Abstract

Microorganisms release a plethora of volatile secondary metabolites. Up to now, it has been widely accepted that these volatile organic compounds are produced and emitted as a final product by a single organism e.g. a bacterial cell. We questioned this commonly assumed perspective and hypothesized that in diversely colonized microbial communities, bacterial cells can passively interact by emitting precursors which non-enzymatically react to form the active final compound. This hypothesis was inspired by the discovery of the bacterial metabolite schleiferon A. This bactericidal volatile compound is formed by a non-enzymatic reaction between acetoin and 2-phenylethylamine. Both precursors are released by Staphylococcus schleiferi cells. In order to provide evidence for our hypothesis that these precursors could also be released by bacterial cells of different species, we simultaneously but separately cultivated Serratia plymuthica 4Rx13 and Staphylococcus delphini 20771 which held responsible for only one precursor necessary for schleiferon A formation, respectively. By mixing their headspace, we demonstrated that these two species were able to deliver the active principle schleiferon A. Such a joint formation of a volatile secondary metabolite by different bacterial species has not been described yet. This highlights a new aspect of interpreting multispecies interactions in microbial communities as not only direct interactions between species might determine and influence the dynamics of the community. Events outside the cell could lead to the appearance of new compounds which could possess new community shaping properties.

Introduction

Bacterial communities represent very diverse and dynamic systems. This applies especially to densely populated soil, marine and plant- or human-associated habitats where bacterial cells experience a highly competitive environment regarding living space, water and nutrients1–4. Survival, growth and flourishing depend on their abilities for quick acclimations to changing living conditions and their strategies to outcompete co-habitants. Consequently, bacteria developed a tight network of interactive patterns consisting of cooperative traits, but also competitive and antagonistic action modes5. Antagonism is often realized by the release of secondary metabolites6. Research of recent years has shown that many of these secondary metabolites are volatile compounds7–9. Because of their properties (small molecules with a high vapor pressure), volatiles do not only easily diffuse into areas close to the emitting organism, but also travel over longer distances. Therefore, they represent antagonistic and/or signalling compounds with a potential to manipulate physiological processes in other bacteria, as well as in fungi and plants10–14. The recognition of volatiles enables bacteria to adjust to developmental processes that take place in microbial communities15, thereby influencing the motility, biofilm formation and sporulation16–19. Furthermore, antibiotic resistances and other stress responses can be enhanced due to contact with bacterial volatiles18–21. On the other side, volatile metabolites can exhibit direct bacteriostatic and bactericidal activities22,23.

Volatile compounds with such a potential are schleiferons (3-(phenylamino)butan-2-one and 3-(phenylimino)butan-2-one, schleiferon A and B, respectively). They are produced by Staphylococcus schleiferi isolates24. If present in the environment, schleiferons dramatically decrease the growth of Gram-positive bacteria and affect quorum-sensing controlled phenotypes of Gram-negative bacteria24. Schleiferon A is formed by a spontaneous reaction between acetoin and 2-phenylethylamine (Schulz et al. unpublished), which are both synthesized by the bacterium S. schleiferi. Schleiferon B represents the oxidation product of A (Schulz et al. unpublished).

Both acetoin and 2-phenylethylamine are volatile compounds themselves. They are produced by a broad range of bacterial species25,26. A bacterial community in general can consist of several different bacterial species. These species a priori have the potential to synthesize precursors of final volatile products. This fueled the hypothesis that precursors like acetoin or 2-phenylethylamine released by different species into the headspace of a microbial community will spontaneously react to non-enzymatically form an active principle like schleiferon A (and B). The goal of our experiments was to introduce a mechanism of how new compounds could arise within a habitat colonized by microbes. This mechanism could contribute besides direct microbial interactions to a variable composition of the headspace and adds a new aspect to the in generally known dynamics of microbial communities.

Results

The in vitro headspace reaction

A preliminary investigation was necessary in order to evaluate whether acetoin and 2-phenylethylamine react in an aerial environment. We separately dropped both compounds in two Petri dishes. These Petri dishes were simultaneously incubated in an analysis chamber for 24 hours. Subsequently, we funneled an air stream through the chamber onto an adsorbent and analyzed the eluted compounds by GC/MS (Fig. S1a). As shown in Fig. S1b, schleiferon A was also formed from acetoin and 2-phenylethylamine when incubated under aerial conditions. Since it lingered in the headspace of the Petri dish, most of it was oxidized to schleiferon B. Consequently, we could search for an acetoin producing bacterial strain that would not be able to emit 2-phenylethylamine and vice versa a bacterial isolate that emits solely 2-phenylethylamine.

