Abstract

Premise of the Study

The root apex is an important region involved in environmental sensing, but comprises a very small part of the root. Obtaining root apex transcriptomes is therefore challenging when the samples are limited. The feasibility of using tiny root sections for transcriptome analysis was examined, comparing RNA sequencing (RNA‐Seq) to microarrays in characterizing genes that are relevant to spaceflight.

Methods

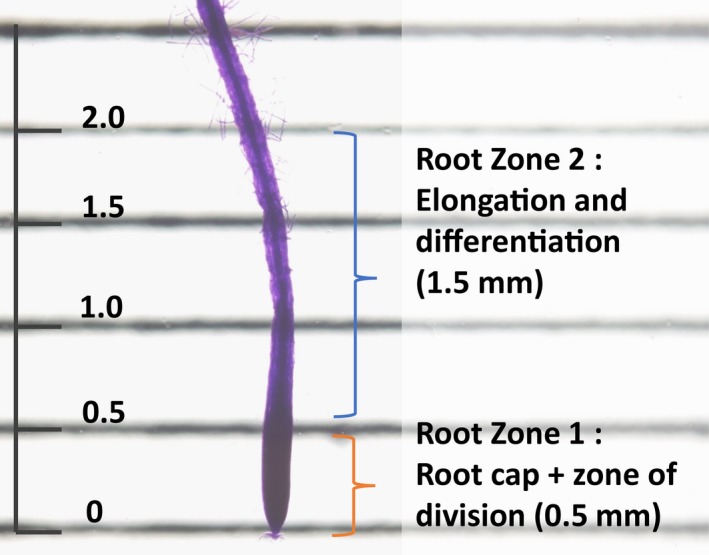

Arabidopsis thaliana Columbia ecotype (Col‐0) roots were sectioned into Zone 1 (0.5 mm; root cap and meristematic zone) and Zone 2 (1.5 mm; transition, elongation, and growth‐terminating zone). Differential gene expression in each was compared.

Results

Both microarrays and RNA‐Seq proved applicable to the small samples. A total of 4180 genes were differentially expressed (with fold changes of 2 or greater) between Zone 1 and Zone 2. In addition, 771 unique genes and 19 novel transcriptionally active regions were identified by RNA‐Seq that were not detected in microarrays. However, microarrays detected spaceflight‐relevant genes that were missed in RNA‐Seq.

Discussion

Single root tip subsections can be used for transcriptome analysis using either RNA‐Seq or microarrays. Both RNA‐Seq and microarrays provided novel information. These data suggest that techniques for dealing with small, rare samples from spaceflight can be further enhanced, and that RNA‐Seq may miss some spaceflight‐relevant changes in gene expression.

Keywords: differential expression, microarray, root apex, RNA‐Seq, transcriptome

Spaceflight experiments often come with novel challenges compared to terrestrial projects, and chief among these are the stringent limits to the amount of material that can be launched (small sample size) and restricted on orbit resources (e.g., limited space or duration in growth habitats, limited crew time). These limitations often lead to constrained scientific return from those materials, making it particularly important to obtain maximum data from each sample. The primary focus of our research program is the evaluation of the complex responses of Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. to the spaceflight environment. Plant root growth in microgravity exhibits skewing and waving behavior (Paul et al., 2012a), insightful patterns of phytohormone distribution in the primary root tips (Ferl and Paul, 2016), and distinct patterns of gene expression and protein utilization (Paul et al., 2012b, 2013, 2017; Ferl et al., 2015). Recent studies have focused on the root apex, with its crucial role in root growth and morphogenesis, guided by the apex's sensitivity to environmental factors such as gravity, light, and nutrients.

Root apexes and their importance

In their book The Power of Movement in Plants, Charles and Francis Darwin describe the root apex (the 1.0–1.5‐mm region from the root tip) as the most sensitive zone of the root and refer to the apex as a diffuse brain‐like organ having the sensitivity and ability to direct the movements of adjoining parts (Darwin and Darwin, 1880). Later in the literature, this sensitive part of the root has been referred to with various nomenclature such as “postmitotic isodiametric zone” (Baluska et al., 1990; Ishikawa and Evans, 1992), “distal elongation zone” (Ishikawa and Evans, 1993), “transition zone” (Baluska et al., 2001), and “basal meristem zone” (De Smet et al., 2007).

The cells in the actively growing root apex undergo four distinct phases of cellular activities, based on which the regions above the root cap can be divided into four different zones: the meristematic zone, the transition zone, the zone of cell elongation, and the growth‐terminating zone (Verbelen et al., 2006). The meristematic zone is a zone of active cell divisions, whereas the transition zone is composed of cells undergoing slow cell growth in length and width. Fast cell elongation in length and bulging of root hairs from the trichoblasts are seen in the elongation zone. In the growth‐terminating zone, cells slow down elongation as they reach their mature length and develop active growth of root hairs (Verbelen et al., 2006). The root apex in general and the transition zone in particular are shown to respond to internal and external stimuli and signal adaptive root activities (Baluska et al., 2010).

Root tips play an important role in sensing external stimuli and signaling the growth and movement of plant roots in the soil. Various studies on plant response to gravity (Chen et al., 1998; Baldwin et al., 2013), light (Wan et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2013; Zhang and Yu, 2014), and touch (Massa and Gilroy, 2003) suggest the importance of root tips in these functions. However, the role of distinct zones of the root tips has not been extensively characterized, and consequently there is a need to study the subzones of the root apex in greater detail. Technologies like microarray and RNA sequencing (RNA‐Seq) enable high‐throughput gene profiling of such zones.

In the present study, we compared the gene expression differences in Zone 2 (consisting of the root elongation and root differentiation zone) with that of Zone 1 (consisting of root cap and root division zone) in order to assess the applicability of such dissections before applying the techniques to spaceflight and ground control samples. We also employed both microarray and RNA‐Seq technology to identify the differentially expressed genes between two zones of the root tip in order to compare the two techniques with respect to genes relevant to spaceflight.

This study presents several distinct points. First, it provides a high‐fidelity, comprehensive comparison of root zone–specific gene expression patterns using two transcriptome approaches under sample constrained conditions. Second, it identifies novel genes that were differentially expressed between the two root zones; these heretofore unknown genes could lead to new insights in molecular and functional analysis of root tip responses to environmental and developmental stimuli. Third, it illustrates how genes with low expression levels can be missed by RNA‐Seq, which in the present case resulted in the failure of RNA‐Seq to identify numerous spaceflight‐relevant genes of interest. Finally, it outlines strategies for handling the molecular analyses of very small samples that require preservation in remote locations, which is relevant to research involving limited tissue samples, such as is typical for spaceflight and other expedition experiments.

METHODS

Plant material

Arabidopsis thaliana Columbia ecotype (Col‐0) seedlings were grown on sterile solid media plates composed of 2.2 g of Murashige and Skoog (MS) salts, 0.5 g of MES hydrate, 5.0 g of sucrose, and 1.0 mL of Gamborg vitamins (Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA), and then adjusted to pH 5.72 with 1 M KOH. The media was solidified with 0.5% (w/v) Phytagel (Sigma‐Aldrich). The plates were vertically oriented in growth chambers with continuous light (80–100 μmol s−2m−2) at a constant temperature of 19°C. This plant growth configuration has been used for both laboratory and spaceflight plant growth (Paul et al., 2013; Schultz et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2017). Eight‐day‐old seedlings were harvested from a single plate, placed in RNAlater (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) in 50‐mL centrifuge tubes, and stored in a freezer at −20°C.

