Abstract

Purpose

Spirulina is generally used as a nutraceutical food supplement due to its nutrient profile, lack of toxicity, and therapeutic effects. Clinical trials have investigated the influence of spirulina on metabolic-related risk factors but have yielded conflicting results in humans. Here, we summarize the evidence of the effects of spirulina on serum lipid profile, glucose management, BP, and body weight by conducting a meta-analysis.

Materials and methods

Relevant studies were retrieved by systematic search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus databases, and reference lists of relevant original studies from inception to July 2018. Data were extracted following a standardized protocol. Two investigators independently extracted study characteristics, outcomes measures, and appraised methodological quality. Effect sizes were performed using a random-effects model, with weighted mean differences (WMDs) and 95% CIs between the means for the spirulina intervention and control arms. Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore the possible influences of study characteristics. Publication bias and sensitivity analysis were also performed.

Results

A total of 1,868 records were identified of which 12 trials with 14 arms were eligible. The amount of spirulina ranged from 1 to 19 g/d, and intervention durations ranged from 2 to 48 weeks. Overall, data synthesis showed that spirulina supplements significantly lowered total cholesterol (WMD = −36.60 mg/dL; 95% CI: −51.87 to −21.33; P=0.0001), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (WMD = −33.16 mg/dL; 95% CI: −50.52 to −15.75; P=0.0002), triglycerides (WMD = −39.20 mg/dL; 95% CI: −52.71 to −25.69; P=0.0001), very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (WMD = −8.02 mg/dL; 95% CI: −8.77 to −7.26; P=0.0001), fasting blood glucose (WMD = −5.01 mg/dL; 95% CI: −9.78 to −0.24; P=0.04), and DBP (WMD = −7.17 mmHg; 95% CI: −8.57 to −5.78; P=0.001). These findings remained stable in the sensitivity analysis, and no obvious publication bias was detected.

Conclusion

Our findings provide substantial evidence that spirulina supplementation has favorable effect on select cardiovascular and metabolic biomarkers in humans, including lipid, glucose, and DBP management.

Keywords: blood pressure, body weight, blood glucose, CVD, lipid, spirulina

Introduction

CVD is the major cause of morbidity, mortality, and disability worldwide; with the global aging of populations, the prevalence of CVD is increasing rapidly.1 According to the World Health Organization reports, >17.3 million people die of CVD every year, and the number of CVD-related deaths is projected to rise to >23.6 million by the year 2030.1 Accumulating epidemiological evidence revealed that dyslipidemias and hypertension are the key factors for the pathogenesis and development of CVD.2,3 Compared with healthy subjects, those patients with hyperlipidemia and elevated BP are at increased risk of heart attack, strokes, and ischemic heart disease.4–6 Based on the guidelines of American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), the primary target for CVD prevention and treatment is to decrease the potential CVD risk factors by reducing LDL-C, BP, body weight, and glucose to recommended levels.7 In recent decades, the potential cardiovascular protective properties of natural products have been reported, with evidence to confirm that dietary natural products or functional foods supplementation were generally applied to improve lipid management, insulin resistance, BP control, markers of inflammation and antioxidant status, and CVD-related complications.8–12

Spirulina (Arthrospira platensis), a species of filamentous cyanobacteria, is generally used as a nutraceutical food supplement. Spirulina is rich in vitamins, minerals, protein, carotenoids, phycocyanins, essential fatty acids, and other bioactive molecules such as phenolic acids, tocopherols, and glinolenic acid.13,14 Spirulina platensis and Spirulina maxima have been broadly studied in the field of medicine and food industry due to its nutrient profile, lack of toxicity, and therapeutic effects. Accumulating evidence has shown that spirulina exerts health promoting functions, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antitumor, antiviral, antibacterial activities, as well as positive effects against hyperlipidemia, obesity, and diabetes.15–18 In clinical practice, several studies are focusing on the potential effects of spirulina on the prevention and treatment of CVD due to its high antioxidant activity.19–23 However, results are inconsistent and no meta-analysis has specifically pooled nor summarized the precise effect of spirulina consumption on cardiovascular risk factors. We therefore undertook a comprehensive meta-analysis to investigate the effects and safety of spirulina supplementation on multiple markers of cardiovascular health in humans. The present study provides an insight into the potential clinical applications of spirulina in CVD and may also highlight some suggestions for future research.

Materials and methods

Protocol and guidelines

This pooled analysis was based on a protocol that was prepared according to recommendations described in the Cochrane Handbook and report based on the PRISMA guidelines.24

Trial and patient inclusion criteria

Only trials were eligible for inclusion in this study satisfied the following criteria: 1) studies using spirulina as only intervention and studies in which spirulina was combined with other interventions were included when the control group received the same treatment; 2) the doses of spirulina intervention were reported in the trial; 3) studies with a parallel or crossover design that compared spirulina with placebo or no treatment control; 4) studies were human clinical trials; 5) studies should be providing sufficient information on baseline and post-treatment outcome markers in both spirulina and control groups; 6) the primary metabolic risk factors were TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, vLDL-C, FBG, HbA1c, SBP, DBP, body weight, and BMI.

Data sources and literature search

We performed a systematic literature search of several databases, including MEDLINE (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed), EMBASE (http://www.embase.com), and Scopus databases (https://www.scopus.com) from inception to July 1, 2018. Specifically, we used the following Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and corresponding key words as search terms: (“spirulina” OR “spirulina*” OR “spirulina platen-sis” OR “spirulina maxima” OR “spirulina fusiformis” OR “Arthrospira”). The search was limited to English-language publications and clinical trials that conducted in human subjects. To identify any other potentially missing paper, manual searches of reference lists in relevant papers, specialist journals, and conference proceedings were also performed. Trials identified from literature searches were listed, and the trials included were selected using the criteria described above. All authors participated in the selection of trials for inclusion.

