Abstract

Background

Aerosolized antibiotics have been proposed as a novel and promising treatment option for the treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). However, the optimum aerosolized antibiotics for VAP remain uncertain.

Methods

We included studies from two systematic reviews and searched PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane databases for other studies. Eligible studies included randomized controlled trials and observational studies. Extracted data were analyzed by pairwise and network meta-analysis.

Results

Eight observational and eight randomized studies were identified for this analysis. By pairwise meta-analysis using intravenous antibiotics as the reference, patients treated with aerosolized antibiotics were associated with significantly higher rates of clinical recovery (risk ratio (RR) 1.21, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.09–1.34; P = 0.001) and microbiological eradication (RR 1.42, 95% CI 1.22–1.650; P < 0.0001). There were no significant differences in the risks of mortality (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.74–1.04; P = 0.127) or nephrotoxicity (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.72–1.39; P = 0.995). Using network meta-analysis, clinical recovery benefits were seen only with aerosolized tobramycin and colistin (especially tobramycin), and microbiological eradication benefits were seen only with colistin. Aerosolized tobramycin was also associated with significantly lower mortality when compared with aerosolized amikacin and colistin and intravenous antibiotics. The assessment of rank probabilities indicated aerosolized tobramycin presented the greatest likelihood of having benefits for clinical recovery and mortality, and aerosolized colistin presented the best benefits for microbiological eradication.

Conclusions

Aerosolized antibiotics appear to be a useful treatment for VAP with respect to clinical recovery and microbiological eradication, and do not increase mortality or nephrotoxicity risks. Our network meta-analysis in patients with VAP suggests that clinical recovery benefits are associated with aerosolized tobramycin and colistin (especially tobramycin), microbiological eradication with aerosolized colistin, and survival with aerosolized tobramycin, mostly based on observational studies. Due to the low levels of evidence, definitive recommendations cannot be made before additional, large randomized studies are carried out.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13054-018-2106-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Aerosolized antibiotics, Ventilator-associated pneumonia, Multidrug-resistant pathogens, Meta-analysis, Network meta-analysis

Background

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), one form of hospital-associated pneumonia (HAP), is defined as pneumonia developing in a mechanically ventilated patient ≥ 48 h after tracheal intubation. When it occurs, VAP has been recognized as the leading cause of mortality among patients with nosocomial infections, and VAP patients are hospitalized on average for an additional 4–13 days with excess hospital costs [1]. Effective antimicrobial therapy requires adequate drug concentrations at the infection site. However, intravenous therapy has altered the pharmacokinetics and poor lung tissue penetration of many antimicrobial agents [2]. Thus, aerosolized antibiotic therapy directly targets airway and lung parenchyma resulting in high local concentrations and potentially higher clinical responses. Moreover, aerosolized antibiotic therapy, which directly treats lung infections, can be used to decrease systemic antibiotic doses to minimize antibiotic-associated toxicities [3].

Two previous meta-analyses reported that aerosolized antibiotic therapy might be beneficial in the treatment of VAP [4, 5]. However, all of these studies were traditional pairwise meta-analyses comparing aerosolized antibiotics with intravenous antibiotics, and none made comparisons between the aerosolized antibiotics. A network meta-analysis (NMA), also known as mixed treatment comparison or multiple treatment comparison, is a method for concurrent comparison of multiple treatments in a single meta-analysis [6].

In the present study, our objective was to update the evidence to systematically evaluate the effect of aerosolized antibiotics in VAP patients on clinical recovery, microbiological eradication, mortality, and nephrotoxicity; we also used an NMA approach which enabled us to assess three aerosolized antibiotics by indirect comparison to determine their efficacy.

Methods

Search strategy

We included the studies from two systematic reviews [4, 5]. In addition, we also searched the PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane databases from inception to September 2017 to identify potentially relevant studies. Search terms included several parameters: 1) ventilator associated pneumonia OR VAP OR respiratory infection OR respiratory tract OR hospital acquired pneumonia OR nosocomial pneumonia; 2) aerolised OR aerosolized OR inhaled OR nebulised OR nebulized. We also evaluated the reference lists of the relevant clinical trials to identify additional studies.

Studies were included if they met several criteria: 1) patients in a study population that were mechanically ventilated and diagnosed with VAP; 2) intervention which included the use of inhaled antibiotics for treatment of VAP compared with intravenous antibiotics; and 3) at least one of the following outcomes was reported: clinical recovery, microbiological eradication, mortality, and nephrotoxicity.

Study quality assessment

The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for observational studies was used to assess the quality of the included studies. The NOS statement was judged on three broad perspectives (selection, comparability, and outcome) consisting of eight items. The qualities of randomized clinical trials were assessed using the risk of bias tool recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration. We assigned a value of high, unclear, or low to several parameters: 1) random sequence generation; 2) allocation concealment; 3) blinding of participants and personnel; 4) blinding of outcome assessment; 5) incomplete outcome data; 6) selective reporting; and/or 7) other bias.

Statistical analysis

We used the STATA program (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas) for pairwise meta-analysis. The differences between the two groups were calculated as the relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for dichotomous outcomes. Heterogeneity was assessed by the Cochran Q statistic and the I2 statistic. A P value ≤ 0.10 together with an I2 value ≥ 50% indicates significant heterogeneity. I2 values ≤ 50% represented acceptable between-study heterogeneity, and the fixed-effects model was selected. Otherwise, the random-effects model was selected [7, 8]. Publication bias was determined using the funnel plot and assessed by Egger’s test. We performed the NMA within a Bayesian framework using JAGS (version 4.2.0), R software (version 3.4.4), and the rjags and gemtc packages. The probability that each aerosolized antibiotic therapy was the best among the given treatments was determined by evaluating the rank probabilities. A higher probability of achieving rank 1 indicated a higher probability of being the best. We used these results for our interpretation.

