Abstract

It is well recognized that, despite similar pain characteristics, some people with chronic pain recover, whereas others do not. In this review, we discuss possible contributions and interactions of biological, social, and psychological perturbations that underlie the evolution of treatment-resistant chronic pain. Behavior and brain are intimately implicated in the production and maintenance of perception. Our understandings of potential mechanisms that produce or exacerbate persistent pain remain relatively unclear. We provide an overview of these interactions and how differences in relative contribution of dimensions such as stress, age, genetics, environment, and immune responsivity may produce different risk profiles for disease development, pain severity and chronicity. We propose the concept of ‘stickiness’ as a soubriquet for capturing the multiple influences on the persistence of pain and pain behavior, and their stubborn resistance to therapeutic intervention. We then focus on the neurobiology of reward and aversion to address how alterations in synaptic complexity, neural networks and systems (e.g., opioidergic and dopaminergic) may contribute to pain stickiness. Finally, we propose an integration of the neurobiological with what is known about environmental and social demands on pain behavior and explore treatment approaches based on the nature of the individual’s vulnerability to or protection from allostatic load.

Introduction

What are the factors that determine why, following a similar insult, some people experience pain that resolves while in others it persists? An analysis of this question requires the ability to define chronic pain in such a way that it can be distinguished mechanistically from acute pain - pain that abates naturally following injury. We need an approach to understanding why, in the context of similar physical insult, some individuals develop chronic pain, while others experience limited or rapidly resolving pain. Historically, chronic pain has been defined in terms of its duration: this definition does not allow for a consideration of mechanism. Thus, in some patients, eliminating the causative insult, or modifying the process with effective treatment, even after years of pain, leads to pain resolution. In others, there appears over time a dissociation of the causative insult and the continued pain, and/or a resistance to therapies that may have initially been quite effective.

While significant numbers of individuals suffer from chronic pain, reportedly over 100 million in the US alone [122], a more careful analysis suggests that fewer have daily pain (some 25 million in the US), and fewer still have severe pain (14 million in the US) [196]. The number of people with persistent pain who are unresponsive to treatment are not easily determined nor reported in large epidemiological studies. But treatment failure is high at the level of the trial, so is likely to be worse in the clinic. Treatment failure is inferred from data derived from controlled trials (e.g., for gabapentin and neuropathic pain) where the treatment can provide relief as high as 50% of pain intensity in comparison with placebo, normally expressed in terms of the mean [191]. Arguably, the high burden of pain in the population and limited treatment options have meant that more radical treatments are being proposed, including ketamine infusions [182], and deep [24] or transcranial [157] brain stimulation, all offered to patients with pain described as treatment-resistant. The picture is one of a large population of people with treatment-resistant, complex, burdensome pain for which we struggle to find viable long-term analgesic or pain management options.

In this paper we propose the concept of ‘stickiness’ as a soubriquet for capturing the multiple influences on the persistence of pain and pain behavior, and their stubborn resistance to therapeutic intervention. Our ultimate goal, perhaps a goal of the whole field of pain research, is to develop a fully integrated bio-behavioral model. However, this first step toward that goal is a neurobiological one. We explore the idea of pain stickiness in the following sections: (1) In the section on Perturbations of Biological Systems and the Development of Chronic Pain we evaluate the idea of how an event or perturbation (e.g., surgery) may induce changes in a system to which there is a response that may be adaptive or maladaptive (through numerous influences) and which may result in chronic pain as a result of changes in behavior; (2) The section that follows, entitled Pain Stickiness: Clinical Insights, we provide examples of pain chronification where pain load, as defined by intensity and duration may produce a more resistant pain state less easily modified or affected by therapeutic interventions; (3) The third section provides an overview of elements that contribute to our understanding of Neurobiology of Pain Stickiness including synaptic plasticity, stress, brain circuits, endogenous regulators (namely opioidergic and dopaminergic) that may contribute to the ‘stuck’ pain state (i.e., non-responders); In the final section (4) Pain Unstuck: Potential Research Targets we focus on potential novel therapeutics arising from this approach.

Perturbations of Biological Systems and the Development of Chronic Pain

Systems biology, including the neurobiology of chronic pain, starts from the premise of expected complexity and relegates most of this intricacy to error variance. We start with the assumption that it is theoretically possible for all people to develop chronic pain. In practice, however, not everyone does develop chronic pain. For a perturbation such as nerve damage following surgery, for example, some 15–50% of patients may have pain, of whom 10–15% experience severe, unremitting pain. What differentiates responses to the same perturbation? Perturbations may take place at genetic [272], cellular [86] [140], neuronal, whole brain systems [37], and at psychological [75] levels. This is represented in the field of “Network Biology” [12] [114] that can model complex behaviors. Modeling of such a multifactorial entity as pain may be thus substantially aided by its conceptualization as a computable network. Through increased understanding of biological systems and the application of computational methods, our ability to model a complex process such as chronic pain is becoming more likely. In doing so, systems can be simulated with adaptive and maladaptive functional properties defined. It should be noted that perturbations may induce regulatory networks that include inhibition/repression or stimulation/expression of multiple processes. This is reflected in chronic pain as perturbations that contribute to protection from perturbation, and resilience to prolonged disruption.

Reaction to injury or the threat of injury is characterized by the attempts of the organism to return or maintain homeostasis. This reaction can turn into action (without external reference) and ‘overrun’, creating a state of allostasis which may prevail where normal adaptations to pain are not working [32]. The behavioral response, whether to pain induced by peripheral nerve damage (e.g., surgery), spinal cord damage, alterations in the brain itself (depression, thalamic stroke), or through repetitive avoidance or endurance behavior [54,55], results in alterations of a normal ecosystem that involve brain connections. The latter, termed the connectome, defines our behavioral state including that in acute and chronic pain [153].

We are interested in adaptive systems, in the ability to repeatedly respond to a stressor such as persistent pain in ways that produce consistent outcomes. Behavioral response to stress is commonly called ‘coping’ [263], but this is sometimes poorly defined, conflating behavior with outcome [240]. Here we are interested in the elastic property of the system to return the organism to homeostasis, and in this regard choose to describe that property as a form of ‘resilience’. There are many ways to consider resilience in the context of pain or the threat of pain, including the cognitive [205], emotional [89] [133], genetic [91], and epigenetic [72].

Cognitive-affective Influences

Coping with chronic pain is often associated with the ability to re-cast a problem in a broader frame of possible solutions, in which worry promotes problem solving rather than rumination [70] [60] [78];[76] Less explored is the fate of pain interruption, and by extension the capturing of motivational systems by pain [193]; [55]; [7]. Multidimensional psychological constructs of the affective interpretation of pain have been widely explored. Fear and avoidance behavior are implicated in repetitive chronic pain behavior, [264] [136] [54] [249] at least in patients presenting with chronic pain, as is the appraisal of pain and its consequences as unavoidably catastrophic [243] [273]. Attempts to characterize successful coping behavior as a property of a system’s resilience are hampered by a conceptual circularity inherent in clinical observational studies that focus on measuring observable outcomes. We are confident, however, that the salience of the affective tone of interruption is a crucial component in the system’s response to threat [75].

Demographic/Socioeconomic Influences on Chronic Pain

Social and demographic factors, including sex, gender, age, marital status, family relations or socioeconomic status (SES) are all important elements of the context for pain experience [2] [201]. Effects of SES on pain are reported for other common pain conditions such as headache [178] or chronic pain following a motor vehicle accident [265]. In addition to the more well defined biological factors, the multitude of influences on an individual’s pain, as noted in this paper, are complex and also include socioeconomic (poverty, access to health care including affordability of medications, occupation type), demographic (e.g., age, sex, education) and pain specific factors (e.g., surgical treatment outcomes). For example, “Lower individual and community SES are both associated with worse function and pain among adults with knee rheumatoid arthritis” [47]. In a consideration of allostasis, poor socioeconomic status could contribute to increased pain [241]. As such, the effects of poverty are associated with increased allostatic load [227], the accumulation of stressors threatening physiological homeostasis. The processes contributing to allostatic load can add to the burden of health status through the maladaptive responses to chronic stress imposed by SES [141].

Allostasis (see below) may contribute to socioeconomic load of chronic pain as well as to disease comorbidity associated with chronic pain. With respect to the first, allostatic load may influence patterns of pain prevalence [241]. In addition, many countries are seeing a relative aging of the population. In the US, for example, the number of Americans older than 65 years has increased steadily owing to the rise in life expectancy and is projected to encompass one fifth of the population within the next 20 years [85]; [50]. These patients are naturally at a heightened risk of co-morbid conditions as 50% of community-dwelling elderly people and 80% of nursing home residents are suffering from chronic pain [109].

