Abstract

An “East–West” divide in contraceptive use patterns has been identified across Europe, with Western European countries characterized by the widespread use of modern contraception, and Central and Eastern European countries characterized by a high prevalence of withdrawal, the rhythm method, or abortion. Building on the Ready–Willing–Able framework, this study aims to gain more insight into the micro- and macro-level socioeconomic, cultural, and technological determinants underlying contraceptive use. Data from the Generations and Gender Survey (2004–2011) covering four Western and seven Central and Eastern European countries are used, and multinomial multilevel analyses are performed. Results reveal that individuals who intend to delay parenthood are more likely to use any contraceptive method, whereas holding more traditional values and having a lower socioeconomic status are associated with a higher likelihood of using no or only traditional methods. Regional reproductive rights and gender equality interact in complex ways with these associations. At minimum, our results underline the complexity of the processes underlying the persistent difference in contraceptive use across Europe.

Keywords: Contraception, East–West divide, Europe, Comparative research

Introduction

Despite the generally low fertility rates in European societies and the observation that not a single European country has a total fertility rate above population replacement level (Frejka and Sobotka 2008; Eurostat 2015d), contraceptive behavior across Europe varies to a great extent. In Western Europe (WE), contraceptive users almost universally rely on modern methods (UN 2013). 95.5 % use barrier methods, hormonal contraception, or sterilization, whereas only 4.5 % use traditional methods.1 In Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), 77.5 % use modern methods and 22.5 % rely on traditional contraception. Taking all women of reproductive age into account, the level of unmet need for contraception (i.e., the prevalence of fertile women who are sexually active, but are not using any contraceptive method although they do not want children within the next 2 years) is higher in the CEE countries (Klijzing 2000; UNDP 2012). It ranges from 1.7 % in France to about 15–20 % in many CEE countries.

This “East–West divide” in contraceptive prevalence results from divergent historical trends between the two regions (Lesthaeghe 2000; Troitskaia et al. 2009). In WE, the transition toward the dominant use of modern contraception by the majority of the population—also termed the “contraceptive revolution” (Westoff and Ryder 1977)—took place during the 1960s and 1970s (Frejka 2008). The introduction of the hormonal birth-control pill shifted the responsibility for contraception from men to women (Santow 1993; Dalla Zuanna et al. 2005), gave women greater power to control reproductive decisions, and enabled couples to delay parenthood more effectively (Skouby 2004). In most CEE countries, the use of modern contraceptives was legal during the Soviet period (Serbanescu et al. 2004), but access was limited and costs were high because of importation from the West (Westoff 2005). Domestically produced contraceptives were of poor quality (Santow 1993), and healthcare professionals were negative and skeptical about modern methods (Westoff 2005). This led to widespread reliance on traditional contraceptive methods and abortion to control fertility in the former socialist countries (Serbanescu et al. 2004). Abortion as a basic right for all women was legalized well before it was in the WE countries and is therefore well embedded and socially accepted as a method of birth control in case of contraceptive failure (Serbanescu et al. 2004; Frejka 2008). Despite the significant drop in abortion rates and the sharp increase in modern contraceptive use since the 1990s in the CEE countries (Westoff 2005; Frejka 2008), most still have some of the highest estimated abortion rates in the world (Sedgh et al. 2007).

In light of these evolutions, researchers have investigated a range of socioeconomic and demographic determinants of contraceptive use patterns. Most studies have focused on single countries (Cliquet and Lodewijckx 1986; Oddens et al. 1994a, b; Serbanescu et al. 1995; Carlson and Lamb 2001; Moreau et al. 2006) and cross-national comparisons are largely limited to Western (Skouby 2004; Spinelli et al. 2000) or Central and Eastern Europe (Serbanescu et al. 2004; Westoff 2005). Furthermore, population-level characteristics are often ignored, although studies in developing countries have shown the beneficial effects of macroeconomic and proactive efforts of governments to empower women and couples to access modern contraception (Gakidou and Vayena 2007).

In this paper, we examine the micro–macro linkages underlying the diversity between WE and CEE countries with regard to contraceptive use. The persistence, especially in the CEE countries, of not using any contraception or relying on traditional methods—despite the increasing availability of modern contraceptives—seems to result from a complex combination of factors. Among other matters, ingrained prejudices toward modern contraception are still widely present (IPPF 2012). Condoms are stigmatized, as they are considered as a method of preventing sexually transmitted disease, and hormonal contraceptives are perceived as being harmful to health because they are “unnatural.” In this regard, several scholars have criticized the notion of a linear transition from “irrational” traditional methods to “rational” modern ones (Johnson-Hanks 2002; Gribaldo et al. 2009). Because a comprehensive theoretical framework is missing (Mannan and Beaujot 2006), we use Coale’s (1973) Ready, Willing, and Able model—initially developed to interpret the decline in fertility rates during the first demographic transition in Europe—as a starting point. This framework is seen as a useful tool to describe adaptation to new forms of behavior and the subsequent generalization of these behaviors (Lesthaeghe and Vanderhoeft 2001), and its main advantage is its recognition of the joint importance of structural, ideological, and technological conditions (Sobotka 2008). We use the concepts of this Ready, Willing, and Able model to identify and examine the individual determinants of using no or traditional contraceptives, instead of practicing modern methods, across different European contexts. To the best of our knowledge, to date only Mannan and Beaujot (2006) have relied on the model with regard to contraceptive use. Their study focuses on a range of socioeconomic, sociocultural, and demographic predictors of readiness, willingness, and ability and demonstrates a strong association between these last three factors and contraceptive use in Bangladesh. Additionally, we expand the model by paying attention to the (moderating) role of macro-level family policies, normative principles, and gendered economic and political development.

Ready, Willing, and Able

The theoretical framework proposed by Coale (1973) and elaborated by Lesthaeghe and Vanderhoeft (2001) assumes three preconditions for the adoption of new behavior: individual readiness, willingness, and ability. The basic idea is that behavioral change can only occur when all three prerequisites interact simultaneously (Lesthaeghe and Vanderhoeft 2001; Sobotka 2008; Sandström 2012). This weakest link principle entails that the pace of behavioral change is determined by the minimum speed of any one of the preconditions. If one of the factors is resistant to change, it acts as a bottleneck to slow down or prevent transition.

The first factor, readiness, refers to a classic cost–benefit analysis. The utility of new behavior should be evident to the actor, and the advantages must outweigh the disadvantages (Coale 1973; Lesthaeghe and Vanderhoeft 2001). Accordingly, the assumption is raised that the choice of whether or not to have a child should be approached as an individualistic, rational process (Robinson 1997; Balbo et al. 2013). Following this reasoning, people can be considered ready to use contraception if the costs are compensated by the benefits of preventing pregnancy (Robinson 1997). It is evident that this cost–benefit calculation varies across different contraceptive methods. Whereas traditional contraceptives are often less efficient, they also take no preparation and are always available (IPPF 2012). Furthermore, condom use enables men to participate in couples’ contraceptive use, but is also associated with inconvenience, and hormonal methods are most efficient, but at the same time related to side effects such as weight gain or mood swings (Johnson et al. 2013) (economic costs will be discussed in the section about ability).

The concept of readiness has been broadly covered, both theoretically and empirically, by multiple scientific disciplines to explain fertility behavior. Previous studies have in particular investigated the processes underlying child-number and child-timing desires and intentions (Liefbroer 2005; Balbo et al. 2013), and contraceptive use as such has been largely ignored. Nevertheless, it can be argued that the cost of not having children—or controlling fertility—is closely linked with the cost of having children (Robinson 1997). Two types of studies can be distinguished. The first type examines the association between the value of children and fertility behavior. According to economic theories, children should be considered as a special kind of consumption good, of which (future) parents compare the utility and costs with those of other goods (Becker 1960; Easterlin 1975). Hoffman and Hoffman (1973) expanded this purely economic viewpoint by adding children’s value for parents’ well-being—in terms of affection, expansion of the self, social identity, creativity, etc.—to the cost–benefit calculation (Hoffman et al. 1978).

The second type has identified fertility intention as the proximate determinant of predicting fertility decision making and as a mediating factor between people’s perceived costs and rewards of fertility behavior (here, the perceived costs of having children) and their actual behavior (Langdridge et al. 2005; Balbo et al. 2013). Miller (1994) conceptualized the process as a sequence of four stages: motivational traits, desires, intentions, and behaviors. The first step concerns the dispositions to have positive or negative feelings toward, in our case, fertility-related experiences. Results show both a short-term effect and a long-term effect of fertility motivations on the timing of parenthood and desired family size (Miller et al. 2010). Similarly, the theory of reasoned action (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975; Ajzen and Fishbein 1980) and the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen 1991) state that intentions are determined by positive and negative attitudes toward the behavior. Furthermore, attention is paid to “perceived behavioral control” or the perception of being able to perform the behavior. For instance, highly educated women with substantial earning potential seem to postpone childbirth until they consider themselves more established in their jobs (Gustafsson 2005; Van Bavel 2010). Langdridge et al. (2005) and Liefbroer (2005) also confirmed the framework by concluding that financial considerations, career opportunities, relationship quality, etc., all exert an influence, respectively, on the intention and timing of having a first child.