Results

Selection and characteristics of the studies

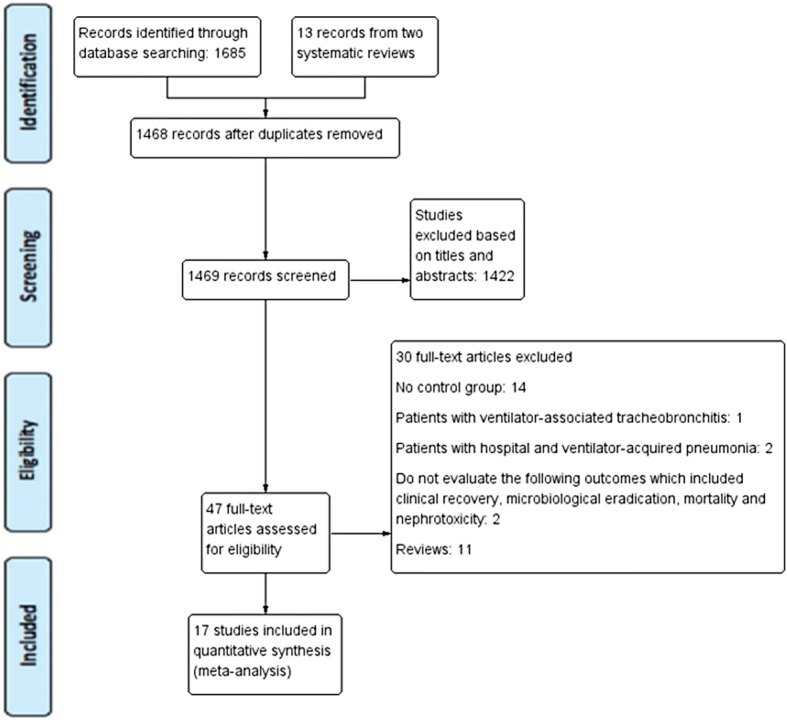

We identified 13 studies through the reanalysis of the two systematic reviews, and four studies through the PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane search. These trials were published between 2000 and 2017. Accordingly, the current meta-analysis included 17 studies [9–25]. The detailed steps of the study selection process are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram

Table 1 shows the major characteristics of the included trials. There were nine observational studies and eight randomized clinical trials. Fifteen studies presented the outcome of clinical recovery [9–21, 23, 24], and 10 presented the outcome of microbiological eradication [9, 10, 12–15, 19–22]. Mortality was reported in 14 trials [10, 11, 13–17, 19–25], and nephrotoxicity was reported in six trials [10, 13, 15, 18, 19, 21]. For the network meta-analysis, we excluded studies that used several inhaled antibiotics [9, 22, 25]. Three studies investigated the effect of inhaled amikacin [20, 21, 24], three studies concerned inhaled tobramycin [16–18], and eight studies concerned colistin [10–15, 19, 23].

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study, year | Country | Inclusion population | No. of patients | Disease severity | Respiratory comorbidities | Administration strategy | Antibiotic given (dose) | Device for drug delivery | Main outcomes | Quality assessment/Cochrane risk of biasa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (AS/IV) | AS | IV | AS | IV | AS | IV | |||||||

| Observational studies | |||||||||||||

| Ghannam, 2009 [9] | USA | Gram-negative bacteria VAP | 16/16 | CPIS score: 7 ± 2.9 | CPIS score: 6 ± 1.8 | COPD: 3 | COPD: 6 | Substitution strategy | Colistin (100 mg every 8 h), tobramycin (300 mg b.i.d), gentamicin (100 mg t.i.d), and amikacin (100 mg t.i.d. or 300 mg b.i.d) | Amikacin (100 mg per 3 ml), gentamicin (40 mg per ml), and colistin (75 mg per 4 ml) | Jet nebulizer | Clinical recovery, microbiological eradication | 9 |

| Kofteridis, 2010 [10] | Greece | MDR VAP due to Gram-negative bacteria | 43/43 | APACHE II score: 16.95 ± 6.59 | APACHE II score: 17.74 ± 7.61 | COPD: 12 | COPD: 7 | Adjunctive strategy | Colistin (2 million IU b.i.d) | Colistin (3 million IU t.i.d) | Not described | Clinical recovery, microbiological eradication, all-cause mortality, nephrotoxicity | 9 |

| Korbila, 2010 [11] | Greece | Microbiologically documented VAP | 78/43 | APACHE II score: 17.4 ± 6 | APACHE II score: 19.2 ± 7 | Pulmonary: 17 | Pulmonary: 9 | Adjunctive strategy | Colistin (1 million IU) | Colistin (6.4 ± 2.3 million) | Ultrasonic nebulizer | Clinical recovery, mortality | 9 |

| Pérez-Pedrero, 2011 [12] | Spain | VAP due to multi-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii | 36/18 | APACHE II score: 11.2 ± 4.3 | APACHE II score: 12.8 ± 5.7 | Not described | Not described | Adjunctive strategy | Colistin (1 million every 8 h, 0.5 million every 8 h, or 1 million b.i.d) | Colistin (1 million every 8 h, 0.5 million every 8 h, or 1 million b.i.d) | Not described | Clinical recovery, microbiological eradication | 8 |

| Kalin, 2012 [13] | Turkey | VAP due to multi-resistant A. baumannii | 15/29 | APACHE II score: 22 | APACHE II score: 22 | COPD: 4 | COPD: 6 | Adjunctive strategy | Colistin (150 mg b.i.d) | Colistin (2.5 mg/kg b.i.d or every 6 h) | Not described | Clinical recovery, microbiological eradication, all-cause mortality, nephrotoxicity | 9 |

| Arnold, 2012 [25] | USA | Pseudomonas aeruginosa and A. baumannii VAP | 19/74 | APACHE II score: 17.5 ± 5.3 | APACHE II score: 21.4 ± 5.7 | Pulmonary: 22 | Pulmonary: 6 | Adjunctive strategy | Colistin (150 mg b.i.d) or tobramycin (300 mg b.i.d) | Standard IV antibiotics | Not described | All-cause mortality | 8 |

| Doshi, 2013 [14] | USA | MDR VAP due to Gram-negative bacteria | 44/51 | APACHE II score: 22.4 ± 7.1 | APACHE II score: 24 ± 6.9 | Not described | Not described | Adjunctive strategy | Colistin (75–150 mg b.i.d) | Colistin (2.5 mg/kg b.i.d) | Jet or vibrating mesh nebulizer | Clinical recovery, microbiological eradication, hospital mortality | 7 |

| Tumbarello, 2013 [15] | Italy | Patients with VAP caused by Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, or Klebsiella | 104/104 | CPIS: 7.8 ± 1.2 | CPIS: 7.9 ± 1.3 | COPD: 21 | COPD: 28 | Adjunctive strategy | Colistin (1 million IU t.i.d) | Colistin (0.1 IU/kg every 8 to 12 h) | Jet or ultrasonic nebulizer | Clinical recovery, microbiological eradication, all-cause mortality, nephrotoxicity | 9 |

| Migiyama, 2017 [16] | Japan | ARDS patients with VAP caused by P. aeruginosa | 22/22 | APACHE II score: 26.2 ± 6.6 | APACHE II score: 24.5 ± 7.0 | Pulmonary: 6 | Pulmonary: 5 | Adjunctive strategy | Tobramycin (240 mg) | Tobramycin | Ultrasonic nebulizer | Clinical recovery, ICU mortality | 9 |

