Summary

DNA-targeting CRISPR-Cas systems, such as those employing the RNA-guided Cas9 or Cas12 endonucleases, have revolutionized our ability to predictably edit genomes and control gene expression. Here, I summarize information on RNA-targeting CRISPR-Cas systems and describe recent advances in converting them into powerful and programmable RNA binding and cleavage tools with a wide-range of novel and important biotechnological and biomedical applications.

Introduction

CRISPR-Cas: Small RNA-mediated prokaryotic immune systems.

CRISPR-Cas (Clustered Regularly Interspersed Short Palindromic Repeat-CRISPR-Associated) systems provide acquired immunity against viruses and other mobile genetic elements in bacteria and archaea (Hille et al., 2018; Jackson et al., 2017; Makarova et al., 2015; Shmakov et al., 2015). These systems first recognize and incorporate short fragments of invader DNA into host genomic CRISPR arrays to provide heritable immunity against specific invaders. The CRISPR arrays, consisting of alternating repeat and invader-derived (spacer) DNA sequences flanked by a leader region, are transcribed and processed into small, mature CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs). The crRNAs associate with one or more Cas proteins to form various crRNA-Cas (crRNP) effector complexes. CRISPR-Cas systems typically function by sequence-specific destruction of invading complementary nucleic acids by these effector crRNPs.

Diverse crRNA-Cas effector complexes.

There is remarkable structural and functional diversity among the known CRISPR-Cas systems (Hille et al., 2018; Jackson et al., 2017; Makarova et al., 2015) (Table 1). Based on the assortment of cas genes and the properties of the crRNP effector complexes, CRISPR-Cas systems have been grouped into six distinct types (Type I-VI, each with signature Cas nuclease components), and further catalogued into two broad classes (Class 1 or 2) (Makarova et al., 2015). In Class 1 systems (Types I, III, and IV), the effector complexes are comprised of multiple Cas proteins (including one or more nuclease components) in tight association with the crRNA. In contrast, Class 2 systems (Types II, V, VI) harbor effector crRNPs containing just a single, multi-domain effector protein with nuclease activity. Within each type, there are multiple subtypes that exhibit different structural and functional properties (Table 1), leading to an impressive arsenal of specialized weaponry used globally by diverse prokaryotes to defend themselves against attack from viruses and other intrusive mobile genetic elements.

Table 1.

Diversity and properties of the six types of CRISPR-Cas systems.

| Type | Class | Natural Target(s) |

Effector Nuclease/Nuclease(s) Domain(s) |

Subtypes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 1 | DNA | Cas3/HD | I-A, B, C, D, E, F, G |

| II | 2 | DNA | Cas9 / RuvC + HNH | II-A, B, C |

| III | 1 | RNA | Csm3, Cmr4 / autocatalytic? | III-A (Csm) III-B (Cmr) III-C III-D |

| Csm6, Csx1 / HEPN | ||||

| DNA | Cas10 (Csm1 or Cmr2) / HD | |||

| IV | 1 | DNA? | Csf1 ? / ? | IV-A, B |

| V | 2 | DNA | Cas12 (RuvC) | V-A (Cpfl), B (C2c1), C (C2c3) |

| VI | 2 | RNA | Cas13 (HEPN × 2) | Vl-A (Cas13a / C2c2) Vl-B (Cas13b) Vl-C (Cas13c) Vl-D (Cas13d) |

The nucleic acid substrates recognized and destroyed by the various effector crRNPs (Table 1) also differ among the different CRISPR-Cas systems. Types I, II, V (and likely IV) target DNA, while Type III systems support cleavage of both DNA and RNA. Type VI systems appear to exclusively target RNA. Systems that function exclusively through DNA targeting have evolved to rely on recognition of a short (2-5 base pair) sequence, called the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), located immediately adjacent to the target sequence in the invader DNA. Presence of the PAM is essential for degradation. A PAM is not present adjacent to the identical sequence within the host CRISPR array, since that sequence is flanked by the repeats, and self-targeting does not occur (Leenay et al., 2016). In contrast, the function of Type III and VI systems that carry out RNA targeting, appear not to rely on consensus PAMs. However, the activity of various studied Type III (Elmore et al., 2016; Gootenberg et al., 2017; Pyenson et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2018) and Type VI effector crRNPs (Abudayyeh et al., 2017; Abudayyeh et al., 2016; Smargon et al., 2017; Meeske, 2018 #125}) have been shown to be regulated by sequences that flank the protospacers of the target RNAs (referred to as protospacer flanking sequences (PFS)). .

Repurposing natural weaponry into innovative DNA-targeting CRISPR-based research tools.

Historically, CRISPR-based research tools have primarily arisen from harnessing the properties of single-effector (Class 2) systems that naturally function through DNA cleavage mechanisms including Type II Cas9 and Type V Cas12 (Table 1) (Hille et al., 2018; Shmakov et al., 2015; Terns and Terns, 2014). Nuclease-defective dCas9 and dCas12 systems, including variants with fused effector domains or proteins, have significantly expanded the capabilities of these research tools (Xu and Qi, 2018). The ability to reprogram these systems by creating engineered crRNAs designed to bind and/or cleave specific DNA sequences has led to their utility in a wide range of organisms and cell types (including human cells). The diverse applications of these DNA binding and cleavage systems include genome editing, specific gene expression control, and DNA tracking in live cells, to name just a few. The DNA-based CRISPR research tools developed thus far are already having a major impact on essentially all areas of the life sciences and support important applications in biotechnology, agriculture and medicine (Wang et al., 2016; Wright et al., 2016).

Expansion of the CRISPR-based tool box to include systems that target RNA.

To broaden the utility of CRISPR-based research tools, a major effort is currently underway to establish and deploy systems capable of selective recognition and/or cleavage of RNA molecules. This initiative is of enormous potential given the central importance of RNA (both protein-coding (mRNA) and non-coding RNAs (e.g. microRNAs, lncRNAs, small nucleolar RNAs, etc.) in controlling virtually all cellular pathways and functions. Moreover, existing research tools to detect and manipulate specific RNA molecules are limited. As described below, novel CRISPR-based RNA-targeting tools from Type II, III, and VI crRNP effector complexes have already been developed for endogenous RNA knockdown, site-specific RNA editing, RNA localization studies, sensitive diagnostic detection of nucleic acid signatures of viruses and pathogenic bacteria as well as human cancer-related mutations, and destruction of toxic RNAs that lead to human neurodegenerative disorders.

The focus of this review is to highlight the features of the specific CRISPR-Cas systems known to naturally bind and cleave RNA substrates and to summarize current and potential applications of emerging technologies centered on RNA targeting CRISPR-based systems.