Assessment of study quality and data extraction

Two independent reviewers completed data extraction and quality assessment. The qualities of included studies were assessed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool.25 We obtained information on randomization sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and study personnel, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other biases. The risk of bias in each study was judged to be “low,” “high,” or “unclear.” The data were extracted using a predesigned data collection check form, and disagreements were resolved through discussion. Trial characteristics recorded included author identification, year of publication, study population, sample size, details of the study design, length of follow-up, participants’ mean age, spirulina dose and formulation used, types of control, and outcomes of interest. In each trial, the means and SDs of the primary outcomes at the baseline and endpoint both in intervention and control groups were extracted. If the SDs were not provided directly, we calculated them from standard error mean (SEM) or 95% CI with the equations listed in the Cochrane handbook.

Statistical analysis

For continuous outcomes, we calculated the effect sizes as WMD and 95% CI between the spirulina intervention and control arms. The degree of statistical heterogeneity among studies was determined using the I2 statistic, with a value of <25%, 26%–50%, and >50% considered as low, moderate, and high level of heterogeneity, respectively.26 All analyses were based on the random-effects model. In order to evaluate the robustness of our findings, sensitivity analyses were performed by removing one study each time and pooling the remaining ones (the “leave one out” approach). Potential moderating factors were evaluated by subgroup analysis including types of controls used, spirulina dose, and intervention duration. The subgroup analyses were performed only for the effect of spirulina products on lipid profiles because of small numbers of studies for other outcomes. The presence of publication bias was assessed visually and quantitatively using Egger’s weighted regression statistics.27 All statistical analyses were performed using STATA software version 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Reported P-values are two tailed, and P<0.05 was considered significant for all analyses, except where otherwise specified.

Results

Search results and trial flow

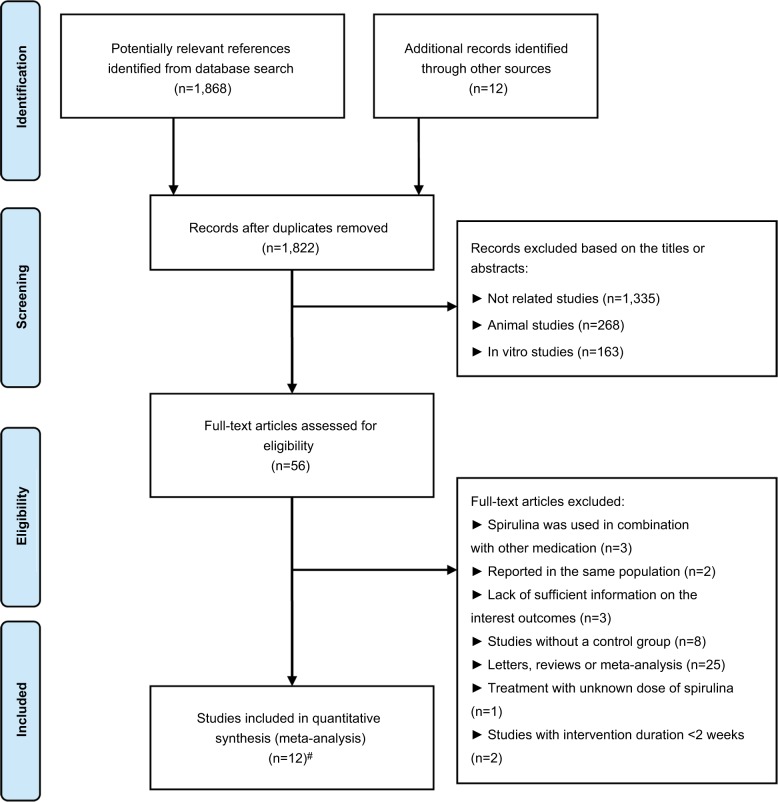

From the electronic searches, 1,868 potential literature citations were retrieved. On review of references from relevant identified reviews, an additional 12 studies potentially meeting our inclusion criteria were identified. Of these, 56 articles were selected for detailed evaluation. After full-text assessment according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 44 of these studies were excluded. Overall, a total of 12 studies (equivalent to 14 treatment arms) with 807 participants were finally considered to be selected for the current meta-analysis.19–23,28–34 Study selection and identification process are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of database searches and articles included in the present meta-analysis.

Notes: #The work conducted by Ramamoorthy et al21 and Park et al20 were separated into two treatment arms, respectively.

