Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

Is oral dydrogesterone 30 mg daily non-inferior to 8% micronized vaginal progesterone (MVP) gel 90 mg daily for luteal phase support in IVF?

SUMMARY ANSWER

Oral dydrogesterone demonstrated non-inferiority to MVP gel for the presence of fetal heartbeats at 12 weeks of gestation (non-inferiority margin 10%).

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

The standard of care for luteal phase support in IVF is the use of MVP; however, it is associated with vaginal irritation, discharge and poor patient compliance. Oral dydrogesterone may replace MVP as the standard of care if it is found to be efficacious with an acceptable safety profile.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION

Lotus II was a randomized, open-label, multicenter, Phase III, non-inferiority study conducted at 37 IVF centers in 10 countries worldwide, from August 2015 until May 2017. In total, 1034 premenopausal women (>18 to <42 years of age) undergoing IVF were randomized 1:1 (stratified by country and age group), using an Interactive Web Response System, to receive oral dydrogesterone 30 mg or 8% MVP gel 90 mg daily.

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

Subjects received either oral dydrogesterone (n = 520) or MVP gel (n = 514) on the day of oocyte retrieval, and luteal phase support continued until 12 weeks of gestation. The primary outcome measure was the presence of fetal heartbeats at 12 weeks of gestation, as determined by transvaginal ultrasound.

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE

Non-inferiority of oral dydrogesterone was demonstrated, with pregnancy rates in the full analysis sample (FAS) at 12 weeks of gestation of 38.7% (191/494) and 35.0% (171/489) in the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups, respectively (adjusted difference, 3.7%; 95% CI: −2.3 to 9.7). Live birth rates in the FAS of 34.4% (170/494) and 32.5% (159/489) were obtained for the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups, respectively (adjusted difference 1.9%; 95% CI: −4.0 to 7.8). Oral dydrogesterone was well tolerated and had a similar safety profile to MVP gel.

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION

The analysis of the results was powered to consider the ongoing pregnancy rate, but a primary objective of greater clinical interest may have been the live birth rate. This study was open-label as it was not technically feasible to make a placebo applicator for MVP gel, which may have increased the risk of bias for the subjective endpoints reported in this study. While the use of oral dydrogesterone in fresh-cycle IVF was investigated in this study, further research is needed to investigate its efficacy in programmed frozen-thawed cycles where corpora lutea do not exist.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

This study demonstrates that oral dydrogesterone is a viable alternative to MVP gel, due to its comparable efficacy and tolerability profiles. Owing to its patient-friendly oral administration route, dydrogesterone may replace MVP as the standard of care for luteal phase support in fresh-cycle IVF.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTERESTS(S)

This study was sponsored and supported by Abbott. G.G. has received investigator fees from Abbott during the conduct of the study. Outside of this submitted work, G.G. has received non-financial support from MSD, Ferring, Merck-Serono, IBSA, Finox, TEVA, Glycotope and Gedeon Richter, as well as personal fees from MSD, Ferring, Merck-Serono, IBSA, Finox, TEVA, Glycotope, VitroLife, NMC Healthcare, ReprodWissen, Biosilu, Gedeon Richter and ZIVA. C.B. is the President of the Belgian Society of Reproductive Medicine (unpaid) and Section Editor of Reproductive BioMedicine Online. C.B. has received grants from Ferring Pharmaceuticals, participated in an MSD sponsored trial, and has received payment from Ferring, MSD, Biomérieux, Abbott and Merck for lectures. G.S. has no conflicts of interest to be declared. A.P. is the General Secretary of the Indian Society of Assisted Reproduction (2017–2018). B.D. is President of Pune Obstetric and Gynecological Society (2017–2018). D.-Z.Y. has no conflicts of interest to be declared. Z.-J.C. has no conflicts of interest to be declared. E.K. is an employee of Abbott Laboratories GmbH, Hannover, Germany and owns shares in Abbott. C.P.-F. is an employee of Abbott GmbH & Co. KG, Wiesbaden, Germany and owns shares in Abbott. H.T.’s institution has received grants from Merck, MSD, Goodlife, Cook, Roche, Origio, Besins, Ferring and Mithra (now Allergan); and H.T. has received consultancy fees from Finox-Gedeon Richter, Merck, Ferring, Abbott and ObsEva.

TRIAL REGISTRATION NUMBER

NCT02491437 (clinicaltrials.gov).

TRIAL REGISTRATION DATE

08 July 2015.

DATE OF FIRST PATIENT’S ENROLLMENT

17 August 2015.

Keywords: dydrogesterone, luteal phase support, micronized vaginal progesterone gel, IVF, randomized clinical trial

Introduction

Controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) techniques that use gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues are routinely used during IVF; however, COS often causes endocrine defects in the luteal phase, which may jeopardize embryo implantation and maintenance of early pregnancy (Macklon and Fauser, 2000). As a result, luteal phase support is necessary to support embryo implantation and to enhance the probability of an ongoing pregnancy (Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, 2008). Progesterone has most commonly been used for luteal phase support and has been associated with an improvement in pregnancy rates in IVF treatment (Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, 2008; van der Linden et al., 2015).

Various routes of progesterone administration for luteal phase support have been explored, with no single formulation or regimen identified as superior regarding efficacy (Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, 2008; van der Linden et al., 2015). Progesterone for luteal phase support can be administered orally, intramuscularly, vaginally and most recently subcutaneously, with each route having different bioavailability and tolerability profiles (Simon et al., 1993; Tavaniotou et al., 2000; Vaisbuch et al., 2012; Sator et al., 2013). For instance, oral micronized progesterone has low bioavailability and is associated with systemic adverse events such as drowsiness, dizziness and headaches (Tavaniotou et al., 2000; Besins Healthcare (UK) Ltd, 2017). In contrast, intramuscular progesterone is associated with injection-site pain and abscesses (Tavaniotou et al., 2000; Beltsos et al., 2014). Micronized vaginal progesterone (MVP) is now preferred over oral and intramuscular progesterone at most IVF centers, but it is associated with its own administration-related side effects such as vaginal irritation (Vaisbuch et al., 2012; Lockwood et al., 2014). MVP is usually administered as a gel or as capsules (Vaisbuch et al., 2012), with both formulations having similar efficacy for luteal phase support (Kleinstein and Luteal Phase Study Group, 2005; Simunic et al., 2007; Doody et al., 2009). Overall, there is a clinical need to provide a treatment that is efficacious, well tolerated, and easy to use, in order to improve patient satisfaction and treatment compliance among women undergoing IVF.

