Abstract

Context:

Better understanding of clinicians’ skill communicating with their patients, and of patients’ trust in clinicians, is necessary to develop culturally-sensitive palliative care interventions. Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and religiosity have been documented as factors influencing quality of communication and trust.

Objectives:

Explore associations of seriously-ill patients’ race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status and religiosity with patients’ ratings of the quality of clinicians’ communication and trust in clinicians.

Methods:

An observational analysis using baseline data from a multi-center cluster-randomized trial of a communication intervention. We enrolled consecutive patients with chronic, life-limiting illnesses (n=537) cared for by primary and specialty care clinicians (n=128) between 2014 and 2016 in outpatient clinics in Seattle, Washington. We assessed patient demographics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, income, and self-rated health status), Duke University Religion Index, Quality of Communication Scale, and Wake Forest Physician Trust Scale. We used probit and linear regression and path analyses to examine associations.

Results:

Patients providing higher ratings of clinician communication included those belonging to racial/ethnic minority groups (p=0.001), those with lower income (p=0.008), and those with high religiosity/spirituality (p=0.004). Higher trust in clinicians was associated with minority status (p=0.018), lower education (p=0.019), and clinician skill in communication (p<0.001).

Conclusions:

Contrary to prior studies, racial/ethnic minorities and patients with lower income rated communication higher and reported higher trust in their clinicians than white and higher income patients. More research is needed to identify and understand factors associated with quality communication and trust between seriously-ill patients and clinicians to guide development of patient-centered palliative care communication interventions.

Keywords: quality of communication, trust, race/ethnicity, serious illness, religiosity

Introduction

In an effort to improve quality of care for minority populations, the National Health Care Disparities Report recommends clinicians listen to patients, respect patients’ views, and respond to patient requests in a “culturally and linguistically appropriate manner.”1 The National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care similarly endorses culturally-sensitive, patient-centered care as a way to improve patient and family experiences and the quality of palliative care.2 Despite these recommendations to deliver culturally-appropriate care, with an emphasis on communication and trust between patients and clinicians that supports patients’ values and goals, the integration of these recommendations into clinical practice has not been easily achieved.3-6 Rather, patients from racial/ethnic minority groups describe lower trust in, and poorer communication with, their clinicians 7-13 with the exception of one study that found higher communication ratings by patients with non-white race and lower socioeconomic status (SES).14

Researchers have noted strong links between communication and trust: when communication is highly rated, patients and families report higher trust in their clinicians.9-11 There is also evidence that clinicians’ communication about religious or spiritual topics, in particular, can contribute to trust: patients have reported increased trust when their clinician asks about and respects their spiritual or religious beliefs.15-19 Finally, clinician-patient communication has implications for decision-making: when communication is rated highly by patients or their family members, their values, goals and preferences are more likely to be discussed, and they are more likely to be included in shared decision making11 with their clinician. Thus, an understanding of factors associated with quality communication and the development of trust between seriously-ill patients and their clinicians may enhance the development and implementation of culturally-sensitive palliative care interventions.

Building upon prior studies of patient-clinician communication, trust and the factors that influence patient’s perceptions of communication and trust, 9-16 we explored associations between race/ethnicity, SES and religiosity/spirituality of seriously-ill patients and their ratings of the quality of their clinicians’ communication (QOC) and their trust in these clinicians. For this study and following the practice of other researchers, SES was represented by education and income.12-13, 20 Consistent with the findings of prior research, we hypothesized that patients from racial/ethnic minority groups, those with less education and income, and those with higher religiosity/spirituality would provide lower ratings of their clinicians’ communication and report lower levels of trust.12-13,15-19 We also hypothesized that quality of communication would influence patients’ trust ratings, with more highly rated communication associated with higher levels of trust.9-13

Methods

Study Design

These analyses used baseline data from a cluster randomized trial of a “goals-of-care” communication intervention.21 The study was conducted with patients with serious illness who were being treated in outpatient settings in an academic and a community-based multi-hospital healthcare system, both in Seattle, Washington.21

Participants and Setting

Clinicians:

Eligible clinicians included physicians and nurse practitioners providing outpatient primary or specialty care. Clinicians were eligible for the study if they had 5 or more eligible patients in their panels. They were initially approached for recruitment by mail or e-mail, then received a follow-up phone call or in-person visit. Recruitment occurred between February 2014 and November 2015.

Patients:

Eligible patients were English-speaking and 18 years or older with serious illness for which they were receiving ongoing care (at least two visits over eighteen months) from participating clinicians in primary care (internal medicine, family practice, or geriatrics) or specialty care (cardiology, pulmonary, oncology, gastroenterology, or nephrology). To recruit patients with a likely median survival of approximately 2 years, we selected patients with cancer, chronic pulmonary disease, restrictive lung disease, pulmonary hypertension, cystic fibrosis, heart failure, cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, dialysis-dependent renal failure, Charlson comorbidity scores ≥6, aged 75+ with a chronic life-limiting illness, aged 90+, or hospitalization in the previous 18 months with a life-limiting diagnosis. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the two participating healthcare systems.

Consecutive eligible patients were recruited between March 2014 and May 2016, and were identified by study staff from the electronic health record and appointment logs. Patients were initially contacted with letters from their enrolled clinician and the study’s principal investigator, and then recontacted by study staff over the phone to confirm their interest. Nearly all enrollees (99%) completed baseline questionnaires at an in-person enrollment visit, with the remainder having enrollment visits by phone and returning questionnaires by mail.

