Abstract

Background

Seasickness and travel sickness are classic types of motion illness. Modern simulation systems and virtual reality representations can also induce comparable symptoms. Such manifestations can be alleviated or prevented by various measures.

Methods

This review is based on pertinent publications retrieved by a PubMed search, with special attention to clinical trials and review articles.

Results

Individuals vary in their susceptibility to autonomic symptoms, ranging from fatigue to massive vomiting, induced by passive movement at relatively low frequencies (0.2 to 0.4 Hz) in situations without any visual reference to the horizontal plane. Younger persons and women are considered more susceptible, and twin studies have revealed a genetic component as well. The various types of motion sickness are adequately explained by the intersensory conflict model, incorporating the vestibular, visual, and proprioceptive systems and extended to include consideration of postural instability and asymmetry of the otolith organs. Scopolamine and H1-antihistamines, such as dimenhydrinate and cinnarizine, can be used as pharmacotherapy. The symptoms can also be alleviated by habituation through long exposure or by the diminution of vestibular stimuli.

Conclusion

The various types of motion sickness can be treated with general measures to lessen the intersensory conflict, behavioral changes, and drugs.

The term “motion sickness” (also called “kinetosis”) describes a set of symptoms that occur in association with motion of a person or his or her surroundings, triggering a stress reaction that results in autonomic symptoms. The onset is often insidious, with drowsiness/yawning and reduced alertness, and symptoms progress through cold sweating and pallor, salivation, and occasionally headache, to nausea and vomiting with incapacitation that can be severe (1).

Once the triggering motion ceases, symptoms generally disappear completely within 24 hours.

Learning goals

After reading this article, the reader should:

Be familiar with the wide array of motion types and patterns that can trigger motion sickness.

Understand the widely accepted model of the pathogenesis of motion sickness—the sensory conflict model and its extensions.

Be able to diagnose motion sickness.

Be familiar with drug and non-drug treatments and know when each is appropriate.

Introduction

Motion or travel sickness is as old as the various types of motion that cause it, whether on land, in the air, or at sea; sea sickness is the most notorious and in the extreme case can affect as many as 60% of even an experienced crew (2). In any vehicle or ship, it is generally persons being passively transported who are affected most—a fact well explained by the sensory conflict model presented below.

Definition.

The term “motion sickness” describes a set of autonomic symptoms caused by incongruent sensory impressions under conditions of motion. Cold sweats, pallor, nausea, and vomiting are caused by a stress reaction to the motion.

In days of old, those affected were mainly professional seafarers, a few of whom were unable to adapt adequately. Today, however, we see increasing numbers of temporary “seafarers,” not just on cruise ships, but also, for example, in the offshore wind industry, where it is necessary for “landlubber” engineers and technicians to be transported out to the wind parks in small boats. Modern transportation is also producing an increasing number of other trigger situations that are becoming relevant, from motion sickness in the back seat of a car, in a tilting train or an aircraft, to the “space sickness” experienced by astronauts in conditions of weightlessness.

It would appear that about two thirds of travelers have experienced symptoms of motion sickness at least once in a car, especially when in the back seat; half of them have even vomited, which among other things could have implications for the development of self-driving cars (3). In regard to the risk of becoming seasick on board a ship, and as an aid for shipbuilding design to help mitigate it, an ISO standard (IDO 2631) has even been defined, together with principles for the calculation of “motion sickness incidence” (MSI) that make it easier to estimate the expected percentage of persons who will vomit within 2 hours in given sea conditions (4).

And then there is the new phenomenon of “simulator sickness,” where playing complex video games on large screens or using virtual reality (VR) headsets can lead to symptoms surprisingly similar to those of classic seasickness, even though the persons affected are not physically in motion. As early as 1994, in a study of 146 volunteers, 61% of probands developed symptoms of malaise during a 20-min VR immersion period (5).

Young people, especially children between the ages of 6 and 12 years, and women are believed to be more susceptible to motion sickness (6– 9, e1), meaning that symptoms induced by computer simulations are particularly significant for this group.

Whatever the scenario that leads to motion sickness, it is nevertheless often necessary for the person affected to carry out active control tasks in fast-moving scenarios and/or on screen. Examples are the driver who has to intervene in a self-driving car, the drone pilot in a complex situation, or the operator of a virtual reality operation system. To ensure that such control tasks are carried out safely, critical issues are whether and when any relevant reductions in alertness and competence occur, and whether these are noticed at all before the symptoms of nausea obtrude.

Early symptoms of incipient motion sickness with reduced alertness are also called “sopite syndrome” (from the Latin sopire, “to lull, to put to sleep”). The term describes a condition of withdrawal with increasing apathy and lethargy (e2), which the person affected may not even notice him- or herself. Few scientific publications exist on sopite syndrome. At the present time, PubMed shows only 16 publications on this subject.

Prevalence.

Young people, especially children between the ages of 6 and 12 years, and women are believed to be more susceptible to motion sickness.

Many people habituate well to kinetogenic situations that at first cause them malaise. However, other affected persons can be unable to habituate adequately. For example, twins often react very similarly, as shown by a 2006 study of monozygotic and dizygotic twins, suggesting the existence of a genetic background (10).

What, now, do the various situations from seasickness to “simulator sickness” have in common, such that predisposed persons can develop a complex of symptoms that range from reduced alertness to discomfort to feeling violently ill with severe vomiting?

This article will first present pathophysiological models of the causes of motion sickness. Next, neurophysiological aspects of nausea and vomiting in motion sickness will be discussed. The complexity of the neurophysiology involved explains why there are so many different approaches to treatment, including habituation exercises and more unconventional methods in addition to medication.

For the presentation of the pathophysiology of the various forms of motion sickness, a selective literature search on PubMed was carried out for the purpose of determining the extent of consensus on the dominant conflict theory model on the basis of the number of high-quality publications (human studies, clinical trials, reviews) found, and also on particular aspects that extend or supplement the model (ebox).

eBOX. Literature search on particular aspects of the pathophysiology of various forms of motion sickness.

