Our results support the hypothesis that cytoplasmic proteins abundant in fungal fruiting bodies are involved in fungal resistance against predation. The toxicity of these proteins toward stylet-feeding nematodes, which are also capable of feeding on plants, and the abundance of these proteins in edible mushrooms, may open possible avenues for biological crop protection against parasitic nematodes, e.g., by expression of these proteins in crops.

KEYWORDS: mycophagy, lectin, avidin, filamentous fungus, Ashbya gossypii, nematotoxicity

ABSTRACT

Resistance of fungi to predation is thought to be mediated by toxic metabolites and proteins. Many of these fungal defense effectors are highly abundant in the fruiting body and not produced in the vegetative mycelium. The defense function of fruiting body-specific proteins, however, including cytoplasmically localized lectins and antinutritional proteins such as biotin-binding proteins, is mainly based on toxicity assays using bacteria as a heterologous expression system, with bacterivorous/omnivorous model organisms as predators. Here, we present an ecologically more relevant experimental setup to assess the toxicity of potential fungal defense proteins towards the fungivorous, stylet-feeding nematodes Aphelenchus avenae and Bursaphelenchus okinawaensis. As a heterologous expression host, we exploited the filamentous fungus Ashbya gossypii. Using this new system, we assessed the toxicity of six previously characterized, cytoplasmically localized, potential defense proteins from fruiting bodies of different fungal phyla against the two fungivorous nematodes. We found that all of the tested proteins were toxic against both nematodes, albeit to various degrees. The toxicity of these proteins against both fungivorous and bacterivorous nematodes suggests that their targets have been conserved between the different feeding groups of nematodes and that bacterivorous nematodes are valid model organisms to assess the nematotoxicity of potential fungal defense proteins.

IMPORTANCE Our results support the hypothesis that cytoplasmic proteins abundant in fungal fruiting bodies are involved in fungal resistance against predation. The toxicity of these proteins toward stylet-feeding nematodes, which are also capable of feeding on plants, and the abundance of these proteins in edible mushrooms, may open possible avenues for biological crop protection against parasitic nematodes, e.g., by expression of these proteins in crops.

INTRODUCTION

The fungal fruiting body is a relatively short-lived structure that, as a nutrient source, attracts many different predators due to its high and readily available nutrient content (1–6). Its importance to the organism as a sexual reproductive organ is reflected by the plethora of toxic molecules that are constitutively and specifically produced in this tissue at relatively high levels. These molecules have been discussed to reduce the negative impact of predators on the reproductive potential of the organism (7–9) by deterrence (10–15). While the role of many secondary metabolites in defense has been established over the years, the contribution of fruiting body-specific proteins such as lectins or biotin-binding proteins to defense remains still elusive. Similarly to that of secondary metabolites (16, 17), the biosynthesis of these proteins is subject to spatiotemporal regulation during fungal fruiting body development (18, 19).

Lectins are defined as proteins possessing at least one noncatalytic domain that binds reversibly to a specific monosaccharide or oligosaccharide (20). They act as recognition and effector molecules in the innate immune response of several phyla, including invertebrates, mammals, and plants (21, 22). In fungi, lectins are abundant in fruiting bodies and sclerotia (19, 23–25). Their cytoplasmic expression and the absence of cytoplasmic ligands, as well as the lack of developmental phenotypes upon downregulation, argue against an endogenous function, e.g., in fungal development (23, 26, 27). Recently, we tested the toxicity of different bacterially produced fungal fruiting body lectins for their toxicity against invertebrate and protozoan model organisms, including Caenorhabditis elegans, an Acanthamoeba sp., and Aedes aegypti (28). Their toxicity toward these bactivorous and omnivorous organisms suggests that fruiting body lectins may mediate a constitutive protein-based resistance of the fruiting body against predators (28).

Biotin-binding proteins are another class of putative defense molecules expressed in fruiting bodies. The synthesis of biotin is restricted to plants and some microorganisms, making biotin an essential vitamin for most other organisms, including herbivores and fungivores. Biotin-binding proteins are expressed by many different species. They are characterized by a very strong noncovalent binding to biotin and have been implicated as antimicrobial host defense factors that create a “biotin-free zone” (29–32). The cytoplasmic biotin-binding proteins of the basidiomycete Pleurotus cornucopiae, tamavidin 1 (Tam1) and 2 (Tam2), were shown to be toxic to C. elegans, an Acanthamoeba sp., and Drosophila melanogaster (33).

The contribution of individual proteins to fungal resistance toward ecologically relevant fungivores has hardly been investigated in the past. To date, most studies determined the toxicity of individual heterologously expressed proteins to model organisms (18, 28, 33–35). In contrast, for this study, we assessed the potentials of different protein classes as resistance molecules against two fungivorous nematode species. Nematodes are one of the most abundant organisms in the soil ecosystem, and many of them include fungi in their diets or feed exclusively on fungi (36). Thus, nematodes represent an ecologically relevant phylum of fungal predators. Due to their feeding mechanism, i.e., piercing the hyphal cell wall with a stylet, fungivorous nematodes can bypass many deterring secondary metabolites deposited in the cell wall (37–39). The cytoplasmic expression of nematotoxic proteins in fungi could therefore be a prime mechanism to defend against this type of predation. The fungivorous nematodes Aphelenchus avenae Bastian (40) and Bursaphelenchus okinawaensis strain SH1 (41) were used as model predators due to their ubiquitous presence in soils of temperate regions, where they cohabit in this ecosystem with most of the fungal species chosen for this study. These nematodes feed on the mycelium and fruiting body tissue, making them ideal candidate organisms to evaluate the toxicity of cytoplasmically expressed fruiting body defense proteins (FBDPs) (42, 43). Six different FBDPs belonging to the two FBDP classes introduced above were chosen for this study. We heterologously expressed these FBDPs individually in the cytoplasm of vegetative hyphae of the ascomycete Ashbya gossypii, thereby retaining the physiological context of the proteins.

