The anticancer activity of CW3, an irreversible allosteric inhibitor of the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ube2g2, and its interaction with the protein.

The anticancer activity of CW3, an irreversible allosteric inhibitor of the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ube2g2, and its interaction with the protein.

Abstract

The RING finger-dependent ubiquitin ligase (E3) gp78, known as the tumor autocrine motility factor receptor, contributes to tumor progression. The protein interacts with its cognate ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2), Ube2g2, via its RING domain and a unique region called G2BR that strongly binds to E2. The binding of G2BR to Ube2g2 allosterically enhances the binding of RING to E2, and the binding of RING triggers the departure of G2BR from E2 also in an allosteric fashion. Targeting these allosteric events, we developed a family of inhibitors that irreversibly block E2–E3 interactions and thereby eliminate the tumorigenic effect of gp78. One among 19 compounds screened with the NCI 60 tumor cell lines exhibited outstanding anticancer activities. At 10 μM, it caused >50% growth inhibition to 40% of the cell lines; at 100 μM, it showed lethiferous activity against most cell lines.

1. Introduction

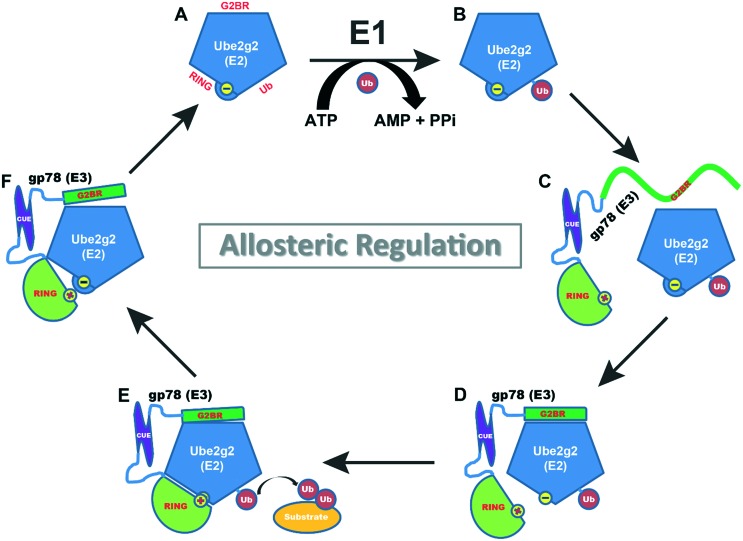

Ubiquitination, the reaction of ubiquitin (Ub) conjugation to a substrate, is catalyzed by Ub-activating E1, Ub-conjugating E2, and Ub-ligating E3 enzymes. In an ATP-dependent manner, E1 activates Ub and transfers the activated Ub to E2; then, E2 interacts with E3 to conjugate Ub onto the substrate (Fig. 1). In the human genome, two E1, ∼40 E2, and >600 E3 enzymes have been identified.1 In cancer, the Ub conjugation pathway is frequently perturbed; therefore, modulating the activities of E1, E2, and E3 is of intense interest for the development of anticancer agents.2 However, ubiquitination depends on the dynamic rearrangement of multiple protein–protein interactions that are traditionally difficult to target with small molecules.3 So far, several E1 or E3 inhibitors have entered clinical trials, but only one E2 inhibitor has been under preclinical studies.4,5 More E2 inhibitors are needed because E2 plays a critical role, deciding between life and death of proteins.6 Here, we present a new family of inhibitors targeting Ube2g2, the specific E2 of gp78, an E3 enzyme known as the tumor autocrine motility factor receptor.7 This E2–E3 pair is critically important for the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated degradation of multiple substrates,8 including kangai1 (KAI1) which suppresses tumor progression.9,10

Fig. 1. Allosteric regulation of a processive ubiquitination machine. Comparative analysis of the crystal structures of ligand-free Ube2g2 (PDB entry 2CYX), Ube2g2 in complex with the G2BR of gp78 (PDB entry ; 3H8K), and Ube2g2 in complex with both the G2BR and RING of gp78 (PDB entry ; 4LAD) reveals allosteric regulation events along the functional cycle of Ube2g2.14 (A) Schematic representation of the E2 enzyme Ube2g2 with the G2BR-binding, RING-binding, and Ub-conjugating sites indicated. The minus sign indicates the hidden carboxyl group of the Glu108 side chain. It forms a salt bridge with the Arg379 guanidinium group of RING. (B) In an ATP-dependent manner, a Ub molecule is activated by an E1 enzyme and conjugated to Ube2g2. (C) The E3 enzyme gp78 binds to Ube2g2 with the G2BR and RING motifs. G2BR is non-structured before binding to the E2 enzyme. The Arg379 guanidinium group of RING is indicated with a plus sign. (D) Upon binding to Ube2g2, G2BR becomes an α-helix. In an allosteric manner, the binding of G2BR triggers the exposure of the hidden carboxyl group of Glu108. (E) Readily, the Glu108Ube2g2–Arg379gp78 salt bridge forms, and the binding of RING promotes the ligation of Ub to the substrate and the release of G2BR from Ube2g2. (F) The departure of G2BR destroys the salt bridge, promoting the release of RING from Ube2g2. The ligand-free Ube2g2 will be loaded with another Ub for the next ubiquitination cycle.

