Abstract

The use of silver nanoparticles (AgNP) raises safety concerns during susceptible life stages such as pregnancy. We hypothesized that acute intravenous exposure to AgNP during late stages of pregnancy will increase vascular tissue contractility, potentially contributing to alterations in fetal growth. Sprague Dawley rats were exposed to a single dose of PVP or Citrate stabilized 20 or 110 nm AgNP (700 μg/kg). Differential vascular responses and EC50 values were observed in myographic studies in uterine, mesenteric arteries and thoracic aortic segments, 24 hours post-exposure. Reciprocal responses were observed in aortic and uterine vessels following PVP stabilized AgNP with an increased force of contraction in uterine artery and increased relaxation responses in aorta. Citrate stabilized AgNP exposure increased contractile force in both uterine and aortic vessels. Intravenous AgNP exposure during pregnancy displayed particle size and vehicle dependent moderate changes in vascular tissue contractility, potentially influencing fetal blood supply.

Keywords: silver nanoparticles, pregnancy, nanotoxicology, thoracic aorta, mesenteric artery, uterine artery, wire myography

1. Introduction

Engineered silver nanoparticles (AgNP) are increasingly used in many consumer applications including food, clothing and infant products (1, 2). They have also been developed and used in various biomedical applications including intravenous (IV) catheters, orthopedic bone cement, surgical mesh, vascular stents and wound dressings (3). The inherent antimicrobial, antiviral and anti-inflammatory properties of AgNP underlies their utility in medical (3) and household products (1, 2). However, some applications may lead to increased exposure followed by distribution and/or accumulation within the human body, raising concerns regarding their safety, particularly in susceptible life stages such as pregnancy, which may affect intrauterine fetal growth.

Silver nanoparticles are engineered in various sizes or forms and formulated with various carrier molecules to increase their stability, biocompatibility and versatility. As a result, any differential tissue accumulation/distribution by varying size or coatings of AgNP (4, 5), and the resultant silver ion dissolution or intracellular aggregation/precipitation (5–10) may contribute to differential tissue responses.

Inhalational exposure to AgNP (9–13) suggests cellular inflammatory responses with persistent silver accumulation in immune cell or surrounding tissue, but were not examined for impact on life stage. However, changes in vascular tissue responses are reported with other metal based (nickel hydroxide and nano-TiO2) nanoparticle exposure studies in both pregnant (14) and non-pregnant (15, 16) life stages. In addition, aerosol exposure to nano-sized titanium dioxide during gestation negatively impacted cardiac function, mitochondrial respiration and bioenergetics in the progeny (17). The direct in vitro exposure of human bronchial epithelial cells to PVP coated AgNP was reported to induce DNA damage as assessed by the comet assay (18), suggesting that in vivo exposure may also be associated with detrimental changes in the target tissue or organ function. Current evidence on AgNP distribution suggests that following oral/intragastric delivery, AgNP or silver ion can be distributed to different organs including liver and kidneys through absorption from the vascular compartment (19, 20), as well as accumulation in the placenta and fetuses during pregnancy (21). However, consensus on overt toxicity from these studies is far from clear as it is suggested that the form of silver within the biological medium may be important in rendering any effect (20, 22–26).

There are reported gender related differences in the distribution and biokinetics of intravenously administered 15 nm AgNP (27). The distribution in blood, liver and bone marrow of AgNP following intravenous injection in a mouse model, revealed cytotoxic and oxidative stress responses that varied with the dose, size and coating on AgNP (28). The reported distribution of various sized AgNP during pregnancy are mainly to maternal organs including liver, spleen and lung following IV exposure (29). Silver particles were detected in the fetal yolk sac, suggesting potential distribution in the fetal circulation affecting fetal growth and development. In addition, other studies with intravenous silica and titanium nanoparticle exposures during pregnancy have identified fetal abnormalities (30). Recent studies with intravenously administered PVP formulated 20 nm and 110 nm AgNP have shown particle size dependent maternal deposition in the spleen/liver as well as feto-maternal transfer. While silver was detected in fetuses, relatively higher concentrations were detected in the placentae (21). Largely, reproductive and developmental toxicity effects have been reported in many studies via different routes of maternal exposure to various forms of AgNP resulting in differential tissue distribution (21, 26, 31) all possibly trafficking through the vascular system.

During the distribution and excretion process, the vascular endothelium and underlying smooth muscle are potential targets of the silver exposure. The ex vivo exposure to 45 nm AgNP has been reported to increase vasoconstriction in isolated male rat aortic rings and in vitro exposure is associated with alterations in the availability of nitric oxide in coronary endothelial cells (32). The reported AgNP mediated changes of vascular tissue contractile properties and alterations in the uterine blood supply during gestation would suggest a potential negative affect on fetal development. Previous studies from our laboratory with intravenous exposure to fullerenes (C60) and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT) have reported nanoparticle and vehicle/suspension medium dependent changes in vascular tissue contractility in pregnancy, that may impact fetal growth (33, 34).

The current study focuses on such changes with AgNP exposure, a nanoparticle with physicochemical properties different from carbon based nanotubes, but with reported differential effects on cardiac injuries studied previously via pulmonary exposure (35). We hypothesized, intravenous exposure to AgNP during pregnancy will increase vascular tissue contractility, potentially contributing to a reduction in fetal growth. Variable contraction/relaxation effects between the uterine artery, mesenteric artery and thoracic aorta would accompany this response, dependent on the size and formulation of AgNP. We used two AgNP formulations, stabilized with PVP or citrate, of either 20 nm or 110 nm diameter size in an effort to elucidate any size and/or stabilization-vehicle dependent effects of commonly formulated AgNP on blood vessel responses following an acute exposure during pregnancy.

2. Methods

2.1 Silver nanoparticle formulations for exposure

20 and 110 nm spherical AgNP stabilized in citrate or polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), as produced by NanoComposix (San Diego, CA), were procured through the NIEHS Centers for Nanotechnology Health Implications (NCNHIR). Additional, independent characterization of the materials was performed by The Nanotechnology Characterization Laboratory (SAIC-Fredrick, Frederick, MD) (4, 36). Average values from that characterization including: silver content, core diameter by transmission electron microcopy (TEM), hydrodynamic diameter by dynamic light scattering (DLS), zeta potential and endotoxin content are reported in Table 1. The vehicle controls (stabilizing agents) were 2 mM citrate buffer or polyvinylpyrrolidone (pH 7.5), at the same concentration used for the AgNP suspensions, so that effects of the stabliizers could be separated from AgNP effects. Citrate buffer was prepared using sodium citrate (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) in endotoxin free ultra-pure distilled water (37). Four colloidal silver nanoparticle formulations were used for intravenous (IV) exposure studies, and will be referred to as indicated in parentheses; 20 nm, citrate-stabilized colloidal silver (20 nm AgNP/citrate), 20 nm, PVP (polyvinylpyrorrolidone)-stabilized colloidal silver (20 nm AgNP/PVP), 110 nm, citrate-stabilized colloidal silver (110 nm AgNP/citrate) and 110 nm, PVP-stabilized colloidal silver (110 nm AgNP/PVP). The citrate-stabilized particles were supplied in 2 mM citrate buffer and the PVP-stabilized particles were supplied in ultra- pure water with 1.4 % PVP and a silver concentration of 1 mg/ml, in sealed 50 ml aliquots. The detailed characterization of 10, 25 and 50 ml aliquots of these particle suspensions were completed by the Nanotechnology Characterization Laboratory, National Cancer Institute at Frederick (SAIC-Frederick, Inc., Frederick, MD, USA) as reported in the Initial Characterization Data for NCNHIR Silver ENMs (36, 38). The size and shape of the AgNP were confirmed via transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Hitachi H7600). Size distribution analysis was performed using the freeware software Image J. A minimum of 100 particles per sample were counted by randomly surveying the entire TEM grid from multiple high magnification images. Image J was used to determine both area and Feret diameters (38). Prior to their use, all suspensions were sonicated three times for 15 s using a Misonix ultrasonic liquid processor at 65% amplitude at a total energy output of 10,817 joules (Model 1510R-MTH, Branson Ultrasonics Corp. Danbury, CT, USA). The silver suspensions were vortexed for 10 s in between sonication and prior to administration. These suspensions were stored at 4 ºC in the dark between exposures and all particle handling procedures were done in a biological safety cabinet to ensure sterility.

Table 1.

AgNP characterization.

| AgNP formulation | Silver Concentration by ICP- MS (mg/g) | Core Diameter by TEM (nm) | Hydro dynamic Diameter by DLS, Z-Avg (nm) | Zeta Potential (mV) | Endotoxin Concentration (EU/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

20 nm AgNP/PVP (20 nm, PVP stabilized silver) |

1.1 | 20.5 | 30.1 | −28.9 | < 2.2 |

|

110 nm AgNP/PVP (110 nm, PVP stabilized silver) |

1.1 | 111.3 | 119.0 | −23.2 | < 0.5 |

|

20 nm silver/citrate (20 nm, citrate stabilized silver) |

1.1 | 20.3 | 26.7 | −35.2 | < 0.03 |

|

110 nm silver/citrate (110 nm, citrate stabilized silver) |

1.0 | 111.5 | 106.7 | −46.8 | < 0.03 |

The characterization details of the nanoparticles used in this study, as reported in the Initial Characterization Data for NCNHIR Silver ENMs, by the Nanotechnology Characterization Laboratory. The citrate-stabilized particles were supplied in 2 mM citrate buffer and the PVP-stabilized particles were supplied in water (36).

