Abstract

Despite substantial public, political, and scholarly attention to the issue of immigration and crime, we know little about the criminological consequences of undocumented immigration. As a result, fundamental questions about whether undocumented immigration increases violent crime remain unanswered. In an attempt to address this gap, we combine newly developed estimates of the unauthorized population with multiple data sources to capture the criminal, socioeconomic, and demographic context of all 50 states and Washington, DC, from 1990 to 2014 to provide the first longitudinal analysis of the macro-level relationship between undocumented immigration and violence. The results from fixed-effects regression models reveal that undocumented immigration does not increase violence. Rather, the relationship between undocumented immigration and violent crime is generally negative, although not significant in all specifications. Using supplemental models of victimization data and instrumental variable methods, we find little evidence that these results are due to decreased reporting or selective migration to avoid crime. We consider the theoretical and policy implications of these findings against the backdrop of the dramatic increase in immigration enforcement in recent decades.

Keywords: undocumented immigration, violent crime, immigration enforcement

Few topics have more criminological significance and public policy salience than understanding the impact of undocumented immigration on violent crime. Although the immigration–crime nexus has been at the fore of criminological inquiry since the Chicago School of the early 20th century (Shaw and McKay, 1942), this issue has taken on added importance over the past two decades as the United States has experienced the largest wave of immigration—in both absolute and relative terms—in its history. Nevertheless, despite substantial research attention to the association between immigration and crime (Martinez and Valenzuela, 2006), significant gaps remain in the literature. Most notably, this body of work has mainly been confined to assessments of the overall or Latino foreign-born populations (Feldmeyer, 2009; Martinez, Stowell, and Lee, 2010; Ousey and Kubrin, 2009; Wadsworth, 2010) because of the paucity of data accounting for unauthorized immigrants separately.1 As Ousey and Kubrin (2017: 1.9) highlighted, “the problem with these approaches is that they treat immigrants as a homogenous population and fail to account for significant variation across types of immigrants.” As a result, research on undocumented immigration remains a substantial lacuna in immigration–crime research.

Indeed, in a recent meta-analysis of the 51 macro-level immigration–crime studies conducted between 1994 and 2014, not one was aimed at explicitly examining unauthorized immigration flows (Ousey and Kubrin, 2017). Since that time, we are aware of only one study in which the association between unauthorized immigration and violence was investigated. In that study, Green (2016) found that undocumented immigration is generally not associated with violent crime, though unauthorized immigration from Mexico may be associated with higher rates of violence. Although informative, several limitations of this study warrant further inquiry. Most notably, the analysis is cross-sectional, thus, limiting both the substantive questions under consideration and the analytical leverage to answer them. Substantively, cross-sectional analysis cannot answer the focal question motivating criminological debates on unauthorized immigration: Has the increase in undocumented immigration increased violent crime? Because unauthorized immigration is necessarily a process that unfolds over time, cross-sectional analyses are ill-suited for use in answering this question. Moreover, the methodological distinction between cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis in immigration–crime research is a salient one. As Ousey and Kubrin (2017: 1.13) noted in their meta-analysis, “our findings underscore the fact that the choice between cross-sectional and longitudinal data and analysis procedures is a critical one that likely impacts findings and conclusions in this area.” They concluded that because longitudinal research provides greater analytical rigor, such as superior ability to control for confounding influences, more weight should be given to the findings from longitudinal studies. To date, however, the literature currently lacks a longitudinal assessment of the consequences of undocumented immigration for violent crime (but see Light, Miller, and Kelly, 2017, for an examination of drug and alcohol crimes).

We seek to fill this gap by providing the first longitudinal empirical analysis of the macro-level relationship between undocumented immigration and violent crime. In combining newly developed estimates of the unauthorized population with multiple data sources to capture the criminal, socioeconomic, and demographic context of all 50 states and Washington, DC, from 1990 to 2014, we use fixed-effects regression models to examine the effect of increased unauthorized immigration on violent crime rates.

This analysis is timely given the growth of the undocumented population in recent decades. Between 1990 and 2014, the number of undocumented immigrants more than tripled, from 3.5 million to 11.3 million (Krogstad, Passel, and Cohn, 2016), accounting for more than a third of the increase in the total foreign-born population over this period. This wave of immigration generated substantial public angst regarding the criminality of unauthorized immigrants, leading to immigration reforms and public policies intended to reduce the purported crimes associated with undocumented immigration (Bohn, Lofstrom, and Raphael, 2014). Indeed, the presumptive link between unauthorized immigration and violent crime has become a core assertion in the anti-immigration narrative in public, political, and media discourse (Chavez, 2008) and has been at the center of some of the most contentious immigration-reform policies in recent years (e.g., Arizona SB 1070, 2010).

Moreover, concerns over illegal immigration have arguably been the federal government’s highest criminal law enforcement priority in recent decades. Between 1986 and 2008, the number of U.S. Border Patrol officers increased 5-fold while the budget for border enforcement increased 20-fold (Massey, Pren, and Durand, 2016). As a result, today the U.S. government spends more on immigration enforcement agencies (U.S. Customs and Border Protection and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement) than it does on all other principal criminal law enforcement agencies combined, including the FBI, DEA, Secret Service, Marshal’s Service, and ATF (Meissner et al., 2013). Reductions in crime and violence have been primary justifications for this dramatic development (Department of Homeland Security Immigration and Customs Enforcement [DHS ICE], 2009). Yet, this vast apparatus of criminal justice machinery has been built up to increase public safety with scant empirical evidence that undocumented immigration and violence are linked (positively or negatively).

The results of our analysis not only inform this contentious policy debate, but they also provide us with an opportunity to adjudicate competing theoretical perspectives on the immigration–crime link. Although the weight of the evidence supports the immigrant revitalization perspective, whereby immigration is said to reduce crime and violence by attracting immigrants with low criminal propsensities, strengthening local economies, and bolstering processes of informal social control2 (Lyons, Vélez, and Santoro, 2013), others argue that social disorganization better captures the contemporary immigration–crime relationship (Shihadeh and Barranco, 2013). This perspective may be especially relevant for the unauthorized population who, unlike their documented counterparts, are hindered from effectively forming economic and social ties as a result of their lack of legal standing in the community. It is important to note, however, that almost none (save Green, 2016) of the immigration–violence research to date has systematically examined the undocumented immigrant population, despite the fact that the patterns of authorized and unauthorized immigration in recent decades have not been uniform. For example, of the 10 states that experienced the largest percent increase in undocumented immigrants between 1990 and 2000, only two of them were also in the top 10 for relative increases in lawful immigrants.3

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. The following sections briefly explicate the contrasting theoretical perspectives linking immigration and violence. Given that these perspectives have been given ample treatment elsewhere (Ousey and Kubrin, 2009, 2017), we focus our discussion on the applications of theory to unauthorized immigration specifically. We then turn to the data, research design, and results. Last, we discuss the implications of the findings in the context of contemporary debates on the criminogenic consequences of unauthorized immigration.

MARGINALIZATION, DISORGANIZATION, AND VIOLENCE

Between 2005 and 2010, state legislatures enacted more than 300 anti-immigration laws (Gulasekaram and Ramakrishnan, 2012), including regulations that deny public benefits, services, and health care to unauthorized immigrants, as well as laws that punish employers who hire undocumented workers and landlords who rent to unauthorized immigrants (Varsanyi, 2010). For undocumented immigrants, these laws compound the fact that they are denied almost all forms of federal assistance and, by definition, have no political representation. According to Menjívar and Abrego (2012), the cumulatively injurious effects of immigration laws on the daily lives of unauthorized immigrants represent a form of “legal violence” or what Kubrin, Zatz, and Ramirez (2012) called “state-created vulnerabilities.” Regardless of the term, the lack of legal standing may have several important implications for criminal behavior.

