Abstract

The objective of this study was to compare and evaluate the efficacy of collagen-based sponge compared to commercial collagen sponge as a potent open wound-dressing material. In this study, 10 mm diameter skin incision was made on lateral side of rats. The wound was monitored regularly until day 12. Histopathology results revealed the faster re-epithelialization and lesser inflammatory cells, and also masson’s trichrome staining showed that collagen fibrils were horizontal and interwoven in collagen-based sponge group. The expression of growth factors such as VEGF and TGF-β1 was found to be upregulated in transcriptional and translational levels, suggesting the importance of collagen-based sponge as a potent wound-healing material. Furthermore, IL-6 and TNF-α in the wound tissue were significantly down-regulated in 2 and 6 days in collagen-based sponge group and anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 level was found to be upregulated throughout 12 days. These results cumulatively revealed that collagen-based sponge may serve as novel material for wound healing in the animal model.

Keywords: Wound healing, Cytokines, Growth factors, Collagen sponge, Histology

Introduction

Any deleterious or physical damage to skin considered as wound. The recent development in the wound research management has significantly enhanced our knowledge of the wound healing mechanism. Appropriate wound repair system is necessary to gain proper functional skin. There are four major phases involved in the repair of injured tissue includes hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling (Gosain and Dipietro 2004; Li et al. 2007). The inflammatory phase and hemostasis are simultaneous, and are characterized by release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, reactive oxygen species, and several growth factors including the transforming growth factor (TGF-β), insulin-like growth factor-1, and epidermal growth factor (EGF). These growth factors are involved in activating fibroblast, endothelial cells, and macrophages around the wound and subsequently aids in wound cleaning. Initially, the cytokines released by macrophages and promote inflammatory response by activating additional leukocytes. Macrophages are also responsible for clearing apoptotic cells. As they clearing the apoptotic cells, macrophages undergo phenotypic transition which stimulates the fibroblasts, angiogenesis, and keratinocytes to promote tissue regeneration. Proliferative phase generally overlaps with the inflammatory phase and is characterized by re-epithelialization in the wound. Fibroblast and endothelial cells are the prominent in the representative dermis, which supports capillary growth and formation of granulation tissue at the wound site. Remodeling is considered as the fourth phase in wound healing which may last for years (Clark 1996; Campos et al. 2008; Guo and Dipietro 2010).

All stages of the wound repair process are controlled by a large number of regulatory molecules including cytokines and growth factors. Failure to resolve inflammation can lead to chronic non-healing wounds. Similarly, uncontrolled matrix accumulation leads to excess scarring and fibrotic sequelae. During the inflammation, neutrophil recruitment at wound site peaked around 24–48 h post wounding, and activation of this cell results in enhanced release of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1 cytokines. The activated inflammatory cells are susceptible to TGF-β1 mediated suppression to reverse the inflammatory process (Finnson et al. 2013). IL-10 is considered as a key anti-inflammatory cytokine that reduces inflammatory response (Gordon et al. 2008). Overexpression of IL-10 and TGF-β tends to promote scarless healing (Sanjabi et al. 2009).

Collagen is the most abundant protein that widely used in various applications, and the use of collagen as a biomaterial began in 1881. In addition, collagen plays a vital role in maintaining the biological and structural integrity of the extracellular matrix and tissue function (Ruszczak 2003; Aszodi et al. 2006). Highly stable collagen fibers can be made with cross-linking and self-aggregation, which can be formulated into numerous scaffolds of high utility. The collagen-based biomaterial for wound-healing study has been elaborately addressed (Chattopadhyay and Raines 2014). To date, various polymeric materials have been utilized for wound healing applications. A potent wound healing material should have significant features of high healing efficacy, anti-scar formation, in addition to providing a favorable environment for wound management (Zahedi et al. 2010). In the present study, we demonstrated the extent of collagen-based sponge as an active wound material, based on faster re-epithelialization, increased expression of growth factors, lesser levels of inflammatory cells, and pro-inflammatory cytokines in-vivo wound-healing model.

Materials and methods

Preparation of collagen-based sponge

The gentamicin-containing collagen sponge was prepared and supplied by the manufacturer (BB Healthcarte Co. Ltd., Seoul, Republic of Korea). The collagen-based sponge was prepared from bovine achilles tendons, which contain predominantly type I collagen. Briefly, the tendons were milled and treated with a number of reagents including sodium hydroxide, which inactivate microorganisms. Then, the tendons were digested with pepsin at pH 2.5 to degrade contaminating proteins and to cause detachment of non-helical portions of the collagen molecule (telopeptides). The digested tendons were separated from undigested tendon fragments, centrifuged and re-suspended. Gentamicin sulfate was added to collagen solution and pH was adjusted to induce in vitro fibrillogenesis. The solution was then dispensed into trays. The final collagen sponge was prepared by freeze-drying these preparations into 5 × 5 × 0.5 cm sponge containing 70 mg of collagen type I and 50 mg of gentamicin sulfate.