| Le Conte, 2000 [17] | France | Intubated and mechanically ventilated patients with nosocomial pneumonia | 21/17 | N/A | N/A | Not described | Not described | Adjunctive strategy | Tobramycin (6 mg/kg/day) | Betalactam and tobramycin | Pneumatic nebulizer | Clinical recovery, mortality | High |

| Hallal, 2007 [18] | USA | VAP caused by Pseudomonas or Acinetobacter | 5/5 | APACHE II score: 17 ± 1.26 | APACHE II score: 15 ± 3.3 | Not described | Not described | Substitution strategy | Tobramycin (300 mg b.i.d) | Betalactam and tobramycin | Jet nebulizer | Clinical recovery, nephrotoxicity | High |

| Rattanaumpawan, 2010 [19] | Thailand | Gram-negative bacteria VAP | 51/49 | APACHE II score: 19.1 ± 5.8 | APACHE II score: 18.5 ± 4.7 | Not described | Not described | Adjunctive strategy | Colistin (75 mg b.i.d) | Standard intravenous antibiotics | Jet or ultrasonic nebulizer | Clinical recovery, microbiological eradication, 28-day mortality, nephrotoxicity | High |

| Lu, 2011 [20] | France | VAP caused by Pseudomonas | 20/20 | CPIS score: 8 (7–8) | CPIS score: 9 (8–9) | COPD: 3 | COPD: 4 | Substitution strategy | Amikacin (25 mg/kg/day) | Amikacin (15 mg/kg/day) and ceftazidime (90 mg/kg/3 h) | Vibrating nebulizer | Clinical recovery, microbiological eradication, 28-day mortality | High |

| Niederman, 2012 [21] | France/Spain/USA | Mechanically ventilated patients with Gram-negative pneumonia | 46/22 | CPIS score: 6.8 (1.2) | CPIS score: 7 (1.2) | Not described | Not described | Adjunctive strategy | Amikacin (400 mg b.i.d or 400 mg/day) | Standard intravenous antibiotics | Vibrating mesh nebulizer | Clinical recovery, microbiological eradication, all-cause mortality, nephrotoxicity | Low |

| Palmer, 2014 [22] | USA | Patients with high risk for MDR organisms in the respiratory tract | 24/18 | APACHE II score: 20.96 ± 5.8 | APACHE II score: 14.4 ± 5.5 | COPD: 3 | COPD: 2 | Adjunctive strategy | Vancomycin (120 mg t.i.d), gentamicin sulfate (80 mg t.i.d), or amikacin (400 mg t.i.d) | Standard IV antibiotics | Jet nebulizer | Microbiological eradication, all-cause mortality | High |

| Abdellatif, 2016 [23] | Tunisia | Gram-negative bacteria VAP | 73/76 | SOFA score: 7.03 ± 3.8 | SOFA score: 6.5 ± 4.1 | Pulmonary: 32 | Pulmonary: 29 | Adjunctive strategy | Colistin (4 million IU t.i.d) | Imipenem (1 g t.i.d) | Ultrasonic vibrating plate nebulizer | Clinical recovery, 28-day mortality | Low |

| Kollef, 2017 [24] | USA | Gram-negative bacteria VAP | 71/72 | APACHE II score: 18.5 ± 5.6 | APACHE II score: 18.4 ± 5.9 | Not described | Not described | Adjunctive strategy | Amikacin (300 mg) and fosfomycin (120 mg) | Meropenem or imipenem | Vibrating plate electronic nebulizer | Clinical recovery, 28-day mortality | Low |

APACHE Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation, AS aerosolized, b.i.d. twice daily, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CPIS Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score, ICU intensive care unit, IU international units, IV intravenous, MDR multidrug resistant, N/A indicates not available, SOFA Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, , t.i.d. three times daily, VAP ventilator-associated pneumonia

aQuality assessment is shown for observational studies, and Cochrane risk of bias is shown for randomized controlled trials

Pairwise meta-analysis

The overall pooled RR of clinical recovery, microbiological eradication, mortality, and nephrotoxicity are shown in Additional file 1: Figure S1. Additional file 1: Figure S1A shows the estimates of clinical recovery rates from fifteen studies. Aerosolized antibiotics were associated with significantly higher rates of clinical recovery (RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.09–1.34; P = 0.001). There was no statistical heterogeneity in the fixed effect model (I2 = 36.2%).

Ten trials reported microbiological eradication as an outcome, and the pooled results indicated that aerosolized antibiotics also had a beneficial effect (RR 1.42, 95% CI 1.22–1.65; P < 0.0001), despite significant heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 68.5%) (Additional file 1: Figure S1B).

Mortality at the longest follow-up was available in 14 studies; aerosolized antibiotics had similar effects to control groups (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.74–1.04; P = 0.127) with no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 23.6%) (Additional file 1: Figure S1C).

Six studies presented data regarding complications on nephrotoxicity; aerosolized antibiotics were not associated with an increased risk of nephrotoxicity (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.72–1.39; P = 0.995) with no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 19.4%) (Additional file 1: Figure S1D).

Publication bias

We detected no evidence of publication bias after assessing funnel plots (Additional file 2: Figure S2) and Egger’s test (clinical recovery P = 0.553, microbiological eradication P = 0.156, mortality P = 0.869 and nephrotoxicity P = 0.223). The data suggested that there was no evidence of publication bias for clinical recovery, microbiological eradication, mortality and/or nephrotoxicity.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses were carried out to determine the influence of each study on the pooled RR, and the statistical findings were not materially altered by the elimination of any study (Additional file 3: Figure S3).

