Abstract

Background: Individual Placement and Support (IPS) is an evidence-based practice that helps persons with mental and/or physical disabilities, including spinal cord injury, find meaningful employment in the community. While employment is associated with positive rehabilitation outcomes, more research is needed on the impact of IPS participation on non-vocational outcomes, particularly quality of life (QOL). Objective: To identity QOL outcomes experienced with (1) IPS participation and (2) IPS participation leading to employment. Methods: Using a mixed method design, data on quality of life outcomes were collected from 151 interviews and 213 surveys completed by veterans with SCI participating in IPS. Results: At 12 months, participants who obtained competitive employment (CE) and those who did not (no-CE) showed improvement on most measures. In months 12–24, the CE group showed improvements on all study measures while the no-CE group declined on many indices. Statistically significant changes were observed between participants who obtained CE versus no-CE on several measures. Themes were identified from interview data related to productivity and well-being. Productivity themes were (1) contributing to society, (2) earning an income, and (3) maintaining employment. Themes for well-being were (1) mental health/self-confidence, (2) physical health, and (3) goal setting. Themes were associated with IPS participation irrespective of employment outcomes. Conclusion: IPS participants who were competitively employed report consistent improvement in handicap, health-related QOL, and life satisfaction measures across time. Qualitative findings revealed improved QOL outcomes in productivity and well-being for veterans participating in IPS overall, regardless of employment outcomes.

Keywords: handicap, life satisfaction, non-vocational, spinal cord injury, supported employment, veterans, vocational rehabilitation

Quality of life (QOL) is often linked to the World Health Organization's (WHO) definition of health, “A state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely an absence of disease or infirmity,”1 which emphasizes life satisfaction.2 Reduced QOL is associated with having a spinal cord injury (SCI), a life-altering event resulting in impaired movement and sensation with many secondary conditions such as bowel and bladder dysfunction, pain, and spasticity. However, employment after SCI is associated with increased QOL and overall health and financial independence.3,4

The Individual Placement and Support (IPS) model of supported employment is an effective method of helping persons with significant disability find competitive employment (CE) in the community5 based on evidence from 23 randomized clinical trials and several long-term follow-up studies. IPS integrates vocational services with clinical care to rapidly engage people with disabilities in job development to find CE based on their work preferences. Follow-up support services are included to ensure job success. In one study, approximately two-thirds of IPS participants with mental illness obtained CE.6 Similar positive results were demonstrated in a randomized controlled trial of veterans with SCI7 who were randomized to either 12 months of IPS as part of their Veteran Affairs Medical Centers' (VAMC) SCI Center care or conventional vocational rehabilitation. Results showed the rate of CE was 25% for those in the IPS group and only 10% for those in the vocational rehabilitation group.8 In a longitudinal follow-up study with 24 months of IPS, the employment rate was even higher at 43%.9 These studies provide strong support for offering IPS services as part of ongoing SCI care to improve employment outcomes.

While IPS substantially increases CE, few studies have found that IPS alone, that is apart from employment outcomes, has a direct impact on non-vocational QOL over time in persons with severe mental illness or SCI.10,11 Among persons with SCI randomized to either 12 months of IPS or conventional vocational rehabilitation, obtaining CE was associated with increased social integration, mobility, and time spent in productive roles as measured by the Craig Handicap Assessment and Reporting Technique (CHART) but no significant differences were observed for QOL as measured by the Veterans RAND 36-item health survey (VR-36). Additionally, no differences in either handicap or health-related QOL measures were observed between groups participating in IPS or conventional vocational rehabilitation.11 The inability to detect differences in QOL may have been due to the insufficient follow-up time or measurement limitations for the selected instruments. When QOL was calculated as a preference-based utility index (VR-6D), QOL among veterans with SCI participating in a 24-month IPS program increased over time and varied with level of social support in the home.12 Other studies have shown that improvements in economic and life satisfaction increase over time, which indicates longer follow-up periods may be needed to demonstrate change in non-vocational measures.10,11,13,14

This purpose of this study was to examine QOL for veterans with SCI who participated in 24 months of IPS either with or without achieving CE. We used quantitative measures and qualitative interviews from a mixed method, longitudinal study that implemented IPS at seven VAMC SCI Centers to identify perceived changes in QOL.

