Abstract

Bismuth has long been a prototypical system for investigating phase transformations and melting at high pressure. Despite decades of experimental study, however, the lattice-level response of Bi to rapid (shock) compression and the relationship between structures occurring dynamically and those observed during slow (static) compression, are still not clearly understood. We have determined the structural response of shock-compressed Bi to 68 GPa using femtosecond X-ray diffraction, thereby revealing the phase transition sequence and equation-of-state in unprecedented detail for the first time. We show that shocked-Bi exhibits a marked departure from equilibrium behavior - the incommensurate Bi-III phase is not observed, but rather a new metastable phase, and the Bi-V phase is formed at significantly lower pressures compared to static compression studies. We also directly measure structural changes in a shocked liquid for the first time. These observations reveal new behaviour in the solid and liquid phases of a shocked material and give important insights into the validity of comparing static and dynamic datasets.

Introduction

When compressed and heated, materials frequently undergo phase transitions associated with atomic structural changes to denser crystalline or amorphous (e.g. liquid) forms. Such high-pressure transformations, and the properties of the high-pressure phases, can be studied using X-ray diffraction on statically-compressed samples1,2, and, more recently, using rapid, or dynamic, compression coupled to powerful X-ray sources3–6. The rapid timescale of dynamic compression has led to questions about the kinetics of structural change - and whether dynamically-produced states are at thermodynamic equilibrium. Establishing the kinetics of phase transformations3,4,6, particularly those to the high-pressure phases encountered in dynamic compression5–7, is essential for a range of natural and technical applications from the study of meteor impact to the performance of alloys under high strain rates. Using an XFEL source, we have determined the lattice-level response of a shocked material as it undergoes multiple structural changes in both the solid and liquid phases, revealing a wealth of new behaviour.

Bismuth, together with iron, is an archetypal metallic phase-transforming material whose study has deepened our understanding on how materials respond to extreme compression8. Static compression studies at 300 K have revealed three structural transitions at 2.5, 2.8 GPa and 7.7 GPa1 with several complex structures forming, most notably the incommensurate structure of Bi-III (stable between 2.8–7.7 GPa in static compression studies). Despite Bi having also been studied extensively using shock compression9–12, its behavior under rapid pressure loading remains insufficiently understood. Phase transformations have been reported in shocked-Bi at 2.7 GPa9, 3.2 GPa13 and 7.0 GPa11, in reasonable agreement with the static solid-solid transition pressures if the raised temperatures attained in shock compression are accounted for. As traditional shock experiments provide no structural information, the identities of theses phases could only be assumed to be the same as the static phases, implying the transformations occur at, or close to, thermodynamic equilibrium. However, the densities of the high-pressure phases observed in the shock experiments are at considerable odds with those obtained in the static compression studies, with discrepancies as large as 5% at only ~5 GPa, and gradual density changes are seen11, suggestive of mixed-phase regions. As a result, it is not at all clear whether the complex structures observed in static compression studies on the timescales of seconds or minutes, such as incommensurate Bi-III, are the same as those that form in nanoseconds or microseconds under shock compression. Direct structural information on shocked-Bi has been limited, with low-fluence X-ray probes leading to only tentative phase assignments that largely adhere to the existing interpretation of equilibrium phase diagram12.

Similarly, while the melting behavior of Bi upon dynamic loading and unloading has been the subject of numerous theoretical and experimental studies14–16, nothing is known about the structure of the liquid at the very high-pressure conditions (>8 GPa) where melting is predicted to occur under shock compression. Given the number of solid-state phase transformations, and known liquid structural changes at lower pressure17,18, there is a pressing need to establish liquid structural properties at higher pressures such as above the shock melting point. While the presence of shocked liquid-Bi on release near 5 GPa was recently observed for the first time at an XFEL4, the limited angular range of the X-ray data precluded quantitative analysis of the liquid structure similar to that developed in static experiments19. However, the improved data quality and extended angular range that have since become available5 now allow for structural studies of shocked liquids for the first time.

