Abstract

Objective

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigs) are an emerging trend, yet little is known about their use in the cancer population. The objectives of this study were (1) to describe characteristics of e-cig use among cancer patients, (2) to define e-cig advertising exposure, and (3) to characterize perceptions of traditional cigarettes versus e-cigs.

Study Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Comprehensive cancer center.

Subjects and Methods

Inpatient, current smokers with a cancer diagnosis. E-cig exposure and use were defined using descriptive statistics. Wilcoxon rank test was used to compare perceptions between e-cigs and traditional cigarettes.

Results

A total of 979 patients were enrolled in the study; 39 cancer patients were identified. Most cancer patients were women (59%), with an average age of 53.3 years. Of the patients, 46.2% reported e-cig use, most of which (88.9%) was “experimental or occasional.” The primary reason for e-cig use was to aid smoking cessation (66.7%), alternative use in nonsmoking areas (22.2%), and “less risky” cigarette replacement (5.6%). The most common sources for e-cig information were TV (76.9%), stores (48.7%), friends (35.9%), family (30.8%), and newspapers or magazines (12.8%). Compared with cigarettes, e-cigs were viewed as posing a reduced health risk (P < .001) and conferring a less negative social impression (P < .001). They were also viewed as less likely to satisfy nicotine cravings (P = .002), to relieve boredom (P = .0005), to have a calming effect (P < .001), and as tasting pleasant (P = .006)

Conclusions

E-cig use and advertising exposure are common among cancer patients. E-cig use is perceived as healthier and more socially acceptable but less likely to produce a number of desired consequences of cigarette use.

Keywords: electronic cigarettes, smoking cessation, cancer patients

Cigarette smoking after a cancer diagnosis has been shown to increase the risk of adverse outcomes, including disease recurrence, poor quality of life, wound-healing complications, and mortality.1,2 Conversely, smoking cessation has been shown to be protective and to lead to better treatment outcomes in cancer patients.3-5 For this reason, tobacco cessation for cancer patients is strongly advocated by oncology professionals, including the American Society of Clinical Oncology.6 Traditional methods for smoking cessation include counseling and pharmacotherapy, such as nicotine replacement or other medications designed to reduce withdrawal.7 Vaping devices, often known as electronic cigarettes (e-cigs), emerged on the market in the United States in 2007 and have rapidly gained popularity.8 E-cigs are noncombustible devices that vaporize a liquid that contains nicotine; the liquid comes in a variety of flavors, and there is a wide variation in delivery devices.9 In the past several years, the use of e-cigs has increased. US general population surveys showed that use of e-cigarette ever use in the population increased from 3.3% in 2010 to 8.5% in 2013.10 Current use was found to be highest in cigarette smokers and increased from 4.9% in 2010 to 9.4% in 2012.10 In the current smoker population, 32% had ever tried e-cigarettes.8 Unfortunately, little is known about the safety, efficacy for smoking cessation, exposure, perceptions, and general use of e-cigs among the vulnerable and high-risk cancer population. This study aimed, therefore, to investigate e-cig exposure, use, and perceptions among individuals with cancer.

Methods

Study Design

This cross-sectional study was performed at a National Cancer Institute–designated Comprehensive Cancer Center–associated hospital between December 2012 and September 2013. The University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. All inpatients older than 18 years of age and identified as a current smoker on hospital admission were approached for enrollment in the observational study. Patients met inclusion criteria if they verified current smoking within the past 30 days and had a documented cancer diagnosis based on ICD-9 codes. This included all cancer diagnoses and was not specific to head and neck cancer. Further data regarding specific cancer type, stage, or outcomes were not available. Exclusion criteria included any patient not physically or cognitively able to participate in the study and non-English speakers. All participants signed informed consent forms prior to participation.

Survey Components

Data were collected regarding demographics, e-cig use, and e-cig information or advertising exposure sources. Desire to quit smoking and confidence in quitting were assessed using a 0 (not at all) to 10 (very high) response scale. The Brief Smoking Consequences Questionnaire–Adult (BSCQ-A) assessed cigarette-specific expectancy domains on 10 scales: Negative Affect Reduction, Stimulation/State Enhancement, Health Risks, Taste/Sensorimotor Manipulation, Social Facilitation, Weight Control, Craving/Addiction, Negative Physical Feelings, Boredom Reduction, and Negative Social Impression.11 Patients rated items on each scale using a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (completely unlikely) to 9 (completely likely). An analogous set of BSCQ-A items was administered to assess expectancies specific to e-cig use, using the same response scale as above.12 All patients were assessed on cigarette and e-cig–specific expectancy domains.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to report patient demographics, e-cig use, and e-cig advertising exposure. Mean values of the cigarette-specific BSCQ-A were compared with those of the e-cig–specific BSCQ-A using the Wilcoxon ranked sign test (IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0, New York, New York). A Wilcoxon ranked sign test was used due to nonnormal data. A critical absolute Z value of 1.96 was used to reject the null hypothesis with a 95% confidence interval.