First, as a result of their formal exclusion from the labor market, undocumented immigrants may experience intense economic deprivation (Hall, Greenman, and Farkas, 2010; Massey, 2007). In 2007, the poverty rate among unauthorized adults was double that of U.S.-born adults (Passel and Cohn, 2009) and recent research findings show that undocumented immigrants face a “double disadvantage” in the U.S. labor force: first by being disproportionately driven into the secondary labor market and second by paying a wage penalty within these occupations (Durand, Massey, and Pren, 2016). Moreover, because of their marginal labor market skills and lack of economic assets upon arrival (Jargowsky, 2009), many undocumented immigrants may be channeled into structurally disadvantaged areas (Hagan and Palloni, 1999) and, therefore, differentially exposed to criminogenic conditions such as entrenched poverty. As a result, undocumented immigrants may have limited legitimate opportunities for upward mobility and thus may turn to illegitimate economic pursuits, such as robbery (Baker, 2015; Ousey and Kubrin, 2009). In this vein, illicit drug markets are of particular concern when considering the criminogenic consequences of undocumented immigration. Although recent empirical evidence suggests that trends in undocumented immigration are not associated with increased drug crime (Light, Miller, and Kelly, 2017), undocumented immigrants are commonly perceived to be participants in illegal drug markets. Furthermore, trends in illegal drug activity are associated with changes in crime rates (Baumer et al., 1998; Ousey and Lee, 2002). To the extent that drugs offer opportunities denied in the legitimate labor market, undocumented immigrants may be more heavily involved in illicit drug markets, which in turn increases crimes like robbery, murder, and overall violence.

Because unauthorized immigrants face exclusionary governmental policies, a second factor potentially contributing to increased crime concerns the inability of undocumented immigrants to form effective ties with government officials. That is, because undocumented immigrants are forced to live “shadowed lives” (Chavez, 2013) for fear of detection, unauthorized communities may feel socially isolated and cynical of the legal and political system (Kirk et al., 2012). As a result, rather than involving government authorities, undocumented immigrants may turn to violence as a form of dispute resolution (Black, 1983), though this may not be reflected in official crime statistics due to underreporting within undocumented communities, a point to which we return in the analysis. In addition, the inability to engage fully in civic and political life may undermine undocumented immigrants’ ability to organize collectively around common goals, such as crime reduction (Lyons, Vélez, and Santoro, 2013). In this regard, this perspective adjoins classic arguments on the social disorganizing effects of rapid immigration (Shaw and McKay, 1942), by which immigration was thought to increase crime by undermining social networks and institutions necessary for regulating behavior. Although contemporary researchers question this thesis for immigrants generally (Lee and Martinez, 2009), social disorganization theory may be more applicable for undocumented immigrants given their constant status as “internal exiles” (Simon, 2007) with limited access to mainstream political and economic institutions.

The discussion on unauthorized immigration and crime tends to focus on the behavior of the undocumented, however, another important consideration is the effect of immigration on U.S. workers. Much of the controversy surrounding undocumented immigration concerns economic threats to the U.S. labor force (Chavez, 2008), and the results of recent research explicitly link contemporary immigration to increased violence due to competition for low-skilled jobs (Shihadeh and Barranco, 2010). These effects may be even more pronounced for unauthorized immigration (compared with overall immigration), given that the undocumented are almost entirely relegated to the low-skilled labor market (Passel and Cohn, 2009). Hence, even if undocumented immigrants are not more crime prone, unauthorized immigration may increase violence by economically disadvantaging low-skilled U.S. workers.

Lastly, population age structure may connect undocumented immigration and violence. The age distribution of the unauthorized immigrant population is remarkably different from that of the U.S.-born and lawful immigrant population, with unauthorized immigrants far more likely to be young adults (18–24 years of age; Passel and Cohn, 2009)—a life-course period in which violence peaks. Consequently, unauthorized immigrants may increase crime rates by shifting the age composition toward a more “violence-prone” age profile.

Taken together, there are multiple theoretical reasons to expect undocumented immigration to increase violent crime. Skeptics, however, often point out that during the same period the United States experienced substantial growth in the unauthorized population, it simultaneously witnessed the most dramatic reductions in criminal violence in half a century (Sampson, 2008). Thus, rather than viewing immigration (both documented and undocumented) as criminogenic, these contrasting trends have motivated a competing body of research on the potential benefits of immigration.

SELECTION, NETWORKS, AND IMMIGRANT REVITALIZATION

In direct contrast to the marginalization and disorganization perspectives, researchers have recently provided considerable theoretical reasoning to anticipate that undocumented immigration would decrease crime. The first concerns the selective nature of immigration. Many immigrants are driven by the pursuit of economic and educational opportunities for themselves and their families (Chavez, 2013), and clandestine migration requires a substantial amount of motivation and planning. As such, undocumented immigrants may be selected on attributes that predispose them to low criminal propensity, such as high motivation to work and ambition to achieve (Butcher and Piehl, 2007; Stowell et al., 2009). Related to this point, unauthorized immigrants, much more so than lawful immigrants, have strong incentives to avoid criminal involvement for fear of detection and deportation. In both scenarios, increases in undocumented immigration should decrease violent crime over time.

The economic benefits associated with undocumented immigration are other factors possibly linking the unauthorized population to lower violence. Despite the oft-repeated claims that immigration harms the U.S. economy, researchers have suggested that immigration (including undocumented immigration) is a net economic positive by increasing tax revenue (Gardner, Johnson, and Wiehe, 2015), infusing new business and social capital (Light and Gold, 2000), and filling employment niches that complement native-born labor sectors (Hinojosa-Ojeda, 2010). Indeed, despite their legal exclusion from the labor market, a full 93 percent of working-age unauthorized immigrant men were in the labor force in 2009 (Donato and Armenta, 2011).

In addition, existing ethnic enclaves can provide important economic resources to aid the integration of the undocumented (Portes and Jensen, 1992) as well as social networks capable of bolstering processes of informal social control (Feldmeyer, 2009). This process is often referred to as the immigrant revitalization thesis (Lee and Martinez, 2002), whereby the influx of immigrants is said to strengthen organizations and institutions (e.g., schools, churches, and social clubs). These organizations, in turn, help shelter immigrants from economic deprivation and other social problems by reinforcing social cohesion and bonding children to mainstream institutions (Ley, 2008; Theodore and Martin, 2007).

Moreover, the common practice of “chain migration” characteristic of undocumented immigration (Massey, 1990) further buttresses immigrant social capital networks that provide key resources and social support systems for unauthorized newcomers, such as transportation assistance, childcare, and housing (Portes and Rumbaut, 2006). In short, the immigrant networks that sustain the unauthorized migration process also help facilitate the economic and social integration of undocumented immigrants, thus, minimizing the effects of economic disadvantage, providing an umbrella of social control, and potentially reducing the frequency of violence.

Undocumented immigration may also help decrease criminal violence through a process of cultural diffusion. Cultural adaptations to concentrated disadvantage—such as Anderson’s (1999) Code of the Streets—have been identified as major contributing factors to higher rates of violent crime (Sampson and Wilson, 1995). According to Sampson (2012), introducing outsiders who do not share the cultural expectations or social meaning of the “code of the street” can have a suppressing effect on violence. Thus, to the extent that immigrant cultures are less encouraging of violence, both lawful and undocumented immigration may contribute to lower rates of violent crime by leading to “greater visibility of competing nonviolent mores” that affect not just immigrants “but diffuse through social interactions to depress violent conflict in general” (Sampson, 2012: 257–8).

Finally, the number of police officers may play a role in the relationship between crime and undocumented immigration. As indicated, increases in undocumented immigration are associated, at least in part, with public fear of criminal behavior. States may react to these fears by hiring more police officers in an effort to assuage concerns and deter criminal behavior. By increasing formal social control, larger police force sizes have been shown to decrease crime (Levitt, 2004). Thus, undocumented immigration may be correlated with decreases in crime through increased formal social control (e.g., police force size).