In the context of comorbidity, allostasis has been considered a concept that may link comorbid conditions [152]; [206]. Comorbidity in chronic pain has been reported for multiple conditions [56] including anxiety and depression [58], alcohol use disorder [279], post-traumatic stress disorder [166], pain sensitivity in opioid dependent patients [284], and bipolar disorders [65]. For the comorbidity of pain and psychiatric disorders [269] such as comorbid anxiety, research supports the notion of increased pain levels [97], chronification [244] and lower treatment efficacy [239]. The notion of how psychiatric disorders may contribute to pain chronification has been reviewed previously [31]. Comorbidity focuses on the interesting phenomenon changes in the brain, in pain, in depression and in addiction [82]. For example, in patients with major depressive disorder without a history of prior pain, some 60% present with a generalized pain disorder [132].

Genetics – Predisposition and Resilience

Genetic contributions to resilience or vulnerability may be considered in a number of domains: (1) Genes that moderate the non-inflammatory stress response. Ongoing high levels of corticosteroids have been associated with chronic pain [186] [268]. Genes, including FKBP5 and CRHR1 polymorphisms, have been shown to modulate or modify the response of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis [161]. These genes may shape responses to early life experience (e.g., risk of PTSD after child abuse [21]) or to new stressors such as a motor vehicle accident or sexual assault [33]. (2) Genes that sensitize the nervous system to potentially develop chronic pain. A number of genes may contribute to pain severity [277]: specific alleles have been associated with an increased risk for post-surgical pain severity and persistence [259]. Specifically, patients with chronic low back pain expressing a haplotype of the GCH1 gene had less neuropathic pain following discectomy. Other examples of genes showing an association with chronic pain states include an amino acid-changing allele in KCNS1 [52] and genes associated with certain types of headaches including migraine [61] [36]. Taken together, the genetic susceptibility to chronic pain [200] [128] contriubtes not only to an increased risk of pain but also may provide insights into treatment resistance and chronification. (3) Genes that may alter the immune response. Neuroinflammation seems to be a common process involved in chronic pain [169]. Genes that regulate the immune response may contribute to resilience or susceptibility to disease. The modulatory effects of neuroinflammation may be activated by a disease state such as nerve damage [81] [190] or even by adverse social conditions [48]. Resilience to neuroinflammation may itself be a protective mechanism in disease [173]. For example, a T-cell shift present in neuropathic pain may represent a protective, anti-inflammatory process [170].

Epigenetic Factors – Non-Genetic Modification of Biological Responses

Biological processes are regulated by epigenetic processes that may confer vulnerability [72] [285]. Epigenetic processes take place through DNA methylation of genes (including stress response genes) that may alter resilience to environmental stressors. The term epigenetics refers to processes that contribute to altered gene expression through non-genetic mechanisms, and these processes may have significant effects on pain. Thus epigenetic factors may contribute to pain behaviors and to the likelihood of pain becoming stuck [63]. The implications of epigenetic changes are only just becoming known, and include changes in memory for pain [213], changes in anxiety and pain [262], hyperalgesia [164] pain exacerbation [103], the persistence of pain [10], vulnerability to pain [62], and analgesic response [160]; [107].

Allostatic Load and Maintenance of the Chronic Pain State

Multiple systems are involved in protecting an organism from rigidity and adaptation failure. Puterman’s concept of “multisystem resiliency” captures a number of factors involved in resisting the development of chronic pain and ameliorating suffering [211]. Allostatic load may further contribute to the efficient return to homeostasis [184]. Such perturbations may either prevent or allow for the exacerbation (chronification, resistance to treatment, intensity, comorbidity) of pain. An individual’s prior and current bio-psycho-social state may be important elements in the chronification and persistence of pain or may limit this process. In the next section we discuss clinical examples of this process.

Pain Stickiness: Clinical Insights

Most people who experience an episode of acute pain caused by deliberate, accidental, or disease related trauma do not develop chronic pain. For those who do, the extent of pain, disability and distress are highly variable ─ some pain syndromes are more severe and more permanent than others. Perhaps, central neuropathic pain syndromes associated with stroke or spinal cord damage [150] [39] are examples of chronic pain that rarely, if ever, resolve. For those individuals in whom pain and maladaptive coping become rigidly fixed or ‘stuck’, a number of factors seem to contribute to this rigidity. Below we give a few clinical examples of increased or decreased ‘pain stickiness’.

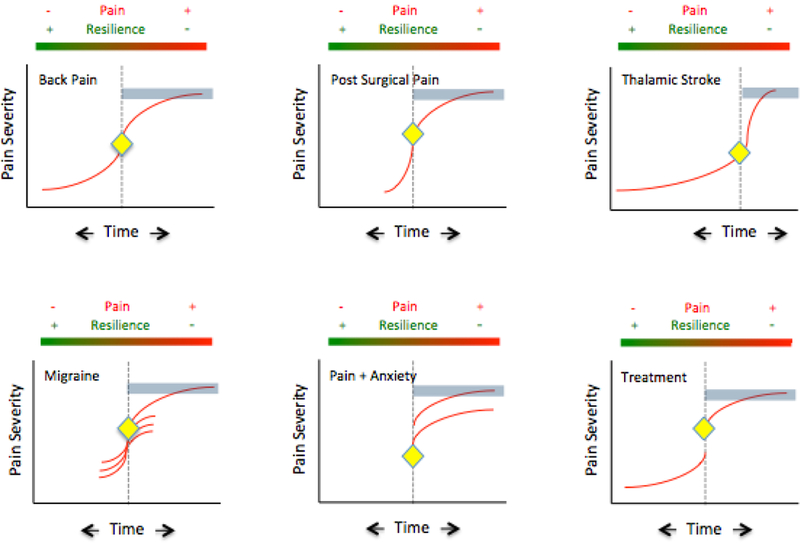

In Figure 1, we represent the idea of pain evolving and persisting, remaining static, or worsening. In the schematic model, the blue portion beyond the inflection point (diamond) suggests a time where pain either persists or worsens as opposed to reversal (sliding back along the pain trajectory). Pain may not always worsen when it chronifies: some people with postoperative pain, or with pain from other (usually traumatic) causes, describe pain onset at a severe level that never eases or worsens. Clinical examples of pain stickiness are encompassed by the delayed onset and offset of pain following two neuropathic pain syndromes: following stroke affecting the sensory thalamus (i.e., ventroposterolateral) there is a variable time for onset of pain [158]; following post herpetic neuralgia, time to offset of pain was reported as up to 120 months [130]. Another example is in migraine chronification where episodic migraine (≥14 migraine days per month) increases in frequency to become chronic migraine (≥ 14 migraine days per month). The transformation may be progressive or acute as in new daily persistent headache [222]. Chronic migraine is more resistant to treatment. Both the neuropathic and migraine examples speak to processes that relate to nervous system adaptation and resilience.

Figure 1: Chronic Pain Syndromes that get ‘Stuck’.

In Figure 1, we represent the idea of pain evolving and persisting, remaining static, or worsening.

Back Pain: Back pain may start as an acute process and get better or it may worsen and chronify. Eighty percent of adults will have back pain at some point, and most resolve. Twenty percent however go on to have chronic pain for more than a year. Risk factors, like many but not all pain conditions that relate to disease resilience in back pain include age, fitness, pregnancy, weight, genetics, anxiety/depression [1]. In its ‘stuck’ form, it is difficult to treat and the ongoing pain and disability continue to contribute to the allostatic load of the condition and its treatment resistance.

Post-Surgical Pain: Surgery may produce damage to nerves resulting in neuropathic pain and occurs in 15–50% of patients [144] [174] [30]. Risk factors include genetic [286], pre-operative pain [108], acute post-operative pain [35], psychosocial factors such as catastrophizing [126]; surgical stress [30] and potentially perioperative treatments including intraoperative opioids that may induces post-operative hyperalgesia [146] [281] [98]. It may be more common after certain surgeries (e.g., surgery for failed back; limb amputation, mastectomy) and some surgeries may have a higher incidence because of the location of the surgery relative to certain nerves (e.g., intercostal n., intervertebral n., ilio-hypogastric n., divisions of the sciatic n.). Taken together, these multifactorial processes may contribute individually or in various combinations to a chronic pain syndrome that may be persistent and severe.

Thalamic Stroke: Few pain syndromes are as severe and persistent as the pain following thalamic (usually right sided) stroke [25] that involves the spinothalamic tract. It affects some 8% of stroke patients [5]. While the onset may be days to months after the stroke [34], it represents a forme fruste of a ‘stuck’ pain syndrome and as shown in the figure the pain intensity with onset may be progressive but usually ramps up to a very severe level. The syndrome has no socioeconomic variability, age, or sex predisposition. Other syndromes that result in severe and persistent pain also produce damage the spinothalamic tract and include spinal cord injury [179]. The figure shows a timeline vs. intensity that summarizes the process in which patients may not have pain or have relatively rapid onset, in most cases, of this severe central pain syndrome.