The applied experimental system allowed a direct comparison of toxicity between the individual proteins. The observed susceptibility of a fungal predator to different FBDPs supports the hypothesis that these proteins are produced to confer fruiting body resistance to predation. Similar toxicities against fungivorous and bacterivorous nematodes were found, suggesting that the respective targets of the toxins are conserved between different species/classes of nematodes.

RESULTS

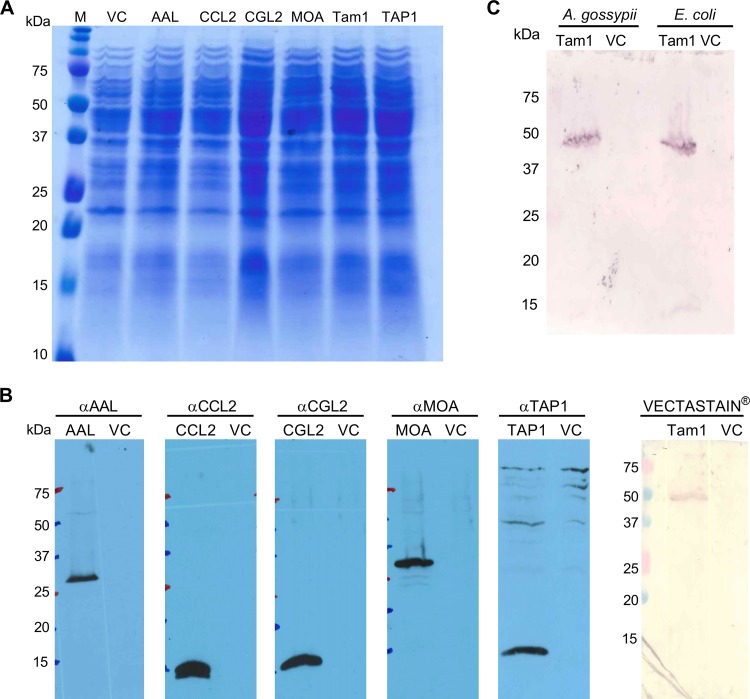

We selected a panel of six previously characterized FBDPs, covering a wide spectrum of fungal species, protein folds, and biochemical activities, to assess the biotoxicity of such proteins against the fungivorous nematodes A. avenae and B. okinawaensis (Table 1). The ascomycete A. gossypii was the expression host system of choice, because it can be easily modified genetically and expresses no orthologues of the FBDPs tested in this study. To obtain comparable results in a well-defined system and to maintain the physiological localization of the FBDPs during predation, we cloned and expressed each of the fungal FBDPs individually in the cytoplasm of A. gossypii and probed their expression (Fig. 1A). In immunoblot analyses, we could detect all proteins at their calculated molecular masses, except for Tam1, which was detected via its tetrameric, biotin-bound form (see Materials and Methods) (Fig. 1B). This detection method for Tam1 was validated by assaying the heterologous expression of the protein in Escherichia coli (Fig. 1C).

TABLE 1.

Overview of the fruiting body defense proteins (FBDPs) tested for toxicity against A. avenae and B. okinawaensisa

| Lectin/defense protein (FBDP)b | Molecular mass (kDa) | Origin | Protein family | Ligand specificity | Toxicity against: |

GenBank accession no. | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. aegypti | C. elegans | |||||||

| CGL2 | 16.7 | Coprinopsis cinerea | Galectin | Galβ(1,4)Glc, Galβ(1,4)GlcNAc, Galβ(1,4)Fuc | Toxic | Toxic | AAF34732 | 28, 48, 56 |

| CCL2 | 15.3 | Coprinopsis cinerea | Ricin B-type lectin | GlcNAcβ(1,4)[Fucα(1,3)]GlcNAc | Nontoxic | Toxic | EU659856 | 18, 57 |

| TAP1 | 16.1 | Sordaria macrospora | Actinoporin-like lectin | Galβ(1,3)GalNAc | Toxic | Toxic | CAH03681 | 23, 28 |

| MOA | 32.3 | Marasmius oreades | Chimeric ricin B-type lectin | Galα(1,3)Gal | Toxic | Toxic | AY066013 | 35, 58 |

| AAL | 33.4 | Aleuria aurantia | β-Propeller lectin | Fucose | Toxic | Toxic | BAA12871 | 28, 55, 59, 60 |

| Tam1 | 15.1 | Pleurotus cornucopiae | Biotin-binding protein | Biotin | Nontoxic | Toxic | AB102784 | 33, 46 |

Six different FBDPs from five fungal species were cloned and expressed in A. gossypii in order to test their toxicity toward fungal-feeding nematodes A. avenae and B. okinawaensis. The six selected FBDPs were previously shown to be toxic to at least one of the indicated bacterivorous or omnivorous model organisms.

CGL2, Coprinopsis cinerea galectin 2; CCL2, Coprinopsis cinerea lectin 2; AAL, Aleuria aurantia lectin; MOA, Marasmius oreades agglutinin; TAP1, Sordaria macrospora transcript associated with perithecial development 1; Tam1, tamavidin 1.

FIG 1.

