In these studies, surgical ligation of the appendix or the obstruction of the appendix obtained through the placement of a balloon catheter introduced via cecostomy induced ischemic necrosis or inflammatory changes of the organ. These modifications were studied for their similarity with spontaneous human appendicitis and to evaluate the response to medical or surgical treatment [4–6].

Recently, a case of appendicitis and sacculitis in a 9-month-old male rabbit, diagnosed by means of ultrasonography and computed tomography, has been reported [7].

Although a previous study reported ultrasonographic features and size of abdominal organs in healthy rabbits, including cecal appendix [8], it included a limited number of cases and no information about the diameter of the organ and the luminal content was reported.

The purpose of our work is to demonstrate that in normal condition morphological and structural features of the appendix are recognizable during basic abdominal ultrasonography and to provide reference size for appendix of gastrointestinal healthy rabbits.

Materials and methods

A prospective, reference interval, single-center study was planned for the duration of approximately 1 year (19/12/2016–12/12/2017). All the rabbits that were presented in the study period for abdominal ultrasound and had no history and no clinically evident alterations of the gastrointestinal tract were eligible for inclusion in the study. Rabbits included in the study had no ultrasonographic evidence of gastrointestinal tract disease. All the rabbits were client-owned animals. All animals underwent abdominal ultrasound examination performed with a GE logiq E9, equipped with a linear multifrequency hokey stick probe 8–18 MHz with a small parts optimized setting. The animals were prepared with trichotomy and application of a small quantity of alcohol and ultrasonographic gel. The rabbits were manually restrained for the duration of the ultrasonographic examination. A complete abdominal ultrasonographic exam was performed with the animal in both right and left lateral recumbency. When possible, the appendix was visualized in longitudinal and transversal views; wall measures were taken in longitudinal view because in the authors’ experience the visibility of the organ and repeatability of measures were higher. Measures were taken from the interface lumen-mucosal layer to the serosal one obtaining the wall thickness and from serosal to serosal layer obtaining the diameter of the organ (Fig. 1).

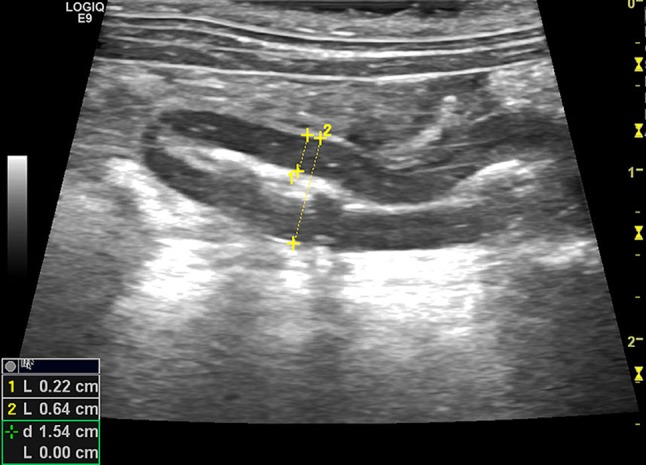

Fig. 1.

Rabbit, normal appendix, longitudinal view: mucous luminal pattern. Wall measure from lumen-mucosa interface to sierosal layer (measure 1). Measure of the appendix diameter (measure 2). The blind-ended appearance can be noticed (arrows)

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics were compiled for measured variables. Data were analyzed for normality by means of the Shapiro–Wilk test. In case appendix wall thickness (AWT) and appendix diameter (AD) were normally distributed, ninety percent reference intervals for the variables were provided. Difference in appendix parameters (AD, AWT) between male and female rabbits was evaluated by means of Student t test since the distribution was normal. Correlation between age and appendix parameters and between AD and AWT was evaluated by calculation of the Pearson r statistic. Data were analyzed using commercial software (SPSS statistics v22.0; IBM, Chicago, IL). Two tailed P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Population summary

A total of 42 pet rabbits were included in the study. The rabbits were of mixed breed, ranging between 0.5 and 2 kg in weight. Eighteen rabbits were males (9 neutered and 9 intact) and 24 females (17 neutered and 7 intact). The median age was 54 months (2–156).

