Abstract

Probiotics have evoked great interest in the past years for their beneficial effects. The aim of this study was to investigate whether luxS overexpression promotes the stress resistance of Lactobacillus paraplantarum L-ZS9. Here we show that overexpression of luxS gene increased the production of autoinducer-2 (AI-2, quorum sensing signal molecule) by L. paraplantarum L-ZS9. At the same time, overexpression of luxS promoted heat-, bile salt-resistance and biofilm formation of the strain. RNAseq results indicated that multiple genes encoding transporters, membrane proteins, and transcriptional regulator were regulated by luxS. These results reveal a new role for LuxS in promoting stress resistance and biofilm formation of probiotic starter.

Keywords: Lactobacillus paraplantarum L-ZS9, luxS, stress resistance, biofilm, RNAseq

Introduction

Over the past three decades, probiotic potential of some bacteria has been well-recognized. The beneficial effects of probiotic bacteria are mainly associated with the maintenance of a healthy gut microbiota, an improvement of gut resilience, the modulation of lactose intolerance, bowel function, and gastrointestinal (GI) comfort, and diarrhea prevention and symptom alleviation (Licciardi et al., 2010; Waitzberg et al., 2015; Wright et al., 2015; Kich et al., 2016; Mokoena et al., 2016). Probiotic food products, including probiotic powders and probiotic fermented food, account for a significant part of the functional foods in market (60–70% of the total functional food in market; García-Ruiz et al., 2014). Notably, to exert positive health effects, they have to colonize in the certain region of gastrointestinal tract and maintain themselves in certain numbers. The microorganism should survive adverse conditions during processing, storage, and the gastrointestinal transit. Therefore, it is important to enhance the stress resistance of probiotic bacteria. Although traditional researches focus on the development of protection materials and high density fermentation (Mamvura et al., 2011; Gbassi and Vandamme, 2012; Ortakci et al., 2012; D'Orazio et al., 2015; Ilango et al., 2016; Champagne et al., 2017), there is a great prospect to promote the stress resistance of probiotic bacteria by genetic engineering based on their molecular physiology.

Various bacteria use quorum sensing (QS) to communicate with each other. Autoinducer-2 (AI-2) is the universal language for intra-species and inter-species communication. Biosynthesis of AI-2 involves a three-step reaction, which is part of methionine catabolism cycle. Homolog of luxS which encodes the protein responsible for AI-2 production has been found in a wide range of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, with 17% of the phylum Bacteroidete and 83% of the Firmicutes predicted to have the homolog. This implies that some of the non-pathogenic or beneficial bacteria also use this “universal” and “common” signaling system to regulate their own behavior, including stress resistance and biofilm formation. However, the universal luxS-mediated quorum sensing using the autoinducer-2 (AI-2) signal is present in a wide variety of bacteria with only sparse information on probiotic lactobacilli (Yeo et al., 2015). It has been reported that AI-2-dependent autoaggregation enhances bacterial stress resistance and promotes biofilm formation of Escherichia coli (Laganenka et al., 2016). AI-2 signaling is also involved in the regulation of stress-related genes of Deinococcus radiodurans and triggers the oxidative stress response in Mycobacterium avium (Geier et al., 2008; Lin et al., 2016). As for lactic acid bacteria (LAB), it has been reported that Lactobacillus spp. use AI-2 signaling to respond to environmental stress and to regulate growth and metabolism (Park et al., 2016).

Lactobacillus paraplantarum L-ZS9 is a strain originally isolated from fermented sausage and proved to produce class II bacteriocins to inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria (Liu and Li, 2016; Zhang et al., 2016). It has a potential to be used as a probiotic and fermentation starter. In this study, we examined whether luxS overexpression enhances stress resistance of L. paraplantarum L-ZS9 and which genes are regulated by luxS overespression. We show that the effect of luxS on stress resistance including heat-, acid-, and bile-tolerance and biofilm formation of this strain. Furthermore, we identified multiple genes encoding transporters, membrane proteins, and transcriptional regulator regulated by LuxS. These results provide new insights into the regulation of stress resistance of probiotic starter and the molecular mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

L. paraplantarum L-ZS9 originally isolated from fermented sausage was grown at 37°C in de Man-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS) broth (Bridge, Beijing) or MRS-Agar aerobically. Escherichia coli DH5α (Takara, Dalian) was grown in Lennox broth (LB) or LB agar at 37°C. Escherichia coli DH5α containing pMG76e or luxS-pMG76e plasmid was cultured in LB medium containing 200 μg/mL erythromycin. L. paraplantarum L-ZS9 containing pMG76e or luxS-pMG76e plasmid was cultured in MRS broth or MRS-Agar containing 3 μg/mL erythromycin. Vibrio harveyi BB170 (sensor1- sensor2+) and BB152, kindly provided by Professor Xiangan Han (Shanghai Veterinary Research Institute, CAAS, Shanghai, China), were grown in Marine Broth 2216 (Difco Co., USA) or Autoinducer Bioassay (AB) medium. BB170 is an AI-2 biosensor strain. BB152 was used as a positive control for AI-2 production.

Construction of plasmids and bacterial strains

Chromosomal DNA of L. paraplantarum L-ZS9 was isolated using TIANamp Bacteria DNA Kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing). Gene luxS was amplified by PCR using primers 5′-TGCTCTAGAATGGCTAAAGTAGAAAGTTT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCGCTCGAGCTATTCAACGACTTTGCGAA-3′ (reverse) containing restriction sites XbaI and XhoI. The PCR product was cloned into pMD18T vector (Takara, Dalian) to construct vector luxS-pMD18T. Subsequently, luxS-pMD18T vector (Plac as the promoter) and pMG76e vector (P32 as the promoter) (kindly provided by Professor Shangwu Chen, China Agricultural University) were digested with fastDigest enzymes XbaI and XhoI (Thermo Scientific) at 37°C for 5 min to obtain luxS gene fragment and dual-enzyme digested linearized pMG76e plasmid. The luxS gene fragment was inserted into the linearized pMG76e plasmid using Rapid DNA Ligation Kit (Thermo Scientific). The ligation product was transformed into E. coli DH5α and verified by PCR using primers 5′-TTCGGTCCTCGGGATATG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTGTCTTGGCCGCTTCAA-3′ (reverse). luxS-pMG76e and empty pMG76e plasmids were electro-transformed into L. paraplantarum L-ZS9 competence cells. Recombinant strains were selected with erythromycin (3 μg/mL) and verified by PCR.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR)

Recombinant strains luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 and pMG76e-L-ZS9 and the wild-type strain L-ZS9 were cultured for 8 h achieve logarithmic phase. Total RNA was extracted from these cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacture's protocol. RNA quality was determined by A260/A280, A260/A230, and electrophoresis. Isolated RNA was transcribed into single-stranded cDNA using TUREscript 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Aidlab Biotechnologies Co., Ltd). qRT-PCR was performed using a SYBR Green assay kit (Tiangen) and the 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Primers were designed using Primer 3 Input. 16S rRNA was used as an internal reference. The relative expression of luxS was calculated by using the 2−ΔΔCT method according to Livak and Schmittgen (2001).

