Abstract

Whole-genome sequencing was used to analyze the profiles of isoniazid (INH) resistance-related mutations among 188 multidrug-resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MDR-TB) and mono-INH-resistant isolates collected in a recent Chinese national survey. Mutations were detected in 18 structural genes and two promoter regions in 96.8% of 188 resistant isolates. There were high mutation frequencies in katG, the inhA promoter, and ahpC-oxyR regulator regions in INH-resistant isolates with frequencies of 86.2%, 19.6%, and 18.6%, respectively. Moreover, a high diversity of mutations was identified as 102 mutants contained various types of single or combined gene mutations in the INH-resistant group of isolates. The cumulative frequencies of katG 315 or inhA-P/inhA mutations was 68.1% (128/188) for the INH-resistant isolates. Of these isolates, 46 isolates (24.5% of 188) exhibited a high level of resistance. A high level of resistance was also observed in 21 isolates (11.2% of 188) with single ahpC-oxyR mutations or a combination of ahpC-oxyR and katG non-315 mutations. The remaining 17 mutations occurred sporadically and emerged in isolates with combined katG mutations. Such development of INH resistance is likely due to an accumulation of mutations under the pressure of drug selection. Thus, these findings provided insights on the levels of INH resistance and its correlation with the combinatorial mutation effect resulting from less frequent genes (inhA and/or ahpC). Such knowledge of other genes (apart from katG) in high-level resistance will aid in developing better strategies for the diagnosis and management of TB.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is caused by infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis and represents one of the greatest threats to human health worldwide, and it is associated with 1.4 million deaths annually (2016 WHO report). As a component of first-line TB drugs, isoniazid (INH) is used both for the treatment of active TB and as a preventive therapy for latent infections1. The emergence of INH-resistant M. tuberculosis strains readily leads to the development of multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB; M. tuberculosis strains resistant to INH and rifampicin)2. Thus, the transmission of MDR-TB presents a challenge for both TB treatment and prevention globally. A rapid molecular diagnosis is an important strategy for preventing both the transmission of resistant strains and further development of drug resistance during TB treatment. However, a clear understanding of the underlying mechanisms of resistance and the identification of new markers for the diagnosis of drug-resistant TB are required.

INH is a prodrug activated by catalase-peroxidase, which is encoded by katG3. The molecular basis of INH resistance in M. tuberculosis was first revealed by the identification of katG deletion in clinical INH-resistant isolates4. INH resistance also involves several genes in multiple biosynthetic networks and pathways5. Activated INH functions by attacking a series of components involved in the biosynthesis of mycolic acids, such as NADH-dependent enoyl ACP synthase (encoded by inhA), β-ketoacyl ACP synthase (encoded by kasA), malonyl-CoA acyl carrier protein (ACP) transacylase (fabD), and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (accD6)6,7. Thus, M. tuberculosis strains with mutations in these genes may develop INH resistance5. In addition, 15 other structural genes and regulator regions have also been found to be involved in INH resistance8. For example, mutations in peroxiredoxin alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit C (ahpC) and the ahpC-oxyR intergenic regulatory region have been identified in INH-resistant isolates6. Moreover, the ferric uptake regulator gene (furA) and several efflux protein-encoding genes (iniABC and efpA) have been shown to be mutated in INH-resistant M. tuberculosis isolates9–12. Investigators have also studied other efflux (mmpL family) genes and their significance in INH resistance13. Additionally, mutations in trehalose dimycolyl transferase (fbpC), a regulatory gene governing the expression of a polyketide synthase (srmR), as well as in Rv0340, Rv1592c, Rv1772, fadE24, ndh, and nat have been identified in resistant M. tuberculosis strains14–17.

Although a variety of genes is involved in M. tuberculosis resistance to INH, there is data to support that frequent mutations are primarily focused in the katG, inhA, and ahpC-oxyR regulator regions18. Information regarding other gene mutations is limited because it is challenging to simultaneously acquire all gene sequences related to INH resistance in a collection of isolates, which creates a gap in the understanding of the accumulation of several gene mutations in the development of INH-resistance during TB treatment. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) was used to analyze the mutation profile of 22 known genes in clinical M. tuberculosis isolates. In the present study, 188 MDR isolates and mono-INH-resistant isolates were selected from a collection generated in a national survey19. The occurrence of MDR-TB strains is largely associated with the development of INH mono-resistance under the continuous pressure of drug selection during TB treatment20. The high degree of polymorphisms among these mutations provides an opportunity to study the relationship between mutations and the level of phenotypic resistance. The aim of the present study was to explore the profile of gene mutations related to INH resistance in MDR-TB isolates. Comparing the degree of phenotypic drug resistance among these isolates revealed the influence of accumulated gene mutations in M. tuberculosis strains during the development of INH resistance in patients with MDR-TB. Identification of high levels of mutations associated with resistance helps to establish new reliable molecular methods for the detection of INH drug resistance.