Containing 643 amino acid residues, gp78 is a transmembrane protein. The transmembrane domains of gp78 (residues 82–296) are followed by the RING domain (residues 313–393), a CUE domain (residues 452–504), and a specific Ube2g2-binding region known as G2BR (residues 574–600).8 The three-dimensional structure of full-length gp78 is not available. Unlike gp78, Ube2g2 has a single-domain structure containing 165 amino acid residues. The crystal structure of Ube2g2 was determined about a decade ago (Protein Data Bank (PDB) entry ; 2CYX).11 Recently, crystal structures of Ube2g2 in complex with G2BR (PDB entries ; 3FSH and ; 3H8K)12,13 and with both RING and G2BR (PDB entry ; 4LAD)14 were determined. Comparative structural and functional analyses revealed three allosteric regulatory events along the functional cycle of Ube2g2 (Fig. 1).14 First, the high-affinity binding of G2BR to Ube2g2 (Kd = 21 nM) induces a conformational change at the RING-binding site of Ube2g2, which triggers the exposure of a hidden Glu side chain that is necessary for enhanced binding of RING to Ube2g2 by forming a salt bridge with an Arg side chain from RING (Fig. 1C and D). Second, the binding of RING to Ube2g2 induces a second allosteric effect, which reduces the buried Ube2g2:G2BR interface from 1950 to 1640 Å2, drops the number of intermolecular interactions between Ube2g2 and G2BR from 35 to 23, including several hydrogen bonds along one side of the G2BR helix, and lowers the affinity between G2BR and Ube2g2 (Kd = 132 nM), leading to the departure of G2BR from Ube2g2 (Fig. 1D and E). Third, the departure of G2BR from Ube2g2 reverses the G2BR-induced conformational change at the Ube2g2:RING interface, which breaks the GluUbe2g2–ArgRING salt bridge, promoting the departure of RING from Ube2g2 (Fig. 1E and F). The ligand-free Ube2g2 is ready for the next functional cycle (Fig. 1A). These findings provide an opportunity for structure-based development of allosteric inhibitors targeting Ube2g2 because the insertion of any small molecule into the allosteric pathway would inhibit gp78–Ube2g2 interactions and thereby prevent the tumorigenic effect of gp78.

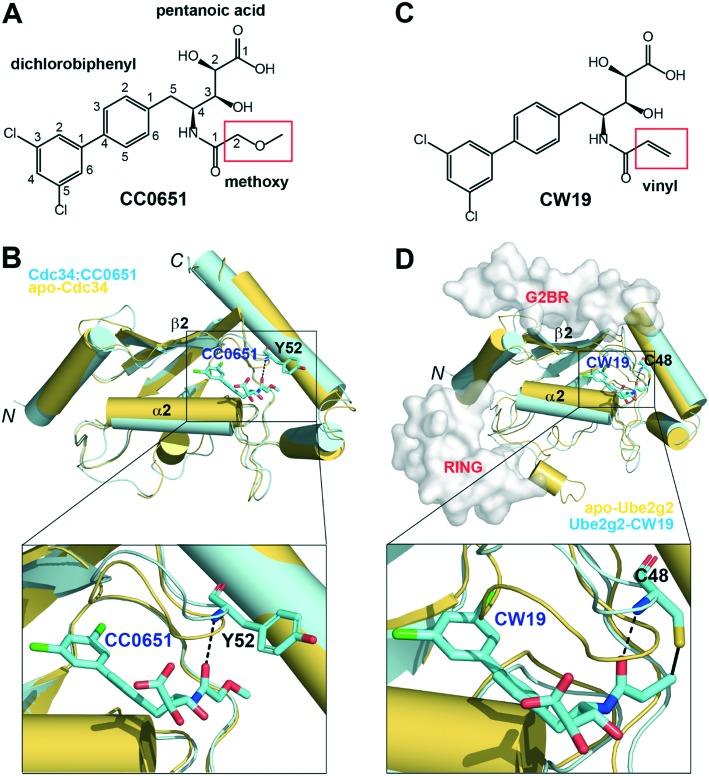

The family of E2 enzymes is characterized by the presence of a highly conserved ubiquitin-conjugating domain.6 Among the ∼40 active E2 enzymes identified in humans is the cell division cycle 34 (Cdc34). Cdc34 is involved in the G1–S phase transition of the eukaryotic cell cycle.15 It catalyzes the ubiquitination of proteins in conjunction with the cullin-RING superfamily of E3 enzymes. Identified from small-molecule screening, the aforementioned E2 inhibitor is an allosteric inhibitor of Cdc34, known as CC0651 (Fig. 2A). It binds to Cdc34 in an induced binding site that does not exist in apo-Cdc34 (Fig. 2B).2 This allosteric inhibitor-binding site is located between the binding sites of G2BR and RING, which prompted us to develop CC0651 derivatives that specifically recognize Ube2g2.