AI-2 detection

Recombinant strains luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 and pMG76e-L-ZS9 and the wild-type strain L-ZS9 were cultured in 12% (w/v) skim milk medium without erythromycin. At 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, and 24 h, cells were centrifuged at 12,000 g at 4°C for 10 min. The cell-free culture fluid (CF) was obtained by filtering the supernatant through a 0.22-μm filter (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) and adjusting the pH to 7.0. The reporter strain V. harveyi BB170 was diluted 1:5,000 in AB medium and the CF sample was added to the diluted BB170 culture at 1:10 (v/v). The mixture was incubated at 28°C for 5 h. One hundred microliters of aliquots were added to white, flat-bottomed, 96 well plates (Thermo Labsystems, Franklin, MA, USA) to detect AI-2 activity. The CF from BB152 and DH5α were used as the positive and negative control, respectively. Luminescence values were measured with a Tecan GENios Plus microplate reader in luminescence mode (Tecan Austria GmbH, Grodig, Austria).

Growth curves

Recombinant strains luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 and pMG76e-L-ZS9 and the wild-type strain L-ZS9 were cultured in MRS without erythromycin. At 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24, 27, 30, 33, and 36 h, the cell densities were determined by measuring OD600 using a UV-1800 Spectrophotometer. Measurements were carried out in triplicate.

Biofilm formation

Crystal violet (CV) staining was used to quantify biofilm formation by recombinant strains luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 and pMG76e-L-ZS9 and the wild-type strain L-ZS9. Briefly, overnight cultures were diluted to an optical density of 0.1 at 600 nm. Two hundred microliters of diluted culture were transferred to a 96-well plate (Corning, NY, USA). After incubation at 37°C for 36 h, the wells were washed gently three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), stained with 0.1% CV for 30 min at room temperature, rinsed with distilled water and air-dried. One hundred microliters of 95% ethanol was added to each well to dissolve the CV. The optical density at 595 nm was determined using a Synergy 2 microplate reader (Biotek, Winooski, VT, USA).

Stress resistance assay

Recombinant strains luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 and pMG76e-L-ZS9 and the wild-type strain L-ZS9 were cultured in MRS without erythromycin for 8 h to logarithmic phase. Cells were centrifuged at 5,000 g at 4°C for 5 min and washed with PBS for three times. Cells were treated at 80°C for 3 min. Survived cells were determined by flat colony counting method to assess the heat resistance. To compare acid- and bile- resistance, cells were centrifuged at 5,000 g for 5 min and then resuspended in PBS (pH 2.8) or PBS containing bile salt (0.2%, w/v). After 30 min, the survived cells were determined by flat colony counting method. Cell heat-, acid-, and bile- resistance was assessed by cell survival rates. The survival rates were calculated as follows: survival cell number/initial cell number × 100%. The initial cell number was 1 × 109.

Total RNA extraction and sequencing

Recombinant strains luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 and pMG76e-L-ZS9 were cultured in MRS with erythromycin for 8 h to logarithmic phase. Total RNA (3 independent extractions for each strain) was isolated using the TRIzol reagent (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions and treated with DNase I to remove DNA. The MICROBExpress Kit (Ambion) was used to deplete rRNA from total RNA. Libraries were constructed using NEBNext1Ultra™ Directional RNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina). One hundred bp single end sequence reads were generated using the Illumina HiSeq 4000 platform at the Vienna Biocenter Campus Science Support Facility. Sequencing adapter removal was performed with cutadapt. Mapping of the samples against the L. paraplantarum L-ZS9 reference genome (NCBI accession number CP013130) was performed with Segemehl with default parameters. Reads mapped to be rRNA or tRNA were discarded from all data and ignored for all follow up analysis. The mapped sequencing data were prepared for visualization using the ViennaNGS tool box and visualized within the UCSC Genome Browser. Differential gene expression analysis was performed with DESeq (version 1). All genes with a fold change >2.0 and a multiple testing adjusted p-value below 0.05 were considered to be significantly modulated. All RNA-seqs were performed triple biological replicates per sample.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Graphpad prism 5.0. Data are presented as means ± SEM. P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Overexpression of luxS gene promotes AI-2 production by L. paraplantarum L-ZS9

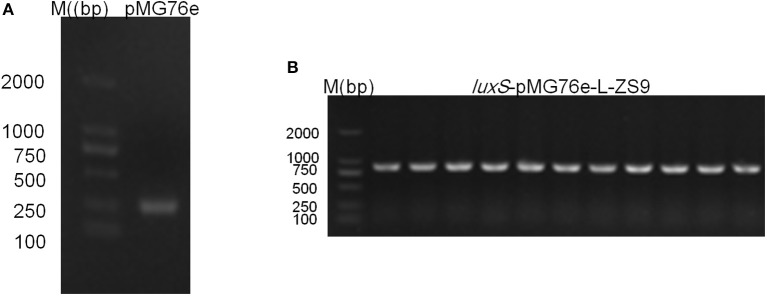

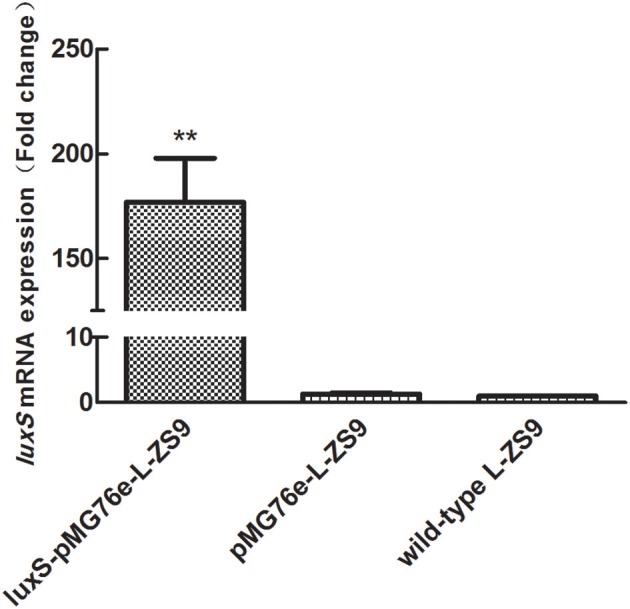

Recombinant strains luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 and pMG76e-L-ZS9 were constructed from parent strain L. paraplantarum L-ZS9 and identified by PCR (Figure 1). In order to validate the overexpression of luxS gene, qRT-PCR was carried out to analyze the relative mRNA level of luxS in luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9, pMG76e-L-ZS9, and wild-type L-ZS9 cells. As shown in Figure 2, the luxS mRNA expression in luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 cells were up-regulated about 177-folds compared to that in L-ZS9 cells, but luxS transcription in pMG76e-L-ZS9 cells was comparable to wild type cells.