Dydrogesterone is a retroprogesterone that has been used since the 1960s for the treatment of conditions associated with progesterone deficiency (Mirza et al., 2016). Dydrogesterone is a more selective progesterone receptor agonist than progesterone, with lower affinity for androgen and glucocorticoid receptors (Rižner et al., 2011). Importantly, oral administration of dydrogesterone circumvents the inconvenience and side effects related to intravaginal or intramuscular administration (Tavaniotou et al., 2000; Beltsos et al., 2014; Lockwood et al., 2014).

Numerous small-scale clinical trials and meta-analyses have indicated that dydrogesterone is at least as efficacious as MVP for luteal phase support (Chakravarty et al., 2005; Patki and Pawar, 2007; Ganesh et al., 2011; van der Linden et al., 2011, 2015; Salehpour et al., 2013; Tomic et al., 2015; van der Linden et al., 2015; Barbosa et al., 2016; Saharkhiz et al., 2016; Zargar et al., 2016); however, a recent meta-analysis reported that the methodology of many of the studies was not optimal and the quality of the available evidence was judged low (van der Linden et al., 2015). More recently, two new clinical studies (Lotus I and Lotus II) have been conducted for luteal phase support. The randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, Phase III study (Lotus I), conducted in 1031 women, demonstrated that oral dydrogesterone was non-inferior to MVP capsules in terms of pregnancy rates at 12 weeks of gestation following luteal phase support (Tournaye et al., 2017). The objectives of this open-label, Phase III study (Lotus II) were to establish the non-inferiority of oral dydrogesterone versus MVP gel in terms of pregnancy rates at 12 weeks of gestation following luteal phase support, and to obtain safety and tolerability data. Since the publication of Lotus I and the completion of Lotus II, dydrogesterone has been approved for use in luteal support as part of assisted reproductive technology treatment in several countries.

Materials and Methods

Study design

Lotus II, a randomized, open-label, multicenter, parallel-group, Phase III, non-inferiority study was conducted at 37 IVF centers in 10 countries (Australia, Belgium, China, Germany, Hong Kong, India, Russia, Singapore, Thailand and Ukraine) from 17 August 2015 until 26 May 2017. Lotus II was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Abbott Laboratories GmbH (or an authorized representative) or the investigator (according to national provisions) obtained written approval of the clinical study protocol (including amendments), the written subject informed consent form, informed consent updates, subject recruitment procedures and any other written information provided to subjects from an Independent Ethics Committee (IEC)/Institutional Review Board (IRB), complying with the local regulatory requirements. Written approval of the study was obtained from the IEC/IRB before study commencement.

Participants

Premenopausal women (>18 to <42 years of age) with a documented history of infertility who were planning to undergo IVF with or without ICSI, and who gave written informed consent, were enrolled in the study. Other key inclusion criteria included: absence of pregnancy; body mass index ≥18 to ≤30 kg/m2; early follicular phase (Days 2–4); FSH ≤15 IU/L and estradiol within normal clinical limits at screening; LH, prolactin (PRL), testosterone and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) within normal clinical limits or not considered clinically significant within 6 months prior to or at screening; normal transvaginal ultrasound at screening (or within 14 days prior to screening); and single or double fresh embryo transfer. Key exclusion criteria included: evidence of head, ear, eye, nose, throat, cardiovascular, respiratory, urogenital, gastrointestinal/hepatic, hematologic/immunologic, dermatologic/connective tissue, musculoskeletal, metabolic/nutritional, endocrine or neurologic/psychiatric disorders; allergy; recent major surgery (within 3 months); current or recent substance abuse, including that of alcohol and tobacco; history of chemotherapy; more than three unsuccessful IVF attempts; and history of recurrent pregnancy loss. The use of additional progesterone products was not permitted during the study.

During the study, there was a minor amendment to subject eligibility criteria. It became apparent that most Asian IVF centers were not routinely testing for LH, PRL, testosterone and TSH prior to IVF cycles. Therefore, the assessment of these hormones was added as a requirement at screening for those subjects who did not have available values.

Randomization and masking

The investigators enrolled the subjects; thereafter, the subjects were assigned to treatment groups using a centralized electronic system (Interactive Response Technology), which assigned a five-digit randomization number to each subject according to the randomization scheme provided by Clinical Supply Management of Abbott Healthcare Products B.V. Subjects were randomized 1:1 into the oral dydrogesterone or MVP gel treatment groups and were stratified by country and age group (<35 and ≥35 years of age). Lotus II was open-label, as it was not technically feasible to make a placebo applicator for MVP gel.

Procedures

During the screening process, subjects signed an informed consent form and the following parameters were analyzed: vital signs, concomitant medication, laboratory blood values, and pregnancy status (by transvaginal ultrasound if the last transvaginal examination was older than 14 days). On the day of oocyte retrieval (Day 1), subjects were randomly assigned to receive either oral dydrogesterone 10 mg tablets (Duphaston®; Abbott Biologicals, Netherlands) three times daily or 8% MVP gel 90 mg (Crinone®; Central Pharma Ltd, UK) once daily and luteal phase support was started. The dose of oral dydrogesterone for the Lotus clinical trial program was chosen based on the results of previous randomized controlled trials (Chakravarty et al., 2005; Patki and Pawar, 2007; Ganesh et al., 2011), histological data (Fatemi et al., 2007) and recommendations by IVF specialists.

Embryo transfer was performed on Day 3–6 after oocyte retrieval according to the clinic-specific IVF protocol. On Day 17–20 (Day 15 ± 3 after embryo transfer; 4 weeks of gestation), subjects had a pregnancy test (serum measurement of beta human chorionic gonadotropin). If pregnancy was confirmed on Day 43 ± 3 (Week 6; 8 weeks of gestation), luteal phase support was continued up to Day 71 ± 3 (Week 10; 12 weeks of gestation), at which point the presence of a fetal heartbeat was determined by transvaginal ultrasound. Treatment emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and concomitant treatment were recorded throughout the study. At delivery, gestational age and newborn parameters were obtained; 30 ± 3 days after delivery, the mother’s and newborn’s safety and wellbeing were recorded. The 10-week duration of luteal phase support was agreed by the Medical Evaluations Board to align with the dosing schedule of MVP capsules (Utrogestan®; Besins Healthcare, Belgium) used as the comparator in Lotus I (Tournaye et al., 2017).