Animals and wound creation

Adult male Sprague Dawley rats aged 8 weeks and weighing 250 ± 20 g were chosen for the experiment. All rats were purchased from Koatech (Seoul, Republic of Korea) and had a free access to diet and water. All the experiments performed in this work were approved by the Chonbuk national university animal ethical and use committee. Animals were acclimatized for a week at lab conditions before the commencement of the experiments. An open excision wound was made using a biopsy punch tool with a 10 mm diameter and rats were divided into following three groups.

The wound control group was administered with physiological saline (n = 15).

In study group, collagen-based sponge was inserted surgically and sutures were made to position the sponge on the wound surface (n = 15).

In positive control group, commercial collagen sponge was surgically inserted and sutures were made to position the sponge on the wound surface (n = 15).

On days 2, 6, and 12, five animals from each group were sacrificed with a high dose of diethyl ether. The wound area from each group was carefully excised and divided into three parts. One part is kept in RNAlater® (Sigma-Aldrich) solution and placed at − 20 °C for RNA expression studies. The second part was stored at − 80 °C for protein analysis and the third part was preserved in 10% buffered formalin for histopathological studies.

Photography and wound healing

Wound of all animals was photographed on days 0, 3, 6, 9, and 12. The periphery of wounds was traced using a transparent paper with the help of a marker. The area of each wound was calculated planimetrically and the percentage of wound contraction was calculated according to Wilson formula as follows:

Histology of wound tissue

Re-epithelialized skin from various groups was collected on days 2, 6, and 12 post-wounding. Samples were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 48 h. Five micrometer thick sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) according to standard protocol. The tissue sections were observed under the microscope at 100x magnification. The stained sections were scored for inflammatory cells from 0 to 4 numerical scale (Hunt and Mueller 1994; Hajiaghaalipour et al. 2013), and the scores were 0 for absence, 1 for occasional presence, 2 for light scattering, 3 for abundance, and 4 for confluence of cells, and the epithelialization was graded from 0 to 3 according to Abramov et al. (2007). Collagen fibril deposition at wound site was measured using modified Masson’s trichrome staining kit (Scy Tek, USA).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The skin tissue at the wound area was dissected and stored at − 80 °C. The tissue was finely chopped and extracted using cell lysis buffer (Pro-prep Intron Biotechnology, Korea) and the supernatant was used to analyze the content of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 (R&D systems, USA) in various groups.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction for growth factors

Wound tissues from at least 3 rats from each group were used for this study. Total RNA was extracted using RNA easy mini kit (Qiagen, Germany) and complementary DNA synthesis was carried out with power cDNA synthesis kit (Intron Biotechnology, Korea) according to manufacturer’s protocol. The gene expression was quantified using SYBR green real-time PCR master mix (TOYOBO, Japan) with respective primers in a Real-Time PCR (Applied Biosystems) system. The qPCR was performed with the primers for the VEGF (F:5′-GCCAGCACATAGGAGAGATGAG-3′; R:5′-ACCGCCTTGGCTTGTCAC-3′); TGF-b1 (F: 5′-AAGTGGATCCACGAGCCCAA-3′; R:5′-GCTGCACTTGCAGGAGCGCA-3′) and β-actin (F:5′-TCCTAGCACCATGAAGATCAA G-3′; R: 5′- ACTCATCGTACTCCTGCTTG-3′) for internal control. ΔΔCT method was employed to determine the fold change in the expression (Livak and Schmitten 2001).

Protein-level expression of VEGF and TGF-β

Western blot analysis was carried out to study the expression level of important growth factors like VEGF and TGF-β during the wound-healing process. Tissue was lysed using cell lysis buffer and the equal amount of protein was loaded and resolved in 12% SDS gel. The protein was transferred to a PVDF membrane and blocked using 5% skimmed milk in TBST [Tris-buffered saline-Tween-20 (0.1%)]. The membrane was probed with primary antibodies to VEGF and TGF-β (Cell Signaling). β-actin (Abcam) served as a loading control to normalize the expression. Anti-rabbit HRP conjugated secondary antibody was used along with Lumi pico solultion (DoGen, Korea) to detect chemiluminescence from respective bands. The protein band was quantified for their intensity using the ImageJ software (ver.1.49).

