Abstract

Sporotrichosis is a human and animal disease caused by dimorphic pathogenic species of the genus Sporothrix. We report a dramatic presentation of Sporothrix brasiliensis infection, with destruction of the nasal septum, soft palate, and uvula of an HIV-infected woman. She was successfully treated with amphotericin B deoxycholate followed by itraconazole. Sporotrichosis remains a neglected opportunistic infection in patients with AIDS and awareness of this potentially fatal infection is of utmost importance.

Keywords: Hard palate, HIV infection, Nasal septal perforation, Sporotrichosis, Sporothrix brasiliensis

1. Introduction

Sporotrichosis, traditionally known as ‘rose-handlers’ disease’, is a human and animal disease caused by dimorphic fungal pathogenic species of the genus Sporothrix, such as Sporothrix schenckii sensu stricto and Sporothrix brasiliensis [1]. In Brazil, the disease has first been described in 1907 by Lutz and Splendore [2] and has long been recognized as endemic in some areas of the country [3]. Sporotrichosis is classically acquired through traumatic inoculation into skin or mucosa of fungal elements while handling soil, plants, organic matter, and decaying vegetation contaminated with fungal mycelia or conidia. In the last two decades, an unprecedented epidemic of sporotrichosis linked to zoonotic transmission of S. brasiliensis from scratches, bites, or simply contact with diseased cats has been reported in Brazil, initially in Rio de Janeiro state, but further expanding to other regions [4], [5].

Sporotrichosis most frequently presents in a fixed cutaneous or as a lymphocutaneous form, since infection may track along dermal lymphatics leading to a nodular lymphangitis. A much smaller number of cases occurs as cutaneous disseminated sporotrichosis (without extrategumentary disease) and as disseminated sporotrichosis (with extracutaneous and/or multi-organ involvement), most notably in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected subjects [1]. These cases require immediate diagnosis and management to reduce morbidity and mortality. We present herein an unusual case of sporotrichosis of the mucosal surfaces of the mouth and nose that led to palate ulcer, uvular destruction and nasal septum perforation in an HIV-infected woman.

2. Case

A 40-year-old woman presented in August 10th, 2017 (day 0), with a two-month history of 5 kg weight loss, headaches and purulent rhinorrhea. Antimicrobial agents, such as azithromycin, levofloxacin, and clindamycin had been empirically prescribed at another facility, with no clinical response. The patient was born and resided in the city of Rio de Janeiro, worked as a sales representative, and had a diagnosis of HIV infection made 17 years previously during prenatal care. She had a history of zidovudine-induced myelotoxicity and tenofovir-related renal toxicity, and alternated periods of adherence to antiretroviral therapy with long periods of losses to follow up. She had no history of smoking, alcohol abuse or illicit drug use. Three years previously, a lymphocutaneous form of sporotrichosis had been successfully treated with a 12-month course of oral itraconazole at a dose of 200 mg/d. Between 2013 and 2014 she sheltered at home a total of 13 abandoned cats which she collected from the streets.

Antiretroviral therapy was then resumed with a new regimen consisting of dolutegravir and ritonavir-boosted darunavir, as well as prophylaxis against opportunistic infections. Her illness, however, progressed to oropharyngeal pain, dysphagia, a non-productive cough and severe odynophagia. She was then admitted to our hospital (day +30).

Clinical examination revealed an afebrile and severely undernourished patient with a right forearm scar of the previously treated lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis (Fig. 1). Examination of the oral cavity revealed a large circumoval, painful ulcer over the hard palate that was greater in the rostrocaudal axis (approximately 3 cm). The lesion had a cobblestone, friable surface and was surrounded by a rim of erythema (Fig. 2). Another large lesion could be seen at the edge of the soft palate, involving both palatoglossal arches and the uvula, which were partially destructed (Fig. 3). Both lesions drained a purulent discharge. Anterior rhinoscopy revealed a single large nasal cavity with destruction of the cartilaginous septum and right inferior turbinate.

Fig. 1.

Scar of the previously treated lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis over the right forearm.

Fig. 2.

A large circumoval, painful ulcer over the hard palate. The lesion was greater in the axial plane, had a cobblestone, friable surface and was surrounded by a rim of erythema.

