Abstract

Background:

Nurses who practice limitation of therapeutic effort become fully involved in emotionally charged situations, which can affect them significantly on an emotional and professional level.

Objectives:

To describe the experience of intensive care nurses practicing limitation of therapeutic effort.

Method:

A qualitative, phenomenological study was performed within the intensive care units of the Madrid Hospitals Health Service. Purposeful and snowball sampling methods were used, and data collection methods included semi-structured and unstructured interviews, researcher field notes, and participants’ personal letters. The Giorgi proposal for data analysis was used on the data.

Ethical considerations:

This study was approved by the Ethical Research Committee of the relevant hospital and by the Ethics Committee of the Rey Juan Carlos University and was guided by the ethical principles of voluntary enrollment, anonymity, privacy, and confidentiality.

Results:

In total, 22 nurses participated and 3 themes were identified regarding the nurses’ experiences when faced with limitation of therapeutic effort: (a) experiencing relief, (b) accepting the medical decision, and (c) implementing limitation of therapeutic effort.

Conclusion:

Nurses felt that, although they were burdened with the responsibility of implementing limitation of therapeutic effort, they were being left out of the final decision-making process regarding the same.

Keywords: End-of-life care, intensive care unit, nurse, nursing care, withholding treatment

Introduction

The main aim of intensive care units (ICUs) is to restore the health of critically ill patients with possibilities of recovery, via the use of advanced treatments and life support measures, in which technology plays an important role.1,2 The original orientation of these services toward curing illnesses is modified by two situations: first, by the need to assist people in situations of chronicity; second, because of changes that have taken place in the criteria regulating ICU admissions, for example, in the case of non-terminal cancer patients who require intensive care.3 These situations are not exempt from ethical dilemmas regarding the maintenance of life and the adoption of measures such as limitation of therapeutic effort (LTE) which is part of the role assigned to nurses in cases where patients have not benefitted from the prolongation of vital support measures. In these cases, the emphasis is placed on the provision of palliative care and comfort measures for the patient concerned.4,5

The final moments of life experienced by patients who die in the ICU are usually preceded by LTE, via the withdrawal of vital support measures and the non-initiation of the same.6 Within these units, LTE is estimated to reach percentages of over 50%.7–9 Thus, LTE represents a regular component of care provided at the end of life, together with analgesia, sedation, and basic care (i.e. hygiene measures) which guarantee a degree of comfort and are supportive of ensuring a “good death” for patients.2,10,11

However, despite representing a regular component of ICU work, Coombs et al.12 reported that ICU nurses in New Zealand experienced difficulties and were uncertain about the use of continued nutritional support, continued passive limb exercises, the use of deep sedation and the reduction of inspired oxygen for ventilated patients during final stages of life.

Two stages are distinguished within LTE: the first is related to decision-making, and the second with the execution and the application of LTE.13 The decision of implementing LTE is one of the most relevant clinical situations for health professionals due to the considerable emotional and experiential upheaval that accompanies the decision, and which can generate a great level of psychological anxiety.14,15 Subsequently, upon implementing LTE, nurses can experience substantial emotional conflict, due to their almost constant presence at the patient’s side and their involvement with families.16

Thus, Peden-McAlpine et al.17 showed that ICU nurses play an active role in decision-making processes, in order to apply LTE based on consensus and negotiations with family members. For nurses, the patient is first and foremost a person and their role is putting the medical diagnosis into the context of the patient’s biographical life. This helps the nurse facilitate a transition from care directed toward maintaining life to care directed toward comfort at the end of life.17 However, in some countries, nurses are not always able to adopt an active role in LTE. The International Nurses’ End-of-Life Decision-Making in Intensive Care Research Group analyzed nurses’ end-of-life decision-making practices in ICUs in five different cultural contexts (Brazil, England, Germany, Ireland, and Palestine).4 The research group reported that nurses do not make the “ultimate” end-of-life decisions but they seek consensus and the provision of care directed toward comforting the patient. Moreover, the research group described that there were differences regarding the power dynamics in nurse–doctor relationships, particularly in relation to the cultural perspectives on death and dying and in the development of palliative care.4 Also, Flannery et al.18 reported that there were differences in the decision-making process and the collaboration between doctors and nurses, which depended on physician preference or seniority of nurses, with overall accountability assigned to the physician. This is paradoxical, especially when the Worldwide End-of-Life Practice for Patients in Intensive Care Units (WELPICUS) study reported that critical care societies worldwide reached consensus for medical and nursing staff consensus during decision-making regarding end-of-life care. Also, the WELPICUS study reported that decision-making concerning end-of-life care should be performed by a multidisciplinary team (intensivists, intensive care nurses, and other ICU professionals) after discussions with the patient and/or the surrogate decision-maker after consensus development.13

