Abstract

Co-use of cannabis and tobacco is increasingly common among women and is associated with tobacco and cannabis dependence and poorer cessation outcomes. However, no study has examined maternal patterns of co-use over time, or the impact of maternal co-use on co-use and drug problems in adult offspring. Pregnant women (M age = 23, range = 18–42; 52% African American, 48% White) were asked about substance use during each trimester of pregnancy, and at 8 and 18 months, 3, 6, 10, 14, 16, and 22 years postpartum. We examined patterns of any maternal cigarette and cannabis use during pregnancy and the postpartum years. As young adults (M age = 22.8 years, range = 21-26), 603 offspring completed the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS). Growth mixture modeling (GMM) was used to identify four maternal trajectories through 16 years postpartum: (1) no co-use (66%), (2) decreasing co-use (16%), (3) postpartum-only co-use (11%), and (4) chronic co-use (7%). Offspring whose mothers were in the decreasing co-use group (co-users primarily during prenatal and preschool periods) were more likely to be co-users than the offspring of non-co-users. Offspring whose mothers were chronic co-users of cigarettes and cannabis were more than twice as likely to have a drug use disorder than young adults whose mothers were not co-users. The results of this study highlight the heterogeneity in maternal co-use of tobacco and cannabis over time, with some women quitting during pregnancy but resuming co-use in the postpartum, and other women co-using during pregnancy but desisting co-use over time. Maternal trajectories of co-use were associated with inter-generational transfer of risk for substance use and dependence in adult offspring.

Keywords: cannabis, tobacco, co-use, polysubstance use, marijuana

1. Introduction

Although fewer American women are smoking tobacco cigarettes, the use of cannabis and the co-use of cannabis with tobacco have significantly increased and are especially common among women of reproductive age (Conway et al., 2018; Schauer et al., 2015). From 2005 to 2015, the rate of women this age stating that there was no risk associated with weekly marijuana use tripled (Jarlenski et al., 2017). In fact, pregnant women in the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) were just as likely to be cannabis users as non-pregnant women, although they were less likely to be tobacco-only users or co-users of cannabis and tobacco (Coleman-Cowger et al., 2017). However, co-use of cannabis with tobacco during pregnancy is more common than cannabis use alone, and is more common among pregnant young adult, Black, and Hispanic women (Coleman-Cowger et al., 2017; Gray et al., 2010).

In cross-sectional studies, co-use has been linked to both cannabis and tobacco dependence, and to poorer psychosocial outcomes (Agrawal et al., 2012; Montgomery, 2015; Montgomery & Bagot, 2016; Ream et al., 2008; Timberlake, 2009; Wang et al., 2016). Not surprisingly, female co-users are at high-risk of continuing co-use during pregnancy (El Marroun et al., 2008; Ko et al., 2015; Lester et al., 2001). In the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), co-users were at greater risk of Cannabis Use Disorder (CUD) than cannabis-only users (Agrawal et al., 2009). Thus, pregnant women who use both substances may have greater difficulty quitting cannabis use during pregnancy. Moreover, it is highly likely that many women who co-use tobacco cigarettes and cannabis during pregnancy will continue to do so in the postpartum, and their offspring may thus be at risk of both prenatal and postnatal (environmental) exposure to maternal tobacco cigarette and cannabis use.

Maternal substance use is a well-known risk factor for offspring substance use and substance use disorders. This risk begins early in life, as prenatal tobacco cigarette exposure predicts cigarette use during adolescence (Agrawal et al., 2010; Cornelius et al., 2000, 2005; De Genna et al., 2016a; O’Brien & Hill, 2014) and risk for tobacco dependence (Buka et al., 2003; De Genna et al., 2017a; Shenassa et al., 2015). Similarly, maternal prenatal cannabis use is linked to cigarette and cannabis use (Porath & Fried, 2005, Sonon et al., 2015) and cannabis dependence (Sonon et al., 2016) in exposed offspring. Even more women use substances in the postpartum than during pregnancy, and many studies have linked postnatal substance use to substance use and Substance Use Disorders (SUDs) in offspring. Maternal substance use is associated with initiation and frequency of substance use during adolescence (e.g., Andrews et al., 1993; Brook et al., 2001; Gilman et al., 2009; Hawkins et al., 1992; Vermeulin-Smit et al., 2015), trajectories of substance use from adolescence to adulthood (Brook et al., 2012; Chassin et al., 1996; Walden et al., 2007), and adult SUDs (Chassin et al., 1999).

Thus, there is a strong link between prenatal exposures to tobacco and cannabis (considered separately) to early initiation of substance use and adolescent risk for tobacco and cannabis dependence. There is a separate literature demonstrating that maternal postnatal substance use is also associated with the initiation and frequency of adolescent substance use, trajectories of use into adulthood, and SUDs. Taken together, these findings suggest that both prenatal and postnatal exposures to maternal cigarette and cannabis use will independently predict substance use and SUDs in offspring. Although co-use of cannabis and tobacco are correlated with poorer psychosocial outcomes and greater risk of dependence on both substances for individuals who co-use, there is a gap in the literature on the effect of maternal co-use of these substances on offspring. It is not clear if maternal patterns of co-using cigarettes and cannabis over time have any impact on adult offspring risk for co-use and SUDs.

Group-based trajectory modeling allows substance use researchers to identify long-term trajectories of use and to determine if specific maternal trajectories of use are associated with other outcomes, such as offspring health and behavior (Nagin, 1999). For example, trajectories of cannabis use in teenage mothers predicted early initiation of sexual intercourse in adolescent offspring, suggesting that maternal substance use may play a role in the inter-generational transfer of risk for early parenthood (De Genna et al., 2015b). Trajectory analyses of maternal tobacco cigarette use have revealed the utility of examining long-term patterns of maternal substance use as risk factors for cigarette use in offspring (De Genna et al, 2016a; Melchior et al., 2010). It is important to investigate the effects of maternal patterns of co-use of cannabis and tobacco on offspring co-use and drug use disorders, controlling for variables that are associated with substance use in both mother and child.