DATA, METHOD, AND LOGIC OF ANALYSIS

We examine the competing theoretical perspectives outlined earlier by using multiple data sources collected annually at the state level (including Washington, DC) between 1990 and 2014. Our crime measures come from the FBI Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) program, which counts all serious offenses reported to the police. Our measures of the undocumented population come from two different sources: The Center for Migration Studies and the Pew Research Center (described in detail later). In addition, data on an array of socioeconomic, demographic, and criminogenic characteristics were collectively derived from the U.S. Census, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the National Prisoner Statistics, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). These interrelated sources of data provide a comprehensive longitudinal resource for examining the undocumented immigration–violence relationship. Sources, measurement properties, and descriptive statistics for all variables used in the analysis are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Dependent and Explanatory Variables, 1990–2014

| Measures | Coding and Description | Between States Mean | Within States Mean | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | ||||

| (In) Violent Crime Index | Violent crimes known to the police (per 100,000)—logged | 5.97 (.52) |

.00 (.21) |

FBI Uniform Crime Reports |

| (In) Homicide rate | Homicides (per 100,000 in the population)—logged | 1.51 (.61) |

.00 (.28) |

FBI Uniform Crime Reports |

| (In) Robbery rate | Robberies (per 100,000 in the population)—logged | 4.51 (.85) |

.00 (.24) |

FBI Uniform Crime Reports |

| (In) Aggravated assault rate | Aggravated Assaults (per 100,000 in the population)—logged | 5.51 (.55) |

.00 (.24) |

FBI Uniform Crime Reports |

| (In) Rape rate | Rapes (per 100,000 in the population)—logged | 3.50 (.29) |

.00 (.18) |

FBI Uniform Crime Reports |

| Focal Measures | ||||

| Undocumented immigrants—CMS | Estimated proportion of population that is undocumented | 1.93 (1.57) |

.00 (.76) |

Center for Migration Studies |

| Undocumented immigrants—Pew | Estimated proportion of population that is undocumented | 2.13 (1.52) |

.00 (.87) |

Pew Hispanic Center |

| Covariates | ||||

| Lawful immigrants | Proportion of population that are lawful foreign-born residents | 6.45 (4.73) |

.00 (.92) |

IPUMS |

| Povertya | Proportion of population that is in poverty | 13.19 (3.21) |

.00 (1.87) |

U.S. Census Bureau/American Community Survey |

| Low educational attainmenta | Proportion of the population over 25 without a high school degree | 15.35 (3.91) |

.00 (3.39) |

U.S. Census Bureau/American Community Survey |

| Single parent childrena | Percent of children born to single mothers | 34.54 (6.43) |

.00 (4.57) |

U.S. Census Bureau/American Community Survey |

| Racial compositiona | Proportion of the population that is non-Hispanic black | 10.65 (10.58) |

.00 (.65) |

U.S. Census Bureau/American Community Survey |

| Unemployment | Proportion of civilian population over 16 that is unemployed | 5.74 (.94) |

.00 (1.62) |

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics |

| Manufacturing | Percent employed in the manufacturing industry | 12.57 (4.67) |

.00 (2.60) |

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics |

| Managerial / professional | Percent employed in professional or managerial occupations | 31.89 (3.38) |

.00 (4.55) |

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics |

| Crime prone ages (18-24) | Percent of population age 18-24 | 9.93 (.67) |

.00 (.56) |

U.S. Census Bureau/American Community Survey |

| Urban population | Percent of the population living in urban areas | 71.97 (14.63) |

.00 (2.30) |

U.S. Census Bureau |

| Incarceration rate | Number of people incarcerated (per 100,000 in the population) | 385.69 (166.49) |

.00 (90.15) |

BJS National Prisoner Statistics |

| Police per capita | Number of police officers (per 100,000 in the population) | 215.63 (63.41) |

.00 (19.20) |

UCR Police Employee Data |

| Gun availability | Proportion of suicides perpetrated with a gun | 55.48 (12.16) |

.00 (5.01) |

CDC WONDER Underlying Cause-of-Death Mortality Files |

| Drug activity | Drug overdose mortality rate (per 100,000) | 9.07 (2.67) |

.00 (4.91) |

CDC WONDER Underlying Cause-of-Death Mortality Files |

NOTE: Number of observations = 1259. Std. deviations reported in parentheses.

Combined using principal component analysis to create index of Structural Disadvantage.

After accounting for missing data, the final sample consists of 1,209 state-years (50 states plus Washington, DC, over 24 years of data).4 This collection of data offers several advantages for this study. First, UCR data are the most commonly used criminal justice statistics (Mosher, Miethe, and Phillips, 2002) with evidence of reliable reporting of serious felonies over time that accurately track victimization trends (Blumstein, Cohen, and Rosenfeld, 1991; Lauritsen, Rezey, and Heimer, 2016). Second, the data coverage is available for the full study period (1990–2014), providing an opportunity to examine the longitudinal criminological consequences of the dramatic growth in unauthorized immigration in recent decades. Third, the use of state-level analyses has considerable precedent in both immigration and criminological research, including studies on the etiology of crime (Duggan, 2001), the immigration process generally (Massey and Capoferro, 2008), and unauthorized immigration specifically (Durand, Massey, and Capoferro, 2005). Moreover, research findings show that many of the operative mechanisms linking macro-structural conditions to crime are invariant across cities, metropolitan areas, and states, including those that directly tap relevant theoretical constructs and measures of the social disorganization framework, such as structural disadvantage (e.g., poverty), family structure, and population composition (Land, McCall, and Cohen, 1990). Thus, the utilization of state-level data is useful for informing the contrasting theoretical perspectives motivating this study. Finally, state-level analysis is apt because it decreases the amount of sampling variability in the unauthorized estimates (compared with smaller units of analysis) and captures the entire at-risk population for the outcome of interest (crime rates) as well as the total undocumented population. As such, this analysis provides an opportunity for us to examine the undocumented immigration–violence link across the entire United States and to make generalizable conclusions that are not limited to select jurisdictions (e.g., Chicago). This point is especially significant for although much of the previous immigration–crime research has utilized data from smaller units of analysis (e.g., cities), immigration policy is overwhelmingly the purview of the federal government. Thus, understanding the more general effect of undocumented immigration on crime is paramount for informing policy discussions.

DEPENDENT VARIABLES

We analyze the four Part I offenses that comprise the violent crime index (per 100,000): murder, robbery, aggravated assault, and rape.5 Most of the immigration–crime research has been aimed at examining violent crime (Ousey and Kubrin, 2017), and the violent crime index is one of the most widely used standards for assessing patterns of violent offending (Mosher, Miethe, and Phillips, 2002). Following common practice, we log each crime measure to reduce positive skewness. Throughout the analysis, we first examine the overall violent crime rate and then investigate each crime category separately.

Focal Measure

The lack of criminological research on undocumented immigration is mainly a result of data constraints. Until recently, researchers have not had access to trustworthy estimates of the undocumented population (Warren and Warren, 2013). We use statelevel estimates from two reliable and respected sources of the undocumented immigrant population—The Center for Migration Studies (CMS) and the Pew Research Center (Pew). From both sources, we calculate the proportion of the total population that is undocumented. Although state-level undocumented estimates are available from CMS for the full study period, Pew estimates are only available intermittently up until 2005. For this reason, we use CMS data in our main analysis and we replicate the results with the available Pew figures in the methodological appendix provided in the online supporting information.6 The utilization of estimates from two independently derived sources serves as a robustness check for the analytical approach.

Pew Research Center Estimates

The Pew counts are perhaps the most widely used estimates of the undocumented immigrant population by news outlets, academics, and policy makers. In calculating the unauthorized estimates, Pew uses a residual methodology based on Census Bureau data. Variations of the residual method have been extensively used and are generally accepted as the best current estimates of the unauthorized population (Passel and Cohn, 2009). Indeed, independent research using various methods of triangulation, including death and birth records, have substantiated the general accuracy of the residual methodology (Bachmeier, Van Hook, and Bean, 2014; Van Hook, 2016). Stated briefly, this method involves subtracting the number of authorized, or documented immigrants, from the total foreign-born population. The remainder, or residual, is then the estimated number of potentially unauthorized immigrants. Because this residual count of possible unauthorized immigrants often overestimates the actual count, they use probabilistic methods7 based on demographic, social, economic, and geographic characteristics of immigrants to classify them as lawful or unauthorized (Passel and Cohn, 2015). State-level estimates of the undocumented population were available from Pew reports for the following years: 1990, 1995, 2000, and then 2005–2014. We linearly interpolate the intervening years to account for the missing Pew estimates.

