Younger women experience greater chemotherapy related toxicities compared to older counterparts,1 and with a longer natural lifespan, have more time for toxicities to arise. Studies have reported that younger women have distinct psychosocial and menopausal concerns1 and report steeper declines in mental health and social and sexual functioning compared to older women.2 “Very young breast cancer survivors” are typically defined as women less than 50, or in some studies, less than 40.1 Little is known about the experiences and unique needs of young adult women in their 20s who have undergone BC treatment. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to explore the unique experiences of survivors who were diagnosed and treated for BC while in their 20s.

A qualitative, collective case study approach was adopted for this study. The University of Texas at Austin IRB reviewed all study procedures. Purposive recruitment was used to recruit women in their 20’s with a history of non-metastatic, non-inflammatory breast cancer, stages I-III, with chemotherapy as part of the treatment history (6 months to 10 years prior) were included. Semi-structured interviews were conducted, audio recorded and transcribed. Data were analyzed using qualitative content analysis as described by Sandelowski.3,4 The researchers discussed and compared their descriptive codes and came to a consensus on the emerging categories and integrated these categories into a descriptive conceptual map.

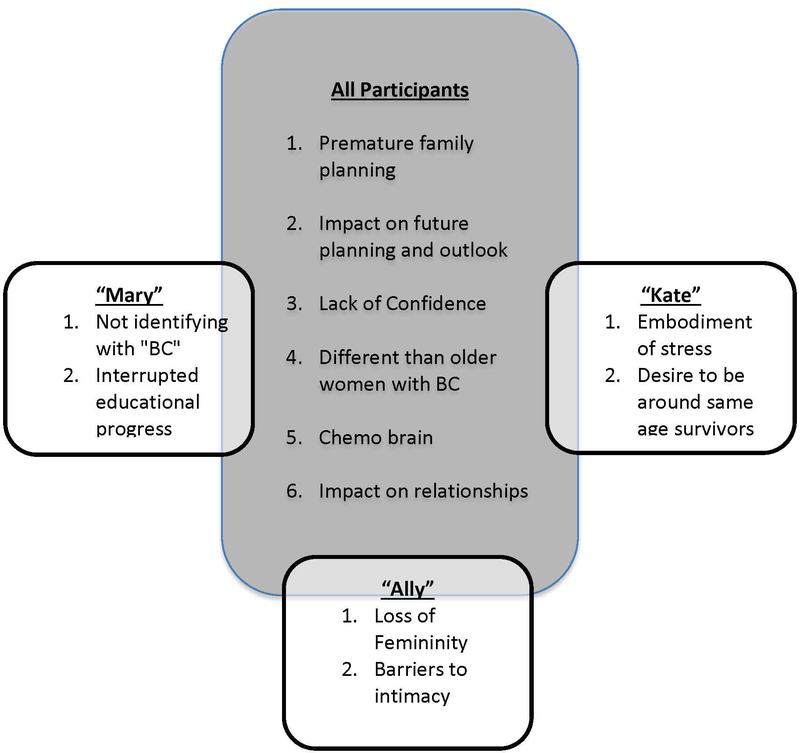

Participants’ real names were not used. The demographics of the three participants, are displayed in Table 1. Below are the major categories that emerged are displayed in a concept map in Figure 1. All women expressed that they needed to make complicated and serious decisions regarding their “future families” in the midst of receiving their cancer diagnoses. The women expressed how BC seriously impacted their future planning and outlook on life. The women also expressed how their outlook on life shifted to a more positive one. On the other hand, the women also expressed how BC had instilled a sense of fear of the future—fear of recurrence, anxiety, and a “hypochondriac-like” awareness of their bodies.

Table 1.

Demographic and Treatment History of each Participant

| Mary | Kate | Ally | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 28 | 24 | 27 |

| BC Type | IDC | IDC | IDC |

| Stage | 3a | 3c | 3a |

| Receptor St | ER+/PR+/HER2+ | ER-/Pr-/HER+ | ER+/PR+/HER2+ |

| Treatment | Rx, Db Mast., Doxorubicin chemo | Db Mast.,Taxol chemo | Rx, Db Mast., Doxorubicin chemo |

| Yrs Education | 15 | 16.5 | 16.5 |

| Employment | Full time | Full time | Full time |

| Ethnicity | White/Hispanic | White/Non-Hispanic | White/Non-Hispanic |

Note: IDC: invasive ductal carcinoma; ER: estrogen; PR: progesterone; HER2: human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; Rx: radiation therapy; Db Mast: double mastectomy; chemo: chemotherapy treatment

Figure 1.