Methods

The Predictive Outcome Model Over Time for Employment (PrOMOTE) was a prospective multi-site project evaluating longitudinal employment, QOL, and economic outcomes among a cohort of veterans with SCI. The institutional review boards of all sites approved the study, and participants received remuneration as they provided data.

Veterans with SCI receiving health care at seven VAMCs were recruited if they were (1) between the ages of 18 and 65 years old, (2) medically and neurologically stable, (3) enrolled for care in the Veterans Health Administration, and (4) had an SCI. Eligibility to enroll in IPS included meeting additional criteria of (1) not currently competitively employed, (2) expressing a desire to be employed, and (3) living within 100 miles of the VAMC. Veterans with untreated psychosis, untreated alcohol or drug dependence, or a terminal illness were ineligible for IPS. Of 213 participants who met inclusion criteria for IPS and completed the quantitative measures, 151 were interviewed about the impact of IPS on their QOL.

Quantitative measures and employment data were collected in person (0–12 months) and by phone (15–24 months) throughout the study with quarterly follow-up. For quantitative analyses, data at baseline and at 12 and 24 months of IPS were collected on handicap, health-related QOL, and satisfaction with life.

Qualitative interviews were conducted in person using an open-ended, semi-structured format over a 3-year period. The interviews were audio recorded digitally with permission and lasted approximately 1 hour.

Measures

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

Comprised of nine items that rate the frequency of depressive symptoms and signs experienced in the last 2 weeks, this tool was intended to be self-administered and the items are based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders diagnostic criteria. Higher scores indicate increased depression. The overall accuracy with independently derived professional diagnoses is 85%.15

Veterans RAND-36 (VR-36)

With 36 items on health-related QOL, the VR-36 assesses the following eight domains of health and functioning: physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, bodily pain, general health perception, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health. Items are summed with a standard range of 0 to 100, with 100 representing maximum health. Two summary component scores are obtained: physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS). Published internal consistency coefficients have ranged from 0.76 to 0.91 for the subscales.16–19

Craig Handicap Assessment and Reporting Technique (CHART)

This 32-item self-report instrument assesses handicap as described by the WHO.20 The CHART consists of six domains: physical independence, cognitive independence, mobility, occupation, social integration, and economic self-sufficiency. A score of 100 in a domain indicates no handicap. The published test-retest coefficients for the six domains range from 0.80 to 0.95.21

Satisfaction with Life Scale

This 5-item self-report instrument assesses global judgment of satisfaction with life.22 Each item utilizes a 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7), the overall score ranging from 5 to 35. Scores from 15 to 19 indicate slightly dissatisfied, 20 neutrality, and 21 to 25 slightly satisfied. The published coefficient alpha is 0.87, and test-retest reliability coefficient ranges from .50 at 10 weeks to .83 at 2 weeks.23

Interview Guide

The qualitative open-ended, semi-structured interview guide was composed of 24 questions in four sections – an injury narrative (5 questions), participation in IPS (12 questions), social context (3 questions), physical context (3 questions) – and one concluding question. Probes were used as needed throughout the interview.

Analysis

Quantitative

Each measure was scored per developer guidelines. VR-36 utilizes t scores, t (50, 10), for reporting outcomes. Data were explored for departures from normality and detection of outliers. Continuous variables are reported as mean ± SD, and discrete variables are reported as frequency and percent (%). Group comparisons for continuous data were made with Student's t test or Wilcoxon rank sum tests with normal approximation, and for categorical data were made with Pearson's chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, where appropriate. In select instruments changes were assessed using two separate linear repeated measures mixed models with a primary fixed effect (group designation [3 groups] or competitive employment [2 groups]) and participants considered as the nested effect. Data were found to be highly correlated within subjects, and an autoregressive correlation matrix (AR [1]) was chosen as the best fitting matrix. Analyses were performed with SAS.24

Qualitative

Inductive and deductive methods guided the qualitative interview analysis to promote the development of themes. A code book was developed using known constructs and constructs that emerged inductively from the data. A qualitative analysis software program, ATLAS. ti v. 6.2.28,25 was used to code data using a constant comparative approach.26,27 Interrater reliability of at least 80% was established with periodic checks of interrater reliability over time.28 Veterans were grouped according to mutually exclusive employment status during IPS as follows: (1) unemployed at time of interview but later employed per quantitative data (n = 37); (2) employed at time of interview (n = 54); and (3) never employed during IPS (n = 60). Analyses were conducted across all site visits by employment status (unemployed but became employed, employed, never employed). Triangulation, the combination of several research methodologies in the study of the same phenomenon,29 occurred through comparison of themes generated from interview data to findings identified from quantitative measures.

