Abstract

Purpose

By reanalyzing the gene expression profile GSE76925 in the Gene Expression Omnibus database using bioinformatic methods, we attempted to identify novel candidate genes promoting the development of emphysema in patients with COPD.

Patients and methods

According to the Quantitative CT data in GSE76925, patients were divided into mild emphysema group (%LAA-950<20%, n=12) and severe emphysema group (%LAA-950>50%, n=11). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using Agilent GeneSpring GX v11.5 (corrected P-value <0.05 and |Fold Change|>1.3). Known driver genes of COPD were acquired by mining literatures and retrieving databases. Direct protein–protein interaction network (PPi) of DEGs and known driver genes was constructed by STRING.org to screen the DEGs directly interacting with driver genes. In addition, we used STRING.org to obtain the first-layer proteins interacting with DEGs’ products and constructed the indirect PPi of these interaction proteins. By merging the indirect PPi with driver genes’ PPi using Cytoscape v3.6.1, we attempted to discover potential pathways promoting emphysema’s development.

Results

All the patients had COPD with severe airflow limitation (age=62±8, FEV1%=28±12). A total of 57 DEGs (including 12 pseudogenes) and 135 known driving genes were identified. Direct PPi suggested that GPR65, GNB4, P2RY13, NPSR1, BCR, BAG4, and IMPDH2 were potential pathogenic genes. GPR65 could regulate the response of immune cells to the acidic microenvironment, and NPSR1’s expression on eosinophils was associated with asthma’s severity and IgE level. Indirect merging PPi demonstrated that the interacting network of TP53, IL8, CCR2, HSPA1A, ELANE, PIK3CA was associated with the development of emphysema. IL8, ELANE, and PIK3CA were molecules involved in the pathological mechanisms of emphysema, which also in return proved the role of TP53 in emphysema.

Conclusion

Candidate genes such as GPR65, NPSR1, and TP53 may be involved in the progression of emphysema.

Keywords: emphysema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, differentially expressed genes, protein-protein interaction network analysis, candidate genes

Introduction

COPD, characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation, is the third leading cause of mortality worldwide.1 Airflow limitation is mainly due to small airway obstruction and emphysema, which have distinct physiopathologic mechanisms.2,3 Most patients with COPD have pathological alterations of both emphysema and small airway obstruction, while some have only one or no obvious change.4 Therefore, the two pathological phenotypes are regarded as potential subtypes of COPD.5

Contrary to the feature of small airway remodeling, emphysema is due to decreased deposition and excessive destruction of extracellular matrix, leading to loss of alveolar septum and attachment.6,7 However, many studies show that the pathogenesis and progression mechanism of emphysema are complex and heterogeneous, which need to be further elucidated.6,8,9

As a noninvasive tool to measure morphological indices, quantitative computed tomography (QCT) is an effective approach to determine the severity of COPD and distinguishing the above subtypes.10 Its assessment of emphysema has been demonstrated to be reliable, correlating well with indices of lung function, microscopic manifestations of emphysema, and clinical status of COPD patients. In addition, its assessment of small airway obstruction is also well associated with FEV1%.11,12

After searching the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, which is one of the largest gene expression databases in the world, we found the original gene expression profile GSE76925 with records of QCT index.13 To investigate the inherent molecular mechanisms in emphysema subtype of COPD, by using several bioinformatics methods,14–16 we constructed the interacting network of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in this profile and known COPD driver genes to identify novel candidate genes promoting progression of emphysema.

Materials and methods

Acquisition of microarray data

The GEO database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo, May 18, 2017) was retrieved to obtain gene expression profiles of lung tissues of COPD patients. The dataset GSE76925, the only one with QCT indices, was downloaded.13 Tests for these surgically resected lung tissue samples in GSE76925 dataset were performed using the GPL10558 platform, Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 expression beadchip.

Group division and statistical analysis

After screening samples’ phenotype information (from GSM2040796 to GSM2040942), samples without records of percents of low attenuation areas <−950 Hounsfield unit on inspiratory CT (%LAA-950) were ruled out. Based on the value of %LAA-950, we divided the remaining samples into two groups, severe emphysema group (%LAA-950>50%, n=11) and mild emphysema group (%LAA-950<20%, n=12).

All the continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and t-tests were applied to make comparison between the two groups. The categorical variables were described by constituent ratio and analyzed by Pearson chi-squared test. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA, USA). A two-side P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Identification of DEGs between severe and mild emphysema groups

To explore the underlying genes, we filtered DEGs between severe and mild emphysema groups, using GeneSpring GX software v11.5 (Agilent technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at the cutoff value of corrected P-value <0.05 and |Fold Change|>1.3. We annotated them with Gene Oncology by manually retrieving Gene database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/gene, July 16, 2017) and roughly classified them according to the section of biological process in Gene Oncology17 by retrieving the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID)18 v6.8 (https://david.ncifcrf. gov/, October 9, 2018).

Retrieval of COPD driver genes

There has been a variety of known COPD-related genes in Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (GOLD) guideline,3 peer-reviewed literatures,19–23 Online Mendelian Inheritance (OMIM) database24 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/, July 4, 2017), and Genetic Association Database25 (GAD, http://geneticassociationdbnih.gov/). The GOLD guideline illustrated some mainstream mecha nisms of COPD and emphysema, such as protease– antiprotease imbalance, which guided us to further search for specific genes in some canonical reviews. In addition, OMIM and GAD are open access databases, providing a comprehensive and authoritative compendium of genetic alterations associated with disease phenotypes. Based on the keywords of COPD or emphysema, we retrieved the above literatures and databases and identified driver genes of COPD.

Direct protein–protein interaction network of DEGs and known driver genes

The topological and functional analysis of protein interaction network is helpful in the identification of key genes and functional modules that participate in disease onset and progression.16 In network pharmacology, merging the interaction networks of drug predicted targets and driver genes of disease is an effective and original method to identify the concrete genes or pathways by which drug affects the disease.15,16 Enlightened by this analytical method, we tried to analyze the interacted relationship between DEGs and accepted mechanism of COPD in order to identify more credible DEGs participating in emphysema development.

STRING v10.526 (https://www.string-db.org/, July 20, 2017), a web database recording physical and functional protein–protein interaction (PPi) information, was used to predict the interacted relationship between driver genes and DEGs. A variety of active interaction sources in STRING were included into our search strategy, such as text mining, experiment record, database record, coexpression, neighbor-hood, gene fusion, and co-occurrence. The interaction network was further visualized by Cytoscape27 v3.6.1 which is an open access software aimed at annotating and visualizing biological pathways and molecular interaction networks.

Indirect PPi of DEGs and known driver genes

Weighed protein–protein interaction network analysis has been regarded as a novel approach to highlight key functional genes of complex disorders like frontotemporal dementia.14 It indicates that analyzing disease-spectrum genes, also known as first-layer interacting proteins of key genes, is a greatly potential approach to validate previous findings and explore novel disease-related mechanisms.

Thus, we retrieved STRING database v10.5 to obtain the first-layer proteins associated with DEGs products and constructed an indirect PPi of these proteins. The first-layer interacting proteins were roughly classified according to the clustering annotation of Gene Oncology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes28 by the Functional Annotation tool in the DAVID database. Then, the merge tool of Cytoscape software v3.6.127 was applied to merge the indirect PPi with driver genes’ PPi to discover the interconnected and intersected functional modules and target the core genes.

In addition, highly connected nodes with a great number of edges in the network are likely to be significantly functional in the disease context and defined as hub genes.29 The number of each gene node’s edges in the indirect PPi network was ranked to identify hub genes with functional significance in emphysema by Cytoscape software.

Identification of candidate transcription factors

TRANSFAC® Professional database30 is an authoritative and paid database, recording comprehensive information of transcription factor (TF), their regulated genes and binding sites prediction profiles. We performed the TF prediction of core genes by using Gene Radar tool on the GCBI website (Genminix Informatics Ltd., Shanghai, China). Based on all transcripts of each gene (Ensembl database GRCh38 version), the Gene Radar tool could acquire comprehensive TF prediction results from the TRANSFAC Professional database. In addition, Gene Radar tool could screen out high-recommended TFs by integrating the scores from the TRANSFAC database, the existence of single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) loci and methylation modification in TF binding sites. Therefore, we identified the candidate TFs of core genes with high recommendation grade.

Results

Baseline characteristic between severe and mild emphysema groups

As Table 1 shows, all patients were former smokers and presented with severe to very severe airflow limitation according to the GOLD guideline.3 Despite relatively small sample size, a significant difference of many characteristics between two groups was observed, like the ratio of FEV1/FVC and body mass index, proving the credibility of %LAA-950-dependent grouping method.

Table 1.

Comparisons of baseline characteristics suggested the credibility of %LAA-950-dependent grouping method

| Characteristics | Severe emphysema group (n=11) | Mild emphysema group (n=12) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61.6±5.9 | 63.1±10.4 | .0.05 |

| Male/female | 8/3 | 6/6 | .0.05 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.0±3.3 | 27.9±5.3 | 0.0102 |

| Smoking history (pack-years) | 66.5±21.2 | 58.6±29.2 | 0.0013 |

| %LAA-950 | 52.7±2.0 | 7.3±5.3 | <0.0001 |

| FEV1 (%predicted) | 23.0±8.4 | 32.7±13.3 | 0.051 |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 25.5±4.8 | 42.3±14.2 | 0.0012 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; %LAA-950, percents of low attenuation areas <−950 Hounsfield unit on inspiratory CT.

DEGs between two groups and the list of COPD driver genes

We identified 57 DEGs including 15 upregulated genes, 30 downregulated genes, and 12 pseudogenes (unlisted) in severe emphysema group, compared with the mild emphysema group (shown in Table 2). The Gene Oncology annotations of 45 genes were shown in Table S1.

Table 2.