Bayesian network meta-analysis

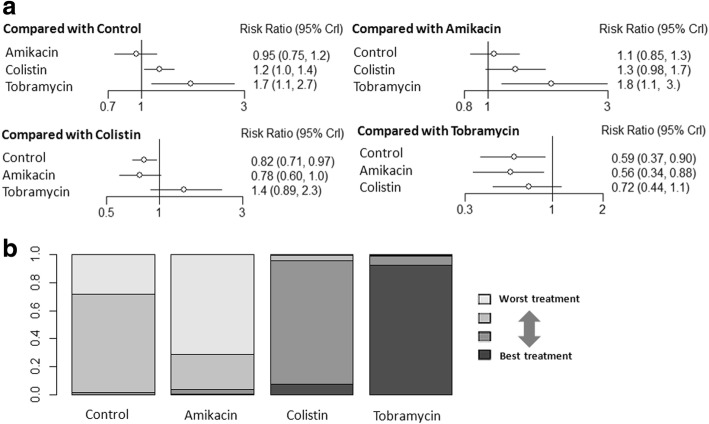

There were no trials comparing outcomes among the aerosolized antibiotics, and all trials had an intravenous antibiotics arm. Thus, we pooled direct comparisons to obtain indirect comparisons by comparing aerosolized tobramycin versus aerosolized colistin, aerosolized tobramycin versus aerosolized amikacin, and aerosolized colistin versus aerosolized amikacin. In individual comparisons for clinical recovery using intravenous antibiotics as the reference, aerosolized tobramycin and colistin were more likely to increase the rate of clinical recovery (NMA: RR 1.7, 95% CI 1.1–2.7; and RR 1.2, 95% CI 1.0–1.4, respectively; Fig. 2a). Aerosolized tobramycin was associated with a significantly higher rate of clinical recovery compared with aerosolized amikacin (NMA: RR 1.8, 95% CI 1.1–3.0; Fig. 2a). There were no significant differences among the other comparisons of the network meta-analysis for clinical recovery (Fig. 2). The assessment of rank probabilities indicated that tobramycin (92.3% probability) presented the greatest likelihood of improving efficacy among the evaluated aerosolized antibiotics for treating VAP, followed by colistin (SUCRA 7.4% probability) and then amikacin (0.2% probability) (Fig. 2b). We conducted subgroup analyses according to geography, type of inhaled drug delivery system, VAP with or without multidrug resistance (MDR), type of studies, and administration strategy (Table 2). Results of our subgroup analyses from rank probabilities suggested that tobramycin displayed the best benefit for clinical recovery, followed by colistin, and then amikacin.

Fig. 2.

a Network estimates among aerosolized antibiotics for clinical recovery. b Rank probabilities among aerosolized antibiotics for clinical recovery based on the network meta-analysis. The number of patients in each antibiotic arm: control, 476; amikacin, 135; colistin, 372; and tobramycin, 48. CI confidence interval

Table 2.

Results of subgroup analysis

| Outcome | Subgroup | Relative risk (95% confidence interval) and rank probabilities | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobramycin vs control; tobramycin (rank probability) | Colistin vs control; colistin (rank probability) | Amikacin vs control; amikacin (rank probability) | Tobramycin vs colistin | Tobramycin vs amikacin | Colistin vs amikacin | ||

| Clinical recovery | Geography | ||||||

| USA | 2.37 (1.7–5.62); tobramycin 97.3% | 1.3 (0.68–2.7); colistin 2.2% | 0.68 (0.27–1.7); amikacin 0.2% | 1.83 (1.2–4.67) | 3.4 (2.2–8.89) | 2 (0.65–6.3) | |

| Europe | 1.52 (0.52–6.6); tobramycin 65.4% | 1.2 (0.86–1.5); colistin 28.7% | 0.98 (0.67–1.5); amikacin 4.6% | 1.3 (0.42–5.7) | 1.6 (0.5–7.1) | 1.3 (0.72–1.9) | |

| Asia | 1.6 (0.74–3.3); tobramycin 82.3% | 0.95 (0.48–1.9); colistin 5.6% | – | 1.6 (0.60–4.5) | – | – | |

| Type of inhaled drug delivery system | |||||||

| Jet nebulizer | 2.1 (1.5–5.34); tobramycin 98.6% | 1.1 (0.71–1.8); colistin 1.2% | – | 2.53 (1.2–6.7) | – | – | |

| Ultrasonic nebulizer | 1.5 (0.85–3); tobramycin 78.8% | 1.2 (0.95–1.6); colistin 20.5% | – | 1.3 (0.67–2.6) | – | – | |

| Vibrating nebulizer | – | 1.3 (0.93–2); colistin 91.9% | 0.95 (0.72–1.2); amikacin 4.2% | – | – | 1.4 (0.91–2.3) | |

| VAP with or without MDR | |||||||

| VAP with MDR | – | 1.2 (0.70–1.7); colistin 66.4% | 0.97 (0.40–2.5); amikacin 24.8% | – | – | 1.2 (0.40–3.1) | |

| VAP without MDR | 1.7 (1.1–3.2); tobramycin 88.5% | 1.2 (0.83–1.7); colistin 9% | 0.68 (0.27–1.6); amikacin 2.1% | 1.5 (0.8–2.9) | 2.6 (0.94–7.8) | 1.8 (0.68–4.8) | |

| Type of studies | |||||||

| Randomized controlled trials | 2.2 (0.95–8); tobramycin 92.9% | 1.1 (0.71–1.8); colistin 5.6% | 0.94 (0.65–1.3); amikacin 0.8% | 2.5 (0.93–9.9) | 2.4 (0.96–8.7) | 1.2 (0.69–2.1) | |

| High risk of bias | 2.2 (0.91–7.7); tobramycin 87.5% | 0.94 (0.43–2); colistin 5.6% | 0.98 (0.47–2.1); amikacin 5.7% | 2.4 (0.74–10) | 2.3 (0.73–9.5) | 0.96 (0.33–2.8) | |

| Low risk of bias | – | 1.4 (0.73–2.8); colistin 82.1% | 0.92 (0.59–1.3); amikacin 7.7% | – | – | 1.5 (0.72–3.5) | |

| Observational studies | 1.6 (0.78–3.3); tobramycin 75.9% | 1.2 (0.88–1.6); colistin 22.9% | – | 1.3 (0.63–2.9) | – | – | |

| NOS = 9 | 1.6 (0.48–5.1); tobramycin 70.8% | 0.96 (0.51–1.81); colistin 23.7% | – | 1.3 (0.40–5.5) | – | – | |

| NOS < 9 | – | 1.2 (0.84–1.9); colistin 87.6% | – | – | – | – | |

| Administration strategy | |||||||

| Adjunctive strategy | 1.6 (0.94–2.70); tobramycin 81.4% | 1.2 (1.0–1.4); colistin 16.8% | 0.93 (0.64–1.3); amikacin 1.4% | 1.3 (0.76–2.3) | 1.7 (0.92–3.2) | 1.3 (0.87–2) | |

| Substitution strategy | 1.57 (0.46–5.34); tobramycin 98.9% | – | 0.96 (0.76–1.21); amikacin 0.7% | – | 1.64 (0.47–5.69) | – | |

| Mortality | Geography | ||||||

| USA | – | 1.4 (0.76–2.6); colistin 3.6% | 0.66 (0.30–1.4); amikacin 83.9% | – | – | 2.1 (0.79–5.8) | |

| Europe | 0.31 (0.039–1.6); tobramycin 85.7% | 1.2 (0.40–4.1); colistin 0.1% | 0.87 (0.57–1.3); amikacin 7.8% | 0.36 (0.044–5.0) | 0.25 (0.022–1.8) | 0.72 (0.20–2.3) | |