Figure 1.

Agrose gel electrophoresis of PCR validation result of pMG76e-L-ZS9 (A) and luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 (B) strains using primers 76e-F/R.

Figure 2.

luxS mRNA expressions of pMG76e-L-ZS9, luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 and wild-type strains. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n ≥ 3. **p < 0.01 compared with the negative control.

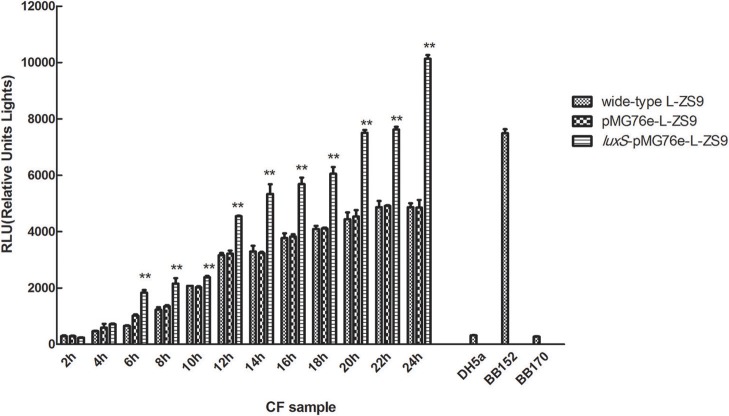

Luxs gene encodes an enzyme involved in the metabolism of S-ribosylhomocysteine, finally leading to the production of AI-2. AI-2 activities were measured in recombinant strains luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9, pMG76e-L-ZS9, and the wild-type strain. As shown in Figure 3, introduction of empty plasmid pMG76e had no influence on AI-2 activities of L-ZS9 from 2 to 24 h. The AI-2 activities of luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 were significantly increased compared to pMG76e-L-ZS9 and the wild-type strain from 6 to 24 h. The AI-2 activity of luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 was almost double that of pMG76e-L-ZS9 and wild-type strain in the cell-free culture fluid (CF) collected at 24 h. These results suggested that overexpression of luxS gene promoted AI-2 production in L. paraplantarum L-ZS9.

Figure 3.

AI-2 activity in cell-free culture fluids (CF) of pMG76e-L-ZS9, luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 and wild-type strains. V. harveyi BB152 served as a positive control and E. coli DH5α as a negative control. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n ≥ 3. **p < 0.01 compared with the negative control.

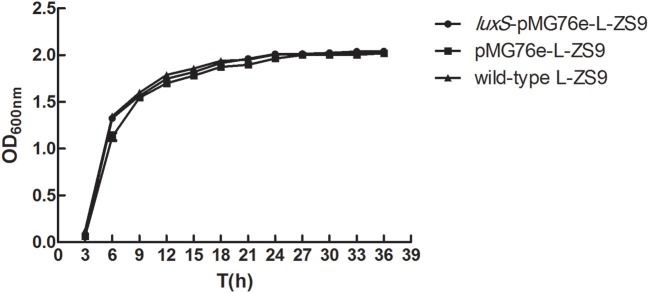

Overexpression of luxS gene had no influence on the growth of L. paraplantarum L-ZS9

In order to determine whether overexpression of luxS influenced the growth of L-ZS9, we evaluated bacterial growth by measuring OD600 from 3 to 36 h. Overexpression of wild-type L-ZS9 with luxS showed a comparable growth rate to that of pMG76e-L-ZS9 (Figure 4). These data suggested that overexpression of luxS gene exerts no significant effect on the growth of L-ZS9.

Figure 4.

Growth curves of pMG76e-L-ZS9, luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 and wild-type strains. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n ≥ 3.

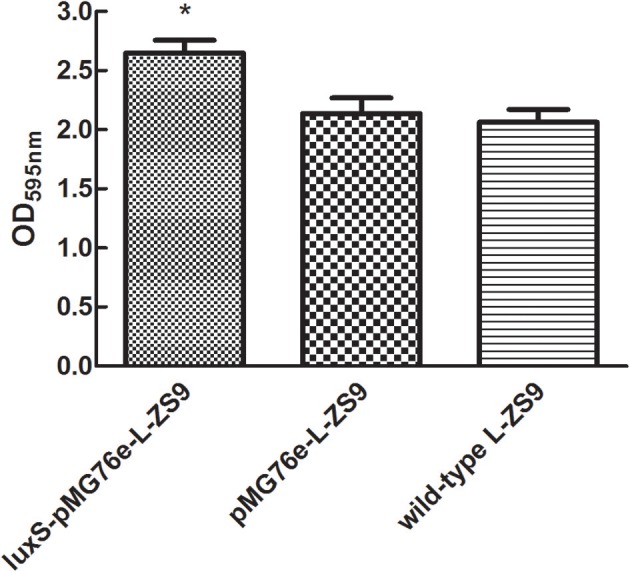

Overexpression of luxS gene enhanced biofilm formation of L. paraplantarum L-ZS9

Since LuxS/AI-2-dependent QS exerts essential functions in biofilm formation of many bacterial pathogens in various ways, the ability of recombinant strains to form biofilm was also determined. As shown in Figure 5, there was no significant difference in biofilm formation between pMG76e-L-ZS9 and the wild-type strain, suggesting that the empty plasmid pMG76e had no influence on biofilm formation of L-ZS9. The biofilm formation of luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 increased significantly, as compared with the pMG76e-L-ZS9 and the wild-type strain. These data indicate that the LuxS gene was involved in the formation of L-ZS9 biofilms.

Figure 5.

Biofilm formation of pMG76e-L-ZS9, luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 and wild-type strains. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n ≥ 3. *p < 0.05 compared with the control.