Data Collection and Variables

Patient-reported data included demographic information (age, gender, race/ethnicity, levels of education and income, and self-rated health status); questions about religiosity/spirituality; ratings of the quality of their enrolled clinician’s communication; and questions about trust in their enrolled clinician. Information about clinicians (i.e., age, gender, race, specialty) was obtained by clinician self-report at the time of clinician enrollment.

Outcomes

Quality of communication (QOC):

Seven items from the QOC questionnaire (Appendix A) assessed patients’ ratings of their enrolled clinicians’ skill at end-of-life communication.22 From these, we selected a priori three items that seemed most relevant to the current study: (1) involving the patient in decisions about the treatments desired if the patient became too sick to communicate; (2) asking about the things in life that were important to the patient; and (3) asking about the patient’s religious beliefs. The patient rated the clinician’s performance from 0 (the very worst I could imagine) through 10 (the very best I could imagine), or indicated that the clinician had not performed the activity. Owing to the distribution of responses, we recoded the items into three-category ordinal variables: 0=activity not done; 1=imperfect performance (rating=0-9); 2=perfect performance (rating=10). Preliminary analysis (Appendix B) confirmed that a latent construct, measured with the three QOC items recoded to this 0-2 scale and constrained to scalar measurement invariance between dichotomized respondent groups related to four predictors of interest (race/ethnicity, education, income, and religiosity/spirituality; diagrams presented in Appendix B, Figures B1-B4), fit the observed data well, suggesting that associations between the predictors and this latent variable outcome could be legitimately evaluated.23-28

Trust:

Patients rated trust in their enrolled clinician with the short-form Wake Forest Trust-in-Physician Scale, a reliable (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.77) and valid 5-item scale (Appendix A).29 However, our sample’s responses to these 5 items (between 70% and 82% of respondents giving the response that indicated the highest level of trust) lacked sufficient variability to permit testing the items as indicators of a latent variable. Therefore, we used the fifth item as a single-item measure of overall trust: “All in all, you have complete trust in this doctor.” We dichotomized this variable: 0=less than complete trust, 1=complete trust.

Predictors.

Race/ethnicity:

Because our sample size was too small to compare individual racial/ethnic minority groups, we coded racial/ethnic minority status as a dichotomous predictor: 0=white non-Hispanic, 1=non-white and/or Hispanic. Analyses of individual minority groups generally supported this grouping (data not shown.)

SES:

We used self-reported patient educational attainment and average annual pre-tax household income for the last 3 years as measures of SES. When used as a predictor in regression models, education was modeled as an ordinal variable with seven categories; when used to establish measurement invariance of the quality-of-communication construct between education groups, education was dichotomized at the median, with patients at or below median forming one group (less than 4-year college degree) and those above median forming the other group (4-year college degree or higher). In regression models, income was modeled as an ordinal predictor with eight categories; when used to establish measurement invariance of the QOC construct between income categories, it was dichotomized at the median, with annual gross incomes of $36,000 or less constituting one group, and annual gross incomes above $36,000 the other.

Religiosity/Spirituality.

As a proxy measure for religiosity/spirituality, we adapted a single item from the Duke University Religion (DUREL) Index 30 (Appendix A): “My religious or spiritual beliefs are what really lie behind my whole approach to life.” This variable was recoded into two categories: patients were coded as being “very religious” if their response to the single item was “definitely true of me” (n=186) and “less than very religious” if their response was “does not apply to me, definitely not true, tends not to be true, unsure, or tends to be true” (n=350).

Potential Confounders.

We investigated three patient characteristics as potential confounders: patient age, gender, and self-rated health status (the SF131-34). The SF1 asks: “In general, would you say your health is: excellent, very good, good, fair, poor.” Clinician specialty was also tested as a potential confounder, modeled with four dummy indicators (internal medicine, cardiology, oncology, other), with family medicine as the reference group. A variable was defined as a confounder if its addition to a bivariate model containing only the predictor and outcome changed the estimated coefficient for the predictor by 10% or more.35-37

Data Analysis

We completed the following analyses: 1) preliminary confirmatory factor analyses testing a hypothesized latent QOC construct for uni-dimensionality and scalar measurement invariance between groups related to our predictors of interest; 2) regression models separately associating each predictor with each outcome, with adjustment for any confounders; and 3) path models that tested for mediation effects in the associations between the predictors, QOC and trust. In constructing a final path model, we began with a saturated model containing all of the variables of interest, using the following causal sequencing: (1) race/ethnicity as an exogenous variable, (2) education, (3) income, (4) religiosity/spirituality, (5) QOC, and (6) trust in clinician. From this saturated model, we eliminated paths in descending order of p-value until only paths with p<0.06 remained.

All models clustered patients under clinicians. Patients were excluded if they did not provide complete data on predictors, covariates, and trust. If they provided complete data except for QOC ratings, they were excluded from only the loadings of indicators for which they did not provide a rating.

Because all analyses included ordered categorical variables as outcomes, they were based on probit regression, estimated with mean- and variance-adjusted weighted least squares (WLSMV). However, models that included the latent QOC construct produced probit regression coefficients for the three QOC indicators, but linear regression coefficients for the construct regressed on predictors. The path analysis used theta parameterization. We used IBM SPSS Statistics Version 19 for descriptive statistics and Mplus Version 8.0 for confirmatory factor analysis, regression analysis, and path modeling. We interpreted p-values <0.05 to connote statistical significance, but retained one variable in the path diagram that was associated with a slightly higher value (p=0.056).

Results

Sample

Patients.