The safety sample included all randomized subjects who received at least one drug administration. The full analysis sample (FAS) consisted of all subjects in the safety sample who had a successful embryo transfer or discontinued before embryo transfer due to study drug-related issues. The per-protocol sample (PPS) consisted of all subjects in the FAS who did not present any major protocol deviations.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was pregnancy rate at 12 weeks of gestation (Week 10 of treatment), as determined by a transvaginal ultrasound. Key secondary outcomes were: the frequency of positive pregnancy tests on Day 15 after embryo transfer, live birth rate and the number of healthy newborns. Newborn assessments included appearance, pulse, grimace, activity and respiration (APGAR) score; weight; height; head circumference; abnormal findings of physical examination; and any malformations. The safety outcomes were TEAEs and treatment-emergent serious adverse events (TESAEs) during the study period.

Statistical analyses

Assuming a 35% pregnancy rate for both treatment groups based on previous studies and verification with an EU Health Authority, it was estimated that a sample size of 479 subjects per group would provide 90% power to demonstrate non-inferiority with a margin of 10%. Taking into account a 10% dropout rate, an overall sample size of 1066 subjects was planned.

The primary efficacy analysis consisted of constituting a two-sided 95% CI using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test stratified for country and age group (<35 and ≥35 years of age) estimating the difference in pregnancy rates between the two treatment groups and the normal distribution as approximation. Non-inferiority of dydrogesterone versus MVP gel was demonstrated if the lower bound of the 95% CI excluded a difference greater than the prespecified non-inferiority margin of −10%. The non-inferiority margin of −10% was chosen for clinical relevance and was agreed with the Medical Evaluations Board prior to initiating the Lotus program. The non-inferiority margin used in the Lotus program was the same as that used in two other recent Phase III studies of drugs now approved for luteal phase support in IVF (Endometrin®; Ferring Pharmaceuticals, USA and Prolutex®; IBSA Institut Biochimique SA, Switzerland) (Doody et al., 2009; Lockwood et al., 2014).

Pregnancy rates at Day 15 after embryo transfer and Day 43 (4 and 8 weeks of gestation) and live birth rates were analyzed using the same methods as for the primary efficacy analysis. Flow of subjects through the trial, demographics, concomitant medication and safety data were summarized by treatment group.

The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02491437).

Results

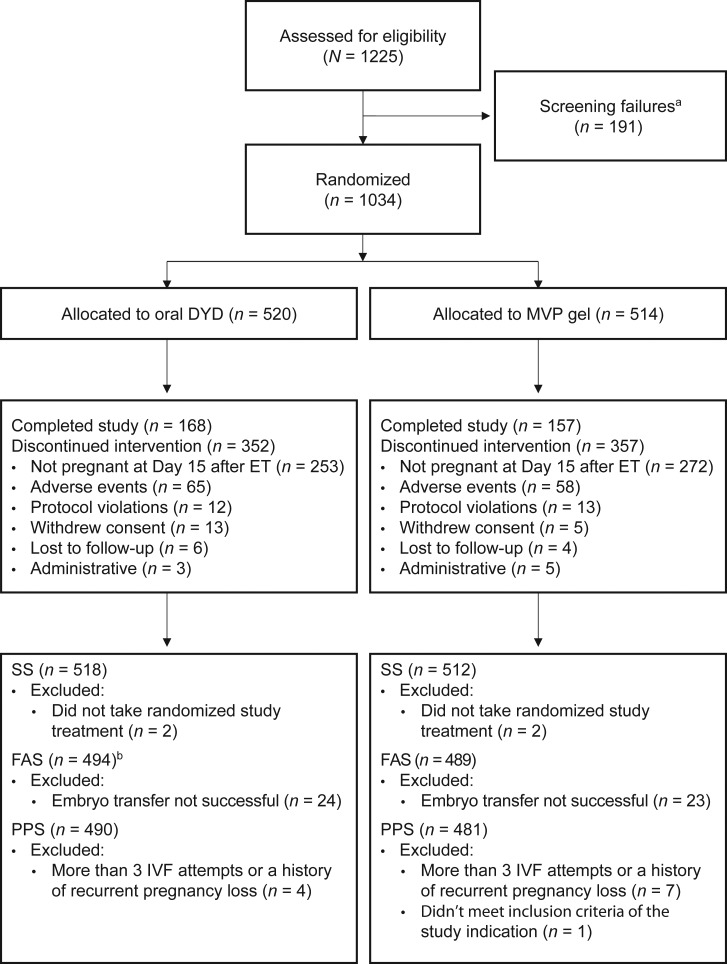

Between 17 August 2015 and 26 May 2017, 1225 subjects were enrolled in the study and 1034 subjects were randomized to receive oral dydrogesterone (n = 520) or MVP gel (n = 514); of these, 494 and 489 subjects were included in the FAS, and 490 and 481 subjects were included in the PPS, respectively (Fig. 1). Overall, 32.3 and 30.5% of subjects in the dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups completed the study, respectively. The primary reason for discontinuing was pregnancy not confirmed at Day 15 after embryo transfer (48.7 and 52.9% of subjects in the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups, respectively). Demographics and baseline characteristics are shown in Table I and were similar between the treatment groups. Subjects in the FAS were predominantly Asian or White (49.5 and 49.2%, respectively) and <35 years of age (70.4%).

Figure 1.

Subject disposition (CONSORT flow diagram). aDetermined by inclusion/exclusion criteria. bThree subjects in the oral dydrogesterone group were discontinued prior to embryo transfer due to study drug-related issues; these subjects were included in the FAS as failures. DYD, dydrogesterone; ET, embryo transfer; FAS, full analysis sample; IVF, in vitro fertilization; MVP, micronized vaginal progesterone; PPS, per-protocol sample; SS, safety sample.

Table I.

