Abstract

The prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is increasing. The health care burden resulting from the multidisciplinary management of this complex disease is unknown. We assessed the total health care cost and resource utilization associated with a new NAFLD diagnosis, compared to controls with similar comorbidities. We used OptumLabs Data Warehouse, a large national administrative claims database with longitudinal health data of over 100 million individuals enrolled in private and Medicare Advantage health plans. We identified 152,064 adults with a first claim for NAFLD between 2010–2014, of which 108,420 were matched 1:1 by age, sex, metabolic comorbidities, length of follow-up, year of diagnosis, race, geographic region and insurance type to non-NAFLD contemporary controls from the OLDW database. Median follow-up time was 2.6 (range 1–6.5) years. The final study cohort consisted of 216,840 people with median age 55 (range 18–86) years, 53% female, 78% white. The total annual cost of care per NAFLD patient with private insurance was $7,804 (IQR $3,068–$18,688) for a new diagnosis and $3,789 (IQR $1,176–$10,539) for long-term management. These costs are significantly higher than the total annual costs of $2,298 (IQR $681–$6,580) per matched control with similar metabolic comorbidities but without NAFLD. The largest increases in healthcare utilization which may account for the increased costs in NAFLD compared to controls are represented by liver biopsies (RR=55.00, 95% CI 24.48–123.59), imaging (RR=3.95, 95% CI 3.77–4.15) and hospitalizations (RR=1.87, 95%CI 1.73–2.02).

Conclusions

The costs associated with the care for NAFLD independent of its metabolic comorbidities are very high, especially at first diagnosis. Research efforts should focus on identification of underlying determinants of use, sources of excess cost and development of cost-effective diagnostic tests.

Keywords: economic, burden, insurance, primary care

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common chronic liver disease in the Western countries, affecting 24%(1) to 45%(2) of the United States (US) population or 64–100 million people. Most (approximately 80%) patients with NAFLD have hepatic steatosis without inflammation, which is associated with a relatively low risk of fibrosis(3, 4) but does have strong correlation with cardiovascular disease, metabolic complications(5), and increased mortality compared to the general population(6). The remaining 20% of patients have nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which leads to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and other liver-related complications(7).

Given the increasing prevalence of NAFLD, the economic burden is undoubtedly considerable, but real-world data are scarce. US healthcare expenditures have steadily increased over the last decades and are projected to account for 20% of the economy by 2024(8, 9). The NAFLD epidemic wave could hasten this increase; therefore, assessment of its contribution to the economic burden and the major healthcare utilization drivers is imperative. In a recent study, Younossi et al used Markov modeling to estimate the annual direct healthcare costs at $1,612 per NAFLD patient(1). However, as the authors acknowledged, the models were constructed based on assumptions of NAFLD epidemiology, fibrosis progression rate, and incident complications, some of which were imputed from hepatitis C studies, resulting in uncertainty around many inputs. Another study conducted among NAFLD Medicare beneficiaries in 2010 estimated annual total medical charges per patient to be $3,608 for outpatient (10) and $36,289 for inpatient care(11). While this provided direct cost data, it included an older population, whereas NAFLD is mostly prevalent in the middle age group (45–64 years).

Moreover, as the clinical care of NAFLD subjects is directed not only by liver disease but also by the coexistent comorbidities, such as diabetes, hypertension or cardiovascular disease, previous studies did not isolate the specific contribution of NAFLD to the healthcare burden from that of other metabolic diseases.

We therefore assessed the total health care cost and utilization of patients with NAFLD, compared to a control population with similar comorbidities, among commercially-insured and Medicare Advantage beneficiaries, using a large administrative claims database. The dataset used in this study, OptumLabs Data Warehouse (OLDW), is uniquely suited to study NAFLD burden as it includes over 100 million people across the US, with greatest representation the South, where the prevalence of NAFLD is highest. It includes adults of all ages, thereby updating and completing previously published data that focused on Medicare beneficiaries. The estimation of direct costs and utilization offers better understanding about the financial implications of NAFLD for patients and the healthcare system, and helps identify areas in need of better resource allocation, standardized management, and greater efficiencies in delivered care.

METHODS

Data source

This was a retrospective analysis of medical and pharmacy claims data from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse (OLDW), a large national administrative claims database which includes longitudinal health data of more than 100 million individuals enrolled in private and Medicare Advantage health plans since 1994(12, 13), which offers an excellent platform to trend the cost of care(14–16) and private health insurance. The population is diversely distributed in age, race and geographical location in all 50 states. The database includes deidentified enrollee information (sex, age, race/ethnicity, region of residency, insurance plan); medical claims (including diagnosis and procedure codes, site of service codes, provider specialty codes and total paid amounts); and pharmacy claims. The study involved analysis of preexisting de-identified data, thus was exempt from Institutional Review Board approval.

