Abstract

In Germany, internal migration streams have shaped the population structure quite notably during the past two decades. As selective migration can have a substantial impact on the geographical distribution of health, this paper examines whether internal migrants in Germany are selected regarding their health status. To capture health selection, one measure—i.e. self-rated contentment with health—and two established risk factors for poor health—i.e. smoking and BMI—were included. Applying event history analysis, the health status of migrants was compared to non-migrants, controlling for other individual characteristics. The analyses were based on the German Socio-Economic Panel, a retrospective data set representative of the German population. Results for self-rated health and smoking were inconclusive. While self-rated health was only related to migration in men, smoking was only linked to migration in women. However, there was a clear association between BMI and migration, i.e. the propensity to migrate decreased significantly with increasing weight. The results suggest that BMI is an important indicator of increased susceptibility to ill health, which prevent people from migration. Leaving behind a population who has a greater susceptibility to chronic conditions, selective migration is likely to reinforce the consequences of population ageing and healthcare demand, in particular in regions characterized by outmigration.

Keywords: Internal migration, Healthy migrant, Health selection, Smoking, Overweight

Introduction

In Germany, internal migration streams have substantially reshaped the population structure since reunification. Between 2001 and 2010, the population of eastern Germany decreased by 5 %, from 17.1 million to 16.3 million, whereas the population of western Germany remained constant (Statistisches Bundesamt 2014). This population decline is attributable to massive outmigration streams from eastern Germany, especially from rural areas to urban areas in western Germany (Glorius 2010). Previous studies on east–west migration mainly examined the years immediately after reunification. These studies focused primarily on the reasons why eastern Germans were migrating, and on the effects of these migration streams on specific areas, including human capital (Brücker and Trübswetter 2004; Friedrich and Schultz 2005; Schultz 2004, 2009), labour market opportunities and economic prospects (Alecke et al. 2000; Kley 2013), public services and infrastructure (Daehre 2005; Sackmann et al. 2008; Neu 2009), and social consequences and future demographic prospects (e.g. fertility and family policy) (Dienel and Schnieders 2005; Roloff 2005; Gerloff 2005; Farwick 2009). Except for one comparative study for Italy and Germany by Luy and Caselli (2007) that looked at regional differences in mortality, no study has focused explicitly on the interplay of internal migration and health. This is unfortunate, as selective migration can have substantial effects on the geographical distribution of health (Norman et al. 2005; Verheij et al. 1998; Lu 2008). While good health may foster the decision to move, bad health could be an impediment to migration. Moreover, the act of migration can affect the health of those who move (Carnein et al. 2015).

So far, however, only a few studies have analysed the link between internal migration processes and health. These studies provide empirical evidence that internal migrants are positively selected regarding their health status. Verheij et al. (1998) analysed selective migration between urban and rural settings in the Netherlands and found that people who migrated from urban to rural areas did not differ in their health characteristics from people who migrated from rural to urban settings. However, they found that migrants were generally healthier than people who did not move. Norman et al. (2005) studied the area-level relationships between health and deprivation in England and Wales and found that migrants were healthier than non-migrants at younger ages. They also showed that migrants who moved from more deprived settings to less deprived areas were healthier than those who moved in the opposite direction. Moreover, they found that migrants who moved within less deprived areas were healthier than non-migrants, but that within deprived areas, migrants were less healthy than non-movers. Lu (2008) looked at internal migration streams in Indonesia and found that younger migrants were positively selected with respect to health, whereas older migrants were negatively selected. Nauman et al. (2015) compared the health status of young adult (aged 18–29) rural to urban migrants in Thailand and found that the average migrant reported having a better a priori physical health status than return migrants and those who remained at the place of origin. However, the average migrant had a worse mental health status at the time of migration than those who stayed behind.

The aim of this study was to analyse whether internal migrants in Germany are selected with regard to their health status. Event history analysis was applied to compare the health status of migrants with the health status of non-migrants, while controlling for other individual characteristics. To capture health selection, one health measure—i.e. self-rated contentment with health—and two established risk factors for poor health—i.e. smoking and overweight—were used as indicators of increased susceptibility to ill health (Verheij et al. 1998). In line with previous research findings, it was hypothesized that internal migrants in Germany are healthier than non-migrants, i.e. they are more satisfied with their health and are less likely to smoke or being overweight or obese.

Background

The Healthy Migrant Hypothesis in the International Context

The link between migration and health has not been fully understood yet and is mostly explored in the context of international migration. In general, the health of migrants is determined by the migration process itself as well as by the conditions in the sending and receiving regions (Spallek and Razum 2007). Several approaches which tried to explain the relationship between health and migration focused on the discriminating socio-demographic characteristics of migrants, which put them on an increased risk for becoming ill or dying prematurely (Razum et al. 2008; Spallek and Razum 2007; Zeeb and Razum 2006). Yet, a number of studies showed that migrants are healthier and have lower mortality rates than the average population in both the country of origin and the country of destination (Razum et al. 1998, 2008; Schenk 2007; McKay et al. 2003). This paradox is also known as the “healthy migrant effect”. This effect entails two components: the first is self-selection, suggesting that migration is a life experience requiring high levels of physical and mental health. Thus, it is assumed that migrants are more vigorous and less affected by sickness and chronic conditions, as being in poor health would be an impediment to migration. Moreover, it is hypothesized that migrants are more likely than those who stay behind to be endowed with the kind of physical and mental capabilities needed to cope with the burdens of migration. The second component is derived from the association between socio-economic discrimination and mortality. Therefore, it is posited that this health advantage is only short-termed and decreases over time as a result of migration related strains (e.g. social disadvantages, bad working conditions, restricted access to health care) (Razum et al. 2008; Razum 2009).

However, the healthy migrant effect has also been denied as an artefact resulting from erroneous migration statistics. Migration registration errors can mismatch risk and death populations, resulting in a denominator bias and, thus, an underestimation of migrant mortality. Unregistered return migration is a possible source of registration error, as many of these returns are likely to go unreported (Turra and Elo 2008). Yet, studies showed that mortality among migrants is really lower, and not the result of a data artefact (Wallace and Kulu 2014).

Similarities and Differences Between Internal and International Migration

Although internal migration flows are greater than international migration flows, researchers investigating the issues of health and migration have mainly focused on international migration (King et al. 2008), while implicitly assuming that the underlying mechanisms apply equally to internal migration processes. This makes sense, as international and internal migration flows are motivated by similar factors and follow similar patterns (Lu 2008; King et al. 2008; McKay et al. 2003). Both types of migration occur because people wish to gain access to better overall conditions in various spheres of life (Boyle et al. 1998), and involve the abandonment of familiar living environments (i.e. working environment, social ties) in order to move to a new setting. The act of moving can bring success, and/or it can be a highly stressful and disruptive experience (Boyle et al. 1998; Spallek and Razum 2007). Hence, only individuals who are physically and psychically resilient are likely to migrate, as they have the necessary resources to adapt to the new setting. But there are also some marked differences between internal and international migration. Whereas international migration involves the relocation of people across state boundaries, internal migration entails the relocation of people within the boundaries of nation states. While internal migrants may have to adjust to regional peculiarities, they usually do not need to adapt to a completely new set of cultural practices, and they are unlikely to encounter language barriers. Moreover, internal migrants do not face controls and regulations related to citizenship and are unlikely to have to struggle to gain access to education, employment, health care, and political participation (King et al. 2008). In addition, the distance covered by internal migration is often much shorter and is less likely to involve hazardous travel conditions. Finally, internal migrants are more likely than international migrants to have access to information concerning the new residence and to have tight social networks at the destination. Hence, internal migration is often less stressful than migration across national boundaries, and factors that tend to discourage international migration might not apply to internal migration. Therefore, the characteristics of internal migrants might differ from those of international migrants. The following analyses aims to answer the question whether the assumptions of the healthy migrant hypothesis are applicable to internal migration processes in Germany.

Data and Methods

The GSOEP

The analysis was based on the German Socio-Economic Panel (GSOEP). The GSOEP is a representative longitudinal survey of private households and persons and provides information on the living conditions of the German population aged 16 and above. A rather stable set of core questions are asked every year, which focus on several areas of interest, including population and demography, education, training and qualifications, labour market and occupational dynamics, earnings, income and social security, housing, health, household production, basic orientations (preferences, values, etc.), and satisfaction with certain aspects of life. Additionally, the basic information in one of these areas is enlarged through responses to more detailed questions posed in yearly topical modules.

The panel study started in 1984 with 5921 households (with a total of 12,245 individuals) in the former Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), comprising samples A (residents in the FRG) and B (foreigners in the FRG). In June 1990, the data set was expanded to the territory of the German Democratic Republic (sample C). The GSOEP is conducted annually and has been extended further by the subsamples D (Immigrants 1994/95), E (Refreshment, new independently selected sample from the private household population in Germany in 1998), F (Innovation, independently selected sample from the private household population in Germany in 2000), G (Oversampling of private households with monthly income ≥3.835 euros in 2002), and H (Refresher sample of private households in Germany in 1996). The following analysis includes the samples A, B, C, E, F, and H. Detailed information about the objectives and design of the GSOEP can be found at the homepage of the DIW (Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung; http://www.diw.de/de/soeplink) that hosts the GSOEP.