Migraine: Migraine is an example of a pain syndrome (that is intermittent (acute episodic migraine) that can increase in frequency and chronify [168] [143]. In the acute episodic form (≥ 14 headache days a month; International Headache Society Definition: [245], the pain and associated symptoms of the pre-, peri- and post- ictal event are acute and subside completely. In chronic migraine the pain persists (≤ 14 headache days a month; International Headache Society Definition: [245]. Some 6–8 million American suffer from chronic migraine [178]. Migraine chronification may be considered to be due to increasing allostatic load [32] and medication overuse [19], increased frequency of headache, menstrual cycle amongst other things contribute to the maladaptive changes in the transition from acute episodic migraine to chronic migraine. Interestingly some data supports a reversal of the chronic state with the withdrawal of certain stressors such as opioid medication [234]. The figure shows two forms of migraine – acute intermittent migraines (multiple attacks) are present. In the acute form there is an intermitted attack that recedes, usually with hours but may last up to 72 hours. In the chronic form pain is present most of the time.

Pain+Anxiety: The notion that psychological processes (e.g., fear, avoidance, anhedonia) can affect chronic pain either as a predictor [208] because of a particular constitutional makeup or as an exacerbator of the pain condition [253] is depicted in the figure.

Treatment: Treatment for chronic pain is a double-edged sword in that drugs are frequently given for a long period of time without an understanding of their long-term effects on neural or other systems. In chronic pain, the field has embraced the notion of such concepts as ‘opioid induced hyperalgesia’ that may reflect the induction of aberrant neural systems to produce increased ongoing pain [46] and perhaps increased resistance to treatment [18]. Indeed chronic opioids alter morphological and functional measures in patients without pain [267]. Similarly and perhaps more notable, are the effects of medications including specific anti-migraine drugs called triptans, on migraine progression (increased frequency) and chronification (transformed from acute episodic to chronic) [18] [167].

Key:

Represents the onset/event of the pain and the point from which it may improve or get worse.

Represents the onset/event of the pain and the point from which it may improve or get worse.

Represents when pain is severe and resilient to treatment and/or chronifying.

Represents when pain is severe and resilient to treatment and/or chronifying.

Is time from the Onset/Event

Is time from the Onset/Event

Is a scale of increasing or decreasing Pain as it relates to the level of Resilience.

Is a scale of increasing or decreasing Pain as it relates to the level of Resilience.

Analgesic Efficacy and Pain Stickiness?

Most analgesics have an NNT for 50% pain relief in chronic pain of between 3–10, and the superior effect of the primary drug over placebo is in the region of 30% [192]. In essence the majority of people treated with pharmacological interventions do not experience the desired effect [191]. It is, however, well known that pain relief has a binomial or U-shaped distribution, meaning that describing a sample by its mean score is to choose the experience of the least number of people [191]. It is better to think more carefully about who responds and why. One reason for the ineffectiveness may relate to how drugs, when used chronically, may enhance pain. While mechanisms are not fully understood, one example is chronic opioid use associated with increased DNA methylation and increased levels of clinical pain [69]. It should be noted however, that some of these data should be assessed in the context of duration of treatment; for example, for opioid effects on chronic pain, the longest randomized controlled trial (RCT) is only 16 weeks [45].

Drugs change the brain!

Medications may contribute to pain chronification. In the migraine field the misuse of triptans, opioids, barbiturates, and NSAIDS seems to induce migraine chronification [20]; [42]; [127]. Interestingly in many patients, chronification (transformed migraine) is reversed with drug withdrawal or decreased (i.e., from chronic to episodic migraine [112]. With chronic pain characterized as ‘opioid induced hyperalgesia’ [280], often of rapid onset [98], the opioid may actually be contributing to or be part of chronification, although at present the strongest evidence is from preclinical studies [111]; [110].

A similar pattern of pain exacerbation as seen in migraine and headache is observed in patients with chronic methadone use due to addiction who also show increased sensitivity to experimental and clinical pain [210]. The hypersensitivity lasts for years after methadone withdrawal [210] [216]. Taken together, these data suggest that opioids may produce a long-lasting effect on neural circuits. Recent fMRI analyses of the brain function and structure in non-medical opioid-dependent subjects [267] reported opioid-induced changes in regions implicated in the regulation of affect and impulse control, as well as in reward and motivational functions. Alteration of these latter functions is also present in chronic pain [197] and thus a cross-sensitization process may take place where the drug effects, in this case opioids, enhance the derangement of brain structure (morphometric measures of gray matter volume) and functional circuits (functional connectivity). Indeed, in non-addicts undergoing surgery, prescription opioids are reported to alter gray matter in regions involved in “reward- and affect-processing circuitry” [283]. Thus, drugs that perform a ‘good balancing act’ including buprenorphine [123] or nalbuphine [225] may have protective effects because of the receptors they target and by implication the circuits they modify. Thus, there are underlying unique responses to stress in individuals that can markedly change the manner in which an individual adapts to later stress [165] including specific clinical conditions such as pain.

Environmental Influences

Finally, we know very little about environmental influences on pain, such as the effects of geolocation, temperature, altitude, light, air composition, etc. Perhaps a good example is the adverse influence of red, blue and white light in a murine model of headache compared with green light [202]. In some environmental settings, fluorescent lights (e.g., at schools) produce a red light spectrum that exacerbates migraine onset and intensity. The implications for both the built and natural environment are largely unexplored but could be substantial [177].

The Neurobiology of Pain Stickiness

Animal models have been increasingly used to evaluate risk of or resilience to disease [175] [224] [113] [4]. Some models have shown large genetic differences in the development of pain [90] [155]. While there are few pain models of resilience in use, there are others evaluating the effects of drugs including analgesics on reward and aversion in rat genetic sub-strains [147]. Such data inform our views on how drugs may differentially affect circuits involved in behaviors (including pain) in individuals/species with different genetic backgrounds. Epigenetic effects in early life can alter responses in adulthood; for example, through programming of the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 (IL-10), in the nucleus accumbens, altering risk or resilience to addiction [229]. For example, neonatal handling is mimicked by pharmacological modulation of glia in adulthood with the drug ibudilast (a phosphodiesterase inhibitor [220] that increases expression of IL-10) inhibiting morphine-induced glial activation; as a result morphine induced place preference is inhibited. The above provide examples of how stressors may induce significant behaviors in response to pain or analgesics.

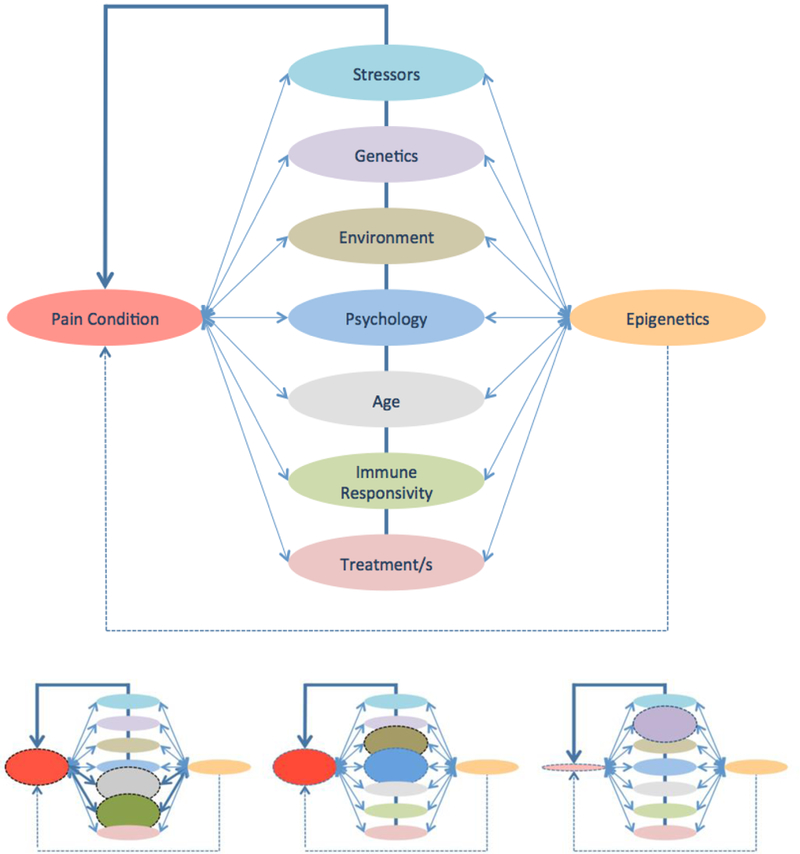

Vulnerability to chronic pain has been the subject of a number of reviews [62] [31] [82] [84]. However, less well understood are mechanisms that produce persistent, significant levels of ongoing pain, or which exacerbate pain. There are multiple interaction factors that alter neural connectivity (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Top:Multiple interactions – Disease (Pain), Effectors (Stress, Genetic etc.) and Downstream Modulation (Epigenetic changes).