DLS = Dynamic Light Scattering

ICP-MS = Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry

TEM = Transmission Electron Microscopy

2.2 Sprague Dawley rats

Timed pregnant female Sprague Dawley rats, 10–12 weeks of age were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (USA). The rats arrived in the East Carolina University (ECU) Department of Comparative Medicine’s animal facility between 9 and 12 days of gestation (GD). The exact GD was provided by the vendor for each dam on its arrival. Animals were allowed to acclimate for one week, housed individually, under 12 hour light/dark cycles with standard rat chow and water provided ad libitum prior to exposure to the AgNP suspension. The body weight was monitored every three days to assess the progression of pregnancy. All animal handling, exposure and sacrifice procedures were approved by the ECU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.3 Exposure to silver nanoparticles

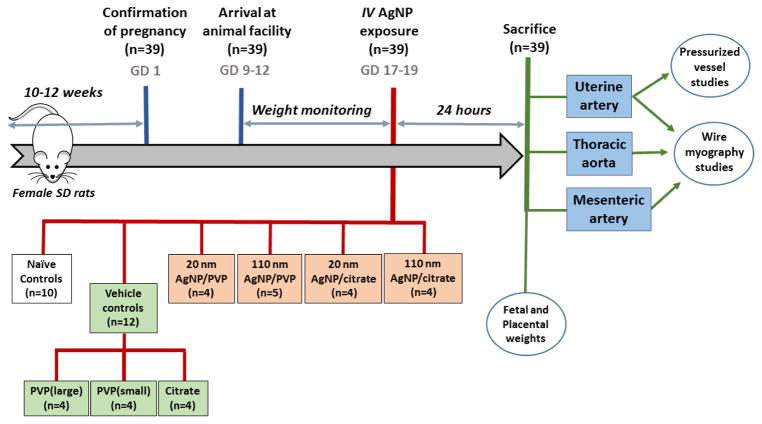

A graphical representation of the experimental design for AgNP exposure and vascular segment studies is presented in Figure 1. Thirty nine pregnant rats were included in the study results. Ten rats (between GD 17–19) were randomly selected as naïve controls. Twelve rats in vehicle controls (8 rats for PVP, with 4 for each molecular weight formulation and 4 rats for citrate) and 18 rats were included in four exposure groups (minimum of 4 rats for each exposure; 20 nm AgNP/citrate, 110 nm AgNP/citrate, 20 nm AgNP/PVP and 110 nm AgNP/PVP) for the study. There was at least 1 randomly selected animal for each GD included in each vehicle and AgNP exposure group.

Figure 1. Graphical representation of the experimental design.

Graphical representation illustrating the chronological events, measured outcomes and the representative experimental groups of exposures to intravenous silver nanoparticles, vehicle controls or naïve pregnant dams. AgNP = silver nanoparticles, GD = gestational day, IV = intravenous, PVP = polyvinylpyrorrolidone and SD = Sprague Dawley.

Once the pregnant rats reached 17–19 days of gestation, they were anesthetized using 2 – 3% isoflurane (Webster Veterinary, USA) dispersed in oxygen for all exposure procedures. Each rat was administered a single dose of 20 or 110 nm AgNP stabilized with either PVP or citrate (200 μg, i.e. 200 μl of stock 1 mg/ml suspension), by intravenous administration through the tail vein using a 25G needle to mimic a direct, acute exposure of the vascular system to AgNP. This mass based dose of 200 μg/rat we administered was approximately 701.75 μg/kg, considering the mean weight of 285 g for the pregnant rats. Extrapolating this dose to a human exposure with a 70 kg female would equate to 4.9 mg of acute exposure. The choice of intravenous administration of the AgNP was in part influenced by the decision of the executive members of the NIEHS Centers for Nanotechnology Health Implications (NCNHIR). As members of the consortium, we were charged to investigate responses to inhalation/instillation, oral gavage and intravenous routes of exposure of a known set of nanomaterials.

PVPs used for stabilizing the 20 and 110 nm AgNP were provided by the manufacturer and 200 μl of a 1.4% in ultra-pure distilled water was administered intravenously as vehicle controls for PVP stabilized AgNP). The choice of two different molecular weight PVP polymers was an efforts to utilize a stabilizing agent that would match the physical sizes of particle in an effort to ensure similar uniform particle coating conditions. A 2 mM citrate (Sigma- Aldrich, St Louis, MO) solution was made using ultra-pure distilled water and 200 μl was injected as the vehicle control for citrate stabilized AgNP.

2.4 Dissection and isolation of vessel segments

Twenty-four hours following administration of the AgNP or vehicle, the rats were anesthetized in a transparent sealed receptacle containing gauze soaked with 70% isoflurane (Webster Veterinary, USA) in propylene glycol (Amersco, OH, USA). Within the receptacle, the isoflurane soaked gauze was separated from the animal using a wire-mesh. After reaching plane 3 - deep anesthesia, a nose-cone was used to maintain the anesthesia throughout the remaining procedure. Anesthetized rats were subjected to a midline incision and the pleural cavity opened, to create a pneumothorax. The midline incision was extended to the lower abdominal cavity and both uterine horns with vascular arcades were carefully excised. These tissues were placed in ice cold physiological saline solution (PSS; mM) 140 NaCl, 0 KCl, 1.6 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 MOPS (3-[N-morpholino]-propane sulfonic acid), 6 D-glucose, 0.02 EDTA, and a pH of 7.4). The small intestinal loop with superior mesenteric arcade was carefully excised and placed in PSS. The midline incision was then extended superior into the thoracic cavity; from which the thoracic aorta was excised and placed in ice-cold PSS. These tissues were pinned with minimal tension to visualize the vessel segments for dissection. Arterial segments with a length of 0.5 – 2.0 mm were isolated from the mid region of the main uterine artery (diameter 150 – 300 μm) for wire myographic studies and 2–5 mm segments were isolated for pressurized vessel studies. Similarly, 0.5 – 2.0 mm long segments of first order mesenteric artery (diameter 150 – 250 μm) and thoracic aorta (diameter 2 – 3 mm) were isolated for wire myography. A limited analysis of fetal and placental weights were carried out following vascular tissue isolation and those experimental details and results are included in a Supplementary Data section.

2.5 Wire myographic studies

Twenty-four hours post-exposure to AgNP or vehicle, the vasomotor responses to different agonists in segments from the main uterine artery, first order mesenteric artery and thoracic aorta were assessed. The dissected vessel segments were mounted into a DMT 610M multi-channel wire myograph system (Danish Myo Technology, Aarhus N, Denmark), using 40 μm wires or pins. All vessel segments were bathed in 37º C PSS and bubbled with medical grade air throughout the studies. The resting length and diameter of the vessel was measured using a microscope, with a calibrated reticule, and the optimal resting tension for each arterial segment was established at 90% of internal circumference, produced at wall tensions equivalent to 100 mmHg (13.3 kPa). The force responses generated by each vessel segment was recorded using Lab Chart 7 (ADI Instruments, CO, USA) and the force was normalized to the surface area (length x (diameter x 2)) of the vessel to determine the active stress generated in response to different agonists. A depolarization response with K+PSS (109 mM with K+ equal molar substituted for Na+) was used to assess vessel viability and only segments that developed an active stress response of greater than 1 mN/mm2 were considered viable and included for further assessments and data analysis. Following several washouts, the vessel segments were pre-contracted with 1 μM phenylephrine and 3.0 μM acetylcholine was added to assess the endothelial function. An intact endothelium was considered present when the acetylcholine induced relaxation was >70% (>20% for uterine vessels, as all the uterine vessels had a lower endothelial dependent relaxation response) of the phenylephrine induced steady state stress. The vessels were relaxed through a minimum of three 10 minute washouts and then subjected to cumulative concentrations of phenylephrine (0.001 – 30 μM), or endothelin-1 (0.0001 – 1 μM) and followed by relaxation responses to acetylcholine (0.0001 – 30 μM). The uterine and mesenteric arteries responses were also investigated with the agonists angiotensin II (0.0001 – 0.1 μM) and serotonin (0.001 – 1 μM) respectively. These different agonists and their concentrations for each vascular tissue were selected based on the literature reported tissue dependent receptor differences, sensitivity and relevance of agonists in pregnancy related vascular diseases such as preeclampsia (39–42). In each agonist concentration, the contractile response was recorded for a fixed time for each agonist (usually 7 minutes), or until a steady state force (mN) was maintained. The stress generated (force normalized for tissue area, mN/mm2) was calculated in the steady state/plateau at each agonist concentration. The greatest stress generated in the steady state/plateau of a cumulative concentration response, was defined as the “maximum stress generation”.

2.6 Isolated pressurized vessel system

Pressure dependent changes in the uterine vessel diameter were assessed using DMT Pressure Myograph System (Model 110P, Danish Myo Technology, Aarhus N, Denmark), 24 hours post-exposure to AgNP or vehicle. Main uterine artery segments (0.2 – 0.5 mm in length) were immersed in PSS, mounted between 125 μm diameter glass pipettes, cannulated and secured with nylon sutures. The vessel segment was then perfused with 37 ºC PSS, bubbled with medical grade air, pressurized to 50 mmHg and equilibrated for 45 minutes under no-flow conditions with several washouts. The segments that developed constriction response to a potassium depolarization (K+ PSS) were considered viable. Following several washouts with PSS, the vessels segment was pre-constricted with 1 μM phenylephrine followed by 3 μM acetylcholine to assess the viability of the endothelium, by observing the vasodilatory response.

