Abstract

Background:

Atraumatic rotator cuff tear is a common orthopaedic complaint for people >60 years of age. Lack of evidence or consensus on appropriate treatment for this type of injury creates the potential for substantial discretion in treatment decisions. To our knowledge, no study has assessed the implications of this discretion on treatment patterns across the United States.

Methods:

All Medicare beneficiaries in the United States with a new magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-confirmed atraumatic rotator cuff tear were identified with use of 2010 to 2012 Medicare administrative data and were categorized according to initial treatment (surgery, physical therapy, or watchful waiting). Treatment was modeled as a function of the clinical and demographic characteristics of each patient. Variation in treatment rates across hospital referral regions and the presence of area treatment signatures, representing the extent that treatment rates varied across hospital referral regions after controlling for patient characteristics, were assessed. Correlations between measures of area treatment signatures and measures of physician access in hospital referral regions were examined.

Results:

Among patients who were identified as having a new, symptomatic, MRI-confirmed atraumatic rotator cuff tear (n = 32,203), 19.8% were managed with initial surgery; 41.3%, with initial physical therapy; and 38.8%, with watchful waiting. Patients who were older, had more comorbidity, or were female, of non-white race, or dual-eligible for Medicaid were less likely to receive surgery (p < 0.0001). Black, dual-eligible females had 0.42-times (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.34 to 0.50) lower odds of surgery and 2.36-times (95% CI, 2.02 to 2.70) greater odds of watchful waiting. Covariate-adjusted odds of surgery varied dramatically across hospital referral regions; unadjusted surgery and physical therapy rates varied from 0% to 73% and from 6% to 74%, respectively. On average, patients in high-surgery areas were 62% more likely to receive surgery than the average patient with identical measured characteristics, and patients in low-surgery areas were half as likely to receive surgery than the average comparable patient. The supply of orthopaedic surgeons and the supply of physical therapists were associated with greater use of initial surgery and physical therapy, respectively.

Conclusions:

Patient characteristics had a significant influence on treatment for atraumatic rotator cuff tear but did not explain the wide-ranging variation in treatment rates across areas. Local-area physician supply and specialty mix were correlated with treatment, independent of the patient’s measured characteristics.

Chronic shoulder pain is the second-most common orthopaedic complaint in the United States after knee pain1. Atraumatic rotator cuff tear is a frequent cause of shoulder pain and dysfunction in the population over 60 years of age and is present in up to 49.4% of patients with a history of shoulder complaints2. Symptomatic atraumatic rotator cuff tear is associated with functional limitation that can affect activities of daily living, sleep patterns, and overall quality of life3-5. Direct costs associated with surgical repair alone exceed $1.5 billion annually in the United States4-7. The rate of surgery increased by 141% from 1996 to 2006 and continued to rise through 20124,5,8.

While surgical repair has been shown to be effective, nonoperative approaches have recently demonstrated similar improvements6,9-14. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) Appropriate Use Criteria (AUC) demonstrate the lack of guideline recommendations or consistent clinical opinion on the relative effectiveness and appropriateness of alternative treatment options for patients with atraumatic rotator cuff tear15. The AAOS physician panels agreed that repair was either appropriate or rarely appropriate for only 15% of 432 vignettes3.

Mixed expert opinion and limited clinical evidence on the effectiveness of alternative treatment paths for patients with an atraumatic rotator cuff tear create great potential for professional discretion in treating clinically similar patients. When evidence on treatment effectiveness is limited in health care, the costs associated with evidence diffusion16-20, variation in local area physician supply, specialty mix21-23, and market structures24-30 can lead to what have been termed as local area treatment signatures31, practice styles18,32,33, or schools of thought16,34. The existence of area treatment signatures implies that the treatment provided to a patient will vary depending on where he or she lives and seeks care. The identification and measurement of area treatment signatures has been shown to be a vital first step for comparative effectiveness research of treatments in real-world practice35-41.

The treatment of atraumatic rotator cuff tears may be particularly susceptible to the formation of area treatment signatures resulting from a lack of clear and consistent evidence on the effectiveness of alternative treatment paths. However, to our knowledge, no studies have examined area treatment signatures for patients with atraumatic rotator cuff tears. The purposes of the present study were to examine factors influencing the initial treatment choice for patients with new symptomatic atraumatic rotator cuff tears and to assess the extent of area treatment signatures across hospital referral regions.

Materials and Methods

The present study was a retrospective cohort study of Medicare beneficiaries with claims indicating a new magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-confirmed atraumatic rotator cuff tear between January 2011 and March 2012. Complete Medicare claims and beneficiary summary files from 2010 to 2012 were obtained from the Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse42.

The initial cohort included 2,525,519 beneficiaries with any of 192 shoulder-related International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis codes in 2011. The index date for each beneficiary was defined as the date of the first shoulder-related diagnosis in 2011. To ensure data completeness, patients were excluded if they were not continuously enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare Parts A and B from 365 days before to 104 days after the index date, were <66 years old at the index date, or had a residence ZIP code in 2011 that was outside the continental United States. Patients with any shoulder-related health-care utilization in the 365 days before the index date or who used either emergency department services or an ambulance transfer within 1 day before the index date were excluded in order to focus on new, nontraumatic problems.

A narrow definition for atraumatic rotator cuff tear was used to limit the extent of clinical variability among patients. Beneficiaries with an MRI-confirmed atraumatic rotator cuff tear were defined as those who had MRI of the upper-extremity within 90 days after the index date and a diagnosis of rotator cuff tear within 14 days after the earliest dated MRI43. Patients with complicating diagnoses, including cervical spine pain, scapular pain, glenohumeral arthritis, humeral fracture, inflammatory arthritis, adhesive capsulitis, or dementia during the period from 365 days before to 104 days after the index date were excluded, following published guidance6. Patients with any observed ICD-9 procedure code indicating anatomical shoulder replacement within 104 days after the index date were excluded. Table I details the sample exclusion process.