| Asia | 0.33 (0.074–1.4); tobramycin 86.9% | 0.92 (0.26–3.3); colistin 10.6% | – | 0.36 (0.051–2.4) | – | – | |

| Type of inhaled drug delivery system | |||||||

| Jet nebulizer | – | 0.88 (0.63–1.2); colistin 81.6% | – | – | – | – | |

| Ultrasonic nebulizer | 0.33 (0.11–0.87); tobramycin 97.2% | 0.92 (0.64–1.4); colistin 1.7% | – | 0.36 (0.11–1.0) | – | – | |

| Vibrating nebulizer | – | 1.3 (0.70–2.4); colistin 20% | 1.3 (0.68–2.6); amikacin 14.8% | – | – | 1.0 (0.40–2.4) | |

| VAP with or without MDR | |||||||

| VAP with MDR | – | 0.81 (0.55–1.2); colistin 70.9% | 1.3 (0.39–6.3); amikacin 22.3% | – | – | 0.61 (0.12–2.1) | |

| VAP without MDR | 0.34 (0.13–0.78); tobramycin 71.7% | 0.91 (0.54–1.5); colistin 7.4% | 0.7 (0.3–1.7); amikacin 26.7% | 0.37 (0.12–1) | 0.48 (0.13–1.6) | 1.3 (0.47–3.5) | |

| Type of studies | |||||||

| Randomized controlled trials | 0.31 (0.039–1.6); tobramycin 80.9% | 0.95 (0.45–2); colistin 6.6% | 0.83 (0.41–1.8); amikacin 11.3% | 0.32 (0.036–2) | 1.1 (0.38–3.1) | 0.37 (0.042–2.3) | |

| High risk of bias | 0.31 (0.039–1.8); tobramycin 73.5% | 0.92 (0.32–2.7); colistin 8% | 1.1 (0.11–10); amikacin 16.3% | 0.33 (0.033–2.7) | 0.28 (0.013–5.2) | 0.86 (0.073–10) | |

| Low risk of bias | – | 0.81 (0.43–1.6); colistin 31.4% | 1 (0.25–3.9); amikacin 50.3% | – | – | 1.2 (0.27–5.5) | |

| Observational studies | 0.34 (0.11–0.9); tobramycin 95.7% | 0.83 (0.58–1.1); colistin 3.9% | – | 0.41 (0.12–1.2) | – | – | |

| NOS = 9 | 0.34 (0.094–0.96); tobramycin 95.1% | 0.86 (0.54–1.3); colistin 4.2% | – | 0.39 (0.1–1.2) | – | – | |

| NOS < 9 | – | 0.67 (0.35–1.3); colistin 90.2% | – | – | – | – | |

| Administration strategy | |||||||

| Adjunctive strategy | 0.34 (0.14–0.72); tobramycin 95% | 0.85 (0.66–1.1); colistin 0.83% | 0.8 (0.44–1.5); amikacin 4.1% | 0.4 (0.16–0.88) | 0.42 (0.14–1.1) | 1.1 (0.54–2) | |

| Substitution strategy | – | – | 0.99 (0.088–9.5); amikacin 48.7% | – | – | – | |

MDR multidrug resistance, NOS Newcastle-Ottawa scale, VAP ventilator-associated pneumonia

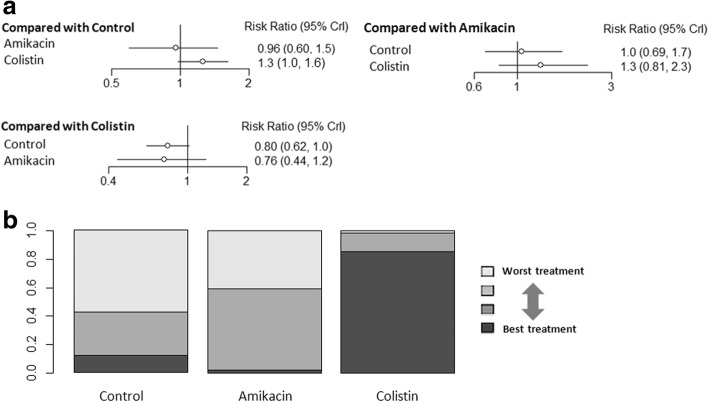

None of the studies used aerosolized tobramycin to evaluate the effects on microbiological eradication. Aerosolized colistin had a higher rate of microbiological eradication when compared with intravenous antibiotics (NMA: RR 1.3, 95% CI 1.0–1.6; Fig. 3a). There were no significant differences among the other comparisons of the network meta-analysis for microbiological eradication (Fig. 3a). Ranking analysis revealed that colistin presented the highest rate of microbiological eradication (86.2% probability) (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

a Network estimates among aerosolized antibiotics for microbiological eradication. b Rank probabilities among aerosolized antibiotics for microbiological eradication based on the network meta-analysis. The number of patients in each antibiotic arm: control, 271; amikacin, 74; and colistin, 241. CI confidence interval

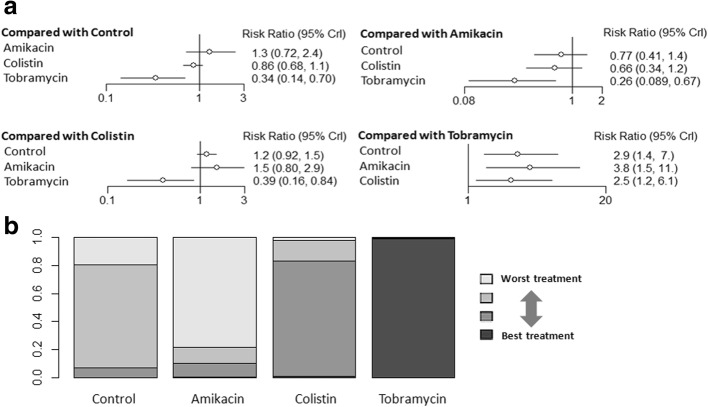

Taking intravenous antibiotics as the reference revealed no statistically significant differences in mortality in aerosolized amikacin and colistin, but aerosolized tobramycin showed lower mortality risk (NMA: RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.14–0.70) (Fig. 4a). Aerosolized tobramycin was also associated with significantly lower mortality compared with aerosolized amikacin (NMA: RR 0.26, 95% CI 0.089–0.67) and aerosolized colistin (NMA: RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.16–0.84) (Fig. 4a). Ranking analysis revealed that the hierarchy for efficacy in avoiding death (highest to lowest rank) was tobramycin (98.5% probability), followed by colistin (0.99% probability) and then amikacin (0.37% probability) (Fig. 4b). Table 2 shows the rank probabilities of subgroup analyses that provided the hierarchies for the mortality of the aerosolized antibiotics. Ranking analysis revealed that tobramycin was the best treatment in terms of reducing hospital mortality.