Literature search of the PubMed database for review articles or clinical studies in humans on the pathyphysiology of various forms of motion sickness: Filters: humans, clinical trial, review

-

Motion sickness

Search terms for motion sickness: (motion sickness, sea sickness, simulator sickness, kinetosis)

Search strategy: (((motion sickness) OR (sea sickness) OR (simulator sickness) OR kinetosis)

-

Conflict theory

-

Results for literature reviews or clinical trials in which the conflict theory was discussed as the central theory of motion sickness:

43 articles (human studies; clinical trials or reviews)

Search terms for conflict theory: sensory conflict, sensory mismatch

Search strategy: (((((motion sickness) OR sea sickness) OR simulator sickness) OR kinetosis) AND (sensory conflict) OR sensory mismatch)

Filters: humans, clinical trial, review

-

-

Postural instability

-

Results for literature reviews or clinical studies in which the effects of postural instability on the occurrence/severity of motion sickness are discussed:

12 articles (human studies; clinical trials or reviews)

Search terms for postural instability: postural instability

Search strategy: ((((postural instability) AND ((((sea sickness) OR motion sickness) OR simulator sickness) OR kinetosis)

Filters: humans, clinical trial, review

-

-

Otolith asymmetry

-

Results for publications in which the role of otolith asymmetry in relation to the occurrence/severity of motion sickness, especially space sickness, is discussed:

13 articles (human studies), no further filtering

Search terms for otolith asymmetry: otolith asymmetry

Search strategy: (((((otolith asymmetry) AND ((((sea sickness) OR motion sickness) OR simulator sickness) OR kinetosis)

Filter: Humans

-

Explanatory models of motion sickness

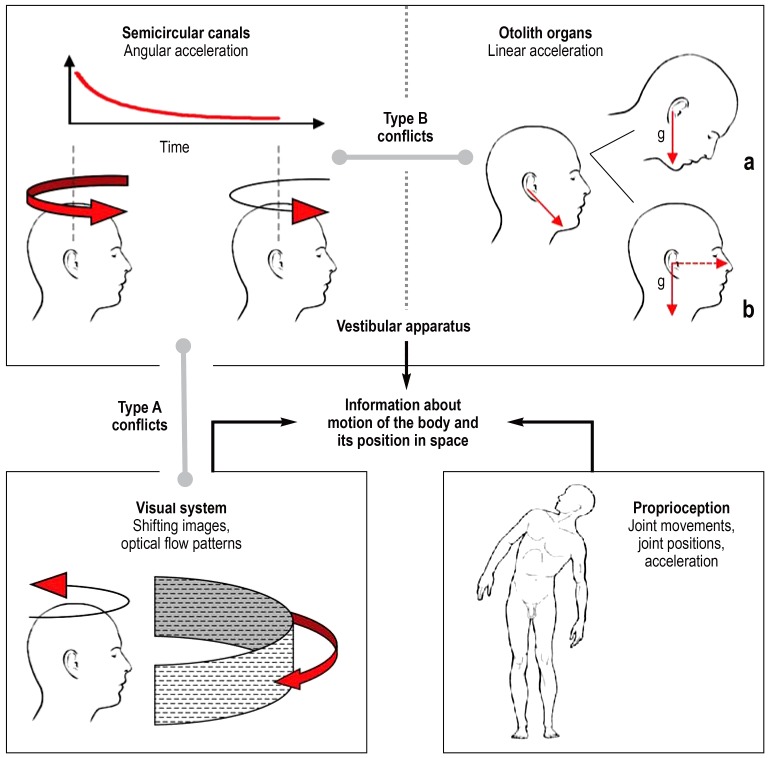

Vestibular, somatosensory, and visual afferents (efigure) provide information about body posture and body movements (e3). The three semicircular canals of the vestibular apparatus are stimulated by angular acceleration, while the otolith organs of the vestibular apparatus (saccule and utricle) are stimulated by linear acceleration (including the acceleration of the Earth), because the otolithic membranes are weighed down by a layer of calcium carbonate crystals embedded within them (e3). The position of the head relative to the torso is reported by proprioceptive afferents from the neck muscles and the vertebral column. Visual inputs provide information on the body‘s own motion and/or that of its environment. Proprioceptive afferents from the joints and skeletal musculature transmit the sense of joints movements, joint position, and acceleration. Normally the three sensory channels (vestibular, visual, and proprioceptive) complement each other without contradiction. The afferents are connected to motor centers in the brainstem, which stabilize body position, e.g., through the use of stabilization reactions.

eFigure.

Sensory conflict. Vestibular, visual, and proprioceptive afferents provide complementary information about the motion and position of the body in space. Normally this information is congruent—it matches. In type A conflicts, visual and vestibular afferents contradict each other. In type B conflicts, signals from the semicircular canals and otolith organs of the vestibular apparatus are incongruent or ambiguous.

Unless the inputs from multiple sensory organs can be integrated, the information they provide remains incomplete. On its own, the visual system cannot reliably distinguish between motion of the body and motion of the environment (e.g., perception of vection [self motion] experienced by an observer in a stationary train when another train pulls in alongside). The semicircular canals register angular acceleration of the head, but their signal decays over the course of a long, smooth turn. The otolith organs register the size and direction of linear acceleration, including that of gravity (g↓). Because the same direction of acceleration can result from (a) an inclination of the head or (b) a combination of horizontal and vertical accelerations, the signals from the otolith organs need to be supplemented by the other afferents.

Illustration adapted from Bertolini G, Straumann D: Moving in a moving world: A review on vestibular motion sickness. Front Neurol 2016; 7: 14.

Genetic component.

Twins often react very similarly, as shown by a 2006 study of monozygotic and dizygotic twins, suggesting the existence of a genetic background.

Sensory conflicts are the most current explanation of motion sickness (11– 16). These conflicts arise when information from different sensory channels is contradictory or disagrees with expectations (efigure). Two categories, each with three conflict types, are described in Table 1 (13, 16). Category A contains conflicts between visual and vestibular information. When both sensory systems report motion, but the reports disagree temporospatially, this is a type A1 conflict. An example would be watching the waves from the deck of a lurching ship. With a type A2 conflict, the visual system is reporting motion but the vestibular system is not. Because in this case the body is actually not in motion, this form is also referred to as “pseudo motion sickness” (13). An example is the already mentioned “simulator sickness” experienced by an observer in a stationary travel simulator watching scenes of traveling around a curve (e4). In type A3 conflict, the vestibular system reports motion but the visual system does not. Examples are reading below deck in a swaying ship, or being a back-seat passenger during a bumpy car ride.

Explanatory model.

The sensory conflict model is widely accepted as explaining the pathogenesis of motion sickness. Incongruent sensory information results in conflict between the vestibular, optic, and proprioceptive systems.

Category B sensory conflicts (eFigure, Table 1) are those caused by incongruent afferent information of the vestibular apparatus. These, then, are sensory conflicts between the five sensors (three semicircular canals, two otolith organs) that are active in the two labyrinths and show some frequency specificity. Slow passive motion, with a period between 0.1 and 0.5 Hz, is more likely to lead to nausea and vomiting than oscillating motion at a higher frequency (11). Studies of probands have shown that linear accelerations in vertical and horizontal directions (raising and lowering or laterally translating a closed cabin) with a varying cycle around 0.2 Hz had a particularly kinetogenic effect (17, e5, e6). The signals from the vestibular apparatus during motion of this periodicity are ambiguous (conflict type B), so that translation is sometimes incorrectly interpreted as tipping over (18, 19, e7). It is possible that visceral receptors registering the movements of the viscera are also involved (20, e8). The frequency specificity explains why the slower motion of ships and car journeys often triggers motion sickness where horse riding and riding a mountain bike, as a general rule, do not (11, 13, 21, e7). Optic flow patterns mimicking cyclical to-and-fro motion at a frequency of 0.2 to 0.4 Hz also triggered pseudo motion sickness (22).