Forty-five DEGs were identified between severe and mild emphysema groups

| Functional category | Gene symbol | Dysregulation | P-value | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional regulation | KANK1 PHF1 PHF6 TADA2A TRIM34 ZFHX3 ZNF322 ZNF451 |

Down Down Up Up Up Down Up Up |

5.58E–05 4.45E–05 2.08E–05 8.32E–05 3.85E–06 4.31E–05 2.88E–06 8.66E–05 |

−1.82 −1.63 2.01 2.42 1.54 −1.54 1.58 2.54 |

| Membrane receptor and signal pathway |

BAG4 BCR FYB1 GNB4 GPR65 NPSR1 NPHP4 P2RY13 RNF213 ZFP106 ZC3HAV1 |

Up Down Up Up Up Down Down Up Up Down Down |

0.000061 6.05E–05 5.24E–06 7.66E–05 7.58E–05 7.72E–05 8.48E–05 3.03E–05 6.32E–05 2.71E–05 8.41E–05 |

1.71 −1.59 2.43 2.49 2.54 −1.73 −1.93 4.2 2 −1.5 −1.43 |

| Metabolism | DPM3 ELOVL3 ETNK2 IMPDH2 |

Down Down Down Down |

7.09E–05 4.72E–05 2.63E–05 7.49E–05 |

−1.44 −1.47 −1.74 −1.5 |

| Cilium | IFT140 TMEM80 |

Down Down |

1.65E–05 5.48E–05 |

−1.93 −1.75 |

| Protein modification | USP33 NUP58 PARP16 |

Up Up Down |

2.29E–05 3.89E–05 6.93E–05 |

2.64 2.96 −1.73 |

| Others | DNAJB14 ZBTB8OS EHBP1 ATP1B2 FAM149A TLN1 SF3A1 FAM168B CYB5D2 KCNJ4 ZCCHC3 MRPS24 swi5 SERPINI1 SVEP1 VPS28 OGFOD3 |

Up Up Down Down Down Down Down Down Down Down Down Down Down Down Down Down Down |

4.21E–05 6.47E–05 9.96E–07 7.85E–06 7.86E–06 2.68E–05 2.46E–05 4.84E–05 3.72E–05 8.54E–05 7.39E–05 4.46E–05 3.21E–05 7.31E–05 5.94E–05 6.99E–05 7.25E–05 |

2.16 1.65 −1.42 −3.09 −3.32 −1.47 −1.49 −1.71 −1.33 −1.77 −1.57 −1.36 −1.34 −1.58 −1.67 −1.52 −1.57 |

Note: DEGs were roughly classified according to the BP and MF terms of Gene Oncology by using the Functional Annotation tool in the DAVID database.

Abbreviations: BP, biological process; DAVID, the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; MF, molecular function.

According to involved pathways, 135 retrieved COPD driver genes were separately placed in extracellular matrix-associated column, oxidative stress column, inflammation column, and others column (shown in Table 3).

Table 3.

Known driver genes of COPD as grouped into four categories

| Synthesis and degradation of ECM (n=37) | Oxidative stress (n=12) | Abnormal inflammation (n=36) | Others (n=50) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| ELN | COL1A1 | GSTP1 | TNF | CCL5 | LTA4H | CLASP1 | VEGFA |

| FBLN4 | COL1A2 | GSTM1 | TNFRSF1A | IL17F | MUC5AC | ADRB2 | GABPA |

| FBLN5 | FBN2 | HMOX1 | TNFRSF1B | IL1RN | MUC5B | GC | MTHFR |

| FBN1 | FBN3 | NOS2 | IL-17A | IFNG | SLC6A4 | DEFB1 | SPAR |

| ATP7A | COL3A1 | NOS3 | IL-18 | TSLP | EGF | CYP21A2 | HSPA1B |

| TGFB1 | COL8A1 | SOD2 | IL1b | CCR2 | EGFR | CFTR | CAT |

| TGFBR3 | COL4A1 | MMAC1 | HDAC2 | IL8RB | FGF10 | APOE | OGG1 |

| LTBP4 | FN4 | SOD3 | IL12 | IL13 | CHRNA3 | AGTR1 | PDE4D |

| SERPINE2 | FN1 | PIK3CA | IL21 | IL11 | CHRNA5 | ADRB3 | TCEAL1 |

| ELANE | DCN | PIK3R1 | IL22 | CCR5 | IREB2 | TF | BCL2 |

| MMP1 | BGN | NFE2L2 | IL-23 | CCR6 | FAM13A | SFTPB | DBP |

| TIMP1 | TGFBR1 | EPHX1 | IL27 | CXCL8 | FTO | SERPINE1 | HCK |

| MMP2 | SMAD3 | IL32 | CXCR1 | BICD1 | SERPINA1 | ||

| MMP3 | SMAD7 | IL-4 | CXCR2 | HHIP | NAT2 | ||

| MMP8 | VCAN | IL-6 | CXCR3 | ACE | LTA | ||

| MMP9 | TNC | IL-10 | TLR9 | KCNIP4 | HSPA1L | ||

| MMP10 | SPP1 | CCL11 | IL8RA | CRHR1 | HSPA1A | ||

| MMP14 | TIMP2 | CLL2 | CCL1 | CYP1A2 | HRAS | ||

| MMP12 | TP53 | SCGB1A1 | |||||

Abbreviation: ECM, extracellular matrix.

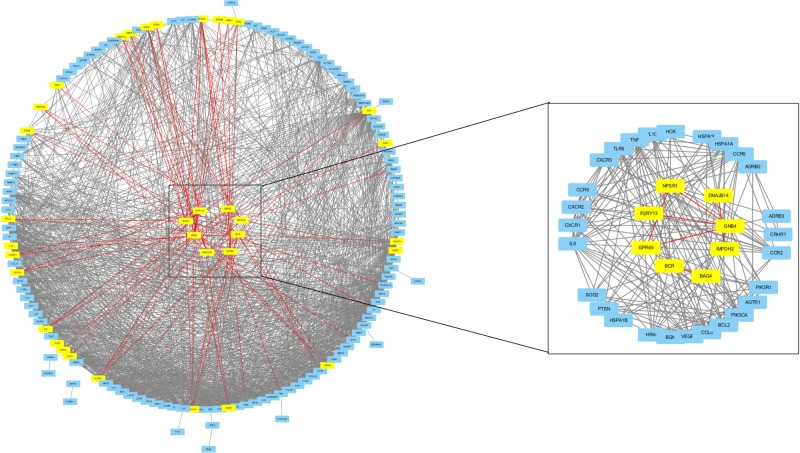

Candidate genes directly interacted with driver genes

A total of 180 genes (45 DEGs +135 driver genes) were recruited to construct the network, 7 were withdrawn for failed identification of gene symbol and 147 were found to have interaction with others. Eight of the 45 DEGs were found to have interaction relationship with driver genes: G-protein coupling receptor 65 (GPR65), Neuropeptide S receptor 1 (NPSR1), purinergic receptor P2RY13, RhoGEF and GTPase activating protein (BCR), G protein subunit β4 (GNB4), BCL2-associated athanogene 4 (BAG4), inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase 2 (IMDPH2), and Hsp40 member 14 (DNAJB14; shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Candidate genes were screened by direct PPi of DEGs and COPD driver genes.

Notes: The left panel shows the 147 genes-constructed interaction network. Eight driver genes-associated DEGs are highlighted at the center of circle and the red lines identify the interaction relationship of the eight highlighted DEGs and the corresponding driver genes. The right panel amplifies the mutual relationship of eight DEGs and their interacted COPD driver genes.

Abbreviations: DEGs, differentially expressed genes; PPi, protein–protein interaction.

A relatively separate interacting set was composed of GPR65, NPSR1, P2RY13, and GNB4. In addition, BCR and BAG4, IMDPH2 and DNAJB14 had separately bilateral relationship. When the cutoff value of the combined interaction score was set at 0.9, we found that GNB4 and P2RY13 mostly interacted with chemokines and chemokine receptors, such as CXCR1, CCR2, CXCR2, IL8, CXCR3, CCR5, CCL5, and CCR6. BAG4 interacted with TNFα and its receptor as well as heat shock protein (HSP) family. In addition, PIK3CA and PIK3R1 may play an important role by interacting with GPR65, GNB4, BCR, NPSR1, and BAG4.

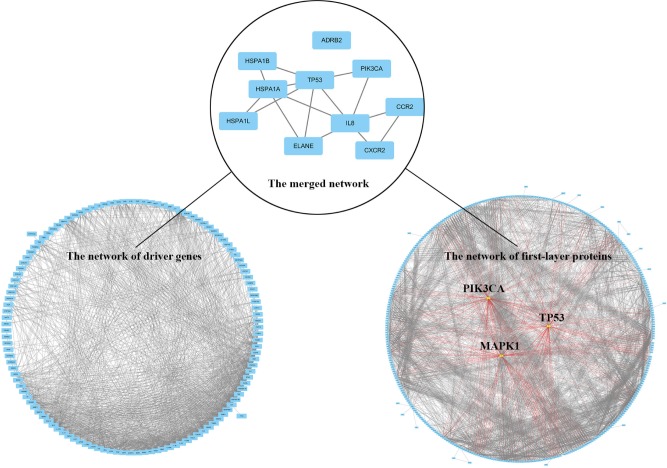

Common key genes and their TFs filtered by merging of indirect PPi and driver PPi

A total of 422 first-layer interacting proteins were attained by retrieving STRING database v10.5 (shown in Table S2). Among them, 375 proteins were recruited to construct the indirect PPi and the remaining proteins were withdrawn due to failed identification or isolation from interaction network. According to the number of each node’s edges in the topological network, 375 proteins in indirect PPi were ranked and the top 20 are shown in Table S3. PIK3CA, TP53, and MAPK1, the top three genes in the rank of topological nodes of indirect PPi, had separately 86, 74, and 72 interacting nodes, which showed their potentially predominant and interconnected roles in the mechanism of emphysema progression.

The merged network illustrated in Figure 2 shows a total of 10 genes that constituted the intersection network of the two networks: TP53, IL8, CCR2, CXCR2, PIK3CA, ELANE, HSPA1A, HSPA1B, HSPA1L, and ADRB2.