The second factor, willingness, refers to the normative and legitimate acceptability of new forms of behavior (Coale 1973; Lesthaeghe and Vanderhoeft 2001). An actor will rely on fertility control to the extent that it corresponds to established beliefs and codes of conduct, and to the extent that he/she is willing to overcome objections and fears (Mannan and Beaujot 2006). According to Lesthaeghe and van de Kaa (1986), altering fertility behavior—such as the postponement of parenthood or the transition to a subreplacement fertility level—and other demographic changes that took place in Europe during the second half of the twentieth century were grounded in the second demographic transition and the accompanying altering value systems. Research indicates that CEE countries have also been showing symptoms of this transition since the fall of the Iron Curtain (Lesthaeghe and Surkyn 2002), although it is debated whether there is only one model of the transition or multiple ones as normative changes may occur in different periods and at different intensity across contexts (van de Kaa 1997; Sobotka 2008). Across Europe, parenthood almost universally remained positively valued, but it has been increasingly viewed as a source of self-fulfillment rather than as a “duty to society” (Sobotka 2008). The spread of modern contraceptive methods facilitated many of the fertility-related changes and resulted in altering norms regarding fertility regulation, but also in reverse, attitudes with regard to contraceptive use have shifted. Empirical evidence confirms that individuals with more traditional attitudes are generally less likely—or less willing—to use contraceptives, and vice versa (Goldscheider and Mosher 1991; Fehring and Ohlendorf 2007).

Within the conceptualization of men’s and women’s willingness concerning fertility behavior and the focus on changing values, particular attention has been paid to the association between religiosity and fertility (Lesthaeghe and Vanderhoeft 2001; Frejka and Westoff 2008), as religion has long been recognized as a key determinant in predicting household decisions (Adsera 2006). More than most other social institutions, religions impose moral codes to guide behavior, and there is a focus on issues of sexuality or gender-specific roles (McQuillan 2004). Accordingly, previous research indicates that individual religiosity remains, despite the trend toward secularization, an important predictor of fertility behavior (Sobotka and Adigüzel 2003; Adsera 2006). With regard to contraceptive use, the Roman Catholic Church is the only major religion that clearly prohibits contraception as “a sin against nature” (Schenker and Rabenou 1993), apart from traditional methods such as abstinence and the rhythm method, although natural family planning is still preferred (Dalla Zuanna et al. 2005). In the other Christian faiths (such as Eastern Orthodox and Protestantism), a similar reasoning is applied by the more conservative (Srikanthan and Reid 2008). Although the official communist ideology in CEE countries was anti-religious (Sobotka 2008), its traditional views on family and sexuality were in line with this conservative orthodox morality (Ferge 1997). Other religions such as Judaism and Islam retain specific limitations on the use of contraception (Schenker and Rabenou 1993; Srikanthan and Reid 2008).

Only a few studies in developed countries have specifically examined the relationship between religious practice and contraceptive use (Rostosky et al. 2004), most often focusing on the USA or WE countries, and distinguishing between contraceptive nonuse and use, thereby neglecting traditional method use or including it in one of these two categories. Research carried out in the US shows that being religious has a suppressing effect on the use of the oral contraceptive pill, hormonal emergency contraception, and injectables (Fehring and Ohlendorf 2007). According to Kramer et al. (2007), the lower likelihood of using any contraception is only applicable to religious teens. Research in WE points in a similar direction, as non-religious women seem to be most likely to use contraception (Bentley and Kavanagh 2008). In France, adolescents who report regular religious practice less often rely on contraception (Moreau et al. 2013), and in the UK, Christian and Muslim students have the highest prevalence of never using contraceptive methods (Coleman and Testa 2008).

The third factor is ability, which entails that there must be adequate means to implement the new behavior. This dimension of Coale’s (1973) framework refers to the availability and accessibility of the innovation and also relates to the actor’s knowledge about family planning methods (Coale 1973; Lesthaeghe and Vanderhoeft 2001; Mannan and Beaujot 2006). The concept of ability has been addressed by research examining the unmet need for contraceptives (Klijzing 2000; Serbanescu et al. 2004; Sedgh et al. 2007; Singh et al. 2010). As such, those reporting an unmet need for contraception have been identified as not being able to use contraception.

Scholars who have investigated unmet need, and overall the majority of researchers examining contraceptive use, have focused on the link with (especially women’s) socioeconomic status (SES). That is, the association between higher educational attainment and a higher likelihood and consistency of using modern contraception has been repeatedly noted (Spinelli et al. 2000; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and ORC Macro 2003; Serbanescu et al. 2004; Moreau et al. 2006; Mosher and Jones 2010; Janevic et al. 2012). In reverse, withdrawal and periodic abstinence are not likely to be used by the higher educated (Spinelli et al. 2000; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and ORC Macro 2003). The pattern for sterilization is less clear: results regarding male sterilization are inconclusive (Oddens et al. 1994a, b; Anderson et al. 2012; Eeckhaut and Sweeney 2013), whereas the use of female sterilization has been found to be negatively associated with educational level (Oddens et al. 1994a, b; Mosher and Jones 2010; Anderson et al. 2012; Eeckhaut and Sweeney 2013). In developed countries, less attention has been paid to other SES dimensions, such as income or occupational status. A few scholars have demonstrated a positive relationship between household income and the use of modern contraception (Janevic et al. 2012), and a negative association with contraceptive failure (Mosher and Jones 2010). Results concerning work position are inconclusive. Some scholars have concluded that working women are more likely to use oral contraceptives than housewives (Spinelli et al. 2000), whereas others have found no association (Moreau et al. 2006).

In addition to SES, accessibility has been identified as having an urban–rural division, especially in CEE or developing countries. Urbanity is taken as a proxy for supply, because modern contraception may be more readily accessible in urban areas than in rural ones (Klijzing 2000). Research confirms a direct association between living in an urban location and relying on modern contraceptives, whereas traditional methods are more likely to be used in rural areas (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and ORC Macro 2003; Westoff 2005).

To sum up, we expect that individuals who are identified as ready, willing, or able will be more likely to practice modern contraception instead of using no method or traditional contraception. Moreover, following Coale’s (1973) reasoning that the onset and the speed of the European fertility transitions were contingent on the joint meeting of all three preconditions (Lesthaeghe and Vanderhoeft 2001), we expect that each precondition will explain part of individuals’ contraceptive behavior, irrespective of the other preconditions.

Incorporating the Macro-level

Because the vast majority of research about contraceptive use has focused on micro-level characteristics (Clark 2006; Wang 2007), it is implicitly assumed that use is unrelated to the social context (Grady et al. 1993). However, this context seems to be likely to influence men’s and women’s contraceptive options in various ways. Studies concerning contraception in developing countries (Wang and Pillai 2001; Gakidou and Vayena 2007) and studies concerning health outcomes in developed countries (Pickett and Pearl 2001) have repeatedly demonstrated the importance of macro-level variables. Moreover, the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF 2013) recently called for attention to be paid to significant loopholes in policies related to sexual and reproductive health and rights and have highlighted the lack of a comprehensive strategy focusing on fertility control in CEE as well as in WE countries. Our study aims to step into this void by linking the individual-level Ready–Willing–Able framework with these dimensions at the contextual level. In this way, we intend to obtain a more complete understanding of how contraceptive usage is shaped.

Wang and Pillai (2001) identified two types of macro-level sociological studies examining reproductive health. The first emphasizes the importance of reproductive rights (Wang and Pillai 2001; Clark 2006). These specific rights given to parents by the state may reduce the costs of (additional) childbearing by facilitating the reconciliation of paid work and family life (Janta 2014; Mills et al. 2014). Multiple dimensions and actors are involved—think about formal and informal childcare settings, flexibility in the labor market, and parental leave schemes—and especially the combination of these options may create opportunities for (intended) parents. Research confirms that the availability of childcare services and the ability to work part-time serve as predictors for a higher probability of having children (Del Boca 2001). Furthermore, having the opportunity to take parental leave seems to enhance reproductive health (Wang 2004; Clark 2006). The unavailability of these rights forces parents—and in particular mothers—to choose between (full-time) employment and not working at all (Del Boca 2001). Connecting this to Coale’s (1973) model, reproductive rights could be interpreted as an indication of higher levels of readiness at the macro-level.