Following several washouts, pressures of both ends were lowered to 20 mmHg and increased by 20 mmHg increments up to 120 mmHg, to assess the myogenic response and reported as changes in internal vessel diameter with changes in pressure under no-flow conditions. MyoView™ edge detection software (Danish Myo Technology, Aarhus N, Denmark) was used to track and quantify the internal and external vessel diameters changes.

2.7 Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 5 and 6 software (San Diego, CA) were utilized for statistical analysis. The data are presented as mean ± SEM (standard error of mean). Initially, repeated measures analysis of variance: ANOVA (43) and Bonferroni post hoc test were used to compare the concentration responses of different agonists. The differences were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05. Each concentration-response curve was further analyzed by comparing across treatment groups using a regression analysis by examining the best-fit values (43). EC50 values (i.e. the concentration at which the 50% of the maximum response in produced) for concentration-responses in wire myographic studies were determined using Hill equation and a two tailed t test was used compare the mean EC50 values. Only the contractile phase was considered for the calculation of EC50 for the agonists with biphasic responses (endothelin 1 and angiotensin II). The initial analysis from studies with naïve pregnant rats revealed that the vascular tissue contractility did not change significantly between these three days of gestation (GD 17–19, data not shown), while the fetal and placental weights appeared to increase(see Supplemental Data). Therefore, the vascular tissue contractility data are reported as a composite group (GD 17–19), while fetal/placental weight data are presented according to gestational day.

3. Results

3.1 Silver nanoparticle characterization

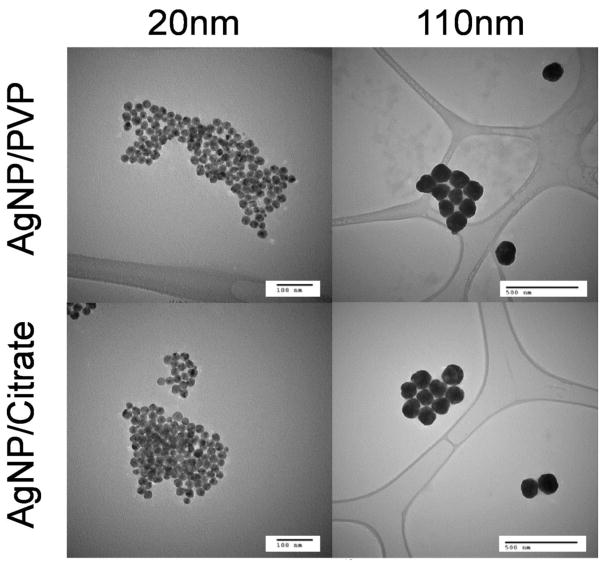

Particle composition, size data, zeta potentials and endotoxin contamination of PVP and citrate stabilized silver nanoparticle suspensions are reported in the Initial Characterization Data for NCNHIR Silver ENMs (36) and are summarized in Table 1. This characterization was done prior to the AgNP distribution to members of the NIEHS (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences) Centers for Nanotechnology Health Implications Research (NCNHIR) Consortium (37). The zeta potentials for all four types of AgNP in suspension were greater than −23 mV, indicating a high suspension stability for these samples. All samples tested negative for bacterial contamination and had minimal endotoxin presence. Representative transmission electron microscopic images of the AgNP are included in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Transmission electron microscopic images of AgNP suspensions used for intravenous exposure.

3.2 Changes in the vascular tissue contractility following AgNP and vehicle exposure

There were significant differences in contractile responses of the vascular tissues from pregnant rats exposed to intravenous AgNP/PVP or AgNP/citrate across the three vascular beds studied. The results outlined below and illustrated in Figures 3 – 7 reflect the cumulative concentration responses of various vascular tissues to different agonists. Data are graphed separately for PVP and citrate stabilized AgNP formulations in comparison to the naïve, for ease of illustrating any size dependent changes in vascular tissue contractility within a formulation. The EC50 values for all vessel segments are reported in Table 2. There were no significant differences between the responses of the vessel segments from the rats exposed to PVP used for stabilization of 110 nm AgNP or 20 nm AgNP (i.e. the two PVP vehicle controls). The use of two different molecular weight PVP polymers allowed for the matching of stabilizing agent with physical sizes of particle in an effort to ensure similar uniform particle coating conditions. Therefore, these data were combined and reported as “PVP” in the graphs and tables. We did not observe any overt response trends within the gestational days range examined (GD 17 – 19) between the naïve and vehicle treated (PVP or Citrate) despite having an unbalanced GD number in/between these groups, thus we choose to report a combined GD response for each group. We do not discount a possibility that GD differences may occur but to tease out such a difference would require a significantly large number of additional control animals.

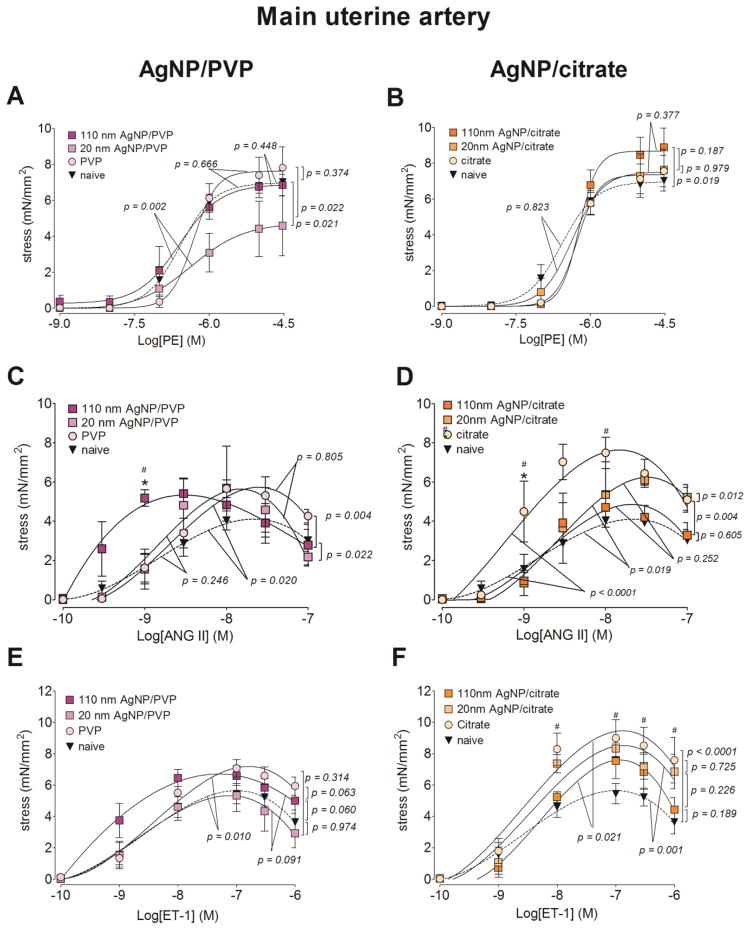

Figure 3. Changes in contractile responses of the main uterine artery following AgNP exposure.

The changes in the contractile responses were assessed by wire myography of the main uterine artery segments from 17 – 19 days pregnant Sprague Dawley rats, 24 hours post-exposure to intravenous (IV) PVP stabilized AgNP (A, C and E) or citrate stabilized AgNP (B, D and E). The stress generation in response to cumulative concentrations of phenylephrine (PE; A and B), angiotensin II (ANG II; C and D) and endothelin 1 (ET-1; E and F) are plotted. * indicates p < 0.05 compared to the stabilization vehicle control (PVP or citrate); # indicates p < 0.05 compared to the naïve and ## indicates p < 0.05 compared between the two sizes of AgNP (20 nm and 110 nm)using repeated measures ANOVA (n = 3 – 8 dams). The p values were derived following the comparison of each concentration response curve across treatment groups using a regression analysis by examining the best-fit values.

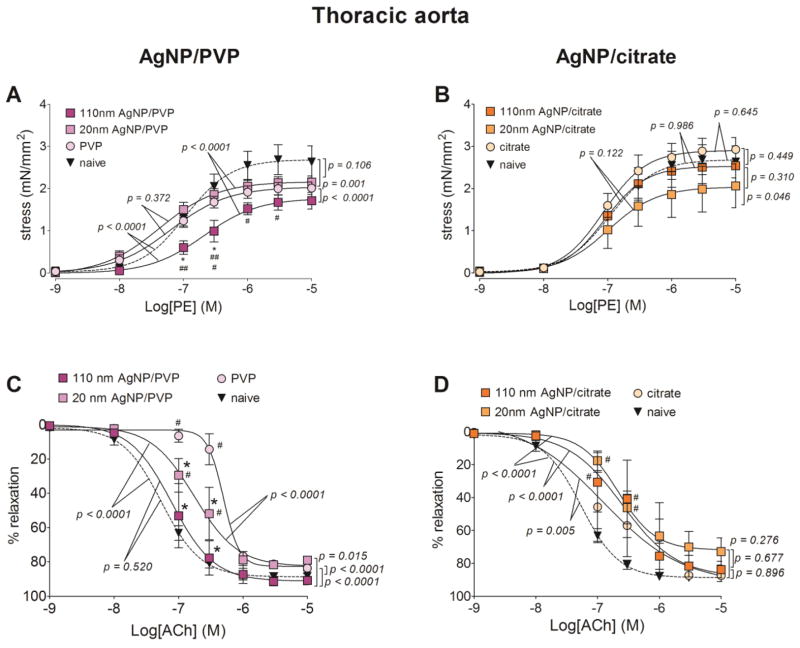

Figure 7. Changes in contractile and relaxation responses of the thoracic aorta following AgNP exposure.