Results

Quantitative

Subject characteristics

Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Participants (N = 213) were majority male with similar ages across employment groups. Most participants were Caucasian or African American, with less than one-half of participants receiving any VA disability benefits and fewer participants receiving service connected benefits for SCI. Less than 10% of the participants received a non-service connected pension.

Table 1.

Participant demographic characteristics at baseline (N = 213)

The CE rate was 43.2%, with 92 participants obtaining CE. To assess for homogeneity between groups, data were stratified by participants obtaining CE versus no-CE. Results indicated CE versus no-CE participants tended to be of similar age, race, and marital status (divorced). Additionally, a similar percentage of CE and no-CE participants received VA benefits, including SC benefits for SCI. However, the CE group received twice the amount of monthly non-SC benefits, but the no-CE group received higher SSI.

Handicap, health-related QOL, and life satisfaction measures

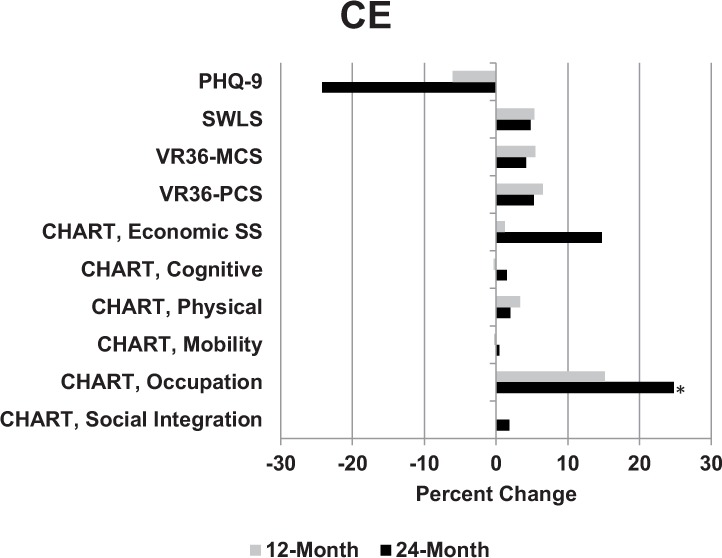

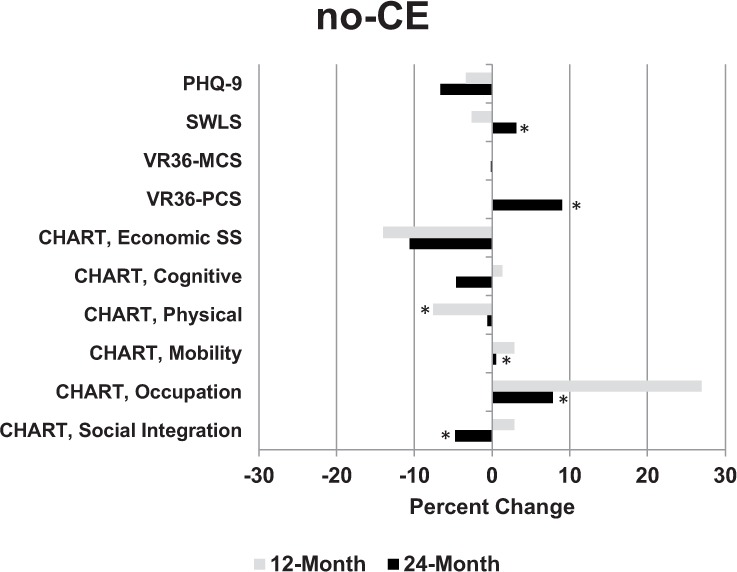

Average scores for both groups for baseline, 12-month, and 24-month assessments are presented in Table 2 and graphically in Figures 1 and 2. At month 12, both groups demonstrated improvement from baseline on most study measures, as evidenced by a positive change in 8 of 10 measured indices for the CE group and 7 of 10 indices for no-CE. At month 24, there was a positive change from baseline in all 10 indices for the CE group versus only 5 of 10 for no-CE. Increases were observed within each study group from baseline to 12 months and 12 to 24 months with the largest changes for both groups observed with the CHART Occupation subscale (CE: baseline to 12 months, +15.2%, and 12 to 24 months, +8.4%; no-CE, +27.0% and −7.8%, respectively). The no-CE showed more variability across time, with many indices showing improvement from baseline to 12 months but a reversal of any growth from 12 months to 24 months. For example, among no-CE participants, CHART Occupation increased 27.0% from baseline to 12 months but declined 15.1% from month 12 to 24. However, for the CE group, all indices continued trending in the same direction from 12 to 24 months as observed for baseline to 12 months.

Table 2.

Handicap, health-related quality of life, life satisfaction, and depression scores for participants by competitive employment status (N = 213)

Figure 1.

Changes in measures over time for the competitive employment (CE) group. Higher values for CHART, VR36, and SWLS indicate improvement; lower values for PHQ-9 indicate improvement. CHART = Craig Handicap and Reporting Technique; MCS = mental component scale; PCS = physical component scale; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire; SWLS = Satisfaction with Life Scale; VR36 = Veterans RAND 36-item health survey. *p ≤ .05.