TABLE I.

Medicare Cohort Size by Study Sample Inclusion Criteria*

| Inclusion Criteria | No. of Patients |

| Medicare Part-B “carrier” claim with shoulder-related diagnosis in 2011 (index diagnosis) | 2,525,519 |

| No carrier claim with shoulder-related diagnosis in 365 days before index diagnosis in 2011 | 1,871,294 |

| Continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B, never enrolled in an HMO, from 365 days prior to index date to 104 days after index date | 1,598,175 |

| Age of ≥66 years at index date | 1,588,184 |

| No claim indicating emergency department or ambulance use within 1 day before index date | 1,290,052 |

| Claim indicating MRI within 90 days after index date | 144,487 |

| Rotator cuff tear diagnosis within 14 days after first MRI | 65,220 |

| Complete data available for geography measures (hospital referral region, county-level statistics) | 63,075 |

| No cervical spine pain, scapular pain, glenohumeral arthritis, humeral fracture, inflammatory arthritis, adhesive capsulitis, or dementia during period 365 days prior to index date to 104 days after index date | 32,203 |

HMO = health maintenance organization.

Initial Treatment Choice

Treatment was measured with use of ICD-9 procedure and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes on Medicare Part A and B claims over the 104-day post-index period. Patients were categorized into 1 of 2 primary treatment groups—surgery or physical therapy—on the basis of the first treatment received. Patients who did not receive surgery or physical therapy during the period were categorized into a third treatment group, watchful waiting. The table in the Appendix provides complete definitions of treatment and all variables described below.

Patient Characteristics Affecting Treatment Choice

Patient age; modified frailty index score44; use of a cane, walker, or wheelchair; Charlson comorbidity index score45,46; and total Medicare payments made to providers over the 365 days prior to the index date were measured as patient-specific clinical factors. Health-care spending has been shown to be indicative of an individual’s health status and health-care utilization characteristics47. Patient demographic characteristics, including sex, race, and Medicaid dual-eligibility status at the index date were also measured. The number of pre-index physical therapy visits that patients had in 2011 was measured to control for potential differences in out-of-pocket costs for therapy that arise through the cap placed on Medicare payments for therapy services by the Balanced Budget Act.

Independent relationships between patient characteristics and each treatment alternative were estimated with use of logistic regression models48. Continuous variables were cut and specified with use of binary variables for interpretability. Model-fit statistics included log-likelihood, McFadden R2, and Tjur R2 values49-51.

Area Treatment Signature Measurement

Area treatment signatures were measured at the hospital referral region level as the difference between the observed treatment rate and the expected treatment rate after adjusting for patient characteristics. Hospital referral regions are geographic regions developed by researchers with use of The Dartmouth Atlas of Heath Care52 to represent regional health-care markets for tertiary medical care; each hospital referral region includes at least 1 major hospital and a minimum population of 120,00022. Patients were assigned to a hospital referral region on the basis of residence ZIP code as documented in the 2011 Medicare Beneficiary Summary File.

Hospital referral region-specific area treatment signatures were estimated with use of an area treatment rate differential.

First, the observed treatment rates in each hospital referral region were calculated as the proportion of patients in the hospital referral region categorized as receiving surgery, physical therapy, and watchful waiting. Risk-adjusted treatment rates for each hospital referral region were then calculated as the average predicted probability of treatment, estimated with regression models as previously described, across patients in the hospital referral region40,53-55. The area treatment rate differential for each hospital referral region was finally calculated by subtracting the observed rate from the expected rate for each treatment. The area treatment rate differential is therefore the difference between the unadjusted probability that patients in a hospital referral region received a given treatment, equal to the proportion of patients that received the treatment in that area, and the adjusted probability that the average patient in the full sample with the same characteristics received that treatment, estimated with use of regression models. Area treatment rate differentials represent the theorized collective influence of unmeasured factors specific to each local area that affect the initial treatment choice for an atraumatic rotator cuff tear. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CIs) around area treatment rate differentials were estimated with use of the bootstrap method (4,500 iterations)56,57.

Area-Related Measures

Last, we assessed the extent that differences in the characteristics of physician access across hospital referral regions were correlated with variation in area treatment signatures. Physician access measures included 6 different measures of physician supply by specialty and 5 measures of physician specialty mix in 2011. The 6 supply measures included the total numbers of physicians, orthopaedic surgeons, physical therapists, primary care physicians, medical specialist physicians, and general surgeons per 100,000 residents in a hospital referral region. Measures of physician specialty mix were created for each specialty group as the ratio of specialty-specific physician supply to total physician supply. Data for hospital referral region-level physician supply were obtained from The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care, which is funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Dartmouth Clinical and Translational Science Institute52. Correlations between the area treatment rate differential and the physician supply and specialty mix of the patient residence hospital referral region were evaluated with use of Pearson product-moment correlation, weighted by the number of patients in each hospital referral region.

Results

There were 32,203 patients with a new MRI-confirmed diagnosis of atraumatic rotator cuff tear in 2011 who met all inclusion criteria (Table I). The initial treatment was surgery for 19.8% of patients, physical therapy for 41.3%, and watchful waiting for 38.8%. Table II shows descriptive statistics for the cohort by treatment group. On average, patients who had initial surgery were younger, were more likely to be white and male, were less likely to be Medicare-Medicaid dual-eligible, and had fewer comorbid conditions than patients who received initial physical therapy or watchful waiting. Patients who received physical therapy were slightly younger and had greater comorbidity than patients who received watchful waiting.

TABLE II.