Visualization and morphology of appendix

In two rabbits, it was not possible to identify cecal appendix. In the remaining 40 rabbits, the appendix was visualized and the ultrasonographic examination was allowed to study wall structure and luminal content. In all cases, the appendix was visualized through median and/or left paramedian views. The appendix was recognizable as a tubular structure with a rounded, closed end and a multilayered wall characteristic of the intestinal tract. In all cases, the luminal content had an alimentary pattern (Figs. 2, 3 and 4), and no appendix had evidence of fluid content. In one rabbit, the shadow generated from the luminal pattern limited visualization of the distal wall of the appendix prohibiting measurement of AD. Therefore, 40 rabbits had measurement of AWT and 39 rabbits had measurement of AD.

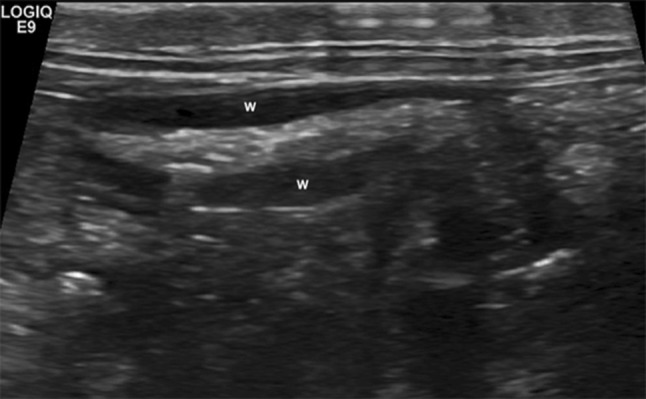

Fig. 2.

Rabbit, normal appendix: alimentary luminal pattern. The state of repletion can be variable and the wall (w) shows an attenuated echogenicity

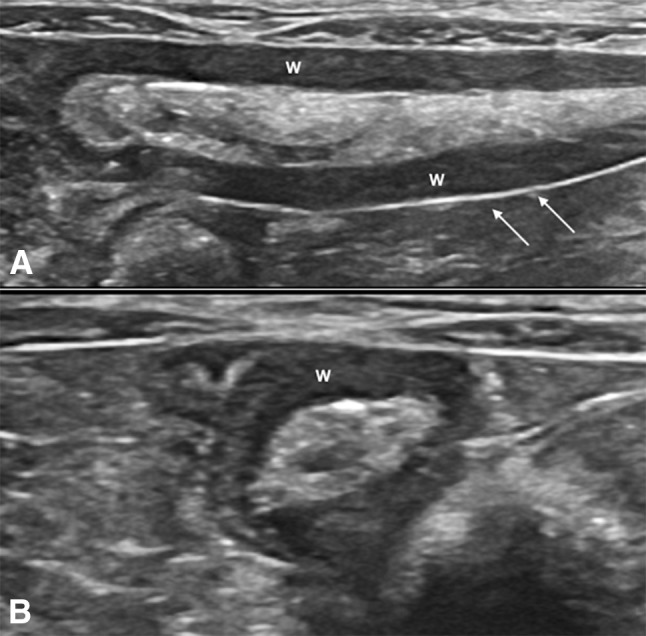

Fig. 3.

Rabbit, normal appendix in longitudinal (a) and transversal (b) views: alimentary luminal pattern. The state of repletion can be variable in normal conditions and the wall (w) shows an attenuated echogenicity, sierosa is visible as a hyper-echoic linear structure (arrows)

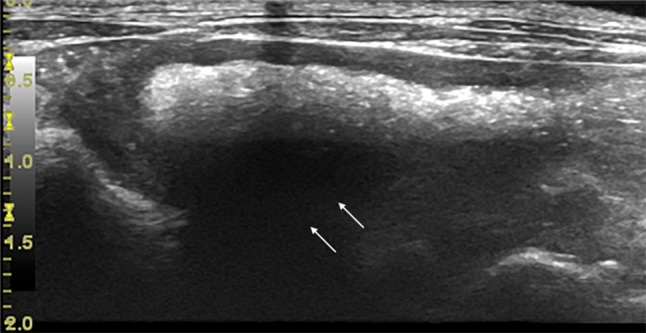

Fig. 4.

