Abstract

Ferret and mink coronaviruses typically cause catarrhal diarrhea in ferrets and minks, respectively. In recent years, however, systemic fatal coronavirus infection has emerged in ferrets, which resembles feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) in cats. FIP is a highly fatal systemic disease caused by a virulent feline coronavirus infection in cats. Despite the importance of coronavirus infections in these animals, there are no effective commercial vaccines or antiviral drugs available for these infections. We have previously reported the efficacy of a protease inhibitor in cats with FIP, demonstrating that a virally encoded 3C-like protease (3CLpro) is a valid target for antiviral drug development for coronavirus infections. In this study, we extended our previous work on coronavirus inhibitors and investigated the structure-activity relationships of a focused library of protease inhibitors for ferret and mink 3CLpro. Using the fluorescence resonance energy transfer assay, we identified potent inhibitors broadly effective against feline, ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpro. Multiple amino acid sequence analysis and modelling of 3CLpro of ferret and mink coronaviruses were conducted to probe the structural basis for these findings. The results of this study provide support for further research to develop broad-spectrum antiviral agents for multiple coronavirus infections. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on small molecule inhibitors of ferret and mink coronaviruses.

Keywords: Ferret coronavirus, Mink coronavirus, Feline coronavirus, 3C-like protease, Protease inhibitor

Highlights

-

•

Small molecule compounds show potent activity against 3C-like proteases of feline, ferret and mink coronaviruses in vitro.

-

•

A structure-function relationship study revealed the close structural requirements of inhibitors for these coronaviruses.

-

•

Multiple sequence analysis and modelling of proteases were conducted to probe the structural basis for the findings.

1. Introduction

Coronaviruses are enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses that belong to the Coronaviridae family. Coronaviruses infect a wide range of animal species including humans, causing a diverse array of diseases but each coronavirus tends to be species-specific. Coronaviruses are subdivided into four genera, alpha, beta, gamma and delta-coronaviruses, based on phylogenetic clustering (Adams et al., 2017). Feline, ferret and mink coronaviruses belong to the alphacoronaviruses genus and typically cause self-limiting diarrheal disease in cats, ferrets and minks, respectively. Ferrets and minks are members of the family Mustelidae that includes carnivorous mammals such as badgers, weasels, otters and wolverines. Ferrets are presumed to have been domesticated for more than two thousand years (Thomson, 1951), and over the years ferrets have become more popular as pets. They are also widely used as a small animal model in the study of some human viral infections, such as influenza A virus (Belser et al., 2011) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) coronavirus (Gretebeck and Subbarao, 2015).

Epizootic catarrhal enteritis (ECE) was first described in 1993 in domestic ferrets in the eastern part of the US (Williams et al., 2000) and subsequently reported in domestic and laboratory ferrets in the US, EU and Japan (Li et al., 2017; Provacia et al., 2011; Terada et al., 2014). The causative agent of ECE is ferret coronavirus (Williams et al., 2000; Wise et al., 2006). ECE is characterized by lethargy, vomiting, inappetence and green mucous diarrhea, and older ferrets are more severely affected by ECE than young ferrets.

Minks are closely related to ferret and there are two mink species, European minks and American minks. The European minks have become a critically endangered species, and American minks are raised on farms mainly for their fur or live in the wild. Mink epizootic catarrhal gastroenteritis (ECG) is caused by mink coronavirus and the clinical signs of ECG resemble those of ECE with anorexia, mucoid diarrhea and decreased pelt quality. Minks over four months of age are mostly affected by ECG. Since the first description of ECG in minks in 1975 (Larsen and Gorham, 1975), ECG has been reported in the US and the EU (Gorham et al., 1990; Have et al., 1992; Vlasova et al., 2011).

The morbidity of these coronavirus diarrheal diseases in ferrets and minks is high but mortality is generally low unless the infected animals have concurrent illnesses, such as Aleutian disease (Gorham et al., 1990). Interestingly, a systemic disease associated with ferret coronavirus has appeared in 2002 in the US and the EU and subsequently in Asia (Autieri et al., 2015; Garner et al., 2008; Gnirs et al., 2016; Lindemann et al., 2016; Terada et al., 2014). Ferrets affected with this novel ferret systemic coronavirus disease (FSCV) exhibit weight loss, diarrhea, anorexia and granulomatous lesions in various organs and occasional neurological signs, which indicate that a quite different disease pathogenesis is involved in this progressively fatal disease (Garner et al., 2008; Gnirs et al., 2016). This recently emerged FSCV in ferrets resembles feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), a fatal systemic disease in cats. Similar to ferret and mink coronavirus infections, feline coronavirus typically causes self-limiting diarrhea and is quite common among cats especially in high-density environments with high morbidity and low mortality [reviewed in (Pedersen, 2014)]. However, a small number of cats infected with feline coronavirus develop FIP (Garner et al., 2008; Graham et al., 2012; Lindemann et al., 2016; Michimae et al., 2010; Wise et al., 2010). The mechanism responsible for the transition from enteric viral infection to FIP is not fully understood, but the prevailing hypothesis is that viral tropism change from the intestinal enterocytes to macrophages and the inadequate cellular immunity to eliminate the mutated viruses are the major contributors to FIP development in individual cats (Barker et al., 2013; Chang et al., 2012a; Licitra et al., 2013; Pedersen et al., 2009, 2012).

Although these coronaviruses are important pathogens for animals, no effective vaccine or treatment is yet available. Thus, development of effective treatment options for these coronavirus infections is expected to provide significant benefits to these animals. Moreover, effective antiviral therapeutics that combats multiple coronaviruses would provide considerable benefits since substantial resources are needed for antiviral drug development. Coronaviruses encode two viral proteases, 3C-like protease (3CLpro) and papain-like protease, which process viral polyproteins into mature proteins. Due to the essential nature of viral proteases in virus replication, efforts have been made to identify inhibitors that target these viral proteases of important human and animal coronaviruses (Adedeji and Sarafianos, 2014; De Clercq, 2006; Deng et al., 2014; Hilgenfeld, 2014; Kim et al., 2012, 2013, 2015; Kumar et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2005). However, most of the research on coronavirus protease inhibitors has focused on SARS coronavirus, and relatively few reports are available for animal coronaviruses.

We have previously reported the antiviral effects of 3CLpro inhibitors against animal and human coronaviruses including SARS coronavirus, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) coronavirus, murine and feline coronaviruses (Galasiti Kankanamalage et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2013; Mandadapu et al., 2013b; Pedersen et al., 2018; Prior et al., 2013). We have also showed the in vivo effects of 3CLpro inhibitors in mice with murine coronavirus infection (Kim et al., 2015), and more recently in laboratory cats with FIP (Kim et al., 2016b) and client-owned cats with naturally occurring FIP (Pedersen et al., 2018).