Figure 2.

Changes in measures over time in the no-competitive employment (no-CE) group. Higher values for CHART, VR36, and SWLS indicate improvement; lower values for PHQ-9 indicate improvement. CHART = Craig Handicap and Reporting Technique; MCS = mental component scale; PCS = physical component scale; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire; SWLS = Satisfaction with Life Scale; VR36 = Veterans RAND 36-item health survey. *p ≤ .05.

Competitive employment, health-related QOL, handicap, and disability

Independent linear mixed models predicted scale scores after adjusting for the effects of time (baseline, 12 months, 24 months), obtained CE (yes/no), and an interaction term for Time × Obtained CE (yes/no) (Table 2). Statistically significant changes were observed between those participants having obtained CE versus no-CE for three CHART subscales (Social Integration [F = 8.86, 1,208; p < .003], Occupation [F =11.89, 1,208; p < .001], and Physical [F = 9.66, 1,202; p < .002]), the VR-36 Physical Component Score (F = 11.85, 1,209; p < .001), and Satisfaction with Life Scale (F = 3.86, 1,208; p < .050). Statistically significant changes between CE and no-CE groups were observed for CHART Occupation (F = 8.67, 1,208; p < .001). The only observed statistically significant Group × Time interaction was for the CHART Occupation subscale (F = 4.30, 1, 282; p < .015).

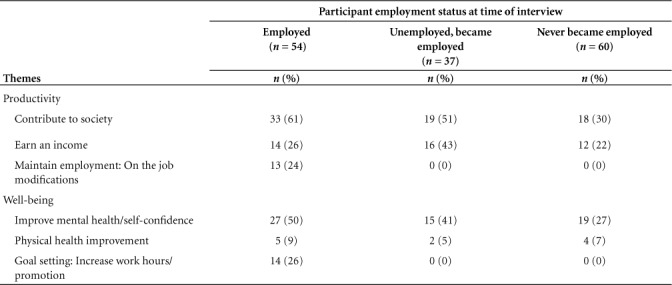

Qualitative

Interviewed veterans described the impact of participating in IPS in terms of productivity, such as physical activities (eg, getting out of the house and earning an income), and well-being, such as mental and general health. In Table 3, the results are presented by employment status at time of interview with the corresponding themes for productivity and well-being. A description of the themes is presented below.

Table 3.

Veteran-identified quality of life outcomes from participating in Individual Placement and Support by type of participant

Productivity

Contribute to society. Veterans thought being part of the program and getting a job would provide them an opportunity to contribute to society or to leave the confines of their home. This theme was the most common across the three types of veterans: 61% of employed at time of interview, 51% of those unemployed at time of interview, and 30% of those never employed. Veterans described wanting to “become a better member of society.” One veteran stated:

I think [IPS] has brought a lot of [pride] to me. I can show my kids, just because I am paralyzed doesn't mean my life ends. It's not about the money obviously, it is about being able to contribute and give something back, you know, to this world.