Rabbit, normal appendix in longitudinal view. In this case, the appendix shows a higher state of repletion compared to previous images and the luminal content creates a posterior acoustic shadow (arrows)

Reference ranges for appendix wall thickness and appendix diameter

Both AWT and AD were normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk: P = 0.58 and P = 0.91, respectively). On average, AWT measured 1.5 mm (SD: 0.3; range 0.8–2.2). Male had a mean AWT of 1.53 ± 0.29 mm and females of 1.48 ± 0.32 mm. The mean difference between male and female was 0.05 mm (95% CI − 0.14 to 0.25) and not statistically significant (P = 0.59). Reference intervals for AWT were 1.1 to 2.1 mm. The mean AD was 6.1 mm (SD: 1.4; range: 2.6–9.2). Male had a mean AD of 6.07 ± 1.39 mm and females of 0.07 ± 1.53 mm. The mean difference between male and female was − 0.004 mm (95% CI − 0.96–0.95) and not statistically significant (P = 0.99). Reference intervals for AD size were 3.9–8.8 mm. There was no correlation between age and AD (r = 0.01, P = 0.94) but there was a weak negative correlation between age and AWT (r = − 0.35, P = 0.027), indicating lower values of AWT associated with increasing age, and a moderate positive correlation between AWT and AD (r = 0.71, 95% CI 0.53–0.83; P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of measurements of appendix wall thickness (AWT) and appendix diameter (AD) obtained in 40 and 39 rabbits, respectively

| AWT (mm) | AD (mm) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 1.51 | 6.07 |

| Standard Deviation | .30 | 1.45 |

| Minimum | .80 | 2.60 |

| Maximum | 2.20 | 9.20 |

Both variables were normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk > 0.05)

Discussion

Gastrointestinal stasis is a common condition in rabbits; it is not related exclusively to pathologies of the gastrointestinal tract but could be the expression of several problems. As in other animals as dogs and cats, abdominal ultrasonography is an important evaluation in the clinical practice; it provides useful clinical and operative information in a non-invasive way. It consents to differentiate mechanical stasis to functional ones, allowing to detect foreign bodies or indirect signs of mechanical ileus, as segmental fluid or gas accumulation within the stomach or part of the intestinal tract, and to individuate signs of inflammatory bowel disease [3, 9, 10]. In our opinion, the evaluation of the appendix has always to be included in abdominal ultrasound, because pathologies of the organ are reported [7, 11]. In human medicine, the visualization of normal appendix on sonography is reported to appear advantageous in reducing the percentage of false-negative cases of appendicitis. Moreover, ultrasonography is considered a readily available, inexpensive, non-invasive test with a reported sensitivity of 80–94% in the detection of acute appendicitis [12] and it is the preferred imaging modality in pregnant woman and in children suspected of acute appendicitis, because radiation exposure is an important concern in managing this kind of patients [13, 14]. Considering published works in human and veterinary medicine and the authors’ experience, abdominal ultrasound probably can help to detect morphological changes that involve the wall structure and the luminal pattern in course of appendix diseases. This work wants to focus on the ultrasonographic features of the appendix in condition of normality; further studies are necessary to establish the ultrasonographic changes of the appendix in course of appendicitis. In the present study, we found a negative correlation between age and AWT. In young rabbits, the appendix represents an important site for development of the primary antibody repertoire. Although the rabbit appendix does not involute, it changes in appearance, possibly in function, and partially atrophies with age [15]. We suggest that probably lower values of AWT associated with increasing age could be related to the physiological decrease in the immunitary function of the appendix in aged rabbits.