Characteristics and quality of the included studies

The details of the study characteristics of the sample, interventions, outcome assessment, and results are provided in Table 1. These included studies were published between 1996 and 2017 and were conducted in five different countries, including India, Korea, USA, Cameroon, and Poland. The number of participants ranged from 20 to 169. The mean age of participants in each trial ranged from 7.28 to 65.9 years. A range of doses from 1 to 19 g/d of spirulina was administered in the included trials. The duration of the spirulina intervention varied from 2 to 24 weeks, with nine studies having treatment durations ≥12 weeks and the remaining three having treatment durations <12 weeks. All trials were designed as parallel-group studies. Among the included studies, five trials used the placebo as the control, six trials used no intervention as the control, and one study used soybean as the control. Selected studies were performed in subjects who suffered from type 2 diabetes mellitus, HIV-infected, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, and hyperlipidemic nephrotic syndrome. The systematic assessment of risk-of-bias summary is provided in Figure S1. Overall, five trials were considered as a low risk of bias, six as a high risk of bias, and one as unclear.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the included studies

| Reference | Years | Study design | Location | Sample size | Target population | Mean age (year) | BMI (kg/m2) | Intervention

|

Dose (g/d) | Duration (week) | Main outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment group | Control group | |||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Anitha et al19 | 2010 | Parallel-group trial | India | 80 | Male volunteers with type 2 diabetes | 45–60 | NA | Spirulina intervention | No intervention | 1 | 12 | TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, vLDL-C, FBG |

| Lee et al29 | 2008 | Randomized, parallel study | Korea | 37 | Patients with type 2 diabetes | 53.30 | 23.60 | Freeze-dried spirulina | No intervention | 8 | 12 | TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, vLDL-C, FBG, SBP, DBP |

| Jensen et al28 | 2016 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled parallel study | USA | 24 | Adult men and women 25–65 years of age | 45.55 | 29.65 | Phycocyanin- enriched aqueous extract from Spirulina platensis | Received placebo | 2.3 | 2 | SBP, DBP, FBG |

| Marcel et al30 | 2011 | Randomized, parallel study | Cameroon | 33 | HIV-infected patients | 37.50 | 24.25 | Spirulina platensis | Received soybean | 19 | 8 | TG, TC, FBG |

| Miczke et al31 | 2016 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled parallel study | Poland | 40 | Overweight hypertensive Caucasians | 53.30 | 26.30 | Received Hawaiian spirulina | Received placebo | 2 | 12 | SBP, DBP, body weight, BMI |

| Ngo-Matip et al32 | 2014 | Randomized, single-blind, multicenter study | Cameroun | 159 | HIV-infected antiretroviral-naive patients | 35.72 | 25.65 | Spirulina supplementation | No intervention | 10 | 24 | TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, FBG, BMI |

| Parikh et al33 | 2001 | Randomized placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial | India | 25 | Subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus | 54.20 | 25.15 | Spirulina tablets supplementation | Received placebo | 2 | 8 | TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, FBG |

| Park et al20 | 2008 | Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled parallel trial | Korea | 78 | Individuals aged 60–87 years | 65.90 | 24.35 | Receive freeze- dried spirulina pills | Received placebo | 8 | 16 | TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG |

| Ramamoorthy_a et al21 | 1996 | Parallel-group trial | India | 20 | Ischemic heart disease patients without any complications of the disease and with blood cholesterol levels above 250 mg/dL | 40–60 | NA | Received spirulina | No intervention | 2 | 12 | TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, Body weight, |

| Ramamoorthy_b et al21 | 1996 | Parallel-group trial | India | 20 | Ischemic heart disease patients without any complications of the disease and with blood cholesterol levels above 250 mg/dL | 40–60 | NA | Received spirulina | No intervention | 4 | 12 | TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, body weight |

| Samuels et al22 | 2002 | Parallel-group trial | India | 23 | Patients with hyperlipidemic nephrotic syndrome | 7.28 | 15.24 | Spray-dried spirulina capsules supplementation | No intervention | 1 | 8 | TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, vLDL-C, FBG, body weight, BMI |

| Zeinalian et al34 | 2017 | Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled parallel trial | Iran | 57 | Obese individuals | 34.33 | 33.03 | Received spirulina platensis | Received placebo | 1 | 12 | TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, FBG, body weight, BMI |

| Szulinska et al23 | 2017 | Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled parallel trial | Poland | 50 | Subjects with treated hypertension | 49.75 | 33.40 | Received spirulina | Received placebo | 2 | 12 | TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, FBG, body weight, BMI |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NA, not applicable; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; vLDL-C, very-low-density cholesterol.

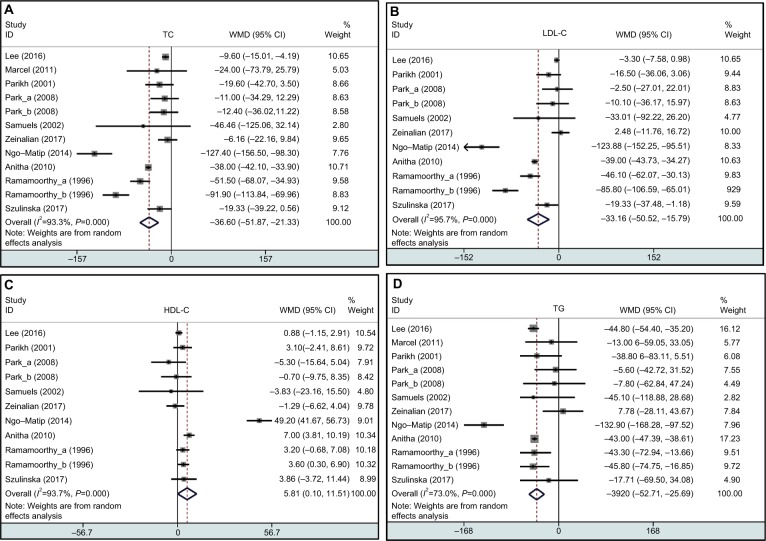

Effect of spirulina supplementation on plasma lipid and glucose concentrations, body weight, and BP