It is important to highlight that nurses are the health professionals who are usually in-charge of implementing LTE when withdrawing devices and vital intravenous infusions.19 In these situations, prior studies have shown that nurses require a moral justification for the same, due to the fact that they associate LTE with patient’s death.20 However, not always is there a moral justification. Previous studies describe how, in LTE, nurses understand that their main role must be to facilitate a comfortable and dignified death and always try to do the right thing for the patient.11,21

Thus, LTE is a key moment in the care of the patient within the ICU and the nurse holds direct responsibility in the performance of the same.4,11,12,17 It is therefore necessary to get to know and describe LTE from the point of view of the nurse working at the ICU. The question that guides this study is what is the experience of the ICU nurse regarding the phenomenon of applying LTE and withdrawing treatment and related devices that maintain the critical patient alive? Therefore, the aim of this study was to describe the experience of ICU nurses practicing LTE.

Methods

Design

A qualitative phenomenological study was conducted based on Husserl’s framework.22 Phenomenology is a type of qualitative study that explores the experiences of people immersed in situations or phenomena (e.g. LTE). Phenomenology, which is based on experiences narrated in the first person (interviews, journals, and personal letters), attempts to understand the essence of a phenomenon.22,23 Thus, in phenomenology, two approaches in particular are influential in healthcare: (a) descriptive phenomenology has the closest connection with Husserl’s original conception of phenomenology and focuses on creating detailed descriptions of the specific experiences of others24–26 and (b) interpretative or hermeneutic phenomenology, which seeks to understand the nature of human beings and the meanings they bestow upon the world by examining language in its cultural context.22,27 Husserl indicates the need to “retain” beliefs (bracketing) which, using the phenomenological reduction approach, would allow a critical examination of the phenomena without the influence of the researcher’s own beliefs.22,24 Bracketing was performed in this study on the basis of the recommendation of gathering the experience of participants via their narratives and reflecting what is relevant for them, without the use of structured questionnaires constructed based on the opinion of experts or the literature.28

Thus, phenomenology is the appropriate design for responding to the research question and fulfilling the study aim.22 Previous studies describe the use of phenomenology for understanding the experience of the nurses facing death in ICU, and their role in the decision-making process and during withdrawal of patient’s treatment.11,21

This study consisted of two phases. In phase 1, nurses in the ICU were contacted and the study began. However, during this phase, researchers were restricted access to the unit due to organizational requirements at the hospital. This compelled the performance of a second phase, where other ICUs were included, in which nurses who fulfilled the study inclusion criteria were recruited. In the second phase, we further examined the areas of interest detected. Specific strategies were used during each phase regarding sampling, recruitment, and data collection methods.

Research team

Six researchers participated in this study, three of whom had experience in qualitative study designs (J.F.V.G., C.C.R., and D.P.C.). Five held PhDs in health sciences, were not involved in clinical activity, and had no prior relation with the participants, except one researcher (J.F.V.G.) who was working in the cardiac intensive care unit during the study. Prior to the study, the positioning of the researchers was established regarding the theoretical framework, their beliefs, prior experience, and their motivation for participating in the research.17

Context

The study setting was the Hospital Madrid Health Service. The first phase took place in the post-anesthetic reanimation unit (PARU), whereas the second phase took place in the general intensive care unit (GICU), the cardiac post-surgical care unit (CPCU), and the cardiac intensive care unit (CICU).

Participants

In phenomenological studies, it is common to include participants based on purposive sampling.22 Purposive sampling can be defined as the selection of individuals based on specific purposes associated with addressing the research study’s question or aim.29 For these reasons, a purposeful sampling method was used during phase 1, in order to recruit nurses.22,29 In phase 2, referral sampling was used, via a snowball sampling method, in order to access further participants.22 The inclusion criteria consisted of nurses with work experience in caring for critical patients equal to or greater than 1 year. Nurses with less than 1 year of work experience in these units were excluded, as well as those who had suffered personal loss during the previous 6 months and those who did not wish to participate in the study.

Data collection

Data collection was performed via audio recording the interviews, the collection of personal letters provided by the participants and the use of researcher field notes.19 Individual, unstructured interviews were performed, as well as semi-structured, face-to-face interviews. The first phase of data collection was performed via unstructured interviews based on the following opening question: what is your experience regarding LTE as an intensive care nurse? During the second phase, a question guide was elaborated (Table 1) using the data obtained in the unstructured interviews that took place in the first phase, and which were used as a basis for the format of the semi-structured interviews.22,23 In both phases, participants were invited to share personal documents such as letters and/or journals explaining their experience with LTE. Data collection based on personal documents such as letters is common in phenomenology as these reflect the vision of participants regarding their experience.22,23 These documents are included in data collection as supporting materials to complement other sources of data collection such as in-depth interviews.22,23,30 In total, 22 in-depth interviews were performed, 5 non-structured interviews in phase 1, and 17 semi-structured interviews in phase 2, and 2 personal letters were gathered (participant no. 1 and 22; Table 2). Participant recruitment ended when the information gained from the interviews became repetitive.22 This was achieved upon the interview of participant no. 17. The researchers then decided by consensus to continue data collection and the inclusion of participants until participant no. 22, in order to confirm the redundancy of information.