Table 1. Six types of kinetogenic sensory conflict. with examples*.

| Category A | Category B | |

| Conflict type | Conflicting sensory information: Visual (VIS) ↔ Vestibular (VES) | Conflicting sensory information: Semicircular canals (SC) ↔ Otolith organs (OT) |

| Type 1 Conflicting motion-related input from two sensory systems | A1 VIS ≠ VES – Watching waves over the side of a swaying ship – Making head movements while wearing an optical device that distorts the visual field or inverts it by means of a prism | B1 SC ≠ OT – Vestibular Coriolis reaction. Head movement about an axis not identical with the body‘s axis of rotation. e.g.. nodding the head while revolving on a rotating chair (Lansberg provocation test) |

| Type 2 First input signals motion. _second input does not | A2 VIS+ VES – – „Pseudo motion sickness,“ „simulator sickness“ – In a stationary simulator or cinema. watching a film shot from a moving vehicle or aircraft subjected to linear and/or angular accelerations | B2 SC+ OT– – Caloric nystagmus – Alcohol-related nystagmus. Head movements during weightlessness („space sickness“) |

| Type 3 Second input signals motion, first input does not | A3 VIS – VES+ – Riding inside a jolting vehicle without any external visual reference – Reading a book below deck on board ship | B3 SC – OT+ – Rotation at a constant speed about the body‘s long axis when horizontal („barbecue rotation“) |

Type A conflict.

Type A sensory conflicts are caused by incongruent afferent information from the vestibular and visual sensory organs.

A clear type B1 conflict (table 1) with motion sickness in the form of a vestibular Coriolis reaction also occurs (11– 13, 16, 23, 24, e9) when people tilt their head forward and backward while spinning about their own long axis (Lansberg test). With type B2 conflict, the semicircular canals are stimulated but the otolith organs are not. Examples are caloric nystagmus and head movements under conditions of weightlessness—a rare trigger (12, 13). The rare type B3 conflict, in which the otolith organs alone are stimulated under laboratory conditions, e.g., during constant rotation (no stimulation of the semicircular canals) about the long axis of the body when horizontal (so-called “barbecue rotation”) (e10). Sensory conflicts with proprioception are less important (11– 16).

Apart from the sensory conflict (or mismatch) theory, there is also the concept of postural instability (25, e11). This emphasizes the role of the motor system and postulates that the main element leading to motion sickness is inefficient postural control that has not yet adapted to the situation. According to another hypothesis, asymmetry between the bilateral otolith organs favors the occurrence of “space sickness” in astronauts (e12).

Explanatory hypotheses like these add to the sensory conflict theory without invalidating it. The latter has become widely accepted, with a PubMed literature search identifying a correspondingly large number of reviews and clinical trials devoted to it as the main factor (ebox).

Habituation is an important element in motion sickness (11– 16). Just as sea sickness often moderates after a few days as the sufferer becomes accustomed to the swaying of the ship, so the converse can happen, although quite rarely: that going ashore after a long voyage can lead to an impaired ability to “switch back” again or “reset,” also known as “mal de débarquement syndrome” or “unsteadiness syndrome.”

Neurophysiologic aspects of nausea and vomiting in motion sickness

Afferents from the vestibular apparatus are involved in all relevant/significant sensory conflicts (table 1), even those in which it is absence of these signals that leads to the mismatch (type A2 conflict, pseudo motion sickness). Patients with bilateral vestibular failure do not get seasick, neither do they develop pseudo motion sickness (26). The afferents from the labyrinth arrive at the vestibular nuclei of the brainstem, which also receive visual and proprioceptive input and are connected with the vestibulocerebellum (27).

Type B conflict.

Incongruence between information from the semicircular canals and the otolith organs produces type B conflict.

The activity of the vestibular nuclei is influenced by numerous transmitters including acetylcholine, dopamine, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), glutamate, glycine, histamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin (24). Efferent projections of these nuclei to the reticular formation, the spinal cord, and the oculomotor nuclei serve the postural motor and the oculomotor systems. Ascending projections from the nuclei reach the temporoparietal cortex areas and insular cortex via the posterolateral thalamus (28). Autonomic reactions can be triggered via connections to the hypothalamus, the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS), the locus ceruleus, and other nuclei of the reticular formation (including the nucleus parabrachialis).

Recent studies have described brain activity in pseudo motion sickness (29, e13). Probands lying in an MRI scanner were shown a moving pattern of stripes that resulted in the sensation of apparent motion (vection) and in about half the probands led to nausea. The onset of nausea coincided with activity in the amygdala, putamen, and dorsal pons; stronger persistent nausea was accompanied by activity in a variety of cortical areas (insular cortex, cingulate and prefrontal cortex, premotor cortex). Brain areas that react selectively to sensory conflicts alone have not yet been identified, however.

Vomiting due to motion sickness can also take place without involving the higher brain areas, however, as animal studies have shown (15, 30). The core area of interest is a network of brainstem regions often referred to for simplicity as the vomiting center. Various inputs from the vestibular nuclei, the area postrema, the gastrointestinal tract, and other nuclei of the reticular formation all converge at a central “switchboard,” the nucleus tractus solitarii. This means that the NTS can be excited by different stimuli such as toxins in the blood, sensory conflicts, or gastrointestinal symptoms, and this results in activation of adjacent areas of the brainstem and thus finally to vomiting.

The biogenic amine histamine is believed to contribute to the triggering of vomiting in sea sickness (31, e14). Animal studies have shown a direct correlation between sea sickness and histamine metabolism (32, e15). After excessive motion, increased histamine concentrations were shown in the inner ear and brain of the animals studied. This is underscored by experiences with sea sickness, where food with a strong histamine content appears to aggravate symptoms (33).

Diagnosis and treatment strategies in motion sickness

Neurophysiologic aspects.

Development of symptoms involves complex central brain structures and nuclear regions with many neurotransmitters participating, including histamine.

Motion sickness can usually be diagnosed on the basis of the characteristic history of a triggering situation and appropriate differential diagnosis (in accordance with guidelines) to rule out other diseases most of which are otorhinolaryngological or neurological, such as Menière’s disease, certain forms of migraine, or psychological causes (34, e16). In addition to these, however, because of the complex pathophysiology of motion sickness, gastroenterological and infectious diseases and any possible orthopedic causes should also be included in the differential diagnosis. Besides these, visual or cardiovascular disorders such as hypotension or hypoglycemia can also trigger symptoms similar to those of motion sickness (e17). Singh et al. provide an up-to-date overview of the causes of nausea and vomiting (35).

The sensory conflict theory is regarded as the best candidate construct of the pathophysiology of motion sickness, and involves complex neurophysiologic signaling with numerous brain nuclear regions and neurotransmitters participating in the production of the symptoms before the “homestretch” of vomiting is reached. Understandably, therefore, approaches to palliating or treating this “disorder” are similarly varied (table 2).