Results

Of 979 current smokers enrolled in the observational study, 39 carried a current cancer diagnosis at the time of hospital admission. Demographic details are listed in Table 1 . Most participants were women, with an average age of just less than 50 years. Approximately three-fifths of the cohort were white, and approximately half reported at least some college education.

Table 1.

Demographic Information.

| Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Average age, y | 49.33 (range, 21-69) | |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 16 | 41.0 |

| Women | 23 | 59.0 |

| Race | ||

| White | 22 | 56.4 |

| Black | 15 | 38.5 |

| American Indian | 1 | 2.6 |

| Native Indian | 1 | 2.6 |

| Education | ||

| Some high school or less | 8 | 20.5 |

| High school graduate | 7 | 17.9 |

| GED | 4 | 10.3 |

| Some college | 16 | 41.0 |

| 4-y degree or higher | 4 | 10.3 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married or domestic partner | 15 | 38.5 |

| Separated | 4 | 10.3 |

| Divorced | 7 | 17.9 |

| Widowed | 3 | 7.7 |

| Never married | 10 | 25.6 |

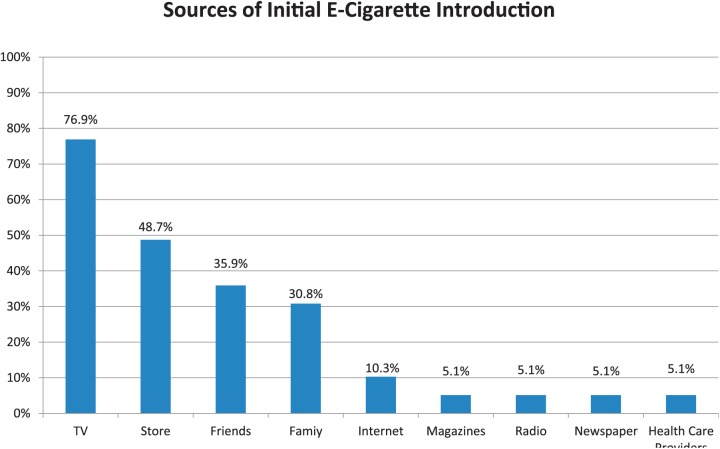

All cancer patients had heard of e-cigs and reported initial exposure from a variety of sources ( Figure 1 ). The most common general sources of e-cig information were television (76.9%), followed by stores (48.7%), friends (35.9%), family (30.8%), Internet advertisements (10.3%), magazines (5.1%), radio (5.1%), newspaper (5.1%), and health care providers (5.1%). Only 9 patients (23%) actively sought out e-cig information on their own; the remaining 77% encountered the information passively. Patients report viewing a median of 10 e-cig advertisements in the past 6 months (range = 3-840). The most common sources of specifically e-cig media advertising exposure were radio or TV (79.5%), stores (38.5%), newspapers or magazines (12.8%), and the internet (7.7%).

Figure 1.

Sources of initial e-cigarette exposure.

Of the 18 cancer patients (46.2%) reporting previous e-cig use, 38.9% (n = 7) had used them in the past 30 days. Among users, reasons for e-cig use included to help quit smoking cigarettes (66.7%), to have something to smoke in nonsmoking areas (22.2%), and to use as a less risky product compared with traditional cigarettes (5.6%). One patient did not know why he or she used e-cigs. With respect to frequency of e-cig use, 50% reported “experimental” use, 38.9% “occasional” use, and 11.1% “regular” use. Most patients reported a significant desire to quit smoking, with 89.7% scoring a 6 or greater on the 10-point scale. Most patients reported high confidence that they would be successful in quitting, with 79.5% scoring 6 or greater. The remaining 21 cancer patients (53.8%) enrolled in the study had never used e-cigs. On a scale of 1 (not at all likely) to 10 (very likely), 59.0% of nonusers reported they would be likely to use e-cigs in the future (score of 6 or greater). Patients who had tried e-cigs had seen a mean of 85 (SD = 202) ads in the past 6 months compared with 24 (SD = 49) for those who had not tried e-cigs (P = .27).