Results

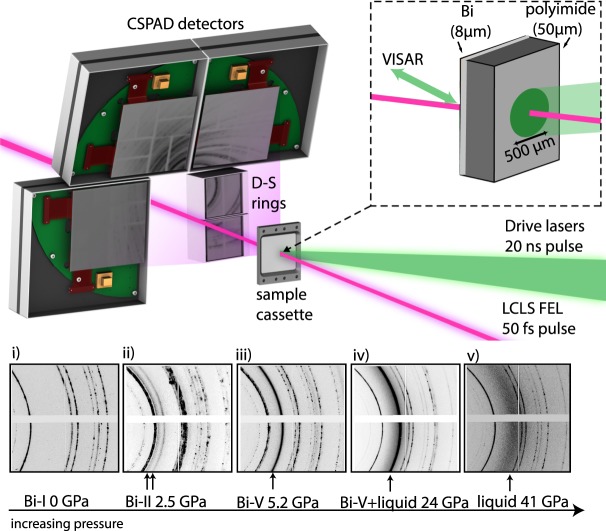

All experiments were carried out at the Matter at Extreme Conditions (MEC) end station of the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) XFEL. The experimental set up is shown in Fig. 1. Polycrystalline Bi samples of 8 μm thickness were compressed using a Nd:glass drive laser, and the XFEL X-ray pulse was timed to probe the sample when the majority of it was in the peak compressed state. The VISAR (velocity interferometer system for any reflector) diagnostic measured the sample rear surface velocity history [see methods].

Figure 1.

Experimental Setup and 2D diffraction data. (a) CSPAD detectors were arranged in a transmission Debye-Scherrer geometry in the MEC vacuum chamber. Dual drive beams were incident on target at angle of 15° and the XFEL beam probed the target at 30° from the target normal. The VISAR laser probed normal to the rear surface of the target. (b) 2D raw diffraction images from three different solid phases of Bi obtained on compression (profiles (i–iii)) and the liquid phase (profiles (iv,v)). The initial microstructure of the Bi starting material is retained as the Bi-I phase is compressed, but it drastically changed through the reconstructive phase transitions (profiles (ii,iii)). The strongest diffraction peaks from the high-pressure phase are indicated with arrows. Diffraction peaks from uncompressed Bi-I were observed in all diffraction profiles obtained before the shock reached the target rear surface.

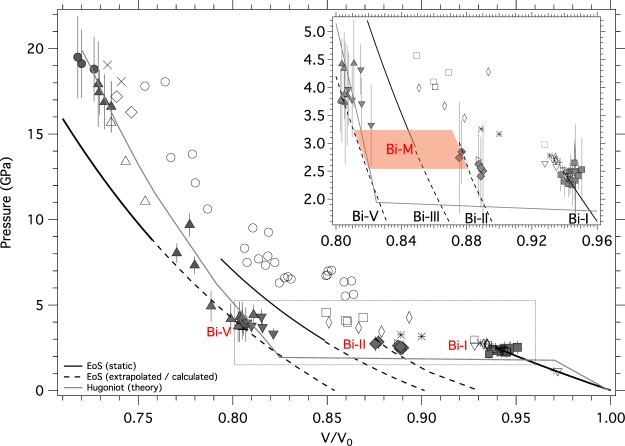

Bi is observed to exist in 4 different solid phases on shock compression up to 17 GPa (Fig. 2a), above which the liquid phase emerges (Fig. 2b). Diffraction from the compressed Bi-I phase (space group , Z = 2) is always observed on shock compression at relatively low pressures (<9 GPa) as a result of the splitting of the shock front as Bi-I transforms to denser phases (Fig. 2a(ii)). The first solid-solid transformation is determined to occur at 2.5 GPa (Fig. 2a(ii)) and the Bragg reflections from the new phase fit very well to the structure of Bi-II (space group C2/m, Z = 4), with refined lattice parameters in excellent agreement with previous diamond anvil cell (DAC) studies of Bi-II at the same pressure1 (See Fig. S3).

Figure 2.

Solid phases + liquid phase (L) of Bi on shock compression. (a) Bi-I (profile (i)) transforms to Bi-II (profile (ii)) at 2.5 GPa (upper tick marks) with compressed Bi-I also being observed (lower tick marks). A transformation to a metastable phase (Bi-M, and whose peaks are marked with asterisks) is observed at 3 GPa (profile (iii)) and is always accompanied by diffraction peaks from bcc Bi-V, the locations of which are indicated by tick marks. Above 4 GPa only peaks from Bi-V are observed (profiles (iv,v)). (b) The first liquid scattering appears at 19 GPa (profile (ii)). The liquid phase-fraction grows with increasing pressure (profiles (iii,iv)) until only diffraction from the liquid phase is observed above 27 GPa (profile (v)). Peaks from uncompressed Bi-I, the locations of which are shown using triangles below profile (a)(i), are observed at all pressures.