The term “epigenesis” as used here refers to potential changes that may contribute to altered cellular/neuronal function via non-genetic influences on gene expression (see Text). Bottom: Weighting of Interactions has a different effect on Pain

Left Panel: Increased pain due to an altered immune responsivity due to aging: In this example Age and Immune response are abnormal. In some cases the altered immunity is protective. For example, in young (neonatal) animals and children, the propensity to develop neuropathic pain after surgery may be diminished, based on processes that include altered T lymphocyte responses, but is a major contributor to neuropathic pain adults [53].

Middle Panel: Environmental factors may exacerbate psychological factors leading to great pain: Parental-child and other relationships may contribute to processes such as fear-avoidance exacerbation of pain [270].

Right Panel: Decreased pain based on Genetic Profile: In humans [156] and rat strains [235] [155], differences in chronic pain have been reported based on altered genetic backgrounds or gene alleles that may be protective. The converse is thus also true that the genetic background may lead to the phenotypic expression of chronic pain and have different risk profiles for severity and progression/chronicity.

Synaptic Plasticity

This is a major process relating to modulation of dendritic complexity, and by implication, brain network connectivity. Recent neurosystems research has suggested that the brain is highly plastic. Imaging studies in pain have shown alterations in gray matter volume that may be increased or decreased in chronic pain [242] or as a result of pain relief [28]. For the most part, studies suggest a decrease in gray matter volume in chronic pain, but specific issues such as control for age, disease duration, and/or drug effects have not been fully assessed. The basis for alterations in gray matter volume is the amount of change in dendritic tree complexity. Synaptic connectivity is based dendrites, structures that propagate electrical activity from other neurons to a neuron’s cell body. Just as a tree in winter (no leaves, fewer branches) or summer (leaves and growing branches), dendrites are dynamic and may grow or recede. With the former, there is usually enhanced synaptic connectivity and vice versa.

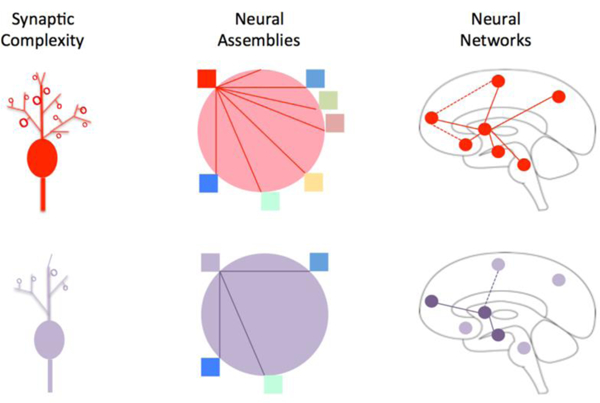

Synaptic plasticity drives dendritic morphological plasticity [195]. Such changes may result in long-term alterations in circuit function. Depending on the nature of the changes, increased numbers of dendritic synapses result in synaptic amplification in response to synaptic inputs [230]. Larger dendritic spines seem to be more permanent and smaller spines more transient [230], suggesting that memory or persistent function (ongoing activity) is related to their state and anatomy and that, without activity, the less well- formed dendritic spines may collapse. Dendrites have excitable channels, and changes in dendritic spines underlie changes in synaptic strength that may be altered, sometimes rapidly, by aging [8], gender [187] stress [142], pharmacological agents, the environment, and disease. Figure 3 is a cartoon of how dendritic plasticity may shape neural circuits.

Figure 3: Synaptic Connections, Neural Assemblies and Neural Networks.

Synaptic Complexity:The figure summarizes the complexity of normal (red) and abnormal (purple) neuronal dendrites. Altered synaptic connections take place in the pathways (functional or structural connectivity) in pain chronification in sensory [261], thalamus [159], somatosensory cortex [100], and in emotional pathways (e.g., nucleus accumbens [88]).

Neural Assemblies: Neural assemblies represent populations of cells within a structure that usually function in a coordinated or synchronized/temporal manner. Such assemblies usually act in a similar to produce a specific action or function in a manner based on past ‘experience’ or memory. The concept is that the assembly is interdependent and cohesive as a result of the pattern of synaptic connections. As such assemblies may falter when synaptic processes are diminished. Neurons within assemblies may activate or inhibit in a cohesive manner, other members of the assembly. Brain regions where these assemblies have been studied include the hippocampus [121] [181].

Neural Networks: Neural networks are dependent on connectivity. When there are alterations in this connectivity, presumably originating at the level of synaptic changes, these networks are altered. Neural networks can be measured using fMRI and represented as resting state networks. A correlation with anatomic changes has been shown using the same methods, supporting the notion of altered gray matter changes underlying changes in connectivity [37]. In chronic pain these are disrupted. For example, in painful diabetic neuropathy [43], chronic back pain [11], fibromyalgia [145], and complex regional pain syndrome [15].

Multiple processes alter dendritic morphology including cytokines and drugs. Although some cytokines may exert protective functions [68], immune systems modulate dendritic morphology and physiology [22] and pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines may have detrimental effects on the brain [214]. Drugs may also affect dendritic integrity. These changes may be considered to be morphogenic (i.e., to enhance dendritic spine integrity) or anti-morphogenic (i.e., to induce abnormal dendritic changes). Some pharmacological agents (i.e., such analgesics as amitriptyline and morphine) have seemingly beneficial effects on dendrite morphology. Amitriptyline also has a powerful neurotrophic activity [137]. Other analgesics, as well as morphine, are also thought to alter dendritic morphology [246] [162], and may be responsible for altered neural circuit function and gray matter volume following chronic opioid use [267]. Morphine withdrawal may also reduce spine density and be persistent in nature [66]. In addition, stress-related modulators such as stress hormones (i.e., cortisol) and cytokines are known to alter dendritic spines [22]. Gonadal steroids such as estradiol promote dendritic spine growth [188]. The effects of gonadal steroids on regions such as the amygdala include an increased number of spines in adult males and rapid changes of dendritic density in adult females across the estrous cycle [215]. These data are supported by rapid gray matter changes occurring across the menstrual cycle which seems to be driven by changes in estradiol concentrations [57]. The female brain may therefore be ‘at risk’ of clinical conditions, including the increased prevalence of chronic pain [94] [14], presumably because of the dynamic or changing pattern of dendritic complexity.

Stress and the Hypothalamo-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis

Given that a “…stressor pushes the physiological system away from its baseline state toward a lower utility state” [203], stress may also alter the brain [185]. Early life stress may contribute to chronic pain in adulthood [13] providing insights into the significant and long-term consequences of stress. Stress may alter immune systems [231] and produce epigenetic changes [247]. Chronic corticosteroid release alters the brain in a significant manner, including the hippocampal system, a brain region thought to be part of the brain’s stress-response system [59]. Such a relationship has been reported in migraine [176] and chronic pain [268] [194]. A number of neural mechanisms are involved in stress (including pain) resilience and vulnerability, including the neuroendocrine system, and hippocampal, cortical, reward, and serotonergic circuits [102]; these may be susceptible to epigenetic influences [63].

Brain Circuits

The logical assumption that a particular brain circuit or pattern of connectivity is implicated in a defined and replicable pattern of behavior – here referring to chronic pain or analgesic effects – would seem a rational basis for the understanding of a ‘relative pain state’. Such a state may be defined as reactive, able to alter connectivity through synaptic interactions, and by implication become adaptive, able to produce pain relief, either endogenously or in response to treatment. This may be conceptualized as reaching a state equivalent to a genetic brain disease (e.g., schizophrenia or autism), where both brain structure and function become ‘stuck’ resulting in the phenotypic expression of the specific disease. In the clinical examples noted above, specifically thalamic stroke, a sudden event results in damage to multiple neuronal circuits. As noted in the evaluation of post-stroke patients, diffusion tensor imaging shows a reduction in sensory thalamocortical fibers with associated altered functional changes in the cingulate and posterior parietal lobules [232], suggesting a change in connectivity that may underlie disruption (e.g., potential functional deafferentation) of circuits contributing to the pain state. Similar anatomic-functional alterations have been shown following a peripheral lesion (trigeminal nerve) in trigeminal neuralgia [64]. While improved imaging will contribute to further understanding of how these changes take place at an obvious level (i.e., a measurable lesion), more subtle changes observed in whole brain [116] or forebrain regions, even small ones (such as the habenula) in chronic pain [87] may contribute to major increases in brain dysfunction. In addition, in responsive individuals, treatment may induce rapid changes (i.e., within days or weeks) in gray matter volume and functional connectivity in chronic pain states [87]. Thus, while similar systems may be affected, individuals may be differentially affected based on their ‘synaptic state’. The latter, as noted in the previous section may be modified, by genetic, epigenetic and other environmental processes including tissue damage producing a new stressor on this ‘biomic’ state. The concept of reactive synaptogenesis may be a principle underlying how a new stressor (e.g., post-surgical pain) acts on an individual’s underlying biomic state and may produce a failed state of a new and non-adaptive condition in some chronic pain patients.