Table 2. Non-drug interventions for motion sickness*1.

| General principle | Measure / comment / special feature | Reference | Evidence*2 |

| Behavioral strategy | |||

| Habituating to the motion pattern | Habituate through prolonged exposure: E.g.. in many people the symptoms of sea sickness regress markedly after a few days at sea Astronauts habituate to microgravity | (11– 14, 31, e39) | A |

| Support habituation e.g.. with physiotherapy exercises ►Comment/special feature: – Reactive exercises. willful countermovements of the head | (e21, e22) | C | |

| Support habituation exercises with virtual reality | (e21, e40) | C | |

| Reducing intersensory conflict | Reduce vestibular stimuli ►Comment/special feature: – Avoid movements outside the axes of motion – Avoid low-frequency movements, especially vertical ones (e.g.. pitching of a ship): – On a ship: amidships is better than at the bow or stern; focus on the horizon – In a car: face forward and look outward – In an airplane: be seated over the wing – In a bus or train: face the direction of travel, look forward and outward | (36) | C |

| Synchronizing the visual system with the motion | Focus on the horizon and on a distant point ►Comment/special feature: – If watching the horizon is not possible, it may help to close eyes and minimize head movements | (36) | C |

| Optokinetic exercises and visual fixation | (37, e19) | C | |

| Use an „artificial“ horizon ►Comment/special feature: – E.g., head-mounted displays or special glasses that provide information about the horizon | (2, e20, e41) | C | |

| Actively synchronizing the body with the motion | Perform active synchronizing movements (e.g.. tilt head into turns), walk around actively, take over steering/control. if possible | (36) | C |

| Breathing technique | Practice active deep diaphragmatic breathing | (e42, e43) | C |

| Alternative approaches to symptom relief | |||

| Using dietary supplements | Ginger | (40, e37, e38) | B |

| Vitamin C | (31) | C | |

| Using placebo effect | Placebo | (e29, e30) | C |

| Placebo plus positive expectations | (e31) | C | |

| Using music and pleasant odors | Pleasant music | (e23) | C |

| Pleasant odors | (e24) | C | |

| Other approaches | |||

| Nerve stimulation | Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) | (e25, e26) | C |

| Magnetic stimulation | Transcranial magnetic stimulation or direct current stimulation for „mal de débarquement“ syndrome | (e44, e45) | C |

| Acupressure | ►Comment/special feature: – Efficacy not proven for motion sickness. but proven for postoperative vomiting (P6 point stimulation) | (e27, e28) | C |

| Evidence assessment (SORT rating) | Evidence assessment according to the SORT rating system (www.aafp.org/afpsort) ►Comment/special feature: – Publications: all clinical studies of the past 10 years on non-drug treatment, search terms „motion sickness,“ „seasickness,“ „simulator sickness,“ „kinetosis“ (PubMed) plus relevant reviews and individual findings | ||

Looking in a vehicle’s direction of travel or focusing on the horizon are simple measures that are well known to avoid or at least palliate the symptoms of motion sickness, most likely by reducing intersensory conflict (36). Lying down and reducing visual influences can also have a positive effect. One approach to treatment along similar lines which may perhaps also prove useful against sea sickness is the head-mounted display providing an artificial horizon or horizon information (2, e18– e20).

Another approach is to try appropriate measures to improve habituation to motion stimuli. Such measures include desensitizing physiotherapy (reactive motion and body positioning exercises [e21, e22]) and practicing actively synchronizing body movements with the motion, including tilting the head into turns (36).

Some centers offer specialized habituation training before the start of a sea voyage for patients who suffer from sea sickness (37). This can include optokinetic desensitization over a period of weeks, plus simulated sea motion (swell) and balance training. As a general principle, habituation training attempts to reproduce the disturbing motion pattern as accurately as possible. Repeated exposure training can induce adequate habituation lasting for months, as described in detail by Zhang et al. (38).

Diagnosis.

Motion sickness is diagnosed on the basis of a history of a triggering situation and exclusion of neurologic, otorhinolaryngologic, gastroenterologic, and infectious diseases and orthopedic causes.

Positive effects seem also to have been achieved by the application of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and by general stress-reduction measures such as pleasant music or odors (e23– e26).

However, it must be pointed out at this stage that for many of the non-drug interventions in particular, too few prospective controlled clinical studies have yet been carried out for a judgment on their true efficacy to be made; one study dating from 1990 on acupressure bands (“SeaBand”) to prevent sea sickness did not show a positive effect, although P6 point stimulation has been shown to be effective against postoperative vomiting (e27, e28).

It is also important to mention that several recent clinical studies have shown considerable positive placebo effects of drug and non-drug interventions on symptoms of motion sickness (e29– e31). On the one hand this makes it harder to assess the true efficacy of individual treatments, but on the other hand it can also be employed to beneficial effect.

Finally, especially at sea, avoiding foods with a high histamine content, such as tuna, some kinds of cheese, salami, sauerkraut, and red wine (foods/drinks altered by microorganisms) is one of the non-drug interventions or preventive measures (33).

The various forms of drug therapy (table 3) are based primarily on the role of histamine, referred to above, in the pathophysiology of sea sickness, and on the importance of muscarinic receptors in the vestibular apparatus and vomiting center. Preparations containing antihistamines and anticholinergic drugs are both important here. An example of a monodrug is dimenhydrinate, which dissociates in the blood to diphenhydramine and 8-chlorotheophylline. Dimenhydrinate is often prescribed in combination with cinnarizine for short-term acute therapy. This H1-antagonist acts additionally as a dopamine, serotonin, and bradykinin receptor antagonist and as a calcium inhibitor. This is believed to result in synergistic effects in the vestibular apparatus. Typical adverse effects of the antihistaminergic properties of dimenhydrinate alone or in combination with cinnarizine are fatigue, slowed reactions, and impaired coordination and concentration. The incidence of adverse effects varies greatly in prospective studies and has been estimated at about 5% (e32– e35); the duration of action when taken orally is 4–8 hours.

Table 3. Drug therapy for motion sickness.

| Category | Indication | Dosage | How to use | Adverse effects |

| Anticholinergics | ||||

| Scopolamine | Sea and travel sickness | Transdermal 1.5 mg/patch | For prevention, 6–8 h before exposure, effective for 72 h | Frequent: dry eyes and mouth, mydriasis with light sensitivity Occasional: impaired vision, drowsiness, headache, sedation Rare: acute angle closure glaucoma, confusion, contact dermatitis, unilateral mydriasis, urinary retention |

| Antihistamines (in ascending order of sedation potential) | ||||

| Cinnarizine plus dimenhydrinate | Vertigo of varying pathogenesis | 20 mg cinnarizine/40 mg _dimenhydrinate orally | For acute treatment only, three times a day, 4 weeks maximum | Frequent: drowsiness, headache, dry mouth, stomach pains Occasional: paresthesia, amnesia, tinnitus, tremor, nervousness, convulsions, indigestion, nausea, diarrhea, sweating, skin rashes Rare: urinary retention |

| Dimenhydrinate | Nausea and vomiting of varying etiology Motion sickness | 50–100 mg single oral dose, up to 300 mg/day 62–186 mg/day i.v. 100–300 mg/day i.m. (up to 400 mg/day) Reduce the dosage for children, do not give to children under the age of 3 | For prevention, first dose 0.5–1 h before the start of travel Space out doses regularly over the day | Very frequent: somnolence, drowsiness, dizziness, muscular weakness Frequent: restlessness, excitement, insomnia, anxiety or tremor, impaired vision, increased intraocular pressure, tachycardia constipation, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, pain in the stomach area, dry oral and nasal mucosa. blocked nose, urinary retention |

| Diphenhydramine | Nausea, vomiting, sleep disturbances | 50 mg/day (this is also the highest dose) Do not give to children or adolescents under 18 years of age |