The second type of study investigates the association with social-structural characteristics. Most studies in this domain have focused on gender equality, as women’s limited access to modern contraceptive methods may be interpreted as a manifestation of inequity in their status (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and ORC Macro 2003) and an inability to negotiate otherwise (Bentley and Kavanagh 2008). Blumberg has argued that women’s relative economic control in particular is the driving force to ensure that they can adjust their fertility pattern to their own interests (Blumberg 1984; Blumberg and Coleman 1989). Accordingly, research shows that less female labor force participation at the district level is related to a lower prevalence of contraceptive use in general (Bentley and Kavanagh 2008). This seems especially true for lower-educated women, as their likelihood of using contraception decreases at a greater rate as compared to that of higher-educated women. Moreover, female political participation is identified as a leverage for women’s reproductive health, because higher participation may accelerate the promotion of laws in favor of female control over contraception and abortion (Clark 2006). We argue that higher levels of gender equality may indicate higher ability at the macro-level.

Additionally, Wang and Pillai (2001) emphasized that social-structural characteristics also have an association with societal and familial values, which influence reproductive decision making to a large extent. Likewise, Neyer and Andersson (2008) highlighted the need to approach family policies within the broader normative context. Religiosity as a group characteristic, for instance, may empower individual religiosity and its influence on contraceptive use, as it conforms to the prevailing norms (Grady et al. 1993; Stark 1996). We suggest that the presence of more modern values may be an indication of higher levels of willingness.

With regard to the micro- and macro-level, it has been suggested that the latter exerts the greatest influence (Blumberg 1984). As different societal levels yield different degrees of power, control at lower levels can be reduced or enhanced by control at higher levels. For instance, the promotion of reproductive rights by the state is contributory to parents’ decision making concerning reproduction (Wang and Pillai 2001). Likewise, female economic power at the household level can be affected in a negative way by the prevailing degree of male domination at the macro-level (Blumberg 1984). In all, we expect that these macro-level notions of readiness, willingness, and ability will be related to a higher likelihood of practicing modern contraception instead of using no method or traditional contraception and, moreover, that they will interact with the conditions at the micro-level by further empowering individuals’ characteristics.

Data and Methods

Data

We use data from the first wave of the Generations and Gender Survey (GGS) (UNECE 2005).2 The GGS is a longitudinal panel survey that collected representative data from people aged between 18 and 79 in Europe and Australia. The aim was to gather detailed information concerning different sociodemographic themes, such as partnership and fertility, over three waves with a 3-year interval between each wave. Face-to-face interviews were conducted, with an average of 10,000 respondents per country per wave. One of the key features of the survey is the cross-national comparability by providing the survey design, a standard questionnaire, and common definitions and instructions in all countries (Vikat et al. 2007). To date, wave 1 data are available for eighteen countries, of which eleven are included in our study: Austria, Belgium, France, Germany,3 Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Georgia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, and the Russian Federation. The diverse periods of data collection across the countries (between 2004 and 2011) should not hinder comparability as the adaptation to new forms of contraceptive behavior and the subsequent generalization of these behaviors take time and depend on multiple factors (Coale 1973; Lesthaeghe and Vanderhoeft 2001). This assumption was empirically confirmed by comparing the contraceptive patterns in waves 1 and 2 of the GGS in the countries for which both waves are available; the prevalence of all methods remains relatively stable. The other countries were omitted from the sample due to missing information on the question about contraceptive use (i.e., Italy, The Netherlands, and Hungary) or other key variables (i.e., Estonia, Norway, and Sweden), or because their geographic location was not accurate for this study (i.e., Australia).

An advantage of the GGS is that it is appropriate for use in research into contextual effects, given that each respondent can be assigned to a NUTS 1 region (Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics). This NUTS classification facilitates the comparability across European regions (Eurostat 2015c). For Georgia and the Russian Federation, there is also information available about the administrative unit of residence for each respondent. We rely on the regional level because of the small number of countries. The number of regions ranges from 1 (Lithuania and the Czech Republic) to 32 (the Russian Federation), and our sample contains a total of 87 regions. Regional data information for the country-specific years of data collection is derived from aggregated data on the total weighted GGS samples, Eurostat, and reports gathering data concerning regional government (see “Appendix” for an overview).

The harmonized GGS dataset for the eleven countries we use contains information about 118,393 respondents. Our analysis focuses on a subsample of 17,492 men and 20,712 women in a heterosexual relationship. Only couples in which the respondent and his/her partner are aged between 18 and 454 are included, and both resident and nonresident partnerships are taken into account. Respondents who never had sexual intercourse (n = 76), who were pregnant or had a pregnant partner (n = 1500), or who were physically unable to have children or had an infertile partner for a reason other than contraceptive sterilization (n = 2832) are removed from the sample. Cases with missing information are also excluded (except for missing values on the income variable; see infra). No variable has more than 5.4 % missing values, and the accumulated percentage of missing values is 11.7 % for men and 10.7 % for women. As the pattern of missing values does not depend on the data values or, in other words, the data are missing completely at random, our estimations are not biased because of this listwise deletion (Acock 2005; Allison 2002; Schafer 1999). The final analytic sample consists of 13,471 men and 15,861 women.

Variables

Dependent Variable

Current contraceptive use is classified into three categories: not using contraception, using traditional contraception (withdrawal, the rhythm method), and using modern contraception (male condom, the pill, intrauterine device, diaphragm, cervical cap, foam, cream, or jelly, suppository, injectable, implant, Persona, hormonal emergency contraception, sterilization). Respondents combining traditional and modern methods are grouped in the latter category, and those reporting the use of “other” methods are excluded (n = 75). Relying on modern contraception is used as the reference category.

Micro-level Variables

Multiple variables are constructed to measure each of the three preconditions. For each variable, a higher score indicates more readiness, willingness, or ability. All metric independent variables are grand-mean-centered.

Readiness is operationalized as respondents’ intentions regarding parenthood and the perceived costs of having a/another child. Fertility intentions are assessed by two questions: “Do you yourself want to have a/another baby now?”5 and “Do you intend to have a/another child during the next 3 years?” In line with the reasoning of the concept of unmet need (Klijzing 2000), we classify couples who intend to delay pregnancy for at least 3 years or who do not want any more children at all, as being ready to use modern contraception (wanting children = 0; not wanting children = 1). With regard to perceived costs, respondents were asked what effects they expected having a/another child within the 3 years after the survey would have on eleven different aspects of their life (i.e., the possibility to do what you want; you/your partner’s employment opportunities; your financial situation; your sexual life; what people around you think of you; the joy and satisfaction you get from life; the closeness between you and your partner; the care and security you may get in old age; certainty in your life; the closeness between you and your parents). The GGS based this question on one of the subjective dimensions from the theory of planned behavior—that is, attitudes toward specific behavior—(see supra) (Vikat et al. 2007), which urged multiple scholars to implement this measure to examine fertility behavior (Dommermuth et al. 2011). Index scores were assessed by calculating respondent’s mean score if they gave an answer to at least five of the items. Respondents with seven or more missing items are removed from the sample. The index ranges from 1 (much better) to 5 (much worse).

For willingness, we relied on respondents’ family values and religious affiliation. A scale consisting of ten items about partnerships and parenthood is used to measure family values. Respondents were asked whether they agree or disagree that: “marriage is an outdated institution,” “it is all right for an unmarried couple to live together even if they have no interest in marriage,” “marriage is a lifetime relationship and should never be ended,” “it is all right for a couple with an unhappy marriage to get a divorce even if they have children,” “a woman/man has to have children in order to be fulfilled,” “a child needs a home with both a father and a mother to grow up happily,” “a women can have a child as a single parent even if she does not want to have a stable relationship with a man,” “when children turn about 18–20 years old they should start to live independently,” and “homosexual couples should have the same rights as heterosexual couples do.” After reversing the contrasting statements, we calculated the respondent’s mean score if an answer was registered for at least half of the items. Respondents with fewer answers are excluded. Answer categories range from 1 (more traditional) to 5 (more modern). The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale is good (α = 0.68). Religiosity is measured by means of three indicators (Diehl et al. 2009). Respondents are coded as “religious” if they display strong religious commitment according to at least two of the three items:6 attending religious services at least once a week, agreeing that religious ceremonies related to life-cycle events such as weddings are important, and mentioning religion as one of the three most important qualities that children should acquire (religious = 0; not religious = 1).