Individual neurons contribute to neuronal assemblies that function together: these local network processes may regulate larger networks in a complex process that may be adaptive or maladaptive. Such regulation is through synaptic sprouting or pruning in response to multiple stressors that modulate the neural allostatic state. Changes may alter synaptic efficiency and increase risk of a disease phenotype. Indeed, short-term synaptic plasticity in cortical brain regions can be produced in rodent models [138] [124], including in those pathways (e.g., thalamic-cingulate) involved in nociceptive processing [237]. These changes can be modified by environmental stress or neurotransmitters (e.g., dopamine) stress is also an environmental determinant of long-term potentiation (LTP) at these cortical synapses [139]. Synaptogenesis is a very dynamic process [119]. For example, deafferentation, as a result of alteration in dendritic/axonal connections, may be functionally restored through intact axons [120] [254]. These changes may depend on ‘experience’ including past and new events [103] and can be observed in vivo using 2-photon imaging [129]. Taken together, changes in network function may take place through changes in synaptic strength in existing synapses in addition to loss and gain of synapses that may then have an impact on connectivity. Indeed, local changes can thus alter whole networks [38]. The alterations form a basis for understanding risk of pain but also how pain conditions may get stuck. Models of how these changes may take place are discussed below.

Endogenous Regulators: Relative Opioidergic and Dopaminergic Tone.

The two systems, opioidergic and dopaminergic, are thought to play a significant role in pain chronification, dopamine being involved in both reward/anti-reward and pain processing (see [31]). Opioids are ubiquitous in the brain, including in regions involved with nociception/pain transmission [93], placebo, and reward and aversion processes [17]. Alterations in opioid receptor interactions with endogenous or exogenous opioids contribute to an overall ‘opioid tone’ that depends on receptor subtype and on receptor density. This may be analgesic (e.g., endogenous analgesia [189], placebo [271] or hyperalgesic (e.g., withdrawal [6] pain). Evidence suggesting a hypodopaminergic state in chronic pain comes from both preclinical [199] and clinical [258] data. Pain syndromes that have shown altered dopaminergic processing include burning mouth syndrome [118], atypical facial pain [117], and fibromyalgia [278]. The diminished dopaminergic tone contributes to the increased sensitivity of pain patients to emotional stimuli, somewhat similar to the phenomenon of denervation hypersensitivity. Examples of pain susceptibility with altered endogenous opioidergic or dopaminergic processing are provided below:

Opioidergic Tone:

Alterations in opioid receptor interactions with endogenous or exogenous opioids contribute to an overall ‘opioid tone’, as noted above. Thus, the level and type of opioid present may contribute to a basal state or ecosystem that can be ‘tripped’ in susceptible individuals. Two examples of altered opioidergic tone include (1) patients with particular single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) opioid profiles and pain susceptibility [198]; and (2) increased sensitivity to experimental pain in currently using or ‘recovered’ methadone/heroin addicts [71] [51] [216]. The recent imaging work has shown significant alterations of brain structure and function in individuals taking opioids [267], perhaps suggesting that changes in opioidergic tone may contribute to significant differences in response to pain through altered receptors or endogenous opioid extent in sensory (e.g., ventroposterolateral thalamus) and emotional (e.g., nucleus accumbens), or descending modulatory (e.g., periaqueductal gray) circuits. Defining an easily measurable sensitive phenotype for pain susceptibility is clearly one of the great steps forward in the pain field. A recent report evaluating pain susceptibility included functional imaging and genetic data in over 600 healthy subjects, evaluating the development of pain in previously pain free individuals [198]. The contributions of SNPs (genetic) of the mu opioid receptors to pain and state-of-the-brain reward systems and their interactions provided revealing insights into endogenous predisposition to chronic pain: the mu opioid SNP rs563649, associated with opioid receptor mu1 gene, and may be a predictor of persistent pain. Thus, rs563649 SNP analysis may serve as a marker for the evolution of pain with time.

Dopaminergic Tone:

Acute nociception is carried via ascending spinal tracts to the somatosensory cortex; its sensory/affective components are processed in the classical reward/motivational centers namely, the amygdala (fear and emotion), nucleus accumbens (reward, motivation and avoidance), cingulate (fear avoidance, unpleasantness, interoception and motor orientation), insula (subjective experience and interoception), reticular formation nuclei (arousal and vigilance), parabrachial nucleus and hypothalamus (autonomic and neuroendocrine stress responses), and habenula (aversion and reduced motivation). Thus, resulting ‘pain’ is embedded within extensive emotion/reward/motivation circuitry, representing a neural network responsible for continued existence of individuals and species via pursuit of food, water, and sex as well as via learning, decision-making, adaptation to stress, and the urgent avoidance of harm.

Acute pain activates dopamine transmission in the mesolimbic dopaminergic circuits through enhancement of extracellular dopamine release and/or by potentiation of dopamine receptors’ affinity and activity. Chronic pain exerts an opposite action by decreasing dopaminergic neurotransmission and is accompanied by decreased ability to experience joy and pleasure along with diminished motivation towards normally pleasurable stimuli, that is to say reward deficiency [85]; [82]. Such a tonic hypodopaminergic state sets in motion robust augmentation of phasic dopamine responses to pain and via conditioning, to pain-related cues manifested in overlearned motivational significance of pain-conditioned cues and sensitized incentive salience attributed to pain and to pain-related stimuli [84]. Such aberrant learning and incentive sensitization mechanisms are added or synergized by cross-sensitization to stress [82]; [31] i.e., anti-reward processes, which are autonomous feed-forward loop, whereby prior exposure to one stimulus (e.g., pain) increases subsequent response to itself and to a different stimulus (e.g., stress). Addiction models including reward deficiency [49], incentive sensitization [219], aberrant learning [134] and anti-reward [151] models, have heuristic value for understanding dopaminergic effects in chronic pain.

Addiction models have heuristic value because the same neural systems are usurped by addictive drugs [135]. Indeed, both pain and drugs are associated with massive dopaminergic surges in reward, motivation, and learning regions, albeit not entirely on the same timescale [226]. By their chronic nature, this leads to an allostatic load [31] [82] derived from such pervasive neuroadaptations as reward deficiency (i.e., diminution of drives and anhedonia), anti-reward (i.e., stress-like emotional states), incentive sensitization (i.e., assignment of excessive motivational value to pain) and aberrant learning (i.e., difficulty in extinguishing the motivational significance of pain-conditioned cues) prominently reflected in negative affect, rigidly focused motivational states, e.g., craving, or its pathophysiologic analogs of the interpretation of all pain as harm to be assertively avoided. Hence, as with drug addiction, pain chronification may be determined by a relative preponderance of the allostatic neuroadaptations as opposed to homeostatic adjustments.

In some instances, it might be possible to postulate specificity of the acute and chronic pain mechanisms. As discussed above, their dissociability is underscored by qualitatively different allostatic neuroadaptational characteristics along with preservation of the emotional awareness of pain notwithstanding extensive bilateral damage to the amygdala, insula and cingulate [92]. An alternative continuum interpretation is that chronic pain is an exaggerated form of the acute pain process. Compatible with the latter assumption, development of pain chronicity is related to the intensity or duration of the acute pain [3]. In sum, the existing preclinical and human data are still far from being conclusive on the dissociation of acute and chronic pain, and the theoretical considerations are not unambiguous.