Nine hundred seventeen eligible patients were identified, and 537 enrolled (58.6% participation). The gender distribution of the patient sample (Table 1) was roughly equal; patients’ average age was 73.4 (SD = 12.7); 20.9% patients (n=112) identified with a racial/ethnic minority group. Of those who provided information, 22.0% (n=118) had no post-high school education; 25.2% (n=126) had average annual gross household income of $18,000 or less; and 45.6% (n=244) perceived themselves to be in poor or fair health.

Table 1.

Demographics: 537 Enrolled Patients

| Characteristic | Valid n | Statistica |

|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | 537 | |

| White non-Hispanic | 425 (79.1) | |

| Minority | 112 (20.9) | |

| White Hispanic | 6 ( 1.1) | |

| Black | 62 (11.5) | |

| Asian | 15 ( 2.8) | |

| Pacific Islander | 5 ( 0.9) | |

| Native American | 3 ( 0.6) | |

| Mixed | 21 ( 4.0) | |

| Female | 537 | 256 (47.7) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 537 | 73.4 (12.7) |

| Level of education | 536 | |

| 8th grade or less | 13 ( 2.4) | |

| Some high school | 32 ( 6.0) | |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 73 (13.6) | |

| Trade school or some college | 220 (41.0) | |

| 4-year college degree | 92 (17.2) | |

| Some graduate school | 24 ( 4.5) | |

| Graduate degree | 82 (15.3) | |

| Average annual pre-tax income | 500 | |

| None | 3 ( 0.6) | |

| $6,000 or less | 7 ( 1.4) | |

| $12,000 or less | 60 (12.0) | |

| $18,000 or less | 56 (11.2) | |

| $24,000 or less | 54 (10.8) | |

| $36,000 or less | 74 (14.8) | |

| $48,000 or less | 67 (13.4) | |

| More than $48,000 | 179 (35.8) | |

| Qualifying diagnoses | 537 | |

| Advanced cancer | 97 (18.1) | |

| Chronic lung disease | 52 ( 9.7) | |

| Heart failure | 34 ( 6.3) | |

| Liver failure | 3 ( 0.6) | |

| Renal failure | 22 ( 4.1) | |

| Other qualifying conditions | ||

| Age 75–89 w/chronic condition | 207 (38.5) | |

| Age 90+ | 36 ( 6.7) | |

| Hospitalization | 91 (16.9) | |

| Charlson score 6+ | 442 (82.3) |

Unless indicated otherwise, the statistics shown are the number and percentage of valid responses.

Clinicians.

Of the 128 clinicians who enrolled and were evaluated by the patients in the study (Table 2), 92.2% (n=118) were physicians and 7.8% (n=10) were nurse practitioners. The mean age of clinicians was 47.1 years (SD = 9.6), 53.9% (n=69) were female, and 77.3% (n=99) were white non-Hispanic. Clinicians from all eligible specialties participated and ranged from 13.3% (n=17) in cardiology to 27.3% (n=35) in internal medicine.

Table 2.

Demographics: 128 Clinicians with Enrolled Patients

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Type | |

| Physician | 118 (92.2) |

| Nurse Practitioner | 10 ( 7.8) |

| Specialty | |

| Family medicine | 30 (23.4) |

| Internal medicine | 35 (27.3) |

| Cardiology | 17 (13.3) |

| Oncology | 25 (19.5) |

| Other areaa | 21 (16.4) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White non-Hispanic | 99 (77.3) |

| Minority | 29 (22.7) |

| White Hispanic | 4 ( 3.1) |

| Black | 1 ( 0.8) |

| Asian | 19 (14.8) |

| Pacific Islander | 0 ( 0.0) |

| Native | 0 ( 0.0) |

| American | |

| Mixed | 5 ( 3.9) |

Pulmonology,gastroenterology,nephrology,or geriatrics

Religiosity/Spirituality

More than a third of patients were highly spiritual/religious (34.7%; Table 3). Substantially more racial/ethnic minority patients indicated that it was definitely true that their spiritual/religious beliefs lay behind their overall approach to life (51.8%, compared with 30.2% of white non-Hispanic patients).

Table 3.

Survey Responses: Religiosity/Spiritualitya

| n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Items and Response Options | White Non- Hispanic |

Racial/ethnic Minority |

TOTAL SAMPLE |

| My religious or spiritual beliefs are what really lie behind my whole approach to life | 424 | 112 | 536 |

| Definitely not true or does not apply | 128 (30.2) | 24 (21.4) | 152 (28.4) |

| Tends not to be true | 25 (5.9) | 3 (2.7) | 28 (5.2) |

| Unsure | 44 (10.4) | 6 (5.4) | 50 (9.3) |

| Tends to be true | 99 (23.3) | 21 (18.8) | 120 (22.4) |

| Definitely true | 128 (30.2) | 58 (51.8) | 186 (34.7) |

| If/When you are able, how often do you attend church or other religious meetings? | 421 | 112 | 533 |

| Never or does not apply | 189 (44.9) | 34 (30.4) | 223 (41.8) |

| Once a year or less | 51 (12.1) | 7 (6.3) | 58 (10.9) |

| A few times a year | 43 (10.2) | 18 (16.1) | 61 (11.4) |

| A few times a month | 32 (7.6) | 10 (8.9) | 42 (7.9) |

| Once a week | 75 (17.8) | 21 (18.8) | 96 (18.0) |

| More than once a week | 31 (7.4) | 22 (19.6) | 53 (9.9) |

| How often do you spend time in private religious activities, such as prayer, meditation or Bible study? | 421 | 112 | 533 |