Analysis Population and Strategy

As information on smoking status and obesity has been collected on a biennial basis since 2002, the analysis was confined to every other year between 2002 and 2010. The initial study population contained 27,051 individuals aged 16 and older who were observed between 2002 and 2010. To determine the migration status of these respondents, it was necessary to observe them at least at two successive points in time during the observational period. A total of 625 respondents were excluded from the analysis because they were recorded only once between 2002 and 2010. Another 20 respondents were excluded because they provided no information at two successive points in time, or they provided incomplete migration histories. As the GSOEP is a survey of households only one male and one female household member was included into the study leaving out another 3510 respondents. To ensure independence of the study population, the following analyses were performed separately for men and women.

Hence, the analytical sample included 10,882 men and 12,014 women, amounting to 60,471 and 68,325 person-years, respectively. The respondents were followed from their first observation point until they migrated or were censored. Overall, 852 (373 men and 479 women) subjects migrated. Only the first move during the observational period was considered. As the exact migration date was unknown, the average age between the two survey years when the migration was recorded was taken as age of migration. Meanwhile, 9462 respondents were lost to follow-up due to attrition (8093 individuals) or mortality (1369 individuals). Next to mortality, individuals mainly dropped out of the study because they moved abroad, refused to reply, or could not be traced anymore (Kroh 2014). These respondents were censored at their average age between the year of the last record and the year of survey exit. For example, if an individual aged 54 responded in 2008 for the last time and was lost to follow-up by 2010, he was censored at the age of 55. Further 12,582 subjects did not move during the observation period and were censored at their age at the interview at the end of the observation period.

Applying event history analysis, the age to migration depending on health and other covariates was analysed, using a piecewise exponential model. The baseline hazard, which measures age until migration, was split into age intervals (16–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65+). Within these intervals, the hazard rate was assumed to be constant, but it could vary between them. The model can be viewed as an exponential model that controls for age as a time-varying covariate. Left truncation was controlled for by including the respondents’ age at their first observation.

Health Measures

Self-rated contentment with health was included as a health measure. Studies have shown that self-rated health is a good predictor of objective health (Subramanian et al. 2010; Miilunpalo et al. 1997). Respondents were asked to assess their health status based on a 10-point Likert scale. Those whose scores placed them among the least satisfied 30 % of the respondents were classified as rather dissatisfied, while respondents who scored above this benchmark were classified as rather satisfied.

Smoking and overweight are the most important risk factors for poor health, which affect physical ability and play essential roles in the development of chronic health conditions (Cutler et al. 2007, Preston et al. 2014). Hence, smoking and overweight were included in the analysis as indicators of an increased susceptibility to ill health (Verheij et al. 1998). Both factors may influence the decision to migrate, and shape the geographical distribution of health within a population as a consequence of migration.

People with a high BMI are more vulnerable to adverse health conditions that lead to a deterioration in physical abilities. Therefore, BMI was assumed to directly affect the migration decision. According to the healthy migrant hypothesis, people with excess weight were assumed to have a lower propensity to migrate. Information on overweight and obesity was based on self-reported measurements of weight and height. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing the weight in killogrammes by the squared height in metres (kg/m2). A BMI below 18.5 was classified as underweight. A BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 was considered normal weight. A BMI between 25 and 29.9 was categorized as overweight, and a BMI greater or equal to 30 was classified as obese.

Smoking has long-term health consequences which do not necessarily become immediately apparent, but often progress into a more severe condition (e.g. lung cancer, heart diseases) over the life course (Peto and Lopez 2004; Preston 2009). Therefore, smoking is an important risk factor that shapes the geographical distribution of health within a population as a consequence of migration. If smokers were less likely to migrate, the remaining population would be composed of more smokers who, in the long run, carried a higher risk for developing adverse health conditions related to smoking. Moreover, smoking has already adverse effects on health and physical fitness in adolescence, young adulthood, and middle age (Sandvik et al. 1995; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 1994, 2004). Therefore, it seemed reasonable to assume that smokers are less physically healthy. With regard to the healthy migrant hypothesis, smokers should have been less likely to migrate than non-smokers. Based on their answers to a question about whether they currently smoke, the respondents were classified as smokers or as non-smokers.

Covariates

The variable of interest was internal migration. The GSOEP does not ask respondents directly about their internal migration history. But owing to the longitudinal design of the data set, information about the respondent’s place of residence was available for each survey year. Therefore, individuals were defined as internal migrants if they had changed their place of residence within Germany from one federal state to another between two successive survey years. As the exact migration date was unknown, it was assumed that the migration took place at the mid-point between the two survey years. Unfortunately, relocations within federal state boundaries or information on distances could not be considered, as they were not recorded in the data set.

Information about the respondents’ gender was taken from the wave they entered the study period and was included as time-independent variable, while all other information (self-rated contentment with health, smoking, BMI, region, living arrangement, educational status, occupational status, children, satisfaction with household income, housing and leisure time, and general life satisfaction) was included in the form of time-dependent variables.

Migration can be understood as a response to a perceived disequilibrium between individual aspirations and the subjective assessment of opportunity structures within regions (Fischer and Kück 2004; Gerloff 2004). The push-and-pull factor model distinguishes between stimuli in the sending region that encourage migration (push), and incentives that spring from the receiving region (pull), and thus trigger the migration decision multi-causally. These include employment opportunities, income levels, educational opportunities, housing, infrastructure, and the perceived quality of life (Gerloff 2004; Dienel 2005).

The data set used here included information about several life parameters present at the time before migration; therefore, it was possible to control for several factors that push migration. A set of covariates was included, which was intended to reflect how contented the respondents were with their living conditions. These included the respondents’ satisfaction with their household income, their housing and their leisure time, as well as their general life satisfaction. For each variable, respondents who scored below the 30 % mark were classified as dissatisfied, while those who scored above that threshold were defined as satisfied. It was hypothesized that those respondents who were satisfied with these areas of life should have been less likely to migrate than those who were dissatisfied.

Moreover, a set of demographic confounders was included in the analysis, e.g. gender, region of origin (east or west), living arrangement (married, living in a partnership, not living in a partnership), educational status (in education, no degree, vocational degree, university degree), employment status (fully employed, part-time employed, unemployed, in education, other), and children (children, no children). For a number of respondents, there was missing information on covariates for some of the waves. These were summarized in the category no answer (n.a.).

Results

Characteristics of the Analysis Population

The distribution of person-years by covariates for the migrant population, as well as the population lost to attrition and lost to follow-up, is depicted in Table 1. Most striking is the different age distribution of migrants compared to the population lost to mortality. Whereas the migration rate was highest for the youngest age groups (16–24 and 25–34), the majority of the population lost to mortality was older than age 65. That is, migrants were typically in those ages in which mortality is low. Hence, the younger population was not selected by mortality; therefore, migration outcomes are not likely to be biased.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the analysis population in person-years (per 1000).

Source: GSOEP 2002–2010, N = 128.796 person-years

| Men | Women | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person-years | Migration | Lost to attrition | Lost to mortality | Person-years | Migration | Lost to attrition | Lost to mortality | |||||||

| Cases | Rate | Cases | Rate | Cases | Rate | Cases | Rate | Cases | Rate | Cases | Rate | |||

| Total | 60,471 | 373 | 6 | 3883 | 64 | 759 | 13 | 68,325 | 479 | 7 | 4210 | 62 | 610 | 9 |

| Age | ||||||||||||||

| 16–24 | 2747 | 84 | 31 | 252 | 92 | 1 | 0 | 3432 | 159 | 46 | 240 | 70 | 1 | 0 |

| 25–34 | 7741 | 121 | 16 | 631 | 82 | 3 | 0 | 9716 | 134 | 14 | 653 | 67 | 3 | 0 |

| 35–44 | 13,572 | 80 | 6 | 956 | 70 | 22 | 2 | 14,839 | 81 | 5 | 1005 | 68 | 11 | 1 |

| 45–54 | 12,127 | 36 | 3 | 791 | 65 | 48 | 4 | 13,242 | 44 | 3 | 838 | 63 | 32 | 2 |

| 55–64 | 10,644 | 25 | 2 | 544 | 51 | 103 | 10 | 10,989 | 30 | 3 | 484 | 44 | 71 | 6 |

| 65+ | 13,640 | 27 | 2 | 709 | 52 | 582 | 43 | 16,107 | 31 | 2 | 990 | 61 | 492 | 31 |

| Region | ||||||||||||||

| East | 16,975 | 141 | 8 | 886 | 52 | 212 | 12 | 19,027 | 203 | 11 | 956 | 50 | 172 | 9 |

| West | 43,496 | 232 | 5 | 2997 | 69 | 547 | 13 | 49,298 | 276 | 6 | 3254 | 66 | 438 | 9 |