Pain unstuck: Potential Research Targets

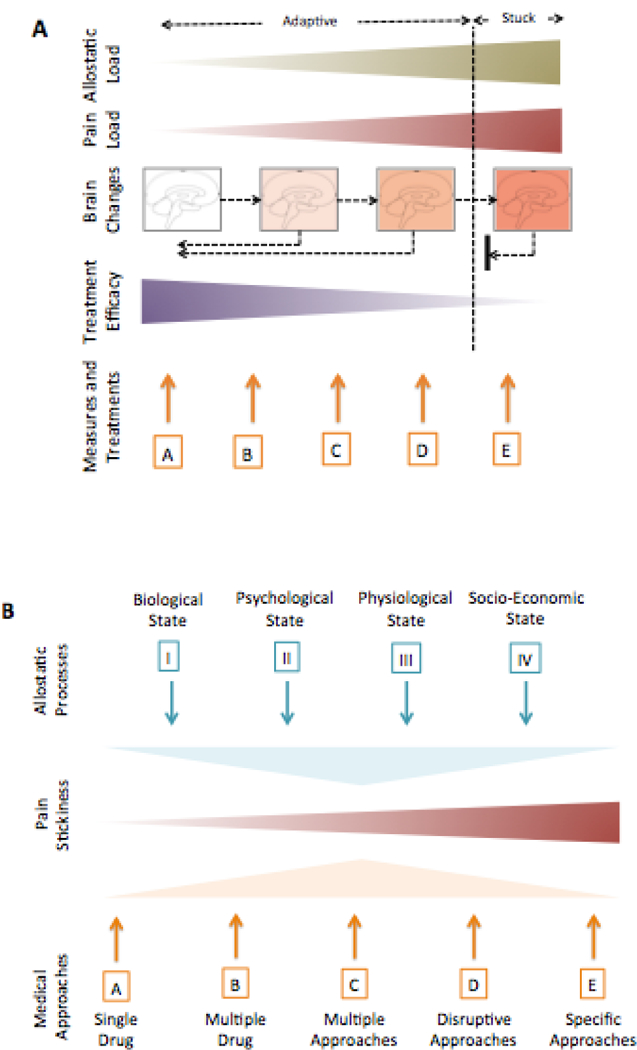

Figure 4a summarizes the interactions of multiple processes that may contribute to increased or decreased pain. But what pushes the system to stick remains the critical question, and indicates possible targets. Below, we discuss potential processes (that may sustain or limit adaptive plasticity) that may afford a direction for research to try to disentangle the puzzle.

Figure 4: integrative Treatments.

A: Drivers of Change: The figure conceptualizes the notion of how ongoing pain load may be modified by innate and external processes – Allostatic Load [184] (see B, below). The latter may become maladaptive when the process of responsiveness to stress/pain fails. These changes are manifest as alterations of brain structure and function that in its ‘terminal’ formulation is stuck and very difficult to treat. Multiple treatment options (A – E) are noted in the Measures and Treatments (detailed in B below). The current approaches are defined under Rational Medicine where all forms of treatment are or should be based on randomized control trials wherever possible. More aggressive treatments represent a failure to reverse pain chronification. Ideally specific, highly effective treatments, with tolerable or minimal side effects will become available. Markers of pain chronification have not reached a “Biomarker Status” include clinical [223], treatment resistance [148] [73], psychological measures [80] [276], physiological measures (e.g., measures of altered descending modulation [204] [248]) and brain measures [27] [266].

B: Treatment Approaches: Treatment is based on the nature of the individual’s resistance/resilience that is modified by a number of allostatic phenomena that include: (I) Biological State - pain process, genetic constitution, epigenetic modifications, general health all contribute to the biological state of an individual; (II) Psychological State - Multiple psychological processes contribute to increased risk for pain chronification including fear of pain [238] or catastrophizing [212]; anxiety and depression [260] and prior pain [125] or trauma, including torture [275]; (III) Physiological State - Although robust clinical trials are still needed a number of physiological processes that may contribute to either enhancing or making the condition worse including sleep hygiene [95], exercise [105], and diet [180]; (IV) Socio-Economic State: - Pain may be made worse by socioeconomic stressors such as work status, family, income, and educational standing [217]. A summary of premorbid, pain initiation, and post morbid approaches have been reviewed in the context of the wounded warrior [106].

Energetics and Mitochondria

We know that “…the transmission of information across neuronal synapses is an energetically taxing business” [228] and that the “dendritic distribution of mitochondria is essential and limiting for the support of synapses” [163]. Given these two findings, it is plausible that a decrement in neuronal energetics, manifested as ‘mitochondrial malaise’, may influence the form of neuronal synaptic connections [163] in chronic pain. Altered energetics means that the system for building connections for adaptive changes in neurons is malfunctioning.

Managing Synaptic Connectivity.

In conditions in which pain sticks, there may be a freeze on synaptic plasticity. This has been observed for other brain diseases such as Parkinson’s [207]. In the latter, it is thought that changes in neuronal excitability may contribute to maladaptive forms of synaptic plasticity. This may be interpreted as pain memory, but this notion is perhaps erroneous, since the process is one that is more ongoing, initially starting in a healthy condition. The ongoing process itself may contribute to a memory – altered local and general circuits – that are continually reporting a distress signal. Some have suggested that this is really one of the abnormal processes of error detection that have been considered in a number of neurological and psychiatric conditions [149], as well as in migraine [26]. Other examples may relate to parallel processes where synaptic connectivity slows down and is not adaptive. One is aging [67] where there is a reduction in the capacity of dendritic spine plasticity that may relate to vulnerability to, or persistence of, a condition [23]. In this context, a new maladaptive zone becomes the norm and is not easily modified or remodeled [282]. The data seem to confirm that such alterations lead to diminished plasticity [255] [257]. The memory for the newly maladapted state maintains the state as exemplified in a rat model of spinal cord injury [256].

Restoring Maladaptive Networks

Some chronic pain processes occur immediately after nerve damage (e.g., thalamic stroke, chemotherapy induced neuropathy). Either as drivers of central brain changes or as direct effects on brain or spinal cord tissue, a chronic pain state is established. In support of the idea of maladaptive brain networks (centralization of pain) there are a number of themes to address: (1) Imaging studies have noted altered resting state networks in chronic pain; [44] [252] [15] (2) certain non-painful conditions such as major depressive disorder may lead to generalized pain, suggesting an evolution of neural connections that contribute to a comorbid pain phenotype; (3) ‘corrupted’ networks may trend to normalization together with symptomatic relief in chronic conditions such as CRPS, [15] fibromyalgia, [99] and chronic migraine, [131], suggesting that undoing the reversal of altered connectivity or the remodeling of new connectivity may take place; (4) that certain interventions including pharmacological (e.g., ketamine [16], electrophysiological (e.g., electroconvulsive therapy - ECT [172] or transcranial magnetic stimulation - TMS [101], vagal stimulation [104], psychological treatments (e.g., CBT [236]) or novel embodied approaches [251]) may contribute to reformatting or reconstituting resting state networks.

Conclusions

Current pain treatments are largely free of any neurobiological concerns. We currently lack any specificity of treatment to mechanism, or of class of behavior to underlying biological state. We move closer to that specificity. Resting state networks provide one approach to define which systems are most affected (e.g., salience, sensorimotor, cognitive, motivational, etc.) and to target single or combined treatment approaches. In a recent paper from our group we evaluated the effects of treatments on the reconstitution of abnormal resting states in patients with chronic pain [15]. In line with this thinking, in animal models of neurological disease the reversal of molecular, electrophysiological, and behavioral deficits have been shown [41]. Most studies have only considered independent processes in preclinical and clinical studies. Epigenetic processes including DNA methylation [218] can be reversed (see [221]): stress can be controlled; psychological therapy can reduce anxiety, depression, and disability [274].

As noted by Castren and colleagues “…targeted pharmacological treatments in combination with regimes of training or rehabilitation might alleviate or reverse the symptoms of neurodevelopmental disorders” [41]. If one considers the theme forwarded by Gustin and colleagues [115] related to the four main processes that are abnormal in chronic pain (i.e., sensory-discriminative, cognitive/evaluative, affective/motivational and psychosocial sate) it would seem intuitive that having a measure of each and its relative contribution to brain changes allows for targeted therapy that would of necessity require multimodal approaches. Such a strategy may make it likely that the ‘pain chronifiers’ (e.g., allostatic load) can be evaluated and married to a neural systems approach since these targets may direct treatment profiles (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy and medication for altered cognitive evaluative processing). However, as is the case with complex phenomena with multiple interacting and usually asymmetric processes, the effects of one may have multiple effects on others. Specifically, one treatment may enhance the effects of the other; for example: “…antidepressants act permissively to facilitate environmental influence on neuronal network reorganization and so provide a plausible neurobiological explanation for the enhanced effect of combining antidepressant treatment with psychotherapy” [40]. Measures such as DNA methylation and cortisol levels may provide insights into prior or ongoing stressors [209]. Definitions of sex related changes including epigenetics relate to the prior example [183] and may provide insights into female predominance in chronic pain.

As with pharmacotherapy, there is an urgent need for a neurobiologically informed psychotherapy. Although there is consensus that psychological interventions can effect meaningful change, it is unclear whether active psychotherapeutic rehabilitation is brain altering in any sustainable way, or indeed whether it is meaningful to identity such changes. That research has not been done. We recently argued that there should be a halt on psychological treatment development for chronic pain until the science improves, in part by a better translation between pre-clinical mechanism studies and clinical intervention studies (see [77]). A closer partnership between behavioral and neurobiological science will benefit both. Further, the absence of long-term follow-up data in CBT for chronic pain remains a gap in our knowledge. Some insights may be garnered from the long-term effects of CBT on depression. In the CoBalT trial, for example, patients were followed for 3.5 years after 12–18 CBT sessions with good effect. Interestingly CBT, one of the few psychological approaches to be evaluated in RCTs [274]; [96], has also been shown, in relatively short studies (approximately 11 weeks), to alter gray matter or improve functional connectivity in chronic pain patients [236]; [233]. These studies suggest structural and functional changes with associated improvement in pain patients but do not differentiate responders from non-responders (when pain gets stuck). However, for other psychological treatments RCTs are for the most part lacking [79]. This field is in its infancy and is a promising area for development.