Sample preparation for transcriptomics

Seedlings preserved in RNAlater were thawed to room temperature and transferred to an open Petri dish. The seedlings in the Petri dish and were viewed with an Olympus SZX12 dissecting microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and the Petri plate served as a working surface to select primary roots and then dissect them into their appropriate zones. A thin‐ruled grid was adhered to the bottom of the plate to facilitate precise cuts between the zones (Fig. 1). Plants were kept submerged in RNAlater at all times. Three independent seedlings were used as three biological replicates for each of the transcriptome analyses. All seedlings were grown on the same plate.

Figure 1.

Root dissection shown in eight‐day‐old Arabidopsis thaliana Columbia ecotype seedlings, grown on vertically placed Phytagel plates under continuous light. The root apex was sectioned into two zones: Zone 1 (0.5 mm; root cap and meristematic zone) and Zone 2 (1.5 mm; transition, elongation, and growth‐terminating zone). The root tip shown is an eight‐day‐old, RNA later‐preserved seedling stained with toluidine blue observed under a dissecting microscope. Scale is in millimeters.

The root tips were dissected into Zone 1 (0.5 mm from the tip, including the root cap and root division zones) and Zone 2 (1.5‐mm sections including the root elongation and root differentiation zone) (as shown in Fig. 1). Dissected RNAlater‐preserved root tips were carefully transferred into pre‐labeled microcentrifuge tubes and then flash‐frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted from these frozen samples using the ARCTURUS PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RNA concentration was determined on a Qubit Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and sample quality was assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, USA). Five nanograms of RNA from each sample was used for low‐input array and RNA sequencing. Genes that significantly changed in Zone 2 (Treatment 2) as compared to Zone 1 (Treatment 1) were measured using microarray and RNA‐Seq. The transcripts identified as significantly changed at fold change of 2 or greater from the two techniques were used for further analysis. Gene ontology (GO) analysis of the significantly changed genes (fold change) between Zone 2 and Zone 1 was conducted using agriGO (Du et al., 2010).

Microarray analyses and RNA‐Seq were performed at the Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research (ICBR) Gene Expression and Sequencing Core at the University of Florida. ICBR conducted the initial analyses of microarray and RNA‐Seq data for quality control, normalization, mapping reads to genome data, annotated transcripts, and profiling of gene expression.

Affymetrix Arabidopsis genome arrays

Sample preparation and hybridization

Five nanograms of total RNA were amplified with the Ovation Pico WTA System V2 kit (NuGEN Technologies Inc., Redwood City, California, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Fragmentation and biotinylation were performed with the Encore Biotin Module (NuGEN Technologies Inc.) as per the manufacturer's protocol. Five micrograms of amplified and labeled cDNA was fragmented and hybridized with rotation onto the Affymetrix GeneChip Arabidopsis Genome ATH1 Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, California, USA) for 16 h at 45°C. Arrays were washed on a Fluidics Station 450 (Affymetrix) using the Hybridization Wash and Stain Kit (Affymetrix) with Washing Procedure FS450_0001. Fluorescent signals were measured with an Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G.

Statistical analysis associated with microarray

Primary data analysis was performed using the R/Limma package (Ritchie et al., 2015). Affymetrix CEL files were first analyzed using the FastQC package for quality control (Babraham Institute, Cambridge, United Kingdom; http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). The arrays were then normalized using the RMA algorithm, and differential analysis was performed. Comparative analyses were conducted with the normalized signal intensity values between root tip Zone 1 and root tip Zone 2. The fold change was computed based on the normalized log‐transformed signal intensity data for each gene locus in the Zone 1 and Zone 2 groups. Differentially expressed transcripts were identified using a log2 fold change (log2 FC), at the 1% significance level, with false discovery rate (FDR) correction. Genes differentially expressed with fold change of 2 or greater at FDR <0.01 were used for further analysis.

RNA‐Seq

RNA‐Seq library preparation using SMART‐Seq V4 Ultra Low Input RNA Kit for Sequencing combined with Illumina Nextera DNA Sample Preparation Kit

Five nanograms of total RNA were used for cDNA library construction using ClonTech SMART‐Seq V4 Ultra Low Input RNA Kit for Sequencing (TaKaRa Bio USA, Mountain View, California, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, first‐strand cDNA was primed by the SMART‐SMARTer II A oligonucleotide (TaKaRa Bio USA) and then base pairs were combined with these additional nucleotides, creating an extended template. The reverse transcriptase then switched templates and continued transcribing to the end of the oligonucleotide, resulting in full‐length cDNA that contains an anchor sequence, which served as a universal priming site for second strand synthesis. cDNA was amplified with primer II A for 10 PCR cycles. Illumina sequencing libraries were then generated with 120 pg of cDNA using the Illumina Nextera DNA Sample Preparation Kit (FC‐131‐1024; Illumina, San Diego, California, USA) per the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 120 pg of cDNA was used as input for the Nextera tagmentation reaction (fragmentation and tagging), and then adapter sequences were added onto template cDNA by PCR amplification. Libraries were quantitated by the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and reverse transcription real‐time PCR (RT‐qPCR) (KAPA Library Quantification Kit, catalog no. KK4824; Kapa Biosystems, Wilmington, Massachusetts, USA). Finally, the libraries were pooled by equal molar concentration and sequenced by Illumina 2 × 150 NextSeq 500.

NextSeq 500 sequencing

In preparation for sequencing, barcoded libraries were sized on the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and then quantitated using the Qubit Fluorometer and RT‐qPCR (Kapa Biosystems, catalog no. KK4824). Individual samples were pooled equimolarly at 4 nM. This “working pool” was used as input in the NextSeq 500 instrument sample preparation protocol (Illumina, catalog no. 15048776, Rev A). Typically, a 1.3‐pM library concentration resulted in optimum clustering density in our instrument (i.e., ~200,000 clusters/mm2). Samples were sequenced on a single flow cell, using a 2 × 150 cycles (paired‐end) configuration. A typical sequencing run in the NextSeq 500 produced 750–800 million paired‐end reads with a Q30 ≥ 85%. For RNA‐Seq, approximately 40 million reads/sample provided sufficient depth for transcriptome analysis.

Mapping reads to genome data, transcript annotation, and profiling of gene expression

The paired‐end reads were mapped to the A. thaliana Columbia ecotype reference genome (TAIR10) using TopHat (Trapnell et al., 2012). A multi‐step process of transcriptome assembly and differential expression analysis was done using the Cufflinks tool (Trapnell et al., 2012). Reads that map to each transcript were counted and normalized based on fragment length and total reads. Normalized counts were expressed in terms of FPKM values (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped fragments). FPKM is directly proportional to abundance of the transcript. The expression data were generated at FDR = 0.01.

RESULTS

Transcriptome data were obtained from the two root tip zones (Fig. 1) through both microarray and RNA‐Seq. A total of approximately 33,500 and 22,700 genes were detected as expressed in the root zones from RNA‐Seq and microarray, respectively (Gene Expression Omnibus [GEO] accession GSE115555).

