Abstract

Background

Minimally invasive hysterectomy is now routinely used for women with uterine cancer. Most studies of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) for endometrial cancer have focused on low-risk, endometrioid tumors with few reports of the safety of the procedure for women with higher risk histologic subtypes.

Objective

To examine the utilization and survival associated with minimally invasive hysterectomy for women with uterine cancer and high-risk histologic subtypes.

Study Design

We used the National Cancer Database was used to identify women with stages I-III uterine cancer who underwent hysterectomy from 2010-2014. Women with serous, clear cell carcinomas and sarcomas were examined. Women who had laparoscopic or robotic-assisted hysterectomy were compared to those who underwent open abdominal hysterectomy. After a propensity score inverse probability of treatment weighted analysis, the effect of MIS hysterectomy on overall, 30-day, and 90-day mortality was examined for each histologic subtype of uterine cancer.

Results

Of 94,507 patients identified, 64,417 (68.2%) underwent minimally invasive hysterectomy. Among women with endometrioid tumors (n=81,115), 70.8% underwent MIS hysterectomy. The rates of MIS in those with non-endometrioid tumors (n=13,392) was 57.6% for serous carcinomas, 57.0% for clear cell tumors, 47.3% for sarcomas, 32.2% for leiomyosarcomas, 47.9% for stromal sarcomas and 48.5% for carcinosarcomas. Performance of MIS increased across all histologic subtypes between 2010 and 2014. For non-endometrioid subtypes, robotic-assisted procedures accounted for 47.9%-75.7% of MIS hysterectomies by 2014. In a multivariable model, women with non-endometrioid tumors were less likely to undergo MIS than those with endometrioid tumors (P<0.05). There was no association between route of surgery and 30-day, 90-day, or overall mortality for any of the non-endometrioid histologic subtypes.

Conclusions

The use of minimally invasive surgery is increasing rapidly for women with stage I-III non-endometrioid uterine tumors. Performance of minimally invasive surgery does not appear to adversely impact survival.

Condensation

The use of minimally invasive surgery for women with stage I-III non-endometrioid uterine tumors does not appear to adversely impact survival.

Keywords: Endometrial cancer, uterine cancer, hysterectomy, laparoscopic hysterectomy, robotic hysterectomy

Introduction

Minimally invasive hysterectomy has become the preferred surgical approach for the treatment of women with early-stage uterine cancer.1-8 Compared to laparotomy, minimally invasive hysterectomy is associated with fewer complications, less postoperative pain and bleeding, and a shorter length of stay.4,9,10 From an oncologic standpoint, several randomized controlled trials and large observational studies have shown that long term outcomes and survival after minimally invasive hysterectomy are not inferior to abdominal hysterectomy.1-3

Given the benefits of minimally invasive hysterectomy, the procedure has become the standard of care for endometrial cancer.1-3 Use of minimally invasive hysterectomy for early-stage endometrial cancer has been proposed as a quality metric and population-based data have suggested that uptake of the procedure has been increasing rapidly.11 However, despite these benefits, most studies of minimally invasive hysterectomy have focused on women with low-risk endometrial tumors. Patients with high-risk histologic subtypes have been excluded from many trials or represent only a small number of subjects in other studies.2,10

Theoretically, performance of minimally invasive surgery in women with high-risk histologic subtypes has a number of concerns. These patients often have larger tumors and uteri and are at higher risk for dissemination beyond the uterus. As such, women with high-risk histologic subtypes may be at higher risk for port-site metastases and tumor spillage and dissemination due to uterine manipulation and vaginal removal of the uterus during the procedure. Given the limited data describing the safety of minimally invasive hysterectomy for women with uterine cancer and high-risk histologic subtypes, we performed a population-based analysis to examine the outcomes of the procedure in these women. Specifically, we examined trends the use of minimally invasive hysterectomy and compared survival between abdominal and minimally invasive hysterectomy in women with stage I-III non-endometrioid uterine cancers.

Methods

Data Source and Cohort Selection

The National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) was used for analysis. NCDB is a nationwide registry developed by the American College of Surgeons and American Cancer Society.12,13 The database records all patients with newly diagnosed invasive cancers from over 1500 Commission on Cancer (CoC) affiliated hospitals located throughout the United States. The NCDB catalogues data on patient demographic factors, tumor characteristics and treatment data, staging, and survival. Data are abstracted by trained registrars and is audited regularly to ensure accuracy. It is estimated that approximately 67% of women with invasive cancer in the U.S. are captured in the NCDB.14 The study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University.

Women with stage I-III uterine cancer diagnosed from 2004-2014 were included. Only patients who underwent total hysterectomy and had a known route of hysterectomy were included in the analysis (Figure 1). The route of hysterectomy was classified as abdominal, laparoscopic, and robotic-assisted. Patients who underwent either a laparoscopic or robotic-assisted procedure were classified as having undergone minimally invasive surgery. The cohort was limited to those women with positive histologic confirmation of endometrioid, serous, clear cell, sarcoma, and leiomyosarcoma, stromal sarcoma, and carcinosarcoma. Women with sarcomas without further classification as leiomyosarcoma, carcinosarcoma or stromal sarcoma were categorized as a separate subgroup. Women who received radiation prior to surgery were excluded from the cohort.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes

