Abstract

Odor cues and interoceptive cues can combine in promoting drug seeking behavior. Drug discrimination methodology was combined with odor-context conditioning in 8 male and 8 female rats. One drug (nicotine or EtOH) plus odorant (peppermint or anise) compound functioned as setting the occasion for sessions of food-reinforced nose poke responses (i.e., the SD) that were maintained on a variable interval 30 sec schedule (VI-30), whereas the opposite drug (EtOH or nicotine) plus odorant (anise or peppermint) compound predicted intermixed sessions of non-reinforcement of nose poking (i.e., the SΔ). During brief nonreinforcement tests conducted with each condition there was significantly greater responding under the SΔ drug plus odor compound compared to the SΔ drug plus odor compound. Discriminative control was evident and there was a sex by stimulus role interaction with greater SΔ responding in females. The odor contexts and drug contexts alone also sustained strong stimulus control but to a lesser extent compared to the full drug-odor compounds. These data suggest configural learning among drug and odor cues.

1. Introduction

Drug states in animals promote interoceptive changes in the nervous system that can function in directing behavior that is motivated by biologically relevant outcomes (e.g., food, water, shock-escape, and sexual copulation, drug reward) (e.g., Troisi and Akins, 2004). The operant drug discrimination procedure has been a staple behavioral assay in this regard for evaluating “subjective” experience (i.e., interoception) (Troisi, 2013a,b). Previously, this laboratory reported several associative phenomena evident with the discriminative stimulus effects of drugs including: Pavlovian-instrumental transfer (Troisi 2006), feature positive and negative learning (Troisi & Akins, 2004), context renewal (Troisi, 2003b; Troisi & Craig, 2015), configural learning with drug mixtures (Troisi, Dooley, & Craig, 2013); transfer across operants (Troisi, LeMay, & Jarbe, 2010), extinction and spontaneous recovery (Troisi, 2003a,b), reinforcer devaluation (Troisi, Bryant, & Kane, 2012), and modulation of complex operant chains (Troisi, 2013). Of course, exteroceptive contextual stimuli (lights and tones) also function as discriminative stimuli that facilitate voluntary responding (i.e., SD) and/or inhibit responding (i.e., SΔ) in directing behavior-outcome relations noted above (e.g., Troisi, 2013a,b). SD predicts that behavior will lead to reward, whereas SΔ predicts that behavior will not lead to reward.

Exteroceptive and interoceptive stimuli combine to set the occasion for specific response-reinforcer (or non-reinforcer) outcomes (e.g., Troisi, 2013a,b,c). Previously, our laboratory (Troisi and Craig, 2015) used two different exteroceptive contexts with two distinct interoceptive drug states (nicotine and EtOH) that functioned as SD and SΔ response modulators. Within subjects, one distinct exteroceptive context (e.g., strobe light and tone) was compounded with administration of nicotine and functioned as an SD in occasioning reinforcement sessions (VI-30s), whereas, a second exteroceptive context (dim lighting and white noise) was compounded with ethanol administration and functioned as SΔ occasioning non-reinforcement sessions. The drugs and exteroceptive contexts were fully counterbalanced across rats. The context plus drug compounds promoted robust stimulus control with significantly greater responding in the SD condition compared to SΔ condition during multiple nonreinforcement tests. Discrimination indices averaged 98% responding in the SD condition. The interoceptive drug states alone (administered with bright room without noise, strobe, or tone) promoted 80% responding under the SD conditions, whereas the exteroceptive contexts alone (i.e., saline administration) promoted only 73% SD responding. Thus, the full interoceptive-exteroceptive compound gestalt promoted greater stimulus control than the interoceptive and exteroceptive contexts alone. The present investigation continued this line of research with two distinct olfactory contexts (peppermint or anise) that were compounded with either nicotine or EtOH interoceptive SD and SΔ. As in our prior investigation, the two drugs and two olfactory contexts were fully counterbalanced across animals for their SD and SΔ roles. An added feature of this investigation was the potential sex differences as olfactory sensitivity and hormonal differences have been reported (e.g., Kunkhyen, Perez, Bass, Coynea, Baum, & Cherry, 2018; Pietras & Moulton, 1974). Moreover, the reinforcing and subjective effects of several drugs of abuse vary across the estrous cycle (Lynch, Roth, & Carroll, 2002). It should be noted here, that estrous phase was not an independent variable in the present investigation. Invariably, multiple interoceptive and exteroceptive stimuli combine to guide drug-maintained behavior (Troisi, 2013). The present investigation evaluated the combined effects of drug interoceptive states with exteroceptive olfactory contexts. Stimulus control among the full drug-odor gestalts was tested along with just the two drugs and odors alone. Based on our previous work, it was predicted that the full drug-odor compounds would promote stronger stimulus control than either the drugs or odors alone.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