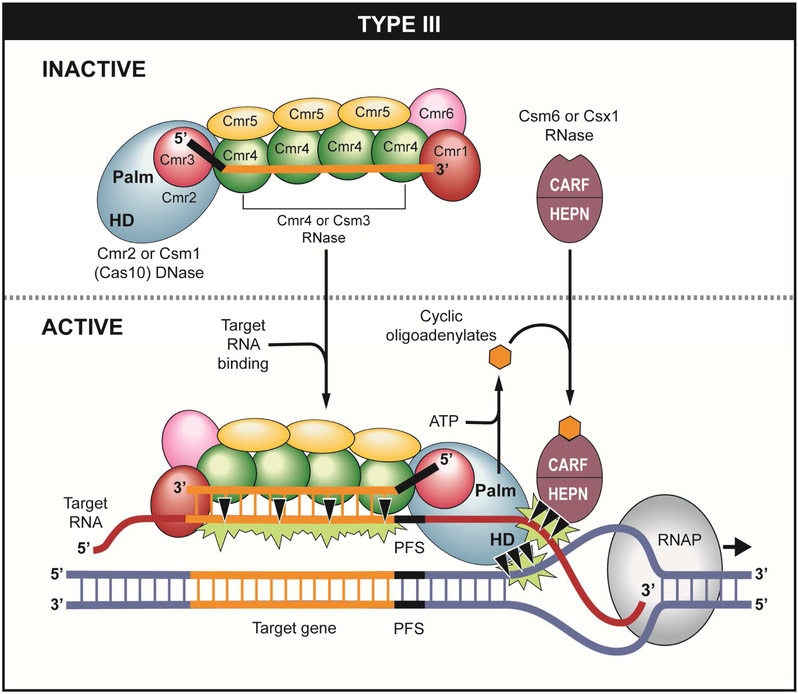

Type III CRISPR-Cas Systems

Type III (Class 1) CRISPR-Cas systems naturally target invaders at both the RNA and DNA levels (Figure 1). Interestingly, DNA targeting by Type III systems occurs only if the target DNA is actively transcribed as demonstrated for both Type III-A (Goldberg et al., 2014; Kazlauskiene et al., 2016; Samai et al., 2015). and Type III-B systems (Deng et al., 2013; Elmore et al., 2016; Estrella et al., 2016; Han et al., 2016). Type III systems employ three distinct nucleases (two endoribonucleases and one DNase) to eradicate invasive nucleic acids that match their crRNAs (Table 1 and Figure 1). In the absence of invasive nucleic acids, Type III crRNPs and the three nuclease activities are maintained in an inactive state (Figure 1). Interaction between the newly transcribed invader target RNA and the crRNA of Type III effector crRNPs triggers the RNase and DNase activities resulting in co-transcriptional destruction of the non-template strand of invader DNA as well as degradation of the target RNA (Figure 1) for both Type III-A (Cao et al., 2016; Goldberg et al., 2014; Hatoum-Aslan et al., 2014; Ichikawa et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2016; Marraffini and Sontheimer, 2008, 2010; Millen et al., 2012; Samai et al., 2015; Staals et al., 2014; Tamulaitis et al., 2014) and Type III-B systems (Deng et al., 2013; Elmore et al., 2016; Estrella et al., 2016; Hale et al., 2014; Han et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2012).

Figure 1.

Type III CRISPR systems employ multiple-subunit crRNP effector complexes and function through both RNA and DNA targeting mechanisms. Target RNA binding by the crRNP effector complexes activates three distinct nucleases (two RNases and one DNase) that collectively destroy transcriptionally active target DNA and RNA substrates.

RNA targeting and cleavage by a CRISPR-Cas system was first discovered for the Type III-B (Cmr) system of the hyperthermophilic archaeon, Pyrococcus furiosus (Hale et al., 2009). A complex consisting of crRNA and six Cas proteins (Cmr1-6) was isolated from the native organism and shown to specifically recognize and cleave RNAs that exhibited complementarity to the crRNA guides. Subsequently, related Type III-A (Csm) systems were demonstrated to use a highly similar mechanism to cleave bound target RNAs (Kazlauskiene et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017c; Samai et al., 2015; Staals et al., 2014; Tamulaitis et al., 2014). In both Type III-A and III-B systems, a particular Cas protein subunit (Csm3 in Type III-A and Cmr4 in Type III-B) is found in four or more copies along the backbone of the complex. Both Csm3 (Hatoum-Aslan et al., 2013; Staals et al., 2014; Tamulaitis et al., 2014) and Cmr4 (Benda et al., 2014; Hale et al., 2014; Ramia et al., 2014a; Zhu and Ye, 2015) are endoribonucleases in the Cas7 superfamily (Makarova et al., 2015) and they cleave the target RNA at 6 nucleotide intervals such that each target RNA molecule is cut four or more times in the region of crRNA/target RNA complementarity (Figure 1).

Csm6 (III-A) or Csx1 (III-B) proteins provide the second RNase activity of Type III systems (Figure 1). These proteins share N-terminal CARF (Cas-associated Rossman Fold) and C-terminal HEPN (Higher Eukaryotes and Prokaryotes Nucleotide-binding) domains. The RNase activity maps to a R-X4-6-H active site located within the HEPN domain (Anantharaman et al., 2013; Foster et al., 2018; Han et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2016; Niewoehner and Jinek, 2016; Sheppard et al., 2015). Csm6 and Csx1 ribonucleases do not form stable physical associations with the affiliated effector crRNP complexes (Foster et al., 2018; Hale et al., 2009; Han et al., 2016; Hatoum-Aslan et al., 2014; Staals et al., 2013; Staals et al., 2014), and it is unclear if Csm6 and Csx1 function in trans or are recruited to the effector crRNPs transiently during targeting. Purified recombinant Csm6 (Foster et al., 2018; Han et al., 2016; Jiang et al., 2016; Kazlauskiene et al., 2017; Niewoehner et al., 2017; Niewoehner and Jinek, 2016)} and Csx1 (Elmore et al., 2016; Han et al., 2017; Rouillon et al., 2018) cleave a variety of RNA substrates in vitro and show specificity for cleaving after certain bases. Intriguingly, the RNase activities of Csm6 and Csx1 are stimulated by short cyclic or linear oligoadenylate signaling molecules generated from ATP by the palm domain (with conserved GGDD motif) of the Csm1/Cmr2 (Cas10 superfamily) subunits of Type III effector crRNP complexes upon target RNA recognition (Han et al., 2017; Kazlauskiene et al., 2017; Niewoehner et al., 2017; Rouillon et al., 2018). The conserved N-terminal CARF domains of Csm6 and Csx1 bind the oligoadenylate ligands and allosterically activate the RNase activity (Figure 1) (Han et al., 2017; Kazlauskiene et al., 2017; Niewoehner et al., 2017; Rouillon et al., 2018).