Demographic data analyzed included age (<50, 50-59, 60-69, 70-79, ≥80 years), race (white, black, Hispanic, other or unknown), insurance status (private, Medicare, Medicaid, other government, other or unknown), education (percentage of adults in a patient’s zip code that did not graduate high school: ≥29%, 20-28.9%, 14-19.9%, <14%, unavailable), and median household income within a patient’s zip code (< $30,000, $30,000 - $35,999, $36,000 - $45,999, ≥$46,000, not available). Comorbidity was measured using the Deyo classification of the Charlson comorbidity score (0, 1, ≥2).15,16

Tumor stage (stages IA-IIIC), tumor grade (well, moderate, poorly differentiated, or unknown), and tumor size (0-20, 21-40, 41-60, 61-80, 81-100, >100 mm, or unknown) was also noted for each patient. Treatment characteristics including lymph node assessment (yes, no, unknown), use of chemotherapy (yes, no, unknown), and use of radiation (external beam with or without brachytherapy, brachytherapy, none) were recorded for each individual. Hospital characteristics were analyzed and categorized by regional location (Eastern, South, Midwest, West, unknown) and urban/rural location (metropolitan, urban, rural, unknown). Based on the ACS CoC criteria, hospitals were classified as academic/research cancer centers or community cancer centers.

The primary endpoint of the analysis was survival. Short term survival was estimated as 30 and 90-day survival. Overall survival was estimated as the time from diagnosis until death from any cause or the date of last follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

We stratified demographic and clinical characteristics of women with endometrial cancer by route of hysterectomy (abdominal vs. minimally invasive). Frequency distributions between categorical variables were compared using χ2 tests. Multivariable log-linear regression models with Poisson distribution and log link based on a generalized estimating equation (GEE) were developed to estimate the association between each covariate and the use of minimally invasive surgery after accounting for hospital clustering. The results are reported as adjusted rate ratios (aRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

A propensity score analysis was used to limit the influence of measured confounders on survival.17,18 The propensity score was estimated as the predicted probability that a patient underwent a minimally invasive hysterectomy. The inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) approach based on propensity score was used to balance the observed confounders between treatments (abdominal vs. minimally invasive hysterectomy). To calculate the propensity score, we fit a logistic regression model that included all of the clinical, oncologic, and hospital characteristics and two-way interaction terms. The predicted probability (the propensity score) ranging from 0 to 1 was estimated for each patient. The weighting assumptions of the IPTW approach assigns patients who underwent the treatment of interest a weight of 1/propensity score and those who did not undergo the treatment of interest a weight of 1/(1-propensity score). To standardize the variability of IPTW and reduce the influence of extreme weights, we applied a stabilization that multiplies the weights from treatment and comparison groups by a constant, and employed a trimming technique that trims the stabilized weights within a specified range (≤10).19

After IPTW, the balance of measured confounders between treatments was assessed via a weighted regression approach, in which each covariate was regressed on the treatment variable. The coefficients and corresponding P-values in the weighted regression models were used to determine the clinically unimportant differences between treatment groups using a threshold value of the coefficients of less than 0.2.20 Separate propensity scores models were developed for each histologic subtype using backward selection. Individual models for endometroid cancer, serous carcinoma and carcinosarcoma included all the main effects and two-way interaction terms with a significance level of 0.2-0.1 to allow for model convergence. Given the smaller sample size of some of the histologic subtypes, models for clear cell carcinoma, sarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, and stromal sarcoma included all covariates without interaction terms. All propensity score models had acceptable model discrimination of C-statistics between 0.7 and 0.8 and provided good fit to the data based on Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit tests.21

After propensity score weighting, we compared 30-day and 90-day mortality based on surgical approach by marginal log-linear regression models accounting for inverse probability weight and lymph nodes dissection as well as hospital clustering. Marginal multivariable Cox proportional-hazard models were developed to evaluate the effect of surgical approach on overall survival after. Along with performance of lymph nodes dissection, the use of chemotherapy and radiation were adjusted in the overall mortality model. Results from Cox proportional-hazard models were reported as adjusted hazards ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Kaplan-Meier curves were developed to assess survival based on use of minimally invasive hysterectomy compared to laparotomy. Separate curves were developed for each histologic subtype in the IPTW cohorts. Results were compared using log rank tests. Sensitivity analyses were performed in examine survival separately for each stage (stages I, II, III). All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina). All statistical tests were two-sided. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 94,507 women including 64,417 (68.2%) who underwent minimally invasive hysterectomy and 30,090 (31.8%) who underwent abdominal hysterectomy were identified (Table 1). Among women with endometrioid tumors, 70.8% underwent minimally invasive hysterectomy. The rates of minimally invasive hysterectomy in those with non-endometrioid tumors was 57.6% for serous carcinomas, 57.0% for clear cell tumors, 47.3% for sarcomas, 32.2% for leiomyosarcomas, 47.9% for stromal sarcomas and 48.5% for carcinosarcomas (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of women with uterine cancer stratified by route of surgery.