Table 1.

Semi-structured interview question guide.

| Research area | Questions |

|---|---|

| Practice and content of LTE | What does LTE consist of within your unit? How do you practice LTE with patients? |

| Decision on LTE | How is LTE decided and by whom? What relevance is given to the nurse when it comes to deciding LTE? |

| LTE implementation | In your opinion, what is the most relevant aspect when implementing LTE? What are your feelings and emotions when implementing LTE? Do you have any difficulty practicing LTE? If so, of what sort? |

| The nurse’s role in LTE | What do you believe should be the role of the nurse in LTE? |

LTE: limitation of therapeutic effort.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the data collection.

| Phase 1 | Phase 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of interview | Unstructured | Semi-structured |

| No. of interviews | 5 | 17 |

| Personal letters | 1 | 1 |

| Mean duration in minutes (standard deviation) | 53.4 (4.66) | 55.18 (8.27) |

Data analysis

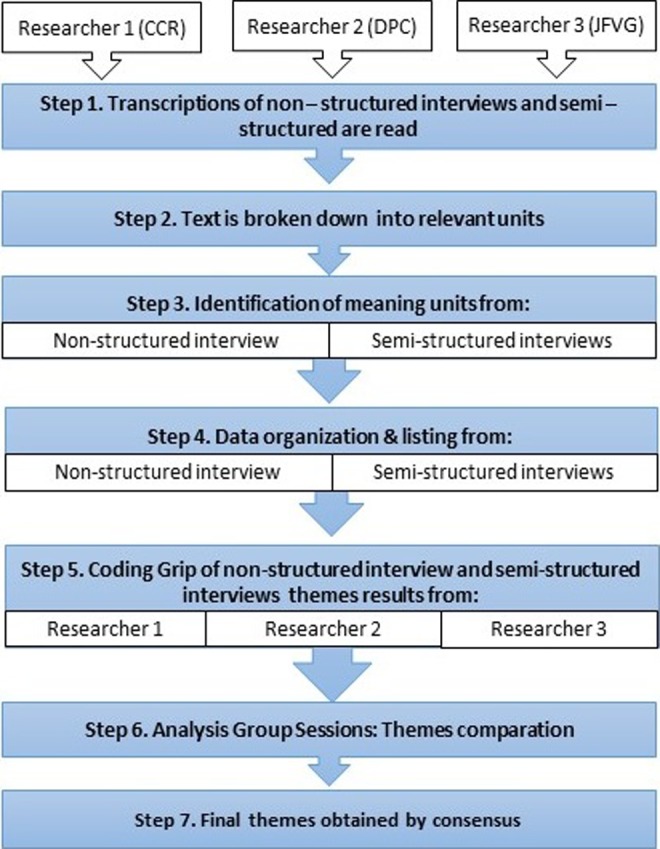

Giorgi’s31 proposal was used in this study to guide the process of data analysis. This model distinguishes five stages of data processing: (a) data collection, (b) reading prior literal transcription of the interviews, (c) breaking down the descriptions into separate units in order to identify the relevant meaning units for the phenomenon under study, (d) data organization and listing from the perspective of the discipline using a process of encoding, and finally, (e) data synthesis and summarization in order to communicate these to the scientific community. The interviews were analyzed simultaneously, and separately, by three of the researchers (C.C.R., D.P.C., and J.F.V.G.).

Afterwards, the data obtained were analyzed separately for both the unstructured and semi-structured interviews. Subsequently, in both phases, a coding grid was created with the meaning units, their groups, and the identified themes. Within this grid, the narrations that justified the results obtained were identified.32 Thereafter, group sessions were performed among the researchers, during which the themes of both phases demonstrating the nurses’ experiences were analyzed and compared. Finally, the final themes were obtained, similarly integrating the narratives from the unstructured and semi-structured interviews. The final themes were decided via researcher consensus (Figure 1).22

Figure 1.

Description of the data analysis process.

Rigor

The quality of the study was guaranteed following the recommendations for qualitative studies developed by the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ).33 Also, the criteria for guaranteeing trustworthiness as cited by Guba and Lincoln34 were followed (Table 3) according to the credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability of the data.22,35

Table 3.