Fig. 2. Design of the irreversible allosteric inhibitor CW19 targeting Ube2g2. (A) CC0651, the allosteric inhibitor for Cdc34.2 (B) Superimposed Cdc34 structures in its ligand-free (apo-Cdc34, PDB entry ; 2OB4) and CC0651-bound (Cdc34:CC0651, PDB entry ; 3RZ3) forms. (C) CW19, the irreversible allosteric inhibitor for Ube2g2 (this work). (D) The Ube2g2–CW19 model, created with the Phyre2 server16 using the Cdc34 structure in the Cdc34:CC0651 complex as a template, is superimposed with the apo-Ube2g2 structure (PDB entry ; 2CYX). In panels B and D, detailed interactions between the protein and inhibitor are highlighted with zoom-in boxes. In panel D, the G2BR-binding and RING-binding sites are indicated with molecular surfaces modelled based on the G2BR and RING motifs in the Ube2g2:RING–G2BR structure (PDB entry ; 4LAD).

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Inhibitor design

A unique feature of the Ube2g2 sequence offers an opportunity for the design of covalent inhibitors. CC0651 contains a methoxy moiety (Fig. 2A). It forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone amide group of Tyr52 of Cdc34 (Fig. 2B). The counterpart of Tyr52 in Cdc34 is a cysteine residue (Cys48) in Ube2g2, which is unique among human E2 sequences.2 To design our first covalent inhibitor that specifically targets Ube2g2, we replaced the methoxy group in CC0651 (Fig. 2A) with a vinyl group, resulting in compound CW19 (Fig. 2C). Like Cdc34, the binding pocket of CW19 does not exist in the apo-Ube2g2 structure. Based on the Cdc34 structure in the Cdc34:CC0651 complex (PDB entry ; 3RZ3),2 we derived a Ube2g2 model using the Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction, and analysis.16 Superpositioning the Ube2g2 model and the CW19 molecule onto the Cdc34 and CC0651 in the Cdc34:CC0651 complex, respectively, a covalent bond is readily feasible between the thiol side chain of Cys48 in Ube2g2 and the ethyl group of CW19 (Fig. 2D). Comparison between the Ube2g2–CW19 model and the apo-Ube2g2 structure visualizes the conformational changes induced by the binding of CW19.