There are many factors associated with exposure to maternal substance use and young adult risk for substance use that need to be considered in multivariate analysis. For example, maternal age and maternal symptoms of depression and hostility predict trajectories of maternal substance use (De Genna et al., 2015b; 2016a; 2017b) so it is possible that the offspring of younger, more depressed and hostile mothers are at greater risk of co-use and drug use disorders. Prenatal alcohol use has been linked to cannabis use in young adult offspring (Sonon et al., 2015), in addition to problem drinking and Alcohol Use Disorders (AUDs) (Alati et al., 2006; Baer et al., 2003). Co-use and drug use disorders in offspring may also be the result of an inherited predisposition to dependence, so it is important to determine if patterns of maternal co-use predict substance use and abuse in adult offspring, above and beyond the effects of maternal tobacco, cannabis, and alcohol use disorders. Offspring neurodevelopment, sex, and educational attainment are also well-known correlates of young adult cigarette and cannabis use. Some investigators report sex-specific effects of maternal prenatal and postnatal cigarette and cannabis use on substance use in offspring (Kandel et al., 1994, 2015; Kandel & Udry, 1999; Porath & Fried, 2005; Roberts et al., 2005; Rydell et al., 2012; Sullivan et al., 2011), so sex differences should also be examined.

Despite women’s increasing co-use of cannabis and tobacco and recent interest in group-based trajectory modeling of co-occurring substance use (e.g., Brook et al., 2012; Green et al., 2017; Liu & Munford, 2017), no previous analysis has focused on trajectories of co-use of cigarettes and cannabis in mothers. The goals of this study are to (1) identify and describe trajectories of any maternal co-use of tobacco cigarettes and cannabis, and (2) to determine if specific trajectories of any maternal co-use during gestation and postpartum periods are associated with adult offspring risk for co-use and drug use disorders. Based on the extant literature on trajectories of prenatal and postnatal maternal use of single substances (De Genna et al, 2015a; 2015b, 2016b, 2017b; Liu et al., 2016; Liu & Mumford, 2017; Mumford & Liu, 2016; Tran et al., 2015a; 2015b; Tucker et al., 2006), we hypothesized that there would be distinct trajectories of maternal co-use of tobacco cigarettes and cannabis across the prenatal and postpartum periods, with different patterns of pre- and postpartum desistance. As maternal substance use is known to predict substance use in offspring, we hypothesized that the adult offspring of chronic co-users would be more likely to be co-users themselves, and more likely to develop a drug use disorder by age 22. We did not have a hypothesis for sex-specific effects of maternal co-use trajectories on offspring co-use and drug use disorder, as this was an exploratory analysis.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

Pregnant women (18 and older) were recruited in their 4th or 5th prenatal month from a teaching hospital in Pittsburgh, PA from 1982-1985 as part of two cohort studies. Women reported on their substance use twice during pregnancy and at delivery, 8 and 18 months, and 3, 6, 10, 14, 16 and 22 years postpartum. Other maternal substance use, demographic characteristics, and psychosocial factors were also assessed at each phase. Demographic characteristics, substance use, and psychiatric disorders were assessed in the young adult offspring during the 22-year visit. This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Eighty-five percent of the women who were approached agreed to participate in the studies, with no differences in maternal age, income, or race between those who participated and those who refused. Two cohorts were selected from the initial sample, pregnant adult women who: 1) drank 3 or more alcoholic drinks per week and a random sample of women who drank less often or not at all were selected for a study of prenatal alcohol use (AA06390: PI N. Day), and 2) used marijuana at the rate of 2 or more joints per month and a random sample of women who used marijuana less often or not at all were chosen for a study of the effects of prenatal marijuana use (DA03874: PI N. Day). More details on the parent study designs are available in previous publications (e.g., Day et al., 1989; 1991). Women could be in one or both samples. These two studies combined had 763 adult women with live-born singleton offspring.

At the 22-year postpartum visit, 608 offspring were assessed (80% of the birth cohort). There were 30 refusals, 56 lost to follow-up, 29 moved out of the area, 18 unavailable due to institutionalization (jail or rehab), 11 had died, 8 unable to participate due to low IQ, and 3 had been adopted and were no longer part of the study. The 22-year sample did not differ in maternal socioeconomic status, race, prenatal marijuana, tobacco, or alcohol use from the 155 who were not assessed at this time point. Five cases seen at age 22 were removed from this analysis due to extensive missing maternal substance use data, for a final sample size of 603.

2.2. Sample characteristics

On average, the mothers in this study were 23 years old (SD = 4.0), 52% African American, 48% White, and had the equivalent of a high school education (M=11.8, SD = 1.4 years). Fifty-three percent reported first trimester cigarette use, 41% first trimester cannabis use, and 64% first trimester alcohol use. One-quarter of the mothers used both tobacco and cannabis during the first trimester. On average, the offspring were 23 years old (SD = 0.7) at the latest assessment. Half were female (53%) and they reported an average of 13 years of education (SD = 1.6). Forty-four percent of the young adult offspring were smokers, 50% were cannabis users, and 30% had used both substances in the past year. Sixteen percent of the 22-year old offspring had a diagnosis of a drug use disorder using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS), described below (Robins et al., 2000).

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Maternal co-use of cannabis and tobacco

Women were interviewed about their patterns of substance use at the end of their first and second trimesters, and at delivery to determine third trimester exposure. Maternal substance use was also assessed at all postpartum interviews. Mothers were asked the quantity and frequency of various forms of cannabis use, including joints, bongs, blunts, hashish, sinsemilla, and bowls. These were standardized to an equivalency in joints (Gold, 1989; Julien, 1998). We also ascertained whether the cannabis was shared with others or smoked alone. For tobacco, mothers were asked about the current quantity and frequency and recent history of cigarette use. As the goals of this study were to describe trajectories of any co-use of these two substances and determine if the co-use of any amount of these substances was related to adult offspring co-use and SUD, dichotomous variables indicating any use were created for each assessment period. For the trajectory analysis, a dichotomous co-use variable was created for each time point (0 = no co-use, 1 = use of both substances).

