Abstract

In this paper we compare several types of economic dependency ratios for a selection of European countries. These dependency ratios take into account not only the demographic structure of the population, but also the differences in age-specific economic behaviour such as labour market activity, income and consumption as well as age-specific public transfers. In selected simulations where we combine patterns of age-specific economic behaviour and transfers with population projections, we show that in all countries population ageing would lead to a pronounced increase in dependency ratios if present age-specific patterns were not to change. Our analysis of cross-country differences in economic dependency demonstrates that these differences are driven by both differences in age-specific economic behaviour and in the age composition of the populations. The choice of which dependency ratio to use in a specific policy context is determined by the nature of the question to be answered. The comparison of our various dependency ratios across countries gives insights into which strategies might be effective in mitigating the expected increase in economic dependency due to demographic change.

Keywords: Population ageing, National Transfer Accounts (NTA), Economic dependency ratio, Age-specific consumption, Age-specific labour income

Introduction

One of the most challenging developments in European societies is rapidly changing demographic structures. The age composition of the population is in many countries shaped by declining sizes of birth cohorts in the last 30–50 years. In the European Union, about 70 million persons will reach age 60 between 2020 and 2029, while only about 55 million will turn 20, about the average age at which young people enter the labour force.1 Without changes in economic activity this anticipated change in the demographic composition will result in a pronounced reduction of workers compared to elderly persons. This will in particular affect public sector funding: in most European countries the needs of inactive elderly persons are mainly provided and financed by the workers through public transfers, for example pensions, health care and long-term care. The situation is different in countries like the USA and Mexico where asset income is the most important source of elderly income (See, e.g. Mason (2013) for an overview including non-European countries). The expected changes in the age structure of the population require therefore accompanying adjustments in the economic behaviour of individuals and the design of the transfer system. Understanding the economic consequences of population ageing is of importance not only for policy makers, but also for society as a whole in order to understand the challenges posed by population ageing for the welfare state. Only with a realistic assessment of how demographic change affects the economy and the transfer systems, policy makers as well as individuals will be able to make appropriate economic decisions, in particular regarding retirement provision. Dependency ratios are commonly used as indicators of the sustainability of the public transfer system as the share of elderly increases. The rules for funding and access of public transfers are embodied in laws and structured rigidly around fixed age-borders which makes this system vulnerable to demographic change. In this paper we show that the way how dependency is defined plays a crucial role in how we measure and think about dependency. It also determines the lower and upper age limits in the life cycle where people switch from being dependent to independent and then again from independent to dependent, directly influencing the choice of policy responses.

A large part of any population is usually economically dependent in the sense that a part of its consumption is financed through transfers from other persons. The dependent population consists most notably of children and retired elderly persons. In Europe, the needs of children are mainly covered through transfers from the parents and the needs of elderly persons mainly through public transfers from the population which is active in the labour market. The relative size of these groups as well as the extent of the dependency determines the burden for the active population. An increase in economic dependency will require a more pronounced reallocation from workers to the dependent population if it is not counterbalanced by a change in economic behaviour.

Economic dependency ratios are a set of indicators which provide aggregate information on the degree of economic dependency in a given society. Contrary to demographic dependency ratios which are based on fixed threshold ages, economic dependency is derived by making use of the fact that the type and intensity of economic activity varies between individuals, in particular when they are of different age. Just as not everyone of working age is actually working, there are persons beyond the age of 65 that are still employed. The concept of the economic dependency ratio is closely related to the concept of the economic support ratio. While dependency ratios measure the number of persons relying on others, or the extent to which they rely on others, support ratios measure the capacity of the active population to provide for the dependent. We deliberately chose the economic dependency ratio, as compared to a support ratio, since our aim is to study to what extent more detailed measures of dependency can give a more refined picture than the widely used demographic dependency ratio.

Dependency ratios and support ratios are built up by defining functions and which assign a measure of dependency and the ability to support others to each individual i, dependent on the individual characteristics . Dependency ratios are calculated by summing up the dependency measure and the support measure (i.e. the values of the and functions) over the whole population of N individuals and by relating total dependency to total support.

| 1 |

Likewise, support ratios are calculated by relating the ability to support others to total dependency:

| 2 |

All dependency and support ratios can be described within this framework. In the case of demographic dependency, the function assigns a value of one to individuals below a certain age (usually 15 or 20) and above a certain age (usually 60 or 65), and zero otherwise. The function takes on the value of one if the age of individual i falls between those age boundaries and zero otherwise. The exact definition of the economic dependency measure and support measure depends on the purpose for which dependency and support ratios are built up. What all economic dependency and support measures have in common is that they take characteristics other than age into account. It has been argued by many others before that dependency measures based on chronological age alone are not a good way to capture populations actual dependency situation.

Age-specific economic characteristics, e.g. length of schooling, retirement age, employment and unemployment rates, the share of persons focusing on household tasks, consumption and saving , vary greatly between countries. In contrast to demographic dependency ratios, economic dependency ratios take these cross-country differences into account. The level of economic dependency depends on both individuals’ economic characteristics and the age structure of the population, in particular on the share of children and elderly persons in the total population. One of the most commonly used economic dependency ratios is based on the labour force status of individuals. This measure is for example used in the Ageing Report of the European Union European Commission (2014). For this measure, the dependency measure Dep(.) takes on the value of one for those who are not employed (e.g. unemployed persons, children, students, retirees) and zero otherwise. The support measure Sup(.) takes on the value of 1 for those who are employed and zero otherwise.

A refined approach for the specification of the dependent population has been taken in Cutler et al. (1990). In one of their suggested support ratios, they set the working age population weighted by their age-specific labour income in relation to the total population weighted by its age-specific consumption levels. This is clearly a refinement compared to the demographic dependency ratio that makes no distinction between different groups in the dependent population (e.g. between children and retirees) and within the working age population. Since Cutler et al. (1990) was published, a range of other suggestions on how to define economic dependency and the support capability have been put forward. For our paper of central relevance are the contributions of Andrew Mason and Ronald Lee in a range of articles introducing and applying National Transfer Accounts, e.g. Mason (2005), Lee et al. (2006), Mason et al. (2006) and Mason and Lee (2004). They suggest to use total consumption as the dependency measure and labour income as the measure for the ability to support others. We follow the general idea to derive what we call the NTA dependency ratio by relating the dependency of children and the elderly to total labour income. This dependency of children and the elderly is expressed as the age-specific difference between consumption and labour income. For this difference, the term life cycle deficit has been introduced because it is on average positive in childhood and youth as well as old age when average labour income falls short of average consumption and negative during working age. Lee and Mason (2013) argue that dependency on others can be reduced through the ownership of assets, designing the so-called general NTA support ratio when assets are included as a means to support consumption. Following this reasoning, we generate the general NTA dependency ratio by relating the total dependency of children and elderly to total income (i.e. labour and asset income).

Two recent papers that summarized the status quo and contributed further evidence to this argument are Spijker (2015) and Sanderson and Scherbov (2015). Whereas Spijker (2015) focuses on providing a comprehensive overview of existing indicators that have been created to overcome some of the shortcomings of having fixed cutoff ages for the definition of who is considered as dependent, Sanderson and Scherbov (2015) provide a history of dependency and support ratios and suggest a set of alternative indicators to measure dependency based on specific aspects such as health care and pension costs. An important consideration in this discussion is the notion that younger birth cohorts are overall healthier than older ones, which has crucial implications, for example their potential ability to work until later ages.

We will present results for four different economic dependency ratios: the first dependency ratio is based on a person’s economic activity status and relates the number of dependent persons to the number of workers; the second ratio relates the consumption of children and the elderly population which is not financed by their own labour income to total labour income; the third dependency ratio is similar to the second one and relates the total use of resources (consumption and saving) of children and the elderly population which is not financed by their own income to total income; and the fourth dependency measure focuses on the public sector and relates the amount of public net transfers received by children and elderly persons to the total amount of public transfers. We will illustrate in this paper that the level of economic dependency is to a large extent determined by the design of the economic life course, thus the age-specific type and intensity of economic activities. The economic dependency ratios which we analyse give information about the different mechanisms through which economic dependency ratios can be influenced. Such measures may include an increase in economic activity—in particular of women and among older age groups—and changes in income and consumption patterns. The analysis of cross-country differences using different types of economic dependency ratios helps to identify characteristics and institutions which shape economic dependency and thereby to gain insight into policies which help to dampen the expected increase in dependency because of population ageing.