The ability to access contraception is measured by respondents’ educational level, employment status, income level, and place of residence. Respondents’ highest level of education is assessed using the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED97). We differentiate between four categories: studying, low educated, middle educated, and high educated (reference group). Employment status consists of three categories: employed, unemployed, and non-employed. The last group includes students, retired people, homemakers (i.e., performing housework or caring for children or others), those unable to work due to illness or disability, and those who are in military or social service. The employed are taken as the reference category. For the income position of respondents, we make a distinction between people living in relative poverty compared with the country- and gender-specific median (≤50 % of the gender-specific median income), people with a low income (51–80 %), people with a median income (81–120 %; reference group), and people with a relatively high income (>120 %). To account for the item non-responses (for men 10.1 %; for women 9.0 %), the data were completed using multiple imputation techniques. Five different datasets were generated, and the formulas provided by Rubin (1996) were applied to calculate the final estimates. Finally, degree of urbanization is coded as a dummy variable, distinguishing between respondents living in rural areas (=0) and respondents living in urban areas (=1).

Macro-level Variables

All contextual variables are measured at the regional level and grand-mean-centered. The prevalence of female part-time work is used as an indicator for reproductive rights (Del Boca 2001; Mills et al. 2014) or, using Coale’s (1973) terminology, the level of readiness at the population level. It is calculated as a percentage of the total female employment rate (Eurostat 2015a). Although a specific proportion of these women may be involuntary engaged in part-time work (Sandor 2011; Janta 2014), calculations at the country level indicate that the subtraction of the percentage of involuntary part-time workers (Eurostat 2015b; OECD 2015) from the total number does not substantially alter the observed pattern for the prevalence of part-time work across the countries [except for Georgia as its labor market is characterized by widespread involuntary part-time work (EU, GEPLAC, and Georgian Economic Trends 2004)]. A higher prevalence of female part-time work is seen as an indicator for higher levels of readiness.

The percentage of religious individuals is used to operationalize the normative context. We relied on the total weighted GGS samples of each country to calculate the aggregate number of respondents in each NUTS region who display strong religious commitment (supra). A lower prevalence of religious people serves as an indicator of higher willingness.

Finally, the level of gender equality is measured as the ratio of female to male median income in each region (multiplied by 100) and the percentage of women in regional politics. Most country-level gender equality measurements, such as the Gender Inequality Index, the Gender Empowerment Measure, the Gender Equality Index, or the Gender Gap Index, use (among other items) both dimensions, and these indicators of female empowerment are relied on in empirical research (Bentley and Kavanagh 2008; Van de Velde et al. 2013). Although it should be acknowledged that the mandates and responsibilities of regional politicians differ across countries (Sundström and Wängnerud 2013), it gives a good indication of the political gender culture in each region. A higher income ratio and a higher percentage of women in parliament indicate higher ability.

Control Variables

We control for gender (0 = man; 1 = woman), age, and age squared, to account for nonlinear effects. We also control for partner status: respondents may either be married, be cohabiting, or have a nonresident partner. Being married is used as the reference group. The number of children is measured as a categorical variable: no children (reference group), one child, two children, and three or more children. Biological, adopted, step and foster children of the respondent are included.

Analysis

We use multinomial multilevel models with three levels: (1) men (n = 13,471) and women (n = 15,861) are nested in (2) regions (n = 87) which are nested in (3) countries (n = 11). This statistical technique takes into account that individuals who are living in the same region tend to be more similar than individuals from different regions (Hox 2010). Accordingly, the country level controls for the clustering of the regions. Because of the limited number of countries, no country-level variables are included in the models and the variance components are not interpreted as these are likely to be biased (Stegmueller 2013). For men, individual cases per region vary from 7 to 1269 and per country from 769 to 1691; for women, regions have a range from 9 to 1494 cases and countries from 824 to 2356. Although this indicates that some regions only contain a small number of respondents, simulations demonstrate that valid and reliable estimations can be made starting with an average of five cases per group (Clarke 2008).

First of all, the descriptive statistics are discussed briefly and, by calculating the z-scores, we determine whether the percentage difference in the prevalence of no, traditional, and modern contraception in WE and CEE is significant. Then, our three hypotheses are tested. First, we examine the Ready–Willing–Able formulation at the individual level for men and women separately. As the odds ratios for the independent main effects do not change substantially when all individual variables are simultaneously included in the model (compared with estimating the variables for each precondition separately), only this complete model is presented. Next, we add the macro-level measurements and, finally, the cross-level interactions between individual readiness, willingness, and ability, and regional readiness, willingness, and ability. Although the construction of one index per individual precondition would simplify this procedure, the necessary cutoff points would entail significant limitations. The interaction terms enable us to examine whether the associations at the individual level between being ready, willing, or able and using modern contraception are moderated by the preconditions at the contextual level. To enhance interpretability, each interaction term is included separately and only the models with significant interactions are presented and discussed.

All models were analyzed using the software program MLwiN (version 2.33), estimating via second-order PQL. Because odds ratios reflect a certain degree of unobserved heterogeneity, caution is necessary when they are compared (Mood 2010). In line with Mood (2010), our coefficients are y-standardized to enhance the comparability across different models.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