2.3.2. Adult offspring outcomes

At the 22-year follow-up, the young adult offspring reported on their substance use using the same interviews described in Section 2.3.1. Offspring co-use was defined as any cigarette plus cannabis use in the past year. Offspring mental health was assessed using the DIS, a standardized, highly structured interview used to diagnose prior and current mental health based on DSM-IV criteria (Robins et al., 1981; 2000). A variable was created to examine the presence or absence of a drug use disorder by this time point, defined as a diagnosis of abuse or dependence of any illicit drug (i.e., did not include tobacco dependence or alcohol use disorders).

2.3.3. Covariates

At the first visit, mothers provided their date of birth and race. We assessed quantity and frequency of beer, liquor, wine, and wine and beer coolers consumed by the mothers at each time point. Average daily volume of all alcohol used in the first trimester was used in the analysis to control for prenatal exposure to alcohol. Sixteen years postpartum, maternal tobacco dependence was measured using the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) (Heatherton et al., 1991). Maternal substance use disorders, including CUD and AUD, were assessed with the DIS. Maternal depressive symptoms were measured 16 years postpartum by the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES-D: Radloff, 1977). Dispositional anxiety and hostility were assessed using the State Trait Personality Inventory (STPI: Spielberger et al., 1979).

2.3.3.2. Child characteristics

Child sex was recorded at birth. At the age 14 follow-up, the offspring completed a neuropsychological assessment including the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children ∓ Third Edition (WISC-III: Wechsler, 1991) and Conners’ Continuous Performance Test (CPT) measuring inattention and impulsivity (Conners, 1995), in which the adolescents were presented with specific visual target stimuli and asked to respond as quickly and accurately as possible. At this phase, the Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning ∓ Screening (WRAML-S: Sheslow & Adams, 1990) was also administered. The WRAML summary screening index score was used in bivariate analyses. For the CPT, scores of errors of omission and commission were included in bivariate analyses. At the 16-year follow-up, mothers reported on the adolescent’s behavior problems using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL: Achenbach, 1991). Scores for the externalizing and internalizing behavior problem scales were used in the analyses. At 22 years, the offspring reported on their highest level of education completed, and this was used to calculate years of education.

2.4. Statistical analysis

To address the first goal of the study, data on maternal co-use of cigarettes and cannabis from the first trimester to the 16-year follow-up were analyzed to identify trajectories of co-use over time using growth mixture modeling (GMM) in Mplus (Muthén, 2004). GMM allows within-class variation and we had sufficient repeated measures to estimate trajectories with cubic growth parameters. Mplus can also handle missing data if they are missing at random. Postpartum intermittent missing data were not related to prenatal substance use and maternal characteristics. As mentioned in the Methods section, five cases were deleted due to data missing for several of the most recent phases, which could result in biased imputation.

Based on our (De Genna et al., 2015; 2016) and others’ (Desrosiers et al., 2016; Liu & Mumford, 2017; Tucker et al., 2006) prior studies of cigarette and cannabis use in pregnant and parenting women, we knew that there would be at least 3 classes of users (non-co-users, chronic co-users, women who continued to smoke cigarettes but stopped using marijuana toward the end of their pregnancy). Hence, we started with a 3-class model and tested to see if solutions with 4 or more classes better fit the data. The number of classes that best fit the maternal co-use data was determined using statistical considerations such as a lower Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), higher entropy value, and the sizes of the identified classes of maternal co-use (Nagin, 2005; Nylund et al., 2007). The posterior probabilities for each trajectory were also monitored. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi square tests of difference were used to compare maternal characteristics as a function of co-use trajectory group.

To address the second goal of the study, regression analysis was used to determine if maternal trajectory classes from gestation through 16 years postpartum predicted the young adult offspring outcomes, controlling for covariates. Based on the literature, these covariates were considered for inclusion in multivariate analysis: maternal age; prenatal exposure to alcohol; offspring sex and race; offspring IQ, impulsivity, and memory assessed 14 years postpartum; offspring internalizing and externalizing behavior problems, maternal tobacco dependence, maternal AUD and maternal CUD assessed 16 years postpartum; offspring educational attainment by age 22. Maternal tobacco and cannabis dependence were not included in the final regression analyses because they were not associated with the offspring outcomes. Results were then stratified by offspring sex to determine if there were sex-specific effects of maternal co-use trajectories on offspring co-use and drug use disorder.

3. Results

3.1. Maternal co-use trajectories

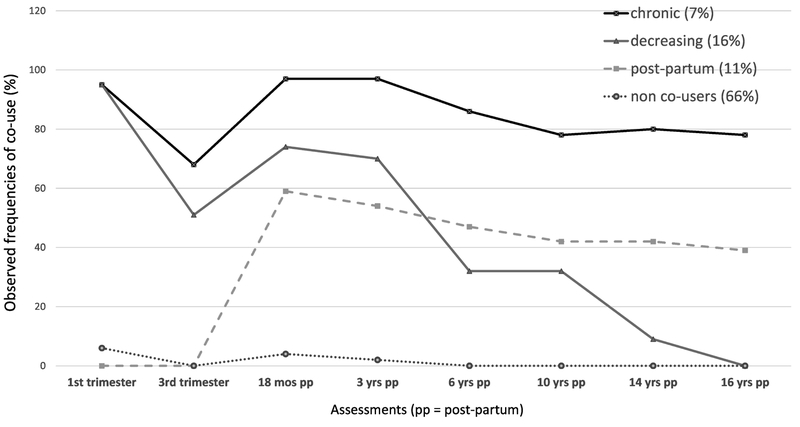

Statistics for fitting 3, 4, 5, and 6 cubic class trajectories of maternal co-use of cannabis and tobacco are provided in Table 1. According to the BIC, a 5-group solution had the best fit, but it resulted in a trajectory group that was too small (n = 23) for multivariate analysis. We chose the 4-group model because it had the next smallest BIC, similar entropy, and adequate numbers in each class. As seen in Figure 1, the largest group of mothers identified in this model were the least likely to engage in co-use of cigarettes and cannabis at all time points (non-users = 66%). Patterns of co-use in the next largest group were characterized by decreasing use over time, especially once their children were school age (decreasers = 16%). Another group was characterized by abstinence from co-use during pregnancy but a higher likelihood of use in the postpartum (postpartum-only =11%). The smallest group was a pattern of chronic co-use of cigarettes and cannabis across every time point (chronic co-users = 7%).

