Abstract

Parenthood has strong effects on people’s life. Some of these effects are positive and some negative and may influence the decision of having other children after the first. Demographic research has only marginally addressed the relationship between subjective well-being and fertility, and even less attention has been reserved to investigate how the subjective experience of the first parenthood may influence the decision to have a second child. Performing log-logistic hazard models using HILDA panel data (2001–2012), changes in couples’ objective life conditions and satisfaction within family and work domains after the first childbirth are related to the timing of the transition to the second parenthood. Results show that partners adopting traditional gender specialization in roles proceed quicker to the second child; however, experiencing dissatisfaction in reconciling, in the couple’s relationship and in the work domain negatively affects mothers’ probability of having a second child in the future.

Keywords: Fertility, Second child, Life satisfaction, Work–family reconciliation, Hazard models

Introduction

Many children often ask parents for a little brother or sister—indeed, they figure out how enjoyable the company of a little pal would be. However, do the parents share the same expectations in terms of joy and readiness for a second child? The answer to this question entails a complex decision process and requires the potential parents to consider several aspects of their life, ranging from economic to individual concerns. While it is a joyful event, childbearing has radical consequences on the new parents’ life, whose attention must now orbit around the needs of the baby. Especially during early childhood, when childcare is intense, the new parents must swap time from leisure and social activities to childcare, which not always entail positive experiences—such as waking up during the night to attend or to feed the baby. Additionally, any potential mismatch between the new parents’ expected and actual commitments in different life dimensions (e.g. love relationship, family, and work) may exacerbate stress. In sum, the birth of a child is likely to have a considerable impact on individuals’ subjective well-being (SWB hereafter). The impact may vary from positive to negative, depending on whether the joyful or the stressing components of childcare prevail over the others. The existing literature suggests that, in the short run after the birth, parents’ SWB tends to be lower than before the birth (Pollmann-Schult 2014; Margolis and Myrskylä 2011, 2014; Frijters et al. 2011). However, over time this negative effect weakens. A crucial point, on which this paper focuses, is that the experience—either positive or negative—of becoming parent first time may affect the couple’s decision about having other children in the future. Indeed, experienced and anticipated well-being will influence individuals’ decision-making processes, and among them fertility choices. People engage in behaviours that they expect or know will increase—or at least not reduce—their SWB (Kahneman and Krueger 2006). In this sense, the first childbirth is the first informative experience about parenting and its consequences on parents’ SWB. The effect on parents’ SWB of having offspring has been extensively addressed by the psychology and demography literature. On the contrary, the effect of SWB on fertility behaviour has been little studied by demographers (Aassve et al. 2015; Cowan et al. 1985; Diener et al. 1999; Billari and Kohler 2009; Myrskylä and Margolis 2014; Margolis and Myrskylä 2015). Further, only general attention has been dedicated to how previous parental experience can affect fertility decisions (Newman 2008).

This study focuses on the way the experience of the first child becomes a force that shapes the decision to have the second child. Using unique features of the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) panel survey, I consider the unexpected difficulties of childbearing and a large set of subjective and objective changes in the family and working life after the arrival of the first child as indicators, respectively, of the process of anticipation and adjustment to parenthood. The main hypothesis is that unpredicted difficulties and a more difficult adjustment to parenthood make the transition to the second child less probable over time. Although the issue is particularly relevant in contexts of low fertility, Australia is an interesting case, as, next to the absence of a set of policies for working mothers, in this country the adoption of a traditional specialization of gender roles is a common path once couples have become parents. This makes the transition to parenthood a strong one for many, thereby decreasing parents’ SWB (Frijters et al. 2011).

Literature Review

The Arrival of the First Child and the Changes in SWB

Changes in SWB across childbirth are indicators of the importance of the event in the individual’s life. Longitudinal studies offer empirical evidence of changes in SWB across first childbirth in several Western countries (Angeles 2010; Clark et al. 2008; Pollmann-Schult 2014; Margolis and Myrskylä 2011; Myrskylä and Margolis 2014; Frijters et al. 2011). Their results are consistent in one aspect, namely that the arrival of the first child is anticipated by an increase—on average—of parents’ SWB, and followed by a short-term decrease in SWB. Even though evidence of anticipation and adaptation is confirmed on average, empirical findings do not always show adaptation to childbirth across groups with different socio-demographic characteristics. Such differences arise because individuals have different resources available to adjust to the big changes brought on by the arrival of the newborn.

The process of anticipation mirrors the changes in SWB during the pre-birth period and represents the impact of the birth before it actually has happened. The anticipatory effect is consequently driven by expectations (Frijters et al. 2011). Potentially, anticipation can raise positive or negative feelings, depending on the kind of expectation. For childbearing, positive anticipation starting from one or two years before the birth is reported in a number of studies (Le Moglie et al. 2015; Balbo and Arpino 2016; Clark et al. 2008; Myrskylä and Margolis 2014).

At least in Australia, first-time expectant mothers appear—on average—too optimistic in their expectations about the future with the child. After the birth, in fact, women more than men experience unexpected difficulties mainly because of the unbalanced overload of domestic tasks on them after the transition to the first parenthood (Dempsey 1997; Craig and Siminski 2010). What certain studies reveal is that unexpected difficulties and unmet expectations after childbirth tend to reduce marital satisfaction (Belsky and Rovine 1990; Luppi 2014) and create conflicts in the couple (Belsky 1985), at least in the short term.

The ability to solve or prevent conflict and to adjust to parenthood is mirrored by the changes in subjective (adaptation) and objective (work–family reconciliation) measured after the childbearing event. In the short-term, individuals’ SWB tend to decrease, whereas its extent depends on the personality, the gender and the socio-economic characteristics of the individual (Le Moglie et al. 2015). In particular, mothers of an older age and higher socio-economic status usually adapt better (Clark et al. 2008; Frijters et al. 2011; Myrskylä and Margolis 2014). The reason might be that older parents with higher education and income have more social and economic resources and maturity to face the negative impact of the family–work reconciliation on the couple’s relationship functioning. The overload of tasks that the new arrival brings requires a new accordance in the couple about how to share the domestic activities. In this situation, finding a new equilibrium in the short-term might become a source of conflict or at least dissatisfaction in the couple (Cowan et al. 1985; Cox et al. 1999; Twenge et al. 2003; Lawrence et al. 2007; Luppi 2014, Newman 2008). The fact that the drop in marital satisfaction—and in life satisfaction in general—is temporary suggests that, after a period of shock, where the previous life routine is broken by the arrival of the child, couples find a new balance, adapting to the new situation practically and psychologically.