We limit our analysis to the ten EU countries for which data from National Transfer Accounts (NTA) are available. These data consist of age-specific information on economic activities, in particular the generation of income, consumption and the value of transfers which are paid/received. In the following section we compare five dependency measures. We start with standard demographic dependency ratios for 2011 and 2050. These dependency ratios are based on the population structure alone, ignoring any other characteristics of a population, e.g. individual variation in economic behaviour. In order to incorporate this heterogeneity, we introduce a measure of economic dependency which explicitly considers differences by age and between men and women when it comes to economic activity. The most common economic dependency ratio relates the share of those that are not working to those that are working. We calculate such dependency ratios in Sect. 2.2, also decomposing them into several types of dependency according to the type of economic inactivity. The two economic dependency ratios calculated in Sect. 2.3 go one step further and additionally take different age-specific economic needs into account: the NTA-based dependency ratio relates the surplus of consumption over labour income of the dependent age groups to total labour income. Alternatively, we also present a general NTA dependency ratio in which we include asset-based reallocations (ABR) in addition to labour income. Consumption can also be financed through asset income and dissaving, which reduces the dependency of the elderly on transfers from younger age groups. In our application we define ABR as difference between asset income and savings. This measure represents the amount of resources that originate from asset income and saving and are available for consumption and transfers. Finally, the public sector dependency ratio introduced in Sect. 2.4 relates public net transfers to children and elderly persons to total contributions. These cross-country analyses provide detailed insight into which strategies are most promising in mitigating the expected increase in economic dependency. We compare the effect of selected strategies by creating scenarios for two of our four economic dependency measures and simulating dependency until 2050 in Sect. 3. Section 4 consists of a summary of our results and lists policy-relevant conclusions we draw from our analysis.

Dependency Measures

The Demographic Dependency Ratio

The most commonly used dependency ratios are the demographic young age and elderly dependency ratio. The young age dependency ratio relates the number of persons below the age of 20 to the number of persons aged 20–64, and the old age dependency ratio relates the number of persons aged 65+ to those aged 20–64. Adding up both ratios results in the total dependency ratio. The demographic young age, old age and total dependency ratios are compact measures for the age structure of a population. They get an economic interpretation by assuming that children and the elderly are dependent and persons between 20 and 64 are economically active. These measures have the serious drawback as they do not contain any information about actual economic behaviour of individuals, in particular the age of labour force entry and exit. Instead, they assume fixed age limits (age 20 and 65) and do not allow for variation across countries and within countries over time.

Table 1 shows the demographic dependency ratio in the European NTA countries that we selected for our study. The age structure of the population in these countries is quite different: Finland, France, Sweden and the UK are countries with a comparable large share of young people and a consequently high young age dependency ratio between 0.38 and 0.42. The share of persons below the age of 20 is rather low in Germany, Italy, Spain and Slovenia with a young age dependency ratio of 0.30 and 0.31. Germany and Italy are not only the countries with the lowest share of young persons, but also the countries with the highest old age dependency ratios of 0.34.

Table 1.

Demographic dependency ratios, 2011, 2030 and 2050

| Country | 2011 | 2030 | 2050 | Increase in total 2011–2030 (%) | Increase in total 2030–2050 (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young | Old | Total | Young | Old | Total | Young | Old | Total | |||

| AT | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.62 | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.75 | 0.35 | 0.51 | 0.86 | 21 | 14 |

| DE | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.65 | 0.32 | 0.51 | 0.83 | 0.34 | 0.62 | 0.96 | 28 | 16 |

| ES | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.59 | 0.29 | 0.43 | 0.72 | 0.36 | 0.68 | 1.04 | 24 | 43 |

| FI | 0.38 | 0.29 | 0.67 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.87 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.87 | 29 | 0 |

| FR | 0.42 | 0.29 | 0.71 | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.88 | 0.45 | 0.49 | 0.94 | 24 | 7 |

| HU | 0.33 | 0.27 | 0.69 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.70 | 0.36 | 0.52 | 0.88 | 18 | 26 |

| IT | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.65 | 0.32 | 0.44 | 0.76 | 0.35 | 0.58 | 0.93 | 17 | 22 |

| SE | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.71 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.83 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.84 | 16 | 1 |

| SI | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.56 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 0.80 | 0.39 | 0.59 | 0.97 | 44 | 22 |

| UK | 0.40 | 0.28 | 0.68 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.85 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0.92 | 25 | 9 |

| Average | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.64 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.80 | 0.39 | 0.54 | 0.92 | 25 | 16 |

AT Austria; DE Germany; ES Spain; FI Finland; FR France; HU Hungary; IT Italy; SE Sweden; SI Slovenia; UK

United Kingdom; Young young age dep. ratio (age 0–19)/(age 20–64), Old old age dep. ratio (age 65+)/(age 20–64), Total Young + Old

Source Eurostat, population on January 1st (2011); Eurostat, EUROPOP2013 (2030, 2050), main scenario

The demographic dependency ratios in 2030 and 2050 are calculated using the EUROPOP2013 population projections (for more details, see Sect. 3.1). The young age dependency ratio in 2050 is projected to be slightly higher than in 2011 in all ten countries, but it is in particular the old age dependency ratios that are expected to increase notably. The increase in the old age dependency ratio is projected to be most pronounced in Spain with an increase from 0.27 in 2011 to 0.68 in 2050. The increase is also expected to be high in Slovenia with an increase from 0.26 to 0.59. The projected increase in the old age dependency ratio is moderate in Sweden because of a balanced population structure and a relatively high fertility rate. It is also moderate in Finland, France and the UK due to the current and projected high fertility rates in these countries. These differences in countries’ current and projected population dynamics will entail non-uniform ageing experiences between 2011 and 2050: whereas the majority of countries will see larger increases in the first half of this period, Spain, Hungary and Italy will have a relatively larger increase in the second half (cf. last 2 columns in Table 1).

An Economic Dependency Measure Based on Employment

Our first measure of current economic dependency uses information on the activity status. This is in line with definitions of total economic dependency used in Vaupel and Loichinger (2006) and the EU Publications The 2015 Ageing Report and Demography, active ageing and pensions (European Commission 2012, 2014). Our calculations are based on age-specific estimates using data from EU-SILC for 2011.2 To identify working and non-working persons we use people’s self-defined economic activity status. The working, i.e. supporting, population is defined as those who report their economic status as working full-time or part-time, including those who carry out compulsory military or civil service. The non-working, i.e. dependent, population consists of inactive elderly persons, children, the unemployed, persons focusing on household tasks and other inactive persons. Persons below 16 are treated as students because there is no personal information for the population younger than 16 in the survey. We decompose the total dependency ratio into 5 sub-ratios dependent on the type of (in-)activity: a child dependency ratio, an unemployment dependency ratio, a domestic worker dependency ratio, a retirement dependency ratio as well as a ratio which includes other types of inactivity. By splitting up the data in this way we gain insight why the dependency ratios vary across countries. This employment-based economic dependency ratio EbDR is calculated as follows:

| 3 |

The dependency ratio is high in Spain, Hungary, Italy and Slovenia. In these four countries the unemployment dependency ratio is rather high compared to the other countries in Table 2. Italy, Hungary and Slovenia are also the countries with the highest retired dependency ratio. Spain does not have a particular high retired dependency ratio but a high share of unemployed persons in the population, which is not surprising, given that Spain was affected most by the financial crisis of all countries of our analysis. In Italy and Spain, a large share of persons states domestic work as their main activity. Looking at the distribution of economic dependency by age for Spain reveals that the share of housewives is increasing with age, which suggests that there is a strong cohort effect, given that the share of housewives is rather low among persons between ages 30 and 40. Sweden and the UK in return are the countries with the lowest dependency ratio since there is a low number of retirees compared to workers, a rather low share of unemployed persons, and only very few persons who indicate that their main economic activities are domestic tasks. The child dependency ratio is also low in the UK as the education system is compact and young persons enter the labour market at a comparably young age.

Table 2.

Employment-based dependency ratios by economic status, 2011

| Country | Total | In education | Unemployed | Retired | Domestic work | Other | Total (FT-equivalents) | Total (Stand. Pop.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | 1.28 | 0.48 | 0.09 | 0.59 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 1.29 | 1.35 |

| DE | 1.18 | 0.45 | 0.09 | 0.56 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 1.24 | 1.20 |

| ES | 1.66 | 0.58 | 0.29 | 0.61 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 1.66 | 1.83 |

| FI | 1.39 | 0.61 | 0.11 | 0.60 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 1.41 | 1.31 |

| FR | 1.42 | 0.63 | 0.11 | 0.61 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1.47 | 1.30 |

| HU | 1.60 | 0.60 | 0.18 | 0.71 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 1.59 | 1.67 |

| IT | 1.66 | 0.56 | 0.15 | 0.73 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 1.70 | 1.67 |

| SE | 1.10 | 0.53 | 0.06 | 0.46 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 1.30 | 1.00 |

| SI | 1.50 | 0.59 | 0.18 | 0.69 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.46 | 1.64 |

| UK | 1.11 | 0.50 | 0.06 | 0.46 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 1.19 | 1.07 |

FT-Equivalents full-time equivalents; Stand. Pop. using a standard population representing the average population structure of all 10 countries instead of country-specific populations

Source EU-SILC 2011 (Activity); Eurostat, population on January 1st (2011)