Subject demographics and baseline characteristics (FAS).

| Oral DYD (N = 494) | MVP Gel (N = 489) | All Subjects (N = 983) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (SD) | 31.8 (4.4) | 31.6 (4.6) | 31.7 (4.5) |

| Age category, n (%) | |||

| <35 years | 348 (70.4) | 344 (70.3) | 692 (70.4) |

| ≥35 years | 146 (29.6) | 145 (29.7) | 291 (29.6) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Asian | 250 (50.6) | 237 (48.5) | 487 (49.5) |

| Black | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| White | 237 (48.0) | 247 (50.5) | 484 (49.2) |

| Other | 6 (1.2) | 5 (1.0) | 11 (1.1) |

| Mean BMI, kg/m2 (SD) | 23.1 (3.1) | 23.1 (3.0) | 23.1 (3.0) |

| Prior treatment, n (%) | 71 (14.4) | 61 (12.5) | 132 (13.4) |

BMI, body mass index; DYD, dydrogesterone; FAS, full analysis sample; MVP, micronized vaginal progesterone; SD, standard deviation.

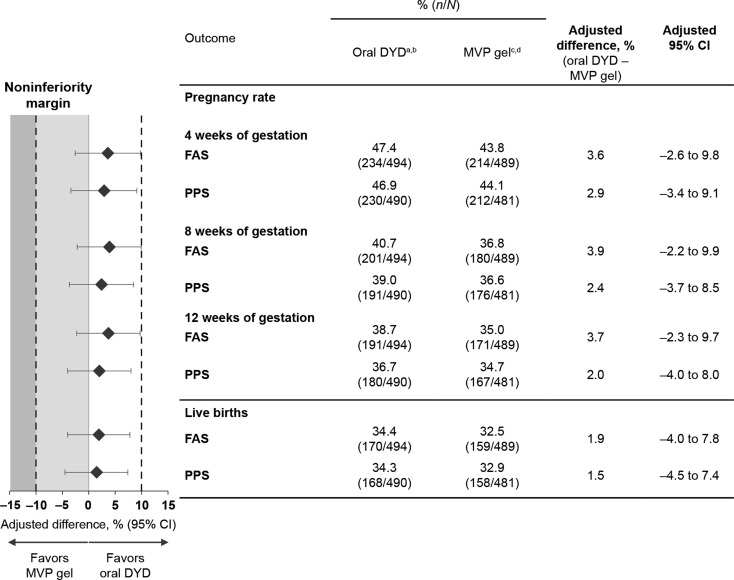

The primary endpoint was met in both the FAS and PPS, with oral dydrogesterone achieving non-inferiority to MVP gel for pregnancy rate at 12 weeks of gestation. For the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups, pregnancy rates at 12 weeks of gestation were 38.7 and 35.0% in the FAS (adjusted difference, 3.7%; 95% CI: −2.3 to 9.7), and 36.7 and 34.7% in the PPS (adjusted difference, 2.0%; 95% CI: −4.0 to 8.0), respectively (Fig. 2). As the lower-bound CIs were greater than the non-inferiority margin of −10%, non-inferiority of oral dydrogesterone versus MVP gel was demonstrated in both the FAS and PPS. As prespecified in the protocol, the primary endpoint was adjusted for country and age; no relevant interaction was observed between the treatment and country or age group. Analysis of subjects in the FAS who underwent a single embryo transfer identified comparable pregnancy rates at 12 weeks of gestation between the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups (adjusted difference, 0.4%; 95% CI: −10.0 to 10.8). In subjects who underwent a double embryo transfer, pregnancy rates at 12 weeks of gestation were also comparable in the oral dydrogesterone group compared with the MVP gel group (adjusted difference, 5.3%; 95% CI: −2.2 to 12.7).

Figure 2.

Pregnancy and live birth rates post-treatment. Pregnancy rates at 4, 8 and 12 weeks of gestation, and the live birth rates (all statistically adjusted for country and age group) are shown for the FAS and PPS. A non-inferiority margin of 10% was used, whereby the test drug is non-inferior to the comparator if the lower-bound 95% CI excludes a difference greater than −10%. aDenominators: Four subjects were removed from the oral dydrogesterone PPS (N = 490) compared with the FAS (N = 494) because all four subjects had more than three IVF attempts, which was an exclusion criterion. bNominators at 12 weeks of gestation (primary endpoint): Eleven subjects were removed from the oral dydrogesterone PPS (n = 180) compared with the FAS (n = 191) because nine pregnant subjects took additional progesterone before 12 weeks of gestation (counted as success in FAS, but failure in PPS), and two subjects had major protocol deviations (excluded from the PPS). cDenominators: Eight subjects were removed from the MVP gel PPS (N = 481) compared with the FAS (N = 489) because seven subjects had more than three IVF attempts, which was an exclusion criterion, and one additional subject did not meet the inclusion criteria. dNominators at 12 weeks of gestation (primary endpoint): Four subjects were removed from the MVP gel PPS (n = 167) compared with the FAS (n = 171) because three pregnant subjects took additional progesterone before 12 weeks of gestation (counted as success in FAS, but failure in PPS), and one subject had a major protocol deviation (excluded from the PPS). CI, confidence interval; DYD, dydrogesterone; FAS, full analysis sample; IVF, in vitro fertilization; MVP, micronized vaginal progesterone; PPS, per-protocol sample.

At 4 weeks of gestation, adjusted differences in pregnancy rates between the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups were 3.6% (95% CI: −2.6 to 9.8) in the FAS and 2.9% (95% CI: −3.4 to 9.1) in the PPS; at 8 weeks of gestation, these values were 3.9% (95% CI: −2.2 to 9.9) in the FAS and 2.4% (95% CI: −3.7 to 8.5) in the PPS (Fig. 2). In the FAS between 4 and 12 weeks of gestation, pregnancy rates in the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups decreased by 8.7 and 8.8%, respectively, suggesting a comparable miscarriage rate in the two treatment groups during this time frame.

Live birth rates of 34.4 and 32.5% in the FAS (adjusted difference, 1.9%; 95% CI: −4.0 to 7.8), and 34.3 and 32.9% in the PPS (adjusted difference, 1.5%; 95% CI: −4.5 to 7.4), were obtained for the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups, respectively (Fig. 2).

The course and outcomes of pregnancy in subjects treated with oral dydrogesterone or MVP gel are summarized in Table II. The number of embryos transferred was similar between the treatment groups, as was the number of newborns and the proportion of single and multiple births.

Table II.

