Abstract

Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) is an infrequent neurological complication of dengue viral infection. It is broadly divided into either acute inflammatory demyelinating variety or an axonal variety (acute motor axonal and acute sensory and motor axonal variants). Axonal variants are distinctly infrequent. Two brothers (18 years and 15 years) were hospitalized on the same day with complaints of acute symmetric upper- and lower-limb weakness of 7 days' duration. They did not have overt manifestations of dengue fever which preceded the neurological presentation. They had flaccid areflexic pure motor quadriparesis. Dengue IgM serology was positive in both. Nerve conduction study showed predominant axonopathic changes in both the patients. Both the patients showed significant improvement with conservative treatment during hospital stay of 7 days. This is unusual report of dengue-associated axonal GBS in two brothers. Whether simultaneous occurrence of GBS in two siblings is a coincidence or genetically determined is still a question.

Keywords: Autoimmune, dengue virus, genetic susceptibility, Guillain–Barré syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Recently, there is global change in the clinical profile of dengue infection, and increasing number of patients are now presenting with neurological manifestations. Neurological complications associated with dengue infection vary from 0.5% to 21% in different series.[1,2,3,4] Both peripheral and central nervous system are likely to be affected following dengue infection. Up to 4% of dengue-infected patients develop some form of neuromuscular complications.[5] Peripheral nervous system involvement is usually seen in form of plexus involvement, mononeuropathies, generalized neuopathies, myositis, hypokalemic paralysis, and rarely neuromuscular disoders.

During an epidemic, Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) is a frequently encountered neuromuscular dengue-associated complication. It usually follows dengue infection by 7–10 days. Majority of time, dengue-associated GBS is demyelinating type. We are reporting an unusual report of two brothers developing GBS simultaneously due to dengue viral infection. This rare presentation becomes important in hypothesizing the role of genetic predisposition in the development of neurological complication due to dengue infection.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

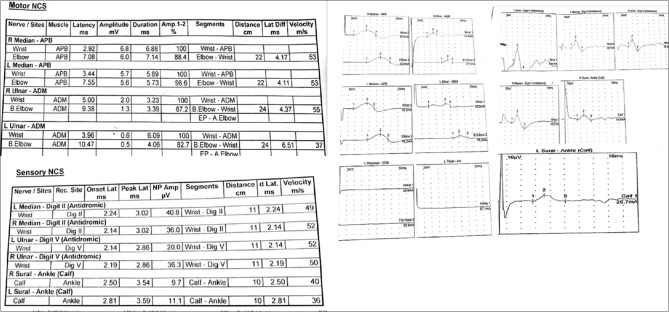

An 18-year-old man presented with weakness involving both upper and lower limbs of 1-week duration. The weakness initially started off as heaviness in both the feet, and the patient developed significant degree of weakness over the next 4 days, leading to a bed-bound state. Sensations of the limbs were normal, and he was continent. General physical examination was unremarkable, and single breath count was thirty with no evidence of orthostatic hypotension. He was conscious and alert, and cranial nerves were normal. Muscle power was 2/5 (Medical Research Council grading for muscle strength) in proximal muscles of both upper and lower limbs and 1/5 in distal muscles along with hypotonia and generalized areflexia. Sensory examination was normal. Plantar reflex was flexor. There was history of mild fatigue few days before the development of weakness. Routine investigations including hemogram, biochemistry, and serum electrolytes were normal. Hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays were nonreactive. Urine for porphobilinogen was negative. Serum antinuclear antibody was negative. Nerve conduction study revealed reduced compound muscle action potential (CMAP) in the left median and bilateral ulnar nerves, whereas tibial and peroneal nerve conductions were nonrecordable in both the lower limbs. Sensory nerve action potentials (SNAPs) were preserved in both upper and lower limbs [Figure 1]. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination done at day 7 of illness was normal: cells <5 cumm, protein 36.4 mg/dl, and sugar 62.1 mg/dl. Dengue serology was positive.

Figure 1.

Nerve conduction study of Case 1

CSF polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for dengue was negative.

Case 2

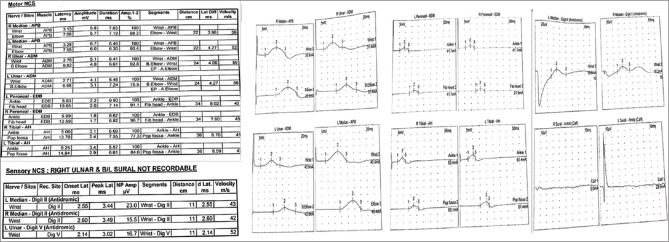

A 15-year-old boy brother of the first case also developed acute-onset weakness of both upper and lower limbs at around the same time his brother developed it. He had lesser degree of involvement and could walk. Examination revealed 4/5 power in both upper and lower limbs along with hypotonia and generalized areflexia. Sensations were completely normal. General physical and systemic examination was unremarkable. Plantar reflex was flexor. There was no history of fever, respiratory or abdominal infections in the recent past, joint pain, rashes, recent vaccination, or exposure to toxins. Hemogram, liver function test, and kidney function tests were normal. Serum electrolytes were normal. Hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays were nonreactive. Urine for porphobilinogen and serum antinuclear antibody was negative. Nerve conduction study revealed reduced CMAP in the right median and bilateral ulnar nerves with normal distal latency and conduction velocity, reduced CMAP in both tibial and peroneal nerves with prolonged distal latency, and reduced conduction velocities. SNAP in bilateral median and left ulnar nerve was reduced with normal distal latency and reduced conduction velocity. SNAP in the right ulnar and bilateral sural nerves were nonrecordable [Figure 2]. CSF examination revealed cells <5/cumm, protein 35.9 mg/dl, and sugar 58.7 mg/dl. Dengue IgM serology was positive, and CSF PCR for dengue virus was negative. Both patients were treated with a 5-day course of methylprednisolone. Younger brother improved completely over the next 5 days, whereas the other one could walk with minimal support after 2 weeks.