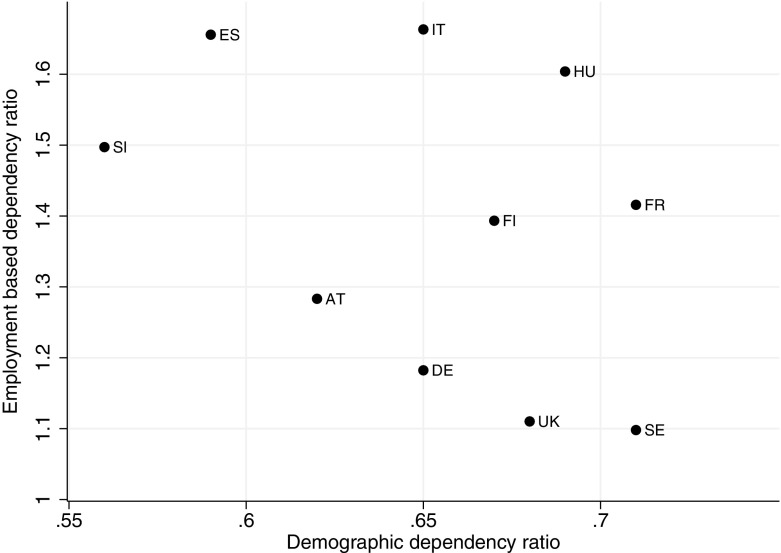

The UK and Sweden are the countries who have the lowest economic dependency ratios, and they are interestingly also the countries—besides Finland and France—that can expect the lowest relative increase in total demographic dependency between 2011 and 2050 (cf. column 8 in Table 1). Spain in turn is among the countries with the highest economic dependency ratio and is also the country where population ageing is most pronounced, reflected in the strong expected relative increase in the demographic dependency ratio. Although the relative position of the countries is rather stable over the years, they are affected by recent economic developments. In 2005 the dependency levels were much smaller for Spain, mainly due to a much lower unemployment rate (Table 8 in the Appendix). Figure 1 compares the ten EU countries that are part of this analysis directly in terms of their present levels of demographic and economic dependency. Countries that register relatively similar levels of demographic dependency, like Germany and Italy, can differ significantly when it comes to economic dependency. Furthermore, it seems there is even a negative correlation between demographic and employment-based economic dependency.

Table 8.

Employment-based dependency ratios by economic status, 2005

| Country | Total | In Education | Unemployed | Retired | Domestic work | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | 1.22 | 0.49 | 0.06 | 0.53 | 0.13 | 0.01 |

| DE | 1.13 | 0.45 | 0.09 | 0.51 | 0.07 | 0.01 |

| ES | 1.35 | 0.52 | 0.14 | 0.51 | 0.17 | 0.02 |

| FI | 1.22 | 0.57 | 0.11 | 0.49 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| FR | 1.40 | 0.65 | 0.11 | 0.56 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| HU | 1.32 | 0.55 | 0.13 | 0.61 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| IT | 1.63 | 0.55 | 0.13 | 0.70 | 0.21 | 0.05 |

| SE | 1.15 | 0.58 | 0.07 | 0.46 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| SI | 1.45 | 0.61 | 0.17 | 0.62 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| UK | 1.19 | 0.53 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.09 | 0.05 |

Source Activity status: EU-SILC 2005 (2006 for Germany); Population on January 1st 2005 (Eurostat)

Fig. 1.

Employment-based and demographic dependency ratios, 2011.

Source EUROSTAT; EU-SILC 2011 and Population 1st of January

What the economic dependency measures that are based on participation do not consider is the number of hours which are usually worked. Differences across countries in the share of persons who work part-time are thus not picked up. We try to take this into account by calculating the dependency ratios in full-time equivalents (column 8 in Table 2). As full-time equivalent we assume a weekly working time of 40 h. The information on working time is based on the reported number of hours which are usually worked per week. For most of the countries it makes not much of a difference in the total dependency ratio as the average weekly working time is around 40 h, the exceptions being Sweden and the UK. The dependency ratios for these two countries increase considerably, albeit from a very low level, since the usual weekly working time is reported to be much less than 40 h.

The economic dependency ratios presented so far are a combination of both age-specific distributions of activity and non-activity, and the respective population structure in each country. To control for demographic differences between countries, one approach is to apply the same population to all countries. As the standard population we choose the average population structure of the ten countries, ignoring differences in total population sizes but instead giving each country the same weight. Column 9 in Table 2 shows the total dependency ratio using this standard population. As total economic dependency based on the national population showed, Italy, Hungary, Slovenia and Spain are among the countries with the highest economic dependency ratio. The latter two countries are at the same time countries with an economically favourable demographic structure as a large part of their population is of working age. As the standard population contains relatively more older persons and children, total economic dependency for these countries is therefore even higher when the standard population is applied. The opposite is observed in the two countries with the lowest economic dependency ratio, UK and Sweden: by using the standard population their economic dependency ratios decrease. Still, even given these effects, the influence of the population structure on the country differences in economic dependency is rather low.

An Economic Dependency Measure Based on Income and Consumption: The NTA Dependency Ratio

The employment-based dependency ratio just presented above only takes the production side into account by counting the number of people in different stages of their life course. It ignores the extent of dependency within the dependent population, as well as the different capacity of workers to support others. National Transfer Accounts dependency ratios use the difference between average consumption and average production at each age as a measure of dependency. Thereby they take the age-specific differences in needs and productivity into account. While the employment-based dependency ratio is calculated using age-specific activity status, the NTA-based dependency ratio rests on age-specific averages of consumption and income.

NTA are a system of satellite accounts which break down the System of National Accounts (SNA) quantities by age and thereby introduce information on the relation between the age of individuals and their economic activities into the System of National Accounts framework. NTA measure how much income each age group generates through labour and through the ownership of capital, how income is redistributed across age groups through public and private transfers and how each age group uses its disposable resources for consumption. The dataset consists of an extensive number of age profiles containing the age-specific averages of labour income, consumption, public transfers, private transfers, asset income and saving. A detailed introduction to the methodology is given in UN (2013) and in Lee and Mason (2011). NTA data are available for the following European countries: Austria, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and the UK.3

The age-specific averages of labour income in our application have been estimated from EU-SILC 2011, referring to the year 2010 for all countries. The information on consumption is not available for the same year. We use the relative age profile of consumption from the NTA, referring to various years, adjusted to match the values from the SNA 2010.4 Details about data sources are provided in Table 9 in the Appendix. Consumption covers both private and public consumption of goods and services. Examples for public consumption that represents services provided by the government are public education and health care.

Table 9.

Overview: data sources

| Indicator and variables | Sources |

|---|---|

| Demographic dependency | |

| Population base year | EUROSTAT. Population 1st of January 2011. |

| Population projections | EUROSTAT, EUROPOP2013 |

| Employment-based dependency | |

| Activity status | EU-SILC. 2011 cross section, version from 01.03.2015. |

| 2005 cross section, version from 01.08.2009. | |

| Population | EUROSTAT. Population 1st of January 2011 and 2005. |

| NTA dependency | |

| Aggregate values | EUROSTAT. Non-financial sector accounts, ESA 95. |

| Derivation according to NTA methodology. | |

| Labour income | EU-SILC. 2011 cross section, version from 01.03.2015 |

| Consumption | Internal NTA database. |

| General NTA dependency | |

| Asset income, saving | Internal NTA database. |

| NTA public sector dependency | |

| Transfer inflows and outflows | Internal NTA database. |

| Internal NTA database | Access restricted. However, most of the profiles are publicly accessible on: |

| http://www.ntaccounts.org/web/nta/show/Country%20Summaries | |

| Base years for the profiles are as follows: Austria 2010, Finland 2004, | |

| France 2005, Germany 2003, Hungary 2005, Italy 2008, Slovenia 2004, | |

| Spain 2000, Sweden 2006, UK 2010. | |

NTA are based on an accounting identity which states that for each individual, and for each age group, the resources used for consumption (C) and saving (S) equal the disposable income composed of labour income (YL), asset income (YA) and net transfer inflows ()5:

| 4 |

A measure for average economic dependency at each age can be derived as the difference between consumption and production. This measure has been analysed by gender for several European countries in Hammer et al. (2015). Based on this age-specific dependency measure, the economic life course can be divided into three stages: childhood, working age and old age. Children and elderly persons are economically dependent as total labour income falls short of consumption. Working age is defined as those age groups for which average labour income exceeds average consumption. This qualitative pattern of the economic life cycle is similar in all countries. See Lee and Mason (2011) for an overview of countries around the world.

