Abstract

Objective

We aimed to evaluate whether high-dose cholecalciferol has beneficial effects on depression in pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) patients.

Methods

This pilot, randomized, and double-blind trial enrolled 123 recurrent PTB patients (aged ≥18 years) meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV) criteria of major depressive disorder from four hospitals in Southeast China. Patients were randomly assigned to 8-week oral treatment with 100,000 IU/week cholecalciferol (Vit D group) or a matching placebo (control group). The primary outcome was treatment response, defined as a 50% reduction in symptoms and change in scores of the Chinese version of Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) from baseline to 8 weeks. Relative risks of depression were estimated using multivariable logistic regression.

Results

Finally, 120 patients were enrolled, including 56 test patients and 64 controls. After 8 weeks, the treatment response or BDI scores did not differ significantly between groups. Multivariate logistic regression showed that BDI scores were not significantly improved in the Vit D group after adjustment for age, time to first negative smear, or 25-hydroxyvitamin D level.

Conclusion

The use of high-dose Vit D3 supplementation may not be warranted for reducing depressive symptoms in the PTB population. Nevertheless, this finding should be validated by further large-scale studies according to different kinds of depression or Vit D receptor polymorphism genotype.

Keywords: vitamin D, major depressive disorders, depression, tuberculosis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Background

Pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB), a chronic infectious disease, was the second major cause of death worldwide in 2016.1 PTB patients are faced with higher rates of comorbid depression compared with the general population.2–4 Depression affects 322 million people worldwide, and its prevalence has increased by 18.4% since 2005.5 Both depressive disorders and subthreshold depressive symptoms substantially threaten health and economy.6,7 Depression in PTB individuals is associated with delayed sought of health care and poor treatment compliance, which can lead to drug resistance, morbidity, and mortality.8 Tuberculosis (TB) patients are at an increased risk of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) deficiency compared with the general population.9,10 Several randomized trials report the effectiveness or safety of vitamin D (Vit D) supplementation to standard TB treatment,11–14 but bring about conflicting findings. Martineau et al found four doses of 2.5 mg Vit D3 elevated serum 25(OH)D concentrations in PTB patients receiving intensive phase treatment and reduced time to sputum culture conversion in participants with tt genotype of TaqI Vit D receptor polymorphism.12 However, Daley et al found inconsistent results without testing such polymorphism.11

Vit D, an essential nutrient for bone health, also performs other physiological functions such as anti-inflammation, antiproliferation, antibacterial action, prodifferentiation, and immunomodulation.15 Vit D is also a neurosteroid with fast non-genomic effects and genomic effect, which could be beneficial for mood disorders.16 Animal and experimental studies show that Vit D receptor interacts with glucocorticoid receptors in the hippocampus17 and 1,25(OH)2D3 promotes synthesis of monoamine neurotransmitters (eg, serotonin), which importantly protect brain function via immunomodulation, anti-inflammation, and neuroplasticity promotion.18,19 As for the effects of Vit D supplementation on depressive symptoms, recent meta-analyses of observational studies20 and randomized controlled trials (RCTs)21 reported that depressive symptoms were not associated with 25(OH)D concentrations or improved by Vit D supplementation. However, the existing studies are limited by the use of unrepresentative samples (Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease or psychiatric disorders), different diagnostic tools for quantification of depressive symptoms, co-interventions (eg, calcium or psychotropic drugs), and insufficient doses (<2,000 IU daily) to adequately raise 25(OH)D concentrations.22,23 Other limitations include variability in status and definition cutoffs of Vit D deficiency, inadequate observation duration (<8 weeks), and ignorance of important confounders (eg, physical activity, sun exposure, and dietary Vit D intake).

Thus, this pilot, randomized, and double-blind controlled study aimed to evaluate whether high-dose Vit D3 supplementation as adjunctive therapy has beneficial effects on depressive symptoms in recurrent PTB patients.

Methods

Study design

This 8-week pilot, randomized, and double-blind controlled study was conducted at four centers in Southeast China.