Center for Migration Studies Estimates

Like the Pew, the CMS uses the residual method based on census data but significantly improves on this technique by accounting for the components of population change (Warren and Warren, 2013).8 The CMS methodology involves four key steps. First, like the Pew probabilistic methodology, the CMS applies logical edits when calculating residuals (Warren, 2014). These logical edits serve as tools to identify as many lawful resident respondents as possible and are derived from survey responses that are unlikely to apply to someone who is of unauthorized status (e.g., occupations that require legal status and those that receive public benefits that are restricted to legal residents). Second, the CMS calculates independent population controls by country of origin for unauthorized residents, a feature unique to the CMS estimates (Warren, 2014: 308). This second stage is important because the percentage of undocumented immigrants among the foreign-born population can vary considerably based on national origin. Third, with the population controls from step two, final selections are made of individual respondents to be classified as undocumented. Lastly, these estimates are adjusted by the factors that influence yearly fluctuations in the unauthorized population: emigration rates, under-count rates, removals, adjustments of unauthorized to lawful status, and mortality rates.

In addition to providing full data coverage for the study period, there are multiple advantages and sources of validation regarding the veracity of the CMS estimates. For one, unlike alternative sources, the CMS routinely includes estimates of the annual net change in unauthorized populations (undocumented immigrants leaving and entering in a given year), as opposed to simply focusing on entrants. In addition, the CMS estimates produce smaller ranges of sampling error than other sources, thus, providing greater precision for estimating any effects of undocumented immigration on crime. Finally, the CMS methodology has been empirically vetted through the peer-review process (Warren and Warren, 2013; Warren, 2014).

The estimates from both Pew and CMS are notably similar and consistent across years (within-state r = .93). The limited variability between Pew and CMS data offers suggestive evidence that they are accurately measuring the unauthorized populace. As Warren (2014: 309) stated, “the close correspondence between estimates derived from such disparate approaches indicates that they are measuring approximately the same population.”

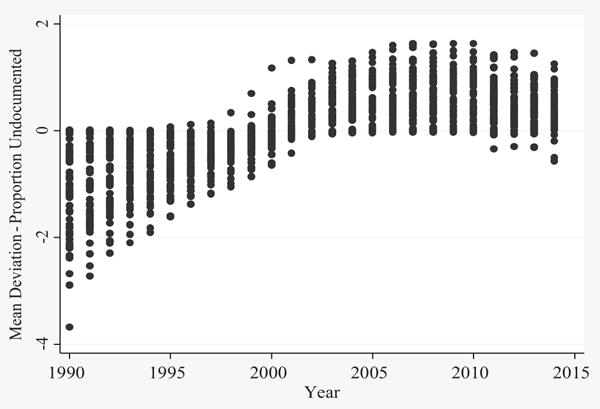

We provide a graphic summary of the CMS measure in figure 1. Because we focus our analysis on within-state change (detailed later), figure 1 shows the annual distribution of mean deviations in the proportion undocumented (i.e., how each state deviates from its mean over time). This figure demonstrates a uniform increase in the proportion undocumented between 1990 and 2014, offering little evidence of significant outliers in the focal independent measure.

Figure 1. Annual Mean Deviations in Estimated Proportion Undocumented (CMS), 1990–2014.

ABBREVIATION: CMS = Center for Migration Studies.

INDEPENDENT VARIABLES

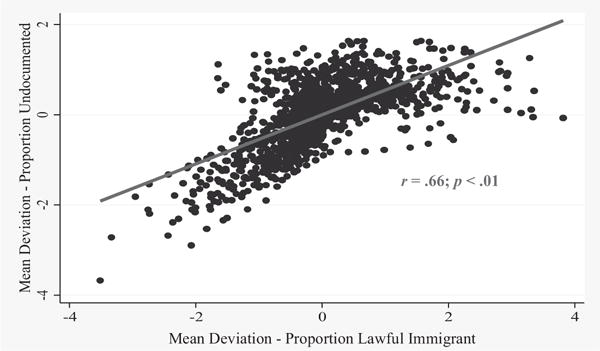

To help understand the undocumented immigration–violence relationship, we include a host of important structural factors that have featured prominently in macrocriminological research. Particularly significant among the controls is the lawful immigrant population (proportion of the population that are lawful immigrants).9 During the same period undocumented immigration increased, there was marked growth in lawful immigration as well. We illustrate these trends in figure 2. In line with our focus on withinstate change, this scatterplot shows the correlation between changes in undocumented immigration (y-axis) and changes in lawful immigration (x-axis). Although not identical, these trends unsurprisingly track one another (r = .66; p < .01).10 Therefore, to separate the effects of unauthorized immigration from general migration trends, accounting for the lawful immigrant population is critical.

Figure 2. Bivariate Longitudinal Association between Lawful and Undocumented Immigration (CMS), 1990–2014.

ABBREVIATION: CMS = Center for Migration Studies.

A second salient consideration includes measures that capture the degree of structural disadvantage (Peterson and Krivo, 2005). In line with previous immigration–crime research (Ousey and Kubrin, 2014), we use principal component methods to capture the entanglement of poverty, racial composition, and other social problems (Morenoff and Sampson, 1997). Specifically, the index of structural disadvantage is characterized by high factor loadings for the percentage of the population below the poverty line (i.e., the poverty rate), the percentage of non-Hispanic Blacks in the total population, the percentage of children born to unmarried women, and the percentage of the population older than 25 years of age without high school degrees (i.e., low educational attainment).11 Following previous research (Land, McCall, and Cohen, 1990), we include a separate indicator for the unemployment rate to measure annual fluctuations in the job market. We also capture contemporary shifts in the macro-economic climate away from industrial labor to high-skilled sector jobs by measuring the percentage of people in the manufacturing industry and the percentage of people employed in managerial or professional occupations.

To account for potential changes in the age distribution, we include a measure for the percentage of the population between ages 18 and 24. Given that urban areas experience a disproportionate amount of violent crime, we also include a measure for the percentage of the population living in urban areas.12

Consistent with the body of work documenting the links between drug activity, gun availability, and violent crime (see Blumstein, 1995; Fryer et al., 2013), combined with the public perception that undocumented immigration is associated with illicit drug markets and violence (Martinez, 2002), we include proxy measures for both criminogenic factors. Following previous research, we use CDC death records to measure gun availability as the percentage of suicides committed by firearm (cf. Kubrin and Wadsworth, 2009) and the prevalence of drug markets by including a measure for the drug overdose mortality rate (see Light and Ulmer, 2016, for a similar application). In supporting analyses, we supplement the overdose measure with a measure of drug arrests and find substantively identical results (see point 11 in the methodological appendix in the online supporting information).

To examine the possibility that undocumented immigration decreases crime by increasing formal social control, we include a measure for the number of police officers (per 100,000). We also account for one of the most significant criminal justice and societal changes in recent decades: the dramatic expansion of the prison system. Between 1970 and 2010, the incarceration rate in the United States increased over fivefold, from 96 (per 100,000) to 500 (per 100,000) (compare Renshaw, 1982, to Carson, 2015). Of this prison population growth, nearly 60 percent took place after 1990. Given the evidence linking increased punishment to lower crime (Johnson and Raphael, 2012; Levitt, 1996), we include a measure for the incarceration rate (per 100,000) so that any undocumented immigration effects are not confounded by this notable shift in criminal justice policy.

ANALYTICAL STRATEGY

We leverage the longitudinal nature of our data by including state and year fixed effects in our regression models. By focusing on within-state change, the use of fixed-effects estimators removes the effects of all time-invariant causes of violent crime (whether measured or not) that potentially confound the unauthorized immigration–violence relationship (Firebaugh, 2008). Direct analytical comparisons between random and fixed effects using the Hausman test (Hausman, 1978) demonstrate that the coefficient vector in our data is inconsistent using random effects, thus, preferencing the fixed-effects specification. Moreover, our inclusion of state fixed effects eliminates the effects of cross-state variations in reporting and data collection methods. In the same vein, the use of year fixed effects accounts for any unmeasured trends that influenced crime rates nationally. Fixed effects also help address issues of measurement error in the undocumented estimates in two primary ways. First, to the extent that there is a national pattern of systematic underor over-counting of the undocumented population, this is accounted for by the year fixed effects that adjust the model parameters for all unmeasured trends that affected states equally. Second, to the extent that there are unique challenges to estimating the unauthorized population in each state (i.e., California over-counts but Illinois under-counts), the utilization of state fixed effects addresses this issue by examining only within-state variation, so long as any measurement error is stable over time.