Course and outcomes of pregnancy in subjects (FAS).

| Oral DYD | MVP Gel | All | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects who underwent embryo transfer, n | 491a | 489 | 980 |

| Subjects who underwent embryo transfer after ICSI, n (%) | 321 (65.4) | 304 (62.2) | 625 (63.8) |

| Day of embryo transfer after oocyte retrieval, n (%) | |||

| <5 days | 319 (65.0) | 286 (58.5) | 605 (61.7) |

| ≥5 days | 172 (35.0) | 203 (41.5) | 375 (38.3) |

| Number of embryos transferred, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 162 (33.0) | 164 (33.5) | 326 (33.3) |

| 2 | 324 (66.0) | 324 (66.3) | 648 (66.1) |

| >2 | 5 (1.0) | 1 (0.2) | 6 (0.6) |

| Subjects who had at least one newborn, n (%)b | 170 (34.6) | 159 (32.5) | 329 (33.6) |

| Total number of newborns, n | 205 | 188 | 393 |

| One newborn infant, n (%)c | 135 (79.4) | 131 (82.4) | 266 (80.9) |

| Two newborn infants, n (%)c | 35 (20.6) | 27 (17.0) | 62 (18.8) |

| More than two newborn infants, n (%)c | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) |

DYD, dydrogesterone; FAS, full analysis sample; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection; MVP, micronized vaginal progesterone.

aThree subjects in the oral dydrogesterone group were discontinued prior to embryo transfer.

bPercentages calculated according to the number of subjects in the FAS who underwent embryo transfer.

cPercentages calculated according to the number of subjects who had at least one newborn.

The proportions of subjects with at least one TEAE in the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups were 53.1 and 48.6%, respectively. The proportions of severe TEAEs and TESAEs were low in both treatment groups (severe TEAEs: 7.3 and 6.8%; TESAEs: 13.7 and 13.1% of subjects in the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups, respectively). There were no maternal deaths in either treatment group. The proportions of TEAEs leading to study termination in the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups were 12.4 and 11.1%, respectively (Table III). Only 6.0 and 5.9% of TEAEs in the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups, respectively, were reported by the investigators as having a reasonable possibility of a causal relationship with the study drug. The most common TEAE was vaginal hemorrhage, which was reported by 9.8% of subjects in the oral dydrogesterone group and 7.2% of subjects in the MVP gel group. The incidence of vulvovaginal signs and symptoms was low in both groups (vaginal discharge, 2.1 and 0.6%; vulvovaginal discomfort, 0.0 and 0.8%; vulvovaginal pruritus, 0.2 and 0.4% of subjects in the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups, respectively) (Table III).

Table III.

Maternal and fetal/neonatal TEAEs.

| Oral DYD (N = 518) | MVP Gel (N = 512) | All (N = 1030) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal population, n (%)a | |||

| All TEAEs | 275 (53.1) | 249 (48.6) | 524 (50.9) |

| At least one TESAE | 71 (13.7) | 67 (13.1) | 138 (13.4) |

| At least one severe TEAE | 38 (7.3) | 35 (6.8) | 73 (7.1) |

| TEAEs leading to study termination | 64 (12.4) | 57 (11.1) | 121 (11.7) |

| Deaths (maternal) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Vascular disorders | 12 (2.3) | 9 (1.8) | 21 (2.0) |

| Peripheral embolism and thrombosis | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | 89 (17.2) | 82 (16.0) | 171 (16.6) |

| Vaginal hemorrhage | 51 (9.8) | 37 (7.2) | 88 (8.5) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 69 (13.3) | 67 (13.1) | 136 (13.2) |

| Nervous system disorders | 19 (3.7) | 19 (3.7) | 38 (3.7) |

| Vulvovaginal signs and symptoms | 11 (2.1) | 9 (1.8) | 20 (1.9) |

| Vaginal discharge | 11 (2.1) | 3 (0.6) | 14 (1.4) |

| Vulvovaginal discomfort | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.8) | 4 (0.4) |

| Vulvovaginal pruritus | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | 3 (0.3) |

| Oral DYD (N = 221) | MVP Gel (N = 201) | All (N = 422) | |

| Fetal/neonatal population, n (%)b | |||

| At least one TESAE | 28 (12.7) | 23 (11.4) | 51 (12.1) |

| TEAEs of special interest: congenital, familial and genetic disorders | 14 (6.3) | 10 (5.0) | 24 (5.7) |

| Atrial septal defect | 5 (2.3) | 7 (3.5) | 12 (2.8) |

| Heart disease congenital | 2 (0.9) | 4 (2.0) | 6 (1.4) |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | 1 (0.5) | 4 (2.0) | 5 (1.2) |

| Congenital aortic anomaly | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) |

| Accessory auricle | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Amniotic band syndrome | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Congenital central nervous system anomaly | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Congenital cystic kidney disease | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Congenital hand malformation | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Cystic lymphangioma | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Intestinal malrotation | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Kinematic imbalances | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Renal dysplasia | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Turner’s syndrome | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

DYD, dydrogesterone; MVP, micronized vaginal progesterone; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event; TESAE, treatment-emergent serious adverse event.

aSafety sample.

bPercentages calculated based on the fetal/neonatal population, which included 16 and 13 miscarriages or stillbirths in the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups, respectively.

The most common TESAEs occurring in >1% of subjects in either treatment group were missed abortion (2.3 and 0.4% of subjects in the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups, respectively) and ovarian hyperstimulation (2.1 and 2.7% of subjects in the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups, respectively). Further analysis of all TEAEs related to abortion revealed a comparable overall incidence between the two treatment groups. The most common TESAEs with a reasonable possibility of a causal relationship with the study drugs were vaginal hemorrhage (1.2 and 1.4% of subjects, respectively), hepatic function abnormal (1.0 and 0.4% of subjects, respectively) and vaginal discharge (1.0 and 0.0% of subjects, respectively). Overall, the safety and tolerability data were generally similar between the treatment groups.

The proportion of fetuses/newborns with at least one TESAE was 12.7% in the oral dydrogesterone group and 11.4% in the MVP gel group. The incidence of TEAEs of special interest (congenital, familial, and genetic disorders) was low and comparable between treatment groups (6.3 and 5.0% in the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups, respectively); of these, the most common was atrial septal defects (2.3 and 3.5% in the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups, respectively) (Table III). Overall, the incidence of fetuses/newborns with congenital heart malformations was low in both treatment groups: 2.7% (6/221) and 5.0% (10/201) in the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups, respectively (five fetuses/newborns had more than one anomaly; two in the oral dydrogesterone group and three in the MVP gel group).