For the change of lipid profiles, as shown in Figure 2, the pooled result showed that spirulina supplements significantly lower the TC (12 treatment arms; WMD = −36.60 mg/dL; 95% CI: −51.87 to −21.33; P=0.0001; I2=93%), LDL-C (11 treatment arms; WMD = −33.16 mg/dL; 95% CI: −50.52 to −15.75; P=0.0002; I2=96%), TG (12 treatment arms; WMD = −39.20 mg/dL; 95% CI: −52.71 to −25.69; P=0.0001; I2=73%), and vLDL-C (five treatment arms; WMD = −8.02 mg/dL; 95% CI: −8.77 to −7.26; P=0.0001; I2=0%). However, spirulina intervention may not significantly change the levels of HDL-C (11 treatment arms; WMD = 5.81 mg/dL; 95% CI: 0.10 to 11.51; P=0.05; I2=94%). Other markers of CVD risk are listed in Table 2. For the change of BP, consumption with spirulina showed a significant decrease in DBP (four treatment arms; WMD = −7.17 mmHg; 95% CI: −8.57 to −5.78; P=0.0001; I2=0%) but not SBP (four treatment arms; WMD = −3.49 mmHg; 95% CI: −7.19 to 0.21; P=0.06; I2=50%). Finally, spirulina consumption significantly lowered FBG (eight treatment arms; WMD = −5.01 mg/dL; 95% CI: −9.78 to −0.24; P=0.04; I2=77%). No significant changes were found for body weight (seven treatment arms; WMD = −1.51 kg; 95% CI: −3.39 to 0.36; P=0.11; I2=0%), BMI (five treatment arms; WMD = −0.44 (kg/m2); 95% CI: −1.87 to 0.99; P=0.54; I2=71%), and HbA1c (three treatment arms; WMD = −0.34; 95% CI: −0.79 to 0.11; P=0.14; I2=78%) following spirulina supplementation. The high levels of statistical heterogeneity were found in most of the analysis.

Figure 2.

Forest plot detailing weighted mean difference and 95% CIs for the effects of spirulina supplementation on TC (A), LDL-C (B), HDL-C (C), and TG (D) in humans.

Abbreviations: HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; TC, total cholesterol; WMD, weighted mean differences.

Table 2.

Effect of spirulina consumption on other markers of cardiovascular disease

| Markers outcomes | No. of treatment arms | No. of patients | WMD (95% CI) | P-value | I2, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| vLDL-C (mg/dL) | 5 | 167 | −8.02 (−8.77 to −7.26) | 0.0001* | 0 |

| FBG (mg/dL) | 8 | 411 | −5.01 (−9.78 to −0.24) | 0.04* | 51 |

| HbA1c | 3 | 82 | −0.34 (−0.79 to 0.11) | 0.14 | 78 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 4 | 141 | −3.49 (−7.19 to 0.21) | 0.06 | 50 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 4 | 141 | −7.17 (−8.57 to −5.78) | 0.0001* | 0 |

| Body weight (kg) | 7 | 276 | −1.51 (−3.39 to 0.36) | 0.11 | 0 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 5 | 354 | −0.44 (−1.87 to 0.99) | 0.54 | 71 |

Notes:

Indicates a significant result.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; vLDL-C, very-low-density cholesterol; WMD, weighted mean differences.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses were conducted to evaluate the overall effects of spirulina on plasma lipid concentrations in pre-specified subgroups, including types of controls used (no intervention or placebo), spirulina dose (<2 or ≥2 g/d), and intervention duration (<12 or ≥12 weeks). Subgroup analysis results based on the spirulina dose demonstrate that spirulina consumption significantly decreased the level of TC (WMD = −35.41 mg/dL; 95% CI: −51.43 to −19.39; P=0.0001), LDL-C (WMD = −37.62 mg/dL; 95% CI: −63.23 to −12.00; P=0.004), and TG (WMD = −41.65 mg/dL; 95% CI: −63.18 to −20.12; P=0.0001) in subjects with spirulina supplementation ≥2 g/d. The trials stratified by duration of intervention showed that subjects with spirulina intervention ≥12 weeks significantly reduced the concentrations of TC (WMD = −38.88 mg/dL; 95% CI: −56.05 to −21.72; P=0.0001), LDL-C (WMD = −35.06 mg/dL; 95% CI: −54.30 to −15.82; P=0.0004), and TG (WMD = −40.65 mg/dL; 95% CI: −55.82 to −25.49; P=0.0001) and increased HDL-C (WMD = 6.66 mg/dL; 95% CI: 0.22 to 13.11; P=0.04). In the subgroup analysis by types of control used, the pooled result showed that spirulina supplementation significantly decreased TC (WMD = −58.90 mg/dL; 95% CI: −82.53 to −35.28; P=0.0001), LDL-C (WMD = −54.38 mg/dL; 95% CI: −80.57 to −28.19; P=0.0001), and TG (WMD = −54.58 mg/dL; 95% CI: −70.22 to −38.94; P=0.0001) and increased HDL-C (WMD = 10.46 mg/dL; 95% CI: 1.73 to 19.19; P=0.02) in trials used no intervention as controls. Significant differences were found on TC concentrations in trials that used placebo as controls (WMD = −12.74 mg/dL; 95% CI: −21.89 to −3.59; P=0.006). Complete subgroup results of lipid changes are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses of TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, and TG stratified by previously defined study characteristics

| Variables | TC | LDL-C | HDL-C | TG | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arms | WMD (95% CI) | P | I2 (%) | Arms | WMD (95% CI) | P | I2 (%) | Arms | WMD (95% CI) | P | I2 (%) | Arms | WMD (95% CI) | P | I2 (%) | |