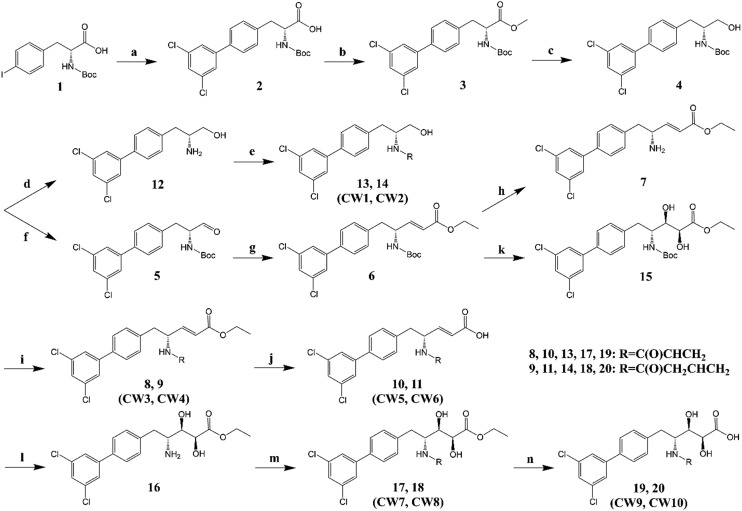

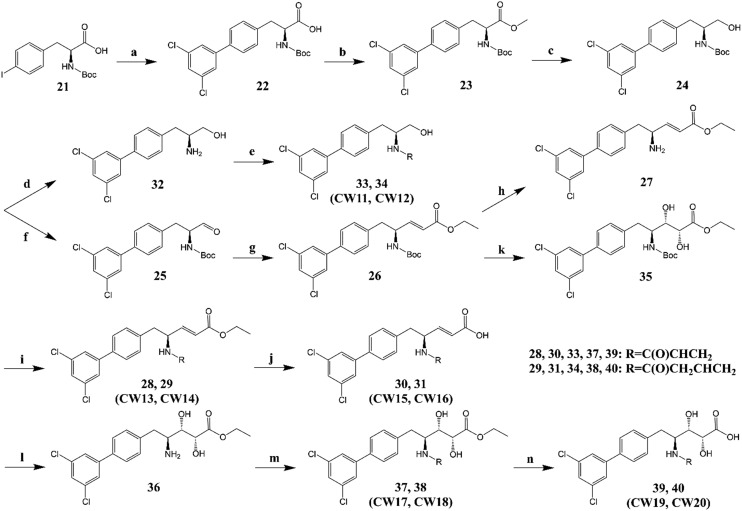

2.2. Chemistry

We synthesized two types of irreversible Ube2g2 inhibitors, D (Scheme 1) and L (Scheme 2). As shown, these two types of inhibitors differ only in the absolute configuration of one chiral center, which is dictated by the starting material (compounds 1 and 21). A total of 20 compounds were synthesized. Herein, we use type D inhibitors (CW1 to CW10) to describe the synthetic route. The non-polar dichlorobiphenyl moiety of CC0651 was conserved in consideration of the inner hydrophobic environment of the allosteric binding pocket (Fig. 2). In contrast, the remaining structure of CC0651 contains multiple single bonds that significantly increase the conformational flexibility of the inhibitors. To ensure the covalent bond formation between the electrophilic moiety of the inhibitor and the thiol group of Cys48, the methoxy group of CC0651 was replaced with not only a vinyl but also an allyl group (Scheme 1). Finally, the discovery of multiple modes of interaction between Cdc34 and the pentanoic acid moiety of the inhibitor (PDB entry ; 3RZ3)2 prompted us to explore the size and rigidity of this scaffold. For example, compounds 13 and 14 (CW1 and CW2) with a much smaller scaffold were synthesized from compound 4 by Boc deprotection followed by PyAOP-mediated acylation of the resulting amine. Also from compound 4, another intermediate compound 6 with a rigid carbon–carbon double bond was synthesized by Dess–Martin oxidation followed by a Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons reaction. Starting from compound 6 and through another intermediate compound 7, compounds 8 and 9 (CW3 and CW4) were synthesized using the same conditions for the synthesis of compounds 13 and 14 (CW1 and CW2). The hydrolysis of compounds 8 and 9 further afforded their respective acid analogs, compounds 10 and 11 (CW5 and CW6). To synthesize compounds 17 and 18 (CW7 and CW8), Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation was employed to introduce the two hydroxyl groups. Then, compounds 17 and 18 were hydrolyzed to give compounds 19 and 20 (CW9 and CW10, Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Chemical synthesis of type D inhibitors (CW1 to CW10). Starting reagent, Boc-4-iodo-d-phenylalanine (1) (5.00 g, 12.78 mmol). (a) 3–5-Dichlorophenylboronic acid, Na2CO3, Pd(PPh3)4, THF/H2O (2 : 1), 70 °C, 48 h, yield 90%; (b) CH3I, NaHCO3, DMF, rt, 12 h, yield 92%; (c) DIBAL, CH2Cl2, rt, 12 h, yield 70%; (d) HCl, EtOH, rt, 6 h, yield 96%; (e) acrylic acid (13) or 3-butenoic acid (14), PyAOP, DIPEA, DMF, rt, 3 h, yield 62% (13, CW1) and 65% (14, CW2), respectively; (f) Dess–Martin periodinane, CH2Cl2, rt, 5 h, yield 97%; (g) triethyl phosphonoacetate, NaH, DMF, 0 °C, 1 h or rt, 2 h, yield 96%; (h) same as d, yield 98%; (i) same as e, yield 52% (8, CW3) and 55% (9, CW4), respectively; (j) NaOH, MeOH/H2O (1 : 1), rt, 12 h, yield 77% (10, CW5) and 80% (11, CW6), respectively; (k) methanesulfonamide, K3Fe(CN)6, OsO4, (DHQD)2PHAL, K2CO3, t-BuOH/H2O (1 : 1), rt, 12 h, yield 65%; (l) same as d, yield 95%; (m) same as e, yield 67% (17, CW7) and 64% (18, CW8), respectively; (n) NaOH, THF/MeOH/H2O (1 : 1 : 1) (19, CW9) or MeOH/H2O (1 : 1) (20, CW10), rt, 12 h, yield 70% (19) and 76% (20), respectively.