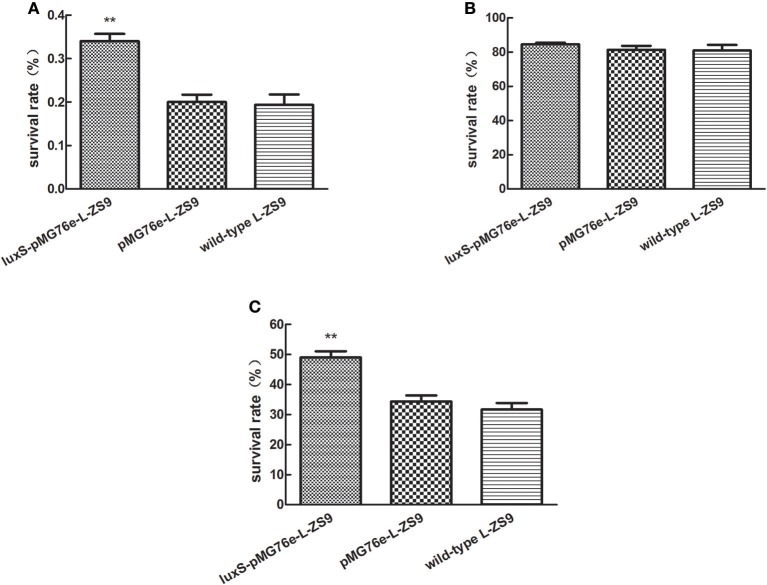

Overexpression of luxS gene improved stress resistances of L. paraplantarum L-ZS9

In nature, bacteria have developed a variety of mechanisms of resistance to environmental stresses. Since biofilm formation has been reported to contribute to stress resistance of bacteria, in order to determine the role of LuxS in stress resistance of L-ZS9, we tested the survival in heat, acid and bile salt. As shown in Figure 6, there was no significant difference in heat-, acid- and bile resistance between pMG76e-L-ZS9 and the wild-type strain, suggesting that the empty plasmid pMG76e had no influence on stress resistance of L-ZS9. However, the heat- and bile- resistance activities but not acid-resistance of luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 were much higher than that of pMG76e-L-ZS9 and the wild-type strain (Figures 6A,C). The survival rates of luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 were about 179 and 153% with the wild-type as 100% after the heat- and bile- shock, respectively. Considering the initial cell number was 1 × 109, the increased amounts of luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 were 1.5 × 106 and 1.7 × 108 after the heat- and bile-shock, respectively. These results suggested that LuxS was contribute to the resistance activities of L. paraplantarum L-ZS9 against heat and bile salt.

Figure 6.

Heat- (A), acid- (B), and bile salt- (C) resistance of pMG76e-L-ZS9, luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9, and wild-type strains. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n ≥ 3. **p < 0.01 compared with the control.

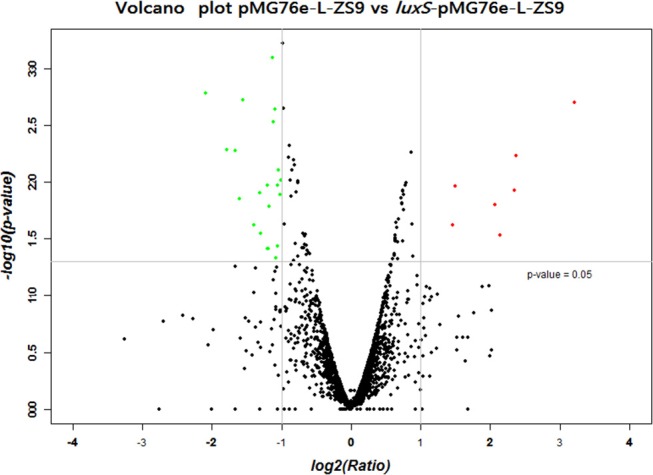

luxS overexpression altered gene transcription profiles in L. paraplantarum L-ZS9

In order to identify genes that were regulated by luxS, comparative RNA-seq was carried out in both recombinant strains luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 and pMG76e-L-ZS9. The concentration of the extracted RNA was shown in Table S1 and their agrose gel eletrophoresis images were shown in Figure S1. Their raw and filtered data quality was listed in Table S2. The evaluation of data quality of pMG76e-L-ZS9 and luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 was shown in Figures S2, S3. In this study, 35 differentially expressed genes (change at least 2-folds) were identified (Table 1) and their volcano plot was shown in Figure 7. Among these genes, gene luxS was up-regulated by 205 folds. In addition, the expression of 12 genes encoding hypothetical proteins, 9 genes encoded transporter proteins and 3 genes encoded membrane proteins was altered, which totally accounted for about 50% of annotated genes.

Table 1.

Differentially expressed genes in cells of luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 compared to pMG76e-L-ZS9.

| Gene name | Fold change (log2) | ID | Protein ID | Product |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASU28_RS14150 | inf | gene2829 | WP_033611588.1 | Allulose-6-phosphate 3-epimerase |

| ASU28_RS08065 sugE | inf | gene1612 | WP_033610729.1 | QacE family quaternary ammonium compound efflux SMR transporter |

| ASU28_RS10630 | inf | gene2125 | WP_033612003.1 | Hypothetical protein |

| Hypothetical protein | inf | gene2744 | ||

| ASU28_RS05215 | inf | gene1042 | WP_021731301.1 | Hypothetical protein |

| ASU28_RS07600 | inf | gene1519 | WP_003640551.1 | Hypothetical protein |

| ASU28_RS04530 luxS | 7.68443 | gene905 | WP_003641031.1 | S-ribosylhomocysteine lyase |

| ASU28_RS09300 | 1.49615 | gene1859 | WP_033610969.1 | Hypothetical protein |

| ASU28_RS11200 betT | 1.4642 | gene2239 | WP_033612092.1 | BetT protein |

| ASU28_RS07105 | −1.00272 | gene1420 | WP_021731448.1 | Integral membrane protein |

| ASU28_RS03050 | −1.01778 | gene609 | WP_033610853.1 | Nitrobenzoate reductase |

| ASU28_RS12410 | −1.04367 | gene2481 | WP_033610593.1 | AraC family transcriptional regulator |

| ASU28_RS11675 | −1.05829 | gene2334 | WP_033610057.1 | DNA-binding protein |

| ASU28_RS04420 | −1.05901 | gene883 | WP_033611045.1 | Phosphate ABC transporter ATP-binding protein |