The SWB Across the First Birth and Its Effect on Future Fertility

We know very little about how SWB can affect future fertility choices. The literature indicates that an increased level of life satisfaction is a prerequisite for a higher propensity to have a/another child with consistent results across countries (Aassve et al. 2012; Billari 2009; Billari and Kohler 2009; Kohler et al. 2005; Le Moglie et al. 2015; Parr 2010; Perelli-Harris 2006; Tanturri and Mencarini 2008). At the same time, the adaptation to the first child is positively linked to a higher probability of experiencing the second birth (Myrskylä and Margolis 2014).

However, childbirth brings important changes in several dimensions of parents’ life, and the process of adjustment to parenthood involves necessarily psychological adaptation and practical reconciliation among all these life spheres. For this reason, a general indicator of life satisfaction is too broad to be responsive to changes in satisfaction with specific life domains (Saris and Ferligoj 1995; Veenhoven 1996; Cummins 1996). As a number of studies reveal, dimensions of life satisfaction tend to change and adapt more to life circumstances than a general indicator, which is usually more stable during the life course (Veenhoven et al. 1993; Diener et al. 1999). This means that the relationship between satisfaction with life and childbirth is more visible if attention is focused on evaluations made on single dimensions of life. According to this perspective, there is a complementary but very fragmentary literature that specifically looks at the effect of anticipation and adjustment in first-time parent’s life domains on future fertility behaviours.

Recent studies confirm that people who have higher expectations of happiness from having a child are more likely to have one in the short term and that the additional happiness that parents anticipate from having a child facilitates childbearing decisions (Billari and Kohler 2009). Moreover, its effect depends on parity (Margolis and Myrskylä 2011), because those who have already had children will learn from their experiences. In this sense, the arrival of a first child—i.e. the transition to parenthood—is a unique event, and the lack of previous experiences makes predictions more uncertain. Goldscheider et al. (2013), in their study on a sample of Swedish couples, find that unmet expectations about gender equality after the transition to parenthood have a negative impact on higher parity. In particular, the presence of “inconsistency” between previous ideal expectations and the reality of an unequal gender division of roles after the arrival of a first child reduces the probability of a transition to a second child.

These results support the literature showing that one of the main sources of conflict in the couple is rooted in the preferences about housework and childcare (Coltrane 2000). While the experience of work–family conflict is especially linked to SWB trajectories across childbirth (Matysiak et al. 2015), it has been shown that parents’ ability to reconcile and adapt to the overload of new tasks is related to their future fertility choices. A match between the father’s contribution to childcare and housework and the partner’s preferences positively affects couple’s fertility. This relationship has been found both in a gender-traditional country such as Italy (Del Boca 2002) and in a more gender-egalitarian country such as Sweden (Goldscheider et al. 2010). Even if it is known that there is a relationship between the level of egalitarianism in the couple and the propensity to realize a higher parity (Puur et al. 2008), the relationship with satisfaction with the actual share of the load in both work and family still needs deeper analysis.

Moreover, being satisfied with the partners’ participation in domestic tasks also depends on the mothers’—and fathers’—involvement in the labour market. The ability to reconcile work and family easily in dual-earner couples is the most important prerequisite to keep a good relationship quality. As reported in a number of studies, while the loss in marital satisfaction at the arrival of the first child is associated with difficulties in reconciling family and work (Gallie and Russel 2008), it has been found to decrease also the probability of experiencing a second birth (Kalmuss et al. 1992; Ruble et al. 1988; Campione 2008).

Data and Method

The Sample

Using the first twelve waves of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) panel survey (2001–2012), a sample of 436 couples has been selected. They are couples of first-time parents in which the women entering the sample are no more than 45 years old. Couples in which at least one of the two partners has experienced a previous childbirth, or couples with twins at the first parity are discarded. The couples are followed from the year of the first pregnancy. The data set is prepared for an event history analysis, with retrospective information on the previous year available for each time period. Some couples can be followed for a maximum of 10 years after the birth of the first child, but regression models have been run up to year 8, when only 32 couples remain in the sample. A time variable counts the years passing since the year of the birth of the first child. The time “at risk” starts at time 0 (year of birth of the first child), when our sample is constituted by 436 couples. At this time, the newborn child is less then 1 year old and couples become “at risk” of experiencing a second pregnancy. Right censoring is caused by sample attrition, the experience of a second pregnancy (180 cases), or the dissolution of the couple (29 cases).

The Transition to the Second Child and Its Main Predictors: Anticipation and Adjustment to First Parenthood

Transition to the Second Child

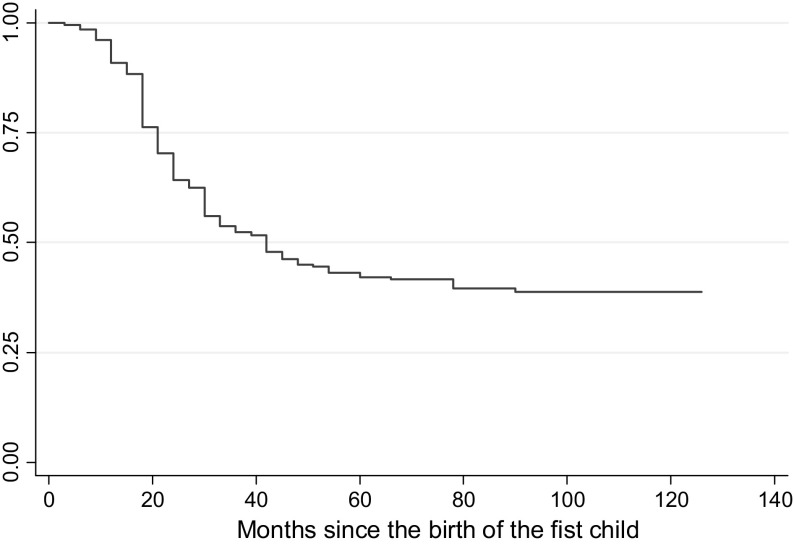

In this study, transition to the second child is operationalized as the occurrence of the second pregnancy. It is a dummy variable that takes value 1 in the year of the occurrence of the second pregnancy and 0 otherwise. In Fig. 1, looking at the survival distribution of the dependent variable since the year of the birth of the first child, we can see that the big drop is from time 2 to time 3, when the first child is already 2 years old, which means that for most of the couples the transition to the second child happens quite soon after the first birth.

Fig. 1.

Survival Kaplan–Meier estimate of the transition to the second child (over time since the first birth)

Anticipation of Difficulties in Parenthood

People anticipate life events when they create expectations about how the different aspects of their lives will change after the occurrence of the event. In HILDA, the indicator of poor anticipation is collected annually after the arrival of the first child, where parents state whether they are facing unexpected difficulties in parenthood (see Appendix, Tables 6, 7). The values range from 1—no unexpected difficulties are experienced—to 7—parents experience high unexpected difficulties. I expect this indicator to be negatively associated with the transition to the second child.

Table 6.