All cancer patients were surveyed regarding expectancies toward cigarettes and e-cigs. Six of the 10 BSCQ-A expectancy scales were significantly different between cigarettes and e-cigs: Negative Affect Reduction, Health Risks, Taste/Sensorimotor Manipulation, Craving/Addiction, Boredom Reduction, and Negative Social Impression ( Table 2 ). Compared with cigarettes, e-cigs were viewed as less likely to relieve negative affect. They were also viewed as less of a health risk compared with cigarettes. Participants also thought they would be less likely to enjoy the taste of e-cigs and that e-cigs would be less likely to satisfy their craving for nicotine. E-cigs were also perceived as less likely to reduce boredom than cigarettes and as conferring a less negative social impression (ie, less social stigma). The remaining 4 expectancy constructs did not differ between cigarettes and e-cigs.

Table 2.

Perceptions of E-cigarettes versus Traditional Cigarettes.a

| Mean for E-cigarettes | Mean for Traditional Cigarettes | Z Valueb | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Affect Reduction | 4.61 | 6.62 | 3.560 | <.001 |

| Stimulation/State Enhancement | 3.23 | 2.85 | 0.061 | .951 |

| Health Risks | 5.12 | 8.20 | 4.289 | <.001 |

| Taste/Sensorimotor Manipulation | 4.29 | 6.10 | 2.768 | .006 |

| Social Facilitation | 2.72 | 3.22 | 0.996 | .319 |

| Weight Control | 2.64 | 3.71 | 1.690 | .091 |

| Craving/Addiction | 4.70 | 6.66 | 3.127 | .002 |

| Negative Physical Feelings | 2.61 | 2.99 | 0.725 | .468 |

| Boredom Reduction | 3.89 | 5.40 | 2.811 | .005 |

| Negative Social Impression | 3.39 | 5.20 | 3.485 | <.001 |

Group means are based on the average from several questions related to the topics as scored from 0 = completely unlikely to 9 = completely likely.

Absolute Z values greater than 1.96 are sufficient to reject the null hypothesis using 95% confidence intervals for each comparison.

Discussion

E-cigarette Use

Electronic cigarettes have gained tremendous popularity since emerging onto the American market in 2007. However, many questions remain regarding exposure, perceptions, safety, and efficacy for smoking cessation. In addition, a paucity of data exists regarding e-cig use among hospitalized smokers,13 particularly cancer patients.

In our small study, we report a 46.6% rate of e-cig use among current smokers with cancer. This rate exceeds previously published reports of 38.5% in 2013.14 In addition, it exceeds the rate in the general population, in which e-cig use falls between 7.9% to 32%,9,15 and it is similar to the rate reported for the general population of smokers in the same hospital.16 One possible explanation for increase in e-cig use is aggressive advertising. E-cig advertising expenditures have increased from $6.4 million in 2011 to $18.3 million in 2012.17,18 Our study identified a variety of sources exposing cancer patients to e-cig information and advertising. Advertisements specifically portray e-cigs as healthier nicotine alternatives, less expensive, and more effective in smoking cessation.17 This study did confirm several of these advertising messages. Specifically, e-cigs were perceived as less of a health risk and more socially acceptable compared with cigarettes. However, in this cohort of cancer patients, there was no perceived difference between e-cigs and cigarettes when it came to appetite suppression, physical side effects (ie, throat irritation), social facilitation, and stimulating effects. In addition, some negative perceptions toward e-cigs were elucidated, such as e-cigs were perceived as less likely to satisfy nicotine cravings, not taste as good as traditional cigarettes, less likely to reduce negative affect, and less likely to reduce boredom.

With the vast majority of patients exposed to advertising for e-cigs, it is imperative to understand how this marketing is influencing both smokers and nonsmokers alike. Understanding perceptions of e-cigs is particularly important given the uncertainty regarding the safety and efficacy of e-cigs for smoking cessation.15,19,20 It is also salient for cancer patients who are strongly encouraged by health care providers to quit smoking and, therefore, are more likely to seek products they perceive as helpful in smoking cessation.

While cigarette advertising has been regulated since the 1970s, e-cig advertising is unhindered, and advertisements are pervasive on television, social media, and magazines.21 Youth and adolescents are particularly susceptible to these outlets and are frequently exposed to e-cig advertisements. Previous research has shown that most smokers try their first cigarette as young adults. As more tobacco products enter the market, those who otherwise may not have tried cigarettes could be more inclined to use novel tobacco products.22 Youth are particularly susceptible to influences by media and advertising.23 Recent research has shown that youth who have tried e-cigs are more open to trying cigarettes.18 This increase in advertising coupled with susceptible youth could lead to e-cigs becoming a potential “gateway” into using traditional cigarettes.

