Abstract

There is an urgent need to depart from in-service training that relies on distance and/or intensive off-site training leading to limited staff coverage at clinical sites. This traditional approach fails to meet the challenge of improving clinical practice, especially in low-income and middle-income countries where resources are limited and disease burden high. South Africa’s University of Cape Town Lung Institute Knowledge Translation Unit has developed a facility-based training strategy for implementation of its Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) primary care programme. The training has been taken to scale in primary care facilities throughout South Africa and has shown improvements in quality of care indicators and health outcomes along with end-user satisfaction. PACK training uses a unique approach to address the needs of frontline health workers and the health system by embedding a health intervention into everyday clinical practice at facility level. This paper describes the features of the PACK training strategy: PACK training is scaled up using a cascade model of training using educational outreach to deliver PACK to clinical teams in their health facilities in short, regular sessions. Drawing on adult education principles, PACK training empowers clinicians by using experiential and interactive learning methodologies to draw on existing clinical knowledge and experience. Learning is alternated with practice to improve the likelihood of embedding the programme into everyday clinical care delivery.

Keywords: health systems, health policy, public health

Summary box.

Combining appropriate training of primary care health workers with effective interventions has the potential to produce high quality care and good health outcomes at primary care, however, scale up is rarely sustained in lower middle-income countries where it is needed the most.

The Knowledge Translation Unit has developed and implemented a training programme that is an effective health systems intervention that can be scaled up and sustained to support frontline primary care health workers.

Primary care requires a training programme that responds to the health systems needs of everyday clinical practice, targets health workers in their teams where they work, alongside ongoing policy updates and programme revision.

Implementing a training programme in a primary health care system is challenging

There have been many innovative attempts in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) to strengthen primary healthcare since its global adoption in 1978.1 Some have been successful, like the WHO strategy of Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses (IMCI) and the Millennium Development Goals 2015.1 2 However, many primary care initiatives fail to be implemented beyond pilot phase, and those that are implemented are rarely scaled up and sustained.3

The reasons for this failure in LMICs are multiple and complex but include health worker shortages, high disease burden and overwhelmed health systems. And of the dedicated health workers who remain working in primary care health facilities, many lack the knowledge, skills and resources to fulfil the role expected of them by their managers and patients alike.4

A large focus of primary care strengthening and scale up initiatives is on the provision of health worker training.5 This usually takes the form of off-site bursts of intensive training or distance education with limited staff coverage at facility level and within facilities.6 These intensive sessions often require health workers to be away from their facilities, placing additional strain on services in their absence.6 The traditional educational approach to training health workers in LMICs tends to be a didactic one, despite evidence to show that it has little effect on improving clinical practice.7 8 In addition, there is a dearth of published data about effective approaches to in-service training in LMICs.9

Although some interventions in LMICs, like IMCI, have shown improvements in quality of care, scale up has been constrained by the assumption that training will diffuse through the system—that those health workers selected for training will have the skills and time to communicate their new knowledge to their colleagues.10–12

The Practical Approach to Care Kit

The Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) programme is a health systems intervention that has successfully been implemented, scaled up and sustained. Developed by the Knowledge Translation Unit (KTU) in South Africa over 18 years, it has been adopted as policy by the country’s department of health to strengthen primary care initiatives such a Nurse-Initiated and Managed Antiretroviral Therapy and the Ideal Clinic.13 14 Between 2007 and 2017, it was scaled up to over 3500 primary care facilities across South Africa, reaching over 30 000 primary care health workers across the country. Pragmatic controlled trials of the intervention have shown modest but consistent improvements across a range of health outcomes and quality of care indicators, particularly for communicable diseases, tuberculosis (TB) case detection of TB and HIV testing rates. There were also noticeable shifts in healthcare utilisation, with reductions in the duration of hospital admissions.15–19 Concurrent qualitative work demonstrated better health worker job satisfaction with health workers feeling more empowered to cope with on-the-ground primary care realities.20 21 The programme has since been localised to other LMIC settings including Brazil, Nigeria and Ethiopia.22–25

Designed to support health workers to deliver policy-aligned, comprehensive and integrated primary care, the PACK programme comprises four pillars—the provision of clinical decision support in the form of the PACK Adult guide,26 a training programme, and health systems improvement and monitoring and evaluation components.

This paper focuses on the second pillar, the training programme, and describes the three key elements that have allowed KTU to take the PACK programme to scale in a way that has both improved care and been sustained: educational outreach training, a cascade model of implementation and support and a training methodology which is underpinned by adult education principles.