However, a marked departure from equilibrium behavior is observed between 3–4 GPa as another phase transformation occurs (Fig. 2a(iii)), giving rise to a new set of Bragg reflections which cannot be fitted with the incommensurate Bi-III structure (stable between 2.8 and 7.7 GPa at 300 K in static compression studies). Several of the new Bragg reflections can be fitted to the body-centered cubic Bi-V phase (identified by tick marks in Fig. 2a(iii)) but there remain four additional reflections (highlighted with asterisks in Fig. 2a(iii)), which are observed reproducibly over a pressure region of 3–4 GPa which cannot be fitted to any equilibrium phase of Bi, including the high-temperature Bi-IV phase (see discussion in Supplementary Materials and Fig. S4). Thus, a metastable phase has formed. Definitive resolution of the structure of this new phase - termed Bi-M - is difficult due to the extensive peak overlap present in the 4-phase (ambient Bi-I, compressed Bi-I, Bi-M, Bi-V) profile of Fig. 2a(iii).

The Bragg reflections from the metastable phase disappear above 4 GPa, and thereafter the Bi-V phase is observed up to 17 GPa (Fig. 2b(i)). At 19 GPa, diffuse, textureless diffraction emerges together with diffraction from the Bi-V phase (Fig. 2b(ii)) - the Bi sample starts to melt. The liquid phase fraction grows as the pressure increases further (Fig. 2b(iii)), until, at 27 GPa (Fig. 2b(iv)), only a very small fraction of the Bi-V phase is observed. This pressure range over which solid-liquid coexistence occurs under shock compression, is in excellent agreement with the 18–27 GPa pressure range calculated by Pellisier et al.14.

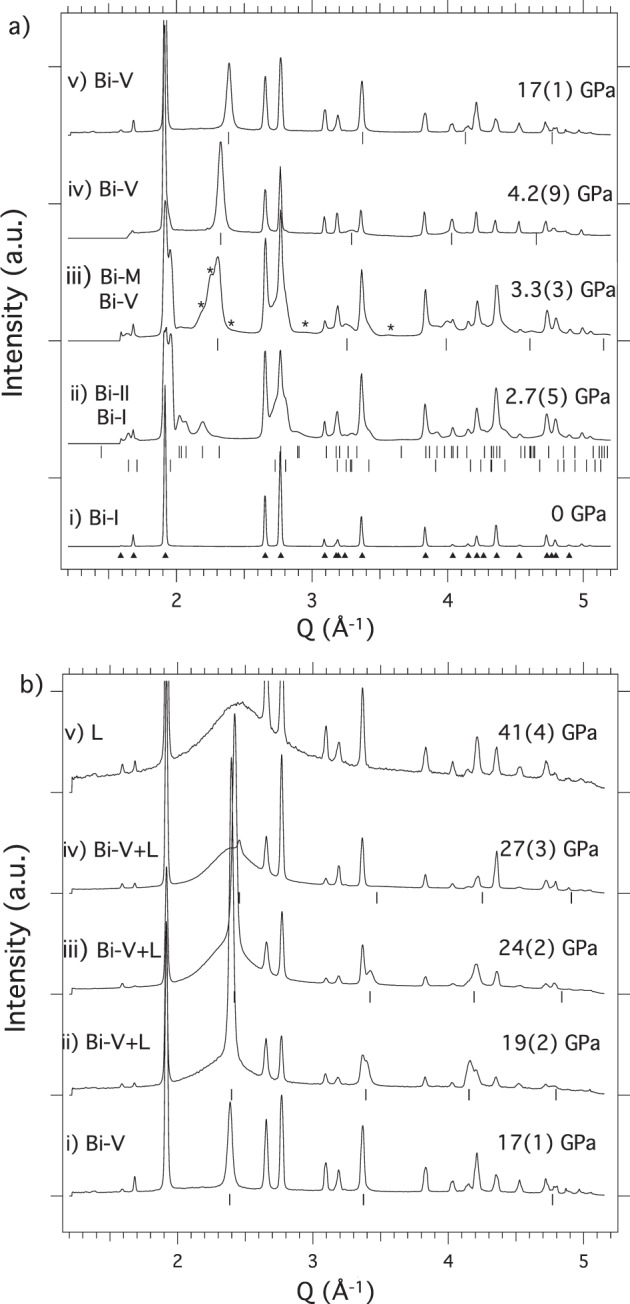

At higher pressures, only liquid diffraction is observed (Fig. 3a). Three maxima in the liquid diffraction profiles are observed, all of which shift to higher-Q with pressure (compare Fig. 3a(i) with Fig. 3a(v)). The atomic structure factor S(Q) = 1 + 4, where ρ0 is the average atomic density, is obtained by scaling the diffracted intensity by the atomic scattering factor20 and normalising it to 1 at the largest experimental Q value (Q = ) (Fig. 3b(i–v)).

Figure 3.