Expression analysis of A. gossypii transformants expressing different FBDPs. (A) Fungal lysate (20 μl) was loaded on an SDS-PAGE gel and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. (B) Whole-cell protein extracts of A. gossypii transformants carrying the A. gossypii VC (VC) or one of the FBDP-encoding plasmids were analyzed by immunoblotting using FBDP-specific polyclonal antibodies. For detection of tamavidin 1, the Vectastain ABC alkaline phosphatase system was used. The expected molecular mass of each protein is given in Table 1. (C) Expression of tamavidin 1 in A. gossypii and E. coli was detected using the Vectastain ABC alkaline phosphatase system. The sizes of the marker proteins are indicated.

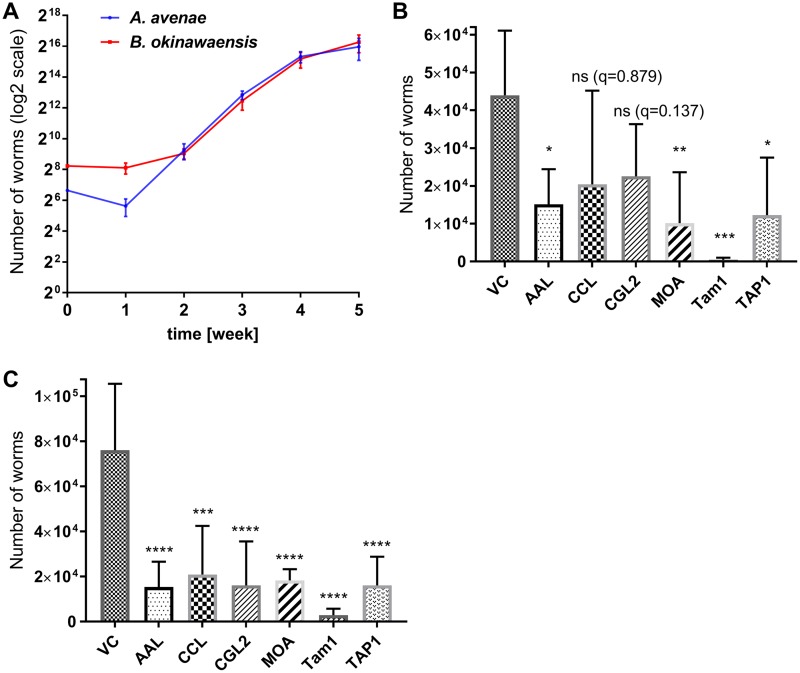

In the propagation rate assay, both nematodes grew at an exponential rate on A. gossypii colonies, proving that it is a suitable food source for the fungivorous nematodes used in this study (Fig. 2A). In the case of B. okinawaensis, three times more nematodes were added to compensate for the slow growth of this worm compared to that of A. avenae on A. gossypii plates (Fig. 2A).

FIG 2.

Propagation rate of fungivorous nematodes on different A. gossypii transformants. (A) A. avenae (100) or B. okinawaensis (300) nematodes were propagated on A. gossypii VC. Nematodes were harvested and counted after the indicated times of incubation. (B) Indicated FBDPs were individually expressed in the vegetative mycelium of A. gossypii. A. avenae (100) nematodes were inoculated on individual A. gossypii transformants and incubated for 28 days at 20°C. Thereafter, nematodes were harvested and counted. (C) Indicated FBDPs were individually expressed in the vegetative mycelium of A. gossypii. A total of 300 B. okinawaensis nematodes were inoculated on individual A. gossypii transformants and incubated for 28 days at 20°C. After this period, nematodes were harvested and counted. Each error bar represents the standard deviation of five biological replicates. Dunnett's multiple-comparison test was used for statistical analysis. ns, not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. Significance was determined versus VC.

The toxicity of the individual FBDPs to fungivorous nematodes was assessed by comparing propagation of the nematodes on A. gossypii transformants, constitutively expressing one of the defense proteins, relative to that of an A. gossypii vector control (VC) strain (Fig. 3). After 28 days of cocultivation, the cultures were harvested and the sizes of the nematode populations were assessed. This period corresponds, according to the determined propagation rates, to the exponential growth phase of the nematodes (Fig. 2A) We found that four out of six tested FBDPs expressed in A. gossypii (Aleuria aurantia lectin [AAL], Marasmius oreades agglutinin [MOA], Sordaria macrospora transcript associated with perithecial development 1 [TAP1], and Tam1) conferred a significant inhibition of propagation for both nematodes (Fig. 2B and C). The two fruiting body lectins from Coprinopsis cinerea, Coprinopsis cinerea galectin 2 (CGL2) and Coprinopsis cinerea lectin 2 (CCL2), exhibited significant toxicity for B. okinawaensis, whereas the effect on the propagation of A. avenae was not statistically significant and was highly variable (Fig. 2B and C). Determination of the propagation rate of A. avenae nematodes fed with A. gossypii transformants expressing these two lectins was repeated with more biological replicates; however, the high variability among biological replicates was reproducible.

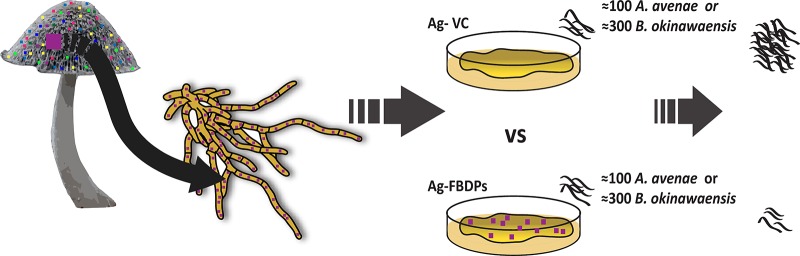

FIG 3.