| Living arrangement | ||||||||||||||

| Married | 41,471 | 116 | 3 | 2536 | 61 | 533 | 13 | 42,321 | 123 | 3 | 2606 | 62 | 232 | 5 |

| Partnership | 9528 | 130 | 14 | 762 | 80 | 58 | 6 | 10,574 | 182 | 17 | 730 | 69 | 30 | 3 |

| No partnership | 8371 | 107 | 13 | 511 | 61 | 165 | 20 | 14,325 | 145 | 10 | 797 | 56 | 341 | 24 |

| n.a. | 1101 | 20 | 18 | 74 | 67 | 3 | 3 | 1105 | 29 | 26 | 77 | 70 | 7 | 6 |

| Educational status | ||||||||||||||

| In education | 1322 | 44 | 33 | 113 | 85 | 1 | 1 | 1469 | 63 | 43 | 86 | 59 | 0 | 0 |

| No degree | 7022 | 46 | 7 | 583 | 83 | 121 | 17 | 14,470 | 87 | 6 | 1016 | 70 | 239 | 17 |

| Vocational degree | 37,956 | 161 | 4 | 2351 | 62 | 526 | 14 | 40,393 | 192 | 5 | 2431 | 60 | 322 | 8 |

| University degree | 12,632 | 98 | 8 | 720 | 57 | 100 | 8 | 10,193 | 98 | 10 | 534 | 52 | 39 | 4 |

| n.a. | 1539 | 24 | 16 | 116 | 75 | 11 | 7 | 1800 | 39 | 22 | 143 | 79 | 10 | 6 |

| Occupational status | ||||||||||||||

| Full-time employed | 33,921 | 183 | 5 | 2338 | 69 | 72 | 2 | 16,433 | 131 | 8 | 1012 | 62 | 18 | 1 |

| Part-time employed | 1243 | 15 | 12 | 86 | 69 | 6 | 5 | 12,518 | 52 | 4 | 781 | 62 | 13 | 1 |

| No employment | 21,770 | 113 | 5 | 1218 | 56 | 667 | 31 | 33,242 | 217 | 7 | 2057 | 62 | 572 | 17 |

| In education | 698 | 11 | 16 | 58 | 83 | 1 | 1 | 698 | 25 | 36 | 49 | 70 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 2839 | 51 | 18 | 183 | 64 | 13 | 5 | 5434 | 54 | 10 | 311 | 57 | 7 | 1 |

| Children | ||||||||||||||

| No children | 23,974 | 222 | 9 | 1575 | 66 | 383 | 16 | 14,086 | 274 | 19 | 1070 | 76 | 102 | 7 |

| ≥1 | 36,497 | 151 | 4 | 2308 | 63 | 376 | 10 | 54,239 | 205 | 4 | 3140 | 58 | 508 | 9 |

| Satisfaction with household income | ||||||||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 12,209 | 85 | 7 | 948 | 78 | 142 | 12 | 13,732 | 122 | 9 | 977 | 71 | 143 | 10 |

| Satisfied | 46,658 | 259 | 6 | 2816 | 60 | 605 | 13 | 52,906 | 312 | 6 | 3107 | 59 | 457 | 9 |

| n.a. | 1604 | 29 | 18 | 119 | 74 | 12 | 7 | 1687 | 45 | 27 | 126 | 75 | 10 | 6 |

| Satisfaction with housing | ||||||||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 11,118 | 99 | 9 | 911 | 82 | 116 | 10 | 12,833 | 144 | 11 | 944 | 74 | 119 | 9 |

| Satisfied | 48,155 | 250 | 5 | 2877 | 60 | 636 | 13 | 54,268 | 300 | 6 | 3192 | 59 | 486 | 9 |

| n.a. | 1198 | 24 | 20 | 95 | 79 | 7 | 6 | 1224 | 35 | 29 | 74 | 60 | 5 | 4 |

| Satisfaction with leisure time | ||||||||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 14,123 | 97 | 7 | 1080 | 76 | 132 | 9 | 16,601 | 127 | 8 | 1161 | 70 | 115 | 7 |

| Satisfied | 45,116 | 254 | 6 | 2717 | 60 | 613 | 14 | 50,438 | 323 | 6 | 2963 | 59 | 478 | 9 |

| n.a. | 1232 | 22 | 18 | 86 | 70 | 14 | 11 | 1286 | 29 | 23 | 86 | 67 | 17 | 13 |

| General life satisfaction | ||||||||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 12,666 | 79 | 6 | 951 | 75 | 320 | 25 | 15,412 | 92 | 6 | 1089 | 71 | 285 | 18 |

| Satisfied | 46,695 | 274 | 6 | 2852 | 61 | 431 | 9 | 51,805 | 358 | 7 | 3044 | 59 | 317 | 6 |

| n.a. | 1110 | 20 | 18 | 80 | 72 | 8 | 7 | 1108 | 29 | 26 | 77 | 69 | 8 | 7 |

| Self-rated contentment with health | ||||||||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 18,321 | 61 | 3 | 1183 | 65 | 517 | 28 | 22,597 | 102 | 5 | 1446 | 64 | 449 | 20 |

| Satisfied | 41,030 | 291 | 7 | 2617 | 64 | 234 | 6 | 44,627 | 349 | 8 | 2691 | 60 | 153 | 3 |

| n.a. | 1120 | 21 | 19 | 83 | 74 | 8 | 7 | 1101 | 28 | 25 | 73 | 66 | 8 | 7 |

| Smoking | ||||||||||||||

| Smoker | 19,733 | 126 | 6 | 1375 | 70 | 204 | 10 | 16,957 | 122 | 7 | 1126 | 66 | 77 | 5 |

| Non-smoker | 39,683 | 227 | 6 | 2434 | 61 | 552 | 14 | 50,337 | 329 | 7 | 3014 | 60 | 528 | 10 |

| n.a | 1055 | 20 | 19 | 74 | 70 | 3 | 3 | 1031 | 28 | 27 | 70 | 68 | 5 | 5 |

| BMI | ||||||||||||||

| Underweight | 299 | 8 | 27 | 21 | 70 | 12 | 40 | 1767 | 34 | 19 | 114 | 65 | 39 | 22 |

| Normal weight | 20,967 | 197 | 9 | 1452 | 69 | 292 | 14 | 33,860 | 308 | 9 | 2202 | 65 | 274 | 8 |

| Overweight | 27,445 | 118 | 4 | 1750 | 64 | 315 | 11 | 20,085 | 75 | 4 | 1158 | 58 | 180 | 9 |

| Obesity | 10,497 | 29 | 3 | 556 | 53 | 130 | 12 | 10,664 | 29 | 3 | 578 | 54 | 103 | 10 |

| n.a. | 1263 | 21 | 17 | 104 | 82 | 10 | 8 | 1949 | 33 | 17 | 158 | 81 | 14 | 7 |

The older population, however, was selected by mortality, as subjects with poor health were more likely to die. Accordingly, subjects who were less satisfied with their health were more likely to be among the population lost to mortality. The remaining population tended to be relatively fitter and healthier. This will bias the results insofar as the differences in the outcome by health will be underestimated. Beyond, there was not much difference in attrition and mortality by smoking and weight.

Model Results

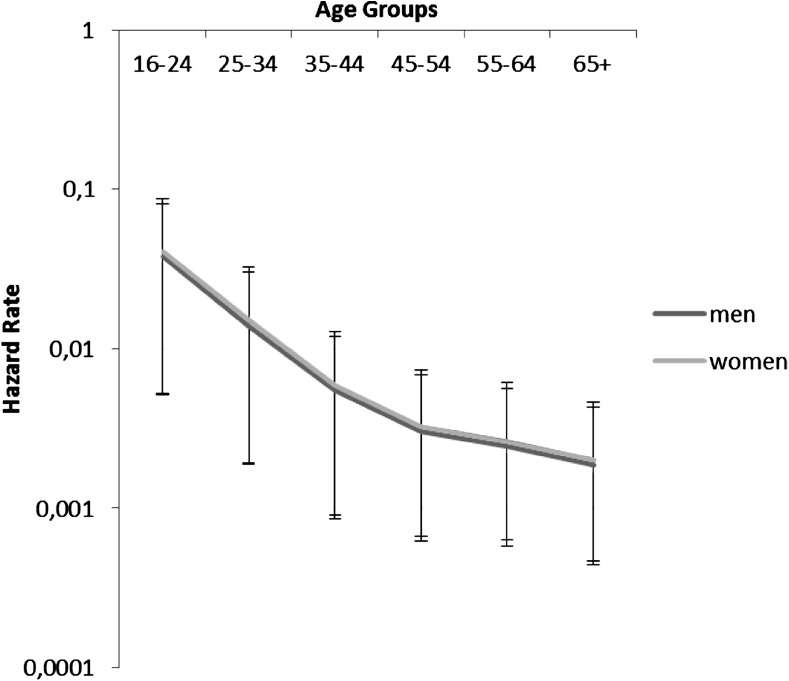

For the event history analysis, the baseline hazard was age. The propensity to migrate was highest among the youngest age group (16–25) and decreased steadily with increasing age for both sexes (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Empirical hazard rate of the risk of internal migration for men and women in Germany 2002–2010.