Earning an income. Veterans talked about the importance of earning an income to be independent and, in some cases, to stop receiving money from the government through Supplemental Security Income (SSI). This was the second most common theme for veterans who were unemployed at time of interview (43%) and the third most common for those employed (26%) or never employed (22%).

Ability to maintain employment and on the job modifications. This theme emerged only for those veterans who were employed at the time of interview (24%). For some employed veterans, workplace accommodations were necessary to complete their job tasks to their satisfaction. To facilitate the identification of needed modifications, the IPS specialist provided ongoing, individualized job supports, one of the key principles of IPS. Often, the IPS specialist would communicate veterans' vocational needs with their clinical team to foster integration of vocational rehabilitation and clinical health care, another key principle of IPS. The combination of a dedicated person providing support after employment and meeting with the veterans' clinical team enabled modifications to be identified and put in place to support continued employment.

Well-being

Improved mental health (self-confidence). A proportion of veterans from all three groups thought their mental health status had improved since being in the program and/or getting a job (employed at time of interview, 50%; unemployed at time of interview, 41%; and never employed, 27%). One veteran thought being in the program gave him “self-concept improvement, decrease in depression, decrease in the need for pain medication because I'm having redirection of the pain and because there's less depression.” Participants in the program often linked mental health improvements to their physical health and described an increase in their self-confidence due to their experiences of going on job interviews and becoming more knowledgeable about finding employment.

Improved physical health. Less than 10% of the veterans from each group described improvements in their physical health because of participating in the SE program (unemployed at time of interview, 5%; employed at time of interview, 9%; and never employed, 7%). One veteran noted that since being in the study program,

I feel better about myself. Well, there's a possibility I could find employment and the more weight I lose, the easier it's going to be for me to move. And, you know, less pain, and everything else. I think it's given me a purpose. I feel it's improved my feeling of self-worth.

Goal setting: increase in work hours/job promotion. This theme emerged only for veterans employed at the time of interview. Employed veterans described that they wanted to work more hours, get promoted so that they could have more responsibility, or switch companies to gain advancement if they did not see a way to advance in their current position. Becoming employed changed their outlook for the future and goal setting.

Discussion

In this mixed methods study of veterans in a 24-month IPS program, changes in handicap, health-related QOL, and life satisfaction measures were observed. These changes were most notable among those who did not obtain employment during the study period. Significant within-group differences in social integration, occupation, mobility, and physical independence are seen in the no-CE group. In many cases, those who did not obtain employment reported improvement in the first 12 months then decreases at 24 months. Although not statistically significant, participants obtaining CE during this 24-month study consistently reported improved physical health and satisfaction with life, which was not reflected among participants in the 12-month study.8 While previous work found significant improvements on select domains of handicap from baseline to 12 months, this study reported consistent, though not statistically significant, improvement across the broad domains of handicap, QOL, and life satisfaction across 24 months and may reflect that a longer follow-up period is necessary to detect clinically meaningful changes on these measures over time.

The quantitative findings showed that participants who became competitively employed during the study showed the most consistent improvement on measures from baseline to 12 months and 12 months to 24 months than individuals who never became competitively employed. No-CE participants showed a positive trend for some of the indices from baseline to 12 months but that trend reversed for some indices from months 12 to 24. These measures indicate that employment may have contributed to steady improvement in QOL. Participants who were not employed showed improvements in QOL during the first year of participation.

The qualitative data found that more participants who obtained CE reported positive changes in QOL than no-CE participants. These study findings are consistent with cross-sectional research showing higher QOL and life satisfaction among people with SCI who are employed.30,31

The most frequently reported improvements among employed participants were in the areas of contributing to society, earning an income, and mental well-being. These findings resonate with other recent qualitative studies exploring the meaning and value of work to people with SCI.32–37 These studies found that people with SCI, whether they are working or not, perceive employment as important for social inclusion, participation, and finding value and identity as a productive member of society. A novel finding from our qualitative data was that veterans with SCI participating in a 24-month IPS program reported experiencing QOL improvements, regardless of employment status. That is, those who were unemployed at time of interview and never employed were represented in every theme except for the two that directly related to being employed (maintaining employment and increasing work hours/promotion). This finding resonates with the no-CE group's improvements on QOL measures seen on quantitative measures in the first 12 months and may be related to activities involved in IPS participation such as goal setting, accessing the community and social networks to explore employment options, and considering one's ability to re-enter the workforce. Since IPS is a highly individualized intervention, the increased support, advocacy, and encouragement of the IPS specialist and possibly increased attention of the treatment team as they focus on employment goals may have also been associated with perceived benefits while on the path to employment even when the goal was not realized during the study. Various studies emphasize the importance of instilling hope and creating positive expectancy to facilitate return to work among people with SCI.38–41 In these studies, such factors have been linked with work force participation for persons with SCI. More research is needed to understand how the specific active components of IPS, whether through increased participation, social support, or hopefulness, help improve QOL among persons with SCI as they seek, obtain, and maintain employment. Returning to work is a complex process where multiple factors interact to impact outcomes.