In most cases in both treatment groups, no abnormal findings were found from the physical examination of newborns at delivery (92.2 and 93.5% of newborns in the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups, respectively). The mean ±SD weight of newborns was similar in the two treatment groups (2.9 ± 0.7 kg and 3.0 ± 0.7 kg in the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups, respectively). Height, head circumference and APGAR score were comparable between the treatment groups (Table IV).

Table IV.

Newborn characteristics (FAS).

| Oral DYD (N = 494) | MVP Gel (N = 489) | |

|---|---|---|

| Newborns, n | 205 | 188 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 105 (51.2) | 95 (50.5) |

| Female | 100 (48.8) | 93 (49.5) |

| Abnormal findings of physical examination, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 16 (7.8) | 12 (6.5) |

| No | 188 (92.2) | 173 (93.5) |

| Missing | 1 | 3 |

| Height, cm (mean ± SD) | 48.8 ± 4.0 | 48.8 ± 3.9 |

| Weight, kg (mean ± SD) | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 3.0 ± 0.7 |

| Head circumference, cm (mean ± SD) | 33.6 ± 2.5 | 33.9 ± 2.6 |

| APGAR score (mean ± SD) | ||

| 1 min postpartal | 8.7 ± 1.2 | 8.5 ± 1.4 |

| 5 min postpartal | 9.3 ± 1.1 | 9.3 ± 0.9 |

APGAR, appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, and respiration; DYD, dydrogesterone; FAS, full analysis sample; MVP, micronized vaginal progesterone; SD, standard deviation.

Discussion

The Lotus II study demonstrated that oral dydrogesterone was non-inferior to MVP gel for luteal phase support in fresh-cycle IVF. Analysis of the primary endpoint (presence of a fetal heartbeat at 12 weeks of gestation) and secondary endpoints (pregnancy rates at 4 and 8 weeks of gestation, live birth rates and number of healthy newborns) showed that results were comparable between the treatment groups. Although miscarriage rates were not investigated as a direct endpoint of the study, similar decreases in pregnancy rates between 4 and 12 weeks of gestation were observed in the two treatment groups, suggesting comparable miscarriage rates. Overall, these findings were consistent with the results of the Lotus I study, which demonstrated that oral dydrogesterone was non-inferior to MVP capsules in terms of pregnancy rates at 12 weeks of gestation following luteal phase support (Tournaye et al., 2017). The results from Lotus I and Lotus II, a substantial study program in IVF, demonstrate that oral dydrogesterone is a viable alternative to two of the main types of MVP (gel or capsules) for luteal phase support.

Lotus I and Lotus II also demonstrated that oral dydrogesterone and MVP had comparable safety and tolerability profiles. Of note, the overall incidence of abortion-related TEAEs between the two treatment groups were comparable. Furthermore, the incidence of congenital, familial and genetic disorders from Lotus II (6.3 and 5.0% in the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups, respectively) was comparable to that from an analysis of 308 974 births (Davies et al., 2012). Importantly, the percentage of fetuses/newborns with congenital heart malformations was 2.7% (6/221) and 5.0% (10/201) in the oral dydrogesterone and MVP gel groups, respectively. Although a previous retrospective case-controlled study reported a positive association between congenital heart malformations and dydrogesterone (Zaqout et al., 2015), the study did not implement key principles to reduce selection, confounding and information bias; therefore, no evidence of a causal relationship can be concluded from the analysis.

Overall, the robust Lotus I and Lotus II studies identified no new safety concerns associated with using oral dydrogesterone, and no link to congenital malformations could be identified. However, investigating the long-term safety of progestogen formulations for luteal phase support will be an important area of future research. While Lotus I and Lotus II assessed the tolerability of oral dydrogesterone and MVP capsules and gel through documentation of TEAEs, these studies were not designed to investigate patient preferences for each treatment. However, it has been well documented that oral administration is preferred by patients over intravaginal application (Bingham, 1984; Arvidsson et al., 2005; Chakravarty et al., 2005).

Although both Lotus studies were methodologically robust, the authors acknowledge some limitations. Lotus II had an open-label study design; it was not possible to perform a double-blind and double-dummy study because it was not technically feasible to make a placebo applicator for MVP gel. The open-label study design increased the risk of bias for subjective endpoints, which could potentially influence the collection of tolerability data. For example, patients may report known side effects, and if subjective tolerability questions were not asked systematically to all patients, bias could be introduced. However, there can be little to no bias expected for the objective endpoints evaluated in this study, such as pregnancy rates at 12 weeks of gestation as determined by a transvaginal ultrasound, live birth rates or analyses of liver enzymes.

Another potential limitation of the study could include the 10-week treatment period of the Lotus program, which was based on the dosing schedule for MVP capsules (Utrogestan®; Besins Healthcare, Belgium): the comparator used in Lotus I (Tournaye et al., 2017). However, while there is evidence to suggest that a shorter duration of treatment is effective (Kohls et al., 2012), the optimal dosing schedule and period of luteal phase support with progestogens remains to be established (Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, 2008). Finally, subjects with more than three unsuccessful IVF attempts and those with recurrent pregnancy loss were excluded from the study, due to the low pregnancy rates in these populations and the subsequent need for further stratification of the results.

The large sample size and the multicenter study design of Lotus II positively impacts on the generalizability of the results. However, as in all clinical trials in selected patient populations, generalizability of the findings may be limited by patient factors. For example, it has been established that increasing body mass index and increasing age are associated with decreased clinical pregnancy rates from IVF (Sneed et al., 2008), and are factors that could affect generalizability. In this study, it is important to note that subjects were included if they had a body mass index within the range of ≥18 to ≤30 kg/m2, and 70.4% of included subjects were <35 years of age.

While the results from Lotus I, Lotus II and several smaller clinical studies demonstrate the efficacy of oral dydrogesterone for luteal phase support in fresh-cycle IVF (Chakravarty et al., 2005; Patki and Pawar, 2007; Ganesh et al., 2011; Salehpour et al., 2013; Tomic et al., 2015; Saharkhiz et al., 2016; Zargar et al., 2016; Tournaye et al., 2017), limited data are available about its use in programmed frozen-thawed cycles. In contrast to fresh cycles, the absence of corpora lutea in programmed frozen-thawed cycles means that the endometrium is totally dependent on exogenous progestogen supplementation (Ghobara et al., 2017). Although two small randomized clinical studies have investigated the use of oral dydrogesterone for luteal phase support in programmed frozen-thawed cycles (Rashidi et al., 2016; Zarei et al., 2017), further studies are needed to establish the efficacy of oral dydrogesterone in this setting.