To ensure proper time ordering, we lag all independent variables by one year in the regressions so that changes in the predictors precede changes in violent crime. Finally, we account for nonindependence in the underlying error variance–covariance matrix by reporting robust standard errors clustered by state.

RESULTS

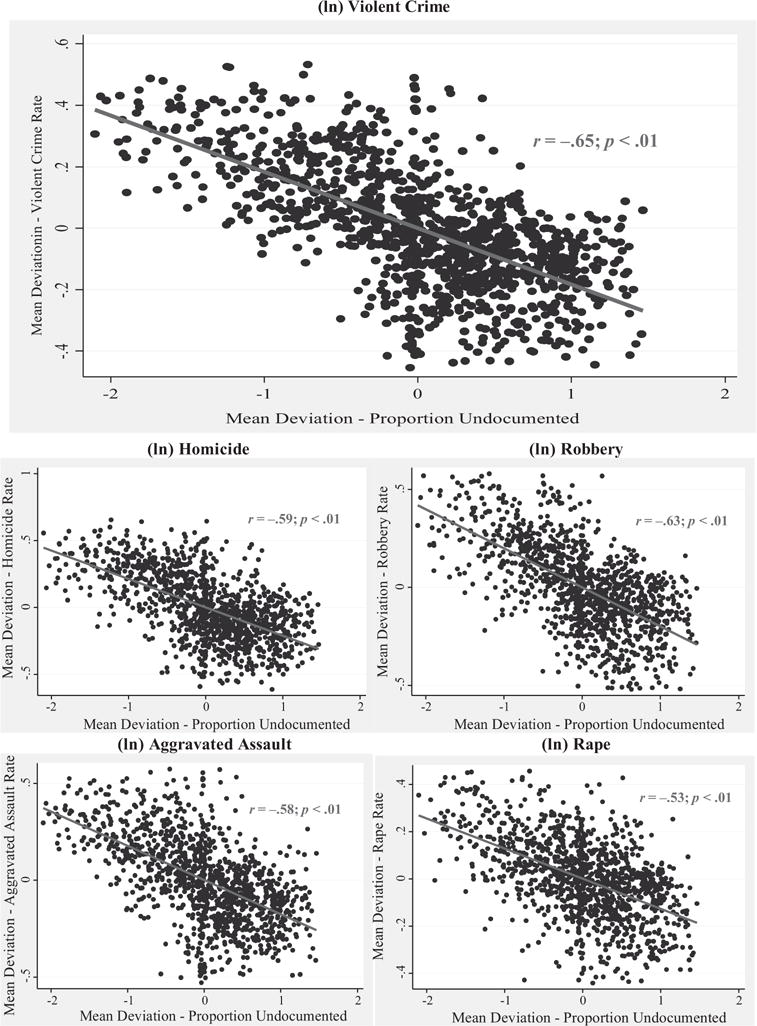

We begin our analysis by first considering the bivariate associations between undocumented immigration and violence since 1990. Correlations between state-level mean deviations in the proportion undocumented (x-axis) and mean deviations in each of the violent crime measures (y-axis) between 1990 and 2014 are shown graphically in figure 3.13 The overall patterns in the data are consistent across each dependent variable: Increases in the undocumented immigrant population within states are associated with significant decreases in the prevalence of violence. This set of findings runs contrary to the marginalization and disorganization perspectives. Nevertheless, though descriptive trends represent the necessary first step in any causal inquiry, they are hardly conclusive. We thus turn to our fixed-effects regression models to scrutinize more rigorously the undocumented immigration–crime relationship.

Figure 3. Bivariate Longitudinal Associations Between Undocumented Immigration and Violent Crime, 1990–2014.

NOTES: Crime rates expressed on a logarithmic scale. Undocumented immigration measures are not lagged.

Table 2 presents a series of six regression models examining the association between within-state changes in undocumented immigration and within-state changes in violent crime. The first column reports a baseline regression model in which violent crime is predicted only by the immigration measures (lawful and undocumented) and the state and year fixed effects. From there, models 2–5 increase in empirical rigor by adding measures that tap the theoretical processes discussed earlier. Even though in most immigration– crime studies the analyses are not weighed,14 scholars in this area have recently shown that the results can be sensitive to weighting (Chalfin, 2014). Thus, model 6 replicates the specification in model 5, but weights the regression by state population, in effect giving greater weight to the larger states in the analysis.

Table 2.

Fixed Effects Models of Undocumented Immigration on State-Level Violent Crime Rates, 1990–2014

| Measures | Model 1 (In) |

Model 2 (In) |

Model 3 (In) |

Model 4 (In) |

Model 5 (In) Violence |

Model 6 (In) Violence |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | b | b | b | b | β | b | β | |

| Focal Variable | ||||||||

| Undocumented immigration | −.13** (.04) |

−.13*** (.03) |

−.12*** (.03) |

−.12*** (.03) |

−.12*** (.03) |

−.37 | −.05* (.02) |

−.28 |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Lawful immigration | −.07** (.02) |

−.09** (.03) |

−.08*** (.02) |

−.08*** (.02) |

−.08*** (.02) |

−.72 | −.07*** (.02) |

−1.08 |

| Crime prone ages (18–24) | .08* (.03) |

.06* (.03) |

.07* (.03) |

.07* (.03) |

.010 | .03 (.02) |

.05 | |

| Urban | .02† (.01) |

.03* (.01) |

.03* (.01) |

.03* (.01) |

.69 | .02* (.01) |

.68 | |

| Structural disadvantage | .08 (.05) |

.09† .05) |

.09† (.05) |

.16 | .10* (.04) |

.18 | ||

| Unemployment | −.03* .01) |

−.03* (.01) |

−.03* (.01) |

−.09 | −.02* (.01) |

−.08 | ||

| Manufacturing | .02† (.01) |

.02† (.02) |

.02† (.01) |

.18 | .02† (.01) |

.17 | ||

| Managerial / professional | .01 (.01) |

.01 (.01) |

.01 (.01) |

.01 | .02* (.01) |

.19 | ||

| Gun availability | .00 (.00) |

.00 (.00) |

.04 | .002 (.003) |

.06 | |||

| Drug activity | .00 (.01) |

.00 (.01) |

.02 | .01* (.01) |

.14 | |||

| Incarceration rate | .00 (.00) |

−.01 | .0002 (.0001) |

.08 | ||||

| Police per capita | .00 (.00) |

.04 | .0002 (.0003) |

.02 | ||||

| Constant | 6.44*** (.04) |

4.37*** (.93) |

3.79*** (.95) |

3.62** (1.01) |

3.57** (1.02) |

4.05*** (.83) |

||

| Specification and Summary Information | ||||||||

| State effects? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Year effects? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Weighted? | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | ||

| R2 | .93 | .94 | .94 | .94 | .94 | .94 | ||

| N | 1209 | 1209 | 1209 | 1209 | 1209 | 1209 | ||

NOTE: All independent variables are lagged by one year. Robust clustered Std. Errors reported in parentheses. ABBREVIATIONS: b = unstandardized coefficient, β = standardized coefficient.

p < .001,

p< .01,

p < .05,

p < .10 (two-tailed tests).

Before turning to our central results, we first examine the parameter estimates of the other covariates from our full specification. The results in model 5 are remarkably consistent with those of previous research on violent crime and demonstrate the validity of our coding and model specification. Increases in structural disadvantage, urbanization, and young adults are associated with increases in criminal violence.

Next we consider the effect of our focal measure, undocumented immigration. Four points stand out from table 2. First, across every model, the results align with the bivariate findings: Increased concentrations of undocumented immigrants are associated with statistically significant decreases in violent crime. In model 5, this significant decrease is net of socioeconomic disadvantage, labor market conditions, population age structure, urbanization, incarceration and police officer rates, the prevalence of guns and drugs, as well as state and year fixed effects. Interpreted substantively, a one-unit increase in the proportion of the population that is undocumented corresponds with a 12 percent decrease in violent crime. An alternative method for gauging substantive significance is the use of standardized coefficients. According to model 5, a standard deviation increase in undocumented immigration is associated with a .37 standard deviation decrease in violent crime. Compared with the effect sizes of the other measures, this result is meaningful.