The changes in contractile and relaxation responses were assessed by wire myography in thoracic aortic segments from 17 – 19 days pregnant Sprague Dawley rats, 24 hours post-exposure to intravenous (IV) PVP stabilized AgNP (A and C) or citrate stabilized AgNP (B and D). The stress generation in response to cumulative concentrations of phenylephrine (PE; A and B) and percentage relaxation form a 10 μM phenylephrine pre-stimulation stress level in response to cumulative concentrations of acetylcholine (Ach; C and D) are graphed. * indicates p < 0.05 compared to stabilization vehicle control (PVP or citrate); # indicates p < 0.05 compared to the naïve and ## indicates p < 0.05 compared between the two sizes of AgNP (20 nm and 110 nm)using repeated measures ANOVA (n = 4 – 8 dams). The p values were derived following the comparison of each concentration response curve across treatment groups using a regression analysis by examining the best-fit values.

Table 2.

Calculated EC50 values for the contractile and relaxation response.

| Vessel | Agonist | EC50 (mean ± SEM)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| naïve | PVP | 20 nm AgNP/PVP | 110 nm AgNP/PVP | citrate | 20 nm AgNP/citrate | 110 nm AgNP/citrate | ||

| MUA |

PE (nM) |

269.8 ± 135.0 | 538.1 ± 62.4 | 491.9 ± 115.4 | 362.9 ± 141.4 | 607.1 ± 41.3 | 522.7 ± 69.2 | 604.6 ± 42.5 |

|

ET-1 (nM) |

2.2 ± 0.9 | 4.4 ± 1.5 | 2.8 ± 1.5 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 4.0 ± 1.2 | 5.7 ± 2.1 | |

|

ANGII (nM) |

2.5 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | |

|

Ach (nM) |

211.7 ± 102.1 | 458.1 ± 85.7 | 215.6 ± 130.9 | 196.0 ± 80.5 | 351.4 ± 59.7 | 304.4 ± 38.6 | 333.7 ± 94.9 | |

|

| ||||||||

| MA |

PE (nM) |

1564.0 ± 332.0 | 1511.0 ± 205.5 | 1370.0 ± 705.4 | 694.5 ± 58.5* | 1328.0 ± 728.0 | 788.5 ± 118.5 | 1183.0 ± 269.6 |

|

ET-1 (nM) |

5.3 ± 1.3 | 4.3 ± 2.5 | 4.4 ± 2.1 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 1.4 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | |

|

5HT (μM) |

270.6 ± 79.4 | 291.4 ± 22.7 | 284.8 ± 13.5 | 261.6 ± 24.4 | ND | 443.4 ± 104.9 | 281.5 ± 26.3 | |

|

Ach (μM) |

38.4 ±11.8 | 220.5 ± 14.5# | 59.0 ± 53.1* | 47.9 ± 29.7* | 57.5 ± 18.5 | 120.0 ± 12.2 | 167.5 ± 80.9 | |

|

| ||||||||

| TA |

PE (μM) |

125.1 ± 25.8 | 71.6 ± 12.0 | 54.2 ± 19.1## | 146.1± 31.6* | 104.4 ± 22.4 | 138.4 ± 25.3† | 99.1 ± 11.2 |

|

Ach (nM) |

49.4 ± 11.8 | 3226. 0 ± 522.3# | 972.9 ± 792.4* | 263.4 ± 209.0* | 152.2 ± 71.3 | 560.4 ± 129.3# | 1486.0 ± 1414.0 | |

EC50 values for cumulative concentration responses reported in Figures 2–6 were calculated using the Hill equation. MUA: main uterine artery, MA: mesenteric artery, TA: thoracic aorta, PE: phenylephrine, ET-1: endothelin 1, ANG II: angiotensin II, Ach: acetylcholine and 5HT: serotonin.

indicates p < 0.05 compared to stabilization vehicle (PVP or citrate),

indicates p < 0.05 compared to naïve,

indicates p < 0.05 compared between 20 and 110 AgNP in the same stabilization vehicle and

indicates p < 0.05 compared between PVP and citrate formulations of the same size AgNP, using a two tailed t test (n = 3 – 10).

ND = not determined

3.3 Main uterine artery

With all three agonists (phenylephrine, angiotensin II and endothelin 1), the maximum stress generation was relatively lower with 20 nm AgNP/PVP exposure, when compared to the same formulation of the larger particle size (i.e. 110 nm AgNP/PVP). Twenty-four hours following IV 20 nm AgNP/PVP exposure, the maximum stress generation in the main uterine artery segments in response to phenylephrine was 2.27 mN/mm2 (33%) lower than 110 nm AgNP/PVP exposure and 2.44 mN/mm2 (34%) lower than the naïve (Figure 3.A). The main uterine artery segments exposed to 110 nm AgNP/PVP started contracting at lower concentrations of angiotensin II (Figure 3.C) and endothelin 1 (Figure 3.E) and developed a higher maximum stress generation, when compared to both naïve and 20 nm AgNP/PVP.

The overall stress generation of the main uterine artery segments from citrate and citrate stabilized AgNP exposed rats were higher when compared to the naïve. The maximum stress generation to phenylephrine was increased by 1.88 mN/mm2 (26.8%) in the vessel segments from 110 nm AgNP/citrate exposed rats when compared to the naïve (Figure 3. B). Following cumulative addition of angiotensin II and endothelin 1, the uterine artery segments from citrate exposed rats developed 3.53 mN/mm2 (86.1%) and 3.82 mN/mm2 (67.5%) higher maximum stress, when compared to the naïve. When stimulated with both angiotensin II and endothelin 1, 20 nm AgNP/citrate exposed vessel segments generated 1.4 mN/mm2 (28.8%) and 0.9 mN/mm2 (11.8%) higher maximum stress when compared to the same formulation of the larger AgNP (i.e. 110 nm AgNP/citrate, Figure 3. D and F). The above changes in stress generation in response to the agonists were not accompanied by changes in sensitivity of the uterine artery contractile tissue, as the EC50 values were not different between the treatment groups (Table 2).

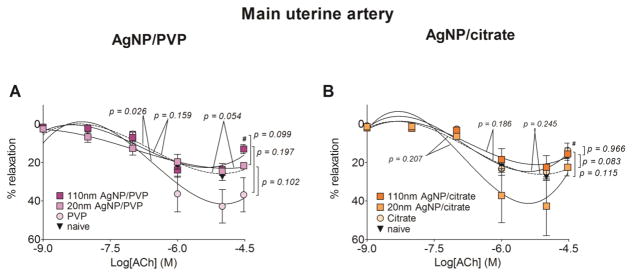

The relaxation response to acetylcholine was relatively unaffected by the exposure to either the PVP or citrate stabilized AgNP (Figure 4.A and B) and the EC50 values were not different between the treatment groups (Table 2). The exception was in the vessel segments from PVP vehicle control exposed rats, which developed 14.2% greater maximum relaxation response from the phenylephrine pre-contraction, when compared to the naïve.

Figure 4. Changes in relaxation responses of the main uterine artery following AgNP exposure.

The changes in the relaxation responses were assessed by wire myography of the main uterine artery segments from 17 – 19 days pregnant Sprague Dawley rats, 24 hours post-exposure to intravenous (IV) PVP stabilized AgNP (A) or citrate stabilized AgNP (B). The percentage relaxation form a 30 μM phenylephrine pre-stimulation stress level, in response to cumulative concentrations of acetylcholine is graphed. # indicates p < 0.05 compared to the naïve using repeated measures ANOVA (n = 3 – 8 dams). The p values were derived following the comparison of each concentration response curve across treatment groups using a regression analysis by examining the best-fit values.