16 experimentally 90 day old naïve Sprague Dawley rats (8 male and 8 female) (Envigo Breeders, Frederick, MD) were maintained at 80% of their free-feeding weights (females 250–275; males 300–330 gm). 15g was added every week for growth. Rats were housed individually in hanging cages in the vivarium with ad-lib access to water and were maintained on 12 hour light-dark cycle (7:00 am to 7:00 pm – light phase) but received daily socialization in environmental enrichment. Daily temperature averaged approximately 21C.; relative humidity averaged 60%. Animals were used in accord the ethical guidelines of the Saint Anselm College Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Psychology Department, and the PHS Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2. Apparatus

Sessions took place in eight operant chambers (Med-Associates ENV-01; L 28 × W 21 × H 21 cm), equipped a food magazine centrally located on the front panel of the chamber measuring (H 5 × W 5 × D 3 cm), which delivered 45 mg standard grain-based food pellets (BioServe, Frenchtown, NJ). Levers were removed, but a nose-poke response device (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT model ENV 114 BM) was installed in each chamber and was located 2 cm above the gridded floor mounted in the rear end of the clear acrylic wall left of the food magazine. The chambers were placed two - three feet apart and located about the perimeter of the sound and light attenuated experimental room (L 16.5 × W 9 feet) designed for an undergraduate Psychology courses related to behavioral biology and animal learning and motivation. Two 25 watt red lights illuminated the room during session-time and were terminated at the end of each session by overhead track-light room-lighting. A white noise source was delivered by an antenna-less and cable-free television, which was turned on at the start of each session and co-terminated with illumination by the overhead lighting, which was also turned on and off manually. Experimental events were programmed via Med-PC Software (Version 2.08) and by a DIG interface (Med-Associates, St. Albans, VT) to an IBM 386 in an adjacent monitoring room.

2.3. Drugs & Drug Administration

13.2 ml of ethanol (95% stock) was diluted in 100 ml solution of 10% 10-X phosphate buffered saline to sustain a pH of 7.0. The solution was delivered in a volume of 10 ml/Kg, delivering a dose of 1.0 g/Kg. (−)-nicotine hydrogentartrite (Sigma) (0.3 mg/Kg; base) was dissolved in saline and administered in the same volume as EtOH. These doses (and preparations) were selected based on past work in this lab with these doses that show equisalience (Troisi, 2013; Troisi and Craig, 2015; Troisi, Dooley, and Craig, 2013). Approximately ten minutes prior to the 20-min discrimination training session, rats received intraperitoneal injections of either nicotine or ethanol.

2.4. Procedure

Magazine training took place on the first day, with the nose-poke devices covered with stainless steel plates. On the second day, nose-poking was established with little training; it was initially maintained on an FR-1, but was abruptly switched and maintained on a VI-30 sec schedule of food reinforcement for 5 sessions. Drug discrimination training took place over the next 24 sessions. 2 ml McKormick’s peppermint or anise extract was poured in a 20 ml scintillation vial cap that was located under the grid floor in the middle of the chamber. Only one odor was presented on each day, but half the rats received nicotine (n=8) and the other half (n=8) received EtOH on a given session. Table 1 outlines the drugodor and stimulus role assignments for all rats.

Table 1.

| male | (n=2) | NP+ | EA-; | male | (n=2) | NP- | EA+ |

| male | (n=2) | NA+ | EP-; | male | (n=2) | NA- | EP+ |

| fem | (n=2) | NP+ | EA-; | fem | (n=2) | NP- | EA+ |

| fem | (n=2) | NA+ | EP-; | fem | (n=2) | NA- | EP+ |

Drug and odor condition assignments for males (n=8) (top) and females (n=8) (bottom). N is nicotine, E is ethanol, P is peppermint, and A is anise. Plus and minus signs refer to the SD and SΔconditions, respectively.