In this study, we investigated the structure-activity relationships of a focused library of 3CLpro inhibitors for their effects against the 3CLpro of ferret and mink coronaviruses. Using the fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) assay, we identified potent inhibitors against 3CLpro of ferret and mink coronaviruses with 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of the low or sub-micromolar range. A multiple alignment analysis of 3CLpro of ferret and mink coronaviruses was conducted, and three-dimensional homology models of ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpro were constructed and compared with the crystal structure of feline coronavirus 3CLpro to study the structural basis for the activity of 3CLpro inhibitors.

2. Materials and method

2.1. Compounds

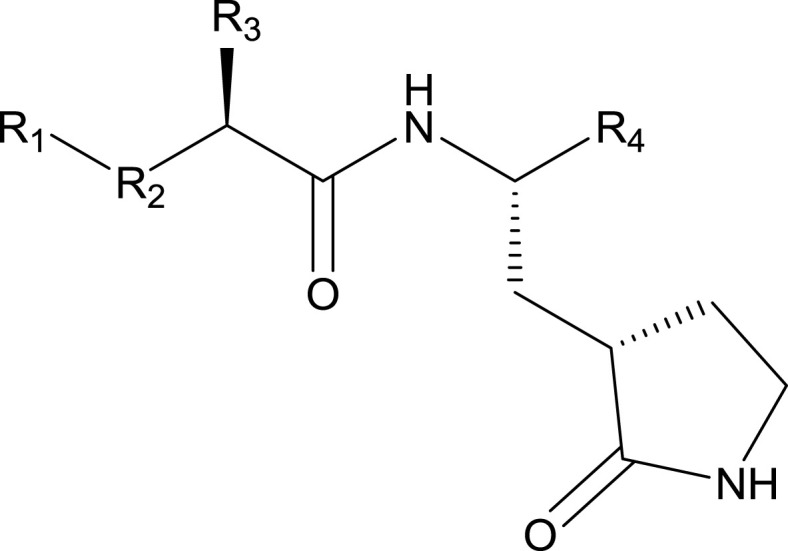

Synthesis of NPI52 (Prior et al., 2013), GC376 (Kim et al., 2012), GC551 and GC543 (Mandadapu et al., 2013a), GC523 (Mandadapu et al., 2012), GC583, GC587, GC591 and GC597 (Galasiti Kankanamalage et al., 2015), GC772 and GC774 (Galasiti Kankanamalage et al., 2017) were previously described. The compound list is shown in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Compound structures and activity of the compounds against 3CLpro of ferret, mink and feline coronaviruses in the FRET assay.

| Compound | R1 (Cap) | R2 | R3 | R4 (war head) | IC50 (μM)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feline CoV | Ferret CoV | Mink CoV | |||||

| GC376 | (C6H5)CH2 | O(C O)NH | Leu (Isobutyl) | CH(OH)SO3Na | 0.49 ± 0.07 | 1.33 ± 0.19 | 1.44 ± 0.38 |

| GC523 | (C O)CONH cyclohexyl | 1.41 ± 0.24 | 0.83 ± 0.41 | 1.95 ± 0.40 | |||

| GC543 | Cha(Cyclohexyl methyl) | CHO | 0.69 ± 0.13 | 1.45 ± 0.30 | 1.55 ± 0.24 | ||

| GC551 | CH(OH)SO3Na | 0.42 ± 0.08 | 1.04 ± 0.28 | 0.86 ± 0.28 | |||

| GC583 | m-Cl(C6H4)CH2 | CHO | 0.63 ± 0.15 | 0.98 ± 0.36 | 1.61 ± 0.42 | ||

| GC587 | CH(OH)SO3Na | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.29 ± 0.08 | 0.59 ± 0.12 | |||

| GC591 | (C O)CONH Cyclopropyl | 6.57 ± 1.43 | >50 | >40 | |||

| GC597 | Leu | CHO | 0.88 ± 0.18 | 1.45 ± 0.18 | 1.64 ± 0.30 | ||

| GC772 | m-Cl(C6H4) | SO2NH | Cha | CHO | 10.68 ± 1.17 | 9.16 ± 1.72 | 7.26 ± 1.57 |

| GC774 | p-Cl(C6H4) | SO2NH | 10.08 ± 1.62 | 24.19 ± 6.99 | 21.45 ± 8.91 | ||

IC50 indicates the 50% inhibitory concentration. Values are the means and the standard error of the means from at least three independent experiments. The IC50 value of GC376 for feline coronavirus 3CLpro was previously reported by us (Kim et al., 2016b).

2.2. Cell and virus

Crandell-Rees feline kidney cells (CRFK) and a feline coronavirus (FIPV-1146) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Feline coronavirus was grown with Eagle's Minimal Essential Medium (MEM) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin in CRFK cells.

2.3. Expression and purification of 3CLpro of ferret and mink coronaviruses

The codon-optimized cDNAs encoding the full length of 3CLpro of ferret coronavirus NL-2010 (GenBank accession number: KM347965.1) and mink coronavirus WD1133 (GenBank accession number: HM245926.1) with the nucleotides for 6 His residues at the N-terminus were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Each synthesized gene was subcloned into the pET28(+) vector (Addgene, Cambridge, MA). Each 3CLpro was expressed and purified following the standard procedures previously described by our group (Kim et al., 2012, 2016b). Briefly, the vector was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and each protein was expressed in Luria Bertani broth by induction with 1mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside for 4–6 h at 37 °C in a shaking incubator. The harvested cells were centrifuged, and the supernatants were subject to Ni-NTA affinity columns (QI-AGEN, Valencia, CA) for purification of 3CLpro. The purified 3CLpro were stored at −80 °C until use. The cloning and expression of feline coronavirus 3CLpro was previously reported (Kim et al., 2016b).

2.4. FRET assay

The FRET-based assays for ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros were developed following the procedures previously described (Chang et al., 2012b). First, the activity of the recombinant ferret 3CLpro and mink coronavirus 3CLpro, as well as feline coronavirus 3CLpro, was confirmed in the FRET assay. The substrate used in the FRET assay is 5-FAM-SAVLQSGK-QXL520-NH2. Serial dilutions of each 3CLpro were prepared in 25 μl of assay buffer (120 mM NaCl, 4mM Dithiothreitol, 50 mM HEPES, 30% Glycerol at pH 6.0). Then each dilution was mixed with 25 μl of assay buffer containing the substrate and the mixture was added to a black 96 well imaging microplate (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The plate was incubated at 37 °C and serial fluorescence readings were measured at up to 90 min on a fluorescence microplate reader (FLx800, Biotek, Winnooski, VT) at an excitation and an emission wavelength of 485 nm and 516 nm, respectively. The percentage activity progress was calculated for each 3CLpro compared to the activity at 90 min.