Second, across each model, the effects of unauthorized immigration are in addition to the significant reductions in violent crime stemming from lawful immigration, thus, underscoring the importance of examining these populations separately. In other words, the results across models 1–6 demonstrate that lawful and undocumented immigration have independent negative effects on criminal violence. Third, comparing the effect of undocumented immigration across models 1–5 reveals that the measured covariates do little to explain the relationship between unauthorized immigration and violence. That is, although measures of population age structure, urbanization, and unemployment all significantly predict violent crime, none of these factors changes the substantive relationship between violence and unauthorized immigration. One partial explanation for this could be the selection of undocumented immigrants based on low criminal propensities. As Sampson (2008: 30) explained, “to the extent that more people predisposed to lower crime immigrate to the United States, they will sharply increase the denominator of the crime rate while rarely appearing in the numerator.” If this is the case, undocumented immigrants would decrease the prevalence of violence regardless of changes in other statelevel factors, which is what we find.

Lastly, when comparing models 5 and 6, the direction and efficiency of the undocumented estimates are unaffected by weighting, though the magnitude decreases when weighted by population size. In the weighted model, a one-unit increase in the proportion undocumented corresponds to only a 5 percent reduction in violent crime.

Next, because the overall violence rate may mask important distinctions across offense types, we examine the individual violent crime categories in table 3. For parsimony, we report only the undocumented results but note that the independent variable specifications across all models are identical to those in table 2 (full results available on request). As with the previous analysis, we report both the unweighted (panel A) and weighted (panel B) results.

Table 3.

Fixed Effects Models of Undocumented Immigration on State-Level Homicide, Robbery, Assault, and Rape Rates, 1990–2014

| Panel A: Unweighted | (In) Homicide b |

(In) Robbery b |

(In) Assault b |

(In) Rape b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focal Variable | ||||

| Undocumented immigration | −.08* (.03) |

−.11*** (.03) |

−.12** (.04) |

−.10*** (.02) |

| Specification and Summary Information | ||||

| State effects? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year effects? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Weighted? | No | No | No | No |

|

| ||||

| Panel B: Weighted |

(In) Homicide b |

(In) Robbery b |

(In) Assault b |

(In) Rape b |

|

| ||||

| Focal Variable | ||||

| Undocumented immigration | −.05 .04 |

−.05† 03 |

−.04 .02 |

−.09** .03 |

| Specification and Summary Information | ||||

| State effects? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year effects? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Weighted? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

NOTE: Number of observations = 1209. Models in Panel B are weighted by state population. Models include controls for lawful immigration, age structure, urbanization, structural disadvantage, unemployment, manufacturing and managerial employment, gun availability, drugs, incarceration, and police per capita. Independent variables are lagged by one year. Robust clustered Std. Errors reported in parentheses.

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05,

p < .10 (two-tailed tests).

Beginning with panel A, the undocumented findings for murder, robbery, assault, and rape all paint the same picture. Despite substantial differences in official reporting rates across these offenses, as undocumented immigration increased in recent decades, there was a significant, concomitant decrease in each measure of violent crime. The results in panel B show that these findings are somewhat sensitive to weighting. Although the direction of the relationship is invariant, the weighted estimates are generally lesser in magnitude and measured with less precision, with fewer significant effects. The differences in the weighted and unweighted regression models in tables 2 and 3 are suggestive of heterogeneity in the effect of undocumented immigration on violent crime across different types of states. We investigate whether the findings are driven by a small subset of influential cases in the online supporting information, and we return to the issue of heterogeneity in the Discussion section.

Taken together, the weight of the evidence presented thus far contradicts predictions derived from marginalization and disorganization perspectives. Rather than causing higher crime, increased undocumented immigration since 1990 is generally associated with lower rates of serious violence, although this relationship seems qualified depending on the specific type of violence and weighting scheme. The following sections test the robustness of these findings.

SELECTIVE MIGRATION

Even with the inclusion of multiple theoretically informed measures and state and year fixed effects, challenges to causal inference remain because of the selective nature of undocumented migration. That is, the observed negative findings could be biased by undocumented immigrants relocating to areas to avoid violence. For this reason, it is vital to account for the selection process of settlement patterns for undocumented immigrants to break this potential simultaneity (MacDonald, Hipp, and Gill, 2013).

We address these endogeneity concerns by using an instrumental variable approach (Angrist and Pischke, 2008), where the undocumented immigrant population in 1980 (derived from Warren and Passel, 1987) is used as an instrument to predict the undocumented population in subsequent decades. The 1980 unauthorized population serves as a useful instrument based on the idea that undocumented immigrants will selectively migrate to places where they have preexisting social ties. This demographic process is confirmed by both rich ethnographic accounts and quantitative research on undocumented immigration (Chavez, 2013; Ryo, 2013). Not only do potential migrants rely on social ties to gain guidance in crossing the border to the United States (Singer and Massey, 1998), but social capital and cumulative causation theory also suggest that undocumented immigrants would be more likely to cross the border if they knew migrants who had already done so (Massey, 1990). Moreover, as each consecutive cohort of migrants makes its way to the United States, potential undocumented immigrants gain social capital that increases their odds of migrating (Massey and Zenteno, 1999). In short, the selective migration choices of undocumented immigrants between 1990 and 2014 should be strongly related to the concentration of undocumented immigrants in 1980.

The results from the first stage shown in table 1 of the online appendix confirm this point. In line with theoretical accounts, the unauthorized population in 1980 is a significant predictor of increased undocumented immigration between 1990 and 2014 and this relationship is robust to the inclusion of year fixed effects and state-level controls, including the lawful immigrant population, which further demonstrates the importance of examining these populations separately. This finding may reflect the fact that even though chain migration also influences lawful immigration (Palloni et al., 2001), undocumented immigrants are likely far more dependent on social networks. That is, although documented immigrants can pursue educational and economic opportunities even when immigrant networks are scarce or nonexistent, the options for undocumented immigrants are more severely constrained by the availability of social networks. Moreover, the diagnostic statistics confirm the strength of the relationship between the instrument and treatment variables (F statistic > 10; Staiger and Stock, 1997).

Thus, the instrument satisfies the condition that it is predictive of variation in undocumented immigration, however, as identified in similar strategies adopted by MacDonald, Hipp, and Gill (2013); Lyons, Vélez, and Santoro (2013); and Spenkuch (2014), the 1980 undocumented population should be theoretically independent of the change in crime rates during this period. As a result, this model breaks the simultaneity between undocumented immigration and crime and provides an exogenous test of the effect of increased undocumented immigration between 1990 and 2014 on changes in violence during this period.

In table 4, we present the IV estimates of the relationship between unauthorized immigration and changes in each measure of violence. Because the instrument is not time varying, we follow the approach of Ousey and Kubrin (2014) and express all of the data as first-differences. This approach serves two important functions. First, like fixed effects, differencing adjusts for all time constant between state differences. Second, as illustrated by Spelman (2008), differencing helps address nonstationarity in crime trends within state-panel data sets. As with the main analysis, we report the unweighted (panel A) and weighted (panel B) results separately. Also consistent with the presentation of the results of the main analysis, we only display our focal results but note that all covariates are included in the IV models.

Table 4.

First-Difference Instrumental Variable Models of Undocumented Immigration and Violent Crime, 1990–2014

| Panel A: Unweighted | (In) Violence

|

(In) Homicide

|

(In) Robbery

|

(In) Assault

|

(In) Rape

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | |

| Focal Variable | ||||||||||

| Δ Undocumented immigration | −.46** (.15) |

−.50* (.19) |

−.50** (.17) |

−.55* (.21) |

−.50** (.16) |

−.55* (.21) |

−.40* (.15) |

−.42* (.18) |

−.27* (.11) |

−.30* (.14) |

| Specification and Summary Information | ||||||||||

| Year effects? | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Weighted? | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

|

| ||||||||||

| Panel B: Weighted |

(In) Violence

|

(In) Homicide

|

(In) Robbery

|

(In) Assault

|

(In) Rape

|

|||||

| b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Focal Variable | ||||||||||

| Δ Undocumented immigration | −.64* (.25) |

−1.58 (2.37) |

−.78** (.26) |

−2.01 (2.92) |

−.68** (.24) |

−1.76 (2.49) |

−.59* (.26) |

−1.38 (2.18) |

−.44† (.22) |

−1.06 (1.69) |

| Specification and Summary Information | ||||||||||

| Year effects? | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Weighted? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

NOTE: Number of observations = 1204. Models in Panel B are weighted by state population. The instrument is the state-level undocumented population in 1980. All variables are expressed as first-differences. Models include controls for lawful immigration, age structure, urbanization, structural disadvantage, unemployment, manufacturing and managerial employment, gun availability, drugs, incarceration, and police per capita. Independent variables are lagged by one year. Robust clustered Std. Errors reported in parentheses.

p < .01,

p < .05,

p < .10 (two-tailed tests).

