Key Teaching Points.

-

•

Seizure-induced (ictal) asystole is caused by direct vagal stimulation of the cardiac conduction system. It is estimated that only 0.27% of epileptic patients suffer from the condition, which is hypothesized as one of many potential mechanisms of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy.

-

•

Several approaches are proposed to treat ictal asystole, including adjustment of antiepileptic drugs, epilepsy surgery, and, only recently, permanent pacemaker implantation.

-

•

Cardioneuroablation—parasympathetic denervation of the sinus node—might represent a new treatment option in select patients with ictal asystole. In addition, with this treatment option permanent pacemaker implantation could be avoided and device-related complications prevented.

Introduction

We describe a case of successful parasympathetic denervation of the sinus node using cardioneuroablation in a patient with right temporal lobe epilepsy and prolonged ictal asystole. The procedure abolished seizure-induced bradyarrhythmia occurrence and converted the patient’s dramatic seizures with severe cerebral hypoperfusion into short focal seizures with minimal motor signs. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a successful cardioneuroablation procedure to potentially treat ictal asystole.

Case report

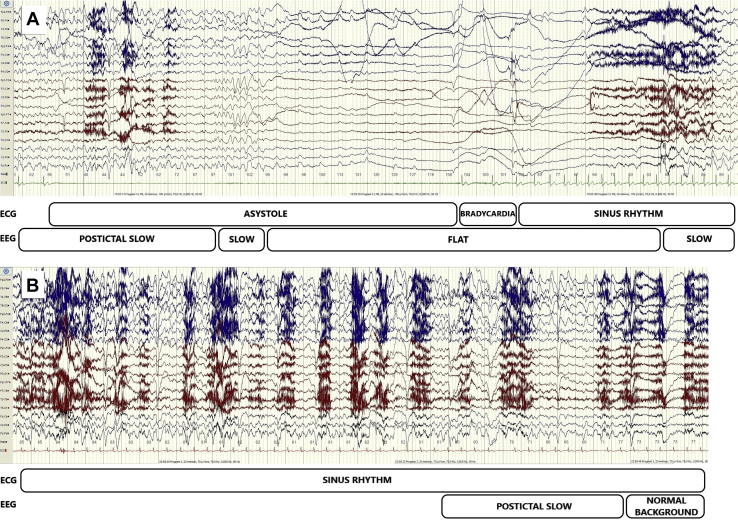

A 43-year-old right-handed male patient with pharmacoresistant focal epilepsy was admitted to the Department of Neurology for evaluation before potential epilepsy surgery. He had an extensive focal cortical dysplasia in the right temporal lobe and mild left-sided spastic hemiparesis. Seizures were resistant to several antiepileptic drugs, including levetiracetam and carbamazepine in maximal dosages he was taking before the admission. For the past 5 years, almost every seizure resulted in loss of consciousness, falls, and, on several occasions, traumatic injuries. During long-term video-electroencephalography (EEG) monitoring, the antiepileptic drugs were temporarily withdrawn, and 9 epileptic seizures were recorded. The seizures manifested with ictal pouting (“chapeau de gendarme”), right leg automatisms and subtle pelvic movements, and dystonic left hand posturing, followed by unresponsiveness, upward gaze deviation, and posturing resembling a decerebration pattern. In EEG, focal ictal activity started in the right temporal region, quickly evolving over both hemispheres, and was then followed by postictal EEG slowing over the right hemisphere. Unexpectedly, in the late postictal period we observed generalized EEG flattening and slowing, indicative of cerebral hypoperfusion. Simultaneously, on electrocardiography sinus heart rate slowing with asystole lasting up to 25 seconds was recorded, resulting in the patient’s syncope (Figure 1A, Supplemental Video).

Figure 1.

Electroencephalography (EEG) and electrocardiography (ECG) changes occurring 35 seconds after the start of the seizure before and after cardioneuroablation procedure. A: Before the procedure, single-channel ECG demonstrated sinus rhythm slowing followed by asystole (23 seconds) and then a slow return to normal sinus rhythm. In postictal EEG with slow activity over the right hemisphere, the cerebral hypoperfusion resulted in generalized slow activity, followed by a “flat” EEG (22 seconds) and then generalized slow activity. B: After the procedure, single-channel ECG demonstrated normal sinus rhythm. In EEG, postictal slow activity over the right hemisphere abruptly returned to normal background activity.