The study coordinator verified all eligibility criteria before randomization, and divided the patients into two groups via block randomization with a block size of six and an allocation ratio of 1:1. The coordinator generated the allocation sequence independently and concealed in opaque envelopes. Neither investigators nor patients were aware of the allocations. Once study eligibility and informed consent for a patient were verified, the coordinator opened the sealed envelope to ascertain the random treatment assigned to that patient. Once a randomization assignment was made, the coordinator enrolled that patient. Meanwhile, those doing end point psychiatric interviews at baseline and 8 weeks and those assessing outcomes were masked to treatment assignment.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Recurrent PTB (relapse of original episode or an exogenous reinfection caused by a different strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis) participants (age ≥18 years), who were HIV-negative and had depression, were eligible for inclusion if they had taken standard TB re-treatment. Exclusion criteria were as follows: age <18 years; preexisting renal or hepatic failure, pulmonary silicosis, malignancy, metastatic malignant disease, sarcoidosis, hyperparathyroidism, nephrolithiasis, HIV co-infection, active diarrhea, hypercalcemia, pregnancy or lactation, concurrent steroid, cytotoxic drug treatment or other immunosuppressant therapies in the month before enrollment; intolerance of Vit D or first-line anti-TB therapies; cognitive deficits (eg, considerable memory loss, confusion/dementia, and intellectual disability); illiteracy or inability to answer the questionnaire (difficulty in understanding the questions, visual or hearing impairment); and severe depressive symptoms before treatment.

Study procedures

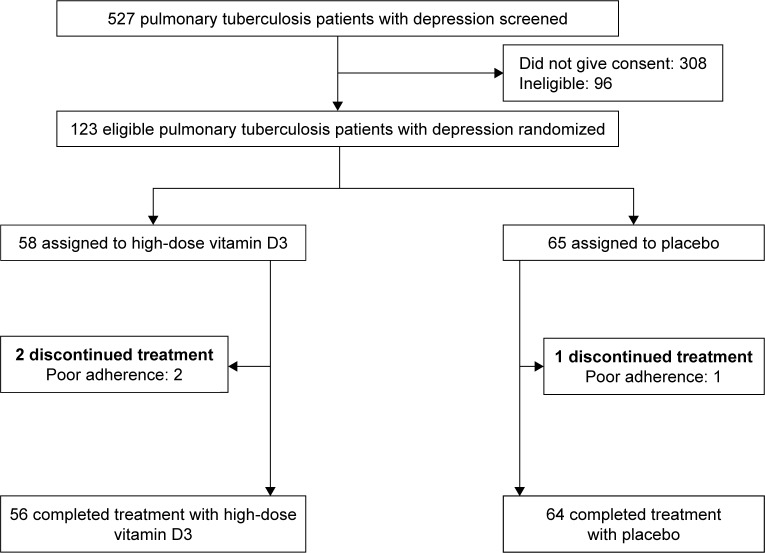

Between July 1, 2015, and July 31, 2017, 123 (23.3%) of 527 patients were screened and consented to participate in the study (Figure 1). The participants were randomly assigned to a bolus oral dose of 100,000 IU/week cholecalciferol (Vit D group) or a matching placebo indistinguishable from cholecalciferol in terms of color, form, or taste (control group) for 8 weeks. This study was approved by the institutional ethics review board of Ningbo University College of Medicine (Approval No 20150126) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patient enrollment.

Advices on lifestyle modification which helped to alleviate depressive symptoms in PTB patients were also given, such as daily intake of Vit D and Ca from food. Dietary intake at both baseline and over the 8 weeks was assessed by a self-administered food-frequency questionnaire specifically for Women’s Health Initiative.24 The participants were asked to abstain from consuming Vit D-/Ca-containing foods during the study period based on a standard questionnaire.25

Safety and adherence of the participants were assessed. Adherence was evaluated by the ratio of actual take to study medication (including placebo) using a questionnaire, and a ratio of ≥80% indicated good adherence. Study medication was withheld upon the occurrence of any severe adverse event for Vit D (eg, swelling, itching, chapped lips, headache, constipation, diarrhea, pharyngitis, esophagitis, stomatitis, nausea, or vomiting), or any condition wherein discontinuation of Vit D3 treatment was deemed medically necessary by the physician in charge.

