Abstract

Recessive SLC25A46 mutations cause a spectrum of neurodegenerative disorders with optic atrophy as a core feature. We report a patient with optic atrophy, peripheral neuropathy, ataxia, but not cerebellar atrophy, who is on the mildest end of the phenotypic spectrum. By studying seven different non-truncating mutations, we found that the stability of the SLC25A46 protein inversely correlates with the severity of the disease and the patient’s variant does not markedly destabilize the protein. SLC25A46 belongs to the mitochondrial transporter family, but it is not known to have transport function. Apart from this possible function, SLC25A46 forms molecular complexes with proteins involved in mitochondrial dynamics and cristae remodeling. We demonstrate that the patient’s mutation directly affects the SLC25A46 interaction with MIC60. Furthermore, we mapped all of the reported substitutions in the protein onto a 3D model and found that half of them fall outside of the signature carrier motifs associated with transport function. We thus suggest that there are two distinct molecular mechanisms in SLC25A46-associated pathogenesis, one that destabilizes the protein while the other alters the molecular interactions of the protein. These results have the potential to inform clinical prognosis of such patients and indicate a pathway to drug target development.

Introduction

Recessive SLC25A46 mutations cause a syndromic spectrum, including optic atrophy, cerebellar atrophy, and axonal neuropathy (MIM# 616505) (Abrams et al., 2015). Specific presentations range from optic atrophy - plus disorder on the mild end of the spectrum to lethal Leigh syndrome and ponto-cerebellar hypoplasia in extreme cases (Janer et al., 2016; Wan et al., 2016; Yu-Wai-Man et al., 2016). The wide variability of clinical presentations in SLC25A46 patients likely reflects the different degrees of partial functionality conferred by different combinations of biallelic mutations. Complete loss of the SLC25A46 protein has been described with a homozygous exon 1 deletion, and a homozygous splice-site mutation, both of which are predicted to eliminate the protein product and cause infant lethality (Nguyen et al., 2017; Wan et al., 2016).

SLC25A46 is a distant member of the mitochondrial carrier family. While carriers typically reside in the inner mitochondrial membrane and transport solutes, SLC25A46 localizes to the outer mitochondrial membrane and is the closest human homolog to Ugo1, a yeast protein involved in mitochondrial fusion (Abrams et al., 2015; Palmieri, 2013; Sesaki & Jensen, 2001). In humans, dominant mutations in the canonical mitochondrial fusion genes MFN2 and OPA1 cause axonal peripheral neuropathy (Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 2A) and dominant optic atrophy, respectively (Alexander et al., 2000; Delettre, Lenaers, Pelloquin, Belenguer, & Hamel, 2002; Zuchner et al., 2004). Mutations in MFN2 can also cause optic atrophy in addition to axonal neuropathy, indicating overlap between these clinical presentations (Zuchner et al., 2006). A conditional Mfn2 knockout mouse (Chen, McCaffery, & Chan, 2007) shows early onset cerebellar degeneration and lethality similar to Slc25A46 knockout mice (Li et al., 2017; Terzenidou et al., 2017). While an axonal sensory polyneuropathy has been described in cattle caused by mutations in the SLC25A46 orthologue (Duchesne et al., 2017). The optic nerve, long peripheral axons, and Purkinje cells seem to be the most affected systems in patients and animal models with mutations in SLC25A46, MFN2, or OPA1.

Although the precise function of SLC25A46 is currently unknown, it is possible that it facilitates transport across the mitochondrial membrane or functions as a molecular adaptor protein similar to Ugo1 (Hoppins, Horner, Song, McCaffery, & Nunnari, 2009; Sesaki & Jensen, 2004). In support of the adaptor hypothesis, SLC25A46 has been shown to molecularly interact with both OPA1 and MFN2, indicating that it could play a direct role in mitochondrial fusion/fission dynamics through these interactions (Janer et al., 2016; Steffen et al., 2017). Additionally, SLC25A46 forms a complex with the cristae remodeling protein MIC60 also known as IMMT/Mitofilin and abnormal cristae and alterations in fusion/fission dynamics have been observed in several models (Abrams et al., 2015; Duchesne et al., 2017; Janer et al., 2016; Steffen et al., 2017; Terzenidou et al., 2017).

We report a 6-year-old boy with bilateral optic atrophy, axonal neuropathy, ataxia, but no cerebellar atrophy, carrying a novel homozygous missense variant NM_138773.1 c.770G>A, p.(Arg257Gln) p.R257Q. Given the young age of the patient and the differential effects of SLC25A46 mutations on disease severity and life span, we wanted to assess the functional consequences of this variant. We present data on protein stability, molecular interactions, and protein modeling which compare this novel variant to 7 other previously reported substitutions in the protein. While the substitutions found in severely affected patients completely destabilize the SLC25A46 protein, our patient’s p.R257Q variant produces a relatively stable protein product. Furthermore, we demonstrate that p.R257Q disrupts the assembly or reduces the stability of a higher molecular weight SLC25A46 complex containing MIC60, implicated in cristae remodeling. Finally, we built a protein model that shows the locations of all of the variants reported in SLC25A46 thus far. Our model indicates that the mildest substitutions p.R257Q and p.G249D fall into a distinct domain of the protein not associated with canonical transporter function. A major clinical challenge for patients with rare diagnoses, such as those with recessive mutations in SLC25A46, is the shift from diagnostic uncertainty to prognostic uncertainty. One avenue to resolve prognostic uncertainty can be found in informative functional studies, as presented in this paper.

Results

Clinical Report

We report on a 6-year-old boy with a history of chronic progressive ataxia and bilateral optic atrophy (Figure 1a). He is the eldest of two children to healthy parents who were not known to be consanguineous; however, both maternal and paternal grandfathers originated from the same village in Turkey. Our patient has a 9-month-old sister, who is well with no developmental concerns. There is no family history of ataxia, neuromuscular or neurometabolic disorders. The proband was born at 38+4 weeks’ gestation by normal vaginal delivery, following an uneventful pregnancy with normal antenatal scans. Unusual eye movements were first noted at 8 months of age. Ophthalmological examination revealed bilateral optic atrophy with an abnormal retinal sheen, bilateral hypermetropia and possible nyctalopia.

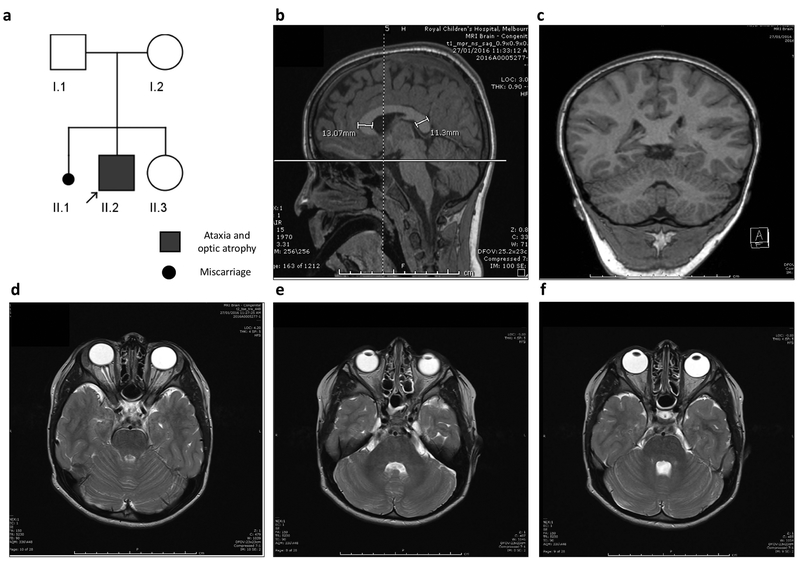

Figure 1. Pedigree of SLC25A46 patient and MRI images.