Table 1.

Growth Mixture Model (GMM) fit statistics

| Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) |

Entropy | Lowest average latent class probability for most likely class membership |

Size of smallest trajectory class identified in the model |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-class solution | 3137 | 0.844 | 0.86 | 73 |

| 4-class solution | 3090 | 0.862 | 0.79 | 40 |

| 5-class solution | 3087 | 0.866 | 0.75 | 23 |

| 6-class solution | 3095 | 0.851 | 0.76 | 21 |

Figure 1.

Maternal Trajectories of Co-Use of Cigarettes and Cannabis

3.2. Maternal characteristics associated with co-use trajectories

As seen in Table 2, there were fewer White mothers in the decreasing or postpartum co-use groups than in the non- and chronic co-user groups. The decreasing pattern of maternal co-use was associated with single motherhood and more prenatal alcohol use. The postpartum pattern of co-use was associated with single motherhood, lower income, and higher levels of hostility 16 years postpartum. There were no differences among maternal co-use groups in maternal age, education, employment, or depression. The chronic use pattern was associated with increased tobacco dependence and CUD in the mothers.

Table 2.

Maternal Characteristics Associated with Maternal Co-Use Trajectory Groups

| (N = 603) | Non/Unlikely to Co-Use (n = 396) |

Decreasing Co-Use (n = 99) |

Postpartum Co-Use (n =68) |

Chronic Co-Use (n = 40) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 23.3 | 22.5 | 22.3 | 23.3 |

| Race (% White) | 52% | 39% | 37% | 48%* |

| Education 1st trimester (years) | 11.9 | 11.8 | 11.6 | 11.4 |

| Employed 1st trimester | 28% | 27% | 19% | 10% |

| Married 1st trimester | 35% | 23% | 24% | 28%* |

| Monthly family income 1st trimester | $467 | $409 | $373 | $415* |

| Depression 1st trimestera | 73% | 82% | 65% | 73% |

| Hostility 1st trimesterb | 18.4 | 19.8 | 19.0 | 19.2 |

| Depression 16 years postpartuma | 62% | 72% | 70% | 72% |

| Hostility 16 years postpartumb | 15.9 | 16.2 | 17.9 | 16.4* |

| 1st trimester alcohol user | 60% | 83% | 62% | 65%*** |

| 3rd trimester alcohol user | 29% | 44% | 28% | 32%* |

| Maternal cigarette use | ||||

| 1st trimester | 39% | 97% | 46% | 98% |

| 3rd trimester | 37% | 88% | 50% | 98% |

| 18 mos postpartum | 47% | 93% | 83% | 100% |

| 3 years postpartum | 46% | 99% | 77% | 100% |

| 6 years postpartum | 43% | 89% | 87% | 100% |

| 10 years postpartum | 44% | 86% | 77% | 94% |

| 14 years postpartum | 41% | 73% | 72% | 97% |

| 16 years postpartum | 42% | 69% | 75% | 97% |

| Maternal cannabis use | ||||

| 1st trimester | 22% | 98% | 38% | 98% |

| 3rd trimester | 6% | 56% | 10% | 70% |

| 18 mos postpartum | 16% | 83% | 70% | 100% |

| 3 years postpartum | 16% | 71% | 69% | 97% |

| 6 years postpartum | 7% | 39% | 52% | 86% |

| 10 years postpartum | 7% | 33% | 47% | 86% |

| 14 years postpartum | 4% | 14% | 46% | 77% |

| 16 years postpartum | 6% | 4% | 39% | 75% |

| Co-use of cannabis and tobacco | ||||

| 1st trimester | 6% | 95% | 0 | 95% |

| 3rd trimester | 0 | 51% | 0 | 68% |

| 18 mos postpartum | 4% | 75% | 60% | 97% |

| 3 years postpartum | 2% | 71% | 57% | 97% |

| 6 years postpartum | 0 | 32% | 49% | 86% |

| 10 years postpartum | 0 | 31% | 42% | 81% |

| 14 years postpartum | 0 | 10% | 43% | 77% |

| 16 years postpartum | 1% | 1% | 37% | 75% |

| Maternal tobacco dependencec | ||||

| 16 years postpartum | 21% | 34% | 29% | 44%* |

| Maternal cannabis use disorderc | ||||

| 16 years postpartum | 7% | 12% | 12% | 17% |

Depression score > 35 on the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES-D)

c Hostility score from the State Trait Personality Inventory (STPI)

Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND)

Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS)

p < .05,

p<.01,

p<.001

3.3. Adult offspring outcomes.

Logistic regression analyses were conducted using the maternal no co-use group as the reference group. The maternal co-use trajectory variable was a significant predictor of young adult offspring co-use of cannabis and tobacco and drug use disorder, even after controlling for male sex, adolescent internalizing behavior problems, and young adult educational attainment (Table 3a). Specifically, offspring of mothers from the decreasing group were more likely to be co-users than offspring of mothers who were in the non-co-user group (Adjusted Odds Ratio = 2.24, CI 1.38-3.64). The offspring of the chronic maternal co-users (Adjusted Odds Ratio = 2.54, CI 1.13-5.69) were significantly more likely to have a drug use disorder by young adulthood, compared to the non-co-user trajectory offspring (Table 3b). By analyzing data for male and female offspring separately, we determined that the decreasing maternal co-use trajectory predicted co-use in sons, but not in daughters (Table 4b). When the drug use disorder outcome was analyzed separately by sex of offspring, there were no significant relations with the maternal co-use trajectories.