| Spirulina dose | ||||||||||||||||

| <2 g/d ≥2 g/d | 3 9 | −25.51 (−53.52 to 2.50) −35.41 (−51.43 to −19.39) | 0.07 0.0001* | 86 96 | 3 8 | −21.57 (−56.54 to 13.39) −37.62 (−63.23 to −12.00) | 0.23 0.004* | 93 95 | 3 8 | 2.39 (−4.86 to 9.65) 7.21 (−0.44 to 14.85) | 0.52 0.06 | 74 95 | 3 9 | −26.04 (−64.07 to 11.99) −41.65 (−63.18 to −20.12) | 0.18 0.0001* | 74 76 |

| Duration | ||||||||||||||||

| <12 weeks ≥12 weeks | 3 9 | −8.45 (−26.33 to 9.42) −38.88 (−56.05 to −21.72) | 0.35 0.0001* | 50 95 | 2 9 | −18.12 (−36.69 to 0.45) −35.06 (−54.30 to −15.82) | 0.06 0.0004* | 0 97 | 2 9 | 2.58 (−2.72 to 7.88) 6.66 (0.22 to 13.11) | 0.34 0.04* | 0 95 | 3 9 | −29.35 (−58.65 to −0.05) −40.65 (−55.82 to −25.49) | 0.05 0.0001* | 0 80 |

| Types of control used | ||||||||||||||||

| No intervention Placebo | 6 5 | −58.90 (−82.53 to −35.28) −12.74 (−21.89 to −3.59) | 0.0001* 0.006* | 97 0 | 6 5 | −54.38 (−80.57 to −28.19) −8.21 (−17.41 to 0.99) | 0.0001* 0.08 | 98 12 | 6 5 | 10.46 (1.73 to 19.19) 0.61 (−2.44 to 3.67) | 0.02* 0.69 | 97 0 | 6 5 | −54.58 (−70.22 to −38.94) −9.93 (−29.13 to 9.26) | 0.0001* 0.31 | 80 0 |

| Sensitivity analysis | ||||||||||||||||

| Removing the studies that used the soybean as control | 11 | −37.28 (−53.05 to −21.52) | 0.0001* | 94 | 11 | −33.16 (−50.52 to −15.79) | 0.0002* | 96 | 11 | 5.81 (0.10 to 11.51) | 0.05 | 94 | 11 | −40.80 (−54.74 to −26.86) | 0.0001* | 74 |

Note:

Indicates a significant result.

Abbreviations: HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; WMD, weighted mean differences.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to further confirm the robustness of the results. The pooled effects of spirulina on lipid profile did not change after systematically dropping each trial (Figure S2). Furthermore, we also omitted the studies that use soybean as a control. The aggregated results were also similar to the overall analysis (Table 3).

Adverse events

Among these trials, spirulina were well-tolerated. The adverse event rate was similar in the experimental and control groups, and no serious adverse events occurred among most of the eligible trials during the follow-up period.

Publication bias

No obvious publication bias was discerned in the visual inspection of funnel plots (Figure S3). Similarly, Begg’s rank correlation and Egger’s linear regression tests were also performed to confirm the publication bias. The results of Begg’s test and Egger’s test were listed in Table 4. These results did not show any evidence of publication bias in the present analysis (all P>0.05). We did not perform publication bias test for HbA1c, SBP, and DBP due to lack of sufficient studies (n<5).

Table 4.

Publication bias in the meta-analysis of studies

| Outcomes | Begg’s rank correlation test

|

Egger’s linear regression test

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z value | P-value | Intercept (95% CI) | t | df | P-value | |

|

| ||||||

| TC | 0.75 | 0.451 | −0.85 (−4.58 to 2.88) | −0.51 | 11 | 0.622 |

| LDL-C | 0.62 | 0.533 | −1.94 (−6.96 to 3.08) | −0.87 | 10 | 0.405 |

| HDL-C | 0.16 | 0.876 | 1.78 (−3.70 to 7.25) | 0.73 | 10 | 0.481 |

| TG | 1.17 | 0.244 | 0.37 (−1.29 to 2.03) | 0.50 | 11 | 0.628 |

| vLDL-C | 1.22 | 0.221 | 0.19 (−0.87 to 1.25) | 0.57 | 4 | 0.610 |

| FBG | 2.10 | 0.035 | −1.45 (−3.46 to 0.56) | −1.76 | 7 | 0.129 |

| Body weight | 1.36 | 0.174 | −0.97 (−3.13 to 1.20) | −1.09 | 7 | 0.316 |

| BMI | 0.19 | 0.851 | 0.40 (−6.91 to 7.71) | 0.15 | 5 | 0.886 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; df, degrees of freedom; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; vLDL-C, very-low-density cholesterol.

Discussion

CVD is the leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for about one in three deaths. To reduce the incidence of CVD, targeting metabolic risk factors by nontoxic antioxidant nutrient supplement or functional food with cardiovascular protective properties is of great importance. Their mechanism of action is based primarily on reducing oxidative stress, enhancing NO synthesis, reducing LDL oxidation, inhibiting the growth of smooth muscle cells of blood vessels, modulating insulin resistance, and reducing BP. In the current meta-analysis, we focused on the evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of spirulina supplementation on the major CVD risk markers, including lipid parameters, BP, body weight, and glucose. Results from our pooled analysis of 12 identified studies with 14 treatment arms demonstrate that patients receiving spirulina had statistically significant lower TC, LDL-C, TG, vLDL-C, FBG, and DBP after treatment than did control patients. However, the use of spirulina did not substantially affect HDL-C, SBP, HbA1c, body weight, and BMI values compared with those in the control group. These changes varied substantially depending on the types of controls used, spirulina dose, and intervention duration. In our subgroup analysis, the lipid-modifying effects of spirulina were also found in subjects that ingested a dose of spirulina >2 g/d and subjects with spirulina intervention ≥12 weeks. The pooled result was robust and remained significant in the leave-one-out sensitivity analysis. Spirulina consumption might be utilized as nutraceuticals or functional foods for the prevention and treatment of CVD in humans.