Figure 2.

Common key genes are screened by merging of indirect PPi and driver PPi.

Notes: The left panel represents the 125 driver genes-constructed interaction network, and the right panel shows the 375 genes-constructed network of first-layer proteins of DEGs. The top three genes in the rank of topological network node stand out at the center of right circle and the red lines identify their interaction relationship with other first-layer proteins. The upper panel shows the merge network of the lower two PPis, representing the common genes and pathways involved in the two networks.

Abbreviations: DEGs, differentially expressed genes; PPi, protein–protein interaction.

TFs that could bind to promoter region of the above eight genes were retrieved and shown in Table S4. Because ADRB2 was independent from the network and none of the TFs with high recommendation score was retrieved for HSPA1B, they were omitted for presentation. What’s more, SPIB, CPBP, SATB1, ZNF333, HOXA13, KID3, SOX4, and FOXO1A were potentially meaningful TFs, which could regulate no less than half genes of the above nine genes.

Discussion

We identified eight novel candidate genes (GPR65, GNB4, P2RY13, NPSR1, BCR, BAG4, IMPDH2, and TP53) promoting the progression of emphysema by means of network analysis of DEGs and COPD driver genes.

This is the first study that QCT index was applied to classify emphysema for analyzing DEGs, and known COPD driver genes were retrieved to construct interacting networks with DEGs. Our method of direct and indirect network analysis has some merit. For analysis of DEGs, it is a difficult problem to interpret the biological role of the identified single gene in the pathogenic mechanism. Performing external and experimental validation for all DEGs is cumbersome and inefficient. Incorporating driver genes into direct network analysis with DEGs is helpful in quickly highlighting causative DEGs and excluding random DEGs caused by covariates, making the role of identified DEGs more credible. In addition, protein function is regulated not only at transcriptional level but also at posttranscription level which DNA microarray could not detect. A previous study of breast cancer demonstrated that known driver genes, with their expression profiles not changed, were still capable of interconnecting many transcriptionally dysregulated genes in the protein interacting network.31 Therefore, we innovatively used the method of first-layer protein interacting network to further explore the indirect effects of DEGs and seek potential ignored genes. Furthermore, for the polygenic complex disease, a single gene is incapable of comprehensively illustrating the molecular mechanism of phenotypes. By merging the indirect PPi and driver PPi, we could efficiently extract the candidate protein networks involved in a specific disease phenotype. This method,14 of which the efficacy has been confirmed in a study of frontotemporal dementia, could be applied in exploring other complex disorders or extended to other phenotypes of COPD, such as airway remodeling. By comparing difference of the critical protein interactome in different phenotypes, we could unveil the different molecular mechanisms promoting complex pathological processes, which was crucial to promote biomarker and drug discovery.

As a proton-sensing receptor, GPR65 could regulate the immune response of T cells and macrophages and induce the production of MMP3 in the acidic microenvironment.32–34 Asthma, another chronic airway disease with obstructive airflow limitation, was demonstrated to have local acidic microenvironment,35 where eosinophil showed decreased apoptosis and increased viability in a GPR65-depedent manner.36

The SNP of NPSR1 was associated with the decline of FEV1 after adjusting for covariates in normal aging population.37 Moreover, DNA methylation status of NPSR1 in adult severe asthma population and childhood allergic asthma population was distinct from that of control population.38 NPSR1’s expression on peripheral blood eosinophils was positively correlated with asthma’s severity and serum IgE level.39

Asthma and COPD have many common traits in terms of risk factors, inflammatory responses, clinical features, and therapeutic methods.3,40 Furthermore, the role of eosinophils in the pathogenesis and treatment of COPD is gradually recognized.3,41 Therefore, we speculated that the above genes related to asthma were highly likely to be involved in the pathogenesis of COPD and emphysema.

As an extracellular ADP receptor, P2RY13 participated in purinergic signaling pathway, resulting in the apoptosis of pancreatic β-cells42 and differentiation of marrow stem cells into osteoblasts.43 Since the roles of extracellular adenosine ATP and its receptor P2RX in COPD have been confirmed,44,45 ADP, the intermediate in purinergic metabolic pathways, may also have pathogenic effects on COPD.

In addition, common key genes identified by the indirect method matched well with the two-hit hypothesis of COPD,46 especially the part of senescence and senescence-associated secretary phenotype (SASP).47 Senescence is an irreversible cell state, at which a cell is deprived of its replicative capacity with cell cycle arrest.48 The p53 (encoded by TP53)/p21 pathway participated in all types of senescence mechanisms, arresting cell cycle at the G1/S and G2/M check points.49 SASP refers to the alteration of aging cell’s secretome toward more production of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-8 and monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1).49 IL-8 and its receptor CXCR2, with neutrophil chemotactic ability, are just one of the most important chemokine-receptor pairs in COPD pathogenesis, as well as MCP-1 encoded by CCR2.6 Moreover, phosphoinositide 3 kinase (PI3K), the product of PIK3CA, was also known as a pro-senescent kinase by inactivating HDAC-2 which is an antiaging molecule, because knockdown of HDAC-2 could induce cellular senescence by enhancing p53-dependent transcriptional responses.50

Based on these evidence, we hypothesized that TP53 might play a central role in promoting progression of emphysema. Firstly, beside IL-8, CXCR2 and CCR2, elastase, the products of ELANE, and PI3K are also well-recognized COPD driver genes playing an important role in protease– antiprotease imbalance and chronic inflammation of COPD.6 The involvement of these genes supports our results and in return proves the role of TP53.

Secondly, TP53 can induce cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, senescence, DNA repair, or metabolic alterations, in response to oxidative stress and DNA damage.51 Some studies confirmed that TP53 was overexpressed in the emphysematous lung tissue.52 A Genome-Wide Association Study for 365 patients with emphysema proved the association of TP53’s SNP with apoptotic signaling and smoking-related emphysematous changes in smoker’s lungs.53 Furthermore, a RNA-sequencing study of COPD patients’ lung tissues identified the enrichment of p53/hypoxia pathway and the phenomenon of much frequent molecule’s alternative splicing in this pathway.54

Thirdly, the role of TP53 in senescence might reveal its effects in COPD. Many evidences have shown the association between senescence and pathogenesis of COPD. Cellular experiments proved that alveolar epithelial and endothelial cell as well as fibroblast underwent accelerated senescence in emphysematous lung.55,56 Epidemiological surveys indicated that the incidence of COPD and the decline of FEV1 increased with growth of age.3 Moreover, airway and parenchyma of the patients with COPD and healthy senior citizens had similar structural changes.50,57

There are many studies searching for key genes associated with emphysema. In a research on seeking differently expressed miRNAs of emphysema, the miR-638 was identified as an effector molecule and it could regulate accelerated senescence, which was partially consistent with our hypothesis.58 However, we did not reproduce the DEGs of other studies for emphysema. On one hand, it was due to different grouping methods;59 on the other hand, their samples mainly came from patients with moderate COPD (FEV1% was about 60%),60,61 so their results mainly explained the early mechanisms of emphysema progression.

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, the sample size is relatively small,62 which is due to limited numbers of accessible datasets in GEO database. Secondly, the selection of COPD driver genes is potentially biased and incomplete so that some meaningful DEGs may be ignored. Thirdly, PPi prediction has false positives and false negatives. The web tool STRING v10.5 defines PPi by the standard of text mining, experiment record, database record, coexpression, neighborhood, gene fusion, and co-occurrence, which may have a bit of controversy. In addition, interactions proved by experiments in vitro may also have differences compared with those in vivo.

Despite these limitations, our study has put forward some novel candidate genes, and following experiments or larger databases are needed to testify the role of the above candidate genes in the mechanism of emphysema progression.

Conclusion

We have identified several novel candidate genes promoting emphysema, like GPR65, NPSR1, and TP53, which may be helpful in filling in the gap of knowledge in the field of COPD.

Supplementary materials

Table S1.

GO annotation of DEGs between severe and mild emphysema groups

| Functional category | Gene Symbol | GO annotation |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional regulation |

KANK1 PHF1 PHF6 TADA2A TRIM34 ZFHX3 ZNF322 ZNF451 |

Positive regulation of Wnt signaling pathway, negative regulation of actin filament polymerization and so on Involved in regulation of histone H3-K27 methylation and cellular response to DNA damage stimulus Negative regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter, an oncogene A transcriptional activator adaptor; acetylating and destabilizing nucleosomes Involved in interferon signaling pathways Transcription factor activity, RNA polymerase II distal enhancer sequence-specific binding Regulate transcriptional activation in MAPK signaling pathways Negative regulation of transcription initiation from RNA polymerase II promoter, histone H3-K9 acetylation and TGF-β signaling pathway |

| Membrane receptor and signal pathway | BAG4 BCR FYB1 GNB4 GPR65 NPSR1 NPHP4 P2RY13 RNF213 ZFP106 ZC3HAV1 |