The relatively large Csm1 (III-A) (Jiang et al., 2016; Jung et al., 2015; Kazlauskiene et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017a; Samai et al., 2015) or Cmr2 (III-B) (Elmore et al., 2016; Estrella et al., 2016; Ramia et al., 2014b) protein subunits provide the DNase activity of Type III CRISPR-Cas systems (Figure 1). Csm1 and Cmr2 are members of the Cas10 superfamily (Makarova et al., 2015) that typically harbor HD domains containing the HD DNA nuclease active site (Elmore et al., 2016; Estrella et al., 2016; Han et al., 2016; Jung et al., 2015; Kazlauskiene et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017c; Park et al., 2017) as well as the GGDD motif of the conserved palm domain that functions in the synthesis of the cyclic oligoadenylates that activate the RNase activity of Csm6 (III-A) or Csx1 (III-B) (Foster et al., 2018; Han et al., 2017; Kazlauskiene et al., 2017; Niewoehner et al., 2017).

The pairing of the crRNA to a region of complementarity in the target RNA appears to be sufficient for the ability of Type III-A and III-B effector crRNPs to recognize and destroy target RNAs via the integral Csm3 or Cmr4 RNases positioned along the crRNP backbone of the effector complexes (Figure 1). In contrast, DNA targeting by these same Type III effector complexes is additionally regulated by short protospacer flanking sequences (PFS) located just 3’ of the crRNA complementary sequences of the target RNA. In some systems such as Type III-A (Csm) of Staphylococcus epidermidis or Streptococcus thermophilus, available evidence suggests that 3’ target RNA sequences that are at least partially complementary to the 5’ CRISPR repeat-derived tag sequence inactivate DNA targeting (Kazlauskiene et al., 2016; Marraffini and Sontheimer, 2010; Pyenson et al., 2017). In contrast, 3’ flanking sequences adjacent to the target RNA were shown to be critical in vivo and in vitro for activation of Type III-B (Cmr) DNA cleavage activities of Pyrococcus furious (Elmore et al., 2016). Various Type III subtypes or crRNP variants thus appear to control DNase activities using different strategies. An apparent common strategy for switching off the DNase capability of Type III crRNPs is through destruction and removal of target RNA via the concerted action of the two Type III RNases (e.g., Csm3 and Csm6 (III-A) or Cmr4 and Csx1 (III-B)) described above (Figure 1) (Elmore et al., 2016; Estrella et al., 2016; Foster et al., 2018; Kazlauskiene et al., 2016).

Applied use of Type III Systems

Programmable cleavage of RNA in vitro by Type III crRNPs was demonstrated (Hale et al., 2012) and later was employed for successful knockdown of endogenous gene expression in prokaryotic organisms that naturally contain the systems (Liu et al., 2018; Zebec et al., 2014). Type III systems have already shown utility in interrogating the function of non-essential genes and pathways in prokaryotes analogous to how RNA interference has been used in eukaryotes (Liu et al., 2018; Zebec et al., 2014). Given the complexity of Type III systems (having 6-7 Cas proteins), expressing functional complexes in heterologous organisms and cell types, including mammalian and plant cells, is likely to pose a significant challenge. However, in vivo expression of functional and programmable Type III-A systems has been accomplished in bacteria through co-expression of both the Cas proteins and crRNA from a single plasmid (Ichikawa et al., 2017). Furthermore, protocols have been refined to reconstitute active Type III-A (Foster et al., 2018; Kazlauskiene et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017c; Rouillon et al., 2013; Samai et al., 2015; Staals et al., 2014; Tamulaitis et al., 2014) and Type III-B (Elmore et al., 2016; Estrella et al., 2016; Hale et al., 2012; Hale et al., 2009; Osawa et al., 2015; Rouillon et al., 2013; Spilman et al., 2013; Staals et al., 2013; Taylor et al., 2015) complexes in vitro from purified components. Thus, in vitro assembled Type III crRNPs programmed against specific mRNAs with engineered crRNAs, could be delivered to diverse cell types as ribonucleoprotein (RNPs) via electroporation or microinjection.

The RNA targeting and/or DNA targeting capabilities of Type III systems could be selectively harnessed using effector components with mutations to inactivate the DNase (Csm1/Cmr2; Cas 10 superfamily) or RNase (Cmr4/Csm3; Cas7 superfamily and/or Csx1/Csm6) activities (Table 1 and Figure 1). Regulated RNase destruction in vivo might be accomplished by the Csm6 or Csx1 endoribonuclease through provision of cyclic-oligoadenylate signaling molecules. However, in vitro results indicate that these RNases will indiscriminately destroy cellular RNAs in the absence of their affiliated crRNP effector complexes that use specific crRNAs to find complementary target RNAs. The broad specificity of Csm6 to cleave RNA molecules in vitro has been exploited to amplify signals using a Type VI (Cas13) crRNP-mediated nucleic acid detection and for a diagnostic technique called SHERLOCK (described in more detail below) (Gootenberg et al., 2018; Gootenberg et al., 2017; Myhrvold et al., 2018).

Type II RNA-Targeting Cas9 (RCas9)

CRISPR-Cas9 systems (Class 2, Type II; see Table 1) are the most widely used systems for RNA-programmable gene editing and transcriptional control applications (Hille et al., 2018; Shmakov et al., 2015; Terns and Terns, 2014; Wang et al., 2016; Wright et al., 2016; Xu and Qi, 2018) (Table 1). Cas9 proteins typically target destruction of double-stranded (ds) target DNA through initial PAM recognition, followed by guide RNA base-pairing and ultimately dsDNA cleavage using two nuclease domains (RuvC and HNH) that cut the individual strands of dsDNA (Table 1). Analyses of different Cas9 family members has revealed that some are also capable of targeting RNA (in addition to DNA) (Dugar et al., 2018; O'Connell et al., 2014; Rousseau et al., 2018; Sampson et al., 2013; Strutt et al., 2018).

Applied use of RCas9 Systems

Various RNA-targeting Cas9 (RCas9) systems have been established and recently employed for a variety of novel applications including intracellular transcript imaging (Nelles et al., 2016), gene expression silencing at the post-transcriptional or translational levels (Batra et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2016; Strutt et al., 2018), and combatting RNA virus infection (Price et al., 2015; Strutt et al., 2018).

Early work revealed that purified Streptococcus pyogenes (Spy) Cas9, along with guide RNA, was capable of binding and cleaving single-stranded target RNA provided that a ssDNA oligonucleotide with a PAM sequence (termed PAMmer) was added in vitro (O'Connell et al., 2014). Subsequently, in vivo delivery of guide RNA and a PAMmer was shown to guide a catalytically dead (dCas9) variant (lacking functional RuvC and HNH nuclease active sites) to target RNAs in human cells for programmable RNA tracking and localization (when dCas9/fluorescent fusion proteins were assayed) (Nelles et al., 2016). Likewise, SpyCas9-guide RNA complexes were found to be capable of post-transcriptional destruction of neurodegenerative disease-associated microsatellite expansion repeat RNAs in patient-derived cells (when dCas9/PIN RNA endonuclease domain fusions were employed) (Batra et al., 2017) as well as to repress translation of human mRNAs (when either wild-type or dCas9 was tested) (Liu et al., 2016).