Cohort Summary Characteristics

| All | Surgery | Physical Therapy | Watchful Waiting | P Value | |

| No. of patients | 32,203 (100%) | 6,388 (19.8%) | 13,311 (41.3%) | 12,504 (38.8%) | |

| Treatment group (no. of patients) | <0.001 | ||||

| Surgery | 6,388 (19.8%) | 6,388 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Physical therapy | 13,311 (41.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 13,311 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Watchful waiting | 12,504 (38.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 12,504 (100.0%) | |

| Age* (yr) | 73.97 ± 5.80 | 72.52 ± 4.86 | 74.26 ± 5.82 | 74.39 ± 6.09 | <0.001 |

| Charlson comorbidity index* | 1.59 ± 1.97 | 1.29 ± 1.65 | 1.58 ± 1.95 | 1.75 ± 2.11 | <0.001 |

| Frailty index* | 0.55 ± 0.81 | 0.45 ± 0.72 | 0.57 ± 0.81 | 0.59 ± 0.84 | <0.001 |

| Cane (no. of patients) | 168 (0.5%) | 18 (0.3%) | 74 (0.6%) | 76 (0.6%) | 0.014 |

| Walker (no. of patients) | 857 (2.7%) | 123 (1.9%) | 375 (2.8%) | 359 (2.9%) | <0.001 |

| Wheelchair (no. of patients) | 284 (0.9%) | 29 (0.5%) | 102 (0.8%) | 153 (1.2%) | <0.001 |

| Prior physical therapy days* | 1.16 ± 4.50 | 0.69 ± 3.05 | 1.73 ± 5.67 | 0.79 ± 3.57 | <0.001 |

| Pre-365 Medicare reimbursements* ($) | 7,601 ± 14,132 | 5,675 ± 9,495 | 7,977 ± 15,004 | 8,185 ± 15,043 | <0.001 |

| Male (no. of patients) | 16,175 (50.2%) | 3,657 (57.2%) | 6,136 (46.1%) | 6,382 (51.0%) | <0.001 |

| Race (no. of patients) | <0.001 | ||||

| White | 29,644 (92.1%) | 6,018 (94.2%) | 12,338 (92.7%) | 11,288 (90.3%) | |

| Black | 1,389 (4.3%) | 213 (3.3%) | 500 (3.8%) | 676 (5.4%) | |

| Hispanic | 401 (1.2%) | 40 (0.6%) | 143 (1.1%) | 218 (1.7%) | |

| Asian | 264 (0.8%) | 25 (0.4%) | 126 (0.9%) | 113 (0.9%) | |

| Other | 505 (1.6%) | 92 (1.4%) | 204 (1.5%) | 209 (1.7%) | |

| Medicaid dual-eligible (no. of patients) | 2,204 (6.8%) | 266 (4.2%) | 719 (5.4%) | 1,219 (9.7%) | <0.001 |

The values are given as the mean and the standard deviation.

Assessing the Effects of Patient-Specific Characteristics on Treatment Choice

Odds-ratio estimates relating measured patient characteristics to each treatment alternative are shown in Table III. Increasing age and comorbidity were each associated with a lower probability of surgery and a higher probability of watchful waiting. Patients who were ≥86 years of age had an estimated 0.28-times (95% CI, 0.23 to 0.35) lower odds of receiving initial surgery, on average, than patients 66 to 69 years of age. Having a Charlson comorbidity index score of ≥4 was associated with a 0.73-times (95% CI, 0.66 to 0.82) lower odds of surgery and a 1.28-times (95% CI, 1.18 to 1.39) greater odds of watchful waiting relative to having a Charlson score of 0. On average, males had a 1.30-times (95% CI, 1.23 to 1.38) greater odds of surgery and a 0.76-times (95% CI, 0.73 to 0.80) lower odds of physical therapy as initial treatment. Non-white race and Medicaid dual eligibility were each associated with lower odds of surgery and higher odds of watchful waiting. Black females who were dual-eligible for Medicaid had a 0.42-times (95% CI, 0.34 to 0.50) lower odds of initial surgery and a 2.36-times (95% CI, 2.02 to 2.70) greater odds of watchful waiting relative to white, non-dual-eligible males.

TABLE III.

Treatment Choice Logistic Regression Model Results

| Surgery | Physical Therapy | Watchful Waiting | |

| Model covariables* | |||

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Age group (ref: 66-69 yr) | |||