Study population

We identified all patients with a first medical claim for NAFLD using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 codes ICD 9-CM 571.5 (cirrhosis of the liver without mention of alcohol), 571.8 (other chronic nonalcoholic liver disease), 571.9 (unspecified chronic liver disease without mention of alcohol) between 2010 and 2014. From this cohort, we excluded subjects diagnosed with other liver diseases, including viral, alcoholic, cholestatic liver disease, etc (ICD 9-CM codes in eTable 1). Subjects were classified as NAFLD cases if no alternative liver disease was identified prior to the index NAFLD diagnosis or during follow-up. This diagnostic algorithm correctly identified true NAFLD cases with 85% accuracy in a previously published retrospective population-based cohort(5). The service date of the first observed claim for NAFLD was defined as the index date for patients in the NAFLD cohort.

A control cohort was assembled by identifying patients with at least one medical claim for an office visit during 2010–2014 and no medical claims with diagnosis codes for NAFLD or other liver diseases during the study period. The controls were matched 1:1 on age, sex, race, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, length of follow-up, year of diagnosis, geographic region and insurance type. The index date for the control cohort was assigned to a randomly chosen office visit during the identification period.

All subjects were continuously enrolled in the health plan with medical and pharmacy benefits for at least 1 year before and 1 year after their index date. The subjects were followed until disenrollment from the healthcare plan or study end-date (June 2016). eFigure 1 illustrates the study scheme.

Covariates and outcomes of interest

Comorbidities associated with NAFLD including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia and cardiovascular disease were identified using the diagnostic codes listed in eTable 2 in the Supplement. NAFLD subjects and controls were matched on these comorbidities at the index date in order to maximize the association of cost and utilization with NAFLD and not with its comorbidities. Outcomes of interest were direct costs and healthcare utilization, such as office visits, hospitalizations, emergency department (ED) visits, as well as tests and procedures attributable to liver disease: liver biopsy, imaging (ultrasound, abdominal CT and MRI), and laboratory tests (eTable 3). The outcomes were measured at 3 different time points in reference to the index date of NAFLD diagnosis or matching: 1 year before, 1 and 5 years after.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics (age, sex, race, census region, year of diagnosis, comorbidities, insurance type) were described using mean (standard deviation) or count (percentage) as appropriate. Unadjusted utilization rates and total costs of care were compared between NAFLD cases and controls for 1-year prior to diagnosis date, 1-year post diagnosis date and 5-year post diagnosis date. Total cost of care included both medical (inpatient and outpatient) claims and outpatient pharmacy claims. Total healthcare costs were reported per patient and were inflation-adjusted to 2015 US dollars using Consumer Price Index(17). Healthcare resource utilization was identified as rates (number of events per 1,000 patients) and rate ratios between 1 year post versus 1 year pre-index date and NAFLD versus controls. Data was analyzed separately for privately insured and Medicare Advantage subjects. Statistical analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute; Cary, NC).

RESULTS

We identified 350,406 people with a first diagnosis of NAFLD between 2010–2014, of which 165,281 were excluded for lack of medical and pharmacy coverage at least 1 year prior to and 1 year after the index NAFLD diagnosis. Additionally, 33,061 people were excluded due to concurrent liver diseases other than NAFLD. From the remaining cohort of 152,064 people with incident NAFLD, 108,420 were matched 1:1 by age, sex, metabolic comorbidities, length of follow-up, year of diagnosis, race, geographic region and insurance type to non-NAFLD contemporary controls from the OLDW database. We were unable to match all NAFLD patients to controls due to the multitude of matching variables. The final study cohort consisted of 216,840 people with median age 55 (range 18–86) years, 53% female and 78% white (Table 1). Median follow-up time was 2.6 (range 1–6.5) years for both NAFLD and controls.

Table 1.

Characteristics of NAFLD patients and matched controls.