Educational outreach training

Educational outreach is a strategy shown to be effective in changing health worker behaviour and practice, particularly prescribing.27 LMIC-setting primary care studies of educational outreach have demonstrated improvements across a range of morbidities including childhood infections and asthma.28 29

The PACK educational outreach training comprises regular (every 1 to 2 weeks), short (1 to 2 hours) sessions that occur onsite and in-service at the primary care facility. The sessions are incorporated into the working day and as they are onsite, allow for alternation of learning with practice. Being onsite also limits disruption of clinical services while learning continues at the facility.

The training takes a team approach, drawing in all cadres of health worker (including nurses, doctors, pharmacists, community health workers (CHW), lay counsellors) working across programmes within a facility, which can increase within-facility coverage and creates opportunities to discuss role clarification (eg, the clinical mentorship provided by the doctor, the role of the CHW in providing adherence support) and coordination of care. The sessions are led by health workers who are capacitated to function as Facility Trainers, described below.

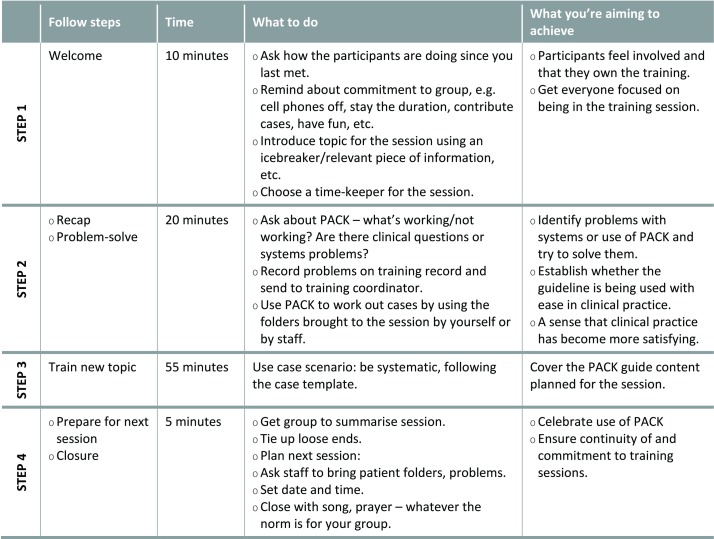

The core aim of the training is to ensure that health workers mainly doctors and nurses understand how to use the PACK guide and become accustomed to referring to it in their everyday clinical practice and communication. However, it also provides the opportunity for other cadre of staff to participate in the training to identify and address as a team health systems issues raised by using the PACK guide, including patient flow in the facility, referral pathways or medication supply. Health systems strengthening is integrated and embedded in the content of the training, offering multiple opportunities for discussions on facility-level health systems strengthening. Each onsite session follows a four-step format that provides structure to the 1 to 2-hour session and ensures that the priorities for the session are met. This repeated weekly onsite format allows for the consolidation of new learning and integration with practice. Figure 1 depicts the onsite session structure, taken from the PACK Facility Trainer’s training manual. The onsite sessions make use of a variety of training materials, itemised in table 1. These include the PACK guide, a board game, a waiting room scene, case scenarios, explainer videos, infographics and training records.

Figure 1.

Practical Approach to Care kit (PACK) onsite training session four-step format.

Table 1.

Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) training materials

| Training material |

Description | Purpose | When it is used |

Used by whom |

| PACK Adult guide http://pack.bmj.com/ |

A comprehensive, evidence-informed, clinical decision support tool for adult primary care, that is localised to local policies and protocols. | To support health workers to deliver comprehensive, integrated, policy aligned care in each consultation | In all PACK training sessions | Health workers, PACK Facility and Master Trainers |

| PACK Board game and answer sheet |

A board game for 2-6 players where players take turns to look in the PACK guide for answers to questions posed on the board. | To introduce the scope and value of PACK in an interactive, funway, it prompts participants to explore the features and clinical content of the guide, (particularly priority conditions) as well as health systems issues. | Training sessions Stake holder meetings |

PACK Facility Trainers, Master Trainers and presenters of the PACK programme |

| PACK guide infographic | This one-pager outlines the content and features of the PACK guide. | To use as a talk tool to summarise the PACK guide features in a standardised way. | Introductory training sessions | PACK Facility Trainers and Master Trainers |

| PACK programme infographic |

A one-page infographic which outlines the four pillars of the PACK programme | Touse as a talk tool to summarise the four pillars of the PACK programme |