Limitations and future directions

A potential limitation of this study is the use of self-reported data. Triangulation of findings from multiple data sources to validate responses addresses some of those biases.29 Generalizability to non-veteran and non-SCI populations may be limited. A notable limitation is that the quantitative study measures were not linked chronologically to the time when employment was obtained. That is, CE was classified as yes/no based on whether the participant obtained employment at any point during the 24-month study period, hence drawing conclusions about causality from trends in this data is not possible. Future studies that structure the data to allow more direct examination of the relationship between becoming employed and non-vocational outcomes are needed to further elucidate this relationship. Another future direction to explore is the specific components of IPS that may be associated with improved life satisfaction even apart from obtaining a job. Then too, studies are needed among the SCI population that examine factors that predict positive IPS outcomes, either in terms of employment or QOL.

Conclusion

This mixed method study examined QOL among veterans with SCI participating in IPS for 24 months. The study showed that IPS participants who become employed report consistent improvement in handicap, health-related QOL, and life satisfaction measures. Participation in an IPS program can also be associated with some perceived improvement in QOL, particularly mental well-being. Further research is needed to understand the effect on participants in employment programs who do not become employed to identify strategies or practices to retain improvements in QOL experienced during the first year.

Acknowledgments

This material is based on work supported by the Office of Research and Development, Rehabilitation Research and Development Service, Department of Veterans Affairs, VA RR&D grant O7824R.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization Constitution of the World Health Organization-Basic Documents. (45th ed.) 2006 Oct;(Supplement) http://www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_en.pdf.

- 2.Fayers PM, Machin D. Quality of Life: The Assessment, Analysis and Interpretation of Patient-Reported Outcomes. 2nd ed. Wiley; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson D, Dummont S, Azzaria L, Bourdais ML, Noreau L. Determinants of return to work among spinal cord injury patients: A literature review. J Vocat Rehabil. 2007;27:57–68. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meade MA, Reed KS, Saunders LL, Krause JS. It's all of the above: Benefits of working for individuals with spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2015;21(1):1–9. doi: 10.1310/sci2101-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mueser KT, Drake RE, Bond GR. Recent advances in supported employment for people with serious mental illness. Curr Opin Psychiatr. 2016;29(3):196–201. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bond GR, Drake RE, Becker DR. An update on randomized controlled trials of evidence-based supported employment. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2008;31(4):280–290. doi: 10.2975/31.4.2008.280.290. doi: 10.2975/31.4.2008.280.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ottomanelli L, Goetz L, McGeough C et al. Methods of a multisite randomized clinical trial of supported employment among veterans with spinal cord injury. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46:919–930. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2008.10.0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ottomanelli L, Goetz LL, Suris A et al. Effectiveness of supported employment for veterans with spinal cord injuries: Results from a randomized multisite study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:740–747. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ottomanelli L, Goetz LL, Barnett SD et al. Individual placement and support in spinal cord injury: A longitudinal observational study of employment outcomes. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(8):1567–1575.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kukla M, Bond GR. A randomized controlled trial of evidence-based supported employment: Nonvocational outcomes. J Vocat Rehabil. 2013;38:91–98. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ottomanelli L, Barnett SD, Goetz LL. A prospective examination of the impact of a supported employment program and employment on health related quality of life, handicap, and disability among Veterans with SCI. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(8):2133–2141. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0353-5. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0353-5. SCI-VIP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutton BS, Ottomanelli L, Njoh E, Barnett SD, Goetz LL. The impact of social support at home on health-related quality of life among veterans with spinal cord injury participating in a supported employment program. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:1741–1747. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0912-4. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0912-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krause JS. Longitudinal changes in adjustment after spinal cord injury: A 15-year study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992;73(6):564–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krause JS, Coker JL. Aging after spinal cord injury: A 30-year longitudinal study. J Spinal Cord Med. 2006;29(4):371–376. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2006.11753885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kazis LE, Ren XS, Lee A et al. Health status in VA patients: Results from the Veterans health study. Am J Med Qual. 1999;14(1):28–38. doi: 10.1177/106286069901400105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kazis LE, Lee A, Spiro A et al. Measurement comparisons of the medical outcomes study and veterans SF-36 health survey. Health Care Financ Rev. 2004;25(4):43–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kazis LE, Miller DR, Clark JA et al. Improving the response choices on the veterans SF-36 health survey role functioning scales: Results from the Veterans Health Study. J Ambul Care Manage. 2004;27(3):263–280. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200407000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kazis LE, Miller DR, Skinner KM et al. Applications of methodologies of the Veterans health study in the VA healthcare system: Conclusions and summary. J Ambul Care Manage. 2006;29(2):182–188. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200604000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE et al. Implementing supported employment as an evidence-based practice. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(3):313–322. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.3.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whiteneck GG, Charlifue SW, Gerhart KA, Overholser JD, Richardson GN. Quantifying handicap: A new measure of long-term rehabilitation outcomes. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992;73(6):519–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Becker D, Drake RE. Supported employment interventionsareeffectiveforpeoplewithseveremental illness. Evid Based Mental Health. 2006;9(1):22. doi: 10.1136/ebmh.9.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pavot W, Diener E. Review of the Satisfaction With Life Scale. Psychol Assess. 1993;5(2):164–172. [Google Scholar]