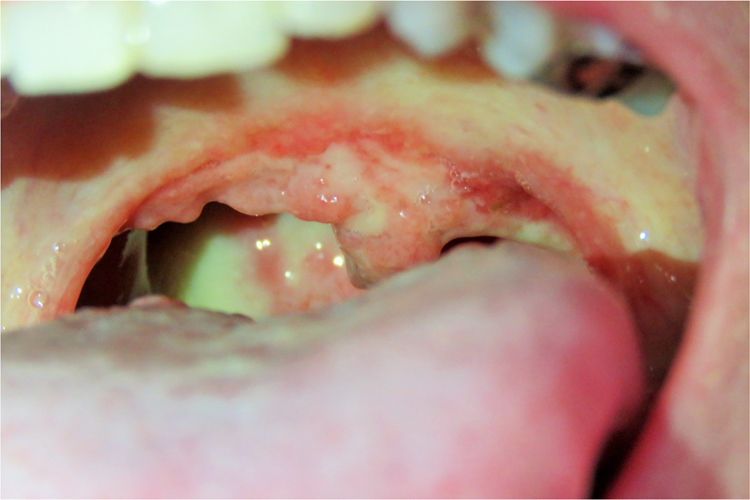

Fig. 3.

A large, painful lesion at the edge of the soft palate, involving both palatoglossal arches and the uvula, which were partially destructed.

Laboratory evaluations were remarkable for a normochromic, normocytic anaemia with a hemoglobin of 10.7 g/dl (12–15.5 g/dl), a CD4 cell count of 05 cells/mm3 and a plasma HIV viral load of 75,061 (4,87 log). Serologic tests for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and syphilis were negative. Sputum samples were acid-fast bacilli negative. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the nasal sinuses (Fig. 4) revealed destruction of the anterior aspect of the nasal septum, the anterior aspect of the right medial and inferior turbinates, and the medial wall of the right maxillary sinus. A CT scan of the chest showed centrilobular nodules in the lateral segment of the right middle lobe, associated with bronchial mucoid impaction. The overall aspect suggested an infectious process with bronchogenic spread. There was no evidence of abdominal or central nervous system disease.

Fig. 4.

Coronal (A) and axial (B) CT scans of the nasal sinuses reveal destruction of the anterior aspect of the nasal septum, the anterior aspect of the right medial and inferior turbinates, and the medial wall of the right maxillary sinus.

Biopsies of the oral lesions were performed as a diagnostic procedure. Histopathological analyses yielded an architectural pattern of a chronic granulomatous inflammatory reaction, with the presence of Langhans giant cells and associated with a lymphoplasmacytic and neutrophilic infiltrate. Grocott methenamine silver stain unmasked spherical and cigar-shaped yeastlike structures, which were suggestive of Sporothrix spp. Biopsy samples were also sent for fungal cultures on Sabouraud dextrose agar. These eventually resulted positive for Sporothrix spp. Therefore, a diagnosis of extracutaneous sporotrichosis with oronasal mucosal destructive lesions, and probable pulmonary sporotrichosis, was made.

Treatment was initiated (day +40) with a daily regimen of amphotericin B deoxycholate at a daily dose of 35 mg/Kg. After a few days, a paradoxical worsening of pain and overall clinical status was observed, and the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. Pain was controlled with regular intravenous tramadol and dipyrone. When a cumulative dose of 1 g was reached (day +70), oral itraconazole 400 mg/d was substituted for amphotericin B deoxycholate. The patient slowly improved and full remission of the oronasal ulcers was recorded (Fig. 5). Two months after admission (day +90), she was discharged for ambulatory follow up. Three months later the CD4 cell count was 106 cells/mm3 and the plasma HIV viral load was below detection limits. The oronasal destructive lesions left a sequelae of hyperrhynolalia and a retraction of the right ala nasi. One year after treatment, the patient was still on itraconazole 400 mg/d, had no signs of relapse, and was awaiting nasal reconstructive surgery (Fig. 6).

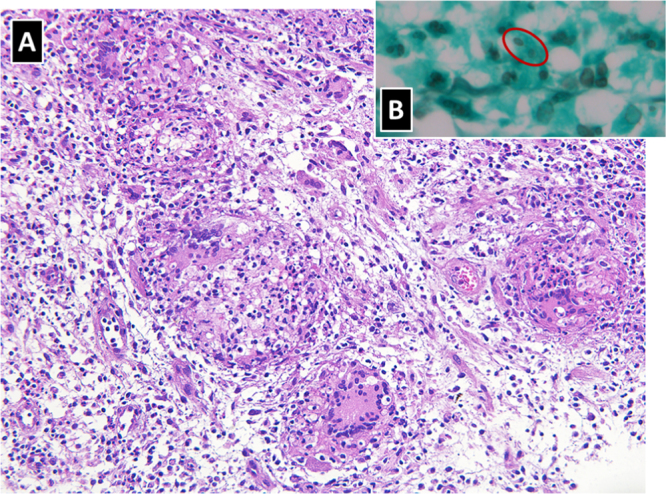

Fig. 5.