The conceptual map includes the categories that emerged across all participants and those unique categories that emerged for each individual’s interview. In the center block are the categories that emerged across all the participants including premature family planning, impact on future planning and outlook, lack of confidence, different than older women with BC, chemo brain, impact on relationships. The peripheral blocks illustrate the categories that emerged for each individual participant. For Mary the categories of not identifying with breast cancer emerged; for Ally the categories of loss of femininity and barriers to intimacy emerged; and for Kate the categories of embodiment of stress and desire to be around same age survivors emerged.

The women expressed how their BC experience negatively impacted their confidence and made them feel insecure. The participants expressed that their BC experience was different from women with BC in their 30s and older. All three talked about the difficulty of being a young person and navigating such a complex health issue. Difficulty with cognitive functioning both during and following the end of treatment was common and these problems occurred primarily in a work. BC impacted various relationships for the participants in both positive and negative ways. Two additional unique categories were identified for each of the three participants and are displayed in Figure 1. Mary’s treatment effects caused her to drop out of her bachelor’s program. Kate discussed how stress manifests in her body since her diagnosis and importance of connecting with other survivors her age. Ally discussed the “loss of femininity” and “barriers to intimacy.”

The participants in the study all moved back in with their families to be taken care of during their treatment, and put developmental life stages like education, marriage, and children on hold. Nolan et al.5 explain that cancer during this developmental time period can seriously disrupt attaining developmental milestones and puts this population at greater risk for poorer quality of life than survivors at more stable developmental stages of life. All the women in this study described distress surrounding fertility and family planning related to their breast cancer treatment, which is consistent with other research.6 Decisions surrounding fertility have lifelong implications and need to be prioritized as much as treatment.

All women discussed how BC had a positive influence on their close relationships beyond partners and family members. Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) survivors value relationships with friends and extended family members.7 The study findings highlight the need for close monitoring of stress and anxiety in younger women who may not have the “life experience” to adequately cope and thrive as they continue their adult development. Importantly, the development of complex executive functioning typically occurs during adolescence and early adulthood making young adults especially vulnerable to cancer related cognitive changes,8 such as those described by the participants in this study. A loss of femininity and intimacy challenges emerged from the women in this study. BC at any age can elicit similar challenges, yet women in their 20’s are just entering womanhood and have not had the opportunity to solidify their adult femininity and sexuality. Most providers are either uncomfortable or lack education about sexual health and typically do not ask about sex and intimacy.9

Young women can experience BC as early as late teens to early twenties. Developmentally, these women are at different life stages than the majority of BC patients and their unique experiences and needs should be recognized. Clinicians need to be sensitive to issues surrounding fertility, cognition, and body image that impact this population. The unique experiences of young women can lead to intense self-doubt, cognitive challenges, and anxiety. It is imperative the clinicians provide upfront education and support to adequately prepare these young women during their BC journey. The perceived challenges can negatively impact their personal growth into adulthood and clinicians should be sensitive to the fact that their needs may be drastically different than older women with BC women and that younger BC patients may benefit from referrals to AYA support groups or counselors.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under award number 1F31NR015707–01A. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Ashley M. Henneghan was supported by the Doctoral Degree Scholarship in Cancer Nursing, DSCN-15–072-01 from the American Cancer Society.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest Statement

Ashley Henneghan and Carolyn Phillips report no conflicts of interest. Anne Courtney gives educational presentations for Eisai, Inc.

References

- 1.Howard-Anderson J, Ganz PA, Bower JE, Stanton AL. Quality of life, fertility concerns, and behavioral health outcomes in younger breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012; 10415): 386–405. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gewefel H, Salhia B. Breast cancer in adolescent and young adult women. Clinical breast cancer. 2014;14:390–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandelowski M (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23(4), 334–340. doi:10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandelowski M (2011). When a cigar is not just a cigar: Alternative takes on data and data analysis. Research in Nursing & Health, 34(4), 342–352. doi:10.1002/nur.20437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nolan VG, Krull KR, Gurney JG, et al. Predictors of future health-related quality of life in survivors of adolescent cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(10):1891–1894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canada AL, Schover LR. The psychosocial impact of interrupted childbearing in long‐term female cancer survivors. Psycho‐Oncology. 2012;21:134–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brandão T, Schulz MS, & Matos PM (2014). Psychological intervention with couples coping with breast cancer: A systematic review. Psychology & Health, 29(5), 491–516. doi:10.1080/08870446.2013.859257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.John TD, Sender LS, & Bota DA (2016). Cognitive impairment in survivors of adolescent and early young adult onset non-CNS cancers: Does chemotherapy play a role? Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 5(3), 226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dizon DS, Suzin D, & McIlvenna S (2014). Sexual health as a survivorship issue for female cancer survivors. The Oncologist, 19(2), 202–210. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]