For 4 rats in the nicotine session nose-pokes were reinforced on a VI-30 schedule, but for the remaining four rats nose-poking was without consequence. For those same animals, the EtOH and the odor roles were reversed. Thus, drug-odor compound conditions and reinforcement/non-reinforcement sessions were counterbalanced across rats. Daily sessions were 20-min. 24 sessions alternated with no more than two consecutive presentations of one condition and there were 12 sessions of each condition. Full drug plus odor compound test sessions were 3-min, and were conducted just prior to each of the last four 20-min training sessions: two with nicotine with its associated context and two with ethanol in the opposite odor context. During those 3-min test probes, food was not dispensed but nose-poking was recorded under both conditions. Two additional training sessions followed, one with the SD drug plus odor compound and one with the opposite drug plus odor compound SΔ. The SD and SΔ odors alone were then tested for stimulus control with two counterbalanced 3-min non-reinforcement tests conducted over two days, one with peppermint and the other with anise. On these days, saline was administered 10 min prior to the test session. Two additional training sessions followed. The final two tests evaluated just the drug states without the odor background, one with nicotine and one with ethanol; these sessions were conducted without odors present.

3. Results

3.1. Drug plus odor compound tests

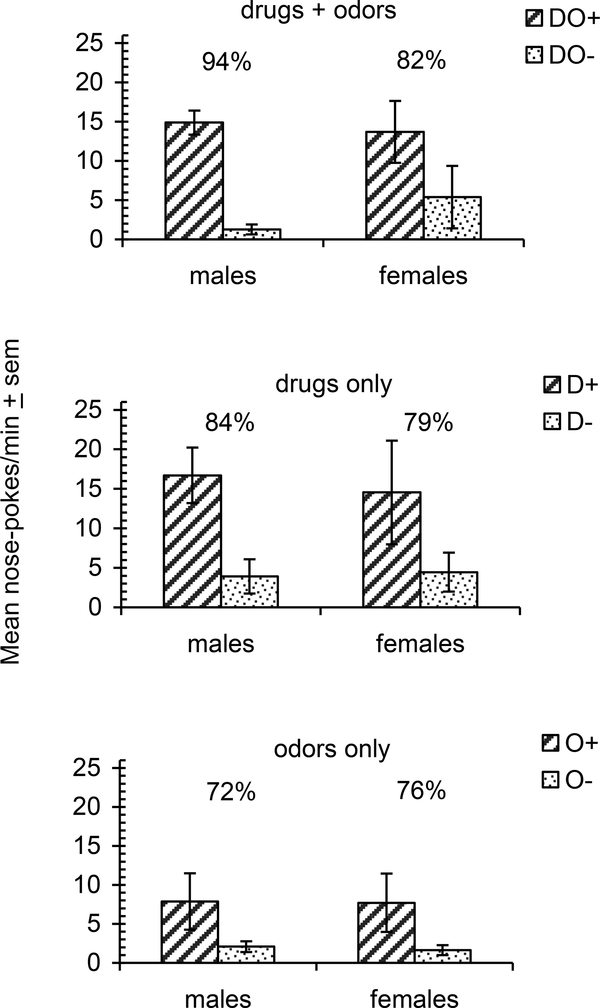

After the 24 training sessions (data not displayed) a 2 (sex; between group) X 2 (SD and SΔ, within group conditions) repeated measures ANOVA was conducted on the test data. Data were averaged across SD and SΔ conditions for odors-drugs for males and females and revealed compelling stimulus control by the 2 full odor-drug compound conditions with significantly greater response rates in the SD compound compared to the SΔ compound [F(1,14) = 111.97; p ≤ .001; ηp= .94]. There was no significant sex difference; however, there was sex by drug (SD vs. SΔ) interaction [F(1,14) = 6.57; p = .023; ηp = .57 ] with females showing elevated SΔ (inhibitory) responding relative to males (Fig 1, top graph). The mean discrimination index [SD responses/( SD + SΔ responses) *100] for the females (82%) was significantly lower than for the males (94%) [t(14) = 2.18; p = .048; Cohen’s d = (0.82 – 0.94) ⁄ 0.1113 = 1.078].

Figure 1.