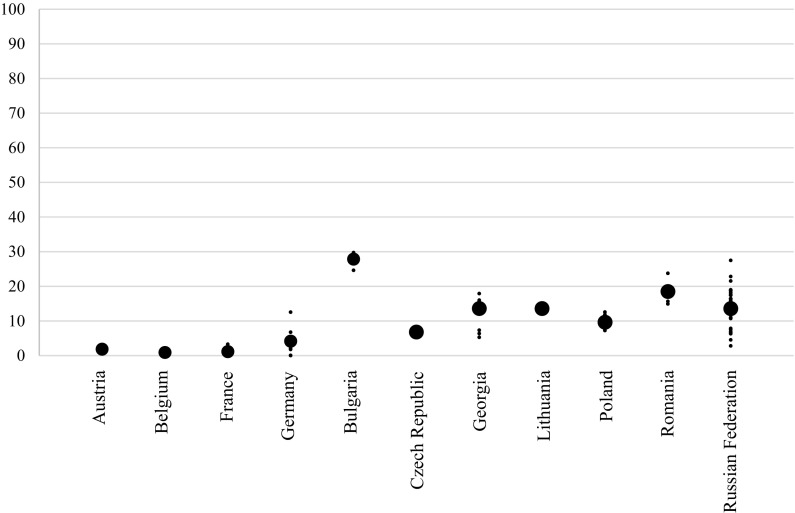

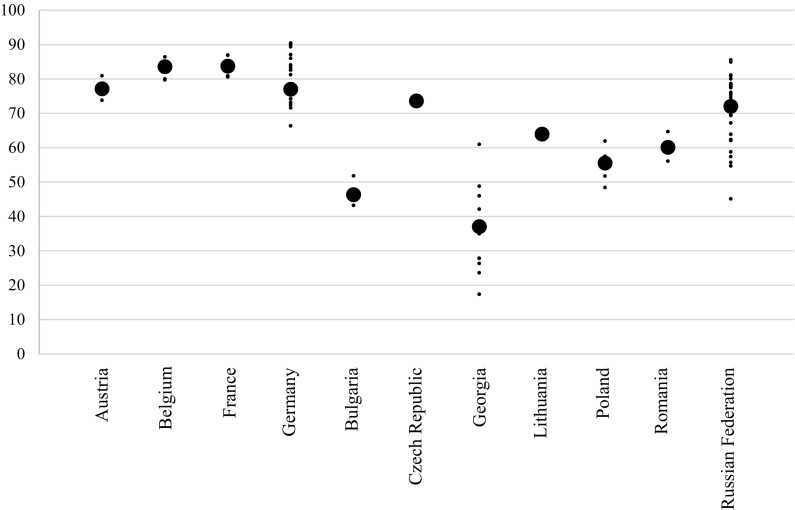

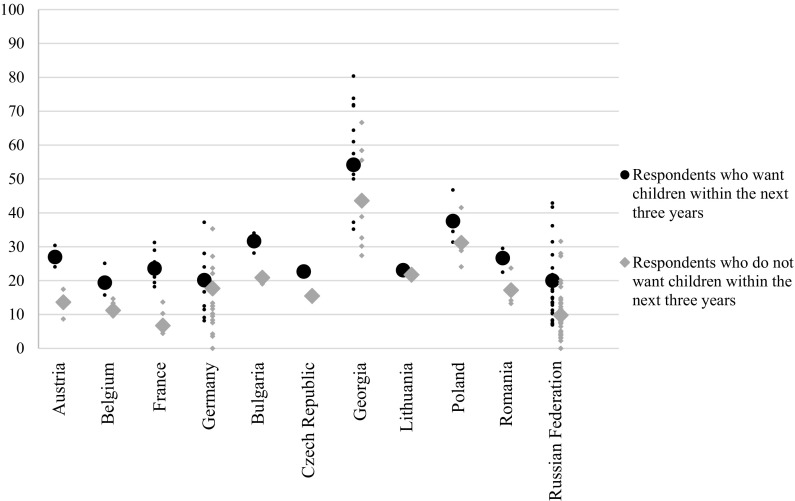

Table 1 presents the percentages and percentage differences in contraceptive use in WE and CEE. We differentiate between the respondents with and without fertility intentions in the near future because nonuse in the first subsample is more likely to be due to the desire to have children, whereas in the second, it is more likely to display patterns of unmet need. For both groups, the table confirms that the East–West divide remains relevant to this day. Significant gaps in contraceptive behavior are found for traditional and modern methods, as well as for nonuse. Percentage differences range from 7.1 % (for those with childbearing intentions) or 9.8 % (for those without intentions) for nonuse to 17.6 % (for those with childbearing intentions) or 26.7 % (for those without intentions) for modern contraceptives. At the same time, the figures highlight the heterogeneity that consists in both regions (Figs. 1, 2, 3). Whereas the prevalence of traditional contraceptives is generally higher in all CEE countries and it is practically zero in the WE countries, the patterns for modern contraception and nonuse are less straightforward. More WE respondents use modern contraceptives, but the prevalence in Austria and Germany is close to that in the Czech Republic and the Russian Federation. For nonuse, the Russian Federation reports the lowest percentage among those who want children within the next 3 years, followed by the WE countries Germany and Belgium. A similar pattern is found for those with no fertility intentions: the Russian Federation, Belgium, and France display the lowest prevalence. It is striking that Bulgaria and Georgia overall show the lowest prevalence of reliance on modern methods. This is mainly due to the high percentages of traditional use in the first, and the high prevalence of nonuse in the second. Interestingly, for Georgia, this finding seems to go hand in hand with the observation that this country also has the lowest perceived cost of children, the most traditional family values, the second highest prevalence of religious respondents, and the lowest percentage of students and employed men and women, the most respondents with a low income, and the second highest prevalence of men and women living in a rural area (Table 2). Moreover, the country has one of the highest percentages of religious people and the greatest income differentials between men and women.

Table 1.

Percentages and percentage differences in contraceptive use by fertility intention and European region

| WE | CEE | Difference | Sign.a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondents who want children within the next 3 years (N = 15,356) | ||||

| No contraception | 23.2 | 30.3 | 7.1 | *** |

| Traditional contraception | 2.2 | 12.7 | 10.6 | *** |

| Modern contraception | 74.6 | 57.0 | 17.6 | *** |

| Respondents who do not want children within the next 3 years (N = 13,976) | ||||

| No contraception | 12.5 | 22.3 | 9.8 | *** |

| Traditional contraception | 2.1 | 19.0 | 16.9 | *** |

| Modern contraception | 85.4 | 58.7 | 26.7 | *** |

az-score calculated by dividing the percentage difference by the standard error of the percentage difference

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of using traditional contraception, per country and region (n = 29,332)

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of using modern contraception, per country and region (n = 29,332)

Fig. 3.

Prevalence of using no contraception by fertility intention, per country and region (n wanting children = 15,356; n not wanting children = 13,976)

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics: means (SD), and percentages (n = 29,332)

| Austria | Belgium | France | Germany | Bulgaria | Czech Republic | Georgia | Lithuania | Poland | Romania | Russian Federation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 2826 | 1593 | 2383 | 2248 | 3976 | 2244 | 2076 | 2383 | 3712 | 3170 | 2721 |

| Individual variables | |||||||||||

| Readiness | |||||||||||

| Wanting children | |||||||||||

| Yes | 55.3 | 52.4 | 47.5 | 45.7 | 45.9 | 58.2 | 54.5 | 61.4 | 57.7 | 44.7 | 55.7 |

| No | 44.7 | 47.6 | 52.5 | 54.3 | 54.1 | 41.8 | 45.5 | 38.6 | 42.3 | 55.3 | 44.3 |

| Perceived cost of children | 3.14 (0.31) | 3.08 (0.40) | 3.04 (0.51) | 3.17 (0.35) | 3.09 (0.51) | 3.12 (0.44) | 2.87 (0.44) | 3.02 (0.42) | 3.16 (0.38) | 3.04 (0.44) | 3.02 (0.45) |

| Willingness | |||||||||||

| Family values | 3.12 (0.54) | 3.34 (0.55) | 2.87 (0.59) | 3.10 (0.56) | 2.97 (0.42) | 2.92 (0.43) | 2.26 (0.38) | 2.84 (0.40) | 2.82 (0.45) | 2.49 (0.43) | 2.74 (0.39) |

| Religious | |||||||||||

| Yes | 7.8 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 8.0 | 5.1 | 3.9 | 29.6 | 6.2 | 32.2 | 23.2 | 2.2 |

| No | 92.2 | 98.0 | 98.1 | 92.0 | 94.9 | 96.1 | 70.4 | 93.8 | 67.8 | 76.8 | 97.8 |

| Ability | |||||||||||

| Educational level | |||||||||||

| Studying | 7.2 | 8.5 | 8.6 | 8.4 | 3.2 | 10.1 | 1.7 | 7.1 | 3.0 | 2.4 | 3.4 |

| Low | 9.1 | 15.8 | 12.9 | 10.1 | 19.6 | 9.5 | 7.1 | 8.1 | 5.2 | 21.8 | 5.9 |

| Middle | 66.0 | 32.5 | 44.6 | 57.5 | 54.4 | 65.0 | 60.8 | 57.1 | 60.6 | 63.1 | 50.1 |

| High | 17.8 | 43.3 | 33.9 | 23.9 | 22.8 | 15.4 | 30.3 | 27.7 | 31.2 | 12.7 | 40.6 |

| Employment status | |||||||||||

| Employed | 76.1 | 80.4 | 75.2 | 65.0 | 65.8 | 69.5 | 49.9 | 78.8 | 70.9 | 77.8 | 74.4 |

| Unemployed | 3.3 | 5.6 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 21.7 | 5.3 | 18.1 | 4.8 | 9.7 | 5.0 | 6.8 |

| Non-employed | 20.6 | 14.0 | 16.5 | 26.6 | 12.4 | 25.2 | 32.0 | 16.4 | 19.4 | 17.2 | 18.8 |

| Income level | |||||||||||

| ≤50 % of median income | 16.9 | 14.6 | 18.5 | 24.9 | 21.5 | 19.9 | 28.1 | 15.1 | 21.9 | 17.2 | 27.5 |

| 51–80 % of median income | 18.3 | 12.1 | 15.2 | 16.2 | 9.0 | 13.3 | 6.0 | 8.3 | 7.5 | 7.3 | 9.2 |

| 81–120 % of median income | 30.6 | 37.9 | 29.0 | 24.1 | 18.9 | 25.9 | 8.1 | 15.0 | 17.2 | 17.1 | 13.7 |

| >120 % of median income | 34.2 | 35.4 | 37.3 | 34.7 | 50.6 | 40.8 | 57.8 | 61.6 | 53.5 | 58.4 | 49.6 |

| Place of residence | |||||||||||

| Rural | 41.5 | 60.4 | 16.7 | 22.4 | 28.2 | 33.0 | 44.9 | 27.7 | 33.3 | 41.6 | 25.4 |

| Urban | 58.5 | 39.6 | 83.3 | 77.6 | 71.8 | 67.0 | 55.1 | 72.3 | 66.7 | 58.4 | 74.6 |

| Context variables | |||||||||||

| % Female part-time work | 41.70 (3.01) | 40.71 (3.53) | 30.76 (4.26) | 43.71 (6.75) | 3.43 (0.63) | 8.50 (0.00) | 31.37 (9.79) | 12.60 (0.00) | 11.64 (1.64) | 10.26 (3.76) | 4.97 (2.95) |

| % Religious | 7.92 (1.16) | 2.87 (1.75) | 4.91 (1.16) | 10.01 (4.33) | 6.69 (1.44) | 6.20 (0.00) | 27.24 (5.15) | 14.80 (0.00) | 40.79 (6.89) | 32.99 (4.80) | 3.17 (1.75) |

| Ratio of female to male income | 63.75 (6.03) | 75.5 (2.83) | 71.35 (4.68) | 53.26 (8.36) | 77.00 (0.00) | 60.00 (0.00) | 45.36 (8.73) | 73.00 (0.00) | 65.82 (3.87) | 84.21 (3.77) | 62.50 (31.91) |

| % Women in regional politics | 30.76 (4.70) | 28.66 (5.97) | 47.62 (0.95) | 29.54 (4.20) | 9.11 (6.88) | 17.00 (0.00) | 11.25 (2.07) | 22.00 (0.00) | 23.15 (7.22) | 12.78 (1.70) | 7.89 (5.76) |

More in general, Table 2 suggests that respondents in the WE countries display higher levels of readiness, willingness, and ability to use modern contraceptives than those in the CEE countries. With a few exceptions, we find that WE respondents report a higher perceived cost of having (additional) children and that they hold on to more modern family values. Furthermore, a higher percentage of students can be observed in WE. The CEE countries have lower percentages of part-time employment (except for Georgia, which can be attributed to the high prevalence of involuntary part-time work) and relatively less women in regional politics, and many of the countries display relatively high levels of religiosity. By contrast, for income status, lower percentages of CEE respondents have an average income and higher percentages have a high income compared with those in the WE countries.