| Minimally Invasive Surgery | ||

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Adjusted RR (95%CI) | |

| 64,417 (68.2) | ||

| Histology | ||

| Endometrioid | 57,436 (70.8) | Referent |

| Serous | 3418 (57.6) | 0.90 (0.87 - 0.93)** |

| Clear cell | 692 (57.0) | 0.89 (0.85 - 0.94)** |

| Sarcoma | 260 (47.3) | 0.77 (0.71 - 0.84)** |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 287 (32.2) | 0.64 (0.58 - 0.70)** |

| Stromal Sarcoma | 388 (47.9) | 0.81 (0.76 - 0.87)** |

| Carcinosarcoma | 1936 (48.5) | 0.83 (0.79 - 0.86)** |

| Age (years) | ||

| <50 | 7254 (65.3) | Referent |

| 50-59 | 19,125 (68.9) | 1.02 (1.01 - 1.04)* |

| 60-69 | 23,711 (69.2) | 1.04 (1.02 - 1.05)** |

| 70-79 | 10,701 (67.8) | 1.04 (1.02 - 1.06)* |

| ≥80 | 13,626 (65.1) | 1.04 (1.01 - 1.07)* |

| Race | ||

| White | 51,409 (70.6) | Referent |

| Black | 4794 (54.3) | 0.86 (0.83 - 0.90)** |

| Hispanic | 3607 (62.2) | 0.95 (0.90 - 1.00) |

| Other | 2625 (67.0) | 0.96 (0.93 - 1.00)* |

| Unknown | 1982 (62.2) | 0.95 (0.87 - 1.03) |

| Insurance Status | ||

| Private | 34,536 (71.0) | Referent |

| Medicaid | 2896 (57.8) | 0.88 (0.85 - 0.91)** |

| Medicare | 23,540 (67.5) | 0.96 (0.95 - 0.98)** |

| Other Government | 742 (73.2) | 0.85 (0.80 - 0.91)** |

| Not Insured | 2097 (55.7) | 1.02 (0.98 - 1.06) |

| Unknown | 606 (49.1) | 0.73 (0.56 - 0.97)* |

| Education of not receiving high school | ||

| ≥29% | 8889 (61.1) | Referent |

| 20-28.9% | 13,783 (67.1) | 1.03 (1.01 - 1.07)* |

| 14-19.9% | 14,717 (67.5) | 1.03 (0.99 - 1.07) |

| <14% | 24,884 (71.9) | 1.08 (1.04 - 1.12)* |

| Not Available | 2144 (71.6) | 0.99 (0.69 - 1.42) |

| Median household Income | ||

| < $30,000 | 6657 (60.3) | Referent |

| $30,000 - $35,999 | 10,020 (66.1) | 1.04 (1.01 - 1.08)* |

| $36,000 - $45,999 | 17,275 (68.4) | 1.06 (1.02 - 1.11)* |

| ≥$46,000 | 28,330 (70.6) | 1.05 (1.00 - 1.11)* |

| Not Available | 2135 (71.6) | 1.15 (0.79 - 1.66) |

| Urban/Rural | ||

| Metropolitan | 51,625 (68.0) | Referent |

| Urban | 9778 (68.2) | 1.03 (1.00 - 1.07) |

| Rural | 1227 (69.0) | 1.06 (0.99 - 1.13) |

| Unknown | 1787 (71.1) | 1.01 (0.97 - 1.06) |

| Comorbidity | ||

| 0 | 47,721 (68.8) | Referent |

| 1 | 13,726 (67.3) | 0.99 (0.98 - 1.01) |

| 2 | 2970 (63.0) | 0.95 (0.92 - 0.98)* |

| Year of diagnosis | ||

| 2010 | 8768 (52.4) | Referent |

| 2011 | 11,397 (63.7) | 1.21 (1.18 - 1.25)** |

| 2012 | 13,290 (70.4) | 1.34 (1.29 - 1.39)** |

| 2013 | 15,351 (75.6) | 1.44 (1.38 - 1.50)** |

| 2014 | 15,611 (75.5) | 1.44 (1.38 - 1.50)** |

| Stage | ||

| INOS | 4042 (62.8) | 0.93 (0.89 - 0.97)* |

| IA | 41,293 (73.2) | Referent |

| IB | 10,453 (66.4) | 0.96 (0.94 - 0.97)** |

| II | 2647 (56.2) | 0.87 (0.85 - 0.89)** |

| III NOS | 87 (43.5) | 0.73 (0.61 - 0.88)* |

| IIIA | 1609 (54.0) | 0.84 (0.81 - 0.87)** |

| IIIB | 468 (51.8) | 0.86 (0.81 - 0.92)** |

| IIIC | 3818 (53.7) | 0.83 (0.81 - 0.86)** |

| Grade | ||

| Well | 27,223 (72.8) | Referent |

| Moderate | 16,069 (68.3) | 0.97 (0.95 - 0.99)* |

| Poorly | 9556 (56.9) | 0.92 (0.89 - 0.94)** |

| Unknown | 11,569 (68.8) | 0.98 (0.95 - 1.01) |

| Tumor size | ||

| 0-20mm | 14,509 (73.5) | Referent |

| 21-40mm | 20,422 (72.7) | 1.00 (0.99 - 1.01) |

| 41-60mm | 11,297 (66.8) | 0.96 (0.94 - 0.98)** |

| 61-80mm | 3976 (59.1) | 0.89 (0.87 - 0.92)** |

| 81-100mm | 1354 (47.8) | 0.76 (0.73 - 0.80)** |

| >100mm | 872 (33.9) | 0.59 (0.56 - 0.63)** |

| Unknown | 11,987 (68.0) | 0.97 (0.94 - 1.01) |

| Facility location | ||

| Eastern | 13,706 (68.4) | Referent |

| South | 17,545 (71.0) | 1.06 (0.98 - 1.15) |

| Midwest | 20,154 (64.7) | 0.96 (0.88 - 1.03) |

| West | 11,159 (70.6) | 1.03 (0.95 - 1.11) |

| Unknown | 1853 (66.5) | 1.06 (1.00 - 1.13) |

| Facility type | ||

| Community | 1591 (50.5) | 0.76 (0.67 - 0.85)** |

| Comprehensive Community | 25,371 (70.8) | 1.03 (0.97 - 1.09) |

| Academic/Research Program | 27,239 (66.4) | Referent |

| Integrated Network Cancer Program | 8363 (71.1) | 1.05 (0.96 - 1.15) |

| Unknown | 1853 (66.5) | 1.00 (0.99 – 1.03) |

P<0.05;

P<0.0001.