Scheme 2. Chemical synthesis of type L inhibitors (CW11 to CW20). Starting reagent, Boc-4-iodo-l-phenylalanine (21) (5.00 g, 12.78 mmol). (a) 3–5-Dichlorophenylboronic acid, Na2CO3, Pd(PPh3)4, THF/H2O (2 : 1), 70 °C, 48 h, yield 98%; (b) CH3I, NaHCO3, DMF, rt, 12 h, yield 96%; (c) DIBAL, CH2Cl2, rt, 12 h, yield 78%; (d) HCl, EtOH, rt 6 h, yield 99%; (e) acrylic acid (33) or 3-butenoic acid (34), PyAOP, DIPEA, DMF, rt, 3 h, yield 70% (33, CW11) and 75% (34, CW12), respectively; (f) Dess–Martin periodinane, CH2Cl2, rt 5 h, yield 90%; (g) triethyl phosphonoacetate, NaH, DMF, 0 °C, 1 h or rt, 2 h, yield 97%; (h) same as d, yield 99%; (i) same as e, yield 59% (28, CW13) and 55% (29, CW14), respectively; (j) NaOH, MeOH/H2O (1 : 1), rt, 12 h, yield 74% (30, CW15) and 80% (31, CW16), respectively; (k) methanesulfonamide, K3Fe(CN)6, OsO4, (DHQD)2PHAL, K2CO3, t-BuOH/H2O (1 : 1), rt, 12 h, yield 67%; (l) same as d, yield 84%; (m) same as e, yield 59% (37, CW17) and 85% (38, CW18), respectively; (n) NaOH, THF/MeOH/H2O (1 : 1 : 1) (39) or MeOH/H2O (1 : 1) (40), rt, 12 h, yield 68% (39, CW19) and 64% (40, CW20), respectively.

2.3. Formation of Ube2g2–inhibitor conjugates

We incubated each of the 20 compounds (CW1–CW20) with Ube2g2 at three pH values. We did not detect any protein–inhibitor conjugates at pH 7.4, found more than three conjugates at pH 9.0, and identified 15 conjugates at pH 8.5 (Table 1). Ube2g2 has three cysteine residues: Cys48, Cys75, and Cys89. The thiol groups of Cys48 and Cys89 are readily accessible from the solvent, whereas those of Cys76 appear to be less accessible to the inhibitors. However, the identification of three Ube2g2–CW11 conjugate species, corresponding to Ube2g2 with 1, 2, or 3 modified cysteine side chains (Table 1), demonstrates that all three cysteine side chains can be modified by the irreversible allosteric inhibitors.

Table 1. The Ube2g2–inhibitor conjugation products at pH 8.5.

| Compound number a | Inhibitor name | Molecular weight (Da) | Molecular weight of detected Ube2g2 b –inhibitor conjugate (Da) |

| 13 | CW1 | 350 | 18 840, 19 190 |

| 14 | CW2 | 364 | None |

| 8 | CW3 | 418 | 18 908 |

| 9 | CW4 | 432 | None |

| 10 | CW5 | 390 | 18 880 |

| 11 | CW6 | 404 | None |

| 17 | CW7 | 452 | 18 942 |

| 18 | CW8 | 466 | None |

| 19 | CW9 | 424 | 18 914, 19 338 |

| 20 | CW10 | 438 | None |

| 33 | CW11 | 350 | 18 840, 19 190, 19 540 |

| 34 | CW12 | 364 | None |

| 28 | CW13 | 418 | 18 908 |

| 29 | CW14 | 432 | None |

| 25 | CW15 | 390 | 18 880, 19 270 |

| 26 | CW16 | 404 | 18 894 |

| 37 | CW17 | 452 | 18 942 |

| 38 | CW18 | 466 | None |

| 39 | CW19 | 424 | None |

| 40 | CW20 | 438 | None |

aAs shown in Scheme 1 and Fig. S1.

bThe molecular weight of our Ube2g2 (from cloning, the first amino acid residue is a glycine instead of methionine) is 18 491 Da.