Qualified bacterial aspirants

The genus Serratia is known to produce acetoin during fermentation of sugars27. We analyzed the volatile compounds released by S. plymuthica 4Rx13 growing in complex liquid medium supplemented with glucose in a closed dynamic airflow system24,28. Already after 24 hours of growth, acetoin (#1) was detected (Fig. S2a). The emission quickly increased during the exponential growth phase and peaked after 48 h of incubation, which corresponded with the early stationary phase of bacterial growth (Fig. S2c). Subsequently, the acetoin level declined and reached the lowest value after 120 hours of growth. Most importantly, 2-phenylethylamine (#2) was not detected at all during these sampling periods.

While screening for a 2-phenylethylamine producer, S. delphini 20771 captured our attention. This strain emitted only 2-phenylethylamine during cultivation in tryptic soy broth (TSB) (#2, Fig. S2b). The emission started after 96 h and even increased after 120 hours of growth (Fig S2d). S. delphini 20771 did not release acetoin (#1) during these sampling intervals.

Interspecific bacterial formation of schleiferons

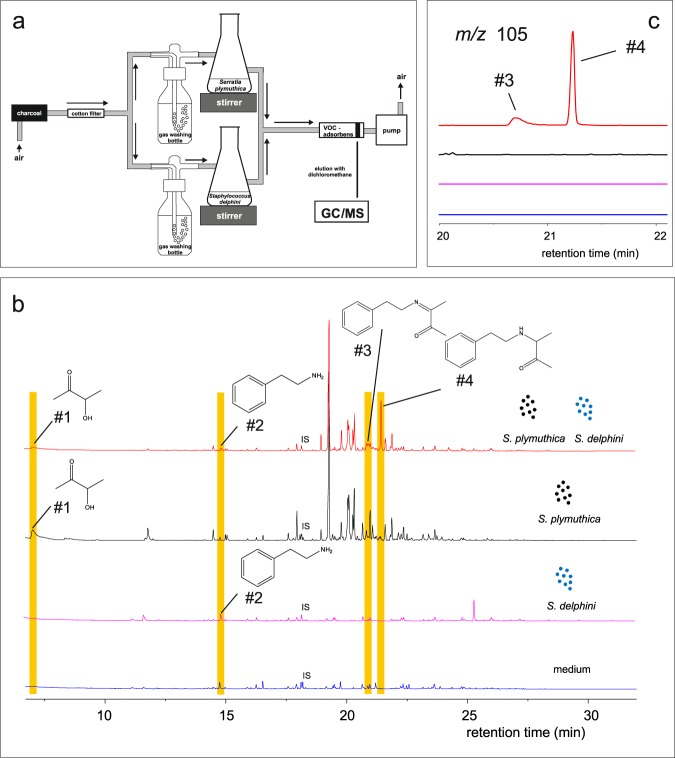

Based on the results of the mono-cultivation described above, we developed a VOC collection system where both bacterial isolates were concurrently cultivated in separated vessels. A split air stream entered simultaneously one culture flask inoculated with a 24 h old culture of S. plymuthica 4Rx13 (flask 1) and one flask with a 120 h old culture of S. delphini 20771 (flask 2). The two VOC-enriched air streams were reunited to allow the chemical reaction of acetoin produced by S. plymuthica 4Rx13 and 2-phenylethylamine produced by S. delphini 20771 (Fig. 1a). We used three controls. In control 1, both flasks were filled with NBII liquid medium supplemented with glucose and TSB, respectively. Sets with one culture flask inoculated with S. plymuthica 4Rx13 while the other flask contained TSB and one flask inoculated with S. delphini 20771 while the other flask contained NBII plus glucose served as control 2 and 3, respectively. The experiments were performed in triplicate. As expected, the precursor molecule acetoin (#1) was emitted by S. plymuthica 4Rx13 (control 2). The precursor 2-phenylethylamine (#2) was present in the VOC profile of S. delphini 20771 (control 3). Both controls did not contain schleiferons. Control 1 did not contain precursors nor schleiferons. Small amounts of the precursors were still present in the concurrent culture of both bacterial isolates, however, most interesting was the detection of schleiferon A (#4) and B (#3) in the reunified bacterial headspace of this S. plymuthica/S. delphini concurrent culture after 24 h and 48 h of cultivation (Fig. 1b). Since S. plymuthica 4Rx13 released other compounds co-eluting with schleiferon B (#3), we verified the TIC result by an EIC m/z 105 representing the base peak of schleiferon A (#4) and B (#3) (Fig. 1c). The mass feature of m/z 105 at the retention time of schleiferon B was unique for the S. plymuthica/S. delphini concurrent culture.