| Controls N=108,420 |

NAFLD N=108,420 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 55 (45–65) | 55 (45–65) |

| Age groups (years) | ||

| 18–34 | 9,341 (8.6%) | 9,341 (8.6%) |

| 35–54 | 43,599 (40.2%) | 43,599 (40.2%) |

| 55–64 | 28,147 (26.0%) | 28,147 (26.0%) |

| ≥65 | 27,333 (25.2%) | 27,333 (25.2%) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 57,167 (52.7%) | 57,167 (52.7%) |

| Male | 51,253 (47.3%) | 51,253 (47.3%) |

| Index year | ||

| 2010 | 19,663 (18.1%) | 19,663 (18.1%) |

| 2011 | 19,890 (18.3%) | 19,890 (18.3%) |

| 2012 | 22,538 (20.8%) | 22,538 (20.8%) |

| 2013 | 22,111 (20.4%) | 22,111 (20.4%) |

| 2014 | 24,218 (22.3%) | 24,218 (22.3%) |

| Region | ||

| Midwest | 27,230 (25.1%) | 27,230 (25.1%) |

| Northeast | 12,826 (11.8%) | 12,826 (11.8%) |

| South | 55,269 (51.0%) | 55,269 (51.0%) |

| West | 13,095 (12.1%) | 13,095 (12.1%) |

| Race | ||

| White | 84,613 (78.0%) | 84,613 (78.0%) |

| Asian | 2,742 (2.5%) | 2,742 (2.5%) |

| Black | 8,508 (7.8%) | 8,508 (7.8%) |

| Hispanic | 11,051 (10.2%) | 11,051 (10.2%) |

| Unknown | 1,506 (1.4%) | 1,506 (1.4%) |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Hypertension | 66064 (60.9%) | 66064 (60.9%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 69549 (64.1%) | 69549 (64.1%) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 33418 (30.8%) | 33418 (30.8%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 30906 (28.5%) | 30906 (28.5%) |

| Insurance type | ||

| Commercial | 76697 (70.7%) | 76697 (70.7%) |

| Medicare Advantage | 31723 (29.3%) | 31723 (29.3%) |

Healthcare costs in NAFLD

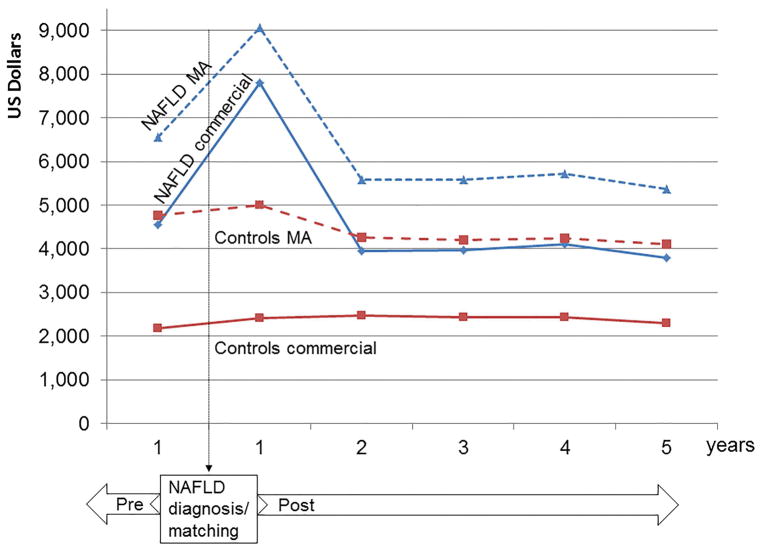

Figure 1 shows the annual total health care costs of NAFLD subjects compared to matched controls, in reference to the date of index (first) diagnosis or matching, respectively. We show the total annual costs starting 1 year prior to the index date, to allow comparisons within the peri-diagnosis period (1 year pre- versus 1 year post), as well as long-term annual costs, reflective of disease monitoring and management of comorbidities. For both NAFLD subjects and controls, the costs of care for Medicare Advantage enrollees were considerably higher than for subjects with private insurance.

Figure 1. Annual total health care costs of NAFLD patients compared to matched controls in reference to the date of index (first) NAFLD diagnosis or matching, respectively.

NAFLD MA: NAFLD patients with Medicare Advantage; NAFLD commercial: NAFLD patients with commercial insurance; controls MA: matched controls with Medicare Advantage; controls commercial: matched controls with commercial insurance.

The costs were highest during the first year following the index NAFLD diagnosis, likely reflecting the costs of diagnosis and initial evaluation for NAFLD and its comorbidities. Specifically, among patients with commercial insurance the median cost of medical care during the year following NAFLD diagnosis increased by 72%, from $4,547 (IQR $1,648–$11,661) to $7,804 (IQR $3,068–$18,688). The median costs for Medicare Advantage enrollees with NAFLD increased by 38%, from $6,566 (IQR $3139–$14,787) during the year prior to NAFLD diagnosis to $9,062 (IQR $4,313–$20,765) during the year after diagnosis. For reference, the annual healthcare costs of non-NAFLD matched controls increased only by 5–10% after the index date, in line with the expected increase in annual rates.