(a) Pedigree of index patient (arrow) homozygous for the c.770G>A p.Arg257Gln (p.R257Q) variant. Both parents were confirmed carriers for the mutation. (b-f) Sagittal, coronal, and serial axial MRI images obtain at the age of 5½ years, demonstrating normal appearance of the cerebellar vermis and hemispheres. The corpus callosum is diffusely thick with the genu slightly thicker than the splenium (b). The cerebellum and optic nerve appearance are within the normal limits for age.

Ataxia was noted when this patient began to walk at 15 months of age. Initial nerve conduction studies at 2 years of age were normal. At 6 years of age, he presented with worsening ataxia. Repeat nerve conduction studies confirmed a chronic axonal peripheral motor neuropathy. Audiology at 3 years of age was normal.

Examination at 6 years of age revealed a weight of 29 kg (99th centile), height of 120 cm (90th centile), head circumference of 53 cm (75–90th centile), and no dysmorphic features. On neurological examination the patient demonstrated a wide-based, ataxic gait, downgoing plantar response, whilst deep tendon reflexes could not be elicited. There was wasting distally in the lower limbs.

Normal biochemical investigations included plasma amino acids, lysosomal enzymes, very long chain fatty acids, lactate, ammonia and homocysteine levels. Urine metabolic screen including urine organic acids was also normal. Three brain MRIs (at 10 months, 3 years and 5½ years of age) and a cerebral perfusion study (at 4½ years of age) were all normal, with no deep nuclei or cerebellar abnormality identified (Figure 1b–f).

Genetic Investigations

SNP microarray revealed several long contiguous stretches of homozygosity (LCSH) comprising approximately 0.8% of the genome. Interrogation of the LCSH regions using the Genomic Oligoarray and SNP Evaluation tool (Wierenga, Jiang, Yang, Mulvihill, & Tsinoremas, 2013) identified multiple genes in association with ataxia alone, optic atrophy alone, and a single gene whose phenotype combined both ataxia and optic atrophy, SLC25A46.

Whole exome sequencing (WES) identified a homozygous missense variant in SLC25A46, c.770G>A, p.(Arg257Gln) p.R257Q (Figure 2a).

Figure 2. Genomic positions and Clustal alignments of reported mutations in SLC25A46.

(a) Schematic gene diagram of SLC25A46 (NM_138773.1, 1,257 base pairs, 418 amino acids). The relative locations of mutations are indicated by red arrows with the letters correspond to the family ID’s listed in (table 1), new patient is A*. The mitochondrial solute carrier domains (MC) are depicted in blue. (b) Clustal alignment demonstrating the conservation of residues in human, cow, mouse, zebrafish, nematode, and the two paralogues in drosophila.

This is a novel variant in exon 8, not previously reported in disease or population databases (ExAC, EVS). It affects a highly-conserved residue (Figure 2b) that is predicted to be disease-causing by in-silico tools (SIFT, PolyPhen, MutationTaster, CADD score). Parental segregation studies confirm that both parents are carriers for the SLC25A46 variant detected in the proband, which has been submitted to Clinvar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/559386/).

The SLC25A46 gene was first described in August 2015 and there have been 9 patients reported to date with mutations in this gene (Abrams et al., 2015; Charlesworth et al., 2016; Janer et al., 2016; Nguyen et al., 2017; Wan et al., 2016). All reported individuals have compound heterozygous or homozygous variants and all have optic atrophy and neuropathy (Figure 2a) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Phenotypes and genotypes of individuals with SLC25A46 pathogenic mutations

| Family ID | Variant studied | Patient, Ref, Country of Origin | SLC25A46 Variants | Age at Symptom Onset | Optic Atrophy | Neurological Features | Neuroimaging | Nerve Conduction Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | p.R257Q | Current patient (II.2) Turkey |

c.770G>A p.Arg257Gln (homozygous) |

8 months | + | - Hypotonia - Areflexia - Ataxia |

- Brain MRI (5.5y): thickened corpus callosum | Axonal peripheral motor neuropathy (6y) |

| B | p.G249D |

Abrams et al 2015 (1) United Kingdom |

c.165_166insC p.His56fs*94 c.746G>A p.Gly249Asp |

8 years | + | - Lower limb altered sensation and stiffness | - Brain CT and MRI (43y): normal | Axonal motor and sensory polyneuropathy (43y) |

| C | p.R340C |

Abrams et al 2015 (1) Italy |

c.1018C>T p.Arg340Cys (homozygous) |

2 years | + | - Ataxia and stepping gait - Severe lower limb hypotrophy - Pes cavus |

- Brain MRI (28y): diffuse brain and cerebellar atrophy, cerebellar white matter changes, marked chiasm atrophy - CT brain (44y): small calcifications of the basal ganglia |

Axonal sensorimotor polyneuropathy (18y) |

| D | p.E335D |

Abrams et al 2015 (1) Palestine |

c.1005A>T p.Glu335Asp (homozygous) |

1–2 years | + | - Gross and fine motor delay - Hypertonia - Hyper-reflexia - Ataxia |

- Brain MRI (22m): prominent extra-axial spaces - Brain MRI (5.2y): bilateral cerebellar encephalomalacia with increased gliosis signal - Brain MRI (11.5y): brainstem and cerebral volume loss |

Absent motor responses (excluding the right median nerve) (5y) |

| E | p.P333L |

Abrams et al 2015 (1) United States |

c.882_885dupTTAC p.Asn296fs*297 c.998C>T p.Pro333Leu |

Birth (deceased at 15 weeks) |

+ | - Hypotonia - Congenital contractures |

- Brain MRI (neonate): moderate cerebellar atrophy, mild brainstem atrophy - Brain MRI (3m): severe atrophy of cerebellar hemispheres and brainstem, diffuse volume loss |

Generalised neuropathy (3m) |

| F |

Nguyen et al 2017 (2) Morocco |

c.283+3G>T p.Ser32Thrfs*4 (homozygous) |

Birth (deceased at 7 days) |

+ | - Hypotonia - Myoclonic jerks |

- Brain MRI (neonate): atrophic cerebellar hemispheres, retrocerebellar arachnoid cyst, diffuse atrophy | Not tested | |

| G | p.T142I |

Janer et al 2016 (3) French Canadian |

c.425C>T p.Thr142Ile (homozygous) |

4 months (deceased at 13.5 months) |

Pale optic discs | - Psycho-motor delay - Hypertonia/spasticity |

- Brain MRI (13.5m): lesions in the cerebellar hemispheres, periaqueductal grey matter, brainstem and midbrain | Not tested Muscle biopsy: neurogenic atrophy, no ragged red fibres |

| H | p.L138R |

Charlesworth et al 2016 (4) Pakistan |

c.413T>G p.Leu138Arg (homozygous) |

Infancy | + | - Poor balance in infancy - Myoclonus (generalised, action induced, stimulus sensitive) - Cerebellar ataxia - Nystagmus, dysmetria, tremor |