Schematic representation of the experimental setup. FBDPs from different fungal species were selected and individually expressed in A. gossypii vegetative mycelium. The indicated numbers of each nematode were picked and placed onto an A. gossypii colony harboring a control plasmid or expressing an FBDP. After 4 weeks, the coculture was harvested and nematodes were counted.

Three of the toxic FBDPs were lectins (Fig. 2B): AAL, a fucose-binding lectin from Aleuria aurantia; MOA, a chimerolectin expressed in the fruiting bodies of Marasmius oreades; and TAP1, an actinoporin-like lectin from perithecia of Sordaria macrospora. These lectins significantly slowed both A. avenae and B. okinawaensis propagation when constitutively expressed in A. gossypii. In these three treatments, the nematode populations were approximately a quarter of the size of that in the control. The most dramatic effect on nematode development was observed for treatments expressing the biotin-binding protein tamavidin 1 (Fig. 2B and C). When this protein was expressed in A. gossypii, very few nematodes (less than 4% compared to the VC strain population) were retrieved from the cocultures, indicating that expression of biotin-binding proteins strongly prevented the propagation of the fungivorous nematodes.

The toxicity of the tested FBDPs is similar to what was observed for the bacterivorous model organism C. elegans (Table 1), suggesting that the underlying target(s) is conserved among different nematode species.

DISCUSSION

Fungal fruiting and resting (sclerotia) bodies express multiple defense toxins against predators (17, 44). The functional redundancy of these molecules with regard to toxicity makes it difficult to study the contribution of an individual compound or protein to fungal resistance towards a specific predator. Therefore, a synthetic approach is favored over the deletion of individual genes. We present here a heterologous fungal expression system that is similar to the physiological situation in the originating fungi and thus allows investigation of the role of an individual protein in fungal resistance towards fungivores.

The filamentous yeast A. gossypii appears to be an ideal tool for studying individual FBDPs and their contribution to the protein-mediated defense against a particular predatory species. The organism lacks orthologs of many FBDPs, possibly due to its phylogenetic relatedness to the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and its adaptation to insects as an ecological niche (45), but it is readily used as prey by the model fungivorous nematodes (Fig. 2A). Expression analysis showed that all proteins are expressed and can be detected in A. gossypii (Fig. 1B). Due to the use of different antisera for the different FBDPs, no real quantitative statements about the expression levels of the various FBDPs can be made, however. The detection signal for tamavidin 1 was very weak at the expected molecular mass (15.1 kDa) of the monomer and much stronger at 50 kDa (Fig. 1B and C). Previously, it was shown that tamavidin 1 is a homotetramer in its native form. The molecular mass of the homotetramer was estimated to be around 50 kDa, based on gel filtration chromatography (46), which agrees with our findings. We hypothesize that the denaturing conditions of the SDS-PAGE lead to dissociation of most of the Tam1 homotetramers into monomers, but since the native tetrameric form binds biotin with high affinity, it is better detected with an avidin-based detection reagent. Resistance of homotetrameric Tam1 to SDS-PAGE denaturing conditions was confirmed by expressing the protein in E. coli (Fig. 1C).

The biotin-binding protein tamavidin 1 was highly effective against both A. avenae and B. okinawaensis (Fig. 2B and C). Toxicity of this protein is thought to depend on the sequestration of free biotin, thus reducing the bioavailability for the predator of this essential nutrient (29, 33, 47). The sequestration of an essential vitamin by a proteolysis-resistant, high-affinity binding protein seems to be a powerful way to prevent predation. Our results confirm those of previous studies, in which biotin-binding proteins have been implicated in fungal resistance and employed as effective repellents in plants for several different predators and parasites (33, 47). The lack of toxicity of tamavidin 1 expression for the producing organisms E. coli (33) and A. gossypii (this study) suggests that there is no freely available biotin in the cytoplasm of these organisms.

Besides tamavidin 1, three of the tested lectins, AAL, MOA, and TAP1, were clearly toxic for both of the nematodes (Fig. 2B and C). In comparison to the biotin-binding protein, however, growth was not dramatically abolished, and the extent to which the lectins attenuated population growth varied. The C. cinerea fruiting body lectins CGL2 and CCL2 showed inconsistent effects on the A. avenae population size after 28 days, even though they were shown to be strongly toxic to the model nematode C. elegans (18, 28). The variable toxicity of these proteins toward A. avenae may be explained by the existence of specific mechanisms of this nematode to escape intoxication by these toxins, e.g., through changes of the glycans in the digestive tract. Thus far, there is no report about such a mechanism, but it has been shown in C. elegans that mutations in specific glycosyltransferases can confer resistance to both CGL2 and CCL2 (18, 48). The lower nematotoxicity of these proteins expressed in the A. gossypii (Fig. 1A) compared to E. coli (18, 28, 48) may be due to the lower expression levels of CGL2 and CCL2 in the fungus compared to those in the bacterium.

With this study, we present experimental evidence that FBDPs are involved in the defense of fungi against fungivores. Based on our experiments, we cannot make a statement, however, about how the observed toxicity would protect the fungus from predation. Based on previous experiments with FBDP-expressing E. coli and C. elegans, we hypothesize that the nematodes would avoid feeding on the toxic fungus (28). The heterologous expression system for FBDPs implemented here allows the comparison of many different candidate proteins and protein classes for their toxicity against the fungivorous nematodes A. avenae and B. okinawaensis and other fungivores. Since some of these proteins are abundant in edible mushrooms, and A. avenae also feeds on plant epidermal cells and root hairs (38), our results open possible avenues for crop protection, e.g., by expression of FBDPs from edible mushrooms in crops.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and cultivation conditions.