Evaluation of depression and depressive symptoms

Major depressive disorder was diagnosed according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV). Change in scores of depressive symptoms was evaluated with the Chinese version of Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) II. Treatment responders for BDI II were those with at least 50% improvement of total score from baseline ([baseline – post]/baseline ≥50%).26 BDI II consists of 21 self-reported items, and each item is rated on a scale of 0–3, producing a possible score from 0 to 63. A BDI II score ≥11 indicates the presence of depressive symptoms,27 and a larger score indicates higher severity.28 Diagnosis and severity of depression for each patient were determined independently by two experienced psychiatrists through structured interviews.

Demographic data, laboratory measurements, and other outcomes

Demographic data, including history of smoking and drinking, income, and family history of mood disorders, were collected by questioning the patients. Information concerning age, sex, occupation, and time to first negative smear was gathered from medical records. Basic laboratory parameters including baseline plasma levels of hemoglobin and Ca were measured via standard methods. Other laboratory data including nutrient indexes (plasma albumin, prealbumin) and inflammatory biomarkers (high-sensitivity C-reactive protein [Hs-CRP], interleukin [IL]-6, tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α, and interferon [INF]-γ) were also detected. Plasma 25(OH)D (Vit D2 + Vit D3) levels were measured using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry.29

Statistical analysis

The sample size of 123 in this two-group study was calculated to be adequately powerful (α=0.05 in two-sided t-test) for the tests. Results were expressed as mean ± SD with significance level at P<0.05. Differences in mean values were tested using an independent t-test or Mann–Whitney test. Quartiles were compared with the Kruskal–Wallis test or chi-squared test as appropriate.

Through multifactorial logistic regression, the 95% CIs for the relation between Vit D3 supplementation and BDI II scores were calculated with adjustment for putative moderators, such as age, time to first negative smear, and plasma 25(OH)D level. All statistical analyses were conducted on SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) or SAS 8.5 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Characteristics of patients

During the 8-week period, three of the 123 patients were excluded (two in Vit D group, one in control group) because of poor adherence. Basic laboratory data and sociodemographic characteristics of the 123 patients are depicted in Table 1. No significant between-group difference was found at baseline.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical data of the groups

| Characteristics | Vit D group (n=58) | Control group (n=65) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 38.3 (12.4) | 40.2 (11.9) | 0.41 |

| Sex: male, n (%) | 50 (86.2) | 53 (81.5) | 0.48 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 2 (3.4) | 3 (4.6) | 0.74 |

| Drinking, n (%) | 20 (34.5) | 20 (30.8) | 0.66 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 16 (27.6) | 21 (32.3) | 0.57 |

| Income, n (%) | 0.29 | ||

| Under minimum wage standard | 9 (15.5) | 15 (23.1) | |

| Over minimum wage standard | 49 (84.5) | 50 (76.9) | |

| Education, n (%) | 0.25 | ||

| Up to high school | 38 (65.5) | 36 (55.4) | |

| Beyond high school | 20 (34.5) | 29 (44.6) | |

| Health insurance modes, n (%) | 0.43 | ||

| Medical insurance | 41 (70.7) | 50 (76.9) | |

| New rural insurance/urban resident basic medical insurance | 17 (29.3) | 15 (23.1) | |

| Employed, n (%) | 15 (25.9) | 23 (35.4) | 0.25 |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.12 | ||

| Not single (married/living together) | 48 (82.8) | 46 (70.8) | |

| Single (single/widow(er)/divorced/living apart) | 10 (17.2) | 19 (29.2) | |

| Family history of mood disorders (%) | 6 (10.3) | 4 (6.1) | 0.40 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 21.2 (3.8) | 20.7 (4.1) | 0.22 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L), mean (SD) | 12.6 (5.4) | 12.3 (2.7) | 0.26 |

| Plasma corrected calcium (mmol/L) | 2.5 (0.3) | 2.5 (0.4) | 0.47 |

| Plasma Hs-CRP (mg/L), mean (SD) | 45.1 (13.3) | 37.5 (12.6) | 0.31 |

| Plasma albumin (g/L), mean (SD) | 33.2 (7.8) | 32.7 (4.3) | 0.27 |

| Plasma prealbumin (mg/L), mean (SD) | 223.6 (37.9) | 235.9 (48.1) | 0.16 |

| Plasma 25(OH)D (ng/mL), mean (SD) | 22.9 (7.1) | 24.5 (4.6) | 0.39 |

| BDI II scores, mean (SD) | 24.6 (13.1) | 23.3 (10.5) | 0.31 |

| Dietary Vit D intake (IU/d), mean (SD) | 147.9 (67.1) | 164.3 (58.7) | 0.55 |

Notes: Differences in proportions were tested using Pearson chi-squared test, and differences in mean values were tested using one-way ANOVA or Mann–Whitney test. Each group was compared separately with the placebo group.

