Abstract

Background

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a common pathogen causing pneumonia; macrolide‐resistant strains are rapidly spreading across Japan. However, the clinical features of macrolide‐resistant M. pneumoniae pneumonia have not been well established. Here, we evaluated the clinical characteristics and seasonal variations in the prevalence of M. pneumoniae with macrolide‐resistant mutations (MRM).

Methods

The monthly prevalence of MRM in M. pneumoniae strains isolated from May 2016 to April 2017 was retrospectively analyzed, and the clinical characteristics of pneumonia cases with MRM were compared to those of cases without MRM. The M. pneumoniae isolates and point mutations at site 2063 or 2064 in domain V of 23S rRNA were evaluated by the GENECUBE system and GENECUBE Mycoplasma detection kit.

Results

Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection was identified in 383 cases, including 221 cases of MRM (57.7%). The MRM prevalence was 86.3% (44/51) between May and July 2016, demonstrating an apparent decrease in September 2016, subsequently reaching 43.0% (34/79) in November 2016. Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia was diagnosed in 275 cases, including 222 pediatric and 53 adult cases. Macrolide use preceding evaluation was found to be the only feature of MRM pneumonia cases both in children (odds ratio [OR] 3.86, 95% confidence interval [CI]:1.72–8.66) and in adults (OR 7.43, 95% CI: 1.67–33.1).

Conclusions

The determination rate of MRM varied widely throughout the year, and our study demonstrated the challenges in predicting M. pneumoniae with MRM based on clinical features at diagnosis. Therefore, continuous monitoring of the prevalence of MRM is warranted, which may help in selecting an effective treatment.

Keywords: GENECUBE, macrolide resistance, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, point‐of‐care molecular testing, prevalence

1. INTRODUCTION

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is one of the most common pathogens in community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP), determined in 41.1% of pediatric and 13.0% of adult CAP cases in Japan.1, 2 Most available antimicrobial agents, especially beta‐lactam agents,3 are not effective against M. pneumoniae;4 thus, risk factors and clinical manifestations have been intensively investigated. Till date, school‐aged children and adolescents,3 persistent cough,5 vomiting or diarrhea,6 and autumn or winter outbreak7 have been identified as factors associated with M. pneumoniae infections.

Macrolides are used as the first‐line therapy for the treatment of M. pneumoniae infections, especially in children, owing to their high efficacy8 and safety profile.9, 10 However, macrolide resistance of M. pneumoniae, which is acquired by mutations of the ribosomal target of macrolides,11 has been spreading rapidly and widely since 2000,12 resulting in enhanced disease severity with increased complications.13, 14

The prevalence of macrolide‐resistant M. pneumoniae is 23.3%‐100% in East Asian regions, 3.5%‐13.2% in North America, and below 10% in European countries, except Italy, which has a higher rate of 26%.11 Tanaka et al15 reported a year‐by‐year variation in the prevalence of macrolide‐resistant M. pneumoniae in Japan, demonstrating an increase from 55.6% to 81.6% between 2008 and 2012, with a gradual decrease thereafter, reaching 43.6% by 2015. Despite this decrease, the macrolide resistance rate of M. pneumoniae remains high in Japan, and its clinical importance is unaltered. However, the clinical features of macrolide‐resistant M. pneumoniae at diagnosis are not well established, making it difficult to predict before starting treatment.

To improve the diagnosis and management of macrolide‐resistant M. pneumoniae pneumonia, this study aimed to determine the seasonal trend in the determination rate of macrolide‐resistant mutations (MRM) among 383 M. pneumoniae cases diagnosed within a single year (2016/2017). We further compared the clinical characteristics of M. pneumoniae pneumonia cases according to the presence of MRM evaluated by the GENECUBE system and GENECUBE Mycoplasma detection kit.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tsukuba Medical Center Hospital (TMCH; 453 beds), an acute care teaching hospital located in Tsukuba city in Japan, is the primary pediatric emergency center and tertiary emergency medical center in the southern part of the Ibaraki Prefecture. We retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of cases with a positive M. pneumoniae result determined by a molecular identification system (GENECUBE, TOYOBO, Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) at TMCH between May 2016 and April 2017. This study was approved by the ethics committee of TMCH (approval number: 2016‐043).