Immediate surgical treatment of epilepsy was not feasible and also, considering the extensive nature of the presumed epileptogenic lesion, chances of favorable epilepsy surgery outcome were estimated to be low. The cardiology team was consulted. Since asystole after the seizure onset was suggestive of an increased direct vagal stimulation of the cardiac conduction system, we decided to try cardioneuroablation as an alternative to permanent pacemaker implantation.

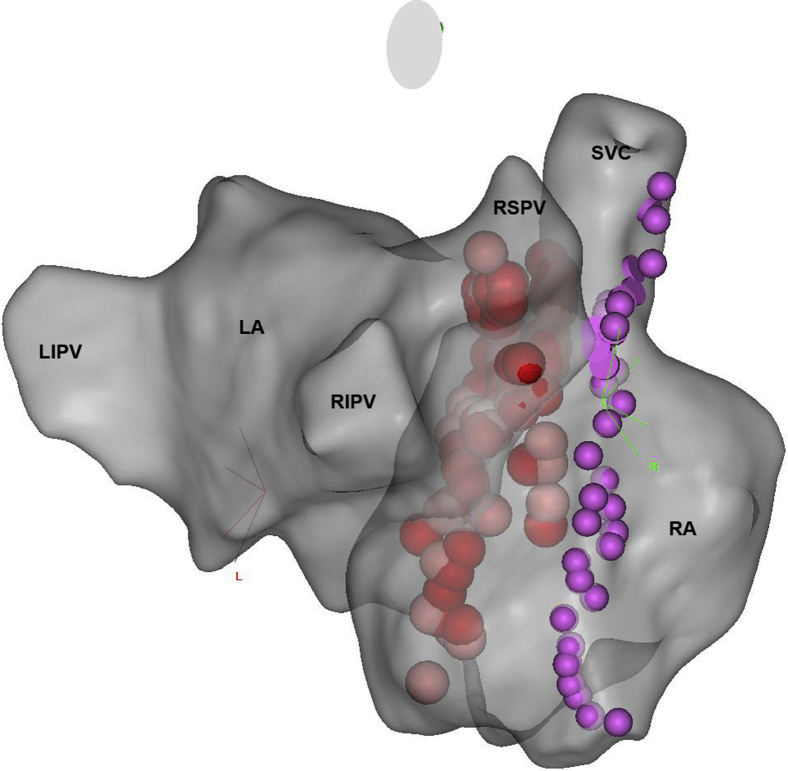

After the patient’s consent, the cardioneuroablation procedure was performed using mild sedation with midazolam and additional fentanyl boluses. Mapping and ablations were performed using a 3.5-mm irrigated-tip catheter (Navistar ThermoCool SmartTouch, Biosense Webster, Diamond Bar, CA). Initially, 3-dimensional virtual anatomy of the right (RA) and left atrium (LA) was created using the CARTO 3 fast anatomic mapping system (Biosense Webster, Diamond Bar, CA), facilitated by intracardiac echocardiography (AcuNav, Siemens Medical Solutions, Mountain View, CA). Tagging the phrenic nerve capture points on the lateral RA allowed us to map the nerve course (Figure 2). Afterwards, the electrogram fractionations indicative of epicardial ganglia presence1 were mapped and tagged in the anatomic areas where epicardial parasympathetic ganglia for sinus and atrioventricular node innervation are located (anteriorly and superiorly to the right superior pulmonary vein [RSPV] and anteriorly to the right inferior pulmonary vein in LA). These locations correspond to locations on the posterior septal side of the RA, where fractionated electrograms were also mapped and tagged. Multiple ablations (power control, 25 W in RA, 30 W in LA, target contact force 10–30 g, duration up to 40 s, temperature limit 43°C, total radiofrequency time 1544 s) were performed in target areas from both the LA and RA, with care taken to avoid ablations in the proximity of the mapped course of the phrenic nerve. We aimed to achieve local electrogram attenuation and ablation index (Biosense Webster, Diamond Bar, CA) of 350 to 500. During initial ablations anteriorly to the RSPV, increase in heart rate was noticed, indicating parasympathetic denervation of the sinus node. Later ablations more inferiorly along the posterior interatrial septum from the LA and RA were anatomically guided. After no additional increase in heart rate was achieved with further ablations and target anatomic area was sufficiently densely ablated, the procedure was terminated. Atropine test (3 mg of atropine sulfate given intravenously; dose calculated as 0.04 mg/kg body weight, maximal dose 3 mg) at the end of the procedure resulted in only 7% sinus rate increase (from 117 beats/min to 125 beats/min), which according to published data2 suggests successful denervation of the sinus node. The procedure duration was 200 minutes; fluoroscopy time was 6.8 minutes (dose-area product 560 μGym2).