Differentially expressed genes in the two root zones

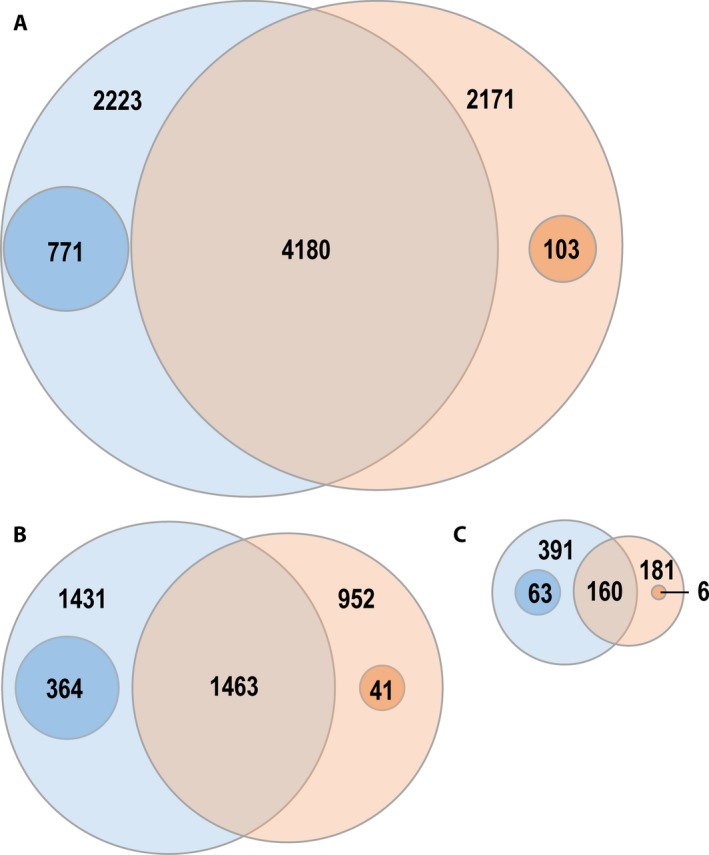

Microarray detected a total of 6351 genes significantly altered with fold change of 2 or greater, whereas RNA‐Seq detected a total of 6403 genes that were differentially expressed between the two root zones. Among these two sets of genes, 4180 genes were commonly identified by both techniques (Fig. 2A). Out of the 6403 genes detected by RNA‐Seq, 2223 genes were exclusive to RNA‐Seq at a fold change of 2 or greater. However, out of these 2223 genes, 771 were truly unique to RNA‐Seq and the remaining 1452 genes were detected by microarray but did not pass the cutoff value of fold change 2 or greater (log2 FC ≥1 or ≤1). Expression levels of genes estimated by RNA‐Seq were higher than those estimated by microarray. Therefore, a greater number of genes passed the fold change cut‐off criteria in RNA‐Seq than in the microarray. With increased fold change requirements, RNA‐Seq detected a higher number of genes compared to the microarray (Fig. 2B, C). At fold change levels of 4 and 8, RNA‐Seq identified 364 and 63 unique genes compared to 41 and six genes, respectively, identified by the microarray (inner circles in the Venn diagram; Fig. 2). Overall, RNA‐Seq was more efficient in detecting a greater number of significantly changed genes compared to the microarray.

Figure 2.

Comparison of differentially expressed genes in root Zone 2 vs. Zone 1 by RNA‐Seq and microarray. The Venn diagram shows the overlap between differentially expressed genes from RNA‐Seq and microarray data at log2 FC ≥1 or ≤1 (A), log2 FC ≥2 or ≤2 (B), and log2 FC ≥4 or ≤4 (C). Numbers indicated in the Venn circles are the differentially expressed genes exclusive to each technique at that fold level, whereas the numbers in the inner circles indicate the subset of genes truly unique to RNA‐Seq or microarray and not found in the other technique. Differentially expressed transcripts were identified using a log2 FC at FDR < 0.01.

Differentially expressed genes in the two root zones were functionally distinct

Distribution of transcripts into the most prominent GO categories is summarized in Table 1. Upregulated functional groups listed in Table 1 are the ones enriched in Zone 2, which include lipid localization and transport, root morphogenesis, root epidermal cell differentiation, cell maturation, polypropenoid biosynthetic process, root hair cell differentiation, trichoblast maturation, and secondary metabolic process. The downregulated genes in Zone 2 are those genes enriched in root Zone 1 (tip). The GO analysis of these genes mainly clustered into functional groups: cell cycle regulation, protein DNA complex assembly, chromatin assembly, DNA packaging and metabolic process, cytoskeleton organization, cell division, cellular component biogenesis, and organization (Table 1).

Table 1.

Gene ontology (GO) analysis of differentially expressed genes (Zone 2 vs. Zone 1) commonly identified in RNA‐Seq and microarray.a

| Upregulated | Downregulated | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO term | Description | FDR | GO term | Description | FDR |

| GO:0010876 | Lipid localization | 4.00E‐16 | GO:0051726 | Regulation of cell cycle | 3.70E‐06 |

| GO:0006869 | Lipid transport | 1.20E‐07 | GO:0007049 | Cell cycle | 3.90E‐06 |

| GO:0042221 | Response to chemical stimulus | 8.80E‐07 | GO:0065004 | Protein‐DNA complex assembly | 7.50E‐05 |

| GO:0009698 | Phenylpropanoid metabolic process | 1.10E‐05 | GO:0031497 | Chromatin assembly | 7.50E‐05 |

| GO:0010054 | Trichoblast differentiation | 1.80E‐05 | GO:0006323 | DNA packaging | 0.0001 |

| GO:0006810 | Transport | 2.10E‐05 | GO:0007166 | Cell surface receptor–linked signaling pathway | 0.00021 |

| GO:0010015 | Root morphogenesis | 2.10E‐05 | GO:0006333 | Chromatin assembly or disassembly | 0.0003 |

| GO:0051234 | Establishment of localization | 2.20E‐05 | GO:0007167 | Enzyme‐linked receptor protein signaling pathway | 0.00046 |

| GO:0010053 | Root epidermal cell differentiation | 3.70E‐05 | GO:0007169 | Transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase signaling pathway | 0.00046 |

| GO:0006725 | Cellular aromatic compound metabolic process | 4.30E‐05 | GO:0022402 | Cell cycle process | 0.00063 |

| GO:0051179 | Localization | 4.80E‐05 | GO:0051301 | Cell division | 0.00067 |

| GO:0050896 | Response to stimulus | 7.20E‐05 | GO:0006996 | Organelle organization | 0.0015 |

| GO:0009699 | Phenylpropanoid biosynthetic process | 8.80E‐05 | GO:0022607 | Cellular component assembly | 0.0024 |

| GO:0019748 | Secondary metabolic process | 0.0001 | GO:0007010 | Cytoskeleton organization | 0.0034 |

| GO:0048469 | Cell maturation | 0.00011 | GO:0048366 | Leaf development | 0.0055 |

| GO:0048765 | Root hair cell differentiation | 0.00011 | GO:0044085 | Cellular component biogenesis | 0.0059 |

| GO:0048764 | Trichoblast maturation | 0.00011 | GO:0016043 | Cellular component organization | 0.0067 |

| GO:0009664 | Plant‐type cell wall organization | 0.00015 | GO:0006259 | DNA metabolic process | 0.0068 |

| GO:0048468 | Cell development | 0.00016 | GO:0006325 | Chromatin organization | 0.0073 |

| GO:0022622 | Root system development | 0.00023 | GO:0048827 | Phyllome development | 0.0088 |

FDR = false discovery rate.

Gene ontology (GO) analysis of the significantly changed genes between Zone 2 and Zone 1 conducted using agriGO (Du et al., 2010). Upregulated functional groups are those enriched in Zone 2; downregulated groups are those enriched in Zone 1.