| ASU28_RS14105 | −1.07651 | gene2820 | WP_033611599.1 | PTS beta-glucoside transporter subunit EIIBCA |

| ASU28_RS10550 recT | −1.09727 | gene2109 | WP_033611994.1 | DNA recombination protein RecT |

| ASU28_RS10555 | −1.09727 | gene2110 | WP_033611995.1 | Hypothetical protein |

| ASU28_RS06500 | −1.11328 | gene1299 | WP_021731687.1 | Hypothetical protein |

| ASU28_RS05530 | −1.1354 | gene1105 | WP_033609957.1 | Membrane protein |

| ASU28_RS05645 | −1.17751 | gene1128 | WP_021731360.1 | Hypothetical protein |

| ASU28_RS01930 | −1.18473 | gene385 | WP_033611287.1 | Glycerol transporter |

| ASU28_RS12280 | −1.1997 | gene2455 | WP_033610185.1 | DNA-3-methyladenine glycosylase |

| ASU28_RS05640 | −1.20425 | gene1127 | WP_021731359.1 | MATE family efflux transporter |

| ASU28_RS03805 | −1.30129 | gene760 | WP_021731968.1 | Hypothetical protein |

| ASU28_RS03675 | −1.31353 | gene734 | WP_033610025.1 | Glycine cleavage system protein H |

| ASU28_RS01640 | −1.39723 | gene327 | WP_033610437.1 | Hypothetical protein |

| ASU28_RS10560 | −1.55545 | gene2111 | WP_033611996.1 | Hypothetical protein |

| integrase | −1.6056 | gene2702 | ||

| ASU28_RS03705 | −1.66843 | gene740 | WP_033610031.1 | GNAT family acetyltransferase |

| ASU28_RS10520 | −1.78945 | gene2103 | WP_052048925.1 | Transcriptional regulator |

| ASU28_RS03605 nhaC | −2.08869 | gene720 | WP_033610935.1 | Na+/H+ antiporter NhaC |

| ASU28_RS08220 | inf | gene1643 | WP_033610753.1 | PTS sugar transporter subunit IIA |

| ASU28_RS10765 | inf | gene2152 | WP_033612020.1 | Hypothetical protein |

| ASU28_RS03720 | inf | gene743 | WP_033610033.1 | Membrane protein |

| ASU28_RS08120 | inf | gene1623 | WP_033610736.1 | Membrane protein |

inf, infinite.

Figure 7.

Volcano plot of different expression genes of pMG76e-L-ZS9 and luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 strains.

Discussion

LuxS is a key enzyme for the biosynthesis of AI-2. The precursor of AI-2, 4,5-dihydroxy-2,3 pentanedione (DPD), is a by-product of methionine catabolism formed through three reactions. The first step for AI-2 formation is the removal of methyl group from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), which is catalyzed by SAM-dependent methylferases. The resulting product, S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH), is converted to S-ribosylhomocysteine (SRH) by the enzyme SAH nucleosidase (Parveen and Cornell, 2011). SRH is hydrolysed to DPD by LuxS (Schauder et al., 2001). DPD further undergoes autocatalytically hydrolysis to form AI-2. Many studies have pointed out the pivotal role of LuxS in biological processes in many bacteria. Our previous data found that D-Ribose interferes with quorum sensing to inhibit biofilm formation of L. paraplantarum L-ZS9, suggesting the significance of quorum sensing in biological activity of L-ZS9. In this study, we have identified the role for LuxS as a positive regulator of biofilm formation and stress resistance in L. paraplantarum L-ZS9. To examine the effect of LuxS on the biological process of L. paraplantarum, we constructed a LuxS overexpressed L-ZS9 strain. The recombinant strain luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 displayed enhanced AI-2 production, along with that of previous published studies in other bacteria, clearly indicating that LuxS contributes to AI-2 synthesis in L. paraplantarum. It is interesting that manipulation of AI-2 levels alters the composition of the animal gut microbiota. The E. coli strain overproducing AI-2 changes the balance between Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes in the gut of a streptomycin-treated mouse, partly offsetting the effects of the antibiotic (Sourjik and Vorholt, 2015). Therefore, probiotics overproducing AI-2 may have better effects on regulation of gastrointestinal microbiota and their beneficial functions need further investigation.

Previous studies have reported that LuxS acts in concert to control the adaption of A. actinomycetemcomitans to iron-limiting conditions and its growth under such conditions (Fong et al., 2003). Deletion of luxS in B. anthracis Sterne strain 34F2 results in inhibition of AI-2 synthesis and a growth defect (Jones et al., 2016). However, luxS gene does not regulate the growth rate E. faecalis, but affects the biofilm formation (He et al., 2016). The data we present here, along with that of E. faecalis, suggested that overexpression of luxS did not affect the L-ZS9 growth. LuxS is involved in biofilm formation of various strains (Sela et al., 2006; Karim et al., 2013; Niu et al., 2013; He et al., 2015). The luxS mutants of L. rhamnosus GG have a lower capacity to form biofilms than the wild-type strain (Lebeer et al., 2007, 2008). In consistence with these studies, LuxS was involved in biofilm formation of L-ZS9 and its overexpression enhanced the biofilm formation. Biofilms constitute the predominant microbial style of life in natural and engineered ecosystems. The formation of biofilms, microbial communities embedded in self-produced polymeric matrices attached to a surface, is an ancient and universal trait that enables microorganisms to develop coordinated architectural and survival strategies (Gambino and Cappitelli, 2016). Biofilms are closely related with adhesion. This life style helps microorganisms to survive under unfavorable environmental conditions (Taylor et al., 2014; Olsen, 2015). It has been demonstrated that biofilms of Lactobacillus exhibit higher tolerance than planktonic counterpart (Kubota et al., 2009; Cheow and Hadinoto, 2013). The biofilm enhances the immunomodulatory effects of Lactobacillus sp. (Rieu et al., 2014). It has been reported that the luxS gene plays an important role in the gastrointestinal environment tolerance and adhesion ability of Lactobacillus plantarum KLDS1.0391 (Jia et al., 2018). AI-2 inhibition correlated with a reduction in the stress-related genes of Lactobacillus rhamnosus (Yeo et al., 2015). In addition, LuxS metabolism is crucial for the gastric stress resistance of L. rhamnosus GG (Lebeer et al., 2008). In this study, luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 had greater biofilm formation ability, suggesting that the recombinant strain may have greater resistance to adverse stress.