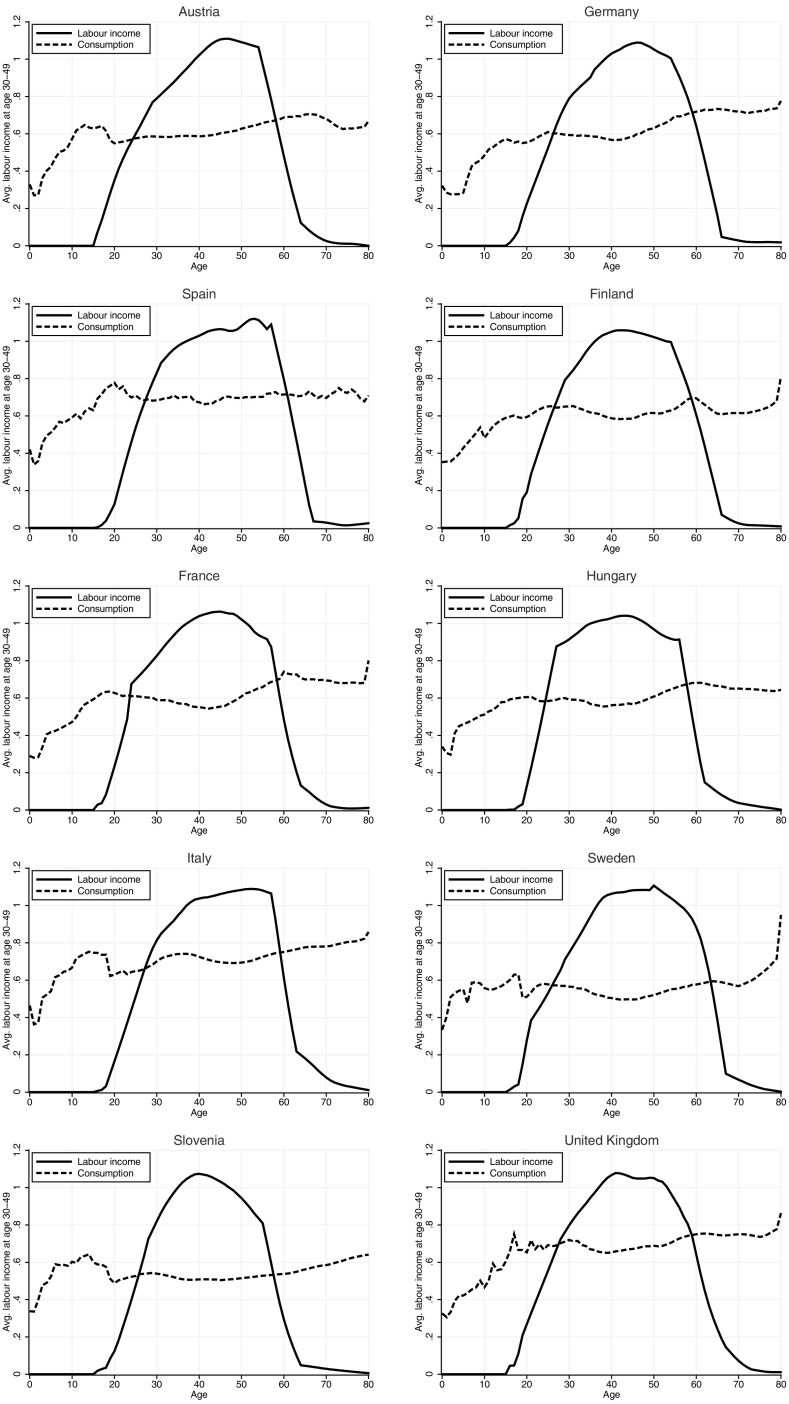

Figure 2 shows the age-specific estimates for labour income and consumption based on NTA results for 2010. To facilitate comparison across countries we depict the age profiles relative to average labour income in the age group 30–49 for each country. Compared to the employment rates presented in the “Appendix”, average labour income includes not only information on employment but also how the level of wages and labour income from self-employment varies across age.6 As with EbDR, the cross-country comparison again shows early entry into the labour market in Austria, work till high ages in Sweden and a ’narrow’ labour income age profile for Slovenia.

Fig. 2.

Per capita labour income, consumption and asset-based reallocations.

Source www.ntaccounts.org

The pattern of consumption is similar across countries. The consumption of young children is lower than that of adults because of the equivalence scale used for distributing most of the private consumption expenditures to household members: 0.4 for those age 4 and younger, 1.0 for adults age 20 and older, and a linear increase between age 4 and 20. Nevertheless, in most countries the consumption increases to the level of adults, or even higher, already during school ages because of the high (public) education expenditures. This is especially emphasized in Italy, Slovenia and France. The consumption of adults is rather stable across ages except in Germany and Hungary, where consumption increases to a higher level during their 50s. In Sweden there is a strong increase in consumption above age 70 due to the comprehensive but expensive system of long-term care (Bengtsson 2010). For all countries we observe a phase of dependency in young and old age (i.e. consumption exceeds labour income) and a period of surplus (labour income exceeds consumption) during the working ages. However, the shape of the specific age profiles of consumption, labour income and asset-based reallocations are different across countries reflecting country-specific institutional settings.

To obtain a measure for the dependency across individual ages in childhood and old age, respectively, the average measure of economic dependency at each age is multiplied with the corresponding population size and added up over those age groups where the difference between consumption and labour income is positive (also referred to as positive life cycle deficit). Two dependency ratios, and , can then be calculated by relating the total dependency of children and the elderly to total labour income. These measures represent the share of consumption of children and elderly which is not financed out of their own labour income in relation to total labour income. The NTA dependency ratios reflect both the population structure and the design of the economic life course, i.e. the involvement in production and consumption activities.

| 5 |

| 6 |

where the index L stands for the age where the life cycle deficit at young ages is still positive and similarly O stands for the lowest old age at which the life cycle turns positive again. These ages correspond to the ages where the lines for labour income and consumption cross in Fig. 2. The other variables are aggregate age-specific consumption and labour income .

Adding up and results in our measure of NTA-based total dependency, NtaDR:

| 7 |

However, in particular elderly persons finance part of their consumption through asset-based reallocation such as asset income and (dis-)saving. Individuals use intentionally accumulated assets for financing their consumption after they retire, especially in (partially) funded pension systems. Furthermore, according to the economic literature there are various motives for holding wealth at higher ages, including inter-vivo transfers and bequests. The usual way is that young people save first to receive asset income later in life. But obviously young persons also receive bequests from their ancestors, causing an inflow of asset income.7 Taking asset-based reallocations into account in addition to labour income introduces an additional interesting and important aspect to our dependency measure: the cross-country differences in age-specific asset accumulation result in a different degree of economic dependency and differences in the vulnerability of the welfare system regarding demographic change. Asset-based reallocations are also included in the NTA dataset for most of the countries.8 This is taken into account in the general NTA dependency ratio which includes labour income, asset income as well as consumption plus saving as a measure for the use of resources. We obtain the general dependency ratios by relating the difference between total use of resources and total income of children and elderly to total income. The total general NTA dependency, , is the sum of its two components and :

| 8 |

| 9 |

The results for the NTA dependency ratios are shown in Table 3.9 Italy is the country with the highest dependency in old age as it is the country with a rather high level of consumption relative to total labour income; it also is the country with the highest demographic dependency ratio. The old age NTA dependency ratio is also quite high in the UK. High levels of consumption relative to total income affect also the dependency of children: it is highest in Italy and the UK. In all of the analysed countries the elderly receive some income out of asset-based reallocations, the old age general dependency ratio is therefore lower as compared to the NTA dependency ratio considering only labour income. This is reflected in the difference in age-borders between NtaDR and in Table 3, where the introduction of ABR—which is an additional source of financing consumption—reduces the age spans with positive life cycle deficits. However, the difference between consumption and income remains large in all of these countries. In most of the analysed countries the pension system is generous enough for the elderly therefore they can finance their consumption without relying on assets.

Table 3.

NTA dependency ratio NtaDR and general NTA dependency ratio , for young age, old age and total population, 2010. Age-borders until and from which life cycle deficit is positive

| Country | NTA dependency ratio | Age-borders | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young age | Old age | Total | Positive until | Positive from | |

| Austria | 0.20 | 0.26 | 0.46 | 24 | 59 |

| Finland | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.52 | 26 | 59 |

| France | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.55 | 23 | 59 |

| Germany | 0.19 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 26 | 60 |

| Hungary | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.50 | 24 | 58 |

| Italy | 0.26 | 0.34 | 0.59 | 27 | 60 |

| Slovenia | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.48 | 25 | 58 |

| Spain | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.46 | 27 | 61 |

| Sweden | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.48 | 25 | 64 |

| United Kingdom | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.54 | 27 | 59 |

| Country | General NTA dependency ratio | Age-borders | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young age | Old age | Total | Positive until | Positive from | |

| Austria | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.31 | 22 | 60 |

| Finland | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.34 | 22 | 60 |

| Germany | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 25 | 65 |

| Italy | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.34 | 25 | 62 |

| Slovenia | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.37 | 25 | 59 |

| Sweden | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.34 | 24 | 64 |

Source EU-SILC 2011 (Labour income); www.ntaccounts.org (Consumption and ABR)

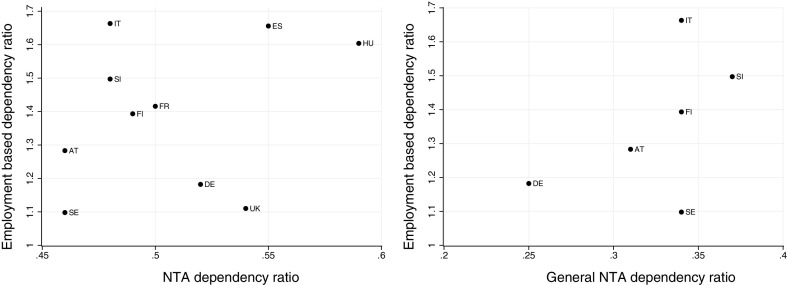

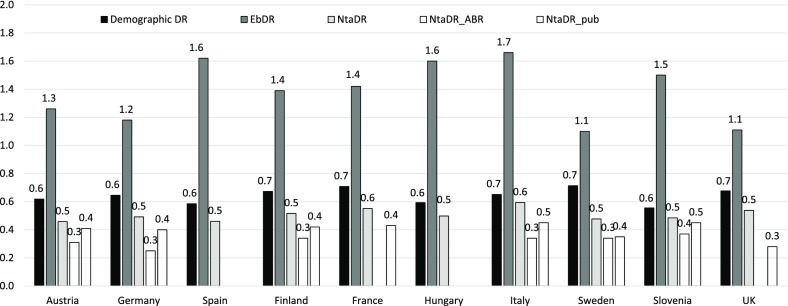

In Fig. 3 we compare the NTA and the general NTA dependency ratios directly with the employment-based dependency ratio EbDR. The fact that there is no clear correlation but that countries with very similar levels of NtaDR can have quite different levels of EbDR—e.g. Italy and the United Kingdom—and vice versa—e.g. Sweden and the United Kingdom—warrants the use of more than one measure for assessing economic dependency. While the EbDR measures economic dependency only in terms of person numbers, the NtaDR allows to quantify the extent of dependency. The former indicator may therefore be an important indicator for labour market policies, while the latter indicator may be applied when designing welfare programs.