The exact mechanism of action of SpyCas9-guide RNA complexes in eukaryotic cells remains unclear. For example, the majority of the Cas9-mediated effects on reduction of microsatellite expansion repeat RNAs occurred independent of introduced PAMmer, RuvC or HNH Cas9 nuclease domains, or the fusion PIN ribonuclease domain (Batra et al., 2017). These results suggest that binding of the Cas9-guide RNA complex to target RNA is largely responsible for triggering significant phenotypic consequences and raise questions as to how the effects are achieved and which cellular nuclease(s) mediate target RNA destruction (Batra et al., 2017; Nelles et al., 2016).

Cas9 from other bacterial sources have also been characterized and developed for RNA targeting applications. The Francisella novicia (Fno) Cas9 enzyme was found to naturally target an endogenous bacterial mRNA using a unique, small RNA (called scaRNA for small CRISPR-associated RNA) (Sampson et al., 2013). When expressed in a human cell line, FnoCas9 was also capable of RNA-programmable suppression of infection by the hepatitis C RNA virus (Price et al., 2015). Most recently, Cas9 family members from Staphylococcus aureus (SauCas9), Campylobacter jejuni (CjeCas9) and Neisseria menengitidis (NmeCas9) were found to be capable of PAM-independent, single-stranded RNA recognition and cleavage in vitro (Dugar et al., 2018; Rousseau et al., 2018; Strutt et al., 2018)). Programmed SauCas9 exhibited modest protection from single-stranded RNA phages and was able to inhibit reporter gene expression in E. coli (Strutt et al., 2018). CjeCas9 was shown to bind and cleave endogenous RNAs in vivo in a guide-RNA-dependent manner in the natural C. jejuni host (Dugar et al., 2018). RNA targeting by SauCas9, CjeCas9, or NmeCas9 proteins have not yet been tested in human cells.

Several important unresolved issues associated with RCas9 technology remain. These include determining the precise mechanisms of action of the various RCas9 family members in mammalian cells and the degree to which any off-targeting of unintended RNAs or DNAs occurs. Because Cas9 nucleases have evolved to recognize and cleave dsDNA, potential DNA level effects may complicate interpretation of phenotypes observed in eukaryotic cells with RCas9 systems. There is evidence that DNA but not RNA binding by certain Cas9 variants is PAM-dependent (Batra et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2016; Rousseau et al., 2018; Strutt et al., 2018). Thus, one strategy for shifting the binding equilibrium in favor of RNA vs. DNA targets is to choose genomic targets that lack canonical PAMs, but additional work is needed to determine if this approach is sufficient for RNA vs. DNA discrimination by Cas9-guide RNA complexes. Moreover, work needs to be done to better understand and improve the efficacy of RCas9 systems. Relatively modest efficiencies in RNA knockdown and RNA-related gene suppression phenotypes have been reported thus far with RCas9 family members (Batra et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2016; Price et al., 2015; Strutt et al., 2018). In addition, Cas9 cleavage of RNA in vitro and in vivo appears to be confined to exposed or unstructured RNAs (Strutt et al., 2018) which may be a significant limitation for targeting RNAs that have a high degree of secondary or tertiary structure or those bound by RNA binding proteins. Given that Cas9 nucleases evolved to recognize and cleave dsDNA targets, it is conceivable that the relatively modest RNA targeting phenotypes reflect a low intrinsic capability of Cas9 for in vivo RNA binding and cleavage.

Type VI (Cas13) CRISPR-Cas Systems

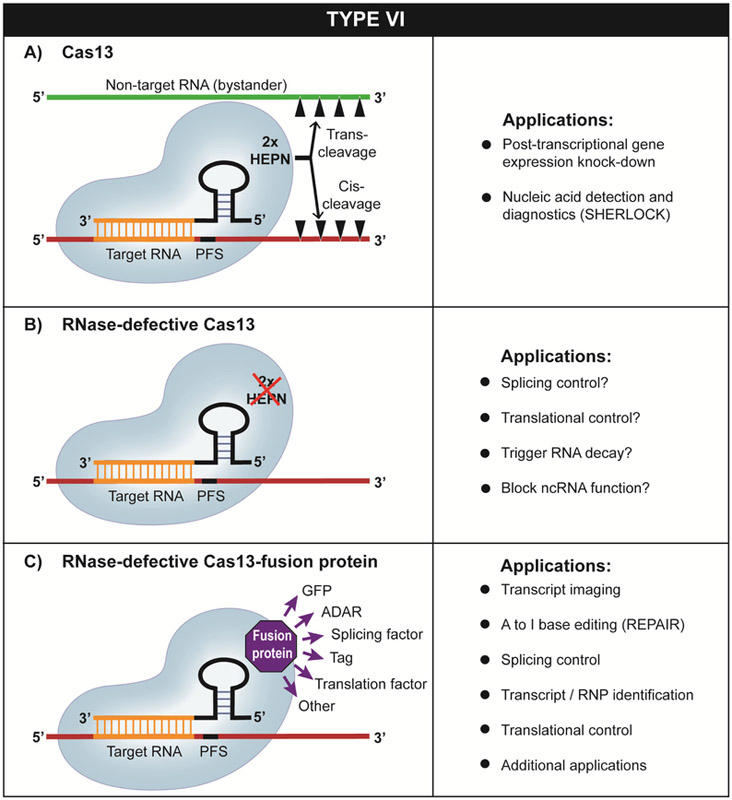

Type VI (Class 2; see Table 1) are the only prokaryotic CRISPR-Cas immune systems known to exclusively target RNA (and not DNA) molecules, and they show particular promise as tools for RNA detection and manipulation (O'Connell, 2018). Type VI effector crRNPs consist of a single Cas13 nuclease in association with a crRNA (Figure 2). A conserved feature of Cas13 is the presence of two HEPN domains that together form a composite RNase active center responsible for catalyzing target RNA cleavage ((East-Seletsky et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017a; Liu et al., 2017b; Shmakov et al., 2015) (Note that the HEPN RNase catalytic motif of Cas13 is also present in the Type III-associated Csm6 and Csx1 endoribonucleases, described above (Figure 1)). Cas13 nucleases contain a separate RNase activity used for processing precursor crRNA into mature crRNA (East-Seletsky et al., 2017; East-Seletsky et al., 2016; Knott et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017b). Four distinct subtypes are recognized (IV-A, B, C and D) based on Cas13 phylogeny and other features including co-occurrence of additional cas genes (e.g., Csx27 or Csx28 (VI-B); WYL domain proteins (IV-D) that encode accessory proteins capable of modulating Cas13-crRNP RNA cleavage activity in a positive or inhibitory manner (Smargon et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2018).

Figure 2.

Type VI CRISPR systems use a single Cas13 effector RNAse and function through targeting the cleavage of RNAs in cis and trans. A) wildtype Cas13-crRNA systems as well as B) RNase-defective (dCas13) systems including C) those with fused effector domains of other proteins support a wide range of established or potential RNA targeting applications.