Statistical analysis

All data expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of the mean. The data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA method followed by unpaired student’s t test using sigma plot 10 software. Statistically significant differences were considered at *P ≤ 0.05 and **P ≤ 0.01.

Results and discussion

Observation of wound closure

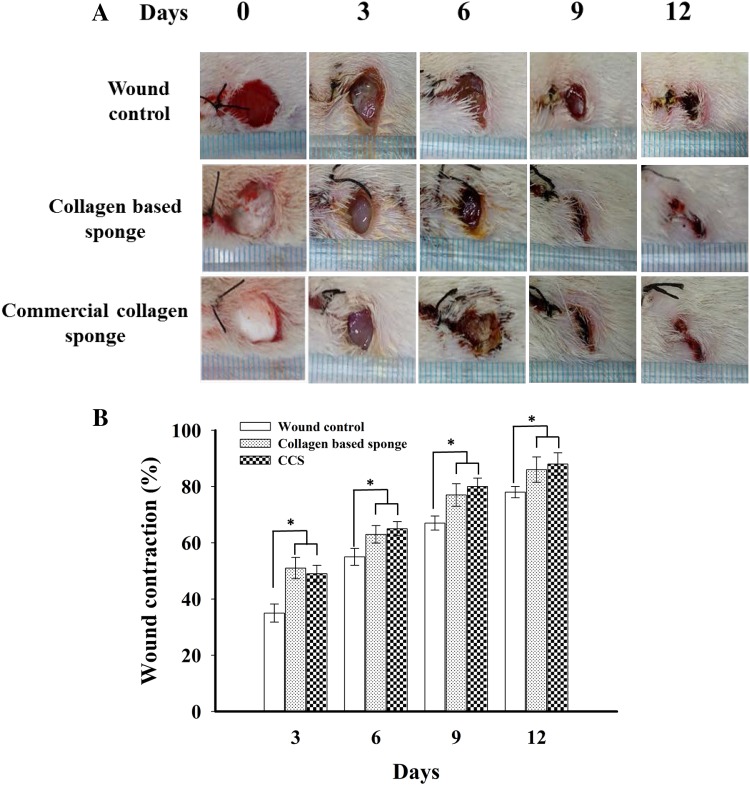

Visual observation of wound healing pattern was obtained by taking photographs at a constant interval using a digital camera. All animals from three groups were photographed at the same time. Figure 1a shows the photographs of wound control, collagen-based sponge, and commercial collagen sponge-treated groups in various time periods. As observed from the results, collagen-based sponge and commercial collagen sponge-treated wounds exhibited an increased efficacy of wound healing when compared to wound control group. The collagen-based sponge treated wounds exhibited faster epithelialization similar to positive control group. The macroscopic observation and planimetric results are positively correlated. Periodic observation of the wound area by planimetry method disclosed that the faster wound healing was observed in collagen-based sponge treated wounds for 12 days. A wound size reduction of ~ 90% was observed in collagen-based sponge treated group, whereas it was ~ 75% in wound control group (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Representative photographs (a) and wound contraction % (b) for wound control, collagen-based sponge and commercial collagen sponge (CCS)-treated groups were showed on day 3, 6, 9, and 12 after wounding. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 5). *P < 0.05 compared to wound control group