Ready, Willing, and Able to Use Modern Contraception: Multilevel Analysis

First, we look at the variance partition coefficient (VPC) to determine the total variance in contraceptive use at the regional level. The null model shows that 3.1 % of men’s and 3.6 % of women’s traditional contraceptive use is influenced by the region in which they live (results not shown). The variance in using no contraception is higher: 6.2 % of men’s and 4.2 % of women’s nonuse is determined by the regional level.

Individual-Level Determinants

In response to the literature showing the importance of taking both men and women into account when studying contraceptive use (Thomson 1997; Grady et al. 2010; Balbo et al. 2013), we start with a gender-specific model to identify the relationship between the individual-level characteristics and contraceptive use (Table 3). Overall, the results demonstrate that higher levels of readiness, willingness, and ability at the individual level play an important role in predicting respondents’ modern contraceptive use. It is confirmed that those with no desire for children and those who assign higher costs to having a/another child are less likely not to use contraception than to use modern contraception. Furthermore, men and women with more modern family values or who are identified as unreligious, the higher educated and the employed, and those living in urban areas are more likely to use modern contraception rather than nothing or traditional methods. Only for women, being a student or being employed rather than non-employed are also related to a higher likelihood of using modern methods. Interestingly, no association between respondents’ readiness and traditional method use is found, except for women with no childbearing desire who are more likely to use modern instead of traditional methods. Also the relationship between income and contraception could not be established, except for men with a high income who are significantly less likely not to use contraceptives.

Table 3.

Relationship between readiness, willingness, and ability at individual level, and contraceptive use for men (n = 13,471) and women (n = 15,861)

| No contraceptiona | Traditional contraceptiona | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |||||

| OR | OR | OR | OR | |||||

| Intercept | 0.857 | 0.747 | ** | 0.298 | *** | 0.345 | *** | |

| Readiness | ||||||||

| Not wanting children (ref. wanting) | 0.703 | *** | 0.777 | *** | 0.942 | 0.916 | * | |

| Perceived cost of children | 0.768 | *** | 0.732 | *** | 1.018 | 1.003 | ||

| Willingness | ||||||||

| Family values | 0.871 | *** | 0.885 | *** | 0.784 | *** | 0.851 | *** |

| Not religious (ref. religious) | 0.870 | *** | 0.870 | *** | 0.885 | * | 0.873 | *** |

| Ability | ||||||||

| Educational level (ref. high) | ||||||||

| Studying | 0.810 | 0.674 | *** | 0.942 | 0.642 | *** | ||

| Low | 1.579 | *** | 1.745 | *** | 1.467 | *** | 1.356 | *** |

| Middle | 1.152 | *** | 1.210 | *** | 1.161 | ** | 1.051 | |

| Employment status (ref. employed) | ||||||||

| Unemployed | 1.149 | *** | 1.135 | *** | 1.126 | * | 1.199 | *** |

| Non-employed | 1.112 | 1.164 | *** | 1.099 | 1.119 | ** | ||

| Income level (ref. 81–120 %) | ||||||||

| ≤50 % of median income | 1.062 | 1.002 | 1.031 | 0.953 | ||||

| 51–80 % of median income | 1.040 | 0.990 | 1.017 | 0.954 | ||||

| >120 % of median income | 0.922 | ** | 0.958 | 0.991 | 0.992 | |||

| Urban residence (ref. rural) | 0.892 | *** | 0.888 | *** | 0.874 | *** | 0.876 | *** |

| Variance | ||||||||

| Region | 0.209 | 0.051 | 0.145 | 0.037 | 0.121 | 0.047 | 0.137 | 0.044 |

| VPCb | 0.060 | 0.042 | 0.035 | 0.040 | ||||

*** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05

aControlled for age, age squared, number of children, and marital status

bVariance at regional level = (σ 2 region )/(σ 2 region + π 2/3)

Macro-level Determinants and Cross-level Interactions

As we largely find similar associations for men and women, further analyses are performed on the total sample while controlling for gender. A positive link is established between the levels of willingness and ability at the regional level, and modern contraceptive method choice (Table 4). With regard to the first dimension, a higher prevalence of religious people in a region (OR = 1.011) is related to a higher likelihood of not using contraception instead of using modern methods. The predicted probabilities indicate that—holding all other variables constant—men and women who are living in the region with the highest prevalence of religiousness (i.e., Wschodni, Poland; % religious = 50.50; π = 7.9 %) are twice as likely to report nonuse over use as compared to those living in the region with the lowest prevalence (i.e., Brandenburg, Germany; % religious = 0.30; π = 4.0 %). The second dimension shows that regions with higher levels of gender equality overall seem to be characterized by a higher likelihood of using modern methods. A higher income ratio (indicating smaller gender-specific income differentials, as women on average earn less than their male counterparts in almost all investigated regions) and higher percentages of women in regional politics are associated with a lower likelihood of not using contraception (ORratio female/male income = 0.991; OR%women in regional politics = 0.992) or relying on traditional contraception (ORratio female/male income = 0.993; OR%women in regional politics = 0.983). Accordingly, significant gaps in the patterns of contraceptive behavior can be identified between the regions with the lowest and highest levels of gender equality. Whereas the differences in probabilities are only 2 % for nonuse, they range from 6.0 % (income ratio) to 13.0 % (political participation) for traditional methods, and from 7.6 % (income ratio) to 14.7 % (political participation) for modern contraceptives.

Table 4.

Macro-level measurements and contraceptive use on the total sample (n = 29,332)

| No contraceptiona | Traditional contraceptiona | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | OR | |||

| Intercept | 0.773 | *** | 0.290 | *** |

| % Female part-time work | 1.002 | 0.992 | ||

| % Religious | 1.011 | ** | 1.010 | |

| Ratio of female to male income | 0.991 | ** | 0.993 | ** |

| % Women in regional politics | 0.992 | * | 0.983 | ** |

| Variance | ||||

| Region | 0.150 | 0.033 | 0.158 | 0.041 |

| VPCb | 0.044 | 0.046 | ||

*** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05

aControlled for gender, age, age squared, number of children, marital status, wanting children, perceived cost of children, family values, religiosity, educational level, employment status, income level, and residence

bVariance at regional level = (σ 2 region)/(σ 2 region + π 2/3)

In the final part of our analysis, we investigate whether the associations between readiness, willingness, and ability to use modern contraceptives at the individual level are moderated by these indicators at the contextual level (Table 5). With regard to readiness, the results confirm our expectations by showing that higher percentages of female part-time employment strengthen the relationship between not wanting a/another child (ORnone = 0.996; ORtraditional = 0.997) or assigning higher costs to it (ORnone = 0.995; ORtraditional = 0.995), and the lower likelihood of relying on no or traditional methods instead of using modern contraception. This suggests that respondents living in regions in which part-time employment is promoted are more likely to be able to translate their readiness to use modern contraception into effective use.

Table 5.

Cross-level interactions on the total sample (n = 29,332), separately included in the model

| No contraception | Traditional contraception | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Models 1–5ab | Models 1–5ab | ||||

| OR | OR | ||||

| 1 | Readiness | ||||

| Not wanting children | 0.742 | *** | 0.907 | *** | |

| Part-time | 1.004 | 0.994 | |||

| Not wanting children × part-time | 0.996 | *** | 0.997 | * | |

| 2 | Perceived cost of children | 0.737 | *** | 0.968 | |

| Part-time | 1.002 | 0.990 | * | ||

| Perceived cost of children × part-time | 0.995 | *** | 0.995 | * | |

| 3 | Ability | ||||

| Educational level | |||||

| Studying | 0.725 | *** | 0.744 | *** | |

| Low | 1.629 | *** | 1.387 | ** | |

| Middle | 1.180 | *** | 1.093 | *** | |

| Ratio income | 0.991 | *** | 0.990 | ** | |

| Educational level × ratio income | |||||

| Studying | 0.996 | 0.990 | |||

| Low | 1.006 | * | 1.004 | ||

| Middle | 1.001 | 1.004 | * | ||

| 4 | Educational level | ||||

| Studying | 0.736 | *** | 0.768 | ** | |

| Low | 1.646 | *** | 1.316 | *** | |

| Middle | 1.181 | *** | 1.050 | ||

| Women in politics | 0.995 | 0.987 | * | ||

| Educational level × women in politics | |||||

| Studying | 0.998 | 1.011 | |||

| Low | 0.990 | *** | 0.990 | ** | |

| Middle | 0.998 | 0.993 | ** | ||

| 5 | Urban residence | 0.891 | *** | 0.901 | *** |

| Women in politics | 0.989 | ** | 0.972 | *** | |

| Urban residence × women in politics | 1.005 | ** | 1.007 | ** | |

*** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05

aControlled for gender, age, age squared, number of children, marital status, wanting children, perceived cost of children, family values, religiosity, educational level, employment status, income level, residence, % part-time workers, % religious, ratio of female to male income, and % women in regional politics

bEach interaction term is included separately; five different models are displayed. Each model contains the same micro- and macro-level variables, only the interaction term differs

With regard to the normative context, the associations between family values or religiosity and contraceptive use do not vary according to the percentage of religious people living in a region.