The annual healthcare costs in the subsequent years were lower than the immediate peri-diagnosis period. Nevertheless, the annual costs for NAFLD patients remained considerably higher than those for matched controls. Specifically, at 5 years after NAFLD diagnosis, the median annual healthcare cost was $3,789 (IQR $1,176–$10,539) per NAFLD patient with commercial insurance and $2,298 (IQR $681–$6,580) per control. Among the Medicare Advantage population, the median annual healthcare cost was $5,363 (IQR $2,402–$12,515) per NAFLD patient and $4,111 (IQR $1,677–$9,958) per control.

Consequently, the median cumulative healthcare costs 5 years following the index NAFLD diagnosis for an individual with commercial insurance were nearly 80% higher than a control with similar age and comorbidities: $30,994 (IQR $14,688–$64,972) versus $17,345 (IQR $7,198–$38,713). The median cumulative 5-year costs for a NAFLD individual with Medicare Advantage were 42% higher than controls: $39,588 (IQR $20,950–$71,226) versus $27,777 (IQR $14,192–$54,666).

Healthcare utilization in NAFLD

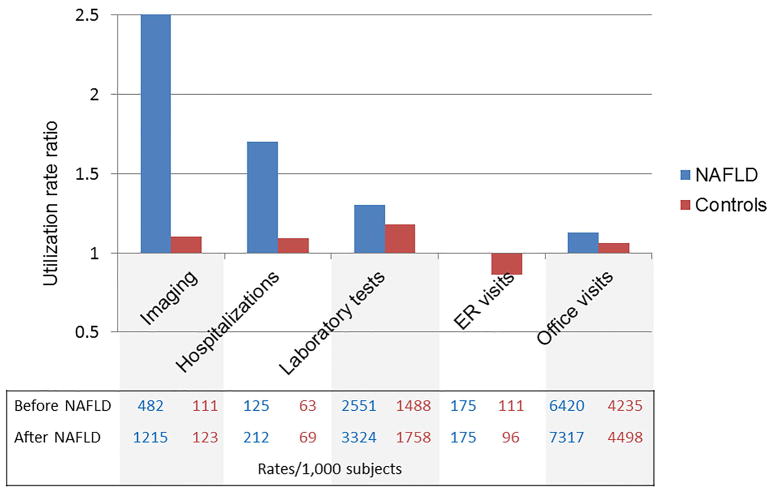

To explore what healthcare utilization parameters may account for higher cost of care in NAFLD, we assessed several utilization indices at similar timeframes used for the cost estimates: peri-diagnosis and at 5 years after the index diagnosis. In reference to the year prior to the index date, most utilization parameters during the following year increased slightly among controls, as expected with the passage of time and aging, but the rise was markedly higher among patients newly diagnosed with NAFLD. The largest increase in utilization (rate/1,000 patients) after NAFLD diagnosis was liver biopsy from 5.5 to 28.8, followed by liver-related imaging and all-cause hospitalizations. There were smaller, but consistent, increases in laboratory testing episodes, ED visits and office visits. Figure 2A demonstrates the relative change in utilization rates among commercially insured patients with NAFLD when compared to controls. Patients with NAFLD experienced substantial increases in utilization of imaging (RR=2.52, 95%CI 2.49–2.56), hospitalizations (RR=1.69, 95%CI 1.64–1.75) and laboratory tests (RR=1.30, 95%CI 1.29–1.32) when compared to controls, in whom the relative increases were minimal. Among the most commonly used imaging modalities, MRI use showed the highest increase after diagnosis (RR=3.42, 95%CI 3.20–3.66), followed by ultrasound (RR=2.77, 95%CI 2.71–2.82) and CT (RR=2.57, 95%CI 2.52–2.62) (eTable 5).

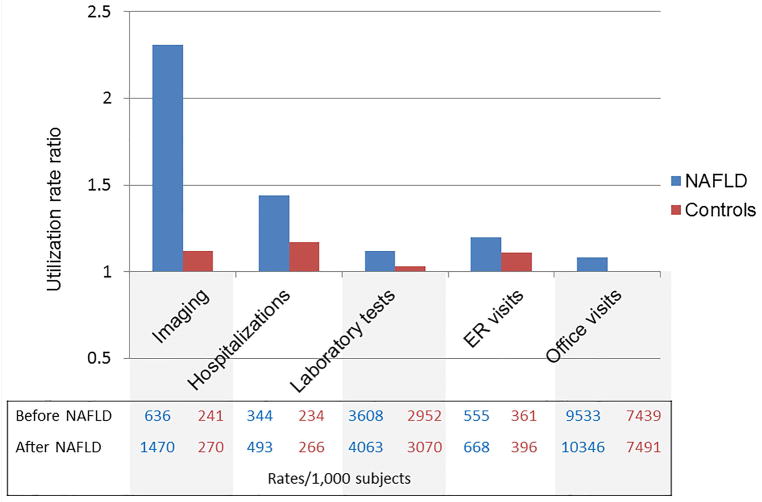

Figure 2. The relative change in utilization rates after a new diagnosis of NAFLD compared to matched controls. A. Commercial insurance enrollees. B. Medicare Advantage enrollees.