- Brain MRI: cerebellar atrophy as well as T2/FLAIR (fluid-attenuated inversion recovery) hyperintensities and cavitations in the cerebellum | Axonal sensory-motor neuropathy leading to trophic changes |

| I |

Wan et al 2016 (5) Country of origin not specified |

c.1022T>C p.Leu341Pro (homozygous) |

Birth (died at 4 weeks of age) |

+ | - Myoclonic jerks - Flexion contractures (knees, elbows) |

- Brain MRI (5d): small cerebellum and brainstem | Severe axonal sensorimotor neuropathy |

|

| J |

Wan et al 2016 (5) Country of origin not specified |

5q22.1 (110738771–110740670) hmz del | Birth (died at 6 weeks of age) |

+ | - Hypotonia - Areflexia - Myoclonic jerks (occasional) |

- Brain MRI: pontocerebellar hypoplasia | Not tested |

The p.R257Q variant does not destabilize the protein

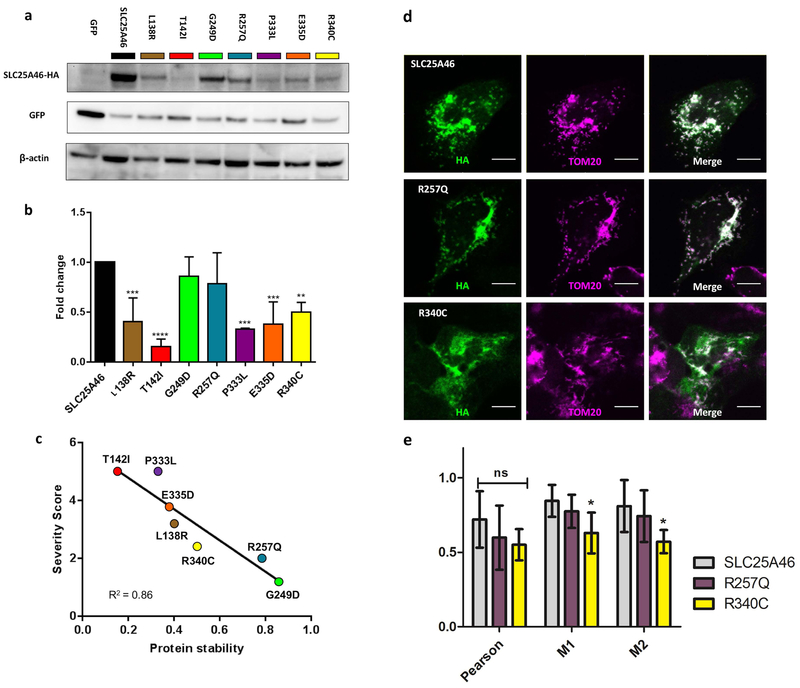

Given the wide range of disease severity associated with SLC25A46 mutations, we wanted to investigate the molecular mechanism that accounts for the variability in patient prognosis. A study by Wan and colleagues demonstrates that the p.L341P variant causes lethal ponto-cerebellar hypoplasia by destabilizing the protein and suggests that steady-state levels of the protein inversely correlate with the severity of the disease (Wan et al., 2016). We cloned and expressed our patient’s p.R257Q variant along with all of the mutations that had been reported during the timing of our study, p.L138R, p.T142I, p.G249D, p.P333L, p.E335D, and p.R340C. We did not investigate p.L341P because it was not known to us at the time. We transiently co-transfected HEK293T cells with each of the SLC25A46-HA tagged mutant variants. We then prepared whole cell lysates, 48 hours after transfection, and analysed the steady state levels of the proteins by immunoblotting. The p.P333L and p.T142I variants were the least abundant, while p.L138R, p.E335D, and p.R340C accumulated at intermediate levels. The p.G249D and p.R257Q variants were almost as abundant as the wildtype protein (Figure 3a). When we quantified this across multiple immunoblots, we found that all of the patient variants were significantly reduced in comparison to wildtype with the exception of p.G249D and p.R257Q, which were trending but not significantly reduced (Figure 3b) (Supp. Figure S1). Our findings corroborate the results reported by Wan and colleagues and further demonstrate that p.L138R, p.T142I, and p.R257Q follow the same trend. To illustrate this, we graded each point mutation from 0–5 points based on the clinical features reported in the proband: optic atrophy, cerebellar atrophy, neuropathy, wheel-chair bound, and early lethality. The presence of each clinical feature counts for 1 point if reported within the first decade of life, while 0.2 points were subtracted for each subsequent decade. For example, our patient developed optic atrophy and neuropathy within the first decade of life [1 optic atrophy + 1 neuropathy =2.0 points], while the proband possessing the p.G249D variant developed optic atrophy in the first decade of life [1 point] and neuropathy/spasticity four decades later [1 - (0.2 × 4 decades)=0.2 point] for a cumulative score [1 optic atrophy + 0.2 neuropathy =1.2 points]. Early lethality (death before 2 years of age), counted for the maximum 5 points regardless of whether or not the patient presented with all of the above criteria, the rationale being that the lethal cases are always the most severe. A summary of these calculations can be found in (Table 2). When we compared this clinical severity score to the average steady state levels of the protein, we find a definitive inverse correlation between protein stability and the severity of the syndrome R2=0.86 (Figure 3c).

Figure 3. Correlation of protein levels, severity of patient symptoms, and mitochondrial targeting of the SLC25A46 substitution variants.

(a) Representative Western blot of transiently transfected HEK293T cells with SLC25A46-HA mutations and GFP. Blots were probed against HA, GFP, and β-actin. The HA signal was normalized to GFP to control for the transfection efficiency. (b) Histogram shows the mean ± SD from three independent experiments, the relative protein levels of the mutations were normalized to SLC25A46 WT for each experiment. All of the mutations are significantly reduced in comparison to wildtype SLC25A46 with the exception of p.R257Q and p.G249D which were trending but not significant. (c) Correlation plot between the clinical severity scores from (Table 2) and the average relative protein levels determined by the Western blots. (d) Colocalization of wildtype SLC25A46, p.R257Q, and p.R340C with the mitochondria outer membrane marker TOM20 in U2OS cells. Wildtype and p.R257Q colocalize strongly with TOM20, while p.R340C shows less colocalization with the mitochondria. Scale bar 10 μm. (e) Quantification of three measures of colocalization; Pearson, Meanders 1 (M1), and Meanders 2 (M2). Significance was determined by a 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest with 6 cells per condition.

Table 2.

Calculation of patients’ severity score1

| Family ID | H | G | B | A | E | D | C | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substitution | p.L138R | p.T142I | p.G249D | p.R257Q | p.P333L | p.E335D | p.R340C | |||||||

| Age at Diagnosis | Age | Score | Age | Score | Age | Score | Age | Score | Age | Score | Age | Score | Age | Score |

| Optic atrophy | 15 yrs | (0.8) | <1 yrs | (1) | 8 yrs | (1) | <1 yrs | (1) | <1 yrs | (1) | 1.5 yrs | (1) | 2 yrs | (1) |

| Cerebellar atrophy | 15 yrs | (0.8) | <1 yrs | (1) | N/A | (0) | N/A | (0) | <1 yrs | (1) | 1.5 yrs | (1) | 28 yrs | (0.6) |

| Neuropathy | 15 yrs | (0.8) | <1 yrs | (1) | 43 yrs | (0.2) | 6 yrs | (1) | <1 yrs | (1) | 5 yrs | (1) | 14 yrs | (0.8) |

| Wheel chair bound | 15 yrs | (0.8) | N/A | (1) | N/A | (0) | N/A | (0) | N/A | (1) | 15 yrs) | (0.8) | N/A | (0) |

| Early lethality | N/A | (0) | 1.1 yrs | (1) | N/A | (0) | N/A | (0) | <1 yrs | (1) | N/A | (0) | N/A | (0) |

| Severity score | 3.2 | 5 | 1.2 | 2 | 5 | 3.8 | 2.4 | |||||||

| Average protein stability | 0.4 | 0.15 | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.50 | |||||||

The presence of each clinical feature counts for 1 point if reported within the first decade of life, while 0.2 points were subtracted for each subsequent decade. For example, our patient developed optic atrophy and neuropathy within the first decade of life [1 optic atrophy + 1 neuropathy = 2.0 points], while the proband possessing the G249D variant developed optic atrophy in the first decade of life [1 point] and neuropathy/spasticity four decades later [1 - (0.2 × 4 decades) = 0.2 point] for a cumulative score [1 optic atrophy + 0.2 neuropathy = 1.2 points]. Early lethality (death before 2 years of age), counted for the maximum 5 points regardless of whether or not the patient presented with all of the above criteria, the rationale being that the lethal cases are always the most severe.