Local Structure of Liquid-Bi on Shock Compression (profiles spaced in intensity for clarity). (a) Integrated diffraction profiles from liquid-Bi from 28–68 GPa (profiles (ii–vi)), and also at 0 GPa and ~1500 K (profile (i)). (b) The corresponding S(Q) data. The prominent shoulder on the high-Q side of the first liquid peak at 0 GPa suggest that the local structure of liquid-Bi at this pressure deviates from that of a simple liquid. At higher pressures (profiles (ii–vi)) this shoulder is not observed, demonstrating that liquid-Bi is more simple and close-packed at these pressures. (c) The corresponding g(r) data. The form of g(r) changes as a shoulder on the left-hand side of the second coordination maximum becomes more prominent with increasing pressure, indicating liquid-Bi goes through a subtle and smooth transition with pressure. The full and dotted profiles in (b,c) show the S(q) and g(r) results obtained using sample densities determined using two different methods. The ambient pressure S(q) and g(r) from Greenberg et al. are shown by dashed line in (b)(i) and (c)(i) for comparison23.

The ratio of the location of the first (Q1) and second (Q2) liquid maxima in the structure factor (S(Q)) can indicate the structural complexity of a liquid21. A close-packed liquid of hard spheres has symmetric peaks and a Q2/Q1 ~ 1.8 with this value increasing with structural asymmetry. Structural changes in the liquid state are most evident in the pair distribution function (g(r)), from which the coordination number (, where rmin is the location of the first minimum in g(r)) can be extracted. By adapting a Fourier analysis procedure developed by Eggert et al.19 we can also determine the density of liquid-Bi from the diffraction data alone. The accuracy of these values can be assessed by comparing with densities determined from the VISAR diagnostic. Pair distribution functions were generated by both allowing the density parameter to vary (red dotted lines in Fig. 3c) and fixing to the measured VISAR value (black lines in Fig. 3c). The agreement between the two functions in each case is very good.

By probing a Bi sample after it had completely released from peak pressure, we were also able to study the structure of liquid Bi at ambient pressure and ~1500 K. Our results show that the Q2/Q1 ratio of ~2 (Fig. 3b(i)), the form of the g(r) (Fig. 3c(i)), and the obtained CN of ~8 (Fig. S5) at these conditions all reproduce ambient-pressure data from previous static studies22,23. This value of coordination shows that liquid-Bi exists in an open, complex arrangement mirroring the complexity of the underlying solid phases at these conditions. The CN increases to ~12 by 28 GPa and the Q2/Q1 ratio decreases to ~1.8, where both remain constant thereafter up to 68 GPa (Fig. S5) demonstrating that liquid-Bi adopts a more close-packed structure at high-pressure, also matching results from static experiments17,24. However, inspection of the form of the g(r) between 35–63 GPa reveals an asymmetry in the second coordination shell emerging at ~4.5 Å indicating that the molten Bi has undergone a change in local structure (profiles (iv), (v), and (vi) of Fig. 3c). This feature in the g(r) is found not to be an artifact of the analysis procedure as it is observed whether the sample density is set as a refineable parameter in the g(r) determination, or whether the density is fixed at the value determined by VISAR. This structural change is observed through the shortening and splitting of the second coordination shell, from 5.70 Å in the low-pressure melts (i.e. 28–35 GPa) to 5.55 Å with a shoulder on the low-r side ~4.5 Å in the high-pressure melts (i.e. 62–68 GPa). Such a structural change transition is analogous to a transition from a close-packed/hard sphere liquid to a more complex structured liquid and could indicate an underlying, high-temperature phase transition in the solid phase. Our results in density are in agreement with the values determined by the VISAR diagnostic to better the 10% at the highest pressures. These uncertainties would be considerably reduced with the use of a higher-energy X-ray source (See Supp. Mat. for discussion of the liquid density analysis).

Discussion

The shock compression behavior of Bi observed via X-ray diffraction differs from that reported from previous studies both in terms of the phases observed and conditions achieved. Rather than the smooth increase in density determined previously from changes in the observed shock wave profile, our ability to resolve distinct phases as a function of pressure reveals that Bi compresses through a sequence of first-order transitions closely resembling that seen in previous DAC data. The large discrepancies between our compression data and those of previous shock studies in the pressure range of 2.5–10 GPa are likely due to the difficulty in determining the sample densities accurately from shock wave-profile analyses due to the complications with dealing with multiple propagating waves in transforming materials25. By determining the structure of the high-pressure phases formed in Bi under shock compression, we can measure the density of these high-pressures phases in unprecedented detail overcoming the challenges faced by traditional shock experiments.