A critical first step is to place the biological function of pain as a motivational drive to avoid harm at the center of any psychotherapeutic attempts to alter sensation, ‘un-lock’ fixed pain behavior, or promote resilience in a system used to prioritizing return to homeostasis [74]. Next generation behavioral medicine will move away from encouraging acceptance of pain as inevitable, but instead will seek to alter that inevitability. To that end, we have recently put forward a new model wherein pain comprises two neuroanatomical systems: subcortical circuits mediating unconscious and automatic threat-related physiologic and behavioral responses in conjunction with closely linked, yet potentially dissociable higher corticolimbic networks producing conscious pain experiences with corresponding sets of drives and behaviors [83]. The proposed model supports the use of both psychosocial and pharmacological interventions for amelioration of chronic pain problems [85]. Patients with predominately subcortical unconscious pain components may not be amenable for certain types of psychological treatment and the time is ripe to explore therapeutic options for these patients [83].

The opportunities for integrated personalized medicine for pain are indeed exciting [29]. In an ideal world, optimal pain management would include: (1) understanding an individual’s genetic (genetic evaluations may only provide some insight to risk of chronic pain) and psychological history and status [171]; (2) aggressive perioperative processes including understanding the nociceptive load during surgery [30]; [154]; (3) therapies for any early onset pain; and (4) a greater understanding of the role of aggressive approaches to ‘reset’ brain function, as has been attempted in for some conditions with TMS [9], or even ECT [250]. These themes are presented in Figure 4 as two opposing processes – “Drivers for Change” (Figure 4a) that may induce chronification and potential biomarkers for these; and “Treatment Approaches” (Figure 4b) that recapitulate the model presented previously [106].

The neurobiology of drive and allostasis, used to account for stickiness in pain experience and disability behavior, has important implications: it can forge insight into the problem of how pain chronifies, help explain treatment efficacy and failure, and can support our efforts to carve out much needed new avenues for clinical development.

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by a grant from the NIH, Award K24NS064050 to DB NICHD R01HD083133 to DB.

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Low Back Pain Fact Sheet. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Bethesda, MA: National Institutes of Health, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Adler NE, Stewart J. Preface to the biology of disadvantage: socioeconomic status and health. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010;1186:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Althaus A, Arranz Becker O, Neugebauer E. Distinguishing between pain intensity and pain resolution: using acute post-surgical pain trajectories to predict chronic post-surgical pain. Eur J Pain 2014;18(4):513–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Alvarez P, Levine JD, Green PG. Neonatal handling (resilience) attenuates water-avoidance stress induced enhancement of chronic mechanical hyperalgesia in the rat. Neurosci Lett 2015;591:207–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Andersen G, Vestergaard K, Ingeman-Nielsen M, Jensen TS. Incidence of central post-stroke pain. Pain 1995;61(2):187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Angst MS, Koppert W, Pahl I, Clark DJ, Schmelz M. Short-term infusion of the mu-opioid agonist remifentanil in humans causes hyperalgesia during withdrawal. Pain 2003;106(1–2):49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Attridge N, Crombez G, Van Ryckeghem D, Keogh E, Eccleston C. The Experience of Cognitive Intrusion of Pain: scale development and validation. Pain 2015;156(10):1978–1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Auffret A, Gautheron V, Repici M, Kraftsik R, Mount HT, Mariani J, Rovira C. Age-dependent impairment of spine morphology and synaptic plasticity in hippocampal CA1 neurons of a presenilin 1 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 2009;29(32):10144–10152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Avery DH, Zarkowski P, Krashin D, Rho WK, Wajdik C, Joesch JM, Haynor DR, Buchwald D, Roy-Byrne P. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of chronic widespread pain: a randomized controlled study. J ECT 2015;31(1):57–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bai G, Ren K, Dubner R. Epigenetic regulation of persistent pain. Transl Res 2015;165(1):177–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Balenzuela P, Chernomoretz A, Fraiman D, Cifre I, Sitges C, Montoya P, Chialvo DR. Modular organization of brain resting state networks in chronic back pain patients. Front Neuroinform 2010;4:116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Barabasi AL, Oltvai ZN. Network biology: understanding the cell’s functional organization. Nat Rev Genet 2004;5(2):101–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bartholomeusz MD, Callister R, Hodgson DM. Altered psychophysiological reactivity as a prognostic indicator of early childhood stress in chronic pain. Med Hypotheses 2013;80(2):146–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bartley EJ, Fillingim RB. Sex differences in pain: a brief review of clinical and experimental findings. Br J Anaesth 2013;111(1):52–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Becerra L, Sava S, Simons LE, Drosos AM, Sethna N, Berde C, Lebel AA, Borsook D. Intrinsic brain networks normalize with treatment in pediatric complex regional pain syndrome. Neuroimage Clin 2014;6:347–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Becerra L, Schwartzman RJ, Kiefer RT, Rohr P, Moulton EA, Wallin D, Pendse G, Morris S, Borsook D. CNS Measures of Pain Responses Pre- and Post-Anesthetic Ketamine in a Patient with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Pain Med 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Benedetti F, Mayberg HS, Wager TD, Stohler CS, Zubieta JK. Neurobiological mechanisms of the placebo effect. J Neurosci 2005;25(45):10390–10402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Excessive acute migraine medication use and migraine progression. Neurology 2008;71(22):1821–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Excessive opioid use and the development of chronic migraine. Pain 2009;142(3):179–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Migraine chronification. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2011;11(2):139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Binder EB, Bradley RG, Liu W, Epstein MP, Deveau TC, Mercer KB, Tang Y, Gillespie CF, Heim CM, Nemeroff CB, Schwartz AC, Cubells JF, Ressler KJ. Association of FKBP5 polymorphisms and childhood abuse with risk of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in adults. JAMA 2008;299(11):1291–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bitzer-Quintero OK, Gonzalez-Burgos I. Immune system in the brain: a modulatory role on dendritic spine morphophysiology? Neural Plast 2012;2012:348642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bloss EB, Janssen WG, Ohm DT, Yuk FJ, Wadsworth S, Saardi KM, McEwen BS, Morrison JH. Evidence for reduced experience-dependent dendritic spine plasticity in the aging prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci 2011;31(21):7831–7839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Boccard SGJ, Prangnell SJ, Pycroft L, Cheeran B, Moir L, Pereira EAC, Fitzgerald JJ, Green AL, Aziz TZ. Long-Term Results of Deep Brain Stimulation of the Anterior Cingulate Cortex for Neuropathic Pain. World Neurosurg 2017;106:625–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Boivie J, Leijon G, Johansson I. Central post-stroke pain--a study of the mechanisms through analyses of the sensory abnormalities. Pain 1989;37(2):173–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Borsook D, Aasted CM, Burstein R, Becerra L. Migraine Mistakes: Error Awareness. Neuroscientist 2014;20(3):291–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Borsook D, Becerra L, Hargreaves R. Biomarkers for chronic pain and analgesia. Part 2: how, where, and what to look for using functional imaging. Discov Med 2011;11(58):209–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Borsook D, Erpelding N, Becerra L. Losses and gains: chronic pain and altered brain morphology. Expert Rev Neurother 2013;13(11):1221–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Borsook D, Kalso E. Transforming pain medicine: adapting to science and society. Eur J Pain 2013;17(8):1109–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Borsook D, Kussman BD, George E, Becerra LR, Burke DW. Surgically induced neuropathic pain: understanding the perioperative process. Ann Surg 2013;257(3):403–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Borsook D, Linnman C, Faria V, Strassman AM, Becerra L, Elman I. Reward deficiency and anti-reward in pain chronification. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 2016;68:282–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Borsook D, Maleki N, Becerra L, McEwen B. Understanding migraine through the lens of maladaptive stress responses: a model disease of allostatic load. Neuron 2012;73(2):219–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bortsov AV, Smith JE, Diatchenko L, Soward AC, Ulirsch JC, Rossi C, Swor RA, Hauda WE, Peak DA, Jones JS, Holbrook D, Rathlev NK, Foley KA, Lee DC, Collette R, Domeier RM, Hendry PL, McLean SA. Polymorphisms in the glucocorticoid receptor co-chaperone FKBP5 predict persistent musculoskeletal pain after traumatic stress exposure. Pain 2013;154(8):1419–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bowsher D Central pain: clinical and physiological characteristics. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996;61(1):62–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Brandsborg B, Dueholm M, Nikolajsen L, Kehlet H, Jensen TS. A prospective study of risk factors for pain persisting 4 months after hysterectomy. Clin J Pain 2009;25(4):263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Brennan KC, Bates EA, Shapiro RE, Zyuzin J, Hallows WC, Huang Y, Lee HY, Jones CR, Fu YH, Charles AC, Ptacek LJ. Casein kinase idelta mutations in familial migraine and advanced sleep phase. Science translational medicine 2013;5(183):183ra156, 181–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Bullmore E, Sporns O. Complex brain networks: graph theoretical analysis of structural and functional systems. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009;10(3):186–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Buonomano DV, Merzenich MM. Cortical plasticity: from synapses to maps. Annu Rev Neurosci 1998;21:149–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Burke D, Fullen BM, Stokes D, Lennon O. Neuropathic pain prevalence following spinal cord injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Pain 2017;21(1):29–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Castren E Neuronal network plasticity and recovery from depression. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70(9):983–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Castren E, Elgersma Y, Maffei L, Hagerman R. Treatment of neurodevelopmental disorders in adulthood. J Neurosci 2012;32(41):14074–14079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Casucci G, Cevoli S. Controversies in migraine treatment: opioids should be avoided. Neurol Sci 2013;34 Suppl 1:S125–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Cauda F, D’Agata F, Sacco K, Duca S, Cocito D, Paolasso I, Isoardo G, Geminiani G. Altered resting state attentional networks in diabetic neuropathic pain. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010;81(7):806–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Cauda F, Sacco K, Duca S, Cocito D, D’Agata F, Geminiani GC, Canavero S. Altered resting state in diabetic neuropathic pain. PLoS One 2009;4(2):e4542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, Hansen RN, Sullivan SD, Blazina I, Dana T, Bougatsos C, Deyo RA. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med 2015;162(4):276–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Chu LF, Angst MS, Clark D. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia in humans: molecular mechanisms and clinical considerations. Clin J Pain 2008;24(6):479–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Cleveland RJ, Luong ML, Knight JB, Schoster B, Renner JB, Jordan JM, Callahan LF. Independent associations of socioeconomic factors with disability and pain in adults with knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013;14:297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Cole SW, Arevalo JM, Manu K, Telzer EH, Kiang L, Bower JE, Irwin MR, Fuligni AJ. Antagonistic pleiotropy at the human IL6 promoter confers genetic resilience to the pro-inflammatory effects of adverse social conditions in adolescence. Dev Psychol 2011;47(4):1173–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Comings DE, Blum K. Reward deficiency syndrome: genetic aspects of behavioral disorders. Prog Brain Res 2000;126:325–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Commerce USDo. United States Cesus Bureau, Vol. 2018.