Fig. 4.

a Network estimates among aerosolized antibiotics for mortality. b Rank probabilities among aerosolized antibiotics for mortality based on the network meta-analysis. The number of patients in each antibiotic arm: control, 464; amikacin, 138; colistin, 362; and tobramycin, 43. CI confidence interval

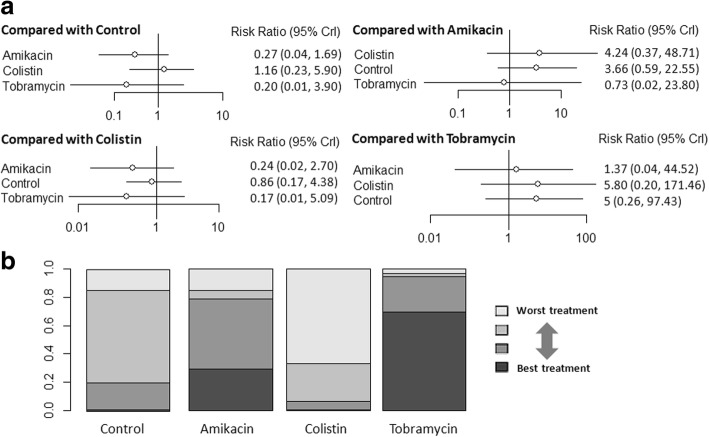

The forest plot for the risk of nephrotoxicity is shown in Fig. 5a. There were no significant differences among any comparisons of the network meta-analysis (Fig. 5a). Ranking analysis revealed that the hierarchy for safety in avoiding renal toxicity (highest to lowest rank) was tobramycin (69.4% probability), followed by amikacin (29.4% probability) and then colistin (0.5% probability) (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

a Network estimates among aerosolized antibiotics for nephrotoxicity. b Rank probabilities among aerosolized antibiotics for nephrotoxicity based on the network meta-analysis. The number of patients in each antibiotic arm: control, 231; amikacin, 45; colistin, 5; and tobramycin, 230. CI confidence interval

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated that aerosolized antibiotics affected the clinical prognosis in VAP treatment. Whether aerosolized antibiotics are beneficial or harmful for critically ill patients has long been a matter of debate. In this meta-analysis, we found that aerosolized antibiotics could improve clinical recovery and microbiological eradication. In addition, there were no differences in terms of outcomes such as mortality or nephrotoxicity. The present network meta-analysis and ranking analysis suggest that the probability of being the best aerosolized therapy for VAP was tobramycin with respect to clinical recovery and mortality, and colistin for microbiological eradication. Although this was a hypothesis-generating study, the current study is the first network meta-analysis to compare different aerosolized antibiotics in the treatment of VAP. The present meta-analysis is different from the two previous ones [4, 5]. We have updated the studies for this analysis, separately compared each aerosolized antibiotic with intravenous therapy, assessed the quality of evidence, detected publication bias, and conducted sensitivity analyses. A previous meta-analysis by Zampieri et al. investigated the role of aerosolized antibiotics in VAP treatment [4]. This analysis found the same benefits as our analysis on clinical recovery, mortality, and nephrotoxicity, but aerosolized antibiotics did not increase the rate for microbiological eradication. Contrary to their microbiological eradication findings, our analysis indicated that aerosolized antibiotics also have a beneficial effect. Thus, there may have been an inadequate sample size to correct the type II error in the study of Zampieri et al. In addition, we used network meta-analysis to identify an optimal aerosolized antibiotic for VAP.

VAP remains an important infectious complication of mechanical ventilation and is commonly due to MDR pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, P. aeruginosa, and enterobacter spp.). Because of MDR pathogens, the capability of commonly used intravenous antibiotics to cross the lung parenchyma is significantly inhibited [26, 27]. Inadequate concentrations of intravenous antibiotics may result in failure to reach inhibitory concentrations. Aerosolized antibiotics may be a useful treatment since aerosolization directly targets the airways and localizes the drug to the pulmonary parenchyma, thus bypassing the poor lung penetration of many antibiotics. Aerosolized antibiotics therefore make it possible to achieve high local antibiotic concentrations relative to an organism’s minimum inhibitory concentration while concurrently minimizing systemic toxicities by concentrating antibiotics in the lungs rather than spreading them throughout the body [28].

The appropriate aerosolized antibiotic remains a matter of controversy, and the most studied are colistin and aminoglycosides. The selection of the aerosolized antibiotic should encompass several properties and characteristics to achieve maximum effectiveness including: 1) activity against the causative pathogen; 2) physical properties to ensure maximal pulmonary delivery and minimal extrapulmonary loss; and 3) the achievement of adequate concentrations in the lung well above the pathogen’s minimum inhibitory concentration, taking into account the need for the prevention of resistance and the presence of biofilm [29].

In the presence of severe experimental lung infection, aminoglycoside plasma concentrations were found in the same range after nebulization and intravenous administration [30]. Furthermore, inhaled aminoglycosides prevent growth of bacterial biofilms [31]. Inhaled tobramycin has a wide range of activity against Gram-negative organisms, including P. aeruginosa. Tobramycin is also preferable for inhaled use because of moderately lipophilic and positively charged small molecules [27]. Amikacin is another aminoglycoside. The low bioavailability of nebulized amikacin may result in administration of high dosesand hence potentially increase systemic toxicities. Mohr et al. reported that pharmacokinetic properties and dosing strategies were better defined for inhaled tobramycin than for inhaled amikacin [32]. Studies in animals have shown that aerosolized colistin has a limited systemic diffusion in pneumonia [33]. Likewise, inhaled colistin also has high mucin binding that might lead to insufficient antibiotic effectiveness to kill bacteria [34]. As a consequence, a dosage exceeding the common dose of colistin treating VAP may enhance the rate of clinical recovery and microbiological eradication but increase the risk of toxicity. Therefore, tobramycin may have more potential effects on clinical recovery and be promising for its effects on mortality and nephrotoxicity.

In seeking to optimize treatment, network meta-analysis was used to gain further insight into the best preferred agent. The present network meta-analysis found that aerosolized tobramycin and colistin (especially tobramycin) were more likely to increase the rate of clinical recovery. Aerosolized tobramycin also had additional benefits on mortality, and aerosolized colistin had a higher rate of microbiological eradication. Amikacin had no significant differences in clinical recovery, microbiological eradication, mortality, or nephrotoxicity compared with intravenous antibiotics. Accordingly, the present network meta-analysis and the clustered ranking plot suggest that tobramycin present the best outcome for clinical recovery and mortality, and colistin present the best outcome for microbiological eradication.