Fig. 3.

Employment-based (EbDRs) and NTA-based (NtaDR, ) dependency ratios, 2010/2011.

Source EU-SILC 2011 (employment and labour income); www.ntaccounts.org (consumption)

The Public Sector Dependency Ratio

Dependency ratios are often used to illustrate the consequences of demographic changes on the funding of public transfers. However, these consequences depend on the degree to which demographic changes lead to a change of public transfer contributions and benefits. Children, for example, are economically dependent, but their needs are mainly financed through transfers from the parents. An increase in the number of children affects public transfer systems to a much smaller degree than an increase in the share of elderly persons. The dependency of the elderly varies considerably across countries and by age. Important determinants of the age-specific degree of dependency are the retirement age, the pension replacement rate and the organization of the health and long-term-care system. The dependency ratios introduced so far can be misleading when they are used to assess the consequences for the public sector. To adjust them for this purpose we introduce a public dependency ratio based on age-specific transfers from individuals to the public sector and the transfers from the public sector to individuals. The transfers to the public sector consist mainly of social contributions and taxes, and the transfers from the public to the private sector consist mainly of cash transfers such as pensions, unemployment benefits or long-term-care allowances as well as in-kind benefits in form of education, health services and other public consumption.

We define dependency as net transfers to children and elderly relative to total contributions, as shown in Eq. (10). refers to the public transfer benefits of age group i, to the transfer outflows to the public sector.10 For children up until age L the benefits exceed the contributions, as well as for elderly of age O and older. Note that the age-borders might differ from those for the NTA dependency. The sum of these (positive) net transfer benefits is then divided by the total contributions paid. This indicator can be interpreted as a measure of the extent to which the transfer systems redistribute to children and the elderly, respectively.

| 10 |

The results are shown in Table 4. The age-reallocation of resources through public transfers is strongest in Italy and Slovenia, where 45% of total contributions are reallocated to children and elderly. In these two countries the high values are driven mainly by a pronounced redistribution to the elderly. For Italy this can be explained by a rather low retirement age together with an old population, for Slovenia by the very low retirement age. The age-reallocation is lowest in the UK and Sweden. In the UK private pensions play a much more important role than in other European countries where elderly persons rely almost exclusively on public transfers. In Sweden, low levels of reallocation to the elderly are due to late retirement. While in most countries a person becomes a net receiver of public transfers around age 60, the corresponding age is 64 in Sweden. However, the public dependency ratios are also influenced by the extent to which the public sector saves/dissaves and pays/receives asset income. Sweden is the only country in our group with positive saving of the public sector. This reduces the ratio of inflows to outflows since part of the outflows is not directly returned to the population and does not show up as inflow.

Table 4.

Public sector dependency ratio , for young age, old age and total population. Age-borders until and from which benefits exceed contributions

| Country | Year | NTA public sector dependency ratio | Age-borders | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young age | Old age | Total | Pos. until | Pos. from | ||

| Austria | 2010 | 0.12 | 0.29 | 0.41 | 19 | 60 |

| Finland | 2004 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.42 | 21 | 59 |

| France | 2005 | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.43 | 21 | 60 |

| Germany | 2003 | 0.11 | 0.29 | 0.40 | 22 | 61 |

| Italy | 2008 | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0.45 | 21 | 60 |

| Slovenia | 2004 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.45 | 21 | 56 |

| Sweden | 2006 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.35 | 22 | 64 |

| United Kingdom | 2010 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.28 | 21 | 63 |

Hungary and Spain were excluded here because they use a different methodology for calculating public transfers

Source National Accounts database; www.ntaccounts.org

Projections of Dependency Ratios

So far, we only compared the five measures of dependency - demographic dependency, employment-based dependency, two dependency measures based on NTA data and one based on public sector transfers - for the present. In a next step, we are interested in simulating how some of these measures evolve during the next 40 years, based on Eurostat population projections and alternative scenarios for the development of age-specific economic behaviour. We will focus on the NTA dependency ratio and the employment-based dependency ratio. It is beyond the scope of this paper to project asset-based reallocations and public transfers. Asset income in a given year depends in a non-straightforward way on savings behaviour in the previous years. We also do not project public sector dependency ratios.

In case of the EbDR, we present results for three employment scenarios: in the first one, employment rates are kept constant at the present level (constant scenario). Under the assumptions of the second scenario, female employment increases significantly until 2050 (equalization scenario). In the third scenario, we gradually impose the age- and sex-specific employment pattern of Swedes on the population in all countries (benchmark scenario). The two scenarios for the NtaDR are closely related to the assumptions for the first and third scenarios of the EbDR simulations: in the first one, the currently observed age profiles of labour income and consumption are kept constant, whereas the second one is based on the assumption of convergence to the age profiles of Sweden. Additionally, we compare the results of the constant scenario with a further constant scenario for both ratios where we use a future standard population instead of country-specific population projections.

Population Projections

Eurostat regularly provides projections for all EU-28 member states, Iceland, Norway and Switzerland. The most recent projections, EUROPOP2013, have 2013 as their base year. In this scenario, also referred to as convergence scenario, total fertility (TFR) is assumed to converge to a value of 1.93 in all European countries by 2150. Similarly, life expectancy at birth is assumed to universally converge to 92.9 years for males and 96.3 years for females by 2150. Details can be found in Austria (2014). The values between 2013 and 2150 are interpolated. In the year 2050, the projection limit for this paper, convergence in assumptions will not be reached yet. In 2050, the assumptions for the TFR range from 1.51 in Spain and 1.58 in Italy to 1.92 in Sweden and 1.93 in the UK. Male life expectancy is assumed to be lowest in Hungary (80.1) and highest in Sweden (84.5). The respective values for women are 85.5 years in Hungary and 89.1 years in France and Spain.

In Table 5 we show the development of each country’s population between 2013 and 2050 by three broad age groups. The share of the population aged 20 to 64 is projected to decline in every country; however, in those countries with lower fertility, this decrease is more pronounced. In 2013, Germany and Italy were the only countries where the share of the population above age 65 was already above 20%. By 2050, this share is anticipated to increase to more than 30% in Germany and Spain, and up to 30% in Italy and Slovenia. In Finland, Sweden and the UK, the share of elderly is expected to be less than 25%.

Table 5.

Population distribution (in %) 10 European countries and for the standard population, by broad age groups, 2013 and 2050

| Country | Ages 0–19 | Ages 20–64 | Ages 65+ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2050 | 2013 | 2050 | 2013 | 2050 | |

| AT | 20.1 | 18.7 | 61.8 | 53.9 | 18.1 | 27.4 |

| DE | 18.1 | 17.1 | 61.2 | 51.0 | 20.7 | 31.8 |

| ES | 19.8 | 17.5 | 62.5 | 49.1 | 17.7 | 33.4 |

| FI | 22.3 | 21.9 | 58.9 | 53.4 | 18.8 | 24.7 |

| FR | 24.6 | 23.3 | 57.8 | 51.6 | 17.6 | 25.1 |

| HU | 20.2 | 19.2 | 62.7 | 53.2 | 17.2 | 27.5 |

| IT | 18.7 | 18.4 | 60.1 | 51.8 | 21.2 | 29.9 |

| SE | 22.8 | 23.2 | 58.1 | 54.3 | 19.1 | 22.5 |

| SI | 19.3 | 19.5 | 63.6 | 50.6 | 17.1 | 29.8 |

| UK | 23.7 | 22.9 | 59.1 | 53.2 | 17.2 | 23.9 |

| Standard | 21.2 | 20.4 | 60.6 | 52.3 | 18.2 | 27.4 |

Source Eurostat, EUROPOP2013, main scenario

Projections of Employment-Based Dependency

In order to project economic dependency based on employment, we need the future number of workers and non-workers in each country, since these two groups enter our formula for the employment-based dependency ratio EbDR (cf. Sect. 2.2).

The process to obtain the simulated number of workers involves two stages. First, we define and implement three scenarios of future employment, which means we create sets of age- and sex-specific employment rates for 2015 to 2050, in 5-year intervals. Employment rates for the starting year 2011 are calculated by dividing the number of people who are working by the total population, separately for men and women and for each 5-year age group. Everyone who reports their main activity status as working full- or part-time (including conscripts) is counted as being employed (cf. Sect. 2.2). Since EU-SILC starts collecting employment information for the population aged 16+, the youngest age group comprises persons aged 16–19. The last age group covers ages 70–74. The assumptions for the three employment scenarios are described in detail below. In a second step, these employment rates are multiplied by the respective population numbers from the EUROPOP2013 population projections (cf. Sect. 3.1). Summing up everyone who is employed results in the total number of workers, who enter the denominator of the EbDR formula. Since the numerator subsumes everybody who is not working, it is simply the residual when we subtract the total number of workers (i.e. everyone in the denominator) from the total population. It would be beyond the scope and the purpose of the present study to separately simulate the different categories of non-workers that are explicitly mentioned in the numerator in Eq. (3). Once we perform these calculations for every country, scenario and year from 2015 to 2050, in 5-year intervals, we can estimate the respective economic dependency ratios.