Histological staining

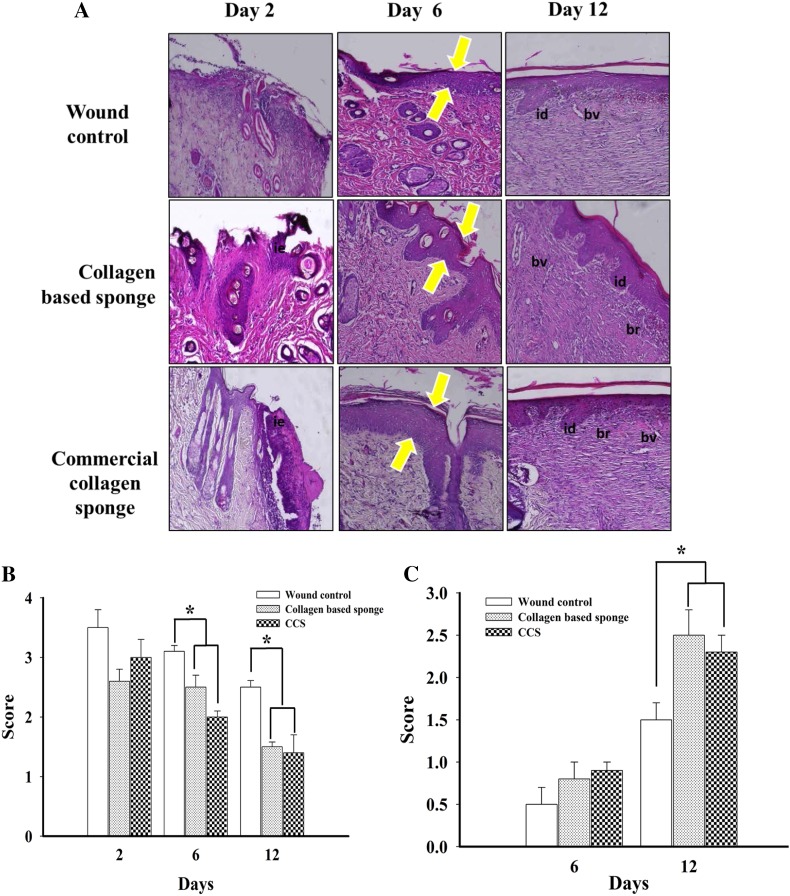

Wound healing is the dynamic process that consists of four phases namely hemostasis inflammation, tissue formation, and tissue remodeling (Gosain and DiPietro 2004; Guo and Dipietro 2010). To understand the efficacy of collagen-based sponge with respect to commercial collagen sponge in promoting wound healing, the re-epithelialized tissue of each group was investigated histologically. The increase in the thickness of granulation tissue, the extent of newly formed epithelium and collagen deposition, and the decrease in the number of inflammatory cells are considered as progress in the healing process. The microscopic images of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) are presented in Fig. 2a.

Fig. 2.

Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain for histologic wound of control, collagen-based sponge and commercial collagen sponge groups on days 2, 6, and 12 after wounding (× 100 magnification) (a), histologic scoring for inflammatory infiltrate (0–4) (b), the score for epithelialization (0–3) in each group (c), and masson’s trichrome staining of each group indicating the deposition of collagen fibril on various days (× 100 magnifications) were shown (d). Arrow indicated the hypertrophy of the epithelium (a) and collagen fibril deposition (d). bv = blood vessels; id = inter digitization; ie = immature epidermis; br = boundary between unhealed and healed tissue. *P < 0.05 compared to wound control group. CCS; commercial collagen sponge

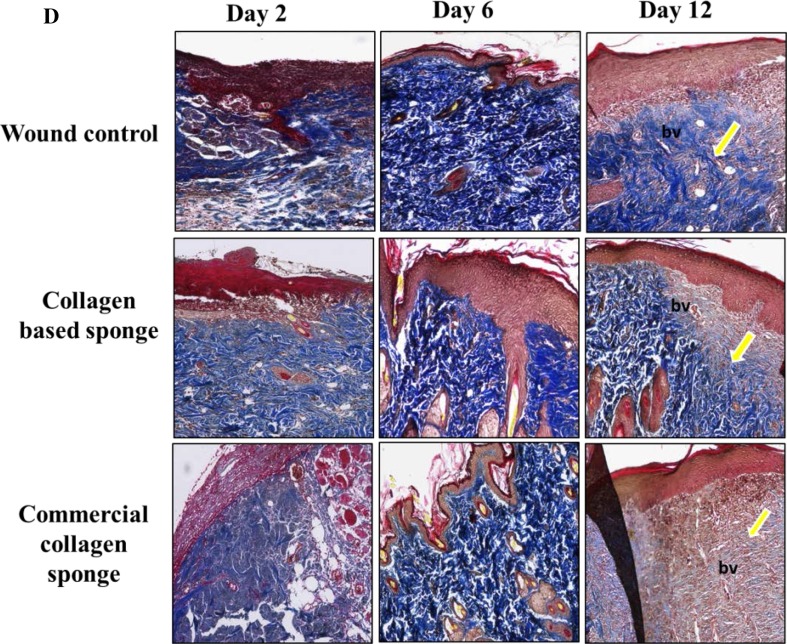

Until day 6, wound exudates were found on the upper layer skin in all three groups. On day 12, granulated tissue was more compact on the collagen-based sponge group, which almost equals the positive group, and both groups found to have more granulated tissue compared to wound control group. The neovascularization in granulated tissue was found to be significantly higher in collagen-based sponge group than wound control. On day 6, collagen-based sponge-treated tissue showed thicker granulation tissue with fewer inflammatory cells; in other hand, wound control shown to have higher number of inflammatory cells. In addition, collagen-based sponge-treated wound group found to have a continuous epidermal layer on the surface. Further treatment enhanced the deposition of collagen fibril. The collagen fibrils were almost oblique and parallel in wound control group, whereas the fibers were horizontal and interwoven in collagen-based sponge group, indicating faster growth and increased tensile strength at the wound site (Fig. 2d).