Trustworthiness criteria.

| Criteria | Techniques performed and application procedures |

|---|---|

| Credibility |

Investigator triangulation: each interview was analyzed by three researchers. Thereafter, team meetings were performed in which the analyses were compared and categories were identified. Participant triangulation: the study included participants belonging to different intensive care units. Thus, multiple perspectives were obtained with a common link (the experience of applying LTE in ICUs). Triangulation of methods of data collection: both unstructured and semi-structured interviews were conducted and researcher field notes were kept. Participant validation: this consisted of asking the participants to confirm the data obtained at the stages of data collection and analysis. |

| Transferability | In-depth descriptions of the study performed, providing details of the characteristics of researchers, participants, contexts, sampling strategies, and the data collection and analysis procedures. |

| Dependability | Audit by an external researcher: an external researcher assessed the study research protocol, focusing on aspects concerning the methods applied and study design. |

| Confirmability | Investigator triangulation, participant triangulation, and data collection triangulation. Researcher reflexivity was encouraged via the performance of reflexive reports and by describing the rationale behind the study. |

Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethical Research Committee of the relevant hospital and by the Ethics Committee of the Rey Juan Carlos University. Informed consent, both verbal and written, was sought from all participants. Confidentiality was preserved at all times during personal data collection and data processing and, therefore, such data were only accessible by the research team. All nurses granted permission to record the interviews.

Results

The mean age of the nurses was 40.8 years (±8.03), and their mean professional experience in ICUs was 13.6 years (±7.63). The participant distribution by gender was 15 women (68.2%) and 7 men (31.8%).

Three main themes were identified based on the findings regarding the lived experiences of nurses23,30 dealing with LTE within ICUs: (a) experiencing relief, (b) accepting the medical decision, and (c) implementing LTE.

Experiencing relief

This refers to the feeling of relief and calm experienced by nurses after the death of patients who have received LTE after prolonged treatment. From the nurses’ point of view, at times, patients are made to suffer without reason:

…in almost all cases I feel a sense of relief, there are patients who I would have limited long before in order to avoid therapeutic obstinacy. (P19, female, 32 years)

…sometimes care is excessively prolonged, and regarding medical care (…) I feel that maintaining it ends up doing more harm to both the family and the patient; it is a way of maintaining a total and absolute agony. It is exhausting. (P3, female, 45 years)

Nurses questioned the usefulness of certain treatments which, from their point of view, do not lead to a cure and only serve to prolong a situation which is void of sense: “…very often I feel that everything we have done has been to no avail” (P6, male, 41 years), “…as soon as there is no way to cure a patient, when you truly see there is no way out, you ask yourself: why continue doing this?” (P2, female, 51 years):

…I have many years’ experience and I have seen many cases in which diagnoses and illnesses are repeated, and you start to see that, in the end, they end up dying, and you say to yourself: why prolong this? If the person is to die: what is the need for so much suffering? Why are so many invasive interventions performed? (P18, female, 43 years)

Faced with these situations, nurses highlight the need for LTE: “…therapeutic limitation is something that must exist, medicine is not infallible and sometimes the patient does not respond appropriately to treatments” (P4, female, 46 years), “…when you have done everything you can for a patient, you have to stop. It is another form of treatment” (P9, female, 43 years).

Accepting the medical decision

This refers to the decision-making process surrounding LTE and the nurse’s role in decision-making. Nurses reported that decisions are taken exclusively by doctors, together with the patient’s family, and that nurses are left out of the process: “…we do not participate, neither are we asked, doctors are quite reluctant to you suggesting whether or not to limit a patient” (P13, male, 28 years), “…the decision is made by doctors in clinical sessions via a consensus of opinions in favor of therapeutic limitation. If there are differing opinions, possible alternative treatments are analyzed with the family” (P22, male, 31 years).

The lack of nurse participation in the decision-making process generates discontent; at the same time, they demand a greater say as they are the professionals who spend the most time at the patients bedside: “…I feel bad, you are the one who really goes through the families’ emotional upheaval, we are the ones who have to provide support and they ought to consider us more” (P4, female, 46 years), “…we have no say, but we should participate as we are the ones living with the patients, maybe we can contribute something; all I ask is that they listen” (P7, male, 42 years).

On some occasions, nurses provided their opinion in an informal or indirect manner, with doctors with whom they shared greater trust or proximity:

…in decision-making, the nurse is an element that is completely on the sidelines, at least formally. I don’t really know how much the comments we make end up having any influence, however that certainly is not the formal question. Rather, it depends on how well you get on with the doctor. (P6, male, 41 years)

…you can offer your opinion, I have been working here for 20 years and I have a great relation and trust with them. I am not saying that they consider what I have to say, I can comment on these issues with the doctor, but it isn’t anything official or protocolized, like comments made during a clinical team meeting. (P15, female, 49 years)

However, the nurses emphasize the lack of clear criteria and consensus on behalf of the care team regarding LTE decisions:

…not all patients are managed in the same way, some doctors are more inclined to immediately remove treatment, while others choose to withdraw it too late. There are too many internal struggles between them for something standard to be put into place. (P7, male, 42 years)

“…when to limit treatment? There are no clear clinical criteria in place for this or we aren’t prepared for it” (P6, male, 41 years), “…depending on the doctor and to what extent he is in favor of maintaining treatment, one or another type of measure is applied” (P15, female, 49 years).