Short-term therapy 30 min before going to sleep | Risk of addiction. development of tolerance Very frequent: somnolence; drowsiness with impaired concentration on the following day, especially after insufficient length of sleep; dizziness and muscular weakness Frequent: headache. gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) and anticholinergic effects such as dry mouth, constipation, gastroesophageal reflux, impaired vision or impaired micturition |

| Promethazine | Nausea and vomiting | Individually tailored. starting with 20–30 mg orally, dosage may be increased by 10 mg given at intervals (up to 100 mg/day) In children over 2 and young persons under 18. use only if urgently indicated | Reserve drug; give first dose at night; if dosage increased, then also in morning and at midday | Very frequent: sedation. anticholinergic effects, extrapyramidal symptoms |

Non-drug treatment.

Various non-drug interventions relieve the symptoms of motion sickness, by, for instance, reducing sensory conflict.

In a prospective study of patients with vestibular disorders, the response rate to a combination of dimenhydrinate and cinnarizine was 78%, whereas when these drugs taken separately the rates were only 45% and 55% respectively (e33). Anticholinergics in the form of transdermal scopolamine patches (TTS-S, transdermal therapeutic system—scopolamine) are also often used (38). The patches have a duration of action of up to 3 days and are used both preventively and for long-term therapy.

Preventive medication.

Anticholinergics are used for prevention, e.g., transdermal scopolamine. Administration should be 6 to 8 h before travel starts or before the expected onset of motion sickness.

Drug treatment.

Apart from a number of non-drug interventions, H1-antihistamines with the lowest possible potential for sedation are the main treatment of choice for vertigo, nausea, and vomiting due to motion sickness.

There are no prospective randomized studies on the effect of this treatment on motion sickness, nor any valid comparative studies with other drugs. However, the authors of a Cochrane review conclude that the effect of scopolamine is not superior to that of antihistamines or combination drugs, but it does have fewer adverse effects (39). The adverse effects derive from its anticholinergic properties and include, especially, mucosal dryness and mydriasis, palpitations, urinary retention, and, very rarely, hallucinogenic effects (e36). All of these substances have in common that they do not totally prevent or suppress sea sickness, for example, but they can greatly ameliorate symptoms. This comes at a cost, however, of adverse effects that can impair alertness and thus represent a safety risk for many tasks, e.g., on board a ship (19, 23).

Apart from these drug therapies, natural remedies are also used to suppress sea sickness. There are indications, even including a prospective, placebo-controlled study of sea cadets, showing that ginger can be used as an antiemetic with few adverse effects (40, e37, e38). The substances it contains are believed to act as antagonists at the 5-HT3 receptor, which has an important role in the vomiting center.

High-dose vitamin C, another remedy which has been credited with some antihistaminergic effect, was shown in a prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to reduce the symptoms of sea sickness without identifiable adverse effects (31).

The dopamine antagonist metoclopramide is not indicated for the treatment of motion sickness. Metoclopramide can cause extrapyramidal symptoms in children and adolescents and/or when given at high doses, and if given over long periods, especially in older patients, can trigger tardive dyskinesia that can sometimes be irreversible. For this reason, metoclopramide may be used only for the prevention of delayed nausea and vomiting after chemo- and radiotherapy or for symptomatic treatment of nausea and vomiting due to acute migraine (and not in children or adolescents). Particularly effective antiemetics such as the 5-HT3 antagonist ondansetron or the neurokinin-1 antagonist aprepitant are also contraindicated for the treatment of motion sickness. Ondansetron can very often cause headache and sometimes seizures, extrapyramidal symptoms, and constipation, among other effects. Aprepitant often causes headache, constipation, and other adverse effects which may appear acceptable in the context of weighing risks against benefits during a highly emetogenic form of chemotherapy, but are unacceptable in the context of preventing motion sickness.

Conclusion

The explanatory model of sensory conflicts involving primarily the visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive systems describes how motion sickness arises in a range of forms, from classic sea sickness to “simulator sickness” in modern virtual reality systems. The symptoms can vary greatly, ranging from reduced alertness (sopite syndrome) to full-blown severe vomiting. The importance of sopite syndrome and how to measure it objectively is the subject of ongoing research.

Contraindicated drugs.

Because of severe adverse effects, the use of metoclopramide, ondansetron, or aprepitant to prevent or treat motion sickness is contraindicated.

Conclusion.

The development of vehicles without constant outside view, and of virtual reality environments, requires drug options with fewer adverse effects.

Reflecting the complexity of the central nucleus areas and neurotransmitters involved in the development of the symptoms of motion sickness, options for treatment include a number of approaches that differ greatly from each other but may nevertheless achieve success. They range from drug treatment, tried and tested and based mainly on H1-antihistamines and anticholinergics, to symptom relief with vitamin C and ginger, to a multiplicity of behavioral measures aimed at desensitizing or improving habituation by means of physiotherapeutic exercises or habituation to stimuli that trigger motion sickness.

Given the increasing relevance of sensory conflicts, not just in faster moving vehicles, but in digitally processed environments, in some of which full alertness is still absolutely essential, it would seem that continued development of drug options with fewer adverse effects is required.

Further information on CME.

Participation in the CME certification program is possible only over the Internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de. This unit can be accessed until 6 January 2019. Submissions by letter, e-mail or fax cannot be considered.

-

The following CME units can still be accessed for credit:

„The Diagnosis and Treatment of Anxiety Disorders“ (issue 37/2018) until 9 December 2018

„Arterial Hypertension“ (issue 33–34/2018) until 11 November 2018

„Drug Hypersensitivity“ (issue 29–30/2018) until 14 October 2018

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Continuing Medical Education. Participants in the CME program can manage their CME points with their 15-digit “uniform CME number” (einheitliche Fortbildungsnummer, EFN), which is found on the CME card (8027XXXXXXXXXXX). The EFN must be stated during registration on www.aerzteblatt.de (“Mein DÄ”) or else entered in “Meine Daten,” and the participant must agree to communication of the results.

CME credit for this unit can be obtained via cme.aerzteblatt.de until 6 January 2019. Only one answer is possible per question. Please select the answer that is most appropriate.

Question 1

Which of the following best describes motion sickness?