INOS: stage I not otherwise specified.

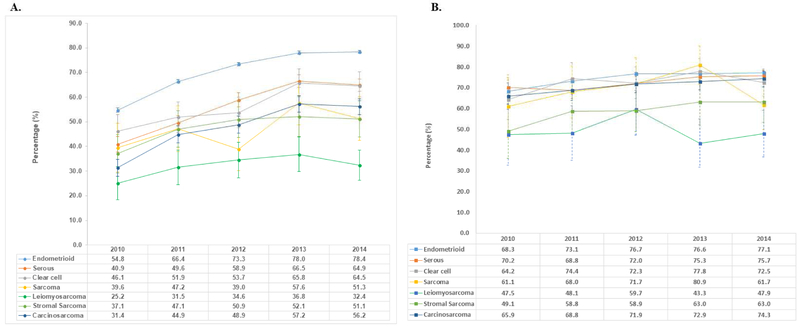

Performance of minimally invasive hysterectomy increased across all histologic subtypes between 2010 and 2014 (Figure 2). For endometrioid tumors, minimally invasive hysterectomy rose from 54.8% in 2010 to 78.4% in 2014. Comparatively, by 2014 minimally invasive hysterectomy increased to 64.9% of serous carcinoma, 64.5% of clear cell tumors, 51.3% of sarcomas, 32.4% of leiomyosarcomas, 51.1% of stromal sarcomas and 56.2% of carcinosarcomas.

Figure 2A.

Trends in use of minimally invasive surgery stratified by histologic subtype. 2B. Trends in use of robotic-assisted hysterectomy among women who underwent minimally invasive surgery.

Among women with endometrioid tumors who underwent a minimally invasive hysterectomy, robotic-assisted procedures accounted for 68.3% of the cases in 2010 and rose over time to 77.1% by 2014 (Figure 3). Except for leiomyosarcomas, similar trends were noted for the other non-endometrioid histologic subtypes with robotic-assisted procedures accounting for 61.7%-75.7% of the minimally invasive hysterectomies by 2014. For women with leiomyosarcomas, robotic-assistance was used in less than 50% of the minimally invasive cases during most of the years of the study.

Figure 3.

Survival stratified by use of minimally invasive hysterectomy for each histologic subtype. A.

In a multivariable model, compared to endometrioid histologies, patients with the other histologic subtypes were less likely to undergo minimally invasive hysterectomy (P<0.0001 for all) (Table 2). Patients with sarcoma and leiomyosarcoma histologies were least likely to undergo MIS, with rate ratios of 0.77 (95% CI, 0.71-0.84) and 0.64 (95% CI, 0.58-0.70), respectively. More recent year of diagnosis, older age, white race, and higher zip code income were associated with greater likelihood of minimally invasive hysterectomy (P<0.05 for all). In contrast, non-commercial insurance, greater comorbidity, treatment at a community cancer program, higher grade, more advanced size and larger tumor size were all associated with a lower likelihood of a minimally invasive procedure (P<0.05 for all). Increasing stage significantly decreased the likelihood for undergoing MIS; compared to stage IA patients, rate ratios for use of MIS decreased with increasing stage from 0.97 (95% CI, 0.95-0.98) for stage IB patients, to 0.88 (95% CI, 0.85-0.90) for stage II patients, to 0.85 (95% CI, 0.61-0.87) for stage III patients.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of women with endometrial cancer stratified by MIS in unadjusted and IPTW adjusted cohort

| Unadjusted Cohort | IPTW Cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimally invasive surgery | Minimally invasive surgery | |||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |||