| 70-75 yr | 0.88 (0.82, 0.93)† | 1.12 (1.06, 1.18)† | 0.99 (0.93, 1.04) |

| 76-79 yr | 0.66 (0.60, 0.72)† | 1.20 (1.11, 1.28)† | 1.11 (1.04, 1.19)‡ |

| 80-85 yr | 0.42 (0.38, 0.47)† | 1.29 (1.20, 1.39)† | 1.28 (1.19, 1.38)† |

| ≥86 yr | 0.28 (0.23, 0.35)† | 1.19 (1.05, 1.35)‡ | 1.57 (1.39, 1.78)† |

| Charlson comorbidity index (ref: 0) | |||

| 1 | 0.94 (0.87, 1.01)§ | 0.94 (0.88, 1.00)# | 1.12 (1.05, 1.19)† |

| 2 | 0.90 (0.82, 0.98)# | 1.00 (0.94, 1.08) | 1.08 (1.00, 1.16)# |

| 3 | 0.85 (0.77, 0.95)‡ | 0.93 (0.85, 1.01)§ | 1.21 (1.11, 1.31)† |

| ≥4 | 0.73 (0.66, 0.82)† | 0.94 (0.87, 1.02) | 1.28 (1.18, 1.39)† |

| Frailty index (ref: 0) | |||

| 1 | 0.96 (0.90, 1.03) | 1.00 (0.94, 1.05) | 1.03 (0.98, 1.09) |

| 2 | 0.90 (0.80, 1.01)§ | 0.96 (0.87, 1.05) | 1.12 (1.02, 1.22)# |

| ≥3 | 0.78 (0.65, 0.94)‡ | 0.90 (0.79, 1.02) | 1.25 (1.10, 1.42)† |

| Cane | 0.79 (0.47, 1.32) | 0.92 (0.67, 1.26) | 1.20 (0.88, 1.64) |

| Walker | 1.07 (0.87, 1.31) | 0.91 (0.78, 1.06) | 1.07 (0.92, 1.24) |

| Wheelchair | 0.76 (0.51, 1.12) | 0.77 (0.60, 1.00)# | 1.42 (1.11, 1.82)‡ |

| Pre-365 Medicare reimbursements | |||

| $1,400 to $3,229 | 0.94 (0.87, 1.01)§ | 1.18 (1.10, 1.26)† | 0.90 (0.84, 0.96)‡ |

| $3,230 to $7,369 | 0.85 (0.79, 0.93)† | 1.28 (1.19, 1.37)† | 0.88 (0.82, 0.94)† |

| $7,370 to $621,000 | 0.84 (0.76, 0.92)† | 1.20 (1.11, 1.30)† | 0.95 (0.87, 1.02) |

| Prior physical therapy use (ref: 0) | |||

| 1-4 d | 0.71 (0.60, 0.84)† | 1.93 (1.72, 2.17)† | 0.60 (0.52, 0.68)† |

| 5-9 d | 0.74 (0.62, 0.88)† | 1.85 (1.63, 2.10)† | 0.61 (0.53, 0.70)† |

| 10-19 d | 0.66 (0.55, 0.79)† | 2.11 (1.86, 2.41)† | 0.56 (0.48, 0.65)† |

| ≥20 d | 0.47 (0.34, 0.66)† | 3.03 (2.48, 3.72)† | 0.42 (0.34, 0.53)† |

| Demographics | |||

| Male | 1.30 (1.23, 1.38)† | 0.76 (0.73, 0.80)† | 1.10 (1.05, 1.16)† |

| Race (ref: white) | |||

| Black | 0.78 (0.67, 0.91)‡ | 0.81 (0.73, 0.91)† | 1.41 (1.26, 1.57)† |

| Hispanic | 0.61 (0.44, 0.87)‡ | 1.02 (0.82, 1.26) | 1.23 (0.99, 1.52)§ |

| Asian | 0.50 (0.33, 0.76)‡ | 1.51 (1.17, 1.94)‡ | 0.92 (0.72, 1.19) |

| Other | 0.87 (0.69, 1.10) | 1.02 (0.85, 1.23) | 1.08 (0.90, 1.30) |

| Medicaid dual-eligible | 0.70 (0.61, 0.81)† | 0.63 (0.57, 0.69)† | 1.86 (1.69, 2.04)† |

| Model summary and fit statistics | |||

| No. of patients | 32,203 | 32,203 | 32,203 |

| Model R2 | |||

| McFadden | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Tjur | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Log likelihood | |||

| Null | −16,041.27 | −21,835.36 | −21,510.82 |

| Model | −15,529.97 | −21,389.15 | −21,117.93 |

| Wald chi-square | |||

| Clinical and demographic | 901.64 | 841.98 | 732.95 |

| Demographic | 166.64 | 216.74 | 250.58 |

| Clinical | 675.10 | 578.91 | 432.92 |

The values are given as the odds ratio, with the 95% CI in parentheses.

P < 0.001.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.1.

P < 0.05.

Geographic Variation in Treatment Rates

The 304 hospital referral regions included, on average, 106 patients with an atraumatic rotator cuff tear. Across all hospital referral regions, the observed rates of surgery varied from 0% to 73%, the rates of physical therapy varied from 6% to 74%, and the rates of watchful waiting varied from 11% to 67%. There were 3 hospital referral regions (including 72 patients) in which no patient received surgery.