The IV results in panel A are entirely consistent with the fixed-effects findings; net of controls and year fixed effects, unauthorized immigration has a marked and significantly negative relationship with each measure of violent crime. Thus, the findings suggest that the negative effects observed in the fixed-effects models are not driven by selection to avoid criminality. Like the fixed-effects analysis, however, the results in panel B suggest that these findings are somewhat sensitive to weighting. Including state population weights increases the magnitude of the unauthorized effects considerably, especially when we introduce year effects. These more pronounced effects, however, are measured imprecisely. Overall, of the 20 effects shown in table 4, all of them are negative and 14 of them are significant at the p < .05 level. Given this pattern in the data, the results provide further evidence that unauthorized immigration is, in general, negatively associated with violent crime. At the very least, they seriously undermine claims that violent crime has increased as a result of undocumented immigration.

LESS CRIME OR LESS REPORTING?

The pattern of results presented thus far suggests that undocumented immigration is generally associated with less violent crime. Nevertheless, because we are using official crime statistics, there is a plausible alternative interpretation: Increased unauthorized immigration results in fewer crimes reported to the police. In other words, those who lack legal status, and potentially their lawful friends and family members as well, may be hesitant to report violent victimizations to avoid detection from legal officials (Gutierrez and Kirk, 2017). If this is the case, our results may reflect less reporting rather than less crime. Although this concern is obviated for the case of homicide, it potentially applies to nonfatal forms of violence such as robbery and assault.

To gain leverage on this question, we use data from the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS). The NCVS is an annual, nationally representative survey of approximately 90,000 households (~160,000 persons) on the frequency of criminal victimization and the likelihood of crime reporting in the United States. For our purposes, the NCVS has several principle strengths. First, like the U.S. Census, the sampled households include both lawful and undocumented immigrants (Addington, 2008). Second, the NCVS includes Spanish and alternative language questionnaires and the household response rate is exceptionally high (~85% to 90%; NCVS Technical Documentation, 2014). Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, the survey asks about crimes that were, and were not, reported to the police, thus, capturing what criminologists often refer to as the “dark figure of crime”—crimes that occur but go unreported. For this reason, “the NCVS is considered the most accurate source of information on the true volume and characteristics of crime and victimization in the United States” (Gutierrez and Kirk, 2017: 932). In 2015, the Bureau of Justice Statistics for the first time released state-level estimates for the NCVS for the period 2000–2012 (Fay and Diallo, 2015). To reduce random variations in annual estimates and better identify long-term crime trends, these estimates were reported in 3-year averages (i.e., 2000 represents the 1999–2001 average). These data are available for all 50 states (plus Washington, DC) for 13 years (663 state-years), but with missing data on other measures, the sample is reduced to 651 state-years. We use these data to examine whether undocumented immigration is associated with decreasing victimization rates as well as officially reported crime rates in table 5.

Table 5.

Fixed Effects Models of Undocumented Immigration on State-Level Violent Victimization Rates, 2000–2012

| Panel A: Unweighted | (In) NCVS Violence b |

(In) NCVS Robbery b |

(In) NCVS Assault b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Focal Variable | |||

| Undocumented immigration | −.08 (.05) |

−.14t (.07) |

−.13† (.07) |

| Specification and Summary Information | |||

| State effects? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year effects? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Weighted? | No | No | No |

|

| |||

| Panel B: Weighted |

(In) NCVS Violence b |

(In) NCVS Robbery b |

(In) NCVS Assault b |

|

| |||

| Focal Variable | |||

| Undocumented immigration | −.14* (.06) |

−.22** (.08) |

−.21 * (.08) |

| Specification and Summary Information | |||

| State effects? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year effects? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Weighted? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

NOTE: Number of observations = 651. Models in Panel B are weighted by state population. Models include controls for lawful immigration, age structure, urbanization, structural disadvantage, unemployment, manufacturing and managerial employment, gun availability, drugs, incarceration, and police per capita. Independent variables are lagged by one year. Robust clustered Std. Errors reported in parentheses.

p < .01,

p < .05,

p < .10 (two-tailed tests).

For this analysis, we use the NCVS measures of violent crime, robbery, and assault (per 1,000 persons, logged).15 The independent variable and weighting specifications are identical to the UCR models.16 Overall, the pattern of results from the NCVS analysis are remarkably consistent with the UCR findings: Net of covariates and state and year fixed effects, increased undocumented immigration is negatively associated with violent victimization, robbery victimization, and assault victimization. In all but one model, these effects are significant at the p < .10 level. Regarding weighting, the magnitude changes with the inclusion of state population weights, with effect sizes roughly 50–75 percent larger in the weighted models. Weighting also improves the precision of estimates, with each effect significant at the p < .05 level. Like the UCR results, these differences from weighting suggest heterogeneity in the effect of undocumented immigration on rates of violent victimization across states.

Overall, the NCVS results demonstrate that the findings reported in the main analysis are more likely reflective of less crime, not just less reporting. Though it remains possible that the NCVS results are driven by nonresponse bias among undocumented immigrants, several points suggest this is unlikely to be the case. First, this would not explain the homicide findings, which preclude reporting omissions, and homicide rates tend to parallel trends in overall violent crime substantially (the correlation between murder and the NCVS robbery rate in our data is .83). Second, if nonresponses were driving the NCVS results, we might expect to see substantial differences in nonresponse rates for racial/ethnic groups more likely to be undocumented. But we find little evidence for this. The average response rate for Hispanics in the NCVS for 2011–2013—the largest ethnic group among the undocumented—was 86 percent, which is in line with non-Hispanic Blacks (86 percent) and non-Hispanic Whites (88 percent; NCVS Technical Documentation, 2014). Nevertheless, given the inherent difficulty of reaching the undocumented population, the likelihood of nonresponse bias cautions us against drawing firm conclusions, at least in terms of victimization among the undocumented. That said, the consistent patterns between undocumented immigration and violence in both the UCR and NCVS data are not easily dismissed.

FURTHER ROBUSTNESS CHECKS

Space constraints limit the full inclusion of our supplemental analyses. Thus, we direct interested readers to the methodological appendix in the online supporting information for further elaboration of the robustness of our results. There we address, in detail, a host of methodological questions including adjustments for measurement error in the undocumented estimates, replication with the Pew measures, alternative specifications of the independent variables, alternative measures of drug crime, time ordering, autoregressive models, unlogged dependent variables, Arellano–Bond panel models, and robust regression to examine the impact of outliers. In all cases, the underlying pattern in the data remains unchanged.

DISCUSSION

The immigration–crime nexus has been at the fore of criminological inquiry for nearly a century. Yet, to date, research on the criminological consequences of the influx of more than 11 million undocumented immigrants in recent decades remains understudied. This relative dearth in our knowledge is significant given that 1) the unauthorized population is by far the most divisive feature of contemporary immigration; 2) the U.S. government has devoted billions of criminal justice resources aimed at increasing public safety by reducing undocumented immigration; and 3) there are salient theoretical reasons to think lawful and unauthorized immigration may have independent influences on crime.

To address this gap, we leverage the availability of recently developed estimates of the undocumented population to provide a longitudinal investigation into the effect of unauthorized immigration on violence between 1990 and 2014. Our findings suggest that undocumented immigration over this period is generally associated with decreasing violent crime. The negative association between unauthorized immigration and violence is evident in both police reports and victimization data; simple procedures such as bivariate associations; more stringent multivariate tests in which numerous theoretically relevant measured and unmeasured confounding variables are accounted for; instrumental variable analyses that model the selective migration patterns of undocumented immigrants; and a variety of supplemental models and sensitivity analyses. Indeed, of the 57 point estimates reported throughout our analysis (including in the online supporting information), not one shows a positive association between undocumented immigration and violent crime. Such findings diverge from the cross-sectional results reported by Green (2016). In this regard, we exhibit a familiar pattern in immigration–crime research: The results of cross-sectional analyses tend to demonstrate a weak positive immigration–crime association, whereas the results of longitudinal analyses more often show significantly larger, negative effects. Given the more rigorous research design longitudinal analyses afford, we concur with Ousey and Kubrin (2017: 1.13) that “the stronger, negative, and statistically significant association that emerges from … longitudinal studies may be due more weight than the weak and nonsignificant association that emerges from … cross-sectional studies.”