Some of the genes differentially expressed at high fold levels (Table 2) and their functions as defined in the Arabidopsis TAIR database (Huala et al., 2001) are described below.

Table 2.

List of top 20 differentially changed genes (Zone 2 vs. Zone 1) commonly identified in RNA‐Seq and ATH1 microarray. Values are shown as log2 fold change (log2 FC)

| UP Reg Gene ID | Log2 FC RNA‐Seq | Log2 FC microarray | Accession number and short description |

|---|---|---|---|

| AT4G40090 | 10.14 | 6.17 | NM_120175. Arabidopsis thaliana AGP3 (arabinogalactan‐protein 3) (AGP3) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT1G48750 | 9.01 | 5.21 | NM_103770. Arabidopsis thaliana protease inhibitor/seed storage/lipid transfer protein (LTP) family protein (AT1G48750) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT5G05960 | 8.93 | 5.76 | NM_120678. Arabidopsis thaliana protease inhibitor/seed storage/lipid transfer protein (LTP) family protein (AT5G05960) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT3G18280 | 8.82 | 4.93 | NM_112712. Arabidopsis thaliana protease inhibitor/seed storage/lipid transfer protein (LTP) family protein (AT3G18280) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT1G12040 | 8.53 | 7.29 | NM_101076. Arabidopsis thaliana LRX1 (LEUCINE‐RICH REPEAT/EXTENSIN 1); histidine phosphotransfer kinase/protein binding/structural constituent of cell wall (LRX1) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT5G67400 | 8.46 | 7.98 | NM_126140. Arabidopsis thaliana peroxidase 73 (PER73) (P73) (PRXR11) (AT5G67400) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT1G10380 | 8.31 | 5.16 | NM_100912. Arabidopsis thaliana Putative membrane lipoprotein mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT3G54590 | 8.21 | 5.49 | NM_115316. Arabidopsis thaliana ATHRGP1 (HYDROXYPROLINE‐RICH GLYCOPROTEIN); structural constituent of cell wall (ATHRGP1) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT3G25930 | 8.08 | 5.96 | NM_113497. Arabidopsis thaliana universal stress protein (USP) family protein (AT3G25930) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT5G65530 | 8.01 | 6.86 | NM_125951. Arabidopsis thaliana protein kinase, putative (AT5G65530) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT1G02900 | 7.84 | 6.83 | NM_100171. Arabidopsis thaliana RALF1 (RAPID ALKALINIZATION FACTOR 1); signal transducer (RALF1) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT1G30870 | 7.76 | 6.18 | NM_102824. Arabidopsis thaliana cationic peroxidase, putative (AT1G30870) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT1G48930 | 7.68 | 7.19 | NM_103786. Arabidopsis thaliana AtGH9C1 (Arabidopsis thaliana glycosyl hydrolase 9C1); catalytic/hydrolase, hydrolyzing O‐glycosyl compounds (AtGH9C1) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT5G58010 | 7.68 | 5.77 | NM_125186. Arabidopsis thaliana basic helix‐loop‐helix (bHLH) family protein (AT5G58010) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT1G75750 | 7.64 | 7.02 | NM_106225. Arabidopsis thaliana GASA1 (GAST1 PROTEIN HOMOLOG 1) (GASA1) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT5G66815 | 7.54 | 5.29 | NM_126080. Arabidopsis thaliana C‐TERMINALLY ENCODED PEPTIDE 5, CEP5 transmembrane protein(AT5G66815) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT3G21550 | 7.51 | 3.09 | NM_113050. Arabidopsis thaliana DUF679 DOMAIN MEMBRANE PROTEIN 2, ATDMP2, DMP2, DUF679 DOMAIN MEMBRANE PROTEIN 2 (AT3G21550) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT3G10340 | 7.40 | 5.17 | NM_111869. Arabidopsis thaliana PAL4 (Phenylalanine ammonia‐lyase 4); ammonia ligase/ammonia‐lyase/catalytic (PAL4) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT4G02270 | 7.39 | 6.70 | NM_116460. Arabidopsis thaliana pollen Ole e 1 allergen and extensin family protein (AT4G02270) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT5G44130 | 7.37 | 5.33 | NM_123780. Arabidopsis thaliana FLA13 (FASCICLIN‐LIKE ARABINOGALACTAN PROTEIN 13 PRECURSOR) (FLA13) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT5G19520 | −5.59 | −4.39 | NM_121957. Arabidopsis thaliana MSL9 (MECHANOSENSITIVE CHANNEL OF SMALL CONDUCTANCE‐LIKE 9); mechanically‐gated ion channel (MSL9) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT3G13175 | −5.61 | −3.43 | NM_112157. Arabidopsis thaliana unknown protein (AT3G13175) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT2G38810 | −5.72 | −5.54 | NM_129438. Arabidopsis thaliana HTA8 (HISTONE H2A 8); DNA‐binding (HTA8) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT5G13870 | −5.78 | −4.06 | NM_121390. Arabidopsis thaliana EXGT‐A4 (ENDOXYLOGLUCAN TRANSFERASE A4); hydrolase, acting on glycosyl bonds/hydrolase, hydrolyzing O‐glycosyl compounds / x> (EXGT‐A4) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT1G57590 | −5.79 | −4.63 | NM_104556. Arabidopsis thaliana carboxylesterase (AT1G57590) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT3G51280 | −5.99 | −3.91 | NM_114987. Arabidopsis thaliana male sterility MS5, putative (AT3G51280) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT2G23050 | −6.26 | −5.40 | NM_127869. Arabidopsis thaliana NPY4 (NAKED PINS IN YUC MUTANTS 4); protein binding/signal transducer (NPY4) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT2G22610 | −6.30 | −2.95 | NM_127826. Arabidopsis thaliana kinesin motor protein‐related (AT2G22610) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT2G34020 | −6.35 | −3.11 | NM_128953. Arabidopsis thaliana calcium ion binding (AT2G34020) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT5G48940 | −6.38 | −4.74 | NM_124271. Arabidopsis thaliana leucine‐rich repeat transmembrane protein kinase, putative (AT5G48940) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT2G20515 | −6.48 | −3.32 | NM_127611. Arabidopsis thaliana pollen Ole e I family allergen protein (AT2G20515) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT2G25060 | −6.51 | −4.12 | NM_128063. Arabidopsis thaliana plastocyanin‐like domain‐containing protein (AT2G25060) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT3G52910 | −6.52 | −2.97 | At3g52910. 68416.t05420 expressed protein nearly identical to transcription activator GRL4 [Arabidopsis thaliana] GI:21539886 (unpublished) |

| AT2G45050 | −6.81 | −5.12 | NM_130069. Arabidopsis thaliana zinc finger (GATA type) family protein (AT2G45050) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT5G60530 | −6.88 | −4.32 | NM_125446. Arabidopsis thaliana late embryogenesis abundant protein‐related/LEA protein‐related (AT5G60530) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT5G10130 | −7.22 | −5.16 | NM_121051. Arabidopsis thaliana pollen Ole e 1 allergen and extensin family protein (AT5G10130) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT1G18250 | −7.39 | −5.43 | NM_001035987. Arabidopsis thaliana ATLP‐1 (ATLP‐1) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT5G28640 | −7.86 | −5.71 | NM_122747. Arabidopsis thaliana AN3 (ANGUSTIFOLIA 3); protein binding/transcription coactivator (AN3) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT2G28790 | −7.93 | −5.44 | NM_128438. Arabidopsis thaliana osmotin‐like protein, putative (AT2G28790) mRNA, complete cds. |

| AT1G52070 | −9.15 | −5.77 | NM_104088. Arabidopsis thaliana jacalin lectin family protein (AT1G52070) mRNA, complete cds. |

cds = coding DNA sequence.