2.1. Definition of pneumonia and evaluation of data

The diagnosis of pneumonia was made based on radiological findings and clinical symptoms compatible with pneumonia, without other causes attributed to abnormal radiological findings.16, 17 The radiological finding was reviewed by two independent physicians, and only cases diagnosed as pneumonia by both physicians were included as pneumonia cases. Discordant cases were further reviewed by a board‐certified radiologist to make a final diagnosis.

For background data, we collected information on age, gender, comorbidities, evaluation month, history of preceding antimicrobial use, history of symptoms (rhinorrhea, sputum or productive cough, severe cough, hypoxia, diarrhea, skin rashes, high fever [≥38°C]), crackles upon chest auscultation at presentation, duration of symptoms at examination, laboratory findings (white blood cell count [WBC] and C‐reactive protein values [CRP]) obtained on the previous or same day of the molecular examination, sources of infections, and requirement of hospitalization before or at presentation. Cases were regarded as having comorbidities when they were diagnosed with chronic diseases defined by the Charlson comorbidity index18 or equivalent. A severe cough was defined as a cough with vomiting, sleep disturbance, or a constant cough. Hypoxia was defined as a peripheral capillary oxygen saturation level <90% or partial arterial pressure of oxygen <60 mm Hg.

2.2. Molecular diagnosis of M. pneumoniae and identification of MRM

Samples were obtained from the oropharynx using FLOQSwabs 5U005S dual (Sin Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and were used for molecular examination of M. pneumoniae with the GENECUBE system and GENECUBE Mycoplasma detection kit at TMCH, which has been approved in Japan since 2015. In addition to the presence of M. pneumoniae, point mutations at domain V of the 23S ribosomal RNA gene (2063 and 2064) of M. pneumoniae were analyzed simultaneously with melting curve analysis using the previously validated quenching probe method.19

2.3. Statistical analyses and data evaluation

We compared the clinical characteristics between M. pneumoniae pneumonia cases with and without MRM. This comparison was performed separately for pediatric cases (<18 years of age) and adult cases (≥18 years). Categorical variables were compared using Fisher's exact test, and continuous variables were analyzed using the Mann‐Whitney U test. Variables with a significant association (P < 0.05) in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis after considering potentially confounding factors. All statistical analyses were performed using R 3.3.1.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Monthly trends in the number of cases infected with M. pneumoniae harboring MRM

We examined 1307 individual cases for the determination of M. pneumoniae using the GENECUBE system and GENECUBE Mycoplasma detection kit between May 2016 and April 2017; M. pneumoniae was identified in a total of 384 cases. Of these, one case was excluded from our study because colonization was highly suspected. Therefore, we included a total of 383 M. pneumoniae infection cases in the final analysis.

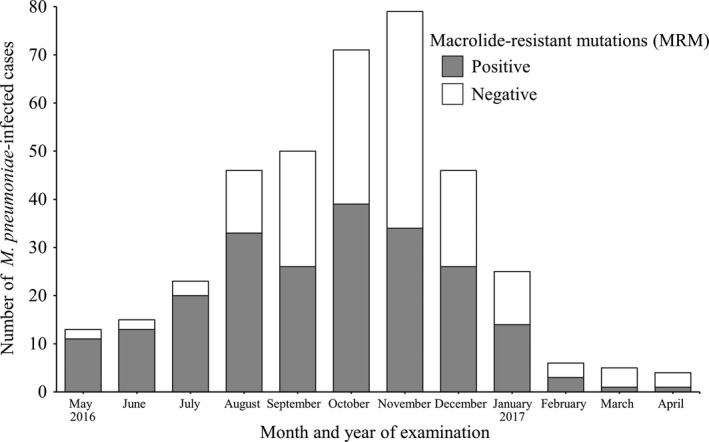

Figure 1 depicts the monthly trends of the number of M. pneumoniae infection cases with and without MRM. The number of M. pneumoniae infection cases markedly increased as of August, with 71 cases recorded in November 2016, which is in line with the number of reported cases of M. pneumoniae pneumonia in Ibaraki Prefecture.20

Figure 1.