SLC25A46 localizes to the outer mitochondrial membrane (Abrams et al., 2015). To ascertain if patient mutant variants are properly targeted to the mitochondria, the SLC25A46-HA tagged constructs were transiently transfected into Lenti-X™293T cells, which were visualized by immunostaining with HA and TOM20 (mitochondrial outer membrane marker) antibodies. The relative fluorescent intensity of the HA staining correlate with the abundance of the proteins found by immunoblotting (Supp. Figure S2). The p.R257Q variant has similar signal in comparison to p.G249D and wild-type, while p.L138R shows a decrease in signal intensity, while p.T142I is barely detectable. On the contrary, p.R340C shows a relatively strong signal, however it seems to mostly be outside of the mitochondria. Interestingly, all of the severe and moderately destabilizing variants show a similar diffuse cytoplasmic staining and discordance between HA and TOM20 localizations, while p.R257Q and p.G249D variants are comparable to wild-type suggesting that the instability of some of the variants could be partially driven by their miss-localization.

To further investigate the localization of the SLC25A46 proteins we turned to larger U2OS cells and focused primarily on wildtype, p.R257Q, and p.R340C because the less stable mutant proteins were not as easily detectable by immunocytochemistry. In transiently transfected cells, we found that wildtype and p.R257Q primarily colocalize with the mitochondrial TOM20 marker, while p.R340C has a more diffuse pattern that shows less correlation with the mitochondria (Figure 3d,e) and only partial overlaps with the ER (Supp. Figure S3). Meanwhile we found no significant correlation between any variants and the autophagosome markers p62 or LC3B (Supp. Figure S3 and data not shown). The p.L341P variant has been shown to be ubiquianated by MULAN and MARCH on the outer mitochondrial membrane and degraded by P97 and the proteasome (Steffen et al., 2017). A similar mechanism likely accounts for the instability of the intermediate and severe mutations. In conclusion, the p.R257Q substitution does not markedly reduce the steady-state levels of the SLC25A46 protein or alter its intracellular localization, as we observed for the other variants associated with the more severe clinical outcomes.

p.R257Q alters SLC25A46 protein-containing complexes

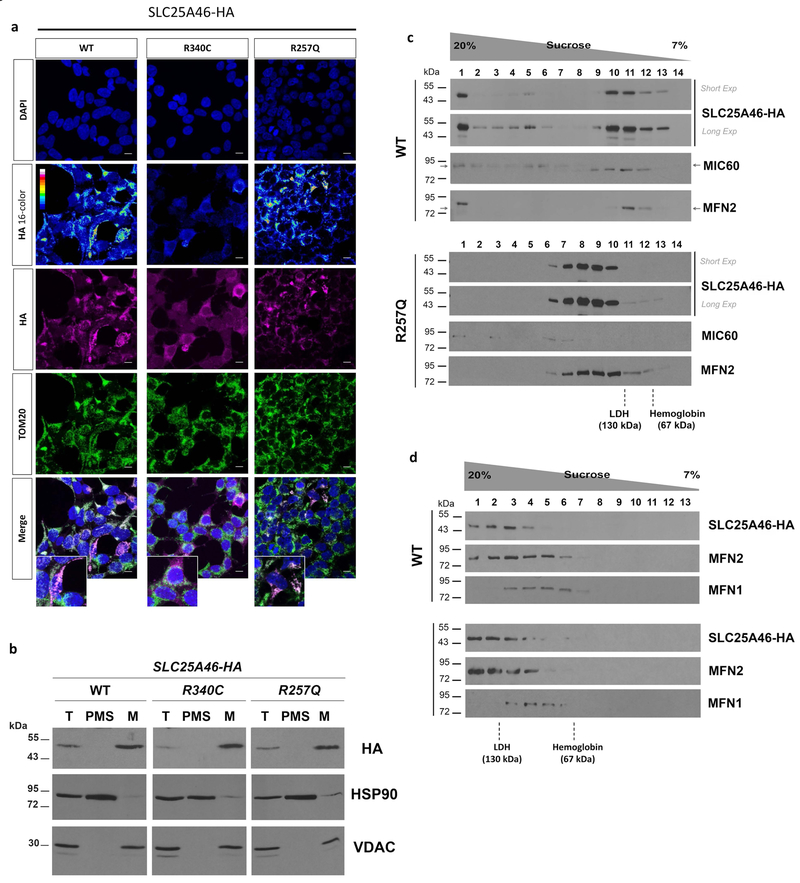

To further investigate the pathological mechanisms of the novel p.R257Q mutant protein, we generated stable HEK293T cells expressing wild-type, p.R257Q, and p.R340C variants, which show similar protein levels and co-localization observed by transient transfection (Figure 4a,b). We next performed cell fractionation to test whether mutant proteins miss-localize to the cytoplasm. Full length wild-type, p.R257Q and p.R340C proteins are enriched in isolated mitochondria, and no preferential accumulation of p.R340C is observed in the soluble cytoplasmic fraction (Figure 4b), suggesting that the diffuse non-mitochondrial signal observed by immunocytochemistry may be due to HA tag processing.

Figure 4. Analysis of SLC25A46 expression and native molecular weight in stable transfected HEK293T cells.

(a) Immunocytochemistry of cells expressing wildtype (WT), p.R257Q, or p.R340C variants. DAPI was used to visualize nuclei and an anti-TOM20 antibody was used as mitochondrial marker (b) Cell fractionation analysis of wildtype (WT), p.R257Q, and p.R340C transfected cells. Total cell lysate (T), post-mitochondrial supernatant (PMS), representing the cytosolic soluble fraction, and isolated mitochondria (M) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunostaining with antibodies against HA tag, HSP90, as cytosolic marker, and VDAC, as mitochondrial marker. (c) Sedimentation of wild-type SLC25A46-HA and p.R257Q in a linear 7–20% sucrose gradient centrifuged in a Beckman 55Ti rotor at 28,000 rpm for 12 hours. The proteins hemoglobin (67 kDa) and LDH (130 kDa) were used to calibrate the gradient. (d) Same as (c) although gradients were centrifuged at 45,000 rpm for 13 hours to resolve the lighter MFN2-containing complexes.