Source GSOEP 2002–2010

To evaluate the individual effect of the three health measures on migration, i.e. contentment with health, smoking and BMI, in a first step, each variable was fitted separately into one model only controlling for age (not depicted). For men, the propensity to migrate was significantly higher for those who were satisfied with their health (HR = 1.33, p ≤ 0.051). Non-smokers were more likely to migrate than smokers (HR = 1.25, p ≤ 0.046), and the propensity to migrate decreased with increasing weight, i.e. obese people had the lowest migration risk (HR = 0.50, p ≤ 0.001) when compared to the normal weight population. For women, health satisfaction was not related to migration (HR = 1.08, p ≤ 0.494), but smoking and overweight were. Non-smokers had a higher propensity to migrate (HR = 1.36, p ≤ 0.004), while overweight and obese people had the lowest migration risks (HRoverweight = 0.64, p ≤ 0.001, HRobesity = 0.48, p ≤ 0.000).

In a second step, nested models were used to find out the extent to which the effect of health was related to the behavioural risk factors. For men (Table 2), smoking had no effect [LR chi2 (2) = 3.68, p ≤ 0.1591], but entering BMI improved the model significantly [LR chi2 (4) = 20.75, p ≤ 0.0004]. Non-smokers were more likely to migrate, while the propensity to move decreased with increasing weight. For women (Table 3), entering both smoking [LR chi2 (2) = 9.67 p ≤ 0.0079] and BMI [LR chi2 (4) = 26.89, p ≤ 0.0000] improved the model significantly. Female non-smokers were also more likely to move, while overweight and obese women had the lowest migration risks. When entering the demographic control variables into the model (Model 4), for men only the effect of obesity remained significant. For women, the influence of both smoking and BMI remained significant. The final model included also the variables for the respondents’ satisfaction with their living conditions (Model 5). In this model, contentment with health and BMI had a significant effect on the migration propensity of men. Smokers were less likely to migrate; however, this effect was not significant. That is, men who migrated were more satisfied with their health and were less likely to be obese. For women, smoking and excess weight decreased the propensity to migrate, but there was no significant effect of health contentment.

Table 2.

Relative risk and 95 % confidence interval of internal migration for men depending on health and other covariates.

Source: GSOEP 2002–2010

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | CI low | CI up | HR | CI low | CI up | HR | CI low | CI up | HR | CI low | CI up | HR | CI low | CI up | |

| Age | |||||||||||||||

| 16–24 | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| 25–34 | 0.53*** | 0.404 | 0.708 | 0.53*** | 0.403 | 0.706 | 0.59*** | 0.446 | 0.789 | 0.73 | 0.522 | 1.027 | 0.73 | 0.518 | 1.025 |

| 35–44 | 0.21*** | 0.151 | 0.280 | 0.20*** | 0.149 | 0.276 | 0.24*** | 0.173 | 0.327 | 0.38*** | 0.254 | 0.569 | 0.38*** | 0.253 | 0.570 |

| 45–54 | 0.11*** | 0.072 | 0.159 | 0.10*** | 0.071 | 0.156 | 0.13*** | 0.086 | 0.193 | 0.20*** | 0.124 | 0.325 | 0.20*** | 0.124 | 0.327 |

| 55–64 | 0.09*** | 0.549 | 0.136 | 0.08*** | 0.525 | 0.130 | 0.10*** | 0.065 | 0.166 | 0.14*** | 0.085 | 0.243 | 0.15*** | 0.873 | 0.251 |

| 65+ | 0.07*** | 0.048 | 0.115 | 0.07*** | 0.441 | 0.108 | 0.85*** | 0.054 | 0.134 | 0.10*** | 0.058 | 0.170 | 0.10*** | 0.605 | 0.180 |

| Satisfaction with health | |||||||||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Satisfied | 1.33 | 0.999 | 1.742 | 1.31 | 0.987 | 1.741 | 1.26 | 0.950 | 1.681 | 1.29 | 0.970 | 1.724 | 1.46** | 1.074 | 1.984 |

| n.a. | 2.47*** | 1.488 | 4.111 | 2.49 | 0.552 | 11.250 | 2.63 | 0.595 | 11.605 | 2.48 | 0.499 | 12.288 | 1.52 | 0.181 | 12.705 |

| Smoking status | |||||||||||||||

| Smoker | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | |||

| Non-smoker | 1.24 | 0.993 | 1.546 | 1.26** | 1.010 | 1.572 | 1.21 | 0.963 | 1.514 | 1.24 | 0.984 | 1.554 | |||

| n.a. | 1.11 | 0.241 | 5.132 | 1.47 | 0.181 | 11.949 | 1.09 | 0.077 | 15.483 | 1.27 | 0.877 | 18.494 | |||

| Weight status | |||||||||||||||

| Underweight | 1.79 | 0.877 | 3.656 | 1.67 | 0.815 | 3.439 | 1.65 | 0.802 | 3.388 | ||||||

| normal | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | ||||||

| Overweight | 0.69*** | 0.543 | 0.872 | 0.81 | 0.634 | 1.023 | 0.80 | 0.633 | 1.022 | ||||||

| obesity | 0.51*** | 0.339 | 0.753 | 0.63** | 0.419 | 0.938 | 0.62** | 0.418 | 0.935 | ||||||

| n.a. | 0.60 | 0.109 | 3.345 | 0.77 | 0.137 | 4.360 | 0.81 | 0.147 | 4.479 | ||||||

| Region | |||||||||||||||

| East | 1.32** | 1.069 | 1.641 | 1.32** | 1.066 | 1.643 | |||||||||

| West | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | |||||||||

| Living arrangement | |||||||||||||||

| Married | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | |||||||||

| Partnership | 2.31*** | 1.709 | 3.127 | 2.29*** | 1.694 | 3.102 | |||||||||

| No partnership | 2.44*** | 1.753 | 3.403 | 2.36*** | 1.692 | 3.295 | |||||||||

| n.a. | 0.95 | 0.087 | 10.284 | 1.10 | 0.099 | 12.189 | |||||||||

| Educational status | |||||||||||||||

| In education | 1.54** | 1.005 | 2.359 | 1.55** | 1.012 | 2.387 | |||||||||

| No degree | 0.88 | 0.612 | 1.268 | 0.88 | 0.611 | 1.264 | |||||||||

| Vocational degree | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | |||||||||

| University degree | 2.14*** | 1.647 | 2.783 | 2.16*** | 1.662 | 2.813 | |||||||||

| n.a. | 1.48 | 0.735 | 2.986 | 1.50 | 0.744 | 3.025 | |||||||||

| Occupational status | |||||||||||||||

| Full time | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | |||||||||

| Part time | 1.66 | 0.973 | 2.845 | 1.70** | 0.989 | 2.919 | |||||||||

| No | 1.68** | 1.240 | 2.271 | 1.68*** | 1.221 | 2.304 | |||||||||

| Education | 0.58 | 0.278 | 1.195 | 0.58 | 0.278 | 1.208 | |||||||||

| Other | 2.35*** | 1.543 | 3.579 | 2.39*** | 1.557 | 3.664 | |||||||||

| Children | |||||||||||||||

| ≥1 | 1.13 | 0.868 | 1.471 | 1.13 | 0.866 | 1.471 | |||||||||

| No children | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | |||||||||

| Satisfaction with household income | |||||||||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 1.00 | – | – | ||||||||||||

| Satisfied | 1.17 | 0.879 | 1.553 | ||||||||||||

| n.a. | 1.24 | 0.561 | 2.756 | ||||||||||||

| Satisfaction with housing | |||||||||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 1.00 | – | – | ||||||||||||

| Satisfied | 0.75** | 0.580 | 0.965 | ||||||||||||

| n.a. | 1.34 | 0.386 | 4.671 | ||||||||||||

| Satisfaction with leisure time | |||||||||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 1.00 | – | – | ||||||||||||

| Satisfied | 0.90 | 0.700 | 1.160 | ||||||||||||

| n.a. | 1.23 | 0.220 | 6.865 | ||||||||||||

| General life satisfaction | |||||||||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 1.00 | – | – | ||||||||||||

| Satisfied | 0.80 | 0.593 | 1.075 | ||||||||||||

| n.a. | 0.43 | 0.328 | 5.527 | ||||||||||||

| Likelihood-ratio-test | LR chi2 (2) = 3.68 | LR chi2 (4) = 20.75 | LR chi2 (13) = 123.24 | LR chi2 (8) = 11.69 | |||||||||||

| p ≤ 0.1591 | p ≤ 0.0004 | p ≤ 0.0000 | p ≤ 0.1658 | ||||||||||||

** p ≤ 0.05; *** p ≤ 0.001; CI 95 %

Table 3.

Relative risk and 95 % confidence interval of internal migration for women depending on health and other covariates.