Results

Scanning the whole-genome sequence resulted in detection of drug resistance-related mutations in 18 structural genes and two promoter regions in 96.8% (182/188) of the INH-resistant isolates (Table 1). Mutations in katG were detected in 86.2% (162/188) of the INH-resistant isolates. Mutations in the inhA/inhA promoter (inhA-P) and ahpC-oxyR regulator region occurred in 19.6% (37/188) and 18.6% (35/188) of isolates, respectively. These three gene loci were regarded as highly frequent gene loci. The occurrence of the remaining genes ranged from 0.53% to 4.26% of isolates and were classified as low frequent genes.

Table 1.

Mutation frequencies for multiple INH resistance-related genes and regulator regions

| Gene locus | Functional description | Frequency (n = 188) (%) | MDRa | mono-Rb | Types of mutations | Substitution | Deletions | SNP in susceptiblec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| katG (Rv1908c) | Catalase-peroxidase-peroxynitritase | 86.17 | 144 | 18 | 59 | 57 | 2 | R463L |

| inhA-promoter | Promoter region | 19.15 | 34 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 0 | — |

| ahpC-oxyR (Rv2427-2428) | Regulator region | 18.62 | 33 | 2 | 11 | 11 | 0 | — |

| inhA (Rv1484) | NADH-dependent enoyl-ACP reductase | 2.66 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | — |

| aphC (Rv2428) | Alkyl hydroperoxidase C | 0.53 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | — |

| iniA (Rv0342) | INH-inducible gene | 4.26 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 0 | G178(.) |

| Rv1592c | Unknown | 4.26 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 0 | I322V + E321(.) |

| furA (Rv1909c) | Ferric uptake regulator | 3.72 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 0 | — |

| fabD (Rv2243) | Malonyl-CoA ACP transacylase | 2.66 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | P179A |

| Rv1772 | Unknown | 2.66 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | — |

| nhoA/nat (Rv3566c) | Arylamine N-acetyltransferase | 2.66 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | G207R |

| efpA (Rv2846c) | Efflux protein | 2.13 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | — |

| kasA (Rv2245) | β-Ketoacyl ACP synthase | 2.13 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | H253Y |

| iniC (Rv0343) | INH-inducible gene | 1.60 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | A21(.); P22(.) |

| fadE24 (Rv3139) | Fatty acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | 1.06 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | — |

| srmR (Rv2242) | Regulatory gene | 1.06 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | M323T |

| fbpC (Rv0129c) | Trehalose dimycolyl transferase | 1.06 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | G158S;P237S |

| iniB (Rv0341) | INH-inducible gene | 0.53 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | — |

| ndh (Rv1854c) | NADH dehydrogenase | 0.53 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | — |

| Rv0340 | Unknown | 0.53 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | — |

| accD6 (Rv2247) | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | — | — | ||

| fabG1 (Rv1483) | 3-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein reductase | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | — | — |

aNumber of MDR isolates

bNumber of INH mono-resistant isolates

cThese types of mutations occurred simultaneously in MDR isolates and susceptible isolates, which were not included in the frequency of INH-resistant mutations

A high degree of polymorphism in mutation types was displayed in the collection. There were 102 mutant types, including 28 single-gene mutations and 74 combined gene mutations involved in the 18 INH resistance-related gene loci (Table 2). Single-gene mutations were identified in 83 (49.4% of 168) MDR-TB isolates and 14 (70% of 20) mono-resistant isolates. Two, three, four, and five gene mutations were in 31.9% (60/188), 9.0% (17/188), 2.7% (5/188), and 0.5% (1/188) of the INH-resistant isolates, respectively. Moreover, there were six isolates for which INH resistance-related mutations were not detected.

Table 2.

Occurrence of various combined mutations determined in isolates with different resistance levels

| Combined gene mutations (Gene loci)a | Num. of isolates (%) | Num. of mutant types | Type of isolates | LRb | MRb | HRb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | (0.1 mg/L < MICs ≤ 0.4 mg/L) | (0.8 mg/L ≤ MICs ≤ 3.2 mg/L) | MICs ≥ 6.4 mg/L) | |||

| katG315 | 66(35.11) | 5 | MDR, mono-R | 1 | 42 | 23 | ||||

| katG315 | +inhA-P | 6(3.19) | 4 | MDR | 0 | 0 | 6 | |||

| katG315 | +iniA | 6(3.19) | 3 | MDR, mono-R | 0 | 2 | 4 | |||

| katG315 | + kasA | 3(1.60) | 3 | MDR | 0 | 1 | 2 | |||

| katG315 | + Rv1592c | 3(1.60) | 3 | mono-R | 0 | 2 | 1 | |||

| katG315 | +ahpC-oxyR | 2(1.06) | 2 | mono-R | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||