Introductory training sessions | PACK Facility Trainers and Master Trainers |

| Waiting room scene |

An illustration of a waiting room of patients with each depicting a clinical case scenario. The scene is familiar to participants with respect to its busyness and demography. | This serves as the curriculum for the training. Participants relate to the people in it as local patients with a real-life story to tell. It also prompts discussion of their own waiting room experiences as health workers. | To introduce the clinical component of the training and to introduce each case scenario | PACK Facility Trainers and Master Trainers |

| Case scenarios | These are clinical scenarios or stories linked to the people in the waiting room scene. | To guide participants to navigate specific content and features of the PACK guide. | The case scenarios are used in all onsite training sessions | PACK Facility Trainers and Master Trainers |

| Case template | This is a standardised format for the delivery of each case scenario. It supports the trainer to provide clinical details of the case only when prompted to do so by participants’ use of the PACK guide. | Serves as a script to train a case scenario so that the primary focus is the use and features of the PACK guide rather than the clinical detail of the case. | The case template is used to structure all case scenario trainingsessions and can serve as a script for discussions about health workers’ own patients. | PACK Facility Trainers and Master Trainers |

| Training Video https://youtu.be/b1fgr7pCYJA |

This demonstrates an onsite training session. | To showcase the PACK training approach, highlighting the four-step approach to delivering an onsite session and onsite training, facilitation skills and the PACK training principles. | Training sessions Stakeholder meetings |

PACK Facility Trainers and Master Trainers and presenters of the PACK programme |

| PACK guide video https://youtu.be/ZDSpbqQOmoU |

An explanation of the development of the PACK guide and its features | To demonstrate and explain the use and features of the PACK guide, to ensure that the key aspects of the guide are conveyed by trainers in a standardised way | Training sessions Stake holder meetings |

PACK Facility Trainers, Master Trainers and presenters of the PACK programme |

| PACK programme overview video | The PACK overview video shows a case study of the implementation of the PACK programme in the Western Cape province, South Africa. | To give insight into the PACK programme and how it is implemented and allow the voices of end-users to be heard. | Training sessions Stake holder meetings |

PACK Master Trainers and presenters of the PACK programme |

| Training records | Onsite training record Participant training record of cases covered. |

The PACK training records are used as attendance records, to monitor training activities, compile training reports and for the issuing of certificates. | Onsite sessions | Facility Trainers and Participants |

| Facility Trainers’ Manual |

This describes the PACK training methodology, onsite session structure and programme administrative processes. | To provide step-by-step instructions for being a PACK Facility Trainer |

Given out during the Facility Trainers’ Workshop, to be used to facilitate onsite training sessions | PACK Facility Trainers |

| Master Trainers’ Manual |

This provides a step-by-step guide on how to deliver the Facility Trainers’ workshop. | This manual supports the Master Trainers to prepare and conduct a Facility Trainers’ workshop. | Given out during the Master Trainers workshop, to be used to run a Facility Trainers’ workshop | PACK Master Trainers |

Implementing the programme in the health system

The implementation strategy used by the PACK programme aims to embed it into the health system so that it is sustainable and ultimately becomes a continuous programme that can outlive funding cycles and federal-level or state-level changes in senior management and priorities.

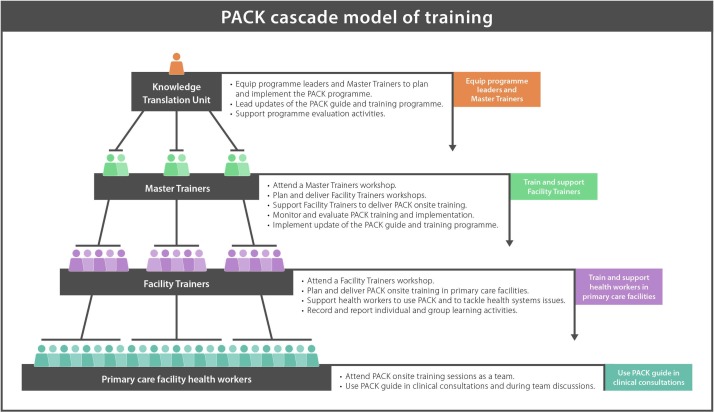

Thus, PACK uses a cascade model of training that capacitates government employed Master Trainers to train Facility Trainers who deliver onsite, in-service training to all health workers in all primary care facilities in the health system. Both levels of trainer then provide ongoing support to those they have trained to ensure the programme’s endurance in the system. See figure 2.

Figure 2.

The cascade model of Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) training.

In this way, since 2007 the KTU trained 74 Master Trainers across South Africa who equipped 1430 Facility Trainers to deliver educational outreach sessions onsite in over 3500 primary care facilities, reaching over 30 000 health workers. Over 260 000 copies of the guide have been distributed over a 10-year period through this model, with each health worker receiving a guide during initial training and then the next edition during annual update training. This reflects the scalability of the training programme and its continuity. As the KTU localises the PACK programme for other LMIC settings, the cascade model of training is proving a flexible one that can respond to local health system structures and resourcing and has required the KTU to capacitate an in-country team to drive the programme and train Master Trainers.