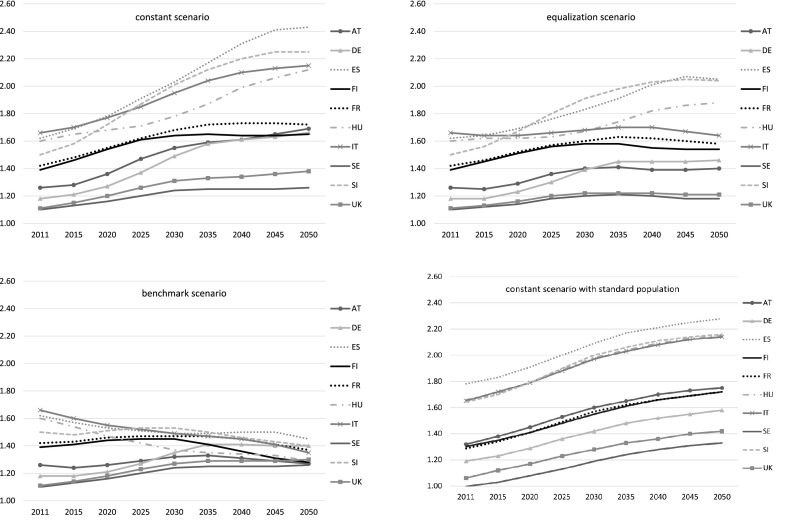

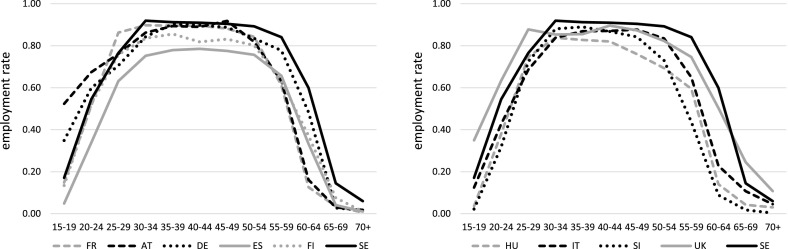

In the first employment scenario, the constant scenario, we keep age- and sex-specific employment rates constant at the level observed in 2011. Keeping employment levels unchanged means that any future change in economic dependency is solely driven by changes in the population structure. Since, as demonstrated above, the age composition in every country is shifting towards older ages, assuming no changes in economic activity leads inevitably to an increase in economic dependency. However, the level of the projected increase in this scenario varies significantly between countries (cf. column 4 in Table 6 and Fig. 4), given that countries show varying degrees of population ageing and different levels of employment, particularly of women and persons above the age of 50 (see Figs. 8 and 9 for country-specific employment profiles). The lowest increase is projected for Sweden and the United Kingdom, where high employment rates meet with a relatively favourable population structure. On the other hand, there are countries like Slovenia and Spain, where on average lower employment is combined with an above-average increase in the older population.

Table 6.

Economic dependency ratio, 2011, 2030 and 2050, by employment scenario

| Country | 2011 | Constant scenario | Equalization scenario | Benchmark scenario | Standard population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2030 | 2050 | 2030 | 2050 | 2030 | 2050 | 2030 | 2050 | ||

| AT | 1.26 | 1.55 | 1.69 | 1.40 | 1.40 | 1.32 | 1.27 | 1.60 | 1.75 |

| DE | 1.18 | 1.49 | 1.66 | 1.39 | 1.46 | 1.35 | 1.40 | 1.42 | 1.58 |

| ES | 1.62 | 2.03 | 2.43 | 1.83 | 2.05 | 1.49 | 1.45 | 2.09 | 2.28 |

| FI | 1.39 | 1.64 | 1.65 | 1.58 | 1.54 | 1.45 | 1.28 | 1.55 | 1.72 |

| FR | 1.42 | 1.68 | 1.72 | 1.60 | 1.58 | 1.47 | 1.37 | 1.57 | 1.72 |

| HU | 1.60 | 1.78 | 2.12 | 1.67 | 1.88 | 1.37 | 1.29 | 1.98 | 2.15 |

| IT | 1.66 | 1.95 | 2.15 | 1.68 | 1.64 | 1.49 | 1.35 | 1.97 | 2.14 |

| SE | 1.10 | 1.24 | 1.26 | 1.20 | 1.18 | 1.24 | 1.26 | 1.19 | 1.33 |

| SI | 1.50 | 2.01 | 2.25 | 1.91 | 2.04 | 1.53 | 1.40 | 2.00 | 2.16 |

| UK | 1.11 | 1.31 | 1.38 | 1.22 | 1.21 | 1.27 | 1.30 | 1.28 | 1.42 |

Source EU-SILC, 2011, own employment projections; Eurostat, EUROPOP2013 (2030, 2050), main scenario

Fig. 4.

Economic dependency ratios, 2011–2050, by country and scenario.

Source EU-SILC, 2011, own employment projections; Eurostat, EUROPOP2013 (2050), main scenario

Fig. 8.

Age-specific employment rates, men, 2011

Source EU-SIlC 2011 (based on self-defined activity status)

Fig. 9.

Age-specific employment rates, women, 2011

Source EU-SIlC 2011 (based on self-defined activity status)

Having said that, the constant scenario does not portray any likely development. It serves rather as a reference scenario that shows the unmitigated effect of anticipated changes in the population structure. In order to estimate what an increase in employment would mean for economic dependency, we calculate the equalization scenario. In every country, labour market activity of women is lower than that of men, and activating women is often a cited source of labour potential. At the same time, female employment has been on the rise in all 10 countries. The question is what level it will eventually attain. One conceivable development is that it will converge to the same or close to the same level as that of males. We demonstrate the effect of this assumption by allowing age-specific female employment rates in each country in 2050 to reach the respective employment levels of men that are observed in 2011. For the years in between, we interpolate linearly. In a way, this is a very strong assumption, since men and women do not have completely equal age-specific employment rates anywhere in Europe. At the same time, it is a conservative assumption in terms of overall employment, since it does not assume any changes in male employment at older ages at all and also older females will in this scenario not increase their employment in any way that goes beyond what is observed for men today. Assuming this increase in employment of women, economic dependency would increase to a significantly lower extent than under the constant scenario (cf. column 6 in Table 6 and Fig. 4). The largest relative impact is seen for Italy, where economic dependency would not increase between now and 2050 if Italian women were participating in the labour market as much as Italian men. Overall, the country-specific trajectories show noticeable differences, with some experiencing a continuous increase in dependency throughout the whole projection period and others levelling off around 2030 and 2035.

Given that not only female employment has been on the rise in all countries but that also an increase in economic activity of the population above age 50 can be expected due to past and ongoing changes in pension systems and labour laws, we create a third scenario where we change the employment rates of the whole population. In order to estimate what an increase in employment to overall higher levels—yet not beyond levels empirically presently observed—would mean for economic dependency, we calculated a benchmark scenario where we take a benchmark approach: of all the 10 countries we analyse, Sweden shows the highest levels of employment for men as well as women for the majority of age groups (cf. “Appendix”). What would achieving these same levels mean for economic dependency for the other 9 countries? In order to estimate this effect, we assume that current Swedish employment levels are obtained in every country in 2050 and project age- and sex-specific employment rates by linear interpolation for the years in between. The effect is overwhelming: economic dependency would actually decrease during the next four decades in six of the ten countries, namely Spain, Finland, France, Hungary, Italy and Slovenia (cf. column 8 in Table 6 and Fig. 4). In the four remaining countries (Austria, Germany, Sweden and the UK) dependency in 2050 would not increase beyond 1.4, which would still be below the ratio observed today in five out of the ten countries.

Just as we calculated economic dependency using a standard population in Sect. 2.2, it is possible to project dependency applying the same future population structure to all countries. This allows us to see in how far the results in each country are driven by differences in the age composition of the national populations. As before, in order to obtain a standardized population, we calculated the unweighted average of the projected populations for the 10 countries. We then combined this population with the employment rates from the constant scenario. Depending on whether a country’s population structure is older—as in Germany, Slovenia and Spain—or younger—as in Austria, the UK, Finland, and Sweden—than the average population, economic dependency using the standard population is lower or higher in 2050 than in the constant scenario where we use actual national population projections (cf. column 4 (constant scenario) and column 10 (standard population) in Table 6).