Root Zone 2 was enriched with genes involved in secondary growth metabolic processes such as response to stimulus, cell elongation, differentiation and root hair development, and maturation (Table 1). Genes in these categories included arabinogalactan proteins (AT4G40090, AT5G44130), basic helix‐loop‐helix (bHLH) protein (AT5G58010), and the leucine‐rich repeats (LRX)/extensin family proteins (AT1G12040, AT4G02270). Another set of genes highly enriched in Zone 2 are the lipid metabolism proteins: the protease inhibitor/seed storage/lipid transfer protein (LTP) family proteins (AT1G48750, AT5G05960, AT3G18280). Also induced were peroxidases that are root hair specific (AT5G67400, AT1G30870) and the cell signaling gene (AT1G02900).

Root Zone 1 was enriched with genes involved in primary growth metabolisms like cellular components, cell cycle, and DNA metabolism. Genes enriched in root tip Zone 1 included: cell wall biogenesis and organization genes (AT5G13870, AT1G57590); regulation of gene expression (AT3G52910, AT2G45050); ATP/microtubule binding (AT2G22610, AT5G48940); cell division/cell cycle (AT3G51280, AT2G28790); and response to mechanical, light, and organism stimulus (AT2G23050 [gravitropism], AT2G45050 [light], AT5G19520 [mechanical], AT1G18250 and AT2G28790 [pathogen]). Other genes enriched in Zone 1 included those with predicted function of ion binding and transport (AT5G19520, AT2G34020, AT2G25060), along with late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) protein (AT5G60530).

RNA‐Seq–identified unique/novel genes not identified by microarray

RNA‐Seq detected 771 genes that were not detected by the microarray (Appendix S1). Three hundred thirty‐nine genes were enriched in root tip Zone 2 (upregulated in Zone 2), and 432 genes were enriched in root tip Zone 1 (downregulated in Zone 2) (Appendix S1). GO analysis of these genes clustered the genes into the following groups: structural constituent of ribosome, structural molecular activity, and translation elongation factor activity. The top 20 genes with highest fold change are listed in Table 3. These included extensin family protein (AT3G09925), phosphate transporter 1 (AT5G43350), ovate family protein 17 (AT2G30395), pectin lyase‐like superfamily protein (AT4G23500), cytokinin response factor 4 (AT4G27950), protein kinase family protein (AT5G07140), transducin family protein (AT4G33270), and defensin‐like protein (AT4G22235).

Table 3.

List of 20 genes with highest fold change (fold change greater than log2 4.0) uniquely identified by RNA‐Seq but not the ATH1 microarray

| Gene | Log2 FC | Symbol | Short description |

|---|---|---|---|

| AT5G07322 | 7.72 | NA | Other RNA [Source:TAIR;Acc:AT5G07322] |

| AT3G09925 | 7.35 | NA | Pollen Ole e 1 allergen and extensin family protein [Source:TAIR;Acc:AT3G09925] |

| AT1G28815 | 7.15 | NA | Unknown protein; has five BLAST hits to five proteins in two species: Archae ‐ 0; Bacteria ‐ 0; Metazoa ‐ 0; Fungi ‐ 0; Plants ‐ 5; Viruses ‐ 0; Other Eukaryotes ‐ 0 (source: NCBI BLink). [Source:TAIR;Acc:AT1G28815] |

| AT5G48920 | 7.06 | TED7 | Tracheary element differentiation‐related 7 [Source:TAIR;Acc:AT5G48920] |

| AT5G43350 | 6.94 | ATPT1 | Phosphate transporter 1;1 [Source:TAIR;Acc:AT5G43350] |

| AT2G30395 | 6.92 | ATOFP17 | Ovate family protein 17 [Source:TAIR;Acc:AT2G30395] |

| AT3G24460 | 6.81 | NA | Serinc‐domain containing serine and sphingolipid biosynthesis protein [Source:TAIR;Acc:AT3G24460] |

| AT5G57887 | 6.63 | NA | Unknown protein; FUNCTIONS IN: molecular_function unknown; INVOLVED IN: biological_process unknown; LOCATED IN: endomembrane system; Has 30201 Blast hits to 17322 proteins in 780 species: Archae ‐ 12; Bacteria ‐ 1396; Metazoa ‐ 17338; Fungi ‐ 3422; /…/ ‐ 5037; Viruses ‐ 0; Other Eukaryotes ‐ 2996 (source: NCBI BLink). [Source:TAIR;Acc:AT5G57887] |

| AT2G28671 | 6.50 | NA | Unknown protein; FUNCTIONS IN: molecular_function unknown; INVOLVED IN: biological_process unknown; LOCATED IN: cellular_component unknown; Has 30201 Blast hits to 17322 proteins in 780 species: Archae ‐ 12; Bacteria ‐ 1396; Metazoa ‐ 17338; Fungi ‐ /…/ Plants ‐ 5037; Viruses ‐ 0; Other Eukaryotes ‐ 2996 (source: NCBI BLink). [Source:TAIR;Acc:AT2G28671] |

| AT1G77885 | 6.45 | NA | Unknown protein; BEST Arabidopsis thaliana protein match is: unknown protein (TAIR:AT1G22065.1); Has 35333 Blast hits to 34131 proteins in 2444 species: Archae ‐ 798; Bacteria ‐ 22429; Metazoa ‐ 974; Fungi ‐ 991; Plants ‐ 531; Viruses ‐ 0; Other Euk /…/s ‐ 9610 (source: NCBI BLink). [Source:TAIR;Acc:AT1G77885] |

| AT5G19230 | 6.17 | NA | Glycoprotein membrane precursor GPI‐anchored [Source:TAIR;Acc:AT5G19230] |

| AT4G23500 | 5.85 | NA | Pectin lyase‐like superfamily protein [Source:TAIR;Acc:AT4G23500] |

| AT4G27950 | −4.04 | CRF4 | Cytokinin response factor 4 [Source:TAIR;Acc:AT4G27950] |

| AT3G63430 | −4.10 | TRM5 | TON1 RECRUITING MOTIF 5, TRM5 zinc finger CCCH domain protein;(source:Araport11) |

| AT5G01445 | −4.13 | NA | Unknown protein; FUNCTIONS IN: molecular_function unknown; INVOLVED IN: biological_process unknown; LOCATED IN: mitochondrion; Has 5 Blast hits to 5 proteins in 2 species: Archae ‐ 0; Bacteria ‐ 0; Metazoa ‐ 0; Fungi ‐ 0; Plants ‐ 5; Viruses ‐ 0; Ot /…/karyotes ‐ 0 (source: NCBI BLink). [Source:TAIR;Acc:AT5G01445] |

| AT5G41071 | −4.20 | NA | Unknown protein; Has 30201 Blast hits to 17322 proteins in 780 species: Archae ‐ 12; Bacteria ‐ 1396; Metazoa ‐ 17338; Fungi ‐ 3422; Plants ‐ 5037; Viruses ‐ 0; Other Eukaryotes ‐ 2996 (source: NCBI BLink). [Source:TAIR;Acc:AT5G41071] |

| AT5G07140 | −4.50 | NA | Protein kinase superfamily protein [Source:TAIR;Acc:AT5G07140] |

| AT4G33270 | −4.74 | CDC20.1 | Transducin family protein / WD‐40 repeat family protein [Source:TAIR;Acc:AT4G33270] |

| AT4G22235 | −5.24 | NA | Arabidopsis defensin‐like protein [Source:TAIR;Acc:AT4G22235] |

| AT2G22496 | −5.56 | MIR779A | MIR779a; miRNA [Source:TAIR;Acc:AT2G22496] |

NA = not applicable.