Figure 1.

Schleiferon formation in concurrent cultures of physically separated Serratia plymuthica and Staphylococcus delphini. (a) VOC-collection system: Charcoal purified and sterilized air was split into two air streams of which each entered one culture flask containing either S. plymuthica 4Rx13 or S. delphini 20771. After VOC-enrichment, the two air streams were reunited and funneled over a VOC adsorbent (Porapak) (b) TIC-GC/MS chromatograms of media (blue line), S. delphini mono-culture (pink line), S. plymuthica mono-culture (black line) and S. plymuthica/S. delphini concurrent cultured for 24 hours (red line) (c) EIC-GC/MS chromatograms of m/z 105 representing the base peak of schleiferon A and B (color code for experimental set up see (b). #1: acetoin, #2: 2-phenylethylamine, #3: schleiferon B, #4: schleiferon A; IS = internal standard (N-nonyl acetate, 5 ng); n = 3.

Discussion

Our experiments strongly indicate that in a microbial community volatile products can arise from microbial precursor molecules which originate from cells of different species. We used the bacterial isolates S. plymuthica 4Rx13 and S. delphini DSMZ 20771 as model organisms in order to illustrate the principle. Although these particular isolates did not originate from the same habitat, it can be assumed that acetoin producing bacterial species and 2-phenylethylamine producers can inhabit the same ecological niches. The 2-phenylethylamine producer Enterococcus faecalis29 and the acetoin producer Serratia sp.30 both found to be ubiquitous constituents of the gastrointestinal microbiome, represent only one example31,32. It should be noted that our in vitro experiment required certain nutrient conditions for each strain, in order to provoke the synthesis of the precursor molecules. This situation might ostensibly not be expected when bacteria share the same ecological niche in a natural environment. However, particularly in densely populated microhabitats like soil pores of the rhizosphere or the zone along root hairs, nutrient conditions can be different. Plants secrete metabolites depending on species, age, developmental stage and root zone33. Adjacent living cells of different bacterial species might therefore experience different nutrient conditions and accordingly produce a certain spectrum of volatile metabolites, which could undergo a chemical reaction as we could show for acetoin and 2-phenylethylamine. Furthermore, in a populated hotspot where cells of different species mingle even under comparable nutrient supplies, cells of certain species could cause a modification of the ambient milieu in terms of secreting metabolites that serve as nutrient for other species or change conditions (i.e. pH-value) in the microhabitat34–36. Those changing conditions can also provoke a changing spectrum of volatile metabolites of certain species. New volatile metabolites emitted into the headspace again could have the potential to initialize chemical reactions. Similar scenarios can be assumed for intestines of animals. A changing pH-value in gut systems and a different status of nutrient digestion might challenge symbiotic gut bacteria in a similar way37,38. As those specific alterations in conditions in the microbial habitat might facilitate beneficial chemical reactions, natural environmental conditions, such as water and oxygen saturation, temperature, salinity, chemical composition of the habitat and the pH-value could in general affect headspace reactions. This influence should be questioned in further investigations.