Figure 2.

Nerve conduction study of Case 2

DISCUSSION

GBS is a complex multifactorial disorder, and both genetic and environmental factors play role in pathogenesis. Familial cases of GBS, although rare, have been described in some studies with demonstration of common human leukocyte antigen allele in affected family members.[6] There are three important issues associated with this report. First, was occurrence of dengue-associated GBS just a coincidence or genetically determined? Second, both brothers had relatively infrequent axonal variants of GBS. Third, both patients had oligosymptomatic dengue infection.

Many cases of GBS following dengue viral infection have been described.[7,8,9,10] The neuropathogenesis of dengue virus causing GBS is not completely understood. The autoimmune reaction against self-antigens is one of the hypotheses.[11] An interplay between the microbial antigens and host factors is considered responsible for the pathogenesis of GBS. An interaction between genetic and environmental factors is responsible for individual's susceptibility to GBS following an infection. Molecular mimicry of microbial antigens leads to production of cross-reactive antibodies; these cross-reactive antibodies target nerve elements such as gangliosides and subsequent inflammatory changes lead to nerve damage.[12] We think that simultaneous occurrence of dengue-associated GBS further suggests a role of genetic susceptibility of dengue-associated GBS. Majority of dengue-associated GBS are of demyelinating variety. The axonal subtypes of GBS such as acute motor axonal neuropathy and acute motor and sensory axonal neuropathy are infrequently reported. Axonal variants are caused by antibody-mediated attack due to molecular mimicry between microbial antigen and axonal surface molecule, and there is damage to axons.[13] We hypothesize that predominant axonal damage following an infection is also genetically determined. Our patients also presented with axonal variant of GBS. An important observation was made that both the brothers did not had any overt manifestation of dengue fever preceding GBS. Characteristic changes in blood, such as thrombocytopenia, were also absent. Serum IgM for dengue was positive in both the patients which is highly suggestive of dengue infection. Our patients presented 7 days after onset of disease and that could be one possible explanation for negative CSF PCR for dengue. WHO classification (2009) lacks addressing the dengue-associated neurological manifestations well and our cases do qualify the criteria for proposed definition of neurological features of dengue.[14] Soares et al. observed several cases of GBS following an oligosymptomatic dengue infection. Six out of seven patients in his series did not have history suggesting dengue infection.[15] GBS following oligosymptomatic dengue infection suggests that, during an epidemic, even asymptomatic infection with dengue can produce significant degree of immunological response leading to devastating neurological complications. Soares et al. cautioned that a high index of suspicion should be maintained for early diagnosis. It seems that both viral and host factors play a significant role in pathogenesis of neurological complication in asymptomatic or oligosymptomatic dengue virus-infected individuals.

CONCLUSION

Dengue-associated neurological complications can be there even in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic individuals, and genetic factors do play role in its pathogenesis.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Solomon T, Dung NM, Vaughn DW, Kneen R, Thao LT, Raengsakulrach B, et al. Neurological manifestations of dengue infection. Lancet. 2000;355:1053–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Domingues RB, Kuster GW, Onuki-Castro FL, Souza VA, Levi JE, Pannuti CS, et al. Involvement of the central nervous system in patients with dengue virus infection. J Neurol Sci. 2008;267:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pancharoen C, Thisyakorn U. Neurological manifestations in dengue patients. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2001;32:341–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thisyakorn U, Thisyakorn C, Limpitikul W, Nisalak A. Dengue infection with central nervous system manifestations. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1999;30:504–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garg RK, Malhotra HS, Jain A, Malhotra KP. Dengue-associated neuromuscular complications. Neurol India. 2015;63:497–516. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.161990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Senanayake MP, Wanigasinghe J, Gamaethige N, Dissanayake P. A case of possible familial Guillain-Barre syndrome. Ceylon Med J. 2010;55:135–6. doi: 10.4038/cmj.v55i4.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonçalves E. Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (Guillain-Barré syndrome) following dengue fever. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2011;53:223–5. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652011000400009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santos NQ, Azoubel AC, Lopes AA, Costa G, Bacellar A. Guillain-Barré syndrome in the course of dengue: Case report. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2004;62:144–6. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2004000100025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esack A, Teelucksingh S, Singh N. The Guillain-Barré syndrome following dengue fever. West Indian Med J. 1999;48:36–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verma R, Sharma P, Garg RK, Atam V, Singh MK, Mehrotra HS, et al. Neurological complications of dengue fever: Experience from a tertiary center of North India. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2011;14:272–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.91946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes RA, Hadden RD, Gregson NA, Smith KJ. Pathogenesis of Guillain-Barré Syndrome. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;100:74–97. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wijdicks EF, Klein CJ. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:467–79. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodfellow JA, Willison HJ. Guillain-Barré syndrome: A century of progress. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:723–31. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carod-Artal FJ, Wichmann O, Farrar J, Gascón J. Neurological complications of dengue virus infection. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:906–19. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soares CN, Cabral-Castro M, Oliveira C, Faria LC, Peralta JM, Freitas MR, et al. Oligosymptomatic dengue infection: A potential cause of Guillain Barré syndrome. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2008;66:234–7. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2008000200018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]