This situation leads to a feeling of being the patient’s defenders or safeguarders, deciding what is best for patients for their comfort, and especially in order to try and protect them from what can hurt them, be harmful, or generate pain. The nurse is the professional who spends the most time with the patient, providing 24-h coverage to meet patient’s needs and who interacts the most with the family. Paradoxically, nurses are not included in decision-making, and neither their criteria nor their experience are considered.

Implementing LTE

This theme concerns nurses’ experiences applying LTE, and the withdrawal of life support measures (devices and drugs), especially when the time comes to remove mechanical ventilation and the endotracheal tube. In these cases, nurses not only feel that there is no treatment applied but rather that they are fulfilling an order that hastens the patient’s death. They feel like executioners:

…the role that we have is a bit like executioners, the doctor gives the order and I am the one who follows it through. They make the decision, but you’re the one who connects the drip, you’re the one who removes the tube. (P8, male, 32 years)

Some nurses can end up feeling responsible for the patient’s death as they are the ones who apply the LTE: “…removing the endotracheal tube, it is as if I am doing them in, if I remove it the patient dies…in the beginning you feel like you are killing the person. It’s tough” (P18, female, 43 years).

On some occasions, participants described feeling unable to limit treatments and apply other prescriptions such as pharmacological sedation:

…I have colleagues who develop immense attachment to their patients; they know that if they administer that morphine derived drug it is in order to limit treatment and afterwards the patient will not awake, and so, due to this emotional attachment, they can’t do it. (P9, female, 43 years)

At times, nurses worry about how the families view them during the withdrawal of life support measures:

…they tell me to remove the tube, remove the noradrenaline, and I do it. I don’t mind. I do mind that the family sees me doing it, it’s as if they were saying, here comes the executioner who is going to take our father or mother from us, to do in my family member. (P15, female, 49 years)

Discussion

For the nurses, LTE can involve important ethical conflicts related to the role of carer.11,12,36,37 These ethical conflicts consisted in the fact that the order of withdrawing life support, on occasions, entails the non-application of care measures that could have been maintaining the patients comfort, such as analgesia, postural mobilizations, and nutrition.11,37 In a study by Coombs et al.,12 over half of the nurses surveyed (55%, n = 111) disagreed that withholding and withdrawing life support treatment were ethically the same thing and 78% (n = 159) of nurses felt that withholding treatment was ethically more acceptable than withdrawing the same.

Our findings reveal that nurses feel both like the patient’s executioner and advocate. This role is included within the nurse’s responsibility of defending the patient’s best interests within the ICU and guaranteeing a death with dignity and comfort.11,19,37,38 The role of advocate or protector may be explained by the fact that, on occasion, nurses encounter physicians who provide patients and their families with a false picture of recovery or, worse, block any end-of-life discussions.39

Other reasons that may justify the appearance of the roles of “executioner” and “advocate” within our findings may be due to the imbalance that exists in relations between doctors and nurses when taking decisions. Interprofessional collaboration has demonstrated to be an instrument that improves the attention of patients in ICU, decreasing complications and improving the confidence, communication, and relation between doctors and nurses.40,41 The ideal “unified” team working together to provide better care and improve patient outcomes may be difficult to sustain41 due to the fact that in ICU settings, teams continuously vary due to large staff numbers, shift work, and staff rotations throughout the institution. Rose describes how this collaboration must be based on mutual respect and power sharing in decision-making.41 Also, collaboration, by definition, implies interdependency as opposed to autonomy. In fact, autonomy of healthcare professionals may be an inappropriate goal when striving to foster interprofessional collaboration. In contrast, another factor that may justify this difference of power between doctors and nurses is gender. Zelek and Phillips42 report how when nurses and doctors are female, traditional power imbalances in their relationship diminish, suggesting that these imbalances are based as much on gender as on professional hierarchy.

The feeling of relief that often accompanies treatment withdrawal in the case of therapy that professionals consider to be useless appears in other studies.43,44 In contrast, in the study by Browning45 on the end-of-life care provided by ICU nurses, they described feelings of frustration, helplessness, or moral anguish when faced with life-sustaining treatments provided in the absence of justified clinical motives. Throughout this study, nurses reported a feeling of guilt surrounding the death of patients under their care when the time came to withdraw treatment. Nurses regarded themselves as the patients’ “executioners,” which coincided with the results by Espinosa et al.19 According to Gélinas et al.,44 feelings of guilt can make a nurse request a transfer to other units or even lead to them quitting their profession. This is one of the motives for which authors such as Bloomer et al.46 recommend that, faced with specific patients in ICU terminal situations, the nurses responsible for their care should have specific psychosocial skills and expertise. Parker47 describes seven steps that a nurse must go through when applying treatment withdrawal in order to provide a good death. These are: nurses must talk with family members, ensure all orders are written, prepare drugs, decide whether to extubate or not, decide whether or not to connect the monitor, ensure readiness, and proceed. In contrast, Ranse et al.48 offer quite a different view, whereby the fact of having to manage these situations is seen as an “honor” and a “privilege” of ICU nurses.