E-cigarette Safety

This study documents a perception that e-cigs are less unhealthy than cigarettes. Preliminary studies do indicate that there is less health risk than with cigarettes. In one recent study, cellular carcinogenic effects on oral cavity mucosa were studied in 3 groups: cigarette smokers, e-cig users, and nonsmokers.24 There were significantly fewer cytologic changes in the e-cig group compared with the cigarette group, implying improved cancer risk.24 While there are data to support that e-cigs are less toxic than cigarettes, the safety and potential harm of e-cigs have not been definitively established.9

In counseling patients, it is important to note that e-cigs are currently unregulated and sold by a variety of manufacturers; thus, the specific liquid contents (and nicotine concentration) vary and are often unknown.9,25 While reports indicate that e-cigs contain lower levels of harmful chemicals than cigarettes do,26 e-cigs do contain carcinogens such as formaldehyde.27 Thus, while cancer patients view e-cigarettes as less unhealthy, long-term data are unavailable about the potential health risks of e-cigs relative to cigarettes. There are also no data with respect to how e-cigs might affect cancer therapy and outcomes.

Counseling Patients on E-cigarettes as a Smoking Cessation Aid

Understanding patient rationale for e-cig use is imperative for health care providers to successfully counsel cancer patients in smoking cessation. In this study, 46.2% of patients cited using e-cigs as an aid to smoking cessation; however, their efficacy for smoking cessation remains to be determined. This important point must be disclosed to patients trying to quit smoking. This responsibility will fall on the health care industry as opposed to the advertising and e-cig industry.

While patients often use e-cigs as an aid to quit cigarette use, the evidence on their efficacy is conflicting. A recent Cochrane Review of 2 small prospective randomized trials concluded that e-cigs help long-term smoking cessation when compared with placebo e-cigs.28 One of the studies compared nicotine-containing e-cigs to both nicotine-free e-cigs and the transdermal nicotine patch; the authors found that whereas rates of abstinence were not statistically different between the 3 groups, nicotine-containing e-cigs had the highest quit rate.29 A small prospective trial identified 23% of e-cigarette users achieving 30-day cigarette abstinence, and one-third reduced cigarette consumption by at least 50%.30 However, other studies indicate that e-cigs may be less effective for smoking cessation. A 2011 survey revealed that e-cigs were associated with an unsuccessful quit attempt.31 E-cigs have also been found to be associated with a reduction in smoking, but actual cessation rates did not differ between e-cig users and nonusers.32 In another large cross-sectional survey in the United Kingdom, those attempting to quit with e-cigs smoked more cigarettes and were more dependent as measured by strength of urges as opposed to those who quit “cold turkey” (ie, without any pharmacotherapy or without e-cigs).15

Limited information is available about e-cig use among cancer patients. One survey found that e-cig users were just as likely to smoke at follow-up as compared with nonusers and that a higher average number of cigarettes were smoked per day among e-cig users.14 The preliminary data, therefore, do not support the efficacy of e-cigs for smoking cessation among individuals with cancer. Practitioners should take care to recommend empirically supported interventions, including behavioral counseling and approved pharmacotherapies (ie, nicotine replacement therapies, bupropion, and varenicline) and exercise caution and encourage skepticism with regard to e-cigs.

Conclusion

Cancer patients are a high-risk population portending worse health outcomes with continued cigarette use. E-cig advertising is pervasive. With the increasing popularity of e-cigs, a high proportion of cancer patients who smoke have used e-cigs because they are perceived as a less unhealthy alternative and more socially acceptable as compared with cigarettes. Additional research and cancer patient education are required because the short- and long-term health risks and benefits of e-cigarettes remain unknown.

Author Contributions

Erin J. Buczek, data analysis and interpretation, drafting, final approval, and accountability for the work; Kathleen F. Harrington, data collection, revising the work, final approval, and accountability for the work; Peter S. Hendricks, data analysis, revising the work, final approval, and accountability for the work; Cecelia E. Schmalbach, data analysis and interpretation, drafting and revising the work, final approval, and accountable for the work.

Disclosures

Competing interests: None.

Sponsorships: None.

Funding source: National Institute on Drug Abuse to Dr Harrington (grant RO1DA031515-S1).

Footnotes

This article was presented at the 2015 Deep South Regional Otolaryngology Annual Meeting; June 2015; Destin, Florida.