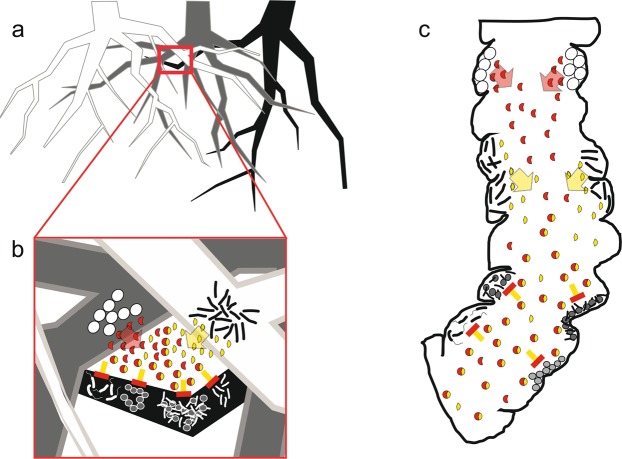

In conclusion, our results show a new aspect of volatile production in microbial communities. We suggest that not only a single organism i.e. a bacterial cell of a certain species, participates in the synthesis of a final volatile metabolite which is released into the environment. Volatile metabolites could also be formed in the headspace of a microbial community by a non-enzymatic reaction employing precursors that could originate from cells of different species. Consequently, the microbial community itself has to be considered for VOC production. The synthesis of volatile precursors and perhaps even the non-enzymatic reaction might be a result of interaction between species. It is already known that microbial interactions can strongly influence the spectrum of volatiles metabolites emitted by a microbial community39–43. However, even if the reaction would be a random result of emitted precursors of accidentally coexisting organisms it could be of the benefit of one or even both producer species. In addition, interspecifically formed volatile secondary metabolites could impair third party organisms i.e. cells of other bacterial or fungal species. Therefore, they could contribute to survival, growth and flourishing of precursor producers in a community (Fig. 2). Producers of matching precursors might seek neighbourly contact for the benefit of both. Since fungi can also form 2-phenylethylamine44, inter-kingdom communicative traits can be expected. Hence, the headspace of habitats should not be considered as a static environment but rather as a dynamic system. Although, these conclusions have to be confirmed, they represent an important and non-negligible aspect to describe, evaluate and analyze interactions in a multispecies community and there is plenty of room for further research.

Figure 2.

Scenarios of tritrophic interactions between bacterial species mediated by volatile compounds formed by an interspecific reaction. Physically separated bacterial species A and B produce the volatile precursors 1 ( ) and 2 (

) and 2 ( ), respectively. Released into the environment both volatiles react in the airspace of respective habitats as soil pores (b) of the rhizosphere (a) or the intestine (c) forming the active principle (

), respectively. Released into the environment both volatiles react in the airspace of respective habitats as soil pores (b) of the rhizosphere (a) or the intestine (c) forming the active principle ( ). This compound may impair further microbial organisms e.g. by growth inhibition or manipulation of the quorum sensing-system of bacteria (

). This compound may impair further microbial organisms e.g. by growth inhibition or manipulation of the quorum sensing-system of bacteria ( ). Varying nutrient supply due to different root exudates of certain plant species (a and b; roots in white, gray, black) and changing growth conditions as pH-value changes and varying microbial colonization in intestines ensure that a variety of precursors meet and match and furthermore travel to reach a third party which might be harmed. (root drawing: idea from Vecteezy.com47).

). Varying nutrient supply due to different root exudates of certain plant species (a and b; roots in white, gray, black) and changing growth conditions as pH-value changes and varying microbial colonization in intestines ensure that a variety of precursors meet and match and furthermore travel to reach a third party which might be harmed. (root drawing: idea from Vecteezy.com47).

Methods

Bacterial strains and maintenance

The rhizobacterium Serratia plymuthica 4Rx13 was isolated from Brassica napus45. Staphylococcus delphini DSMZ 20771 originated from purulent material from a dolphin46. Short-term maintenance of S. plymuthica 4Rx13 was performed on nutrient agar plates supplemented with glucose (NAIIG; peptone from casein 3.5 g l−1, peptone from meat 2.5 g l−1, peptone from gelatine 2.5 g l−1, yeast extract 1.5 g l−1, NaCl 5 g l−1, glucose 100 mM, agar-agar 15 g l−1). S. delphini was cultivated on tryptic soy agar plates (TSA; tryptone 17 g l−1, soy meal 3 g l−1, K2HPO4 2.5 g l−1, glucose 2.5 g l−1, NaCl 5 g l−1, agar-agar 15 g l−1). Cultures were incubated for 12–24 hours at 30 °C under dim light (1.5 µEm−2s−1) and finally stored at 4 °C. For conservation, overnight liquid cultures were supplemented with glycerol (25%) and subsequently stored at − 70 °C.