Table 3.

Multivariate results of maternal co-use trajectories on young adult offspring

| 3a. Logistic regression on Young Adult Co-Use of Cannabis and Tobacco | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | S.E. | Odds Ratio | CI |

| Maternal Co-Usea | ||||

| Decreasers | 0.81 | 0.25 | 2.24 | 1.38-3.64 |

| Postpartum | 0.44 | 0.30 | 1.56 | 0.86-2.80 |

| Chronic | 0.29 | 0.37 | 1.34 | 0.64-2.79 |

| Offspring Sex (male) | 0.45 | 0.19 | 1.56 | 1.07-2.27 |

| Offspring Education | −0.43 | 0.07 | 0.66 | 0.58-0.76 |

| CBCL internalizing | 0.02 | 0.009 | 1.02 | 1.00-1.04 |

| 3b. Logistic regression on Young Adult Drug Use Disorder | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | S.E. | Odds Ratio | CI |

| Maternal Co-Usea | ||||

| Decreasers | −0.21 | 0.36 | 0.81 | 0.40-1.64 |

| Postpartum | 0.64 | 0.36 | 1.90 | 0.94-3.82 |

| Chronic | 0.93 | 0.41 | 2.54 | 1.13-5.69 |

| Offspring Sex (male) | 1.28 | 0.26 | 3.60 | 2.18-5.96 |

| Offspring Education | −0.21 | 0.08 | 0.81 | 0.70-0.95 |

| Maternal AUDb | 0.75 | 0.30 | 2.12 | 1.18-3.83 |

Non Co-users were the reference group.

Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS)

Table 4.

Sex-specific effects of maternal co-use on adult offspring co-use

| 4a. Female offspring | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | S.E. | Odds Ratio | CI |

| Maternal hostility | 0.06 | 0.03 | 1.06 | 1.00-1.11 |

| Offspring Education | −0.43 | 0.09 | 0.65 | 0.55-0.78 |

| 4b. Male offspring | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | S.E. | Odds Ratio | CI |

| Maternal Co-Usea | ||||

| Decreasers | 1.24 | 0.37 | 3.44 | 1.66-7.14 |

| Postpartum | 0.31 | 0.46 | 1.37 | 0.55-3.38 |

| Chronic | 0.91 | 0.55 | 2.48 | 0.83-7.35 |

| CBCL internalizing | 0.03 | 0.01 | 1.03 | 1.01-1.06 |

| Offspring Education | −0.37 | 0.10 | 0.69 | 0.57-0.84 |

Non Co-users were the reference group.

4. Discussion

This study leveraged data from a 22-year longitudinal study to identify long-term maternal patterns of co-use of cannabis and tobacco from the first trimester of pregnancy until 16 years postpartum. Three maternal co-use trajectories were identified in one-third of the mothers, including a group that abstained during pregnancy but resumed co-use in the postpartum, and two groups that co-used during pregnancy. Among the prenatal co-users, one group of mothers decreased co-use over time and another group of mothers co-used at every time point in the study. Most women who decreased co-use during pregnancy continued to smoke cigarettes while abstaining from cannabis use. There is evidence that cannabis use promotes tobacco dependence (Agrawal et al., 2008a; 2008b) so pregnant cannabis users may have more difficulty with smoking cessation than pregnant women who have not used cannabis. Similarly, postpartum patterns of desistance in this sample were marked by cessation of cannabis use over time, rather than cessation of cigarette use. This is consistent with the literature suggesting that cannabis use inhibits cigarette quit attempts and smoking cessation (Ford et al., 2002; Strong et al., 2018; Weinberger et al., 2018), although findings in this area are mixed (Peters et al., 2012).

Consistent with our hypothesis, the offspring of chronic maternal co-users were at much greater risk of developing a drug use disorder by age 22 than the offspring of women who did not co-use cigarettes and cannabis. There was also an inter-generational transfer of risk for co-use of cannabis and tobacco among young adult offspring whose mothers were in the decreasing co-use group. However, the offspring of chronic co-users were not at greater risk of co-use. Although unexpected, these results converge with a previous finding that adolescent offspring exposed to maternal smoking during the prenatal and preschool years only were more likely to become smokers than the offspring of chronic smokers (De Genna et al., 2016a). Maternal AUD also predicted drug use disorder in young adult offspring, but maternal tobacco dependence and CUD were not significantly associated with young adult co-use of cigarettes and cannabis or with offspring drug use disorder.

Stratifying by sex revealed that there may be a stronger effect of maternal co-use trajectories on co-use in young adult male offspring. As in the overall sample, male offspring whose mothers were in the decreasing co-use group were more likely to become co-users by age 22. Porath and Fried (2005) found that the effects of prenatal exposure to maternal cannabis use on cigarette and cannabis use in offspring was more pronounced in males but reported no sex differences in the effects of prenatal tobacco exposure. In contrast, other research has shown greater effects of prenatal and postnatal maternal cigarette use on daughters’ risk for smoking and tobacco dependence (lakunchykova et al., 2015; Kandel et al., 1994, 2015; Kandel & Udry, 1999; Roberts et al., 2005; Rydell et al., 2012; Sullivan et al., 2011) and drug dependence (Weissman et al., 1999). However, other longitudinal studies have demonstrated no sex differences in the effects of maternal cigarette and marijuana use on adolescent and adult offspring (e.g., Buka et al., 2003; Day et al., 2006; Gilman et al. 2009; Peterson et al., 2006). This was the first study of maternal trajectories of co-use on offspring co-use, so it is impossible to conclude that there is sex-specific inter-generational transmission, and the study warrants replication in other samples.