Area Treatment Signatures as Area Treatment Rate Differentials

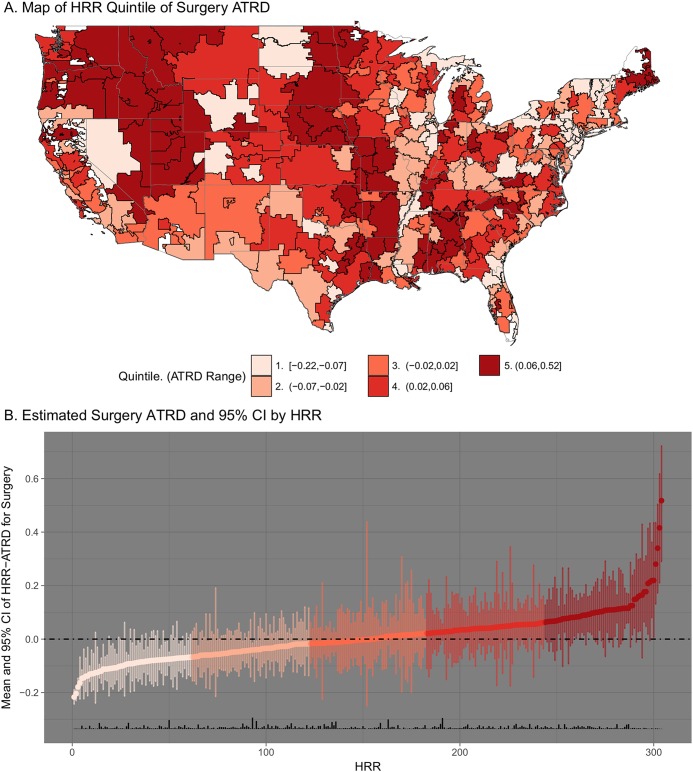

There was broad variation in the estimated area treatment rate differentials across hospital referral regions. Geographic variation in area treatment rate differentials is highlighted in Figure 1. Figure 1-A shows hospital referral regions categorized by the quintile of the area treatment rate differential for surgery. The average area treatment rate differential and the treatment rate across hospital referral regions in each quintile are provided in the figure key. Figure 1-B illustrates the surgery area treatment rate differential estimate and 95% CI for all hospital referral regions, from lowest to highest area treatment rate differential; a rug plot along the x axis shows relative sample size across hospital referral regions. Analogous plots for physical therapy and watchful waiting are provided in the Appendix. Table IV provides quintile-level area treatment rate differential estimates and 95% CIs, as well as the mean and interquartile range of observed treatment rates, for all area treatment rate differential quintile groups.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1-A Hospital referral regions (HRRs) across the United States, colored by quintile of area treatment rate differential (ATRD) for surgery. A higher quintile reflects higher use of surgery in the hospital referral region than expected on the basis of average treatment patterns across the entire sample as estimated with use of logistic regression models. The range of values across hospital referral regions in each quintile is shown in the key at the bottom of the figure. Fig. 1-B Estimated ATRDs for surgery across HRRs, in ascending order. The vertical span of each point represents the 95% CI as estimated with the bootstrap method with 4,500 iterations. The color indicates the quintile of ATRD for surgery. The rug plot along the x axis (vertical black bars) shows the relative proportion of the sample that resides in each hospital referral region.

TABLE IV.

Summary of Area Treatment Rate Differential Estimates and Observed Treatment Rates Across Quintiles of Treatment-Specific Area Treatment Rate Differentials

| Treatment-Specific Area Treatment Rate Differential Quintile |

|||||

| Treatment | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Surgery | |||||

| Area treatment rate differential* | −0.10 (−0.21, 0.00) | −0.04 (−0.13, 0.06) | 0.00 (−0.12, 0.13) | 0.04 (−0.08, 0.16) | 0.13 (−0.02, 0.43) |

| Treatment rate† | 0.10 (0.08, 0.13) | 0.16 (0.15, 0.17) | 0.20 (0.19, 0.21) | 0.24 (0.23, 0.25) | 0.33 (0.29, 0.34) |

| Physical therapy | |||||

| Area treatment rate differential* | −0.16 (−0.37, −0.01) | −0.07 (−0.20, 0.06) | −0.01 (−0.13, 0.12) | 0.05 (−0.08, 0.20) | 0.14 (−0.01, 0.33) |

| Treatment rate† | 0.24 (0.22, 0.29) | 0.33 (0.32, 0.35) | 0.40 (0.39, 0.42) | 0.47 (0.45, 0.49) | 0.56 (0.53, 0.59) |

| Watchful waiting | |||||

| Area treatment rate differential* | −0.11 (−0.28, 0.03) | −0.04 (−0.17, 0.09) | 0.00 (−0.12, 0.11) | 0.04 (−0.09, 0.18) | 0.13 (−0.05, 0.34) |

| Treatment rate† | 0.27 (0.24, 0.3) | 0.35 (0.33, 0.36) | 0.39 (0.37, 0.4) | 0.43 (0.42, 0.44) | 0.52 (0.48, 0.56) |

The values are given as the mean, with the 95% CI in parentheses.

The values are given as the means, with the interquartile range in parentheses.

Across the 20% of hospital referral regions with the lowest area treatment rate differential for surgery (first quintile), the average area treatment rate differential was −0.10 and the average observed rate of surgery was 0.10. In other words, while only 10% of the patients in these hospital referral regions received initial surgery, it was expected that approximately 20% of patients in these hospital referral regions would have received surgery on the basis of their measured clinical and demographic characteristics. Put differently, about half as many patients living in those hospital referral regions received surgery as was expected on the basis of their measured characteristics. Conversely, patients living in hospital referral regions within the highest quintile of area treatment rate differential for surgery had an average area treatment rate differential of 0.13 and an observed surgery rate of 0.33, suggesting that while 33% of patients in the hospital referral region received surgery, only 20% were expected to receive surgery based on their measured characteristics (i.e., 62% more patients received surgery than expected). In other words, on average, patients in high-surgery areas appeared nearly twice as likely to receive surgery as the average patient with identical measured characteristics.

Associations Between Local-Area Provider Access and Area Treatment Signatures

Figure 2 illustrates associations between alternative physician access measures and the area treatment rate differential for each treatment group. Separate plots are drawn for each treatment-access measure combination. Each plot shows the LOESS fit relating the hospital referral region’s area treatment rate differential value ranking (x axis) to the hospital referral region’s physician access measure (y axis; measured as the percent difference from the mean). The Pearson correlation coefficient and p value testing the association are noted in each plot. The terms Supply and Proportion that appear in the right margin of the figure denote per-capita physician supply and specialty-mix measures, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Associations between alternative physician access measures and treatment-specific area treatment rate differentials (ATRDs) at the hospital referral region (HRR) level. Separate plots were drawn for each treatment and access measure combination. Trend lines, drawn with use of the LOESS local regression method, show the bivariate relationship between area treatment rate differential value ranking of HRRs in ascending order (x axis) and the HRR physician access measure (as the percent difference from the mean) (y axis). Mean difference was calculated by subtracting the mean value of the access measure across HRRs from each HRR’s specific access measure value. The values at the upper left corner of each plot represent the Pearson correlation coefficient and p value testing the association between the ATRD and the access measure values across HRRs, weighted by HRR sample size. Data pertaining to per-capita physician supply are represented by “Supply” and are shown in black. Data pertaining to the proportion of all physicians in a given specialty are represented by “Proportion” and are shown in red. PT = physical therapy.