- [51].Compton P, Canamar CP, Hillhouse M, Ling W. Hyperalgesia in heroin dependent patients and the effects of opioid substitution therapy. J Pain 2012;13(4):401–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Costigan M, Belfer I, Griffin RS, Dai F, Barrett LB, Coppola G, Wu T, Kiselycznyk C, Poddar M, Lu Y, Diatchenko L, Smith S, Cobos EJ, Zaykin D, Allchorne A, Gershon E, Livneh J, Shen PH, Nikolajsen L, Karppinen J, Mannikko M, Kelempisioti A, Goldman D, Maixner W, Geschwind DH, Max MB, Seltzer Z, Woolf CJ. Multiple chronic pain states are associated with a common amino acid-changing allele in KCNS1. Brain 2010;133(9):2519–2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Costigan M, Moss A, Latremoliere A, Johnston C, Verma-Gandhu M, Herbert TA, Barrett L, Brenner GJ, Vardeh D, Woolf CJ, Fitzgerald M. T-cell infiltration and signaling in the adult dorsal spinal cord is a major contributor to neuropathic pain-like hypersensitivity. J Neurosci 2009;29(46):14415–14422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Crombez G, Eccleston C, Van Damme S, Vlaeyen JW, Karoly P. Fear-avoidance model of chronic pain: the next generation. Clin J Pain 2012;28(6):475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Crombez G, Van Ryckeghem DM, Eccleston C, Van Damme S. Attentional bias to pain-related information: a meta-analysis. Pain 2013;154(4):497–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Dahan A, van Velzen M, Niesters M. Comorbidities and the complexities of chronic pain. Anesthesiology 2014;121(4):675–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].De Bondt T, Jacquemyn Y, Van Hecke W, Sijbers J, Sunaert S, Parizel PM. Regional gray matter volume differences and sex-hormone correlations as a function of menstrual cycle phase and hormonal contraceptives use. Brain Res 2013;1530:22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].de Heer EW, Gerrits MM, Beekman AT, Dekker J, van Marwijk HW, de Waal MW, Spinhoven P, Penninx BW, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM. The association of depression and anxiety with pain: a study from NESDA. PLoS One 2014;9(10):e106907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].de Kloet ER, Joels M, Holsboer F. Stress and the brain: from adaptation to disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 2005;6(6):463–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].De Vlieger P, Crombez G, Eccleston C. Worrying about chronic pain. An examination of worry and problem solving in adults who identify as chronic pain sufferers. Pain 2006;120(1–2):138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].de Vries B, Frants RR, Ferrari MD, van den Maagdenberg AM. Molecular genetics of migraine. Hum Genet 2009;126(1):115–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Denk F, McMahon SB, Tracey I. Pain vulnerability: a neurobiological perspective. Nat Neurosci 2014;17(2):192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Descalzi G, Ikegami D, Ushijima T, Nestler EJ, Zachariou V, Narita M. Epigenetic mechanisms of chronic pain. Trends Neurosci 2015;38(4):237–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].DeSouza DD, Hodaie M, Davis KD. Diffusion imaging in trigeminal neuralgia reveals abnormal trigeminal nerve and brain white matter. Pain 2014;155(9):1905–1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Di Tommaso Morrison MC, Carinci F, Lessiani G, Spinas E, Kritas SK, Ronconi G, Caraffa A, Conti P. Fibromyalgia and bipolar disorder: extent of comorbidity and therapeutic implications. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 2017;31(1):17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Diana M, Spiga S, Acquas E. Persistent and reversible morphine withdrawal-induced morphological changes in the nucleus accumbens. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2006;1074:446–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Dickstein DL, Weaver CM, Luebke JI, Hof PR. Dendritic spine changes associated with normal aging. Neuroscience 2013;251:21–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Dinarello CA. Role of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines during inflammation: experimental and clinical findings. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 1997;11(3):91–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Doehring A, Oertel BG, Sittl R, Lotsch J. Chronic opioid use is associated with increased DNA methylation correlating with increased clinical pain. Pain 2013;154(1):15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Donaldson C, Lam D. Rumination, mood and social problem-solving in major depression. Psychol Med 2004;34(7):1309–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Doverty M, White JM, Somogyi AA, Bochner F, Ali R, Ling W. Hyperalgesic responses in methadone maintenance patients. Pain 2001;90(1–2):91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Dudley KJ, Li X, Kobor MS, Kippin TE, Bredy TW. Epigenetic mechanisms mediating vulnerability and resilience to psychiatric disorders. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 2011;35(7):1544–1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Jensen MP, Katz NP, Kerns RD, Stucki G, Allen RR, Bellamy N, Carr DB, Chandler J, Cowan P, Dionne R, Galer BS, Hertz S, Jadad AR, Kramer LD, Manning DC, Martin S, McCormick CG, McDermott MP, McGrath P, Quessy S, Rappaport BA, Robbins W, Robinson JP, Rothman M, Royal MA, Simon L, Stauffer JW, Stein W, Tollett J, Wernicke J, Witter J, Immpact. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 2005;113(1–2):9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Eccleston C Embodied: The Psychology of Physical Sensation. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [75].Eccleston C Chronic Pain as Embodied Defense: Implications for Current and Future Psychological Treatments. Pain in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Eccleston C, Crombez G. Worry and chronic pain: a misdirected problem solving model. Pain 2007;132(3):233–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Eccleston C, Crombez G. Advancing psychological therapies for chronic pain. F1000Res 2017;6:461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Eccleston C, Crombez G, Aldrich S, Stannard C. Worry and chronic pain patients: a description and analysis of individual differences. Eur J Pain 2001;5(3):309–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Eccleston C, Hearn L, Williams AC. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015(10):CD011259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Eccleston C, Morley SJ, Williams AC. Psychological approaches to chronic pain management: evidence and challenges. Br J Anaesth 2013;111(1):59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Ellis A, Bennett DL. Neuroinflammation and the generation of neuropathic pain. Br J Anaesth 2013;111(1):26–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Elman I, Borsook D. Common Brain Mechanisms of Chronic Pain and Addiction. Neuron 2016;89(1):11–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Elman I, Borsook D. Threat Response System: Parallel Brain Processes in Pain vis-a-vis Fear and Anxiety. Front Psychiatry 2018;9:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]