Source: GSOEP 2002–2010

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | CI low | CI up | HR | CI low | CI up | HR | CI low | CI up | HR | CI low | CI up | HR | CI low | CI up | |

| Age | |||||||||||||||

| 16–24 | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| 25–34 | 0.31*** | 0.243 | 0.385 | 0.30*** | 0.237 | 0.376 | 0.32*** | 0.251 | 0.401 | 0.56*** | 0.316 | 0.535 | 0.56*** | 0.421 | 0.738 |

| 35–44 | 0.12*** | 0.094 | 0.161 | 0.12*** | 0.092 | 0.157 | 0.13*** | 0.100 | 0.173 | 0.34*** | 0.175 | 0.345 | 0.35*** | 0.245 | 0.497 |

| 45–54 | 0.08*** | 0.054 | 0.106 | 0.07*** | 0.052 | 0.102 | 0.08*** | 0.060 | 0.120 | 0.22*** | 0.097 | 0.223 | 0.23*** | 0.152 | 0.349 |

| 55–64 | 0.06*** | 0.421 | 0.092 | 0.06*** | 0.039 | 0.087 | 0.07*** | 0.047 | 0.106 | 0.16*** | 0.694 | 0.171 | 0.17*** | 0.107 | 0.267 |

| 65+ | 0.04*** | 0.300 | 0.066 | 0.04*** | 0.027 | 0.060 | 0.05*** | 0.033 | 0.074 | 0.07*** | 0.029 | 0.071 | 0.08*** | 0.051 | 0.128 |

| Satisfaction with health | |||||||||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Satisfied | 1.08 | 0.863 | 1.357 | 1.05 | 0.836 | 1.319 | 1.00 | 0.800 | 1.262 | 1.07 | 0.910 | 1.440 | 1.15 | 0.902 | 1.478 |

| n.a. | 2.38*** | 1.555 | 3.644 | 1.09 | 0.256 | 4.653 | 1.07 | 0.255 | 4.507 | 0.69 | 0.151 | 3.944 | 0.47 | 0.035 | 6.304 |

| Smoking status | |||||||||||||||

| Smoker | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | |||

| Non-smoker | 1.36*** | 1.102 | 1.683 | 1.37** | 1.110 | 1.695 | 1.41** | 1.259 | 1.933 | 1.43** | 1.154 | 1.782 | |||

| n.a. | 2.72 | 0.640 | 11.571 | 3.31 | 0.667 | 16.396 | 2.56 | 0.481 | 16.482 | 2.02 | 0.259 | 15.767 | |||

| Weight status | |||||||||||||||

| Underweight | 1.21 | 0.845 | 1.735 | 1.03 | 0.766 | 1.553 | 1.05 | 0.733 | 1.509 | ||||||

| Normal | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | ||||||

| Overweight | 0.64*** | 0.495 | 0.830 | 0.72** | 0.497 | 0.844 | 0.71** | 0.551 | 0.928 | ||||||

| Obesity | 0.48*** | 0.327 | 0.708 | 0.52*** | 0.326 | 0.719 | 0.52** | 0.350 | 0.764 | ||||||

| n.a. | 0.73 | 0.315 | 1.700 | 0.80 | 0.331 | 1.857 | 0.82 | 0.346 | 1.953 | ||||||

| Region | |||||||||||||||

| East | 1.72*** | 1.503 | 2.173 | 1.70*** | 1.408 | 2.052 | |||||||||

| West | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | |||||||||

| Living arrangement | |||||||||||||||

| Married | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | |||||||||

| Partnership | 2.19*** | 1.751 | 3.029 | 2.10*** | 1.600 | 2.763 | |||||||||

| No partnership | 2.57*** | 2.311 | 3.995 | 2.46*** | 1.864 | 3.236 | |||||||||

| n.a. | 2.92 | 0.740 | 9.567 | 2.63 | 0.666 | 10.427 | |||||||||

| Educational status | |||||||||||||||

| In education | 0.96 | 0.732 | 1.484 | 0.95 | 0.653 | 1.376 | |||||||||

| No degree | 1.13 | 0.942 | 1.621 | 1.09 | 0.824 | 1.436 | |||||||||

| Vocational degree | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | |||||||||

| University degree | 1.80*** | 1.402 | 2.324 | 1.81*** | 1.406 | 2.332 | |||||||||

| n.a. | 1.76 | 1.157 | 3.170 | 1.69 | 0.993 | 2.871 | |||||||||

| Occupational status | |||||||||||||||

| Full time | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | |||||||||

| Part time | 1.16 | 0.828 | 1.631 | 1.13 | 0.809 | 1.588 | |||||||||

| No | 2.02*** | 1.674 | 2.804 | 1.93*** | 1.475 | 2.513 | |||||||||

| Education | 1.46 | 1.065 | 2.910 | 1.40 | 0.833 | 2.363 | |||||||||

| Other | 1.28 | 0.948 | 2.153 | 1.25 | 0.811 | 1.922 | |||||||||

| Children | |||||||||||||||

| ≥1 | 0.54*** | 0.341 | 0.546 | 0.51*** | 0.400 | 0.652 | |||||||||

| No children | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | |||||||||

| Satisfaction with household income | |||||||||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 1.00 | – | – | ||||||||||||

| Satisfied | 0.88 | 0.696 | 1.121 | ||||||||||||

| n.a. | 1.11 | 0.603 | 2.040 | ||||||||||||

| Satisfaction with housing | |||||||||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 1.00 | – | – | ||||||||||||

| satisfied | 0.62*** | 0.500 | 0.773 | ||||||||||||

| n.a. | 1.05 | 0.430 | 2.551 | ||||||||||||

| Satisfaction with leisure time | |||||||||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 1.00 | – | – | ||||||||||||

| Satisfied | 0.98 | 0.786 | 1.227 | ||||||||||||

| n.a. | 0.78 | 0.122 | 4.980 | ||||||||||||

| General life satisfaction | |||||||||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 1.00 | – | – | ||||||||||||

| Satisfied | 1.14 | 0.875 | 1.488 | ||||||||||||

| n.a. | 1.71 | 0.379 | 7.746 | ||||||||||||

| Likelihood-ratio-test | LR chi2 (2) = 9.67 | LR chi2 (4) = 26.89 | LR chi2 (13) = 197.87 | LR chi2 (8) = 24.08 | |||||||||||

| p ≤ 0.0079 | p ≤ 0.0000 | p ≤ 0.0000 | p ≤ 0.0022 | ||||||||||||

** p ≤ 0.05; *** p ≤ 0.001; CI 95 %

For both sexes, the findings for the confounding demographic variables were consistent with previous research. In line with past population trends, the migrants were more likely to come from eastern Germany than from western Germany. Marriage seemed to have prevented people from moving, whereas respondents who were living in a partnership and those who were single had significantly higher migration risks. Regarding education, the migration risk was highest among respondents with a university degree. Moreover, unemployment was a strong predictor for migration. Being in part-time employment was not significant for women, but for men. Having children prevented only women from migration. Entering the contentment measures revealed that most of them were insignificant. However, respondents who were satisfied with their housing were less likely to migrate than those who were dissatisfied.

Discussion

This is the first study that analysed the influence of health on internal migration in Germany. The results showed that internal migrants in Germany are, to some extent, selected regarding their health, and thus confirm the earlier findings from other countries (Lu 2008; Nauman et al. 2015; Norman et al. 2005, Verheij et al. 1998). The analysed health measures affected men’s and women’s migration behaviour in different ways. Self-rated contentment with health, which was included as a predictor for objective health status, was only associated with the migration status of men, but not of women. This finding suggests that factors other than self-rated health play a more important role in the migration behaviour of women. Further analysis is needed to identify these factors and to understand their modes of action. However, this analysis relied on self-rated health only, as no other objective health measure was available. Studies have shown that women, especially younger women, rate their health poorer than men do (Eriksson et al. 2001). Therefore, including a more objective health measurement might have led to different results.

Current smoking status was not clearly associated with migration. This is probably explained by the lag between smoking exposure and the occurrence of negative health consequences. Nonetheless, it was important to check for a potential selection effect, as smoking is an important risk factor that shapes the geographical distribution of health within a population. The results showed that women who did not smoke were more likely to migrate. This implies that the remaining female population is composed of more smokers who, in the long run, carry a higher risk for developing smoking-related adverse health conditions.

The findings for BMI, on the other hand, clearly supported the healthy migrant hypothesis. BMI was significantly associated with migration for both men and women in that the propensity to migrate decreased significantly with increasing weight. BMI is related to a number of health limitations that become effective quite immediately. Therefore, BMI is a good indicator of an increased susceptibility to ill health.

To conclude, these findings suggest that the assumptions of the healthy migrant hypothesis are partly applicable to internal migration processes in Germany. While results for self-rated health and smoking were inconclusive, there was a clear association between BMI and migration for both, men and women. Thus, being overweight or obese is indicative of an increased susceptibility to ill health, which seemed to prevent people from migration.

Germany’s population structure has been characterized by population ageing. Older populations tend to have higher rates of chronic diseases and to make greater use of medical and other care facilities, which implies an increased need for health-related resources and services (Patrick 1980). Projections for Germany indicated that the number of a wide spectrum of age-related diseases, including community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), dementia, heart attack, stroke, several cancers, diabetes, arthritis, and osteoporosis, will increase in the next couple of years (Peters et al. 2010; Siewert et al. 2010). All these conditions are associated with smoking and excess weight. However, these projections did not consider changes in the prevalence of risk factors and are, thus, likely to underestimate the real disease burden.