Seasonal change in the number of Mycoplasma pneumoniae‐infected cases and the proportion of cases with macrolide‐resistant mutations (MRM)

In total, MRM was determined in 221 cases (57.7%) with high monthly variation. MRM was identified in 86.3% of cases (44/51 cases) between May and July, which apparently decreased as of September, reaching 43.0% (34/79 cases) in November 2016.

3.2. Demographic data of all cases infected with M. pneumoniae

Table 1 summarizes the demographic data of all 383 M. pneumoniae infection cases. The median age was 8.0 years (47.8% female), and a large majority of cases (>80%) was pediatric. Asthma was the most common comorbidity identified (11.2%). Antimicrobials were prescribed for over half of the cases before evaluation, with the majority prescribed macrolides (29.2%), and the median duration from symptom onset to evaluation was 7.0 days. Among the observed clinical signs and symptoms, fever ≥38°C was the most frequent, followed by sputum or productive cough, severe cough, rhinorrhea, crackles auscultated upon chest examination, diarrhea, skin rashes, and hypoxia. The median WBC count and CRP values were 7100/μL and 2.20 mg/dL, respectively. Pneumonia was the most common diagnosis and accounted for 275 cases (71.8%). There was no mortality in any of the cases included in this study, whereas 23.0% of the cases required hospitalization on the day of or before evaluation.

Table 1.

Demographic data of all cases of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection with and without macrolide‐resistant mutations

| Total | Macrolide‐resistant mutations | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| N | 383 | 221/383 | 162/383 |

| Age (y) | 8.0 [5.0‐13.0] | 7.0 [5.0‐12.0] | 9.0 [5.0‐16.0] |

| Children (<18 y old) | 315 (82.2) | 190 (86.0) | 125 (77.2) |

| Female | 183 (47.8) | 101 (45.7) | 82 (50.6) |

| Comorbidities | 54 (14.1) | 22 (10.0) | 32 (19.8) |

| Asthma | 43 (11.2) | 18 (8.1) | 25 (15.4) |

| Immunosuppressive state | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Preceding antimicrobial use | 214 (55.9) | 148 (67.0) | 66 (40.7) |

| Macrolides | 112 (29.2) | 93 (42.1) | 19 (11.7) |

| Quinolones/Tetracyclines | 65 (17.0) | 46 (20.8) | 19 (11.7) |

| Onset to evaluation (d) | 7.0 [5.0‐8.0] | 7.0 [6.0‐8.0] | 6.0 [4.0‐8.0] |

| Rhinorrhea | 64 (16.7) | 31 (14.0) | 33 (20.4) |

| Sputum or productive cough | 98 (25.6) | 56 (25.3) | 42 (25.9) |

| Severe cough | 90 (23.5) | 48 (21.7) | 42 (25.9) |

| Hypoxia | 9 (2.3) | 4 (1.8) | 5 (3.1) |

| Diarrhea | 19 (5.0) | 13 (5.9) | 6 (3.7) |

| Skin rashes | 12 (3.1) | 9 (4.1) | 3 (1.9) |

| Fever (≥38°C) | 289 (75.5) | 174 (78.7) | 115 (71.0) |

| Crackles on chest auscultation | 45 (11.7) | 29 (13.1) | 16 (9.9) |

| White blood cell count (/μL) | 7100 [5700‐8800] | 6800 [5500‐8450] | 7400 [5900‐9425] |

| C‐reactive protein (mg/dL) | 2.20 [1.10‐4.58] | 2.00 [1.04‐4.13] | 2.52 [1.27‐5.40] |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Pneumonia | 275 (71.8) | 171 (77.4) | 104 (64.2) |

| Bronchitis/URI/sinusitis | 99 (25.8) | 46 (20.8) | 53 (32.7) |

| Others | 9 (2.3)a | 4 (1.8) | 5 (3.1) |

| Requirement of hospitalization | 88 (23.0) | 55 (24.9) | 33 (20.4) |

URI, upper respiratory infection.

Categorical data are presented as the number (proportion, %). Continuous data are presented as the median [interquartile range].

Only fever (five cases), chronic cough (two cases), tonsillitis (one case), and exudative erythema multiforme (one case) are included.