After confirmation of the activity of 3CLpro, the inhibitory effect of each compound on the activity of 3CLpro was determined as previously described (Chang et al., 2012b; Kim et al., 2012). Serial dilutions of each compound stock (10 mM) were prepared in DMSO prior to the assay. Each compound dilution was added to 3CLpro in 25 μl of assay buffer. Following incubation at 37 °C for 30 min, the mixture was added to a black 96 well imaging microplate containing substrate in 25 μl of assay buffer. Following the incubation of the plate at 37 °C for 30 min, fluorescence readings were measured on a fluorescence microplate reader. Relative fluorescence was calculated by subtracting background fluorescence from raw fluorescence values (Chang et al., 2012b; Kim et al., 2012). The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50), which is the concentration of a compound that reduces fluorescence by half in the FRET assay, was calculated for each compound using non-linear regression analysis (four parameter variable slope) in GraphPad Prism software version 6.07 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

2.5. Multiple amino acid sequence alignment of feline, ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros

The amino acid sequences of 3CLpro of ferret coronaviruses from Netherlands (GenBank accession number: KM347965.1), the US (GenBank accession numbers: KX512809.1 and KX512810.1) and Japan (GenBank accession numbers: LC119077.1 and LC215871.1), and the amino acid sequences of 3CLpro of mink coronaviruses from the US. (GenBank accession numbers: HM245925.1 and HM245926.1) and China (GenBank accession number: MF113046.1) were aligned using Clustal Omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/) (McWilliam et al., 2013). Forty strains of feline coronaviruses whose full 3CLpro sequences are available in the GenBank were also included in the multiple sequence alignment. The 3CLpro of transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), a porcine coronavirus (GenBank accession number: ABG89303.1), has a high amino acid homology with feline coronavirus 3CLpro (92.05–93.71%), and the crystal structure of GC376 bound with TGEV 3CLpro was previously reported by our group (Kim et al., 2012). Therefore, TGEV 3CLpro was included as a reference.

2.6. Antiviral effects of compounds in cell culture

A stock solution of each compound (10 mM) was prepared in DMSO and serial dilutions of compound were prepared in medium. Mock (medium only) or each compound dilution was added to confluent CRFK cells in 12 or 24 well plates, and the cells were immediately inoculated with feline coronavirus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.05. The virus infected cells were then incubated at 37 °C for up to 36 h until extensive cytopathic effects (CPE) appeared. Following repeated freezing and thawing of the cells, virus titers were determined. Briefly, ten-fold serial dilutions of each well were added to confluent CRFK cells in 96 well plates, and the 96 well plates were incubated at 37 °C until no further CPE was observed. The 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) was then calculated by the standard TCID50 method (Reed and Muench, 1938). The 50% effective concentration (EC50) is the concentration of a compound that reduces virus titers by half in cell culture. The EC50 of each compound was calculated using non-linear regression analysis (four parameter variable slope) in GraphPad Prism software version 6.07 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

2.7. Nonspecific cytotoxic effect

To assess the cytotoxicity of each compound, semi-confluent CRFK cells grown in 24-well plates were incubated with a compound at various concentrations up to 150 μM at 37° for 36 h. Cell cytotoxicity was measured by CytoTox 96 nonradioactive cytotoxicity assay kit following the manufacturer's protocol (Promega, Madison, WI), and the 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) of each compound was determined using non-linear regression analysis (four parameter variable slope) in GraphPad Prism software. The in-vitro therapeutic index (CC50/EC50) of each compound was also calculated for feline coronavirus.

2.8. Three-dimensional structural modelling of ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros

Three-dimensional structures of ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros were built using the I-TASSER server (https://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/) (Yang et al., 2015). These ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpro models have a C-score of 2, estimated TM-score of 0.99 ± 0.04 and estimated root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 2.3 ± 1.8 Å. The constructed ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpro models were superposed with the crystal structure of TGEV 3CLpro (PDB accession number: 4F49) or feline coronavirus 3CLpro (PDB accession number: 4ZRO9) using the PyMol molecular graphics system, Version 1.8 (Schrodinger LLC, Cambridge, MA) (DeLano, 2010).

3. Results

3.1. Effects of compounds against 3CLpro of ferret and mink coronaviruses in the FRET assay

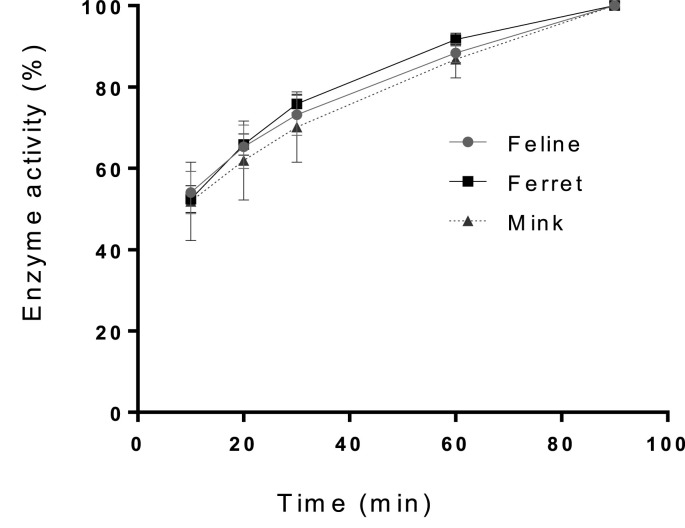

The activities of the recombinant ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros were determined and compared to that of feline coronavirus 3CLpro prior to the inhibition assay. The activity of each 3CLpro gradually increased over time, following a similar trend with that of feline coronavirus 3CLpro, confirming the activity of ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Activities of the recombinant ferret, mink and feline coronavirus 3CLpros in the FRET assay. Each expressed 3CLpro was added to assay buffer containing a fluorogenic substrate. The mixture was then incubated at 37 °C and fluorescence readings were measured at various time intervals up to 90 min of incubation. The percentage activity progress was calculated for each 3CLpro compared to the activity at 90 min, and the progress curve was plotted against time.