The results of our meta-analysis are remarkably similar to the study performed by Serban et al35 regarding TC, LDL-C, and TG, but in contrast to HDL-C. Previous study included seven trials with 522 participants for analysis and indicated that spirulina supplementation significantly lowered TC (P<0.001), LDL-C (P<0.001), and TG (P=0.001) and elevated those of HDL-C (P<0.001).35 For our present analysis, we included other five recent double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trials, giving greater power to evaluate these beneficial effect. Furthermore, other identified CVD risk markers, such as body weight, BMI, FBG, HbA1c, SBP, and DBP, were also systematically evaluated in our present analysis following spirulina consumptions, which had not been assessed in previous reviews. Our present analysis is the latest and the most comprehensive one and will provide clinicians with an unbiased consensus of the current human clinical trial data, which can be directly applied to practice while also highlighting directions for future clinical research.

Dyslipidemia, hypertension, and insulin resistance promote endothelial dysfunction and vascular inflammation leading to atherosclerosis.36 There is sufficient evidence showing that interventions with lipid-lowering therapies have the potential role in reducing the risk of atherosclerotic CVD.37,38 Antioxidants now play a significant role in preventing the accumulation of lipids in blood vessels by eliminating the lipid peroxides derived through lipid peroxidation and free radicals.39 According to the clinical practice guidelines, LDL-C is considered to be the main target for lipid-lowering treatment, with a 1% reduction associated with a 1% decrease in CVD events.40 The lipid-modifying effects of spirulina were established in our present meta-analysis, especially on TC, LDL-C, and TG. However, the precise mechanisms responsible for the presumed lipid-lowering properties of spirulina are not fully explored. It has been shown that the hypocholesterolemic action of spirulina platensis concentrate may involve the inhibition of both jejunal cholesterol absorption and ileal bile acid reabsorption, as well as increase fecal cholesterol and bile acid excretion.41,42 Moreover, the decrease in the lipid level can be also attributed to the spirulina antioxidant metabolites characteristic. C-phycocyanin, the main ingredient of spirulina, reduces the lipid concentrations through scavenging free radicals, inhibiting lipid peroxidation, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase expression, and increasing the activity of lipoprotein lipase, hepatic triglyceride lipase, glycosylated serum protein peroxidase and superoxide dismutase.43–45 The effects of spirulina administration on atherosclerosis are also revealed by in vivo study, in which spirulina has been shown to activate the atheroprotective heme oxygenase-1 in endothelial cells.46

Hypertension, hyperglycemia, and high level of HbA1c are regarded as key risk factors for the development of atherosclerotic CVD in humans.47 Therefore, assessment of glycemic and BP control is also a crucial element of effective primary and secondary CVD prevention. FBG levels are generally used to evaluate the efficacy of dietary supplements and glycemic-lowering drugs. Our pooled result revealed that FBG and DBP levels were significantly reduced following spirulina interventions. However, no significant change was found in HbA1c. Persistence of excess adiposity is associated with the progression of metabolic abnormality, whereas the control of weight gain may relieve the risk of these metabolic-related complications. Greater weight loss generates greater benefit in terms of meaningful reductions in serum lipids, BP, blood glucose, and the risk of developing metabolism syndrome.48 However, we failed to find any statistically significant differences in body weight between the spirulina products and the control groups. It should be noted that these results are inconclusive because the number of eligible clinical trial was relatively small; further, large-scale randomized controlled trials are required to confirm the present results.

Our findings may have major implications for clinical practice and further research, given that the metabolic biomarkers evaluated in our present study are clinically relevant for evaluating treatment and progression of CVD. However, our present meta-analysis is not without weaknesses. First, although extensive searches with clear inclusion criteria were formulated, we may not have entirely identified all relevant articles involving the use of spirulina especially unpublished trials and gray literature. Second, although no significant publication bias was detected in our study, we observed a high degree of heterogeneity between studies that was not completely resolved by numerous subgroup and sensitivity analyses. The sources of the heterogeneity are most probably ascribed by the differences in study design, target populations (ie, subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus, HIV-infected, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, and hyperlipidemic nephrotic syndrome), and characteristics (ie, age, sex, and baseline BMI). Third, there were variations in reporting quality of included studies. Most of the trials were characterized by insufficient information about the sequence generation, allocation concealment, and types of blinding. These factors may have a potential impact on the precision of the effect sizes. Finally, due to the lack of information in most of the existing studies, some other confounding factors were unable to be taken into consideration, such as physical activities and other dietary factors intervention.

Summary and conclusion

In summary, based on the currently available literature, our meta-analysis revealed a significant benefit of spirulina supplementation in improving multiple markers of cardiovascular health including TC, LDL-C, TG, vLDL-C, FBG, and DBP, without any significant side-effects. The pooled results indicate clinically important improvements in CVD risk profile. Spirulina consumption may be considered as an adjunct to the prevention and treatment of CVD in humans. Further larger high-quality, double-blind, randomized clinical trials investigating the long-term effects and risk of spirulina supplementation on cardiovascular metabolic biomarkers and cardiovascular morbidity are needed.