3.3. Clinical characteristics of pneumonia caused by M. pneumoniae with MRM

Among the 275 pneumonia cases determined to be caused by M. pneumoniae, 222 were pediatric and 53 were adult cases. Comparison of clinical characteristics of pediatric and adult pneumonia cases, with and without MRM, is shown in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively.

Table 2.

Factors associated with the determination of macrolide‐resistant mutations among pediatric cases with Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia

| Macrolide‐resistant mutations | P value | Adjusted P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |||

| N | 145 | 77 | ||

| Age (y) | 7.0 [5.0‐9.0] | 6.0 [3.0‐10.0] | 0.32 | |

| School age (6‐17 y old) | 100 (69.0) | 45 (58.4) | 0.14 | |

| Female | 73 (50.3) | 38 (49.4) | 1.00 | |

| Comorbidities | 11 (7.6) | 17 (22.1) | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| Asthma | 9 (6.2) | 13 (16.9) | 0.02 | |

| Immunosuppressive state | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.55 | |

| Preceding antimicrobial use | 101 (69.7) | 34 (44.2) | <0.001 | |

| Macrolides | 63 (43.4) | 10 (13.0) | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| Quinolones/Tetracyclines | 35 (24.1) | 11 (14.3) | 0.12 | |

| Onset to evaluation (d) | 7.0 [6.0‐8.0] | 7.0 [5.0‐8.0] | 0.15 | |

| Rhinorrhea | 16 (11.0) | 15 (19.5) | 0.10 | |

| Sputum or productive cough | 31 (21.4) | 19 (24.7) | 0.61 | |

| Severe cough | 34 (23.4) | 22 (28.6) | 0.42 | |

| Hypoxia | 4 (2.8) | 3 (3.9) | 0.70 | |

| Diarrhea | 6 (4.1) | 3 (3.9) | 1.00 | |

| Skin rashes | 6 (4.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.10 | |

| Fever (≥38°C) | 122 (84.1) | 62 (80.5) | 0.58 | |

| Crackles on chest auscultation | 24 (16.6) | 13 (16.9) | 1.00 | |

| White blood cell count (/μL) | 6800 [5550‐8450] | 7650 [6225‐10 000] | 0.008 | 0.05 |

| C‐reactive protein (mg/dL) | 1.80 [1.08‐3.63] | 2.23 [1.44‐4.00] | 0.22 | |

| Requirement of hospitalization | 44 (30.3) | 23 (29.9) | 1.00 | |

Categorical data are presented as the number (proportion, %). Continuous data are presented as the median [interquartile range].

Table 3.

Factors associated with the determination of macrolide‐resistant mutations among adult cases with Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia

| Macrolide‐resistant mutations | P value | Adjusted P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |||

| N | 26 | 27 | ||

| Age (y) | 27.5 [21.0‐33.8] | 31.0 [25.0‐37.5] | 0.17 | |

| Female | 12 (46.2) | 14 (51.9) | 0.79 | |

| Comorbidities | 3 (11.5) | 4 (14.8) | 1.00 | |

| Asthma | 2 (7.7) | 1 (3.7) | 0.61 | |

| Immunosuppressive state | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ‐ | |

| Preceding antimicrobial use | 18 (69.2) | 13 (48.1) | 0.17 | |

| Macrolides | 14 (53.8) | 3 (11.1) | 0.001 | 0.009 |

| Quinolones/Tetracyclines | 5 (19.2) | 2 (7.4) | 0.25 | |

| Onset to evaluation (d) | 8.0 [6.0‐9.0] | 5.0 [4.0‐6.0] | 0.002 | 0.06 |

| Rhinorrhea | 1 (3.8) | 6 (22.2) | 0.10 | |

| Sputum or productive cough | 18 (69.2) | 14 (51.9) | 0.26 | |

| Severe cough | 5 (19.2) | 3 (11.1) | 0.47 | |

| Hypoxia | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.4) | 0.49 | |

| Diarrhea | 3 (11.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.11 | |

| Skin rashes | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ‐ | |

| Fever (≥38°C) | 20 (76.9) | 21 (77.8) | 1.00 | |

| Crackles on chest auscultation | 3 (11.5) | 1 (3.7) | 0.35 | |

| White blood cell count (/μL) | 6850 [5750‐7975] | 6700 [5300‐8600] | 0.76 | |

| C‐reactive protein (mg/dL) | 6.51 [4.67‐12.17] | 9.00 [5.09‐11.21] | 0.93 | |

| Requirement of hospitalization | 10 (38.5) | 6 (22.2) | 0.24 | |

Categorical data are presented as the number (proportion, %). Continuous data are presented as the median [interquartile range].