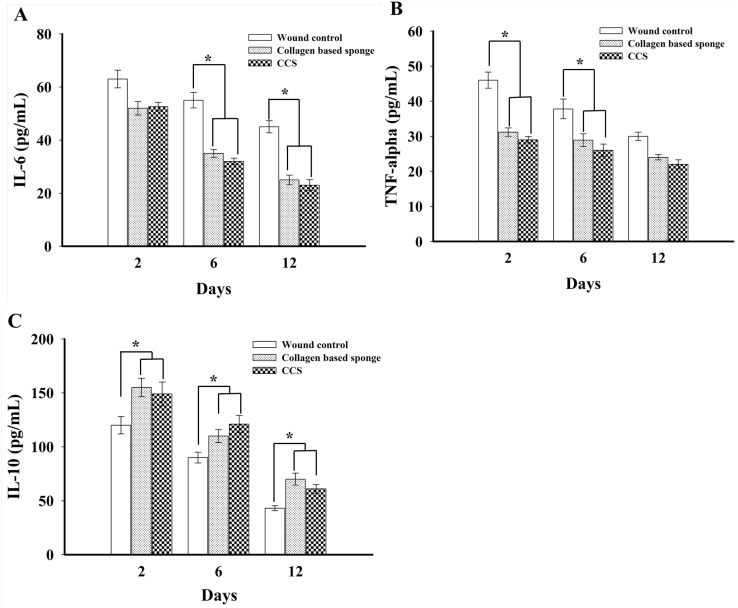

Expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines

To study the mechanism of action, we quantify the expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines on wound tissue. The collagen-based sponge group shown to express reduced levels of the IL-6 and TNF-α when compared to wound control group (Fig. 3a, b). In particular, IL-6 expression significantly reduced on 6 and 12 days in collagen-based sponge group. TNF-α level was found to be down regulated in collagen-based sponge group compared with wound control, time-dependent manner. IL-10, anti-inflammatory cytokine, was significantly up regulated throughout the period of study, which indicates better healing in collagen-based sponge treatment groups (Fig. 3c). Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α play a vital role in wound healing. These cytokines involves the stimulation of fibroblast proliferation and chemotaxis. Expression of IL-6 and TNF-α was shown to upregulated during the inflammatory phase of healing (Grellner et al. 2000; Zubaidi et al. 2015). The wound healing study in IL-6 knockout mice and IL-1 receptor antagonist showed longer duration to heal than the wound control group (Gallucci et al. 2000; Ishida et al. 2006). In a similar research, IL-6−/− mice exhibited a delay in wound closure and often had open wounds. The wounds were tending to expand beyond the original boundaries (McFarland-Mancini et al. 2010). The role of TNF-α in wound healing has been well characterized; furthermore, it is known to involved in the earlier stage of wound healing rather than the late stage, especially the first several hours following the wound until day 1. A study with neutralizing antibodies to TNF-α at early stage of wound displayed a delayed healing compared to control mice (Ritsu et al. 2017). In addition, the roles of anti-inflammatory cytokines have also shown to play a vital role in wound healing. In a study using neutralized antibodies to IL-10 shown to inhibit infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages towards wound site, as well as it helps to develop wound mechanical strength by improving matrix deposition and maturation.

Fig. 3.

ELISA analysis of pro-inflammatory (a, b) and anti-inflammatory cytokines (c) from each group from wound tissue on days 2, 6, and 12 were shown. Data expressed as mean ± SD in each group. *P < 0.05 compared to wound control group. CCS; commercial collagen sponge

Taken together, our study suggests that administration of collagen-based sponge inhibited the level of IL-6 and TNF-α, and enhanced the expression of IL-10 in study group than the wound control. These results are in accordance with the previous reports which unveiled the importance of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines for wound healing.