Variables for adjustment to parenthood in family and work life spheres

| Anticipation | ||

| Unexpected difficulties in parenthood | Being a parent is harder than I thought it would be | 1 = Completely disagree; 7 = Completely agree |

| Adjustment | ||

| Adjustment to parenthood in family life | I’m doing more than my fair share of childcare | 1 = I do much more than my fair share; 5 = I do far less than my fair share |

| I’m doing more than my fair share of housework | 1 = I do much more than my fair share; 5 = I do far less than my fair share |

|

| Satisfaction with the partner relationship | 0 = Completely unsatisfied; 10 = Completely satisfied |

|

| Satisfaction with the free time | 0 = Completely unsatisfied; 10 = Completely satisfied |

|

| Adjustment to parenthood at work | Satisfaction with the employment opportunities | 0 = Completely unsatisfied; 10 = Completely satisfied |

| Satisfaction with the flexibility to manage work–family balance | 0 = Completely unsatisfied; 10 = Completely satisfied |

|

| I had to turn down some work opportunities (after the arrival of the child) | 1 = Strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree |

Table 7.

Distribution of the main covariates in the sample (Total sample N = 1498)

| Mean | SE | |

|---|---|---|

| Anticipation | ||

| Unexpected difficulties in parenthood | ||

| Women | 4.1 | 0.07 |

| Men | 3.5 | 0.06 |

| Adjustment | ||

| Satisfaction with | ||

| Overall life | ||

| Women | 8.1 | 0.03 |

| Men | 8 | 0.04 |

| Partner relationship | ||

| Women | 8.5 | 0.06 |

| Men | 8.6 | 0.05 |

| Employment opportunities | ||

| Women | 7.3 | 0.06 |

| Men | 7.5 | 0.06 |

| Financial situation | ||

| Women | 6.7 | 0.06 |

| Men | 6.6 | 0.06 |

| Flexibility to balance work–family | ||

| Women | 7.7 | 0.07 |

| Men | 7.3 | 0.07 |

| Unfair share of housework | ||

| Women | 3.7 | 0.04 |

| Men | 2.6 | 0.03 |

| Unfair share of childcare | ||

| Women | 3.7 | 0.04 |

| Men | 2.5 | 0.03 |

| I had to turn down work opportunities | ||

| Women | 1.8 | 0.07 |

| Men | 2.6 | 0.06 |

The first evidence from the sample shows that more women than men face unexpected difficulties in parenthood. More than half of the women in the sample experiences unmet expectations (women scoring more than 4 on this variable), while only 20–30 % of fathers experience unexpected difficulties in parenting. The proportion of mothers and fathers declaring unmet expectations about the hardness of parenthood increases with the passing of time especially among couples remaining with one child.

Work–Family Adjustment to Parenthood

HILDA provides indicators of objective and subjective adjustment to parenthood in work and family life domains (see Appendix, Tables 6, 7). In particular, it includes the time spent and shared by the partners in doing housework and childcare. The subjective adjustment is covered by satisfaction with the partner relationship, satisfaction with the amount of free time and the perception of a fair share of housework and childcare in the couple. Because the last two variables are anchored in the middle of the scale, they have been re-operationalized in three dummy variables:

Declaring one does more than one’s fair share of housework/childcare: if the original variables score more than 3.

Declaring one does less than one’s fair share of housework/childcare: if the original variables score less than 3.

Declaring one does one’s fair share of housework/childcare: if the original variables score 3.

I hypothesize that an equal sharing of domestic tasks and positive subjective evaluation of the adjustment in family dimensions accelerate the transition to the second child.

In terms of reconciliation in the work sphere, I consider whether the parent had to turn down any work opportunities because of the arrival of the child. The correspondent subjective predictor included in the analysis is represented by satisfaction with employment opportunities. Other satisfaction variables in the work domain are also considered, such as satisfaction with the flexibility to balance family and work, the type of job, the pay, the security of the job and the working hours. An additional included covariate, that is the correspondent subjective predictor of the level of income, is satisfaction with the financial situation.

A high level of satisfaction in the work domain and the flexibility to balance family and work commitment are expected to increase the probability of experiencing the second birth in the short run.

Control Variables

The usual control variables in fertility studies have been included in the models (see Appendix, Table 8). In addition, we also include personality traits. These control for potential genetic predisposition of individuals to react to life events differently, but also differ in their expectations and hence anticipation (Eaves et al. 1990; Jokela et al. 2009, 2011; Kohler et al. 1999). In this sense, they shape both latent fertility motivation and the way situational factors can modify individuals’ fertility intentions, expectations and behaviour. The questions for measuring personality traits in HILDA appear in only two waves (waves 5 and 9). Personality traits have been included in the analysis as time invariant,1 taking the means between the values in the two waves. HILDA includes the 36 items of the TDA Five Factors Personality Inventory. All five scales associated with the five factors reach adequate levels for normality, construct validity, internal consistency and external correlates (Losoncz 2007). With the combination of the five personality traits, every individual is assigned a score that is almost unique and as such acts to account for potential unobservable heterogeneity.

Table 8.

Distribution of the control variables in the sample (total sample N = 1498)

| Couples | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| % | Mean | SE | |

| Age | |||

| Women: mean age 1st birth | 29 | 0.2 | |

| Men: mean age 1st birth | 31 | 0.3 | |

| Diff. ages (man–woman) | 1.7 | 0.1 | |

| Educationa | |||

| High homogamy | 25 | ||

| She higher | 20 | ||

| He higher | 8 | ||

| Low homogamy | 47 | ||

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 85 | ||

| Occupational statusb | |||

| Women: employed | 61 | ||

| Among employed women | 36 | ||

| Full-time | |||

| Part-time | 64 | ||

| Men: employed | 96 | ||

| Among employed men | |||

| Full-time | 94 | ||

| Part-time | 6 | ||

| Equivalized disposable household income | 17.219 $AU | 541.6 | |

| Domestic tasks | |||

| Women: hoursc housework | 4.5 | 0.2 | |

| Women: hoursd childcare | 43 | 0.9 | |

| Share housework (wo./man) | 2.1 | 0.1 | |

| Men: hours housework | 2.5 | 0.1 | |

| Men: hours childcare | 16 | 0.5 | |

| Share childcare (wo./man) | 2.4 | 0.1 | |

| Hours outsourced childcare (in a week) | 6.4 | 0.3 | |

aHigh homogamy: both partners tertiary education; low homogamy: both partners secondary or primary education

bUnemployment and inactivity has been considered together because of the low unemployment rates in Australia (about 4–5 % for both women and men in 2005)

cHours spent in a week doing housework

dHours in a week doing childcare

Method: The Log-Logistic Hazard Model

The probability of experiencing the transition to the second child is modelled using a log-logistic regression. The choice of a parametric survival model is mainly due to the sample size, which is too small to allow a Cox—nonparametric or semi-parametric—hazard model or a nonparametric discrete time hazard model. The use of a continuous specification for time is legitimised by the operationalization of the survival time, measured in trimesters since the birth of the first child, and by the nature of the process, as the probability of experiencing a second pregnancy can be interpreted as being continuous in time (Tavares 2010).