| Rarely, never, or does not apply | 182 (43.2) | 31 (27.7) | 213 (40.0) |

| A few times a month | 35 (8.3) | 4 (3.6) | 39 (7.3) |

| Once a week | 17 (4.0) | 5 (4.5) | 22 (4.1) |

| Two or more times a week | 41 (9.7) | 8 (7.1) | 49 (9.2) |

| Daily | 101 (24.0) | 38 (33.9) | 139 (26.1) |

| More than once a day | 45 (10.7) | 26 (23.2) | 71 (13.3) |

| To what extent do your religious or spiritual beliefs influence your preferences for medical care | 419 | 112 | 531 |

| Not at all or does not apply | 287 (68.5) | 60 (53.6) | 347 (65.3) |

| Slightly | 23 (5.5) | 8 (7.1) | 31 (5.8) |

| Somewhat | 36 (8.6) | 11 (9.8) | 47 (8.9) |

| Quite a bit | 37 (8.8) | 16 (14.3) | 53 (10.0) |

| Completely | 36 (8.6) | 17 (15.2) | 53 (10.0) |

The numbers on the line stating each survey question represent the number of patients in the group identified in the column who gave valid responses to the question.

Quality of Communication

For all three QOC items, many patients reported that their clinicians had not addressed the specific aspect of communication being queried (Table 4). Among patients who gave valid responses, only 35.7% reported that their clinician had involved them in decisions about treatment preferences; 52.5% indicated that the clinician had asked them about things that were important in their life; and 16.8% reported that the clinician had inquired about their religious beliefs.

Table 4.

Survey Responses: Quality of Communication a

|

n (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Items and Response Options | White Non-Hispanic |

Racial/ Ethnic Minority |

Total Sample |

| How good is your doctor at… | |||

| Involving you in the decisions about the treatments you would want if you get too sick to speak for yourself? | 404 | 108 | 512 |

| Not done | 274 (67.8) | 55 (50.9) | 329 (64.3) |

| Imperfect performance | 70 (17.3) | 17 (15.7) | 87 (17.0) |

| Perfect performance | 60 (14.9) | 36 (33.3) | 96 (18.8) |

| Asking about the things in life that are important to you? | 400 | 109 | 509 |

| Not done | 196 (49.0) | 46 (42.2) | 242 (47.5) |

| Imperfect performance | 107 (26.8) | 16 (14.7) | 123 (24.2) |

| Perfect performance | 97 (24.3) | 47 (43.1) | 144 (28.3) |

| Asking you about your spiritual or religious beliefs? | 400 | 107 | 507 |

| Not done | 344 (86.0) | 78 (72.9) | 422 (83.2) |

| Imperfect performance | 33 (8.3) | 15 (14.0) | 48 (9.5) |

| Perfect performance | 23 (5.8) | 14 (13.1) | 37 (7.3) |

The numbers on the line stating each survey question represent the number of patients in the group identified in the column who gave valid responses to the question.

Racial/ethnic minority patients tended to rate their clinicians more highly than white non-Hispanic patients on their inquiries about religious beliefs (13.1% vs. 5.8% of the two groups giving their clinician a perfect score), and they were also less likely to indicate that their clinician had not broached topics related to their religious/spiritual beliefs (72.9% vs. 86.0%).

Trust in Clinicians

Overall, patients reported high trust in their clinicians, with patients providing the highest possible rating 71.2% to 81.4% of the time for individual items (Table 5). On the item measuring complete trust in the clinician, 78.4% gave the highest rating, compared with 0.4% giving the lowest rating.

Table 5.

Survey Responses: Trusta

| n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Items and Response Options | White | Racial/ethnic | TOTAL |

| Non-Hispanic | Minority | SAMPLE | |

| Sometimes this doctor cares more about what is convenient for him/her than about your medical needs | 422 | 111 | 533 |

| 0 (strongly agree) | 4 ( 0.9) | 1 ( 0.9) | 5 ( 0.9) |

| 1 | 5 ( 1.2) | 1 ( 0.9) | 6 ( 1.1) |

| 2 | 15 ( 3.6) | 4 ( 3.6) | 19 ( 3.6) |

| 3 | 54 (12.8) | 15 (13.5) | 69 (12.9) |

| 4 (strongly disagree) | 344 (81.5) | 90 (81.1) | 434 (81.4) |

| This doctor is extremely thorough and careful | 422 | 112 | 534 |

| 0 (strongly disagree) | 2 ( 0.5) | 1 ( 0.9) | 3 ( 0.6) |

| 1 | 4 ( 0.9) | 1 ( 0.9) | 5 ( 0.9) |

| 2 | 13 ( 3.1) | 2 ( 1.8) | 15 ( 2.8) |

| 3 | 67 (15.9) | 20 (17.9) | 87 (16.3) |

| 4 (strongly agree) | 336 (79.6) | 88 (78.6) | 424 (79.4) |

| You completely trust this doctor’s decisions about which medical treatments are best for you | 423 | 112 | 535 |

| 0 (strongly disagree) | 0 ( 0.0) | 2 ( 1.8) | 2 ( 0.4) |

| 1 | 12 ( 2.8) | 0 ( 0.0) | 12 ( 2.2) |

| 2 | 27 ( 6.4) | 4 ( 3.6) | 31 ( 5.8) |

| 3 | 85 (20.1) | 15 (13.4) | 100 (18.7) |

| 4 (strongly agree) | 299 (70.7) | 91 (81.3) | 390 (72.9) |

| This doctor is totally honest in telling you about all of the different treatment options available for your condition | 419 | 112 | 531 |