Reaction of acetoin and 2-phenylethylamine in an aerial environment

Acetoin (200 µg dissolved in 1 ml dichloromethane) and 2-phenylethylamine (400 µg dissolved in 1 ml dichloromethane) were separately dropped in a glass Petri dish (Ø30 × 10 mm). These Petri dishes were placed without a lid in another glass Petri dish (Ø130 × 30 mm), which had an in- and outlet (analysis chamber). After 24 h of incubation (30 °C and 1.5 µEm−2s−1), charcoal-purified, sterile air was sucked through the inlet into the analysis chamber with a constant flow of 0.6 l min−1 provided by a membrane pump (1410 Büh 12 VDC “D”, Gardner Denver Thomas GmbH, Memmingen, Germany). The volatile-enriched air was directed to a trap containing 30 mg of an adsorbent matrix (Porapak; Sigma–Aldrich, Munich, Germany). After 24 h of incubation, the volatiles were consecutively eluted with 200 and 100 µl dichloromethane. N-nonyl acetate solution was added as an internal standard (final concentration of 5 ng µl−1).

VOC collection of mono-cultivated bacterial strains

A single bacterial colony of S. plymuthica 4Rx13 and S. delphini DSMZ 20771 was inoculated into 6 ml nutrient broth II supplemented with glucose (NBIIG) and tryptic soy broth (TSB), respectively. Cultures were incubated overnight under agitation (160 rpm; Bühler, Tübingen, Germany) at 30 °C until reaching an OD600 of 1–2. They were diluted into 100 ml medium (NBIIG or TSB) to obtain an initial OD600 of 0.005 and further incubated for 120 h using specific Erlenmeyer flasks supplied with an in- and outlet nozzle (30 °C, 1.5 µEm−2s−1, agitation using a magnetic stirrer). Pure medium served as control. VOC collection was performed as described in Kai et al. 2010 and Lemfack et al. 201624,28. Charcoal-purified, sterile and humidified air was sucked through the inlet into the flask with a constant flow of 0.6 l min−1 provided by a membrane pump (1410 Büh 12 VDC “D”, Gardner Denver Thomas GmbH, Memmingen, Germany). The volatile-enriched air was directed into a trap containing 30 mg of an adsorbent matrix (Porapak; Sigma–Aldrich, Munich, Germany). After defined incubation intervals (24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 h), the volatiles were consecutively eluted with 200 and 100 µl dichloromethane. N-nonyl acetate was added as an internal standard (final concentration of 5 ng µl−1). Simultaneously, the living cell number was determined at every 24 h by serial dilution in NaCl-solution (0.8%). The dilutions were plated and CFUs were counted. The experiments were conducted in triplicate.

VOC collection of physically separated concurrently cultivated bacterial strains

The pre-cultivation of the bacterial strains and inoculation into the Erlenmeyer flasks was performed as described above. The VOC-collection system was modified as followed. Charcoal-purified and sterile air was sucked with a constant flow of 0.6 l min−1 (1410 Büh 12 VDC “D”, Gardner Denver Thomas GmbH, Memmingen, Germany). After passing the cotton filter, the air stream was split, humidified and directed through two Erlenmeyer flasks (Fig. 1a). While one Erlenmeyer flask was filled with a liquid culture of S. plymuthica 4Rx13 (24 h post inoculation), the second flask contained a S. delphini 20771 culture (120 h post inoculation). Three additional setups served as control. Flask 1 and 2 contained NBII + glucose and TSB, respectively (control 1). Furthermore, a mono-culture of S. plymuthica 4Rx13 in flask 1 was combined with TSB in flask 2 (control 2) and the mono-culture of S. delphini 20771 in flask 2 was combined with NBII + glucose in flask 1 (control 3). Cultures were magnetically stirred. Volatile-enriched air streams were reunited and sucked into a trap containing 30 mg of an adsorbent matrix (Porapak; Sigma–Aldrich, Munich, Germany). VOCs were consecutively eluted after 24 h and 48 h of cultivation with 200 and 100 µl dichloromethane. N-nonyl acetate was added as an internal standard (final concentration of 5 ng µl−1). The experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Gas-chromatographic separation and mass spectrometric detection of acetoin, 2-phenylethylamine and schleiferons

Samples were analyzed using a Shimadzu GC/MS-QP5000 system (Kyoto, Japan). Separation was performed on a DB5-MS column (60 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm; J&W Scientific, Folsom, California, USA) connected to a CTC autosampler (CTC Analytics, Zwingen, Switzerland). The sample (1 µl) was splitless injected at 200 °C with a solvent cut of 2 minutes. The initial temperature of the GC column was set at 35 °C. Compounds were separated using a continuous ramp of 10 °C min−1 up to 280 °C with a final hold of 5 minutes. Helium was used as carrier gas (flow rate of 1.1 ml min−1, linear velocity of 28 cm/s).