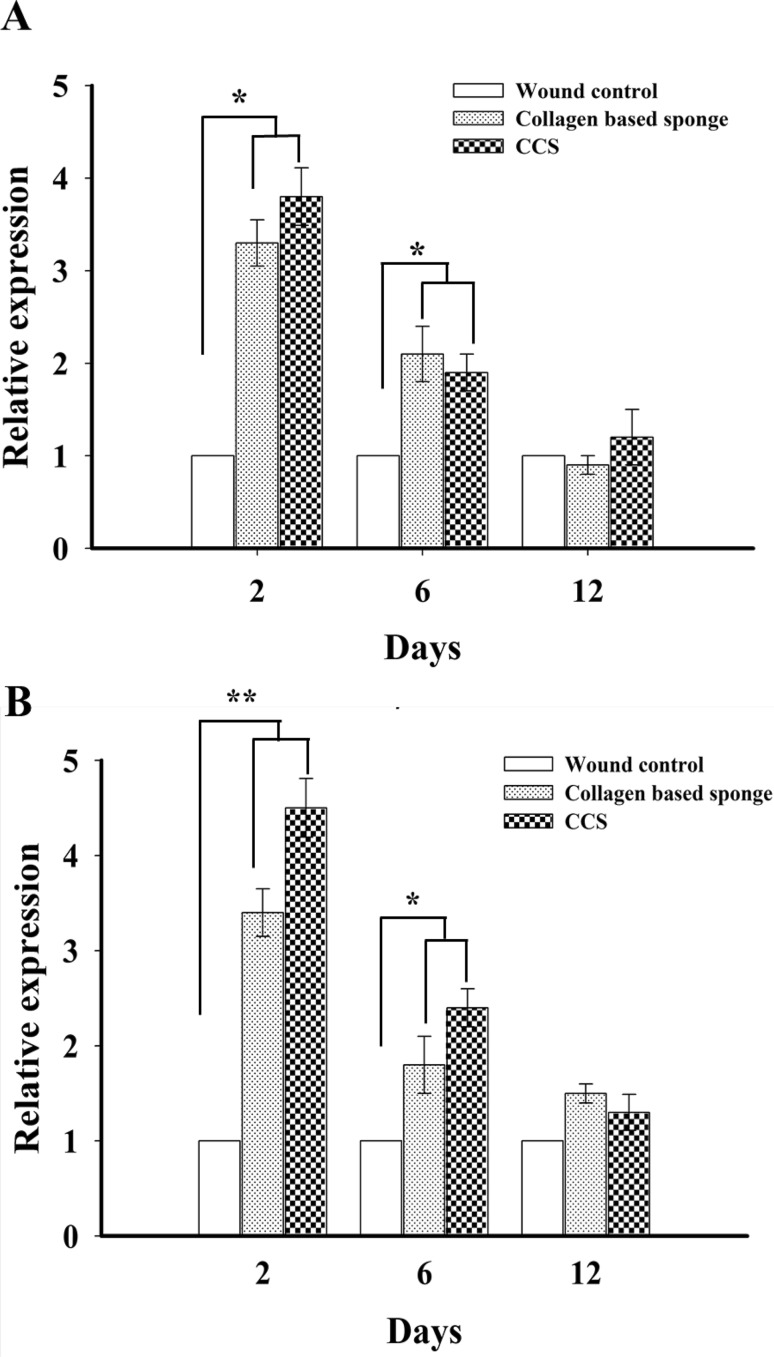

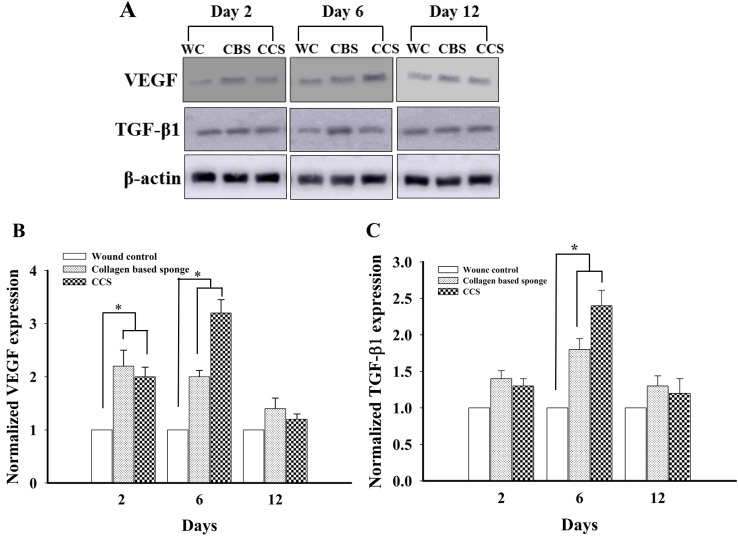

Expression of growth factors in the transcriptional and translational levels

Expression of mRNA level of VEGF and TGF-β1 following collagen-based sponge administration significantly increased compared to wound control group; however, there is no difference was observed between collagen-based sponge and commercial collagen sponge group on 2 and 6 days. Furthermore, this level was down-regulated on 12 days (Fig. 4), and similar trend was observed in the protein expression of VEGF and TGF-β1 in collagen-based sponge and commercial collagen sponge-treated groups (Fig. 5). The presence of VEGF proven to persuade angiogenesis by inducing endothelial cell proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis (Ferrara 2001). TGF-β1 involves in the proliferation of endothelial cells indirectly by recruiting VEGF expressing hematopoietic effector cells (Fang et al. 2012) or by enhancing the expression of VEGF synthesis via Akt and ERK pathways (Dijke and Arthur 2007). The independent action of TGF-β1 can also be demonstrated to induce neovessel growth in embryonic stem-cell differentiation model (Mallet et al. 2006). The role of VEGF-A in wound healing was revealed in a previous study, where neutralizing VEGF-A antibodies caused a remarkable reduction in granulation tissue formation, angiogenesis, fluid accumulation, in a pig wound model (Howdieshell