Negative regulation of apoptotic process, response to TNFα GTPase activator activity and Rho guanyl-nucleotide exchange factor activity Involved in TCR signaling pathways, the expression of IL-2 and process of NLS-bearing protein importing into nucleus A subunit of heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide-binding proteins involved in cellular response to glucagon stimulus Involved in G-protein coupled receptor signaling pathway, actin cytoskeleton reorganization, and apoptotic process Neuropeptide and vasopressin receptor activity, increased expression in lung for asthma Involved in actin cytoskeleton organization, hippo signaling, and negative regulation of canonical Wnt signaling pathway G-protein coupled purinergic nucleotide receptor and negative regulation of adenylate cyclase activity signaling pathway ATPase activity, ubiquitin-protein transferase activity, and negative regulation of noncanonical Wnt signaling pathway Insulin receptor signaling pathway Defense response to virus |

| Metabolism | DPM3 ELOVL3 ETNK2 IMPDH2 |

GPI anchor biosynthetic process and protein mannosylation Fatty acid elongase activity providing precursors for synthesis of sphingolipids and ceramides A member of choline/ethanolamine kinase family that catalyses phosphatidylethanolamine biosynthetic process Purine ribonucleoside monophosphate biosynthetic process, neutrophil degranulation, and oxidation-reduced process |

| Cilium | IFT140 TMEM80 |

Intraciliary transport involved in cilium assembly Integral component of membrane |

| Protein modification | USP33 NUP58 PARP16 |

Protein deubiquitination and involved in slit-dependent cell migration and beta-2 adrenergic receptor signaling A component of the nuclear pore complex playing a role of nucleocytoplasmic transporter activity NAD+ ADP-ribosyltransferase activity and protein serine/threonine kinase activator activity |

| Others | DNAJB14 ZBTB8OS EHBP1 ATP1B2 FAM149A TLN1 SF3A1 FAM168B CYB5D2 KCNJ4 ZCCHC3 MRPS24 swi5 SERPINI1 SVEP1 VPS28 OGFOD3 |

Hsp70 protein binding and chaperone cofactor-dependent protein refolding tRNA splicing via endonucleolytic cleavage and ligation Endocytosis and its mutation associated with prostate cancer ATP hydrolysis coupled transmembrane transport and cell adhesion Associated with acute mountain sickness Integrin-mediated signaling pathway, cell–cell and cell–substrate junction assembly such as actin A component of the mature U2 snRNP playing a role of pre-mRNA splicing Myelin-associated neurite-outgrowth inhibitor Positive regulation of neuron differentiation A member of the inward rectifier potassium channel family RNA binding A structural constituent of ribosome related to mitochondrial translation DNA repair protein swi5 homolog Serine-type endopeptidase inhibitor activity and association with central and peripheral nervous system development A ligand for integrin α9β1 and involved in cell adhesion Endosomal transport, macroautophagy, negative regulation of protein ubiquitination and viral budding Oxidoreductase activity, acting on paired donors, with incorporation or reduction of molecular oxygen |

Note: Some COPD-associated genes are highlighted in bold.

Abbreviations: DEGs, differentially expressed genes; GO annotation, Gene Oncology annotation.

Table S2.

The list of first-layer interacting proteins associated with DEGs between two groups

| Translational regulation | Signaling pathway | Matrix and cell adhesion | Virus-associated genes | Others | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| RPL12 | TP53 | PIK3CA | CHMP6 | KCNJ2 | RBBP7 | ZNF91 | GPR37L1 |

| RPL13A | PIK3CA | MAPK1 | RAE1 | KCNJ4 | AEBP2 | AP4E1 | NPHP4 |

| RPL18 | MAPK1 | FYN | ZC3HAV1 | FOS | CYB5D2 | NEURL | PIP5K1C |

| RPL18A | GRB2 | CRKL | DDX1 | GART | PARP14 | TEX10 | SEL1L |

| RPL8 | SHC1 | GRB2 | DDX58 | IFT122 | RIPK4 | AP4M1 | TMEM67 |

| RPS15 | PDGFRB | SHC1 | IRF3 | MKS1 | ZCCHC3 | DPAGT1 | ATIC |

| RPS3 | ITGB1 | PXN | IRF7 | P2RY13 | AFP | NEURL1B | EHD2 |

| RPS9 | ITGB3 | PDGFRB | RPL12 | WDR19 | IMPDH1 | APBB1IP | NPLOC4 |

| MRPS10 | ITGB5 | ITGB1 | IRF9 | ACACA | PARP16 | PI15 | PISD |

| MRPS12 | VWF | ZYX | RPL13A | CIDEA | RNF19B | TLX1 | SELV |

| PAIP1 | GNAI1 | ITGB2 | RPL18 | GCC2 | ZFHX3 | ARC | TMEM80 |

| MRPS14 | GNB1 | TLN1 | RPL18A | IFT140 | AGBL3 | NMRAL1 | EHD3 |

| MRPS15 | GNB2 | ITGB3 | RPL8 | MOCS1 | IMPDH2 | TLX3 | GRAP2 |

| MRPS22 | GNB3 | ITGB5 | RPS15 | WDR35 | RNF213 | ARHGEF6 | KIF21A |

| MRPS23 | GNG2 | VASP | RPS3 | ACACB | TADA2A | ITPA | NPSR1 |

| MRPS24 | GNAO1 | VCL | RPS9 | COL14A1 | ZFP106 | NNMT | PLAT |

| MRPS31 | GNB4 | VWF | TMEM48 | GM2A | AGXT2L1 | PIGM | ATP1A1 |

| MRPS33 | GNG10 | ATG7 | IFT172 | DGAT2 | TMEM171 | ELANE | |

| MRPS5 | GNG13 | TNF | MOCS2 | IQCB1 | ARHGEF7 | KNG1 | |

| RPL10L | GNG3 | Substance transport | KPNB1 | P2RY4 | PCYT2 | DR1 | NUDT11 |

| SEPSECS | GNG4 | RAE1 | NUP107 | ACE2 | RPE65 | NOL10 | PLAU |

| CHCHD1 | GNG5 | TMEM48 | NUP188 | CPB1 | TADA3 | PIGV | SERP1NI1 |

| GNG7 | NUP107 | TRIM34 | GMPS | ZNF322 | TMEM218 | TNFRSF1A | |

| JAK2 | NUP188 | NUP205 | IFT52 | AKAP9 | DTX3L | ATP1A2 | |

| Protein modification and folding | GNGT2 | NUP205 | NUP35 | P2RY8 | DMRT1 | JARID2 | ELAVL4 |

| RAE1 | GNA11 | NUP35 | PML | CPS1 | IRF2 | NOL12 | GRM6 |

| TMEM48 | GNAQ | NUP62 | TSG101 | IFT57 | RPGRIP1L | PIK3C2B | PLEKHG7 |

| NUP107 | ADRBK1 | NUP93 | NUP54 | SUPT3H | TAF1 | SASH1 | SF3A1 |

| NUP188 | IL8 | NUPL1 | HERC5 | YEATS2 | ZNF385D | TMEM222 | ATP1A4 |

| NUP205 | CCR2 | SUMO1 | NUP62 | ADRA1 | ALG1 | EED | ELOVL3 |

| NUP35 | ABL1 | SUMO2 | NUP93 | GNA14 | DNAJB14 | GOLT1A | H2AFV |

| TSG101 | P2RY14 | SUMO3 | NUPL1 | IFT80 | MSRB1 | KAT2A | LACE |

| NUP62 | GNA15 | SUMO4 | OAS1 | PARL | PFAS | NOL3 | PLG |

| NUP93 | SYK | RANGAP1 | PPIA | SUZ12 | TAF9 | SCD | SF3A2 |

| NUPL1 | MYC | PAIP1 | OAS2 | YIPF6 | ALG3 | TMEM247 | ATP1B1 |

| VPS37A | PHLPP1 | STAT3 | OAS3 | ADRB2 | DOCK8 | ATG3 | ENAH |

| VPS4A | PHLPP2 | KPNB1 | OASL | CTPS1 | PHF19 | EHBP1 | H2AFZ |

| SUMO1 | GPR65 | NUP54 | VPS28 | IFT81 | TCEB2 | GPCPD1 | PLRG1 |

| SUMO2 | LAT | UBE2I | VPS37A | RBBP4 | ZNF768 | KAT2B | SF3A3 |

| SUMO3 | TSHB | NUTF2 | VPS37B | SVEP1 | DOLK | NPHP1 | TRMT10C |

| SUMO4 | LPAR1 | VPS37C | ZBTB8OS | NBEAL1 | PIP5K1A | ATP1B3 | |

| RANGAP1 | LPAR2 | VPS4A | IFT88 | PHF6 | SDCCAG8 | ENG | |

| PARP1 | OXGR1 | PARP10 | TCTN1 | EHD1 | HERC1 | ||

| ZNF451 | FPR1 | VPS36 | MIB2 | CEP290 | SIRPA | ||

| ALG5 | FPR2 | DNA repair | CEPT1 | OS9 | OGFOD3 | USP33 | |

| DOLPP1 | ADCY3 | SUMO1 | HSPA6 | SLTM | SKAP2 | CAD | |

| DPM1 | CRKL | PARP1 | CERS2 | FCGR1B | UXT | FAM98A | |

| NFATC2IP | CXCR2 | RPS3 | FXYD1 | HSPA2 | CCP110 | HSPA14 | |

| DPM2 | GNAI3 | RAD51 | STAT5A | MICAL1 | FAM98C | MBIP | |

| PIAS3 | ARRB1 | RAD51B | FXYD2 | SNF8 | HSPA1B | OBSCN | |

| DPM3 | ARRB2 | RAD51C | FXYD6 | VHL | MIB1 | PVR | |

| TP53 | LYN | XRCC2 | HUWE1 | CDKL5 | OPHN1 | SKAP1 | |

| FAM125A | PXN | RAD51D | FXYD7 | HSPA4 | SLC20A2 | USP48 | |

| FAM125B | STAT3 | XRCC3 | HSPA5 | MKI67IP | FASN | CCDC101 | |

| GNAI1 | STAT5B | SWI5 | SPATA5 | SPATA2 | HSPA1L | FAM98B | |

| GNAI3 | PARP2 | SH3GL1 | LATS1 | LLPH | B9D2 | ||

| GNB1 | ATM | C1orf177 | SF3B1 | POTEI | EZH2 | ||

| GNB2 | SFPQ | FAM155B | AWAT1 | SF3B4 | HERC6 | ||

| GNB3 | SFR1 | HSD17B12 | ETNK2 | UBA7 | HSPA13 | ||

| GNG2 | CDC5L | PRPF19 | HERC4 | HIST1H1A | MAX | ||

| GNAO1 | USP20 | LCP2 | POTEJ | PTPRF | |||

| PPIA | C22orf28 | POTEE | BCR | FAM149A | |||

| BAG4 | FAM168B | SF3B2 | HMG20A | HPRT1 | |||

| SIL1 | HSPA12B | B4GALNT1 | POU1F1 | LRRK2 | |||

| MESDC2 | PRPF6 | EVL | UBR2 | POTEF | |||

| HSPA8 | USP22 | LIAS | C14orf166 | SF3B3 | |||

| HSPA9 | C2orf49 | HSPA1A | FAM71E1 | TTC21B | |||

Note: The first-layer interacting proteins were roughly classified according to the BP terms of Gene Oncology and KEGG by the Functional Annotation tool in the DAVID database.