The bars represent utilization rate ratios (rates 1 year after diagnosis/matching/ rates 1 year prior to diagnosis/matching). The corresponding absolute rates are presented in the Table below the bars.

The trends were similar among the 63,442 subjects with Medicare Advantage insurance, in whom the largest increases in utilization after NAFLD diagnosis were due to increased rates of liver biopsy, imaging and hospitalizations (Figure 2B and eTable 5).

Longitudinal follow-up data at 5 years after NAFLD diagnosis/matching were available in a subset of 20,840 individuals. The cumulative healthcare utilization remained significantly higher among patients with NAFLD compared to controls (Table 2). Among commercially insured beneficiaries, liver biopsies continued to account for the largest difference in utilization in NAFLD compared to controls (RR=55.00, 95% CI 24.48–123.59), followed by imaging (RR=3.95, 95% CI 3.77–4.15) and hospitalizations (RR=1.87, 95%CI 1.73–2.02). Among the Medicare Advantage beneficiaries, the largest differences in healthcare use with NAFLD were due to liver biopsies, imaging and ER visits.

Table 2.

Cumulative utilization rates per 1,000 patients at 5 years after NAFLD diagnosis.

| Controls | NAFLD | Rate ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Commercial insurance | |||

| N | 7464 | 7464 | |

| Liver biopsy | 0.8 | 44.2 | 55.00 (24.48, 123.59) |

| Imaging | 567.3 | 2243.2 | 3.95 (3.77, 4.15) |

| Ultrasound | 144.0 | 762.7 | 5.30 (4.95, 5.66) |

| Computer tomography | 287.5 | 1085.6 | 3.78 (3.54, 4.03) |

| Magnetic resonance imaging | 19.0 | 116.0 | 6.10 (4.94, 7.53) |

| Transient elastography | 0.0 | 0.4 | - |

| Laboratory tests | 8517.0 | 12380.5 | 1.45 (1.41, 1.49) |

| Hospitalizations | 263.1 | 492.4 | 1.87 (1.73, 2.02) |

| Outpatient visits | 22243.7 | 31078.8 | 1.40 (1.36, 1.43) |

| Emergency room visits | 328.5 | 402.7 | 1.23 (1.16, 1.30) |

| B. Medicare Advantage | |||

| N | 2956 | 2956 | |

| Liver biopsy | 1.0 | 25.0 | 24.67 (7.77, 78.34) |

| Imaging | 1167.1 | 3297.0 | 2.82 (2.64, 3.02) |

| Ultrasound | 182.3 | 879.2 | 4.82 (4.36, 5.33) |

| Computer tomography | 651.6 | 1758.4 | 2.70 (2.49. 2.92) |

| Magnetic resonance imaging | 36.2 | 126.5 | 3.50 (2.69, 4.55) |

| Transient elastography | 0.0 | 0.0 | - |

| Laboratory tests | 14740.2 | 17169.5 | 1.16 (1.10, 1.23) |

| Hospitalizations | 1041.6 | 1489.5 | 1.43 (1.32, 1.54) |

| Outpatient visits | 35903.9 | 45885.0 | 1.28 (1.23, 1.32) |

| Emergency room visits | 1724.0 | 2732.1 | 1.58 (1.48, 1.70) |

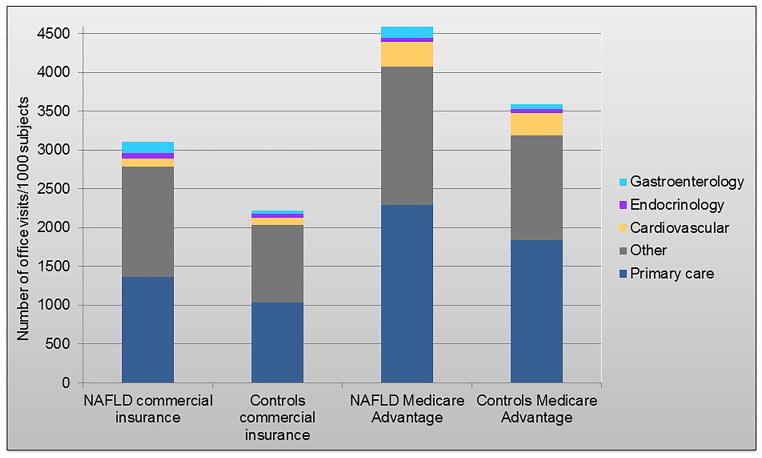

The average cumulative rate of overall outpatient office visits at 5 years after diagnosis was 40% higher among patients with NAFLD compared to controls: 31,079 versus 22,244 visits/1,000 patients. Only 4.6% of these visits were to gastroenterology specialists, while 46% were to primary care (Figure 3). The proportion of other specialty visits, such as endocrinology and cardiovascular diseases was similar between NAFLD and controls (2.4% and 3%, respectively), reflective of robust matching by comorbidity status during cohort selection. In the Medicare Advantage cohort, gastroenterology visits represented 3.0% of all visits among patients with NAFLD compared to 1.6% of all visits among controls.

Figure 3.

The average cumulative rate of overall outpatient office visits 5 years after diagnosis/matching and distribution by medical specialties of interest.

DISCUSSION

Using real world data from a large nationwide medical claims database, we show that the long-term cumulative healthcare cost of a NAFLD patient is 80% higher than that of a non-NAFLD control of similar age and metabolic comorbidities. The highest annual costs occur around a new diagnosis of NAFLD, reaching $7,804 and $9,062 per individual with private insurance and Medicare Advantage, respectively. Annual costs for long-term management decrease to $3,789 and $5,363 per individual with private insurance and Medicare Advantage, respectively, but remain considerably higher than controls. The largest increases in healthcare utilization which may account for the increased costs in NAFLD are represented by liver biopsies, imaging and hospitalizations. The large burden of NAFLD is managed predominantly by primary care physicians, while subspecialty visits in gastroenterology represent only 3–4.6% of the total office visits. These data highlight that, as the NAFLD burden will continue to increase(18), solutions are needed to promote innovative health care delivery platforms to reduce costs and to provide primary care physicians with the necessary strategies and resources to optimally manage this complex patient population.