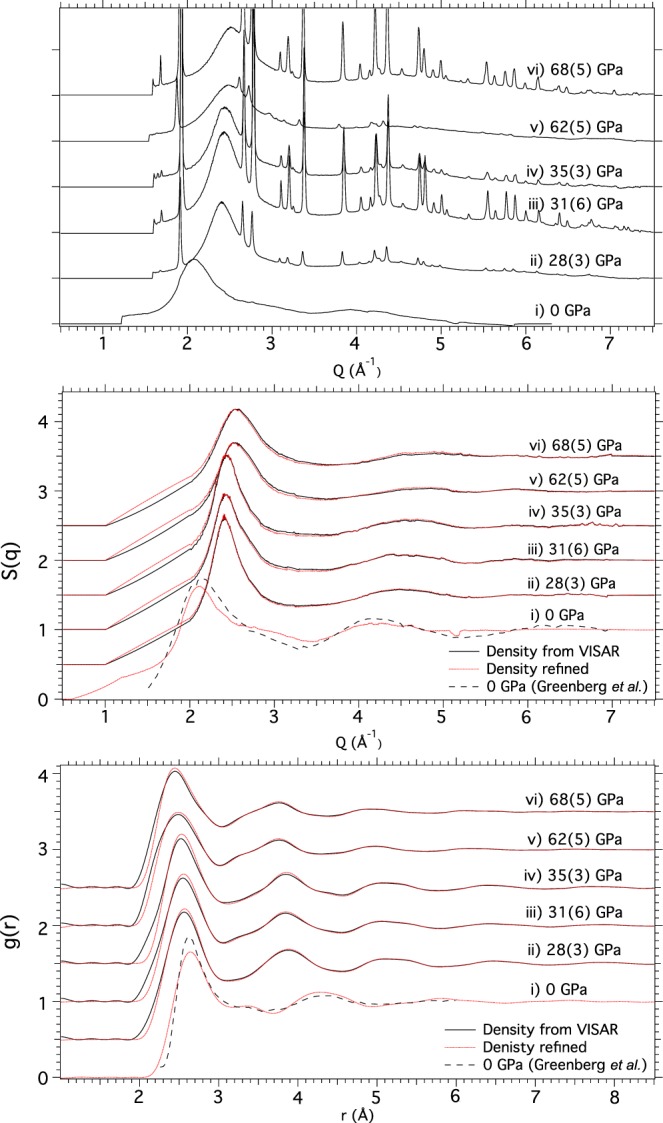

We observe Bi-V at conditions where it was previously thought to be elastically unstable under dynamic compression16. The measured lattice parameter of the Bi-V phase at these low pressures is typically a = 3.87 Å (V/V0 = 0.82), entirely consistent with that estimated by extrapolating the room-temperature static compression data for Bi-V down to this pressure26 (Fig. 4). The Bi-V phase has been observed in static compression experiments at 4 GPa and 550 K22 and so the observation of Bi-V in our experiments at unexpectedly low pressures might result from the sample being heated to elevated temperatures during shock compression. However, several studies which have predicted the pressure-temperature path of Bi under shock compression, and have shown that the heating of the sample during shock compression is negligible, largely due to a significant temperature decrease during the Bi-I-II transition10,27 associated with latent heat. Shock-induced heating to 550 K at 4 GPa, only 50 K below the melting temperature, would also result in melting at only slightly higher pressures, rather than at 19 GPa as observed here. Observing Bi-V at lower pressures is in stark contrast with standard models and observations for high-pressure phase transitions under dynamic loading, in which transition pressures are often elevated (over-driven) due to rate-limited ‘kinetic hindrance’28,29. The under pressurisation of Bi-V may instead be due to kinetic hindrance of the preceding phase (Bi-III), which causes the next-most stable phase to appear. In other words, the energy landscape of Bi under dynamic compression is, on the nanosecond timescale of the present experiment, distinct from the equilibrium landscape. Such an assertion is supported by a recent study on shock compressed Si which demonstrated how dynamic compression can access transformation pathways not observed in near equilibrium static compression studies30. However, Bi-III has been observed under dynamic compression in the dynamic DAC at compression rates of 102 GPa/s31, 7 orders of magnitude slower than the strain rates achieved in our experiments. A transition in the energy landscape may thus lie somewhere between nanosecond and millisecond timescales, a regime which might be accessible by gun-impact. Bi-M, then, is the next-most stable phase of Bi in a small pressure range, and/or a structural intermediary/precursor to Bi-III, on nanosecond timescales.

Figure 4.