Supplementary materials

Quality assessment of the included studies. Labeling an item as a “question mark” indicated an unclear or unknown risk of bias; Labeling an item as a “negative sign” indicated a high risk of bias; Labeling an item as a “positive sign” indicated a low risk of bias.

Sensitivity analysis was conducted on outcomes of TC (A), LDL-C (B), HDL-C (C), and TG (D) using the leave-one-out method.

Abbreviations: HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

Funnel plots with pseudo 95% CIs for publication bias of TC (A), LDL-C (B), HDL-C (C), TG (D), vLDL-L (E), FBG (F), body weight (G), and BMI (H).

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; vLDL-C, very-low-density cholesterol.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Traditional Medicine Research Program of Guangdong Province (No. 20181270).

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- FBG

fasting blood glucose

- HbA1c

glycosylated hemoglobin

- HDL-C

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-C

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- TC

total cholesterol

- TG

triglycerides

- vLDL-C

very-low-density cholesterol

- WMDs

weighted mean differences

Footnotes

Author contributions

HH contributed to conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafted the manuscript, discussed the idea of the meta-analysis, and submitted the paper; DL and RP completed the database searches and selected, reviewed the articles, and extracted the data; YC contributed to conception and design of the study, reviewed and extracted the data, and performed the data analyses. All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Smith SC, Collins A, Ferrari R, et al. Our time: a call to save preventable death from cardiovascular disease (heart disease and stroke) Circulation. 2012;126(23):2769–2775. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318267e99f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364(9438):937–952. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banach M, Aronow WS. Hypertension therapy in the older adults-do we know the answers to all the questions? The status after publication of the ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly. J Hum Hypertens. 2012;26(11):641–643. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2012.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Writing Group Members. Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121(7):e46–e215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131(4):e29–322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R, Prospective Studies Collaboration Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360(9349):1903–1913. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2006;21(1):1–6. doi: 10.1097/01.hco.0000200416.65370.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang H, Chen G, Liao D, Zhu Y, Xue X. Effects of berries consumption on cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23625. doi: 10.1038/srep23625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang H, Zou Y, Chi H, Liao D. Lipid-modifying effects of chitosan supplementation in humans: a pooled analysis with trial sequential analysis. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2018;62(8):e1700842. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201700842. 1700842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang H, Chen G, Liao D, Zhu Y, Pu R, Xue X. The effects of resveratrol intervention on risk markers of cardiovascular health in overweight and obese subjects: a pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2016;17(12):1329–1340. doi: 10.1111/obr.12458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stepien M, Kujawska-Luczak M, Szulinska M, et al. Beneficial dose-independent influence of Camellia sinensis supplementation on lipid profile, glycemia, and insulin resistance in an NaCl-induced hypertensive rat model. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2018;69(2) doi: 10.26402/jpp.2018.2.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szulińska M, Stępień M, Kręgielska-Narożna M, et al. Effects of green tea supplementation on inflammation markers, antioxidant status and blood pressure in NaCl-induced hypertensive rat model. Food Nutr Res. 2017;61(1):1295525. doi: 10.1080/16546628.2017.1295525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazokopakis EE, Karefilakis CM, Tsartsalis AN, Milkas AN, Ganotakis ES. Acute rhabdomyolysis caused by Spirulina (Arthrospira platensis) Phytomedicine. 2008;15(6–7):525–527. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan Z, Bhadouria P, Bisen PS. Nutritional and therapeutic potential of Spirulina. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2005;6(5):373–379. doi: 10.2174/138920105774370607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng R, Chow TJ. Hypolipidemic, antioxidant, and antiinflammatory activities of microalgae Spirulina. Cardiovasc Ther. 2010;28(4):e33–e45. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2010.00200.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martínez-Galero E, Pérez-Pastén R, Perez-Juarez A, Fabila-Castillo L, Gutiérrez-Salmeán G, Chamorro G. Preclinical antitoxic properties of Spirulina (Arthrospira) Pharm Biol. 2016;54(8):1345–1353. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2015.1077464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gutiérrez-Salmeán G, Fabila-Castillo L, Chamorro-Cevallos G. Nutritional and toxicological aspects of Spirulina (Arthrospira) Nutr Hosp. 2015;32(1):34–40. doi: 10.3305/nh.2015.32.1.9001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karkos PD, Leong SC, Karkos CD, Sivaji N, Assimakopoulos DA. Spirulina in clinical practice: evidence-based human applications. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:1–4. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nen058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anitha L, Chandralekha K. Effect of supplementation of spirulina on blood glucose, glycosylated hemoglobin and lipid profile of male non-insulin dependent diabetics. Asian J Exp Biol Sci. 2010;1(1):36–46. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park HJ, Lee YJ, Ryu HK, Kim MH, Chung HW, Kim WY. A random-ized double-blind, placebo-controlled study to establish the effects of spirulina in elderly Koreans. Ann Nutr Metab. 2008;52(4):322–328. doi: 10.1159/000151486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramamoorthy A, Premakumari S. Effect of supplementation of Spirulina on hypercholesterolemic patients. J Food Sci Technol. 1996;33(2):124–128. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samuels R, Mani UV, Iyer UM, Nayak US. Hypocholesterolemic effect of spirulina in patients with hyperlipidemic nephrotic syndrome. J Med Food. 2002;5(2):91–96. doi: 10.1089/109662002760178177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szulinska M, Gibas-Dorna M, Miller-Kasprzak E, et al. Spirulina maxima improves insulin sensitivity, lipid profile, and total antioxidant status in obese patients with well-treated hypertension: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017;21(10):2473–2481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):W–94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. [Accessed October 25, 2018]. (updated March 2011) Available from: http://handbook.cochrane.org/