The log-logistic parameterization is the most commonly used, and it is recommended for studying demographic events such as divorce, marriage and childbirth (Blossfeld et al. 2007). It also allows for testing the hypothesis of a monotonic vs. non-monotonic hazard function, making log-logistic distribution more flexible than other types such as Gompertz or Weibull,2 which only allow monotonic distribution of the hazard.

The estimated empty log-logistic hazard model for the transition to the second child in this case is reported in Table 1. As expected, the hazard function is bell shaped (the coefficient is positive).

Table 1.

Empty log-logistic hazard model for the transition to the second child

| Coeff | SE | |

|---|---|---|

| Constant | 5.805*** | .167 |

| Ln gamma | 0.147*** | .062 |

| Gamma | 1.158 | .072 |

N = 1498

* p ≤ .05; ** p ≤ .01; *** p ≤ .001

The main predictors are introduced into the model in a stepwise manner, starting with the anticipation process, the adjustment to parenthood in family and in work domain, and a complete model with both set of predictors.

Results

Results from the models for the transition to the second birth are consistent with the literature that shows how older and more educated parents make a quicker progression to the second child if compared to younger parents and couples where both partners have a low level of education. In particular, couples which show high homogamy in education have a hazard rate four times that of couples with low homogamy. The indicators of anticipation and adjustment are only marginally affected by education and age.

Anticipation to Parenthood: Unexpected Difficulties

Descriptive results showed that experiencing unexpected difficulties after the first childbirth is more typical among women than men. The reason might be the higher involvement of mothers in childcare responsibilities, especially during the first year of the child’s life. If a mother faces unexpected difficulties in parenthood, this has a negative effect also on the couple’s probability of experiencing the second birth in the short run, significantly increasing the time before the arrival of the second child (see Table 2). Because the hazard ratio for continuous variables applies to a unit of difference, the probability of experiencing the second birth next year decreases by 7 % on average for each increase on the scale of unexpected difficulties.

Table 2.

Log-logistic hazard model (hazard ratios) for the transition to the second pregnancy with the predictors for the anticipation of the difficulties to parenthood

| Model 1 N = 1498 |

Model 2 N = 1498 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Anticipation | ||

| Unexpected difficulties (men) | 1.04 | |

| Unexpected difficulties (women) | 0.93** | |

| Both unexpected difficulties | – | 1.13 |

| She unexpected difficulties | – | 0.74* |

| He unexpected difficulties | – | 1.17 |

| Control variables | ||

| Education | ||

| High ed. homogamy | 4.43*** | 4.55*** |

| She more educated | 2.41*** | 2.43*** |

| He more educated | 2.97*** | 2.94*** |

| Age | ||

| Age (men) | 0.88*** | 0.89*** |

| Age (women) | 0.93*** | 0.92*** |

| Employment | ||

| He unemployed/inactive | 0.62 | 0.62 |

| He employed part-time | 1.01 | 0.98 |

| She unemployed/inactive | 1.02 | 1.01 |

| She employed part-time | 0.68** | 0.67** |

| Health | ||

| Objective health (men) | 1.15 | 1.18 |

| Objective health (women) | 0.86 | 0.87 |

| Income | ||

| Income: 2nd quartile | 0.70** | 0.71* |

| Income: 3rd quartile | 0.53*** | 0.53*** |

| Income: 4th quartile | 0.54*** | 0.55*** |

| Outsourced childcare | ||

| High use of outsourced childcare | 1.19 | 1.16 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 1.35 | 1.35 |

| Personality traits | ||

| Extraversion (women) | 1.05 | 1.05 |

| Agreeableness (women) | 0.98 | 0.99 |

| Conscientiousness (women) | 1.02 | 1.02 |

| Emotional stability (women) | 0.94 | 0.92*** |

| Openness (women) | 0.78*** | 0.77 |

| Extraversion (men) | 1.05 | 1.05 |

| Agreeableness (men) | 0.98 | 0.98* |

| Conscientiousness (men) | 0.87** | 0.87 |

| Emotional stability (men) | 1.03 | 1.03 |

| Openness (men) | 1.06 | 1.06 |

| Constant | 11.58** | 14.72*** |

Reference categories: both non-unexpected difficulties; low education homogamy; he/she employed full time; income 1st quartile; cohabiting; little or no use of outsourced childcare

+ p ≤ .1; * p ≤ .05; ** p ≤ .01; *** p ≤ .001

The results are similar when considering the relative experience of the two partners: couples where the woman experiences more unexpected difficulties than her partner have a lower probability of making the transition to the second child (30 % lower) than couples in which neither partner is experiencing unmet expectations.

Adjustment to Parenthood in Family Life

The arrival of a newborn implies a substantial increase in the domestic workload, which weighs disproportionately between partners, falling predominantly onto women’s shoulders. In our sample, this is confirmed especially true during the first year of the child’s life, when most mothers abandon (at least temporarily) the labour market, to take care of their children.3 At the same time, many fathers increase their involvement in household chores, although the gap between women and men’s involvement remains rather large, with women spending on average twice as much time as men doing housework (see Appendix, Table 8).

This sudden increase in domestic tasks plus the new parental responsibilities represent difficult issues for the couple’s adjustment to the transition to parenthood, which affects also the timing of the second birth. In this sense, the amount and the share of time spent by partners on housework and childcare can be a critical variable for understanding the progression to the second child. Results show (Table 3) that the more the woman is doing in terms of both housework and childcare, the higher is the probability for a second pregnancy. Interestingly, doing an equal share of housework increases (30 % more) quite significantly the time for the transition to the second child.4 In other words, partners’ specialization in traditional gender roles seems to favour a quick “objective” adjustment to the transition to second-order parity.

Table 3.