Overall, the results from Lotus I and Lotus II demonstrate that oral dydrogesterone is as efficacious as MVP (capsules or gel) for luteal phase support in fresh-cycle IVF, with a similar safety profile within the studies. Therefore, because of its patient-friendly oral administration route, dydrogesterone has the potential to induce a paradigm shift for luteal phase support in the estimated 1.5 million women undergoing IVF each year (Chambers et al., 2012).

Acknowledgements

Abbott study support: Erik van Leeuwen. Editorial support: Josh Lilly of Alpharmaxim Healthcare Communications, funded by Abbott Established Pharmaceuticals. We would like to thank the following study investigators from their respective countries. Australia: Christos Venetis (Sydney), Hossam Elzeiny (Melbourne); Belgium: Christine Wyns (Brussels), Wim Decleer (Ghent), Petra De Sutter (Gent); China: Wei Wang (Nanjing), Fei Gong (Changsha), Xiaoyan Liang (Guangzhou), Hanwang Zhang (Wuhan), Yingpu Sun (Zhengzhou); Germany: Anette Siemann (Berlin), Stefan Dieterle (Dortmund), Paul Ebert (Bielefeld); Hong Kong: Ernest Ng (Hong Kong); India: Gita Khanna (Lucknow), Chitra Ramamurthy (Bangalore), Kamini Rao (Bangalore), Alka Kriplani (New Delhi), Amit Shah (Pune), Payal Chobe (Aurangabad), Sonia Malik (Gurgaon); Russia: Igor Baranov (Moscow), Tatiana Gurskaya (Moscow), Irina Dankova (Ekaterinburg), Nina Tatarova (Saint-Petersburg), Vere Prilepskaya (Moscow); Singapore: Su Ling Yu (Singapore); Thailand: Chatpavit Getpook (Hat Yai), Usanee Sanmee (Muang); Ukraine: Vira Sirenko (Kiev), Valery Zukin (Kiev), Alexander Yuzki (Chernivtsi), Nataliya Dankovich (Kiev).

Authors’ roles

G.G.: Lead investigator for Germany; analysis of data, review and comments on article outline and multiple versions. C.B.: Lead recruiter for Belgium; analysis of data, review and comments on article outline and multiple versions. G.S.: Lead investigator for Russia; analysis of data, review and comments on article outline and multiple versions. A.P.: Member of advisory board to determine the Lotus program, lead advisor for India; analysis of data, review and comments on article outline and multiple versions. B.D.: Lead recruiter for India; analysis of data, review and comments on article outline and multiple versions. D.-Z.Y.: Lead investigator for China; analysis of data, review and comments on article outline and multiple versions. Z.-J.C.: Lead advisor for China; analysis of data, review and comments on article outline and multiple versions. E.K.: Involvement in development of Lotus program; statistical analysis of data, review and comments on manuscript outline and multiple versions. C.P.-F.: Involvement in development of Lotus program; analysis of data, review and comments on article outline and multiple versions. H.T.: Lead investigator for Belgium; analysis of data, review and comments on article outline and multiple versions. All authors approved the final version of the article and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This study was sponsored and supported by Abbott Established Pharmaceuticals.

Conflict of interest

G.G. has received investigator fees from Abbott during the conduct of the study. Outside of this submitted work, G.G. has received non-financial support from MSD, Ferring, Merck-Serono, IBSA, Finox, TEVA, Glycotope and Gedeon Richter, as well as personal fees from MSD, Ferring, Merck-Serono, IBSA, Finox, TEVA, Glycotope, VitroLife, NMC Healthcare, ReprodWissen, Biosilu, Gedeon Richter and ZIVA. C.B. is the President of the Belgian Society of Reproductive Medicine (unpaid) and Section Editor of Reproductive BioMedicine Online. C.B. has received grants from Ferring Pharmaceuticals, participated in an MSD sponsored trial, and has received payment from Ferring, MSD, Biomérieux, Abbott and Merck for lectures. G.S. has no conflicts of interest to be declared. A.P. is the General Secretary of the Indian Society of Assisted Reproduction (2017–2018). B.D. is President of Pune Obstetric and Gynecological Society (2017–2018). D.-Z.Y. has no conflicts of interest to be declared. Z.-J.C. has no conflicts of interest to be declared. E.K. is an employee of Abbott Laboratories GmbH, Hannover, Germany and owns shares in Abbott. C.P.-F. is an employee of Abbott GmbH & Co. KG, Wiesbaden, Germany and owns shares in Abbott. H.T.’s institution has received grants from Merck, MSD, Goodlife, Cook, Roche, Origio, Besins, Ferring and Mithra (now Allergan); and H.T. has received consultancy fees from Finox-Gedeon Richter, Merck, Ferring, Abbott and ObsEva.

References

- Arvidsson C, Hellborg M, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Preference and acceptability of oral versus vaginal administration of misoprostol in medical abortion with mifepristone. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2005;123:87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa MW, Silva LR, Navarro PA, Ferriani RA, Nastri CO, Martins WP. Dydrogesterone vs progesterone for luteal-phase support: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016;48:161–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltsos AN, Sanchez MD, Doody KJ, Bush MR, Domar AD, Collins MG. Patients’ administration preferences: progesterone vaginal insert (Endometrin®) compared to intramuscular progesterone for luteal phase support. Reprod Health 2014;11:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besins Healthcare (UK) Ltd Utrogestan 100 mg capsules Summary of Product Characteristics, 14 July 2017.