We then evaluated the inhibitory activity of the compounds with variations on R groups against each 3CLpro. The chemical structures of the compounds and their IC50 values are listed in Table 1. GC376 was previously shown to be effective in cats with experimental or naturally-occurring FIP (Kim et al., 2016b; Pedersen et al., 2018). Therefore, GC376 was included as a reference compound. The IC50 values of GC376 against ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpro were determined at 1.33 and 1.44 μM, respectively, moderately higher than the IC50 of 0.49 μM against feline coronavirus 3CLpro. A warhead is a reactive functional group on a compound, which interacts with the cysteine residue in the active site of 3CLpro. When the bisulfite adduct warhead [CH(OH)SO3Na] at R4 on GC376 was replaced with an α-ketoamide warhead, (C O)CONHcyclohexyl (GC523), the activity was moderately decreased against feline coronavirus 3CLpro, but less pronounced changes in activity were observed against ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros. Replacement of Leu (isobutyl) at R3 in GC376 with Cha (cyclohexyl methyl) (GC551) did not change the activity against feline coronavirus 3CLpro and only slightly increased the activity against ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros. This result suggest that Leu and Cha are functionally interchangeable for all three 3CLpros. The similar effect of Leu and Cha at R3 position against these coronavirus 3CLpros was also demonstrated by GC583 and GC597. The substitution of a benzyl group (C6H5) at R1 with m-Chloro benzyl group in compounds with a bisulfide adduct warhead (GC551 and GC587) resulted in increased activities against all three 3CLpros. The bisulfite adduct at R4 (GC551 and GC587) resulted in increased activities compared to aldehyde counterparts (GC543 and GC583) against all three 3CLpros. The replacement of aldehyde or bisulfite adduct at R4 in GC583 or GC587, respectively, with (C O)CONHcyclopropyl (GC591) led to remarkably decreased activity against all 3CLpros (>40-fold increases of IC50 values). The replacement of O(C O)NH at R2 in GC583 with a sulfonamide linkage (SO2NH) (GC772) led to a substantial decrease in activity against all 3CLpros. The replacement of m-Chloro benzyl group at R1 in GC772 with p-Chloro benzyl (GC774) did not affect the activity against feline coronavirus 3CLpro, but further decreased the activity against ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros.

These IC50 results indicate that the structural requirements of ferret, mink and feline coronavirus 3CLpros are similar, although ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros seem to share more similar structural requirements. The most potent 3CLpro against all 3CLpro was GC587 with IC50 values of 0.15, 0.29 and 0.59 μM for feline, ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpro, respectively.

3.2. Antiviral activity of the compounds against feline coronavirus replication in cell culture and cytotoxicity of the compounds

Since ferret and mink coronaviruses do not grow in cell culture, we examined the antiviral effects of the compounds against feline coronavirus to assess their effects in cell culture. The anti-feline coronavirus activity of these compounds has not been reported except for GC376, GC543 and GC551 (Kim et al., 2012, 2013, 2015). The EC50 values of the compounds ranged between 0.02 and 0.55 μM (Table 2 ), revealing that all compounds are cell-permeable and strongly inhibit the replication of feline coronavirus in cell culture. Overall, the antiviral effects of the tested compounds are in line with the results from the FRET assay, which confirms the findings of structure-activity relationship. No substantial cytotoxicity was observed for all compounds with CC50 values ranging between 115.57 ∼ >150 μM (Table 2). The in vitro therapeutic indices (CC50/EC50) for the compounds ranged between 272.7 ∼ >7500 (Table 2). These results indicate that these compounds have a wide safety margin in vitro.

Table 2.

Anti-feline coronavirus activity and cytotoxicity of the compounds in cell culture.

| Compound | GC376 | GC523 | GC543 | GC551 | GC583 | GC587 | GC591 | GC597 | GC772 | GC774 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 (μM)a | 0.05 ± 0.04 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.06 | 0.02 ± 0.06 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.55 ± 0.23 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.36 ± 0.12 | 0.39 ± 0.03 |

| CC50 (μM) | >150 | >150 | >150 | >150 | 115.6 ± 0.5 | 138.2 ± 6.64 | >150 | >150 | >150 | >150 |

| T.I | >3000 | >2143 | >2143 | >7500 | 1284 | 2764 | >273 | >3750 | >417 | >385 |

EC50 and CC50 indicate the 50% effective concentration and 50% cytotoxicity concentration, respectively. The in-vitro therapeutic indices (TI) were calculated by dividing CC50 by EC50. Values are the means and the standard error of the means from at least three independent experiments. The antiviral effects of GC376, GC543 and GC551 against feline coronavirus were previously reported by us (Kim et al., 2012, 2013, 2015), and their EC50 values were newly determined for this paper.