Abbreviations: 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BMI, body mass index; Hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; Vit D, vitamin D.

Efficacy of adjunctive high-dose Vit D3 supplementation on bone metabolism indexes, nutrient indexes, and inflammatory biomarkers

Changes in bone metabolism indexes (Ca, 25(OH)D, Vit D2 + Vit D3), nutrient indexes (plasma albumin and prealbumin), and inflammatory biomarkers (IL-6 and TNF-α) are shown in Table 2. After treatment, the mean plasma corrected Ca levels remained well within the normal range. Plasma 25(OH) D levels increased more significantly in the Vit D group (P=0.03). Plasma albumin and prealbumin levels increased more in the Vit D group, but not significantly. The changes in IL-6, TNF-α, and INF-γ were all significantly different between groups.

Table 2.

Baseline and 8-week values of Vit D and placebo groups

| Vit D group (n=56)

|

Placebo group (n=64)

|

P for delta value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 8 weeks | Delta* | Baseline | 8 weeks | Delta* | ||

|

| |||||||

| Bone metabolism indexes, mean (SD) | |||||||

| Plasma corrected calcium (mmol/L) | 2.5 (0.3) | 2.5 (0.5) | 0.04 (0.01) | 2.5 (0.4) | 2.5 (0.5) | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.37 |

| Plasma 25(OH)D (ng/mL) | 22.9 (7.1) | 27.1 (8.3) | 4.2 (2.1) | 24.5 (4.6) | 23.6 (8.1) | −0.7 (0.5) | 0.03 |

| Nutrient indexes, mean (SD) | |||||||

| Plasma albumin (g/L) | 33.2 (7.8) | 34.1 (5.9) | 1.0 (2.2) | 32.7 (4.3) | 32.3 (6.7) | −0.5 (1.2) | 0.23 |

| Plasma prealbumin (mg/L) | 223.6 (37.9) | 230.4 (41.6) | 7.0 (4.7) | 235.9 (48.1) | 232.1 (36.4) | −6.0 (4.9) | 0.35 |

| Inflammatory biomarkers, mean (SD) | |||||||

| Plasma Hs-CRP (mg/L) | 45.1 (13.3) | 41.2 (22.8) | −4.0 (3.3) | 37.5 (12.6) | 36.2 (10.8) | −1.3 (1.1) | 0.81 |

| Plasma IL-6 (pg/mL) | 227.4 (82.3) | 202.8 (67.3) | −24.6 (13.4) | 259.1 (114.9) | 242.6 (89.4) | −16.5 (18.9) | 0.053 |

| Plasma TNF-α (pg/mL) | 104.9 (35.1) | 90.4 (25.6) | −10.0 (7.3) | 123.6 (24.8) | 115.8 (19.5) | −7.8 (5.3) | 0.041 |

| Plasma INF-γ (pg/mL) | 87.3 (20.5) | 75.4 (16.6) | −12.0 (5.1) | 121.4 (55.6) | 116.9 (37.1) | −4.5 (3.5) | 0.022 |

Note:

8-week score minus score at baseline.

Abbreviations: 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; Hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin-6; INF-γ, interferon-γ; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; Vit D, vitamin D.

Efficacy of adjunctive high-dose Vit D3 supplementation on time to first negative smear and depression

No significant difference in time to first negative smear was found between the Vit D group and the control group (47.3 days [95% CI: 35.1–54.3] vs 51.2 days [95% CI: 37.4–56.6]).

Totally, 16 (28.1% [95% CI: 0.17–0.40]) treatment responders were found in the Vit D group after 8 weeks compared with 16 (25.0% [95% CI: 0.14–0.36]) in the control group, without significant difference between groups (P=0.86).