The disease characteristics and the enormous clinical burden of NAFLD pose considerable challenges to the medical community, which extend beyond the hepatology field. In this cohort, a strikingly low proportion of the outpatient visits were represented by gastroenterology and hepatology. The overwhelming clinical burden of NAFLD is supported by general practitioners, who have a key role in the identification, risk stratification and timely referral for specialty care in NAFLD, but may be unfamiliar with the intricacies of the disease(19). The American Association for the Study of Liver Disease guidelines suggest vigilance for NAFLD, but do not provide well-defined screening recommendations for primary care providers and cost-effective methods of disease severity assessment(20). The lack of clear guidelines is due to uncertainties surrounding cost-effectiveness of diagnostic tests and long-term benefits of screening, which are areas in significant need of further research in the hepatology community. The current state of NAFLD diagnosis and disease severity assessment is based on combinations of several available tests which include laboratory studies, ultrasound, cross-sectional imaging, elastography and liver biopsy, the use of which is subject to individual practice patterns.

While the most cost-effective modality to estimate disease severity in NAFLD remains to be established(21), these data offer a much-needed synopsis of the real-world practice. The total costs soar by 72% in the first year after the initial NAFLD claim and reach exorbitant levels when compared to non-NAFLD controls. Increases in utilization corresponding to these costs were noted among all diagnostic modalities, but were dominated by imaging tests (with costs that vary between $200–3,000(22)), which increased 2.5-fold (1,215 per 1,000 patients). It has been recognized that using ultrasound to detect hepatic steatosis is not cost effective because clinically relevant fibrosis is present in no more than 11% of cases(23, 24). The utility of other modalities, including elastography, which is potentially more effective but more costly, has not yet been proven. Although liver biopsy is required to diagnose NASH, only patients at high risk require this evaluation. In this cohort, liver biopsy, with a cost that varies generally between $1,500–3,000(22) had the highest relative increase in use (5-fold), although the absolute rate of utilization remained low (29/1,000 patients). The utilization of labs for diagnosis (the least expensive but also least reliable alternative) increased by 30%. The exorbitant costs of care around the first diagnosis of NAFLD in this cohort, underline the acute need of more cost-effective methods of screening and disease severity assessment.

The annual healthcare costs for NAFLD remained extremely high beyond the initial peri-diagnosis period. The long-term annual costs of NAFLD management are almost double those of the matched cohort ($3,789 vs $2,298 per subject). Over the 5 years following the index diagnosis, NAFLD patients are subjected to abdominal imaging 4-fold more frequently than matched controls. Similarly, the rate of blood testing and outpatient visits is 45% and 39% higher, respectively. It is important to note that the relative cost difference between NAFLD and control patients was higher among the commercially insured (younger) population than it was among Medicare Advantage enrollees (where cost is largely driven by multimorbidity), suggesting that diagnosis of NAFLD at earlier age in the context of increasing NAFLD incidence in children and young adults leads to a higher cost differential at initial diagnosis. Moreover, diagnosis at an earlier age leads to longer follow-up time and monitoring for fibrosis progression or surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma. These data highlight the need for cost-effective measures to identify patients at high risk of disease progression (i.e. differentiating patients with NASH and/or fibrosis from simple steatosis).