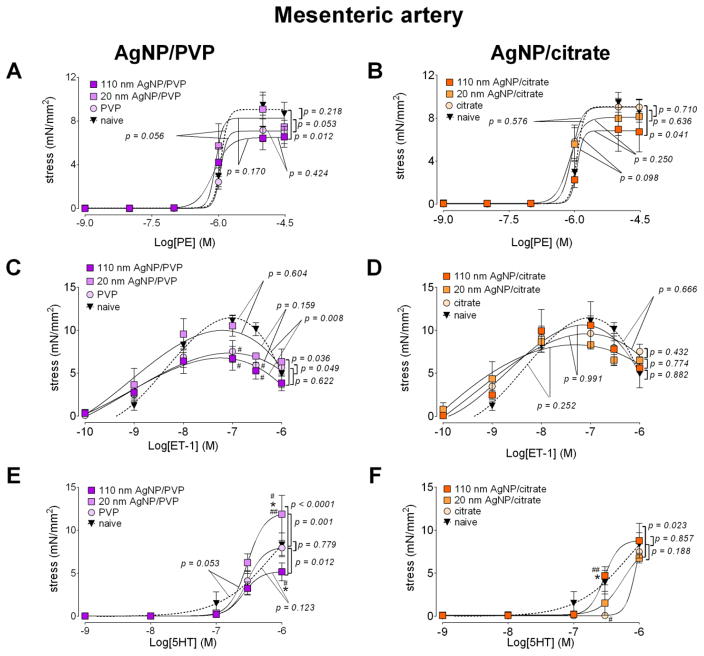

3.4 First order mesenteric artery

With all three agonists (phenylephrine, endothelin 1 and serotonin), the maximum stress generation was relatively lower with 110 nm AgNP/PVP exposure, when compared to the same formulation of the smaller particle size (i.e. 20 nm AgNP/PVP) in the first order mesenteric artery segments (Figure 5A, C and E). The mesenteric artery’s response pattern was in contrast to the uterine artery where the stress generation was lower with 20 nm AgNP/PVP. When compared to the vessels from naïve animals, the maximum stress generation from 110 nm AgNP/PVP exposed rats was lower for phenylephrine (by 2.65 mN/mm2, 28.9%, Figure 5.A), endothelin 1 (by 4.66 mN/mm2, 40.6%, Figure 5.C) and serotonin (by 3.41 mN/mm2, 38.2%, Figure 5.E). The mean EC50 value for phenylephrine contractile response was reduced, indicating an increased sensitivity to the agonist, when compared to the naïve following 110 AgNP/PVP exposure, in addition to the lower stress generation (Table 2).

Figure 5. Changes in contractile responses of the mesenteric artery following AgNP exposure.

The changes in the contractile responses were assessed by wire myography of the first order mesenteric artery segments from 17 – 19 days pregnant Sprague Dawley rats, 24 hours post-exposure to intravenous (IV) PVP stabilized AgNP (A, C and E) or citrate stabilized AgNP (B, D and F). The stress generation in response to cumulative concentrations of phenylephrine (PE; A and B), endothelin 1 (ET-1; C and D) and serotonin (5HT; E and F) are plotted. * indicates p < 0.05 compared to stabilization vehicle control (PVP or citrate); #in dicates p < 0.05 compared to the naïve and ## indicates p < 0.05 compared between the two sizes of AgNP (20 nm and 110 nm)using repeated measures ANOVA (n = 3 – 8 dams). The p values were derived following the comparison of each concentration response curve across treatment groups using a regression analysis by examining the best-fit values.

Minimal differences in response to phenylephrine, endothelin 1 and serotonin were observed following AgNP/citrate exposure, (Figure 5.B D and F), of the first order mesenteric artery segments. The lack of response to these agents was in contrast to the uterine artery responses where the stress generation was significantly increased following citrate and AgNP/citrate exposure. The only notable change was reduction in maximum stress generation occurred in response to phenylephrine stimulation from the 110 nm AgNP/citrate exposure (reduced by 2.25 mN/mm2 or 26.7%, Figure 5.B) compared to the naïve, with no differences between the mean EC50 values (Table 2).

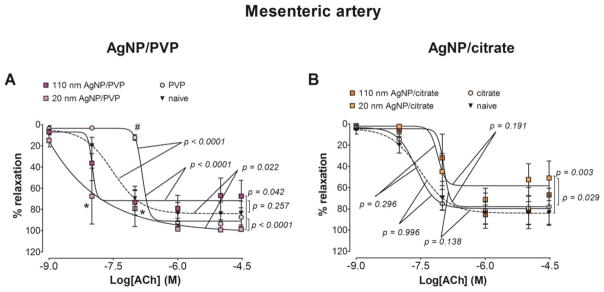

The maximum relaxation from a phenylephrine pre-stimulation stress in response to acetylcholine was unchanged following exposure to PVP or AgNP/PVP. We report a reduced sensitivity to acetylcholine in the mesenteric artery segments from the PVP exposed rats as the mean EC50 value was increased by 5.7 fold compared to naïve, by 3.7 fold compared to 20 nm AgNP/PVP and by 4.6 fold compared to 110 nm AgNP/PVP (Figure 6.A and Table 2). The maximum relaxation was reduced by 25.1% compared to naïve following 20 nm AgNP/citrate exposure (Figure 6.B) without changes in the EC50 values (Table 2).

Figure 6. Changes in relaxation responses of the mesenteric artery following AgNP exposure.

The changes in the relaxation responses were assessed by wire myography of the mesenteric artery segments from 17 – 19 days pregnant Sprague Dawley rats, 24 hours post-exposure to intravenous (IV) PVP stabilized AgNP (A) or citrate stabilized AgNP (B). The percentage relaxation form a 30 μM phenylephrine pre-stimulation stress level in response to cumulative concentrations of acetylcholine is graphed. * indicates p < 0.05 compared to stabilization vehicle control (PVP or citrate) and # indicates p < 0.05 compared to the naïve using repeated measures ANOVA (n = 3 – 8 dams). The p values were derived following the comparison of each concentration response curve across treatment groups using a regression analysis by examining the best-fit values.

3.5 Thoracic aorta

The maximum stress generation of thoracic aortic segments, with cumulative addition of phenylephrine, and following 110 nm AgNP/PVP exposure was 0.41 mN/mm2 (19.1%), lower than 20 nm AgNP/PVP, 0.31 mN/mm2 (15.1%) lower than PVP and 0.98 mN/mm2 (36.0%) lower than the naïve (Figure 7.A). Compared to the naïve, 20 nm AgNP/PVP exposure lowered the maximum stress by 0.57 mN/mm2 (20.9%). The EC50 for phenylephrine contraction was increased following 110 nm AgNP/PVP, indicating a lower sensitivity to phenylephrine. In contrast, 20 nm AgNP/citrate exposure lowered the maximum stress by 0.89 mN/mm2 (30.4%), compared to citrate exposure, while 110 nm AgNP/citrate exposure did not significantly change the maximum stress (Figure 7.B).

The relaxation response to acetylcholine in the thoracic aorta was similar to the mesenteric artery responses as the PVP exposure lead to a diminished relaxation response compared to both naïve and AgNP/PVP (Figure 7.C). We also report a reduced sensitivity to acetylcholine in the thoracic aorta from the PVP exposed rats as the mean EC50 value was increased by 65.3 fold compared to naïve, by 3.3 fold compared to 20 nm AgNP/PVP and by 12.2 fold compared to 110 nm AgNP/PVP (Table 2). When compared to the naïve, the relaxation response was diminished following exposure to citrate, 20 nm AgNP/citrate and 110 nm AgNP/citrate (Figure 7.D).

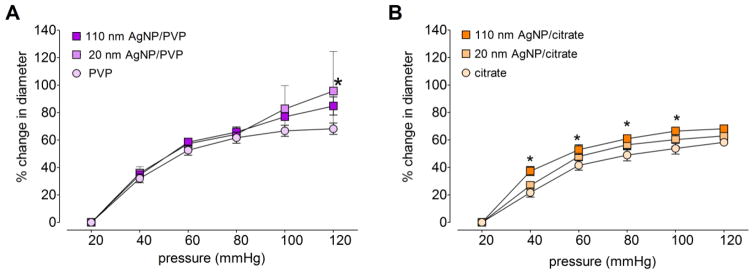

3.6 Pressure related changes in vessel diameter of the main uterine artery

The increase in main uterine artery diameter with 20 mmHg pressure increments are reported as a percentage of the initial internal diameter (i.e. at 20 mmHg) in Figure 8. Overall, the diameter changes were diminished following citrate and AgNP/citrate exposure (Figure 8.B) as compared to responses from PVP and AgNP/PVP exposure (Figure 8.A). In addition, 110 nm AgNP/citrate exposure lead to a 9.8 % greater diameter increase at 120 mmHg, compared to citrate vehicle (Figure 8.B).

Figure 8. Changes in main uterine artery diameter in response to changes in intravascular pressure.

The changes in stable internal diameter (as a percentage of the diameter at 20 mmHg) with 20 mmHg increments of intravascular pressure were assessed using an isolated pressurized vessel system, in the main uterine artery segments from Sprague Dawley rats following intravenous exposure to 20 nm or 110 nm AgNP stabilized in PVP (A) or citrate (B). *indicates p < 0.05 compared to the vehicle controlusing repeated measures ANOVA (n = 2 – 8 dams).

The vascular segment diameter differences at 120 mmHg revealed ~ 10% larger diameter for PVP exposed rats as compared to the diameter from citrate exposed rats. The PVP stabilized AgNP exposure resulted in larger diameter changes when compared to citrate stabilized AgNP exposure. In particular, at 120 mmHg the diameter changes were 32.7% more within 20 nm sized AgNP and 16.6% more within the 110 nm sized AgNP.

4. Discussion

We report moderate changes in blood vessel contractility that differ with the particle size, stabilization-vehicle (PVP or citrate) and vascular bed, following a single acute intravenous exposure to silver nanoparticles during late stages of pregnancy. The main uterine artery segments manifested relatively more robust changes in tissue contractility compared to those from mesenteric artery and thoracic aortic segments following exposure to the nanosilver (AgNP). Despite the complexity of these responses to the four types of AgNP exposure, a pattern could be identified as the mesenteric and aortic vessels responded in a similar manner with attenuated contractile responses, in contrast to the increased contractile responses of the uterine artery with both AgNP/PVP and AgNP/citrate exposure. Our initial hypothesis was supported by the observation of increased contractile responses in the main uterine artery following exposure to citrate stabilized AgNP. Overall, these results demonstrate the vascular response to acute intravenous AgNP exposure appears to be vascular bed dependent.