3.3. Multiple amino acid sequence alignment of 3CLpro of ferret, mink and feline coronaviruses

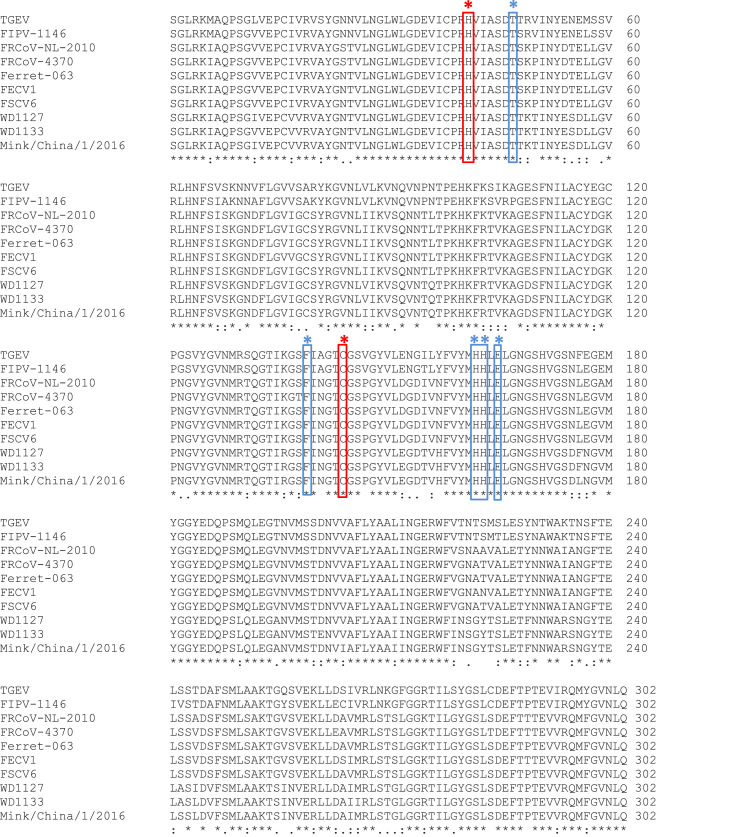

The homology of 3CLpro amino acid sequences among virus strains within each coronavirus is high, ranging 97.02–100% for ferret coronaviruses, 97.68–98.68% for mink coronaviruses and 95.7–100% for feline coronaviruses. The 3CLpro amino acid sequence homology between ferret and mink coronaviruses (83.44–86.09) is higher than that between ferret and feline coronaviruses (74.17–77.81%) or between mink and feline coronaviruses (71.52–73.51%), suggesting a closer relationship between ferret and mink coronaviruses. Regardless of some variations in the 3CLpro sequences among these coronaviruses, the catalytic residues and their locations (41H and 144C) are conserved across feline, ferret and mink coronaviruses (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Multiple sequence alignments of 3CLpro of ferret, mink and feline coronaviruses. Transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) Miller strain 3CLpro sequence was also included for comparative purposes. FIPV-1146 is a feline coronavirus; FRCoV-NL-2010, FRCoV-4370, Ferret-063, FECV1 and FSCV6 are ferret coronaviruses; WD1127, WD1333 and Mink/China/1/2016 are mink coronaviruses. The catalytic residues (H41 and C144) are in red boxes. The residues of TGEV 3CLpro that interact with GC376 are shown in blue boxes. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Furthermore, residues T47, F139, H162, H163 and E165 are conserved in all coronavirus strains (Fig. 2). These residues were previously identified to engage in hydrogen bonding or hydrophobic interactions with GC376 in the X-ray co-crystallography structure of TGEV 3CLpro-GC376 (Kim et al., 2012). TGEV (Miller strain) 3CLpro shares a high amino acid sequence homology with that of feline coronavirus 3CLpro (92.05–93.71%). Reflecting the highly conserved 3CLpro between these viruses, GC376 was previously shown to have potent and comparable inhibitory activity against both feline coronavirus and TGEV in cell culture and against their 3CLpros in the FRET assay (Kim et al., 2012).

3.4. Three-dimensional homology structural models for 3CLpro of ferret and mink coronaviruses

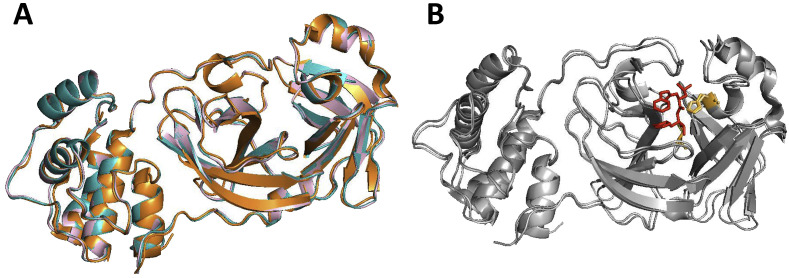

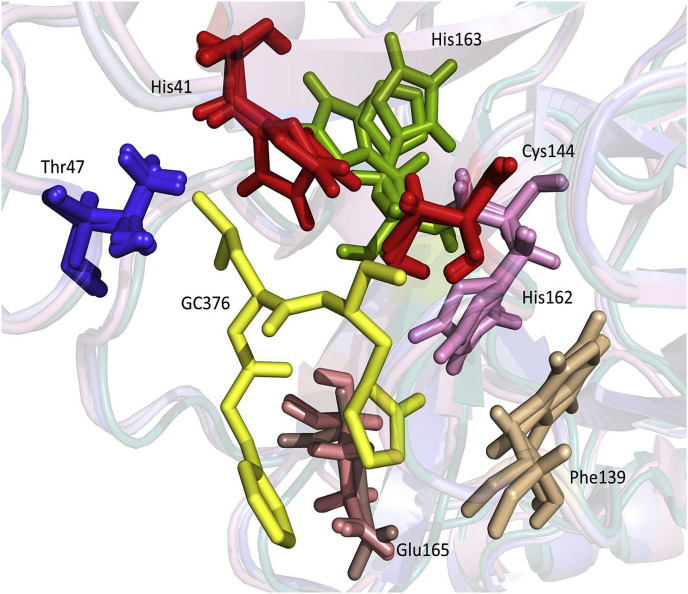

The homology-based 3CLpro structural models of ferret and mink coronaviruses superposed with a crystal structure of feline coronavirus 3CLpro are shown in Fig. 3 A. The RMSD for 124 superposed Cα atoms of residues 41–165 that contain the catalytic residues and the residues interacting with GC376 is 0.441 Å between feline and ferret coronavirus 3CLpros, 0.418 Å between feline and mink coronavirus 3CLpros, and 0.268 Å between ferret 3CLpro and mink coronavirus 3CLpros. These results suggest that feline, ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros closely resemble one another and that ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros align even more closely with each other. Superposition of the crystal structures of TGEV and feline coronavirus 3CLpros revealed an overall distance of 0.415 Å RMSD for 124 superposed Cα atoms between residues 41–165, which shows high structural homology between feline coronavirus and TGEV 3CLpros (Fig. 3B). The catalytic residues, H41 and C144, and the residues potentially interacting with GC376 based on the TGEV 3CLpro-GC376 complex crystal structure were found to be closely aligned in feline, ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 3.

Three-dimensional homology structure models of ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros. A. Ferret coronavirus and mink coronavirus 3CLpros were modelled using I-TASSER (Yang et al., 2015) and superposed with a crystal structure of feline coronavirus 3CLpro (PDB ID: 4ZRO). B. Crystal structures of feline coronavirus 3CLpro (PDB ID: 4ZRO) and TGEV (PDB ID: 4F40) were superposed. The crystal structure of TGEV-GC376 complex was previously reported by us (Kim et al., 2012). GC376, indicated as red stick, is shown in the active site of the superposed 3CLpro. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig. 4.

The superposed residues in the catalytic site of feline, ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros. A yellow stick represents GC376. The catalytic residues, H41 and C144, are shown in red. The five residues that interact with GC376 in the crystal structure of TGEV-GC376 complex are shown in various colors. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

Coronaviruses are a diverse family of viruses that infect animals and humans. However, the overall structure and function of 3CLpro are conserved among coronaviruses, which suggests that development of protease inhibitors broadly active against multiple coronaviruses may be feasible. A number of studies have been published on coronavirus 3CLpro inhibitors but previous reports have largely focused on SARS-coronavirus (Deng et al., 2014; Jacobs et al., 2013; Konno et al., 2013) and more recently on MERS-coronavirus, and only a few studies are available on 3CLpro inhibitors for multiple coronaviruses. The 3CLpro inhibitors that are active against two or more coronaviruses have been reported by our and other groups (Kim et al., 2012, 2016b; Prior et al., 2013) (reviewed in (Hilgenfeld, 2014). We have previously shown that GC376, a reversible inhibitor of 3CLpro, is efficacious in treating cats with experimental (Kim et al., 2016b) or naturally-occurring FIP (Pedersen et al., 2018). This inhibitor is also active against human and animal coronaviruses and other viruses that encode 3C protease or 3CLpro in vitro, including viruses in the Caliciviridae or Picornaviridae families (Kim et al., 2012, 2015, 2016b). In this study, we evaluated the activity of a focused library of 3CLpro inhibitors including GC376 against ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros, as well as feline coronavirus 3CLpro, to investigate the relationship between structure and activity of these inhibitors for these viruses.