A predominantly neurological pattern of symptoms triggered by motion of a person’s own body

Gastrointestinal symptoms occurring due to motion of the environment, e.g., on a ship at sea

A pattern of autonomic symptoms occurring as a stress reaction to motion of a person’s own body or its environment

Predominantly orthopedic symptoms related to the cervical spine occurring as a result of motion of the person’s own body, typically in the form of vertigo

An adjustment disorder, typically occurring during adolescence, of the immature semicircular canals in response to over-rapid changes in head motion

Question 2

What percentage of healthy volunteers developed symptoms of “simulator sickness” when wearing virtual reality (VR) glasses?

27%;

43%;

56%;

61%;

76%

Question 3

One of the following natural substances has been documented as having some antiemetic effect. Which one?

Turmeric;

ginger;

fennel;

sage;

chamomile

Question 4

What is meant by “sopite syndrome”?

A condition of apathy and withdrawal or lethargy, representing early symptoms of motion sickness

A form of motion sickness involving increased gastrointestinal activity in response to exposure to strong environmental motion

A form of motion sickness seen in older people with chronic neurologic disorders such as dementia

An apparent adjustment reaction after prolonged exposure to environmental motion, leading to improved alertness in the person affected

Acute onset of motion sickness with nausea and vomiting within the first 30 min of exposure, in response to even low-level environmental motion, e.g., when traveling as a passenger in a local bus

Question 5

Which risk group is especially likely to suffer from motion sickness?

Children between 1 and 5 years of age

Children between 6 and 12 years of age

Adolescents between 11 and 18 years of age

Adults between 18 and 50 years of age

Older persons (>76 years of age)

Question 6

What is meant by sensory conflict in the pathogenesis of motion sickness?

Visual sensory input leading to incorrect return movements of the eyes

Contradictory or incongruent motion-related information from sensory organs

Afferent input especially from dermal sense organs about apparent temperature changes

Misrouted efferent potentials with hyperexcitability of alpha motoneurons

Hyperactivity of the parasympathetic nervous system during changes to the body during rotational movement at increasing speed

Question 7

Which differential diagnosis is most likely to induce symptoms resembling those of motion sickness?

Parkinson’s disease;

hypertension;

hyperthyroidism;

otitis externa;

hypoglycemia

Question 8

Which drug class is the treatment of choice for motion sickness?

5-HT3 antagonists;

metoclopramide;

vitamin D;

antihistamines;

dopamine antagonists

Question 9

A 34-year-old woman with a history of sea sickness is planning a 3-day cruise trip. What should be the primary advice regarding medication to take if she develops acute symptoms?

50–100 mg dimenhydrinate several times a day, up to a maximum of 300 mg/day.

Ondansetron 8 mg several times a day.

From the start of the cruise trip until the ship enters harbor: 1 × daily 125 mg aprepitant.

From 24 h before the start of the cruise trip until the ship enters harbor: 1 × daily 10 mg metoclopramide; more if required, up to 3 × daily 10 mg.

From the start of the cruise trip until the ship enters harbor: 1 × daily 30 mg promethazine, up to 100 mg/day.

Question 10

A 21-year-old man training to be a marine engineer, who had a tendency to travel sickness as a child, asks for advice before a planned sea voyage of several weeks. What treatment strategy should you recommend?

Given his tendency to travel sickness as a child, he should avoid sea voyages lasting longer than 3 days.

Neither preventive nor as-required medication is indicated, as adults on board a ship habituate adequately after about a week.

If and when symptoms start, he should use antihistamine-based medication or scopolamine patches as required and watch the horizon. He should be aware of the possible adverse effects of the medication.

Specific long-term medication with a dopamine antagonist, e.g., metoclopramide 10 mg 1 × daily, is indicated, and he should stay at the bow or stern of the ship as much as possible.

As-required medication with a 5-HT3 antagonist, such as ondansetron, is indicated.

►Participation is possible only via the Internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Kersti Wagstaff, MA