Escherichia coli strains DH5α and BL21 were used for cloning and protein purification, respectively. Both strains were cultivated on LB medium, as described previously (49). The nematodes A. avenae (Bastian, 1865) and B. okinawaensis (strain SH1) were maintained on a sporulation-deficient strain (BC-3) of Botrytis cinerea cultivated on malt extract agar medium (MEA) supplemented with an additional 15 g/liter agar and 100 μg/ml chloramphenicol at 20°C in the dark (41, 50). Nematodes were extracted from cocultures by Baermann funneling (51, 52) and decontaminated on 1.5% water-agar plates containing 200 μM G418 (Geneticin) and 50 μg/ml kanamycin for 2 days at 20°C (28). Toxicity assays were performed with A. gossypii ATCC 10895 and its transformants created in this study (Table 2) on solid Ashbya full medium (AFM) (1% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 1% [wt/vol] peptone, 1.5% [wt/vol] agar, 2% [wt/vol] glucose, 0.1% [wt/vol] myo-inositol, and 200 μM G418) at 20°C (53).

TABLE 2.

A. gossypii plasmids and strains generated and used for this study

| Plasmid | Markers | Insert | Source or reference | Resulting strain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pRS-AgTEFp-GFP | Ampr, GEN3 | GFPa | 61 | AgGFP |

| pRS-AgTEF-VC | Ampr, GEN3 | None | This study | AgVC |

| pRS-AgTEF-CGL-2 | Ampr, GEN3 | CGL2 | This study | AgCGL2 |

| pRS-AgTEF-CCL-2 | Ampr, GEN3 | CCL2 | This study | AgCCL2 |

| pRS-AgTEF-TAP-1 | Ampr, GEN3 | TAP1 | This study | AgTAP-1 |

| pRS-AgTEF-MOA | Ampr, GEN3 | MOA | This study | AgMOA |

| pRS-AgTEF-AAL | Ampr, GEN3 | AAL | This study | AgAAL |

| pRS-AgTEF-Tam1 | Ampr, GEN3 | Tam1 | This study | AgTam1 |

GFP, green fluorescent protein.

Cloning and expression of fungal lectins and other cytoplasmic defense proteins in A. gossypii.

We selected a total of six previously characterized fruiting body-specific lectins and a biotin-binding protein from five different fungal species (Table 1). The primers and plasmids used to amplify the respective cDNAs from pET expression vectors, as well as the plasmids generated in this study, are listed in Tables 3 and 2, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Primer sequences used for amplification of FBDP-coding sequences and their cloning into A. gossypii expression vector pRS-AgTEF

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Parental plasmid | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CGL2 fwd SalI | GGGGGGGTCGACATGCTCTACCACCTTTTCGTCAAC | pET24b-CGL2 | 62 |

| CGL2 rev AscI | GGGGGGGGCGCGCCCTAAGCAGGGGGAAGTGGG | ||

| CCL2 fwd SalI | GGGGGGGTCGACATGGACTCCCCAGCTGTGAC | pET24b-CCL2 | 18 |

| CCL2 rev AscI | GGGGGGGGCGCGCCCTAGACCTTCTCGATGACCC | ||

| TAP1 fwd XhoI | AAAAAACTCGAGGTCGACATGTCCTACACCCTCCACCTCCGT | pET24b-TAP1 | 28 |

| TAP1 rev AscI | AAAAAAGGCGCGCCTCAAAGATACTCAACCGTAGCCCT | ||

| MOA fwd SalI | GATGTCGTCGACCATATGTCTCTGCGACGCGGAATTTAC | pET22-MOA | 35 |

| MOA rev AscI | GTATTAGGCGCGCCCTCAGTAGAAGGCCATGTAGCTGTC | ||

| AAL fwd SalI | GGGGGGGTCGACATGCCTACCGAATTCCTCTAC | pET28b-AAL | 28 |

| AAL rev AscI | GGGGGCGCGCCTTACCATCCCGCGGGAGTG | ||

| Tam1 fwd SalI | TTTTTTGTCGACATGAAAGACGTCCAATCTCTCCTCACC | pET24b-Tam1 | 33 |

| Tam1 rev AscI | TTTTTTGGCGCGCCTCACTCGAACTTCAACCCGCGACG |

As a general cloning strategy, the green fluorescent protein (GFP)-encoding sequence in the A. gossypii expression plasmid pRS-AgTEFp-GFP was replaced by FBDP-encoding sequences using the restriction sites SalI/XhoI and AscI. The sequences of the resulting plasmids were verified by Sanger sequencing. Plasmids were transformed into A. gossypii by electroporation as described previously (54). Transformants were selected on AFM plates containing 200 μM G418. Homokaryons were produced by a second selection of spores isolated from transformants on AFM plates containing 200 μM G418.

Protein expression analysis in A. gossypii.

A. gossypii transformants were grown on AFM containing 200 μM G418 at 28°C for 7 days. Protein expression was verified by harvesting the mycelium and preparing whole-cell protein extracts of the A. gossypii transformant colonies, as described previously (28). The prepared extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting using specific antisera (1:2,500 dilutions) for detection of the various FBDPs, except for the extracts containing tamavidin 1, where the blotted extract proteins were probed for bound biotin using the Vectastain ABC alkaline phosphatase system (Vector Laboratories) in combination with a 1-Step NBT/BCIP (nitro-blue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3′-indolyl phosphate) solution (Thermo Scientific). Antisera against Coprinopsis cinerea galectin 2 (CGL2) and Coprinopsis cinerea lectin 2 (CCL2) were described previously (18, 28). The rabbit antisera against Marasmius oreades agglutinin (MOA), Aleuria aurantia lectin (AAL) and Sordaria macrospora transcript associated with perithecial development 1 (TAP1) were raised against the purified recombinant proteins by Pineda Antikörper-Service (Berlin, Germany). Expression and purification of these proteins from E. coli were carried out as previously described (28, 35, 55).