After 8-week treatment, the BDI scores in the Vit D group (16.6±9.4 vs 24.6±13.1, P=0.02) and the control group (16.9±8.3 vs 23.3±10.5, P=0.03) both decreased significantly compared to the baseline. However, the delta values (score at 8 weeks minus score at baseline) were not significantly different between groups. Multivariable logistic regression showed that Vit D3 supplementation could not improve BDI scores in the Vit D group vs the control group after adjustment for age, time to first negative smear, or 25(OH)D level (95% CI: −2.75 to 0.89, P=0.38) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of Vit D3 supplementation with change in mean BDI II score from baseline to 8-week follow-up

| Baseline, mean (SD) | 8 weeks, mean (SD) | Delta*,a, mean (SD) | Multivariable-adjusted mean change (95% CI)b | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Vit D group (n=56) | 24.6 (13.1) | 16.6 (9.4) | −8.0 (3.7) | −1.63 (−2.75 to 0.89) | 0.38 |

| Control group (n=64) | 23.3 (10.5) | 16.9 (8.3) | −6.4 (4.9) | Reference | |

Notes:

Positive change reflects a higher BDI II score at 8 weeks vs baseline; negative change reflects a lower BDI II score at 8 weeks vs baseline.

Multivariable models adjusted for age, time to first negative smear, and 25(OH)D levels.

Score at 8 weeks minus score at baseline.

Abbreviations: 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; Vit D, vitamin D.

Compliance assessment and adverse effects

All participants showed good adherence (taking ≥80% of study medication), except three patients. Adverse events led to discontinuation of medication in the Vit D group, including itching (1) and nausea (1).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first RCT of adjunctive high-dose Vit D3 for depression in recurrent PTB patients. Multivariable logistic regression models suggest that high-dose Vit D3 supplementation may not be warranted for reducing depressive symptoms compared to the placebo in the PTB population despite a greater rise in plasma 25(OH)D level in the Vit D group. The association of Vit D supplementation with depression risk or depressive symptom alleviation has been evaluated in several intervention trials.30–32 However, their findings are inconsistent because of between-study differences in races, study populations, geographic locations, Vit D doses, depression assessment, follow-up duration, use of placebo, sample size, and participant characteristics. Two systematic reviews and meta-analyses based on RCTs showed that low Vit D concentration is associated with depression20 and Vit D supplementation may be effective in reducing symptoms of clinically significant depression.33 A recent meta-analysis34 suggested that Vit D supplementation favorably impacted depression ratings in major depression with a moderate effect size, but the authors thought this finding must be considered tentative owing to the limited number of trials available (only four) and inherent methodological bias noted in a few of the trials. Another systematic review showed no significant reduction in depression after Vit D supplementation, which may be because the enrolled studies mostly focused on individuals with low depression and sufficient serum Vit D at baseline.21 Meanwhile, some researchers think the depressive state may be a cause rather than a consequence of Vit D deficiency, since plasma Vit D level alleviates physical activity (time spent outdoor) after the occurrence of depression.

The pathways for the TB and depression associations are probably complex and multidirectional.35 First, under chronic pulmonary conditions, hypoxia can directly make patients anxious and depressed. Likewise, general factors associated with chronic disease such as weight loss, fatigue, and psychological and social losses may trigger depressive reactions.36 In our study, albumin and prealbumin levels were tested to provide evidence for the mechanism by which high-dose Vit D3 supplementation might improve depression, but these two nutrient indexes were not significantly altered by the supplementation after 8-week follow-up. Nevertheless, experts agree that people with chronic diseases and comorbid depression can benefit from chronic disease treatments. Second, anti-TB medications, especially isoniazid, the first monoamine oxidase inhibitor to be considered for the treatment of mental disorders in the 1950s37 and now a core drug in anti-TB treatment, may significantly interact with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors,37 which are WHO-recommended drugs for depression treatment in the Mental Health Gap Action Programme guideline. In addition, TB patients may develop depression as a result of chronic infection or related psychosocioeconomic stressors.36 Finally, no evidence suggests that TB and depression may share risk factors.38,39 Immunological responses have been implicated in the association between chronic disease and depression. Chronic infectious conditions may lead to overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (eg, IL-6), which facilitate cascades of endocrine reactions that may result in depressive symptoms.38 However, growing evidence shows that depression enhances the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and directly minimizes the immunological competence of patients by downregulating cellular and humoral responses.40 Four inflammatory biomarkers (Hs-CRP, IL-6, TNF-α, and INF-γ) were tested in our study to provide evidence for the mechanism by which high-dose Vit D3 supplementation might cause depression. After 8-week follow-up, the 100,000 IU/week Vit D3 supplementation did not significantly alter the BDI II scores as a whole, but significantly changed the mean plasma nutrient indexes. We could not find the reason about these phenomena, owing to our incomplete understanding about the depression and inflammation relation. Thus, these findings need to be assessed in the future.