Multiphase Hugoniot of Bi. Compressibility data obtained in the current study are plotted using grey shaded symbols, and their phase is identified with red type. The peak sample pressure was determined using the UFS as measured by VISAR and the volumetric compression was determined by diffraction (see pressure determination). The shaded lozenge in the inset indicates the region of P − V space to which our data constrain the metastable Bi-M phase. Data from Bi-V which were obtained from diffraction profiles containing diffraction peaks from both Bi-V and Bi-M are indicated with shaded inverted triangles. Previous shock compression data (including the data of Romain et al. (grey open circles)11) are shown by open symbols (triangles15, inverted triangles (36, squares (8, diamonds9, plus signs37, crosses38, and asterisks (reanalysed from36). The room temperature EoSs obtained from static-compression studies (labelled in the inset) are shown with solid black lines, and their extrapolation to ambient pressure with dashed lines. The EoS for Bi-II is taken from the computational study of Hausserman et al.39. The theoretical Hugoniot of Pelissier et al.14 (solid grey line) shows excellent agreement with our data throughout the entire pressure range studied. For tabular data see Table S1.

The absence of the incommensurate host-guest structure of Bi-III is unexpected, especially since a very similar structure has been observed in shock-compressed Sc5. The formation of composite, intermediate structures (as observed in the group-V metals) has been reported to result from structural frustration between competing structural processes in the Bi-I to bcc Bi-V transition path32. The combination of high pressurisation rates (109 GPa/s) and significant shear forces associated with shock compression may be key in relieving this frustration, allowing the higher-symmetry Bi-V phase to form at only ~3 GPa. This result has implications for the many other phase transforming systems which form complex intermediate structures before transforming to a higher symmetry cubic phase such as As, Sb, Sn and Te.

In the liquid phase, group V elements have been shown to undergo structural changes, the most dramatic of which occurs in liquid-P which undergoes a first-order liquid-liquid phase transition at 1 GPa and 1300 K33. The structure of liquid-As has been shown to reflect the structural changes of the solid (A7 to simple cubic) with an increase in coordination number of 3 to 6 with pressure34. Our results (CN increasing from 8 to 12 with pressure) are analogous to the results of As, demonstrating that liquid-Bi too becomes more close-packed with pressure, consistent with the results of Yaoita et al.24. Observing subtle changes in liquid structure between 35–63 GPa demonstrates the high-quality data now achievable by coupling XFEL sources to high-power laser systems. Studying liquid structures using dynamic compression overcomes a major difficulty faced in static compression experiments as the large X-ray background generated by Compton scattering from the diamond anvils is eliminated, greatly reducing the experimental background level19.

By combining velocimetry measurements with high-quality diffraction from the LCLS, we have determined the multiphase behavior of Bi under shock compression to 68 GPa. Bi is observed to exhibit a marked departure from equilibrium behaviour, highlighting the inadequacy of relying on the static phase diagram to interpret dynamic compression results in phase transforming materials. The formation of the cubic Bi-V phase at 3 GPa in place of the complex Bi-III structure suggests that in nanosecond compression experiments the rich structural complexity exhibited by many phase-transforming elements may be significantly reduced or inhibited. We also resolved several gradual structural and density changes in the liquid phase of Bi with pressure which heralds the possibility of quantitatively studying liquid-liquid phase transitions relevant to planetary interiors for the first time.

Methods

A Nd:glass optical laser (527 nm, 20 ns quasi-flat-topped pulse duration) was used to launch an ablation-driven shock wave through the samples. Both 250 μm and 500 μm hybrid phase plates were used to ensure the sample was irradiated by a smooth and consistent laser intensity profile. The densities of the 50 μm polyimide ablator and 8 μm Bi starting material were 1.42 g/cc and 9.8 g/cc respectively. To probe the behaviour of Bi below ~3 GPa the phase plates were removed and the beam was defocused to a diameter of 1 mm. In all cases, the compressed region was greater than the 260 μm field of view of the VISAR and the quality of drive planarity was assessed from the planarity of the break out in the free surface/particle velocity history, as measured by the VISAR. Variations in break out time were generally less then 2% over the 50 × 50 μm2 region probed by the X-ray beam (red shaded box in Fig. S1 top). The free surface velocity is then extracted using the fast Fourier transform method (FFT) (Fig. S1 bottom)35. Two VISAR legs where employed to resolve fringe-jump ambiguity from the compressed sample velocity traces. The LCLS provided quasi-monochromatic (ΔE/E = 0.5%) 8.8 or 10.0 keV X-ray pulses of 80 fs duration and with ~1012 photons per pulse. The X-ray beam was focused to 50 × 50 μm2 and then centered on the focal-spot of the drive lasers, which, in turn, was centered on the target. Three CSPAD Quad 560k detectors and two smaller CSPAD 140k detectors were arranged in a transmission geometry to provide a two-theta range of ~20–110° and partial azimuthal coverage from ~−150° to 150°. The samples, which were cut into 2 mm squares were glued onto three 9 cm × 6 cm Al target holder plates before being mounted onto the MEC target holder and placed in the target chamber. Several X-ray calibrants, such as CeO2 and LaB6, were also loaded onto the target mount to determine the sample-to-detector distances and tilts. In addition, a fluorescent YAG (Yttrium Aluminium Garnet) sample was loaded in order to align the drive lasers with the VISAR laser. The VISAR collection duration was 50 ns.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