Determination of propagation rates of fungivorous nematodes on A. gossypii.

Propagation rates of A. avenae and B. okinawaensis nematodes on A. gossypii were determined by transferring 100 and 300 mixed-stage worms, respectively, onto a 7-day-old A. gossypii VC colony harboring pRS-AgTEF-VC (Table 2) on AFM plates containing 200 μM G418. During subsequent incubation of the cocultures for 35 days at 20°C, nematodes from five plates were harvested in parallel every week by Baermann funneling overnight at room temperature. The funneled volume was adjusted to 0.5 to 30 ml based on the estimated number of nematodes and counted six times by taking different aliquots each time. The total number of nematodes extracted from each plate was determined by multiplying the average of the six counts by the appropriate conversion factor (see Supplemental File 1). Thus, for each time point, five biological replicates were analyzed.

Toxicity assays of FBDPs toward fungivorous nematodes.

The toxicities of the individual toxins against fungivorous nematodes were assessed by cultivating A. gossypii transformants expressing the various FBDPs or carrying the expression vector control (VC) on AFM plates containing 200 μM G418 for 7 days at 28°C before inoculating the plates with 100 or 300 mixed-stage A. avenae or B. okinawaensis nematodes, respectively. The cocultivation plates were incubated at 20°C for 4 weeks. Subsequently, the plates were harvested by overnight Baermann funneling. The nematode population was assessed as described above. All assays were performed with five biological replicates. The individual counts and results of each biological replicate are listed in Supplemental File 1. Each data point in Fig. 2A, B, and C corresponds to the mean of five biological replicates.

Statistical analysis.