It has been reported that quorum sensing is involved in regulating drug resistance of bacteria (Liang et al., 2016; Xue et al., 2016; Yufan et al., 2016; Lai et al., 2017), but few studies have investigated the regulation of stress resistance by quorum sensing or LuxS. Quorum sensing facilitates the stress resistance of E. coli in microcapsules by detecting the expression of luxS/AI-2 system (Gao et al., 2016). In this study, the heat- and bile- resistances of L-ZS9 were significantly improved when luxS was overexpressed in the strain. How LuxS gene regulates stress resistance of L-ZS9 in this context remains to be fully elucidated, but is likely to involve the changed gene expression profile.

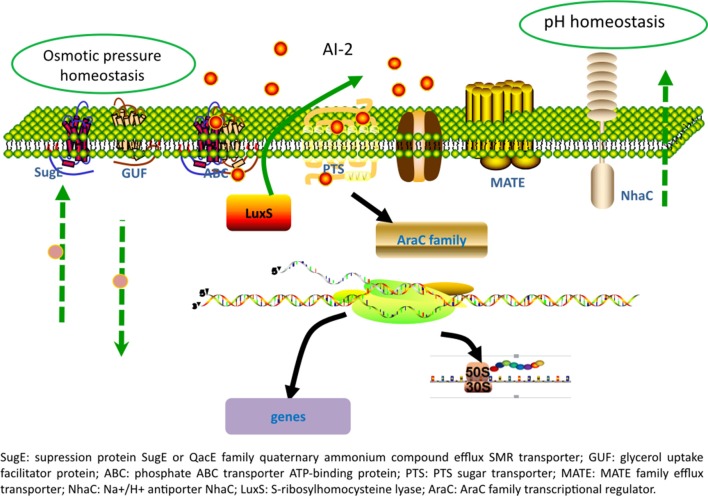

Identification of gene expression profile at the presence of LuxS may have important industrial implications. RNAseq analysis identified 35 differentially expressed genes in recombinant strains luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9. Multiple efflux systems are classified into five different families, including ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family, major facilitator super family (MFS), resistance/nodulation/cell division (RND) family, multidrug, and toxic—compound extrusion (MATE) family and the small multidrug resistance (SMR) family. In the present study, some members of ABC, MATE, and SMR families were identified to be regulated by luxS. There are three main mechanisms playing pivotal roles in cell survival with biofilms: biofilm-specific protection against oxidative stress, the expression of efflux pumps and the protection provided by matrix polysaccharides (Billings et al., 2015; Jhajharia et al., 2015; Rasamiravaka et al., 2015). It has been reported that biofilm formation of E. coli was regulated by many redundant multidrug resistance transporters (Bay et al., 2016). One SMR transporter, SugE, was identified in luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 strain. SugE is a suppressor of groEL mutation proteins and they may play an important role in the uptake of chaperone regulatory compounds (Bay and Turner, 2011). And gene sugE affected biofilm formation by modulating capsular polysaccharide (CPS) production in a Klebsiella pneumoniae strain (Wu et al., 2011). Two MATE genes (ASU28_RS05640 and ASU28_RS03605) were down-regulated in luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9. MATE efflux transporters are believed to be universally present in all living organisms. They play critical roles in cellular physiology and drug resistance (Kuroda and Tsuchiya, 2009). ABC transporters are integral membrane proteins that move diverse substrates across cellular membranes (Hopfner, 2016). And it has been reported that the signal AI-2 could be imported through ABC type importers (Quan et al., 2016). In addition, two genes of phosphotransferase system (PTS) were identified. Gene ASU28_RS14105 was down-regulated and ASU28_RS08220 did not expressed in luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9. PTS is a sugar-phosphorylating system and a complex protein kinase system that regulates a wide variety of metabolic processes and controls the expression of numerous genes (Khajanchi et al., 2015; Somavanshi et al., 2016; Westermayer et al., 2016). It has been reported that AI-2 could be imported through the PTS (Quan et al., 2016). These results suggested that luxS regulated expression of membrane and transporter related proteins.

In the present study, one AraC family of transcriptional regulator (ASU28_RS12410) was differentially expressed. The AraC family of transcriptional regulators (AFTRs) constitutes one of the largest groups of regulatory proteins in bacteria. It has been reported that AraC-type transcriptional regulator Rbf plays an important role in biofilm-associated medical-device-related infection (Rowe et al., 2016). In addition, gene ASU28_RS01930 was down-regulated in luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9. This gene encodes glycerol transporter/aquaporin/glycerol uptake facilitator protein. It has been reported that aquaporin 7 is an aquaglyceroporin that has been found to operate as a facilitative carrier rather than a channel for glycerol, although its primary function is as a water channel (Katano et al., 2014). This study showed that multiple gene or proteins including transporters and transcriptional regulator and other proteins were regulated by luxS.

Conclusions

Overexpression of luxS in L. paraplantarum L-ZS9 promoted AI-2 production and enhanced the stress-resistance and biofilm formation of this strain. As shown in Figure 8, luxS plays roles in modulating physiological behaviors of this strain mainly through regulating multiple transporters and transcriptional regulator and the underlying mechanism needs to be further elucidated.

Figure 8.

A hypothetical model of the effect of LuxS overexpression on L. paraplantarum L-ZS9.

Author contributions

LL and PL conceived and designed the experiments. LL performed the experiments. LL and RW analyzed the data. JZ contributed reagents. LL wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) No. 31671831.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2018.02628/full#supplementary-material

Concentration of RNA of pMG76e-L-ZS9 and luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 strains.

Raw and filtered data quality of pMG76e-L-ZS9 and luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9.

Agrose gel electrophoresis of RNA of pMG76e-L-ZS9 and luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 strains.

Evaluation of data quality of pMG76e-L-ZS9.

Evaluation of data quality of luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9.