Greater local-area physician supply was associated with greater use of initial physical therapy and lower use of surgery or watchful waiting (p < 0.01 for all). A greater proportion of providers in an area who were orthopaedic surgeons was associated with a higher surgery area treatment rate differential, whereas greater access to physical therapists was associated with a greater physical therapy area treatment rate differential and a lower surgery area treatment rate differential (p < 0.01 for all).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated wide variation in the initial treatment of elderly patients with atraumatic rotator cuff tears, consistent with established literature documenting unwarranted variation in the treatment of patients with orthopaedic problems58-62. This study contributes to our understanding of initial treatment utilization for elderly patients with an atraumatic rotator cuff tear, the influence of patient characteristics on these decisions, the presence of area treatment signatures in this context, and how area treatment signatures are correlated with physician supply and specialty mix across areas.

Measured clinical and demographic characteristics had significant independent relationships with initial treatment choice but together accounted for only 2% to 3% of observed variation. Although R2 statistics in models with binary dependent variables should be interpreted with caution, the high degree of unexplained variation in treatment choice supports the idea that treatment may be highly sensitive to nonclinical factors or, perhaps more interestingly, that there is inconsistency across providers in terms of their beliefs about the appropriateness and effectiveness of alternative treatment paths for clinically identical patients. Patients with an atraumatic rotator cuff tear and other musculoskeletal problems often may face trade-offs across alternative domains of outcomes when deciding on a treatment course. For example, the optimum treatment may differ for clinically identical patients who diverge in terms of their goals related to improvements in pain and range of motion.

Physician supply and specialty mix in the hospital referral region where patients lived were correlated with area treatment signatures in the present study. Generally, patients were observed to be more likely to use treatments to which they had greater access. Patients in areas in which a greater proportion of physicians were orthopaedic surgeons were more likely to have initial surgery, whereas those in areas with greater access to physical therapists were more likely to receive physical therapy. These results lend support to the idea that the initial treatment for an atraumatic rotator cuff tear is sensitive to the characteristics of the region and health-care system where a patient presents and that these factors contribute to the presence of area treatment signatures. However, these correlations should not be interpreted causally. It is possible, for example, that an area’s rurality or other socioeconomic characteristics are associated with physician access and treatment choice. Furthermore, interpretation may be complicated from correlation or interactions between supplies of different specialty groups and by the reciprocal relationship between supply and demand. Additional research is necessary to more accurately estimate the influence of individual contributors to seemingly unwarranted variation in treatment.

Several limitations related to the use of administrative data must be considered when interpreting the results of the present study. Administrative data reflect utilization only and may not reflect provider recommendation or intent. Identifying patients with an atraumatic rotator cuff tear using ICD-9 codes is also unvalidated and may suffer from poor sensitivity or specificity, particularly for patients who are managed nonoperatively. The present study applied stringent inclusion criteria in order to maximize confidence that the cohort was consistent with those of prior studies that have suggested that a treatment paradigm does, or should, exist4,6,9,15. Administrative data also lack information on specific clinical characteristics that may influence treatment decisions in practice, such as a patient’s clinical presentation (e.g., tear size, fatty infiltration, muscle atrophy, pain level, and range of motion)3. Age and comorbidity may capture some of the variation in these anatomical factors. Importantly, we are aware of no evidence to suggest that unmeasured clinical characteristics vary systematically across hospital referral regions, and risk of bias from unmeasured clinical characteristics is therefore thought to be minimal. Despite their inherent limitations, observational data are necessary for studying the determinants of treatment choices, and the implications of those choices, in the real world.

In conclusion, rates of alternative initial treatments used by patients with atraumatic rotator cuff tears varied widely across the United States after controlling for clinical and demographic characteristics. Associations between these risk-adjusted rates and area-level provider-supply measures support the idea that treatment signatures exist. The implications of this variation on the broad array of clinical and cost-related outcomes potentially affected by early treatment choices for atraumatic rotator cuff tears are unknown. A natural next step is to ask (1) whether specific treatments are overused or underused and (2) whether treatment rates could be modified to improve patient outcomes or lower costs. Under certain assumptions, treatment variation of the nature found in the present study can be used to address these questions. Research on the determinants of treatment choice for atraumatic rotator cuff tears is necessary in order to contextualize and ascertain the validity of those assumptions, ultimately facilitating the conduct and interpretation of research assessing the potential impacts of efforts to modify treatment practice.

Appendix

Supplementary materials including (1) a table showing full descriptions of the study concepts and variables and (2) figures showing ATRD (area treatment rate differential) plots for physical therapy and watchful waiting are available with the online version of this article as a data supplement at jbjs.org (http://links.lww.com/JBJSOA/A57).

Acknowledgments

Note: Support for this study was provided by the Center for Comparative Effectiveness Research in Orthopaedics (CEROrtho), which is associated with the University of South Carolina Arnold School of Public Health. Data used to calculate physician supply and specialty mix were obtained from The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care, which is funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Dartmouth Clinical and Translational Science Institute, under award number UL1TR001086 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Investigation performed at the Center for Effectiveness Research in Orthopaedics (CERortho), the University of South Carolina, Columbia, South Carolina

Disclosure: No external funds were received in support of this study. This study was funded, independent of results, by the Center for Effectiveness Research in Orthopaedics (CERortho), which is associated with the University of South Carolina. On the Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest forms, which are provided with the online version of the article, one or more of the authors checked “yes” to indicate that the author had a relevant financial relationship in the biomedical arena outside the submitted work (http://links.lww.com/JBJSOA/A56).

References

- 1.Weinstein SI, Yelin EH. Burden of musculoskeletal disease in the United States: 2014 report. http://www.boneandjointburden.org/2014-report. Accessed 2018 Apr 4.