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Jelinek T. Georg Thieme Verlag. Stuttgart, New York: 2012. Kursbuch Reisemedizin: Beratung, Prophylaxe, Reisen mit Erkrankungen; pp. 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krueger WWO. Controlling motion sickness and spatial disorientation and enhancing vestibular rehabilitation with a user-worn see-through display. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(2):17–35. doi: 10.1002/lary.21373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diels C, Bos JE. Self-driving carsickness. Appl Ergon. 2016;53 Pt B:374–382. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riola JM, Pérez R. The seasickness phenomenom. J Marit Res. 2012;9:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Regan EC, Price KR. The frequency of occurrence and severity of side-effects of immersion virtual reality. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1994;65:527–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paillard AC, Quarck G, Paolino F, et al. Motion sickness susceptibility in healthy subjects and vestibular patients: effects of gender, age and trait-anxiety. J Vestib Res Equilib Orientat. 2013;23:203–209. doi: 10.3233/VES-130501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klosterhalfen S, Kellermann S, Pan F, Stockhorst U, Hall G, Enck P. Effects of ethnicity and gender on motion sickness susceptibility. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2005;76:1051–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bos JE, Damala D, Lewis C, Ganguly A, Turan O. Susceptibility to seasickness. Ergonomics. 2007;50:890–901. doi: 10.1080/00140130701245512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou W, Wang J, Pan L, et al. Sex and age differences in motion sickness in rats: The correlation with blood hormone responses and neuronal activation in the vestibular and autonomic nuclei. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reavley CM, Golding JF, Cherkas LF, Spector TD, MacGregor AJ. Genetic influences on motion sickness susceptibility in adult women: a classical twin study. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2006;77:1148–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertolini G, Straumann D. Moving in a moving world: A review on vestibular motion sickness. Front Neurol. 2016;7 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2016.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lackner JR. Motion sickness: more than nausea and vomiting. Exp Brain Res. 2014;232:2493–2510. doi: 10.1007/s00221-014-4008-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmäl F. Neuronal mechanisms and the treatment of motion sickness. Pharmacology. 2013;91:229–241. doi: 10.1159/000350185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tal D, Hershkovitz DKaminski-Graif, Wiener G, Samuel O, Shupak A. Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials and habituation to seasickness. Clin Neurophys. 2013;124:2445–2449. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yates BJ, Miller AD, Lucot JB. Physiological basis and pharmacology of motion sickness: an update. Brain Res Bull. 1998;47:395–406. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reason JT. Motion sickness adaptation: a neural mismatch model. J R Soc Med. 1978;71:819–829. doi: 10.1177/014107687807101109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golding JF, Mueller AG, Gresty MA. A motion sickness maximum around the 02 Hz frequency range of horizontal translational oscillation. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2001;72:188–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bronstein AM, Golding JF, Gresty MA. Vertigo and dizziness from environmental motion: visual vertigo, motion sickness, and drivers’ disorientation. Semin Neurol. 2013;33:219–230. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1354602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golding JF, Gresty MA. Pathophysiology and treatment of motion sickness. Curr Opin Neurol. 2015;28:83–88. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Gierke HE, Parker DE. Differences in otolith and abdominal viscera graviceptor dynamics: implications for motion sickness and perceived body position. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1994;65:747–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Golding JF, Gresty MA. Motion sickness. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18:29–34. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200502000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diels C, Howarth PA. Frequency characteristics of visually induced motion sickness. Hum Factors. 2013;55:595–604. doi: 10.1177/0018720812469046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shupak A, Gordon CR. Motion sickness: advances in pathogenesis, prediction, prevention, and treatment. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2006;77:1213–1223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takeda N, Morita M, Horii A, Nishiike S, Kitahara T, Uno A. Neural mechanisms of motion sickness. J Med Invest. 2001;48:44–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riccio GE, Stoffregen TA. An ecological theory of motion sickness and postural instability. Ecol Psychol. 1991;3:195–240. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Money KE. Motion sickness. Physiol Rev. 1970;50:1–39. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1970.50.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barmack NH. Central vestibular system: vestibular nuclei and posterior cerebellum. Brain Res Bull. 2003;60:511–541. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(03)00055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dieterich M, Brandt T. Functional brain imaging of peripheral and central vestibular disorders. Brain. 2008;131:2538–2552. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sclocco R, Kim J, Garcia RG, et al. Brain circuitry supporting multi-organ autonomic outflow in response to nausea. Cereb Cortex. 2016;26:485–497. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yates BJ, Catanzaro MF, Miller DJ, McCall AA. Integration of vestibular and emetic gastrointestinal signals that produce nausea and vomiting: potential contributions to motion sickness. Exp Brain Res. 2014;232:2455–2469. doi: 10.1007/s00221-014-3937-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jarisch R, Weyer D, Ehlert E, et al. Impact of oral vitamin C on histamine levels and seasickness. J Vestib Res Equilib Orientat. 2014;24:281–288. doi: 10.3233/VES-140509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takeda N, Morita M, Hasegawa S, Horii A, Kubo T, Matsunaga T. Neuropharmacology of motion sickness and emesis. A review. Acta Oto-Laryngol Suppl. 1993;501:10–15. doi: 10.3109/00016489309126205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jarisch R. Georg Thieme. Stuttgart, New York: 2013. Histaminintoleranz - Histamin und Seekrankheit; pp. 26–39. [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Esch BF, van Wensen E, van der Zaag-Loonen HJ, van Benthem PPG, van Leeuwen RB. Clinical characteristics of benign recurrent vestibulopathy: clearly distinctive from vestibular migraine and menière’s disease? Otol Neurotol Off Publ Am Otol Soc Am Neurotol Soc Eur Acad Otol Neurotol. 2017;38:357–363. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh P, Yoon SS, Kuo B. Nausea: a review of pathophysiology and therapeutics. Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2016;9:98–112. doi: 10.1177/1756283X15618131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brainard A, Gresham C. Prevention and treatment of motion sickness. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ressiot E, Dolz M, Bonne L, Marianowski R. Prospective study on the efficacy of optokinetic training in the treatment of seasickness. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2013;130:263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang LL, Wang JQ, Qi RR, Pan LL, Li M, Cai YL. Motion sickness: current knowledge and recent advance. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2016;22:15–24. doi: 10.1111/cns.12468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spinks A, Wasiak J. Scopolamine (hyoscine) for preventing and treating motion sickness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;6 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002851.pub4. CD002851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.White B. Ginger: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75:1689–1691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Li J, Zhu L, Yuan W, Jin G, Sun J. [Habituation of seasickness in adult during a long voyage] Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2012;47:642–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Graybiel A, Knepton J. Sopite syndrome: a sometimes sole manifestation of motion sickness. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1976;47:873–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Geiger J. Gleichgewichts-, Lage- und Bewegungssinn. In: Pape HC, Kurtz A, Silbernagl S, editors. Physiologie. 7. Stuttgart Georg Thieme: 2014. pp. 756–768. [Google Scholar]

- E4.Kennedy RS, Drexler J, Kennedy RC. Research in visually induced motion sickness. Appl Ergon. 2010;41:494–503. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.O’Hanlon JF, McCauley ME. Motion sickness incidence as a function of the frequency and acceleration of vertical sinusoidal motion. Aerosp Med. 1974;45:366–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Griffin MJ, Mills KL. Effect of frequency and direction of horizontal oscillation on motion sickness. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2002;73:537–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Golding JF. Motion sickness. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;137:371–390. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63437-5.00027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.von Gierke HE, Parker DE. Differences in otolith and abdominal viscera graviceptor dynamics: implications for motion sickness and perceived body position. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1994;65:747–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Dai M, Kunin M, Raphan T, Cohen B. The relation of motion sickness to the spatial-temporal properties of velocity storage. Exp Brain Res. 2003;151:173–189. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1479-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Leger A, Money KE, Landolt JP, Cheung BS, Rodden BE. Motion sickness caused by rotations about earth-horizontal and earth-vertical axes. J Appl Physiol. 1981;50:469–477. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1981.50.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Riccio GE, Stoffregen TA. An ecological theory of motion sickness and postural instability. Ecol Psychol. 1991;3:195–240. [Google Scholar]