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Warren GW, Alberg AJ, Kraft AS, Cummings KM. The 2014 Surgeon General’s report: “The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress”: a paradigm shift in cancer care. Cancer. 2014;120:1914-1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gajdos C, Hawn MT, Campagna EJ, Henderson WG, Singh JA, Houston T. Adverse effects of smoking on postoperative outcomes in cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1430-1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, et al. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:341-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Parsons A, Daley A, Begh R, Aveyard P. Influence of smoking cessation after diagnosis of early stage lung cancer on prognosis: systematic review of observational studies with meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:b5569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McBride CM, Ostroff JS. Teachable moments for promoting smoking cessation: the context of cancer care and survivorship. Cancer Control. 2003;10:325-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hanna N. Helping patients quit tobacco: ASCO’s efforts to help oncology care specialists. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9:263-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhu SH, Gamst A, Lee M, Cummins S, Yin L, Zoref L. The use and perception of electronic cigarettes and snus among the U.S. population. PloS One. 2013;8:e79332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harrell PT, Simmons VN, Correa JB, Padhya TA, Brandon TH. Electronic nicotine delivery systems (“e-cigarettes”): review of safety and smoking cessation efficacy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151:381-393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. King BA, Alam S, Promoff G, Arrazola R, Dube SR. Awareness and ever-use of electronic cigarettes among U.S. adults, 2010-2011. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:1623-1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rash CJ, Copeland AL. The Brief Smoking Consequences Questionnaire-Adult (BSCQ-A): development of a short form of the SCQ-A. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1633-1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hendricks PS, Cases MG, Thorne CB, et al. Hospitalized smokers’ expectancies for electronic cigarettes versus tobacco cigarettes. Addict Behav. 2015;41:106-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rigotti NA, Harrington KF, Richter K, et al. Increasing prevalence of electronic cigarette use among smokers hospitalized in 5 US cities, 2010-2013. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:236-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Borderud SP, Li Y, Burkhalter JE, Sheffer CE, Ostroff JS. Electronic cigarette use among patients with cancer: characteristics of electronic cigarette users and their smoking cessation outcomes. Cancer. 2014;120:3527-3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brown J, Beard E, Kotz D, Michie S, West R. Real-world effectiveness of e-cigarettes when used to aid smoking cessation: a cross-sectional population study. Addiction. 2014;109:1531-1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harrington KF, Hull NC, Akindoju O, et al. Electronic cigarette awareness, use history, and expected future use among hospitalized cigarette smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16:1512-1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pepper JK, Emery SL, Ribisl KM, Southwell BG, Brewer NT. Effects of advertisements on smokers’ interest in trying e-cigarettes: the roles of product comparison and visual cues. Tob Control. 2014;23(suppl 3):iii31-iii36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Coleman BN, Apelberg BJ, Ambrose BK, et al. Association between electronic cigarette use and openness to cigarette smoking among US young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:212-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Avdalovic MV, Murin S. Electronic cigarettes: no such thing as a free lunch…Or puff. Chest. 2012;141:1371-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wagener TL, Siegel M, Borrelli B. Electronic cigarettes: achieving a balanced perspective. Addiction. 2012;107:1545-1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hildick-Smith GJ, Pesko MF, Shearer L, et al. A practitioner’s guide to electronic cigarettes in the adolescent population. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57:574-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Preventing tobacco use among young people. A report of the Surgeon General. Executive summary. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1994;43:1-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Do MP, Kincaid DL. Impact of an entertainment-education television drama on health knowledge and behavior in Bangladesh: an application of propensity score matching. J Health Commun. 2006;11:301-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Franco T, Trapasso S, Puzzo L, Allegra E. Electronic cigarette: role in the primary prevention of oral cavity cancer. Clin Med Insights Ear Nose Throat. 2016;9:7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cheah NP, Chong NW, Tan J, Morsed FA, Yee SK. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: regulatory and safety challenges: Singapore perspective. Tob Control. 2014;23:119-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goniewicz ML, Knysak J, Gawron M, et al. Levels of selected carcinogens and toxicants in vapour from electronic cigarettes. Tob Control. 2014;23:133-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jensen RP, Luo W, Pankow JF, Strongin RM, Peyton DH. Hidden formaldehyde in e-cigarette aerosols. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:392-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McRobbie H, Bullen C, Hartmann-Boyce J, Hajek P. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation and reduction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12:CD010216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bullen C, Howe C, Laugesen M, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382:1629-1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Polosa R, Caponnetto P, Morjaria JB, Papale G, Campagna D, Russo C. Effect of an electronic nicotine delivery device (e-Cigarette) on smoking reduction and cessation: a prospective 6-month pilot study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Popova L, Ling PM. Alternative tobacco product use and smoking cessation: a national study. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:923-930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Adkison SE, O’Connor RJ, Bansal-Travers M, et al. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: international tobacco control four-country survey. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:207-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]