| katG315 | +fabD | 2(1.06) | 2 | MDR | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||

| katG315 | +furA | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| katG315 | +Rv1772 | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| katG315 | +ndh | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| katG315 | +inhA-P | +Rv1772 | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| katG315 | +fabD | +iniC | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| katG315 | +furA | +Rv1592 | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| katG315 | +iniA | +nat | 1(0.53) | 1 | mono-R | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| katG315 | +iniC | +efpA | +Rv0340 | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| katG315 | +ahpC-oxyR | +fbpC | +fadE24 | +srmR | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| katGnon315 | 16(8.51) | 16 | MDR, mono-R | 5 | 9 | 2 | ||||

| katGnon315 | +inhA-P | 13(6.91) | 8 | MDR | 3 | 8 | 2 | |||

| katGnon315 | +ahpC-oxyR | 13(6.91) | 13 | MDR | 2 | 7 | 4 | |||

| katGnon315 | +Rv1592c | 2(1.06) | 2 | MDR | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| katGnon315 | +inhA | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| katGnon315 | +fabD | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| katGnon315 | +furA | 1(0.53) | 1 | mono-R | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| katGnon315 | +Rv1772 | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| katGnon315 | +efpA | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| katGnon315 | +nat | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| katGnon315 | +inhA-P | +inhA | 3(1.60) | 2 | MDR | 0 | 3 | 0 | ||

| katGnon315 | +inhA-P | +Rv1592c | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| katGnon315 | +inhA-P | +Rv1772 | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| katGnon315 | +inhA-P | +ahpC-oxyR | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| katGnon315 | +inhA-P | +ahpC-oxyR | +furA | 2(1.06) | 2 | MDR, mono-R | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| katGnon315 | +ahpC-oxyR | +ahpC | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| katGnon315 | +ahpC-oxyR | +furA | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| katGnon315 | +ahpC-oxyR | +iniA | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| katGnon315 | +ahpC-oxyR | +kasA | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| katGnon315 | +ahpC-oxyR | +nat | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| katGnon315 | +ahpC-oxyR | +Rv1592c | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| katGnon315 | +ahpC-oxyR | +efpA | +fadE24 | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| inhA-P | 7(3.72) | 1 | MDR, mono-R | 3 | 3 | 1 | ||||

| inhA-P | +Rv1772 | +furA | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| inhA-P | +inhA | +ahpC-oxyR | +ahpC | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| ahpC-oxyR | 5(2.66) | 4 | MDR | 0 | 0 | 5 | ||||

| ahpC-oxyR | +iniB | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| ahpC-oxyR | +iniC | +efpA | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| ahpC-oxyR | +fbpD | +fabD | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| nat | 2(1.06) | 1 | MDR, mono-R | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||

| srmR | 1(0.53) | 1 | MDR | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Wild types | 6(3.19) | 0 | MDR | 0 | 4 | 2 | ||||

| Total | 188 | 102 | — | 20 | 101 | 67 | ||||

aCombination of multiple gene mutations present in isolates: “+” represents the simultaneous existence of mutations in each isolate

bLR, MR, and HR refer to low-level INH resistance, intermediate-level INH resistance, and high-level INH resistance, respectively

Single gene mutations

In the collection, single gene mutations were detected in five gene loci from 97 isolates. The most frequent mutations occurred in katG, and they were detected in 84.5% (82/97) of the isolates. Three types of substitutions involving amino acids at position 315 were detected in 66 (68% of 82) isolates, whereas two types of double substitutions occurred in katG. Ser315Thr was prevalent and was identified in 56 (84.8% of 66) isolates. Ser315Asn and Ser315Arg were found in nine isolates (13.6%) and one isolate (1.5%), respectively. Single Ser315Thr and Ser315Asn were observed in the median of MICs at levels of 3.2 and 12.8 mg/L, respectively.

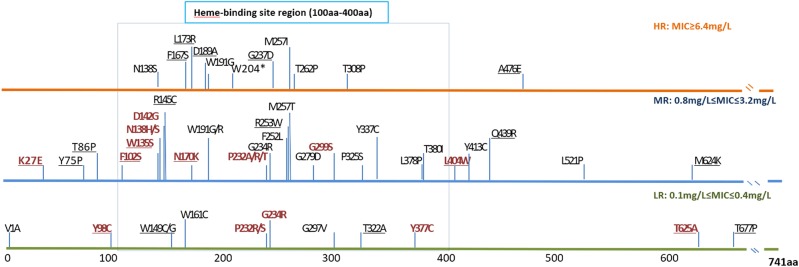

Single katG mutations at codons other than codon 315 (termed non-315 mutations) were detected in 16 isolates, which were represented by 16 mutant types in 13 amino acid positions (Fig. 1). Except for three types, all mutations occurred in the N-terminus of the KatG protein from amino acid position 27 to 299. Two types of substitutions occurred at position 138 as follows: Asp138His and Asp138Ser. At position 232, four types of substitutions (Pro232Ala/Arg/Ser/Thr) were detected in the isolates. The MIC median was 1.2 mg/L in the isolates with non-315 katG mutations. Nearly all intermediate-level resistance was related to mutations that occurred in positions prior to amino acid 299.