Abbreviations: BP, biological process; DAVID, the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

Table S3.

Top 20 topological network nodes in first-layer’s PPi

| Degree | Name | GO annotation |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 86 | PIK3CA | Protein serine/threonine kinase activity and signaling pathway |

| 74 | TP53 | Transcription factor activity |

| 72 | MAPK1 | Protein serine/threonine kinase activity and signaling pathway |

| 68 | HSPA8 | Chaperone and protein folding |

| 64 | ACACA | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase activity |

| 63 | CAD | Aspartate carbamoyltransferase activity |

| 62 | ACACB | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase activity |

| 61 | POTEF | Retina homeostasis |

| 60 | LRRK2 | Protein serine/threonine kinase activity |

| 58 | IL8 | Neutrophil chemotaxis |

| 54 | POTEE | Retina homeostasis |

| 53 | POTEI | Retina homeostasis |

| 53 | POTEJ | Retina homeostasis |

| 53 | PHLPP1 | Protein dephosphorylation and signaling pathway |

| 53 | RIPK4 | Protein serine/threonine kinase activity |

| 53 | PHLPP2 | Protein dephosphorylation |

| 52 | GART | Purine nucleobase biosynthetic process |

| 50 | MYC | Transcription factor activity |

| 48 | GMPS | Purine nucleobase biosynthetic process |

| 47 | OAS2 | Purine nucleobase biosynthetic process |

Abbreviations: GO, Gene Oncology; PPi, protein–protein interaction.

Table S4.

Transcript factors of common key genes screened by indirect PPi

| TP53 | IL-8 | PIK3CA | ELANE | CCR2 | CXCR2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| AHR | MEIS1 | ALX3 | MYB | AP2GAMMA | SPIB | ALX3 | TEF1 | AHRHIF | PMX1 |

| AML1 | MTF1 | AP1 | NF1C | BCL6 | PARP | AML1 | THAP1 | AML1 | POU4F3 |

| AP1 | MYB | BCL6 | NFE2 | CBF | NR2C2 | AP1 | TORC2 | AP2REP | PRRX2 |

| AP2GAMMA | MYOGENIN | CDX1 | NKX61 | CDX | AP2GAMMA | USF | BARHL1 | RORA1 | |

| BEN | MZF1 | CDX2 | NMYC | CDX2 | BRCA | USF2 | BARHL2 | RPC155 | |

| BRCA | NEUROD | CDXA | NURR1 | CDXA | HSPA1L | CEBP | ZBTB2 | BEN | RXRA |

| CACD | NFAT1 | CETS1 | PARP | CHCH | KID3 | CEBPB | ZEB1 | BRCA | SATB1 |

| CDX1 | NFAT3 | CFOS | PEA3 | CPBP | EGR1 | CEBPD | ZNF333 | BRN1 | SMAD2 |

| CDX2 | NFAT4 | CMYB | PLZFB | EGR3 | GABPA | CMYB | CDX1 | SOX10 | |

| CEBP | NKX25 | CPBP | PMX1 | ETF | CPBP | CEBPA | SOX17 | ||

| CEBPA | NKX2B | CREB | PRRX2 | ETS1 | CPEB1 | CEBPB | SOX18 | ||

| CETS1 | NMYC | ELF1 | RAX | FOS | HSPA1A | DLX3 | CHCH | SOX4 | |

| CHCH | NR1B2 | ELK1 | RORBETA | FOSL1 | CHCH | E2A | CP2 | SOX5 | |

| CJUN | OSX | EMX1 | SATB1 | FOXM1 | CPBP | E2F1 | CPBP | SPI1 | |

| CMAF | PARP | ETS2 | SF1 | FOXO1A | E2F3 | EGR3 | DMBX1 | SPIB | |

| CMYB | PAX4 | ETV7 | SOX17 | GABPA | EGR1 | EMX1 | E2A | SREBP2 | |

| CPBP | PEA3 | EVX1 | SOX4 | GATA3 | KLF7 | EVX1 | E2F1 | SRY | |

| CPEB1 | PITX2 | EVX2 | SPI1 | GKLF | KLF8 | EVX2 | E2F3 | STAT3 | |

| DR4 | PLAGL2 | FLI1 | SPIB | HFH8 | LKLF | FOXK1 | ELF1 | TAL1 | |

| E2F3 | PRRX2 | FOSL2 | SREBP1 | HNF3A | MOVOB | FOXP3 | ETS | TCF1 | |

| EBF1 | PU1 | FOXC1 | TAF1 | HOXA13 | PLAGL2 | GATA1 | ETV7 | TCF11 | |

| EGR1 | PUR1 | FOXD2 | TATA | ISL2 | SP2 | GKLF | FOXC1 | TCFE2A | |

| EHF | RELA | FOXD3 | TBP | KID3 | SP3 | GR | FOXO1A | TFAP2C | |

| ELF1 | RORBETA | FOXG1 | TEF1 | KLF | SP6 | HMGIY | GATA2 | TORC2 | |

| ELF5 | SALL2 | FOXI1 | TTF1 | LKLF | VMYB | HOXA10 | GKLF | USF2 | |

| ELK1 | SATB1 | FOXK1 | ZNF333 | MAZR | ZBTB2 | HOXA13 | GMEB2 | VDRRXRALPHA | |

| ETS2 | SMAD | FOXL1 | MITF | HOXA2 | GR | ZBTB2 | |||

| ETV7 | SMAD2 | FOXM1 | NFAT1 | HOXD3 | HOXA13 | ZFP770 | |||

| FLI1 | SMAD5 | FOX01 | NFAT4 | HSF2 | HSF4 | ZNF333 | |||

| FOXA1 | SOX10 | FOXO1A | NFE4 | IK | IK | ZNF536 | |||

| FOXJ3 | SOX11 | FOXO3 | NR2E1 | IK2 | ING4 | ||||

| FOXL1 | SOX17 | FOXO4 | PLZFB | KID3 | IPF1 | ||||

| FOXM1 | SOX18 | FOXO6 | PMX1 | KLF | IRF7 | ||||

| FOXO1 | SOX30 | FOXP3 | RXRA | LHX2 | ISL2 | ||||

| FOXO1A | SOX4 | FRA1 | SALL2 | LKLF | IKD3 | ||||

| FOXO3A | SOX9 | FXR | SATB1 | MAX | LBP1 | ||||

| FOXP3 | SPI1 | GATA1 | SMAD5 | MEOX2 | LMX1 | ||||

| FRA1 | SPIB | GATA3 | SOX4 | MYB | LPOLYA | ||||

| GABPA | SREBP1 | GATA4 | SOX5 | MYCMAX | MEF2C | ||||

| GATA1 | SRY | GATA5 | SPIB | NF1A | MOVOB | ||||

| GATA2 | STAT | GSX1 | SREBP2 | NFATC2 | MTF1 | ||||

| GATA3 | STAT3 | GSX2 | SRY | NMYC | MYC | ||||

| GATA4 | TCF4 | HMGIY | TCF | 2-Oct | MYOD | ||||

| GKLF | TEL2 | HMX3 | TFE | PARP | MYOGENIN | ||||

| HDAC1 | THAP1 | HOXA1 | WT1 | PAX5 | MZF1 | ||||

| HMGIY | TORC2 | HOXA13 | ZAC | PEBP2B | NANOG | ||||

| HNF3A | USF | HOXA2 | ZFP641 | PMX1 | NEUROD | ||||

| HNF3G | USF2 | HOXB13 | ZNF333 | PR | NKX32 | ||||

| HOXA13 | VMYB | HOXB5 | ZNF641 | PRRX2 | NMYC | ||||

| HSF1 | WT1 | HOXC13 | RELA | NR1B2 | |||||

| HSF4 | YY1 | HOXD13 | SALL2 | NR2C2 | |||||

| IK | ZBTB44 | JUNB | SATB1 | 1-Oct | |||||

| ING4 | ZEB1 | KID3 | SMAD2 | OG2 | |||||

| IRF1 | ZFP532 | LBX2 | SOX10 | OTX | |||||

| IRF7 | ZFP536 | LMX1A | SOX17 | P300 | |||||

| KID3 | ZIC1 | LRH1 | SOX18 | PARP | |||||

| KLF | ZIC3 | MEF2D | SPIB | PAX5 | |||||

| KLF17 | ZNF333 | MEOX2 | SREBP2 | PEA3 | |||||

| LHX2 | ZNF367 | MIXL1 | TCF1 | PEBP2B | |||||

| LKLF | ZNF515 | MSX2 | TCF11 | PIT1 | |||||

Note: Key genes are highlighted in bold.