Histopathological analyses yielded (A) an architectural pattern of a chronic granulomatous inflammatory reaction, with the presence of Langhans giant cells and associated with a lymphoplasmacytic and neutrophilic infiltrate (original magnification 100×); (B) Grocott methenamine silver stain unmasked spherical and cigar-shaped yeastlike structures, which were suggestive of Sporothrix spp (original magnification 400×).

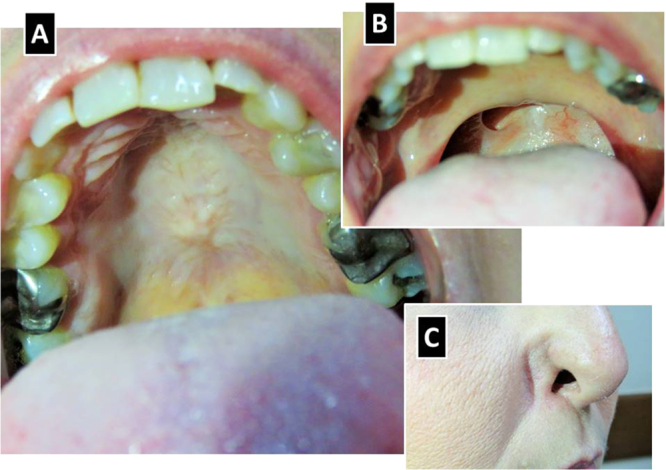

Fig. 6.

Clinical images of the patient 1 year after treatment. Resolution of the hard (A) and soft (B) palate ulcers, full destruction of the uvula, and retraction of the right ala nasi (C).

Additional molecular analyses were performed on the Sporothrix spp. isolate through a PCR reaction using specific primers for species identification, as previously reported [6]. In summary, by using a panel of novel markers, based on calmodulin gene sequences for the large-scale diagnosis and epidemiology of clinically relevant members of the Sporothrix genus, the genomic DNA of the isolate obtained from the patient reacted exclusively with the primers specific to S. brasiliensis. No DNA sequence is generated with this method [6].

3. Discussion

In recent years there has been an increased recognition of the burden of disseminated sporotrichosis among HIV-infected subjects. Sporotrichosis in HIV-infected patients presents with a higher incidence of disseminated disease, a higher frequency of hospital admissions and deaths [7], [8]. However, there is still a scarcity of data on the association between HIV and sporotrichosis [8]. A recent systematic review highlighted the features of HIV-related sporotrichosis among 58 patients, 33 (56,9%) of whom from Brazil [8]. Patients were predominantly male (84,5%) with a mean CD4 cell count of 97 cells/mm3. A relatively low CD4 cell count was strongly associated with disseminated and cutaneous disseminated forms of the disease. The majority of cases reported from Brazil were due to zoonotic transmission by infected cats. The management of sporotrichosis in an HIV-infected patient may prove to be exceedingly difficult [9], [10], [11].

We report herein a dramatic presentation of sporotrichosis that led to destruction of the nasal septum, soft palate, and uvula, with retraction of the right ala nasi of an HIV-infected woman. Our patient presented with an exceedingly rare manifestation of sporotrichosis three years after being successfully treated for a typical lymphocutaneous form of the disease with a 12-month course of itraconazole. It is unclear whether the novel presentation represented a new infection or a relapse of the previous one. The fact that she reported no further contact with cats seems to suggest the latter. The paradoxical worsening after treatment initiation, in conjunction with antiretroviral therapy, is probably a manifestation of the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, and has previously been described to complicate the curse of sporotrichosis among HIV-infected patients [12], [13].

Molecular analyses revealed S. brasiliensis as the etiological agent of our patient's illness. Assignment of the causative species of Sporothrix spp. in individual patients is of utmost importance, since such knowledge will allow us to better understand its epidemiology, clinical patterns and response to treatment. A recent study from Rio de Janeiro state compared 45 patients with sporotrichosis due to S. brasiliensis with 5 patients with disease due to S. schenckii sensu stricto and suggested that disease caused by the former is more likely associated with disseminated cutaneous infection, hypersensitivity reactions (such as erythema nodosum and erythema multiforme), and mucosal involvement, but usually required a shorter course of itraconazole [14]. Atypical and aggressive presentations of sporotrichosis due to S. brasiliensis in apparently non-immunosuppressed patients have been recently reported [15], [16], [17], [18].