One of the strengths of this study is the prospectively collected data on maternal substance use across two decades. In contrast, one of the only other studies of maternal substance use from the pre- to postpartum period that has analyzed trajectories of substance use, including the co-use of tobacco and alcohol, has only 6 years of available data (Liu & Mumford, 2017). However, the sample for the current study was recruited in the 1980s from a city teaching hospital and was oversampled for prenatal substance use. Thus, results may not generalize to mothers from the general population, including mothers of race/ethnicities other than White and African-American. It is possible that different co-use trajectories may be observed in other samples. Moreover, despite excellent retention rates, some of the maternal co-use trajectory groups were small, and there may not have been adequate power to detect sex-specific differences in the effects of maternal patterns of co-use on drug abuse in adult offspring. Another limitation was one common to secondary data analysis, a reliance on variables previously collected. It is possible that there are other, unmeasured factors that would explain the association between maternal trajectories of co-use of cigarettes and cannabis on offspring substance use and abuse. Nonetheless, a strength of the current study was the breadth of measures available, allowing us to control for maternal and offspring demographic characteristics, maternal prenatal and postnatal alcohol use, maternal mental health, and offspring neurodevelopment and adolescent behavior problems.

Prenatal cigarette use has become less common and prenatal cannabis use has become more common since these data were collected. Nonetheless, data on adolescent women from Wave 1 of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study indicate that tomorrow’s mothers remain at risk of co-use of cannabis and tobacco, compared to male peers. Smokers aged 12-17 were 15 times more likely to use cannabis as non-smokers, and female smokers were significantly more likely to be co-users than males (Conway et al., 2018). In fact, as blunt use (smoking cannabis in cigar and cigarillo wrappers) has become more popular over time, it is increasingly likely that women of reproductive age may be inadvertently exposing themselves (and the fetus) to nicotine even if they quit smoking cigarettes during pregnancy (Peters et al., 2016). Mode of administration was not considered in this study, and co-use was defined as any/none, regardless of level of use. Future research should consider levels of cannabis and tobacco co-use, and whether maternal co-use is associated with an increased use of joints and blunts, rather than non-combusted forms of cannabis use. More research is needed to determine whether the co-use trajectories identified in this study adequately represent the number of classes of maternal co-use in mothers.

The results of this study add to the growing literature on long-term patterns of maternal substance use by employing group-based trajectory modeling to identify different patterns of co-use of cannabis and tobacco cigarettes among mothers. We capitalized on data from prospective studies of maternal substance use that oversampled for prenatal substance use with sufficient variability across two decades of motherhood to identify three long-term patterns of maternal co-use. The results of this study demonstrate that there is heterogeneity in maternal co-use of cigarettes and cannabis over time. Moreover, this heterogeneity in maternal co-use trajectories has implications for the inter-generational transmission of risk for substance use and abuse in young adult offspring.

Highlights.

There are distinct trajectories of maternal co-use of cigarettes and cannabis.

Maternal patterns of co-use predict substance use in young adult offspring.

Offspring of decreasing co-users (with prenatal exposure) more likely to co-use.