SLC25A46 is a derived outer mitochondrial membrane protein homologous to yeast Ugo1. Ugo1 has been proposed to function as a molecular adaptor protein in the mitochondrial fusion process through interactions with Fzo1 and Mgm1 (Hoppins et al., 2009; Sesaki & Jensen, 2004). Similarly, SLC25A46 forms molecular interactions with a number of mitochondrial dynamics and cristae remodelling proteins, including MIC60, MFN2, and OPA1 (Abrams et al., 2015; Janer et al., 2016; Steffen et al., 2017). SLC25A46 exists in at least two distinct protein complexes, of different molecular mass. Interactions with MFN2 and OPA1 occur in the lighter complex ~130 kDa, while those with MIC60 occur in heavier complexes (Abrams et al., 2015; Steffen et al., 2017). To investigate the effects of the p.R257Q variant on protein-protein interactions, mitochondria were isolated by differential centrifugation and SLC25A46 native molecular weight was investigated by sucrose gradient sedimentations analysis. We found that p.R257Q alters SLC25A46’s distribution leading to a significant loss of SLC25A46 in the faster sedimentation pools containing the heavy complexes, which in the case of the wild-type protein co-sediment with MIC60 (Figure 4c). Moreover, p.R257Q variant still co-sediment with MFN2, under two different sucrose gradient centrifugation conditions. However, this protein pool is shifted toward higher sucrose concentration fractions, suggesting an alteration in either the composition of the SLC25A46-MFN2 complex or its conformation (Figure 4c–d). Differently from MFN2, sedimentation properties of MFN1 are not affected by the p.R257Q variant (Figure 4d). However, the amount of MFN2 co-sedimenting with MFN1 is reduced by p.R257Q compare to WT (fraction 5 in Figure 4d), opening the possibility that p.R257Q variant may affect MFN1 function indirectly by altering MFN2 availability. Taken together, our data suggest that, since the p.R257Q variant is relatively stable in mitochondria (Supp. Figure S4), this mutation may directly impair SLC25A46 function by altering the molecular interactions with its mitochondrial partners. Notably, p.R257Q effect on the sedimentation profile of the SLC25A46 protein-containing complexes dramatically differ from those recently reported for the destabilizing p.L341P variant, which lead to the accumulation of SLC24A46 into the higher molecular weight complexes and loss of the lower molecular weight complexes containing MFN2 and OPA1 (Steffen et al., 2017).

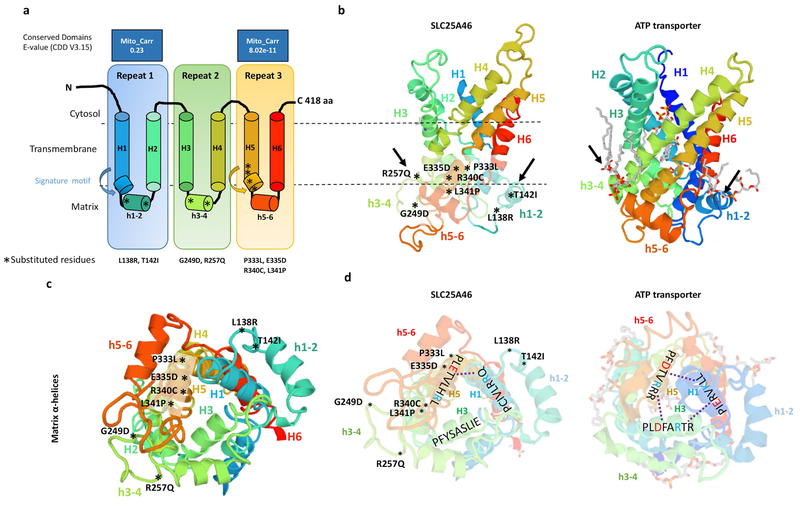

p.R257Q does not occur in the stereotypic transporter motif.

SLC25A46 is a highly derived member of the SLC25A mitochondrial carrier family for which there is no solved crystal structure. Using Swiss-Model, we threaded the SLC25A46 sequence onto the known structure of the bovine mitochondrial ADP/ATP translocase 1 (template: 2c3e.1.A) which is 16.55% identical. SLC25A46 has a longer N-terminus which does not align to the ATP transporter and is truncated from the 3D model (Figure 5 a–d). The positions of the (PX[D/E]XX[K/R]X[K/R]) signature motifs were inferred from the sequence alignment. Although the structure of SLC25A46 is likely very different from this model, the other highly derived carrier proteins, Ugo1 and MTCH2 have been threaded onto the same crystal structure (Coonrod, Karren, & Shaw, 2007; Robinson, Kunji, & Gross, 2012). Therefore the model is still informative for comparative purposes. Mitochondrial carriers are around 300 amino acids in length while SLC25A46 is 418 amino acids, having an extended N-terminus. All mitochondrial carriers have three well conserved mitochondrial carrier domains (Palmieri, 2013), but SLC25A46 has only one conserved carrier domain at 317–402 aa (e-value = 8.02e-11), while a lesser conserved domain occurs at 95–168 aa (e-value = 0.23) as predicted by NCBI’s conserved domain finder tool.

Figure 5. Predicted model of the SLC25A46 protein with the relative position of all reported point mutations.

(a) Topology of SLC25A46 inferred from homology to the mitochondrial carrier family. (b) Predicted 3D model of SLC25A46 based on threading to the crystal structure of the ATP transporter depicted to the right. Note the lipid chains in gray associated with the h3–4 and h1–2 helices of the ATP transporter, which are close to the relative position of the p.R257Q, p.G249D, p.L138R, and p.T142I mutations in SLC25A46. (c) SLC25A46 3D structure rotated to expose the matrix pore. The p.P333L, p.E335D, p.R340C, and p.P341L variants occur in the signature motif of H5, while the p.G249D, p.R257Q, p.L138R, and p.T142I occur in the minor h3–4 and h1–2 helices far away from the pore. (d) In the ATP transporter the (PX[D/E]XX[K/R]X[K/R]) signature motifs form salt bridges (dashed line) between the [D/E] and [K/R] residues between helixes 1,3,5. In SLC25A46 the signature motif is absent in H3 and most of the salt bridges are not predicted to form.

Typical mitochondrial carriers contain six transmembrane α-helices belonging to the three mitochondrial carrier domains that form a pore across the mitochondrial inner membrane. Each mitochondrial carrier domain has two long transmembrane helices (H1–H6), interspaced by a short α-helix (h1–2,h3–4,h5–6) and a PX[D/E]XX[K/R]X[K/R] (20–30 residues) [D/E]GXXXX[W/Y/F][K/R]G signature motif (Palmieri, 2013).

The molecular function of SLC25A46 is currently unknown. Two potential mechanisms have been hypothesized, either as a transporter or an adaptor. All SLC25A46 reported point mutations cluster into three distinct domains and the location of each provides molecular insight into the function of the protein. The vast majority of pathogenic mutations in other SLC25A proteins occur in the signature motifs associated with transporter function (Palmieri, 2013). Accordingly, SLC25A46 mutations p.P333L, p.E335D, p.R340C, and p.L341P occur within the H5 signature motif (Figure 5a,b). The signature motifs form a pore through salt bridges between the [D/E] and [K/R] residues of the PX[D/E]XX[K/R]X[K/R] (H1,H3,H5) and [D/E]GXXXX[W/Y/F][K/R]G (H2,H4,H6) (Robinson et al., 2012) (Figure 5c,d). However, in SLC25A46 the PX[D/E]XX[K/R]X[K/R] motif is absent in repeat 2 and most of the salt bridges are not predicted to form, suggesting that it may not function as a transporter (Figure 5d). In Ugo1, which is believed to primarily function as a physical adaptor protein, charge reversals in one of the PX[D/E]XX[K/R]X[K/R] repeats affects mitochondrial fusion by disrupting the formation of the Ugo1 homodimer without affecting the stability of the protein (Coonrod et al., 2007; Hoppins et al., 2009). Since all of the reported mutations in the third repeat PX[D/E]XX[K/R]X[K/R] residues of SLC25A46 decrease the stability of the protein, it is difficult to discern if the pathogenicity occurs through a loss of transport mechanism or disruption of protein-protein interactions, since both processes will be affected.