| (n=64,417) | (n=30,090) | (n=68,399) | (n=38,638) | |||

| N (%) | N (%) | P-value | N (%) | N (%) | P-value | |

| Histology | <0.0001 | 0.989 | ||||

| Endometrioid | 57,436 (89.2) | 23679 (78.7) | 58687 (85.8) | 33141 (85.8) | ||

| Serous | 3418 (5.3) | 2519 (8.4) | 4310 (6.3) | 2425 (6.3) | ||

| Clear cell | 692 (1.1) | 522 (1.7) | 875 (1.3) | 492 (1.3) | ||

| Sarcoma | 260 (0.4) | 290 (1.0) | 398 (0.6) | 231 (0.6) | ||

| Leiomyosarcoma | 287 (0.4) | 603 (2.0) | 649 (0.9) | 369 (1.0) | ||

| Stromal Sarcoma | 388 (0.6) | 422 (1.4) | 587 (0.9) | 352 (0.9) | ||

| Carcinosarcoma | 1936 (3.0) | 2055 (6.8) | 2891 (4.2) | 1628 (4.2) | ||

| Age (years) | <0.0001 | 0.9874 | ||||

| <50 | 5401 (8.4) | 2922 (9.7) | 8061 (11.8) | 4580 (11.9) | ||

| 50-59 | 19,125 (29.7) | 8627 (28.7) | 20055 (29.3) | 11286 (29.2) | ||

| 60-69 | 23,711 (36.8) | 10575 (35.1) | 24793 (36.2) | 13993 (36.2) | ||

| 70-79 | 10,701 (16.6) | 5089 (16.9) | 11432 (16.7) | 6492 (16.8) | ||

| ≥80 | 3626 (5.6) | 1943 (6.5) | 4057 (5.9) | 2287 (5.9) | ||

| Race | <0.0001 | 0.8736 | ||||

| White | 51,409 (79.8) | 21371 (71) | 52680 (77) | 29681 (76.8) | ||

| Black | 4794 (7.4) | 4029 (13.4) | 6415 (9.4) | 3645 (9.4) | ||

| Hispanic | 3607 (5.6) | 2196 (7.3) | 4176 (6.1) | 2420 (6.3) | ||

| Other | 2625 (4.1) | 1291 (4.3) | 2833 (4.1) | 1593 (4.1) | ||

| Unknown | 1982 (3.1) | 1203 (4) | 2295 (3.4) | 1299 (3.4) | ||

| Insurance Status | <0.0001 | 0.8148 | ||||

| Private | 34,536 (53.6) | 14085 (46.8) | 2718 (4.0) | 1530 (4.0) | ||

| Medicaid | 2896 (4.5) | 2116 (7.0) | 35204 (51.5) | 19842 (51.4) | ||

| Medicare | 23,540 (36.5) | 11323 (37.6) | 3638 (5.3) | 2064 (5.3) | ||

| Other Government | 742 (1.2) | 271 (0.9) | 25265 (36.9) | 14275 (36.9) | ||

| Not Insured | 2097 (3.3) | 1668 (5.5) | 734 (1.1) | 414 (1.1) | ||

| Unknown | 606 (0.9) | 627 (2.1) | 839 (1.2) | 515 (1.3) | ||

| Education of not receiving high school | <0.0001 | 0.9833 | ||||

| ≥29% | 8889 (13.8) | 5653 (18.8) | 10582 (15.5) | 5975 (15.5) | ||

| 20-28.9% | 13,783 (21.4) | 6770 (22.5) | 14851 (21.7) | 8383 (21.7) | ||

| 14-19.9% | 14,717 (22.8) | 7072 (23.5) | 15783 (23.1) | 8960 (23.2) | ||

| <14% | 24,884 (38.6) | 9745 (32.4) | 25041 (36.6) | 14094 (36.5) | ||

| Not Available | 2144 (3.3) | 850 (2.8) | 2142 (3.1) | 1225 (3.2) | ||

| Median household Income | <0.0001 | |||||

| < $30,000 | 6657 (10.3) | 4377 (14.5) | 7983 (11.7) | 4519 (11.7) | ||

| $30,000 - $35,999 | 10,020 (15.6) | 5131 (17.1) | 10984 (16.1) | 6152 (15.9) | ||

| $36,000 - $45,999 | 17,275 (26.8) | 7965 (26.5) | 18313 (26.8) | 10359 (26.8) | ||