However, our findings highlight a lack of participation experienced by nurses regarding decision-making, which is in line with other prior studies.6,49 Langley et al.49 describe how 71% of nurses affirm their non-participation in end-of-life decision-making. Kranidiotis et al.7 associate this with the fact that the doctor takes on a dominant role in the decision-making. In contrast, nurses benefit from a closer relation with the patient and the family, and their interaction with the entire ICU team puts them in an ideal position to be able to identify early on any lack of effectiveness regarding the prescribed medical treatment.50,51 Randall and Vicent52 argue that shared decision-making policies improve the work environment, decrease burden, and help avoid conflicts, besides decreasing the discontent of nurses who may otherwise feel they are being excluded.53

Our results show that nurses attempt to give their opinion and share their experience with doctors, based on the trust or proximity, which are aspects that could be considered as informal information channels.54 The results by Gallagher et al.4 are in contrast with our findings, as in their study, they found that the opinion of experienced nurses is considered by doctors. Gálvez et al.38 claim that the nurse with experience collaborates subtly in decisions and is also consulted, as they are considered to be trustworthy and experienced. The lack of nurse participation found in our study may be explained by the fact that there are differences between nurses and intensivists in their perception of collaboration and other aspects of withholding and withdrawing therapy practices in the ICU (philosophy of care, objectives, and professional responsibilities),11,54 which may influence their involvement in decision-making.13,55,56 Thus, Espinosa et al.19 describe how the Hippocratic model, which is the base for medical acts, dictates that the doctor is the only professional with “enough wisdom” to treat illness and is the person who is ultimately responsible for the derived decisions.

Finally, nurses reported that the application of LTE can vary in a single patient, according to the criteria of each doctor. Wilson et al.55 agree with our findings by identifying how the work environment, professional experience, attitudes of each doctor, their values, and relations with the family can all influence the decision-making process and the change of criteria for applying LTE. This situation can generate conflicts between professionals and family due to the fact that the treatment objectives are not altogether clear due to constant changes in the measures to be taken.21 Another argument is that unilateral decision-making on behalf of doctors is justified, and as such, these decisions should be communicated to the rest of the ICU team, as an absence of the same may generate confusion in the patient, their family, and the nurse staff.44,55 An example of this is that on occasion, the role of the nurse when withdrawing treatment is not fully understood or can be misinterpreted by the family.57

Finally, Spanish law58,59 states that the diagnosis, treatment, and information of the whole process of illness is the doctor’s responsibility. Our results, together with other international recommendations such as the WELPICUS study,13 reinforce the need for working in multidisciplinary teams in which the relationship between the doctor and nurse plays a significant role in end-of-life decision-making. Although laws define the legal framework which professionals should abide by, this is not incompatible with the creation of protocols and clinical guidelines that may be able to develop a way of working focused on the well-being of the ill at the end of the person’s life.

Limitations

One of the study researchers (J.F.V.G.) worked as an ICU nurse at one of the units included in the first part of the study. This potential limitation was resolved in the study design, as the interviews with the nurses of the aforementioned unit were conducted by other members of the research team. Also, this study focused solely on the experiences of the ICU nurses caring for adult patients. The authors believe that the experience of pediatric ICU has specific considerations which can influence the LTE experience and the nurses.60

At times, the nurses feel relieved with the decision of LTE when faced with situations of therapeutic futility; however, feelings of guilt can appear and some nurses may even feel like an “executioner” when applying these measures. Nurses adopt the role of advocate for the patient’s best interests regarding medical treatment in the ICU.

These results serve to develop protocols on decision-making processes regarding LTE, the inclusion of nurses in the same, and the application of support and follow-up programs for ICU nurses who perform LTE. Furthermore, it is necessary to develop studies that research the effects of LTE implementation on behalf of ICU nurses and its emotional impact, together with the perspective of family members regarding LTE as performed by nurses on the ICU. Special consideration is warranted both in research and practice for the development of protocols and guidelines that are able to help ICU nurses to better understand and develop their role in providing end-of-life care after treatment withdrawal and to reduce ambiguity and support the delivery of care for adults as they approach the final stages of life in ICUs.

Acknowledgements

The research team would like to thank the nursing research units from both the hospital and the Madrid Red Cross Nursing College for their support.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Raquel González-Hervías, Escuela de Enfermería de Cruz Roja de Madrid, Spain.

César Cardenete-Reyes, Universidad Europea de Madrid, Spain.

Beatriz Álvarez-Embarba, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Spain.