- Bingham JS. Single blind comparison of ketoconazole 200 mg oral tablets and clotrimazole 100 mg vaginal tablets and 1% cream in treating acute vaginal candidosis. Br J Vener Dis 1984;60:175–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarty BN, Shirazee HH, Dam P, Goswami SK, Chatterjee R, Ghosh S. Oral dydrogesterone versus intravaginal micronised progesterone as luteal phase support in assisted reproductive technology (ART) cycles: results of a randomised study. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2005;97:416–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers GM, Hoang VP, Zhu R, Illingworth PJ. A reduction in public funding for fertility treatment—an econometric analysis of access to treatment and savings to government. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies MJ, Moore VM, Willson KJ, Van Essen P, Priest K, Scott H, Haan EA, Chan A. Reproductive technologies and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1803–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doody KJ, Schnell VL, Foulk RA, Miller CE, Kolb BA, Blake EJ, Yankov VI. Endometrin for luteal phase support in a randomized, controlled, open-label, prospective in-vitro fertilization trial using a combination of Menopur and Bravelle for controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. Fertil Steril 2009;91:1012–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi HM, Bourgain C, Donoso P, Blockeel C, Papanikolaou EG, Popovic-Todorovic B, Devroey P. Effect of oral administration of dydrogestrone versus vaginal administration of natural micronized progesterone on the secretory transformation of endometrium and luteal endocrine profile in patients with premature ovarian failure: a proof of concept. Hum Reprod 2007;22:1260–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh A, Chakravorty N, Mukherjee R, Goswami S, Chaudhury K, Chakravarty B. Comparison of oral dydrogestrone with progesterone gel and micronized progesterone for luteal support in 1,373 women undergoing in vitro fertilization: a randomized clinical study. Fertil Steril 2011;95:1961–1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghobara T, Gelbaya TA, Ayeleke RO. Cycle regimens for frozen-thawed embryo transfer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;7:CD003414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinstein J, Luteal Phase Study Group . Efficacy and tolerability of vaginal progesterone capsules (Utrogest 200) compared with progesterone gel (Crinone 8%) for luteal phase support during assisted reproduction. Fertil Steril 2005;83:1641–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohls G, Ruiz F, Martinez M, Hauzman E, de la Fuente G, Pellicer A, Garcia-Velasco JA. Early progesterone cessation after in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a randomized, controlled trial. Fertil Steril 2012;98:858–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood G, Griesinger G, Cometti B, European Centers . Subcutaneous progesterone versus vaginal progesterone gel for luteal phase support in in vitro fertilization: a noninferiority randomized controlled study. Fertil Steril 2014;101:112–119.e113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macklon NS, Fauser BC. Impact of ovarian hyperstimulation on the luteal phase. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 2000;55:101–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza FG, Patki A, Pexman-Fieth C. Dydrogesterone use in early pregnancy. Gynecol Endocrinol 2016;32:97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patki A, Pawar VC. Modulating fertility outcome in assisted reproductive technologies by the use of dydrogesterone. Gynecol Endocrinol 2007;23:68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine Progesterone supplementation during the luteal phase and in early pregnancy in the treatment of infertility: an educational bulletin. Fertil Steril 2008;89:789–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashidi BH, Ghazizadeh M, Tehrani Nejad ES, Bagheri M, Gorginzadeh M. Oral dydrogesterone for luteal support in frozen-thawed embryo transfer artificial cycles: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Asian Pac J Reprod 2016;5:490–494. [Google Scholar]

- Rižner TL, Brožič P, Doucette C, Turek-Etienne T, Muller-Vieira U, Sonneveld E, van der Burg B, Bocker C, Husen B. Selectivity and potency of the retroprogesterone dydrogesterone in vitro. Steroids 2011;76:607–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saharkhiz N, Zamaniyan M, Salehpour S, Zadehmodarres S, Hoseini S, Cheraghi L, Seif S, Baheiraei N. A comparative study of dydrogesterone and micronized progesterone for luteal phase support during in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles. Gynecol Endocrinol 2016;32:213–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehpour S, Tamimi M, Saharkhiz N. Comparison of oral dydrogesterone with suppository vaginal progesterone for luteal-phase support in in vitro fertilization (IVF): a randomized clinical trial. Iran J Reprod Med 2013;11:913–918. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sator M, Radicioni M, Cometti B, Loprete L, Leuratti C, Schmidl D, Garhofer G. Pharmacokinetics and safety profile of a novel progesterone aqueous formulation administered by the s.c. route. Gynecol Endocrinol 2013;29:205–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon JA, Robinson DE, Andrews MC, Hildebrand JR III, Rocci ML Jr, Blake RE, Hodgen GD. The absorption of oral micronized progesterone: the effect of food, dose proportionality, and comparison with intramuscular progesterone. Fertil Steril 1993;60:26–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simunic V, Tomic V, Tomic J, Nizic D. Comparative study of the efficacy and tolerability of two vaginal progesterone formulations, Crinone 8% gel and Utrogestan capsules, used for luteal support. Fertil Steril 2007;87:83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneed ML, Uhler ML, Grotjan HE, Rapisarda JJ, Lederer KJ, Beltsos AN. Body mass index: impact on IVF success appears age-related. Hum Reprod 2008;23:1835–1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavaniotou A, Smitz J, Bourgain C, Devroey P. Comparison between different routes of progesterone administration as luteal phase support in infertility treatments. Hum Reprod Update 2000;6:139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomic V, Tomic J, Klaic DZ, Kasum M, Kuna K. Oral dydrogesterone versus vaginal progesterone gel in the luteal phase support: randomized controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2015;186:49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tournaye H, Sukhikh GT, Kahler E, Griesinger G. A phase III randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy, safety and tolerability of oral dydrogesterone versus micronized vaginal progesterone for luteal support in in vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod 2017;32:1019–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaisbuch E, Leong M, Shoham Z. Progesterone support in IVF: is evidence-based medicine translated to clinical practice? A worldwide web-based survey. Reprod Biomed Online 2012;25:139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Linden M, Buckingham K, Farquhar C, Kremer JA, Metwally M. Luteal phase support for assisted reproduction cycles. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;10:CD009154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Linden M, Buckingham K, Farquhar C, Kremer JA, Metwally M. Luteal phase support for assisted reproduction cycles. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;7:CD009154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaqout M, Aslem E, Abuqamar M, Abughazza O, Panzer J, De Wolf D. The impact of oral intake of dydrogesterone on fetal heart development during early pregnancy. Pediatr Cardiol 2015;36:1483–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarei A, Sohail P, Parsanezhad ME, Alborzi S, Samsami A, Azizi M. Comparison of four protocols for luteal phase support in frozen-thawed Embryo transfer cycles: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2017;295:239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zargar M, Saadati N, Ejtahed MS. Comparison the effectiveness of oral dydrogesterone, vaginal progesterone suppository and progesterone ampule for luteal phase support on pregnancy rate during ART cycles. Int J Pharm Res Allied Sci 2016;5:229–236. [Google Scholar]