Offspring of chronic co-users more likely to have drug use disorder by age 22.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Achenbach T Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Budney AJ, Lynskey MT (2012). The co-occurring use and misuse of cannabis and tobacco: A review. Addiction 107:1221–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Lynskey MT. (2009). Tobacco and cannabis co-occurrence: does route of administration matter? Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 99(1):240–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Lynskey MT, Pergadia ML, Bucholz KK, Heath AC, Martin NG, Madden PA. (2008a). Early cannabis use and DSM-IV nicotine dependence: a twin study. Addiction. 103(11):1896–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Heath AC, Lynskey MT. (2008b). Transitions to regular smoking and to nicotine dependence in women using cannabis. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 95(1):107–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Scherrer J, Grant J, Sartor C, Pergadia M, Duncan A, et al. , (2010). The effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy on offspring outcomes. Preventative Medicine. 50, 13–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alati R, Al Mamun A, Williams GM, O’Callaghan M, Najman JM, Bor W. (2006). In utero alcohol exposure and prediction of alcohol disorders in early adulthood: a birth cohort study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 63(9):1009–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Hops H, Ary D, Tildesley E, Harris J. (1993). Parental influence on early adolescent substance use: Specific and nonspecific effects. The Journal of Early Adolescence. August;13(3):285–310. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Sampson PD, Barr HM, Connor PD, Streissguth AP. (2003). A 21-year longitudinal analysis of the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on young adult drinking. Archives of General Psychiatry. 60(4):377–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Brook DW, Arencibia-Mireles O, Richter L, Whiteman M. (2001). Risk factors for adolescent marijuana use across cultures and across time. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 162(3):357–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Rubenstone E, Zhang C, Brook DW. (2012). Maternal predictors of comorbid trajectories of cigarette smoking and marijuana use from early adolescence to adulthood. Addictive Behaviors. 37(1):139–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buka SL, Shenassa ED, Niaura R, (2003). Elevated risk of tobacco dependence among offspring of mothers who smoked during pregnancy: a 30-year prospective study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 160, 1978–1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Pitts SC, DeLucia C, Todd M. (1999). A longitudinal study of children of alcoholics: predicting young adult substance use disorders, anxiety, and depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 108(1):106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Rose JS, Sherman SJ. (1996). The natural history of cigarette smoking from adolescence to adulthood: demographic predictors of continuity and change. Health Psychology. 15(6):478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman-Cowger VH, Schauer GL, Peters EN (2017). Marijuana and tobacco co-use among a nationally representative sample of US pregnant and non-pregnant women: 2005–2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health findings. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 177:130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK (1995). Conners’ Continuous Performance Test Computer Program CPT 3.0. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Conway KP, Green VR, Kasza KA, Silveira ML, Borek N, Kimmel HL, Sargent JD, Stanton CA, Lambert E, Hilmi N, Reissig CJ. (2018). Co-occurrence of tobacco product use, substance use, and mental health problems among youth: Findings from wave 1 (2013–2014) of the population assessment of tobacco and health (PATH) study. Addictive Behaviors. 76:208–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius MD, Leech SL, Goldschmidt L, Day NL, (2000). Prenatal tobacco exposure: is it a risk factor for early tobacco experimentation? Nicotine and Tobacco Res. 2, 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius MD, Leech SL, Goldschmidt L, Day NL, (2005). Is prenatal tobacco exposure a risk factor for early adolescent smoking? A follow-up study. Neurotoxicology & Teratology. 27, 667–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day NL, Goldschmidt L, Thomas CA. (2006). Prenatal marijuana exposure contributes to the prediction of marijuana use at age 14. Addiction. 101(9):1313–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day NL, Jasperse D, Richardson G, Robles N, Sambamoorthi U, Taylor P, Scher M, Stoffer D, Cornelius M. (1989). Prenatal exposure to alcohol: effect on infant growth and morphologic characteristics. Pediatrics. 84(3):536–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Genna NM, Goldschmidt L, Cornelius MD. (2015a). Maternal patterns of marijuana use and early sexual behavior in offspring of teenage mothers. Maternal and Child Health. 19(3):626–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Genna NM, Goldschmidt L, Cornelius MD, Day N. (2015b). Maternal age and trajectories of cannabis use. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 156:199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Genna NM, Goldschmidt L, Day NL, Cornelius MD. (2016a). Prenatal and postnatal maternal trajectories of cigarette use predict adolescent cigarette use. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 18(5):988–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Genna NM, Goldschmidt L, Day N, Cornelius MD. (2016b). Maternal trajectories of cigarette use as a function of maternal age and race. Addictive Behaviors. 65: 33–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Genna NM, Goldschmidt L, Day NL, Cornelius MD. (2017a). Prenatal tobacco exposure, maternal postnatal nicotine dependence and adolescent risk for nicotine dependence: Birth cohort study. Neurotoxicology & Teratology. 61:128–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Genna NM, Goldschmidt L, Marshal MP, Day N, Cornelius MD. (2017b). Maternal age and trajectories of risky alcohol use: a prospective study. Alcohol: Clinical & Experimental Research. 41:1725–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers A, Thompson A, Divney A, Magriples U, Kershaw T. (2016). Romantic partner influences on prenatal and postnatal substance use in young couples. Journal of Public Health, 38(2):300–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierker LC, Braymiller J. Rose JS, Goodwin R Selya A (2018). Nicotine dependence predicts cannabis use disorder among adolescents and young adults. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 187:212–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Marroun H, Tiemeier H, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Mackenbach JP, Steegers EA, et al. (2008). Demographic, emotional and social determinants of cannabis use in early pregnancy: The Generation R study. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 98:218–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford DE, Vu HT, Anthony JC. (2002). Marijuana use and cessation of tobacco smoking in adults from a community sample. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 67(3):243–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Rende R, Boergers J, Abrams DB, Buka SL, Clark MA, Colby SM, Hitsman B, Kazura AN, Lipsitt LP, Lloyd-Richardson EE. (2009). Parental smoking and adolescent smoking initiation: an intergenerational perspective on tobacco control. Pediatrics. 123(2):e274–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold M, 1989. Marijuana. Plenum, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Gray TR, Eiden RD, Leonard KE, Connors GJ, Shisler S, Huestis MA (2010). Identifying prenatal cannabis exposure and effects of concurrent tobacco exposure on neonatal growth. Clinical Chemistry. 56:1442–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KM, Musci RJ, Matson PA, Johnson RM, Reboussin BA, Ialongo NS. (2017). Developmental patterns of adolescent marijuana and alcohol use and their joint association with sexual risk behavior and outcomes in young adulthood. Journal of Urban Health. 94(1):115–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. (1992). Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 112(1):64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. (1991). The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 86:1119–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iakunchykova O, Andreeva TI, Nizhnyk ZS, Antipkin Y, Hryhorczuk D, Zvinchuk A, Chislovska N (2015). Maternal smoking during pregnancy and adolescent smoking initiation and continuation: A prospective cohort study. SM Journal of Community Medicine. 1(1):1003. [Google Scholar]