Furthermore, a total of 107 novel transcripts were identified that were mapped to the genome but did not have any gene annotation in the reference genome database. Out of these 107 transcripts, 19 were found to be significantly changed between the zones at FDR < 0.01 (Appendix S2).

Additional information from RNA‐Seq on differentially expressed genes

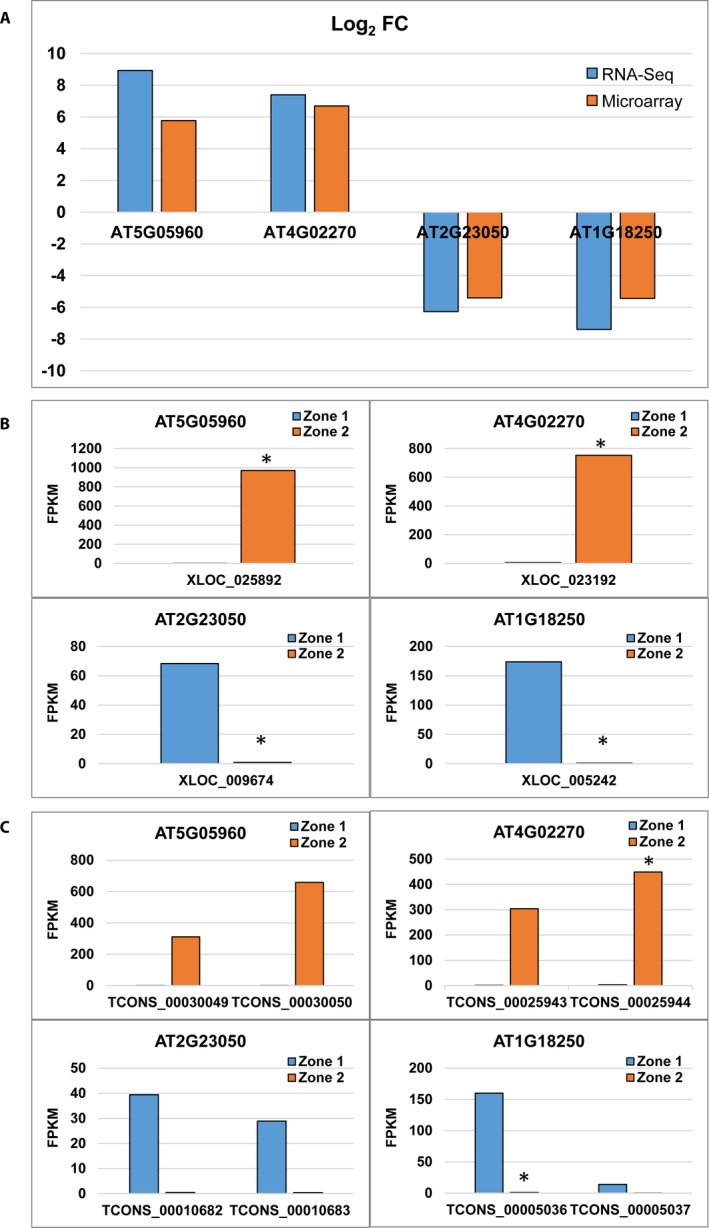

In addition to the differential gene expression data, RNA‐Seq provided information on isoforms, coding DNA sequences, and transcription start sites. Figure 3 provides examples of isoform information from four different genes in Zone 2 that were significantly altered between the two root zones to study their isoform information—two upregulated genes: AT5G05960 (protease inhibitor/seed storage/lipid transfer protein [LTP] family protein) and AT4G02270 (pollen Ole e 1 allergen and extensin family protein) and two downregulated genes: AT2G23050 (NPY4 [NAKED PINS IN YUC MUTANTS 4]) and protein binding/signal transducer (NPY4) and AT1G18250 (Arabidopsis thaumatin‐like protein [ATLP‐1]). The differential expression of these four genes in the two root zones from microarray and RNA‐Seq are shown in Fig. 3A. Log2 FC values for these genes in RNA‐Seq and microarray were comparable, and RNA‐Seq estimated a higher level of fold change for all four genes (Fig. 3A). Expression levels of these genes (Fig. 3B) and isoforms (Fig. 3C) in root Zone 1 and 2 were plotted using FPKM values measured by RNA‐Seq. Although all of these genes were significantly changed between Zone 1 and Zone 2 (Fig. 3B), the different FPKM values measured can be attributed to changes in alternative isoforms (Fig. 3C). For instance, the FPKM values of two isoforms of genes AT5G05960 and AT2G23050 are not significantly changed individually (Fig. 3C), but when the expression values are added up there is a significant change in gene expression (Fig. 3B). On the contrary, in genes AT4G02270 and AT1G18250, one isoform in each gene (TCONS_00025944 and TCONS_00005036, respectively) was significantly altered in expression, leading to a change in the total FPKM values (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Transcript/isoform information of selected genes. Differential expression analysis results for AT5G05960 (protease inhibitor/seed storage/lipid transfer protein [LTP] family protein), AT4G02270 (pollen Ole e 1 allergen and extensin family protein), AT2G23050 (NPY4 [NAKED PINS IN YUC MUTANTS 4]; protein binding/signal transducer [NPY4]), and AT1G18250 (thaumatin‐like protein ATLP‐1). (A) Log2 FC values for the genes in RNA‐Seq and microarray. (B, C) Expression plots of genes (B) and isoforms (C) showing the differences in expression in root Zone 1 and 2, measured in FPKM.

DISCUSSION

In research studies that require the use of small tissue samples, or where samples are a limiting factor, it is especially important to be able to extract as much data as possible from minimal sample material. Previous studies on root gene expression have been predominantly conducted with larger sections of the root or a pooled sample of root tips (Gupta et al., 2013; Nestler et al., 2014; Niu et al., 2014; Secco et al., 2014; Zhu et al., 2015). Recent advances in RNA isolation have enabled full transcriptomic analysis from tiny plant samples. In this study, we extracted RNA from single root tips of young A. thaliana seedlings for microarray and RNA‐Seq analysis. The ability to conduct gene expression analyses in such small tissue samples will enable identification of novel and important genes whose quantification is otherwise diluted in larger tissue/organ/pooled samples.

In the comparison of gene expression data obtained by microarray and RNA‐Seq approaches, RNA‐Seq was more powerful in identifying differentially expressed genes in the root zone samples (Fig. 2). Although this general conclusion regarding RNA‐Seq in comparison to microarrays is widely accepted, the direct comparison of RNA‐Seq to microarray data obtained from the same spaceflight‐relevant tissue sets provides a unique perspective and a direct data set with which to baseline RNA‐Seq and microarray data within the existing spaceflight database within the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)'s GeneLab (Arabidopsis Data Repository; NASA GeneLab, 2018).