Interestingly, the interactions with both gender equality measurements indicate opposing effects, as the relationship between individual ability and using modern contraception is generally weakened in regions with a lower income ratio and strengthened in regions with lower percentages of women in politics. This partly confirms our expectation of empowering macro-ability. First, we find that the difference in the likelihood of using nothing instead of modern contraception between the lower and higher educated shrinks in regions characterized by a lower income ratio (OR = 1.006). Likewise, the difference between the middle and higher educated in relying on traditional contraception becomes smaller in these regions (OR = 1.004). Second, the results show that the difference in the likelihood of using nothing or traditional methods, instead of using modern contraception, between the lower (ORnone = 0.990; ORtraditional = 0.990) or middle educated (ORtraditional = 0.993) and the higher educated becomes larger in regions with lower prevalence of women in politics. The difference in relying on no or traditional contraception between respondents living in an urban area or in a rural area enlarges (ORnone = 1.005; ORtraditional = 1.007) in these regions.

Discussion and Conclusion

A long tradition of research has focused on contraceptive choice, thereby holding men and—especially—women responsible for their “uncommitted” and “uninformed” choice if they opt for “irrational,” ineffective methods (Fisher 2000; Johnson-Hanks 2002; Gribaldo et al. 2009). In line with scholars who have problematized this assumption, we used Coale’s (1973) Ready–Willing–Able framework to examine the complex intertwinements between structural, ideological, and technological conditions that impact contraceptive behavior. First, we tested whether individuals who are ready, willing, or able are more likely to practice modern methods. Second, attention was paid to the (moderating) influence of contextual effects regarding reproductive rights, normative context, and gender equality.

We observed significant associations between each of the three preconditions, and using no or traditional contraceptives, while controlling for the other two. Evidence was found that both men’s and women’s characteristics matter, which confirms the relevance of taking men into account when studying reproductive behavior (Thomson 1997; Grady et al. 2010; Balbo et al. 2013). Overall, individuals holding more modern family values and displaying low religious commitment are more likely to rely on modern methods, instead of using no contraception or traditional methods. The same seems to be true for the higher educated (rather than the lower or middle educated), the female students (rather than the higher educated), the employed (rather than the unemployed or, only for women, the non-employed), and those living in an urban area (rather than in a rural area). Interestingly, no association could be established between individual’s readiness and the use of traditional methods, as men’s fertility intentions, and men’s and women’s perceived cost of children seemed not significantly related to contraceptive method use. This suggests that the decision of using traditional contraceptives over modern ones, or vice versa, is not resulting from a rational calculation between the costs and benefits of having children. Therefore, it explicitly questions the assumption that a linear transition from “irrational” traditional to “rational” modern methods is to be expected. Scholars suggest that social and cultural expectations in particular, as well as access and availability, may be the leading factors in behavioral change concerning traditional contraceptive use. Organizations such as the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF 2012, 2013) primarily emphasize the importance of, on the one hand, increasing public awareness of reproductive health, altering social norms, and enhancing the knowledge of service providers while, on the other hand, making contraceptives more affordable and accessible. This concerns both WE and CEE countries.

Keeping in mind the heterogeneity across and within WE and CEE with regard to all individual-level factors under investigation, it would be too simplistic to argue that the East–West divide in contraceptive use can be merely explained by differentials in terms of individual readiness, willingness, or ability. Despite a few exceptions, no clear “East–West” distinction can be made, but some country-specific findings are worth noting. Georgia and Bulgaria show the highest prevalence of nonuse and traditional method use, respectively, and as a consequence also the lowest percentages of modern method use. This is in line with previous comparative studies (Klijzing 2000; Carlson and Lamb 2001; Serbanescu and Seither 2003; Serbanescu et al. 2005; Janevic et al. 2012). It is striking that for Georgia, this high level of nonuse coincides with the observation that the country displays the lowest levels of individual readiness, willingness, and ability. Moreover, the country documents the highest abortion rates in the region (RHS 2015). Bulgaria, on the other hand, scores averagely on most indicators. This further strengthens the argument that traditional contraceptives should not be perceived as an uninformed choice.

The first set of results is thus only part of the story. Contraceptive practice is embedded in contexts with specific characteristics and, as such, regional-level dimensions of readiness, willingness, and ability seem to also relate to contraceptive usage, and to interact with the relation between individual determinants and contraceptive use. First, individuals are encouraged to use modern contraception in accordance with their childbearing desires in regions with a higher prevalence of female part-time employment. As part-time work is markedly lower in the CEE region, it can be argued that more attention for family policies may encourage modern contraceptive use in these countries. Second, respondents from regions with more religiously committed residents are more likely not to use contraception instead of using modern methods, irrespective of their own religious belief or practice. Third, individuals living in regions with lower levels of gender equality are more likely to opt for not using any contraception or practicing traditional contraception rather than relying on modern methods. This adds to the few studies about this topic in developed countries (Clark 2006; Bentley and Kavanagh 2008). Particularly interesting is the observation that both gender equality indicators interact in opposing ways with the relationship between individual ability and contraceptive use, which underscores the importance of approaching gender equality as a multidimensional construct. On the one hand, the discrepancy between the lower or middle educated and the higher educated seems to be smaller in regions with lower female-to-male income ratios. This should be interpreted in light of the encouragement of dual-breadwinner households during the Soviet period before the 1990s, where women showed much higher rates of employment in CEE than in the West (Ferrera 1996; Pascall and Manning 2000). Despite the dramatic fall in GDP, increase in poverty and income inequality after the collapse of the socialist system, female employment rates nowadays remain similar in WE and CEE. This suggests that this indicator cannot be put forward as evidence for the East–West divide in contraceptive use patterns. On the other hand, the advantage of being higher educated and living in an urban area increases in regions with lower prevalence of female politicians. As for macro-readiness, it seems that especially the CEE countries could benefit from higher levels of female political participation. Further research is needed in order to disentangle the differing effects of distinct dimensions of macro-level gender equality.

Before turning to the conclusion, it is important to note that models such as Coale’s (1973) have been subject to criticism because of the over-simplification of fertility-related decisions, intentions, and transitions and therefore have been identified as limiting and potentially misleading (Santow and Bracher 1999; Fisher 2000). Nevertheless, scholars do recognize the value of this type of framework to order concepts and we are convinced that the implementation of the Ready–Willing–Able argument serves here as a fruitful framework to integrate socioeconomic, cultural, and technological factors into our analysis of contraceptive use.

Several other limitations should be acknowledged. First, reproductive rights are measured as the percentage of female part-time employment, whereas it entails much more complexity (Janta 2014; Mills et al. 2014). Because of this, we checked the validity of our measure by performing the analysis with two alternative measures—the percentage of households with at least one child below the age of three that uses full-time formal childcare, and the percentage of mothers in parental leave—and similar results were obtained. Second, we approach contraception from an individual’s perspective, whereas it often results from a decision and negotiation process between partners (e.g., Manning et al. 2009; Kusunoki and Upchurch 2011; Bauer and Kneip 2013). We attempted to expand on studies that emphasize the importance of men’s preferences and parenthood desires (Thomson 1997; Grady et al. 2010; Balbo et al. 2013) by taking both men’s and women’s characteristics into account. In this way, we extend previous research that merely focuses on the female population. Finally, the GGS only provides information on the key variables for eleven WE and CEE countries. Obtaining greater insight into the differing contraceptive use patterns across other European regions would be interesting as, for instance, use of the withdrawal method still persists in Southern European countries such as Italy, despite the introduction of more efficient methods (Santow 1993; Dalla Zuanna et al. 2005; Gribaldo et al. 2009). Related is the limited number of countries in our analyses. This urged us to rely on the regional level for the macro-level measures, although the variance at this contextual level was relatively small.