We found this case to be noteworthy due to the unusual and aggressive clinical presentation of zoonotic sporotrichosis in a severely immunocompromised HIV infected patient who had no simultaneous cutaneous involvement. Fortunately, prompt and complete response to treatment was achieved. Sporotrichosis remains a neglected opportunistic infection among HIV-infected patients and awareness of this potentially fatal infection is of utmost importance if treatment is not to be delayed and if potentially devastating complications are to be avoided. The present case also seems to underline the importance of a having a heightened awareness of the overall burden of neglected fungal diseases in Brazilian patients [19].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Mahajan V.K. Sporotrichosis: an overview and therapeutic options. Dermatol. Res. Pract. 2014;2014:272376. doi: 10.1155/2014/272376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lutz A., Splendore A. Sobre uma micose observada em homens e ratos: contribuição para o conhecimento das assim chamadas esporotricoses. Rev. Méd. S. Paulo. 1907;10:433–450. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramos e Silva J. Sporotrichosis in Brazil. In: Marshall J., editor. Vol. 2. Excerpta Medica Foundation; Amsterdam: 1972. pp. 370–386. (Essays on Tropical Dermatology). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schubach A.O., Schubach T.M., Barros M.B. Epidemic cat-transmitted sporotrichosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:1185–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc051680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gremião I.D., Miranda L.H., Reis E.G., Rodrigues A.M., Pereira S.A. Zoonotic epidemic of sporotrichosis: cat to human transmission. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006077. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodrigues A.M., de Hoog G.S., de Camargo Z.P. Molecular diagnosis of pathogenic sporothrix species. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015;9(12):e0004190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freitas D.F., Valle A.C., da Silva M.B., Campos D.P., Lyra M.R., de Souza R.V. Sporotrichosis: an emerging neglected opportunistic infection in HIV-infected patients in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014;8(8):e3110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moreira J.A., Freitas D.F., Lamas C.C. The impact of sporotrichosis in HIV-infected patients: a systematic review. Infection. 2015;43:267–276. doi: 10.1007/s15010-015-0746-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silva-Vergara M.L., de Camargo Z.P., Silva P.F., Abdalla M.R., Sgarbieri R.N., Rodrigues A.M. Disseminated Sporothrix brasiliensis infection with endocardial and ocular involvement in an HIV-infected patient. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012;86:477–480. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paixão A.G., Galhardo M.C.G., Almeida-Paes R., Nunes E.P., Gonçalves M.L.C., Chequer G.L. The difficult management of disseminated Sporothrix brasiliensis in a patient with advanced AIDS. AIDS Res. Ther. 2015;12:16. doi: 10.1186/s12981-015-0051-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freitas D.F., Lima M.A., de Almeida-Paes R., Lamas C.C., do Valle A.C., Oliveira M.M. Sporotrichosis in the central nervous system caused by Sporothrix brasiliensis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015;61:663–664. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyra M.R., Nascimento M.L., Varon A.G., Pimentel M.I., Antonio L.F., Saheki M.N. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV and sporotrichosis coinfection: report of two cases and review of the literature. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2014;47:806–809. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0146-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eyer-Silva W.A., Rosa da Silva G.A., Martins C.J. A challenging case of disseminated subcutaneous mycosis from inner Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017;97:1280–1281. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Almeida-Paes R., de Oliveira M.M., Freitas D.F., do Valle A.C., Zancopé-Oliveira R.M., Gutierrez-Galhardo M.C. Sporotrichosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: sporothrix brasiliensis is associated with atypical clinical presentations. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014;8(9):e3094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orofino-Costa R., Unterstell N., Carlos Gripp A., de Macedo P.M., Brota A., Dias E. Pulmonary cavitation and skin lesions mimicking tuberculosis in a HIV negative patient caused by Sporothrix brasiliensis. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2013;2:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freitas D.F., Lima M.A., de Almeida-Paes R., Lamas C.C., do Valle A.C., Oliveira M.M. Sporotrichosis in the central nervous system caused by Sporothrix brasiliensis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015;61:663–664. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mialski R., de Oliveira J.N., Jr, da Silva L.H., Kono A., Pinheiro R.L., Teixeira M.J. Chronic Meningitis and hydrocephalus due to Sporothrix brasiliensis in immunocompetent adults: a challenging entity. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2018;5(5):ofy081. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernandes B., Caligiorne R.B., Coutinho D.M., Gomes R.R., Rocha-Silva F., Machado A.S. A case of disseminated sporotrichosis caused by Sporothrix brasiliensis. Med Mycol. Case Rep. 2018;21:34–36. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giacomazzi J., Baethgen L., Carneiro L.C., Millington M.A., Denning D.W., Colombo A.L. The burden of serious human fungal infections in Brazil. Mycoses. 2016;59(3):145–150. doi: 10.1111/myc.12427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]