et al. 2001). In similar condition, the vital role of TGF-β1 in wound healing has been clearly demonstrated in TGF-β1 knock out mice, where it showed no difference in wound healing until 3 weeks and exhibited late stage developmental impairment leading to severe wasting syndrome and a pronounced inflammatory response resulting in a multiple organ failure (Kulkarni et al. 1993; Grose and Werner 2004). In our study, the presence of collagen-based sponge on the surface of the wound enhanced the expression of VEGF and TGF-β1, which in turn reveals the faster wound healing, and these results are in line with the previous reports which unveiled the importance of growth factors in wound healing.

Fig. 4.

RT-PCR analysis of growth factors VEGF (a) and TGF-β 1 (b) in wound control, collagen-based sponge and commercial collagen sponge group. The expression of growth factors were normalized to β-actin and levels were calculated from mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared to wound control group. CCS; commercial collagen sponge

Fig. 5.

Representative images of VEGF, TGF-β1 and β-actin using western blotting from wound control, collagen-based sponge and commercial collagen sponge groups, on day 2, 6 and 12 (a). Semi quantitative protein levels of VEGF (b) and TGF- β1 (c) in different groups were shown. *P < 0.05 compared to wound control group. WC; wound control, CBS; collagen based sponge, CCS; commercial collagen sponge