Aerosolized antibiotics seem to be attractive alternatives for VAP treatment. However, an in-vivo randomized controlled trial examining adjuvant therapy with aerosolized antibiotics in VAP with varying degrees of bacterial resistance has shown that aerosolized antibiotics have no effect on the clinical course, including the serial Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score (CPIS), clinical cure rates, ventilator-free and ICU days, or mortality [24]. Despite the weak evidence in our analysis suggesting that the administration of aerosolized antibiotics such as colistin or tobramycin instead of the administration of intravenous antibiotics might be a good option for the treatment of VAP, there may as yet be no recommendations for using them in standard clinical practice. The rationale for the recommendation of aerosolized antibiotics requires other large multicenter trials to determine if these preliminary findings will result in better clinical activity and decreased microbial resistance in patients with VAP.

Some important limitations of the study should not be overlooked. First, different criteria for clinical recovery, microbiological eradication, and nephrotoxicity in the included trials might affect the robustness of our findings. The endpoint of microbiologic eradication is of uncertain value when measured during the use of inhaled antibiotics since the inhaled antibiotics are in the respiratory sample sent for culture which may influence the accuracy of the endpoint. Second, there are many factors which may impact the effect of inhaled antibiotics including types of nebulizers, ventilator settings, ventilator and circuit connections, and circuit humidification and filtering. We could not obtain sufficient data suggesting that other study design issues should be addressed. Third, the eligible studies had substantial differences in terms of the causative microorganisms, and the impact of inhaled antibiotics might vary against different pathogens. Fourth, a major concern when small studies are included in our analysis is the presence of a “small-study effect”, which arises from publication bias and selection bias and results in lower methodological quality [35]. The small-study effect was present in the analysis of treatment success in VAP patients with respect to aerosolized antibiotics. This should be taken into careful consideration when evaluating the results of the present analysis. Fifth, although network meta-analysis allowed us to compare the efficacy and safety of inhaled antibiotics, we acknowledge the limitation that interpretation of a network meta-analysis relies on the insufficient indirect comparison of outcomes through common comparators. Sixth, we included observational studies and randomized controlled trials; however, observational studies have the risk of overrated pooled estimates.

Conclusions

Aerosolized antibiotics appear to be useful treatment for VAP with respect to clinical recovery and microbiological eradication, and do not seem to increase mortality or nephrotoxicity risks. Our network meta-analysis in patients with VAP suggests that clinical recovery benefits are associated with aerosolized tobramycin and colistin (especially tobramycin), microbiological eradication with aerosolized colistin, and survival with aerosolized tobramycin, mostly based on observational studies. Moreover, we should take into account that some studies using aerosolized antibiotics failed to show an improvement, and data of other studies are still not published. Due to the low level of evidence, definitive recommendations cannot be made before additional large randomized studies are carried out.

Key messages

Aerosolized antibiotics appear to be beneficial for the treatment of VAP.

The current evidence from network meta-analysis indicates that aerosolized tobramycin is associated with the best outcome on clinical recovery and mortality.

The current evidence from network meta-analysis indicates that aerosolized colistin is associated with improved clinical recovery and microbiological eradication.

Additional files

Figure S1. Forest plots showing the effect of aerosolized antibiotics on (A) clinical recovery, (B) microbiological eradication, (C) mortality, and (D) nephrotoxicity. (TIF 8222 kb)

Figure S2. Funnel plots for the rate of (A) clinical recovery, (B) microbiological eradication, (C) mortality, and (D) nephrotoxicity. (TIF 2106 kb)

Figure S3. Sensitivity analyses of the included studies reporting aerosolized antibiotics on (A) clinical recovery, (B) microbiological eradication, (C) mortality, and (D) nephrotoxicity. (TIF 4998 kb)

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by Major Projects of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81490532 to HHS and 91642202 to WL), and the program for Key Site of National Clinical Research Center for Respiratory Disease.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated and/or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence interval

