Abstract

The connection between menstruation and psychosis has been recognized since the 18th Century. However, there are few case reports available in modern times describing about 30 patients with this condition. The psychosis may occur in the premenstrual phase in some patients and in others it begins with the onset of menses. Polymorphic psychosis is the commonly described clinical picture in these patients with an admixture of mood symptoms and psychotic symptoms. We describe a 42-year old lady who developed psychotic symptoms with the onset of her menses. The patient had irritability and aggression, persecutory ideas, hallucinatory behavior, increased religiosity, formal thought disorder, disorganized behavior and poor self-care lasting for about 20 days after which she will spontaneously remit for about 10 days till the onset of her next menses. These symptoms began about 13 years after her last childbirth and were present in this cyclical manner for the last seven years. She was admitted in view of gross disorganization and was treated with 4 mg per day of risperidone. She did not develop symptoms with onset of her next menstrual period and was discharged. She maintained well on the prophylaxis for a period of three months. After that, she discontinued medications and had a relapse of symptoms lasting the first two weeks of her menstrual cycle and remained well for about two weeks thereafter. Hormonal assays did not reveal abnormal levels of gonadal hormones. We discuss the association between menstrual cycles and the potential association of psychosis with estrogen levels. Various conditions that lead to fluctuation in estrogen levels, such as menopause, postpartum period as well as post-oopherectomy period have been described to lead to a risk for psychotic symptoms. Similarly, the cyclical changes in estrogen levels during the course of a menstrual cycle leads to psychosis in some women.

Keywords: Episodic psychosis, estrogen, menstrual psychosis

INTRODUCTION

In the early 18th century, a possible connection was observed between menstruation and psychiatric disorders. Menstrual psychosis has an acute onset and is characterised by confusion, stupor and mutism, delusions, hallucinations, or a manic syndrome lasting for a brief duration, with full recovery.[1] These symptoms maintain periodicity in rhythm with the menstrual cycle. The symptoms may appear in the premenstrual phase or may begin with the onset of menstrual flow (catamenial psychoses).[1] Usually, menstrual psychosis has a polymorphism of both psychotic and affective symptoms.[1] Though menstrual psychoses share their affective features with premenstrual syndrome, they can be differentiated by the occurrence of psychotic symptoms with a polymorphic picture.[2,3,4] Although conventional psychotropic drugs can shorten episodes, their efficacy in preventing recurrence is still doubtful.[4] There are three confirmed and thirty possible case reports.[1] With the aim of contributing to the literature, we are reporting a case of menstrual psychosis with its own tone of uniqueness.

CASE REPORT

A 42-year-old woman, with two children aged 22 and 20 years, presented to us with history of an episodic psychotic illnessof seven years duration. The episodes were characterised by acute onset of irritability and aggression, persecutory ideas, hallucinatory behaviour, over-religiosity, disorganisation, formal thought disorder and incoherent speech, with disturbed biological functions and poor self-care. These symptoms usually began on the first day of menstruation every month and lasted for twenty days. During this period, the patient would restrict herself to one room and doesnot interact with family members. In the remaining few days, she would have gradual improvement in her symptoms and reach her premorbid self, without any psychotic or mood symptoms and with complete functional recovery. She did not have any features suggestive of organicity. She has had regular menstrual cycles from menarche, with no history suggestive of similar presentation until seven years back or premenstrual syndrome anytime in the past. These episodes began about thirteen years after her last childbirth. There was no family history of such episodes or any other psychiatric illness.

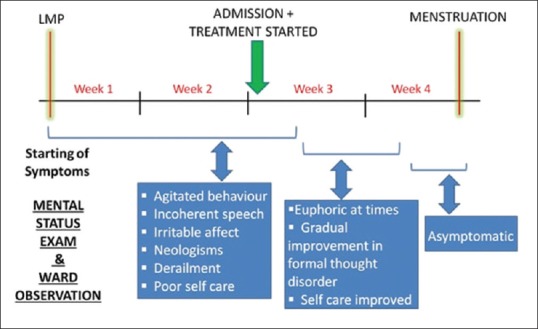

She presented to us two weeks after her last menstrual period. Mental status examination at admission revealed irritability, agitated behaviour, and formal thought disorder. In the second week of admission, she was found to be euphoric at times, with a decrease in mood symptoms and the formal thought disorder, and her self-care gradually improved [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Evolving symptoms and signs during the current menstrual cycle

Her blood investigations such as hemogram and renal, liver and thyroid function tests were normal.

Gonadal hormonal assay, done by Chemiluminescence method during follicular phase of menstrual cycle, revealed the following levels: Follicle Stimulating Hormone (4.8 mIU/ml), Progesterone (26.7 ng/dl), Leutinizing Hormone (1.3 mIU/ml). They were within normal limits, whereas prolactin level (54.2 ng/ml) was mildly elevated. Estradiol levels were not done due to logistic issues.