References

- Bay D. C., Stremick C. A., Slipski C. J., Turner R. J. (2016). Secondary multidrug efflux pump mutants alter Escherichia coli biofilm growth in the presence of cationic antimicrobial compounds. Res. Microbiol. 168, 208–221. 10.1016/j.resmic.2016.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bay D. C., Turner R. J. (2011). Spectroscopic analysis of the intrinsic chromophores within small multidrug resistance protein SugE. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1808, 2233–2244. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billings N., Birjiniuk A., Samad T. S., Doyle P. S., Ribbeck K. (2015). Material properties of biofilms-a review of methods for understanding permeability and mechanics. Rep. Prog. Phys. 78:36601. 10.1088/0034-4885/78/3/036601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne C. P., Raymond Y., Arcand Y. (2017). Effects of production methods and protective ingredients on the viability of probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus R0011 in air-dried alginate beads. Can. J. Microbiol. 63, 35–45. 10.1139/cjm-2016-0349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheow W. S., Hadinoto K. (2013). Biofilm-like Lactobacillus rhamnosus probiotics encapsulated in alginate and carrageenan microcapsules exhibiting enhanced thermotolerance and freeze-drying resistance. Biomacromolecules 14, 3214–3222. 10.1021/bm400853d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Orazio G., Di Gennaro P., Boccarusso M., Presti I., Bizzaro G., Giardina S., et al. (2015). Microencapsulation of new probiotic formulations for gastrointestinal delivery: in vitro study to assess viability and biological properties. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 99, 9779–9789. 10.1007/s00253-015-6853-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong K. P., Gao L., Demuth D. R. (2003). luxS and arcB control aerobic growth of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans under iron limitation. Infect. Immun. 71, 298–308. 10.1128/IAI.71.1.298-308.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambino M., Cappitelli F. (2016). Mini-review: biofilm responses to oxidative stress. Biofouling 32, 167–178. 10.1080/08927014.2015.1134515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M., Song H., Zheng H., Ren Y., Li S., Liu X., et al. (2016). Culture of low density E. coli cells in alginate-chitosan microcapsules facilitates stress resistance by up-regulating luxS/AI-2 system. Carbohydr. Polym. 141, 160–165. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Ruiz A., González de Llano D, Esteban-Fernandez A., Requena T., Bartolome B., Moreno-Arribas M. V. (2014). Assessment of probiotic properties in lactic acid bacteria isolated from wine. Food Microbiol. 44, 220–225. 10.1016/j.fm.2014.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gbassi G. K., Vandamme T. (2012). Probiotic encapsulation technology: from microencapsulation to release into the gut. Pharmaceutics 4, 149–163. 10.3390/pharmaceutics4010149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geier H., Mostowy S., Cangelosi G. A., Behr M. A., Ford T. E. (2008). Autoinducer-2 triggers the oxidative stress response in Mycobacterium avium, leading to biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 1798–1804. 10.1128/AEM.02066-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z., Liang J., Tang Z., Ma R., Peng H., Huang Z. (2015). Role of the luxS gene in initial biofilm formation by Streptococcus mutans. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 25, 60–68. 10.1159/000371816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z., Liang J., Zhou W., Xie Q., Tang Z., Ma R., et al. (2016). Effect of the quorum-sensing luxS gene on biofilm formation by Enterococcus faecalis. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 124, 234–240. 10.1111/eos.12269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopfner K. P. (2016). Invited review: architectures and mechanisms of ATP binding cassette proteins. Biopolymers 105, 492–504. 10.1002/bip.22843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilango S., Pandey R., Antony U. (2016). Functional characterization and microencapsulation of probiotic bacteria from koozh. J. Food Sci. Technol. 53, 977–989. 10.1007/s13197-015-2169-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhajharia K., Parolia A., Shetty K. V., Mehta L. K. (2015). Biofilm in endodontics: a review. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 5, 1–12. 10.4103/2231-0762.151956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia F. F., Zheng H. Q., Sun S. R., Pang X. H., Liang Y., Shang J. C., et al. (2018). Role of luxS in stress tolerance and adhesion ability in Lactobacillus plantarum KLDS1.0391. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018:4506829. 10.1155/2018/4506829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M. B., Peterson S. N., Benn R., Braisted J. C., Jarrahi B., Shatzkes K., et al. (2016). Role of luxS in Bacillus anthracis growth and virulence factor expression. Virulence 1, 72–83. 10.4161/viru.1.2.10752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim M. M., Hisamoto T., Matsunaga T., Asahi Y., Noiri Y., Ebisu S., et al. (2013). LuxS affects biofilm maturation and detachment of the periodontopathogenic bacterium Eikenella corrodens. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 116, 313–318. 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2013.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katano T., Ito Y., Ohta K., Yasujima T., Inoue K., Yuasa H. (2014). Functional characteristics of aquaporin 7 as a facilitative glycerol carrier. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 29, 244–248. 10.2133/dmpk.DMPK-13-RG-121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khajanchi B. K., Odeh E., Gao L., Jacobs M. B., Philipp M. T., Lin T., et al. (2015). Phosphoenolpyruvate phosphotransferase system components modulate gene transcription and virulence of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 84, 754–764. 10.1128/IAI.00917-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kich D. M., Vincenzi A., Majolo F., Volken de Souza C. F., Goettert M. I. (2016). Probiotic: effectiveness nutrition in cancer treatment and prevention. Nutr. Hosp. 33, 1430–1437. 10.20960/nh.806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota H., Senda S., Tokuda H., Uchiyama H., Nomura N. (2009). Stress resistance of biofilm and planktonic Lactobacillus plantarum subsp. plantarum JCM 1149. Food Microbiol. 26, 592–597. 10.1016/j.fm.2009.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda T., Tsuchiya T. (2009). Multidrug efflux transporters in the MATE family. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1794, 763–768. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laganenka L., Colin R., Sourjik V. (2016). Chemotaxis towards autoinducer 2 mediates autoaggregation in Escherichia coli. Nat. Commun. 7:12984. 10.1038/ncomms12984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai B. M., Zhang K., Shen D. S., Wang M. Z., Shentu J. L., Li N. (2017). Control of the pollution of antibiotic resistance genes in soils by quorum sensing inhibition. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 24, 5259–5267. 10.1007/s11356-016-8260-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebeer S., Claes I. J., Verhoeven T. L., Shen C., Lambrichts I., Ceuppens J. L., et al. (2008). Impact of luxS and suppressor mutations on the gastrointestinal transit of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 4711–4718. 10.1128/AEM.00133-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebeer S., Verhoeven T. L., Perea Vélez M, Vanderleyden J., De Keersmaecker S. C. (2007). Impact of environmental and genetic factors on biofilm formation by the probiotic strain Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 6768–6775. 10.1128/AEM.01393-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z. B., Chen Y. M., Chen Y., Cheng Y. Y., Zhang L. H. (2016). RND efflux pump and its interrelationship with quorum sensing system. Yi Chuan 38, 894–901. 