Abbreviation: PPi, protein–protein interaction.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Xiao Shi who critically reviewed the article for English writing. This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant Nos 2017YFC1309303 and 2017YFC1309300) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant Nos 81670030 and 81470231).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Global Health Estimates 2016 . Deaths by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000–2016. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hogg JC, Timens W. The pathology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:435–459. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD. 2017. [Accessed April 4, 2017]. revised. Available from: https://goldcopd.org/gold-2017-global-strategy-diagnosis-management-prevention-copd/

- 4.Subramanian DR, Gupta S, Burggraf D, et al. Emphysema- and airway-dominant COPD phenotypes defined by standardised quantitative computed tomography. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(1):92–103. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01878-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Frankenberger M, Heimbeck I, et al. The EvA study: aims and strategy. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(4):823–829. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00142811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung KF, Adcock IM. Multifaceted mechanisms in COPD: inflammation, immunity, and tissue repair and destruction. Eur Respir J. 2008;31(6):1334–1356. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00018908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vermylen JH, Kalhan R. Revealing the complexity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Transl Res. 2013;162(4):203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gharib SA, Manicone AM, Parks WC. Matrix metalloproteinases in emphysema. Matrix Biol. 2018;73:34–51. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2018.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuder RM, Petrache I. Pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(8):2749–2755. doi: 10.1172/JCI60324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch DA, Al-Qaisi MA. Quantitative computed tomography in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Thorac Imaging. 2013;28(5):284–290. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e318298733c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nambu A, Zach J, Schroeder J, et al. Quantitative computed tomography measurements to evaluate airway disease in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: relationship to physiological measurements, clinical index and visual assessment of airway disease. Eur J Radiol. 2016;85(11):2144–2151. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castaldi PJ, San José Estépar R, Mendoza CS, et al. Distinct quantitative computed tomography emphysema patterns are associated with physiology and function in smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(9):1083–1090. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201305-0873OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrow JD, Zhou X, Lao T, et al. Functional interactors of three genome-wide association study genes are differentially expressed in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease lung tissue. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44232. doi: 10.1038/srep44232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrari R, Lovering RC, Hardy J, Lewis PA, Manzoni C. Weighted protein interaction network analysis of frontotemporal dementia. J Proteome Res. 2017;16(2):999–1013. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J, Zhao P, Li Y, Tian Y, Wang Y. Systems pharmacology-based dissection of mechanisms of Chinese medicinal formula Bufei Yishen as an effective treatment for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15290. doi: 10.1038/srep15290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zanzoni A, Soler-López M, Aloy P. A network medicine approach to human disease. FEBS Lett. 2009;583(11):1759–1765. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huntley RP, Sawford T, Mutowo-Meullenet P, et al. The GOA database: gene Ontology annotation updates for 2015. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D1057–D1063. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(1):44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marciniak SJ, Lomas DA. Genetic susceptibility. Clin Chest Med. 2014;35(1):29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnes PJ. The cytokine network in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41(6):631–638. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0220TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mcguinness AJ, Sapey E. Oxidative stress in COPD: sources, markers, and potential mechanisms. J Clin Med. 2017;6(2):E21. doi: 10.3390/jcm6020021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brusselle GG, Joos GF, Bracke KR. New insights into the immunology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2011;378(9795):1015–1026. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60988-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burgstaller G, Oehrle B, Gerckens M, et al. The instructive extracellular matrix of the lung: basic composition and alterations in chronic lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(1):1601805. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01805-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mckusick VA. Mendelian inheritance in man and its online version, OMIM. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80(4):588–604. doi: 10.1086/514346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becker KG, Barnes KC, Bright TJ, Wang SA. The genetic association database. Nat Genet. 2004;36(5):431–432. doi: 10.1038/ng0504-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szklarczyk D, Morris JH, Cook H, et al. The STRING database in 2017: quality-controlled protein-protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D362–D368. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13(11):2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y, Morishima K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D353–D361. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puig-Butille JA, Gimenez-Xavier P, Visconti A, et al. Genomic expression differences between cutaneous cells from red hair color individuals and black hair color individuals based on bioinformatic analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(7):11589–11599. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matys V, Fricke E, Geffers R, et al. TRANSFAC: transcriptional regulation, from patterns to profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(1):374–378. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chuang HY, Lee E, Liu YT, Lee D, Ideker T. Network-based classification of breast cancer metastasis. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:140. doi: 10.1038/msb4100180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Onozawa Y, Fujita Y, Kuwabara H, et al. Activation of T cell death-associated gene 8 regulates the cytokine production of T cells and macrophages in vitro. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;683(1–3):325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radu CG, Nijagal A, McLaughlin J, Wang L, Witte ON. Differential proton sensitivity of related G protein-coupled receptors T cell death-associated gene 8 and G2A expressed in immune cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(5):1632–1637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409415102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu H, Chen X, Huang J, et al. Identification of GPR65, a novel regulator of matrix metalloproteinases using high through-put screening. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;436(1):96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunt JF, Fang K, Malik R, et al. Endogenous airway acidification. Implications for asthma pathophysiology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(3 Pt 1):694–699. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.3.9911005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kottyan LC, Collier AR, Cao KH, et al. Eosinophil viability is increased by acidic pH in a cAMP- and GPR65-dependent manner. Blood. 2009;114(13):2774–2782. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-220681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poon AH, Houseman EA, Ryan L, et al. Variants of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease genes and lung function decline in aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(7):907–913. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reinius LE, Gref A, Sääf A, et al. DNA methylation in the Neuropeptide S Receptor 1 (NPSR1) promoter in relation to asthma and environmental factors. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53877. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ilmarinen P, James A, Moilanen E, et al. Enhanced expression of neuropeptide S (NPS) receptor in eosinophils from severe asthmatics and subjects with total IgE above 100 IU/ml. Peptides. 2014;51:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2013.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silva GE, Sherrill DL, Guerra S, Barbee RA. Asthma as a risk factor for COPD in a longitudinal study. Chest. 2004;126(1):59–65. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vedel-Krogh S, Nielsen SF, Lange P, Vestbo J, Nordestgaard BG. Blood eosinophils and exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Copenhagen General Population Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(9):965–974. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201509-1869OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tan C, Salehi A, Svensson S, Olde B, Erlinge D. ADP receptor P2Y(13) induce apoptosis in pancreatic beta-cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67(3):445–453. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0191-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Biver G, Wang N, Gartland A, et al. Role of the P2Y13 receptor in the differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells into osteoblasts and adipocytes. Stem Cells. 2013;31(12):2747–2758. doi: 10.1002/stem.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Polosa R. Adenosine-receptor subtypes: their relevance to adenosine-mediated responses in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2002;20(2):488–496. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.01132002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pelleg A, Schulman ES, Barnes PJ. Extracellular adenosine 5′-triphosphate in obstructive airway diseases. Chest. 2016;150(4):908–915. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aoshiba K, Tsuji T, Yamaguchi K, Itoh M, Nakamura H. The danger signal plus DNA damage two-hit hypothesis for chronic inflammation in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2013;42(6):1689–1695. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00102912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar M, Seeger W, Voswinckel R. Senescence-associated secretory phenotype and its possible role in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014;51(3):323–333. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0382PS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Campisi J, D’Adda di Fagagna F. Cellular senescence: when bad things happen to good cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(9):729–740. doi: 10.1038/nrm2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abbadie C, Pluquet O, Pourtier A. Epithelial cell senescence: an adaptive response to pre-carcinogenic stresses? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74(24):4471–4509. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2587-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ito K, Barnes PJ. COPD as a disease of accelerated lung aging. Chest. 2009;135(1):173–180. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vousden KH, Prives C. Blinded by the light: the growing complexity of p53. Cell. 2009;137(3):413–431. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morissette MC, Vachon-Beaudoin G, Parent J, Chakir J, Milot J. Increased p53 level, Bax/Bcl-x(L) ratio, and TRAIL receptor expression in human emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(3):240–247. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200710-1486OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mizuno S, Ishizaki T, Kadowaki M, et al. p53 Signaling pathway polymorphisms associated with emphysematous changes in patients with COPD. Chest. 2017;152(1):58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kusko RL, Brothers JF, Tedrow J, et al. Integrated genomics reveals convergent transcriptomic networks underlying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(8):948–960. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201510-2026OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsuji T, Aoshiba K, Nagai A. Alveolar cell senescence in patients with pulmonary emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(8):886–893. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1374OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dagouassat M, Gagliolo JM, Chrusciel S, et al. The cyclooxygenase-2-prostaglandin E2 pathway maintains senescence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease fibroblasts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(7):703–714. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201208-1361OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mercado N, Ito K, Barnes PJ. Accelerated ageing of the lung in COPD: new concepts. Thorax. 2015;70(5):482–489. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Christenson SA, Brandsma CA, Campbell JD, et al. miR-638 regulates gene expression networks associated with emphysematous lung destruction. Genome Med. 2013;5(12):114. doi: 10.1186/gm519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spira A, Beane J, Pinto-Plata V, et al. Gene expression profiling of human lung tissue from smokers with severe emphysema. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31(6):601–610. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0273OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Faner R, Cruz T, Casserras T, et al. Network analysis of lung transcriptomics reveals a distinct B-cell signature in emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(11):1242–1253. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201507-1311OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Francis SM, Larsen JE, Pavey SJ, et al. Expression profiling identifies genes involved in emphysema severity. Respir Res. 2009;10:81. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-10-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hart SN, Therneau TM, Zhang Y, Poland GA, Kocher JP. Calculating sample size estimates for RNA sequencing data. J Comput Biol. 2013;20(12):970–978. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

GO annotation of DEGs between severe and mild emphysema groups

| Functional category | Gene Symbol | GO annotation |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional regulation |

KANK1 PHF1 PHF6 TADA2A TRIM34 ZFHX3 ZNF322 ZNF451 |

Positive regulation of Wnt signaling pathway, negative regulation of actin filament polymerization and so on Involved in regulation of histone H3-K27 methylation and cellular response to DNA damage stimulus Negative regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter, an oncogene A transcriptional activator adaptor; acetylating and destabilizing nucleosomes Involved in interferon signaling pathways Transcription factor activity, RNA polymerase II distal enhancer sequence-specific binding Regulate transcriptional activation in MAPK signaling pathways Negative regulation of transcription initiation from RNA polymerase II promoter, histone H3-K9 acetylation and TGF-β signaling pathway |

| Membrane receptor and signal pathway | BAG4 BCR FYB1 GNB4 GPR65 NPSR1 NPHP4 P2RY13 RNF213 ZFP106 ZC3HAV1 |