However, the benefits of RNA‐Seq demonstrated here are consistent with other, broad studies that compare the two methods. Most of those benefits come from the dynamic range of RNA‐Seq. The estimated gene expression levels were generally higher in RNA‐Seq compared to the microarray (Table 2). Lower fold changes in the microarray could be attributed to saturation of fluorescence signals. In addition, microarrays depend on probe design based on previously annotated gene/expressed sequence tag sequence information, whereas RNA‐Seq provides unbiased sequence counts that can provide information on unannotated regions in addition to known, annotated genes. In this study, RNA‐Seq identified many differentially expressed genes that were not detected by microarray (Table 3, Appendix S1) and allowed for the identification of the specific isoforms of genes that contributed to the change in level of gene‐expressed information (Fig. 3). We identified 107 putative transcriptionally active regions (TARs) that were not noted in the TAIR database (Appendix S2). Of these, 19 had significantly altered expressions in the two zones. These novel transcripts could be further characterized for their function in the roots.

However, there are spaceflight‐relevant genes that were not detectable in these RNA‐Seq data. Comparison of the RNA‐Seq gene lists from Zone 1 and Zone 2 revealed that more than 50 of the highly differentially expressed spaceflight genes detected by microarray analyses were not detected by RNA‐Seq. These genes include genes that are annotated, revealed in other experiments, and many that have been confirmed to exist by RT‐qPCR. Thus, there remain genes that are spaceflight relevant that are best detected by means other than RNA‐Seq, particularly genes that have low expression levels or are rarely expressed among cell types. This phenomenon is likely to extend to other environmental responses that induce similar gene expression patterns.

The list of plant studies that examine gene expression patterns of root zones, and even root cell lineages, is ever expanding, particularly in recent years as tools and approaches provide increasing fidelity in the ability to discriminate among cell types (Birnbaum et al., 2003; Brady et al., 2007; Bruex et al., 2012; Kyndt et al., 2012; Bailey‐Serres, 2013; Gotté et al., 2016; Royer et al., 2016; Libault et al., 2017; Wendrich et al., 2017). In addition, the expansion of available reference genomes for a variety of plants enables the molecular comparisons of cell type and tissue comparisons among species (Galbraith and Birnbaum, 2006; Huang and Schiefelbein, 2015; Karve and Iyer‐Pascuzzi, 2015). The current study provides a comprehensive evaluation of the root tip transcriptome, and also contributes a unique perspective for the distribution of expressed genes along the root tip in the context of the tools and approaches used to make those assessments. The root zones were microdissected from RNAlater‐preserved roots. This approach separated the root tip organ into zones comprising several cell types, cells that make an overall contribution to the transcriptional environment in that zone. In addition, microdissection of RNAlater‐preserved tissue minimizes environmentally induced patterns of gene expression that could be associated with either the dissection of live tissue, or protoplast isolation and cell sorting.

The study presented here contributes to the growing wealth of data that expand our understanding of how the transcriptome guides Arabidopsis root function and differentiation. The experimental design used in this study provided a new look at gene expression patterns from distinct root tip zones, and also served to compare and contrast approaches to characterizing transcriptomes from preserved material of limited quantity. The transcriptomic techniques of the ATH1 microarray and RNA deep sequencing were comparable in detecting the genes enriched in the two root zones and in revealing distinct patterns of gene expression unique to each zone. An extensive discussion of the genes differentially expressed in the root zones is presented in Appendix S3. RNA‐Seq was more efficient in identifying unique and novel transcripts that were not detected by microarray; however, at the read depths used here, which are generally accepted, RNA‐Seq failed to detect some spaceflight‐relevant genes of interest, suggesting that some studies may require extended read depths or require hybridization or RT‐qPCR methods to monitor low‐expressing genes.

DATA ACCESSIBILITY

All sequence data are archived in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Ominibus (GEO accession no. GSE115555; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and in the NASA GeneLab repository (GeneLab accession no. GLDS‐208; https://genelab.nasa.gov/).

Supporting information

APPENDIX S1. List of genes uniquely identified by RNA‐Seq (differentially expressed genes that were not detected by microarray).

APPENDIX S2. List of novel genes identified by RNA‐Seq (transcripts that were mapped to the genome but did not have a gene annotation in the TAIR database).

APPENDIX S3. Detailed information about genes enriched in each root zone.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Interdisciplinary Center for Biological Research (ICBR, University of Florida) team; Y. Zhang, W. Farmerie, and A. Riva for sequencing and bioinformatics services; and laboratory members J. Callaham, A. Zupanska, E. Schultz, N. Sng, and L. David for useful discussions. We thank the Center for the Advancement of Science in Space (CASIS; GA‐2013‐104) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Space Life and Physical Sciences (NNX12AN69G) for funding and operational support.

Krishnamurthy, A. , Ferl R. J., and Paul A.‐L.. 2018. Comparing RNA‐Seq and microarray gene expression data in two zones of the Arabidopsis root apex relevant to spaceflight. Applications in Plant Sciences 6(11): e1197.

LITERATURE CITED

- Bailey‐Serres, J. 2013. Microgenomics: Genome‐scale, cell‐specific monitoring of multiple gene regulation tiers. Annual Review of Plant Biology 64: 293–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, K. L. , Strohm A. K., and Masson P. H.. 2013. Gravity sensing and signal transduction in vascular plant primary roots. American Journal of Botany 100: 126–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baluska, F. , Kubica S., and Hauskrecht M.. 1990. Postmitotic isodiametric cell‐growth in the maize root apex. Planta 181: 269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baluska, F. , Volkmann D., and Barlow P. W.. 2001. A polarity crossroad in the transition growth zone of maize root apices: Cytoskeletal and developmental implications. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 20: 170–181. [Google Scholar]

- Baluska, F. , Mancuso S., Volkmann D., and Barlow P. W.. 2010. Root apex transition zone: A signalling‐response nexus in the root. Trends in Plant Science 15: 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum, K. , Shasha D. E., Wang J. Y., Jung J. W., Lambert G. M., Galbraith D. W., and Benfey P. N.. 2003. A gene expression map of the Arabidopsis root. Science 302: 1956–1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady, S. M. , Orlando D. A., Lee J. Y., Wang J. Y., Koch J., Dinneny J. R., Mace D., et al. 2007. A high‐resolution root spatiotemporal map reveals dominant expression patterns. Science 318: 801–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruex, A. , Kainkaryam R. M., Wieckowski Y., Kang Y. H., Bernhardt C., Xia Y., Zheng X., et al. 2012. A gene regulatory network for root epidermis cell differentiation in Arabidopsis . PLoS Genetics 8: e1002446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R. J. , Hilson P., Sedbrook J., Rosen E., Caspar T., and Masson P. H.. 1998. The Arabidopsis thaliana AGRAVITROPIC 1 gene encodes a component of the polar‐auxin‐transport efflux carrier. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 95: 15112–15117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, C. , and Darwin F.. 1880. The power of movement in plants. J. Murray, London, England. [Google Scholar]