The administration of silver nanoparticles by an intravenous route facilitates the study of potential cardiovascular impairment as by means of an immediate vascular tissue interaction with AgNP, as might occur in an acute exposure such as in a medical therapeutic agent application (44, 45). Even during an inhalational exposure, nanoparticle translocation to vascular and fetal tissue is postulated as a mechanism of cardiovascular impairment (17), in addition to reported lung inflammation and autonomic nervous system mediated changes in vascular tissue contractility (46). This particle interaction phenomenon also applies to oral exposure of AgNP, in which a significant proportion of silver can be transferred to the blood stream resulting in an end organ accumulation with acute or chronic exposure, particularly in the placenta during pregnancy (21). Within the mass based dose of approximately 701.75 μg/kg of AgNP in the current study, the number of nanoparticles and surface area of contact would vary significantly between different AgNP formulations administered as the size difference between 20 and 110 nm produce significant differences in surface area: mass ratio and the particle number per unit mass. The limitations of this mass based dosimetry need to be considered in interpreting these results (47, 48). Even though, the mass based concentration of silver is similar (i.e. 1.0 – 1.1 mg/g) for both 20 and 110 nm AgNP administrations (Table 1), the smaller sized 20 nm AgNP has more nanoparticles and a ~5X total surface area that can be in contact with the exposed tissue, potentially leading to more interactions for mediating any toxicological effects. The relatively stronger contractile response of the uterine artery segments to endothelin 1 and angiotensin II with 20 nm AgNP/citrate compared to that of the 110 nm AgNP/citrate, may represent the manifestation of greater surface area and particle number in the AgNP size dependent changes in vascular tissue contractility.

Apart from the size hypothesis described above, agglomeration/dissolution, precipitation properties and protein coronas associated with different formulations of AgNP may also be contributing to the variances we observed in responses following in vivo exposure (4–10). The characterization of AgNP used in this study reveals differences in surface charge by zeta potential analysis, which defines the agglomeration properties of the four AgNP suspensions. The AgNP/citrate suspensions have a more negative zeta potential when compared to the AgNP/PVP, suggesting a better dispersion (less agglomeration) of particles that may be contributing to process that result in the more robust responses seen in vascular tissue contractility in the uterine artery with AgNP/citrate exposure. The stabilization mechanism and ionic strength of the medium contribute to these differences in agglomeration kinetics as reported by Badawy et al (49) and Balousha et al (50). A recent in vitro exposure study using AgNP complexed to different serum proteins (human serum albumin, bovine serum albumin and high-density lipoprotein) in rat lug epithelial cells and rat aortic endothelial cells reported protein corona dependent differences in AgNP cellular uptake, receptor mediated cellular activation and cytotoxicity (51). The findings of that study suggest that AgNP association with different serum proteins, purportedly forming different protein coronas, may determine patterns of cellular uptake, and thus bio-distribution, biological activity and toxicity in in vivo applications. Some variability of uptake of AgNP by vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells in can be contributing to differential responses seen with the four types of AgNP exposure in our study. We observe approximately, 6 – 10 nm differences between the core and hydrodynamic diameters of all four types of AgNP suspensions (Table 1), which may represent the presence of a protein corona surrounding nanoparticles in suspension. Recently, Shannahan et al applied a comprehensive proteomics approach to determine the identities and abundance of proteins forming the protein corona on 20 and 110 nm AgNP stabilized with PVP or citrate following incubation in biological media. They reported significant differences in distribution of proteins in both the hard and soft corona that are dependent on the medium, size and coating of AgNP (52). Such differences, further modified by the vascular bed micro-environment, we postulate may be contributing to differences in tissue contractility that we observe in three vascular beds. In addition, known pregnancy related changes in serum protein composition (53), altering viscosity of blood during pregnancy, potentially further influence of protein corona composition and possibly vascular reactivity/sensitivity to the AgNP are elements that have yet to be fully investigated.

We observed differential responses between uterine, mesenteric and aortic vessel segments even with exposure to AgNP with the same size and stabilization-vehicle. The uterine artery segments produced stronger constrictor type responses, generating a higher maximum stress following AgNP exposure, while mesenteric artery and aorta responded with reduced stress generation or relaxation responses. The uterine vasculature manifested more robust changes compared to mesenteric vasculature, which may be related to more dynamic structural and functional changes in uterine vasculature without the same extent of compensatory changes in mesenteric vasculature during gestation (39, 40, 54). Increased contractile responses in the uterine artery in response to both endothelin 1 and angiotensin II is vital as these agonists play a key role in mediating the blood supply to the fetus and their functional derangements are associated with preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction (55, 56). We observed reciprocal responses between uterine artery and aortic/mesenteric artery segments following 110 nm AgNP/PVP exposure, with greater contraction in uterine artery and greater relaxation in aorta/mesenteric artery. With AgNP/citrate exposure, uterine vessels developed greater contractile stress compared to the minimal changes observed in aortic/mesenteric segments. These contrasting responses to the same AgNP formulation and vascular bed dependent variability could be attributed to the hormonal effects, permeability, gestational remodeling, smooth muscle content, sensitivity to agonists and differences in particle distribution, ion dissolution or associated protein corona due to circulatory changes during pregnancy (53, 57, 58).

Pressure related changes in vascular diameter in the main uterine artery were studied using an isolated pressurized vessel system to further assess the changes in myogenic response and vascular resistance that may be contributing to the reduced blood supply to fetuses. Compatible with changes in increased contractile stress generation following citrate and AgNP/citrate exposure observed with wire myographic studies, we observed a significant attenuation in diameter increase in response to incremental perfusion pressure, suggesting an increased resistance to diameter expansion and a higher myogenic response following AgNP/citrate exposure.

We report vascular bed dependent changes in tissue contractility following exposure to both vehicle controls (PVP and citrate) when compared to the naïve, suggesting a significant contribution of the vehicle in AgNP mediated contractile responses. The contractile response was increased and prominent in uterine vessels following exposure to citrate, which produced a higher maximum stress compared to naïve and both 20 nm and 110 nm AgNP/citrate. Such changes were not observed in the mesenteric and aortic vessel segments. Increased stress generation/constriction induced by citrate was reversed to some degree by the exposure to AgNP formulations with citrate in the uterine artery, as assessed by both wire and pressure myographic studies. Reciprocal responses to PVP vehicle control was seen between uterine artery and mesenteric artery/aorta, as PVP generated a greater relaxation response in the uterine artery and a lower relaxation response in the mesenteric artery/aorta when compared to naïve vessels. It is interesting to note that the relaxation responses between the 2 PVP or citrate were profoundly different with PVP being much greater that citrate. The mechanism of these responses are not understood but one could speculate on choice of stabilizing agent for the nanoparticle delivery itself can have an impact on vascular tone blood flow and organ perfusion in situ. However, these vehicle mediated responses did not appear to affect the fetal growth as the fetal weight was not changed by either vehicle exposure.

The findings of our study corroborates the functional implications of previously reported physicochemical properties and distribution kinetics (21, 49, 50, 59, 60) of commonly used AgNP formulations with potential exposure during pregnancy. The underlying mechanisms of toxicity difference may be reflected in prokaryotic cell studies that havereported particle size, surface charge and concentration dependent toxicity of AgNP/PVP and AgNP/citrate (of 11 nm hydrodynamic size), where the toxicity as percent mortality was higher in AgNP/citrate compared to AgNP/PVP (60). Further investigation in aquatic systems suggested a similar toxicity profile and demonstrated greater dissolution (to ionic silver) and increased toxicity with AgNP/citrate compared to AgNP/PVP and suggested that the dissolved silver (Ag+) contributed to the observed toxicity (61), conclusions also suggested by the recent studies of Charehasaz et al (26) or Bergin et al (22). These observations are supportive of an apparent vascular toxicity, reported here in a rodent model as a higher contractile stress generating capacity of AgNP/citrate compared to AgNP/PVP. The contribution of silver ions remains a possible underlying mechanism to the observed altered vascular contractility responses. It has been reported that AgNPs can quickly dissolute in water however, that dissolution is slowed by the presence of proteins( 11, 62). Thus one might predict that some of the AgNP will dissolute and result in of an ionic form of sliver. The recent work of Fennell et alon silverdistribution following i.v. administration suggest that the AgNPare retained in tissues while the Ag ion is more likely eliminated in the feces. Still both formsof silver hadaccumulat edin the placental organ with transfer to the fetus(21). Suchplacental silver accumulation and transfer to the fetus is in congruence withother reports looking at both particulateand ionic formsof silver administration during pregnancy( 26, 63, 64). While the outcomes were slightly different, the conclusions drawn were suggesting unique toxicological mechanisms necessitating separate assessment needs as both nano-sized particles or ionic silver are likely be involved in mediating adverse effects (65).