| 0 (strongly disagree) | 3 ( 0.7) | 1 ( 0.9) | 4 ( 0.8) |

| 1 | 11 ( 2.6) | 4 ( 3.6) | 15 ( 2.8) |

| 2 | 32 ( 7.6) | 3 ( 2.7) | 35 ( 6.6) |

| 3 | 80 (19.1) | 19 (17.0) | 99 (18.6) |

| 4 (strongly agree) | 293 (69.9) | 85 (75.9) | 378 (71.2) |

| All in all, you have complete trust in this doctor | 424 | 112 | 536 |

| 0 (strongly disagree) | 1 ( 0.2) | 1 ( 0.9) | 2 ( 0.4) |

| 1 | 10 ( 2.4) | 1 ( 0.9) | 11 ( 2.1) |

| 2 | 24 ( 5.7) | 4 ( 3.6) | 28 ( 5.2) |

| 3 | 65 (15.3) | 10 ( 8.9) | 75 (14.0) |

| 4 (strongly agree) | 324 (76.4) | 96 (85.7) | 420 (78.4) |

The numbers on the line stating each survey question represent the number of patients in the group identified in the column who gave valid responses to the question.

Associations between Predictors and Outcomes

Three of the four predictors were significantly associated with the latent quality-of-communication construct (Table 6). Patients who rated their clinicians’ communication significantly more highly than did their counterparts included those belonging to racial/ethnic minority groups (b=0.408, p=0.001), those with lower income (b=−0.065, p=0.008), and those who were very religious (b=0.279, p=0.004). Religiosity had a particularly strong association with the QOC item specifically rating clinicians’ inquiries about the patient’s religious/spiritual beliefs (b=0.595, p<0.001), a weaker association with the item rating clinicians’ involvement of the patient in decisions about treatments desired if the patient became unable to communicate (b=0.273, p=0.016), and a non-significant association with clinicians’ inquiries about the things in life that were important to the patient (b=0.082, p=0.444). Patients’ level of education was not associated with communication quality.

Table 6.

Associations of Predictors with the Quality-of-Communication Constructa

| Predictor | n | bb | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Racial/ethnic minorityc | 533 | 0.408 | 0.001 | 0.171, 0.645 |

| Educationc | 532 | −0.029 | 0.393 | −0.096, 0.038 |

| Incomeb | 496 | −0.065 | 0.008 | −.114,−0.017 |

| Religiosity/spiritualitye,f | 532 | 0.279 | 0.004 | 0.090, 0.468 |

The QOC construct was a latent variable measured with three 3-category ordered categorical variables, based on a clustered regression model, estimated with weighted mean- and variance-adjusted least squares (WLSMV). Covariate adjustment was made for any variable that changed the coefficient for the predictor by 10% or more when added to the bivariate model.

Because the latent construct is a normally distributed continuous variable, the coefficients for the construct regressed on the exogenous predictors are linear regression coefficients. (Coefficients for the three categorical indicators regressed on the latent construct were probit regression coefficients, but they are not displayed in the table.)

Adjusted for patient age

Adjusted for patient age and clinician specialty

Unadjusted model; no confounders

The model regressing the QOC construct on religiosity/spirituality produced poor fit to the data (p for the x2 test of fit = 0.0001). Alternative models regressing the separate QOC items on religiosity/spirituality showed significant associations of religiosity/spirituality with two items: involving the patient in treatment decisions (b=0.273, p=0.016) and discussing religious/spiritual beliefs (b=0.595, p<0.001), but not with the third item: discussing things that were important to the patient (b=0.082, p=0.444).

Significant predictors of higher ratings of overall trust (Table 7) were racial/ethnic minority status (b=0.405, p=0.018), lower education (b=−0.103, p=0.019) and higher ratings of clinician quality of communication (b=0.470, p<0.001). Neither income nor religiosity were significantly associated with trust.

Table 7.

Associations of Predictors with Patients’ Overall Trust in Cliniciana

| Predictor | n | bb | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Racial/ethnic minorityc | 536 | 0.405 | 0.018 | 0.070, 0.739 |

| Educationd | 534 | −0.103 | 0.019 | −0.190,−0.017 |

| Incomee | 498 | −0.028 | 0.459 | −0.101, 0.046 |

| Religiosity/spiritualityf | 535 | 0.049 | 0.709 | −0.208, 0.305 |

| Clinician’s quality of communicationg | 537 | 0.470 | <0.001 | 0.289, 0.652 |

The association between each predictor and the single-item measure of overall trust was tested with a clustered probit regression model, estimated with weighted mean- and variance-adjusted least squares (WLSMV). Covariate adjustment was made for any variable that changed the coefficient for the predictor by 10% or more when added to the bivariate model.

Probit regression coefficient for the trust item regressed on the predictor.

Adjusted for confounding by patient age

Adjusted for confounding by patient age and self-reported health status

Adjusted for confounding by patient age, gender, and self-reported health status, and by clinician specialty

Adjusted for confounding by patient gender

No confounders; bivariate model; latent quality-of-communication construct measured with three 3-category ordered categorical variables.