- E12.Nooij SA, Vanspauwen R, Bos JE, Wuyts FL. A re-investigation of the role of utricular asymmetries in Space Motion Sickness. J Vestib Res Equilib Orientat. 2011;21:141–151. doi: 10.3233/VES-2011-0400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Napadow V, Sheehan JD, Kim J, et al. The brain circuitry underlying the temporal evolution of nausea in humans. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23:806–813. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Watanabe T, Yamatodani A, Maeyama K, Wada H. Pharmacology of alpha-fluoromethylhistidine, a specific inhibitor of histidine decarboxylase. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1990;11:363–367. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(90)90181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Lucot JB, Takeda N. Alpha-fluoromethylhistidine but not diphenhydramine prevents motion-induced emesis in the cat. Am J Otolaryngol. 1992;13:176–180. doi: 10.1016/0196-0709(92)90119-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Neuhauser H, Lempert T. Vertigo and dizziness related to migraine: a diagnostic challenge. Cephalalgia Int J Headache. 2004;24:83–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2004.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Aust G. [Equilibrium disorders and their diagnosis in childhood] Laryngorhinootologie. 1991;70:532–537. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-998091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Buker TJ, Vincenzi DA, Deaton JE. The effect of apparent latency on simulator sickness while using a see-through helmet-mounted display: reducing apparent latency with predictive compensation. Hum Factors. 2012;54:235–249. doi: 10.1177/0018720811428734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Bonato F, Bubka A, Krueger WWO. A wearable device providing a visual fixation point for the alleviation of motion sickness symptoms. Mil Med. 2015;180:1268–1272. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Tal D, Gonen A, Wiener G, et al. Artificial horizon effects on motion sickness and performance. Otol Neurotol Off Publ Am Otol Soc Am Neurotol Soc Eur Acad Otol Neurotol. 2012;33:878–885. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318255ddab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E21.Wada Y, Nishiike S, Kitahara T, et al. Effects of repeated snowboard exercise in virtual reality with time lags of visual scene behind body rotation on head stability and subjective slalom run performance in healthy young subjects. Acta Otolaryngol. 2016;136:1121–1124. doi: 10.1080/00016489.2016.1193890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E22.Robinson KD. Die Wirkung eines reaktiven Trainings auf die Kinetosesymptomatik. Masterarbeit Sportwissenschaft; Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- E23.Keshavarz B, Hecht H. Pleasant music as a countermeasure against visually induced motion sickness. Appl Ergon. 2014;45:521–527. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E24.Keshavarz B, Stelzmann D, Paillard A, Hecht H. Visually induced motion sickness can be alleviated by pleasant odors. Exp Brain Res. 2015;233:1353–1364. doi: 10.1007/s00221-015-4209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E25.Chu H, Li MH, Juan SH, Chiou WY. Effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on motion sickness induced by rotary chair: a crossover study. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18:494–500. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E26.Chu H, Li MH, Huang YC, Lee SY. Simultaneous transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation mitigates simulator sickness symptoms in healthy adults: a crossover study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13 doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E27.Bruce DG, Golding JF, Hockenhull N, Pethybridge RJ. Acupressure and motion sickness. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1990;61:361–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E28.Lee A, Fan LT. Stimulation of the wrist acupuncture point P6 for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003281.pub3. CD003281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E29.Müller V, Remus K, Hoffmann V, Tschöp MH, Meissner K. Effectiveness of a placebo intervention on visually induced nausea in women—a randomized controlled pilot study. J Psychosom Res. 2016;91:9–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E30.Weimer K, Horing B, Muth ER, Scisco JL, Klosterhalfen S, Enck P. Different disclosed probabilities to receive an antiemetic equally decrease subjective symptoms in an experimental placebo study: to be or not to be sure. Clin Ther. 2017;39:487–501. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E31.Horing B, Weimer K, Schrade D, et al. Reduction of motion sickness with an enhanced placebo instruction: an experimental study with healthy participants. Psychosom Med. 2013;75:497–504. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182915ee7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E32.Hahn A, Sejna I, Stefflova B, Schwarz M, Baumann W. A fixed combination of cinnarizine/dimenhydrinate for the treatment of patients with acute vertigo due to vestibular disorders : a randomized, reference-controlled clinical study. Clin Drug Investig. 2008;28:89–99. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200828020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E33.Hahn A, Novotný M, Shotekov PM, Cirek Z, Bognar-Steinberg I, Baumann W. Comparison of cinnarizine/dimenhydrinate fixed combination with the respective monotherapies for vertigo of various origins. Clin Drug Investig. 2011;31:371–383. doi: 10.2165/11588920-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E34.Novotný M, Kostrica R. Fixed combination of cinnarizine and dimenhydrinate versus betahistine dimesylate in the treatment of Ménière’s disease: a randomized, double-blind, parallel group clinical study. Int Tinnitus J. 2002;8:115–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E35.Scholtz AW, Schwarz M, Baumann W, Kleinfeldt D, Scholtz HJ. Treatment of vertigo due to acute unilateral vestibular loss with a fixed combination of cinnarizine and dimenhydrinate: a double-blind, randomized, parallel-group clinical study. Clin Ther. 2004;26:866–877. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(04)90130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E36.Rubner O, Kummerhoff PW, Haase H. [An unusual case of psychosis caused by long-term administration of a scopolamine membrane patch Paranoid hallucinogenic and delusional symptoms] Nervenarzt. 1997;68:77–79. doi: 10.1007/s001150050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E37.Hoffman T. Ginger: an ancient remedy and modern miracle drug. Hawaii Med J. 2007;66:326–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E38.Grøntved A, Brask T, Kambskard J, Hentzer E. Ginger root against seasickness. A controlled trial on the open sea. Acta Otolaryngol. 1988;105:45–49. doi: 10.3109/00016488809119444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E39.Domeyer JE, Cassavaugh ND, Backs RW. The use of adaptation to reduce simulator sickness in driving assessment and research. Accid Anal Prev. 2013;53:127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2012.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E40.Micarelli A, Viziano A, Augimeri I, Micarelli D, Alessandrini M. Three-dimensional head-mounted gaming task procedure maximizes effects of vestibular rehabilitation in unilateral vestibular hypofunction: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Int J Rehabil Res Int Z Rehabil Rev Int Rech Readaptation. 2017;40:325–332. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0000000000000244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E41.Buker TJ, Vincenzi DA, Deaton JE. The effect of apparent latency on simulator sickness while using a see-through helmet-mounted display: reducing apparent latency with predictive compensation. Hum Factors. 2012;54:235–249. doi: 10.1177/0018720811428734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E42.Russell MEB, Hoffman B, Stromberg S, Carlson CR. Use of controlled diaphragmatic breathing for the management of motion sickness in a virtual reality environment. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2014;39:269–277. doi: 10.1007/s10484-014-9265-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E43.Stromberg SE, Russell ME, Carlson CR. Diaphragmatic breathing and its effectiveness for the management of motion sickness. Aerosp Med Hum Perform. 2015;86:452–457. doi: 10.3357/AMHP.4152.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E44.Cha YH, Urbano D, Pariseau N. Randomized single blind sham controlled trial of adjunctive home-based tDCS after rTMS for mal de debarquement syndrome: safety, efficacy, and participant satisfaction assessment. Brain Stimulat. 2016;9:537–544. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E45.Cha YH, Deblieck C, Wu AD. Double-blind sham-controlled crossover trial of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for mal de debarquement syndrome. Otol Neurotol Off Publ Am Otol Soc Am Neurotol Soc Eur Acad Otol Neurotol. 2016;37:805–812. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E46.Golding JF. Motion sickness susceptibility. Auton Neurosci. 2006;129:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E47.Gil A, Nachum Z, Tal D, Shupak A. A comparison of cinnarizine and transdermal scopolamine for the prevention of seasickness in naval crew: a double-blind, randomized, crossover study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2012;35:37–39. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e31823dc125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E48.Sherman CR. Motion sickness: review of causes and preventive strategies. J Travel Med. 2002;9:251–256. doi: 10.2310/7060.2002.24145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E49.Zajonc TP, Roland PS. Vertigo and motion sickness Part II: pharmacologic treatment. Ear Nose Throat J. 2006;85:25–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E50.Nachum Z, Shupak A, Gordon CR. Transdermal scopolamine for prevention of motion sickness: clinical pharmacokinetics and therapeutic applications. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2006;45:543–566. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200645060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E51.Estrada A, LeDuc PA, Curry IP, Phelps SE, Fuller DR. Airsickness prevention in helicopter passengers. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2007;78:408–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E52.Brand JJ, Colquhoun WP, Gould AH, Perry WL. (—)-Hyoscine and cyclizine as motion sickness remedies. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1967;30:463–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1967.tb02152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E53.Paul MA, MacLellan M, Gray G. Motion-sickness medications for aircrew: impact on psychomotor performance. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2005;76:560–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E54.Gordon CR, Shupak A. Prevention and treatment of motion sickness in children. CNS Drugs. 1999;12:369–381. [Google Scholar]

- E55.Cheung BS, Heskin R, Hofer KD. Failure of cetirizine and fexofenadine to prevent motion sickness. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37:173–177. doi: 10.1177/106002800303700201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]