Mean rates of nose poking during 3-min non-reinforcement tests following drug discrimination training with a drug plus odor (DO) for male (n=8) and female (n=8) rats. For four rats (2 male and 2 female), nicotine + anise functioned as SD and occasioned 20-min sessions of food-reinforcement maintained on a VI-30 s schedule; EtOH + peppermint functioned SΔ and predicted sessions of non-reinforcement. For 4 other rats the stimulus roles of nicotine and EtOH were reversed. For the remaining 8 rats, the roles of the odors were reversed allowing complete counterbalance across all rats. Data are collapsed across SD (+) and SΔ(−) drugs and odors. The top graph illustrates responding with the full drug-odor compound (DO). The middle graph illustrates responding with the drug alone (D) and the bottom graph illustrates responding with the odors alone (O). Plus and minus signs indicate SD and SΔ conditions, respectively. Discrimination indices [SD /( SD + SΔ responses)] * 100 are presented as percent SD responses and are displayed above each pair of bars.

3.2. Drug SD vs. SΔ tests

Figure 1 (middle) displays the results of the tests conducted under the SD and SΔ drug conditions. A 2 (sex) × 2 (drugs SD vs. SΔ) repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect for SD vs. SΔ with significantly greater response rates under the SD compared to the SΔ condition [F(1,14) = 16.81; p =.001; ηp = .74]. There was no significant difference for sex nor was there a significant sex by drugs interaction. Discrimination indices did not significantly differ across sexes.

3.3. Odors SD vs. SΔ tests

A 2 (sex) X 2 (odors SD vs. SΔ) repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect for the SD vs. SΔ odor conditions with significantly greater response rates in the SD odor compared to the SΔ odor conditions [F(1,14) = 5.54; p = .034; ηp = .53]; there was no significant difference for sex nor was there a significant sex by drugs interaction. Discrimination indices analyzed by independent t-test, did not significantly differ across sexes (Fig 1, bottom).

4. Discussion

The present study evaluated sex differences in the discriminative stimulus effects of drug and odor cues. It is the first to compare sex differences regarding the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine in rats. The drug cues and odor cues promoted the greatest stimulus control with less control exerted by either the drug or odors alone. These data suggest that stimulus control by two distinct drugs can combine in compound with the stimulus control mediated by two olfactory contexts. To be sure, the drug-olfactory compounds maintained the most stimulus control overall. There was somewhat less control exerted by the drugs or odors alone, as discrimination indices were markedly lower than the full odor-drug compounds. These data A) suggest configural learning among drug plus odor compounds – the whole compound was “perceived” differently than the elements, and B) corroborate our prior nicotine/EtOH drug discrimination work with exteroceptive audio-visual contexts (Troisi & Craig, 2015)

The lack of a sex difference in the odor discrimination alone may reflect stimulus salience; it is plausible that the odors were perhaps too salient to show sex differentiation. Lowering the concentrations of the odor cues is clearly warranted for further evaluation. On balance, it is plausible that odor pheromones affected discriminative performance; however, males showed less variability than the females. Alternatively females may be more sensitive to pheromone variation at different phases of the estrous cycle. These possible contributing factors deserve research attention, but are unknown based on the present data. More interestingly, was the sex by drug condition interaction found with the full drug-odor compounds. Females showed elevated SΔ responding and there was far more variability in response rates compared to the males; in relation to this, the males exhibited greater stimulus control with the full odor-drug compounds than the females, although SD responding overall promoted similar response rates. This reflects how inhibition of responding in the SΔ condition fosters discriminative control (Troisi et al., 2010). At this time, it is not clear why the females exhibited elevation in SΔ responding; however, it is plausible that estrous cycle phase contributed, as estrodial has been shown to affect discriminative performance of odors in mice (e.g., Kunkheyn et al., 2018). Of course there is abundant literature outlining sex differences in the reinforcing effects of nicotine in rats (e.g., Chaudhri, Caggiula, Donny, Booth, Gharib, Craven, & ... Perkins, 2005) and other drugs (Becker, 1999; Becker & Hu, 2008; Hu & Becker, 2003; Hu, Crombag, Robinson, & Becker, 2004) but to our knowledge this is the first evaluation of sex differences pertaining to the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine. We are currently evaluating differences in dose response as a function of estrous phase.