British Crown Owned Copyright 2018/AWE. M.I.M. and J.S.W. would like to acknowledge support from EPSRC under Grant Nos EP/J017256/1 and EP/J017051/1. D.M. is supported by LLNS under contract B595954. The work by J.H.E., D.E.F., R.F.S. R.B. and M.G.G. was performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract DE-AC52-07NA27344. C.A.B. would like to acknowledge support from Science Campaign 2 and A.E.G. from Reines LDRD at Los Alamos National Laboratory, which is operated for the National Nuclear Security Administration of the U.S. Department of Energy under contract DE-AC52-06NA25396. Use of the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. The MEC instrument is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Fusion Energy Sciences under Contract No. SF00515. We would like to thank Carol A. Davis and Paul Mirkirimi of LLNL for their help in preparing the Bi targets.

Author Contributions

A.C., R.B., C.B., A.G., M.S. and S.R. participated in the experiment and contributed to the data analysis and interpretation; H.J.L., E.G. and E.G. each participated in the experiment as instrument scientists at MEC and contributed to data interpretation; J.E., G.C. and J.W. each contributed to the data analysis and interpretation; C.S. and D.F. performed the liquid data analysis and contributed to the interpretation of the paper; R.S. contributed to the data analysis and interpretation and provided support in VISAR interpretation; D.M. participated in the experiment and contributed to the data analysis by writing software to examine XRD data; M.M. was principal investigator, and with R.M., participated in the experiment, helped with analysis of the data and writing the paper. M.G. took a lead role in the experiment, analysis of the data and writing of the paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-35260-3.