Fig. 1. Distribution of non-315 mutations (substitutions) in katG.

These mutations were divided into three groups based on the level of phenotypic INH resistance displayed by the isolates. The different colored lines indicate the corresponding resistance level as follows: mutations conferring low-level resistance (LR) are shown in green; mutations conferring intermediate-level resistance (MR) are shown in blue; and mutations conferring high-level resistance (HR) are shown in orange. Single gene mutations are shown in red, and combined gene mutations are shown in black. To the best of our knowledge, underlined mutations have not been previously reported

Single gene mutations were also detected in two regulator regions, namely inhA-P and ahpC-oxyR. In the inhA-P mutations, -15C-T was the predominant mutant type and was detected in all seven isolates. The median MIC value was 0.8 mg/L for -15C-T mutations. In all except one (MICs = 25.6 mg/L) of the remaining isolates, the MIC was below 1.6 mg/L. ahpC-oxyR mutations presented as four types of nucleotide substitutions (-48G-A, -51G-A, -57C-T, and -81C-T) in five isolates. The median MIC was 51.2 mg/L, and all MICs were above 12.8 mg/L in these isolates.

In addition, mutations in nat and srmR were represented by the substitution of Gly207Arg and A224V, which were separately detected in two and one isolates, respectively. A high variation of MIC results was observed in these three isolates, ranging from 0.1 to 102.4 mg/L.

Combined gene mutations

Combined gene mutations were identified in 79 (47% of 168) MDR-TB isolates and six (30% of 20) isolates with INH mono-resistance. In all but five isolates, the mutations involved a combination of katG mutations with the other 16 gene loci (Table 2).

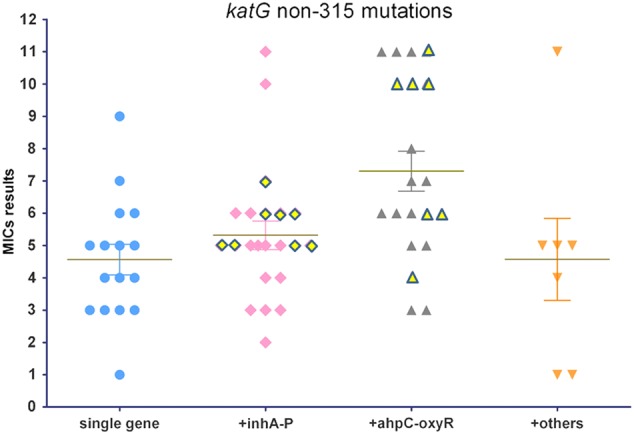

Combined 315 mutations were detected in 32% (31/97) of the isolates. Mutations involving two genes were the predominant form of combination and were identified in 80.6% (25/31) of the isolates. Mutations involving more than three gene mutations were found in the remaining six isolates. Simultaneous mutations in inhA-P were the most frequent and were detected in seven (22.6% of 31) isolates. All of these isolates exhibited a high level of resistance with MIC results above 6.4 mg/L. Among these isolates, nucleotide substitutions of -15C-T, -8T-A(C), and -34C-T were detected. These isolates also displayed greater resistance compared to the other combined gene mutations (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2. MIC results for INH-resistant isolates with katG non-315 mutations.

The horizontal axis shows four groups of isolates with single gene mutations and different combinations of multiple gene mutations. MIC results are represented by numbers from 1 to 11 on the vertical axis, corresponding to 11 double diluted concentrations of INH, ranging from 0.1 to 102.4 mg/L. The yellow diamond and triangle shapes with outskirts refer to the MIC results from isolates with three or four simultaneous gene mutations involved in the less frequent gene loci

It should be noted that mutations in efflux pump genes were simultaneously detected from the combined katG mutations. There were iniA mutations in seven isolates, and there were iniC mutations in two isolates. Four isolates with katG 315 mutations combined with iniA Gln26Arg and Arg603Lue mutations showed a high level of resistance. In addition, only 40% (6/15) of isolates displayed a high level of resistance among these combined mutations with the remaining genes.