PACK trainers are usually facility-based health workers selected from the local health system by the health department and local regional training centre. They are often assigned to deliver PACK training sessions to the teams in their own primary care facilities. Selection criteria stipulate that they need to be clinically experienced, willing to take on the role and supported to do so by their managers, but do not include having training or teaching know-how. Those Facility Trainers who thrive in the role may be selected to be further trained as Master Trainers.

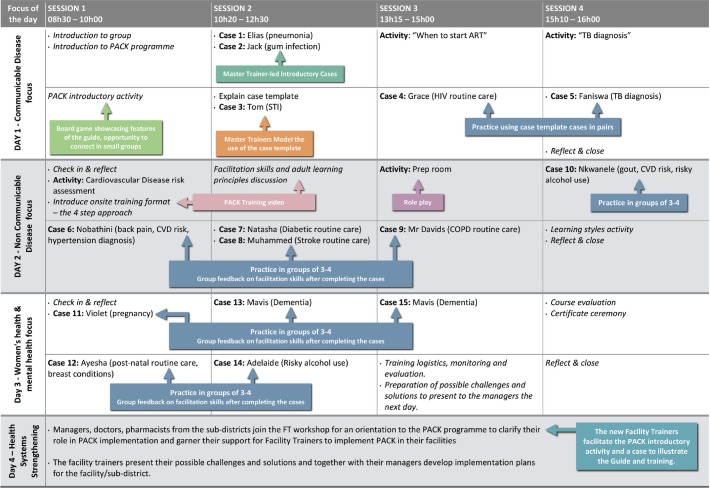

Master Trainers deliver the training of Facility Trainers during an intensive 4-day workshop off-site, away from home, work and other distractions. During the workshop, participants receive an overview of the PACK programme, its purpose and how it fits into the local health system. They are introduced to the PACK guide and its features as well as to the training materials. They are then given multiple opportunities to practise preparing and delivering a four-step onsite training session, initially in pairs one-on-one and then building up to training a small group. During the workshop, all key priority health conditions are covered to allow trainers to become familiar with, but not necessarily expert in, the guide’s clinical content. The workshop does not focus only on clinical knowledge and skills, but places also an emphasis on the process of training that is modelled by the Master Trainer and woven into the approach to delivering the onsite training session. This is described in figure 3 and in more detail in the next section. In view of the challenges of providing onsite sessions, every effort is made to release Facility Trainers to conduct onsite sessions. Facility managers attend the last day of the workshop to clarify their role in PACK implementation and garner their support for Facility Trainers to implement PACK in their facilities. On this day, managers also endorse and mandate Facility Trainers to provide onsite trainings.

Figure 3.

Summary programme of Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) Facility Trainers (FT) workshop. TB, tuberculosis; ART, antiretroviral therapy; CVD, cardiovascular disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; STI, sexuallly transmitted infection.

Key to the success of the cascade model of PACK training is the ongoing support the Master Trainers provide following the Facility Trainers’ workshop. The Master Trainer establishes an ongoing supportive relationship with the Facility Trainer. This includes coordinating district-level stakeholder engagement workshops and supporting Facility Trainers at management meetings. The Master Trainers maintain contact with the Facility Trainers during quarterly meetings and regular (weekly to monthly) telephone contact or WhatsApp text messaging. This provides a forum to share PACK training and clinical practice success stories, troubleshoot hurdles to delivery, develop training skills, provide content and policy updates, and most importantly nurture relationships between Facility Trainers, creating a supportive community of practice. This ongoing engagement is what particularly distinguishes PACK as a training programme rather than a once-off training course.

This supportive ethos filters down to facility level with Facility Trainers continuing to encourage facility health workers to use the PACK guide in their clinical practice and tackle the facility-level systems issues that the training exposes. They also provide refresher training with annual updates of the PACK guide or to those who require additional input.