Figure 2.

A posterolateral view of 3-dimensional constructed virtual anatomy of the left and right atrium. Red dots designate radiofrequency ablation lesions on the interatrial septum. Violet dots show the phrenic nerve course. LA = left atrium; LIPV = left inferior pulmonary vein; RA = right atrium; RIPV = right inferior pulmonary vein; RSPV = right superior pulmonary vein; SVC = superior vena cava.

To evaluate the impact of cardioneuroablation on bradyarrhythmia occurrence, an implantable loop recorder (ILR; Reveal Linq, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) was implanted. The patient resumed antiepileptic drugs and was released from the hospital.

One month after the procedure, the patient had a seizure without loss of consciousness, reporting only lightheadedness and stiffness of his left arm. Interrogation of the ILR showed no bradyarrhythmias at the time of the seizure. The patient was then readmitted for follow-up video-EEG monitoring and the antiepileptic drugs were again withdrawn. Five seizures were recorded. All of the recorded seizures ended with a short postictal EEG slowing over the right hemisphere, followed by rapid restoration of normal background activity (Figure 1B). There were no bradyarrhythmias recorded during the seizures. He is still under evaluation for epilepsy surgery, but at present his seizures have a minor impact on his quality of life. During the 6-month follow-up period the patient reported no syncope and there were no bradyarrhythmias recorded by the ILR.

Discussion

Seizure-induced asystole, or ictal asystole, is caused by spread of ictal activity to loci where it intervenes with central autonomic networks, which can result in direct vagal stimulation of the cardiac conduction system. This rare but devastating condition is a feature of focal, most commonly temporal and mesial frontal lobe epilepsy involving insula, cingulate gyrus, and other parts of the central autonomic network.3, 4, 5, 6 It is estimated that only 0.27% of epileptic patients suffer from the condition, which is hypothesized as one of many potential mechanisms of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy.7, 8, 9, 10 Several approaches are proposed to treat ictal asystole, including adjustment of antiepileptic drugs, epilepsy surgery for medically refractory patients, and, only recently, permanent pacemaker implantation.8 However, despite the technological development of implantable electronic cardiac devices, complication incidence in modern pacing therapy is still substantial. Although most adverse events occur in the early postimplantation period (lead-related), complication rates during long-term follow-up are not scarce, ranging from 7.5% to almost 10% of the patients.11, 12

Pachon and colleagues13 first described cardioneuroablation in 2005 as a new treatment modality for neurocardiogenic syncope, functional sinus node dysfunction, and functional atrioventricular block. The technique is based on radiofrequency ablation of main epicardial parasympathetic ganglia in the heart. With this procedure partial parasympathetic denervation of the sinus and/or atrioventricular node is achieved and consequently the adverse parasympathetic influence on the heart diminished. Long-term follow-up2 of patients undergoing cardioneuroablation procedure for cardioinhibitory neurocardiogenic syncope showed very promising results, with only 3 patients out of 43 experiencing recurrent syncope. In addition, postprocedure 24-hour Holter electrocardiograms and stress tests showed no major abnormalities except mildly elevated basal heart rate.

Although the cardioneuroablation procedure considerably diminished the patient’s seizure presentation, longer follow-up and close monitoring of the patient are required to detect possible recurrence of bradyarrhythmias and worsening of seizures. Consequently, pharmacoresistant epilepsy merits constant evaluation for potential surgical treatment.