Electron ionization mass spectra (EIMS) were recorded at an ionization energy of 70 eV with a mass range of m/z 40–280. Schleiferon A and B were identified by comparison of mass spectra and retention times with those of synthesized standards.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dörte Warber for excellent technical assistance. Furthermore, we thank Prof. Stefan Schulz and Srinivasa Rao Ravella from University of Braunschweig for the synthesis of schleiferons used as reference compounds. Financial support was provided by the DFG to BP (Pi 153/28-1) and the University of Rostock.

Author Contributions

M.K. conceived and designed the project, performed the experiments and analyzed the data. M.K. produced figures and drawings. M.C.L. performed experiments that inspired ideas leading to this project. B.P. provided financial support. M.K. and U.E. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

2/26/2019

A correction to this article has been published and is linked from the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has been fixed in the paper.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-35341-3.

References

- 1.Gray JP, Herwig RP. Phylogenetic analysis of the bacterial communities in marine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996;62:4049–4059. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.4049-4059.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ding T, Schloss PD. Dynamics and association of microbial community types across the human body. Nature. 2014;509:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nature13178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bai Y, et al. Functional overlap of the Arabidopsis leaf and root microbiota. Nature. 2015;528:364–369. doi: 10.1038/nature16192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bulgarelli D, et al. Structure and function of the bacterial root microbiota in wild and domesticated barley. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:392–403. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hibbing ME, Fuqua C, Parsek MR, Petersen SB. Bacterial competition: surviving and thriving in the microbial jungle. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;8:15–25. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haas D, Defago G. Biological control of soil-borne pathogens by fluorescent pseudomonads. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006;3:307–319. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulz S, Dickschat JS. Bacterial volatiles: the smell of small organisms. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007;24:814–842. doi: 10.1039/b507392h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kai M, et al. Bacterial volatiles and their action potential. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009;81:1001–1012. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1760-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bos LDJ, Sterk PJ, Schultz MJ. Volatile metabolites of pathogens: A Systematic Review. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003311. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryu CM, et al. Bacterial volatiles promote growth in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003;100:4927–4932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730845100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Effmert U, Kalderás J, Warnke R, Piechulla B. Volatile mediated interactions between bacteria and fungi in the soil. J. Chem. Ecol. 2012;38:665–703. doi: 10.1007/s10886-012-0135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garbeva P, Hordijk C, Gerards S, de Boer W. Volatile-mediated interactions between phylogenetically different soil bacteria. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:289. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kai M, Effmert U, Piechulla B. Bacterial-plant-interactions: approaches to unravel the biological function of bacterial volatiles in the rhizosphere. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:108b. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piechulla B, Lemfack MC, Kai M. Effects of discrete bioactive microbial volatiles on plants and fungi. Plant Cell Environ. 2017;40:2042–2067. doi: 10.1111/pce.13011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Audrain B, Farag M, Ryu C-M, Ghigo J-M. Role of bacterial volatile compounds in bacterial biology. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2015;39:222–233. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuu013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schöller CE, Gurtler H, Pedersen R, Molin S, Wilkins K. Volatiles metabolites from Actinomycetes. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2002;50:2615–2621. doi: 10.1021/jf0116754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nijland R, Burgess JG. Bacterial olfaction. Biotechnol. J. 2010;5:974–977. doi: 10.1002/biot.201000174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim KS, Lee S, Ryu CM. Interspecific bacterial sensing through airborne signals modulates locomotion and drug resistance. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1809. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Letoffe S, Audrain B, Bernier SP, Delepierre M, Ghigo J-M. Aerial exposure to the bacterial volatile compound trimethylamine modifies antibiotic resistance of physically separated bacteria by raising culture medium pH. mBio. 2014;5:e00944–13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00944-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernier SP, Letoffe S, Delepierre M, Ghigo J-M. Biogenic ammonia modifies antibiotic resistance at a distance in physically separated bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 2011;81:705–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heal RD, Parsons AT. Novel intercellular communication system in Escherichia coli that confers antibiotic resistance between physically separated populations. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2002;92:1116–1122. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gurtler H, et al. Albaflavenone, a sespuiterpene ketone with a zizaene skeleton produced by a streptomycete with a new rope morphology. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1994;47:434–439. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.47.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dandurishvili N, et al. Broad-range antagonistic rhizobacteria Pseudomonas fluorescens and Serratia plymuthica suppress Agrobacterium crown gall tumours on tomato plants. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011;110:341–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lemfack MC, et al. Novel volatiles of skin-borne bacteria inhibit the growth of Gram-positive bacteria and affect quorum-sensing controlled phenotypes of Gram-negative bacteria. Syst. and Appl. Microbiol. 2016;39:503–515. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiao Z, Xu P. Acetoin metabolism in bacteria. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2007;33:127–140. doi: 10.1080/10408410701364604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irsfeld M, Spadafore M, Prüß BM. β-phenylethylamine, a small molecule with a large impact. Webmedcentral. 2013;4:4409. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moons P, van Houdt R, Vivijs B, Michiels CM, Aertsen A. Integrated regulation of acetoin fermentation by quorum sensing and pH in Serratia plymuthica RVH1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;77:3422–3427. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02763-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kai M, et al. Serratia odorifera: analysis of volatile emission and biological impact of volatile compounds on Arabidopsis thaliana. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;88:965–976. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2810-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beutling DM, Walter D. 2-Phenylethylamine formation by enterococci in vitro. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2002;215:240–242. doi: 10.1007/s00217-002-0525-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao Z, Lu JR. Strategies for enhancing fermentative production of acetoin: A review. Biotech. Advances. 2014;32:492–503. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lebreton F., Willems R. J. L. & Gilmore M. S. Enterococcus diversity, origins in nature, and gut colonization. In: Gilmore MS, Clewell DB, Ike Y, Shankar N (eds). Enterococci: From commensals to leading causes of drug resistant infection [Internet]. Mass Eye Ear Infirmary: Boston, available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK190427/ (2014). [PubMed]