Germany has been characterized by regional disparities in the capacity for medical provision. Studies showed that the number of healthcare facilities declines with decreasing community size. Structurally weak and/or peripheral rural regions are particularly affected due to their sparse infrastructure (Walter and Altgeld 2000). This partly precarious situation could be reinforced by selective migration and the associated changes in the distribution of risk factors. The results of this study showed that migrants are predominantly young and healthy and thus leave behind a population that diminishes in size and becomes older and less healthy (Dienel 2005; Verheij et al. 1998; Norman et al. 2005). Moreover, the migrants were less likely to be overweight or obese, and female migrants were more frequently non-smokers. This implies that the remaining population will be eventually left with a population who have a greater susceptibility to chronic conditions and thus to having disabilities. This, in turn, increases the demand for public healthcare provision, especially in regions characterized by outmigration, and requires the improvement and further development of existing and new innovative approaches to provide medical care. Among them are models for early detection, outreach care, and the use of telemedicine (Siewert et al. 2010).

Concerning demographic confounders, the results were in line with findings from other studies: i.e. the migrants are predominantly unmarried. This can be because married people are more likely to have established their centre of life within a stable family network. Studies suggested that it is more difficult to make migration decisions within a stable partnership. In addition, the more intimately people are involved in their networks, the lower their risk of migration (Gerloff 2005). This idea is supported by the finding that subjects who were satisfied with their housing were less likely to migrate. Moreover, while children were no migration impediment for men, having children lowered the migration propensity of women. However, running an interaction model (not depicted but available on request) showed that women with children who are in their middle ages (ages 25–44) had a lower risk to migrate, while older women (aged 55 and above) with children had a higher migration risk. This could reflect the fact that their children have mostly grown up and left home at these ages, which offers new possibilities and room for migration decisions for the parents.

Studies have shown that the decision to migrate is highly motivated by the relative levels of unemployment. Moreover, differences in the quality and the standards of the underlying working conditions, e.g. the work environment, the number of extra hours that must be worked without pay, the insecurity of the workplace, and the training opportunities are important triggers for migration (Friedrich and Schultz 2005; Gerloff 2005). This study’s findings confirm the importance of employment status for migration decisions as the probability of migration increased for the unemployed. Furthermore, more highly educated people were the most likely to migrate. This reinforces the idea of “brain drain”, i.e. selective migration of highly educated people, which results in a decline in human capital and a worsening of future prospects in the sending regions. The strength of this study is that it used data from a prospective panel, and was therefore not prone to recall bias. It was representative of the total German population, contained a sufficient number of internal migration cases, and included a direct subjective health measure, as well as two established health risk factors which allowed for making inferences about the individuals’ susceptibility to ill health. Moreover, the data set provided a set of control variables that are closely linked to migration.

This study has also a series of limitations. Regarding the longitudinal study design, the healthy migrant effect may have been biased in several ways. First, the study population itself could have been selected in that individuals with particularly bad health may have refused to participate in the study. In this case, the healthy migrant effect would have been underestimated. Another potential source of bias is informative censoring due to mortality selection, as subjects in the lost to mortality group could have been in such a bad health that prevented them from migration. The results of this study showed that migrants were typically not yet in those ages in which the risk of mortality is high. In a sensitivity analysis, a competing risk analysis was performed, which showed that the results for migration were not altered by the effect of mortality (see Tables 4, 5 in Appendix). Therefore, it is unlikely that these findings were biased by mortality selection. Attrition rates in this study were higher than migration or mortality rates, i.e. the population of interest was more likely to be among the population lost to follow-up. If this attrition was due to migration, the results could have been biased by the excessive losses of smokers, overweight and obese people, as well as health contented people. Yet, even assuming that all of these attrition cases were migration related, the effect of the health indicator variables would have remained, albeit attenuated (not depicted).

Table 4.

Cox proportional hazard ratios for the risk of migration and competing risk regression for the population lost to attrition and lost to mortality, men

Source: GSOEP 2002–2010

| Men | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Migration | Lost to attrition | Lost to mortality | |||||||

| HR | CI low | CI up | SHR | CI low | CI up | SHR | CI low | CI up | |

| Satisfaction with health | |||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Satisfied | 1.39** | 1.029 | 1.902 | 1.32 | 0.958 | 1.810 | 1.43** | 1.041 | 1.971 |

| n.a. | 1.41 | 0.176 | 11.353 | 1.07 | 0.295 | 4.401 | 1.44 | 0.325 | 6.398 |

| Smoking status | |||||||||

| Smoker | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Non-smoker | 1.23 | 0.979 | 1.548 | 1.27** | 1.002 | 1.614 | 1.24 | 0.984 | 1.561 |

| n.a. | 1.44 | 0.105 | 19.579 | 2.01 | 0.714 | 5.635 | 1.46 | 0.476 | 4.502 |

| Weight status | |||||||||

| Underweight | 1.63 | 0.793 | 3.368 | 1.43 | 0.655 | 3.140 | 1.62 | 0.755 | 3.471 |

| Normal | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Overweight | 0.83 | 0.652 | 1.054 | 0.91 | 0.709 | 1.165 | 0.83 | 0.653 | 1.061 |

| Obesity | 0.65** | 0.437 | 0.980 | 0.76 | 0.511 | 1.143 | 0.66** | 0.440 | 0.976 |

| n.a. | 0.83 | 0.152 | 4.572 | 0.72 | 0.164 | 3.127 | 0.83 | 0.185 | 3.718 |

| Region | |||||||||

| East | 1.33** | 1.071 | 1.652 | 1.46** | 1.167 | 1.832 | 1.33** | 1.066 | 1.658 |

| West | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Living arrangement | |||||||||

| Married | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Partnership | 2.13*** | 1.565 | 2.897 | 1.82*** | 1.299 | 2.539 | 1.33*** | 1.533 | 2.939 |

| No partnership | 2.24*** | 1.598 | 3.148 | 2.06*** | 1.409 | 3.008 | 2.23*** | 1.563 | 3.175 |

| n.a. | 1.05 | 0.104 | 10.740 | 1.29 | 0.679 | 2.459 | 1.03 | 0.567 | 1.887 |

| Educational status | |||||||||

| In education | 1.34 | 0.870 | 2.060 | 1.16 | 0.761 | 1.777 | 1.34 | 0.882 | 2.024 |

| No degree | 0.82 | 0.560 | 1.195 | 0.59** | 0.409 | 0.864 | 0.81 | 0.569 | 1.167 |

| vocational degree | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| University degree | 2.32* | 1.777 | 3.031 | 2.55*** | 1.940 | 3.365 | 2.34*** | 1.787 | 3.059 |

| n.a. | 1.34 | 0.621 | 2.913 | 1.16 | 0.668 | 2.023 | 1.35 | 0.701 | 2.582 |

| Occupational status | |||||||||

| Full time | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Part time | 1.63 | 0.945 | 2.800 | 1.56** | 0.901 | 2.695 | 1.63 | 0.964 | 2.774 |

| No | 1.54** | 1.114 | 2.133 | 1.46** | 1.060 | 1.998 | 1.54** | 1.111 | 2.146 |

| Education | 0.48 | 0.223 | 1.023 | 0.37** | 0.175 | 0.767 | 0.48** | 0.226 | 1.000 |

| Other | 2.14** | 1.392 | 3.299 | 2.03 | 1.323 | 3.121 | 2.16*** | 1.414 | 3.288 |

| Children | |||||||||

| ≥1 | 1.25 | 0.955 | 1.641 | 1.49** | 1.114 | 1.979 | 1.26 | 0.952 | 1.658 |

| No children | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Satisfaction with household income | |||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Satisfied | 1.66 | 0.878 | 1.550 | 1.22 | 0.906 | 1.641 | 1.16 | 0.871 | 1.555 |

| n.a. | 1.19 | 0.543 | 2.621 | 1.15 | 0.532 | 2.496 | 1.19 | 0.541 | 2.634 |

| Satisfaction with housing | |||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Satisfied | 0.74** | 0.577 | 0.960 | 0.77** | 0.602 | 0.998 | 0.74*** | 0.578 | 0.951 |

| n.a. | 1.36 | 0.398 | 4.621 | 1.04 | 0.298 | 3.631 | 1.36 | 0.399 | 4.655 |

| Satisfaction with leisure time | |||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Satisfied | 0.91 | 0.709 | 1.176 | 0.95 | 0.742 | 1.215 | 0.91 | 0.718 | 1.160 |

| n.a. | 1.24 | 0.226 | 6.813 | 1.40 | 0.292 | 6.705 | 1.24 | 0.236 | 6.497 |

| General life satisfaction | |||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Satisfied | 0.77 | 0.570 | 1.035 | 0.79 | 0.579 | 1.084 | 0.78** | 0.572 | 1.058 |

| n.a. | 0.44 | 0.372 | 5.261 | 0.53 | 0.244 | 1.144 | 0.45 | 0.203 | 0.995 |

** p ≤ 0.05;*** p ≤ 0.001; CI 95 %

Table 5.