The statistical significance of the difference between the means of the nematode abundances for the various FBDPs and those of the respective controls was assessed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's multiple-comparison test. All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jürgen Wendland (Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium) and Peter Philippsen (Biozentrum Basel, Switzerland) for the plasmids, strains, and protocols for heterologous expression of proteins in A. gossypii. We are grateful to Therese Wohlschlager and Niels van der Velden for the purification of recombinant TAP1 and MOA used for antibody production. We thank Markus Aebi for his continuing interest, helpful discussions, and critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant 31003A_173097) and ETH Zürich.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02051-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hanski I. 1988. Fungivory: fungi, insects and ecology. Academic Press, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camazine S, Resch J, Eisner T, Meinwald J. 1983. Mushroom chemical defense. J Chem Ecol 9:1439–1447. doi: 10.1007/BF00990749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guevara R, Dirzo R. 1999. Consumption of macro-fungi by invertebrates in a Mexican tropical cloud forest: do fruit body characteristics matter? J Tropical Ecology 15:603–617. doi: 10.1017/S0266467499001042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Courtney SP, Kibota TT, Singleton TA. 1990. Ecology of mushroom-feeding Drosophilidae, p 225–274. In Begon M, Fitter AH, Macfadyen A (ed), Advances in ecological research, vol. 20 Academic Press, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Launchbaugh KL, Urness PJ. 1992. Mushroom consumption (mycophagy) by North American cervids. Western North Am Nat 52:321–327. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin MM. 1979. Biochemical implications of insect mycophagy. Biol Rev 54:1–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.1979.tb00865.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spiteller P. 2008. Chemical defence strategies of higher fungi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guevara R, Rayner ADM, Reynolds SE. 2000. Effects of fungivory by two specialist ciid beetles (Octotemnus glabriculus and Cis boleti) on the reproductive fitness of their host fungus, Coriolus versicolor. New Phytologist 145:137–144. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2000.00552.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sherratt TN, Wilkinson DM, Bain RS. 2005. Explaining Dioscorides' “double difference”: why are some mushrooms poisonous, and do they signal their unprofitability? Am Nat 166:767–775. doi: 10.1086/497399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stadler M, Sterner O. 1998. Production of bioactive secondary metabolites in the fruit bodies of macrofungi as a response to injury. Phytochemistry 49:1013–1019. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(97)00800-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demain A, Fang A. 2000. The natural functions of secondary metabolites, p 1–39. In Fiechter A. (ed), History of modern biotechnology I, vol 69 Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Germany. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rohlfs M, Churchill ACL. 2011. Fungal secondary metabolites as modulators of interactions with insects and other arthropods. Fungal Genet Biol 48:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheu S, Simmerling F. 2005. Growth and reproduction of fungal feeding Collembola as affected by fungal species, melanin and mixed diets. Oecologia 139:347–353. doi: 10.1007/s00442-004-1513-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rohlfs M, Albert M, Keller NP, Kempken F. 2007. Secondary chemicals protect mould from fungivory. Biology Lett 3:523–525. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood WF, Archer CL, Largent DL. 2001. 1-Octen-3-ol, a banana slug antifeedant from mushrooms. Biochem Syst Ecol 29:531–533. doi: 10.1016/S0305-1978(00)00076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doll K, Chatterjee S, Scheu S, Karlovsky P, Rohlfs M. 2013. Fungal metabolic plasticity and sexual development mediate induced resistance to arthropod fungivory. Proc Biol Sci 280:20131219. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amon J, Keisham K, Bokor E, Kelemen E, Vagvolgyi C, Hamari Z. 2018. Sterigmatocystin production is restricted to hyphae located in the proximity of hulle cells. J Basic Microbiol 58:590–596. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201800020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schubert M, Bleuler-Martinez S, Butschi A, Walti MA, Egloff P, Stutz K, Yan S, Collot M, Mallet JM, Wilson IB, Hengartner MO, Aebi M, Allain FH, Kunzler M. 2012. Plasticity of the beta-trefoil protein fold in the recognition and control of invertebrate predators and parasites by a fungal defence system. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002706. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boulianne RP, Liu Y, Aebi M, Lu BC, Kues U. 2000. Fruiting body development in Coprinus cinereus: regulated expression of two galectins secreted by a non-classical pathway. Microbiology 146:1841–1853. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-8-1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peumans WJ, Vandamme EJM. 1995. Lectins as plant defense proteins. Plant Physiol 109:347–352. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.2.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vasta G, Ahmed H, Tasumi S, Odom E, Saito K. 2007. Biological roles of lectins in innate immunity: molecular and structural basis for diversity in self/non-self recognition, p 389–406. In Lambris J. (ed), Current topics in innate immunity, vol 598 Springer, New York, NY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Hoff PL, Brill LM, Hirsch AM. 2009. Plant lectins: the ties that bind in root symbiosis and plant defense. Mol Genet Genomics 282:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s00438-009-0460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nowrousian M, Cebula P. 2005. The gene for a lectin-like protein is transcriptionally activated during sexual development, but is not essential for fruiting body formation in the filamentous fungus Sordaria macrospora. BMC Microbiol 5:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Candy L, Van Damme EJM, Peumans WJ, Menu-Bouaouiche L, Erard M, Rougé P. 2003. Structural and functional characterization of the GalNAc/Gal-specific lectin from the phytopathogenic ascomycete Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 308:396–402. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)01406-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burrows PR, Barker ADP, Newell CA, Hamilton WDO. 1998. Plant-derived enzyme inhibitors and lectins for resistance against plant-parasitic nematodes in transgenic crops. Pesticide Science 52:176–183. doi:. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walti MA, Villalba C, Buser RM, Grunler A, Aebi M, Kunzler M. 2006. Targeted gene silencing in the model mushroom Coprinopsis cinerea (Coprinus cinereus) by expression of homologous hairpin RNAs. Eukaryot Cell 5:732–744. doi: 10.1128/EC.5.4.732-744.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li M, Rollins JA. 2010. The development-specific ssp1 and ssp2 genes of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum encode lectins with distinct yet compensatory regulation. Fungal Genet Biol 47:531–538. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bleuler-Martinez S, Butschi A, Garbani M, Walti MA, Wohlschlager T, Potthoff E, Sabotic J, Pohleven J, Luthy P, Hengartner MO, Aebi M, Kunzler M. 2011. A lectin-mediated resistance of higher fungi against predators and parasites. Mol Ecol 20:3056–3070. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mine Y. 2000. Avidin, p 253–264. In Naidu AS. (ed), Natural food antimicrobial systems. CRC Press, LLC, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korpela J, Kulomaa M, Tuohimaa P, Vaheri A. 1983. Avidin is induced in chicken embryo fibroblasts by viral transformation and cell damage. EMBO J 2:1715–1719. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1983.tb01647.