Negative regulation of apoptotic process, response to TNFα GTPase activator activity and Rho guanyl-nucleotide exchange factor activity Involved in TCR signaling pathways, the expression of IL-2 and process of NLS-bearing protein importing into nucleus A subunit of heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide-binding proteins involved in cellular response to glucagon stimulus Involved in G-protein coupled receptor signaling pathway, actin cytoskeleton reorganization, and apoptotic process Neuropeptide and vasopressin receptor activity, increased expression in lung for asthma Involved in actin cytoskeleton organization, hippo signaling, and negative regulation of canonical Wnt signaling pathway G-protein coupled purinergic nucleotide receptor and negative regulation of adenylate cyclase activity signaling pathway ATPase activity, ubiquitin-protein transferase activity, and negative regulation of noncanonical Wnt signaling pathway Insulin receptor signaling pathway Defense response to virus |

| Metabolism | DPM3 ELOVL3 ETNK2 IMPDH2 |

GPI anchor biosynthetic process and protein mannosylation Fatty acid elongase activity providing precursors for synthesis of sphingolipids and ceramides A member of choline/ethanolamine kinase family that catalyses phosphatidylethanolamine biosynthetic process Purine ribonucleoside monophosphate biosynthetic process, neutrophil degranulation, and oxidation-reduced process |

| Cilium | IFT140 TMEM80 |

Intraciliary transport involved in cilium assembly Integral component of membrane |

| Protein modification | USP33 NUP58 PARP16 |

Protein deubiquitination and involved in slit-dependent cell migration and beta-2 adrenergic receptor signaling A component of the nuclear pore complex playing a role of nucleocytoplasmic transporter activity NAD+ ADP-ribosyltransferase activity and protein serine/threonine kinase activator activity |

| Others | DNAJB14 ZBTB8OS EHBP1 ATP1B2 FAM149A TLN1 SF3A1 FAM168B CYB5D2 KCNJ4 ZCCHC3 MRPS24 swi5 SERPINI1 SVEP1 VPS28 OGFOD3 |

Hsp70 protein binding and chaperone cofactor-dependent protein refolding tRNA splicing via endonucleolytic cleavage and ligation Endocytosis and its mutation associated with prostate cancer ATP hydrolysis coupled transmembrane transport and cell adhesion Associated with acute mountain sickness Integrin-mediated signaling pathway, cell–cell and cell–substrate junction assembly such as actin A component of the mature U2 snRNP playing a role of pre-mRNA splicing Myelin-associated neurite-outgrowth inhibitor Positive regulation of neuron differentiation A member of the inward rectifier potassium channel family RNA binding A structural constituent of ribosome related to mitochondrial translation DNA repair protein swi5 homolog Serine-type endopeptidase inhibitor activity and association with central and peripheral nervous system development A ligand for integrin α9β1 and involved in cell adhesion Endosomal transport, macroautophagy, negative regulation of protein ubiquitination and viral budding Oxidoreductase activity, acting on paired donors, with incorporation or reduction of molecular oxygen |

Note: Some COPD-associated genes are highlighted in bold.

Abbreviations: DEGs, differentially expressed genes; GO annotation, Gene Oncology annotation.

Table S2.

The list of first-layer interacting proteins associated with DEGs between two groups

| Translational regulation | Signaling pathway | Matrix and cell adhesion | Virus-associated genes | Others | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| RPL12 | TP53 | PIK3CA | CHMP6 | KCNJ2 | RBBP7 | ZNF91 | GPR37L1 |

| RPL13A | PIK3CA | MAPK1 | RAE1 | KCNJ4 | AEBP2 | AP4E1 | NPHP4 |

| RPL18 | MAPK1 | FYN | ZC3HAV1 | FOS | CYB5D2 | NEURL | PIP5K1C |

| RPL18A | GRB2 | CRKL | DDX1 | GART | PARP14 | TEX10 | SEL1L |

| RPL8 | SHC1 | GRB2 | DDX58 | IFT122 | RIPK4 | AP4M1 | TMEM67 |

| RPS15 | PDGFRB | SHC1 | IRF3 | MKS1 | ZCCHC3 | DPAGT1 | ATIC |

| RPS3 | ITGB1 | PXN | IRF7 | P2RY13 | AFP | NEURL1B | EHD2 |

| RPS9 | ITGB3 | PDGFRB | RPL12 | WDR19 | IMPDH1 | APBB1IP | NPLOC4 |

| MRPS10 | ITGB5 | ITGB1 | IRF9 | ACACA | PARP16 | PI15 | PISD |

| MRPS12 | VWF | ZYX | RPL13A | CIDEA | RNF19B | TLX1 | SELV |

| PAIP1 | GNAI1 | ITGB2 | RPL18 | GCC2 | ZFHX3 | ARC | TMEM80 |

| MRPS14 | GNB1 | TLN1 | RPL18A | IFT140 | AGBL3 | NMRAL1 | EHD3 |

| MRPS15 | GNB2 | ITGB3 | RPL8 | MOCS1 | IMPDH2 | TLX3 | GRAP2 |

| MRPS22 | GNB3 | ITGB5 | RPS15 | WDR35 | RNF213 | ARHGEF6 | KIF21A |

| MRPS23 | GNG2 | VASP | RPS3 | ACACB | TADA2A | ITPA | NPSR1 |

| MRPS24 | GNAO1 | VCL | RPS9 | COL14A1 | ZFP106 | NNMT | PLAT |

| MRPS31 | GNB4 | VWF | TMEM48 | GM2A | AGXT2L1 | PIGM | ATP1A1 |

| MRPS33 | GNG10 | ATG7 | IFT172 | DGAT2 | TMEM171 | ELANE | |

| MRPS5 | GNG13 | TNF | MOCS2 | IQCB1 | ARHGEF7 | KNG1 | |

| RPL10L | GNG3 | Substance transport | KPNB1 | P2RY4 | PCYT2 | DR1 | NUDT11 |

| SEPSECS | GNG4 | RAE1 | NUP107 | ACE2 | RPE65 | NOL10 | PLAU |

| CHCHD1 | GNG5 | TMEM48 | NUP188 | CPB1 | TADA3 | PIGV | SERP1NI1 |

| GNG7 | NUP107 | TRIM34 | GMPS | ZNF322 | TMEM218 | TNFRSF1A | |

| JAK2 | NUP188 | NUP205 | IFT52 | AKAP9 | DTX3L | ATP1A2 | |

| Protein modification and folding | GNGT2 | NUP205 | NUP35 | P2RY8 | DMRT1 | JARID2 | ELAVL4 |

| RAE1 | GNA11 | NUP35 | PML | CPS1 | IRF2 | NOL12 | GRM6 |

| TMEM48 | GNAQ | NUP62 | TSG101 | IFT57 | RPGRIP1L | PIK3C2B | PLEKHG7 |

| NUP107 | ADRBK1 | NUP93 | NUP54 | SUPT3H | TAF1 | SASH1 | SF3A1 |

| NUP188 | IL8 | NUPL1 | HERC5 | YEATS2 | ZNF385D | TMEM222 | ATP1A4 |

| NUP205 | CCR2 | SUMO1 | NUP62 | ADRA1 | ALG1 | EED | ELOVL3 |

| NUP35 | ABL1 | SUMO2 | NUP93 | GNA14 | DNAJB14 | GOLT1A | H2AFV |

| TSG101 | P2RY14 | SUMO3 | NUPL1 | IFT80 | MSRB1 | KAT2A | LACE |

| NUP62 | GNA15 | SUMO4 | OAS1 | PARL | PFAS | NOL3 | PLG |

| NUP93 | SYK | RANGAP1 | PPIA | SUZ12 | TAF9 | SCD | SF3A2 |

| NUPL1 | MYC | PAIP1 | OAS2 | YIPF6 | ALG3 | TMEM247 | ATP1B1 |

| VPS37A | PHLPP1 | STAT3 | OAS3 | ADRB2 | DOCK8 | ATG3 | ENAH |

| VPS4A | PHLPP2 | KPNB1 | OASL | CTPS1 | PHF19 | EHBP1 | H2AFZ |

| SUMO1 | GPR65 | NUP54 | VPS28 | IFT81 | TCEB2 | GPCPD1 | PLRG1 |

| SUMO2 | LAT | UBE2I | VPS37A | RBBP4 | ZNF768 | KAT2B | SF3A3 |

| SUMO3 | TSHB | NUTF2 | VPS37B | SVEP1 | DOLK | NPHP1 | TRMT10C |

| SUMO4 | LPAR1 | VPS37C | ZBTB8OS | NBEAL1 | PIP5K1A | ATP1B3 | |

| RANGAP1 | LPAR2 | VPS4A | IFT88 | PHF6 | SDCCAG8 | ENG | |

| PARP1 | OXGR1 | PARP10 | TCTN1 | EHD1 | HERC1 | ||

| ZNF451 | FPR1 | VPS36 | MIB2 | CEP290 | SIRPA | ||

| ALG5 | FPR2 | DNA repair | CEPT1 | OS9 | OGFOD3 | USP33 | |

| DOLPP1 | ADCY3 | SUMO1 | HSPA6 | SLTM | SKAP2 | CAD | |

| DPM1 | CRKL | PARP1 | CERS2 | FCGR1B | UXT | FAM98A | |

| NFATC2IP | CXCR2 | RPS3 | FXYD1 | HSPA2 | CCP110 | HSPA14 | |

| DPM2 | GNAI3 | RAD51 | STAT5A | MICAL1 | FAM98C | MBIP | |

| PIAS3 | ARRB1 | RAD51B | FXYD2 | SNF8 | HSPA1B | OBSCN | |

| DPM3 | ARRB2 | RAD51C | FXYD6 | VHL | MIB1 | PVR | |

| TP53 | LYN | XRCC2 | HUWE1 | CDKL5 | OPHN1 | SKAP1 | |

| FAM125A | PXN | RAD51D | FXYD7 | HSPA4 | SLC20A2 | USP48 | |

| FAM125B | STAT3 | XRCC3 | HSPA5 | MKI67IP | FASN | CCDC101 | |

| GNAI1 | STAT5B | SWI5 | SPATA5 | SPATA2 | HSPA1L | FAM98B | |

| GNAI3 | PARP2 | SH3GL1 | LATS1 | LLPH | B9D2 | ||

| GNB1 | ATM | C1orf177 | SF3B1 | POTEI | EZH2 | ||

| GNB2 | SFPQ | FAM155B | AWAT1 | SF3B4 | HERC6 | ||

| GNB3 | SFR1 | HSD17B12 | ETNK2 | UBA7 | HSPA13 | ||

| GNG2 | CDC5L | PRPF19 | HERC4 | HIST1H1A | MAX | ||

| GNAO1 | USP20 | LCP2 | POTEJ | PTPRF | |||

| PPIA | C22orf28 | POTEE | BCR | FAM149A | |||

| BAG4 | FAM168B | SF3B2 | HMG20A | HPRT1 | |||

| SIL1 | HSPA12B | B4GALNT1 | POU1F1 | LRRK2 | |||

| MESDC2 | PRPF6 | EVL | UBR2 | POTEF | |||

| HSPA8 | USP22 | LIAS | C14orf166 | SF3B3 | |||

| HSPA9 | C2orf49 | HSPA1A | FAM71E1 | TTC21B | |||

Note: The first-layer interacting proteins were roughly classified according to the BP terms of Gene Oncology and KEGG by the Functional Annotation tool in the DAVID database.