Although robust direct comparisons of long-term costs in other liver diseases are not available, inferences from hepatitis C models estimating $90,127 life-time cost per patient treated with direct acting antiviral agents(25) allow estimations that the cost of NAFLD care is likely to surpass that of hepatitis C, especially in view of upcoming NASH therapies.

These data are an essential benchmark for future cost analyses in NAFLD, as several novel findings cover important gaps in the existing literature: 1) direct costs are estimated from a large, nationally-representative medical claims database. The annual direct cost per NAFLD patient is approximately 5-fold higher than previous estimates from US ($1,612.18) and European countries (€354–€1,163) that relied on Medicare data or derived from statistical modeling(1, 11). This is in part due to our ability to capture costs for commercially-insured adults who have heretofore been excluded from NAFLD studies despite comprising the majority of patients affected by the disease; 2) by using a matched cohort with similar metabolic comorbidities as reference, we can differentiate liver-related costs from those related to metabolic complications; 3) we evaluate the costs at multiple time points and show that the costs vary in reference to a new diagnosis; 4) we identify health care utilization in NAFLD management, which are important bench mark data for future cost-effectiveness analyses.

However, patients with Medicaid health coverage, the uninsured or those with NAFLD that remains undiagnosed are not captured in OLDW, thus prevalence estimates should not be extrapolated from this study. Similarly, societal costs, derived from absenteeism and caregiver burden, certainly add even further to the overall healthcare burden of NAFLD. As an inherent limitation of large claims databases, we did not have the opportunity to distinguish between clinically appropriate and redundant use of tests, impact on patient outcomes and sources of excess costs. Further work is needed to identify underlying determinants of use, how to avoid high use of low-value services and insufficient use of high-value services which can drive inefficient allocation of resources(26).

The care of NAFLD patients is expensive. As diagnostic methods and therapies for NAFLD become increasingly available, early detection of the millions of patients in the primary care setting, adequate risk stratification, subspecialty referral and monitoring, while taking into account cost-effectiveness, remains an enormous challenge. Research efforts should focus on development of high-value diagnostic tests to monitor for liver fibrosis progression at appropriate intervals, in a selected at-risk population, with the ultimate goal to improve quality of care for the individual patient, while being mindful of the effects on healthcare use and utilization.

Supplementary Material

Patients with a first claim for NAFLD diagnosis between 2010–2014 were identified. A control cohort was assembled by identifying patients with at least one medical claim for an office visit during 2010–2014 and no medical claims with diagnosis codes for NAFLD or other liver diseases during the study period. The controls were matched 1:1 on age, sex, race, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, length of follow-up, year of diagnosis, geographic region and insurance type. The index date represents the date of first NAFLD claim or a randomly chosen office visit during the identification period for the control cohort, respectively.

All subjects were continuously enrolled in the health plan with medical and pharmacy benefits for at least 1 year before and 1 year after their index date (those who did not meet this criterion were excluded). The subjects were followed until disenrollment from the healthcare plan or study end-date (June 2016).

Acknowledgments

Financial Support:

Alina M. Allen: Mayo Clinic Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery; American College of Gastroenterology Junior Faculty Development Award; and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health Award No. K23 DK115594.

Rozalina G. McCoy: Mayo Clinic Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery and by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health Award No. K23 DK114497.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- ED