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green NM. 1990. Avidin and streptavidin, p 51–67. In Meir W, Edward AB (ed), Methods enzymology, vol 184 Academic Press, Cambridge, MA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elo HA, Räisänen S, Tuohimaa PJ. 1980. Induction of an antimicrobial biotin-binding egg white protein (avidin) in chick tissues in septicEscherichia coli infection. Experientia 36:312–313. doi: 10.1007/BF01952296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bleuler-Martinez S, Schmieder S, Aebi M, Kunzler M. 2012. Biotin-binding proteins in the defense of mushrooms against predators and parasites. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:8485–8487. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02286-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sabotič J, Bleuler-Martinez S, Renko M, Avanzo Caglič P, Kallert S, Štrukelj B, Turk D, Aebi M, Kos J, Künzler M. 2012. Structural basis of trypsin inhibition and entomotoxicity of cospin, serine protease inhibitor involved in defense of Coprinopsis cinerea fruiting bodies. J Biol Chem 287:3898–3907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.285304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wohlschlager T, Butschi A, Zurfluh K, Vonesch SC, Auf dem Keller U, Gehrig P, Bleuler-Martinez S, Hengartner MO, Aebi M, Kunzler M. 2011. Nematotoxicity of Marasmius oreades agglutinin (MOA) depends on glycolipid binding and cysteine protease activity. J Biol Chem 286:30337–30343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.258202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruess L, Lussenhop J. 2005. Trophic interactions of fungi and animals, p 581–598. In JD, White JF, Oudemans P (ed), The fungal community: its organization and role in the ecosystems. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crowther TW, Boddy L, Jones TH. 2011. Outcomes of fungal interactions are determined by soil invertebrate grazers. Ecol Lett 14:1134–1142. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yeates GW, Bongers T, De Goede RG, Freckman DW, Georgieva SS. 1993. Feeding habits in soil nematode families and genera—an outline for soil ecologists. J Nematol 25:315–331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ragsdale EJ, Crum J, Ellisman MH, Baldwin JG. 2008. Three-dimensional reconstruction of the stomatostylet and anterior epidermis in the nematode Aphelenchus avenae (Nematoda: Aphelenchidae) with implications for the evolution of plant parasitism. J Morphol 269:1181–1196. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Townshend JL. 1964. Fungus hosts of Aphelenchus avenae Bastian, 1865 and Bursaphelenchus fungivorus Franklin & Hooper, 1962 and their attractiveness to these nematode species. Can J Microbiol 10:727–737. doi: 10.1139/m64-092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shinya R, Hasegawa K, Chen A, Kanzaki N, Sternberg PW. 2014. Evidence of hermaphroditism and sex ratio distortion in the fungal feeding nematode Bursaphelenchus okinawaensis. G3 (Bethesda) 4:1907–1917. doi: 10.1534/g3.114.012385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walker GE. 1984. Ecology of the mycophagous nematode Aphelenchus avenae in wheat-field and pine-forest soils. Plant and Soil 78:417–428. doi: 10.1007/BF02450375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okada H, Kadota I. 2003. Host status of 10 fungal isolates for two nematode species, Filenchus misellus and Aphelenchus avenae. Soil Biol Biochem 35:1601–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2003.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cary JW, Harris-Coward PY, Ehrlich KC, Di Mavungu JD, Malysheva SV, De Saeger S, Dowd PF, Shantappa S, Martens SL, Calvo AM. 2014. Functional characterization of a veA-dependent polyketide synthase gene in Aspergillus flavus necessary for the synthesis of asparasone, a sclerotium-specific pigment. Fungal Genet Biol 64:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dietrich FS, Voegeli S, Kuo S, Philippsen P. 2013. Genomes of Ashbya fungi isolated from insects reveal four mating-type loci, numerous translocations, lack of transposons, and distinct gene duplications. G3 (Bethesda) 3:1225–1239. doi: 10.1534/g3.112.002881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takakura Y, Tsunashima M, Suzuki J, Usami S, Kakuta Y, Okino N, Ito M, Yamamoto T. 2009. Tamavidins—novel avidin-like biotin-binding proteins from the Tamogitake mushroom. FEBS J 276:1383–1397. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Christeller JT, Markwick NP, Burgess EPJ, Malone LA. 2010. The use of biotin-binding proteins for insect control. J Economic Entomology 103:497–508. doi: 10.1603/EC09149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Butschi A, Titz A, Walti MA, Olieric V, Paschinger K, Nobauer K, Guo X, Seeberger PH, Wilson IB, Aebi M, Hengartner MO, Kunzler M. 2010. Caenorhabditis elegans N-glycan core beta-galactoside confers sensitivity towards nematotoxic fungal galectin CGL2. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000717. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kumar S, Khanna A, Chandel Y. 2007. Effect of population levels of Aphelenchoides swarupi and Aphelenchus avenae inoculated at spawning on mycelial growth of mushrooms and nematode multiplication. Nematologia Mediterranea 35:155. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hooper DJ, Hallmann J, Subbotin SA. 2005. Methods for extraction, processing and detection of plant and soil nematodes, p 53–86. In Luc M, Sikora RA, Bridge J (ed), Plant parasitic nematodes in subtropical and tropical agriculture. CABI, Wallingford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walker JT, Wilson JD. 1960. The separation of nematodes from soil by a modified Baermann funnel technique. Plant Dis Rep 44:94–97. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Altmann-Jöhl R, Philippsen P. 1996. AgTHR4, a new selection marker for transformation of the filamentous fungus Ashbya gossypii, maps in a four-gene cluster that is conserved between A. gossypii and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet 250:69–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wendland J, Philippsen P. 2000. Determination of cell polarity in germinated spores and hyphal tips of the filamentous ascomycete Ashbya gossypii requires a rhoGAP homolog. J Cell Sci 113:1611–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Olausson J, Tibell L, Jonsson BH, Pahlsson P. 2008. Detection of a high affinity binding site in recombinant Aleuria aurantia lectin. Glycoconj J 25:753–762. doi: 10.1007/s10719-008-9135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Walser PJ, Haebel PW, Künzler M, Sargent D, Kües U, Aebi M, Ban N. 2004. Structure and functional analysis of the fungal galectin CGL2. Structure 12:689–702. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bleuler-Martinez S, Stutz K, Sieber R, Collot M, Mallet JM, Hengartner M, Schubert M, Varrot A, Kuzler M. 2017. Dimerization of the fungal defense lectin CCL2 is essential for its toxicity against nematodes. Glycobiology 27:486–500. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cww113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Winter HC, Mostafapour K, Goldstein IJ. 2002. The mushroom Marasmius oreades lectin is a blood group type B agglutinin that recognizes the Galα1,3Gal and Galα1,3Galβ1,4GlcNAc porcine xenotransplantation epitopes with high affinity. J Biol Chem 277:14996–15001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fujihashi M, Peapus DH, Nakajima E, Yamada T, Saito JI, Kita A, Higuchi Y, Sugawara Y, Ando A, Kamiya N, Nagata Y, Miki K. 2003. X-ray crystallographic characterization and phasing of a fucose-specific lectin from Aleuria aurantia. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 59:378–380. doi: 10.1107/S0907444902022175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wimmerova M, Mitchell E, Sanchez JF, Gautier C, Imberty A. 2003. Crystal structure of fungal lectin: six-bladed beta-propeller fold and novel fucose recognition mode for Aleuria aurantia lectin. J Biol Chem 278:27059–27067. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302642200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dunkler A, Wendland J. 2007. Use of MET3 promoters for regulated gene expression in Ashbya gossypii. Current Genetics 52:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00294-007-0134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Walti MA, Thore S, Aebi M, Kunzler M. 2008. Crystal structure of the putative carbohydrate recognition domain of human galectin-related protein. Proteins 72:804–808. doi: 10.1002/prot.22078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.