In conclusion, on the one hand, our study demonstrates that the East–West divide remains relevant to this day as clear variance in contraceptive behavior can be noted. WE men and women generally report higher perceived costs of additional children and more modern family values, and WE regions are characterized by a higher prevalence of part-time employment and female political participation, and a lower prevalence of religiousness, which all are associated with higher levels of practicing modern contraception. At the same time, this rigid division between East and West tends to ignore the regional variation across European countries (Troitskaia et al. 2009). At the least, our results underline that future research would benefit from paying attention to a complex set of individual as well as contextual incentives and barriers that may play a role in opting for certain contraceptive methods.

Appendix

Sources from which the regional data information was taken

| Variable | Country | Source |

|---|---|---|

| % Part-time workers | Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Lithuania, Poland, Romania | Eurostat |

| Georgia, the Russian Federation | Aggregated data GGS, total weighted samples | |

| % Religious | All countries | Aggregated data GGS, total weighted samples |

| Ratio of female to male income | All countries | Aggregated data GGS, total weighted samples |

| % Women in regional politics | Austria | Bundeskanzleramt Österreich, Bundesministerin für Frauen und Öffentlichen Dienst. 2010. Frauenbericht 2010. Bericht betreffend die Situation von Frauen in Österreich im Zeitraum von 1998 bis 2008. Wien: Bundeskanzleramt Österreich |

| Belgium | Instituut voor de Gelijkheid van Mannen en Vrouwen. 2006. De deelname van mannen en vrouwen aan de Belgische politiek. Brussel: Instituut voor de Gelijkheid van Mannen en Vrouwen | |

| France | Website Ministère de l’Intérieur | |

| Germany | Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend. 2005. Gender-Datenreport. Datenreport zur Gleichstellung von Frauen und Männern in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. München: Waltraud Corneliβen | |

| Bulgaria | Sofia News Agency | |

| The Czech Republic | Database Inter-Parliamentary Union | |

| Georgia | Women’s Political Resource Centre. 2006. Local government elections of 2006. Tbilisi: WPRC | |

| Lithuania | Database Inter-Parliamentary Union | |

| Poland | The Institute of Public Affairs. 2011. Kandydatki w wyborach samorzadowych w 2010. Warsaw: The Institute of Public Affairs | |

| Romania | Macarie, Felicia Cornelia, Neamtu, Bogdana, and Creta, Simona Claudia. 2011. “Male dominated political parties in Romania. A model of organizational culture,” Managerial Challenges of the Contemporary Society 2 | |

| The Russian Federation | United Nations Development Programme. 2007. National Human Development Report Russian Federation 2006/2007. Russia’s regions: Goals, challenges, achievements. Moscow: UNDP |

Footnotes

Although the division between traditional and modern contraceptive methods is historically inaccurate, this terminology is widely used in research concerning fertility regulation (Frejka 2008). Withdrawal and the rhythm method are usually classified as “traditional”, whereas barrier methods, hormonal contraception, and sterilization are considered as “modern”.

As a test for the validity of the data, the contraceptive use patterns derived from the GGS were compared to those derived from the Family and Fertility Surveys (FFS) (UNECE 2000)—for Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Lithuania and Poland—and the Reproductive Health Surveys (RHS 2015)—for Czech Republic, Georgia, Romania and Russian Federation–by calculating Pearson’s correlation. For the GGS, the percentage of unmet need is calculated on a subsample (n = 25,005) excluding respondents that are not using contraception and have a childbearing desire, whereas the percentage of traditional and modern contraceptives is calculated on the total sample (n = 29,332). For both unmet need and modern methods, the correlations are strong (r GGS-FFS/unmet need = 0.95; r GGS-FFS/modern = 0.83; r GGS-RHS/unmet need = 0.69; r GGS-RHS/modern = 0.94), and also for traditional methods, the correlations are quite high (r GGS-FFS/traditional = 0.54; r GGS-RHS/traditional = 0.48). This suggests that the patterns for contraceptive behavior across the countries are similar in the diverse datasets and thus that the GGS data for contraception are sufficiently reliable.

Although East Germany was also characterized by limited access to modern contraceptives before German reunification in 1990, these methods became as equally widespread in the Eastern part as in the Western part quickly afterwards (Oddens et al. 1993, b; Starke and Visser 1994). In this regard, East Germany differs considerably from other former communist countries and therefore, we consider Germany as one entity at the country level.

Most studies have limited their analyses to women of reproductive age (18–49) or men with a partner of reproductive age. However, as the Austrian GGS only interviewed individuals aged between 18 and 45 we apply this age range to all the countries in our study to ensure better comparability.

This information is missing for France and therefore we only use the question “Do you intend to have a/another child during the next 3 years?”

Measurements concerning attendance of religious services are missing in the Belgian dataset and measurements concerning socialization goals for children are missing in the French and Polish dataset. In these countries, respondents are coded as “religious” if they display strong religious commitment on both available indicators.

References

- Acock AC. Working with missing values. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67(4):1012–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Adsera A. Religion and changes in family-size norms in developed countries. Review of Religious Research. 2006;47(3):271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing data. California: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JE, Jamieson DJ, Warner L, Kissin DM, Nangia AK. Contraceptive sterilization among married adults: National data on who chooses vasectomy and tubal sterilization. Contraception. 2012;85:552–557. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbo N, Billari FC, Mills M. Fertility in advanced societies: A review of research. European Journal of Population. 2013;29(1):1–38. doi: 10.1007/s10680-012-9277-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer G, Kneip T. Fertility from a couple perspective: A test of competing decision rules on proceptive behaviour. European Sociological Review. 2013;29(3):535–548. [Google Scholar]

- Becker GS. An economic analysis of fertility. In: National Bureau of Economic Research, editor. Demographic and economic change in developed countries. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1960. pp. 209–240. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley R, Kavanagh A. Gender equity and women’s contraception use. Australian Journal of Social Issues. 2008;43(1):65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg RL. A general theory of gender stratification. Sociological Theory. 1984;2:23–101. [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg RL, Coleman MT. A theoretical look at the gender balance of power in the American couple. Journal of Family Issues. 1989;10(2):225–250. doi: 10.1177/019251389010002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson E, Lamb V. Changes in contraceptive use in Bulgaria, 1995–2000. Studies in Family Planning. 2001;32(4):329–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and ORC Macro. (2003). Reproductive, maternal and child health in Eastern Europe and Eurasia: A comparative report. Atlanta, GA and Calverton, MD.

- Clark R. Three faces of women’s power and their reproductive health: A cross-national study. International Review of Modern Sociology. 2006;32(1):35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke P. When can group level clustering be ignored? Multilevel models versus single-level models with sparse data. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2008;62(8):752–758. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.060798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cliquet R, Lodewijckx E. The contraceptive transition in Flanders. European Journal of Population. 1986;2(1):71–84. doi: 10.1007/BF01796881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coale, A. (1973). The demographic transition reconsidered. In International Population Conference: Liege 1973 (Vol. 1, pp. 53–72). Liege: IUSSP.

- Coleman LM, Testa A. Sexual health knowledge, attitudes and behaviours: Variations among a religiously diverse sample of young people in London, UK. Ethnicity & Health. 2008;13(1):55–72. doi: 10.1080/13557850701803163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalla Zuanna G, De Rose A, Racioppi F. Low fertility and limited diffusion of modern contraception in Italy during the second half of the twentieth century. Journal of Population Research. 2005;22(1):21–48. [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca D. The effect of child care and part-time opportunities on participation and fertility decisions in Italy. Journal of Population Economics. 2002;15(3):549–573. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl C, Koenig M, Ruckdeschel K. Religiosity and gender equality: Comparing natives and Muslim migrants in Germany. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2009;32(2):278–301. [Google Scholar]

- Dommermuth L, Klobas J, Tappegard T. Now or later? The theory of planned behavior and the timing of fertility intentions. Advances in Life Course Research. 2011;16(1):42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin RA. An economic framework for fertility analysis. Studies in Family Planning. 1975;6(3):54–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eeckhaut, M. C. W., & Sweeney, M. M. (2013). Gender, class, and contraception in comparative context: The perplexing links between sterilization and disadvantage. Paper presented at the 2013 Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, New Orleans, USA.

- EU, GEPLAC, and Georgian Economic Trends. (2004). Georgian economic trends. Quarterly Review, No. 4.

- Eurostat. (2015a). Employment by full-time/part-time, sex and NUTS 2 regions. http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=lfst_r_lfe2eftpt&lang=en. Accessed April 22, 2015.