Moreover, combined katG non-315 mutations were detected in 75.4% (49/65) of the isolates. Simultaneous mutations occurred in 12 other genes. A high frequency of mutations was detected in inhA-P and/or ahpC-oxyR in 87.8% (42/49) of the combined non-315 mutations (Fig. 2b). A combination of non-315 and inhA-P mutations was observed in 13 isolates with two gene mutations, six isolates with three gene mutations, and two isolates with four gene mutations. A combination of katG non-315 with ahpC-oxyR mutations was found in 13 isolates with two gene mutations, six isolates with three gene mutations, and three isolates with four gene mutations.

Among these combined katG non-315 mutations, the highest MIC median was detected in isolates with a simultaneous occurrence of ahpC-oxyR mutations. The MIC median was as high as 3.2 mg/L, which was higher than other types of the combined inhA-P mutations (Fig. 2) that also occurred at a high frequency. Moreover, of these combined katG non-315 mutations, the frequency of HR isolates was greater than among those with combined inhA-P mutations (39.1% [9/23] and 19.0% [4/21], respectively). In addition to mutations in these two regulator regions, simultaneous mutations in 10 other structural genes were present in the non-315 mutations.

Apart from these combined katG mutations, there were five isolates with combined gene mutations in ahpC-oxyR or inhA-P that simultaneously occurred with other genes (Table 2). Three isolates involved the combination of mutations in ahpC-oxyR with one or two other genes, such as iniB, fabD and fbpC, iniC, and efpA. One isolate exhibited a combination of mutations in inhA-P with furA and Rv1772. A combined substitution of the regulator region and structural gene of inhA-P/inhA and ahpC-oxyR/ahpC was observed, which was -15C-T/S94A/-11T-C/E189D.

Mutations simultaneously detected from pan-susceptible isolates and INH-resistant isolates

In addition to the mutations observed in the INH-resistant isolates, eight types of amino acid substitutions were simultaneously identified in both the susceptible and resistant isolates. There were seven types of substitutions detected in the collection as follows: Arg463Leu in katG; Ile322Val in Rv1592; Pro179Ala in fabD; Gly207Arg in nat; His253Tyr in kasA; Gly158Ser and Pro237Ser in fbpC; and Met323Thr in srmR.

Based on a phylogenetic analysis, three lineages of INH-resistant isolates were detected. Aside from one strain belonging to lineage 3, 145 isolates were of lineage 2, and 22 isolates were classified into lineage 4. The isolates belonging to lineage 2 contained the katG Arg463Leu substitution, which is the standard genetic marker for identifying Beijing family strains.

Discussion

The mechanism of M. tuberculosis-mediated INH resistance is highly complex due to the involvement of several genes. The present study focused on illustrating the relationship between various kinds of combined mutations and the associated phenotypic resistance. Using a WGS platform, mutations in these genes were simultaneously detected for each isolate in the collection. These results provided an opportunity to discover the influence of these gene mutations on the development of INH resistance in MDR-TB isolates.

Previous published data have demonstrated that katG 315 mutations, especially Ser315Thr, are the main cause of INH resistance, exhibiting a frequency ranging from 42% to over 90% in different regions throughout the world18. Currently, katG 315 mutations and mutations in inhA structural and promoter regions are used as markers for the rapid detection of INH resistance. Commercial kits (e.g., Geno Type MTBDR Plus Assay and the Nipro NTM + MDRTB Detection Kit 2) have been recommended by the World Health Organization for the diagnosis of INH resistance in clinical isolates (WHO, 2016). In the present collection, there was a predominance of katG mutations, which were detected in 86.2% of the INH-resistant isolates, far higher than that of other genes. In comparison, a substitution of Ser315Thr was only identified in 41.0% (69/168) of the MDR-TB isolates and 65% (13/20) of the INH mono-resistant isolates. This finding indicated that the more complex INH-resistance mutations occurred in MDR-TB isolates. Indeed, a high diversity of katG mutations was exhibited by both types of deletions and 53 amino acid substitutions. These mutations were represented as 90 types of mutations, including 21 different single gene mutations and 69 combined gene mutations (Table 2). Except for two genes, nearly all INH resistance-related genes occurred in combination with katG mutations.

The prevalence of 315 mutants may be due to the loss of oxidase activities but retainment of the catalase-peroxidase activities of katG. Moreover, because this modification confers a survival advantage, it is readily spread throughout the population21,22. The present study showed that isolates with single 315 mutations displayed intermediate levels of resistance (median MIC = 3.2 mg/L). In addition, isolates with combined 315 mutations exhibited a higher MIC median, and HR isolates occurred with a higher frequency than those with single 315 mutations.

The accumulation of other gene mutations increased the resistance to INH among these MDR-TB isolates. It should be noted that inhA-P and efflux pump encoding gene (iniA) mutations were responsible for this development of drug resistance. Within these MDR-TB strains, INH resistance has been found to be associated with the overexpression of InhA, which is caused by mutant inhA-P23. As a putative target for INH and ethionamide, overexpression of the NADH-specific enoyl-ACP reductase may result in more active INH24. A previous study has also shown a selective advantage for strains harboring inhA-P mutations to become XDR-TB strains using the current treatment regimen25. Moreover, Ser315Thr has also been reported to be associated with an unfavorable treatment outcome, and inhA-P increases the risk of relapse26. Thus, the detection of this type of mutation combination in MDR-TB isolates indicates how high-level resistance emerges and supports the more cautious usage of anti-TB drugs for treatment.