Log-logistic hazard model (hazard ratios) for the transition to the second pregnancy with the predictors for the adjustment in the family domain

| Model 1 N = 1462 |

Model 2 N = 1462 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Adjustment in family | ||

| Satisfaction with the relationship with the partner | ||

| Satisfaction with the relationship (women) | – | 1.20*** |

| Satisfaction with the relationship (men) | – | 0.97 |

| Judgement on fair share housework | ||

| Equal share housework (women) | – | 1.03 |

| Less than fair share housework (women) | – | 0.47+ |

| Equal share housework (men) | – | 1.49*** |

| More than fair share housework (men) | – | 1.23 |

| Time spent in doing housework | ||

| Hours/week doing housework (women) | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Hours/week doing housework (men) | 1.01 | 1.01 |

| Share hours/week housework (W/M) | 1.04+ | 1.03 |

| Judgement on fair share childcare | ||

| Equal share childcare (women) | – | 1.13 |

| Less than fair share childcare (women) | – | 0.66 |

| Equal share childcare (men) | – | 0.60*** |

| More than fair share childcare (men) | – | 0.99 |

| Time spent in doing childcare | ||

| Hours/week doing childcare (women) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Hours/week doing childcare (men) | 1.01*** | 1.01*** |

| Share hours/week childcare (W/M) | 1.02** | 1.02* |

| Control variables | ||

| Education | ||

| High ed. homogamy | 4.19*** | 4.19*** |

| She more educated | 2.27*** | 2.39*** |

| He more educated | 3.16*** | 3.45*** |

| Age | ||

| Age (men) | 0.88*** | 0.88*** |

| Age (women) | 0.94*** | 0.94*** |

| Employment | ||

| He unemployed/inactive | 0.62 | 0.63 |

| He employed part-time | 0.95 | 1.01 |

| She unemployed/inactive | 0.76 | 0.72* |

| She employed part-time | 0.56*** | 0.57*** |

| Health | ||

| Objective health (men) | 1.26 | 1.20 |

| Objective health (women) | 0.84 | 0.98 |

| Income | ||

| Income: 2nd quartile | 0.72** | 0.68** |

| Income: 3rd quartile | 0.56*** | 0.56*** |

| Income: 4th quartile | 0.52*** | 0.53*** |

| Outsourced childcare | ||

| High use of outsourced childcare | 1.31+ | 1.35* |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 1.29 | 1.29 |

| Personality traits | ||

| Extraversion (women) | 1.04 | 1.03 |

| Agreeableness (women) | 0.99 | 1.00 |

| Conscientiousness (women) | 1.03 | 1.01 |

| Emotional stability (women) | 0.93 | 0.90 |

| Openness (women) | 0.78*** | 0.80*** |

| Extraversion (men) | 1.08 | 1.06 |

| Agreeableness (men) | 1.00 | 0.97 |

| Conscientiousness (men) | 0.89+ | 0.86** |

| Emotional stability (men) | 1.06 | 1.02 |

| Openness (men) | 1.06 | 1.04 |

| Constant | 3.52 | 2.52 |

Reference categories: more than equal share of housework/childcare; both non-unexpected difficulties; low education homogamy; he/she employed full time; income 1st quartile; cohabiting; little or no use of outsourced childcare

+ p ≤ .1; * p ≤ .05; ** p ≤ .01; *** p ≤ .001

Asking whether “subjective” adjustment weighs on fertility decisions means taking into account the role of judgement of the share of domestic tasks. It might be that the couple’s perception of fairness of the distribution of domestic tasks counts more than the actual share. Starting from the judgement about the share of housework, couples in which men and women believe they do their fair share quickly progress to the second child. Even though the result is especially significant for men, the transition to the second child is 30 % more probable in couples where the two partners agree they do their fair share, compared to couples where women believe they do more and men believe they do less than their fair share. The results do not change even when the actual time dedicated to housework is checked, while coefficients for the time spent on housework are no longer significant. In this sense, what seems to be important for understanding the timing of the second pregnancy is more the judgement than the actual share.

As regards judgement on the share of childcare, couples in which the woman judges she does her fair share, the hazard ratio is significantly higher. On the contrary, where the man judges he does his fair share, the hazard rate is considerably lower (30 %). The first results suggest that household tasks might be subjectively gendered among these couples. In other words, judgement about the “fairness” of the share of domestic tasks does not necessarily mean that the couple is actually sharing the housework fully. Instead, it reflects the perception of doing more or less of the “expected” involvement in these tasks. From these results, it appears that the expected role of women is to be responsible for more than 50 % of the housework, and especially so when it comes to childcare. In fact, couples in which men perceive they are doing their “fair share” of childcare tend to postpone the second birth. Looking at the signs of the coefficients of the time spent on housework and childcare by both partners, it seems that while men participating more in housework increase couples’ chances to proceed to the second child, this is not the case if men participate more in childcare.

There might be an encompassing process of adjustment in the family domain including at least part of the overall adjustment: the adjustment in the couple’s relationship. According to the literature, most of the changes in a couple’s life after the arrival of the first child strongly affect the quality of their relationship. Couples with problems regarding how their relationship is functioning face more obstacles when planning a second child. However, it seems that only women’s experienced satisfaction with the partner relationship matters for the timing of the second pregnancy. In particular, a high level of relationship satisfaction makes the second birth5 20 % more probable to happen.

Adjustment to Parenthood in Work Life

Among Australian couples, the typical path of work arrangement after the onset of parenthood is one in which one partner works full time, whereas the other works part time, where the mother is usually the part-time worker. Considering that the proportion of individuals employed full time among childless people is almost the same for women and men, we can observe how the transition to parenthood might imply difficult compromises for working mothers. In the light of this, we can also better interpret the results of our estimates.

The work arrangement of just the mother has a significant impact on the decision to have a second child. In particular, being employed in a part-time job increases the time for the transition to the second child, compared to couples in which mothers are inactive or employed full time. Nevertheless, including the consequences of the arrival of the first child on their career (i.e. turning down career opportunities), the coefficient loses significance. Moreover, if the woman has turned down some work opportunities, the transition to the second child becomes less probable (difference of 1 unit on the predictor means the transition is 7 % less probable) at least in the short run (see Table 4, all couples).

Table 4.

Log-logistic hazard model (hazard ratios) for the transition to the second pregnancy with the predictors for the adjustment in the work domain

| Model 1: all couples N = 1454 |

Model 2: dual earners N = 856 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Adjustment in work | ||

| Satisfaction with the flexibility to balance family–work | ||

| Sat. flexibility balance family–work (women) | 1.08** | |

| Sat. flexibility balance family–work (men) | 1.01 | |

| Satisfaction with the employment opportunities | ||

| Sat. employment opportunities (women) | 1.15*** | 1.06 |

| Sat. employment opportunities (men) | 0.98 | 1.06 |

| Turn down work opportunities after childbirth | ||

| Turn down work opportunities (women) | 0.92** | 0.93+ |

| Turn down work opportunities (men) | 0.98 | 0.93 |

| Control variables | ||

| Education | ||

| High ed. homogamy | 4.16*** | 2.79*** |

| She more educated | 2.04*** | 1.36 |

| He more educated | 3.01*** | 2.19*** |

| Age | ||

| Age (men) | 0.89*** | 0.89*** |

| Age (women) | 0.92*** | 0.94** |

| Employment | ||

| He unemployed/inactive | 0.55 | 1.00 |

| He employed part-time | 0.89 | 0.82 |

| She unemployed/inactive | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| She employed part-time | 0.69** | 0.61*** |