References

- 1.Degtyareva O, McMahon MI, Nelmes RJ. High-pressure structural studies of group-15 elements. High Pressure Research. 2007;24:319–356. doi: 10.1080/08957950412331281057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMahon MI, Degtyareva O, Nelmes RJ. Ba-IV-Type Incommensurate Crystal Structure in Group-V Metals. Physical Review Letters. 2000;85:4896–4899. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.4896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gleason AE, et al. Ultrafast visualization of crystallization and grain growth in shock-compressed SiO2. Nature Communications. 2015;6:ncomms9191. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorman MG, et al. Direct Observation of Melting in Shock-Compressed Bismuth With Femtosecond X-ray Diffraction. Physical Review Letters. 2015;115:095701. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.095701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Briggs R, et al. Ultrafast X-Ray Diffraction Studies of the Phase Transitions and Equation of State of Scandium Shock Compressed to 82 GPa. Physical Review Letters. 2017;118:025501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.025501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gleason, A. E. et al. Compression Freezing Kinetics of Water to Ice VII. Physical Review Letters119 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Kraus D, et al. Nanosecond formation of diamond and lonsdaleite by shock compression of graphite. Nature Communications. 2016;7:ncomms10970. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes DS, Gourley LE, Gourley MF. Shock-Wave Compression of Iron and Bismuth. Journal of Applied Physics. 1961;32:624–629. doi: 10.1063/1.1736060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duff RussellE, Minshall FStanley. Investigation of a Shock-Induced Transition in Bismuth. Physical Review. 1957;108:1207–1212. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.108.1207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asay JR. Shock loading and unloading in bismuth. Journal of Applied Physics. 1977;48:2832–2844. doi: 10.1063/1.324144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romain JP. Phase transformation in bismuth under shock loading. Journal of Applied Physics. 1974;45:135–139. doi: 10.1063/1.1662947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu J, et al. Complex structural dynamics of bismuth under laser-driven compression. Applied Physics Letters. 2013;103:161904. doi: 10.1063/1.4825276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenberg Z. Determination of the dynamic phase transitions in bismuth with in-material manganin gauges. Journal of Applied Physics. 1984;56:3328–3329. doi: 10.1063/1.333855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pélissier JL, Wetta N. A model-potential approach for bismuth (I) Densification and melting curve calculation, Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications. 2001;289:459–478. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan Y, et al. Hugoniot and sound velocity measurements of bismuth in the range of 11–70GPa. Journal of Applied Physics. 2013;113:093509. doi: 10.1063/1.4792755. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukherjee D, Sahoo BD, Joshi KD, Gupta SC. On equation of state, elastic, and lattice dynamic stability of bcc bismuth under high pressure: Ab-initiocalculations. Journal of Applied Physics. 2014;115:053702. doi: 10.1063/1.4863785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shu Yu, et al. Deep melting reveals liquid structural memory and anomalous ferromagnetism in bismuth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2017;114:3375–3380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1615874114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emuna M, Matityahu S, Yahel E, Makov G, Greenberg Y. A reversible transition in liquid Bi under pressure. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 2018;148:034505. doi: 10.1063/1.5001916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eggert JH, Weck G, Loubeyre P, Mezouar M. Quantitative structure factor and density measurements of high-pressure fluids in diamond anvil cells by x-ray diffraction:Argon and water. Physical Review B. 2002;65:174105. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.65.174105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hubbell JH, et al. Atomic form factors, incoherent scattering functions, and photon scattering cross sections. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 1975;4:471–538. doi: 10.1063/1.555523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsuji K, et al. Pressure dependence of the structure of liquid group 14 elements. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 2004;16:S989. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/20/11/114106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin C, et al. A metastable liquid melted from a crystalline solid under decompression, Nature. Communications. 2017;8:14260. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenberg Y, et al. Evidence for a temperature-driven structural transformation in liquid bismuth. EPL (Europhysics Letters) 2009;86:36004. doi: 10.1209/0295-5075/86/36004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yaoita K, et al. The structure of liquid bismuth under pressure. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids. 1992;150:25–28. doi: 10.1016/0022-3093(92)90088-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turneaure SJ, Gupta YM. Inelastic deformation and phase transformation of shock compressed silicon single crystals. Applied Physics Letters. 2007;91:201913. doi: 10.1063/1.2814067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akahama Y, Kawamura H, Singh AK. Equation of state of bismuth to 222 GPa and comparison of gold and platinum pressure scales to 145 GPa. Journal of Applied Physics. 2002;92:5892–5897. doi: 10.1063/1.1515378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cox GA. A multi-phase equation of state for bismuth. AIP Conference Proceedings. 2007;955:151–154. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith RF, et al. Time-dependence of the alpha to epsilon phase transformation in iron. Journal of Applied Physics. 2013;114:223507. doi: 10.1063/1.4839655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith RF, et al. Ultrafast Dynamic Compression Technique to Study the Kinetics of Phase Transformations in Bismuth. Physical Review Letters. 2008;101:065701. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.065701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rapp L, et al. Experimental evidence of new tetragonal polymorphs of silicon formed through ultrafast laser-induced confined microexplosion. Nature Communications. 2015;6:7555. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jenei, Z., Evans, W. J., Konopkova, Z., Liermann, H. P. & Kono, Y. Time resolved x-ray diffraction: dynamics of pressure induced structural phase transition in bismuth. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory Report, LLNL-CONF-703240 (2016).

- 32.Katzke H, Tolédano P. Displacive mechanisms and order-parameter symmetries for the A7-incommensurate-bcc sequences of high-pressure reconstructive phase transitions in Group Va elements. Physical Review B. 2008;77:024109. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.77.024109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katayama Y, et al. A first-order liquid-liquid phase transition in phosphorus. Nature. 2000;403:170–173. doi: 10.1038/35003143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiba A, Tomomasa M, Higaki T, Hayakawa T, Tsuji K. Pressure and temperature dependence of the structure of liquid arsenic and antimony. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2008;98:012011. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/20/11/114106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Celliers PM, et al. Line-imaging velocimeter for shock diagnostics at the OMEGA laser facility. Review of Scientific Instruments. 2004;75:4916–4929. doi: 10.1063/1.1807008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asay JR. Shock-induced melting in bismuth. Journal of Applied Physics. 1974;45:4441–4452. doi: 10.1063/1.1663070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larson DB. A Shock-Induced Phase Transformation in Bismuth. Journal of Applied Physics. 1967;38:1541–1546. doi: 10.1063/1.1709720. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walsh JM, Rice MH, McQueen RG, Yarger FL. Shock-Wave Compressions of Twenty-Seven Metals. Equations of State of Metals. Physical Review. 1957;108:196–216. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.108.196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Häussermann U, Söderberg K, Norrestam R. Comparative Study of the High-Pressure Behavior of As, Sb, and Bi. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2002;124:15359–15367. doi: 10.1021/ja020832s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.