2.4. Anticancer activity

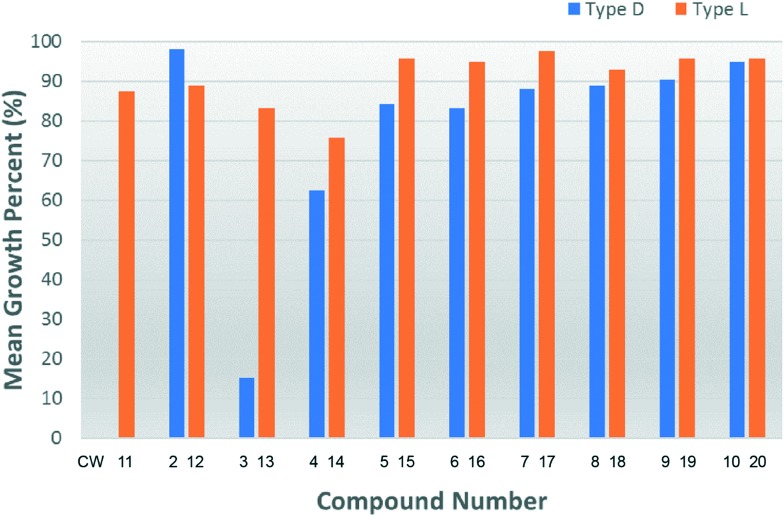

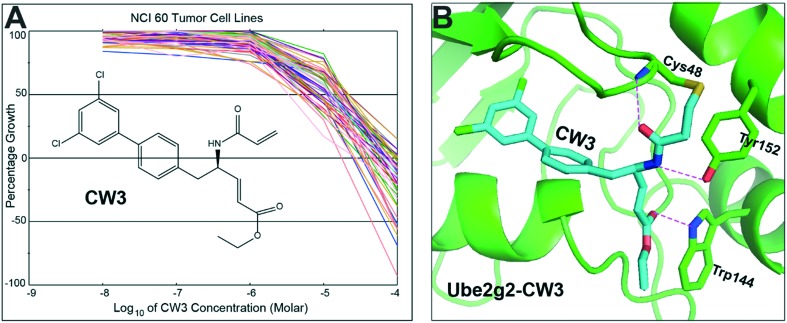

Against the NCI 60 tumor cell panel, we evaluated the cytotoxic activities of these irreversible Ube2g2 inhibitors. We submitted 19 inhibitors (CW2–CW20) for one-dose (10 μM) screening. The results are presented in Fig. 3 and the data are summarised in Table S1.† Among the 19 compounds, CW3 exhibited the highest inhibitory activity against tumor cell growth. In addition, it also showed lethiferous activity against several tumor cell lines (Table S1†). Further, CW3 was tested for dose response effects at five concentrations (0.01, 0.1, 1.0, 10, and 100 μM). As shown in Fig. 4A, the dose dependence of CW3 is clear. At 10 μM, it caused >50% growth inhibition to 40% of the cell lines; at 100 μM, it showed lethiferous activity against most cell lines (Table S2†). The dose dependence for individual cell lines, grouped according to cancer types, is shown in Fig. S1,† showing that CW3 has the highest lethiferous activity against melanoma cancer cells. Recently, a preclinical model system has suggested that gp78 is a tumor suppressor in human liver.17 The NCI 60 tumor cell panel does not contain liver cancer cells (Table S1†). Whether CW3 would be active against liver cancer and whether targeting the Ube2g2–gp78 interaction would induce side effects in the liver remain to be elucidated. Likewise, further studies are needed to discern the effects of CW3 on normal mammalian cell lines which are not screened by the NCI panel.

Fig. 3. Mean growth percentages of tumor cell lines in the presence of CW2 through CW20 (one-dose screening).

Fig. 4. Anticancer activity of CW3. (A) In vitro anticancer activity of CW3 tested with the National Cancer Institute (NCI) 60 tumor cell lines by the NCI Developmental Therapeutics Program. (B) Covalent docking of CW3 into its binding site on Ube2g2 results in the Ube2g2–CW3 conjugate.

The interaction between CW3 and the enzyme could be implicated by molecular docking, for which the Ube2g2 model, containing the allosteric binding site (Fig. 2D), was employed. As expected, CW3 was positioned such that a covalent bond was formed between its vinyl group and the thiol group of Cys48 (Fig. 4B). The dichlorobiphenyl moiety is positioned in the inner hydrophobic pocket of the allosteric binding site. A total of three hydrogen bonds were observed between CW3 and Ube2g2. As shown, the acetyl oxygen and amino nitrogen from the acetamido group of CW3 formed hydrogen bonds with the amino group of Cys48 and the hydroxyphenyl group of Tyr152, respectively. The third hydrogen bond is observed between the acetoxy oxygen of CW3 and the indole group of Trp144 (Fig. 4B).

3. Conclusions

We designed and synthesized a family of irreversible allosteric inhibitors of Ube2g2. The NCI 60 tumor cell line screen demonstrated that one such inhibitor, CW3, has significant inhibitory and lethiferous activities against most cell lines with a clear dose dependence. Ube2g2 is the specific E2 enzyme required for gp78 (E3) to promote tumor progression by facilitating ER-associated degradation of KAI1. As an irreversible allosteric inhibitor of Ube2g2, CW3 is a lead compound for the development of anticancer agents. Structure-based development of next generation inhibitors is undertaken in our laboratory for the improvement of potency and specificity as well as the understanding of detailed molecular mechanisms.

4. Experimental section

4.1. Homologous modeling

We modeled the Ube2g2 conformation that contains the allosteric binding site with the Phyre2 server16 using the one-to-one threading expert mode with the Cdc34 structure in the Cdc34:CC0651 complex (PDB entry ; 3RZ3)2 as the template. Structural illustrations were prepared with PyMOL (Delano Scientific LLC).

4.2. Chemistry

All reagents and solvents are commercially available from Sigma-Aldrich, except for (R)-Boc-2-amino-3-(4-iodophenyl)propionic acid (Boc-4-iodo-d-phenylalanine) and (S)-Boc-2-amino-3-(4-iodophenyl)propionic acid (Boc-4-iodo-l-phenylalanine), which were purchased from Chem-Impex International, and used without further purification.