- CI

Confidence interval

- HAP

Hospital-associated pneumonia

- HAP

Hospital-associated pneumonia

- MDR

Multidrug resistant

- NMA

Network meta-analysis

- NMA

Network meta-analysis

- NOS

Newcastle-Ottawa scale

- NOS

Newcastle-Ottawa scale

- RCT

Randomized controlled trials

- RR

Risk ratio

- RR

Risk ratio

- VAP

Ventilator-associated pneumonia

- VAP

Ventilator-associated pneumonia

Authors’ contributions

FX and LLH conducted the literature searches, selected the studies, and assessed the study quality. FX, LLH, and LQC screened the abstracts, selected the studies meeting the inclusion criteria, extracted the data, and assessed the study quality. FX and LLH drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kollef MH. What is ventilator-associated pneumonia and why is it important? Respir Care. 2005;50(6):714–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ehrmann S, Chastre J, Diot P, Lu Q. Nebulized antibiotics in mechanically ventilated patients: a challenge for translational research from technology to clinical care. Ann Intensive Care. 2017;7(1):78. doi: 10.1186/s13613-017-0301-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer LB. Aerosolized antibiotics in critically ill ventilated patients. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2009;15(5):413–418. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e328330abcf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zampieri FG, Nassar AP, Jr, Gusmao-Flores D, Taniguchi LU, Torres A, Ranzani OT. Nebulized antibiotics for ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical Care. 2015;19:150. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0868-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sole-Lleonart C, Rouby JJ, Blot S, Poulakou G, Chastre J, Palmer LB, Bassetti M, Luyt CE, Pereira JM, Riera J, et al. Nebulization of antiinfective agents in invasively mechanically ventilated adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesthesiology. 2017;126(5):890–908. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naing C, Reid SA, Aung K. Comparing antibiotic treatment for leptospirosis using network meta-analysis: a tutorial. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-2145-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang P, Lv Q, Lai T, Xu F. Does hypomagnesemia impact on the outcome of patients admitted to the intensive care unit? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Shock. 2017;47(3):288–295. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du F, Jiang P, He S, Song D, Xu F. Antiplatelet therapy for critically ill patients: a pairwise and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Shock. 2018;49(6):616–624. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghannam DE, Rodriguez GH, Raad II, Safdar A. Inhaled aminoglycosides in cancer patients with ventilator-associated gram-negative bacterial pneumonia: safety and feasibility in the era of escalating drug resistance. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28(3):253–259. doi: 10.1007/s10096-008-0620-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kofteridis DP, Alexopoulou C, Valachis A, Maraki S, Dimopoulou D, Georgopoulos D, Samonis G. Aerosolized plus intravenous colistin versus intravenous colistin alone for the treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a matched case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(11):1238–1244. doi: 10.1086/657242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korbila IP, Michalopoulos A, Rafailidis PI, Nikita D, Samonis G, Falagas ME. Inhaled colistin as adjunctive therapy to intravenous colistin for the treatment of microbiologically documented ventilator-associated pneumonia: a comparative cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16(8):1230–1236. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perez-Pedrero MJ, Sanchez-Casado M, Rodriguez-Villar S. Nebulized colistin treatment of multi-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii pulmonary infection in critical ill patients. Med Int. 2011;35(4):226–231. doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalin G, Alp E, Coskun R, Demiraslan H, Gundogan K, Doganay M. Use of high-dose IV and aerosolized colistin for the treatment of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii ventilator-associated pneumonia: do we really need this treatment? J Infect Chemother. 2012;18(6):872–877. doi: 10.1007/s10156-012-0430-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doshi NM, Cook CH, Mount KL, Stawicki SP, Frazee EN, Personett HA, Schramm GE, Arnold HM, Murphy CV. Adjunctive aerosolized colistin for multi-drug resistant gram-negative pneumonia in the critically ill: a retrospective study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2013;13(1):45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-13-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tumbarello M, De Pascale G, Trecarichi EM, De Martino S, Bello G, Maviglia R, Spanu T, Antonelli M. Effect of aerosolized colistin as adjunctive treatment on the outcomes of microbiologically documented ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by colistin-only susceptible gram-negative bacteria. Chest. 2013;144(6):1768–1775. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Migiyama Y, Hirosako S, Tokunaga K, Migiyama E, Tashiro T, Sagishima K, Kamohara H, Kinoshita Y, Kohrogi H. Aerosolized tobramycin for Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le Conte P, Potel G, Clementi E, Legras A, Villers D, Bironneau E, Cousson J, Baron D. Administration of tobramycin aerosols in patients with nosocomial pneumonia: a preliminary study. Presse Med. 2000;29(2):76–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hallal A, Cohn SM, Namias N, Habib F, Baracco G, Manning RJ, Crookes B, Schulman CI. Aerosolized tobramycin in the treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a pilot study. Surg Infect. 2007;8(1):73–82. doi: 10.1089/sur.2006.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rattanaumpawan P, Lorsutthitham J, Ungprasert P, Angkasekwinai N, Thamlikitkul V. Randomized controlled trial of nebulized colistimethate sodium as adjunctive therapy of ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by gram-negative bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(12):2645–2649. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu Q, Yang J, Liu Z, Gutierrez C, Aymard G, Rouby JJ. Nebulized ceftazidime and amikacin in ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(1):106–115. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1894OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niederman MS, Chastre J, Corkery K, Fink JB, Luyt CE, Garcia MS. BAY41-6551 achieves bactericidal tracheal aspirate amikacin concentrations in mechanically ventilated patients with gram-negative pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(2):263–271. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2420-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmer LB, Smaldone GC. Reduction of bacterial resistance with inhaled antibiotics in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(10):1225–1233. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201312-2161OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdellatif S, Trifi A, Daly F, Mahjoub K, Nasri R, Ben Lakhal S. Efficacy and toxicity of aerosolised colistin in ventilator-associated pneumonia: a prospective, randomised trial. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s13613-016-0127-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kollef MH, Ricard JD, Roux D, Francois B, Ischaki E, Rozgonyi Z, Boulain T, Ivanyi Z, Janos G, Garot D, et al. A randomized trial of the amikacin Fosfomycin inhalation system for the adjunctive therapy of gram-negative ventilator-associated pneumonia: IASIS trial. Chest. 2017;151(6):1239–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnold HM, Sawyer AM, Kollef MH. Use of adjunctive aerosolized antimicrobial therapy in the treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii ventilator-associated pneumonia. Respir Care. 2012;57(8):1226–1233. doi: 10.4187/respcare.01556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imberti R, Cusato M, Villani P, Carnevale L, Iotti GA, Langer M, Regazzi M. Steady-state pharmacokinetics and BAL concentration of colistin in critically ill patients after IV colistin methanesulfonate administration. Chest. 2010;138(6):1333–1339. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grgurich PE, Hudcova J, Lei Y, Sarwar A, Craven DE. Management and prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2012;6(5):533–555. doi: 10.1586/ers.12.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang C, Berra L, Klompas M. Should aerosolized antibiotics be used to treat ventilator-associated pneumonia? Respir Care. 2016;61(6):737–748. doi: 10.4187/respcare.04748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poulakou G, Matthaiou DK, Nicolau DP, Siakallis G, Dimopoulos G. Inhaled antimicrobials for ventilator-associated pneumonia: practical aspects. Drugs. 2017;77(13):1399–1412. doi: 10.1007/s40265-017-0787-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elman M, Goldstein I, Marquette CH, Wallet F, Lenaour G, Rouby JJ. Influence of lung aeration on pulmonary concentrations of nebulized and intravenous amikacin in ventilated piglets with severe bronchopneumonia. Anesthesiology. 2002;97(1):199–206. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200207000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adair CG, Gorman SP, Byers LM, Jones DS, Feron B, Crowe M, Webb HC, McCarthy GJ, Milligan KR. Eradication of endotracheal tube biofilm by nebulised gentamicin. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(4):426–431. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohr AM, Sifri ZC, Horng HS, Sadek R, Savetamal A, Hauser CJ, Livingston DH. Use of aerosolized aminoglycosides in the treatment of gram-negative ventilator-associated pneumonia. Surg Infect. 2007;8(3):349–357. doi: 10.1089/sur.2006.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pereira GH, Muller PR, Levin AS. Salvage treatment of pneumonia and initial treatment of tracheobronchitis caused by multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli with inhaled polymyxin B. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;58(2):235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang JX, Blaskovich MA, Pelingon R, Ramu S, Kavanagh A, Elliott AG, Butler MS, Montgomery AB, Cooper MA. Mucin binding reduces colistin antimicrobial activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(10):5925–5931. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00808-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sterne JA, Gavaghan D, Egger M. Publication and related bias in meta-analysis: power of statistical tests and prevalence in the literature. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(11):1119–1129. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Forest plots showing the effect of aerosolized antibiotics on (A) clinical recovery, (B) microbiological eradication, (C) mortality, and (D) nephrotoxicity. (TIF 8222 kb)

Figure S2. Funnel plots for the rate of (A) clinical recovery, (B) microbiological eradication, (C) mortality, and (D) nephrotoxicity. (TIF 2106 kb)

Figure S3. Sensitivity analyses of the included studies reporting aerosolized antibiotics on (A) clinical recovery, (B) microbiological eradication, (C) mortality, and (D) nephrotoxicity. (TIF 4998 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and/or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.