Our structure-activity relationship study using the FRET assay showed that, in general, the tested compounds have similar activities against feline, ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros. In prior reports, we demonstrated that R3 variations (Leu or Cha) in our dipeptidyl compound series significantly affect the activity against human norovirus 3CLpro (Galasiti Kankanamalage et al., 2015). However, in this study, Leu or Cha at R3 did not lead to significant difference in the activity against coronavirus 3CLpros (Table 1). Substitution of a benzyl group at R1 with m-Chloro benzyl group in the compounds with bisulfide adduct warhead resulted in increased activities against all 3CLpros, and this was also observed in compounds against human norovirus 3CLpros in enzyme and cell based assays (Galasiti Kankanamalage et al., 2015). We have previously reported that compounds with a bisulfite adduct warhead are converted to the precursor aldehyde form (Kim et al., 2012), and that the bisulfite adducts and their aldehyde forms have comparable inhibitory activity against viral replication or 3CLpro (Kim et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2015). The present study also shows the bisulfite adducts (GC551 and GC587) have similar or slightly higher activity than their aldehyde counterparts (GC543 and GC583, respectively) against all 3CLpros. However, the replacement of aldehyde or bisulfite adduct with α-ketoamide warhead, (C O)CONHcyclohexyl (GC523) or (C O)CONHcyclopropyl (GC591), at R4 resulted in a marginal (GC523) or marked reduction (GC591) in the activity against these coronavirus 3CLpros (Table 1). These results suggest these α-ketoamide groups as a warhead are generally less tolerated than aldehyde or bisulfide adduct for these coronavirus 3CLpros. Previously, we found that ketoamide groups as a warhead are associated with reduced activity against human norovirus 3CLpro (Mandadapu et al., 2012), but not against some picornavirus 3CLpros (Kim et al., 2016a), compared to aldehyde or bisulfite counterparts. Lastly, the importance of a carboxyl group at R2 was demonstrated by the substantial decrease in the activity against all three 3CLpros when it was changed to a sulfonyl group (Table 1).

The results from this study show that the structural requirement of 3CLpro inhibition is similar among feline, ferret and mink coronaviruses, and ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpro share more similarity in their requirements. This close relationship between ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros may be explained in part by a higher amino acid homology between ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros (83.44–86.09%), compared to that between ferret (or mink) and feline coronavirus 3CLpros (71.52–77.81%). However, despite the differences in the activities of the compounds against these 3CLpros, it is notable that the compounds with strong inhibitory activity against feline coronavirus 3CLpro, including GC376, also exhibit potent activity against ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros with sub- or low micromolar IC50 values in the FRET assay. Among those compounds, GC587 exhibited most potent inhibition against all three 3CLpros with EC50 of 0.15–0.6 μM. GC587 is a variation of GC376 with modifications at R1 and R3, which is a further optimized compound toward human norovirus 3CLpro (Galasiti Kankanamalage et al., 2015).

The close relationship between feline, ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros is also shown by the structural models of ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros. These constructed 3CLpro models closely overlap with the crystal structure of feline coronavirus 3CLpro in the overall structure and in the active site topography (Fig. 3A and B and Fig.4), revealing the highly conserved nature of 3CLpro among these viruses. Previously, we identified five residues in TGEV 3CLpro that interact with GC376 in a crystallographic study of TGEV 3CLpro-GC376 complex (Kim et al., 2012). TGEV 3CLpro has a very high amino acid homology of over 92% with feline coronavirus 3CLpro, and GC376 exhibits comparable antiviral activity against both viruses (Kim et al., 2012). Multiple sequence alignments of 3CLpros of TGEV, feline, ferret and mink coronaviruses revealed that these amino acids, as well as the catalytic residues C144 and H41, are conserved at the same positions. When the crystal structures of TGEV and feline coronavirus 3CLpros and the structural models of ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros were superposed, the residues that are likely to interact with GC376 are positioned close together (Fig. 4), which may explain the potent activity of GC376 against these coronavirus 3CLpros.

One of the challenges in developing antiviral drugs for ferret and mink coronaviruses is the fastidious nature of these viruses in cell culture, which prevents the testing of the compound against virus replication in cell culture system. Therefore, we evaluated the antiviral activity of the compounds against feline coronavirus in cell culture. The antiviral activities of the compounds are generally in line with the results of the FRET assay with low cytotoxicity, which indicate they are cell-permeable and have a wide margin of in vitro safety. It is worth noting that several compounds, including GC376, an inhibitor with a demonstrated therapeutic potential in cats with FIP, also exhibited strong inhibitory activity against ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros. These results suggest that GC376 or its derivatives may have the potential to be developed as antiviral drugs for feline, ferret and mink coronavirus infections. Thus, further research on the pharmacokinetics, efficacy and safety in ferrets and minks is warranted.

In conclusion, we expressed feline, ferret and mink coronavirus 3CLpros and investigated the structure-function of a focused library of 3CLpro inhibitors against these coronavirus 3CLpros. Using the FRET assay, we identified compounds that displayed potent inhibitory activities against all three coronavirus 3CLpros. The findings in this study provide support for targeting 3CLpro for development of effective inhibitors broadly acting against feline, ferret and mink coronaviruses.

Acknowledgements

This work was generously supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01AI130092) and Morris Animal Foundation, Denver, CO (D14FE-012 and D16FE-512). We thank David George for technical assistance.