Conclusion

Cardioneuroablation might represent a new treatment modality in select pharmacoresistant patients with ictal asystole. In addition, with this treatment option permanent pacemaker implantation could be avoided and device-related complications prevented. Further research is warranted to evaluate this treatment option.

Footnotes

Informed consent was obtained from the patient before performing the procedure.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrcr.2018.07.018.

Appendix. Supplementary data

Video and scalp EEG recording of a seizure before successful treatment with cardioneuroablation (left pane, October 16, 2017, 5:45 PM), and after (right pane, February 7, 2018, 7:11 AM). Green ribbon mark on the EEG indicates obvious EEG seizure activity.

References

- 1.Lellouche N., Buch E., Celigoj A., Siegerman C., Cesario D., De Diego C., Mahajan A., Boyle N.G., Wiener I., Garfinkel A., Shivkumar K. Functional characterization of atrial electrograms in sinus rhythm delineates sites of parasympathetic innervation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1324–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pachon J.C., Pachon E.I., Cunha Pachon M.Z., Lobo T.J., Pachon J.C., Santillana T.G. Catheter ablation of severe neurally meditated reflex (neurocardiogenic or vasovagal) syncope: cardioneuroablation long-term results. Europace. 2011;13:1231–1242. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuele S.U., Bermeo A.C., Alexopoulos A.V., Locatelli E.R., Burgess R.C., Dinner D.S., Foldvary-Schaefer N. Video-electrographic and clinical features in patients with ictal asystole. Neurology. 2007;69:434–441. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000266595.77885.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghearing G.R., Munger T.M., Jaffe A.S., Benarroch E.E., Britton J.W. Clinical cues for detecting ictal asystole. Clin Auton Res. 2007;17:221–226. doi: 10.1007/s10286-007-0429-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rocamora R., Kurthen M., Lickfett L., Von Oertzen J., Elger C.E. Cardiac asystole in epilepsy: clinical and neurophysiologic features. Epilepsia. 2003;44:179–185. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.15101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lanz M., Oehl B., Brandt A., Schulze-Bonhage A. Seizure induced cardiac asystole in epilepsy patients undergoing long term video-EEG monitoring. Seizure. 2011;20:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Velagapudi P., Turagam M., Laurence T., Kocheril A. Cardiac arrhythmias and sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2012;35:363–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2011.03276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wittekind S.G., Lie O., Hubbard S., Viswanathan M.N. Ictal asystole: an indication for pacemaker implantation and emerging cause of sudden death. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2012;35:e193–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2011.03179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nashef L., Hindocha N., Makoff A. Risk factors in sudden death in epilepsy (SUDEP): the quest for mechanisms. Epilepsia. 2007;48:859–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scorza F.A., Arida R.M., Cysneiros R.M., Terra V.C., Sonoda E.Y., de Albuquerque M., Cavalheiro E.A. The brain-heart connection: implications for understanding sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Cardiol J. 2009;16:394–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellenbogen K.A., Hellkamp A.S., Wilkoff B.L., Camunãs J.L., Love J.C., Hadjis T.A., Lee K.L., Lamas G.A. Complications arising after implantation of DDD pacemakers: the MOST experience. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:740–741. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00844-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Udo E.O., Zuithoff N.P., van Hemel N.M., de Cock C.C., Hendriks T., Doevendans P.A., Moons K.G. Incidence and predictors of short- and long-term complications in pacemaker therapy: the FOLLOWPACE study. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:728–735. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pachon J.C., Pachon E.I., Pachon J.C., Lobo T.J., Pachon M.Z., Vargas R.N., Jatene A.D. “Cardioneuroablation”--new treatment for neurocardiogenic syncope, functional AV block and sinus dysfunction using catheter RF-ablation. Europace. 2005;7:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.eupc.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video and scalp EEG recording of a seizure before successful treatment with cardioneuroablation (left pane, October 16, 2017, 5:45 PM), and after (right pane, February 7, 2018, 7:11 AM). Green ribbon mark on the EEG indicates obvious EEG seizure activity.