The synthetic route for type D inhibitors (CW1 through CW10), starting from (R)-2-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino)-3-(4-iodophenyl)propanoic acid (1), is shown in Scheme 1. The synthetic route for type L inhibitors (CW11 through CW20), starting from (S)-2-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino)-3-(4-iodophenyl)propanoic acid (21), is shown in Scheme 2. The synthesis and characterization of compound 8 (CW3) is described below, whereas the synthetic details of other compounds can be found in the ESI.†

4.3. Synthesis of compound 8 (CW3)

Ethyl (R,E)-4-acrylamido-5-(3′,5′-dichloro-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)pent-2-enoate (8, CW3)

Acrylic acid (55 μL, 0.81 mmol) and PyAOP (0.42 g, 0.81 mmol) were added to 40 mL DMF and stirred at room temperature for 30 min, followed by the addition of 0.42 mL (0.24 mmol) DIPEA. Then, the mixture was stirred for 30 min before the addition of compound 7 (0.20 g, 0.55 mmol) and being stirred for 2 h. The resulting solvent was removed with a rotary evaporator and the residue was purified by HPLC to afford a white solid (0.12 g, 52% yield). NMR δ H (400 MHz; CDCl3), 1.28 (3H, t), 3.02 (2H, d), 4.16–4.21 (2H, m), 5.08 (1H, t), 5.55 (1H, d), 5.68 (1H, d), 5.87 (1H, d), 6.03–6.10 (1H, m), 6.29 (1H, d), 6.92–6.97 (1H, m), 7.26 (2H, d), 7.33 (1H, s), 7.44 (2H, s), 7.48 (2H, d). 13C NMR (CDCl3) 164.99, 164.00, 145.24, 142.54, 136.19, 135.61, 134.26, 129.20, 128.95, 126.44, 126.25, 126.13, 124.44, 120.86, 59.64, 49.81, 38.92, 13.18. MS (ESI): m/z calcd for C22H22Cl2NO3 [M + H]+ 418.10, found 418.0.

4.4. Cloning, expression, and purification of Ube2g2

Expression vectors were constructed by Gateway recombinational cloning (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). pDEST17-Ube2g2 was acquired from Addgene (Cambridge, MA, USA). This vector has a few tags on it. The Ube2g2 gene was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from this vector with primers 5′-GGGGACAACTTTGTACAAAAAAGTTGTGGAGAACCTGTACTTCCAGGGTGCGGGGACCGCGCTCAAGAGG and 5′-GGGGACAACTTTGTATAATAAAGTTGCATTACAGTCCCAGAGACTTCTGGACGA. The PCR product was recombined into the donor vector pDONR221 to produce the entry vector; the entry vector was recombined into the destination vectors pDEST-527 and pDEST HIS-MBP (Protein Expression Laboratory, Leidos Biomedical Research Inc., Frederick, MD, USA) to produce the expression vectors, expression vectors encoding a TEV protease-cleavable hexahistidine (His6) tag preceding Ube2g2 and His6 maltose-binding protein preceding Ube2g2. The proteins were produced in the Escherichia coli strain Rosetta 2(DE3) (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The cells were grown to the mid-log phase at 310 K in LB broth containing 100 mg mL–1 ampicillin and 30 mg mL–1 chloramphenicol. Overproduction of the fusion protein was induced with IPTG at a final concentration of 0.5 mM for 4 h at 303 K. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation and stored at 193 K. For protein purification, all procedures were performed at 277–281 K. 15 g of the E. coli cell paste was suspended in 150 mL lysis buffer (25 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl). The cells were lysed with an APV-2000 homogenizer (Invensys APV Products, Albertslund, Denmark) at 69 MPa and centrifuged at 30 000g for 30 min. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.2 mm polyethersulfone membrane and applied onto an IMAC 30 mL column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) equilibrated with buffer A (10 mM phosphate, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole). The column was washed to baseline with buffer A and eluted with a linear gradient of imidazole to 500 mM in buffer A. Fractions containing the recombinant protein were pooled, concentrated using an Amicon YM10 membrane (EMDMillipore, Billerica, MA, USA), diluted to an imidazole concentration of about 25 mM with 10 mM phosphate, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl buffer and digested overnight at 277 K with His6-tagged TEV protease.18,19 The TEV protease digestion, which removed the His6 affinity tag and amino acids encoded by sequences that facilitate Gateway cloning, resulted in a native protein product devoid of cloning artifacts. The digest was applied onto a 30 mL IMAC column equilibrated in buffer A and the recombinant protein emerged in the column effluent. The effluent was concentrated using an Amicon YM10 membrane. Aliquots were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at 193 K. The molecular weight of the product was confirmed by electrospray ionization mass spectroscopy.