Meanwhile, the other half of the reported mutations, namely p.L138R, p.T142I, p.G249D, and p.R257Q, occur in the short h1–2 and h3–4 loops far away from the putative pore, suggesting that they do not directly affect transport (Figure 5c). Alternatively, we propose that they may affect SLC25A46 protein molecular interactions. The ATP carrier, ANT1 (SLC25A4), binds cardiolipin by clamping h1–2 to H6 and h3–4 to H2 at similar locations to p.L138R, p.T142I, p.G249D, and p.R257Q mutations (Figure 5b). In ANT1, the cardiolipin interactions help to stabilize the structure of the protein as well as mediate protein-lipid-protein interactions (Nury et al., 2005). Therefore the loss of the higher molecular weight SLC25A46-containing complex associated to the p.R257Q mutation could be dependent on the destabilization of a protein-lipid interaction on the outer mitochondrial membrane.

Discussion

There is a wide spectrum of clinical features associated with SLC25A46 mutations. Optic atrophy and axonal neuropathy are clinical features shared by all patients reported thus far, however the severity of the disease is variable and sometimes lethal (Abrams et al., 2015; Janer et al., 2016; Wan et al., 2016). The most destabilizing or lowest abundant variants are lethal. A patient with Leigh syndrome, who died at 14 months, was homozygous for the p.T142I amino acid change, which nearly eliminates the protein (Janer et al., 2016). Another patient, who died three months after birth, was found to have compound heterozygous mutations, one resulting in a truncation at 297 amino acids and the other p.P333L variant severely destabilizing the protein (Abrams et al., 2015). Meanwhile, a p.L341P variant reported to be severely destabilizing was identified in a proband, who died at 4 weeks of age (Wan et al., 2016). Many of the patient’s on the severe end of the spectrum have a diagnosis consistent with ponto-cerebellar hypoplasia type 1 (PCH1) and complete loss-of-function mutations were recently identified in the original Dutch PCH1 family (van Dijk et al., 2017).

Intermediate levels of the protein do not seem to have such a strong effect on life span, although the severity of symptoms is variable. One patient with a homozygous p.R340C substitution showed optic atrophy, peripheral neuropathy, and diffuse brain and cerebellar atrophy at 28 years of age, while the individual with the p.E335D variant showed bilateral cerebellar encephalomalacia at only 5 years of age (Abrams et al., 2015).

The most abundant variant, p.G249D, was identified in a patient with a second mutation in trans resulting in a 94 amino acid truncation. This patient represents the mildest form of the disease with optic atrophy in the first decade of life, but development of spasticity and axonal neuropathy only in the late 40’s with no cerebellar abnormalities (Abrams et al., 2015). In our functional assays, we found that our patient’s homozygous p.R257Q mutation has the most similar protein stability and mitochondrial localization to p.G249D, and that the two residues converge on the same functional domain of the protein. Although the p.R257Q patient is still less than 10 years of age, given the current lack of cerebellar abnormalities and relative stability of the protein, we are optimistic for the patient’s prognosis. A major clinical challenge for patients with rare diagnoses identified through genomic testing, such as those with recessive mutations in SLC25A46, is the shift from diagnostic uncertainty to that of prognostic uncertainty. The results of our study help to answer the question as to why there is such a wide clinical variability and provide insights for other patients with mutations in the gene. It is now clear that the severity of the SLC25A46 optic atrophy spectrum disorders is directly proportional to the levels of the protein with higher levels related to a milder clinical phenotype.

SLC25A46 has a rather elusive role in mitochondrial dynamics and has been suggested to affect either mitochondrial fission or fusion (Abrams et al., 2015; Duchesne et al., 2017; Janer et al., 2016; Steffen et al., 2017; Terzenidou et al., 2017; Wan et al., 2016). Differences in these observations could reflect the degrees of partial functionality conferred by the SLC25A46 variants and the different cell types investigated. However, both fusion and fission processes require close apposition of the outer and inner membranes of the mitochondria and SLC25A46 is a well-established player in the interactome of proteins involved in the mitochondrial contact sites. Aside from its proposed role in mitochondrial dynamics, it could be a transporter across the outer and/or inner mitochondrial membranes (Abrams et al., 2015). These hypotheses are not mutually exclusive and the locations of all of the reported mutations to date support both. Since the p.R257Q and p.G249D variants do not markedly destabilize the protein, they provide greater molecular insight into the function of SLC25A46. Interestingly these mutations occur at similar locations to the cardiolipin binding sites in ANT1 (SLC25A4). This suggests that they could facilitate lipid-protein binding rather than directly facilitate transport. ANT1 dimerization is thought to occur through these lipid interactions (Nury et al., 2005).

SLC25A46 is the most similar mammalian Ugo1 homolog; both proteins localize to the outer mitochondrial membrane and have lost most of their carrier motifs (Abrams et al., 2015). Ugo1 is not thought to be a transporter because molecules up to 5 kDa can passively diffuse through porin channels in the outer mitochondrial membrane (Coonrod et al., 2007). Ugo1 is hypothesized to function as a physical adaptor protein at the outer-inner membrane contact sites through its interactions with Mgm1 (OPA1) and Fzo1 (MFN1/2) where it facilitates the final lipid-mixing step of the mitochondrial fusion mechanism (Hoppins et al., 2009; Sesaki & Jensen, 2004). Similarly, SLC25A46 has been reported to interact with the homologs OPA1 and MFN2, indicating that it could also play a role in mitochondrial dynamics through its interactions with these proteins (Janer et al., 2016). Additionally, both Ugo1 and SLC25A46 form a complex with the cristae remodelling homologs, Fcj1 and MIC60 (Mitofilin) (Abrams et al., 2015; Harner et al., 2011; Janer et al., 2016).

The p.R257Q mutation disrupts SLC25A46’s interaction with the MIC60-containing complex and could cause a cristae defective phenotype similar to the lack of the protein despite not affecting the overall stability of the SLC25A46 protein (Janer et al., 2016). Additionally p.R257Q may not severely alter mitochondrial dynamics because it does not abolish the SLC25A46-MFN2 interaction, as reported for the destabilizing p.L341P mutation (Steffen et al., 2017). However, the p.R257Q variant seems to favour the accumulation of the larger MFN2-containing complex, which could ultimately impact the balance between mitochondrial fusion and fission. Overall, our results suggest that SLC25A46 plays a direct role in mitochondrial dynamics through its molecular interactions in the SLC25A46-protein complexes independent of any potential carrier function.

There is growing evidence that other members of the SLC25A family play a role mitochondrial in dynamics. OPA1-dependent cristae remodelling is facilitated through its direct interactions with members of the SLC25A family (Patten et al., 2014). Recently, it has been demonstrated that SLC25A38 (appoptosin) which functions as an inner membrane glycine and gamma-aminolevulinic acid transporter, also interacts with MFN1 and MFN2, and plays a role in mitochondrial dynamics independent of its carrier function (Zhang et al., 2016).