- Jarlenski M, Koma JW, Zank J, Bodnar LM, Bogen DL, Chang JC. (2017). Trends in perception of risk of regular marijuana use among US pregnant and nonpregnant reproductive-aged women. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 217(6):705–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julien RM (1998). A Primer of Drug Action, eighth edition. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Griesler PC, Hu MC. (2015). Intergenerational patterns of smoking and nicotine dependence among US adolescents. American Journal of Public Health. 105(11):e63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Udry JR. (1999). Prenatal effects of maternal smoking on daughters' smoking: nicotine or testosterone exposure? American Journal of Public Health. 89(9):1377–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Wu P, Davies M. (1994). Maternal smoking during pregnancy and smoking by adolescent daughters. American Journal of Public Health. 84(9):1407–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko JY, Farr SL, Tong VT, Creanga AA, Callaghan WM. (2015). Prevalence and patterns of marijuana use among pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 213:201-e1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester BM, ElSohly M, Wright LL, Smeriglio VL, Verter J, Bauer CR, et al. (2001). The Maternal Lifestyle Study: Drug use by meconium toxicology and maternal self-report. Pediatrics. 107:309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Mumford EA, Petras H. (2016). Maternal alcohol consumption during the perinatal and early parenting period: a longitudinal analysis. Maternal and Child Health. 20(2):376–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Mumford EA. (2017). Concurrent Trajectories of Female Drinking and Smoking Behaviors Throughout Transitions to Pregnancy and Early Parenthood. Prevention Science. 18(4):416–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchior M, Chastang JF, Mackinnon D, Galéra C, Fombonne E. (2010). The intergenerational transmission of tobacco smoking—the role of parents’ long-term smoking trajectories. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 107(2):257–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery L (2015). Marijuana and tobacco use and co-use among African Americans: Results from the 2013, National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Addictive Behaviors. 51:18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery L, Bagot K (2016). Let’s be blunt: Consumption methods matter among black marijuana smokers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 77:451–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumford EA, Liu W. (2016). Social integration and maternal smoking: A longitudinal analysis of a national birth cohort. Maternal and Child Health. 20(8):1586–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B (2004). Latent variable analysis: Growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data In Kaplan D (ed.), Handbook of quantitative methodology for the social sciences (pp. 345–368). Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS (1999). Analyzing developmental trajectories: a semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychological Methods. 4(2):139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS (2005). Group-based modeling of development Harvard University Press. Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén B (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling. 14:535–569. [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien JW, Hill SY. (2014). Effects of Prenatal Alcohol and Cigarette Exposure on Offspring Substance Use in Multiplex, Alcohol-Dependent Families. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 38(12):2952–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters EN, Budney AJ, Carroll KM. (2012). Clinical correlates of co-occurring cannabis and tobacco use: A systematic review. Addiction. 107(8):1404–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters EN, Schauer GL, Rosenberry ZR, Pickworth WB. (2016). Does marijuana “blunt” smoking contribute to nicotine exposure?: Preliminary product testing of nicotine content in wrappers of cigars commonly used for blunt smoking. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 168:119–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters EN, Schwartz RP, Wang S, O’Grady KE, Blanco C. (2014). Psychiatric, psychosocial, and physical health correlates of co-occurring cannabis use disorders and nicotine dependence. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 134:228–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson AV Jr, Leroux BG, Bricker J, et al. (2006). Nine-year prediction of adolescent smoking by number of smoking parents. Addictive Behaviors. 31 (5):788–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porath AJ, Fried PA, (2005). Effects of prenatal cigarette and marijuana exposure on drug use among offspring. Neurotoxicology & Teratology. 27, 267–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ream GL, Benoit E, Johnson BD, Dunlap E (2008). Smoking tobacco along with marijuana increases symptoms of cannabis dependence. Drug & Alcohol Dependence 95:199–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts KH, Munafo MR, Rodriguez D, Drury M, Murphy MF, Neale RE, Nettle D. (2005). Longitudinal analysis of the effect of prenatal nicotine exposure on subsequent smoking behavior of offspring. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 7(5):801–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins L, Cottler L, Bucholz K, Compton W, North C, Rourke K. (2000). Diagnostic Interview Schedule forDSM-IV Washington University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry; St. Louis. [Google Scholar]

- Robins L, Helzer J, Croughan J, Ratcliff K (1981). National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: Its history, characteristics, and validity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 38:381–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydell M, Cnattingius S, Granath F, Magnusson C, Galanti MR. (2012). Prenatal exposure to tobacco and future nicotine dependence: population-based cohort study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 200(3):202–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer GL, Berg CJ, Kegler MC, Donovan DM, Windle M. (2015). Assessing the overlap between tobacco and marijuana: Trends in patterns of co-use of tobacco and marijuana in adults from 2003–2012. Addictive Behaviors. 49:26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenassa ED, Papandonatos GD, Rogers ML, Buka SL. (2015). Elevated risk of nicotine dependence among sib-pairs discordant for maternal smoking during pregnancy: evidence from a 40-year longitudinal study. Epidemiology. 26, 441–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheslow D, Adams W (1990). Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning: Administration Manual. Wilmington, DE, Jastak. [Google Scholar]

- Sonon KE, Richardson GA, Cornelius JR, Kim KH, Day NL. (2015). Prenatal marijuana exposure predicts marijuana use in young adulthood. Neurotoxicology & Teratology. 47, 10–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonon K, Richardson GA, Cornelius J, Kim KH, Day NL, (2016). Developmental pathways from prenatal marijuana exposure to Cannabis Use Disorder in young adulthood. Neurotoxicology & Teratology. 58, 46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, 1979. Preliminary Manual for the State-Trait Personality Inventory Center for Research in Behavioral Medicine and Health Psychology, University of South Florida, Tampa FL. [Google Scholar]

- Strong DR, Myers MG, Pulvers K, Noble M, Brikmanis K, Doran N. (2018). Marijuana use among US tobacco users: Findings from wave 1 of the population assessment of tobacco health (PATH) study. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 186:16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan KM, Bottorff J, Reid C. (2011). Does mother’s smoking influence girls’ smoking more than boys’ smoking? A 20-year review of the literature using a sex- and gender-based analysis. Substance Use & Misuse. 46(5):656–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran NT, Najman JM, Hayatbakhsh R. (2015a). Predictors of maternal drinking trajectories before and after pregnancy: evidence from a longitudinal study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 55(2):123–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran NT, Williams GM, Alati R, Najman JM. (2015b). Trajectories and predictors of alcohol consumption over 21 years of mothers’ reproductive life course. SSM-Population Health. 1:40–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timberlake DS (2009). A comparison of drug use and dependence between blunt smokers and other cannabis users. Substance Use & Misuse 44:401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Ellickson PL, Orlando M, Klein DJ. (2006). Cigarette smoking from adolescence to young adulthood: women's developmental trajectories and associates outcomes. Womens Health Issues. 16, 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen-Smit E, Verdurmen JE, Engels RC, Vollebergh WA. (2105). The role of general parenting and cannabis-specific parenting practices in adolescent cannabis and other illicit drug use. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 147:222–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walden B, Iacono WG, McGue M. (2007). Trajectories of change in adolescent substance use and symptomatology: Impact of paternal and maternal substance use disorders. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 21(1):35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JB, Ramo DE, Lisha NE, Cataldo JK. (2016). Medical marijuana legalization and cigarette and marijuana co-use in adolescents and adults. Drug & Alcohol Dependence 166:32–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Platt J, Copeland J, Goodwin RD. (2018). Is Cannabis use associated with increased risk of cigarette smoking initiation, persistence, and relapse? Longitudinal data from a representative sample of US adults. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 79(2): 17m11522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Warner V, Wickramaratne PJ, Kandel DB (1999). Maternal smoking during pregnancy and psychopathology in offspring followed to adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 38(7):892–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]