Cox proportional hazard ratios for the risk of migration and competing risk regression for the population lost to attrition and lost to mortality, women

Source: GSOEP 2002–2010

| Women | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Migration | Lost to attrition | Lost to mortality | |||||||

| HR | CI low | CI up | SHR | CI low | CI up | SHR | CI low | CI up | |

| Satisfaction with health | |||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Satisfied | 1.12 | 0.872 | 1.429 | 1.08 | 0.844 | 1.376 | 1.13 | 0.883 | 1.441 |

| n.a. | 0.49 | 0.038 | 6.477 | 0.52 | 0.111 | 2.467 | 0.49 | 0.830 | 2.942 |

| Smoking status | |||||||||

| Smoker | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Non-smoker | 1.43** | 1.151 | 1.779 | 1.53*** | 1.223 | 1.916 | 1.43** | 1.152 | 1.783 |

| n.a. | 2.15 | 0.268 | 17.230 | 2.54 | 0.967 | 6.695 | 2.15 | 0.798 | 5.805 |

| Weight status | |||||||||

| Underweight | 1.03 | 0.715 | 1.474 | 1.01 | 0.694 | 1.475 | 1.02 | 0.705 | 1.487 |

| Normal | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Overweight | 0.73** | 0.564 | 0.951 | 0.77** | 0.599 | 1.001 | 0.73** | 0.571 | 0.946 |

| Obesity | 0.54** | 0.367 | 0.803 | 0.60** | 0.412 | 0.887 | 0.54** | 0.373 | 0.796 |

| n.a. | 0.83 | 0.350 | 1.988 | 0.67 | 0.271 | 1.647 | 0.84 | 0.352 | 2.002 |

| Region | |||||||||

| East | 1.64*** | 1.355 | 1.977 | 1.68*** | 1.386 | 2.033 | 1.64*** | 1.356 | 1.976 |

| West | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Living arrangement | |||||||||

| Married | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Partnership | 1.98*** | 1.502 | 2.616 | 1.73*** | 1.294 | 2.314 | 1.98*** | 1.485 | 2.641 |

| No partnership | 2.35*** | 1.773 | 3.105 | 2.40*** | 1.809 | 3.195 | 2.35*** | 1.775 | 3.099 |

| n.a. | 2.51 | 0.626 | 10.066 | 2.21 | 0.735 | 6.651 | 2.49 | 0.867 | 7.136 |

| Educational status | |||||||||

| In education | 0.87 | 0.596 | 1.273 | 0.79 | 0.524 | 1.183 | 0.87 | 0.586 | 1.304 |

| no degree | 0.90 | 0.669 | 1.214 | 0.75 | 0.555 | 1.021 | 0.90 | 0.670 | 1.220 |

| Vocational degree | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| University degree | 1.90*** | 1.474 | 2.454 | 2.09** | 1.620 | 2.699 | 1.91*** | 1.482 | 2.456 |

| n.a. | 1.50 | 0.880 | 2.551 | 1.30 | 0.810 | 2.076 | 1.51 | 0.944 | 2.414 |

| Occupational status | |||||||||

| Full time | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Part time | 1.09 | 0.780 | 1.534 | 1.02 | 0.730 | 1.434 | 1.09 | 0.780 | 1.529 |

| No | 1.68*** | 1.277 | 2.207 | 1.52** | 1.146 | 2.018 | 1.67*** | 1.255 | 2.232 |

| Education | 1.07 | 0.623 | 1.828 | 0.85 | 0.481 | 1.508 | 1.07 | 0.607 | 1.873 |

| Other | 1.13 | 0.732 | 1.741 | 1.06 | 0.688 | 1.633 | 1.13 | 0.735 | 1.730 |

| Children | |||||||||

| ≥1 | 0.60*** | 0.465 | 0.772 | 0.77** | 0.602 | 0.979 | 0.60*** | 0.470 | 0.770 |

| No children | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Satisfaction with household income | |||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Satisfied | 0.87 | 0.689 | 1.110 | 0.93 | 0.728 | 1.188 | 0.88 | 0.687 | 1.116 |

| n.a. | 0.93 | 0.500 | 1.731 | 0.82 | 0.431 | 1.548 | 0.93 | 0.493 | 1.754 |

| Satisfaction with housing | |||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Satisfied | 0.61*** | 0.493 | 0.763 | 0.66*** | 0.527 | 0.830 | 0.61*** | 0.491 | 0.767 |

| n.a. | 0.99 | 0.401 | 2.424 | 1.29 | 0.524 | 3.191 | 0.99 | 0.389 | 2.523 |

| Satisfaction with leisure time | |||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Satisfied | 1.00 | 0.802 | 1.253 | 0.98 | 0.785 | 1.231 | 1.00 | 0.801 | 1.254 |

| n.a. | 0.89 | 0.142 | 5.569 | 1.10 | 0.226 | 5.343 | 0.89 | 0.154 | 5.185 |

| General life satisfaction | |||||||||

| Unsatisfied | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Satisfied | 1.09 | 0.837 | 1.425 | 1.09 | 0.839 | 1.416 | 1.10 | 0.848 | 1.434 |

| n.a. | 1.64 | 0.361 | 7.402 | 1.37 | 0.485 | 3.887 | 1.64 | 0.670 | 4.020 |

** p ≤ 0.05;*** p ≤ 0.001; CI 95 %

Furthermore, this study could have been biased by left truncation, as it provided no information about the migration behaviour and/or the health status of respondents before they entered the observation period. Hence, migration history and related health changes could not be considered. However, the goal of this study was not to analyse the effect of health on migration transitions over the life course, but rather to determine whether individuals who migrated during a certain time period were positively selected with regard to health. Moreover, it is likely that some respondents were lost to follow-up due to migration. As these respondents were included in the censored population, their health status could not be considered in this analysis.

Due to data restrictions, this study provides no information about migration that took place within federal states. Yet, some of the migration activity may have occurred within the state boundaries of some of the larger federal states, such as Bavaria or North Rhine-Westphalia. If these migrants were selected on the basis of health as well, the result of this analysis underestimated the effect of selective migration. If, however, they were unselected, the results will be unchanged. Moreover, this study disregards potential re-migrants. Studies have shown that re-migration occurs predominantly among people who failed to adapt to their new job or setting (Friedrich and Schultz 2005). As unhappiness affects health satisfaction negatively (Graham 2008), including re-migrants in this analysis would have mitigated the healthy migrant effect.

Another drawback of this study is its use of self-reported BMI to reflect body composition, as this indicator fails to distinguish between lean and fat body mass. Moreover, as the BMI cut-off points are set regardless of sex or skeletal frame, some individuals may be wrongly assigned to a weight category, which could have lead to an underestimation of the extent of the overweight problem (Burkhauser and Cawley 2008). Furthermore, compared to objective measurements, a reliance on subjective information on weight and height tends to lead to an underestimation of body mass index (Glaesmer and Brähler 2002). Therefore, the number of overweight and obese people in this study could be underestimated. Despite these potential problems, BMI was chosen to be included in the analysis because it is a commonly used and widely available measure of excess weight.

The goal in this paper was to gain a better understanding of the influence of health on internal migration in Germany. Thus, population ageing in Germany and the associated challenges for the healthcare system may be reinforced by selective migration. To provide us with a better understanding of the health consequences of selective migration, future research should attempt to analyse the effects of internal migration on small-scale regional health variations using suitable data. It would also be interesting to study whether health selection diminishes with spatial and/or cultural proximity. Moreover, future research is needed to detect whether selective migration has any long-term effects on population health.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the European Regional Development Fund (EFRE) and European Social Fund (ESF), Grant No. AU 09 046:ESF/IV-BM-B35-0005/12, for financial support.

Appendix

References

- Alecke B, Mitze T, Untiedt G. Internal migration, regional labour market dynamics and implications for German East–West disparities: Results from a Panel VAR. Jahrbuch für Regionalwissenschaft. 2000;30:159–189. doi: 10.1007/s10037-010-0045-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle P, Halfacree K, Robinson V. Exploring contemporary migration. Essex: Pearson Education Limited; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Brücker, H., & Trübswetter, P. (2004). Do the best go West? An analysis of the self-selection of employed East-West-migrants in Germany. German Institute for Economic Research, Discussion Paper (p. 396).