- 26.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen GS, Drapeau C, Lenninger M, Benson KF. Clinical safety of a high dose of phycocyanin-enriched aqueous extract from Arthrospira (Spirulina) platensis: results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with a focus on anticoagulant activity and platelet activation. J Med Food. 2016;19(7):645–653. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2015.0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee EH, Park JE, Choi YJ, Huh KB, Kim WY. A randomized study to establish the effects of spirulina in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Nutr Res Pract. 2008;2(4):295–300. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2008.2.4.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marcel AK, Ekali LG, Eugene S, et al. The effect of Spirulina platensis versus soybean on insulin resistance in HIV-infected patients: a randomized pilot study. Nutrients. 2011;3(7):712–724. doi: 10.3390/nu3070712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miczke A, Szulińska M, Hansdorfer-Korzon R, et al. Effects of spirulina consumption on body weight, blood pressure, and endothelial function in overweight hypertensive Caucasians: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20(1):150–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ngo-Matip ME, Pieme CA, Azabji-Kenfack M, et al. Effects of Spirulina platensis supplementation on lipid profile in HIV-infected antiretroviral naïve patients in Yaounde-Cameroon: a randomized trial study. Lipids Health Dis. 2014;13:191. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-13-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parikh P, Mani U, Iyer U. Role of spirulina in the control of glycemia and lipidemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Med Food. 2001;4(4):193–199. doi: 10.1089/10966200152744463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeinalian R, Farhangi MA, Shariat A, Saghafi-Asl M. The effects of Spirulina Platensis on anthropometric indices, appetite, lipid profile and serum vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in obese individuals: a randomized double blinded placebo controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(1):225. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1670-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Serban MC, Sahebkar A, Dragan S, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of Spirulina supplementation on plasma lipid concentrations. Clin Nutr. 2016;35(4):842–851. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Srikanth S, Deedwania P. Management of dyslipidemia in patients with hypertension, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2016;18(10):76. doi: 10.1007/s11906-016-0683-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barter PJ, Rye KA. New era of lipid-lowering drugs. Pharmacol Rev. 2016;68(2):458–475. doi: 10.1124/pr.115.012203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366(9493):1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kata FS, Athbi AM, Manwar EQ, Al-Ashoor A, Abdel-Daim MM, Aleya L. Therapeutic effect of the alkaloid extract of the cyanobacterium Spirulina platensis on the lipid profile of hypercholesterolemic male rabbits. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2018:19635–19642. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-2170-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russell C, Sheth S, Jacoby D. A clinical guide to combination lipid-lowering therapy. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2018;20(4):19. doi: 10.1007/s11883-018-0721-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagaoka S, Shimizu K, Kaneko H, et al. A novel protein C-phycocyanin plays a crucial role in the hypocholesterolemic action of Spirulina platensis concentrate in rats. J Nutr. 2005;135(10):2425–2430. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.10.2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kulshreshtha A, Zacharia AJ, Jarouliya U, Bhadauriya P, Prasad GB, Bisen PS. Spirulina in health care management. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2008;9(5):400–405. doi: 10.2174/138920108785915111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Upasani CD, Balaraman R. Protective effect of Spirulina on lead induced deleterious changes in the lipid peroxidation and endogenous antioxidants in rats. Phytother Res. 2003;17(4):330–334. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han LK, Li DX, Xiang L, et al. Isolation of pancreatic lipase activity-inhibitory component of spirulina platensis and it reduce postprandial triacylglycerolemia. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2006;126(1):43–49. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.126.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ku CS, Yang Y, Park Y, Lee J. Health benefits of blue-green algae: prevention of cardiovascular disease and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Med Food. 2013;16(2):103–111. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2012.2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strasky Z, Zemankova L, Nemeckova I, et al. Spirulina platensis and phycocyanobilin activate atheroprotective heme oxygenase-1: a possible implication for atherogenesis. Food Funct. 2013;4(11):1586–1594. doi: 10.1039/c3fo60230c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Retnakaran R, Cull CA, Thorne KI, Adler AI, Holman RR, UKPDS Study Group Risk factors for renal dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study 74. Diabetes. 2006;55(6):1832–1839. doi: 10.2337/db05-1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wenger NK. Prevention of cardiovascular disease: highlights for the clinician of the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines. Clin Cardiol. 2014;37(4):239–251. doi: 10.1002/clc.22264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Quality assessment of the included studies. Labeling an item as a “question mark” indicated an unclear or unknown risk of bias; Labeling an item as a “negative sign” indicated a high risk of bias; Labeling an item as a “positive sign” indicated a low risk of bias.

Sensitivity analysis was conducted on outcomes of TC (A), LDL-C (B), HDL-C (C), and TG (D) using the leave-one-out method.

Abbreviations: HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

Funnel plots with pseudo 95% CIs for publication bias of TC (A), LDL-C (B), HDL-C (C), TG (D), vLDL-L (E), FBG (F), body weight (G), and BMI (H).

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; vLDL-C, very-low-density cholesterol.