Similar to Type III CRISPR-Cas systems, the RNase activities of Type VI Cas13-crRNA effector complexes are triggered by target RNA binding and resultant conformational changes in the complex (Knott et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017b; Liu et al., 2018). Activated Cas13-crRNA complexes cleave both the crRNA-bound target RNA (cis-cleavage) as well as (at least in vitro) bystander RNAs (i.e., trans-cleavage of nearby non-target RNA molecules that lack crRNA base-pairing potential) (Figure 2A). The target RNA is cleaved at sites outside of the region where the crRNA binds. Cas13 nucleases all appear to selectively cleave single-stranded (exposed) regions of RNAs which may limit their in vivo cleavage effectiveness to unstructured regions of target RNAs (Abudayyeh et al., 2016; East-Seletsky et al., 2017). Various Cas13 family members exhibit unique specificities for cutting after certain bases (Abudayyeh et al., 2016; East-Seletsky et al., 2017). Different Cas13 variants exhibit different functional requirements for specific target RNA protospacer flanking sequences (PFS) (Abudayyeh et al., 2017; Abudayyeh et al., 2016; East-Seletsky et al., 2016; Gootenberg et al., 2017; Smargon et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2018).

Applied use of Type VI (Cas13) Systems

Although Type VI systems were only recently discovered (Shmakov et al., 2015), the structure and functions of members of the Cas13a (formerly called C2c2 (Shmakov et al., 2015)), Cas13b, and Cas13d families have already been characterized. Moreover, Cas13 systems have already been harnessed as novel research tools for targeted RNA degradation and gene knockdown (Abudayyeh et al., 2017; Abudayyeh et al., 2016; Cox et al., 2017; Konermann et al., 2018), RnA editing (Cox et al., 2017), sensitive nucleic acid detection and patient diagnosis (East-Seletsky et al., 2016; Gootenberg et al., 2018; Gootenberg et al., 2017; Myhrvold et al., 2018), live cell transcript tracking and imaging (Abudayyeh et al., 2017), and pre-mRNA splicing regulation (Konermann et al., 2018). Both wildtype Cas13 and RNase-defective dCas13 and dCas13-effector fusion variants have been developed and put to task to support these important applications (Figure 2).

In vitro applications: Use of Cas13 for sensitive nucleic acid detection and diagnostics.

The capacity of activated Cas13-crRNA complexes to promiscuously cleave adjacent bystander RNAs (non-complementary to crRNA) upon target RNA binding was cleverly leveraged for the establishment of a sensitive and robust nucleic acid detection platform and powerful diagnostic tool for clinical and environmental samples (East-Seletsky et al., 2016; Gootenberg et al., 2018; Gootenberg et al., 2017; Myhrvold et al., 2018). A particularly promising Cas13-based nucleic acid detection platform, dubbed SHERLOCK (for Specific High Sensitivity Enzymatic Reporter UnLOCKing), is capable of rapid, highly sensitive (single molecule/μL) and precise (single nucleotide discrimination) detection of specific target RNAs or DNAs within complex mixtures including patient blood and saliva samples (Gootenberg et al., 2018; Gootenberg et al., 2017; Myhrvold et al., 2018). Specific target nucleic acid molecules are detected indirectly through monitoring target RNA-activated, Cas13 trans-cleavage of reporter bystander RNA (generating either fluorescent or colorimetric signals).

Early applications for the SHERLOCK assay include detection of nucleic acid signatures of specific viral strains and distinct pathogenic bacterial species as well as human cancer-associated DNA mutations. The sensitivity and versatility of this Cas13-based molecular diagnostic platform was further boosted through inclusion of Type III-A Csm6 ssRNAses and Type V Cas12 ssDNases that also demonstrate target rna or DNA-dependent trans-cleavage of reporters, respectively (Chen et al., 2018; Gootenberg et al., 2018; Gootenberg et al., 2017). Other refinements of the technology that make diagnostic tests practical and cost-effective include a new procedure for preparing clinical samples with preserved nucleic acid integrity (called HUDSON for Heating Unextracted Diagnostic Samples to Obliterate Nucleases) and establishment of a colorimetric readout of specific nucleic acids (similar to strip tests used to determine pregnancy) (Myhrvold et al., 2018). The breadth of potential applications for the new Cas13-based nucleic acid diagnostic platform is enormous. For example, standardized tests for various viral and pathogenic bacteria may enhance the rate of clinical decision making and point of care patient treatments.

In vivo applications: Cas13-mediated gene expression knockdown and site-specific RNA editing in bacterial and mammalian cells.

For a number of reasons, Cas13 (Type VI)-based technologies are particularly promising as a system of choice for in vivo detection and manipulation of RNAs for a wide range of RNA targeting applications. The relative simplicity of the Cas13 system (one Cas13 effector protein and a single crRNA versus the multiple Cas proteins needed for Type III RNA-targeting systems) has greatly facilitated their rapid development. Furthermore, Cas13 systems naturally target RNA whereas RNA targeting with Cas9-based systems is complicated by the fact that these systems have evolved to bind and cleave target DNA molecules. In addition, the natural functional diversity among Cas13 subtypes (Table 1) from various prokaryotic sources has provided a collection of tools with ideal properties for supporting the wide range of in vivo RNA targeting applications.

The RNA cleavage capacity of Cas13-based systems in human cells (Abudayyeh et al., 2017; Cox et al., 2017; Konermann et al., 2018) and improved targeting specificity over current RNA interference (RNAi) platforms (Abudayyeh et al., 2017; Konermann et al., 2018) are predicted to greatly enhance our knowledge of gene function, to provide a facile way to alter cellular pathways, and conceivably may lead to novel human therapeutic agents (e.g. controlling viral infection or genetic disease via control at the post-transcriptional level). The dCas13 platform in which HEPN endoribonuclease function is ablated to permit programmable RNA binding without RNA cleavage and destruction (Figure 2B) has already been shown to be effective (Abudayyeh et al., 2017; Cox et al., 2017; Konermann et al., 2018). Further refinement and innovations will likely greatly expand RNA targeting applications to include inhibitors or activators of pre-mRNA splicing or translation and inhibitors of mRNA and non-coding RNA function according to the location where they interact on the transcripts (Figure 2B).