| ≥$46,000 | 28,330 (44) | 11772 (39.1) | 28983 (42.4) | 16385 (42.4) | ||

| Not Available | 2135 (3.3) | 845 (2.8) | 2136 (3.1) | 1223 (3.2) | ||

| Urban/Rural | 0.0101 | 0.9231 | ||||

| Metropolitan | 51,625 (80.1) | 24262 (80.6) | 54919 (80.3) | 31086 (80.5) | ||

| Urban | 9778 (15.2) | 4551 (15.1) | 10378 (15.2) | 5802 (15) | ||

| Rural | 1227 (1.9) | 551 (1.8) | 1285 (1.9) | 724 (1.9) | ||

| Unknown | 1787 (2.8) | 726 (2.4) | 1817 (2.7) | 1026 (2.7) | ||

| Comorbidity | <0.0001 | 0.9972 | ||||

| 0 | 47,721 (74.1) | 21671 (72) | 50197 (73.4) | 28363 (73.4) | ||

| 1 | 13,726 (21.3) | 6678 (22.2) | 14779 (21.6) | 8346 (21.6) | ||

| 2 | 2970 (4.6) | 1741 (5.8) | 3423 (5.0) | 1930 (5.0) | ||

| Year of diagnosis | <0.0001 | 0.9592 | ||||

| 2010 | 7254 (11.3) | 3856 (12.8) | 12147 (17.8) | 6855 (17.7) | ||

| 2011 | 11,397 (17.7) | 6501 (21.6) | 12931 (18.9) | 7299 (18.9) | ||

| 2012 | 13,290 (20.6) | 5598 (18.6) | 13643 (19.9) | 7780 (20.1) | ||

| 2013 | 15,351 (23.8) | 4957 (16.5) | 14720 (21.5) | 8270 (21.4) | ||

| 2014 | 15,611 (24.2) | 5074 (16.9) | 14957 (21.9) | 8434 (21.8) | ||

| Stage | <0.0001 | 0.8183 | ||||

| INOS | 4042 (6.3) | 2399 (8) | 4633 (6.8) | 2643 (6.8) | ||

| IA | 41,293 (64.1) | 15127 (50.3) | 40830 (59.7) | 23040 (59.6) | ||

| IB | 10,453 (16.2) | 5294 (17.6) | 11410 (16.7) | 6428 (16.6) | ||

| II | 2647 (4.1) | 2059 (6.8) | 3424 (5) | 1916 (5) | ||

| III NOS | 87 (0.1) | 113 (0.4) | 121 (0.2) | 88 (0.2) | ||

| IIIA | 1609 (2.5) | 1372 (4.6) | 2147 (3.1) | 1217 (3.2) | ||

| IIIB | 468 (0.7) | 436 (1.4) | 647 (0.9) | 374 (1) | ||

| IIIC | 3818 (5.9) | 3290 (10.9) | 5186 (7.6) | 2931 (7.6) | ||

| Grade | <0.0001 | 0.9433 | ||||

| Well | 27,223 (42.3) | 10166 (33.8) | 27078 (39.6) | 15263 (39.5) | ||

| Moderate | 16,069 (24.9) | 7450 (24.8) | 16958 (24.8) | 9601 (24.8) | ||

| Poorly | 9556 (14.8) | 7232 (24.0) | 12215 (17.9) | 6866 (17.8) | ||

| Unknown | 11,569 (18) | 5242 (17.4) | 12148 (17.8) | 6909 (17.9) | ||

| Tumor size | <0.0001 | 0.9985 | ||||

| 0-20mm | 14,509 (22.5) | 5228 (17.4) | 14283 (20.9) | 8021 (20.8) | ||

| 21-40mm | 20,422 (31.7) | 7688 (25.6) | 20332 (29.7) | 11464 (29.7) | ||

| 41-60mm | 11297 (17.5) | 5606 (18.6) | 12242 (17.9) | 6955 (18.0) | ||

| 61-80mm | 3976 (6.2) | 2754 (9.2) | 4879 (7.1) | 2773 (7.2) | ||

| 81-100mm | 1354 (2.1) | 1481 (4.9) | 2072 (3) | 1173 (3) | ||

| >100mm | 872 (1.4) | 1701 (5.7) | 1858 (2.7) | 1055 (2.7) | ||

| Unknown | 11,987 (18.6) | 5632 (18.7) | 12732 (18.6) | 7198 (18.6) | ||

| Facility location | <0.0001 | 0.9504 | ||||

| Eastern | 13,706 (21.3) | 6328 (21) | 14557 (21.3) | 8149 (21.1) | ||

| South | 17,545 (27.2) | 7182 (23.9) | 17917 (26.2) | 10134 (26.2) | ||

| Midwest | 20,154 (31.3) | 10995 (36.5) | 22447 (32.8) | 12709 (32.9) | ||

| West | 11,159 (17.3) | 4651 (15.5) | 11471 (16.8) | 6492 (16.8) | ||

| Unknown | 1853 (2.9) | 934 (3.1) | 2007 (2.9) | 1154 (3) | ||

| Facility type | <0.0001 | 0.9886 | ||||

| Community | 1591 (2.5) | 1557 (5.2) | 2289 (3.3) | 1284 (3.3) | ||

| Comprehensive Community | 25,371 (39.4) | 10443 (34.7) | 25950 (37.9) | 14642 (37.9) | ||

| Academic/Research Program | 27,239 (42.3) | 13760 (45.7) | 29632 (43.3) | 16727 (43.3) | ||

| Integrated Network Cancer Program | 8363 (13) | 3396 (11.3) | 8520 (12.5) | 4831 (12.5) | ||

| Unknown | 1853 (2.9) | 934 (3.1) | 2007 (2.9) | 1154 (3) | ||

IPTW: inverse probability of treatment weigthed. NOS: stage not otherwise specified.

After propensity score weighting the cohort was well balanced (Table 2). The median follow-up time for patients with non-endometrioid tumors was 27.9 months (IQR, 17.4-41.5). For each of the non-endometrioid histologic subtypes, there was no statistically significant association between route of surgery and either 30 or 90-day mortality (Table 3). Similarly, there was no association between route of surgery and overall mortality for any of the non-endometrioid histologic subtypes. Similar findings were noted in a series of Kaplan-Meier analyses stratified by histology (P>0.05 for all). The results were unchanged in a series of sensitivity analyses stratified by stage.

Table 3.

Comparison of overall mortality and mortality within 30 or 90 days of surgery between treatment.

| Serous | Carcinosarcoma | Clear Cell | Leiomyosarcoma | Stromal Sarcoma | Sarcoma | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-day mortality |

||||||

| Abdominal (%) | 0.8 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 2.2 |

| Minimally invasive (%) | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| aRR (95% CI)Λ | 0.63 (0.24 - 1.63) | 0.51 (0.22 - 1.17) | NA | 0.96 (0.09 - 10.57) | NA | NA |

| 90-day mortality |

||||||

| Abdominal (%) | 1.7 | 4.4 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 4.3 | 5.8 |

| Minimally invasive (%) | 1.0 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 0.0 |

| aRR (95% CI)Λ | 0.83 (0.47 - 1.45) | 1.00 (0.63 - 1.59) | NA | 0.33 (0.07 - 1.50) | 0.98 (0.31 - 3.12) | NA |

| Overall mortality |

||||||

| Abdominal (%) | 27.8 | 42.6 | 27.8 | 40.4 | 25.2 | 29.6 |

| Minimally invasive (%) | 21.6 | 34.4 | 21.3 | 25.5 | 14.2 | 17.0 |

| aHR (95% CI)ΛΛ | 1.09 (0.95 - 1.24) | 1.07 (0.93 - 1.23) | 1.11 (0.82 - 1.51) | 0.77 (0.54 - 1.08) | 1.00 (0.67 - 1.50) | 0.80 (0.48 -1.33) |

P<0.05;

P<0.0001.