PACK educational approach

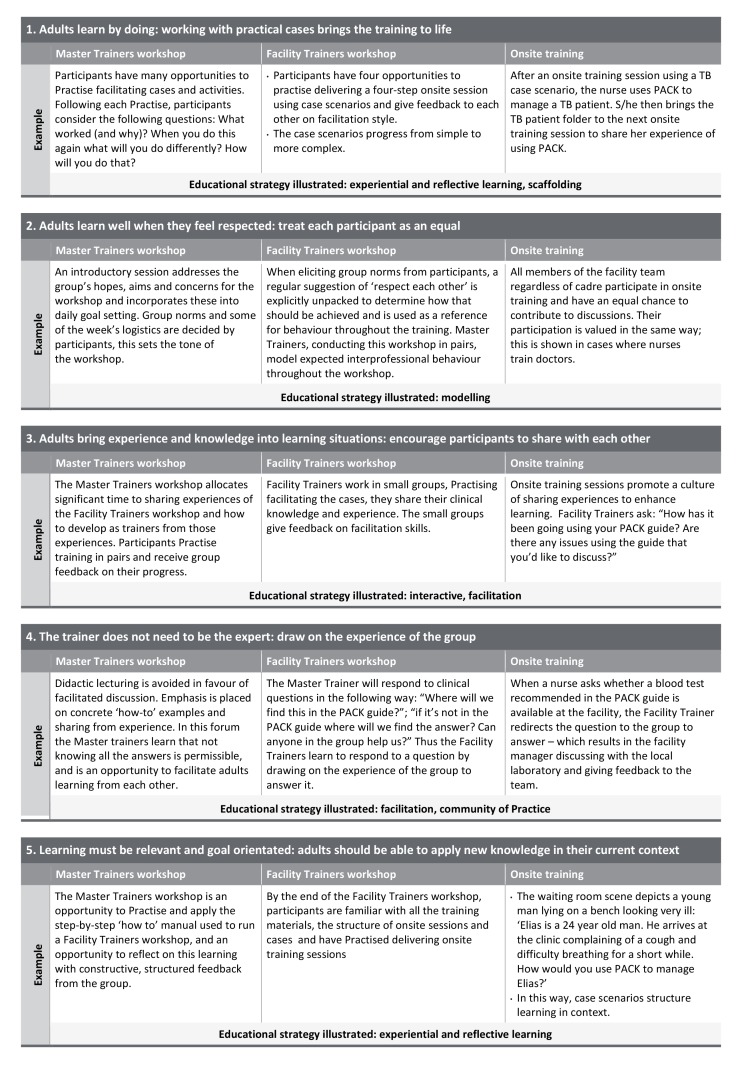

The 18-year development of the PACK educational approach has been an iterative one that has drawn from the experience of applying theories of adult learning and teaching.30 31 During this process, KTU derived five principles to guide the training process within each layer of the training cascade:

Adults learn by doing: working with practical cases brings the training to life.

Adults learn well when they feel respected: treat each participant as an equal.

Adults bring experience and knowledge into learning situations: encourage participants to share with each other.

The facilitator does not need to be the clinical expert: draw on the experience of the group.

Learning must be relevant and goal orientated: adults should be able to apply new knowledge in their current context.

PACK trainers use a combination of educational strategies to apply these principles. These strategies are embedded in the training material and programme design (an examples are provided in figure 4 and in the training video).

Figure 4.

Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) educational approach illustrations.

The training aims to encourage participants to actively engage as a team with the PACK guide, consider how its recommendations apply to their own context and embed it in their everyday practice. As PACK training is not a once-off interaction, and requires a long-term commitment as the PACK guide is updated regularly, the intention is to develop a community of practice32 within each facility and within groups of Facility Trainers and Master Trainers. As learning theories suggest that people do not learn in isolation but are strongly influenced by social interactions in meaningful contexts, PACK training occurs in small groups and is interactive in nature.33–35

The training tries to create a safe, non-threatening environment for learning. It does so in several ways. Case scenarios, facilitated by the Facility Trainer, are carefully designed to support the participant’s ability to gradually build on their knowledge and experience and incorporate new information—a process known as scaffolding.36 Scaffolding provides an overall structure for the training through incremental exposure to materials and piecemeal exposure to the full content of the guideline through the case scenarios.

The experiential nature of the regular onsite sessions introduces the new and updated information in bite-size chunks, this ensures the building of information is steady, giving clinicians time to digest, reflect, use/apply and embed the information between each training session.36 37 Reflective practice, or examining actions and their consequences, is used because each activity is regarded as a concrete learning event, and participants are required to provide constructive feedback about content in order to learn through and from each other.38 39

Didactic delivery of content is minimal if not avoided as much as possible during any of the training levels (master training, facility training or onsite training) due to its limited impact.9 Instead, the trainers use facilitations skills, and modelling to deliver the content by following the step-by-step manuals and cases in which all the educational strategies are embedded.31 40 41

When facilitation skills are used together with the training materials, they equip trainers to deliver the training without lecturing. Respect across professional boundaries (doctor/ nurse clinician/ manager) is also modelled, by recognising experience and acknowledging the value of each team member’s perspective. This creates a safe, non-judgemental environment where every participant has equal value regardless of title or rank and equips the group to adopt the same attitude when they communicate around the PACK programme. In these ways, modelling is a key strategy in setting a consistent example of the PACK approach to learning, the approach to using the guide and the approach to interacting with each other.