Although the pattern in the data is clear, not all of the effects are significant. Thus, we interpret these results with appropriate caution and identify several fruitful avenues for future research. The notable distinctions between the weighted and unweighted regressions suggest that the effect of undocumented immigration on violent crime may vary across different types of states. Thus, a logical extension of this article would be to explore the undocumented–violence nexus across different contexts. This approach would align with current efforts to examine variation in the relationship between Latino immigration and crime across traditional and new immigrant-receiving communities (Shihadeh and Barranco, 2013). Related to this point, though the use of state-level data helps ameliorate concerns regarding sampling variability, states likely miss important communitylevel processes. Thus, as methods for enumerating the unauthorized population improve, researchers would do well in the future to consider the macro-level influence of undocumented immigration on crime at more proximal units of analysis, such as cities or neighborhoods. Within this vein, they should consider how the context of reception might moderate the undocumented–crime nexus. For example, Lyons, Vélez, and Santoro (2013) showed that immigration reduces criminal violence more in cities with pro-immigration policies, such as “sanctuary” policies that formally limit local law enforcement cooperation with immigration authorities, than in cities with a less receptive political climate for immigrants. Similar analyses specific to undocumented immigration, however, await future data collection efforts as longitudinal information on the unauthorized population at lower levels of aggregation is currently unavailable.

Additionally, extending this line of inquiry beyond violent crime is an important consideration for further research. Property offenses may be particularly interesting as there are theoretical reasons to suspect undocumented immigration may have divergent effects on violent and property crime. For example, economic theory suggests that unauthorized immigrants may be criminally motivated by financial gain if few legitimate economic options are available to them. In line with this view, Baker (2015) found that the legalization of nearly 3 million unauthorized immigrants from the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 resulted in significant decreases in property crime. By implication, with increasing numbers of policies and practices at the state and federal levels aimed at economically marginalizing undocumented immigrants, it is plausible to expect an increase in property crime as a result.

Another important area for further inquiry concerns the social processes through which undocumented immigration influences violent crime. Although we accounted for a multitude of macro-social constructs in our analysis, future research is needed to explicate the mechanisms linking unauthorized immigration and violence. Given our findings demonstrating the stability of the undocumented–violence association with and without covariates, we think more explicit focus on difficult-to-measure processes such as informal social control, cultural penetration, and selection may be useful for understanding how undocumented immigration affects criminal violence.

Lastly, it should be noted that we did not examine the impact of transnational criminal organizations that operate along the border (e.g., drug cartels). Rather, in line with virtually all immigration–crime research, we examined how the settlement of foreign-born individuals affects crime in the United States.

Mindful of these limitations, we nonetheless provide insight into an important criminological question by offering suggestive evidence that undocumented immigration (independent of overall immigration) may have contributed to the U.S. drop in recent decades. This finding has significant theoretical and policy implications. In reference to criminological theory, our results run directly counter to predictions rooted in economic marginalization and social disorganization. Originally articulated to explain the high rates of crime in the Polish immigrant communities of Chicago at the beginning of the 20th century, more and more researchers have recently questioned the thesis that today’s immigrants disrupt community organization and increase crime (Sampson, 2008). Nevertheless, few had explicitly looked at undocumented immigrants. Given the tremendous economic, social, and legal barriers undocumented immigrants face, this is a stringent test of the marginalization–disorganization perspectives. That is, if certain aspects of contemporary immigration increase crime by destabilizing communities through economic hardship, we should observe this relationship when examining undocumented immigrants. Our results, however, cast doubt on traditional social disorganization’s proposed process in which immigrant concentration undermines community organization. Rather, our results align more with the immigrant revitalization thesis, whereby the influx of low crime-prone undocumented immigrants combined with their supporting immigrant networks provide social and economic benefits to communities, thus, reducing the prevalence of violence.

In reference to public policy, at the most basic level, our study calls into question one of the primary justifications for the immigration enforcement build-up. Debates about the proper role of undocumented immigrants in U.S. society will no doubt continue, but they should do so in light of the available evidence. For this reason, any set of immigration policies moving forward should be crafted with the empirical understanding that undocumented immigration does not seem to have increased violent crime. This analysis also speaks to the unintended consequences of border enforcement. Although immigration enforcement may have “backfired” by increasing the population of undocumented immigrants (Massey, Pren, and Durand, 2016), this policy blunder has not come at the expense of public safety. This finding provides clarifying context for why the most ambitious policies aimed at removing “criminal aliens” have not yielded sizeable reductions in crime. For example, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Secure Communities (S-Comm) Program was designed specifically as a crime-fighting initiative to identify and deport criminal aliens through state and local collaboration with federal immigration authorities. Despite the fact that by 2013 S-Comm was active in nearly every county and the deportation of aliens with criminal records increased substantially under the program, the results of comprehensive analyses revealed no impact of S-Comm on violent crime (Miles and Cox, 2014; Treyger, Chalfin, and Loeffler, 2014). Our results help explain why; undocumented immigrants do not increase violence. It is for this reason that other policies specifically targeting unauthorized immigrants, such as Arizona’s SB 1070 (2010) and Alabama’s HB 56 (2011), are unlikely to deliver on their crime reduction promises.

Although ardent skeptics may remain unconvinced, the weight of the evidence presented here and in supporting work challenges claims that unauthorized immigration endangers the public. At a minimum, the results of our study call into question claims that undocumented immigration increases violent crime. If anything, the data suggest the opposite.

Supplementary Material

Appendix Table 1. First-Stage Effect of the Undocumented Population in 1980 on the Concentration of Undocumented Immigrants between 1990 and 2014: First-Difference Regression Model

Appendix Table 2. Fixed Effects Models of Undocumented Immigration on Crime: Robustness Checks

Appendix Table 3. First-Difference Models of Undocumented Immigration on State-Level Violent Victimization Rates, 2000–2012

Biographies

Michael Light is an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. His research is primarily focused on crime, punishment, and immigration.

Ty Miller is a PhD candidate in sociology at Purdue University and an incoming assistant professor of sociology and criminology at Winthrop University. His research interests include crime, public policy, substance use, and immigration.

Footnotes

Additional supporting information can be found in the listing for this article in the Wiley Online Library at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/crim.2018.56.issue-2/issuetoc.

A previous version of this article was presented at the 2017 American Sociological Association annual meeting in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, and at the 2017 American Society of Criminology annual meeting in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. We are deeply indebted to several of our colleagues for insightful comments on early drafts, including Ted Gerber, Chad Goldberg, Mike Massoglia, and especially Shawn Bauldry, Jason Fletcher, and Felix Elwert for invaluable methodological comments. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for improving our article.

To avoid redundancy, we use the terms “undocumented” and “unauthorized” interchangeably throughout this article.

In the past, researchers have used terms such as the “immigrant concentration view” (Desmond and Kubrin, 2009), the “ethnic community model” (Logan, Zhang, and Alba, 2002), the “enclave hypothesis” (Portes and Jensen, 1992), the “community resource perspective” (Feldmeyer, 2009), and the “Latino paradox” (Sampson, 2008) to describe these effects. Regardless of the term, for our purposes, what matters is they make the same directional hypothesis: Immigrants provide prosocial benefits in ways that reduce the prevalence of violent crime.

Authors’ calculations of data from the Center for Migration Studies.

Incarceration information is missing for Washington, DC, after 2001, after the city abandoned its prison system, and for one year in Nevada (13 total state-years). Also, data are missing on gun availability for one year in DC as a result of data suppression protocols from the CDC. Lastly, police officer information is missing for West Virginia for 2014. The results are entirely unchanged when we drop these measures from the analysis and include these years of data (results available on request).

In 2011, the definition of rape was changed in the UCR program. To ensure comparability over time in this measure, we use the “legacy” definition of rape in this study.