Adjusted for lymphadenectomy in IPTW log linear model.

Adjusted lymphadenectomy, radiation and chemotherapy in IPTW marginal multivariable Cox proportional hazard model.

Comment

These findings demonstrate that the use of minimally invasive hysterectomy has increased rapidly for non-endometrioid uterine cancers. In addition to oncologic characteristics, a number of non-clinical factors are associated with the performance of minimally invasive hysterectomy. Importantly, for all of the non-endometrioid histologic subtypes examined there was no association between the route of hysterectomy and survival.

Despite the fact that data supporting the efficacy of minimally invasive hysterectomy for women with non-endometrioid tumors is limited, our findings suggest that the procedure has already gained widespread acceptance among clinicians. By 2014, over 50% of the hysterectomies performed for all of the histologic subtypes we examined except leiomyosarcoma were performed via a minimally invasive surgical approach. While diffusion of laparoscopic hysterectomy which was first described in the 1990’s was initially slow, use of the procedure has substantially since 2005.4,22 The widespread acceptance of minimally invasive hysterectomy for women with endometrioid tumors likely promoted the rise of the procedure for other histologic subtypes despite the relative lack of data.

Minimally invasive surgery for high-risk non-endometrioid histologic subtypes present the technical challenge of manipulating larger tumors with greater potential for metastatic spread. During the operation, increased intra-abdominal pressure from carbon dioxide is required to maintain the pneumoperitoneum, often for a prolonged period, and this pressure may increase the risk of abdominal wall metastases (so-called port-site metastases), which are estimated to occur in just over 1% of women who undergo gynecologic surgery.23 Also during the procedure, uterine manipulaton may disrupt the uterine cavity and subsequently disseminate tumor cells into the vagina or through the fallopian tube. Large uteri, often associated with high-risk histologies or more advanced disease, are particularly apt to result in tumor spillage during manipulation or removal through the vagina. This could affect both short and long-term oncologic outcomes

Prior studies examining the safety of minimally invasive hysterectomy for non-endometrioid tumors have included relatively small numbers of women.2 The LAP2 trial included 492 women with non-endometrioid (clear cell, serous, sarcoma, and mixed) tumors. In sub-group analyses among women with non-endometrioid tumors, minimally invasive hysterectomy was found to be non-inferior to laparotomy in all of the subtypes analyzed.2 In contrast, the LACE trial excluded women with non-endometrioid histologic variants.1,10 Our findings are reassuring in that we found no difference in survival between laparotomy and minimally invasive hysterectomy in 30 or 90 day mortality or overall survival for women with serous and clear cell carcinoma, carcinosarcoma, and other uterine sarcomas.

Robotic-assisted hysterectomy is now the most common minimally invasive surgical modality used in women with non-endometrioid tumors. For serous tumors and carcinosarcomas, robotically assisted procedures made up three quarters of the minimally invasive operations in our cohort. Studies of women with endometrioid tumors have also demonstrated rapid uptake of robotic-assisted surgery.24 Prior work has shown that outcomes are comparable between laparoscopic and robotic-assisted hysterectomy but that robotic-assisted surgery is substantially more costly.24

Although our study benefits from the inclusion of a large sample of patients, we recognize a number of important limitations. First, while the findings of no difference in survival was encouraging, our cohort was diagnosed from 2010 to 2014 and we cannot exclude the small possibility of a survival differential with longer follow-up. Second, we lack data on some important clinical characteristics including uterine size, tumor spillage at the time of surgery and patterns of recurrence. Third, our data are based on tumor registry data and we lack centralized pathology review. As such, there may be misclassification of a small number of women, particularly for those with uncommon histologic variants. Although perioperative complication rates have been compared for minimally invasive and open hysterectomy in a number of studies, there are few large studies limited to non-endometrioid uterine cancer. While analyzing complication rates is of interest, NCDB lacks detailed data on perioperative complications. Lastly, NCDB lacks data on toxicity, quality of life, and patient reported outcomes. As with any study of administrative data, we cannot capture individual patient and physician preferences that undoubtedly influenced treatment decision-making. However, from a patient standpoint, these outcomes have an important impact on medical decision-making and preferences and warrant future study.

As minimally invasive hysterectomy continues to diffuse into wider practice, monitoring outcomes of less-selected patients in real-world settings remains a priority. While minimally invasive oncologic surgery has proven safe for a number of procedures, recent data for cervical cancer in which mortality was higher for minimally invasive surgery highlights the importance of determining the comparative effectiveness of new procedures prior to widespread dissemination.25 Our data suggest that minimally invasive hysterectomy for women with stage I-III non-endometrioid uterine tumors does not adversely affect survival. Given the benefits of minimally invasive hysterectomy compared to laparotomy the procedure appears to be a reasonable approach to the surgical management of women with non-endometrioid uterine cancers.

AJOG at a Glace.

Why was this study conducted?

While minimally invasive surgery (MIS) is routinely used for women with uterine cancer, most studies have focused on low-risk, endometrioid tumors with few studies of women with higher risk histologic subtypes.

What are the key findings?