In the 222 pediatric cases, MRM was found in 145 (65.3%) cases. As shown in Table 2, neither the median age nor gender distribution significantly differed between the two groups. Fewer comorbidities were identified among the cases with MRM (7.6% vs 22.1%, P = 0.003), whereas these cases showed a higher frequency of history of antimicrobial use, especially macrolide use (43.4% vs 13.0%, P < 0.001). No significant difference was obtained with respect to specific clinical signs and symptoms between the groups. In addition, the rate of the requirement of hospitalization was essentially identical. Multivariate logistic regression model showed that macrolide use before evaluation (odds ratio [OR] 3.86, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.72‐8.66) and the presence of comorbidities (OR 0.23, 95% CI: 0.09‐0.60) were significant independent variables for the determination of MRM in pediatric M. pneumoniae pneumonia cases.

The characteristics of 53 adult M. pneumoniae pneumonia cases are presented in Table 3, including 26 cases with MRM (49.1%). There was no significant difference between the cases with and without MRM in terms of age, gender distribution, presence of comorbidities, and any clinical signs and symptoms. The significant variables in univariate analyses were the use of macrolides before evaluation (53.8% vs 11.1%, P = 0.001) and the median time from symptom onset to evaluation (8.0 days vs 5.0 days, P = 0.002). Multivariate logistic regression model revealed that in adults, only preceding macrolide use was significantly associated with M. pneumoniae pneumonia cases with MRM (OR 7.43, 95% CI: 1.67‐33.1).

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated a high variation in MRM determination rate in M. pneumoniae within a single year. In parallel with the increasing number of M. pneumoniae infections determined between August and November 2016, the proportion of M. pneumoniae with MRM substantially decreased. In addition, macrolide use preceding evaluation was the only characteristic finding among the cases of M. pneumoniae pneumonia with MRM, observed both in children and in adults.

Clinical characteristics of macrolide‐resistant M. pneumoniae have been evaluated in previous studies. Cao et al21 described that the presence of macrolide resistance in M. pneumoniae did not alter the clinical presentation, including age, gender distribution, fever grade, cough, sputum, shortness of breath, and chest pain. Furthermore, WBC count, CRP values, and radiological findings were reported not to be influenced by macrolide resistance.22 Consistent with previous studies, our results indicated that clinical signs and symptoms were almost identical between pneumonia cases with and without MRM,21, 22 except for the macrolide prescription rate before evaluation.23 The higher macrolide prescription rate before evaluation, observed in MRM pneumonia cases, could be explained by the poor clinical response to the initial treatment, which may contribute to increased hospital visits.

Collecting the updated data of MRM determination rates among cases of M. pneumoniae infections may help to predict macrolide resistance and select effective treatment strategy accordingly. In Japan, the Infectious Disease Control Law mandates that the number of M. pneumoniae pneumonia cases diagnosed at designated sentinel sites be reported weekly, although these data do not include the prevalence trends of macrolide resistance. The rate of macrolide resistance was shown to vary from 50% to 93% across the seven districts of Japan,24 as well as among areas in the same prefecture ranging from 0 to 100% (Hokkaido).23 In this study, we employed the GENECUBE system and GENECUBE Mycoplasma detection kit for point‐of‐care molecular examinations, which can determine the presence of M. pneumoniae and MRM within only 1 hour. The reliability of mutation analysis with the GENECUBE system and GENECUBE Mycoplasma detection kit has previously been demonstrated, showing results identical with those obtained with a conventional sequence method (absence of mutations 82/173, A2063G 90/173, A2064G 1/173). Our results revealed that the rate of M. pneumoniae with MRM varied remarkably from season to season within the same year, which was possibly because of the change in endemic strains.25 Therefore, determining the exact trend of prevalence of M. pneumoniae with MRM requires continuous monitoring, conducted locally throughout the year, which could be helpful for the antimicrobial stewardship in primary care settings.