- 24.SAS, Version 9.4. Cary, NC: SAS Inc.; [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scientific Software. ATLAS.ti version 6.2.28 [Computer software] Berlin: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huberman MA, Miles MB. The Qualitative Researcher's Companion. London: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bogdan RC, Biklen SK. Qualitative Research in Education: An Introduction to Theory and Methods. Columbus, OH: Allyn & Bacon; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leduc BE, Lepage Y. Health-related quality of life after spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24(4):196–202. doi: 10.1080/09638280110067603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hess D, Meade M, Forchheimer M, Tate D. Psychological well-being and intensity of employment in individuals with a spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2004;9(4):1–0. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leiulfsrud AS, Ruoranen K, Ostermann A, Reinhardt JD. The meaning of employment from the perspective of persons with spinal cord injuries in six European countries. Work. 2016;55(1):133–144. doi: 10.3233/WOR-162381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leiulfsrud AS, Reinhardt JD, Ostermann A, Ruoranen K, Post MW. The value of employment for people living with spinal cord injury in Norway. Disabil Soc. 2014;29(8):1177–1191. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hay-Smith EJ, Dickson B, Nunnerley J, Anne Sinnott K. “The final piece of the puzzle to fit in”: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the return to employment in New Zealand after spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(17):1436–1446. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.737079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meade M, Reed K, Saunders L, Krause J. It's all of the above: benefits of working for individuals with spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2015;21(1):1–9. doi: 10.1310/sci2101-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nunnerley JL, Hay-Smith EJ, Dean SG. Leaving a spinal unit and returning to the wider community: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(14):1164–1173. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.723789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leiulfsrud A, Reinhardt JD, Ostermann A, Ruoranen K, Post MW. The value of employment for people living with spinal cord injury in Norway. Disabil Soc. 2014;29(8):1177–1191. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krause JS, Pickelsimer E. Relationship of perceived barriers to employment and return to work five years later: A pilot study among 343 participants with spinal cord injury. Rehabil Counsel Bull. 2008;51(2):118–121. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blake J, Brooks J, Greenbaum H, Chan F. Attachment and employment outcomes for people with spinal cord injury: The intermediary role of hope. Rehabil Counsel Bull. 2017;60(2):77–87. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schönherr MC, Groothoff JW, Mulder GA, Schoppen T, Eisma WH. Vocational reintegration following spinal cord injury: Expectations, participation and interventions. Spinal Cord. 2004;42(3):177–184. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bergmark L, Westgren N, Asaba E. Returning to work after spinal cord injury: Exploring young adults' early expectations and experience. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(25–26):2553–2558. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.579224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]