On a clinical/translational level, multiple sensory cues precede and enter into drugseeking and drug taking rituals (Troisi, 2012, 2013c). Here, it was shown how olfactory cues combine with drug interoceptive cues and form a unique cue that functions to modulate goal-directed behavior in predicting primary reward. Prior work in our lab (Troisi et al., 2013; Troisi & Craig, 2015) demonstrated that extinction training with the elementary components within the compound did not undermine stimulus control with the full compounds. A future systematic replication of the present study should extinguish responding with the odors and drugs separately, and then test responding with the full odor-drug SD and SΔ compounds. Olfactory cues have been shown to promote drug craving and seeking, particularly those directly associated with reward. We are currently involved in this evaluation.

Highlights.

rats learned a drug by odor context discrimination

females exhibited elevated Sdelta responding

the drug-odor compounds promoted robust stimulus control

odors and drugs alone promoted less stimulus control

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by New Hampshire IDeA Network of Biological Research Excellence (NH-INBRE) NIH Grant Number No. P20GM103506 from the INBRE Program of the National Center for Research Resources. These data were previously presented at the Annual Meeting of the Behavioral Pharmacology Society, San Diego, CA, April, 2018. Thank you to Samantha Cuomo for data collection. The author would like to extend a thank you to one reviewer who raised some pertinent questions that are outline in the discussion section. A special thanks go to Sam Dahlberg, for diligent animal husbandry.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Becker JB (1999). Gender differences in dopaminergic function in striatum and nucleus accumbens. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, 64(4), 803–812. doi:10.1016/S0091-3057(99)00168-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhri N, Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Booth S, Gharib MA, Craven LA, & ... Perkins KA (2005). Sex differences in the contribution of nicotine and nonpharmacological stimuli to nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology, 180(2), 258–266. doi:10.1007/s00213-005-2152-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, & Becker JB (2003). Effects of Sex and Estrogen on Behavioral Sensitization to Cocaine in Rats. The Journal of Neuroscience, 23(2), 693–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkheyn T, Perez E, Bass M, Coyne A, Baum MJ, & Cherry JA (2018). Gonadal hormones, but not sex, affect acquisition and maintenance of a go/no-go odor discrimination task in mice. Hormones and Behavior, 100, 12–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WJ, Roth ME, & Carroll ME (2002). Biological basis of sex differences in drug abuse: preclinical and clinical studies. Psychopharmacology, 164(2), 121–137. DOI 10.1007/s00213-002-1183-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietras RJ & Moulton DG (1974). Hormonal influences on odor detection in rats: changes associated with the estrous cycle, pseudopregnancy, ovariectomy, and administration of testosterone propionate. Physiology & Behavior, 12, 475–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR II (2003a). Spontaneous recovery during, but not following, extinction of the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine in rats: Reinstatement of stimulus control. The Psychological Record, 53, 579–592. [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR II. (2003b). Nicotine vs. ethanol discrimination: Extinction and spontaneous recovery of responding. Integrative Physiological Behavioral Sciences, 38, 104–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR II (2006). Pavlovian-Instrumental transfer of the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine and alcohol. The Psychological Record, 56, 499–512. [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR II (2011). Pavlovian extinction of the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine and ethanol in rats varies as a function of the context. The Psychological Record, 61, 199–212. [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR II (2013a). The Pavlovian vs. operant interoceptive stimulus effects of EtOH: Commentary on Besheer, Fisher, & Durant (2012), Alcohol, 47 (6) 433–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR (2013b). Acquisition, extinction, recovery, and reversal of different response sequences under conditional control by nicotine in rats. Journal of General Psychology, 140(3), 187–203. doi:10.1080/00221309.2013.785929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JI (2013c). Perhaps more consideration of Pavlovian–operant interaction may improve the clinical efficacy of behaviorally based drug treatment programs. The Psychological Record, 63(4), 863–894. doi:10.11133/j.tpr.2013.63.4.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR II, & Akins C (2004). The Discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine in a Pavlovian sexual approach paradigm in male Japanese quail. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 12, 237–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR II, & Craig EM (2015). Configurations of the interoceptive discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol and nicotine with two different exteroceptive contexts in rats: Extinction & recovery. Behavioural Processes, 115, 169–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR II, Dooley TF II, & Craig EM (2013). The discriminative stimulus effects of a nicotine-ethanol compound in rats: Extinction with the parts differs from the whole. Behavioral Neuroscience, 127(6), 899–912. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0034824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR II, LeMay B, & Jarbe TUC (2010). Transfer to the discriminative stimulus effects of Δ9-THC and nicotine from one operant to another in rats. Psychopharmacology, 212, 171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]