Some limitations in the present study should be noted. First, although we assessed a broad range of depressive disorders, it was difficult to ascertain the specific causes and phase of depression within the sample. In addition, seasonal affective disorder was not analyzed. Second, like in most previous studies, we did not survey vascular depression, which could benefit from high-dose oral Vit D3 supplementation.32 Third, we did not test the polymorphism of the Vit D receptor, genetic variance of which influences the susceptibility to age-related changes in cognitive functioning and depressive symptoms.41 Fourth, the sample size was relatively small, since some statistics (P-value) for the results are critical.

Conclusion

The high-dose Vit D3 supplementation may not be warranted for reducing depressive symptoms in the PTB population. Further large-scale studies are needed to establish whether Vit D supplementation may be beneficial for improving depressive symptoms in PTB groups, according to different types of depression or to Vit D receptor polymorphism genotype.

Footnotes

Author contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Floyd K, Glaziou P, Zumla A, Raviglione M. The global tuberculosis epidemic and progress in care, prevention, and research: an overview in year 3 of the End TB era. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(4):299–314. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gong Y, Yan S, Qiu L, et al. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and related risk factors among patients with tuberculosis in china: a multistage cross-sectional study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98(6):1624–1628. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koyanagi A, Vancampfort D, Carvalho AF, et al. Depression comorbid with tuberculosis and its impact on health status: cross-sectional analysis of community-based data from 48 low- and middle-income countries. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):209. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0975-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Husain MO, Dearman SP, Chaudhry IB, Rizvi N, Waheed W. The relationship between anxiety, depression and illness perception in tuberculosis patients in Pakistan. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2008;4:4. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedrich MJ. Depression is the leading cause of disability around the world. JAMA. 2017;317(15):1517. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broadhead WE, Blazer DG, George LK, Tse CK. Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA. 1990;264(19):2524–2528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pietrzak RH, Kinley J, Afifi TO, Enns MW, Fawcett J, Sareen J. Subsyndromal depression in the United States: prevalence, course, and risk for incident psychiatric outcomes. Psychol Med. 2013;43(7):1401–1414. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712002309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pachi A, Bratis D, Moussas G, Tselebis A. Psychiatric morbidity and other factors affecting treatment adherence in pulmonary tuberculosis patients. Tuberc Res Treat. 2013;2013:489865. doi: 10.1155/2013/489865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nnoaham KE, Clarke A. Low serum vitamin D levels and tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(1):113–119. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bazzano AN, Littrell L, Lambert S, Roi C. Factors associated with vitamin D status of low-income, hospitalized psychiatric patients: results of a retrospective study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:2973–2980. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S122979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daley P, Jagannathan V, John KR, et al. Adjunctive vitamin D for treatment of active tuberculosis in India: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(5):528–534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martineau AR, Timms PM, Bothamley GH, et al. High-dose vitamin D(3) during intensive-phase antimicrobial treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis: a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9761):242–250. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61889-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nursyam EW, Amin Z, Rumende CM. The effect of vitamin D as supplementary treatment in patients with moderately advanced pulmonary tuberculous lesion. Acta Med Indones. 2006;38(1):3–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wejse C, Gomes VF, Rabna P, et al. Vitamin D as supplementary treatment for tuberculosis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(9):843–850. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200804-567OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grant WB, Boucher BJ. Requirements for Vitamin D across the life span. Biol Res Nurs. 2011;13(2):120–133. doi: 10.1177/1099800410391243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qureshi NA, Al-Bedah AM. Mood disorders and complementary and alternative medicine: a literature review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:639–658. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S43419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Obradovic D, Gronemeyer H, Lutz B, Rein T. Cross-talk of vitamin D and glucocorticoids in hippocampal cells. J Neurochem. 2006;96(2):500–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Annweiler C, Montero-Odasso M, Schott AM, Berrut G, Fantino B, Beauchet O. Fall prevention and vitamin D in the elderly: an overview of the key role of the non-bone effects. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2010;7:50. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-7-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kesby JP, Eyles DW, Burne TH, McGrath JJ. The effects of vitamin D on brain development and adult brain function. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;347(1–2):121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anglin RE, Samaan Z, Walter SD, McDonald SD. Vitamin D deficiency and depression in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:100–107. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.106666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gowda U, Mutowo MP, Smith BJ, Wluka AE, Renzaho AM. Vitamin D supplementation to reduce depression in adults: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrition. 2015;31(3):421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ilahi M, Armas LA, Heaney RP. Pharmacokinetics of a single, large dose of cholecalciferol. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(3):688–691. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.3.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vieth R, Chan PC, MacFarlane GD. Efficacy and safety of vitamin D3 intake exceeding the lowest observed adverse effect level. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73(2):288–294. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.2.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng TY, Lacroix AZ, Beresford SA, et al. Vitamin D intake and lung cancer risk in the Women’s Health Initiative. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(4):1002–1011. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.055905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chandler PD, Scott JB, Drake BF, et al. Impact of vitamin D supplementation on adiposity in African-Americans. Nutr Diabetes. 2015;5:e164. doi: 10.1038/nutd.2015.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egede LE, Acierno R, Knapp RG, et al. Psychotherapy for depression in older veterans via telemedicine: a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(8):693–701. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00122-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loosman WL, Rottier MA, Honig A, Siegert CE. Association of depressive and anxiety symptoms with adverse events in Dutch chronic kidney disease patients: a prospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16:155. doi: 10.1186/s12882-015-0149-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sezer S, Uyar ME, Bal Z, Tutal E, Ozdemir Acar FN. The influence of socioeconomic factors on depression in maintenance hemodialysis patients and their caregivers. Clin Nephrol. 2013;80(5):342–348. doi: 10.5414/CN107742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones G. Interpreting vitamin D assay results: proceed with caution. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(2):331–334. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05490614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arvold DS, Odean MJ, Dornfeld MP, et al. Correlation of symptoms with vitamin D deficiency and symptom response to cholecalciferol treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Endocr Pract. 2009;15(3):203–212. doi: 10.4158/EP.15.3.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dean AJ, Bellgrove MA, Hall T, et al. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on cognitive and emotional functioning in young adults – a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e25966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, Liu Y, Lian Y, Li N, Liu H, Li G. Efficacy of high-dose supplementation with oral vitamin D3 on depressive symptoms in dialysis patients with vitamin D3 insufficiency: a prospective, randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;36(3):229–235. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaffer JA, Edmondson D, Wasson LT, et al. Vitamin D supplementation for depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom Med. 2014;76(3):190–196. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vellekkatt F, Menon V. Efficacy of vitamin D supplementation in major depression: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Postgrad Med. 2018 Jun;:21. doi: 10.4103/jpgm.JPGM_571_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ambaw F, Mayston R, Hanlon C, Alem A. Depression among patients with tuberculosis: determinants, course and impact on pathways to care and treatment outcomes in a primary care setting in southern Ethiopia – a study protocol. BMJ Open. 2015;5(7):e007653. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mikkelsen RL, Middelboe T, Pisinger C, Stage KB. Anxiety and depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2004;58(1):65–70. doi: 10.1080/08039480310000824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doherty AM, Kelly J, McDonald C, O’Dywer AM, Keane J, Cooney J. A review of the interplay between tuberculosis and mental health. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(4):398–406. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R. Depression and immune function: central pathways to morbidity and mortality. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(4):873–876. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katon W, Lin EH, Kroenke K. The association of depression and anxiety with medical symptom burden in patients with chronic medical illness. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(2):147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katon WJ. Epidemiology and treatment of depression in patients with chronic medical illness. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13(1):7–23. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.1/wkaton. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuningas M, Mooijaart SP, Jolles J, Slagboom PE, Westendorp RG, van Heemst D. VDR gene variants associate with cognitive function and depressive symptoms in old age. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30(3):466–473. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]