| Health | ||

| Objective health (men) | 1.23 | 1.25 |

| Objective health (women) | 0.86 | 0.94 |

| Income | ||

| Income: 2nd quartile | 0.63*** | 0.58*** |

| Income: 3rd quartile | 0.54*** | 0.63** |

| Income: 4th quartile | 0.56*** | 0.75 |

| Outsourced childcare | ||

| High use of outsourced childcare | 1.24 | 1.37** |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 1.42 | 1.50 |

| Personality traits | ||

| Extraversion (women) | 1.02 | 0.97 |

| Agreeableness (women) | 0.98 | 0.89 |

| Conscientiousness (women) | 0.97 | 0.96 |

| Emotional stability (women) | 0.93 | 0.93 |

| Openness (women) | 0.86* | 0.92 |

| Extraversion (men) | 1.01 | 0.97 |

| Agreeableness (men) | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Conscientiousness (men) | 0.85** | 0.82** |

| Emotional stability (men) | 1.01 | 1.02 |

| Openness (men) | 1.05 | 1.00 |

| Constant | 8.40** | 10.06* |

Reference categories: both non-unexpected difficulties; low education homogamy; he/she employed full time; income 1st quartile; cohabiting; little or no use of outsourced childcare

+ p ≤ .1; * p ≤ .05; ** p ≤ .01; *** p ≤ .001

The difficulties of reconciling family and work weigh especially on mothers. In fact, satisfaction with employment opportunities for mothers is an important positive predictor for realizing a faster transition to the second child (15 % more probable for an increase of 1 point of satisfaction).

Among dual-earner couples (see Table 4, dual-earner couples), only mothers’ satisfaction with the flexibility to balance work and family commitment is positively related to the realization of the second pregnancy in the short run after the first. Irrespective of which parent, being satisfied with their leisure time contributes to making the transition to the second child quicker. The fact that other work-related satisfaction (pay, security, kind of job) and satisfaction with the financial situation do not influence significantly the timing of the second birth suggests that the main difficulties in work adjustment to the first parenthood are specifically related to the challenging trade off between family and work for mothers.

The Complete Model: Anticipation of Difficulties and Adjustment to Parenthood in Family and Work

According to the existing literature, the work–family reconciliation is the real obstacle for dual-earner couples. A model including all the predictors for the difficulties in adjusting to parenthood sheds light on what makes the transition to the second child most difficult. The first model (Table 5, all couples) estimates the probability of the transition to the second child for all the couples; instead, the second model (Table 5, dual-earner couples) is specific for dual-earner couples.

Table 5.

Log-logistic hazard model (hazard ratios) for the transition to the second pregnancy with the predictors for the anticipation of the difficulties of parenthood, and the adjustment in the family and work domain

| Model 1: all couples N = 1454 | Model 2: dual earners N = 856 | |

|---|---|---|

| Anticipation | ||

| Unexpected difficulties (women) | 0.94* | 0.90*** |

| Unexpected difficulties (men) | 1.05 | 1.12*** |

| Adjustment in work | ||

| Satisfaction with the flexibility to balance family–work | ||

| Sat. flexibility balance family–work (women) | 1.07* | |

| Sat. flexibility balance family–work (men) | 1.03 | |

| Satisfaction with the employment opportunities | ||

| Sat. employment opportunities (women) | 1.13*** | 1.05 |

| Sat. employment opportunities (men) | 0.98 | 1.06 |

| Turn down work opportunities after childbirth | ||

| Turn down work opportunities (women) | 0.94+ | 0.96 |

| Turn down work opportunities (men) | 0.98 | 0.91** |

| Adjustment in family | ||

| Satisfaction with the relationship with the partner | ||

| Sat. with partner relationship (women) | 1.18*** | 1.12** |

| Sat. with partner relationship (men) | 0.98 | 1.00 |

| Judgement on fair share housework | ||

| Equal share housework (women) | 1.05 | 1.01 |

| Less than fair share housework (women) | 0.46+ | 0.94 |

| Equal share housework (men) | 1.49*** | 1.54** |

| More than fair share housework (men) | 1.29 | 1.72** |

| Time spent in doing housework | ||

| Hours/week doing housework (women) | 0.99 | 1.01 |

| Hours/week doing housework (men) | 1.01 | 1.01 |

| Share hours/week housework (W/M) | 1.03 | 1.03 |

| Judgement on fair share childcare | ||

| Equal share childcare (women) | 1.06 | 0.96 |

| Less than fair share childcare (women) | 0.44 | 0.49 |

| Equal share childcare (men) | 0.58*** | 0.61*** |

| More than fair share childcare (men) | 1.02 | 0.97 |

| Time spent in doing childcare | ||

| Hours/week doing childcare (women) | 1.01*** | 1.01*** |

| Hours/week doing childcare (men) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Share hours/week childcare (W/M) | 1.02** | 1.02+ |

| Control variables | ||

| Education | ||

| High ed. homogamy | 4.01*** | 2.60*** |

| She more educated | 2.03*** | 1.38 |

| He more educated | 3.60*** | 2.39*** |

| Age | ||

| Age (men) | 0.88*** | 0.90*** |

| Age (women) | 0.95** | 0.96+ |

| Employment | ||

| He unemployed/inactive | 0.60 | – |

| He employed part time | 0.95 | 0.74 |

| She unemployed/inactive | 0.81 | – |

| She employed part time | 0.63*** | 0.57*** |

| Health | ||

| Objective health (men) | 1.25 | 1.36 |

| Objective health (women) | 1.04 | 0.95*** |

| Income | ||

| Income: 2nd quartile | 0.61*** | 0.54*** |

| Income: 3rd quartile | 0.57*** | 0.62** |

| Income: 4th quartile | 0.57*** | 0.79 |

| Outsourced childcare | ||

| High use of outsourced childcare | 1.37** | 1.51*** |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 1.34 | 1.48 |

| Personality traits | ||

| Extraversion (women) | 0.99 | 0.95 |

| Agreeableness (women) | 1.00 | 0.89 |

| Conscientiousness (women) | 0.96 | 1.01 |

| Emotional Stability (women) | 0.87* | 0.88 |

| Openness (women) | 0.84** | 0.85** |

| Extraversion (men) | 1.03 | 0.99 |

| Agreeableness (men) | 0.94 | 0.92 |

| Conscientiousness (men) | 0.87** | 0.84** |

| Emotional stability (men) | 1.03 | 1.02 |

| Openness (men) | 1.05 | 1.01 |

| Constant | 2.87 | 2.83 |

Reference categories: more than equal share of housework/childcare; both non-unexpected difficulties; low education homogamy; he/she employed full time; income 1st quartile; cohabiting; little or no use of outsourced childcare