She was started on T. Risperidone 2mg and up-titrated to 4 mg without any major side effects. She was asymptomatic by the third week of hospital stay. OnT. Risperidone 4 mg/day, she did not have a recurrence of psychotic symptoms with the onset of the next menstrual cycle. Hence, she was discharged on the same dose. She was maintaining well without relapse of symptoms for the next three months, after which she was lost to follow-up for the next two years. Telephonic follow-up revealed that she discontinued treatment after a few months and was asymptomatic. In the last three months, she has a relapse of symptoms in the form of irritability, hallucinatory behaviour, over-religiosity, and disorganisation of speech and activities. These symptoms occurred for the first ten days to two weeks after menses, and then the patient is relatively better for the subsequent two weeks. She has been advised to follow-up with us for continued treatment. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient and mother for this case report.

DISCUSSION

We, thus, report a possible case of menstrual psychosis. The case meets the definition of menstrual psychosis,[1] given the polymorphic picture,[4] and there was no objective evidence suggestive of other psychiatric disorders. Previous reports have mentioned onset from menarche or menopause, or soon after childbirth.[1,3] On the contrary, the case reported here had a late age of onset of menstrual psychosis, which we would like to highlight. This may be theoretically due to a subtler impairment in the hormonal levels or receptor sensitivity rather than a more gross level of impairment, which may have led to more frank psychotic symptoms. The presentation of “Oestrogen withdrawal related psychosis” (occurring as a drastic reduction in hormone levels seen in postpartum, post-oophorectomy states) is more severe compared to our case, which is an “Oestrogen Condition associated psychosis” occurring in relation to smaller changes in hormonal levels (pre-menopausal, menopausal and catamenial psychoses).[5,6] The case reported here hadneither abnormal menstruation nor family history of menstrual psychosis, two factorsidentified as risk factors in earlier studies.[4,5] She had a recurrence of psychotic symptoms in a cyclical manner, with the symptoms being present during the first two weeks of the menstrual cycle and absent in the subsequent two weeks. She had normal hormonal levels, as has been reported in some of the previous papers too.[7] However, some papers[3] had reported abnormal hormone levels, which, in combination with the age of onset mentioned in the literature, indicate the cycles to be anovulatory in patients with menstrual psychosis. Our patient did not require hormonal treatment, in contrary to previous literature.[8] since she had normal ovulatory cycles, demonstrated by the normal hormone panel and indirectly by the late age of onset. Instead, we successfully treated her with an antipsychotic, which substitutes for the neuroleptic action of estrogen.,[3] especially when the estrogen levels reduce during menses. The lack of estrogenandother gonadal hormone levels during various phases of the menstrual cycle prevents us from labelling this as a confirmed case of menstrual psychosis.[1] In the relapse that happened after the medication discontinuation too, the symptoms wererestricted to the first half of the menstrual cycles. Hence, our initial observation of symptoms occurring only during the first half of the menstrual cycle could not have been an early phase of an otherwise chronic psychotic illness. Even after nine years of onset, the pattern is suggestive of menstrual psychosis. Since it is a rare entity, timely diagnosis andappropriate treatmentcould help reduce morbidity.

Given the sparse literature, there is a definite need for reporting cases of menstrual psychosis for developing operational criteria. This will facilitate in clearly defining the entity of menstrual psychosis, studying its biological correlates and possibly developing specific treatments for it.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brockington I. Menstrual psychosis. World Psychiatry. 2005;4:9–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felthous AR, Robinson DB, Conroy RW. Prevention of recurrent menstrual psychosis by an oral contraceptive. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137:245–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stein D, Blumensohn R, Witztum E. Perimenstrual psychosis among female adolescents: Two case reports and an update of the literature. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2003;33:169–79. doi: 10.2190/6E0C-52XC-GGWQ-DPU4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brockington IF. Menstrual psychosis: A bipolar disorder with a link to the hypothalamus. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13:193–7. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0191-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandra PS. Post-ovariectomy and oestrogen therapy related recurrence of oestrogen withdrawal associated psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106:76. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.t01-2-02001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahé V, Dumaine A. Oestrogen withdrawal associated psychoses. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;104:323–31. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karatepe HT, Işık H, Sayar K, Yavuz F. Menstruation-related recurrent psychotic disorder: A case report. Düşünen Adam J Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 2010;23:282–87. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheinfeld H, Gal M, Bunzel ME, Vishne T. The etiology of some menstrual disorders: A gynecological and psychiatric issue. Health Care Women Int. 2007;28:817–27. doi: 10.1080/07399330701563178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]