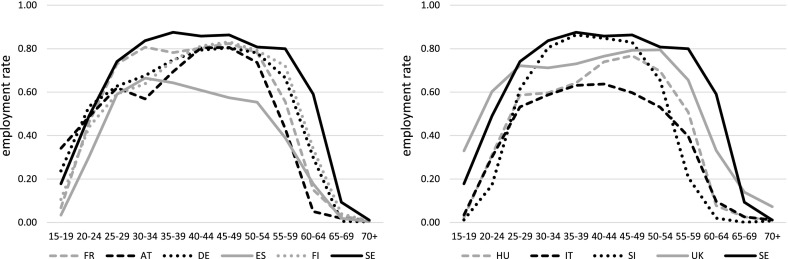

Projections of NTA Dependency

Similar to the constant and benchmark scenario in the previous section, we create two scenarios to demonstrate possible future developments of NtaDR, using different assumptions how the age profiles of C and YL will develop in the future:

In the first scenario we assume fixed consumption and labour income age profiles, as depicted in Fig. 2 (constant scenario). The results for each country are therefore driven by the changes in population’s age structure.

As the results of scenario 1 indicate, Sweden is the country that shows the most favourable development until 2050 in terms of the absolute level of the NtaDR. Therefore, in the second scenario, we assume linear transition from the actual age profiles of C and YL in individual countries to the respective age profiles of Sweden during the transition period 2010–2050 (benchmark scenario). The C and YL age profiles are normalized relative to average YL in age 30–49.

In both scenarios we apply the EUROPOP2013 population projections. The constant scenario in Fig. 5 presents the ratio of the life cycle deficit to total labour income for every country between 2010 and 2050. In all countries the ratio stays below 1 during the whole projection period indicating that the life cycle deficit of young and old individuals is smaller than aggregate labour income of prime age individuals.

Fig. 5.

NTA dependency ratios, 2010–2050, by country and scenario.

Source EU-SILC, 2011; www.ntaccounts.org, own NTA projections; Eurostat, EUROPOP2013 (2050), main scenario

There are big differences among countries already in 2010, and they become even larger during the projection period up to 2050 (cf. Table 7). Italy had the highest NtaDR in 2010, and it is projected to still be in the lead in 2050, followed closely by Slovenia. Between 2010 and 2030 France has a similar NtaDR trajectory as Italy, but thereafter the demographic pressure in France is expected to become lower than in Italy. On the other hand, under the current patterns of consumption and labour income Spain would face strong demographic pressure on dependency in the future—from about an average value of NtaDR of 0.46 in 2010 to 0.81 in 2050, which is the third highest among all ten analysed countries. The countries with projected high increases in NtaDR are also Germany and Hungary. Relative changes of the NtaDR during the projection period are more relevant than the absolute level of NtaDR. For example, Slovenia’s relatively low level of NtaDR in 2010 is mainly due to the high labour income relative to consumption, since there is not much asset income available for covering consumption. Thus, lower level of NtaDR does not necessarily mean better outlook for a country, it can be a consequence of low reliance on assets.

Table 7.

NTA dependency ratio, 2010, 2030 and 2050, by NTA scenario

| Country | 2010 | Constant scenario | Benchmark scenario | Standard population | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2030 | 2050 | 2030 | 2050 | 2030 | 2050 | ||

| AT | 0.46 | 0.59 | 0.66 | 0.53 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.70 |

| DE | 0.49 | 0.67 | 0.78 | 0.60 | 0.71 | 0.62 | 0.72 |

| ES | 0.46 | 0.60 | 0.81 | 0.54 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.73 |

| FI | 0.52 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.72 |

| FR | 0.55 | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.75 |

| HU | 0.50 | 0.58 | 0.74 | 0.51 | 0.61 | 0.67 | 0.75 |

| IT | 0.59 | 0.73 | 0.86 | 0.61 | 0.67 | 0.74 | 0.85 |

| SE | 0.48 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.54 | 0.65 |

| SI | 0.48 | 0.71 | 0.85 | 0.60 | 0.69 | 0.71 | 0.80 |

| UK | 0.54 | 0.66 | 0.72 | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.76 |

Source EU-SILC, 2011; www.ntaccounts.org; Eurostat, EUROPOP2013 (2030, 2050), main scenario

The benchmark scenario shows that gradual convergence from current C and YL age profiles of individual countries to C and YL age profiles of Sweden would—compared to the constant scenario – reduce the future demographic pressure on economic dependency in every country (see Fig. 5). In Spain the increase in dependency is still large; Italy, on the other hand, which had the highest dependency level in 2050 under the constant scenario, would benefit greatly from this change in consumption and labour income profiles.

The picture changes again when we apply a standard population instead of the country-specific population projections, again calculated as the unweighted average of projected populations for all 10 countries. In this scenario the differences among countries are driven only by their respective age profiles of labour income and consumption but not by different populations. When using the standard population, Germany, Spain and Slovenia would face noticeably lower increases in the NTA dependency ratio compared to the constant scenario (see Fig. 5). This means that in the constant scenario for those three countries population ageing plays a larger role in explaining the high increase in NtaDR during the projection period than for the other countries.

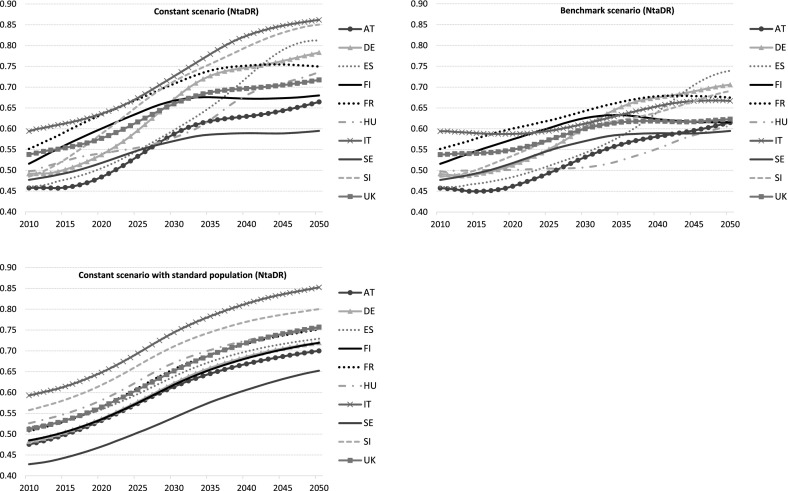

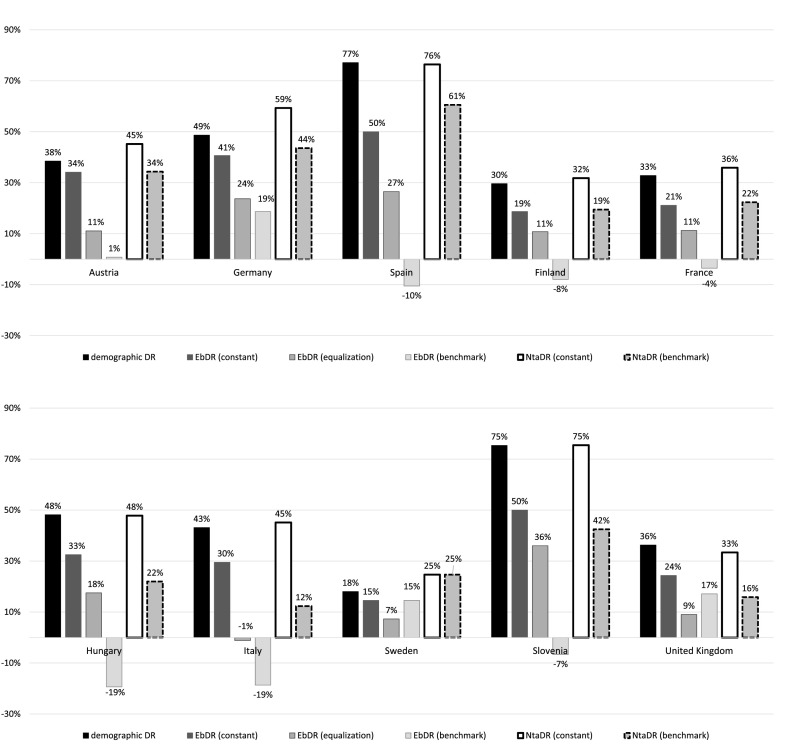

Figure 6 combines the projection results of three dependency measures and shows the relative changes in dependency ratios between 2011 and 2050. What has to be kept in mind when interpreting the height of the bars in Fig. 6 is that they show country-specific relative changes, which means nothing can be deducted about the absolute levels of dependency. Hence, the fact that Spain and Slovenia show by far the largest increase in demographic dependency is partly due to them being the two countries with the lowest dependency in 2011 (cf. Fig. 7). Similarly, the result that Germany, Sweden and the UK do not experience a decrease below 2011 levels by 2050 in any of the scenarios of the EbDR is to a large extent due to them being the countries with the lowest levels of economic dependency to begin with in 2011. This can partly be explained by their employment levels of women and/or among persons 50+ which are already today higher than in the other seven countries, meaning that the latter have more leverage when it comes to increasing employment in the future. The extent to which it is possible to further increase female labour force participation without negatively affecting fertility depends strongly on the design of the transfers to children, in particular the education system and the distribution of childcare tasks between the state, the core family and the extended family. As Hammer et al. (2015) indicate, the high female participation rates in Sweden and Slovenia might be only possible through the high provision and use of public child care institutions, and in the case of Slovenia, through a high involvement of the extended family (grandparents). Hence, a pronounced increase in female participation rates would in most countries only be possible if it was accompanied by a reconstruction of the child care and education system.

Fig. 6.

Relative change in demographic and economic dependency ratios between 2010/2011 and 2050, by scenario.