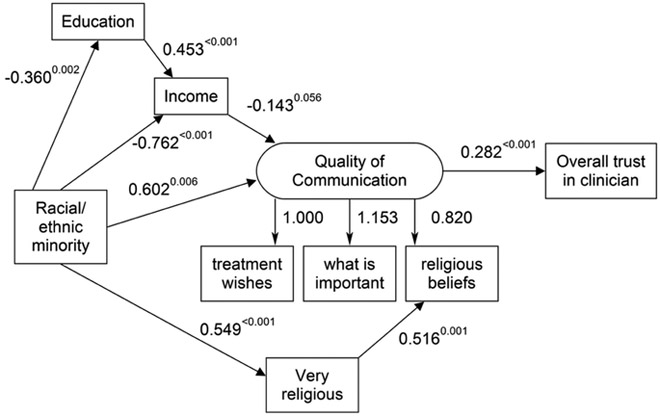

Quality of Communication and Trust: Path Model

A path model (Figure 1) pointed to positive effects of racial/ethnic minority status on the quality of clinicians’ communication with their patients, and these effects were both direct and indirect through patients’ education, income, and religiosity/spirituality. In addition to a significant positive direct effect (b=0.602, p=0.006) of race/ethnicity, there was also a non-significant positive indirect effect through education and income (b=0.133, p=0.052), which increased the total effect (b=0.735, p=0.001). On average, minority patients had significantly lower education and income, and patients with lower income rated their clinician more highly on quality of communication. The effect of religiosity/spirituality was specifically on the aspect of communication that involved clinicians’ inquiring about patients’ religious beliefs; people who were very religious (a characteristic more common among racial/ethnic minority patients) rated their clinicians significantly more highly on communication about religious beliefs than did those who were less religious (b=0.516, p=0.001).

Figure 1. Path Model of the Effects of Patient Race, Education, Income, Religiosity/Spirituality on Clinicians’ Skill at End-of-Life Communication and Patients’ Overall Trust in the Cliniciana.

a Model based on probit regression, estimated with weighted least squares with mean and variance adjustment (WLSMV); unstandardized coefficients with theta parameterization; positive coefficients indicate that the predictor and outcome rise and fall together, whereas negative coefficients indicate that an increase in the predictor contributes to a decrease in the outcome and vice versa; and larger coefficients indicate that a 1-unit increase in the predictor has a greater effect on the outcome than does a smaller coefficient; p-value for each structural coefficient shown as superscript next to the coefficient. X2 test of model fit: X2 = 18.796, 17 df, p=0.3404.

Statistically significant total effect of racial/ethnic minority status on quality of communication (b=0.735, p=0.001) included a significant direct effect (b=0.602, p=0.006), with an additional indirect effect through education and income, which was substantial, but statistically non-significant (b=0.133, p=0.052). There was also a significant indirect effect of racial/ethnic minority status on the religious-beliefs indicator of the quality-of-communication construct, through religiosity (0.886, p<0.001).

Statistically significant total effect of racial/ethnic minority status on trust (b=0.208, p=0.006), which was entirely indirect through education, income, and quality of communication.

Racial/ethnic minority status also had a significant positive effect on patients’ trust in their clinicians, with the effect being entirely indirect, through the clinician’s effectiveness at communication with the patient. The indirect effects of race/ethnicity on QOC were carried over to the trust outcome, thereby raising the overall indirect effect on trust: b=0.170, p=0.017 without the indirect effects through education and income; b=0.208, p=0.006 when the indirect effects through education and income were included.

Discussion

In this examination of the association between patients’ race/ethnicity, SES and religiosity/spirituality and their ratings of the quality of their clinicians’ communication and their trust in these clinicians, our findings contrasted with prior research with populations with serious illness 6-13 that showed that minority race/ethnicity and lower SES were associated with higher communication ratings. We found that racial/ethnic minority status had both direct and indirect positive effects on quality of communication, for a significant positive total effect with education and income serving as mediators. These unexpected results highlight the complexities of constructs of race, ethnicity, and SES, and the variables of influence these factors may have on outcomes such as quality of communication. Further research is needed to explore the influence on study outcomes of the different methods used to measure quality of communication between patients and clinicians.11-13,15, 22

Several possible explanations for our findings exist. A recent national study of older decedents examining bereaved family members’ ratings of the quality of end-of-life care found that racial disparities, described previously in a number of quality measures, were no longer present.38 This reduction in disparities may be attributed to clinicians becoming more aware of the role of their implicit personal biases on racial disparities in care, 39 and intentional efforts to improve their communication with minority patients. Disparities in communication and palliative care may actually be decreasing over time, although based on existing studies it is unclear whether care is improving for minorities or worsening for white non-Hispanics, or both.38 Another possible explanation may be related to patients’ prior experiences of disparities: patients with lower income, lower education, and non-white race may have developed lower expectations for their overall healthcare experience and the patient-clinician communication that is a part of that experience.1,6 Of note, our finding that non-white race and lower SES were associated with higher communication ratings has been reported in at least one other study conducted with a different sample, but in the same geographic location as our study.14 This may suggest that associations of race and SES with patients’ ratings of clinician communication and of their trust in the clinicians differ by region – a possibility that should be explored in future research.

We also found that religiosity/spirituality served as a mediator between race/ethnicity and quality of communication, but its impact was limited to one specific aspect of communication: higher ratings of the clinician’s inquiries about the patient’s religious beliefs. High religiosity/spirituality had a positive association with the QOC item specifically related to conversations about religious/spiritual beliefs. Racial/ethnic minority patients were more likely to be “very religious,” and such patients tended to rate their clinicians more highly on their inquiries about religious beliefs. Our finding that higher religiosity/spirituality was associated with higher communication ratings reinforces the importance of integrating patients’ religiosity/spirituality into efforts to enhance communication, particularly for highly religious patients.17-19,40

Participants in this study reported a high level of trust in their clinicians on all items from the trust questionnaire with 78% strongly agreeing that their clinicians were completely trustworthy. Consistent with our hypothesis, there was a significant positive association between clinicians’ skill in communicating with patients and patients’ overall trust in the clinician. A path model suggested that the association of demographic characteristics with trust was entirely mediated by the quality of communication. It has been noted that trust is formed from relationships between clinicians and patients over time during a patient’s serious illness diagnosis and that relationships take time to develop.9-11, 41-44 We did not collect information regarding the length of the patient’s relationship with the clinician and were, therefore, unable to explore whether this affected reported levels of trust. In future studies investigating the quality of communication and trust among patients with serious illness, the amount of time from the patient’s diagnosis of illness and the length of relationship with their clinician will be important factors to consider.