The post-exposure fetal weight assessments in the current study were limited only to the pregnant dams included in the vascular response studies (minimum of four dams per group with varying days of gestation) and further limited to only three fetuses from the mid-uterine region of each dam as site dependent variations in vascular resistance are present in the uterine artery (41). Therefore, the fetal weight assessments in the current study has limitations from a reproductive toxicology perspective (66), are beyond the scope of the current study focusing mainly on vascular tissue assessments and requires future studies with a larger number of dams and corrections for gestational variables.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings of this study suggest that during late stages of pregnancy citrate stabilized AgNP could be associated with detrimental effects on maternal uterine vascular tissue contractility and possibly impacting fetal weight, when compared to responses following PVP stabilized AgNP exposure. Nevertheless, nanoparticle size dependent differential effects were evident within each formulation of AgNP. Out of the three arterial segments (uterine, mesenteric and aortic) studied, the uterine artery manifest increased contractility in response to endothelin 1 and angiotensin II, particularly following exposure to AgNP/citrate, suggesting a possible susceptibility to fetal growth restriction following an acute intravenous AgNP/citrate exposure during pregnancy. The AgNP size, formulation and life stage dependent vascular bed sensitivity need to be considered in order to identify any potential nanotoxicological and nanomedical endpoints of AgNP based applications or exposure during pregnancy.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Use of Silver nanoparticles (AgNP) raises safety concerns during pregnancy.

Pregnant rats were studied 24 hours post-exposure to acute intravenous AgNP.

Contractility of uterine, mesenteric arteries and thoracic aorta were assessed.

AgNP size, formulation and vascular bed dependent differential responses observed.

Maternal exposure to AgNP/citrate may be associated with changes in fetal growth.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the NIEHS Centers for Nanotechnology Health Implications Research (NCNHIR) Consortium for providing the nanoparticles and the National Characterization Laboratory (NCL) for the initial characterization of AgNP suspensions. We would also like to thank Dr. Erin Mann for the technical support with wire myographic studies. This project was funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences grant U19 ES019525 and an AHA Mid-Atlantic Affiliate pre-doctoral fellowship to AKV.

Abbreviations

- 5HT

serotonin

- Ach

acetylcholine

- AgNP

silver nanoparticles

- AgNP/Citrate

citrate-stabilized nanosilver particle

- AgNP/PVP

polyvinylpyrorrolidone-stabilized nanosilver particle

- ANG II

angiotensin

- II DLS

dynamic light scattering

- ENM

engineered nanomaterials

- ET-1

endothelin 1

- EC50

Effective Concentration for 50 % of effect

- GD

gestational day

- IV

intravenous

- NCNHIR

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Centers for Nanotechnology Health Implications Research