- 2.Reilly P, Macleod I, Macfarlane R, Windley J, Emery RJ. Dead men and radiologists don’t lie: a review of cadaveric and radiological studies of rotator cuff tear prevalence. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006. March;88(2):116-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pappou IP, Schmidt CC, Jarrett CD, Steen BM, Frankle MA. AAOS appropriate use criteria: optimizing the management of full-thickness rotator cuff tears. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013. December;21(12):772-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith DS. Conservative rotator cuff treatment. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2014;30(2):127-30. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colvin AC, Egorova N, Harrison AK, Moskowitz A, Flatow EL. National trends in rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012. February 01;94(3):227-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuhn JE, Dunn WR, Sanders R, An Q, Baumgarten KM, Bishop JY, Brophy RH, Carey JL, Holloway BG, Jones GL, Ma CB, Marx RG, McCarty EC, Poddar SK, Smith MV, Spencer EE, Vidal AF, Wolf BR, Wright RW; MOON Shoulder Group. Effectiveness of physical therapy in treating atraumatic full-thickness rotator cuff tears: a multicenter prospective cohort study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013. October;22(10):1371-9. Epub 2013 Mar 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vitale MA, Vitale MG, Zivin JG, Braman JP, Bigliani LU, Flatow EL. Rotator cuff repair: an analysis of utility scores and cost-effectiveness. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007. Mar-Apr;16(2):181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varkey DT, Patterson BM, Creighton RA, Spang JT, Kamath GV. Initial medical management of rotator cuff tears: a demographic analysis of surgical and nonsurgical treatment in the United States Medicare population. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016. December;25(12):e378-85. Epub 2016 Aug 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kweon C, Gagnier JJ, Robbins CB, Bedi A, Carpenter JE, Miller BS. Surgical versus nonsurgical management of rotator cuff tears: predictors of treatment allocation. Am J Sports Med. 2015. October;43(10):2368-72. Epub 2015 Aug 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernstein J. The variability of patient preferences. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012. July;470(7):1966-72. Epub 2012 Jan 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernstein J. Not the last word: choosing wisely. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015. October;473(10):3091-7. Epub 2015 Aug 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baydar M, Akalin E, El O, Gulbahar S, Bircan C, Akgul O, Manisali M, Torun Orhan B, Kizil R. The efficacy of conservative treatment in patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tears. Rheumatol Int. 2009. April;29(6):623-8. Epub 2008 Oct 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kukkonen J, Joukainen A, Lehtinen J, Mattila KT, Tuominen EK, Kauko T, Äärimaa V. Treatment of nontraumatic rotator cuff tears: a randomized controlled trial with two years of clinical and imaging follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015. November 04;97(21):1729-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moosmayer S, Lund G, Seljom US, Haldorsen B, Svege IC, Hennig T, Pripp AH, Smith HJ. Tendon repair compared with physiotherapy in the treatment of rotator cuff tears: a randomized controlled study in 103 cases with a five-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014. September 17;96(18):1504-14. Epub 2014 Sep 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedowitz RA, Yamaguchi K, Ahmad CS, Burks RT, Flatow EL, Green A, Iannotti JP, Miller BS, Tashjian RZ, Watters WC, 3rd, Weber K, Turkelson CM, Wies JL, Anderson S, St Andre J, Boyer K, Raymond L, Sluka P, McGowan R; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Optimizing the management of rotator cuff problems. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011. June;19(6):368-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phelps CE. Diffusion of information in medical care. J Econ Perspect. 1992. Summer;6(3):23-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phelps CE. Information diffusion and best practice adoption. In: Culyer AJ, Newhouse JP, editors. Handbook of health economics. New York: Elsevier; 2000. p 228-64. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mandelblatt JS, Berg CD, Meropol NJ, Edge SB, Gold K, Hwang YT, Hadley J. Measuring and predicting surgeons’ practice styles for breast cancer treatment in older women. Med Care. 2001. March;39(3):228-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ayanian JZ, Hauptman PJ, Guadagnoli E, Antman EM, Pashos CL, McNeil BJ. Knowledge and practices of generalist and specialist physicians regarding drug therapy for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1994. October 27;331(17):1136-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silber JH, Kaestner R, Even-Shoshan O, Wang Y, Bressler LJ. Aggressive treatment style and surgical outcomes. Health Serv Res. 2010. December;45(6 Pt 2):1872-92. Epub 2010 Sep 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ricketts TC, Belsky DW. Medicare costs and surgeon supply in hospital service areas. Ann Surg. 2012. March;255(3):474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med. 2003. February 18;138(4):273-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher ES, Wennberg JE. Health care quality, geographic variations, and the challenge of supply-sensitive care. Perspect Biol Med. 2003. Winter;46(1):69-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bundorf MK, Schulman KA, Stafford JA, Gaskin D, Jollis JG, Escarce JJ. Impact of managed care on the treatment, costs, and outcomes of fee-for-service Medicare patients with acute myocardial infarction. Health Serv Res. 2004. February;39(1):131-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chernew ME, Sabik L, Chandra A, Newhouse JP. Would having more primary care doctors cut health spending growth? Health Aff (Millwood). 2009. Sep-Oct;28(5):1327-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hurley J, Woodward C, Brown J. Changing patterns of physician services utilization in Ontario, Canada, and their relation to physician, practice, and market-area characteristics. Med Care Res Rev. 1996. June;53(2):179-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stano M. An analysis of the evidence on competition in the physician services markets. J Health Econ. 1985. September;4(3):197-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dartmouth Atlas of Musculoskeletal Health Care Working Group. The Dartmouth atlas of musculoskeletal health care. Chicago: AHA Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Effective care. 2016. http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/keyissues/issue.aspx?con=2939. Accessed 2018 Apr 4.