Several limitations of this study are worth noting. First, our sample sizes for specific racial/ethnic groups precluded our investigating differences between them, allowing us to only compare non-Hispanic whites vs. combined minorities. In addition, our results do not reflect the experiences of non-English speaking patients. Future studies should explore differences among specific minority groups and incorporate non-English speaking patients. Second, selection bias could have influenced our findings. For example, patients who agreed to enroll in this study may have been systematically higher on trust than was true for patients who chose not to participate.45 Third, patients in this study were identified and recruited from one geographic area, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Relationships between quality of communication, trust, and religiosity/spirituality could be significantly different in other regions.46 Finally, these analyses were cross-sectional and exploratory. The associations reported in the regression models do not imply causality and need to be explored further. However, our path model of a specific hypothesis about causal associations suggested that this causal hypothesis is at least plausible, given these data.

In summary, racial/ethnic minority status was consistently and positively associated with higher ratings of the quality of patient-clinician communication during care for serious illness. We identified significant associations between minority race/ethnicity and higher ratings of the quality of communication among patients with serious illness but with associations that were opposite those originally hypothesized. Patients’ ratings of clinicians’ skill in communicating with patients about issues relevant to end-of-life care was directly associated with patients’ trust in these clinicians. Our unexpected findings call attention to the complexities that underlie racial/ethnic identities as well as SES, and the variable influence they may have on outcomes such as quality of communication and trust. These complexities include the way in which we measure constructs such as “quality of communication,”11-13, 15, 22 as well as potential changes over time in this communication.33, 34 Since quality of patient-clinician communication 47,48 is an important modifiable factor that may decrease health care disparities, the ability to measure and understand influences on this construct is important. Research exploring the factors that facilitate high quality communication between clinicians and minority patients could improve our ability to provide more culturally-sensitive palliative care, thus informing efforts to reduce healthcare disparities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank Tori Ly for her contributions to the data collection, as well as the patients and clinicians who participated in this study.

Funding: Research reported in this article was supported by the National Institute of Health, National Heart, Blood and Lung Institute under award number T32 HL125195 and by the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), Grant #IH-12-11-4956. Dr. Sharma is supported by an American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant (MRSG 14-058-01-PCSM).The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures/Conflicts of interest: None of the authors have any financial conflicts of interest.

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01933789

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.2014 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report. Executive Summary. April 2015. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD: Accessed on June 15, 2016 at: http://www.ahrg.gov/research/findings/nhgrdr/nhgdr14/exsumm.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 3rd Edition. Retrieved on September 15, 2017. at http://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/ncp/. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Houston TK, Allison JJ, Sussman M, Horn W, Holt CL, Trobaugh J, et al. Culturally Appropriate Storytelling to Improve Blood Pressure: A Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:77–84. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-2-201101180-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnstone K, Kanitsaki O. Ethics and advance care planning in a culturally diverse society. J Transcultural Nurs 2009;20(4): 405–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans B & Ume E Psychosocial, cultural and spiritual health disparities in end-of-life and palliative care: Where we are and where we need to go. Nurs Outlook. 2012; 60: 370–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine: Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2002. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Racial Johnson K. and Ethnic Disparities in Palliative Care. J Pall Med 2013; 16(11): 1329–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connors AF Jr, Dawson NV, Desbiens NA et al. SUPPORT article principal investigators. A Control Trial to Improve Care for Seriously III Hospitalized Patients. JAMA 1995; 274:1591–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doescher M Saver B, Franks P, Fiscella K.Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Perceptions of Physician Style and Trust. Arch Fam Med 2000; 9:1156–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kao AC, Green DC, Zaslavsky AM, Koplan JP, Cleary PD. The relationship between method of physician payment and patient trust. JAMA. 1998;280:1708–1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peek M, Gorawara-Bhat R, Quinn M et al. Patient Trust in Physicians and Shared Decision Making among African-americans with Diabetes. J Health Comm 2013; 28(6); 616–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willems S, De Maesschalck S, Deveugele M, Derese A, DeMaeseneer J: Socio-economic status of the patient and doctor-patient communication: Does it make a difference? Patient Educ Couns 2005;56:139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siminoff LA, Graham GC, Gordon NH: Cancer communication patterns and the influence of patient characteristics: Disparities in information-giving and affective behaviors. Patient Educ Couns 2006;62:355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Long AC, Engelberg RA, Downey L, et al. Race, Income, and Education: Associations with Patient and Family Ratings of End-of-Life Care and Communication Provided by Physicians in Training. J Pall Med 2014; 17:435–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan SH, Gandek B, Greenfield S, Rogers W, Ware JE. Patient and visit characteristics related to physicians’ participatory decision-making style. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care 1995;33:1176–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benjamins M Religious Influences on Trust in Physicians and the Health Care System. Inti J Psychiatry Med 2006; 36(1): 69–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al Padela, Gunter K, Killawi A, Heisler M. Religious Values and Healthcare Accommodations: Voices from the American Muslim Community. J Gen Inter Med 2012;27(6):708–715.doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1965-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ehman JW, Ott BB, Short TH, Ciampa RC, Hansen-Flaschen J. Do Patients Want Physicians to Inquire About Their Spiritual or Religious Beliefs If They Become Gravely Ill?. Arch Intern Med 1999;159(15):1803–1806. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.15.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koenig HG. Spirituality in Patient Care: Why, How, When, and What. Philadelphia, PA, Templeton Foundation Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oakes M Measuring Socioeconomic Status. Office of Behavioral & Social Sciences Research. http://www.esourceresearch.org/eSourceBook/MeasuringSocioeconomicStatus/10AuthorBiography/tabid/895/Default.aspx. Accessed June 20, 2018.