+ p ≤ .1; * p ≤ .05; ** p ≤ .01; *** p ≤ .001

In general, most of the difficulties that hinder a fast progression to the second child concern mothers’ adjustment to the arrival of the first child (Table 5, all couples). Experiencing unexpected difficulties in raising a child is still a significant predictor for a lower probability of experiencing the second pregnancy in the short run. However, we also see that a real challenge facing mother (and couples) is the reconciliation process of family and work. Loosing career chances and perceiving difficulties in finding new employment opportunities are the two main sources of uncertainty in the work domain, which might compromise the decision to have an additional child in the short term. The persistence of these results underlines that the transition to motherhood represents a source of worry and uncertainty for mothers who desire to enter or stay in the labour market. That is not the case when parents adopt the traditional specialization in gender roles. In fact, when the woman is doing most of the childcare (see the covariates for the time spent in doing childcare), the probability of having a second child in the short term is higher. The fact that the perception of the fairness of the division of household tasks weighs more on the timing for the transition to the second child than the actual share might reveal that the problem is cultural more than practical. Couples where the man perceives he is doing his equal share of childcare are only half as likely to make the transition to the second child as couples in which he believes he is doing less than his fair share. However, while childcare remains a female prerogative, the fact that the man perceives he is doing a fair share of the housework strongly reduces the time for having an additional child, compared to families in which the man declares he is doing less than his fair share.

In dual-worker couples (Table 5, dual-earner couples), the same path of influence is confirmed, while the results for men are also clearer. In particular, it appears that families in which fathers perceive themselves to be more involved in contributing to the new family needs by doing more housework are also proceeding quickly to the second birth. Meanwhile, mothers’ involvement in childcare remains a strong prerequisite for having an additional child. At the same time, as a consequence of mothers’ (expected) commitment in childcare, the perceived reduction in opportunities in the labour market and the subsequent difficulties in balancing work–family commitment (see also the result for satisfaction with the flexibility to balance family and work commitment) are reasons for postponing the second child.

Conclusion

The onset of parenthood is a turning point in a couple’s life—in which the partners need to find new ways to balance their commitments in family and work—which may reduce their level of SWB. The potential strain imposed through meeting the child’s needs, the difficult compromises between career and family life, and the reduction in the time for leisure make the first years with the newborn less bucolic than often expected by first-time parents. How much the adjustment to parenthood influences couple’s decision of having—and when—a second child is the main question posed in this analysis. What this study adds is the consideration that the changes in SWB, as indicators of adjustment to the first parenthood, might be the reason why some couples stop at the first parity.

Indeed, the firstborn is an unexpected “costly-joy” that is not neutral for the decision of having an additional child. Parents expecting their first child obviously cannot foresee all the challenges of parenthood, and this seems to have consequences especially for mothers. Results highlight that mothers’ adjustment to couple relations, and the family and work spheres, affects the probability fertility progression.

During the first months of a child’s life, childcare weighs more heavily on the mothers’ shoulders than that of fathers’, and this explains why they experience more unexpected difficulties in parenting. However, this disproportionate burden of responsibilities seems to represent one of the reasons for postponing or foregoing the decision to have another child. This can be because—according to the results of this study—childcare is generally considered a mother’s issue, not only limited to the first period of life of the child. The results show that for a quick transition to the second child, a higher involvement in housework is the culturally accepted way for fathers to contribute to the increased load of domestic tasks after the childbirth, conditionally to the fact that childcare should remain mothers’ responsibility.

Consequently, difficulties with childcare sometimes force mothers to reduce their involvement in the labour market, or even to drop out. The possibility to outsource childcare helps dual-earner parents to adjust and proceed quickly to the second child. Nevertheless, formal and informal support with childcare is not always accessible or affordable, and for a relevant number of couples this means that the birth of the first child entails the adoption—at least temporarily—of the traditional specialization in gender roles.

Our results support the conclusion that couple’s specialization is associated with a quicker progression to the second child. The reason relates to mothers’ dissatisfaction with reconciliation. Experiencing difficulties in reconciling and perceiving to lose career prospects reduce significantly the chance to have a second child. However, from this analysis we cannot safely infer that dissatisfaction with reconciling after the first birth indeed affects the total fertility. The small sample size does not allow following couples for a longer period, meaning that we are unable to capture their completed fertility.

Even though we cannot derive conclusions about institutional effects, the fact that couple’s specialization in gender roles makes easier the transition to the second child—compared to dual-earner couples—suggests a lack of an adequate support to working parents. Moreover, Australian policies for working mothers substantially changed in 2011, with the introduction of universal paid parental leave system. A further research effort should explore the effect of this policy change, to see whether it indeed facilitates dual-earner couples adjustment to the first parenthood, shortening the time—or increasing the probability over time—to make the transition to the second child.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the European Research Council under the European ERC Grant Agreement no StG-313617 (SWELL-FER: Subjective Well-being and Fertility, P.I. Letizia Mencarini).

Appendix

Footnotes

Measures on personality are available in HILDA wave 5 and 9. Variability of the predictors has been tested using Wilcoxon signed-rank test, which tests the equality of matched pairs of observations, where the null hypothesis is that the distributions are the same. The results do not support a decision to reject the null hypothesis.

The three models, Gompertz, Weibull and log logistic, were tested and compared based on their AIC. Log logistic was confirmed to fit the data better than the other models.

During the year of the birth of their first child, more than 50 % of the women in the sample are inactive or unemployed, compared to 20 % of the previous and subsequent years. At the same time, the proportion of part-time working mothers is around 50 % during the first year of the child’s life, compared to 18 % during the year of the first pregnancy.

The model has not been reported for parsimony. Here the time until the second child is modelled including the variables for the hours spent in doing housework for both partners, and a dummy variable taking value 1 if the couples are doing their fair share or 0 otherwise.

The inclusion of satisfaction with the partner relationship does not change the magnitude and the significance of the other predictors and vice versa.

This paper uses unit record data from the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. The HILDA Project was initiated and is funded by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS) and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (Melbourne Institute). The findings and views reported in this paper, however, are those of the author and should not be attributed to either DSS or the Melbourne Institute.

References

- Aassve A, Goisis A, Sironi M. Happiness and childbearing across Europe. Social Indicator Research. 2012;108(1):65–86. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9866-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aassve A, Mencarini L, Sironi M. Institutional change, happiness and fertility. European Sociological Review. 2015;31(6):749–765. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcv073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angeles L. Children and Life Satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2010;11(4):523–538. doi: 10.1007/s10902-009-9168-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balbo, N., & Arpino, B. (2016). The role of family orientations in shaping the effect of fertility on subjective well-being: A propensity score matching approach. Demography, 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Belsky J. Exploring individual differences in marital change across the transition to parenthood: The role of violated expectations. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1985;47(4):1037–1044. doi: 10.2307/352348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Rovine M. Patterns of marital change across the transition to parenthood: pregnancy to three years postpartum. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1990;52(1):5–19. doi: 10.2307/352833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Billari FC. The happiness commonality: fertility decisions in low-fertility settings. In: UNECE, editor. How generations and gender shape demographic change. New York: United Nations; 2009. pp. 7–38. [Google Scholar]

- Billari, F. C., & Kohler, H. P. (2009). Fertility and happiness in the XXI century: Institutions, preferences, and their interactions. In Annual meeting of the Population Association of America, Detroit.