Could other SLC25A proteins cause similar neurological features as those reported for SLC25A46? The range of clinical features; optic atrophy, ataxia, axonal neuropathy, cerebellar hypoplasia, seems to be specific to SLC25A46 dysfunction versus other carrier syndromes. Each carrier seems to be somewhat specific for various tissues such as heart, liver, muscle, or brain (Palmieri & Monne, 2016). It is likely that the defects observed for SLC25A46 reflect its high expression in the central nervous system (Haitina, Lindblom, Renstrom, & Fredriksson, 2006). SLC25A40, which is also highly expressed in the central nervous system, is a candidate gene for pontocerebellar hypoplasia type III (Durmaz et al., 2009). Therefore it’s possible that other carriers could show overlapping features, however none have shown as broad of a spectrum as reported for SLC25A46.

SLC25A46-associated syndromes occur through a loss-of-function mechanism despite the unclear function of the protein. Since most of the reported mutations affect the stability of the protein, it is difficult to test how they might affect protein function either through disrupting transport or protein-protein interactions. Therefore, the additional discovery of the p.R257Q mutation as a stable variant outside of the carrier motif provides an additional tool to gain insight into the role of SLC25A46 in mitochondrial function and dynamics and potentially guide the development of therapeutic interactions.

Material and Methods

Genetic analysis

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood and SNP microarray was performed using the Illumina HumanCytoSNP12 v2.1 assay following the manufacturers protocols and analysed using Illumina Karyostudio 1.4.3.0 (Build37) analysis software. Whole exome sequencing was performed using Nextera Rapid Exome Capture Kit and HiSeq 3000/4000 SBS reagents on a HiSeq 4000, and bioinformatics analysis was undertaken using Cpipe (Sadedin et al., 2015). Sequencing analysis occurred on the GENESIS software platform as previously described (Abrams et al., 2015; Gonzalez et al., 2015).

Cell Culture

HEK293T, Lenti-X™ 293T, and U2OS cells were grown in DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and incubated at 37°C. Stable HEK293T cells were generated by transfecting the pIRESpuro2 plasmids using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were transfect a total of 3 times in two day increments and selected in DMEM containing 5μg/mL of puromycin. Cells were maintained in 1 μg/mL puromycin-containing DMEM media.

Western Blot

Hek293T cells were seeded to 75% confluence in a 6-well plate and transiently transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s protocol. 3 μg of each SLC25A46-HA construct was mixed with 1 μg GFP-pcDNA3.1 as a transfection control. 48 hours later, whole lysates were scraped and extracted in RIPA (Thermo Scientific) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). After sonication and centrifugation, protein lysates were quantified by BCA (Thermo Scientific). 50 μg of sample were loaded per well using the Bolt® system and reagents (Invitrogen). The following antibodies were used, anti-HA mouse (6E2) from Cell Signalling; anti-Tom20 rabbit (SC-11415); anti-GFP mouse (SC-9996) from Santa Cruz; anti-β-actin mouse (A5541) from Sigma. Blots were probed with corresponding secondary HRP-conjugated antibodies (Cell Signalling) and developed with SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Fisher). Relative amounts SLC25A46 variants were quantified using Fiji Analyze Gel feature. For each sample, the HA band was divided by the area of the GFP, to control for both transfection efficiency and relative cell number. Each ratio was then divided by SLC25A46 wildtype to calculate a fold change for each variant in comparison to wildtype. Significance was determined by a one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test from 3 experiments.

Immunofluorescence

Lenti-X™293T, HEK 293T, and U2OS cells were seeded to 75% confluence onto glass coverslips and transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde for 20 min, permeabilized with cold methanol for 5 min and stained with the following antibodies: from Cell Signalling, anti-HA mouse (6E2), anti-HA rabbit (C29F4), anti-Lc3b rabbit (D11) XP; anti-SQSTM1/p62 mouse (D5L7G); anti-Tom20 rabbit (SC-11415) Santa Cruz, and anti-Calnexin rabbit (C4731) Sigma. Corresponding Alexa Fluor® conjugated secondary antibodies (Life Technologies) were used for detection. Coverslips were mounted onto slides and 1 μm z-stacks were acquired with a Zeiss LSM710 confocal microscope (63X/1.4 oil objective) from one imaging session using the same settings for all samples. Images were aquired at 8-bit depth with 1000×1000 pixel frame size. Relative flourescent parmameters were calculated using Fiji. Maximum intensity z-projections were converted to a 32-bit image and thresholded to convert all pixels below 50 AU (arbitrary units) to NaN (not a number). Cells were manualy traced to calculate average pixel intenstity and total pixel number (above 50 AU), using the histogram feature. 15 to 23 cells for each condition were captured in the data set. Significance was determined by a one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test. Colocalization analysis was performed using Coloc2 in Fiji with at least 6 cells per condition.

Sucrose gradient analysis

Mitochondria were isolated from stably transfected Hek293T cells expressing either wild-type SLC25A46-HA or the R257Q variant as previously reported (Fernandez-Vizarra et al., 2010). Mitochondrial proteins (0.8 mg) were solubilized with 0.8% digitonin in a final volume of 0.08 mL of extraction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4 and 0.5 mM PMSF). Clarified extracts were obtained by centrifugation at 20,000g for 15 minutes at 4°C, mixed with standard proteins (Hemoglobin and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)) and applied to a 7–20% sucrose gradient prepared in extraction buffer containing 0.1% digitonin. Gradients were centrifuged in a Beckman 55Ti rotor either a 28,000 rpm for 12 hours or at 45,000 rpm for 13 hours at 4°C. Equal volume fractions were collected from the bottom of the gradients and assayed for haemoglobin by absorption at 409 nm and for LDH activity by measuring the rate of NADH-dependent pyruvate to lactate conversion. Proteins were concentrated by trichloroacetic acid precipitation, resolved in a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and analysed by immunoblotting.

3D modeling

The SLC25A46 FASTA sequence (Q96AG3) was uploaded unto the SWISS-MODEL web browser (https://swissmodel.expasy.org) and was aligned to bovine mitochondrial ADP/ATP translocase 1 (template: 2c3e.1.A), identity 16.55. The position of the (PX[D/E]XX[K/R]X[K/R]) signature motifs were inferred from this sequence alignment. Note that SLC25A46 has a longer N-terminus which does not align to the ATP transporter and is automatically truncated from the 3D model.

Plasmids

SLC25A46-HA was sub-cloned into pcDNA3.1 using Q5 polymerase, introducing a 5’-NheI and 3’-BamHI site. Mutation constructs were generation using Q5® Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (NEB) and online tools. For stable transfections, SLC25A46-HA and mutations were subcloned into pIRESpuro2 between the NheI and BamHI sites.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the family for participating in this study.

Funding

We would like to acknowledge the family for participating in this study. This work was supported by the NIH [R01NS075764] and [U54NS065712] to S.Z. and F.F. is supported by an AHA development grant.