Macrolides and tetracyclines have an excellent therapeutic effect against M. pneumoniae, 26 and defervescence is usually achieved within 48‐72 hours in successful M. pneumoniae pneumonia cases.27 However, tetracyclines are contraindicated in children less than 8 years of age, who are at a high risk of M. pneumoniae infections. Tosufloxacin is effective against both macrolide‐susceptible and macrolide‐resistant strains, although its weak bactericidal effect limits its therapeutic efficacy.27 Taken together, especially in pediatric patients, first‐line treatment for macrolide‐susceptible M. pneumoniae pneumonia should be macrolides, whereas tetracycline or tosufloxacin should be preserved for macrolide‐resistant M. pneumoniae pneumonia, and tetracycline is preferred choice for cases older than 8 years of age.

Excessive use of macrolides and quinolones for respiratory infections has been a major concern in Japan,28 because of their possible association to high macrolide resistance rates among Streptococcus pneumoniae 29 and M. pneumoniae,7 and increased quinolone resistance among Enterobacteriaceae.30 Besides the reduction in antibiotic use, we consider that rapid diagnoses and early initiation of effective treatment may prevent the transmission of M. pneumoniae and consequently reduce the spread of macrolide‐resistant M. pneumoniae. Combination of clinical judgment and point‐of‐care molecular examination may assist in the appropriate prescription of antimicrobials, because of their high diagnostic performance for M. pneumoniae infections and determination of MRM. Further studies are required to investigate the optimal time for molecular examinations and favorable treatment strategy for M. pneumoniae pneumonia with MRM.

The present study has certain limitations. First, because of the nature of our institution and limitations of the retrospective study, the results could be biased and may not be comparable to those obtained in other hospitals. Second, our patients are likely to be cases with poor clinical response cases or those with unstable conditions. Cases without MRM or comorbidities could have been successfully treated at primary clinics or hospitals; thus, selection bias may have facilitated the prevalence of comorbidities, including asthma and the rate of MRM determination. Third, we did not evaluate the mutations at site 2617 of the 23S rRNA region, as it could not be determined by the GENECUBE system and GENECUBE Mycoplasma detection kit. However, a previous study showed that mutations at site 2617 were rarely determined in Japan (0.3%),15 and these mutations are also known to confer only weak resistance to macrolides.31 Therefore, any undetermined mutations at site 2617 were considered to have a negligible impact on the general conclusions of our study.

5. CONCLUSION

The results of this study point out the difficulty in the diagnosis of M. pneumoniae pneumonia cases with MRM based on clinical signs and symptoms alone, because the only distinctive feature of M. pneumoniae with MRM was found to be a preceding use of macrolides. Therefore, local and continuous monitoring of the rate of MRM among M. pneumoniae clinical isolates is warranted to improve infection management.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have stated explicitly that there are no conflicts of interest in connection with this article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

H.S planed the study, constructed the GENECUBE® test system in our hospital, collected data, constructed the database, and analyzed data. D.H collected data, constructed the database, and analyzed data. T.I and H.I collected patient data. S.N constructed the GENECUBE® test system in our hospital and performed the M. pneumoniae PCR test. The chest x‐ray was checked by a board‐certified radiologist (S.M), board respiratory physician (K.K), and H.I. Tsukuba Medical Center Hospital received fees for research expenses for the quality evaluation of the GENECUBE and GENECUBE Mycoplasma systems.

Akashi Y, Hayashi D, Suzuki H, et al. Clinical features and seasonal variations in the prevalence of macrolide‐resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae . J Gen Fam Med. 2018;19:191–197. 10.1002/jgf2.201