- De Smet, I. , Tetsumura T., De Rybel B., Frey N. F. D., Laplaze L., Casimiro I., Swarup R., et al. 2007. Auxin‐dependent regulation of lateral root positioning in the basal meristem of Arabidopsis . Development 134: 681–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, Z. , Zhou X., Ling Y., Zhang Z., and Su Z.. 2010. agriGO: A GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community. Nucleic Acids Research 38: W64–W70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferl, R. J. , and Paul A. L.. 2016. The effect of spaceflight on the gravity‐sensing auxin gradient of roots: GFP reporter gene microscopy on orbit. npj Microgravity 2: 15023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferl, R. J. , Koh J., Denison F., and Paul A.‐L.. 2015. Spaceflight induces specific alterations in the proteomes of Arabidopsis . Astrobiology 15: 32–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith, D. W. , and Birnbaum K.. 2006. Global studies of cell type‐specific gene expression in plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology 57: 451–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotté, M. , Bénard M., Kiefer‐Meyer M. C., Jaber R., Moore J. P., Vicré‐Gibouin M., and Driouich A.. 2016. Endoplasmic reticulum body–related gene expression in different root zones of Arabidopsis isolated by laser‐assisted microdissection. Plant Genome 9: 10.3835/plantgenome2015.08.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S. , Shi X., Lindquist I. E., Devitt N., Mudge J., and Rashotte A. M.. 2013. Transcriptome profiling of cytokinin and auxin regulation in tomato root. Journal of Experimental Botany 64: 695–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huala, E. , Dickerman A. W., Garcia‐Hernandez M., Weems D., Reiser L., Lafond F., Hanley D., et al. 2001. The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): A comprehensive database and web‐based information retrieval, analysis, and visualization system for a model plant. Nucleic Acids Research 29: 102–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L. , and Schiefelbein J.. 2015. Conserved gene expression programs in developing roots from diverse plants. Plant Cell 27: 2119–2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, H. , and Evans M. L.. 1992. Induction of curvature in maize roots by calcium or by thigmostimulation: Role of the postmitotic isodiametric growth zone. Plant Physiology 100: 762–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, H. , and Evans M. L.. 1993. The role of the distal elongation zone in the response of maize roots to auxin and gravity. Plant Physiology 102: 1203–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karve, R. , and Iyer‐Pascuzzi A. S.. 2015. Digging deeper: High‐resolution genome‐scale data yields new insights into root biology. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 24: 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyndt, T. , Denil S., Haegeman A., Trooskens G., De Meyer T., Van Criekinge W., and Gheysen G.. 2012. Transcriptome analysis of rice mature root tissue and root tips in early development by massive parallel sequencing. Journal of Experimental Botany 63: 2141–2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libault, M. , Pingault L., Zogli P., and Schiefelbein J.. 2017. Plant systems biology at the single‐cell level. Trends in Plant Science 22: 949–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massa, G. D. , and Gilroy S.. 2003. Touch modulates gravity sensing to regulate the growth of primary roots of Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant Journal 33: 435–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NASA GeneLab . 2018. Arabidopsis data repository. Website https://genelab-data.ndc.nasa.gov/genelab/search_studies/?q=&data_source=cgene&ffield=organism&fvalue=Arabidopsis+thaliana [accessed 3 October 2018].

- Nestler, J. , Liu S., Wen T.‐J., Paschold A., Marcon C., Tang H. M., Li D., et al. 2014. Roothairless5, which functions in maize (Zea mays L.) root hair initiation and elongation encodes a monocot‐specific NADPH oxidase. Plant Journal 79: 729–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Y. , Chai R., Liu L., Jin G., Liu M., Tang C., and Zhang Y.. 2014. Magnesium availability regulates the development of root hairs in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Plant Cell and Environment 37: 2795–2813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul, A.‐L. , Amalfitano C. E., and Ferl R. J.. 2012a. Plant growth strategies are remodeled by spaceflight. BMC Plant Biology 12: 232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul, A.‐L. , Zupanska A. K., Ostrow D. T., Zhang Y., Sun Y., Li J. L., Shanker S., et al. 2012b. Spaceflight transcriptomes: Unique responses to a novel environment. Astrobiology 12: 40–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul, A.‐L. , Zupanska A. K., Schultz E. R., and Ferl R. J.. 2013. Organ‐specific remodeling of the Arabidopsis transcriptome in response to spaceflight. BMC Plant Biology 13: 112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul, A.‐L. , Sng N. J., Zupanska A. K., Krishnamurthy A., Schultz E. R., and Ferl R. J.. 2017. Genetic dissection of the Arabidopsis spaceflight transcriptome: Are some responses dispensable for the physiological adaptation of plants to spaceflight? PLoS ONE 12: e0180186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, M. E. , Phipson B., Wu D., Hu Y., Law C. W., Shi W., and Smyth G. K.. 2015. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA‐sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Research 43: e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royer, M. , Cohen D., Aubry N., Vendramin V., Scalabrin S., Cattonaro F., Bogeat‐Triboulot M.‐B., and Hummel I.. 2016. The build‐up of osmotic stress responses within the growing root apex using kinematics and RNA‐sequencing. Journal of Experimental Botany 67: 5961–5973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, E. R. , Zupanska A. K., Sng N. J., Paul A.‐L., and Ferl R. J.. 2017. Skewing in Arabidopsis roots involves disparate environmental signaling pathways. BMC Plant Biology 17: 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secco, D. , Shou H., Whelan J., and Berkowitz O.. 2014. RNA‐seq analysis identifies an intricate regulatory network controlling cluster root development in white lupin. BMC Genomics 15: 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell, C. , Roberts A., Goff L., Pertea G., Kim D., Kelley D. R., Pimentel H., et al. 2012. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA‐seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nature Protocols 7: 562–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbelen, J.‐P. , De Cnodder T., Le J., Vissenberg K., and Baluska F.. 2006. The root apex of Arabidopsis thaliana consists of four distinct zones of growth activities: Meristematic zone, transition zone, fast elongation zone and growth terminating zone. Plant Signaling and Behavior 1: 296–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Y.‐L. , Eisinger W., Ehrhardt D., Kubitscheck U., Baluska F., and Briggs W.. 2008. The subcellular localization and blue‐light‐induced movement of phototropin 1‐GFP in etiolated seedlings of Arabidopsis thaliana . Molecular Plant 1: 103–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendrich, J. R. , Möller B. K., Li S., Saiga S., Sozzani R., Benfey P. N., De Rybel B., and Weijers D.. 2017. Framework for gradual progression of cell ontogeny in the Arabidopsis root meristem. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 114: E8922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W. , and Yu R.. 2014. Molecule mechanism of stem cells in Arabidopsis thaliana . Pharmacognosy Reviews 8: 105–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W. , Swarup R., Bennett M., Schaller G. E., and Kieber J. J.. 2013. Cytokinin induces cell division in the quiescent center of the Arabidopsis root apical meristem. Current Biology 23: 1979–1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M. , Callaham J. B., Reyes M., Stasiak M., Riva A., Zupanska A. K., Dixon M. A., et al. 2017. Dissecting low atmospheric pressure stress: Transcriptome responses to the components of hypobaria in Arabidopsis . Frontiers in Plant Science 8: 528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, N. , Cheng S., Liu X., Du H., Dai M., Zhou D. X., Yang W., and Zhao Y.. 2015. The R2R3‐type MYB gene OsMYB91 has a function in coordinating plant growth and salt stress tolerance in rice. Plant Science 236: 146–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

APPENDIX S1. List of genes uniquely identified by RNA‐Seq (differentially expressed genes that were not detected by microarray).

APPENDIX S2. List of novel genes identified by RNA‐Seq (transcripts that were mapped to the genome but did not have a gene annotation in the TAIR database).

APPENDIX S3. Detailed information about genes enriched in each root zone.

Data Availability Statement

All sequence data are archived in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Ominibus (GEO accession no. GSE115555; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and in the NASA GeneLab repository (GeneLab accession no. GLDS‐208; https://genelab.nasa.gov/).