Grant Numbers: R01NS075764 and U54NS065712

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Abrams AJ, Hufnagel RB, Rebelo A, Zanna C, Patel N, Gonzalez MA, … Dallman JE (2015). Mutations in SLC25A46, encoding a UGO1-like protein, cause an optic atrophy spectrum disorder. Nat Genet, 47(8), 926–932. doi: 10.1038/ng.3354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander C, Votruba M, Pesch UE, Thiselton DL, Mayer S, Moore A, … Wissinger B (2000). OPA1, encoding a dynamin-related GTPase, is mutated in autosomal dominant optic atrophy linked to chromosome 3q28. Nat Genet, 26(2), 211–215. doi: 10.1038/79944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth G, Balint B, Mencacci NE, Carr L, Wood NW, & Bhatia KP (2016). SLC25A46 mutations underlie progressive myoclonic ataxia with optic atrophy and neuropathy. Mov Disord, 31(8), 1249–1251. doi: 10.1002/mds.26716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, McCaffery JM, & Chan DC (2007). Mitochondrial fusion protects against neurodegeneration in the cerebellum. Cell, 130(3), 548–562. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coonrod EM, Karren MA, & Shaw JM (2007). Ugo1p is a multipass transmembrane protein with a single carrier domain required for mitochondrial fusion. Traffic, 8(5), 500–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00550.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delettre C, Lenaers G, Pelloquin L, Belenguer P, & Hamel CP (2002). OPA1 (Kjer type) dominant optic atrophy: a novel mitochondrial disease. Mol Genet Metab, 75(2), 97–107. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2001.3278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchesne A, Vaiman A, Castille J, Beauvallet C, Gaignard P, Floriot S, … Vilotte JL (2017). Bovine and murine models highlight novel roles for SLC25A46 in mitochondrial dynamics and metabolism, with implications for human and animal health. PLoS Genet, 13(4), e1006597. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durmaz B, Wollnik B, Cogulu O, Li Y, Tekgul H, Hazan F, & Ozkinay F (2009). Pontocerebellar hypoplasia type III (CLAM): extended phenotype and novel molecular findings. J Neurol, 256(3), 416–419. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0094-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Vizarra E, Ferrin G, Perez-Martos A, Fernandez-Silva P, Zeviani M, & Enriquez JA (2010). Isolation of mitochondria for biogenetical studies: An update. Mitochondrion, 10(3), 253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2009.12.148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez M, Falk MJ, Gai X, Postrel R, Schule R, & Zuchner S (2015). Innovative genomic collaboration using the GENESIS (GEM.app) platform. Hum Mutat, 36(10), 950–956. doi: 10.1002/humu.22836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haitina T, Lindblom J, Renstrom T, & Fredriksson R (2006). Fourteen novel human members of mitochondrial solute carrier family 25 (SLC25) widely expressed in the central nervous system. Genomics, 88(6), 779–790. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harner M, Korner C, Walther D, Mokranjac D, Kaesmacher J, Welsch U, … Neupert W (2011). The mitochondrial contact site complex, a determinant of mitochondrial architecture. EMBO J, 30(21), 4356–4370. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppins S, Horner J, Song C, McCaffery JM, & Nunnari J (2009). Mitochondrial outer and inner membrane fusion requires a modified carrier protein. J Cell Biol, 184(4), 569–581. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janer A, Prudent J, Paupe V, Fahiminiya S, Majewski J, Sgarioto N, … Shoubridge EA (2016). SLC25A46 is required for mitochondrial lipid homeostasis and cristae maintenance and is responsible for Leigh syndrome. EMBO Mol Med, 8(9), 1019–1038. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201506159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Peng Y, Hufnagel RB, Hu YC, Zhao C, Queme LF, … Huang T (2017). Loss of SLC25A46 causes neurodegeneration by affecting mitochondrial dynamics and energy production in mice. Hum Mol Genet, 26(19), 3776–3791. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen M, Boesten I, Hellebrekers DM, Mulder-den Hartog NM, de Coo IF, Smeets HJ, & Gerards M (2017). Novel pathogenic SLC25A46 splice-site mutation causes an optic atrophy spectrum disorder. Clin Genet, 91(1), 121–125. doi: 10.1111/cge.12774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nury H, Dahout-Gonzalez C, Trezeguet V, Lauquin G, Brandolin G, & Pebay-Peyroula E (2005). Structural basis for lipid-mediated interactions between mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier monomers. FEBS Lett, 579(27), 6031–6036. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.09.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri F (2013). The mitochondrial transporter family SLC25: identification, properties and physiopathology. Mol Aspects Med, 34(2–3), 465–484. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri F, & Monne M (2016). Discoveries, metabolic roles and diseases of mitochondrial carriers: A review. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1863(10), 2362–2378. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten DA, Wong J, Khacho M, Soubannier V, Mailloux RJ, Pilon-Larose K, … Slack RS (2014). OPA1-dependent cristae modulation is essential for cellular adaptation to metabolic demand. EMBO J, 33(22), 2676–2691. doi: 10.15252/embj.201488349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson AJ, Kunji ER, & Gross A (2012). Mitochondrial carrier homolog 2 (MTCH2): the recruitment and evolution of a mitochondrial carrier protein to a critical player in apoptosis. Exp Cell Res, 318(11), 1316–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadedin SP, Dashnow H, James PA, Bahlo M, Bauer DC, Lonie A, … Thorne NP (2015). Cpipe: a shared variant detection pipeline designed for diagnostic settings. Genome Med, 7(1), 68. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0191-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesaki H, & Jensen RE (2001). UGO1 encodes an outer membrane protein required for mitochondrial fusion. J Cell Biol, 152(6), 1123–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesaki H, & Jensen RE (2004). Ugo1p links the Fzo1p and Mgm1p GTPases for mitochondrial fusion. J Biol Chem, 279(27), 28298–28303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401363200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen J, Vashisht AA, Wan J, Jen JC, Claypool SM, Wohlschlegel JA, & Koehler CM (2017). Rapid degradation of mutant SLC25A46 by the ubiquitin-proteasome system results in MFN1/2-mediated hyperfusion of mitochondria. Mol Biol Cell, 28(5), 600–612. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-07-0545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terzenidou ME, Segklia A, Kano T, Papastefanaki F, Karakostas A, Charalambous M, … Douni E (2017). Novel insights into SLC25A46-related pathologies in a genetic mouse model. PLoS Genet, 13(4), e1006656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk T, Rudnik-Schoneborn S, Senderek J, Hajmousa G, Mei H, Dusl M, … Baas F (2017). Pontocerebellar hypoplasia with spinal muscular atrophy (PCH1): identification of SLC25A46 mutations in the original Dutch PCH1 family. Brain, 140(8), e46. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan J, Steffen J, Yourshaw M, Mamsa H, Andersen E, Rudnik-Schoneborn S, … Jen JC (2016). Loss of function of SLC25A46 causes lethal congenital pontocerebellar hypoplasia. Brain. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierenga KJ, Jiang Z, Yang AC, Mulvihill JJ, & Tsinoremas NF (2013). A clinical evaluation tool for SNP arrays, especially for autosomal recessive conditions in offspring of consanguineous parents. Genet Med, 15(5), 354–360. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu-Wai-Man P, Votruba M, Burte F, La Morgia C, Barboni P, & Carelli V (2016). A neurodegenerative perspective on mitochondrial optic neuropathies. Acta Neuropathol, 132(6), 789–806. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1625-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Shi Z, Zhang L, Zhou Z, Zheng X, Liu G, … Zhang YW (2016). Appoptosin interacts with mitochondrial outer-membrane fusion proteins and regulates mitochondrial morphology. J Cell Sci, 129(5), 994–1002. doi: 10.1242/jcs.176792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuchner S, De Jonghe P, Jordanova A, Claeys KG, Guergueltcheva V, Cherninkova S, … Vance JM (2006). Axonal neuropathy with optic atrophy is caused by mutations in mitofusin 2. Ann Neurol, 59(2), 276–281. doi: 10.1002/ana.20797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuchner S, Mersiyanova IV, Muglia M, Bissar-Tadmouri N, Rochelle J, Dadali EL, … Vance JM (2004). Mutations in the mitochondrial GTPase mitofusin 2 cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy type 2A. Nat Genet, 36(5), 449–451. doi: 10.1038/ng1341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.