Recent studies have also shown that katG non-315 substitutions are a frequent occurrence among INH-resistant isolates27,28. In the present collection, several non-315 mutations were detected among the MDR-TB isolates. Of these mutations, 23 have not been previously reported (Fig. 1). Moreover, these non-315 mutations occurred throughout the entire katG gene. The non-315 mutations located in the N-terminus of the KatG protein typically exhibited intermediate or high resistance. These findings suggested that this region is critical for INH activity, and various degrees of reduction in catalase activity are also associated with INH resistance29.

Compared to the majority of single genes involved in katG 315 mutations, non-315 mutations commonly occurred with further accumulation of other gene mutations. More than two-thirds of isolates with non-315 mutations simultaneously harbored other gene mutations. Two gene loci consisted of inhA-P and ahpC-oxyR, which were frequently identified in these isolates. Using line probe assays, the positive detection of only inhA-P mutations represented low-level resistance. These results also demonstrated that single inhA-P mutations were related to low-level resistance. However, the frequency of intermediate-level resistance increased substantially in isolates with non-315 mutations combined with inhA-P mutations (from 42.9% [3/7] to 68.4% [13/19]).

A previous study has demonstrated that mutations in ahpC-oxyR are compensatory alterations that occur due to a loss in catalase-peroxidase activity30. Mutations in ahpC-oxyR occur at a low frequency due to limited data obtained from previous detections18. In the present study, a substantial number of MDR-TB isolates harbored mutations in this regulator region, and the majority of which displayed a high level of resistance with MIC results over 6.4 mg/L. Among these isolates, ahpC-oxyR mutations were located in the region from −48 to −54. In contrast, combined non-315 mutations were located in the heme-binding site region, which is the active site structure for catalase-peroxidase function31. If there was a compensatory effect produced by ahpC-oxyR mutations, a high level of resistance would be associated with these non-315 amino acid substitutions. These findings revealed that these amino acids are likely key positions in katG because these mutations are associated with a greater loss of KatG function and require overexpression of ahpC for mycobacteria to resist the pressure of high INH concentrations. In addition, the occurrence of ahpC-oxyR is associated with relapse or treatment failure. Moreover, a higher frequency of ahpC-oxyR mutations was present in isolates from retreated MDR-TB patients compared to isolates from new cases (33.0% [34/103] vs. 17.6% [15/85]; P < 0.05). One notable phenomenon in the present study was that inhA-P or ahpC-oxyR mutations occurred in all non-315 mutations combined with three or four gene mutations, and these isolates typically displayed relatively high MICs (Fig. 2). This finding indicated that these less frequent gene mutations occur as a subsequent accumulation during the development of INH resistance among these isolates.

Genotyping demonstrated that katG 315 mutations frequently occurred in isolates belonging to lineage 2, also known as the Beijing family. Moreover, the majority of combined 315 mutations belonged to sublineage 2.3, which are prevalent strains in China32. However, katG non-315 mutations were also found in isolates belonging to other lineages, such as Lineage 3 and 4. The high degree of polymorphisms among non-315 mutations reflected the development of drug resistance resulting from the accumulation of mutations in multiple gene loci under a selection pressure. This process may be strongly associated with the failure or relapse of TB treatment.

The present study determined the mutation profile of INH resistance-related gene mutations in MDR-TB and mono-resistant isolates. Although several gene loci are involved in INH resistance, isolates exhibiting high-level resistance were typically associated with the accumulation of katG mutations combined with inhA-P and ahpC-oxyR mutations. In addition to 315 mutations, combined katG non-315 and ahpC-oxyR mutations also revealed a close relationship with a high level of resistance in MDR-TB isolates. However, this group of mutations could not be detected with a commercial kit for the diagnosis of INH resistance. Such mutations have not been of great concern in previous studies due to limited data regarding the occurrence in clinical isolates. Moreover, the remaining gene mutations occurred occasionally and usually as a component of combined mutations in MDR-TB isolates. These findings expanded the understanding of the development of INH resistance by M. tuberculosis in TB patients.

Materials and methods

Clinical isolates

To acquire a high diversity of mutant types with gene mutations associated with INH resistance, M. tuberculosis isolates from a national survey of drug resistance recently conducted in China were selected for analysis. A collection of 201 isolates was randomly obtained from the Chinese national survey of the prevalence of drug-resistant TB conducted in 2007, which included 168 MDR-TB isolates, 20 INH mono-resistant isolates, and 13 pan-susceptible isolates. These isolates were obtained from TB patients in 72 representative regions. Thus, high polymorphism of INH resistance-related mutations was represented in these isolates.