emergency department

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- IQR

interquartile range

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- OLDW

OptumLabs Data Warehouse

- RR

relative risk

- US

United States

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

References

- 1.Younossi ZM, Blissett D, Blissett R, Henry L, Stepanova M, Younossi Y, Racila A, et al. The economic and clinical burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States and Europe. Hepatology. 2016;64:1577–1586. doi: 10.1002/hep.28785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams CD, Stengel J, Asike MI, Torres DM, Shaw J, Contreras M, Landt CL, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis among a largely middle-aged population utilizing ultrasound and liver biopsy: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:124–131. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh S, Allen AM, Wang Z, Prokop LJ, Murad MH, Loomba R. Fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver vs nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of paired-biopsy studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:643–654. e641–649. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.04.014. quiz e639–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rinella ME. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. Jama. 2015;313:2263–2273. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.5370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen AM, Terry TM, Larson JJ, Coward A, Somers VK, Kamath PS. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Incidence and Impact on Metabolic Burden and Death: a 20 Year-Community Study. Hepatology. 2017 doi: 10.1002/hep.29546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams LA, Lymp JF, St Sauver J, Sanderson SO, Lindor KD, Feldstein A, Angulo P. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:113–121. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matteoni CA, Younossi ZM, Gramlich T, Boparai N, Liu YC, McCullough AJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a spectrum of clinical and pathological severity. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1413–1419. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70506-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuchs VR. How and why US health care differs from that in other OECD countries. Jama. 2013;309:33–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.125458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartman M, Martin AB, Espinosa N, Catlin A The National Health Expenditure Accounts T. National Health Care Spending In 2016: Spending And Enrollment Growth Slow After Initial Coverage Expansions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018;37:150–160. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Younossi ZM, Zheng L, Stepanova M, Henry L, Venkatesan C, Mishra A. Trends in outpatient resource utilizations and outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:222–227. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sayiner M, Otgonsuren M, Cable R, Younossi I, Afendy M, Golabi P, Henry L, et al. Variables Associated With Inpatient and Outpatient Resource Utilization Among Medicare Beneficiaries With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease With or Without Cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:254–260. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Optum. In.

- 13.Wallace PJ, Shah ND, Dennen T, Bleicher PA, Crown WH. Optum Labs: building a novel node in the learning health care system. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:1187–1194. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thayer S, Bell C, McDonald CM. The Direct Cost of Managing a Rare Disease: Assessing Medical and Pharmacy Costs Associated with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23:633–641. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.6.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brady BL, Tkacz J, Meyer R, Bolge SC, Ruetsch C. Assessment of Rheumatoid Arthritis Quality Process Measures and Associated Costs. Popul Health Manag. 2017;20:31–40. doi: 10.1089/pop.2015.0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weaver J, Sajjan S, Lewiecki EM, Harris ST, Marvos P. Prevalence and Cost of Subsequent Fractures Among U.S. Patients with an Incident Fracture. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23:461–471. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.4.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Statistics. UDoLBoL; Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics, editor. Chained Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (C-CPI-U) 1999–2017 MCSI. Vol. 2017. US Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics; Washington, DC: 2017. Consumer Price Index. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Estes C, Razavi H, Loomba R, Younossi Z, Sanyal AJ. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology. 2018;67:123–133. doi: 10.1002/hep.29466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polanco-Briceno S, Glass D, Stuntz M, Caze A. Awareness of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and associated practice patterns of primary care physicians and specialists. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:157. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-1946-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Charlton M, Cusi K, Rinella M, Harrison SA, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67:328–357. doi: 10.1002/hep.29367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tapper EB, Hunink MG, Afdhal NH, Lai M, Sengupta N. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis: Risk Stratification of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) by the Primary Care Physician Using the NAFLD Fibrosis Score. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0147237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costhelper. In.

- 23.Wright AP, Desai AP, Bajpai S, King LY, Sahani DV, Corey KE. Gaps in recognition and evaluation of incidentally identified hepatic steatosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:333–338. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3346-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koehler EM, Plompen EP, Schouten JN, Hansen BE, Darwish Murad S, Taimr P, Leebeek FW, et al. Presence of diabetes mellitus and steatosis is associated with liver stiffness in a general population: The Rotterdam study. Hepatology. 2016;63:138–147. doi: 10.1002/hep.27981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Younossi ZM, Park H, Saab S, Ahmed A, Dieterich D, Gordon SC. Cost-effectiveness of all-oral ledipasvir/sofosbuvir regimens in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:544–563. doi: 10.1111/apt.13081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elshaug AG, Rosenthal MB, Lavis JN, Brownlee S, Schmidt H, Nagpal S, Littlejohns P, et al. Levers for addressing medical underuse and overuse: achieving high-value health care. Lancet. 2017;390:191–202. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32586-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Patients with a first claim for NAFLD diagnosis between 2010–2014 were identified. A control cohort was assembled by identifying patients with at least one medical claim for an office visit during 2010–2014 and no medical claims with diagnosis codes for NAFLD or other liver diseases during the study period. The controls were matched 1:1 on age, sex, race, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, length of follow-up, year of diagnosis, geographic region and insurance type. The index date represents the date of first NAFLD claim or a randomly chosen office visit during the identification period for the control cohort, respectively.

All subjects were continuously enrolled in the health plan with medical and pharmacy benefits for at least 1 year before and 1 year after their index date (those who did not meet this criterion were excluded). The subjects were followed until disenrollment from the healthcare plan or study end-date (June 2016).