The rates of MIS in those with non-endometrioid tumors was 57.6% for serous carcinomas, 57.0% for clear cell tumors, 47.3% for sarcomas, 32.2% for leiomyosarcomas, 47.9% for stromal sarcomas and 48.5% for carcinosarcomas. There was no association between route of surgery and 30-day, 90-day, or overall mortality for any of the non-endometrioid histologic subtypes.

What does this study add to what is already known?

The use of minimally invasive surgery for women with stage I-III non-endometrioid uterine tumors does not appear to adversely impact survival.

Acknowledgements:

Dr. Wright has served as a consultant for Tesaro and Clovis Oncology. Dr. Neugut has served as a consultant to Pfizer, Teva, Eisai, Otsuka, and United Biosource Corporation. He is on the medical advisory board of EHE, Intl. No other authors have any conflicts of interest or disclosures.

Dr. Wright (NCI R01CA169121-01A1) and Dr. Hershman (NCI R01 CA166084) are recipients of grants from the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Hershman is the recipient of a grant from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation/Conquer Cancer Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Janda M, Gebski V, Davies LC, et al. Effect of Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy vs Total Abdominal Hysterectomy on Disease-Free Survival Among Women With Stage I Endometrial Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017;317:1224–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker JL, Piedmonte MR, Spirtos NM, et al. Recurrence and survival after random assignment to laparoscopy versus laparotomy for comprehensive surgical staging of uterine cancer: Gynecologic Oncology Group LAP2 Study. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:695–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright JD, Burke WM, Tergas AI, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Minimally Invasive Hysterectomy for Endometrial Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:1087–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright JD, Neugut AI, Wilde ET, Buono DL, Tsai WY, Hershman DL. Use and benefits of laparoscopic hysterectomy for stage I endometrial cancer among medicare beneficiaries. J Oncol Pract 2012;8:e89–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galaal K, Bryant A, Fisher AD, Al-Khaduri M, Kew F, Lopes AD. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy for the management of early stage endometrial cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012:CD006655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obermair A, Janda M, Baker J, et al. Improved surgical safety after laparoscopic compared to open surgery for apparent early stage endometrial cancer: results from a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer 2012;48:1147–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zullo F, Palomba S, Falbo A, et al. Laparoscopic surgery vs laparotomy for early stage endometrial cancer: long-term data of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;200:296 e1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tozzi R, Malur S, Koehler C, Schneider A. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy in endometrial cancer: first analysis of survival of a randomized prospective study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2005;12:130–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker JL, Piedmonte MR, Spirtos NM, et al. Laparoscopy compared with laparotomy for comprehensive surgical staging of uterine cancer: Gynecologic Oncology Group Study LAP2. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5331–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janda M, Gebski V, Brand A, et al. Quality of life after total laparoscopic hysterectomy versus total abdominal hysterectomy for stage I endometrial cancer (LACE): a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:772–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goff BA, Shahin MS, Powell MA, Dowdy SC. SGO Health Policy and Socioeconomic Committee: Current and Future Efforts of the Coding and Reimbursement Taskforce and the Policy, Quality and Outcomes Taskforce. Gynecol Oncol 2016;143:229–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The National Cancer Data Base. (Accessed March 10, 2012, at http://www.facs.org/cancer/ncdb/index.html.)

- 13.Bilimoria KY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, Ko CY. The National Cancer Data Base: a powerful initiative to improve cancer care in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:683–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lerro CC, Robbins AS, Phillips JL, Stewart AK. Comparison of cases captured in the national cancer data base with those in population-based central cancer registries. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:1759–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:613–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hadley J, Yabroff KR, Barrett MJ, Penson DF, Saigal CS, Potosky AL. Comparative effectiveness of prostate cancer treatments: evaluating statistical adjustments for confounding in observational data. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:1780–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hemmila MR, Birkmeyer NJ, Arbabi S, Osborne NH, Wahl WL, Dimick JB. Introduction to propensity scores: A case study on the comparative effectiveness of laparoscopic vs open appendectomy. Arch Surg 2010;145:939–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harder VS, Stuart EA, Anthony JC. Propensity score techniques and the assessment of measured covariate balance to test causal associations in psychological research. Psychol Methods 2010;15:234–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ross ME, Kreider AR, Huang YS, Matone M, Rubin DM, Localio AR. Propensity Score Methods for Analyzing Observational Data Like Randomized Experiments: Challenges and Solutions for Rare Outcomes and Exposures. Am J Epidemiol 2015;181:989–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weitzen S, Lapane KL, Toledano AY, Hume AL, Mor V. Weaknesses of goodness-of-fit tests for evaluating propensity score models: the case of the omitted confounder. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2005;14:227–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Childers JM, Brzechffa PR, Hatch KD, Surwit EA. Laparoscopically assisted surgical staging (LASS) of endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 1993;51:33–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zivanovic O, Sonoda Y, Diaz JP, et al. The rate of port-site metastases after 2251 laparoscopic procedures in women with underlying malignant disease. Gynecol Oncol 2008;111:431–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright JD, Burke WM, Wilde ET, et al. Comparative effectiveness of robotic versus laparoscopic hysterectomy for endometrial cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:783–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melamed A, Chen L, del Carmen M, Keating NL, Wright JD Rauh-Hain JA Comparative effectiveness of minimally-invasive staging surgery in women with early-stage cervical cancer. 49th Annual Meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology; 2018; New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]