Challenges and learnings

The PACK training programme aims to embed a health system intervention into everyday clinical practice. Achieving this within a complex public health system is a challenging task. This section briefly describes some of the challenges and learnings that have occurred.

Positioning a comprehensive, multidisciplinary programme in the health system

As the PACK approach to content and training is a comprehensive and multidisciplinary one, the programme falls within the jurisdiction of several government health system programmes (eg, HIV and TB or sexual and reproductive health programmes, nursing department), this often means there is not one department taking responsibility to provide funding and ensure its effective implementation.

After being situated in government disease-based programmes for several years, the PACK programme finally found a home at both state and federal level in government human resources departments in South Africa and now primary care directorates in Nigeria, they are better equipped to implement and reinforce a comprehensive and integrated programme that cuts across disease boundaries and cadres of health worker.23 42

Supporting Facility Trainers in their role

PACK training has faltered when the Facility Trainer lacks the authority and support to deliver onsite training sessions. This occurs often if the trainer has been inappropriately selected, is regarded as junior to his/her colleagues, or if s/he is not released by local management to do so.11 The latter may occur when managers do not appreciate the fact that PACK training does not take a traditional off-site approach but rather provides an opportunity for within-facility system strengthening and team building.

In facilities where management gives priority to the PACK programme, implementation is most successful. This has prompted the design of a district implementation workshop for district-level role players and managers to learn about the PACK programme, participate in training and implementation planning, agree on local Facility Trainer selection and commit to supporting the roll out of the programme.

Tackling training over load in the health system

In South Africa, primary care health workers are often required to attend other in-service training activities to keep abreast of clinical policy updates and the roll out of other often vertical health programmes. Training schedules are not always well coordinated, resulting in health worker absence from a facility for long periods. This causes a disruption of health services and can delay PACK onsite sessions.

In South Africa’s Western Cape Province for example, the provincial regional training centre has used PACK as an entry for many other training activities, drawing on both the training model and clinical content and skills of the comprehensive PACK programme. This has helped to streamline both training content and activities and led to fewer health worker training commitments and less disruption to services.

Addressing per diem expectations—shifting the ‘education as extra’ mind set

In many LMICs, donor-funded remuneration of in-service training has helped to develop a culture among health workers to expect additional remuneration to attend off-site training.43 44 In some countries, the PACK Facility Trainers’ workshop was interrupted by negotiations with Master Trainers around compensation for attendance. The local training remuneration culture frames how this is addressed.

In addition, PACK Facility Trainers have at times regarded the responsibility of training colleagues as an addition to their workload and one that is separate from their daily clinical and managerial duties. This view has at times perpetuated a lack of commitment to ongoing PACK training at facility level.44 The PACK training model does not advise remuneration of Facility Trainers as they are already employed by the health system and being a facility-based PACK trainer forms part of their work responsibilities. By embedding the programme into every day, facility-based healthcare delivery, the PACK training programme aims to create an all-learning culture in health facilities where education is no longer an “optional extra” but rather viewed as part of daily clinical practice to improve quality of care and promote personal professional growth and interprofessional collaboration.

Making PACK training more accessible

Some primary care health facilities are too remote to access regularly, and Facility Trainers may not have the capacity to deliver onsite training sessions as intended. As a result, the KTU have embarked on the development of onscreen case scenarios and explainer training videos that maintain PACK educational principles to facilitate self-directed learning for both trainer and health worker.