- 21.Curtis JR, Downey L, Back AL, Nielsen EL, Paul S, Lahdya AZ, Treece PD, Armstrong P, Peck R, Engelberg RA. A patient and clinician communication-priming intervention increases patient-reported goals-of-care discussions between patients with serious illness and clinicians: A randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med 2018. (epub ahead of print, May 28, 2018.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engelberg R, Downey L, Curtis JR. Psychometric characteristics of a quality of communication questionnaire assessing communication about end-of-life care. J Pall Med 2006;9(5):1086–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meredith W, Teresi J. An essay on measurement and factorial invariance. Med Care 2006;44(11, Suppl 3): S69–S77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van de Schoot R, Lugtig P, Hox J. Developmentrics: a checklist for testing measurement invariance. European J Develop Psych 2012;9(4):486–492. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McIntosh CN. Strengthening the assessment of factorial invariance across population subgroups: a commentary on Varni et al. (2013). Quality of Life Res 2013;22:2595–2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edwards JR, Bagozzi RP. On the nature and direction of relationships between constructs and measures. Psych Meth 2000;5(2):155–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Byrne BM, van de Vijver JRF. Testing for measurement and structural equivalence in large-scale cross-cultural studies: addressing the issue of nonequivalence. Inter J Test 2010; 10:107–132. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taciano L, Milfont RF. Testing measurement invariance across groups: applications in cross-cultural research. Inter J Psych Res 2010;3(1):2011–2084. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dugan E, Trachtenberg F, Hall M. Development of abbreviated measures to assess patient trust in a physician, a health insurer, and the medical profession. BMC Health Services Research 2005: 5:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koenig HG, Büssing A. The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL): a five-item measure for use in epidemological studies. Religions 2010;1:78–85. [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeSalvo KB, Fisher WP, Tran K et al. Assessing measurement properties of two single-item general health measures. Qual Life Res 2006;15(2):191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Macias C, Gold PB, Ongur D, Cohen B, Panch T. Are single-item global ratings useful for assessing health status? J Clin Psych Med Settings 2015;22(4):251–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mavaddat N, Kinmonth AL, Sanderson S, et al. What determines Self-Rated Health (SRH)? A cross-sectional study of SF-36 health domains in the EPIC-Norfolk cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:800e806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McFadden E, Luben R, Bingham S et al. Social inequalities in self-rated health by age: crosssectional study of 22,457 middle-aged men and women. BMC Public Health. 2008. July 8;8:230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Modeling Greenland S. and variable selection in epidemiologic analysis. Amer J Pub Health 1989;79(3):340–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mickey RM, Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. American Journal of Epidemiology 1989; 129:125–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Muller K. Applied Regression Analysis and Other Multivariable Models. 2nd ed. Boston: PWS-Kent Publishing Company; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharma RK, Freedman VA, Mor V, Kasper JD Gozalo P Teno JM. Association of Racial Differences with End-of-Life Care Quality in the United States. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177(12): 1858–1860. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and Implicit bias: How Doctors may unwittingly perpetuate healthcare disparities. J Gen Intern Med 2013; 28:1504 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2441-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the Quality of Spiritual Care as a Dimension of Palliative Care: The Report of the Consensus Conference. J Pall Med 2009; 12(10): 885–904. doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2009.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hammond WP. Psychosocial correlates of medical mistrust among African American men. Am J Community Psychol 2010: 45: 87–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watkins YJ, Bonner GJ, Wang E, et al. Relationship among trust in physicians, demographics, and end-of-life treatment decisions made by African American dementia caregivers. J Hosp Pall Nurs 14: 238–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mechanic D, Meyer S. (2000). Concepts of trust among patients with serious illness. Soc Science Med 51: 657–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Croker JE, Swancutt DR, Roberts MJ, et al. Factors affecting patients’ trust and confidence in GPs: evidence from the English national GP patient survey. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002762. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lavrakas PJ. Encyclopedia of survey research methods. SAGE Publications Ltd, Thousand Oaks, CA, 2008. doi: 10.4135/9781412963947. [Google Scholar]

- 46.The Religious Landscape Study, 2014. Pew Research Center.Retrieved on June 5, 2017. at http://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/racial-and-ethnic-composition/.

- 47.Tulsky JA, Beach MC, Butow PN, et al. A Research Agenda for communication between health care professionals and patients living with serious illness. JAMA. 2017; 177(9): 1361–1366. doi: 10.100/jamainternmed.2017.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sinuff T, Dodek P, You JJ, et al. Improving End-of-Life communication and decision making: the development of a conceptual framework and quality indicators. J Pain Sym Man 2015; 49(6): 1070–1080. doi: http://dx/doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.