- Burkhauser RV, Cawley J. Beyond BMI: The value of more accurate measures of fatness and obesity in social science research. Journal of Health Economics. 2008;27:519–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnein M, Milewski N, Doblhammer G, Nusselder WJ. Health inequalities of immigrants: Patterns and determinants of health expectancies of Turkish migrants living in Germany. In: Doblhammer G, editor. Health among the elderly in Germany, series on population studies. Berlin: Barbara Budrich Publishers; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler, D. M., Glaeser, E. L., Rosen, A. B. (2007) Is the US population behaving healthier? NBER Working Paper No. 13013

- Daehre K-H. Metropol-regionen - Wachstumskerne der Zukunft. In: Dienel C, editor. Abwanderung, Geburtenrückgang und regionale Entwicklung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag; 2005. pp. 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Dienel C. Theorie und Praxis regionaler Bevölkerungsentwicklung in Ostdeutschland. In: Dienel C, editor. Abwanderung, Geburtenrückgang und regionale Entwicklung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag; 2005. pp. 7–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dienel C, Schnieders G. Erfolgskonzept kommunale Frauenpolitik? Das Beispiel Emsland. In: Dienel C, editor. Abwanderung, Geburtenrückgang und regionale Entwicklung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag; 2005. pp. 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson I, Unden A-L, Elofsson S. Self-rated health. Comparisons between different measures. Results from a population study. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;30:326–333. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.2.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farwick, A. (2009). Internal migration. Challenges and perspectives for the research infrastructure. German Council for Social and Economic Data (RatSWD), working paper no. 97.

- Fischer H, Kück U. Migrationsgewinner und Verlierer: Mecklenburg-Vorpommern im Vergleich. In: Werz N, editor. Abwanderung und Migration in Mecklenburg und Vorpommern. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich K, Schultz A. Mit einem Bein noch im Osten? Abwanderung aus Ostdeutschland in sozialgeographischer Perspektive. In: Dienel C, editor. Abwanderung, Geburtenrückgang und regionale Entwicklung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag; 2005. pp. 203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Gerloff A. Besonderheiten im Wanderungsverhalten von Frauen und Männern in Sachsen-Anhalt. In: Werz N, editor. Abwanderung und Migration in Mecklenburg und Vorpommern. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gerloff A. Abwanderung und Heimatbindung junger Menschen aus Sachsen-Anhalt-Ergebnisse einer empirischen Untersuchung. In: Dienel C, editor. Abwanderung, Geburtenrückgang und regionale Entwicklung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag; 2005. pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Glaesmer H, Brähler E. Schätzung der Prävalenz von Übergewicht und Adipositas auf der Grundlage subjektiver Daten zum Body-Mass-Index (BMI) Gesundheitswesen. 2002;64:133–138. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-22317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glorius B. Go west: Internal migration in Germany after reunification. Belgeo. 2010;3(2010):281–292. doi: 10.4000/belgeo.6470. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham C. Happiness and health: Lessons and questions for public policy. Health Affairs. 2008;27(1):72–87. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, R., Skeldon, R., & Vullnetari, J. (2008). Internal and international migration: Bridging the theoretical divide. University of Sussex. Sussex Centre for Migration Research, working paper 52.

- Kley SA. Migration in the face of unemployment and unemployment risk: A case study of temporal and regional effects. Comparative Population Studies – Zeitschrift für Bevölkerungswissenschaft. 2013;38(1):109–136. [Google Scholar]

- Kroh, M. (2014). Documentation of sample sizes and panel attrition in the German socio-economic panel (SOEP) (1984 until 2012). In D. Berlin (Ed.), SOEP survey papers.

- Lu Y. Test of the ‘healthy migrant hypothesis’: A longitudinal analysis of health selectivity of internal migration in Indonesia. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;67:1331–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luy M, Caselli G. The impact of a migration-caused selection effect on regional mortality differences in Italy and Germany. Genus. 2007;63(1/2):33–64. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, L., Macintyre, S., & Ellaway, S. (2003). Migration and health: A review of the international literature. Occasional paper series. MRC Social & Public Health Sciences Unit.

- Miilunpalo S, Vuori I, Oja P, Pasanen M, Urponen H. Self-rated health status as a health measure: the predictive value of self-reported health status on the use of physician services and on mortality in the working-age population. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1997;50(5):517–528. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(97)00045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauman E, VanLandingham M, Anglewicz P, Patthavanit U, Punpuing S. Rural-to-urban migration and changes in health among young adults in Thailand. Demography. 2015;52:233–257. doi: 10.1007/s13524-014-0365-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neu C. Daseinsvorsorge (Demografischer Wandel - Hintergründe und Herausforderungen) Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Norman P, Boyle P, Rees P. Selective migration, health and deprivation: A longitudinal analysis. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;60:2755–2771. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CH. Health and migration of the elderly. Research on Aging. 1980;2:233–241. doi: 10.1177/016402758022011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters E, Pritzkuleit R, Beske F, Katalinic A. Demografischer wandel und Krankheitshäufigkeiten. Eine Projektion bis 2050. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz. 2010;53:417–426. doi: 10.1007/s00103-010-1050-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peto R, Lopez AD. The future worldwide health effects of current smoking patterns. In: Boyle P, Gray N, Henningfield J, Seffrin J, Zatonski W, editors. Tobacco and public health: Science and policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, S. H. (2009). Causes of lagging life expectancy at older ages in the United States. Paper presented at the 11th annual joint conference of the retirement research consortium, Washington, D.C., 10–11 August

- Razum, O. (2009). Migration, Mortalität und der Healthy-Migrant-Effekt. In M. Richter, & K. Hurrelmann (Eds.), Gesundheitliche Ungleichheit. Grundlagen, Probleme und Persepektiven (2nd ed., pp. 257–282). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Razum O, Zeeb H, Akgün HS, Yilmaz S. Low overall mortality of Turkish residents in Germany persists and extends into a second generation: merely a healthy migrant effect? Tropical Medicine and International Health. 1998;3(4):297–303. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razum, O., Zeeb, H., Meesmann, U., Schenk, L., Bredehorst, L., Brzoska, P., et al. (2008). Migration und Gesundheit. In R. Koch-Institut (Ed.), Schwerpunktbericht der Gesundheitsberichtserstattung des Bundes. Berlin: Robert-Koch-Institut.

- Roloff J. Geburtenverhalten und Familienpolitik-West und ostdeutsche Frauen im Vergleich -Eine empirische Studie. In: Dienel C, editor. Abwanderung, Geburtenrückgang und regionale Entwicklung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag; 2005. pp. 217–230. [Google Scholar]

- Sackmann R, Jonda B, Reinhold M. Demographie als Herausforderung für den öffentlichen Sektor. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sandvik L, Erikssen G, Thaulow E. Long-term effects of smoking on physical fitness and lung function: A longitudinal study of 1393 middle aged Norwegian men for seven years. British Medical Journal. 1995;311:715–718. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7007.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk L. Migration und Gesundheit–Entwicklung eines Erklärungs- und Analysemodells für epidemiologische Studien. International Journal of Public Health. 2007;52:87–96. doi: 10.1007/s00038-007-6002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz A. Wandern und Wiederkommen? Humankapitalverlust und Rückkehrpotenzial für Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. In: Werz N, Nuthmann R, editors. Abwanderung und Migration in Mecklenburg und Vorpommern. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, A. (2009). Brain Drain aus Ostdeutschland? Ausmaß, Bestimmungsgründe und Folgen selektiver Abwanderung Forschungen zur deutschen Landeskunde (Vol. Band 258). Leipzig: Deutsche Akademie für Landeskunde, Selbstverlag.

- Siewert U, Fendrich K, Doblhammer-Reiter G, Scholz RD, Schuff-Werner P, Hoffmann W. Health care consequences of demographic changes in Mecklenburg-West Pomerania. Projected case numbers for age-related diseases up to the year 2020, Based on the study of health in pomerania (SHIP) Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 2010;107(18):328–334. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spallek J, Razum O. Gesundheit von Migranten: Defizite im Bereich der Prävention. Medizinische Klinik. 2007;102(6):451–456. doi: 10.1007/s00063-007-1058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian S, Huijts T, Avendano M. Self-reported health assessments in the 2002 World Health Survey: How do they correlate with education? Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2010;88:131–138. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.067058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turra CM, Elo IT. The impact of salmon bias on the hispanic mortality advantage: New evidence from social security data. Population Research and Policy Review. 2008;27(5):515–530. doi: 10.1007/s11113-008-9087-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. (1994). Preventing tobacco use among young people. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Georgia.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. (2004). The health consequences of smoking. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Georgia

- Verheij RA, van de Mheen HD, de Bakker DH, Groenewegen PP, Mackenbach JP. Urban-rural variations in health in the Netherlands: Does selective migration play a part? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1998;52:487–493. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.8.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, M., & Kulu, H. (2014). Low immigrant mortality in England and wales: A data artefact? Social Science and Medicine, 120, 100–109. Werz, N. (2001). Abwanderung aus den neuen Bundesländernvon 1989–2000. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, B, 39–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Walter U, Altgeld T, editors. Altern im ländlichen Raum. Ansätze für eine vorausschauende Alten- und Gesundheitspolitik: Campus Verlag, Frankfurt/Main; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zahlen und Fakten. (2014). Statistisches Bundesamt. Accessed Jan 08, 2014.

- Zeeb H, Razum O. Epidemiologische Studien in der Migrationsforschung. Ein einleitender Überblick. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz. 2006;49:845–852. doi: 10.1007/s00103-006-0017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]