Abbreviations: BP, biological process; DAVID, the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

Table S3.

Top 20 topological network nodes in first-layer’s PPi

| Degree | Name | GO annotation |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 86 | PIK3CA | Protein serine/threonine kinase activity and signaling pathway |

| 74 | TP53 | Transcription factor activity |

| 72 | MAPK1 | Protein serine/threonine kinase activity and signaling pathway |

| 68 | HSPA8 | Chaperone and protein folding |

| 64 | ACACA | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase activity |

| 63 | CAD | Aspartate carbamoyltransferase activity |

| 62 | ACACB | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase activity |

| 61 | POTEF | Retina homeostasis |

| 60 | LRRK2 | Protein serine/threonine kinase activity |

| 58 | IL8 | Neutrophil chemotaxis |

| 54 | POTEE | Retina homeostasis |

| 53 | POTEI | Retina homeostasis |

| 53 | POTEJ | Retina homeostasis |

| 53 | PHLPP1 | Protein dephosphorylation and signaling pathway |

| 53 | RIPK4 | Protein serine/threonine kinase activity |

| 53 | PHLPP2 | Protein dephosphorylation |

| 52 | GART | Purine nucleobase biosynthetic process |

| 50 | MYC | Transcription factor activity |

| 48 | GMPS | Purine nucleobase biosynthetic process |

| 47 | OAS2 | Purine nucleobase biosynthetic process |

Abbreviations: GO, Gene Oncology; PPi, protein–protein interaction.

Table S4.

Transcript factors of common key genes screened by indirect PPi

| TP53 | IL-8 | PIK3CA | ELANE | CCR2 | CXCR2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| AHR | MEIS1 | ALX3 | MYB | AP2GAMMA | SPIB | ALX3 | TEF1 | AHRHIF | PMX1 |

| AML1 | MTF1 | AP1 | NF1C | BCL6 | PARP | AML1 | THAP1 | AML1 | POU4F3 |

| AP1 | MYB | BCL6 | NFE2 | CBF | NR2C2 | AP1 | TORC2 | AP2REP | PRRX2 |

| AP2GAMMA | MYOGENIN | CDX1 | NKX61 | CDX | AP2GAMMA | USF | BARHL1 | RORA1 | |

| BEN | MZF1 | CDX2 | NMYC | CDX2 | BRCA | USF2 | BARHL2 | RPC155 | |

| BRCA | NEUROD | CDXA | NURR1 | CDXA | HSPA1L | CEBP | ZBTB2 | BEN | RXRA |

| CACD | NFAT1 | CETS1 | PARP | CHCH | KID3 | CEBPB | ZEB1 | BRCA | SATB1 |

| CDX1 | NFAT3 | CFOS | PEA3 | CPBP | EGR1 | CEBPD | ZNF333 | BRN1 | SMAD2 |

| CDX2 | NFAT4 | CMYB | PLZFB | EGR3 | GABPA | CMYB | CDX1 | SOX10 | |

| CEBP | NKX25 | CPBP | PMX1 | ETF | CPBP | CEBPA | SOX17 | ||

| CEBPA | NKX2B | CREB | PRRX2 | ETS1 | CPEB1 | CEBPB | SOX18 | ||

| CETS1 | NMYC | ELF1 | RAX | FOS | HSPA1A | DLX3 | CHCH | SOX4 | |

| CHCH | NR1B2 | ELK1 | RORBETA | FOSL1 | CHCH | E2A | CP2 | SOX5 | |

| CJUN | OSX | EMX1 | SATB1 | FOXM1 | CPBP | E2F1 | CPBP | SPI1 | |

| CMAF | PARP | ETS2 | SF1 | FOXO1A | E2F3 | EGR3 | DMBX1 | SPIB | |

| CMYB | PAX4 | ETV7 | SOX17 | GABPA | EGR1 | EMX1 | E2A | SREBP2 | |

| CPBP | PEA3 | EVX1 | SOX4 | GATA3 | KLF7 | EVX1 | E2F1 | SRY | |

| CPEB1 | PITX2 | EVX2 | SPI1 | GKLF | KLF8 | EVX2 | E2F3 | STAT3 | |

| DR4 | PLAGL2 | FLI1 | SPIB | HFH8 | LKLF | FOXK1 | ELF1 | TAL1 | |

| E2F3 | PRRX2 | FOSL2 | SREBP1 | HNF3A | MOVOB | FOXP3 | ETS | TCF1 | |

| EBF1 | PU1 | FOXC1 | TAF1 | HOXA13 | PLAGL2 | GATA1 | ETV7 | TCF11 | |

| EGR1 | PUR1 | FOXD2 | TATA | ISL2 | SP2 | GKLF | FOXC1 | TCFE2A | |

| EHF | RELA | FOXD3 | TBP | KID3 | SP3 | GR | FOXO1A | TFAP2C | |

| ELF1 | RORBETA | FOXG1 | TEF1 | KLF | SP6 | HMGIY | GATA2 | TORC2 | |

| ELF5 | SALL2 | FOXI1 | TTF1 | LKLF | VMYB | HOXA10 | GKLF | USF2 | |

| ELK1 | SATB1 | FOXK1 | ZNF333 | MAZR | ZBTB2 | HOXA13 | GMEB2 | VDRRXRALPHA | |

| ETS2 | SMAD | FOXL1 | MITF | HOXA2 | GR | ZBTB2 | |||

| ETV7 | SMAD2 | FOXM1 | NFAT1 | HOXD3 | HOXA13 | ZFP770 | |||

| FLI1 | SMAD5 | FOX01 | NFAT4 | HSF2 | HSF4 | ZNF333 | |||

| FOXA1 | SOX10 | FOXO1A | NFE4 | IK | IK | ZNF536 | |||

| FOXJ3 | SOX11 | FOXO3 | NR2E1 | IK2 | ING4 | ||||

| FOXL1 | SOX17 | FOXO4 | PLZFB | KID3 | IPF1 | ||||

| FOXM1 | SOX18 | FOXO6 | PMX1 | KLF | IRF7 | ||||

| FOXO1 | SOX30 | FOXP3 | RXRA | LHX2 | ISL2 | ||||

| FOXO1A | SOX4 | FRA1 | SALL2 | LKLF | IKD3 | ||||

| FOXO3A | SOX9 | FXR | SATB1 | MAX | LBP1 | ||||

| FOXP3 | SPI1 | GATA1 | SMAD5 | MEOX2 | LMX1 | ||||

| FRA1 | SPIB | GATA3 | SOX4 | MYB | LPOLYA | ||||

| GABPA | SREBP1 | GATA4 | SOX5 | MYCMAX | MEF2C | ||||

| GATA1 | SRY | GATA5 | SPIB | NF1A | MOVOB | ||||

| GATA2 | STAT | GSX1 | SREBP2 | NFATC2 | MTF1 | ||||

| GATA3 | STAT3 | GSX2 | SRY | NMYC | MYC | ||||

| GATA4 | TCF4 | HMGIY | TCF | 2-Oct | MYOD | ||||

| GKLF | TEL2 | HMX3 | TFE | PARP | MYOGENIN | ||||

| HDAC1 | THAP1 | HOXA1 | WT1 | PAX5 | MZF1 | ||||

| HMGIY | TORC2 | HOXA13 | ZAC | PEBP2B | NANOG | ||||

| HNF3A | USF | HOXA2 | ZFP641 | PMX1 | NEUROD | ||||

| HNF3G | USF2 | HOXB13 | ZNF333 | PR | NKX32 | ||||

| HOXA13 | VMYB | HOXB5 | ZNF641 | PRRX2 | NMYC | ||||

| HSF1 | WT1 | HOXC13 | RELA | NR1B2 | |||||

| HSF4 | YY1 | HOXD13 | SALL2 | NR2C2 | |||||

| IK | ZBTB44 | JUNB | SATB1 | 1-Oct | |||||

| ING4 | ZEB1 | KID3 | SMAD2 | OG2 | |||||

| IRF1 | ZFP532 | LBX2 | SOX10 | OTX | |||||

| IRF7 | ZFP536 | LMX1A | SOX17 | P300 | |||||

| KID3 | ZIC1 | LRH1 | SOX18 | PARP | |||||

| KLF | ZIC3 | MEF2D | SPIB | PAX5 | |||||

| KLF17 | ZNF333 | MEOX2 | SREBP2 | PEA3 | |||||

| LHX2 | ZNF367 | MIXL1 | TCF1 | PEBP2B | |||||

| LKLF | ZNF515 | MSX2 | TCF11 | PIT1 | |||||

Note: Key genes are highlighted in bold.

Abbreviation: PPi, protein–protein interaction.