- MA

mesenteric artery

- MUA

main uterine artery

- NP

non-pregnant

- P

pregnant

- PE

phenylephrine

- PSS

physiological saline solution

- PVP

polyvinylpyrorrolidone

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- TA

thoracic aorta

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

We declare that no actual or potential conflicts of interests were involved in the findings reported herein. The authors are responsible for the conclusions described in this article, which may not represent those drawn by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, American Heart Association, The University of Colorado, East Carolina University or RTI International.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Seltenrich N. Nanosilver: weighing the risks and benefits. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121(7):A220–5. doi: 10.1289/ehp.121-a220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schluesener JK, Schluesener HJ. Nanosilver: application and novel aspects of toxicology. Arch Toxicol. 2013;87(4):569–76. doi: 10.1007/s00204-012-1007-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong KKY, Liu X. Silver nanoparticles-the real “silver bullet” in clinical medicine? MedChemComm. 2010;1(2):125–31. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang X, Ji Z, Chang CH, Zhang H, Wang M, Liao YP, et al. Use of coated silver nanoparticles to understand the relationship of particle dissolution and bioavailability to cell and lung toxicological potential. Small. 2014;10(2):385–98. doi: 10.1002/smll.201301597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ault AP, Stark DI, Axson JL, Keeney JN, Maynard AD, Bergin IL, et al. Protein Corona-Induced Modification of Silver Nanoparticle Aggregation in Simulated Gastric Fluid. Environmental science Nano. 2016;3(6):1510–20. doi: 10.1039/C6EN00278A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung KF. Inactivation, Clearance, and Functional Effects of Lung-Instilled Short and Long Silver Nanowires in Rats. 2017;11(3):2652–64. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b07313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mao BH, Tsai JC, Chen CW, Yan SJ, Wang YJ. Mechanisms of silver nanoparticle-induced toxicity and important role of autophagy. Nanotoxicology. 2016;10(8):1021–40. doi: 10.1080/17435390.2016.1189614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Utembe W, Potgieter K, Stefaniak AB, Gulumian M. Dissolution and biodurability: Important parameters needed for risk assessment of nanomaterials. Particle and fibre toxicology. 2015;12:11. doi: 10.1186/s12989-015-0088-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braakhuis HM, Gosens I, Krystek P, Boere JA, Cassee FR, Fokkens PH, et al. Particle size dependent deposition and pulmonary inflammation after short-term inhalation of silver nanoparticles. Particle and fibre toxicology. 2014;11:49. doi: 10.1186/s12989-014-0049-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X, Lenhart JJ, Walker HW. Aggregation kinetics and dissolution of coated silver nanoparticles. Langmuir: the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids. 2012;28(2):1095–104. doi: 10.1021/la202328n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson DS, Patchin ES, Silva RM, Uyeminami DL, Sharmah A, Guo T, et al. Influence of particle size on persistence and clearance of aerosolized silver nanoparticles in the rat lung. Toxicological sciences: an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2015;144(2):366–81. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfv005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patchin ES, Anderson DS, Silva RM, Uyeminami DL, Scott GM, Guo T, et al. Size-Dependent Deposition, Translocation, and Microglial Activation of Inhaled Silver Nanoparticles in the Rodent Nose and Brain. Environmental health perspectives. 2016;124(12):1870–5. doi: 10.1289/EHP234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silva RM, Anderson DS, Peake J, Edwards PC, Patchin ES, Guo T, et al. Aerosolized Silver Nanoparticles in the Rat Lung and Pulmonary Responses over Time. Toxicologic pathology. 2016;44(5):673–86. doi: 10.1177/0192623316629804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stapleton PA, Minarchick VC, Yi J, Engels K, McBride CR, Nurkiewicz TR. Maternal engineered nanomaterial exposure and fetal microvascular function: does the Barker hypothesis apply? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(3):227, e1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nurkiewicz TR, Porter DW, Hubbs AF, Stone S, Chen BT, Frazer DG, et al. Pulmonary nanoparticle exposure disrupts systemic microvascular nitric oxide signaling. Toxicol Sci. 2009;110(1):191–203. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuevas AK, Liberda EN, Gillespie PA, Allina J, Chen LC. Inhaled nickel nanoparticles alter vascular reactivity in C57BL/6 mice. Inhal Toxicol. 2010;22(Suppl 2):100–6. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2010.521206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hathaway QA, Nichols CE, Shepherd DL, Stapleton PA, McLaughlin SL, Stricker JC, et al. Maternal-engineered nanomaterial exposure disrupts progeny cardiac function and bioenergetics. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;312(3):H446–H58. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00634.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nymark P, Catalán J, Suhonen S, Järventaus H, Birkedal R, Clausen PA, et al. Genotoxicity of polyvinylpyrrolidone-coated silver nanoparticles in BEAS 2B cells. Toxicology. 2013;313(1):38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loeschner K, Hadrup N, Qvortrup K, Larsen A, Gao X, Vogel U, et al. Distribution of silver in rats following 28 days of repeated oral exposure to silver nanoparticles or silver acetate. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2011;8:18. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-8-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boudreau MD, Imam MS, Paredes AM, Bryant MS, Cunningham CK, Felton RP, et al. Differential Effects of Silver Nanoparticles and Silver Ions on Tissue Accumulation, Distribution, and Toxicity in the Sprague Dawley Rat Following Daily Oral Gavage Administration for 13 Weeks. Toxicological sciences: an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2016;150(1):131–60. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfv318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fennell TR, Mortensen NP, Black SR, Snyder RW, Levine KE, Poitras E, et al. Disposition of intravenously or orally administered silver nanoparticles in pregnant rats and the effect on the biochemical profile in urine. J Appl Toxicol. 2017;37(5):530–44. doi: 10.1002/jat.3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergin IL, Wilding LA, Morishita M, Walacavage K, Ault AP, Axson JL, et al. Effects of particle size and coating on toxicologic parameters, fecal elimination kinetics and tissue distribution of acutely ingested silver nanoparticles in a mouse model. Nanotoxicology. 2016;10(3):352–60. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2015.1072588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melnik EA, Buzulukov YP, Demin VF, Demin VA, Gmoshinski IV, Tyshko NV, et al. Transfer of Silver Nanoparticles through the Placenta and Breast Milk during in vivo Experiments on Rats. Acta Naturae. 2013;5(3):107–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu WJ, Son JM, Lee J, Kim SH, Lee IC, Baek HS, et al. Effects of silver nanoparticles on pregnant dams and embryo-fetal development in rats. Nanotoxicology. 2014;8(Suppl 1):85–91. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2013.857734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hadrup N, Loeschner K, Bergstrom A, Wilcks A, Gao X, Vogel U, et al. Subacute oral toxicity investigation of nanoparticulate and ionic silver in rats. Archives of toxicology. 2012;86(4):543–51. doi: 10.1007/s00204-011-0759-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charehsaz M, Hougaard KS, Sipahi H, Ekici AI, Kaspar C, Culha M, et al. Effects of developmental exposure to silver in ionic and nanoparticle form: A study in rats. Daru: journal of Faculty of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences. 2016;24(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s40199-016-0162-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xue Y, Zhang S, Huang Y, Zhang T, Liu X, Hu Y, et al. Acute toxic effects and gender-related biokinetics of silver nanoparticles following an intravenous injection in mice. J Appl Toxicol. 2012;32(11):890–9. doi: 10.1002/jat.2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y, Bhalli JA, Ding W, Yan J, Pearce MG, Sadiq R, et al. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity assessment of silver nanoparticles in mouse. Nanotoxicology. 2013 doi: 10.3109/17435390.2013.855827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Austin CA, Umbreit TH, Brown KM, Barber DS, Dair BJ, Francke-Carroll S, et al. Distribution of silver nanoparticles in pregnant mice and developing embryos. Nanotoxicology. 2012;6:912–22. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2011.626539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamashita K, Yoshioka Y, Higashisaka K, Mimura K, Morishita Y, Nozaki M, et al. Silica and titanium dioxide nanoparticles cause pregnancy complications in mice. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6(5):321–8. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ema M, Okuda H, Gamo M, Honda K. A review of reproductive and developmental toxicity of silver nanoparticles in laboratory animals. Reprod Toxicol. 2017;67:149–64. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosas-Hernandez H, Jimenez-Badillo S, Martinez-Cuevas PP, Gracia-Espino E, Terrones H, Terrones M, et al. Effects of 45-nm silver nanoparticles on coronary endothelial cells and isolated rat aortic rings. Toxicol Lett. 2009;191(2–3):305–13. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vidanapathirana AK, Thompson LC, Odom J, Holland NA, Sumner SJ, Fennell TR, et al. Vascular Tissue Contractility Changes Following Late Gestational Exposure to Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes or their Dispersing Vehicle in Sprague Dawley Rats. J Nanomed Nanotechnol. 2014;5(3) doi: 10.4172/2157-7439.1000201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vidanapathirana AK, Thompson LC, Mann EE, Odom JT, Holland NA, Sumner SJ, et al. PVP formulated fullerene (C60) increases Rho-kinase dependent vascular tissue contractility in pregnant Sprague Dawley rats. Reprod Toxicol. 2014;49:86–100. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2014.07.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holland NA, Thompson LC, Vidanapathirana AK, Urankar RN, Lust RM, Fennell TR, et al. Impact of pulmonary exposure to gold core silver nanoparticles of different size and capping agents on cardiovascular injury. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2016;13(1):48. doi: 10.1186/s12989-016-0159-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laboratory NC. Initial Characterization Data for NCNHIR Silver ENMs. Vol. 2011. National Cancer Institute at Frederick SAIC-Frederick, Inc; Frederick, MD 21702: Nanotechnology Characterization Laboratory; Nov 28, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schug TT, Johnson AF, Balshaw DM, Garantziotis S, Walker NJ, Weis C, et al. ONE Nano: NIEHS’s strategic initiative on the health and safety effects of engineered nanomaterials. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121(4):410–4. 4e1–5. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1206091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aldossari AA, Shannahan JH, Podila R, Brown JM. Influence of physicochemical properties of silver nanoparticles on mast cell activation and degranulation. Toxicol In Vitro. 2015;29(1):195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dalle Lucca JJ, Adeagbo AS, Alsip NL. Oestrous cycle and pregnancy alter the reactivity of the rat uterine vasculature. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(12):2496–503. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.12.2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dalle Lucca JJ, Adeagbo AS, Alsip NL. Influence of oestrous cycle and pregnancy on the reactivity of the rat mesenteric vascular bed. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(4):961–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.4.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osol G, Mandala M. Maternal uterine vascular remodeling during pregnancy. Physiology (Bethesda) 2009;24:58–71. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00033.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mandala M, Osol G. Physiological remodelling of the maternal uterine circulation during pregnancy. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;110(1):12–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2011.00793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ludbrook J. Repeated measurements and multiple comparisons in cardiovascular research. Cardiovascular research. 1994;28(3):303–11. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei L, Lu J, Xu H, Patel A, Chen ZS, Chen G. Silver nanoparticles: synthesis, properties, and therapeutic applications. Drug discovery today. 2015;20(5):595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang XF, Liu ZG, Shen W, Gurunathan S. Silver Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, Properties, Applications, and Therapeutic Approaches. International journal of molecular sciences. 2016;17(9) doi: 10.3390/ijms17091534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Donaldson K, Duffin R, Langrish JP, Miller MR, Mills NL, Poland CA, et al. Nanoparticles and the cardiovascular system: a critical review. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2013;8(3):403–23. doi: 10.2217/nnm.13.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oberdorster G. Safety assessment for nanotechnology and nanomedicine: concepts of nanotoxicology. J Intern Med. 2010;267(1):89–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hubbs AF, Mercer RR, Benkovic SA, Harkema J, Sriram K, Schwegler-Berry D, et al. Nanotoxicology--a pathologist’s perspective. Toxicol Pathol. 2011;39(2):301–24. doi: 10.1177/0192623310390705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.El Badawy AM, Scheckel KG, Suidan M, Tolaymat T. The impact of stabilization mechanism on the aggregation kinetics of silver nanoparticles. Sci Total Environ. 2012;429:325–31. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baalousha M, Nur Y, Romer I, Tejamaya M, Lead JR. Effect of monovalent and divalent cations, anions and fulvic acid on aggregation of citrate-coated silver nanoparticles. Sci Total Environ. 2013;454–455:119–31. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.02.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shannahan JH, Podila R, Aldossari AA, Emerson H, Powell BA, Ke PC, et al. Formation of a protein corona on silver nanoparticles mediates cellular toxicity via scavenger receptors. Toxicol Sci. 2015;143(1):136–46. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shannahan JH, Lai X, Ke PC, Podila R, Brown JM, Witzmann FA. Silver nanoparticle protein corona composition in cell culture media. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Romero R, Erez O, Maymon E, Chaemsaithong P, Xu Z, Pacora P, et al. The maternal plasma proteome changes as a function of gestational age in normal pregnancy: a longitudinal study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cooke CL, Davidge ST. Pregnancy-induced alterations of vascular function in mouse mesenteric and uterine arteries. Biol Reprod. 2003;68(3):1072–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.009886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dechanet C, Fort A, Barbero-Camps E, Dechaud H, Richard S, Virsolvy A. Endothelin-dependent vasoconstriction in human uterine artery: application to preeclampsia. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e16540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pulgar VM, Yamashiro H, Rose JC, Moore LG. Role of the AT2 receptor in modulating the angiotensin II contractile response of the uterine artery at mid-gestation. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2011;12(3):176–83. doi: 10.1177/1470320310397406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dieye AM, Van Overloop B, Gairard A. Endothelin-1 and relaxation of the rat aorta during pregnancy in nitroarginine-induced hypertension. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1999;13(2):204–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1999.tb00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goulopoulou S, Hannan JL, Matsumoto T, Webb RC. Pregnancy reduces RhoA/Rho kinase and protein kinase C signaling pathways downstream of thromboxane receptor activation in the rat uterine artery. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302(12):H2477–88. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00900.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Monteiro-Riviere NA, Samberg ME, Oldenburg SJ, Riviere JE. Protein binding modulates the cellular uptake of silver nanoparticles into human cells: implications for in vitro to in vivo extrapolations? Toxicol Lett. 2013;220(3):286–93. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Silva T, Pokhrel LR, Dubey B, Tolaymat TM, Maier KJ, Liu X. Particle size, surface charge and concentration dependent ecotoxicity of three organo-coated silver nanoparticles: Comparison between general linear model-predicted and observed toxicity. Sci Total Environ. 2014;468–469:968–76. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Angel BM, Batley GE, Jarolimek CV, Rogers NJ. The impact of size on the fate and toxicity of nanoparticulate silver in aquatic systems. Chemosphere. 2013;93(2):359–65. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.04.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seiffert J, Hussain F, Wiegman C, Li F, Bey L, Baker W, et al. Pulmonary toxicity of instilled silver nanoparticles: influence of size, coating and rat strain. PloS one. 2015;10(3):e0119726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Campagnolo L, Massimiani M, Vecchione L. Silver nanoparticles inhaled during pregnancy reach and affect the placenta and the foetus. 2017:1–12. doi: 10.1080/17435390.2017.1343875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Austin CA, Hinkley GK, Mishra AR, Zhang Q, Umbreit TH, Betz MW, et al. Distribution and accumulation of 10 nm silver nanoparticles in maternal tissues and visceral yolk sac of pregnant mice, and a potential effect on embryo growth. Nanotoxicology. 2016;10(6):654–61. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2015.1107143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Z, Qu G, Su L, Wang L, Yang Z, Jiang J, et al. Evaluation of the biological fate and the transport through biological barriers of nanosilver in mice. Current pharmaceutical design. 2013;19(37):6691–7. doi: 10.2174/1381612811319370012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nemec MD, Kaufman LE, Stump DG, Lindström P, Varsho BJ, Holson JF. Developmental and Reproductive Toxicology: A Practical Approach. 2. Informa Healthcare; 2005. Significance, reliability, and interpretation of developmental and reproductive toxicity study findings; pp. 329–424. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.