Conclusions

Based on our study, cecal appendix is recognizable via ultrasound through median and/or left paramedian views in the vast majority of rabbits. We describe the normal morphological aspect of the appendix and we provide reference intervals for wall thickness and diameter, in order to aid in the diagnosis of disorders of the appendix. We found a weak negative correlation between age and AWT that suggests that lower values of AWT are associated with increasing age, hypothesis that has to be confirmed with further studies. We also found a moderate positive correlation between AD and AWT. We suspected that AD is positively related with the repletion state of the organ and that can be variable in the same individual. However, further research with multiple monitoring of the same rabbits at different times is required to prove this hypothesis. We also describe the normal luminal content of the appendix that in all cases was represented by the alimentary pattern.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution or practice at which the studies were conducted. This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Human and animal rights statement

All the described animal-related procedures were conducted according to the Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of September 22nd 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes (Art.1, Par.1, letter “b”), which does not require any approval by the competent Authorities.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Jenkins J. The veterinary clinics of North America. Exotic animal practice. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quesenberry KE, Carpenter JW (2012) Ferrets, rabbits and rodents. Clinical medicine and surgery, 3rd edn. Elsevier/Saunders, section 2

- 3.Selleri P, Di Girolamo T, Collarile T. Medicina e chirurgia degli animali esotici. MI Italia: Poletto Editore; 2017. pp. 386–387. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nunes FC, Silva AL. Acute ischemic appendicitis in rabbits: new model with histopathological study. Acta Cir Bras. 2005;20(5):399–404. doi: 10.1590/S0102-86502005000500011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pieper R, Kager L, Tidefeldt U. Obstruction of appendix vermiformis causing acute appendicitis. An experimental study in the rabbit. Acta Chir Scand. 1982;148(1):63–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simsek G, Servinc B, Onlu Y, Hasirci I, Kurku H, Karahan O. Effect of medical treatment on histological findings in rabbits with acute appendicitis. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2016;22(6):516–520. doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2016.79825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Longo Maurizio, Thierry Florence, Eatwell Kevin, Schwarz Tobias, del Pozo Jorge, Richardson Jenna. Ultrasound and computed tomography of sacculitis and appendicitis in a rabbit. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound. 2018;59(5):E56–E60. doi: 10.1111/vru.12602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banzato T, Bellini L, Contiero B, Selleri P, Zotti A. Abdominal ultrasound features and reference values in 21 health rabbits. Vet Rec. 2015;176:101. doi: 10.1136/vr.102657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penninck D, D’anjou MA. Atlas of small animal ultrasonography. 1. Ames IA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. p. 287. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baez JL, Hendrick MJ, Walker LM, Washabau RJ. Radiographic, ultrasonographic and endoscopic findings in cats with inflammatory bowel desease of the stomach and small intestine: 33 cases (1990–1997) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1999;215(3):349–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujiwara H, Uchida K, Takahashi M. Occurrence of granulomatous appendicitis in rabbits. Jikken Dobutsu. 1987;36:277–280. doi: 10.1538/expanim1978.36.3_277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rioux M. Sonographic detection of the normal and abnormal appendix. AJR. 1992;158:773–778. doi: 10.2214/ajr.158.4.1546592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kazemini A, Reza Keramati M, Fazeli MS, Keshvari A, Khaki S, Rahnemai-Azar A. Accuracy of ultrasonography in diagnosing acute appendicitis during pregnancy based on surgical findings. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2017;31:48. doi: 10.14196/mjiri.31.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sola R, Jr, Theut SB, Sinclair KA, Rivard DC, Johnson KM, Zhu H, St Peter SD, Shah SR. Standardized reporting of appendicitis-related findings improves reliability of ultrasound in diagnosing appendicitis in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53(5):984–987. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dusso JF, Obiakor H, Bach H, Anderson AO, Mage RG. A morphological and immunohistological study of the human and rabbit appendix for comparison with the avian bursa. Dev Comp Immunol. 2000;24:797–814. doi: 10.1016/S0145-305X(00)00033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]