4.5. LC/MS analysis of inhibitor–protein conjugates

All compounds (CW1–CW20) were dissolved in DMSO at 10 mM. The concentrated protein at 10 mg mL–1 was diluted 10 times in buffers at different pH values. 40 μL of the diluted protein solutions were placed in mass spectroscopy sample vials, and 5 μL of the compound solutions were added to each vial and incubated overnight at room temperature. An Agilent 6100 single quadrupole mass spectrometer was used to detect the protein–inhibitor conjugation products.

4.6. NCI 60 human cancer cell line screening

We submitted 19 compounds (CW2–CW20) to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Developmental Therapeutics Program (DTP) for human cancer cell line screening, for which their standard methodology and protocols are described in the ESI.† For both one- and five-dose assays, growth relative to the no-drug control and relative to the number of cells at time zero was reported, allowing the detection of both growth inhibition (values between 0 and 100) and lethality (negative values). For example, a value of 100 means no growth inhibition, a value of 40 means 60% growth inhibition, a value of 0 means no net growth, a value of –40 means 40% lethality, and a value of –100 means all cells are dead.

4.7. Molecular docking

The Ube2g2–CW3 model was built using the Schrödinger Maestro interface (Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2018). The CW3 structure was prepared in its pre-reactive form with LigPrep. The Ube2g2 preparation was performed with the Protein Preparation Wizard. The grid was generated by the Receptor Grid Generation facility. The covalent docking pose was formed by Covalent Docking using the Pose Prediction mode.

Abbreviations

- Cdc34

Cell division cycle 34

- E2

Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme

- E3

Ubiquitin ligase

- His6

Hexahistidine

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- PDB

Protein data bank

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. Mass spectrometry experiments were conducted at the Biophysics Resource in the Structural Biophysics Laboratory of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The NCI 60 tumor cell line screens were performed by the NCI's Developmental Therapeutics Program.

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c8md00320c

References

- Li W., Bengtson M. H., Ulbrich A., Matsuda A., Reddy V. A., Orth A., Chanda S. K., Batalov S., Joazeiro C. A. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceccarelli D. F., Tang X., Pelletier B., Orlicky S., Xie W., Plantevin V., Neculai D., Chou Y. C., Ogunjimi A., Al-Hakim A., Varelas X., Koszela J., Wasney G. A., Vedadi M., Dhe-Paganon S., Cox S., Xu S., Lopez-Girona A., Mercurio F., Wrana J., Durocher D., Meloche S., Webb D. R., Tyers M., Sicheri F. Cell. 2011;145:1075–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Dixit V. M. Cell Res. 2016;26:484–498. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattern M. R., Wu J., Nicholson B. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1823:2014–2021. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lub S., Maes K., Menu E., De Bruyne E., Vanderkerken K., Van Valckenborgh E. Oncotarget. 2016;7:6521–6537. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wijk S. J., Timmers H. T. FASEB J. 2010;24:981–993. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-136259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabi I. R., Watanabe H., Silletti S., Raz A. EXS. 1991;59:163–177. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-7494-6_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Mariano J., Tsai Y. C., Chan A. H., Cohen M., Weissman A. M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:341–346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506618103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W. M., Zhang X. A. Cancer Lett. 2006;240:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai Y. C., Mendoza A., Mariano J. M., Zhou M., Kostova Z., Chen B., Veenstra T., Hewitt S. M., Helman L. J., Khanna C., Weissman A. M. Nat. Med. 2007;13:1504–1509. doi: 10.1038/nm1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai R., Yoshikawa S., Murayama K., Imai Y., Takahashi R., Shirouzu M., Yokoyama S. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. F: Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2006;62:330–334. doi: 10.1107/S1744309106009006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Tu D., Li L., Wollert T., Ghirlando R., Brunger A. T., Ye Y. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:3722–3727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808564106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das R., Mariano J., Tsai Y. C., Kalathur R. C., Kostova Z., Li J., Tarasov S. G., McFeeters R. L., Altieri A. S., Ji X., Byrd R. A., Weissman A. M. Mol. Cell. 2009;34:674–685. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das R., Liang Y. H., Mariano J., Li J., Huang T., King A., Tarasov S. G., Weissman A. M., Ji X., Byrd R. A. EMBO J. 2013;32:2504–2516. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwob E., Bohm T., Mendenhall M. D., Nasmyth K. Cell. 1994;79:233–244. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley L. A., Mezulis S., Yates C. M., Wass M. N., Sternberg M. J. Nat. Protoc. 2015;10:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Kho D. H., Wang Y., Harazono Y., Nakajima K., Xie Y., Raz A. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapust R. B., Tözsér J., Fox J. D., Anderson D. E., Cherry S., Copeland T. D., Waugh D. S. Protein Eng. 2001;14:993–1000. doi: 10.1093/protein/14.12.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropea J. E., Cherry S., Waugh D. S. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009;498:297–307. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-196-3_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.