References

- Adams M.J., Lefkowitz E.J., King A.M.Q., Harrach B., Harrison R.L., Knowles N.J., Kropinski A.M., Krupovic M., Kuhn J.H., Mushegian A.R., Nibert M., Sabanadzovic S., Sanfacon H., Siddell S.G., Simmonds P., Varsani A., Zerbini F.M., Gorbalenya A.E., Davison A.J. Changes to taxonomy and the international code of virus classification and nomenclature ratified by the international committee on taxonomy of viruses (2017) Arch. Virol. 2017;162:2505–2538. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adedeji A.O., Sarafianos S.G. Antiviral drugs specific for coronaviruses in preclinical development. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2014;8:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autieri C.R., Miller C.L., Scott K.E., Kilgore A., Papscoe V.A., Garner M.M., Haupt J.L., Bakthavatchalu V., Muthupalani S., Fox J.G. Systemic coronaviral disease in 5 ferrets. Comp. Med. 2015;65:508–516. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker E.N., Tasker S., Gruffydd-Jones T.J., Tuplin C.K., Burton K., Porter E., Day M.J., Harley R., Fews D., Helps C.R., Siddell S.G. Phylogenetic analysis of feline coronavirus strains in an epizootic outbreak of feline infectious peritonitis. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2013;27:445–450. doi: 10.1111/jvim.12058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belser J.A., Katz J.M., Tumpey T.M. The ferret as a model organism to study influenza A virus infection. Dis. Model. Mech. 2011;4:575–579. doi: 10.1242/dmm.007823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H.W., Egberink H.F., Halpin R., Spiro D.J., Rottier P.J. Spike protein fusion Peptide and feline coronavirus virulence. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012;18:1089–1095. doi: 10.3201/eid1807.120143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang K.O., Takahashi D., Prakash O., Kim Y. Characterization and inhibition of norovirus proteases of genogroups I and II using a fluorescence resonance energy transfer assay. Virology. 2012;423:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq E. Potential antivirals and antiviral strategies against SARS coronavirus infections. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2006;4:291–302. doi: 10.1586/14787210.4.2.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano W.L. DeLano Scientific LLC; San Carlos, CA: 2010. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System.http://www.pymol.org [Google Scholar]

- Deng X., Agnihothram S., Mielech A.M., Nichols D.B., Wilson M.W., StJohn S.E., Larsen S.D., Mesecar A.D., Lenschow D.J., Baric R.S., Baker S.C. A chimeric virus-mouse model system for evaluating the function and inhibition of papain-like proteases of emerging coronaviruses. J. Virol. 2014;88:11825–11833. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01749-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galasiti Kankanamalage A.C., Kim Y., Damalanka V.C., Rathnayake A.D., Fehr A.R., Mehzabeen N., Battaile K.P., Lovell S., Lushington G.H., Perlman S., Chang K.O., Groutas W.C. Structure-guided design of potent and permeable inhibitors of MERS coronavirus 3CL protease that utilize a piperidine moiety as a novel design element. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;150:334–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galasiti Kankanamalage A.C., Kim Y., Rathnayake A.D., Damalanka V.C., Weerawarna P.M., Doyle S.T., Alsoudi A.F., Dissanayake D.M.P., Lushington G.H., Mehzabeen N., Battaile K.P., Lovell S., Chang K.O., Groutas W.C. Structure-based exploration and exploitation of the S4 subsite of norovirus 3CL protease in the design of potent and permeable inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017;126:502–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galasiti Kankanamalage A.C., Kim Y., Weerawarna P.M., Uy R.A., Damalanka V.C., Mandadapu S.R., Alliston K.R., Mehzabeen N., Battaile K.P., Lovell S., Chang K.O., Groutas W.C. Structure-guided design and optimization of dipeptidyl inhibitors of norovirus 3CL protease. Structure-activity relationships and biochemical, X-ray crystallographic, cell-based, and in vivo studies. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:3144–3155. doi: 10.1021/jm5019934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner M.M., Ramsell K., Morera N., Juan-Salles C., Jimenez J., Ardiaca M., Montesinos A., Teifke J.P., Lohr C.V., Evermann J.F., Baszler T.V., Nordhausen R.W., Wise A.G., Maes R.K., Kiupel M. Clinicopathologic features of a systemic coronavirus-associated disease resembling feline infectious peritonitis in the domestic ferret (Mustela putorius) Vet. Pathol. 2008;45:236–246. doi: 10.1354/vp.45-2-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnirs K., Quinton J.F., Dally C., Nicolier A., Ruel Y. Cerebral pyogranuloma associated with systemic coronavirus infection in a ferret. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2016;57:36–39. doi: 10.1111/jsap.12377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorham J.R., Evermann J.F., Ward A., Pearson R., Shen D., Hartsough G.R., Leathers C. Detection of coronavirus-like particles from mink with epizootic catarrhal gastroenteritis. Can. J. Vet. Res. 1990;54:383–384. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham E., Lamm C., Denk D., Stidworthy M.F., Carrasco D.C., Kubiak M. Systemic coronavirus-associated disease resembling feline infectious peritonitis in ferrets in the UK. Vet. Rec. 2012;171:200–201. doi: 10.1136/vr.e5652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gretebeck L.M., Subbarao K. Animal models for SARS and MERS coronaviruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2015;13:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Have P., Moving V., Svansson V., Uttenthal A., Bloch B. Coronavirus infection in mink (Mustela vison). Serological evidence of infection with a coronavirus related to transmissible gastroenteritis virus and porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Vet. Microbiol. 1992;31:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(92)90135-G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgenfeld R. From SARS to MERS: crystallographic studies on coronaviral proteases enable antiviral drug design. FEBS J. 2014;281:4085–4096. doi: 10.1111/febs.12936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J., Grum-Tokars V., Zhou Y., Turlington M., Saldanha S.A., Chase P., Eggler A., Dawson E.S., Baez-Santos Y.M., Tomar S., Mielech A.M., Baker S.C., Lindsley C.W., Hodder P., Mesecar A., Stauffer S.R. Discovery, synthesis, and structure-based optimization of a series of N-(tert-Butyl)-2-(N-arylamido)-2-(pyridin-3-yl) acetamides (ML188) as potent noncovalent small molecule inhibitors of the Severe Acute respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) 3CL protease. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:534–546. doi: 10.1021/jm301580n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Kankanamalage A.C., Damalanka V.C., Weerawarna P.M., Groutas W.C., Chang K.O. Potent inhibition of enterovirus D68 and human rhinoviruses by dipeptidyl aldehydes and alpha-ketoamides. Antivir. Res. 2016;125:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Liu H., Galasiti Kankanamalage A.C., Weerasekara S., Hua D.H., Groutas W.C., Chang K.O., Pedersen N.C. Reversal of the Progression of Fatal Coronavirus Infection in Cats by a Broad-Spectrum Coronavirus Protease Inhibitor. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Lovell S., Tiew K.C., Mandadapu S.R., Alliston K.R., Battaile K.P., Groutas W.C., Chang K.O. Broad-spectrum antivirals against 3C or 3C-like proteases of picornaviruses, noroviruses, and coronaviruses. J. Virol. 2012;86:11754–11762. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01348-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Mandadapu S.R., Groutas W.C., Chang K.O. Potent inhibition of feline coronaviruses with peptidyl compounds targeting coronavirus 3C-like protease. Antivir. Res. 2013;97:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Shivanna V., Narayanan S., Prior A.M., Weerasekara S., Hua D.H., Kankanamalage A.C., Groutas W.C., Chang K.O. Broad-spectrum inhibitors against 3C-Like proteases of feline coronaviruses and feline caliciviruses. J. Virol. 2015;89:4942–4950. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03688-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konno S., Thanigaimalai P., Yamamoto T., Nakada K., Kakiuchi R., Takayama K., Yamazaki Y., Yakushiji F., Akaji K., Kiso Y., Kawasaki Y., Chen S.E., Freire E., Hayashi Y. Design and synthesis of new tripeptide-type SARS-CoV 3CL protease inhibitors containing an electrophilic arylketone moiety. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:412–424. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V., Jung Y.S., Liang P.H. Anti-SARS coronavirus agents: a patent review (2008 - present) Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2013;23:1337–1348. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2013.823159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen A.E., Gorham J.R. A new mink enteritis: an initial report. Vet. Med. Small Anim. Clin. 1975;70:291–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T.C., Yoshizaki S., Kataoka M., Doan Y.H., Ami Y., Suzaki Y., Nakamura T., Takeda N., Wakita T. Determination of ferret enteric coronavirus genome in laboratory ferrets. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017;23:1568–1570. doi: 10.3201/eid2309.160215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licitra B.N., Millet J.K., Regan A.D., Hamilton B.S., Rinaldi V.D., Duhamel G.E., Whittaker G.R. Mutation in spike protein cleavage site and pathogenesis of feline coronavirus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013;19:1066–1073. doi: 10.3201/eid1907.121094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann D.M., Eshar D., Schumacher L.L., Almes K.M., Rankin A.J. Pyogranulomatous panophthalmitis with systemic coronavirus disease in a domestic ferret (Mustela putorius furo) Vet. Ophthalmol. 2016;19:167–171. doi: 10.1111/vop.12274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandadapu S.R., Gunnam M.R., Tiew K.C., Uy R.A., Prior A.M., Alliston K.R., Hua D.H., Kim Y., Chang K.O., Groutas W.C. Inhibition of norovirus 3CL protease by bisulfite adducts of transition state inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:62–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandadapu S.R., Weerawarna P.M., Gunnam M.R., Alliston K.R., Lushington G.H., Kim Y., Chang K.O., Groutas W.C. Potent inhibition of norovirus 3CL protease by peptidyl alpha-ketoamides and alpha-ketoheterocycles. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:4820–4826. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandadapu S.R., Weerawarna P.M., Prior A.M., Uy R.A.Z., Aravapalli S., Alliston K.R., Lushington G.H., Kim Y., Hua D.H., Chang K.-O., Groutas W.C. Macrocyclic inhibitors of 3C and 3C-like proteases of picornavirus, norovirus, and coronavirus. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:3709–3712. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliam H., Li W., Uludag M., Squizzato S., Park Y.M., Buso N., Cowley A.P., Lopez R. Analysis tool web services from the EMBL-EBI. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W597–W600. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michimae Y., Mikami S., Okimoto K., Toyosawa K., Matsumoto I., Kouchi M., Koujitani T., Inoue T., Seki T. The first case of feline infectious peritonitis-like pyogranuloma in a ferret infected by coronavirus in Japan. J. Toxicol. Pathol. 2010;23:99–101. doi: 10.1293/tox.23.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen N.C. An update on feline infectious peritonitis: virology and immunopathogenesis. Vet. J. 2014;201:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen N.C., Kim Y., Liu H., Galasiti Kankanamalage A.C., Eckstrand C., Groutas W.C., Bannasch M., Meadows J.M., Chang K.O. Efficacy of a 3C-like protease inhibitor in treating various forms of acquired feline infectious peritonitis. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2018;20(4):378–392. doi: 10.1177/1098612X17729626. 1098612X17729626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen N.C., Liu H., Dodd K.A., Pesavento P.A. Significance of coronavirus mutants in feces and diseased tissues of cats suffering from feline infectious peritonitis. Viruses. 2009;1:166–184. doi: 10.3390/v1020166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen N.C., Liu H., Scarlett J., Leutenegger C.M., Golovko L., Kennedy H., Kamal F.M. Feline infectious peritonitis: role of the feline coronavirus 3c gene in intestinal tropism and pathogenicity based upon isolates from resident and adopted shelter cats. Virus Res. 2012;165:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior A.M., Kim Y., Weerasekara S., Moroze M., Alliston K.R., Uy R.A., Groutas W.C., Chang K.O., Hua D.H. Design, synthesis, and bioevaluation of viral 3C and 3C-like protease inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:6317–6320. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.09.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provacia L.B., Smits S.L., Martina B.E., Raj V.S., Doel P.V., Amerongen G.V., Moorman-Roest H., Osterhaus A.D., Haagmans B.L. Enteric coronavirus in ferrets, The Netherlands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011;17:1570–1571. doi: 10.3201/eid1708.110115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed L.J., Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Terada Y., Minami S., Noguchi K., Mahmoud H.Y.A.H., Shimoda H., Mochizuki M., Une Y., Maeda K. Genetic characterization of coronaviruses from domestic ferrets, Japan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:284–287. doi: 10.3201/eid2002.130543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson A.P.D. A history of the ferret. J. Hist. Med. Allied Sci. VI. 1951:471–480. [Google Scholar]