Fusing various effector protein domains to dCas13 to expand the functionality of Cas13 beyond RNA cleavage (Figure 2C) has already been shown to be an effective strategy. For example, A to I (adenosine to inosine) RNA editing (via fusion of ADAR (Adenosine deamination of RNA) enzyme domain) resulted in repair of disease-associated G to A nonsense RNA mutations given that inosine is recognized as guanosine during translation (Cox et al., 2017). (The newly established RNA editing technology was dubbed REPAIR, for RNA Editing for Programmable A to I Replacement). Other site-specific base (e.g. C to U) or ribose modifications (e.g. 2’-O-methylation) are likely to follow using this basic approach. Moreover, patterns of alternative splicing and thereby expression of specific protein isoforms have been predictably altered through fusion of dCas13d with a domain of a known splicing regulator (hnRNPA) (Konermann et al., 2018). The use of epitope/affinity tagged dCas13 variants has the potential to have a large impact on RNA biology by providing a specific way to isolate and characterize specific RNAs and associated RNA-binding proteins. A whole new class of Cas13-based, “ribo-regulators” capable of predictably up- or down-regulating protein production or ncRNA activity through selectively manipulating RNA stability, splicing, intracellular localization, translation, etc. is expected from current and future Cas13-based research tools.

Future Prospects for RNA-Targeting CRISPR-based tools.

RNA programmable, Type II (RCas9), Type III (Csm and Cmr), and Type VI (Cas13) CRISPR-Cas systems have only recently emerged as tractable tools for conducting research. These RNA targeting, CRISPR-based tools have created new opportunities and significantly broadened the number of applications beyond those possible with established conventional DNA-targeting CRISPR-based technologies alone. For example, use of RNA cleaving CRISPR-Cas systems as a platform for RNA interference or gene knockdown can enable the study of the function of essential genes that are lethal when the gene is knocked out by DNA-editing and gene knockout approaches. Also, a concern with DNA-mediated CRISPR-based gene editing (for basic research or therapeutic applications) is the potential for permanent off-target (unintended) genetic changes following DNA base editing or DNA cutting and repair. In contrast, RNA-level effects are limited to the natural half-lives of RNA targets (mRNAs are rapidly turned over following synthesis in mammalian cells) and in theory are fully reversible.

RNA molecules play key and pervasive roles in normal cellular processes as well as disease states. Future use of CRISPR-based RNA-targeting systems is expected to significantly advance our understanding of the impact of RNA biology on important life processes including fundamental cellular function, tissue differentiation, and organismal development, etc. The CRISPR-based RNA targeting research tools should enable the biological roles of specific protein-coding (mRNA) and noncoding RNA molecules (e.g., lncRNAs) to be dissected and for identification of target RNA-binding proteins that help mediate RNA functionality. The new RNA-targeting CRISPR-based tools have already been harnessed for important biomedical applications (e.g., Cas13-based diagnostics of viruses, pathogenic bacteria, and cancer mutations in patients (East-Seletsky et al., 2016; Gootenberg et al., 2018; Gootenberg et al., 2017; Myhrvold et al., 2018)). Numerous other potential applications remain, given that a wide range of human genetic diseases result from specific mutations in genes as well as abnormal pre-mRNA splicing patterns. Both currently established and future CRISPR-based RNA targeting systems hold exciting potential to serve as novel therapeutic agents for the treatment of a wide range of human infectious and genetic diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R35GM118160 to Michael Terns

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

The author has CRISPR-related patents.