Source EUROSTAT (population data); EU-SILC 2011 (EbDR); EU-SILC 2011, www.ntaccounts.org (NtaDR)

Fig. 7.

Demographic, employment-based, and NTA-based dependency ratios, 2010/2011.

Source EUROSTAT (population data); EU-SILC 2011 (EbDR); EU-SILC 2011, www.ntaccounts.org (NtaDR, , DRpub)

Conclusion

There is a lot of variation between people of different ages regarding production and consumption, saving and transfers. We compared five measures of dependency for a selection of ten European countries. One of the measures is purely demographic, whereas the other four measures include information on individuals’ characteristics related to economic activity. One of the measures for the economic dependency makes use of data on labour market participation, and two of them use data on income, consumption and asset-based reallocations (ABR). The fifth measure is based on age-specific estimates of public sector transfers. We demonstrate that the level of dependency varies significantly between the five indicators. We also show through simple simulations how changes in economic behaviour—changing economic activity or labour income and consumption patterns—affect projected levels of economic dependency. These simulations are based on a strict shift-share approach in which we focus on changes in the population structure and age-specific profiles of economic activities. A main caveat with this approach is that available cross-sectional data are taken at face value and that age-, period- and cohort-effects are not treated separately. However, since the goal was not to accurately forecast future employment, consumption or income patterns, but to illustrate the effect of demographic changes as well as constant and changing age profiles of economic behaviour, this approach seemed to be warranted (Prskawetz and Sambt 2014; Sanderson and Scherbov 2015).

Economic dependency ratios are much better suited as information base for adapting public policies and individual strategies to deal with population ageing than ratios purely based on demographic information. Each of the presented indicators has its merits and short-comings and sheds light on a different aspect of dependency. Dependency measures based on employment show the potential to increase employment levels among the working age population, for example by postponement of retirement or better integration of women in the labour market, which often hinges on the reconciliation of work and care responsibilities. Since contributions to social security systems are in large part taken out of people’s paychecks, the dependency ratio based on employment can be seen as a proxy for the average number of non-contributing persons per contributor. The NTA dependency ratio goes one step further and captures differences in the needs of the elderly as well as the ability of the working age population to provide for them by relating the consumption of children and elderly persons to total labour income in an economy. It is a measure for the overall age-reallocation required in the economy, either through ABR, private transfer or public transfers. Still, the interpretation as dependency ratio is not fully correct as parts of the needs in old age are covered by ABR. The general NTA dependency ratio takes this aspect into account. However, we do not know whether the current level of ABR could be used for financing consumption also in the future. Finally, we introduced a dependency ratio that represents the share of total public contributions (e.g. taxes) that are being reallocated to children and the elderly. Since it is possible to split this ratio and to separately analyse the share of this reallocation that goes to children and the elderly, effects of redistributive policies and of changes in population structure can be picked up with this ratio.

The absolute values of dependency compiled in Fig. 7 for the year 2011 have related yet different interpretations. A demographic dependency ratio larger than one means that there is more than one young (less than 20 years) or older (65 years or older) person for each person of working age. In no country has demographic dependency reached this level yet. When it comes to economic dependency, on the other hand, one of our indicators—EbDR—consistently shows values larger than one in all 10 countries. A ratio larger than one implies that there are more non-employed than employed persons in a given society. It is hard if not impossible to say what level of dependency, for any of our presented indicators, becomes unsustainable in the long run. What can be said though is that increasing levels of economic dependency requires an adjustment of institutions, in particular public transfers, and that the speed of the increase in dependency matters. Furthermore, the difference between consumption and labour income in the future could be financed through public and private transfers and ABR, as shown in the general NTA dependency ratio . The existence and availability of ABR relieves some pressure from transfer systems.

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Commission’s Seventh Framework Programme FP7/2007–2013 under grant agreement No. 290647. It has also been supported by funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development and demonstration under grant agreement No. 613247. This paper uses data from the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC; cross-sectional EU-SILC UDB—version from August 01, 2013). We herewith acknowledge data provision for EU-SILC by EUROSTAT and the European Commission, respectively. Presented results and drawn conclusions are those of the authors and not those of EUROSTAT, the European Commission or any of the national authorities whose data have been used.

Appendix: Employment Patterns by Age and Sex

Footnotes

Source EUROPOP 2013, main scenario.

In order to be consistent, we chose EU-SILC as data source for economic activity since this is also our data source for labour income (cf. Table 9).

For detailed description of the NTA results for Finland, Germany, Hungary, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden see Lee and Mason (2011). For the Italian data see Zannella (2013) and for Austria see Hammer (2014).

The use of consumption age profiles from different years should not affect our results much. The historical NTA data show that the shape of the age profiles changes only slowly with time, see, e.g. Hammer (2014) for Austria from 1995 to 2010. Furthermore, consumption of adults is rather constant over the whole adult age range.

Transfer inflows and outflows are recorded from the individuals point of view: inflows constitute the benefits, outflows the contributions to the transfer systems. Public transfer inflows consist, for example, of benefits such as pensions, health services or child benefits while the public transfer outflows consist mainly of taxes and social contributions.

Labour income from self-employment comprises part of mixed income (income of non-incorporated firms). In NTA 2/3 of mixed income is allocated to labour and 1/3 to capital income.

NTA capture only current transfers. Capital transfers such as bequests are not directly captured, but through the income which they generate for their owners.

Age-specific asset-based reallocations are not available for France and Hungary. The definition of NTA flows excludes capital transfers; however, in the case of the UK, bequests have been included as transfers. This difference in the methodology affects the comparability of the savings variable, as its estimation relies on income, consumption and transfer estimates. In the case of Spain, public transfers have been defined in a non-comparable way, which again affects the estimates of age-specific savings. We therefore do not include these four countries in our comparison of the general dependency ratio.

We calculated the NTA dependency ratio and the NTA general dependency ratio also for the year 2005. The results are very similar, and in particular the relative position of the countries does not change. We conclude that these indicators are robust regarding changes in the macro-economic environment.

TGI is the abbreviation for Transfers Government Inflows, TGO for Transfers Government Outflows.

References

- Bengtsson, T. (Ed.). (2010). Population ageing—a threat to the welfare state? The case of Sweden. Springer.

- Cutler DM, Poterba JM, Sheiner LM, Summers LH. An aging society: Opportunity or challenge? Brooking Papers on Economic Activity. 1990;21(1):1–74. doi: 10.2307/2534525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. (2012). Demography, active ageing and pensions. Social Europe guide, 3.

- European Commission. (2014). The 2015 ageing report: Underlying assumptions and projection methodologies. European Economy, 8.

- Hammer, B. (2014). The economic life course: An examination using national transfer accounts. Ph.D. thesis, Vienna University of Technology.

- Hammer B, Prskawetz A, Freund I. Production activities and economic dependency by age and gender in Europe: A cross-country comparison. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing. 2015;5:86–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jeoa.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R., Lee, S.-H., & Mason, A. (2006). Charting the economic life cycle. NBER Working Paper No. 12379.

- Lee, R., & Mason, A. (2013). Reformulating the support ratio to reflect asset income and transfers. In Extended abstract for the Annual meeting of the Population Association of America. New Orleans, LA, 11–13 April 2013.

- Lee, R. D., & Mason, A. (Eds). (2011). Population aging and the generational economy: A global perspective. Edward Elgar Pub.

- Mason, A. (2005). Demographic transition and demographic dividends in developed and developing countries. In United Nations Expert Group meeting on social and economic implications of changing population age structures. Mexico City, 31 August–2 September 2005.

- Mason, A. (2013). Reformulating the support ratio to reflect asset income and transfers. In Paper presented at the PAA 2013 Annual Meeting. New Orleans, LA, 11–13 April 2013.

- Mason, A., Lee, R., Tung, A.-C., Lai, M.-S., & Miller, T. (2006). Population aging and intergenerational transfers: Introducing age into national accounts. NBER Working Paper No. 12770.

- Mason, A., & Lee, R. D. (2004). Reform and support systems for the elderly in developing countries: Capturing the second demographic dividend. In Paper prepared for the “International Seminar on the Demographic Window and Health Aging: Socioeconomic Challenges and Opportunities” at the China Centre for Economic Research. Peking University, Beijing, 10–11 May 2004.

- Prskawetz A, Sambt J. Economic support ratios and the demographic dividend in Europe. Demographic Research. 2014;30(34):963–1010. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2014.30.34. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson WC, Scherbov S. Are we overly dependent on conventional dependency ratios? Population and Development Review. 2015;41(4):687–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00091.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spijker, J. (2015). Alternative indicators of population ageing: An inventory. Vienna Institute of Demography Working Papers 4/2015.

- Austria, S. (2014). Vergleich der Bevoelkerungsprognosen von Eurostat und Statistik Austria. Presentation zur 7. Sitzung der Kommission zur langfristigen Pensionssicherung. 22. April 2014. Statistik Austria.

- UN., (2013). National transfer accounts manual: Measuring and analysing the generational economy. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: United Nations.

- Vaupel JW, Loichinger E. Redistributing work in aging Europe. Science. 2006;312:1911–1913. doi: 10.1126/science.1127487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zannella, M. (2013). Economic life cycle and intergenerational transfers in Italy. The gendered dimension of production and the value of unpaid domestic time. Ph.D. thesis, Sapienza Università di Roma.