- Blossfeld HP, Golsch K, Rohwer G. Event history analysis with stata. New York: LEA; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Campione W. Employed women’s well-being: The global and daily impact of work. Journal of Family and Economic Issues. 2008;29(3):346–361. doi: 10.1007/s10834-008-9107-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AE, Diener E, Georgellis Y, Lucas RE. Lags and leads in life satisfaction: a test of the baseline hypothesis. Economic Journal. 2008;118(529):222–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02150.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coltrane S. Research on household labor: modeling and measuring the social embeddedness of routine family work. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:1208–1233. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01208.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CP, Cowan PA, Heming G, Garrett E, Coysh WS, Curtis-Boles H, Boles AJ. Transitions to parenthood. Journal of Family Issues. 1985;6(4):451–481. doi: 10.1177/019251385006004004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B, Burchinal M, Payne CC. Marital perceptions and interactions across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1999;61(3):611–625. doi: 10.2307/353564. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Craig L, Siminski P. Men’s housework, women’s housework and second births in Australia. Social Politics. 2010;17(2):235–266. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxq004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins RA. The domains of life satisfaction: An attempt to order chaos. Social Indicators Research. 1996;38(3):303–328. doi: 10.1007/BF00292050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca D. The effect of child care and part time opportunities on participation and fertility decisions in Italy. Journal of Population Economics. 2002;15(3):549–573. doi: 10.1007/s001480100089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey K. Inequalities in marriage. Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith H. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:276–302. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LJ, Martin NG, Heath AC, Hewitt JK, Neale MC. Personality and reproductive fitness. Behavior Genetics. 1990;20(5):563–568. doi: 10.1007/BF01065872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frijters P, Johnston PW, Shields M. Life satisfaction dynamics with quarterly life event data. Scandinavian Journal of Economics. 2011;113(1):190–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9442.2010.01638.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallie D, Russel H. Work family conflict and working conditions in Western Europe. Social Indicators Research. 2008;93:445–467. doi: 10.1007/s11205-008-9435-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider F, Bernhardt E, Brandén M. Domestic gender equality and childbearing in Sweden. Demographic Research. 2013;29(40):1097–1126. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2013.29.40. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider F, Oláh LS, Puur A. Reconciling studies of men’s gender attitudes and fertility: Response to Westoff and Higgins. Demographic Research. 2010;22:189. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2010.22.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jokela M, Alvergne A, Pollet TV, Lummaa V. Reproductive behavior and personality traits of the Five Factor Model. European Journal of Personality. 2011;25(6):487–500. doi: 10.1002/per.822. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jokela M, Kivimäki M, Elovainio M, Keltikangas-Järvinen L. Personality and having children: A two-way relationship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96(1):218–230. doi: 10.1037/a0014058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Krueger AB. Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2006;20(1):3–24. doi: 10.1257/089533006776526030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmuss D, Davidson A, Cushman L. Parenting expectations, experiences, and adjustment to parenthood: A test of the violated expectations framework. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1992;54(3):516–526. doi: 10.2307/353238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler HP, Behrman JR, Skytthe A. Partner + children = happiness? The effects of partnerships and fertility on well-being. Population Development Review. 2005;31(3):407–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00078.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler H-P, Rodgers JL, Christensen K. Is fertility behaviour in our genes? Findings from a Danish twins study. Population and Development Review. 1999;25:253–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.1999.00253.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E, Nylen K, Cobb R. Prenatal expectations and marital satisfaction over the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21(2):155–164. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Moglie M, Mencarini L, Rapallini C. Is it just a matter of personality? On the role of subjective well-being in childbearing. Journal of Economic Behaviour and Organization. 2015;117:453–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2015.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Losoncz, I. (2007). Personality Traits in HILDA. Paper presented to HILDA Survey Research Conference, University of Melbourne.

- Luppi, F. (2014). Adjustment to parenthood and partners’ satisfaction with their relationship after the first child. Carlo Alberto Notebooks, working paper no. 389.

- Margolis R, Myrskylä M. A global perspective on happiness and fertility. Population and Development Review. 2011;37(1):29–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis R, Myrskylä M. Parental well-being surrounding first birth as a determinant of further parity progression. Demography. 2015;52(4):1147–1166. doi: 10.1007/s13524-015-0413-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matysiak, A., Mencarini, L., & Vignoli, D. (2015). Work-family conflict moderates the impact of childbearing on subjective well-being. SWELL-FER working paper series, no. 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Myrskylä M, Margolis R. Happiness: Before and after the kids. Demography. 2014;51(5):1843–1866. doi: 10.1007/s13524-014-0321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman LA. How parenthood experiences influence desire for more children in Australia: A qualitative study. Journal of Population Research. 2008;25(1):1–27. doi: 10.1007/BF03031938. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parr N. Satisfaction with life as an antecedent of fertility: Partner + happiness = children? Demographic research. 2010;22(21):635–662. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2010.22.21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perelli-Harris B. The influence of informal work and subjective well-being on childbearing in Post-Soviet Russia. Population Development Review. 2006;32(4):729–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2006.00148.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pollmann-Schult M. Parenthood and life satisfaction: Why don’t children make people happy? Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2014;76:319–336. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puur A, Olah LS, Tazi-Preve MI, Dorbritz J. Men’s childbearing desires and views of the male role in Europe at the dawn of the 21st century. Demographic Research. 2008;19:1883–1912. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.56. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruble DN, Fleming AS, Hackel LS, Stangor C. Changes in the marital relationship during the transition to first time motherhood: Effects of violated expectations concerning division of household labor. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;55:78–87. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.55.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saris WE, Ferligoj A. Life-satisfaction and domain-satisfaction in 10 European countries: Correlation at the individual level. In: Saris WE, editor. A comparative study of satisfaction with life in Europe. Budapest: Eötvös University Press; 1995. pp. 275–279. [Google Scholar]

- Tanturri ML, Mencarini L. Childless or childfree? Paths to voluntary childlessness in Italy. Population Development Review. 2008;34(1):51–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2008.00205.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tavares, L. (2010). Who delays childbearing? The relationships between fertility, education and personality traits. ISER working paper series, no. 17.

- Twenge JM, Campbell WK, Craig A. Parenthood and marital satisfaction: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65(3):574–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00574.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Veenhoven R. Developments in satisfaction-research. Social Indicators Research. 1996;37(1):1–46. doi: 10.1007/BF00300268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Veenhoven, R., Ehrhardt, J., Ho, M. S. D., & de Vries, A. (1993). Happiness in nations: Subjective appreciation of life in 56 nations 1946–1992. Erasmus University Rotterdam.