CRISPR-Cas immune systems protect prokaryotes from viruses and provide powerful research tools for important biotechnology and biomedical applications. Michael Terns reviews specific CRISPR-Cas systems known to naturally bind and cleave RNA molecules and summarizes applications of emerging technologies centered on RNA targeting CRISPR-based systems.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abudayyeh OO, Gootenberg JS, Essletzbichler P, Han S, Joung J, Belanto JJ, Verdine V, Cox DBT, Kellner MJ, Regev A, et al. (2017). RNA targeting with CRISPR-Cas13. Nature 550, 280–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abudayyeh OO, Gootenberg JS, Konermann S, Joung J, Slaymaker IM, Cox DB, Shmakov S, Makarova KS, Semenova E, Minakhin L, et al. (2016). C2c2 is a single-component programmable RNA-guided RNA-targeting CRISPR effector. Science 353, aaf5573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anantharaman V, Makarova KS, Burroughs AM, Koonin EV, and Aravind L (2013). Comprehensive analysis of the HEPN superfamily: identification of novel roles in intra-genomic conflicts, defense, pathogenesis and RNA processing. Biology direct 8,15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batra R, Nelles DA, Pirie E, Blue SM, Marina RJ, Wang H, Chaim IA, Thomas JD, Zhang N, Nguyen V, et al. (2017). Elimination of Toxic Microsatellite Repeat Expansion RNA by RNA-Targeting Cas9. Cell 170, 899–912 e810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benda C, Ebert J, Scheltema RA, Schiller HB, Baumgartner M, Bonneau F, Mann M, and Conti E (2014). Structural model of a CRISPR RNA-silencing complex reveals the RNA-target cleavage activity in Cmr4. Molecular cell 56, 43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L, Gao CH, Zhu J, Zhao L, Wu Q, Li M, and Sun B (2016). Identification and functional study of type III-A CRISPR-Cas systems in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. International journal of medical microbiology : IJMM 306, 686–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JS, Ma E, Harrington LB, Da Costa M, Tian X, Palefsky JM, and Doudna JA (2018). CRISPR-Cas12a target binding unleashes indiscriminate single-stranded DNase activity. Science. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DBT, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Franklin B, Kellner MJ, Joung J, and Zhang F (2017). RNA editing with CRISPR-Cas13. Science 358, 1019–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L, Garrett RA, Shah SA, Peng X, and She Q (2013). A novel interference mechanism by a type IIIB CRISPR-Cmr module in Sulfolobus. Molecular microbiology 87, 1088–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugar G, Leenay RT, Eisenbart SK, Bischler T, Aul BU, Beisel CL, and Sharma CM (2018). CRISPR RNA-Dependent Binding and Cleavage of Endogenous RNAs by the Campylobacter jejuni Cas9. Molecular cell 69, 893–905 e897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East-Seletsky A, O'Connell MR, Burstein D, Knott GJ, and Doudna JA (2017). RNA Targeting by Functionally Orthogonal Type VI-A CRISPR-Cas Enzymes. Molecular cell 66, 373–383 e373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East-Seletsky A, O'Connell MR, Knight SC, Burstein D, Cate JH, Tjian R, and Doudna JA (2016). Two distinct RNase activities of CRISPR-C2c2 enable guide-RNA processing and RNA detection. Nature 538, 270–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore JR, Sheppard NF, Ramia N, Deighan T, Li H, Terns RM, and Terns MP (2016). Bipartite recognition of target RNAs activates DNA cleavage by the Type III-B CRISPR-Cas system. Genes & development 30, 447–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrella MA, Kuo FT, and Bailey S (2016). RNA-activated DNA cleavage by the Type III-B CRISPR-Cas effector complex. Genes & development 30, 460–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster K, Kalter J, Woodside W, Terns RM, and Terns MP (2018). The ribonuclease activity of Csm6 is required for anti-plasmid immunity by Type III-A CRISPR-Cas systems. RNA Biol, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg GW, Jiang W, Bikard D, and Marraffini LA (2014). Conditional tolerance of temperate phages via transcription-dependent CRISPR-Cas targeting. Nature. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Kellner MJ, Joung J, Collins JJ, and Zhang F (2018). Multiplexed and portable nucleic acid detection platform with Cas13, Cas12a, and Csm6. Science. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Lee JW, Essletzbichler P, Dy AJ, Joung J, Verdine V, Donghia N, Daringer NM, Freije CA, et al. (2017). Nucleic acid detection with CRISPR-Cas13a/C2c2. Science 356, 438–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale CR, Cocozaki A, Li H, Terns RM, and Terns MP (2014). Target RNA capture and cleavage by the Cmr type III-B CRISPR-Cas effector complex. Genes & development 28, 2432–2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale CR, Majumdar S, Elmore J, Pfister N, Compton M, Olson S, Resch AM, Glover CV 3rd, Graveley BR, Terns RM, et al. (2012). Essential features and rational design of CRISPR RNAs that function with the Cas RAMP module complex to cleave RNAs. Molecular cell 45, 292–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale CR, Zhao P, Olson S, Duff MO, Graveley BR, Wells L, Terns RM, and Terns MP (2009). RNA-guided RNA cleavage by a CRISPR RNA-Cas protein complex. Cell 139, 945–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W, Li Y, Deng L, Feng M, Peng W, Hallstrom S, Zhang J, Peng N, Liang YX, White MF, et al. (2016). A type III-B CRISPR-Cas effector complex mediating massive target DNA destruction. Nucleic acids research. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W, Pan S, Lopez-Mendez B, Montoya G, and She Q (2017). Allosteric regulation of Csx1, a type IIIB-associated CARF domain ribonuclease by RNAs carrying a tetraadenylate tail. Nucleic acids research 45, 10740–10750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatoum-Aslan A, Maniv I, Samai P, and Marraffini LA (2014). Genetic characterization of antiplasmid immunity through a type III-A CRISPR-Cas system. Journal of bacteriology 196, 310–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatoum-Aslan A, Samai P, Maniv I, Jiang W, and Marraffini LA (2013). A ruler protein in a complex for antiviral defense determines the length of small interfering CRISPR RNAs. The Journal of biological chemistry 288, 27888–27897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille F, Richter H, Wong SP, Bratovic M, Ressel S, and Charpentier E (2018). The Biology of CRISPR-Cas: Backward and Forward. Cell 172, 1239–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa HT, Cooper JC, Lo L, Potter J, Terns RM, and Terns MP (2017). Programmable type III-A CRISPR-Cas DNA targeting modules. PloS one 12, e0176221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson RN, van Erp PB, Sternberg SH, and Wiedenheft B (2017). Conformational regulation of CRISPR-associated nucleases. Current opinion in microbiology 37, 110–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Samai P, and Marraffini LA (2016). Degradation of Phage Transcripts by CRISPR-Associated RNases Enables Type III CRISPR-Cas Immunity. Cell 164, 710–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung TY, An Y, Park KH, Lee MH, Oh BH, and Woo E (2015). Crystal Structure of the Csm1 Subunit of the Csm Complex and Its Single-Stranded DNA-Specific Nuclease Activity. Structure 23, 782–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazlauskiene M, Kostiuk G, Venclovas C, Tamulaitis G, and Siksnys V (2017). A cyclic oligonucleotide signaling pathway in type III CRISPR-Cas systems. Science. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazlauskiene M, Tamulaitis G, Kostiuk G, Venclovas C, and Siksnys V (2016). Spatiotemporal Control of Type III-A CRISPR-Cas Immunity: Coupling DNA Degradation with the Target RNA Recognition. Molecular cell 62, 295–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott GJ, East-Seletsky A, Cofsky JC, Holton JM, Charles E, O'Connell MR, and Doudna JA (2017). Guide-bound structures of an RNA-targeting A-cleaving CRISPR-Cas13a enzyme. Nature structural & molecular biology 24, 825–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konermann S, Lotfy P, Brideau NJ, Oki J, Shokhirev MN, and Hsu PD (2018). Transcriptome Engineering with RNA-Targeting Type VI-D CRISPR Effectors. Cell 173, 665–676 e614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leenay RT, Maksimchuk KR, Slotkowski RA, Agrawal RN, Gomaa AA, Briner AE, Barrangou R, and Beisel CL (2016). Identifying and Visualizing Functional PAM Diversity across CRISPR-Cas Systems. Molecular cell 62, 137–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Li X, Ma J, Li Z, You L, Wang J, Wang M, Zhang X, and Wang Y (2017a). The Molecular Architecture for RNA-Guided RNA Cleavage by Cas13a. Cell. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Li X, Wang J, Wang M, Chen P, Yin M, Li J, Sheng G, and Wang Y (2017b). Two Distant Catalytic Sites Are Responsible for C2c2 RNase Activities. Cell 168, 121–134 e112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Pan S, Li Y, Peng N, and She Q (2018). Type III CRISPR-Cas System: Introduction And Its Application for Genetic Manipulations. Current issues in molecular biology 26, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu TY, Iavarone AT, and Doudna JA (2017c). RNA and DNA Targeting by a Reconstituted Thermus thermophilus Type III-A CRISPR-Cas System. PloS one 12, e0170552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Chen Z, He A, Zhan Y, Li J, Liu L, Wu H, Zhuang C, Lin J, Zhang Q, et al. (2016). Targeting cellular mRNAs translation by CRISPR-Cas9. Scientific reports 6, 29652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Alkhnbashi OS, Costa F, Shah SA, Saunders SJ, Barrangou R, Brouns SJ, Charpentier E, Haft DH, et al. (2015). An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems. Nature reviews Microbiology 13, 722–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marraffini LA, and Sontheimer EJ (2008). CRISPR interference limits horizontal gene transfer in staphylococci by targeting DNA. Science 322, 1843–1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marraffini LA, and Sontheimer EJ (2010). Self versus non-self discrimination during CRISPR RNA-directed immunity. Nature 463, 568–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millen AM, Horvath P, Boyaval P, and Romero DA (2012). Mobile CRISPR/Cas-mediated bacteriophage resistance in Lactococcus lactis. PloS one 7, e51663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myhrvold C, Freije CA, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Metsky HC, Durbin AF, Kellner MJ, Tan AL, Paul LM, Parham LA, et al. (2018). Field-deployable viral diagnostics using CRISPR-Cas13. Science 360, 444–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelles DA, Fang MY, O'Connell MR, Xu JL, Markmiller SJ, Doudna JA, and Yeo GW (2016). Programmable RNA Tracking in Live Cells with CRISPR/Cas9. Cell 165, 488–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niewoehner O, Garcia-Doval C, Rostol JT, Berk C, Schwede F, Bigler L, Hall J, Marraffini LA, and Jinek M (2017). Type III CRISPR-Cas systems produce cyclic oligoadenylate second messengers. Nature 548, 543–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niewoehner O, and Jinek M (2016). Structural basis for the endoribonuclease activity of the type III-A CRISPR-associated protein Csm6. RNA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell M (2018). Molecular Mechanisms of RNA-Targeting by Cas13-containing Type VI CRISPR-Cas Systems. Journal of molecular biology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell MR, Oakes BL, Sternberg SH, East-Seletsky A, Kaplan M, and Doudna JA (2014). Programmable RNA recognition and cleavage by CRISPR/Cas9. Nature 516, 263–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osawa T, Inanaga H, Sato C, and Numata T (2015). Crystal Structure of the CRISPR-Cas RNA Silencing Cmr Complex Bound to a Target Analog. Molecular cell 58, 418–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KH, An Y, Jung TY, Baek IY, Noh H, Ahn WC, Hebert H, Song JJ, Kim JH, Oh BH, et al. (2017). RNA activation-independent DNA targeting of the Type III CRISPR-Cas system by a Csm complex. EmBo reports 18, 826–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price AA, Sampson TR, Ratner HK, Grakoui A, and Weiss DS (2015). Cas9-mediated targeting of viral RNA in eukaryotic cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112, 6164–6169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyenson NC, Gayvert K, Varble A, Elemento O, and Marraffini LA (2017). Broad Targeting Specificity during Bacterial Type III CRISPR-Cas Immunity Constrains Viral Escape. Cell host & microbe 22, 343–353 e343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramia NF, Spilman M, Tang L, Shao Y, Elmore J, Hale C, Cocozaki A, Bhattacharya N, Terns RM, Terns MP, et al. (2014a). Essential structural and functional roles of the Cmr4 subunit in RNA cleavage by the Cmr CRISPR-Cas complex. Cell reports 9, 1610–1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramia NF, Tang L, Cocozaki AI, and Li H (2014b). Staphylococcus epidermidis Csm1 is a 3'-5' exonuclease. Nucleic acids research 42, 1129–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouillon C, Athukoralage JS, Graham S, Gruschow S, and White MF (2018). Control of cyclic oligoadenylate synthesis in a type III CRISPR system. eLife 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouillon C, Zhou M, Zhang J, Politis A, Beilsten-Edmands V, Cannone G, Graham S, Robinson CV, Spagnolo L, and White MF (2013). Structure of the CRISPR interference complex CSM reveals key similarities with cascade. Molecular cell 52, 124–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau BA, Hou Z, Gramelspacher MJ, and Zhang Y (2018). Programmable RNA Cleavage and Recognition by a Natural CRISPR-Cas9 System from Neisseria meningitidis. Molecular cell 69, 906–914 e904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samai P, Pyenson N, Jiang W, Goldberg GW, Hatoum-Aslan A, and Marraffini LA (2015). Co-transcriptional DNA and RNA Cleavage during Type III CRISPR-Cas Immunity. Cell 161, 1164–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson TR, Saroj SD, Llewellyn AC, Tzeng YL, and Weiss DS (2013). A CRISPR/Cas system mediates bacterial innate immune evasion and virulence. Nature 497, 254–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard NF, Glover CV 3rd, Terns RM, and Terns MP (2015). The CRISPR-associated Csx1 protein of Pyrococcus furiosus is an adenosine-specific endoribonuclease. RNA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmakov S, Abudayyeh OO, Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Gootenberg JS, Semenova E, Minakhin L, Joung J, Konermann S, Severinov K, et al. (2015). Discovery and Functional Characterization of Diverse Class 2 CRISPR-Cas Systems. Molecular cell 60, 385–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smargon AA, Cox DB, Pyzocha NK, Zheng K, Slaymaker IM, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OA, Essletzbichler P, Shmakov S, Makarova KS, et al. (2017). Cas13b Is a Type VI-B CRISPR-Associated RNA-Guided RNase Differentially Regulated by Accessory Proteins Csx27 and Csx28. Molecular cell 65, 618–630 e617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spilman M, Cocozaki A, Hale C, Shao Y, Ramia N, Terns R, Terns M, Li H, and Stagg S (2013). Structure of an RNA silencing complex of the CRISPR-Cas immune system. Molecular cell 52, 146–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staals RH, Agari Y, Maki-Yonekura S, Zhu Y, Taylor DW, van Duijn E, Barendregt A, Vlot M, Koehorst JJ, Sakamoto K, et al. (2013). Structure and activity of the RNA-targeting Type III-B CRISPR-Cas complex of Thermus thermophilus. Molecular cell 52, 135–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staals RH, Zhu Y, Taylor DW, Kornfeld JE, Sharma K, Barendregt A, Koehorst JJ, Vlot M, Neupane N, Varossieau K, et al. (2014). RNA targeting by the type III-A CRISPR-Cas Csm complex of Thermus thermophilus. Molecular cell 56, 518–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt SC, Torrez RM, Kaya E, Negrete OA, and Doudna JA (2018). RNA-dependent RNA targeting by CRISPR-Cas9. eLife 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamulaitis G, Kazlauskiene M, Manakova E, Venclovas C, Nwokeoji AO, Dickman MJ, Horvath P, and Siksnys V (2014). Programmable RNA shredding by the type III-A CRISPR-Cas system of Streptococcus thermophilus. Molecular cell 56, 506–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DW, Zhu Y, Staals RH, Kornfeld JE, Shinkai A, van der Oost J, Nogales E, and Doudna JA (2015). Structures of the CRISPR-Cmr complex reveal mode of RNA target positioning. Science. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terns RM, and Terns MP (2014). CRISPR-based technologies: prokaryotic defense weapons repurposed. Trends in genetics : TIG 30, 111–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Huang X, Fang X, Zhang Y, and Wang W (2016). CRISPR-Cas9 System as a Versatile Tool for Genome Engineering in Human Cells. Molecular therapy Nucleic acids 5, e388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AV, Nunez JK, and Doudna JA (2016). Biology and Applications of CRISPR Systems: Harnessing Nature's Toolbox for Genome Engineering. Cell 164, 29–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, and Qi LS (2018). A CRISPR-dCas Toolbox for Genetic Engineering and Synthetic Biology. Journal of molecular biology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan WX, Chong S, Zhang H, Makarova KS, Koonin EV, Cheng DR, and Scott DA (2018). Cas13d Is a Compact RNA-Targeting Type VI CRISPR Effector Positively Modulated by a WYL-Domain-Containing Accessory Protein. Molecular cell 70, 327–339 e325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebec Z, Manica A, Zhang J, White MF, and Schleper C (2014). CRISPR-mediated targeted mRNA degradation in the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. Nucleic acids research 42, 5280–5288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Rouillon C, Kerou M, Reeks J, Brugger K, Graham S, Reimann J, Cannone G, Liu H, Albers SV, et al. (2012). Structure and mechanism of the CMR complex for CRISPR-mediated antiviral immunity. Molecular cell 45, 303–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, and Ye K (2015). Cmr4 is the slicer in the RNA-targeting Cmr CRISPR complex. Nucleic acids research 43, 1257–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]