Conclusion

Over the past 18 years, the KTU has created an effective health systems intervention that has been implemented, scaled up and sustained. This has required an evolution away from short-term training courses to a programmatic approach to improving the delivery of primary care. The PACK training strategy has been carefully refined to embed the programme into everyday clinical practice. We consider it a unique and innovative programme, significantly different to other current offerings in South Africa and other LMICs. Key differences are the facility-based onsite sessions which alternate learning and practice, an educational approach that is relational, long term and targets health workers in their teams where they work, alongside ongoing policy updates and programme revision. It also recognises the fact that training is not only an opportunity to pass on knowledge but can facilitate health system improvement. This work has brought many challenges which continue to be addressed to ensure improvement and sustainability of the programme. The localisation of PACK to other LMIC settings suggests that the PACK training strategy is transferable. It could well provide a model for the implementation of other LMIC health system interventions.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the nurses, doctors, managers, allied health professionals, policy makers and end-users and colleagues who gave inputs into the development and refinement of the PACK programme over the past 18 years in South Africa and the countries in which PACK has been localised. We thank the health workers and managers of the South African National Department of Health, and more specifically, the Western Cape Department of Health, whose implementation of the programme has helped to refine and scale it up. We acknowledge Izak Vollgraaff for the artwork in the guide and training materials, and Pearl Spiller as the graphic designer who consolidates the art work. We acknowledge all our KTU colleagues, past and present, for their contributions to the programme particularly the KTU Content Team who have driven the development and updating of the PACK guide in South Africa and globally and supported the updating of training materials.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: GF, DGP, LA, CJR, MLS: are the members of the KTU training team that developed and maintain the PACK training materials and methodology. RC: head of the content team, provided full editorial support to the paper. LF: with support from the KTU leadership team, conceptualised the PACK approach. MLS: wrote the first draft of the paper. MP: provided mentorship support. All authors contributed intellectual content, edited the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Funding: The development of the KTU training programme resulting in the PACK programme was funded by the University of Cape Town Lung Institute and the Chronic Disease Initiative in Africa (CDIA) through an award from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute for Global Health Activities in Developing Countries to Combat Non- Communicable Chronic Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Diseases. PACK receives no funding from the pharmaceutical industry.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare that RC, DGP, LA, CJR, MLS and LF are employees of the KTU. GF is an ex-employee of the KTU. MP is an employee of the University of Cape Town. Since August 2015, the KTU and BMJ have been engaged in a non-profit strategic partnership to provide continuous evidence updates for PACK, expand PACK-related supported services to countries and organisations as requested, and where appropriate license PACK content. The KTU and BMJ co-fund core positions, including a PACK Global Development Director, and receive no profits from the partnership. PACK receives no funding from the pharmaceutical industry. This paper forms part of a Collection on PACK sponsored by the BMJ to profile the contribution of PACK across several countries towards the realisation of comprehensive primary health care as envisaged in the Declaration of Alma Ata, during its 40th anniversary.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Kruk ME, Porignon D, Rockers PC, et al. The contribution of primary care to health and health systems in low- and middle-income countries: a critical review of major primary care initiatives. Soc Sci Med 2010;70:904–11. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boschi-Pinto C, Labadie G, Dilip TR, et al. Global implementation survey of Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI): 20 years on. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019079 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wiltsey Stirman S, Kimberly J, Cook N, et al. The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implement Sci 2012;7:17 10.1186/1748-5908-7-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Van Damme W, Kober K, Kegels G. Scaling-up antiretroviral treatment in Southern African countries with human resource shortage: how will health systems adapt? Soc Sci Med 2008;66:2108–21. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Couper I, Ray S, Blaauw D, et al. Curriculum and training needs of mid-level health workers in Africa: a situational review from Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:553 10.1186/s12913-018-3362-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mbonye MK, Burnett S, Naikoba S. Comparing the effect of educational outreach on infectious diseases management by mid-level health providers with and without prior core course: a cluster randomized trial in Uganda. Tropical medicine & international health 2015;20:345–45. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Forsetlund L, Bjørndal A, Rashidian A, et al. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;20 10.1002/14651858.CD003030.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lyon AR, Stirman SW, Kerns SE, et al. Developing the mental health workforce: review and application of training approaches from multiple disciplines. Adm Policy Ment Health 2011;38:238–53. 10.1007/s10488-010-0331-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bluestone J, Johnson P, Fullerton J, et al. Effective in-service training design and delivery: evidence from an integrative literature review. Hum Resour Health 2013;11:51 10.1186/1478-4491-11-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hall J, Cohen DJ, Davis M, et al. Preparing the workforce for behavioral health and primary care integration. J Am Board Fam Med 2015;28:S41–51. 10.3122/jabfm.2015.S1.150054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. O'Malley G, Perdue T, Petracca F. A framework for outcome-level evaluation of in-service training of health care workers. Hum Resour Health 2013;11:50 10.1186/1478-4491-11-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee Transforming and scaling up health professionals' education and training: world health organization guidelines 2013. Geneva: World Health Organization Copyright, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Visser CA, Wolvaardt JE, Cameron D, et al. Clinical mentoring to improve quality of care provided at three NIM-ART facilities: a mixed methods study. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2018;10:e1–e7. 