- 32.Daniel DS, et al. Isolation and identification of gastrointestinal microbiota from the short-nosed fruit bat Cynopterus brachyotis brachyotis. Microbiol. Res. 2013;168:485–496. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bulgarelli D, Schlaeppi K, Spaepen S, van Themaat E. VL, Schulze-Lefert P. Structure and functions of the bacterial microbiota of plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013;64:807–838. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phelan VV, Liu W-T, Pogliano K, Dorrestein PC. Microbial metabolic exchange—the chemotype-to-phenotype link. Nature Chem. Biol. 2011;8:26–35. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones SE, et al. Streptomyces exploration is triggered by fungal interactions and volatile signals. eLife. Science. 2017;6:e21738. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herschend, J. et al. In vitro community synergy between bacterial soil isolates can be facilitated by pH stabilization of the environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 10.1128/AEM.01450-18 Accepted Manuscript (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Fallingborg J. Intraluminal pH of the human gastrointestinal tract. Dan. Med. Bull. 1999;46:183–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma N, et al. Nutrients Mediate Intestinal Bacteria–Mucosal Immune Crosstalk. Front Immunol. 2018;9:5. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schulz-Bohm K, Zweers H, de Boer W, Garbeva P. A fragrant neighborhood: volatile mediated bacterial interactions in soil. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:1212. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hol WH, et al. Non-random species loss in bacterial communities reduces antifungal volatile production. Ecology. 2015;96:2042–2048. doi: 10.1890/14-2359.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tyc, O., Zweers, H., de Boer, W. & Garbeva, P. Volatiles in inter-specific bacterial interactions. Front. Microbiol. 6, 1412 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Schmidt R, et al. Fungal volatile compounds induce production of the secondary metabolite Sodorifen in Serratia plymuthica PRI-2C. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:862. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00893-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kai M, Piechulla B. Interspecies interaction of Serratia plymuthica 4Rx13 and Bacillus subtilis B2g alters the emission of sodorifen. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2018;365:fny253. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fny253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stüttgen G, Sya R, Dittmar W. Determination of biogenous amines in fungus-cultures (Candida albicans, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Trichophyton rubrum and Microsporum canis) by thin-layer chromatography and mass-spectrometry. Mycoses. 1978;21:331–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1978.tb01578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berg G, et al. Plant-dependent genotypic and phenotypic diversity of antagonistic rhizobacteria isolated from different Verticillium host plants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;68:3328–3338. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.7.3328-3338.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Varaldo PE, Kilpper-Bälz R, Biavasco F, Satta G, Schleifer KH. Staphylococcus delphini sp. nov., a Coagulase-Positive Species Isolated from Dolphins. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1988;38:436–439. doi: 10.1099/00207713-38-4-436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.https://www.vecteezy.com/vector-art/146836-silhouette-tree-with-roots-vector.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.