Single clones for each isolate were cultured on Löwenstein–Jensen medium33. Original cultures were collected, and 10-fold serial dilutions were prepared. These dilutions were then cultured and harvested to extract genomic DNA. The present study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Institute of Pathogen Biology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College.

Drug susceptibility testing and determination of MDR and INH mono-resistant strains

The drug resistance profile of each isolate was determined using the absolute concentration method on Löwenstein–Jensen medium19. Six key anti-tuberculosis drugs (isoniazid, 0.2 mg/L; streptomycin, 4 mg/L; rifampicin, 40 mg/L; ethambutol, 2 mg/L; ofloxacin, 2 mg/L; and kanamycin, 40 mg/L) from Sigma Aldrich were selected for drug susceptibility testing using concentrations based on the WHO guidelines. MDR strains were those determined to exhibit resistance to both INH and rifampicin. Mono-INH-resistant isolates were defined as those resistant only to INH and susceptible to the other five drugs. Pan-susceptible isolates were susceptible to all six drugs. Further phenotypic confirmation of each type of isolate was performed using the BACTEC MGIT 960 System (BD Diagnostic Systems).

Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was performed in 96-well microplates using the colorimetric method34. Isolates were treated with 10 INH concentrations, ranging from 0.05 to 102.4 mg/L, which were prepared by two-fold dilution in 7H9 broth. MIC results were read as the lowest concentration of INH that prevented a color change for each isolate.

The isolates were divided into four groups according to the degree of INH resistance as follows: 1) susceptible (MIC < 0.01 mg/L); 2) low-level resistance (LR; 0.1 mg/L ≤ MIC ≤ 0.4 mg/L); 3) intermediate-level resistance (MR; 0.8 mg/L ≤ MIC ≤ 3.2 mg/L); and 4) high-level resistance (HR; MIC ≥ 6.4 mg/L).

Identification of INH resistance-related mutations using next-generation sequencing

Genomic DNA from each isolate was extracted using a Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Co., Madison, USA). Sequencing libraries were constructed and sequenced with a Truseq ® Nano DNA kit (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Quality assessment of the sequencing data was performed using the NGS QC Toolkit with a cutoff of Q20, and a minimum read length of 101 base pairs was used for subsequent mapping. Valid reads were mapped to the reference genome sequence of M. tuberculosis H37Rv (GenBank accession NC_000962) using the Burrows–Wheeler algorithm as implemented in the BWA software package35. For all isolates, the reference genome coverage was >99% with a minimum depth of 10× and a consensus quality score of 50 using SAMtools. Mutations in each INH resistance-related gene were identified by aligning the corresponding reads with the reference sequence (M. tuberculosis H37Rv). Sequencing reads have been submitted to the NCBI sequence read archive (SRA) under accession PRJNA268900.

Statistical analysis

The Chi-squared test or Mann–Whitney U-test was used when appropriate to assess the relationship between the mutations and MICs. Significance was considered when P < 0.05. SPSS statistical software package was used for all statistical analyses.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the National Major Science and Technology Project for the Prevention and Treatment of AIDS and Viral Hepatitis and Other Major Infectious Diseases (2017ZX10201301-002-002) and CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (2016-I2M-1-013). The present study was also supported by the Non-Profit Central Research Institute Fund of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (2017PT31010) and Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (GCZX2015043015340574).

Author contributions

Q. Jin, X. Zhang and Y. Zhao are co-senior authors and designed the research. L. Liu, F. Jiang, L.Chen, and B. Zhao performed extensive research and contributed equally to this work. B. Liu and J.Yang contributed to the data analysis. J. Dong, L. Sun, and Y. Zhu performed the next-generation sequencing. Y. Zhou performed the bacterial culture and drug susceptibility testing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Liguo Liu, Fengting Jiang, Lihong Chen, Bing Zhao

These authors contributed equally and are co-senior authors: Yanlin Zhao, Qi Jin, Xiaobing Zhang.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. in WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee (WHO, Geneva, 2015).