REFERENCES

- 1. Miyashita N, Fukano H, Mouri K, et al. Community‐acquired pneumonia in Japan: a prospective ambulatory and hospitalized patient study. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bamba M, Jozaki K, Sugaya N, et al. Prospective surveillance for atypical pathogens in children with community‐acquired pneumonia in Japan. J Infect Chemother. 2006;12:36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Saraya T. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection: basics. J Gen Fam Med. 2017;18:118–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bébéar C, Pereyre S, Peuchant O. Mycoplasma pneumoniae: susceptibility and resistance to antibiotics. Future Microbiol. 2011;6:423–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hallander HO, Gnarpe J, Gnarpe H, Olin P. Bordetella pertussis, Bordetella parapertussis, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae and persistent cough in children. Scand J Infect Dis. 1999;31:281–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Defilippi A, Silvestri M, Tacchella A, et al. Epidemiology and clinical features of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children. Respir Med. 2008;102:1762–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yamazaki T, Kenri T. Epidemiology of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections in Japan and therapeutic strategies for macrolide‐resistant M. pneumoniae . Front Microbiol 2016;7:693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kawai Y, Miyashita N, Kubo M, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of macrolides, minocycline, and tosufloxacin against macrolide‐resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in pediatric patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:2252–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Miyashita N, Matsushima T, Oka M, Japanese Respiratory S . The JRS guidelines for the management of community‐acquired pneumonia in adults: an update and new recommendations. Intern Med. 2006;45:419–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bradley JS, Byington CL, Shah SS, et al. The Management of community‐acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:e25–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pereyre S, Goret J, Bébéar C. Mycoplasma pneumoniae: current knowledge on macrolide resistance and treatment. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Atkinson TP, Balish MF, Waites KB. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, pathogenesis and laboratory detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:956–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Sheng Y, Zhang L, Shen Z, Chen Z. More complications occur in macrolide‐resistant than in macrolide‐sensitive Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:1034–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cheong KN, Chiu SS, Chan BW, To KK, Chan EL, Ho PL. Severe macrolide‐resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia associated with macrolide failure. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2016;49:127–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tanaka T, Oishi T, Miyata T, et al. Macrolide‐Resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae Infection, Japan, 2008–2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:1703–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jain S, Williams DJ, Arnold SR, et al. Community‐acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. children. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:835–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al. Community‐acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. Adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:415–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Suzuki H. Current status of automated molecular diagnostic instruments in the area of clinical infectious diseases and their clinical implementation. Rinsho Byori. 2017;65:624–34. (in Japanese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ibaraki Prefecture Infectious Disease Surveillance Center [internet]. Ibaraki: Infectious disease weekly report. [updated 17 May 2018; cited 20 May 2018]. Available from: http://www.pref.ibaraki.jp/hokenfukushi/eiken/idwr/index.html.

- 21. Cao B, Zhao CJ, Yin YD, et al. High prevalence of macrolide resistance in Mycoplasma pneumoniae isolates from adult and adolescent patients with respiratory tract infection in China. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:189–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cardinale F, Chironna M, Chinellato I, Principi N, Esposito S. Clinical relevance of Mycoplasma pneumoniae macrolide resistance in children. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:723–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ishiguro N, Koseki N, Kaiho M, et al. Regional differences in prevalence of macrolide resistance among pediatric Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections in Hokkaido, Japan. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2016;69:186–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kawai Y, Miyashita N, Kubo M, et al. Nationwide surveillance of macrolide‐resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in pediatric patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:4046–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Waites KB, Xiao L, Liu Y, Balish MF, Atkinson TP. Mycoplasma pneumoniae from the respiratory tract and beyond. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30:747–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Morozumi M, Okada T, Tajima T, Ubukata K, Iwata S. Killing kinetics of minocycline, doxycycline and tosufloxacin against macrolide‐resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae . Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017;50:255–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ouchi K, Okada K, Kurosaki T. Guidelines for the management of respiratory infectious disease in children in Japan 2017. Tokyo, Japan: Kyowa Kikaku; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Higashi T, Fukuhara S. Antibiotic prescriptions for upper respiratory tract infection in Japan. Intern Med. 2009;48:1369–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Isozumi R, Ito Y, Ishida T, et al. Genotypes and related factors reflecting macrolide resistance in pneumococcal pneumonia infections in Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1440–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aldred KJ, Kerns RJ, Osheroff N. Mechanism of quinolone action and resistance. Biochemistry. 2014;53:1565–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Matsuoka M, Narita M, Okazaki N, et al. Characterization and molecular analysis of macrolide‐resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae clinical isolates obtained in Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4624–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]