10.4102/phcfm.v10i1.1579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. National Department of Health Integrated clinical services management manual. Pretoria, South Africa: National Department of Health, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fairall LR, Zwarenstein M, Bateman ED, et al. Effect of educational outreach to nurses on tuberculosis case detection and primary care of respiratory illness: pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2005;331:750–4. 10.1136/bmj.331.7519.750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zwarenstein M, Fairall LR, Lombard C, et al. Outreach education for integration of HIV/AIDS care, antiretroviral treatment, and tuberculosis care in primary care clinics in South Africa: PALSA PLUS pragmatic cluster randomised trial. BMJ 2011;342:d2022 10.1136/bmj.d2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fairall L, Bachmann MO, Lombard C, et al. Task shifting of antiretroviral treatment from doctors to primary-care nurses in South Africa (STRETCH): a pragmatic, parallel, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2012;380:889–98. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60730-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fairall LR, Folb N, Timmerman V, et al. Educational outreach with an integrated clinical tool for nurse-led non-communicable chronic disease management in primary care in South Africa: a pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002178 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fairall L, Bachmann MO, Zwarenstein M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of educational outreach to primary care nurses to increase tuberculosis case detection and improve respiratory care: economic evaluation alongside a randomised trial. Trop Med Int Health 2010;15:277–86. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Georgeu D, Colvin CJ, Lewin S, et al. Implementing nurse-initiated and managed antiretroviral treatment (NIMART) in South Africa: a qualitative process evaluation of the STRETCH trial. Implement Sci 2012;7:66 10.1186/1748-5908-7-66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stein J, Lewin S, Fairall L, et al. Building capacity for antiretroviral delivery in South Africa: a qualitative evaluation of the PALSA PLUS nurse training programme. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:240 10.1186/1472-6963-8-240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wattrus C, Zepeda J, Cornick R. Localising South Africa’s Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) for brazilian primary care: Case study from Florianópolis. Submitted to BMJ Global Health as part of the PACK Collection, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Awotiwon AA, Sword C, Eastman T. Use of a mentorship model to localise and pilot South Africa’s Practical approach to care kit in three Nigerian States. Submitted to BMJ Global Health as part of the PACK Collection, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mekonnen Y, Hanlon C, Ferede SE. Transforming primary health care with the Ethiopian Primary Health Care Clinical Guidelines: localisation of the Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) programme. Submitted to BMJ Global Health as part of the PACK Collection, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cornick R, Wattrus C, Eastman T. Crossing borders: the PACK experience of spreading a complex health system intervention across low and middle-income countries. Accepted by BMJ Global Health September 2018 as part of PACK Collection, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cornick R, Picken S, Wattrus C, et al. The Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) guide: developing a clinical decision support tool to simplify, standardise and strengthen primary healthcare delivery. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3(Suppl 5):e000962 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. O'Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;308 10.1002/14651858.CD000409.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pagaiya N, Garner P. Primary care nurses using guidelines in Thailand: a randomized controlled trial. Trop Med Int Health 2005;10:471–7. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01404.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zwarenstein M, Bheekie A, Lombard C, et al. Educational outreach to general practitioners reduces children's asthma symptoms: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Implement Sci 2007;2:30 10.1186/1748-5908-2-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Knowles MS, Tough A. Reviewed work: andragogy in action: applying modern principles of adult learning by Malcolm S. Knowles The Journal of Higher Education 1985;56:707–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tiedeman DV, Knowles M. The adult learner: a neglected species. Educational Researcher 1979;8:20–2. 10.2307/1174362 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wenger E. Communities of practice and social learning systems. Organization 2000;7:225–46. 10.1177/135050840072002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. John-Steiner V, Mahn H. Sociocultural approaches to learning and development: a Vygotskian framework. Educ Psychol 1996;31:191–206. 10.1080/00461520.1996.9653266 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lave J. Situating learning in communities of practice. Perspectives on socially shared cognition 1991;2:63–82. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mezirow J. Transformative learning: theory to practice. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 1997;1997:5–12. 10.1002/ace.7401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Verenikina I. Understanding scaffolding and the ZPD in educational research. University of Wollongong: Research Online, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kolb DA. Experience as the source of learning and development prentice-hall. Englewood Cliffs, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mann K, Gordon J, MacLeod A. Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2009;14:595–621. 10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hoffman-Kipp P, Artiles AJ, López-Torres L. Beyond reflection: teacher learning as praxis. Theory Pract 2003;42:248–54. 10.1207/s15430421tip4203_12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kenny NP, Mann KV, MacLeod H. Role modeling in physicians' professional formation: reconsidering an essential but untapped educational strategy. Acad Med 2003;78:1203–10. 10.1097/00001888-200312000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Asian J Soc Psychol 1999;2:21–41. 10.1111/1467-839X.00024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ana J, Sword C. Final report on PACK nigeria adult pilot. 2017 BMJ Publishing Group Ltd, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bertone MP, Witter S. The complex remuneration of human resources for health in low-income settings: policy implications and a research agenda for designing effective financial incentives. Hum Resour Health 2015;13:62 10.1186/s12960-015-0058-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Huillery E, Seban J. Financial incentives are counterproductive in non-profit sectors: evidence from a health experiment, 2015. [Google Scholar]