- 30.Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care Working Group. The Dartmouth atlas of health care. Chicago: AHA Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baicker K, Chandra A, Skinner JS. Geographic variation in health care and the problem of measuring racial disparities. Perspect Biol Med. 2005. Winter;48(1)(Suppl):S42-53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wennberg JE. Dealing with medical practice variations: a proposal for action. Health Aff (Millwood). 1984. Summer;3(2):6-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grytten J, Sørensen R. Practice variation and physician-specific effects. J Health Econ. 2003. May;22(3):403-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phelps CE. Welfare loss from variations: further considerations. J Health Econ. 1995. June;14(2):253-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brooks JM, Chrischilles EA. Heterogeneity and the interpretation of treatment effect estimates from risk adjustment and instrumental variable methods. Med Care. 2007. October;45(10)(Supl 2):S123-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brooks JM, Chrischilles EA, Landrum MB, Wright KB, Fang G, Winer EP, Keating NL. Survival implications associated with variation in mastectomy rates for early-staged breast cancer. Int J Surg Oncol. 2012;2012:127854. Epub 2012 Aug 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brooks JM, Chrischilles EA, Scott SD, Chen-Hardee SS. Was breast conserving surgery underutilized for early stage breast cancer? Instrumental variables evidence for stage II patients from Iowa. Health Serv Res. 2003. December;38(6 Pt 1):1385-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brooks JM, Cook E, Chapman CG, Schroeder MCA, Chrischilles E, Schneider KM, Kulchaitanaroaj P, Robinson J. Statin use after acute myocardial infarction by patient complexity: are the rates right? Med Care. 2015. April;53(4):324-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brooks JM, McClellan M, Wong HS. The marginal benefits of invasive treatments for acute myocardial infarction: does insurance coverage matter? Inquiry. 2000. Spring;37(1):75-90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fang G, Brooks JM, Chrischilles EA. A new method to isolate local-area practice styles in prescription use as the basis for instrumental variables in comparative effectiveness research. Med Care. 2010. August;48(8):710-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fang G, Brooks JM, Chrischilles EA. Comparison of instrumental variable analysis using a new instrument with risk adjustment methods to reduce confounding by indication. Am J Epidemiol. 2012. June 01;175(11):1142-51. Epub 2012 Apr 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse. 2016. https://www.ccwdata.org. Accessed 2018 Apr 4.

- 43.Wise JN, Daffner RH, Weissman BN, Bancroft L, Bennett DL, Blebea JS, Bruno MA, Fries IB, Jacobson JA, Luchs JS, Morrison WB, Resnik CS, Roberts CC, Schweitzer ME, Seeger LL, Stoller DW, Taljanovic MS. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® on acute shoulder pain. J Am Coll Radiol. 2011. September;8(9):602-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chrischilles E, Schneider K, Wilwert J, Lessman G, O’Donnell B, Gryzlak B, Wright K, Wallace R. Beyond comorbidity: expanding the definition and measurement of complexity among older adults using administrative claims data. Med Care. 2014. March;52(Suppl 3):S75-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000. December;53(12):1258-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hadley J, Waidmann T, Zuckerman S, Berenson RA. Medical spending and the health of the elderly. Health Serv Res. 2011. October;46(5):1333-61. Epub 2011 May 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greene WH. Econometric analysis. 5th ed. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tjur T. Coefficients of determination in logistic regression models—a new proposal: the coefficient of discrimination. Am Stat. 2009;63(4):366-72. [Google Scholar]

- 50.McFadden DL. Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In: Zarembka P, editor. Frontiers in econometrics. New York: Academic Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman J. The elements of statistical learning: data mining, inference, and prediction. Berlin: Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 52.The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Dartmouth Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Lebanon, NH: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/data/region/ [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schroeder MC, Robinson JG, Chapman CG, Brooks JM. Use of statins by Medicare beneficiaries post myocardial infarction: poor physician quality or patient-centered care? Inquiry. 2015. February 27;52:0046958015571131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brooks JM, Cook EA, Chapman CG, Kulchaitanaroaj P, Chrischilles EA, Welch S, Robinson J. Geographic variation in statin use for complex acute myocardial infarction patients: evidence of effective care? Med Care. 2014. March;52(Suppl 3):S37-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brooks JM, Tang Y, Chapman CG, Cook EA, Chrischilles EA. What is the effect of area size when using local area practice style as an instrument? J Clin Epidemiol. 2013. August;66(8)(Suppl):S69-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davison AC, Hinkley DV. Bootstrap methods and their application. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 57.DiCiccio TJ, Efron B. Bootstrap confidence intervals. Stat Sci. 1996;11(3):189-228. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peterson MG, Hollenberg JP, Szatrowski TP, Johanson NA, Mancuso CA, Charlson ME. Geographic variations in the rates of elective total hip and knee arthroplasties among Medicare beneficiaries in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992. December;74(10):1530-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bell JE, Leung BC, Spratt KF, Koval KJ, Weinstein JD, Goodman DC, Tosteson AN. Trends and variation in incidence, surgical treatment, and repeat surgery of proximal humeral fractures in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011. January 19;93(2):121-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Forte ML, Virnig BA, Kane RL, Durham S, Bhandari M, Feldman R, Swiontkowski MF. Geographic variation in device use for intertrochanteric hip fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008. April;90(4):691-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vitale MG, Krant JJ, Gelijns AC, Heitjan DF, Arons RR, Bigliani LU, Flatow EL. Geographic variations in the rates of operative procedures involving the shoulder, including total shoulder replacement, humeral head replacement, and rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999. June;81(6):763-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weinstein JN, Bronner KK, Morgan TS, Wennberg JE. Trends and geographic variations in major surgery for degenerative diseases of the hip, knee, and spine. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;Suppl Variation:VAR81-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]