- Vlasova A.N., Halpin R., Wang S., Ghedin E., Spiro D.J., Saif L.J. Molecular characterization of a new species in the genus Alphacoronavirus associated with mink epizootic catarrhal gastroenteritis. J. Gen. Virol. 2011;92:1369–1379. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.025353-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B.H., Kiupel M., West K.H., Raymond J.T., Grant C.K., Glickman L.T. Coronavirus-associated epizootic catarrhal enteritis in ferrets. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2000;217:526–530. doi: 10.2460/javma.2000.217.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise A.G., Kiupel M., Garner M.M., Clark A.K., Maes R.K. Comparative sequence analysis of the distal one-third of the genomes of a systemic and an enteric ferret coronavirus. Virus Res. 2010;149:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise A.G., Kiupel M., Maes R.K. Molecular characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with epizootic catarrhal enteritis (ECE) in ferrets. Virology. 2006;349:164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Xie W., Xue X., Yang K., Ma J., Liang W., Zhao Q., Zhou Z., Pei D., Ziebuhr J., Hilgenfeld R., Yuen K.Y., Wong L., Gao G., Chen S., Chen Z., Ma D., Bartlam M., Rao Z. Design of wide-spectrum inhibitors targeting coronavirus main proteases. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Yan R., Roy A., Xu D., Poisson J., Zhang Y. The I-TASSER Suite: protein structure and function prediction. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:7–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]