10.16288/j.yczz.16-139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licciardi P. V., Wong S. S., Tang M. L., Karagiannis T. C. (2010). Epigenome targeting by probiotic metabolites. Gut Pathog. 2:24. 10.1186/1757-4749-2-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L., Li T., Dai S., Yu J., Chen X., Wang L., et al. (2016). Autoinducer-2 signaling is involved in regulation of stress-related genes of Deinococcus radiodurans. Arch. Microbiol. 198, 43–51. 10.1007/s00203-015-1163-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Li P. (2016). Complete genome sequence of Lactobacillus paraplantarum L-ZS9, a probiotic starter producing class II bacteriocins. J. Biotechnol. 222, 15–16. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamvura C. I., Moolman F. S., Kalombo L., Hall A. N., Thantsha M. S. (2011). Characterisation of the poly-(vinylpyrrolidone)-poly-(vinylacetate-co-crotonic acid) (pvp:pvac-ca) interpolymer complex matrix microparticles encapsulating a Bifidobacterium lactis BB12 probiotic strain. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 3, 97–102. 10.1007/s12602-011-9075-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokoena M. P., Mutanda T., Olaniran A. O. (2016). Perspectives on the probiotic potential of lactic acid bacteria from African traditional fermented foods and beverages. Food Nutr. Res. 60:29630. 10.3402/fnr.v60.29630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu C., Robbins C. M., Pittman K. J., Osborn J. L., Stubblefield B. A., Simmons R. B., et al. (2013). LuxS influences Escherichia coli biofilm formation through autoinducer-2-dependent and autoinducer-2-independent modalities. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 83, 778–791. 10.1111/1574-6941.12034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen I. (2015). Biofilm-specific antibiotic tolerance and resistance. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 34, 877–886. 10.1007/s10096-015-2323-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortakci F., Broadbent J. R., McManus W. R., McMahon D. J. (2012). Survival of microencapsulated probiotic Lactobacillus paracasei LBC-1e during manufacture of Mozzarella cheese and simulated gastric digestion. J. Dairy Sci. 95, 6274–6281. 10.3168/jds.2012-5476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H., Shin H., Lee K., Holzapfel W. (2016). Autoinducer-2 properties of kimchi are associated with lactic acid bacteria involved in its fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 225, 38–42. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parveen N., Cornell K. A. (2011). Methylthioadenosine/S-adenosylhomocysteine nucleosidase, a critical enzyme for bacterial metabolism. Mol. Microbiol. 79, 7–20. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07455.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan D. N., Tsao C. Y., Wu H. C., Bentley W. E. (2016). Quorum sensing desynchronization leads to bimodality and patterned behaviors. PLoS Comput. Biol. 12:e1004781. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasamiravaka T., Labtani Q., Duez P., El Jaziri M. (2015). The formation of biofilms by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a review of the natural and synthetic compounds interfering with control mechanisms. Biomed Res. Int. 2015:759348. 10.1155/2015/759348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieu A., Aoudia N., Jego G., Chluba J., Yousfi N., Briandet R., et al. (2014). The biofilm mode of life boosts the anti-inflammatory properties of Lactobacillus. Cell. Microbiol. 16, 1836–1853. 10.1111/cmi.12331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe S. E., Campbell C., Lowry C., O'Donnell S. T., Olson M. E., Lindgren J. K., et al. (2016). AraC-Type regulator Rbf controls the Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm phenotype by negatively regulating the icaADBC repressor SarR. J. Bacteriol. 198, 2914–2924. 10.1128/JB.00374-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauder S., Shokat K., Surette M. G., Bassler B. L. (2001). The LuxS family of bacterial autoinducers: biosynthesis of a novel quorum-sensing signal molecule. Mol. Microbiol. 41, 463–476. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02532.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sela S., Frank S., Belausov E., Pinto R. A. (2006). A mutation in the luxS gene influences Listeria monocytogenes biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5653–5658. 10.1128/AEM.00048-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somavanshi R., Ghosh B., Sourjik V. (2016). Sugar influx sensing by the phosphotransferase system of Escherichia coli. PLoS Biol. 14:e2000074. 10.1371/journal.pbio.2000074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sourjik V., Vorholt J. A. (2015). Bacterial networks in cells and communities. J. Mol. Biol. 427, 3785–3792. 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P. K., Yeung A. T., Hancock R. E. (2014). Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: towards the development of novel anti-biofilm therapies. J. Biotechnol. 191, 121–130. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waitzberg D. L., Quilici F. A., Michzputen S., Friche P., Mdo C. (2015). The effect of probiotic fermented milk that includes Bifidobacterium lactis cncm i-2494 on the reduction of gastrointestinal discomfort and symptoms in adults: a narrative review. Nutr. Hosp. 32, 501–509. 10.3305/nh.2015.32.2.9232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermayer S. A., Fritz G., Gutiérrez J., Megerle J. A., Weiβl M. P., Schnetz K., et al. (2016). Single-cell characterization of metabolic switching in the sugar phosphotransferase system of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 100, 472–485. 10.1111/mmi.13329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright K., Wright H., Murray M. (2015). Probiotic treatment for the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in geriatric patients: a multicentre randomised controlled pilot study. Australas. J. Ageing 34, 38–42. 10.1111/ajag.12116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M. C., Lin T. L., Hsieh P. F., Yang H. C., Wang J. T. (2011). Isolation of genes involved in biofilm formation of a Klebsiella pneumoniae strain causing pyogenic liver abscess. PLoS ONE 6:e23500. 10.1371/journal.pone.0023500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue T., Yu L., Shang F., Li W., Zhang M., Ni J., et al. (2016). Short communication: the role of autoinducer 2 (AI-2) on antibiotic resistance regulation in an Escherichia coli strain isolated from a dairy cow with mastitis. J. Dairy Sci. 99, 4693–4698. 10.3168/jds.2015-10543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo S., Park H., Ji Y., Park S., Yang J., Lee J., et al. (2015). Influence of gastrointestinal stress on autoinducer-2 activity of two Lactobacillus species. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 91:fiv065. 10.1093/femsec/fiv065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yufan C., Shiyin L., Zhibin L., Mingfa L., Jianuan Z., Lianhui Z. (2016). Quorum sensing and microbial drug resistance. Yi Chuan 38, 881–893. 10.16288/j.yczz.16-141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Wang Y., Liu L., Wei Y., Shang N., Zhang X., et al. (2016). Two-peptide bacteriocin PlnEF causes cell membrane damage to Lactobacillus plantarum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1858, 274–280. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Concentration of RNA of pMG76e-L-ZS9 and luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 strains.

Raw and filtered data quality of pMG76e-L-ZS9 and luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9.

Agrose gel electrophoresis of RNA of pMG76e-L-ZS9 and luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9 strains.

Evaluation of data quality of pMG76e-L-ZS9.

Evaluation of data quality of luxS-pMG76e-L-ZS9.