Conclusions

Collagens-based dressings are come in pads, gels, or particle and promote deposition of newly formed collagen in the wound bed, and they provide a moist environment, and in addition, they absorb exudates. Our collagen-based sponge exhibited superior quality in healing the wound in a faster way by suppressing the anti-inflammatory cytokines and enhancing the IL-10, which helps in scare less wound repair. Quicker re-epithelization properties along with interwoven collagen fibril formation suggested the role of collagen-based sponge as a potent dressing material. The collagen-based sponge prepared in this study served, as efficient as commercial collagen sponge in all aspects. Therefore, we believe that the collagen-based sponge can be used as a dressing material in veterinary clinic to treat open wounds. However, our present study shows the results for administration of collagen-based sponge for only 12 days using rodent model. Therefore, further studies surely need to be carried out to give assurance that these results can be used for humans. In the point of the safety and efficacy of the collagen-based sponge, prospective additional studies should be considered.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Abramov Y, Golden B, Sullivan M, Botros SM, Millet JJ, Alshahrous A, Goldberg RP, Sand PK. Histologic characterization of vaginal vs. abdominal surgical wound healing in a rabbit model. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15:80–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2006.00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aszodi A, Legate KR, Nakchbandi I, Fassler R. What mouse mutants teach us about extracellular matrix function. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:591–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos AC, Groth AK, Branco AB. Assessment and nutritional aspects of wound healing. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11:281–288. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3282fbd35a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay S, Raines RT. Collagen-based biomaterials for wound healing. Biopolymers. 2014;101(8):821–833. doi: 10.1002/bip.22486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RAF. Wound repair: overview and general considerations in the molecular and cellular biology of wound repair. New York: Plenum; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dijke PT, Arthur HM. Extracellular control of TGF-beta signalling in vascular development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:857–869. doi: 10.1038/nrm2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang S, Pentinmikko N, Ilmonen M, Salven P. Dual action of TGF-beta induces vascular growth in vivo through recruitment of angiogenic VEGF-producing hematopoietic effector cells. Angiogenesis. 2012;15:511–519. doi: 10.1007/s10456-012-9278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor in regulation of physiological angiogenesis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C1358–C1366. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.6.C1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnson KW, McLean S, Di Guglielmo GM, Philip A. Dynamics of transforming growth factor beta signaling in wound healing and scaring. Adv Wound Care. 2013;2(5):195–214. doi: 10.1089/wound.2013.0429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallucci RM, Simeonova PP, Matheson JM, Kommineni C, Guriel JL, Sugawara T, Luster MI. Impaired cutaneous wound healing in interleukin-6-deficient and immunosuppressed mice. FASEB J. 2000;14:2525–2531. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0073com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon A, Kozin ED, Keswani SG, Vaikunth SS, Katz AB, Zoltick PW, Favata M, Radu AP, Soslowsky LJ, Herlyn M, Crombleholme TM. Permissive environment in postnatal wounds induced by adenoviral-mediated overexpression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 prevents scar formation. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16(1):70–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosain A, Dipietro LA. Aging and wound healing. World J Surg. 2004;28:321–326. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-7397-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grellner W, Georg T, Wilske J. Quantitative analysis of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1beta, IL-6, TNF-alpha) in human skin wounds. Forensic Sci Int. 2000;113:251–264. doi: 10.1016/S0379-0738(00)00218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grose R, Werner S. Wound-healing studies in transgenic and knockout mice. Mol Biotechnol. 2004;28:147–166. doi: 10.1385/MB:28:2:147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Dipietro LA. Factors affecting wound healing. J Dent Res. 2010;89:219–229. doi: 10.1177/0022034509359125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajiaghaalipour F, Kanthimathi MS, Abdulla MA, Sanusi J. The effect of Camellia sinensis on wound healing potential in an animal model. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:386734. doi: 10.1155/2013/386734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howdieshell TR, Callwayd WWL, Gaines MD, Procter CDJR, Sathyanarayana Pollock JS, Brock TL, Brock TL, Mcneil PL. Antibody neutralization of vascular endothelial growth factor inhibits wound granulation tissue formation. J Surg Res. 2001;96:173–182. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt T, Mueller R. Wound healing. In: Way LW, editor. Current surgical diagnosis and treatment. Paramus: Appleton and Lange; 1994. p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- Ishida Y, Kondo T, Kimura A, Matsushima K, Mukaida N. Absence of IL-1 receptor antagonist impaired wound healing along with aberrant NF-kappaB activation and a reciprocal suppression of TGF-beta signal pathway. J Immunol. 2006;176:5598–5606. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni AB, Huh C-G, Becker D, Geiser A, Lyght M, Flanders KC, Roberts AB, Sporn MB, War DJM, Karlsson S. Transforming growth factor β1 null mutation in mice causes excessive inflammatory response and early death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:770–774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Chen J, Kirsner R. Pathophysiology of acute wound healing. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25(1):9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmitten TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet C, Vittet D, Feige JJ, Bailly S. TGFbeta1 induces vasculogenesis and inhibits angiogenic sprouting in an embryonic stem cell differentiation model: respective contribution of ALK1 and ALK5. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2420–2427. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland-Mancini MM, Funk HM, Paluch AM, Zhou M, Giridhar PV, Mercer GA, Kozma C, Drew F. Differences in wound healing in mice with deficiency of IL-6 versus IL-6 Receptor. J Immunol. 2010;184:7219–7228. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsu M, Kawakami K, Kanno E, Tanno H, Ishii K, Imai Y, Maruyama R, Tachi M. Critical role of tumor necrosis factor-α in the early process of wound healing in skin. J Dermatol Dermatol Surg. 2017;21(1):14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jdds.2016.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruszczak Z. Effect of collagen matrices on dermal wound healing. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2003;55(12):1595–1611. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanjabi S, Zenewicz LA, kamanaka M, Flavell RA. Anti-and pro-inflammatory Roles of TGF-β, IL-10, and IL-22 in immunity and autoimmunity. Curr Opin Pharmcol. 2009;9:447–453. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahedi P, Rezaeian I, Ranaei-Siadat SO, Jafari SH, Supaphol PA. review on wound dressing with an emphasis on electrospun nanofibrous polymeric bandages. Polym Adv Technol. 2010;21:77–95. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8831(09)00247-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zubaidi AM, Hussain T, Alzoghaibi MA. The time course of cytokine expressions plays a determining role in faster healing of intestinal and colonic anastomatic wounds. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:412–417. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.153819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]