- 2.Gegia M, Winters N, Benedetti A, van Soolingen D, Menzies D. Treatment of isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis with first-line drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017;17:223–234. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30407-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heym B, Zhang Y, Poulet S, Young D, Cole ST. Characterization of the katG gene encoding a catalase-peroxidase required for the isoniazid susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:4255–4259. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.13.4255-4259.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y, Heym B, Allen B, Young D, Cole S. The catalase-peroxidase gene and isoniazid resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nature. 1992;358:591–593. doi: 10.1038/358591a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unissa AN, Subbian S, Hanna LE, Selvakumar N. Overview on mechanisms of isoniazid action and resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016;45:474–492. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sreevatsan S, Pan X, Zhang Y, Deretic V, Musser JM. Analysis of the oxyR-ahpC region in isoniazid-resistant and -susceptible Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex organisms recovered from diseased humans and animals in diverse localities. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997;41:600–606. doi: 10.1128/AAC.41.3.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banerjee A, et al. inhA, a gene encoding a target for isoniazid and ethionamide in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 1994;263:227–230. doi: 10.1126/science.8284673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramaswamy SV, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in genes associated with isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003;47:1241–1250. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.4.1241-1250.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee AS, Lim IH, Tang LL, Telenti A, Wong SY. Contribution of kasA analysis to detection of isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Singapore. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2087–2089. doi: 10.1128/AAC.43.8.2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zahrt TC, Song J, Siple J, Deretic V. Mycobacterial FurA is a negative regulator of catalase-peroxidase gene katG. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;39:1174–1185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2001.02321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colangeli R, et al. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis iniA gene is essential for activity of an efflux pump that confers drug tolerance to both isoniazid and ethambutol. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;55:1829–1840. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumari R, Saxena R, Tiwari S, Tripathi DK, Srivastava KK. Rv3080c regulates the rate of inhibition of mycobacteria by isoniazid through FabD. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2013;374:149–155. doi: 10.1007/s11010-012-1514-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Unissa AN, et al. Variants of katG, inhA and nat genes are not associated with mutations in efflux pump genes (mmpL3 and mmpL7) in isoniazid-resistant clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from India. Tuberculosis. 2017;107:144–148. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2017.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson M, et al. Exploring drug-induced alterations in gene expression in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by microarray hybridization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:12833–12838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee AS, Teo AS, Wong SY. Novel mutations in ndh in isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001;45:2157–2159. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.7.2157-2159.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Upton AM, et al. Arylamine N-acetyltransferase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a polymorphic enzyme and a site of isoniazid metabolism. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;42:309–317. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geistlich M, Losick R, Turner JR, Rao RN. Characterization of a novel regulatory gene governing the expression of a polyketide synthase gene in Streptomyces ambofaciens. Mol. Microbiol. 1992;6:2019–2029. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seifert M, Catanzaro D, Catanzaro A, Rodwell TC. Genetic mutations associated with isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119628. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao Y, et al. National survey of drug-resistant tuberculosis in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:2161–2170. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hazbon MH, et al. Population genetics study of isoniazid resistance mutations and evolution of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006;50:2640–2649. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00112-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borrell S, Gagneux S. Infectiousness, reproductive fitness and evolution of drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung. Dis. 2009;13:1456–1466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen T, Sommers B, Murray M. The effect of drug resistance on the fitness of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2003;3:13–21. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00483-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larsen MH, et al. Overexpression of inhA, but not kasA, confers resistance to isoniazid and ethionamide in Mycobacterium smegmatis, M. bovis BCG and M. tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;46:453–466. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morlock GP, Metchock B, Sikes D, Crawford JT, Cooksey R. C. ethA, inhA, and katG loci of ethionamide-resistant clinical Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3799–3805. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.12.3799-3805.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muller B, et al. inhA promoter mutations: a gateway to extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in South Africa? Int. J. Tuberc. Lung. Dis. 2011;15:344–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huyen MN, et al. Epidemiology of isoniazid resistance mutations and their effect on tuberculosis treatment outcomes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013;57:3620–3627. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00077-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torres JN, et al. Novel katG mutations causing isoniazid resistance in clinical M. tuberculosis isolates. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2015;4:e42. doi: 10.1038/emi.2015.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abe C, et al. Biological and molecular characteristics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates with low-level resistance to isoniazid in Japan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008;46:2263–2268. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00561-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brossier F, Boudinet M, Jarlier V, Petrella S, Sougakoff W. Comparative study of enzymatic activities of new KatG mutants from low- and high-level isoniazid-resistant clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis. 2016;100:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sherman DR, et al. Compensatory ahpC gene expression in isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 1996;272:1641–1643. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Powers Linda, Hillar Alex, Loewen Peter C. Active site structure of the catalase-peroxidases from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Escherichia coli by extended X-ray absorption fine structure analysis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology. 2001;1546(1):44–54. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4838(00)00221-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hicks ND, et al. Clinically prevalent mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis alter propionate metabolism and mediate multidrug tolerance. Nat. Microbiol. 2018;3:1032–1042. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0218-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anargyros P, Astill DS, Lim IS. Comparison of improved BACTEC and Lowenstein-Jensen media for culture of mycobacteria from clinical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1990;28:1288–1291. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.6.1288-1291.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yajko DM, et al. Colorimetric method for determining MICs of antimicrobial agents for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1995;33:2324–2327. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2324-2327.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]