Domingo Palacios-Ceña, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Spain.

References

- 1. Cook D, Rocker G. Dying with dignity in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 2506–2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kryworuchko J, Stacey D, Peterson WE, et al. A qualitative study of family involvement in decisions about life support in the intensive care unit. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2012; 29(1): 36–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fernandez R, Gonzalez FB, Raventos A. Limitation of therapeutic effort in intensive care: has it changed in the XXI century? Med Intensiva 2005; 29(6): 338. [Google Scholar]

- 4. International Nurses’ End-of-Life Decision-Making in Intensive Care Research Group; Gallagher A, Bousso RS, McCarthy J, et al. Negotiated reorienting: a grounded theory of nurses’ end-of-life decision-making in the intensive care unit. Int J Nurs Stud 2015; 52(4): 794–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Borsellino P. Limitation of the therapeutic effort: ethical and legal justification for withholding and/or withdrawing life sustaining treatments. Multidiscip Respir Med 2015; 10(1): 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Groselj U, Orazem M, Kanic M, et al. Experiences of Slovene ICU physicians with end-of-life decision making: a nation-wide survey. Med Sci Monit 2014; 20: 2007–2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kranidiotis G, Gerovasili V, Tasoulis A, et al. End-of-life decisions in Greek intensive care units: a multicenter cohort study. Crit Care 2010; 14(6): R228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Real de Asúa D, Alcalá-Zamora J, Reyes A. Evolution of end-of-life practices in a Spanish intensive care unit between 2002 and 2009. J Palliat Med 2013; 16(9): 1102–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lesieur O, Leloup M, Gonzalez F, et al. Withholding or withdrawal of treatment under French rules: a study performed in 43 intensive care units. Ann Intensive Care 2015; 5(1): 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kongsuwan W, Chaipetch O. Thai Buddhists’ experiences caring for family members who died a peaceful death in intensive care. Int J Palliat Nurs 2011; 17(7): 329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Efstathiou N, Walker W. Intensive care nurses’ experiences of providing end-of-life care after treatment withdrawal: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs 2014; 23(21–22): 3188–3196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Coombs M, Fulbrook P, Donovan S, et al. Certainty and uncertainty about end of life care nursing practices in New Zealand Intensive Care Units: a mixed methods study. Aust Crit Care 2015; 28(2): 82–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sprung CL, Truog RD, Curtis JR, et al. Seeking worldwide professional consensus on the principles of end-of-life care for the critically ill. The Consensus for Worldwide End-of-Life Practice for Patients in Intensive Care Units (WELPICUS) study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 190(8): 855–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mealer M, Jones J, Moss M. A qualitative study of resilience and posttraumatic stress disorder in United States ICU nurses. Intensive Care Med 2012; 38: 1445–1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Quenot JP, Rigaud JP, Prin S, et al. Suffering among carers working in critical care can be reduced by an intensive communication strategy on end-of-life practices. Intensive Care Med 2012; 38(1): 55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Valiee S, Negarandeh R, Dehgan Nayeri N. Exploration of Iranian intensive care nurses’ experience of end-of-life care: a qualitative study. Nurs Crit Care 2012; 17: 309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peden-McAlpine C, Liaschenko J, Traudt T, et al. Constructing the story: how nurses work with families regarding withdrawal of aggressive treatment in ICU: a narrative study. Int J Nurs Stud 2015; 52(7): 1146–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Flannery L, Ramjan LM, Peters K. End-of-life decisions in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU)—exploring the experiences of ICU nurses and doctors—a critical literature review. Aust Crit Care 2016; 29(2): 97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Espinosa L, Young A, Symes L, et al. ICU nurses’ experiences in providing terminal care. Crit Care Nurs Q 2010; 33(3): 273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Birchley G. Angels of mercy? The legal and professional implications of withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment by nurses in England and Wales. Med Law Rev 2012; 20(3): 337–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vanderspank-Wright B, Fothergill-Bourbonnais F, Brajtman S, et al. Caring for patients and families at end of life: the experiences of nurses during withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment. Dynamics 2011; 22(4): 31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carpenter C, Suto M. Qualitative research for occupational and physical therapists: a practical guide. Oxford: Wiley-BlackWell, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Norlyk A, Harder I. What makes a phenomenological study phenomenological? An analysis of peer-reviewed empirical nursing studies. Qual Health Res 2010; 20(3): 420–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Giorgi A. The phenomenological movement and research in the human sciences. Nurs Sci Q 2005; 18: 75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Giorgi A. The status of Husserlian phenomenology in caring research. Scand J Caring Sci 2000; 14: 3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Giorgi A. Concerning the application of phenomenology to caring research. Scand J Caring Sci 2000; 14: 11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dowling M. From Husserl to van Manen. A review of different phenomenological approaches. Int J Nurs Stud 2007; 44(1): 131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gearing RE. Bracketing in research: a typology. Qual Health Res 2004; 14: 1429–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Teddlie C, Yu F. Mixed methods sampling: a typology with examples. J Mix Method Res 2007; 1(1): 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kleiman S. Phenomenology: to wonder and search for meanings. Nurse Res 2004; 11(4): 7–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Giorgi A. The theory, practice, and evaluation of the phenomenological method as a qualitative research procedure. J Phenomenol Psychol 1997; 28(2): 235–260. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health C 2007; 19(6): 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shenton AK. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educ Inform 2004; 22: 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 36. McLennan S, Celi LA, Gillett G, et al. Nurses share their views on end-of-life issues. Nurs N Z 2010; 16(4): 12–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Birchley G. Doctor? Who? Nurses, patient’s best interests and treatment withdrawal: when no doctor is available, should nurses withdraw treatment from patients? Nurs Philos 2013; 14(2): 96–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gálvez M, Ríos F, Fernández L, et al. The end of life in the intensive care unit from the nursing perspective: a phenomenological study. Enferm Intensiva 2011; 22(1): 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Borowske D. Straddling the fence: ICU nurses advocating for hospice care. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 2012; 24(1): 105–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Orchard CA. Persistent isolationist or collaborator? The nurse’s role in interprofessional collaborative practice. J Nurs Manag 2010; 18(3): 248–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rose L. Interprofessional collaboration in the ICU: how to define? Nurs Crit Care 2011; 16(1): 5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zelek B, Phillips SP. Gender and power: nurses and doctors in Canada. Int J Equity Health 2003; 2(1): 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Calvin O, Kite-Powell M, Hickey V. The neuroscience ICU nurse’s perceptions about end-of-life care. J Neurosci Nurs 2007; 39(3): 143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gélinas C, Fillion L, Robitaille A, et al. Stressors experienced by nurses providing end-of-life palliative care in the intensive care unit. Can J Nurs Res 2012; 44(1): 18–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Browning A. Moral distress and psychological empowerment in critical care nurses caring for adults at end of life. Am J Crit Care 2013; 22(2): 143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bloomer J, Morphet J, O’Connor M, et al. Nursing care of the family before and after a death in the ICU: an exploratory pilot study. Aust Crit Care 2012; 26(1): 23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Parker L. Practical steps for discontinuation of life-sustaining treatment. Dynamics 2011; 22(4): 38–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ranse K, Yates P, Coyer F. End-of-life care in the intensive care setting: a descriptive exploratory qualitative study of nurses’ beliefs and practices. Aust Crit Care 2012; 25(1): 4–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Langley G, Schmollgruber S, Fulbrook P, et al. South African critical care nurses’ views on end-of-life decision-making and practices. Nurs Crit Care 2014; 19(1): 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Monteverde S. The importance of time in ethical decision making. Nurs Ethics 2009; 16(5): 613–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Damghi N, Belayachi J, Aggoug B, et al. Withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining therapy in a Moroccan Emergency Department: an observational study. BMC Emerg Med 2011; 11(1): 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Randall J, Vincent JL. Ethics and end-of-life care for adults in the intensive care unit. Lancet 2010; 376(9749): 1347–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. McCallum A, McConigley R. Nurses’ perceptions of caring for dying patients in an open critical care unit: a descriptive exploratory study. Int J Palliat Nurs 2013; 19(1): 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Albers G, Francke AL, de Veer AJ, et al. Attitudes of nursing staff towards involvement in medical end-of-life decisions: a national survey study. Patient Educ Couns 2014; 94(1): 4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wilson ME, Rhudy LM, Ballinger BA, et al. Factors that contribute to physician variability in decisions to limit life support in the ICU: a qualitative study. Intensive Care Med 2013; 39(6): 1009–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jensen HI, Ammentorp J, Erlandsen M, et al. Withholding or withdrawing therapy in intensive care units: an analysis of collaboration among healthcare professionals. Intensive Care Med 2011; 37(10): 1696–1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hyde YM, Kautz DD, Jordan M. What to do when the family cannot agree to withdraw life support. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2013; 32(6): 276–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Spanish Goverment Bulletin. Ley 14/1986, de 25 de abril, General de Sanidad [Spanish Health Law], https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/1986/BOE-A-1986-10499-consolidado.pdf (1986, accessed 3 October 2016).

- 59. Spanish Goverment Bulletin. Real Decreto 63/1995, de 20 de enero, sobre ordenación de prestaciones sanitarias del Sistema Nacional de Salud [Regulations of Management of Health Services of the Spanish National Health System], https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/1995/02/10/pdfs/A04538-04543.pdf (1995, accessed 3 October 2016).

- 60. Howes C. Caring until the end: a systematic literature review exploring Paediatric Intensive Care Unit end-of-life care. Nurs Crit Care 2015; 20(1): 41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]